This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: How to Camp Out

Author: John M. Gould

Release Date: January 22, 2006 [eBook #17575]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HOW TO CAMP OUT***

| CHAPTER. | ||

| I. | Getting Ready | 9 |

| II. | Small Parties travelling afoot and camping | 14 |

| III. | Large Parties afoot with Baggage-Wagon | 25 |

| IV. | Clothing | 35 |

| V. | Stoves and Cooking-Utensils | 39 |

| VI. | Cooking | 44 |

| VII. | Marching | 50 |

| VIII. | The Camp | 60 |

| IX. | Tents, Tent Poles and Pins | 72 |

| X. | Miscellaneous.—General Advice | 90 |

| XI. | Diary | 107 |

| XII. | "How to do it," by Rev. Edward Everett Hale, &c. | 113 |

| XIII. | Hygienic Notes, by Dr. Elliott Coues, U.S.A. | 117 |

In these few pages I have tried to prepare something about camping and walking, such as I should have enjoyed reading when I was a boy; and, with this thought in my mind, I some years ago began to collect the subject-matter for a book of this kind, by jotting down all questions about camping, &c., that my young friends asked me. I have also taken pains, when I have been off on a walk, or have been camping, to notice the parties of campers and trampers that I have chanced to meet, and have made a note of their failures or success. The experiences of the pleasant days when, in my teens, I climbed the mountains of Oxford County, or sailed through Casco Bay, have added largely to the stock of notes; and finally the diaries of "the war," and the recollections of "the field," have contributed generously; so that, with quotations, and some help from other sources, a sizable volume is ready.

Although it is prepared for young men,—for students more especially,—it contains much, I trust, that will prove valuable to campers-out in general.[Pg 6]

I am under obligations to Dr. Elliott Coues, of the United States Army, for the valuable advice contained in Chapter XIII.; and I esteem it a piece of good fortune that his excellent work ("Field Ornithology") should have been published before this effort of mine, for I hardly know where else I could have found the information with authority so unquestionable.

Prof. Edward S. Morse has increased the debt of gratitude I already owe him, by taking his precious time to draw my illustrations, and prepare them for the engraver.

Mr. J. Edward Fickett of Portland, a sailmaker, and formerly of the navy, has assisted in the chapter upon tents; and there are numbers of my young friends who will recognize the results of their experience, as they read these pages, and will please to receive my thanks for making them known to me.

Portland, Me., January, 1877.[Pg 7]

The hope of camping out that comes over one in early spring, the laying of plans and arranging of details, is, I sometimes think, even more enjoyable than reality itself. As there is pleasure in this, let me advise you to give a practical turn to your anticipations.

Think over and decide whether you will walk, go horseback, sail, camp out in one place, or what you will do; then learn what you can of the route you propose to go over, or the ground where you intend to camp for the season. If you think of moving through or camping in places unknown to you, it is important to learn whether you can buy provisions and get lodgings along your route. See some one, if you can, who has been where you think of going, [Pg 10]and put down in a note-book all he tells you that is important.

Have your clothes made or mended as soon as you decide what you will need: the earlier you begin, the less you will be hurried at the last.

You will find it is a good plan, as fast as you think of a thing that you want to take, to note it on your memorandum; and, in order to avoid delay or haste, to cast your eyes over the list occasionally to see that the work of preparation is going on properly. It is a good plan to collect all of your baggage into one place as fast as it is ready; for if it is scattered you are apt to lose sight of some of it, and start without it.

As fast as you get your things ready, mark your name on them: mark every thing. You can easily cut a stencil-plate out of an old postal card, and mark with a common shoe-blacking brush such articles as tents, poles, boxes, firkins, barrels, coverings, and bags.

Some railroads will not check barrels, bags, or bundles, nor take them on passenger trains. Inquire beforehand, and send your baggage ahead if the road will not take it on your train.

Estimate the expenses of your trip, and take more money than your estimate. Carry also an abundance of small change.

Do not be in a hurry to spend money on new [Pg 11]inventions. Every year there is put upon the market some patent knapsack, folding stove, cooking-utensil, or camp trunk and cot combined; and there are always for sale patent knives, forks, and spoons all in one, drinking-cups, folding portfolios, and marvels of tools. Let them all alone: carry your pocket-knife, and if you can take more let it be a sheath or butcher knife and a common case-knife.

Take iron or cheap metal spoons.

Do not attempt to carry crockery or glassware upon a march.

A common tin cup is as good as any thing you can take to drink from; and you will find it best to carry it so that it can be used easily.[1]

Take nothing nice into camp, expecting to keep it so: it is almost impossible to keep things out of the dirt, dew, rain, dust, or sweat, and from being broken or bruised.

Many young men, before starting on their summer vacation, think that the barber must give their hair a "fighting-cut;" but it is not best to shave the head so closely, as it is then too much exposed to the sun, flies, and mosquitoes. A moderately short cut to the hair, however, is advisable for comfort and cleanliness. [Pg 12]

If you are going to travel where you have never been before, begin early to study your map. It is of great importance, you will find, to learn all you can of the neighborhood where you are going, and to fix it in your mind.

So many things must be done at the last moment, that it is best to do what you can beforehand; but try to do nothing that may have to be undone.

Wear what you please if it be comfortable and durable: do not mind what people say. When you are camping you have a right to be independent.

If you are going on a walking-party, one of the best things you can do is to "train" a week or more before starting, by taking long walks in the open air.

Finally, leave your business in such shape that it will not call you back; and do not carry off keys, &c., which others must have; nor neglect to see the dentist about the tooth that usually aches when you most want it to keep quiet.

For convenience the following list is inserted here. It is condensed from a number of notes made for trips of all sorts, except boating and horseback-riding. It is by no means exhaustive, yet there are very many more things named than you can possibly use to advantage upon any one tour. Be careful not to be led astray by it into [Pg 13]overloading yourself, or filling your camp with useless luggage. Be sure to remember this.

| Ammon'd opodeldoc. | Fishing-tackle. | Paper. |

| Axe (in cover). | Flour (prepared). | " collars. |

| Axle-grease. | Frying-pan. | Pens. |

| Bacon. | Guide-book. | Pepper. |

| Barometer (pocket). | Half-barrel. | Pickles. |

| Bean-pot. | Halter. | Pins. |

| Beans (in bag). | Hammer. | Portfolio. |

| Beef (dried). | Hard-bread. | Postage stamps. |

| Beeswax. | Harness (examine!). | Postal cards. |

| Bible. | Hatchet. | Rope. |

| Blacking and brush. | Haversack. | Rubber blanket. |

| Blankets. | Ink (portable bottle). | " coat. |

| Boxes. | Knives (sheath, table, | " boots. |

| Bread for lunch. | pocket and butcher.) | Sail-needle. |

| Brogans (oiled). | Lemons. | Salt. |

| Broom. | Liniment. | " fish. |

| Butter-dish and cover. | Lunch for day or two. | " pork. |

| Canned goods. | Maps. | Salve. |

| Chalk. | Matches and safe. | Saw. |

| Cheese. | Marline. | Shingles (for plates). |

| Clothes-brush. | Meal (in bag). | Shirts. |

| Cod-line. | Meal-bag (see p. 32). | Shoes and strings. |

| Coffee and pot. | Medicines. | Slippers. |

| Comb. | Milk-can. | Soap. |

| Compass. | Molasses. | Song-book. |

| Condensed milk. | Money ("change"). | Spade. |

| Cups. | Monkey-wrench. | Spoons. |

| Currycomb. | Mosquito-bar. | Stove (utensils in bags). |

| Dates. | Mustard and pot. | Sugar. |

| Dippers. | Nails. | Tea. |

| Dishes. | Neat's-foot oil. | Tents. |

| Dish-towels. | Night-shirt. | " poles. |

| Drawers. | Oatmeal. | " pins. |

| Dried fruits. | Oil-can. | Tooth-brush. |

| Dutch oven. | Opera-glass. | Towels. |

| Envelopes. | Overcoat. | Twine. |

| Figs. | Padlock and key. | Vinegar. |

| Firkin (see p. 48). | Pails | Watch and key. |

We will consider separately the many ways in which a party can spend a summer vacation; and first we will start into wild and uninhabited regions, afoot, carrying on our backs blankets, a tent, frying-pan, food, and even a shot-gun and fishing-tackle. This is very hard work for a young man to follow daily for any length of time; and, although it sounds romantic, yet let no party of young people think they can find pleasure in it many days; for if they meet with a reverse, have much rainy weather, or lose their way, some one will almost surely be taken sick, and all sport will end.

If you have a mountain to climb, or a short trip of only a day or two, I would not discourage you from going in this way; but for any extended tour it is too severe a strain upon the physical powers of one not accustomed to similar hard work.[Pg 15]

A second and more rational way, especially for small parties, is that of travelling afoot in the roads of a settled country, carrying a blanket, tent, food, and cooking-utensils; cooking your meals, and doing all the work yourselves. If you do not care to travel fast, to go far, or to spend much money, this is a fine way. But let me caution you first of all about overloading, for this is the most natural thing to do. It is the tendency of human nature to accumulate, and you will continually pick up things on your route that you will wish to take along; and it will require your best judgment to start with the least amount of luggage, and to keep from adding to it.

You have probably read that a soldier carries a musket, cartridges, blanket, overcoat, rations, and other things, weighing forty or fifty pounds. You will therefore say to yourself, "I can carry twenty." Take twenty pounds, then, and carry it around for an hour, and see how you like it. Very few young men who read this book will find it possible to enjoy themselves, and carry more than twenty pounds a greater distance than ten miles a day, for a week. To carry even the twenty pounds ten miles a day is hard work to many, although every summer there are [Pg 16]parties who do their fifteen, twenty, and more miles daily, with big knapsacks on their backs; but it is neither wise, pleasant, nor healthful, to the average young man, to do this.

Let us cut down our burden to the minimum, and see how much it will be. First of all, you must take a rubber blanket or a light rubber coat,—something that will surely shed water, and keep out the dampness of the earth when slept on. You must have something of this sort, whether afoot, horseback, with a wagon, or in permanent camp.[2]

For carrying your baggage you will perhaps prefer a knapsack, though many old soldiers are not partial to that article. There are also for sale broad straps and other devices as substitutes for the knapsack. Whatever you take, be sure it has broad straps to go over your shoulders: otherwise you will be constantly annoyed from their cutting and chafing you.

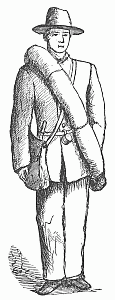

You can dispense with the knapsack altogether in the same way that soldiers do,—by rolling up in your blanket whatever you have to [Pg 17]carry. You will need to take some pains in this, and perhaps call a comrade to assist you. Lay out the blanket flat, and roll it as tightly as possible without folding it, enclosing the other baggage[3] as you roll; then tie it in a number of places to prevent unrolling, and the shifting about of things inside; and finally tie or strap together the two ends, and throw the ring thus made over the shoulder, and wear it as you do the strap of the haversack,—diagonally across the body.

The advantages of the roll over the knapsack are important. You save the two and a half pounds weight; the roll is very much easier to the shoulder, and is easier shifted from one shoulder to the other, or taken off; and you can ease the [Pg 18]burden a little with your hands. It feels bulky at first, but you soon become used to it. On the whole, you will probably prefer the roll to the knapsack; but if you carry much weight you will very soon condemn whatever way you carry it, and wish for a change.

A haversack is almost indispensable in all pedestrian tours. Even if you have your baggage in a wagon, it is best to wear one, or some sort of a small bag furnished with shoulder straps, so that you can carry a lunch, writing materials, guide-book, and such other small articles as you constantly need. You can buy a haversack at the stores where sportsmen's outfits are sold; or you can make one of enamel-cloth or rubber drilling, say eleven inches deep by nine wide, with a strap of the same material neatly doubled and sewed together, forty to forty-five inches long, and one and three-quarters inches wide. Cut the back piece about nineteen inches long, so as to allow for a flap eight inches long to fold over the top and down the front. Sew the strap on the upper corners of the back piece, having first sewed a facing inside, to prevent its tearing out the back.

Next in the order of necessities is a woollen blanket,—a good stout one, rather than the [Pg 19]light or flimsy one that you may think of taking. In almost all of the Northern States the summer nights are apt to be chilly; while in the mountainous regions, and at the seaside, they are often fairly cold. A lining of cotton drilling will perhaps make a thin blanket serviceable. This lining does not need to be quite as long nor as wide as the blanket, since the ends and edges of the blanket are used to tuck under the sleeper. One side of the lining should be sewed to the blanket, and the other side and the ends buttoned; or you may leave off the end buttons. You can thus dry it, when wet, better than if it were sewed all around. You can lay what spare clothing you have, and your day-clothes, between the lining and blanket, when the night is very cold.

In almost any event, you will want to carry a spare shirt; and in cold weather you can put this on, when you will find that a pound of shirt is as warm as two pounds of overcoat.

If you take all I advise, you will not absolutely need an overcoat, and can thus save carrying a number of pounds.

The tent question we will discuss elsewhere; but you can hardly do with less than a piece of shelter-tent. If you have a larger kind, the man who carries it must have some one to assist him in carrying his own stuff, so that the burden may be equalized.[Pg 20]

If you take tent-poles, they will vex you sorely, and tempt you to throw them away: if you do not carry them, you will wonder when night comes why you did not take them. If your tent is not large, so that you can use light ash poles, I would at least start with them, unless the tent is a "shelter," as poles for this can be easily cut.

You will have to carry a hatchet; and the kind known as the axe-pattern hatchet is better than the shingling-hatchet for driving tent-pins. I may as well caution you here not to try to drive tent-pins with the flat side of the axe or hatchet, for it generally ends in breaking the handle,—quite an accident when away from home.

For cooking-utensils on a trip like that we are now proposing, you will do well to content yourself with a frying-pan, coffee-pot, and perhaps a tin pail; you can do wonders at cooking with these.

We will consider the matter of cooking and food elsewhere; but the main thing now is to know beforehand where you are going, and to learn if there are houses and shops on the route. Of course you must have food; but, if you have to carry three or four days' rations in your haversack, I fear that many of my young friends will fail to see the pleasure of their trip. Yet carry [Pg 21]them if you must: do not risk starvation, whatever you do. Also remember to always have something in your haversack, no matter how easy it is to buy what you want.

I have now enumerated the principal articles of weight that a party must take on a walking-tour when they camp out, and cook as they go. If the trip is made early or late in the season, you must take more clothing. If you are gunning, your gun, &c., add still more weight. Every one will carry towel, soap, comb, and toothbrush.

Then there is a match-safe (which should be air-tight, or the matches will soon spoil), a box of salve, the knives, fork, spoon, dipper, portfolio, paper, Testament, &c. Every man also has something in particular that "he wouldn't be without for any thing."[4]

There should also be in every party a clothes brush, mosquito-netting, strings, compass, song-book, guide-book, and maps, which should be company property.

I have supposed every one to be dressed about as usual, and have made allowance only for extra weight; viz.,—[Pg 22]

| Rubber blanket | 2-1/2 pounds. |

| Stout woollen blanket and lining | 4-1/2 " |

| Knapsack, haversack, and canteen | 4 " |

| Drawers, spare shirt, socks, and collars | 2 " |

| Half a shelter-tent, and ropes | 2 " |

| Toilet articles, stationery, and small wares | 2 " |

| Food for one day | 3 " |

| ———— | |

| Total | 20 pounds. |

You may be able to reduce the weight here given by taking a lighter blanket, and no knapsack or canteen; but most likely the food that you actually put in your haversack will weigh more than three pounds. You must also carry your share of the following things:—

| Frying-pan, coffee-pot, and pail | 3 pounds. |

| Hatchet, sheath-knife, case, and belt | 3 " |

| Company property named on last page | 3 " |

Then if you carry a heavier kind of tent than the "shelter," or carry tent-poles, you must add still more. Allow also nearly three pounds a day per man for food, if you carry more than enough for one day; and remember, that when tents, blankets, and clothes get wet, it adds about a quarter to their weight.

You see, therefore, that you have the prospect of hard work. I do not wish to discourage you from going in this way: on the contrary, there is a great deal of pleasure to be had by doing so. But the majority of men under twenty years of [Pg 23]age will find no pleasure in carrying so much weight more than ten miles a day; and if a party of them succeed in doing so, and in attending to all of the necessary work, without being worse for it, they will be fortunate.

In conclusion, then, if you walk, and carry all your stuff, camping, and doing all your work, and cooking as you go, you should travel but few miles a day, or, better still, should have many days when you do not move your camp at all.

It is not necessary to say much about the other ways of going afoot. If you can safely dispense with cooking and carrying food, much will be gained for travel and observation. The expenses, however, will be largely increased. If you can also dispense with camping, you ought then to be able to walk fifteen or twenty miles daily, and do a good deal of sight-seeing besides. You should be in practice, however, to do this.

You must know beforehand about your route, and whether the country is settled where you are going.

Keep in mind, when you are making plans, that it is easier for one or two to get accommodation at the farmhouses than for a larger party.

I heard once of two fellows, who, to avoid buying and carrying a tent, slept on hay-mows, [Pg 24]usually without permission. It looks to me as if those young men were candidates for the penitentiary. If you cannot travel honorably, and without begging, I should advise you to stay at home.[Pg 25]

With a horse and wagon to haul your baggage you can of course carry more. First of all take another blanket or two, a light overcoat, more spare clothing, an axe, and try to have a larger tent than the "shelter."

If the body of the wagon has high sides, it will not be a very difficult task to make a cloth cover that will shed water, and you will then have what is almost as good as a tent: you can also put things under the wagon. You must have a cover of some sort for your wagon-load while on the march, to prevent injury from showers that overtake you, and to keep out dust and mud. A tent-fly will answer for this purpose.

You want also to carry a few carriage-bolts, some nails, tacks, straps, a hand-saw, and axle-wrench or monkey-wrench. I have always found use for a sail-needle and twine; and I carry them [Pg 26]now, even when I go for a few days, and carry all on my person.

The first drawback that appears, when you begin to plan for a horse and wagon, is the expense. You can overcome this in part by adding members to your company; but then you meet what is perhaps a still more serious difficulty,—the management of a large party.

Another inconvenience of large numbers is that each member must limit his baggage. You are apt to accumulate too great bulk for the wagon, rather than too great weight for the horse.

Where there are many there must be a captain,—some one that the others are responsible to, and who commands their respect. It is necessary that those who join such a party should understand that they ought to yield to him, whether they like it or not.

The captain should always consult the wishes of the others, and should never let selfish considerations influence him. Every day his decisions as to what the party shall do will tend to make some one dissatisfied; and although it is the duty of the dissatisfied ones to yield, yet, since submission to another's will is so hard, the captain must try to prevent any "feeling," and above all to avoid even the appearance of tyranny.

System and order become quite essential as our numbers increase, and it is well to have the [Pg 27]members take daily turns at the several duties; and during that day the captain must hold each man to a strict performance of his special trust, and allow no shirking.

After a few days some of the party will show a willingness to accept particular burdens all of the time; and, if these burdens are the more disagreeable ones, the captain will do well to make the detail permanent.

Nothing tends to make ill feeling more than having to do another's work; and, where there are many in a party, each one is apt to leave something for others to do. The captain must be on the watch for these things, and try to prevent them. It is well for him, and for all, to know that he who has been a "good fellow" and genial companion at home may prove quite otherwise during a tour of camping. Besides this, it is hardly possible for a dozen young men to be gone a fortnight on a trip of this kind without some quarrelling; and, as this mars the sport so much, all should be careful not to give or take offence. If you are starting out on your first tour, keep this fact constantly in mind.

Perhaps I can illustrate this division of labor.

We will suppose a party of twelve with one horse and an open wagon, four tents, a stove, and other baggage. First, number the party, and assign to each the duties for the first day.[Pg 28]

| 1. Captain. Care of horse and wagon; loading and unloading wagon. |

| 2. Jack. Loading and unloading wagon. |

| 3. Joe. Captain's assistant and errand-boy; currying horse. |

| 4. Mr. Smith. Cooking and purchasing. |

| 5. Sam. Wood, water, fire, setting of table. |

| 6. Tom. Wood, water, fire, setting of table. |

| 7. Mr. Jones. |

| 8. Henry. |

| 9. Bob. |

| 10. Senior. |

| 11. William. |

| 12. Jake. |

The party is thus arranged in four squads of three men each, the oldest at the heads. One half of the party is actively engaged for to-day, while the other half has little to do of a general nature, except that all must take turns in leading the horse, and marching behind the wagon. It is essential that this be done, and it is best that only the stronger members lead the horse.

To-morrow No. 7 takes No. 1's place, No. 8 takes No. 2's, and so on; and the first six have their semi-holiday.

In a few days each man will have shown a special willingness for some duty, which by common consent and the captain's approval he is [Pg 29]permitted to take. The party then is re-organized as follows:—

| 1. Captain. General oversight; provider of food and provender. |

| 2. Jack. Washing and the care of dishes. |

| 3. Joe. (Worthless.) |

| 4. Mr. Smith. Getting breakfast daily, and doing all of the cooking on Sunday. |

| 5. Sam. (Gone home, sick of camping.) |

| 6. Tom. Wood, water, fire, setting and clearing table. |

| 7. Mr. Jones. Getting supper all alone. |

| 8. Henry. Jack's partner. Care of food. |

| 9. Bob. Currying horse, oiling axles, care of harness and wagon. |

| 10. Senior. Packing wagon. Marching behind. |

| 11. William. Packing wagon. Marching behind. |

| 12. Jake. Running errands. |

The daily detail for leading the horse will have to be made, as before, from the stronger members of the party; and if any special duty arises it must still be done by volunteering, or by the captain's suggestion.

In this arrangement there is nothing to prevent one member from aiding another; in fact, where all are employed, a better feeling prevails, and, the work being done more quickly, there is more time for rest and enjoyment.[Pg 30]

To get a horse will perhaps tax your judgment and capability as much as any thing in all your preparation; and on this point, where you need so much good advice, I can only give you that of a general nature.

The time for camping out is when horses are in greatest demand for farming purposes; and you will find it difficult to hire of any one except livery-stable men, whose charges are so high that you cannot afford to deal with them. You will have to hunt a long time, and in many places, before you will find your animal. It is not prudent to take a valuable horse, and I advise you not to do so unless the owner or a man thoroughly acquainted with horses is in the party. You may perhaps be able to hire horse, wagon, and driver; but a hired man is an objectionable feature, for, besides the expense, such a man is usually disagreeable company.

My own experience is, that it is cheaper to buy a horse outright, and to hire a harness and wagon; and, since I am not a judge of horse-flesh, I get some friend who is, to go with me and advise. I find that I can almost always buy a horse, even when I cannot hire. Twenty to fifty dollars will bring as good an animal as I need. He may be old, broken down, spavined, wind-broken, or lame; but if he is not sickly, or if his lameness is not from recent injury, it is [Pg 31]not hard for him to haul a fair load ten or fifteen miles a day, when he is helped over the hard places.

So now, if you pay fifty dollars for a horse, you can expect to sell him for about twenty or twenty-five dollars, unless you were greatly cheated, or have abused your brute while on the trip, both of which errors you must be careful to avoid. It is a simple matter of arithmetic to calculate what is best for you to do; but I hope on this horse question you may have the benefit of advice from some one who has had experience with the ways of the world. You will need it very much.

If you have the choice of wagons, take one that is made for carrying light, bulky goods, for your baggage will be of that order. One with a large body and high sides, or a covered wagon, will answer. In districts where the roads are mountainous, rough, and rocky, wagons hung on thoroughbraces appear to suit the people the best; but you will have no serious difficulty with good steel springs if you put in rubber bumpers, and also strap the body to the axles, thus preventing the violent shutting and opening of the springs; for you must bear in mind that the main leaf of a steel spring is apt to break by the sudden pitching upward of the wagon-body.[Pg 32]

It has been my fortune twice to have to carry large loads in small low-sided wagons; and it proved very convenient to have two or three half-barrels to keep food and small articles in, and to roll the bedding in rolls three or four feet wide, which were packed in the wagon upon their ends. The private baggage was carried in meal-bags, and the tents in bags made expressly to hold them; we could thus load the wagon securely with but little tying.

For wagons with small and low bodies, it would be well to put a light rail fourteen to eighteen inches above the sides, and hold it there by six or eight posts resting on the floor, and confined to the sides of the body.

Drive carefully and slowly over bad places. It makes a great deal of difference whether a wheel strikes a rock with the horse going at a trot, or at a walk.

If your load is heavy, and the roads very hard, or the daily distance long, you had better have a collar for the horse: otherwise a breastplate-harness will do. In your kit of tools it is well to have a few straps, an awl, and waxed ends, against the time that something breaks. Oil the harness before you start, and carry about a pint of neat's-foot oil, which you can also use upon the men's [Pg 33]boots. At night look out that the harness and all of your baggage are sheltered from dew and rain, rats and mice.

This way of travelling is peculiarly adapted to a party of different ages, rather than for one exclusively of young men. It is especially suitable where there are ladies who wish to walk and camp, or for an entire family, or for a school with its teachers. The necessity of a head to a party will hardly be recognized by young men; and, even if it is, they are still unwilling, as a general rule, to submit to unaccustomed restraint.

The way out of this difficulty is for one man to invite his comrades to join his party, and to make all the others understand, from first to last, that they are indebted to him for the privilege of going. It is then somewhat natural for the invited guests to look to their leader, and to be content with his decisions.

The best of men get into foolish dissensions when off on a jaunt, unless there is one, whose voice has authority in it, to direct the movements.

I knew a party of twenty or more that travelled in this way, and were directed by a trio composed of two gentlemen and one lady.[Pg 34] This arrangement proved satisfactory to all concerned.[5]

It has been assumed in all cases that some one will lead the horse,—not ride in the loaded wagon,—and that two others will go behind and not far off, to help the horse over the very difficult places, as well as to have an eye on the load, that none of it is lost off, or scrapes against the wheels. Whoever leads must be careful not to fall under the horse or wagon, nor to fall under the horse's feet, should he stumble. These are daily and hourly risks: hence no small boy should take this duty.[6][Pg 35]

If your means allow it, have a suit especially for the summer tour, and sufficiently in fashion to indicate that you are a traveller or camper.

Loose woollen shirts, of dark colors and with flowing collars, will probably always be the proper thing. Avoid gaudiness and too much trimming. Large pockets, one over each breast, are "handy;" but they spoil the fit of the shirt, and are always wet from perspiration. I advise you to have the collar-binding of silesia, and fitted the same as on a cotton shirt, only looser; then have a number of woollen collars (of different styles if you choose), to button on in the same manner as a linen collar. You can thus keep your neck cool or warm, and can wash the collars, which soil so easily, without washing the whole shirt. The shirt should reach nearly to the knees, to prevent disorders in the stomach and bowels. There are [Pg 36]many who will prefer cotton-and-wool goods to all-wool for shirts. The former do not shrink as much, nor are they as expensive, as the latter.

If you wear drawers, better turn them inside out, so that the seams may not chafe you. They must be loose.

You need to exercise more care in the selection of shoes than of any other article of your outfit. Tight boots put an end to all pleasure, if worn on the march; heavy boots or shoes, with enormously thick soles, will weary you; thin boots will not protect the feet sufficiently, and are liable to burst or wear out; Congress boots are apt to bind the cords of the leg, and thus make one lame; short-toed boots or shoes hurt the toes; loose ones do the same by allowing the foot to slide into the toe of the boot or shoe; low-cut shoes continually fill with dust, sand, or mud.

For summer travel, I think you can find nothing better than brogans reaching above the ankles, and fastening by laces or buttons as you prefer, but not so tight as to bind the cords of the foot. See that they bind nowhere except upon the instep. The soles should be wide, and the heels wide and low (about two and three-[Pg 37]quarter inches wide by one inch high); have soles and heels well filled with iron nails. Be particular not to have steel nails, which slip so badly on the rocks.

Common brogans, such as are sold in every country-store, are the next best things to walk in; but it is hard to find a pair that will fit a difficult foot, and they readily let in dust and earth.

Whatever you wear, break them in well, and oil the tops thoroughly with neat's-foot oil before you start; and see that there are no nails, either in sight or partly covered, to cut your feet.

False soles are a good thing to have if your shoes will admit them: they help in keeping the feet dry, and in drying the shoes when they are wet.

Woollen or merino stockings are usually preferable to cotton, though for some feet cotton ones are by far the best. Any darning should be done smoothly, since a bunch in the stocking is apt to bruise the skin.

Be sure to have the trousers loose, and made of rather heavier cloth than is usually worn at home in summer. They should be cut high in the waist to cover the stomach well, and thus prevent sickness.

The question of wearing "hip-pants," or using [Pg 38]suspenders, is worth some attention. The yachting-shirt by custom is worn with hip-pantaloons, and often with a belt around the waist; and this tightening appears to do no mischief to the majority of people. Some, however, find it very uncomfortable, and others are speedily attacked by pains and indigestion in consequence of having a tight waist. If you are in the habit of wearing suspenders, do not change now. If you do not like to wear them over the shirt, you can wear them over a light under-shirt, and have the suspender straps come through small holes in the dress-shirt. In that case cut the holes low enough so that the dress-shirt will fold over the top of the trousers, and give the appearance of hip-pantaloons. If you undertake to wear the suspenders next to the skin, they will gall you. A fortnight's tramping and camping will about ruin a pair of trousers: therefore it is not well to have them made of any thing very expensive.

Camping offers a fine opportunity to wear out old clothes, and to throw them away when you have done with them. You can send home by mail or express your soiled underclothes that are too good to lose or to be washed by your unskilled hands.[Pg 39]

If you have a permanent camp, or if moving you have wagon-room enough, you will find a stove to be most valuable property. If your party is large it is almost a necessity.

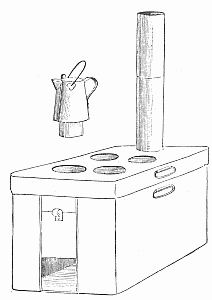

For a permanent camp you can generally get something second-hand at a stove-dealer's or the junk-shop. For the march you will need a stove of sheet iron. About the simplest, smallest, and cheapest thing is a round-cornered box made of sheet iron, eighteen to twenty-four inches long and nine to twelve inches high. It needs no bottom: the ground will answer for that. The top, which is fixed, is a flat piece of sheet iron, with a hole near one end large enough for a pot or pan, and a hole (collar) for the funnel near the other end. It is well also to have a small hole, with a slide to open and close it with, in the end of the box near the bottom, so as to put in wood, and regulate the draught; but you can dispense with the slide by raising the stove [Pg 40]from the ground when you want to admit fuel or air.

I have used a more elaborate article than this. It is an old sheet-iron stove that came home from the army, and has since been taken down the coast and around the mountains with parties of ten to twenty. It was almost an indispensable article with such large companies. It is a round-cornered box, twenty-one inches long by twenty wide, and thirteen inches high, with a slide in the front end to admit air and fuel. The bottom is fixed to the body; the top removes, and is fitted loosely to the body after the style of a firkin-cover, i.e., the flange, which is deep and strong, goes outside the stove. There are two holes on the top 5-1/2 inches in diameter, and two 7-1/2 inches, besides the collar for the funnel; [Pg 41]and these holes have covers neatly fitted. All of the cooking-utensils and the funnel can be packed inside the stove; and, if you fear it may upset on the march, you can tie the handles of the stove to those of the top piece.

A stove like this will cost about ten dollars; but it is a treasure for a large party or one where there are ladies, or those who object to having their eyes filled with smoke. The coffee-pot and tea-pot for this stove have "sunk bottoms," and hence will boil quicker by presenting more surface to the fire. You should cover the bottom of the stove with four inches or more of earth before making a fire in it.

To prevent the pots and kettles from smutting every thing they touch, each has a separate bag in which it is packed and carried.

The funnel was in five joints, each eighteen inches long, and made upon the "telescope" principle, which is objectionable on account of the smut and the jams the funnel is sure to receive. In practice we have found three lengths sufficient, but have had two elbows made; and with these we can use the stove in an old house, shed, or tent, and secure good draught.

If you have ladies in your party, or those to whom the rough side of camping-out offers few attractions, it is well to consider this stove question. Either of these here described must be handled and transported with care.[Pg 42]

A more substantial article is the Dutch oven, now almost unknown in many of the States. It is simply a deep, bailed frying-pan with a heavy cast-iron cover that fits on and overhangs the top. By putting the oven on the coals, and making a fire on the cover, you can bake in it very well. Thousands of these were used by the army during the war, and they are still very extensively used in the South. If their weight is no objection to your plans, I should advise you to have a Dutch oven. They are not expensive if you can find one to buy. If you cannot find one for sale, see if you cannot improvise one in some way by getting a heavy cover for a deep frying-pan. It would be well to try such an improvisation at home before starting, and learn if it will bake or burn, before taking it with you.

Another substitute for a stove is one much used nowadays by camping-parties, and is suited for permanent camps. It is the top of an old cooking-stove, with a length or two of funnel. If you build a good tight fireplace underneath, it answers pretty well. The objection to it is the difficulty of making and keeping the fireplace tight, and it smokes badly when the wind is not favorable for draught. I have seen a great many of these in use, but never knew but one that did well in all weathers, and this had a fireplace nicely built of brick and mortar, and a tight iron door.[Pg 43]

Still another article that can be used in permanent camps, or if you have a wagon, is the old-fashioned "Yankee baker," now almost unknown. You can easily find a tinman who has seen and can make one. There is not, however, very often an occasion for baking in camp, or at least most people prefer to fry, boil, or broil.

Camp-stoves are now a regular article of trade; many of them are good, and many are worthless. I cannot undertake to state here the merits or demerits of any particular kind; but before putting money into any I should try to get the advice of some practical man, and not buy any thing with hinged joints or complicated mechanism.[Pg 44]

When living in the open air the appetite is so good, and the pleasure of getting your own meals is so great, that, whatever may be cooked, it is excellent.

You will need a frying-pan and a coffee-pot, even if you are carrying all your baggage upon your back. You can do a great deal of good cooking with these two utensils, after having had experience; and it is experience, rather than recipes and instructions, that you need. Soldiers in the field used to unsolder their tin canteens, [Pg 45]and make two frying-pans of them; and I have seen a deep pressed-tin plate used by having two loops riveted on the edges opposite each other to run a handle through. Food fried in such plates needs careful attention and a low fire; and, as the plates themselves are somewhat delicate, they cannot be used roughly.

It is far better to carry a real frying-pan, especially if there are three or more in your party. If you have transportation, or are going into a permanent camp, do not think of the tin article.

A coffee-pot with a bail and handle is better than one with a handle only, and a lip is better than a spout; since handles and spouts are apt to unsolder.

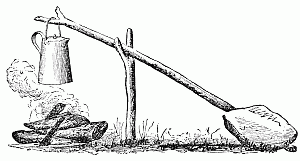

Young people are apt to put their pot or frying-pan on the burning wood, and it soon tips over. Also they let the pot boil over, and presently it [Pg 46]unsolders for want of water. Few think to keep the handle so that it can be touched without burning or smutting; and hardly any young person knows that pitchy wood will give a bad flavor to any thing cooked over it on an open fire. Live coals are rather better, therefore, than the blaze of a new fire.

If your frying-pan catches fire inside, do not get frightened, but take it off instantly, and blow out the fire, or smother it with the cover or a board if you cannot blow it out.

You will do well to consult a cook-book if you wish for variety in your cooking; but some things not found in cook-books I will give you here.

Stale bread, pilot-bread, dried corn-cakes, and crumbs, soaked a few minutes in water, or better still in milk, and fried, are all quite palatable.

In frying bread, or any thing else, have the fat boiling hot before you put in the food: this prevents it from soaking fat.

Lumbermen bake beans deliciously in an iron pot that has a cover with a projecting rim to prevent the ashes from getting in the pot. The beans are first parboiled in one or two waters until the outside skin begins to crack. They are then put into the baking-pot, and salt pork [Pg 47]at the rate of a pound to a quart and a half of dry beans is placed just under the surface of the beans. The rind of the pork should be gashed so that it will cut easily after baking. Two or three tablespoonfuls of molasses are put in, and a little salt, unless the pork is considerably lean. Water enough is added to cover the beans.

A hole three feet or more deep is dug in the ground, and heated for an hour by a good hot fire. The coals are then shovelled out, and the pot put in the hole, and immediately buried by throwing back the coals, and covering all with dry earth. In this condition they are left to bake all night.

On the same principle very tough beef was cooked in the army, and made tender and juicy. Alternate layers of beef, salt pork, and hard bread were put in the pot, covered with water, and baked all night in a hole full of coals.

Fish may also be cooked in the same way. It is not advisable, however, for parties less than six in number to trouble themselves to cook in this manner.

You had better carry butter in a tight tin or wooden box. In permanent camp you can sink it in strong brine, and it will keep some weeks. Ordinary butter will not keep sweet a long time in hot weather unless in a cool place or in brine. Hence it is better to replenish your stock often, if it is possible for you to do so.[Pg 48]

You perhaps do not need to be told that when camping or marching it is more difficult to prevent loss of food from accidents, and from want of care, than when at home. It is almost daily in danger from rain, fog, or dew, cats and dogs, and from flies or insects. If it is necessary for you to take a large quantity of any thing, instead of supplying yourself frequently, you must pay particular attention to packing, so that it shall neither be spoiled, nor spoil any thing else.

You cannot keep meats and fish fresh for many hours on a summer day; but you may preserve either over night, if you will sprinkle a little salt upon it, and place it in a wet bag of thin cloth which flies cannot go through; hang the bag in a current of air, and out of the reach of animals.

In permanent camp it is well to sink a barrel in the earth in some dry, shaded place; it will answer for a cellar in which to keep your food cool. Look out that your cellar is not flooded in a heavy shower, and that ants and other insects do not get into your food.

The lumbermen's way of carrying salt pork is good. They take a clean butter-tub with four or five gimlet-holes bored in the bottom near the chimbs. Then they pack the pork in, and cover it with coarse salt; the holes let out what little [Pg 49]brine makes, and thus they have a dry tub. Upon the pork they place a neatly fitting "follower," with a cleat or knob for a handle, and then put in such other eatables as they choose. Pork can be kept sweet for a few weeks in this way, even in the warmest weather; and by it you avoid the continual risk of upsetting and losing the brine. Before you start, see that the cover of the firkin is neither too tight nor too loose, so that wet or dry weather may not affect it too much.

I beg you to clean and wash your dishes as soon as you have done using them, instead of leaving them till the next meal. Remember to take dishcloths and towels, unless your all is a frying-pan and coffee-pot that you are carrying upon your back, when leaves and grass must be made to do dishcloth duty.[Pg 50]

It is generally advised by medical men to avoid violent exercise immediately after eating. They are right; but I cannot advise you to rest long, or at all, after breakfast, but rather to finish what you could not do before the meal, and get off at once while it is early and cool. Do not hurry or work hard at first if you can avoid it.

On the march, rest often whether you feel tired or not; and, when resting, see that you do rest.

The most successful marching that I witnessed in the army was done by marching an hour, and resting ten minutes. You need not adhere strictly to this rule: still I would advise you to halt frequently for sight-seeing, but not to lie perfectly still more than five or ten minutes, as a reaction is apt to set in, and you will feel fatigued upon rising.

Experience has shown that a man travelling [Pg 51]with a light load, or none, will walk about three miles an hour; but you must not expect from this that you can easily walk twelve miles in four heats of three miles each with ten minutes rest between, doing it all in four and a half hours. Although it is by no means difficult, my advice is for you not to expect to walk at that rate, even through a country that you do not care to see. You may get so used to walking after a while that these long and rapid walks will not weary you; but in general you require more time, and should take it.

Do not be afraid to drink good water as often as you feel thirsty; but avoid large draughts of cold water when you are heated or are perspiring, and never drink enough to make yourself logy. You are apt to break these rules on the first day in the open air, and after eating highly salted food. You can often satisfy your thirst with simply rinsing the mouth. You may have read quite different advice[8] from this, which applies to those who travel far from home, and whose daily changes bring them to water materially different from that of the day before. [Pg 52]

It is well to have a lemon in the haversack or pocket: a drop or two of lemon-juice is a great help at times; but there is really nothing which will quench the thirst that comes the first few days of living in the open air. Until you become accustomed to the change, and the fever has gone down, you should try to avoid drinking in a way that may prove injurious. Base-ball players stir a little oatmeal in the water they drink while playing, and it is said they receive a healthy stimulus thereby.

Bathing is not recommended while upon the march, if one is fatigued or has much farther to go. This seems to be good counsel, but I do advise a good scrubbing near the close of the day; and most people will get relief by frequently washing the face, hands, neck, arms, and breast, when dusty or heated, although this is one of the things we used to hear cried down in the army as hurtful. It probably is so to some people: if it hurts you, quit it.

After you have marched one day in the sun, your face, neck, and hands will be sunburnt, your feet sore, perhaps blistered, your limbs may be chafed; and when you wake up on the morning of the second day, after an almost sleepless night, you will feel as if you had been "dragged through seven cities."[Pg 53]

I am not aware that there is any preventive of sunburn for skins that are tender. A hat is better to wear than a cap, but you will burn under either. Oil or salve on the exposed parts, applied before marching, will prevent some of the fire; and in a few days, if you keep in the open air all the time, it will cease to be annoying.

To prevent foot-soreness, which is really the greatest bodily trouble you will have to contend with, you must have good shoes as already advised. You must wash your feet at least once a day, and oftener if they feel the need of it. The great preventive of foot-soreness is to have the feet, toes, and ankles covered with oil, or, better still, salve or mutton-tallow; these seem to act as lubricators. Soap is better than nothing. You ask if these do not soil the stockings. Most certainly they do. Hence wash your stockings often, or the insides of the shoes will become foul. Whenever you discover the slightest tendency of the feet to grow sore or to heat, put on oil, salve, or soap, immediately.

People differ as to these things. To some a salve acts as an irritant: to others soap acts in the same way. You must know before starting—your mother can tell you if you don't know yourself—how oil, glycerine, salve, and soap will affect your skin. Remember, the main thing is [Pg 54]to keep the feet clean and lubricated. Wet feet chafe and blister more quickly than dry.

The same rule applies to chafing upon any part of the body. Wash and anoint as tenderly as possible. If you have chafed in any part on previous marches, anoint it before you begin this.

When the soldiers found their pantaloons were chafing them, they would tie their handkerchiefs around their pantaloons, over the place affected, thus preventing friction, and stopping the evil; but this is not advisable for a permanent preventive. A bandage of cotton or linen over the injured part will serve the purpose better.

Another habit of the soldiers was that of tucking the bottom of the pantaloons into their stocking-legs when it was dusty or muddy, or when they were cold. This is something worth remembering. You will hardly walk a week without having occasion to try it.

Leather leggins, such as we read about in connection with Alpine travel, are recommended by those who have used them as good for all sorts of pedestrianism. They have not come into use much as yet in America.

The second day is usually the most fatiguing. As before stated, you suffer from loss of sleep (for few people can sleep much the first night in camp), you ache from unaccustomed work, smart [Pg 55]from sunburn, and perhaps your stomach has gotten out of order. For these reasons, when one can choose his time, it is well to start on Friday, and so have Sunday come as a day of rest and healing; but this is not at all a necessity. If you do not try to do too much the first few days, it is likely that you will feel better on the third night than at any previous time.

I have just said that your stomach is liable to become disordered. You will be apt to have a great thirst and not much appetite the first and second days, followed by costiveness, lame stomach, and a feeling of weakness or exhaustion. As a preventive, eat laxative foods on those days,—figs are especially good,—and try not to work too hard. You should lay your plans so as not to have much to do nor far to go at first. Do not dose with medicines, nor take alcoholic stimulants. Physic and alcohol may give a temporary relief, but they will leave you in bad condition. And here let me say that there is little or no need of spirits in your party. You will find coffee or tea far better than alcohol.

Avoid all nonsensical waste of strength, and gymnastic feats, before and during the march; play no jokes upon your comrades, that will make their day's work more burdensome. Young people are very apt to forget these things.

Let each comrade finish his morning nap. A [Pg 56]man cannot dispense with sleep, and it is cruel to rob a friend of what is almost his life and health. But, if any one of your party requires more sleep than the others, he ought to contrive to "turn in" earlier, and so rise with the company.

You have already been advised to take all the rest you can at the halts. Unsling the knapsack, or take off your pack (unless you lie down upon it), and make yourself as comfortable as you can. Avoid sitting in a draught of air, or wherever it chills you.

If you feel on the second morning as if you could never reach your journey's end, start off easily, and you will limber up after a while.

The great trouble with young people is, that they are ashamed to own their fatigue, and will not do any thing that looks like a confession. But these rules about resting, and "taking it easy," are the same in principle as those by which a horse is driven on a long journey; and it seems reasonable that young men should be favored as much as horses.

Try to be civil and gentlemanly to every one. You will find many who wish to make money out of you, especially around the summer hotels and boarding-houses. Avoid them if you can. Make your prices, where possible, before you engage.

Do not be saucy to the farmers, nor treat them [Pg 57]as "country greenhorns." There is not a class of people in the country of more importance to you in your travels; and you are in honor bound to be respectful to them. Avoid stealing their apples, or disturbing any thing; and when you wish to camp near a house, or on cultivated land, obtain permission from the owner, and do not make any unreasonable request, such as asking to camp in a man's front-yard, or to make a fire in dry grass or within a hundred yards of his buildings. Do not ask him to wait on you without offering to pay him. Most farmers object to having people sleep on their hay-mows; and all who permit it will insist upon the rule, "No smoking allowed here." When you break camp in the morning, be sure to put out the fires wherever you are; and, if you have camped on cleared land, see that the fences and gates are as you found them, and do not leave a mass of rubbish behind for the farmer to clear up.

When you climb a mountain, make up your mind for hard work, unless there is a carriage-road, or the mountain is low and of gentle ascent. If possible, make your plans so that you will not have to carry much up and down the steep parts. It is best to camp at the foot of the mountain, or a part way up, and, leaving the most of your bag[Pg 58]gage there, to take an early start next morning so as to go up and down the same day. This is not a necessity, however; but if you camp on the mountain-top you run more risk from cold, fog, (clouds), and showers, and you need a warmer camp and more clothing than down below.

Often there is no water near the top: therefore, to be on the safe side, it is best to carry a canteen. After wet weather, and early in the summer, you can often squeeze a little water from the moss that grows on mountain-tops.

It is so apt to be chilly, cloudy, or showery at the summit, that you should take a rubber blanket and some other article of clothing to put on if needed. Although a man may sometimes ascend a mountain, and stay on the top for hours, in his shirt-sleeves, it is never advisable to go so thinly clad; oftener there is need of an overcoat, while the air in the valley is uncomfortably warm.

Do not wear the extra clothing in ascending, but keep it to put on when you need it. This rule is general for all extra clothing: you will find it much better to carry than to wear it.

Remember that mountain-climbing is excessively fatiguing: hence go slowly, make short rests very often, eat nothing between meals, and drink sparingly.

There are few mountains that it is advisable for ladies to try to climb. Where there is a road, [Pg 59]or the way is open and not too steep, they may attempt it; but to climb over loose rocks and through scrub-spruce for miles, is too difficult for them.[Pg 60]

It pays well to take some time to find a good spot for a camp. If you are only to stop one night, it matters not so much; but even then you should camp on a dry spot near wood and water, and where your horse, if you have one, can be well cared for. Look out for rotten trees that may fall; see that a sudden rain will not drown you out; and do not put your tent near the road, as it frightens horses.

For a permanent camp a good prospect is very desirable; yet I would not sacrifice all other things to this.

If you have to carry your baggage any distance by hand, you will find it convenient to use two poles (tent-poles will serve) as a hand-barrow upon which to pile and carry your stuff.

A floor to the tent is a luxury in which some indulge when in permanent camp. It is not a necessity, of course; but, in a tent occupied by ladies or children, it adds much to their comfort [Pg 61]to have a few boards, an old door, or something of that sort, to step on when dressing. Boards or stepping-stones at the door of the tent partly prevent your bringing mud inside.

If you are on a hillside, pitch your tent so that when you sleep, if you are to sleep on the ground, your feet will be lower than your head: you will roll all night, and perhaps roll out of the tent if you lie across the line running down hill.

As soon as you have pitched your tent, stretch a stout line from the front pole to the back one, near the top, upon which to hang your clothes. You can tighten this line by pulling inwards the foot of one pole before tying the line, and then lifting it back.

Do not put your clothes and bedding upon the bare ground: they grow damp very quickly. See, too, that the food is where ants will not get at it.

Do not forget to take two or three candles, and replenish your stock if you burn them: they sometimes are a prime necessity. Also do not pack them where you cannot easily find them in the dark. In a permanent camp you may be tempted to use a lantern with oil, and perhaps you will like it better than candles; but, when moving about, the lantern-lamp and oil-can will give you trouble. If you have no candlestick handy, you can use your pocket-knife, putting one blade in the bottom or side of the candle, [Pg 62]and another blade into the ground or tent-pole. You can quickly cut a candlestick out of a potato, or can drive four nails in a block of wood.

If your candles get crushed, or if you have no candles, but have grease without salt in it, you can easily make a "slut" by putting the grease in a small shallow pan or saucer with a piece of wicking or cotton rag, one end of which shall be in the grease, and the other, which you light, held out of it. This is a poor substitute for daylight, and I advise you to rise and retire early (or "turn in" and "turn out" if you prefer): you will then have more daylight than you need.

Time used in making a bed is well spent. Never let yourself be persuaded that humps and hollows are good enough for a tired man. If you cut boughs, do not let large sticks go into the bed: only put in the smaller twigs and leaves. Try your bed before you "turn in," and see if it is comfortable. In a permanent camp you ought to take time enough to keep the bed soft; and I like best for this purpose to carry a mattress when I can, or to take a sack and fill it with straw, shavings, boughs, or what not. This makes a much better bed, and can be taken out daily to the air and sun. By this I avoid the clutter there always is inside a tent filled with [Pg 63]boughs; and, more than all, the ground or floor does not mould in damp weather, from the accumulation of rubbish on it.

It is better to sleep off the ground if you can, especially if you are rheumatic. For this purpose build some sort of a platform ten inches or more high, that will do for a seat in daytime. You can make a sort of spring bottom affair if you can find the poles for it, and have a little ingenuity and patience; or you can more quickly drive four large stakes, and nail a framework to them, to which you can nail boards or barrel-staves.[9] All this kind of work must be strong, or you can have no rough-and-tumble sport on it. We used to see in the army sometimes, a mattress with a bottom of rubber cloth, and a top of heavy drilling, with rather more cotton quilted[10] between them than is put into a thick comforter. Such a mattress is a fine thing to carry in a wagon when you are on the march; but you can make a softer bed than this if you are in a permanent camp.

"Turn in" early, so as to be up with the sun. You may be tempted to sleep in your clothes; but if you wish to know what luxury is, take them [Pg 64]off as you do at home, and sleep in a sheet, having first taken a bath, or at least washed the feet and limbs. Not many care to do this, particularly if the evening air is chilly; but it is a comfort of no mean order.

If you are short of bedclothes, as when on the march, you can place over you the clothes you take off (see p. 19); but in that case it is still more necessary to have a good bed underneath.

You will always do well to cover the clothes you have taken off, or they will be quite damp in the morning.

See that you have plenty of air to breathe. It is not best to have a draught of air sweeping through the tent, but let a plenty of it come in at the feet of the sleeper or top of the tent.

A hammock is a good thing to have in a permanent camp, but do not try to swing it between two tent-poles: it needs a firmer support.

Stretch a clothes-line somewhere on your camp-ground, where neither you nor your visitors will run into it in the dark.

If your camp is where many visitors will come by carriage, you will find that it will pay you for your trouble to provide a hitching-post where the horses can stand safely. Fastening to guy-lines and tent-poles is dangerous.[Pg 65]

In a permanent camp you must be careful to deposit all refuse from the kitchen and table in a hole in the ground: otherwise your camp will be infested with flies, and the air will become polluted. These sink-holes may be small, and dug every day; or large, and partly filled every day or oftener by throwing earth over the deposits. If you wish for health and comfort, do not suffer a place to exist in your camp that will toll flies to it. The sinks should be some distance from your tents, and a dry spot of land is better than a wet one. Observe the same rule in regard to all excrementitious and urinary matter. On the march you can hardly do better than follow the Mosaic law (see Deuteronomy xxiii. 12, 13).

In permanent camp, or if you propose to stay anywhere more than three days, the crumbs from the table and the kitchen refuse should be carefully looked after: to this end it is well to avoid eating in the tents where you live. Swarms of flies will be attracted by a very little food.

A spade is better, all things considered, than a shovel, either in permanent camp or on the march.[Pg 66]

When a cold and wet spell of weather overtakes you, you will inquire, "How can we keep warm?" If you are where wood is very abundant, you can build a big fire ten or fifteen feet from the tent, and the heat will strike through the cloth. This is the poorest way, and if you have only shelter-tents your case is still more forlorn. But keep the fire a-going: you can make green wood burn through a pelting storm, but you must have a quantity of it—say six or eight large logs on at one time. You must look out for storms, and have some wood cut beforehand. If you have a stove with you, a little ingenuity will enable you to set it up inside a tent, and run the funnel through the door. But, unless your funnel is quite long, you will have to improvise one to carry the smoke away, for the eddies around the tent will make the stove smoke occasionally beyond all endurance. Since you will need but little fire to keep you warm, you can use a funnel made of boards, barrel-staves, old spout, and the like. Old tin cans, boot-legs, birch-bark, and stout paper can be made to do service as elbows, with the assistance of turf, grass-ropes, and large leaves. But I forewarn you there is not much fun, either in rigging your stove and funnel, or in sitting by it and waiting [Pg 67]for the storm to blow it down. Still it is best to be busy.

Another way to keep warm is to dig a trench twelve to eighteen inches wide, and about two feet deep, running from inside to the outside of the tent. The inside end of the trench should be larger and deeper; here you build your fire. You cover the trench with flat rocks, and fill up the chinks with stones and turf; boards can be used after you have gone a few feet from the fireplace. Over the outer end, build some kind of a chimney of stones, boxes, boards, or barrels. The fireplace should not be near enough to the side of the tent to endanger it; and, the taller the chimney is, the better it will draw if you have made the trench of good width and air-tight. If you can find a sheet-iron covering for the fireplace, you will be fortunate; for the main difficulty in this heating-arrangement is to give it draught enough without letting out smoke, and this you cannot easily arrange with rocks. In digging your trench and fireplace, make them so that the rain shall not flood them.

If flat rocks and mud are plenty, you can perhaps build a fireplace at the door of your tent (outside, of course), and you will then have something both substantial and valuable. Fold one [Pg 68]flap of the door as far back as you can, and build one side of the fireplace against the pole,[11] and the other side against, or nearly over to, the corner of the tent. Use large rocks for the lower tiers, and try to have all three walls perpendicular and smooth inside. When up about three feet, or as high as the flap of the tent will allow without its being scorched, put on a large log of green wood for a mantle, or use an iron bar if you have one, and go on building the chimney. Do not narrow it much: the chimney should be as high as the top of the tent, or eddies of wind will blow down occasionally, and smoke you out. Barrels or boxes will do for the top, or you can make a cob-work of split sticks well daubed with mud. All the work of the fireplace and chimney must be made air-tight by filling the chinks with stones or chips and mud. When done, fold and confine the flap of the tent against the stonework and the mantle; better tie than nail, as iron rusts the cloth. Do not cut the tent either for this or any other purpose: you will regret it if you do. Keep water handy if there is much woodwork; and do not leave your tent for a long time, nor go to sleep with a big fire blazing.

If you have to bring much water into camp, remember that two pails carry about as easily as [Pg 69]a single one, provided you have a hoop between to keep them away from your legs. To prevent the water from splashing, put something inside the pail, that will float, nearly as large as the top of the pail.

It is not worth while to say much about those hunters' camps which are built in the woods of stout poles, and covered with brush or the bark of trees: they are exceedingly simple in theory, and difficult in practice unless you are accustomed to using the axe. If you go into the woods without an axeman, you had better rely upon your tents, and not try to build a camp; for when done, unless there is much labor put in it, it is not so [Pg 70]good as a shelter-tent. You can, however, cut a few poles for rafters, and throw the shelter-tent instead of the bark or brush over the poles. You have a much larger shelter by this arrangement of the tent than when it is pitched in the regular way, and there is the additional advantage of having a large front exposed to the fire which you will probably build; at the same time also the under side of the roof catches and reflects the heat downward. When you put up your tent in this way, however, you must look out not to scorch it, and to take especial care to prevent sparks from burning small holes in it. In fact, whenever you have a roaring fire you must guard against mischief from it.

Do not leave your clothes or blanket hanging near a brisk fire to dry, without confining them so that sudden gusts of wind shall not take them into the flame.

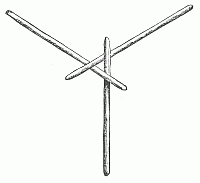

You may some time have occasion to make a shelter on a ledge or floor where you cannot drive a pin or nail. If you can get rails, poles, joists, or boards, you can make a frame in some one of the ways figured here, and throw your tents over it.

These frames will be found useful for other purposes, and it is well to remember how to make them.[Pg 72]

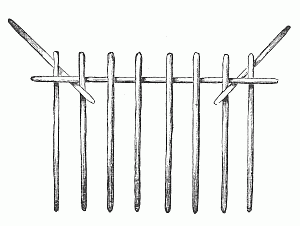

The shelter-tent used by the Union soldiers during the Rebellion was made of light duck[12] about 31-1/2 inches wide. A tent was made in two pieces both precisely alike, and each of them five feet long and five feet and two inches wide; i.e., two widths of duck. One of these pieces or half-tents was given to every soldier. That edge of the piece which was the bottom of the tent was faced at the corners with a piece of stouter duck three or four inches square. The seam in the middle of the piece was also faced at the bottom, and eyelets were worked at these three places, through which stout cords or ropes could be run to tie this side of the tent down to the tent-pin, or to fasten it to whatever else was handy. Along the other three edges of each piece of tent, at intervals of about eight inches, [Pg 73]were button-holes and buttons; the holes an inch, and the buttons four inches, from the selvage or hem.[13]

Two men could button their pieces at the tops, and thus make a tent entirely open at both ends, five feet and two inches long, by six to seven feet wide according to the angle of the roof. A third man could button his piece across one of the open ends so as to close it, although it did not make a very neat fit, and half of the cloth was not used; four men could unite their two tents by buttoning the ends together, thus doubling the length of the tent; and a fifth man could put in an end-piece.

Light poles made in two pieces, and fastened together with ferrules so as to resemble a piece of fishing-rod, were given to some of the troops when the tents were first introduced into the army; but, nice as they were at the end of the march, few soldiers would carry them, nor will you many days.

The tents were also pitched by throwing them over a tightened rope; but it was easier to cut a stiff pole than to carry either the pole or rope.

You need not confine yourself exactly to the dimensions of the army shelter-tent, but for a [Pg 74]pedestrian something of the sort is necessary if he will camp out. I have never seen a "shelter" made of three breadths of drilling (seven feet three inches long), but I should think it would be a good thing for four or five men to take.[14] And I should recommend that they make three-sided end-pieces instead of taking additional half-tents complete, for in the latter case one-half of the cloth is useless.

Five feet is long enough for a tent made on the "shelter" principle; when pitched with the roof at a right angle it is 3-1/2 feet high, and nearly seven feet wide on the ground.

Although a shelter-tent is a poor substitute for a house, it is as good a protection as you can well carry if you propose to walk any distance. It should be pitched neatly, or it will leak. In [Pg 75]heavy, pelting rains a fine spray will come through on the windward side. The sides should set at right angles to each other, or at a sharper angle if rain is expected.

There are rubber blankets made with eyelets along the edges so that two can be tied together to make a tent; but they are heavier, more expensive, and not much if any better; and you will need other rubber blankets to lie upon.

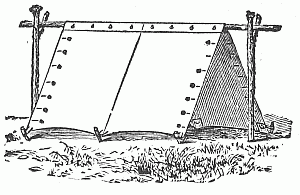

If you wish for a larger and more substantial covering than a "shelter," and propose to do the work yourself, you will do well to have a sailmaker or a tent-maker cut the cloth, and show you how the work is to be done. If you cannot have their help, you must at least have the assistance of one used to planning and cutting needle-work, to whom the following hints may not be lost. We will suppose heavy drilling 29-1/2 inches wide to be used in all instances.

To make an A-tent,[15] draw upon the floor a straight line seven feet long, to represent the upright pole or height of the tent; then draw a line at right angles to and across the end of the first one, to represent the ground or bottom of the tent. Complete the plan by finding where the corners will be on the ground line, [Pg 76]and drawing the two sides (roof) from the corners[16] to the top of the pole-line. This triangle is a trifle larger than the front and back of the tent will be.

The cloth should be cut so that the twilled side shall be the outside of the tent, as it sheds the rain better.

Place the cloth on the floor against the ground-line, and tack it (to hold it fast) to the pole-line, which it should overlap 3/8 of an inch; then cut by the roof-line. Turn the cloth over, and cut another piece exactly like the first; this second piece will go on the back of the tent. Now place the cloth against the ground-line as before, but upon the other side of the pole, and tack it to the floor after you have overlapped the selvage of the piece first cut 3/4 of an inch. Cut by the roof-line, and turn and cut again for the back of the tent.

In cutting the four small gores for the corners, you can get all the cloth from one piece, and thus save waste, by turning and tearing it in two; these gore-pieces also overlap the longer breadths 3/4 of an inch.

The three breadths that make the sides or roof are cut all alike; their length is found by [Pg 77]measuring the plan from corner to corner over the top; in the plan now under consideration, the distance will be nearly sixteen feet. When you sew them, overlap the breadths 3/4 of an inch the same as you do the end-breadths.

In sewing you can do no better than to run, with a machine, a row of stitching as near each selvage as possible; you will thus have two rows to each seam, which makes it strong enough. Use the coarsest cotton, No. 10 or 12.

The sides and two ends are made separately; when you sew them together care must be taken, for the edges of the ends are cut cross-grained, and will stretch very much more than the cloth of the sides (roof). About as good a seam as you can make, in sewing together the sides and ends, is to place the two edges together, and fold them outwards (or what will be downwards when the tent is pitched) twice, a quarter of an inch each time, and put two rows of stitching through if done on a machine, or one if with sail-needle and twine. This folding the cloth six-ply, besides making a good seam, strengthens the tent where the greatest strain comes. It is also advisable to put facings in the two ends of the top of the tent, to prevent the poles from pushing through and chafing.

The bottom of the tent is completed next by folding upwards and inwards two inches of cloth [Pg 78]to make what is called a "tabling," and again folding in the raw edge about a quarter of an inch, as is usual to make a neat job. Some makers enclose a marline or other small tarred rope to strengthen the foot of the tent, and it is well to do so. One edge of what is called the "sod-cloth" is folded in with the raw edge, and stitched at the same time. This cloth, which is six to eight inches wide, runs entirely around the bottom of the tent, excepting the door-flap, and prevents a current of air from sweeping under the tent, and saves the bottom from rotting; the sod-cloth, however, will rot or wear out instead, but you can replace it much more easily than you can repair the bottom of the tent; consequently it is best to put one on.