The Project Gutenberg EBook of Aunt Judith, by Grace Beaumont

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: Aunt Judith

The Story of a Loving Life

Author: Grace Beaumont

Release Date: May 14, 2007 [EBook #21432]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AUNT JUDITH ***

Produced by Al Haines

| I. | A School-girl Quarrel |

| II. | Aunt Judith |

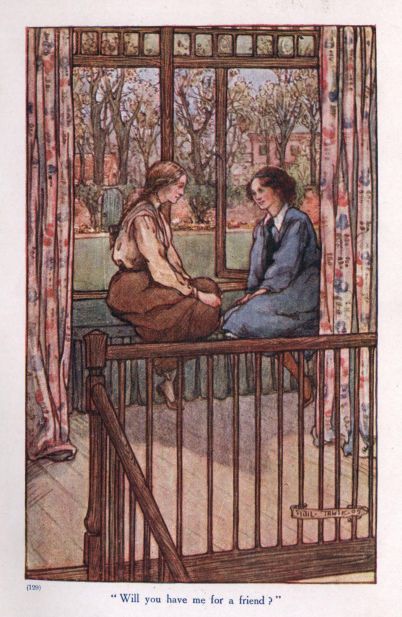

| III. | Will You have Me for a Friend? |

| IV. | A Talk with Aunt Judith |

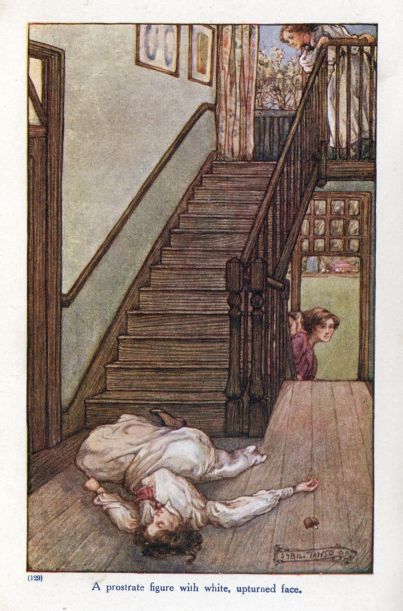

| V. | A Fallen Queen |

| VI. | Winnie's Home |

| VII. | An Afternoon at Dingle Cottage |

| VIII. | Forging the First Link |

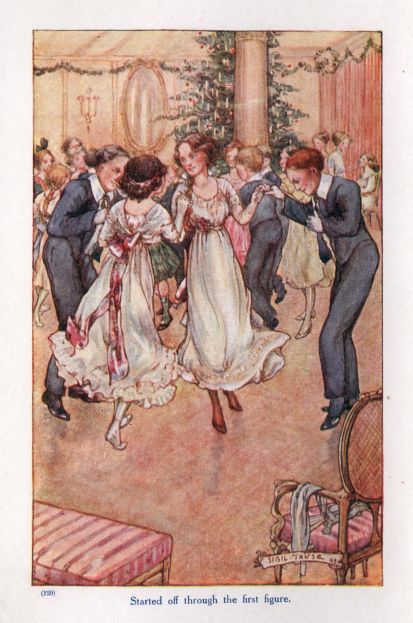

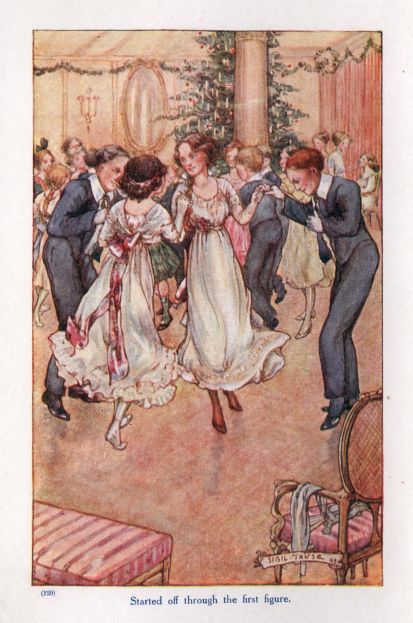

| IX. | The Christmas Party |

| X. | Gathering Clouds |

| XI. | It is so hard to say Good-bye |

| XII. | I always speak as I think |

| XIII. | Our Sailor Boy |

| XIV. | The Prize Essay |

| XV. | How shall I live through the long, long years? |

| XVI. | Light in Darkness |

| XVII. | I shall learn to be good now |

| XVIII. | Conclusion |

"Girls, girls, I've news for you!" cried Winnifred Blake, entering the school-room and surveying the faces of her school-mates with great eagerness.

Luncheon hour was almost over, and the pupils belonging to Mrs. Elder's Select Establishment for Young Ladies were gathered together in the large school-room, some enjoying a merry chat, others, more studiously inclined, conning over a forthcoming lesson.

"Give us the benefit of your news quickly, Winnie," said Ada Irvine, looking round from her snug seat on the broad window-ledge; "surely we must be going to hear something wonderful when you are so excited;" and the girl eyed her animated school-fellow half scornfully.

"A new pupil is coming," announced Winnie with an air of great solemnity. "Be patient, my friends, and I'll tell you how I know. Dinner being earlier to-day, I managed to get back to school sooner than usual, and was just crossing the hall to join you all in the school-room, when the drawing-room door opened, and Mrs. Elder appeared, accompanied by a lady in a long loose cloak and huge bonnet—regular coal-scuttle affair, girls; so large, in fact, that it was quite impossible to get a glimpse of her face. Mrs. Elder was saying as I passed, 'I shall expect your niece to-morrow morning, Miss Latimer, at nine o'clock; and trust she will prosecute her studies with all diligence, and prove a credit to the school.'" Winnie mimicked the lady-principal's soft, plausible voice as she spoke.

"A new pupil!" remarked Ada once more, her voice raised in supreme contempt; "really, Winnie, I fail to understand your excitement over such a trifle. Why, she may be a green-grocer's daughter for all you know to the contrary;" and the speaker's dainty nose was turned up with a gesture of infinite scorn.

"Well, and what then, Miss Conceit?" retorted Winnie, flushing angrily at her school-mate's contemptuous tone; "I presume a green-grocer's daughter is not exempted from possessing the same talented abilities which characterize your charming self."

"Certainly not," replied the other with the same quiet ring of scorn in her voice; "but, pray, who would associate with a green-grocer's daughter? Most assuredly not I. My mother is very particular with regard to the circle in which I move."

Winnie swept a graceful courtesy.

"Allow me to express my deep sense of obligation," she said mockingly, "at the honour conferred on my unworthy self by your attempted patronage and esteem." Then, changing her tone and raising her little head proudly—"Ada Irvine, I am ashamed of you—your pride is insufferable; and my heartiest wish is that some day you may be looked down upon and viewed with the supreme contempt you now bestow on those lower (most unfortunately) in the social scale than yourself."

"Thanks for your amiable wish," was the answer, given in that easy, tranquil voice which the owner well knew irritated her adversary more than the fiercest burst of passion would have done; "but I am afraid there is little likelihood of its ever being realized."

Winnie elevated her eyebrows. "Is that your opinion?" she said in affected surprise, while the other school-girls gathered round, tittering at the caustic little tongue. "I suppose you study the poets, Miss Irvine; and if so, doubtless you will remember who it is that says:—

'Oh wad some power the giftie gie us

To see oursels as ithers see us!'"

The mischievous child stopped for a second, and then continued: "I am afraid you look at yourself and your various charms through rose-coloured spectacles, certainly not with 'a jaundiced eye;'—but I beg your pardon; were you about to speak?" and Winnie looked innocently into the fair face of her antagonist, which was now white and set with passion.

The blue eyes were flashing with an angry light, the pretty lips trembling, and the smooth brow knit in a heavy frown; but only for a few moments. By-and-by the features relaxed their fixed and stony gaze; the countenance resumed its usual haughty expression; and, lifting up the book which was lying on her lap, Ada opened it at the required page, and ended the discussion by saying, "I shall consider it my duty to inform Mrs. Elder of your charming sentiments; in the meantime, kindly excuse me from continuing such highly edifying conversation." With that she bent her head over the French grammar, and soon appeared thoroughly engrossed in the conjugation of the verb avoir, to have, while her mischievous school-mate turned away with a light shrug of her pretty shoulders.

Winnifred Blake, the youngest daughter of a wealthy, influential gentleman, was a bright, happy girl of about fourteen years, with a kind, generous heart, and warm, impulsive nature. Being small and slight in stature, she seemed to all appearance a mere child; and the quaint, gipsy face peeping from beneath a mass of shaggy, tangled curls showed a pair of large laughter-loving eyes and a mischievous little mouth.

Was she clever?

Well, that still remained to be seen. Certainly, the bright, intelligent countenance gave no indication of a slow understanding and feeble brain; but Winnie hated study, and consequently was usually to be found adorning the foot of the class. "It is deliciously comfortable here, girls," she would say to her school-mates when even they protested against such continual indolence; "you see I am near the fire, and that is a consideration in the cold, wintry days, I assure you. Don't annoy yourselves over my shortcomings. Lazy, selfish people always get on in the world;" and speaking thus, the incorrigible child would nestle back in her lowly seat with an air of the utmost satisfaction.

Ada Irvine smiled in supreme contempt over what she termed Winnie's stupidity, and would repeat her own perfectly-learned lesson with additional triumph in her tone; but the faultless repetition by no means disconcerted her lazy school-mate, who was often heard to say, with seeming simplicity, "I could do just as well if I chose; but then I don't choose, and that, you see, makes all the difference."

Ada Irvine was an only child, and her parents having gone abroad in the (alas, how often vain!) search after health, had left her with Mrs. Elder, to whose care she was intrusted with every charge for her comfort and advantage—a charge which that young lady took great care should be amply fulfilled. She was only six months older than Winnie, but very tall, and already giving the promise of great beauty in after years. Talented and brilliant also, she held a powerful sway over the minds and actions of her schoolmates, and queened in the school right royally; but the cold, haughty pride which marred her nature failed to make her such a general favourite as her fiery, little adversary.

In the afternoon, when the school was being dismissed for the day, Ada sought the presence of the lady-principal; and consequently, just as Winnie was strapping up her books preparatory to going home, a servant appeared in the dressing-room summoning Miss Blake to Mrs. Elder's sanctum.

"Now you're in for it, Winnie," said the girls pityingly; "Ada has kept to her word and told. How mean!" But the child only tossed her curly head, and with slightly heightened colour followed the maid to the comfortable parlour where the lady-principal was usually to be found.

Mrs. Elder, seated by a small fire which burned brightly in the shining grate, turned a face expressive of the most severe displeasure on the defiant little culprit as she entered; while Ada, standing slightly in the shadow of the window-curtain, looked at the victim haughtily, and shaped her lips in a malicious smile at the lady-principal's opening words.

"I presume you are aware of my reason for requesting your presence here, Miss Blake," she began in icy tones; "and I trust you have come before me sincerely penitent for your fault. I cannot express in sufficiently strong terms the displeasure I feel at your shameful conduct this afternoon. I never thought a pupil of this establishment could be guilty of such unlady-like language as fell from your lips, and it grieves me to know that I have in my school a young girl capable of cherishing the evil spirit of animosity against a fellow-creature. What have you to say in defence of your conduct? Can you vindicate it in any way, or shall I take your silence as full confession of your guilt?"

Winnie pressed her lips tightly together, but did not speak. "I need not attempt to clear myself," she mentally decided. "Ada will have coloured our quarrel to suit herself, and being Mrs. Elder's favourite, her word will be relied on before mine; that has been the case before, and will be so again."

The lady-principal, however, mistook the continued silence for conscious guilt.

"Then I demand that an ample apology be made to Miss Irvine now, in my presence," she said once more in frigid tones. "Come, Miss Blake; my time is too precious to be trifled with."

Winnie's eyes sparkled, and raising her small head defiantly, she replied, "I decline to apologize, Mrs. Elder. I only spoke as I thought, and am quite prepared to say the same again if occasion offers. Miss Irvine knows my words, if distasteful, were but too true."

The lady-principal gasped. "Miss Blake," she cried at length, horrified at the bold assertion, and endeavouring to quail her audacious pupil with one stern, withering glance, "this is dreadful!" But the angry child only pouted, and repeated doggedly, "It is quite true."

Then Mrs. Elder rose, and laying her hand firmly on Winnie's shoulder, said quietly, but with an awful meaning underlying her words, "Apologize at once, Miss Blake, or I shall resort to stronger measures, and also complain to your parents"—a threat which terrified the unwilling girl into submission.

Going forward with flushed cheeks and mutinous mouth, she stood before the triumphant Ada, and said sullenly, "Please accept my apology for unlady-like language, Miss Irvine. I am sorry I should have degraded myself and spoken as I did, but" (and here a mischievous light swept the gloomy cloud from the piquant face and lit it up with an elfish smile) "you provoked me, and I am very outspoken."

Ada coloured with anger and vexation; and in spite of her displeasure, Mrs. Elder found it difficult to repress a smile.

"That will do," she pronounced coldly; "such an apology is only adding insult to injury. You will kindly write out twenty times four pages of French vocabulary, and also remain at the foot of all your classes during the next fortnight. Go! I am greatly displeased with you, Miss Blake;" and as the lady-principal waved her hand in token of dismissal, she frowned angrily, and looked both mortified and indignant.

Winnie required no second bidding. She drew her slight figure up to its full height, made her exit with all the dignity of an offended queen, entered the now deserted dressing-room, and seizing her books, hurried from the school, and was soon running rapidly down the busy street.

"Hallo, Win! what's the row? One would think you had stolen the giant's seven-league boots," cried a voice from behind. "Did ever I see a girl dashing along at such a rate!" And turning round, Winnie saw before her a tall, strapping boy, whose honest, freckled face, illumined by a broad, friendly grin, shone brightly on her from under a shock of fiery red hair.

"I'll bet I know without your telling me," he continued, coming to her side and removing his heavy load of books from one shoulder to the other. "Been quarrelling with the lovely Ada, eh?" and he glanced kindly at the little figure by his side.

Winnie laughed slightly. "You're about right, Dick," she replied. "There has been a cat-and-dog fight; only this time the cat's velvety paws scratched the poor little dog and wounded it sorely."

"Ah! you went at it tooth and nail, I suppose," Dick said philosophically; "pity you girls can't indulge in a regular stand-up fight." And the wild boy began to brandish his arms about as if he would thoroughly enjoy commencing there and then.

The quick flush of temper was over now, and the girl's eyes gleamed mischievously as she replied, "I've a weapon of my own, Dick, fully as powerful as yours. I'll use my tongue;" and the audacious little minx smiled saucily into her brother's honest face.

A hearty roar greeted her words, and Dick almost choked before he managed to say, "Go it, Win; I'll back you up. Commend me to a woman's tongue!" And the boy, unable to control his risible faculties, burst into a hearty laugh, which died away in a chuckle of genuine merriment.

Richard Blake, or Dick (the name by which he was generally called) was Winnie's favourite brother, and she almost idolized the big, kindly fellow, on whom the other members of the family showered ridicule and contempt. He was a bluff, outspoken lad, with a brave, true heart as tender and pitiful as a woman's; but, lacking both the capacity for and inclination to study, he by no means proved a brilliant scholar, and thus brought down on himself the censure of his masters and the heavy displeasure of his father. "Hard words break no bones. I daresay I shall manage through the world somehow," he would say after having received some cutting remark from an elder brother or sister; and Winnie, always his stanch friend and advocate, would nod her sunny head and prophesy confidently, "We shall be proud of you yet, Dick."

In the meantime they sauntered along, swinging their books and chatting gaily, till a turn in the road brought them to a quiet square where handsome dwelling-houses faced each other in sombre grandeur.

"No. 3 Victoria Square—this way, miss," said Dick, mounting the steps and ringing the bell violently.

"What a boy you are!" laughed Winnie, following, and giving her brother's rough coat a mischievous pull. "Whenever will you learn sense, Dick?" Then the door opened, and with glad young hearts brother and sister entered their comfortable home.

The October night closed in dark and wild. The wind, rising in fierce gusts, swept along the streets with relentless fury, whirling the cans on the roofs of the houses, and whistling down the chimneys with relentless roar; passers-by drew up the collars of their coats and bent their faces under the pitiless blast; while the rain, falling with its monotonous splash, splash, added to the gloom and rawness of the night.

Up and down the platform of one of the principal stations in the town a lady paced, every now and then peering into the murky darkness, or waylaying a passing porter to ask when the down-train was due. She was tall and slender, but the huge bonnet and thick veil which she wore so effectually concealed her face that it was impossible to make out whether she was young or old.

At last a whistle and the loud ringing of the bell proclaimed that the train was close at hand, and in all the glory of its powerful mechanism the great locomotive swept into the busy station. The lady, stepping nearer the edge of the platform, gazed into the windows of the carriages as the train passed, slackening speed; then with a quick gesture of recognition went forward and turned the handle of one of the doors at which a young girl was standing looking wistfully on the many faces hurrying by. "Nellie Latimer, I am sure," she said in a kind voice; "'tis a dreary night to bid you welcome. I am your Aunt Judith, dear," and assisting the girl out of the carriage, she lifted her veil for a single moment and laid a kiss on the fresh, young cheek. "What have you in the way of luggage? One trunk. Well, stand here while I go and find it," saying which she glided away and was lost to view in the bustling crowd. In a few moments she returned, followed by a porter bearing the modest, black box; and bidding the young traveller come with her, left the platform, hailed a cab, and was soon driving with her tired charge along the wet streets.

Aunt Judith gazed at the lonely little figure sitting so quietly facing her, and mentally deciding that, wearied out and home-sick, the child would naturally be disinclined for conversation, she leaned back on the carriage cushion and fell into a long train of thought.

Nellie Latimer was thankful for the silence. She had left her home early that morning for the purpose of wintering in town with her aunts, and, as it was the first flight from the parental nest, her heart was sore with grief and longing. She was the eldest daughter of Dr. Latimer, a poor country practitioner, whose practice brought him too limited an income with which to meet the expenses of the large family of hardy boys and girls growing up around him. He had sent Nellie to the village school, and when she had mastered all the knowledge to be gleaned there, endeavoured to instruct her himself; but he could ill spare the time, and so hailed with feelings of the deepest gratitude a letter from his eldest sister offering to take Nellie and give her all the advantages of a town education, "Let the child come, John," she wrote in her simple, kindly style; "she will help to brighten the hearts of three old maids, and a young face will be a cheery sight in our quiet cottage home. She will have a thorough education, and we shall endeavour to bring her up so that she may be a fitting helpmate to her mother on her return home." Dr. Latimer showed the letter to his wife, who read it thankfully. "Your sister is a noble woman, John," she said brokenly; "let us accept her offer, and may God bless her."

Thus it was that Nellie had left the home nest and come to live her life in the busy town. She knew almost nothing about her aunts, and had never seen them; for Dr. Latimer dwelt in a far-off country village, and the distance from it to the city was very great. The postman would occasionally bring a letter, book, or paper to the doctor; and every Christmas a hamper filled with choice meats and other dainties would find its way to the house, showing that the young nephews and nieces were not forgotten by the aunts they had never seen. Those "good fairies," as the little children styled them, were three in number: Aunt Judith, the bread-winner—though how, Nellie as yet did not know; Aunt Debby, the Martha of the household, hard-working and practical; and Aunt Margaret, an invalid, seldom able to leave her couch.

"I cannot tell you much about them, dear," Mrs. Latimer had said one night when talking with her eldest daughter over the coming parting. "They (meaning the aunts) were abroad on account of Aunt Margaret's health when I first met your father, and did not return home till some time after our marriage. Aunt Margaret was not any better, and had settled down into invalid habits, requiring the constant attention and care of both sisters. Aunt Judith spoke at one time of coming to spend a few days with us; but Aunt Margaret could not spare her, and so she never came. Your father says Aunt Judith is a brave, true woman, and keeps the little household together, besides the many kindnesses she bestows on us. I trust you will like your aunts, my child, and be happy with them, even though you are away from us all."

Nellie had been thinking all this over while the cab was quickly whirling her along the now deserted thoroughfares, and so deeply had her mind been occupied with these thoughts that she started in amazement when the driver drew up before the entrance of a small cottage, and she saw a bright flood of light streaming out from the hastily opened door.

"Here we are, dear," said Aunt Judith's kind voice breaking in on her reverie; "this is your new home, and there is Aunt Debby waiting to bid you welcome. Run! I shall follow you immediately."

Nellie, obeying, hurried up the little gravelled path, and reaching the door, found herself folded in Aunt Debby's motherly embrace, with Aunt Debby's arms round her, and Aunt Debby's round, rosy face pressed close to her own.

"Dear, dear! to think I should be holding one of John's children to my heart," said the good lady, wiping away an imaginary tear from her soft, plump cheek. "There, come in, child, you are thrice welcome. How strange it all seems, to be sure;" and chatting away, Aunt Debby led her weary niece into the cosy parlour, where the bright fire and daintily spread table seemed to whisper of warmth and home comforts.

"There, sit down, dear, and let me unfasten your cloak," she continued, placing Nellie on a chair and proceeding to take off her hat with its well soaked plume. "Dear heart! how the child resembles her father! John's very eyes and nose, I declare. Well, well, I'm getting an old woman, and the sight of this fresh, young face warns me of the passing years."

"I think, Debby, you should show Nellie her room and let her refresh herself; there will be ample opportunity for talking to her later on, and the child is wearied with travelling."

Aunt Judith, who had just entered, said this in such a kind voice that it was impossible to take offence, and Miss Deborah, raising her little, twinkling eyes to her sister's face, replied, "Ah! Judith, I need you to look after me still.—I have a sad tongue, my dear (to Nellie), and am apt to chatter when I ought to be silent; come, let me take you to your room now," and off trotted Aunt Debby with an air of the utmost importance.

Nellie followed wearily up the tiny stair with its white matting, and then paused in glad delight as her guide, throwing open a door on one side of the landing, ushered her into a small room. It was simply and plainly furnished, as indeed was everything else in the house; but oh! the spotless purity of the snowy counterpane and pretty toilets. The curtains, looped back with crimson ribbon, fell to the ground in graceful folds. Light sketches and illuminated texts adorned the delicately tinted walls, and on a small table stood an antique vase filled with fairest autumn flowers.

"Are you pleased with your little bedroom, Nellie?" asked Aunt Debby, noting the girl's look of genuine admiration; "there's not much to be seen in the way of grandeur, but it's clean," and practical Miss Deborah emphasized her words by nodding her head vigorously.

"Pleased, Aunt Debby! Why, everything is beautiful. I never had a room all to myself before, and this one is simply lovely. How can I thank you sufficiently for being so good to me?" and there were tears in Nellie's eyes as she spoke.

"Nonsense, my dear," replied the kind woman in her brisk, cheery way; "we are only too pleased to have you with us, and trust you will be happy here;—now, if my tongue is not off again. There—not another word; wash your face and hands, child, then come down to the parlour," and Aunt Debby hurried from the room.

Nellie found the cold water very refreshing, and made her appearance downstairs with a much brighter, cleaner countenance. She found Miss Deborah already seated before the urn, sugaring the cups and adding cream with a very liberal hand; while Aunt Judith lay back on a low rocking-chair looking dreamily into the glowing embers. Both started as the girl entered, and Miss Latimer, rising, placed a chair before the table and bade Nellie be seated, patting her niece's head gently in her slow, kindly fashion, ere she sat down herself and prepared to attend to the young traveller's wants.

Nellie, though tired and home-sick, felt very hungry, and did ample justice to the savoury meal, greatly to Aunt Debby's delight; for that good lady had spared no pains, and had burnt her merry, plump face over the fire, in order to make the supper a success.

Neither aunt troubled her niece with questions, but each talked quietly to the other; and thus left alone, as it were, Nellie found sufficient time to study both faces, and jot down mentally her opinion of each at first sight. One glance at Miss Deborah's rounded contour and twinkling eyes was quite enough; but Miss Latimer's peaceful countenance fascinated the young girl, and seemed to hold her spell-bound. Yet, from a critical point of view, Aunt Judith's was not a pretty face. It was defective in colouring and outline, and there were lines on the quiet brow and round the patient lips; but the look in the eyes—Nellie never forgot that look all her life—it seemed as if Miss Latimer's very soul shone through those dark blue orbs, and revealed the pure, spiritual nature of the woman. A keen physiognomist might have traced the words "I have lived and suffered" in the calm, hushed face with its crown of silver-streaked hair; but Nellie, only a simple child, merely gazed and wondered what it was that made her think Aunt Judith's the most beautiful face she had ever seen.

"Now, dear," said the object of her thoughts, smiling kindly and turning towards her when the dainty repast was over, "I think we shall send you to bed, and after a good night's rest you will be refreshed and ready for school-work to-morrow. Don't trouble removing the plates, Debby; we shall have worship first, and that will free Nellie."

Aunt Debby rose from her chair, handed Miss Latimer the old family Bible, and placing a smaller one in Nellie's lap, reseated herself and waited for Aunt Judith to begin.

A chapter slowly and reverently read, a prayer perfect in its childlike simplicity, then Miss Latimer laid a hand on her niece's shoulder and bade her "Good-night;" whilst Miss Deborah, lighting a candle, led the way as before, and after seeing she required no further service, treated the girl to a hearty embrace, and prepared to depart.

"A good sleep, child. You'll see Aunt Meg tomorrow; this has been one of her bad days, but I expect she will be much better in the morning." These were Aunt Debby's last words, and she bustled away as if fearing to what extent her tongue might lead her.

Nellie undressed, jumped into bed, and then, safely muffled under the warm blankets, cried her homesickness out in the darkness. "O mother, mother," she sobbed, "how I miss you! it is all so strange and lonely. What shall I do?" But even as she wailed in her young heart's anguish, the blankets were gently drawn aside, and a stream of light shining down revealed the flushed tear-stained face on the pillow, and showed Aunt Judith's gentle form bending over the sobbing figure.

"Nellie," she said in that kind voice so peculiarly her own—"Nellie, my child, I was afraid of this;" and putting her arms round the trembling girl, she drew the weary head to her breast, and smoothed the tangled hair with soothing touch. By-and-by the sobs became less violent, and when they had finally ceased Miss Latimer spoke, and her kind words were to the lonely heart as dew to the thirsty flowers.

In after years Nellie found what a precious privilege it was to have a talk with Aunt Judith; and long after, when the brave, true heart had ceased to beat, and the quietly-folded hands spoke of a finished work, she drew from her treasured storehouse the blessed memory of wise, loving counsels, of grand, beautiful thoughts; and carrying them into her daily life, endeavoured to make that life "one grand, sweet song."

"Late again! Winnifred Blake, I am ashamed of you; come, run as fast as you can;" and scolding herself vigorously, Winnie changed her leisurely step to a brisk trot which brought her to the schoolhouse door exactly fifteen minutes after the hour. "Punishment exercise yesterday, and fine to-day—how horrible!" she broke out again, entering the empty dressing-room and surveying the array of hats on the various pegs, all of which seemed to rebuke her tardiness. "Miss Smith will purse up her lips, and utter some cutting sarcasm of course, but I don't care," and Winnie, kicking off her boots, pitched them—well, I don't think she herself knew where. The jacket being next unfastened, she proceeded to divest herself of her hat, and pulled with such violence that the elastic snapped and struck her face severely. Winnie's temper (so Dick declared) resembled nothing so much as a pop-gun, going off, as it were, with a great bang on the least provocation. Flinging the offending article to the other side of the room, and addressing it in anything but complimentary terms, she picked up her books, shook her shaggy mane over her face, and marched straight to the large class-room, where the girls were already busy over their Bible lesson.

"Half-an-hour late, Miss Blake. You really are improving. Allow me to remind you of the fine, also of Mrs. Elder's instructions to take the lowest seat;" and Miss Smith, the senior governess, uttered the words with withering scorn.

"Good-morning," replied the culprit, hiding an angry little heart under a smiling exterior, and slipping her penny into the box on the teacher's desk; "my sleep was slightly broken last night, and that made me late."

Here the girls tittered, and Miss Smith frowned. "Indeed," she commented haughtily; "pray, does your constitution require a stated interval of so many hours for sleep every night?" and the governess laid special stress on the word "every."

"Well, perhaps not," replied Winnie, coolly sitting down and proceeding to unfasten her books; "but I always indulge in an extra half hour if I am disturbed in my slumbers. Broken rest tells sorely on my nervous system, and renders both myself and others miserable."

At this point some of the pupils laughed outright, and Miss Smith's anger rose.

"Silence!" she said, rising and tapping rapidly on the desk. "Miss Blake, you are a disgrace to the school. Attend to your lesson, and let me hear no more rude, impertinent language, or I shall punish you severely," and the governess treated Winnie to one glance of supreme contempt as she spoke.

The child ground her little white teeth together as she gazed on the teacher's sour-faced visage and listened to the tones of her high-pitched voice. "Regular crab-apple, and as cross as two sticks," she muttered, knitting her brow in an angry frown, but smoothing it hastily and calling up the necessary look of attention as Miss Smith cast a swift glance in her direction; "how I should like to tell her every horrid thought in my heart concerning herself. She would be edified," and at the bare idea Winnie shook so much with suppressed merriment that the girl next her opened a pair of bright, hazel eyes and stared in amazement at the audacious child.

The little mischief caught the look, and returning it with interest found she was seated beside the new pupil whose advent had occasioned yesterday's quarrel. There was something very engaging in the frank, open countenance, and Winnie smiled pleasantly as she met the astonished gaze.

"Am I very rude and disobedient?" she asked, or rather whispered roguishly; "you look so shocked and amazed. Please, don't judge by first impressions; my bark is worse than my bite, and I can be a very good girl when I choose. Self-praise is no honour, of course, and I ought to be silent with regard to my various perfections and imperfections; but if you wait patiently you will find out that Winnifred Blake is a most eccentric character, and says and does what no other person would say or do."

Nellie Latimer's astonishment increased as she gazed on this (to her) new specimen of humanity. What a dainty, fairy-like creature she seemed, and what a mischievous gleam was lurking in the depths of those great, shining eyes! Nellie felt quite awkward and commonplace in her presence; however, she managed to say shyly, "I am afraid it is I who have been rude staring at you so; but I did not mean any harm, only you are so different from the other girls."

Winnie gave her an admonishing touch.

"Hush!" she whispered, "the raven is watching us. I mean Miss Smith," as Nellie looked bewildered. "We call her that because she is everlastingly croaking;" and here Winnie, leaning back on her seat, assumed an expression of childlike innocence and solemnity, and appeared to be thoroughly interested in the teacher's explanations.

The lesson proceeded; slowly but surely the hands of the clock moved steadily forward, and at last pointed to the hour, on which Miss Smith, rising, closed her book and dismissed the class with evident feelings of relief.

"Ten minutes' respite, then heigh-ho for a long spell of grammar, etc.," cried Winnie, addressing Nellie as they passed into the hall. "You don't know your lessons to-day of course, and I am so well up in mine that I shall not be able to answer a single word; so come away with me to this quiet nook at the end of the passage and let us enjoy a cosy talk."

The "quiet nook" referred to was a recess at the hall window, partitioned off by a drapery of tapestried curtains. It was a favourite resort of Winnie's, and here the wonderful thoughts, the outbursts of passion, the mischievous plots and schemes, all found free course, and many a childish secret could those heavy folds of curtain have told had they been gifted with tongues wherewith to speak.

Dismissing the other school-fellows who were gathering round, and shooting a triumphant glance at Ada Irvine's haughty face, she half dragged her amused but by no means unwilling companion to the sacred spot; and when both were comfortably perched on the window niche, she began eagerly, "Won't you tell me your name and where you live? I am called Winnifred Mary Blake. I have three big brothers, and a little one; two sisters older than myself; a cross papa and proud step-mamma. We live about a mile from here—No. 3 Victoria Square—and I go home to dinner every day during recess." Having delivered this wonderful announcement in one breath, Winnie paused and waited for her companion to speak.

Nellie smiled as she replied,—

"My name is Helen Latimer, and my home is far away in a country village. I am staying, however, in town with my aunts at present, they live in a small cottage in Broomhill Road."

"Broomhill Road!" echoed Winnie doubtfully; "that is not west, I fancy."

"Oh no, east; I have to take the 'bus, as it is too great a distance to walk daily."

"Not an aristocratic locality," Winnie decided mentally, "and Ada Irvine getting hold of that little fact would use it as a means of exquisite torture to this new girl's sensitive heart. Poor thing! she looks so happy and blithe too." Thinking such thoughts, the mischievous child turned to her companion with a soft, pitying light in her eyes, and holding out a small flake of a hand, said gently,—

"We have not much time at our disposal just now, and I cannot say all I would wish; but you won't find it all plain sailing at school, Nellie, and you will be none the worse of having some one to stand by you, so will you have me for a friend?"

The quaint gipsy face with its framework of wavy hair; the bright, sunny countenance and laughing lips; above all, the soft, childish voice, charmed simple-hearted Nellie, who willingly grasped the hand extended, with these words, "I shall be only too pleased indeed." So the compact was sealed—a compact which remained unbroken through the long months and years that followed. Time and adversity only served to strengthen the bond, and the gray twilight of life found the friends of childhood's days friends still.

"Hark to the bell! are you ready?" asked Winnie, stretching her lazy little form and rising reluctantly from the cosy corner; "now for a long, long lecture on subject and predicate, ugh! How I do hate lessons, to be sure;" and Miss Blake, parting the tapestried curtains, stepped along the hall with a very mutinous face.

Nellie having come to school with the fixed determination to make the most of her time, prepared to listen to the master's instructions with all due attention; but Winnie's incessant fidgeting and yawning baffled every attempt, and the ludicrous answers, given with tantalizing readiness, almost upset her gravity, despite Mr. King's unconcealed vexation.

"This is one of her provoking days," whispered a girl, noting Nellie's puzzled face; "she will tease and annoy each teacher as much as possible all this afternoon—-she always does so when in these moods. Do not think her stupid, Miss Latimer; as the French master often says, 'It is not lack of ability, but lack of application.' She won't learn," and Agnes Drummond, one of Winnie's stanchest allies, shook her head admonishingly at the little dunce as she spoke; but a defiant pout of the rosy lips was the only answer vouchsafed to the friendly warning, and the next moment an absurdly glaring error brought down on Winnie the righteous indignation of her irritated teacher, and resulted in solitary confinement during recess.

Sitting alone in the large empty class-room, the poor child burst into a flood of passionate tears. "It's too bad," she cried rebelliously, wiping her wet eyes and flinging her book aside with contemptuous touch. "There, I can't go home now, and we are to have jam pudding to dinner. Dick will chuckle—horrid boy! and eat my share as well as his own. I know he will, and I do so love those kind of puddings, especially when they are made with strawberry jam. Oh dear, how I envy Alexander Selkirk on his desert island! I am sure he never had any nasty old lessons to learn, and I think he was very stupid to grumble over his solitude when he could do every day simply what he pleased. Well, if I must study, I must; so, here goes," and, drawing the despised grammar towards her once more, Winnie set herself steadily to master part of the contents.

Meanwhile, Nellie, deprived of the companionship of her new friend, was being sharply catechised by Ada Irvine as to her antecedents and general history. The girl at first innocently replied to each question; but after a time she resented the queries, and thereby incurred that young lady's haughty displeasure, and brought down on herself the sharp edge of Ada's sarcastic tongue.

"Not much of a pedigree to boast about, girls," was the final verdict, given with a slight curl of the lip, signifying unbounded contempt,—"the grandfather on the one side a farmer, on the other a draper; the father a poor country doctor; three old maiden aunts living in one of our commonest localities, keeping no servant, doing their own work, and dressing like Quakers. It's a wonder to hear Miss Latimer speak without dropping her h's, or otherwise murdering the Queen's English, ha, ha!" and Miss Irvine shrugged her elegant shoulders scornfully.

"Oh, come, Ada, that is going too far," protested some of the girls, shocked at the rude words and the cool deliberate manner in which they were said; but their insolent school-fellow silenced them with an impatient gesture, as she surveyed the flushed face of her victim and awaited a reply.

Nellie felt both hurt and indignant. She had grown up in her quiet, country home, totally ignorant of the arrogancy and pride so much abroad in the busy world; and coming to school with the expectancy of finding pleasant companions and friends, the words struck home to her heart with a chill.

"How unkind you are!" she murmured, struggling to suppress the angry tears; "you have no right to speak so to me. My aunts are not rich, it is true, and cannot afford to dress so extravagantly as many; but that does not prevent them from being perfect gentlewomen, does it? Your own mother cannot be a more thorough lady than my Aunt Judith, I am sure."

"Is that so?" said Ada with mocking sarcasm, and the contempt in her voice was indescribable. "What presumption! the lower classes are beginning to look up, sure enough."

"Shame!" cried some of the girls standing near; "you are cruel, Ada." But at that moment a slim hand touched Nellie's arm, and a merry voice said soothingly, "Never mind her, Nellie; we all know she is not responsible for her statements at times. Her brain is a little defective on one point," and Winnie's great eyes shot a mischievous glance at Miss Irvine's haughty face.

"May I ask the reason of your special interference just now?" inquired Ada, an angry flush deepening the rose-tint on her cheek; "possibly you wish yesterday's scene to be repeated over again."

"Oh dear, no," answered Winnie brightly, "home-truths seldom need repetition; they are not so easily forgotten. But Nellie is my friend, and I intend to fight her battles as well as my own. Please understand that once for all, and remember at the same time with what metal you have to deal.—Come, Nellie, I am free at last," and the spirited little creature led her weeping school-mate from the room.

"Didn't I warn you not to expect plain sailing?" she continued with a knowing look; "and Ada Irvine is a perfect hurricane. She will swoop down on you at every opportunity, and bluster and blow; but let her alone and never mind."

"I wish I had never left home," replied Nellie, dashing her hand across her eyes and winking away the tear-drops vigorously. "How can girls say such dreadful things? I can't bear them;" and a fresh burst of grief followed.

"Phew!" cried Winnie, giving her an energetic shake, and knitting her brow in a childish frown, "that's babyish. You'll strike on every rock and bend before each gale if you talk in such a fashion. Don't be a fool, Nellie; pluck up some spirit, and show Ada Irvine you're above her contempt." Winnie spoke as if possessed with all the wisdom of the ancients, and gave due emphasis to every word. "She and I are always at what Dick calls 'loggerheads,' and I enjoy an occasional passage of arms amazingly; only, sometimes I come off second on the field, and that is not so pleasant. Now," with a pretty coaxing air, "dry your tears; the hour is almost up, and the bell will be ringing shortly. I hate to see people crying, I do indeed, so please stop;" and Winnie eyed the tear-stained countenance of her friend with mingled sympathy and impatience.

"I daresay I am very silly," replied Nellie, wiping her eyes and scrubbing her wet cheeks with startling vehemence; "anyhow I'll stop now. And thank you for taking my part, Winnie; you'll be a friend worth having, I am sure of that."

"Yes," answered the young girl, a strange dreamy smile playing on her lips, and a soft look gleaming in the mischievous eyes, "I shall be true as steel;" and Nellie never forgot the earnest light on the childish face as Winnie made her simple vow.

It was evening; the daily routine of work was over, and the time come for resting and social enjoyment. The ruby curtains were closely drawn in the cosy parlour at Dingle Cottage; the flames leapt and danced in the polished grate, and the soft lamplight fell with mellowing gleam around. Click, click, went Aunt Debby's needles as she sat by the warm glow, knitting industriously; tick, tick, said the little clock, its pendulum swinging steadily to and fro. The cat purred in sleepy content on the rug; and Aunt Judith's gentle voice fell soothingly on the ear as she read some book aloud from her low seat by Aunt Meg's couch.

Nellie, curled up in the rocking-chair opposite Aunt Debby, rocked herself in lazy comfort, and gazed on her invalid relative with rather a doubtful expression of countenance. Her first impression of Miss Margaret was certainly not favourable; for the girl, though not very keen-sighted, saw how the pale pretty face was marred by lines of peevish discontent, and the brow continually puckered in a fretful frown. She was not old, Nellie decided—not much over thirty, at the very most; but oh, how unlike Aunt Judith! What a contrast there was betwixt that listless, languid form on the sofa, and the quiet figure on the low chair near! Nellie turned with a positive sigh of relief to rest her eyes on Miss Latimer's peaceful countenance and wonder at the marvellous calm that always brooded there.

Every now and then some frivolous demand or complaint would come from the invalid—her pillows required shaking; the fire was too warm; the lamplight not sufficiently shaded; what a noise Aunt Debby's pins were making, and could Aunt Judith not read in a lower tone? Nellie was surprised at Miss Latimer's good-humoured patience, and thoroughly enjoyed Miss Deborah's occasional tart remarks, thrown out in sheer desperation.

"Well, Meg, you would provoke the temper of a saint," she cried, twitching her wool so violently that the thread snapped, and the ball rolled under the table; "there you go grumbling from morning till night, in spite of every endeavour to make you comfortable. Your nurses have a hard time, I assure you, and are to be pitied sincerely."

Miss Margaret's eyes filled, and a flood of tears being imminent, Miss Latimer strove to avert the torrent by saying, "Come, come, Debby; that is strong language to use. You and I great healthy creatures do not know what it is to be confined to a couch day after day, and suffer almost constant pain. I should feel it very hard to be unable to go about and walk in God's beautiful sunshine, and I think one cannot be sufficiently tender and patient towards the sick and helpless."

"Mental pain is harder to bear than physical," quoth practical Miss Deborah, in no way convinced of her harshness by the gentle speech. "If one were to have one's choice, I reckon," with strong Yankeeism, "a headache would be chosen in preference to a heartache," and Aunt Debby nodded her head knowingly.

A white, set look crossed Aunt Judith's face, and a shadow crept into the dark eyes; but they were gone in a moment, and Miss Latimer's lips wore their own sweet smile as she replied, "God grant you may experience little of either, Debby; but if you do, trust me you will find that both bring the richest blessings in their train;" and Aunt Judith's patient face shone with a glad light as she spoke.

"Meg has failed to seize her blessings, then," said Miss Deborah composedly. "No, no, Judith, you are a good woman, but you won't convince me that Margaret is justified in whining and grumbling to the extent she does."

"I need never look for sympathy from you, Debby," broke in the invalid with a low sob; "you are very hard-hearted, but the day will come when all those cruel speeches will rise up and condemn you."

"When?" with provoking gravity.

"When I am no longer here" (low sobs), "and the cold earth hides me for ever from your sight."

"So let it be," retaliated Miss Deborah, coolly proceeding to turn the heel of her stocking, and speaking quite placidly. "I shall remember the amount of exasperation I received when that day comes, and be able to meet the condemnation with becoming fortitude."

"Debby, Debby," said Miss Latimer's voice reprovingly; but the warning came too late. A violent fit of hysterics ensued, and Miss Margaret was borne to her room by the much-enduring sisters, whose services were both required to quell the outburst and settle her comfortably for the night.

Nellie, left alone in the snug parlour, drew her chair closer to the fire, and lifting the cat from its cosy bed on the rug, allowed it to curl up comfortably on her lap. "What a fuss," said the girl, shrugging her shoulders and gazing into the bright, glowing fire. "If I were Aunt Meg, I should be positively ashamed of myself—peevish, cross thing that she is. What a contrast to Aunt Judith;" and here Nellie fell into a fit of musing, which lasted till Miss Deborah came in with the cloth for supper.

"How is Aunt Meg now?" she inquired, watching Aunt Debby bustling about on hospitable thoughts intent. "Is she better?"

"Well, yes," was the reply, given with a little twinkle of the eye; "and a good night's rest will work wonders. You must excuse your aunt this evening, Nellie; she is not always so fretful, and an invalid's life has its hard times."

Miss Deborah spoke earnestly, for although she felt justified in saying a sharp word herself, she could ill brook the idea of any one disparaging or thinking lightly of her invalid sister. Nellie gave a slight nod of assent, which seemed to signify approval of Aunt Debby's words. Nevertheless she retained her own opinion, and mentally condemned poor Miss Margaret as being both weak and silly.

Supper over, Miss Deborah retired to the kitchen, where her reign as queen was undisputed, and Miss Latimer, bidding Nellie bring a small stool and sit down at her feet, began to stroke the soft hair gently, and ask questions as to the day's proceedings.

"Tell me your first impressions, dear child," said the kind voice pleasantly; and the young girl, whose heart still ached at the remembrance of Ada Irvine's stinging words, poured forth the whole story with a force and passion which astonished even herself.

Aunt Judith listened quietly—so quietly, indeed, that Nellie felt half ashamed of her vehemence, and imagined she had been making "much ado about nothing;" but in a few minutes Miss Latimer spoke, and her tones were very tender as she said:—"So my little Nellie has learned that school is not the sunny place she fancied it was. Dear child, I think your new friend gave you very good advice. Don't be a coward, Nellie, and allow your happiness to be marred by the insolent tongue of a spoilt girl. Show her a true lady is characterized, not by outward dress and appearance, but by the innate beauty of heart and soul, and leave your quiet endurance and pleasant courtesy to speak for themselves. Dear, it seems to me as if you were just beginning life now—as if you had but newly entered the lists, and were preparing for that battle which we have all to fight in this world. The warfare is seldom, if ever, an easy one, and the little stings of everyday life are harder to bear than many a heavy trial; but you must determine to be a brave, true soldier, Nellie, and make your life a grand, noble one. You may say to me it is easy to speak, but difficult to act, which I readily grant; but, my child, although the acting may seem almost impossible, we have one Friend ever able and willing to help us. If we choose Him in all sincerity of heart for our Captain, we need not fear to engage in the very thick of the fight."

Aunt Judith paused; and Nellie, seizing the gentle hand which was stroking her head with tender touch, said, "You make me think of my father, auntie; he speaks so often to us just as you are doing now. Every Sabbath evening, when the little ones are in bed, he gathers us round him; and after reading a portion of the Bible, he closes the book and talks in the same way. Oh, I feel so strong and brave while I listen—I feel as if I could face the heaviest sorrow with all courage; but when Monday comes my good resolutions vanish, and I find myself yielding and sinning as before."

The girl gazed straight at her aunt as she spoke, fearing to see a look of disapprobation over her weakness; but Miss Latimer's face was as calm as ever, only the eyes seemed softer and full of such a tender, loving light as she replied,—

"We have most of us the same story to tell, child,—a story of bravery so long as the battle is far off, but of cowardly shrinking when the time for hand-to-hand conflict comes. Whilst the sunshine is all around us and our hearts full of great gladness, we look up and thank the good Father for his precious blessings, feeling nerved for the fiercest fight; but when the storm-clouds gather and the golden brightness is withdrawn, we bow before the blinding tempest and writhe under our pain, unless—and the kind voice spoke very softly—the Master has our hearts in his own safe keeping, unless we have learned to love his will. Then we can discern the bright stars of his love shining through the darkness, and find that the apparently pitiless storm has left diamond drops of blessing behind it. Never despair, Nellie; strive and pray for grace to follow in the Master's footsteps, and you will learn what a grand, noble thing the consecrated life is, and how truly worth living. You know those lines of Kingsley's, do you not?—

'Be good, sweet maid, and let who will be clever;

Do noble things, not dream them all day long;

And so make life, death, and the vast forever,

One grand sweet song.'"

There was a long silence after this, during which Nellie thought deeply, and Aunt Judith lay back in her chair with quietly-folded hands and a far-seeing look in her patient eyes. Then the girl said earnestly, "Aunt Judith, I will try very hard to do my best, I will indeed; and oh, may I come to you when things go wrong, and I can't or won't see the right way? It does me good to have a talk with you, and takes half the home-sickness away. Say yes; please do, dear, dear, dear auntie;" and Nellie's voice sounded very earnest.

"I shall be only too glad, my child," replied Miss Latimer with her rare sweet smile. "Treat me as you would your own mother, dear, and let me help you so far as I am able; only, Nellie, don't depend on your own strength or my aid, but go straight to the Fountain-head, and find the never-failing strength and grace for the needs of every day."

"Thank you, Aunt Judith," was the fervent response; then Aunt Debby entered, and the conversation ceased.

Bedtime came. Nellie retired for the night; Miss Deborah 'followed suit;' and Miss Latimer, extinguishing the light, crossed the tiny hall, and opening a door to the left, entered, and closed it softly behind her.

This, her private sanctum, was like the other apartments—small and plainly furnished, but with the same air of neatness and comfort. A book-case lined one side of the room entirely; a small round table stood close to the window, bright with autumn flowers; a larger one in the centre of the room held a desk, and was strown with papers, magazines, etc.; while soft chairs inviting one to luxurious ease faced the ruddy hearth, and various little nick-nacks scattered here and there showed the graceful touch of a woman's hand.

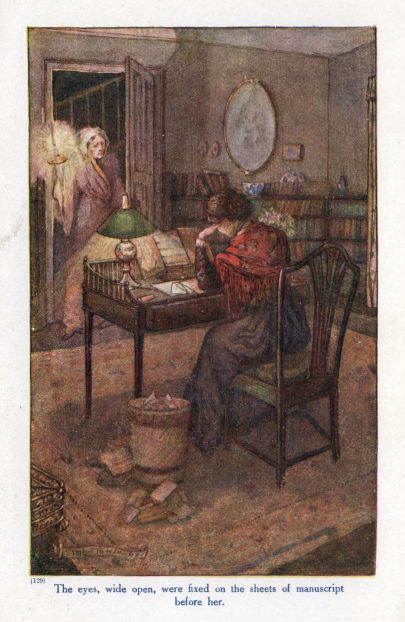

Going to the centre table, Aunt Judith seated herself before the open desk, looked over several closely-written sheets of manuscript, and then furnishing herself with fresh paper, began to write rapidly.

The fire burned slowly out, and the midnight hour had long sounded ere Miss Latimer dried her pen and laid aside her work with a tired sigh. Crossing to the window, she raised the blind, and leaning against the casement, looked away up at the quiet night sky. There was no moon; but the happy stars, shining with frosty brightness, kept their silent watch over the sleeping world. Oh, how still, how very hushed it was! what a great infinite peace seemed brooding over all—a peace such as millions of weary souls were longing to possess; not a sound to be heard, not a ripple of unrest—only that wondrous calm. For a long time Miss Latimer stood drinking in the sweetness and beauty of the nature-world, and letting her thoughts soar up, upwards to the great Father of all, who neither slumbers nor sleeps. What those thoughts were we do not know; but surely some of that vast peace must have stolen softly, silently, into her patient heart, for when she turned away and entered a tiny bedroom leading off from her sanctum, Aunt Judith's face seemed as it were the face of an angel.

Next morning Nellie set out for school in apparently the best of spirits, returning Aunt Judith's encouraging smile with one as bright and hopeful, and shouting a merry farewell as she ran lightly down the garden path and closed the little gate behind her.

Arriving fully ten minutes before the hour, she found several of the girls already assembled in the large class-room, gathered as usual in knots, and talking gaily to one another.

"Good-morning," said Agnes Drummond, coming forward and holding out her hand in a friendly manner. "You are going to be a punctual pupil, Miss Latimer." And the other scholars, not being overpowered as yet by Ada's presence, nodded blithely and allowed their new school-mate to join in the general conversation.

While girlish tongues were busy and the room was filled with the hum of merry voices, the great bell rang loudly, and at the same moment Winnie came rushing in, crying half breathlessly as she did so, "Just in time, girls; not a minute too soon. Good-morning, everybody. Do I look as if I had been having a good race?" and she turned her piquant face round for a general survey.

"A species of milk-maid bloom," said Ada Irvine, catching the words as she leisurely entered the room, "which makes you appear more suited to your friend of the dairy-maid type;" and Miss Irvine looked insolently at Nellie's fresh bright face as she spoke. The soft tints on the smooth, rounded cheek deepened, and the girl bit her lip hard to keep back the angry words.

Not so Winnie, however. Turning a pair of great, serious eyes on her haughty school-mate's fair, placid countenance, she said with an air of prophetic solemnity,—

"Ada Irvine, you will yet be rewarded for all your contemptuous speeches. Mark my words, and see if you don't get smashed up in a railway accident, or fall a victim to that delightfully disfiguring disease—small-pox. Serve you right too. Every dog has its day: you are enjoying yours at present, and can say and do as you please; but—ugh! I'm disgusted at you," and Winnie "tip-tilted" her little nose with the most charming grace imaginable.

Ada smiled loftily.

"I would not be vulgar, if I were you," she remarked calmly. "I suppose you learn all those choice proverbs from your aristocratic brother. Ah, there is Mrs. Elder coming to open the school. Do alter your expression, my dear; you are regarding me with such loving eyes, I am sure she will think you are too affectionate," and Ada swept to her seat with a mocking laugh.

The lessons commenced, and Nellie, thoroughly prepared, almost forgot the morning's annoyance in the joy at finding herself slowly rising to the head of the class, where Miss Irvine sat with all the dignity of an enthroned queen.

Ten minutes' respite; then came the English, conducted by Mr. King, the most thorough and rigid master in the school. A question was asked—a question calculated to tax severely the skill and ingenuity of the active brain. Ada hesitated for one moment, then made a fatal blunder; and Nellie, answering correctly, slipped quietly into the seat of the deposed sovereign. Winnie's delight was indescribable. One triumphant glance after another flashed upwards to the fallen queen's angry face, and her bright eyes fairly danced with wicked joy when, at the close of the class, Mr. King said a few words of commendation on Miss Latimer's abilities.

"Nellie, Nellie! I'm proud of my friend to-day, She's a regular brick, and deserves any amount of hugging and petting. Oh joy, joy! how did you manage it, dear? You have taken the wind out of Ada's sails and gained a feather in your cap, I can assure you. It all seems too good to be true. The queen dethroned at last!" and Winnie catching Nellie round the waist, danced her up and down the schoolroom in a regular madcap whirl.

"You'll be late for dinner if you don't hurry home at once, Win," said one of the elder girls, crossing over to the fire and seating herself by its cheery blaze with a tempting book and box of caramels. "There, run away and don't waste your precious time in speaking uncharitable words, dear. Recess will soon be over;" and Elsie Drummond looked kindly down on the little figure dancing before her with such evident delight.

"I'm just going," replied Winnie, stopping to bestow a smile on the elder girl's pleasant face. "But you can't understand why I am so happy. You don't belong to our set, and therefore know very little about Ada's conceit and—yes, I shall say it—priggish ways. She's just as horrid as can be, and I hate her," wound up the malicious monkey, quite reckless of the character of her language.

"Agnes owns rather a sharp tongue, dear, and I hear many a tale from her," replied Elsie, referring to her younger sister; "but I think, Win, if you wish to be a true friend to Nellie, you will refrain from expressing your joy at her success too openly, at least in Ada's presence. Such unconcealed delight will, believe me, dear, do more harm than good."

"Oh, nonsense, Elsie," was the impetuous reply. "I must sing and dance my joy, it's such a splendid opportunity. Why shouldn't I crow over the nasty proud thing? She needs somebody to ruffle her, and I can do that part better than any one else in the school.—You don't mind my having a little fun, do you, Nellie? she's such a cross-patch, you know."

Now, as was quite natural under the circumstances, Nellie did feel not a little elated over her success. It was a triumph certainly, and girl-like she found it both palatable and pleasant to rejoice over a fallen enemy. At the same time, however, she saw the force of Miss Drummond's caution, and the wisdom of yielding to her advice, so turning to Winnie she answered gently,—

"Please say no more about it; it was all chance, and Ada may gain her old seat to-morrow again, though I mean to try to prevent her from doing so."

But the words were simply wasted on the incorrigible child, who resumed her fantastic war-dance as she replied,—

"No, no; I shall not make any false promise. I mean to be a true, loyal friend, Nell; but if a nice little malicious speech comes gliding softly to the very tip of my tongue, I must let the words out, otherwise there will be choking. Prepare then for sudden squalls," and with a mischievous laugh Winnie vanished from the room, and was soon running along the road in the direction of home.

"The old story—late again," said Dick, looking up from his well-filled plate as she entered and sat down opposite him at the table. "You'll never have time to cram down cabinet pudding and tart to-day, I'll be bound;" and the boy grinned teasingly on the bright face before him.

"Won't I, though?" answered Winnie, nodding her head blithely, and eying the contents of the plate brought to her by Jane the parlour-maid with decided relish. "Don't imagine you'll get my share to-day, Dicky boy, for I'm as hungry as a hawk. I have something to tell you, however, so please listen;" and between mouthfuls she told in a rambling style the story of Nellie's triumph and Ada's defeat, ending with the following words, "Do you know, Dick, when I saw Ada sitting below Nellie and looking so crestfallen, I could have risen there and then and danced for joy before her. Will you believe me, I felt so glad I could hardly restrain my feet till the hour was up, and whenever liberty was proclaimed, didn't they go well at the Irish jig! Oh dear!" and Winnie's face was all aglow as she waited her brother's commendatory remarks on such behaviour.

Dick coughed, blew his nose violently, filled out some water into his glass, quaffed the draught, cleared his throat, and then said gravely, "I'll tell you what to do, Win. This evening, after we have finished studying, I'll teach you a splendid double-shuffle which you will rehearse to-morrow (with added grace, of course,) in front of the lovely Ada, and before all the class—Mr. King included. My eye, what glorious fun!" and vulgar Dick looked across at his sister with beaming face.

"I dare hardly attempt that," she replied dolefully, "though I should dearly love doing so. But you see, Dick" (with energy), "Mrs. Elder detests me so much, and I have been caught in so many faults lately, that such an awful one as you propose would prove fatal. Your delightful plan must be abandoned, I am sorry to say."

"Well, perhaps after all you are right," replied the boy, changing his teasing tone into a serious one. "I daresay Miss Ada's rage would only increase in fury if she saw you performing a triumph-dance and rejoicing so extravagantly over her defeat. I remember a few years ago something of the same kind occurring in our school, and wasn't there a blow-up at the end! I was one of the little chaps then, but I managed to keep my eyes and ears open, and knew more about the whole affair than any one guessed."

"Tell me the story, Dick," interrupted Winnie, holding a spoonful of tart suspended betwixt her mouth and plate, and speaking eagerly; "do, there's a dear boy." But Dick shook his shaggy head, and answered,—

"Not just now, Win. Our time is almost up. Finish your pudding, old girl, and let us away. By-the-by, don't expect me home till after five this afternoon;" and the boy's bright face clouded as he made this statement.

"Why not?" was the inquiry. "We were going to have such splendid fun together. Is there anything wrong?"

"Kept in," uttered in a growling tone. "Lessons as usual badly prepared—denounced for my stupidity, and ordered to remain after hours and work up. See what it is to have a dunce of a brother, Win," and Dick, curling his lip sneeringly, endeavoured to hide his wounded feelings by putting his hands in his pockets and trying to look perfectly indifferent.

Winnie, on her part, burst forth indignantly,—

"Not another word against yourself, Richard Blake. I won't listen." Then coming to her brother's side and slipping two soft arms round his neck, she raised her eyes with the love-light shining so softly in them, and murmured tenderly, "Don't be downcast, dear old boy—all will come right some day; and I am just as stupid as you are."

"No, no," cried Dick quickly. "Indolence is your fault, Win, not stupidity. But I—I can't learn, and that's the simple truth. I've tried over and over again, but it's no good; and, of course," (doggedly) "no one believes that fact."

"I do," said the soft little voice. "But, Dick, people don't know you. There you go," (with quaint gravity) "hiding that great, kind heart of yours, and showing only a rough exterior. Our father and mother never guess bow brave and good and true you are. They'll find all that out some day, however;" and Winnie looked into her brother's honest freckled face with all the affection of her loyal, little heart.

"You're a decided goose, Win," was all the answer vouchsafed to her cheering words, as the boy rose from his chair and prepared to leave the room; but the twinkle in his eye, and kind, firm pressure of his hand, when they parted at the street corner, spoke volumes to little Winnie, and sent her back to school with a happy heart.

She was very thoughtful all that afternoon, however, and so quiet that when school was over and the two girls stood on the steps of Mrs. Elder's Select Establishment, Nellie inquired anxiously if her friend were ill.

"Ill!" repeated Winnie with a light laugh; "not I—only, I've been a-thinking," and a long-drawn sigh accompanied the words.

"What about?" asked her companion, descending the steps and viewing the little figure with the great, serious look on its face. "What a doleful expression, Winnie! You look as if you had, like Atlas, the whole world on your shoulders."

"Nellie," interrupted the child—for indeed she seemed little more than such—with the faintest quiver in her voice, "did you ever think, and think, and think, till your head seemed bursting, and all your thoughts got whirled together? No? Ah, well, I have; and somehow when I get into these moods everything becomes muddled, and I find myself all in a maze. Oh!" and Winnie spoke with passionate vehemence, "often I would give I don't know how much to find some one who could understand and explain away my thoughts."

"Why not speak to your mother?" asked Nellie, rather surprised at this new phase in her friend's character; "surely she should be able to help you."

But the little girl shook her head despondingly. "No, no, Nellie; my stepmother is very kind and pretty, but I don't see much of her, and she would only laugh at me."

They were strolling leisurely along the street now, and the child's voice had a plaintive ring in it as she continued: "I was very ill about a year ago—so ill, Nellie, that I had to lie in bed day after day for a long time. I can't tell what was wrong with me, but I know the doctor used to look very grave when he saw me; and one day, after he had gone away, nurse went about my room crying softly to herself. I was too weak to care or think, and only wondered dreamily what she was crying for, till my stepmother entered, and I noticed that her eyes were red too. They imagined I was sleeping, I suppose, for nurse quite loudly asked, 'Is there no hope?' O Nellie! I shall never forget that moment, never so long as I live. I seemed to realize that I was dying—really, truly dying—and the thought was awful. What would happen to me after death? I could not, I dared not die. Springing with sudden strength from the bed, I tried to rush anywhere, screaming, 'Save me! don't let me die!' in the most awful agony. Then came a long blank. I never forgot that time, but I never spoke of it to any one. Where was the use? I should only have been laughed at, and told to think about living, not dying."

There was something so pathetic in the way all this was told, there was such an amount of pathos in the quivering voice, that Nellie's heart ached and the tears rushed to her eyes.

"Winnie," she began gently, "I know what would do you all the good in the world—a talk with Aunt Judith. I am sure she would never laugh away your thoughts or refuse to listen, she is so good and kind; and when she speaks, one feels as if all one's wicked passions were hushed away."

Winnie brightened visibly.

"Is that so?" she inquired; "then I should dearly like to see her. Won't you invite me to spend some afternoon with you, Nellie, and allow me to see Aunt Judith and your cosy wee home?"

"I shall be only too pleased, Winnie," replied her companion. Then the two friends parted and went their respective roads—one to a fashionable home where gaiety reigned supreme and pleasure filled up every hour; the other to a lowly cottage-dwelling where God's holy name was hallowed, and the Christ-life showed itself clear and bright in Aunt Judith's daily walk.

That same evening Winnie and Dick were alone together in the oak parlour; a room sacred to themselves, where they ate, studied, played, and lived, as it were, a life quite apart from that of the other inmates of the family, who, occupied with business or domestic duties through the day, spent evening after evening in a round of gaiety and amusement. Brother and sister enjoyed little of the society of their elders during the week, but on Saturdays and Sabbaths they were usually expected to lunch with their parents—an honour which, I am sorry to say, neither appreciated; for somehow Dick seldom failed to commit a gross blunder or make some absurd speech at a critical moment, and Winnie, though a general favourite, refused to be happy when he was sternly upbraided for his fault.

The father, a man of wide culture and refinement, had no patience with his son's clumsy movements and slow brain, refusing to look under the surface and see the great loving heart which beat there with its wealth of warm true affection; while Mrs. Blake and the elder brothers and sisters regarded him in the light of a good-for-nothing or general scapegrace. The result was that Dick hid the many sterling qualities of his nature under a gruff, forbidding exterior, and only tender-hearted Winnie guessed how he winced and writhed under the mocking word or light laugh indulged in at his expense. Resenting them bitterly, she gathered up all the love of her passionate little heart and showered it on him, idolizing this big brother of hers to such an extent that even his faults seemed gilded with a halo; and her affection being equally returned, both found their greatest happiness in each other's society.

Oh, what fun they had together in the oak parlour! Oh, the shouts of ringing laughter and the merry jest of words! Now and then Dick would bring home with him his special friend, Archie Trollope, and what a night would follow,—Winnie entering into their games with all the zest of her tomboy nature.

She never felt solitary or out of place in the company of these two boys; and they—why, they looked upon her as one of themselves: Dick describing her to his numerous companions as being a "tip-top" girl, and Archie singing her praises loudly to his own sisters who never knew what it was to join in a madcap frolic, and whose voices were strictly modulated to society pitch.

Sometimes, in the long winter evenings, the trio, tired with play, would lower the gas, and gathering round the large, blazing fire, tell ghost stories with such thrilling earnestness that often the ghastly phantoms seemed to merge almost into reality, and they found themselves starting at a falling cinder or the sound of a footstep in the passage outside. On those occasions the window-blind was usually drawn up to the top, that the pale, glimmering moonlight might stream in; and as the soft silvery beams stole silently into the room and laid their tremulous light on the young forms and awestruck faces, the flames leaping and crackling joined in enhancing the effect of the story by throwing on the walls weird shadows of a moving spectral band.

But the winter days were yet to come, though the cold autumn winds and falling leaves heralded their sure approach; and this evening Winnie and Dick were engaged—not in wandering hand in hand into wonderland, but in the prosaic occupation of making toffy.

Winnie, enveloped in one of nurse's huge bib-aprons, stood at a little distance from the fire, busily studying a book of recipes; while Dick, his honest face burnt to the colour of a lobster, was bending over a saucepan and stirring manfully the tempting contents.

"Yes," said the young lady, laying aside the well-thumbed volume and taking a step forward, "the quantities are correct. I am sure this will be excellent toffy, but—Dick, you shocking boy! whatever are you doing? Licking the spoon, I declare. How very vulgar!" and Winnie opened her eyes in horrified amazement at her brother's lack of good-breeding.

"Well, you see, Win," replied the culprit meekly, "you so often make mistakes and put in some awful compound that I am obliged to guard against being poisoned. Having a sincere affection for life, and not being like Portia 'aweary of this great world,' I consider it my duty to take all due precautions, and therefore pardonnez-moi for tasting the toffy."

The young cook drew her slight figure up and said with an air of offended dignity, "I flatter myself that I am quite capable of making excellent toffy, Richard Blake, and am well aware as to the proper ingredients."

"Doubtless," with a sweeping bow, "but 'accidents will happen in the best-regulated families;' and I remember how you substituted salt for sugar the last time, and apparently never discovered your mistake till you had dosed me with some of the vile concoction. It was cracking stuff, I can assure you." Here Dick became thoroughly convulsed at the remembrance of that disastrous night, and laughed so heartily that Winnie fled to the rescue of her beloved toffy, and seized the spoon from her brother's swaying hand.

"What an object you look!" she said scornfully, stirring the clear brown liquid and inhaling its savoury odour with intense satisfaction. "I don't see anything to laugh at;" and she began to hum the tune of an old nursery rhyme, as if utterly indifferent to both Dick and his laughter.

"Don't ape Madame Dignity, Win," gasped the awful boy in an almost strangled condition; "lofty airs are not becoming to such a little creature. You know perfectly well what a 'go' it was, and thought I was about to 'shuffle off this mortal coil.'" Dick had a weakness for Shakespeare. "Oh dear! when I reflect upon it all and remember the taste—" but here Winnie was obliged to give in and join in his merriment, for the boy's face of pretended disgust was too comical to resist.

"Dick, you are dreadful!" she said at length, the tears streaming down her cheeks and her voice still trembling with a lurking suspicion of laughter. "Will you never forget that eventful night!"

"Never," replied her brother with mock gravity; "the remembrance is printed indelibly on the records of my memory, and the taste remains for ever fresh to my palate. Let us change the conversation, Win; the subject is too much for my delicate constitution."

"I am quite agreeable," quoth the young lady composedly, "and in that case allow your hands to be active and your tongue silent. I want the tin buttered, and the bottle of vanilla essence brought from the pantry. Now, do hurry, for the toffy is almost ready."

Dick obeyed orders, and in a short time the candy was cooling outside on the window ledge, while brother and sister, comfortably settled in their respective chairs, were preparing to enjoy a "quiet read."

"This is a splendid book, Dick," said the little chatterbox, toying with the leaves of her dainty volume, and glancing at the tasteful engravings. "All the school-girls are raving about it, and saying how delightfully interesting the story is."

"What's the name and who's the author?" inquired Dick, too much engrossed in his own book of wonderful adventures to give much heed to his sister's words. "Quick, Win; I'm just killing a whale. Ah! now they've got him. Bravo!" and the boy shouted his appreciation of the stirring tale.

"Oh, the title of the book is 'A Summer's Pleasure;' and the author—let me see—why—" and Winnie stopped short, her eyes opened to their widest extent and her rosy lips slightly parted.

"What's up with the girl?" queried Dick, roused by the little sister's surprised tone and bewildered expression. "Lot's wife could not have looked more petrified, I'll be bound. Do satisfy a fellow's curiosity, Win, and don't sit there mute as a fish."

Thus admonished, Winnie gave herself a little shake and laughed lightly.

"No wonder," she said excusingly. "Only think, Dick,—the author of this book calls herself 'Aunt Judith,' and that is the name of one of Nellie Latimer's aunts."