The Project Gutenberg EBook of In the Rocky Mountains, by W. H. G. Kingston

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: In the Rocky Mountains

Author: W. H. G. Kingston

Illustrator: J.F.

Release Date: May 15, 2007 [EBook #21466]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK IN THE ROCKY MOUNTAINS ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

W H G Kingston

"In the Rocky Mountains"

Chapter One.

How Uncle Jeff came to “Roaring Water”—The situation of the farm—The inmates of the house—My sister Clarice and Black Rachel—Uncle Jeff—Bartle Won and Gideon Tuttle—Arrival of Lieutenant Broadstreet and his men—The troopers quartered in the hut—Our farm-labourers—Sudden appearance of the redskin Winnemak—His former visit to the farm—Clarice encounters him at the spring—Badly wounded—Kindly treated by Clarice and Rachel—His gratitude.

We were most of us seated round a blazing fire of pine logs, which crackled away merrily, sending the sparks about in all directions, at the no small risk of setting fire to garments of a lighter texture than ours. Although the flowers were blooming on the hill-sides, in the woods and valleys, and by the margins of the streams; humming-birds were flitting about gathering their dainty food; and the bears, having finished the operation of licking their paws, had come out in search of more substantial fare; and the buffalo had been seen migrating to the north,—the wind at night blew keenly from off the snow-capped mountain-tops which, at no great distance, rose above us, and rendered a fire acceptable even to us hardy backwoodsmen.

Our location was far in advance of any settlement in that latitude of North America, for Uncle Jeff Crockett “could never abide,” he averred, “being in the rear of his fellow-creatures.” Whenever he had before found people gathering around him at the spot where he had pitched his tent, or rather, put up his log-hut, he had sold his property (always to advantage, however), and yoking his team, had pushed on westward, with a few sturdy followers.

On and on he had come, until he had reached the base of the Rocky Mountains. He would have gone over them, but, having an eye to business, and knowing that it was necessary to secure a market for his produce, he calculated that he had come far enough for the present. He therefore climbed the sides of the mountain for a short distance, until he entered a sort of cañon, which, penetrating westward, greatly narrowed, until it had the appearance of a cleft with lofty crags on either side,—while it opened out eastward, overlooking the broad valley and the plain beyond.

He chose the spot as one capable of being defended against the Redskins, never in those parts very friendly to white men,—especially towards those whom they found settling themselves on lands which they looked upon as their own hunting-grounds, although they could use them for no other purpose.

Another reason which had induced Uncle Jeff to select this spot was, that not far off was one of the only practicable passes through the mountains either to the north or south, and that the trail to it led close below us at the foot of the hills, so that every emigrant train or party of travellers going to or from the Great Salt Lake or California must pass in sight of the house.

A stream, issuing from the heights above, fell over the cliffs, forming a roaring cataract; and then, rushing through the cañon, made its way down into the valley, irrigating and fertilising the ground, until it finally reached a large river, the Platte, flowing into the Missouri. From this cataract our location obtained its name of “Roaring Water;” but it was equally well-known as “Uncle Jeff’s Farm.”

Our neighbours, if such they could be called in this wild region, were “birds of passage.” Now and then a few Indian families might fix their tents in the valley below; or a party of hunters or trappers might bivouac a night or two under the shelter of the woods, scattered here and there; or travellers bound east or west might encamp by the margin of the river for the sake of recruiting their cattle, or might occasionally seek for shelter at the log-house which they saw perched above them, where, in addition to comfortable quarters, abundant fare and a hospitable welcome—which Uncle Jeff never refused to any one, whoever he might be, who came to his door—were sure to be obtained.

But it is time that I should say something about the inmates of the house at the period I am describing.

First, there was Uncle Jeff Crockett, a man of about forty-five, with a tall, stalwart figure, and a handsome countenance (though scarred by a slash from a tomahawk, and the claws of a bear with which he had had a desperate encounter). A bright blue eye betokened a keen sight, as also that his rifle was never likely to miss its aim; while his well-knit frame gave assurance of great activity and endurance.

I was then about seventeen, and Uncle Jeff had more than once complimented me by remarking that “I was a true chip of the old block,” as like what he was when at my age as two peas, and that he had no fear but that I should do him credit; so that I need not say any more about myself.

I must say something, however, about my sister Clarice, who was my junior by rather more than a year. Fair as a lily she was, in spite of summer suns, from which she took but little pains to shelter herself; but they had failed even to freckle her clear skin, or darken her light hair—except, it might be, that from them it obtained the golden hue which tinged it. Delicate as she looked, she took an active part in all household duties, and was now busy about some of them at the further end of the big hall, which served as our common sitting-room, workshop, kitchen, and often as a sleeping-room, when guests were numerous. She was assisted by Rachel Prentiss, a middle-aged negress, the only other woman in the establishment; who took upon herself the out-door work and rougher duties, with the exception of tending the poultry and milking the cows, in which Clarice also engaged.

I have not yet described the rest of the party round the fire. There was Bartle Won, a faithful follower, for many years, of Uncle Jeff; but as unlike him as it was possible that any two human beings could be. Bartle was a wiry little fellow, with bow legs, broad shoulders (one rather higher than the other), and a big head, out of which shone a pair of grey eyes, keen as those of a hawk—the only point in which he resembled Uncle Jeff. He was wonderfully active and strong, notwithstanding his figure; and as for fatigue, he did not know what it meant. He could go days without eating or drinking; although, when he did get food, he certainly made ample amends for his abstinence. He was no great runner; but when once on the back of a horse, no animal, however vicious and up to tricks, had been able to dislodge him.

Gideon Tuttle was another faithful follower of Uncle Jeff: he was a hardy backwoodsman, whose gleaming axe had laid many monarchs of the forest low. Though only of moderate height, few men could equal him in strength. He could fell an ox with his fist, and hold down by the horns a young bull, however furious. He had had several encounters with bears; and although on two occasions only armed with a knife, he had come off victorious. His nerve and activity equalled his strength. He was no great talker, and he was frequently morose and ill-tempered; but he had one qualification which compensated for all his other deficiencies—he was devotedly attached to Uncle Jeff.

There were engaged on the farm, besides these, four other hands: an Irishman, a Spaniard, a negro, and a half-breed, who lived by themselves in a rough hut near the house. Although Uncle Jeff was a great advocate for liberty and equality, he had no fancy to have these fellows in-doors; their habits and language not being such as to make close intimacy pleasant.

The two old followers of Uncle Jeff—although they would have laughed at the notion of being called gentlemen—were clean in their persons, and careful in their conversation, especially in the presence of Clarice.

Just before sunset that evening, our party had been increased by the arrival of an officer of the United States army and four men, who were on their way from Fort Laramie to Fort Harwood, on the other side of the mountains; but they had been deserted by their Indian guide, and having been unable to find the entrance to the pass, were well-nigh worn out with fatigue and vexation when they caught sight of Roaring Water Farm.

The officer and his men were received with a hearty welcome.

“There is food enough in the store, and we will make a shake-down for you in this room,” said Uncle Jeff, wringing the hand of the officer in his usual style.

The latter introduced himself as Lieutenant Manley Broadstreet. He was a fine-looking young fellow, scarcely older than I was; but he had already seen a great deal of service in border warfare with the Indians, as well as in Florida and Texas.

“You are welcome here, friends,” said Uncle Jeff, who, as I have said, was no respecter of persons, and made little distinction between the lieutenant and his men.

At this Lieutenant Broadstreet demurred, and, as he glanced at Clarice, inquired whether there was any building near in which the men could be lodged.

“They are not very fit company for a young lady,” he remarked aside.

He did not, however, object to the sergeant joining him; and the other three men were accordingly ordered to take up their quarters at the hut, with its motley inhabitants.

Their appearance, I confess, somewhat reminded me of Falstaff’s “ragged regiment.” The three varied wonderfully in height. The tallest was not only tall, but thin in the extreme, his ankles protruding below his trousers, and his wrists beyond the sleeves of his jacket; he had lost his military hat, and had substituted for it a high beaver, which he had obtained from some Irish emigrant on the road. He was a German; and his name, he told me, was Karl Klitz. The shortest of the party, Barnaby Gillooly, was also by far the fattest; indeed, it seemed surprising that, with his obese figure, he could undergo the fatigue he must constantly have been called upon to endure. He seemed to be a jolly, merry fellow notwithstanding, as he showed by breaking into a hearty laugh as Klitz, stumbling over a log, fell with his long neck and shoulders on the one side, and his heels kicking up in the air on the other. The last man was evidently a son of Erin, from the few words he uttered in a rich brogue, which had not deteriorated by long absence from home and country. He certainly presented a more soldierly appearance than did his two comrades, but the ruddy blue hue of his nose and lips showed that when liquor was to be obtained he was not likely to let it pass his lips untasted.

The three soldiers were welcomed by the inhabitants of the hut, who were glad to have strangers with whom they could chat, and who could bring them news from the Eastern States.

On coming back to the house, after conducting the three men to the hut, I found the lieutenant and his sergeant, Silas Custis, seated before the fire; the young lieutenant every now and then, as was not surprising, casting a glance at Clarice. But she was too busily occupied in getting the supper-table ready to notice the admiration she was inspiring.

Rachel, with frying-pan in hand, now made her way towards the fire, and begging those who impeded her movements to draw on one side, she commenced her culinary operations. She soon had a huge dish of rashers of bacon ready; while a couple of pots were carried off to be emptied of their contents; and some cakes, which had been cooking under the ashes, were withdrawn, and placed hot and smoking on the platter.

“All ready, genl’em,” exclaimed Rachel; “you can fall to when you like.”

The party got up, and we took our seats at the table. Clarice, who until a short time before had been assisting Rachel, now returned—having been away to arrange her toilet. She took her usual seat at the head of the table; and the lieutenant, to his evident satisfaction, found himself placed near her. He spoke in a pleasant, gentlemanly tone, and treated Clarice in every respect as a young lady,—as, indeed, she was. He now and then addressed me; and the more he said, the more I felt inclined to like him.

Uncle Jeff had a good deal of conversation with Sergeant Custis, who appeared to be a superior sort of person, and had, I suspect, seen better days.

We were still seated at supper when the door opened and an Indian stalked into the room, decked with war-paint and feathers, and rifle in hand.

“Ugh!” he exclaimed, stopping and regarding us, as if unwilling to advance without permission.

“Come in, friend,” said Uncle Jeff, rising and going towards him; “sit down, and make yourself at home. You would like some food, I guess?”

The Indian again uttered a significant “Ugh!” as, taking advantage of Uncle Jeff’s offer, he seated himself by the fire.

“Why, uncle,” exclaimed Clarice, “it is Winnemak!”

But I must explain how Clarice came to know the Indian, whom, at the first moment, no one else had recognised.

Not far off, in a grove of cottonwood trees up the valley, there came forth from the side of the hill a spring of singularly bright and cool water, of which Uncle Jeff was particularly fond; as were, indeed, the rest of us. Clarice made it a practice every evening, just before we returned home from our day’s work, to fetch a large pitcher of water from this spring, that we might have it as cool and fresh as possible.

It happened that one afternoon, in the spring of the previous year, she had set off with this object in view, telling Rachel where she was going; but she had just got out of the enclosure when she caught sight of one of the cows straying up the valley.

“I go after her, Missie Clarice; you no trouble you-self,” cried Rachel.

So Clarice continued her way, carrying her pitcher on her head. It was somewhat earlier than usual; and having no especial work to attend to at home, she did not hurry. It was as warm a day as any in summer, and finding the heat somewhat oppressive, she sat down by the side of the pool to enjoy the refreshing coolness of the air which came down the cañon. “I ought to be going home,” she said to herself; and taking her pitcher, she filled it with water.

She was just about to replace it on her head, when she was startled by the well-known Indian “Ugh!” uttered by some one who was as yet invisible. She at first felt a little alarmed, but recollecting that if the stranger had been an enemy he would not have given her warning, she stood still, with her pitcher in her hand, looking around her. Presently an Indian appeared from among the bushes, his dress torn and travel-stained, and his haggard looks showing that he must have undergone great fatigue. He made signs, as he approached, to show that he had come over the mountains; he then pointed to his lips, to let her understand that he was parched with thirst.

“Poor man! you shall have some water, then,” said Clarice, immediately holding up the pitcher, that the stranger might drink without difficulty. His looks brightened as she did so; and after he had drunk his fill he gave her back the pitcher, drawing a long breath, and placing his hand on his heart to express his gratitude.

While the Indian was drinking, Clarice observed Rachel approaching, with a look of alarm on her countenance. It vanished, however, when she saw how Clarice and the Indian were employed.

“Me dare say de stranger would like food as well as drink,” she observed as she joined them, and making signs to the Indian to inquire if he was hungry.

He nodded his head, and uttered some words. But although neither Clarice nor Rachel could understand his language, they saw very clearly that he greatly required food.

“Come along, den,” said Rachel; “you shall hab some in de twinkle ob an eye, as soon as we get home.—Missie Clarice, me carry de pitcher, or Indian fancy you white slavey;” and Rachel laughed at her own wit.

She then told Clarice how she had caught sight of the Indian coming over the mountain, as she was driving home the cow; and that, as he was making his way towards the spring, she had been dreadfully alarmed at the idea that he might surprise her young mistress. She thought it possible, too, that he might be accompanied by other Redskins, and that they should perhaps carry her off; or, at all events, finding the house undefended, they might pillage it, and get away with their booty before the return of the men.

“But he seems friendly and well-disposed,” said Clarice, looking at the Indian; “and even if he had not been suffering from hunger and thirst, I do not think he would have been inclined to do us any harm. The Redskins are not all bad; and many, I fear, have been driven, by the ill treatment they have received from white men, to retaliate, and have obtained a worse character than they deserve.”

“Dere are bad red men, and bad white men, and bad black men; but, me tink, not so many ob de last,” said Rachel, who always stuck up for her own race.

The red man seemed to fancy that they were talking about him; and he tried to smile, but failed in the attempt. It was with difficulty, too, he could drag on his weary limbs.

As soon as they reached the house Rachel made him sit down; and within a minute or two a basin of broth was placed before him, at which she blew away until her cheeks almost cracked, in an endeavour to cool it, that he might the more speedily set to. He assisted her, as far as his strength would allow, in the operation; and then placing the basin to his lips, he eagerly drained off its contents, without making use of the wooden spoon with which she had supplied him.

“Dat just to keep body and soul togedder, till somet’ing more ’stantial ready for you,” she said.

Clarice had in the meantime been preparing some venison steaks, which, with some cakes from the oven, were devoured by the Indian with the same avidity with which he had swallowed the broth. But although the food considerably revived him, he still showed evident signs of exhaustion; so Rachel, placing a buffalo robe in the corner of the room, invited him to lie down and rest. He staggered towards it, and in a few minutes his heavy breathing showed that he was asleep.

Uncle Jeff was somewhat astonished, when he came in, on seeing the Indian; but he approved perfectly of what Clarice and Rachel had done.

“To my mind,” he observed, “when these Redskins choose to be enemies, we must treat them as enemies, and shoot them down, or they will be having our scalps; but if they wish to be friends, we should treat them as friends, and do them all the good we can.”

Uncle Jeff forgot just then that we ought to do good to our enemies as well as to our friends; but that would be a difficult matter for a man to accomplish when a horde of savages are in arms, resolved to take his life; so I suppose it means that we must do them good when we can get them to be at peace—or to bury the war-hatchet, as they would express themselves.

The Indian slept on, although he groaned occasionally as if in pain,—nature then asserting its sway, though, had he been awake, he probably would have given no sign of what he was suffering.

“I suspect the man must be wounded,” observed Uncle Jeff. “It will be better not to disturb him.”

We had had supper, and the things were being cleared away, when, on going to look at the Indian, I saw that his eyes were open, and that he was gazing round him, astonished at seeing so many people.

“He is awake,” I observed; and Clarice, coming up, made signs to inquire whether he would have some more food.

He shook his head, and lay back again, evidently unable to sit up.

Just then Uncle Jeff, who had been out, returned.

“I suspect that he is one of the Kaskayas, whose hunting-grounds are between this and the Platte,” observed Uncle Jeff; and approaching the Indian, he stooped over him and spoke a few words in the dialect of the tribe he had mentioned.

The Indian answered him, although with difficulty.

“I thought so,” said Uncle Jeff. “He has been badly wounded by an arrow in the side, and although he managed to cut it out and bind up the hurt, he confesses that he still suffers greatly. Here, Bartle, you are the best doctor among us,” he added, turning to Won, who was at work mending some harness on the opposite side of the room; “see what you can do for the poor fellow.”

Bartle put down the straps upon which he was engaged, and joined us, while Clarice retired. Uncle Jeff and Bartle then examined the Indian’s side.

“I will get some leaves to bind over the wound to-morrow morning, which will quickly heal it; and, in the meantime, we will see if Rachel has not got some of the ointment which helped to cure Gideon when he cut himself so badly with his axe last spring.”

Rachel, who prided herself on her ointment, quickly produced a jar of it, and assisted Bartle in dressing the Indian’s wound. She then gave him a cooling mixture which she had concocted.

The Indian expressed his gratitude in a few words, and again covering himself up with a buffalo robe, was soon asleep.

The next morning he was better, but still unable to move.

He remained with us ten days, during which Clarice and Rachel watched over him with the greatest care, making him all sorts of dainty dishes which they thought he would like; and in that time he and Uncle Jeff managed to understand each other pretty well.

The Indian, according to the reticent habits of his people, was not inclined to be very communicative at first as to how he had received his wound; but as his confidence increased he owned that he had, with a party of his braves, made an excursion to the southward to attack their old enemies the Arrapahas, but that he and his followers had been overwhelmed by greatly superior numbers. His people had been cut off to a man, and himself badly wounded. He had managed, however, to make his escape to the mountains without being observed by his foes. As he knew that they were on the watch for him, he was afraid of returning to the plains, and had kept on the higher ground, where he had suffered greatly from hunger and thirst, until he had at length fallen in with Clarice at the spring.

At last he was able to move about; and his wound having completely healed, he expressed his wish to return to his people.

“Winnemak will ever be grateful for the kindness shown him by the Palefaces,” he said, as he was wishing us good-bye. “A time may come when he may be able to show what he feels; he is one who never forgets his friends, although he may be far away from them.”

“We shall be happy to see you whenever you come this way,” said Uncle Jeff; “but as for doing us any good, why, we do not exactly expect that. We took care of you, as we should take care of any one who happened to be in distress and wanted assistance, whether a Paleface or a Redskin.”

Winnemak now went round among us, shaking each person by the hand. When he came to Clarice he stopped, and spoke to her for some time,—although, of course, she could not understand a word he said.

Uncle Jeff, who was near, made out that he was telling her he had a daughter of her age, and that he should very much like to make them known to each other. “My child is called Maysotta, the ‘White Lily;’ though, when she sees you, she will say that that name ought to be yours,” he added.

Clarice asked Uncle Jeff to tell Winnemak that she should be very glad to become acquainted with Maysotta whenever he could bring her to the farm.

Uncle Jeff was so pleased with the Indian, that he made him a present of a rifle and a stock of ammunition; telling him that he was sure he would ever be ready to use it in the service of his friends.

Winnemak’s gratitude knew no bounds, and he expressed himself far more warmly than Indians are accustomed to do. Then bidding us farewell, he took his way to the north-east.

“I know these Indians pretty well,” observed Bartle, as Winnemak disappeared in the distance. “We may see his face again when he wants powder and shot, but he will not trouble himself to come back until then.”

We had begun to fancy that Bartle was right, for many months went by and we saw nothing of our Indian friend. Our surprise, therefore, was great, when he made his appearance in the manner I have described in an earlier portion of the chapter.

Chapter Two.

Winnemak warns us of the approach of Indians—Bartle goes out to scout—No signs of a foe—I take the lieutenant to visit “Roaring Water”—Bartle reports that the enemy have turned back—the Lieutenant delayed by the sergeant’s illness—The visit to the hut—A tipsy trooper—Klitz and Gillooly missing—The lieutenant becomes worse—Search for the missing men—I offer to act as guide to the lieutenant—Bartle undertakes to find out what has become of Klitz and Barney.

“Glad to see you, friend!” said Uncle Jeff, getting up and taking the Indian by the hand. “What brings you here?”

“To prove that Winnemak has not forgotten the kindness shown him by the Palefaces,” was the answer. “He has come to warn his friends, who sleep in security, that their enemies are on the war-path, and will ere long attempt to take their scalps.”

“They had better not try that game,” said Uncle Jeff; “if they do, they will find that they have made a mistake.”

“The Redskins fight not as do the Palefaces; they try to take their enemies by surprise,” answered Winnemak. “They will wait until they can find the white men scattered about over the farm, when they will swoop down upon them like the eagle on its prey; or when all are slumbering within, they will creep up to the house, and attack it before there is time for defence.”

“Much obliged for your warning, friend,” said Uncle Jeff; “but I should like to know more about these enemies, and where they are to be found. We might manage to turn the tables, and be down upon them when they fancy that we are all slumbering in security, and thus put them to the right-about.”

“They are approaching as stealthily as the snake in the grass,” answered Winnemak. “Unless you can get on their trail, it will be no easy matter to find them.”

“Who are these enemies you speak of; and how do you happen to know that they are coming to attack us?” asked Uncle Jeff, who generally suspected all Indian reports, and fancied that Winnemak was merely repeating what he had heard, or, for some reason of his own—perhaps to gain credit to himself—had come to warn us of a danger which had no real existence.

“I was leading forth my braves to revenge the loss we suffered last year, when our scouts brought word that they had fallen in with a large war-party of Arrapahas and Apaches, far too numerous for our small band to encounter with any chance of success. We accordingly retreated, watching for an opportunity to attack any parties of the enemy who might become separated from the larger body. They also sent out their scouts, and one of these we captured. My braves were about to put him to death, but I promised him his liberty if he would tell me the object of the expedition. Being a man who was afraid to die, he told us that the party consisted of his own tribe and the Apaches, who had been joined by some Spanish Palefaces; and that their object was not to make war on either the Kaskayas or the Pawnees, but to rob a wealthy settler living on the side of the mountains, as well as any other white men they might find located in the neighbourhood. Feeling sure that their evil designs were against my friends, I directed my people to follow me, while I hastened forward to give you due warning of what is likely to happen. As they are very numerous, and have among them firearms and ammunition, it may be a hard task, should they attack the house, to beat them off.”

Such in substance was the information Winnemak brought us.

“To my mind, the fellows will never dare to come so far north as this; or, if they do, they will think twice about it before they venture to attack our farm,” answered Uncle Jeff.

“A wise man is prepared for anything which can possibly happen,” said the Indian. “What is there to stop them? They are too numerous to be successfully opposed by any force of white men in these parts; and my braves are not willing to throw away their lives to no purpose.”

Uncle Jeff thought the matter over. “I will send out a trusty scout to ascertain who these people are, and what they are about,” he said at length. “If they are coming this way, we shall get ready to receive them; and if not, we need not further trouble ourselves.”

Lieutenant Broadstreet, who held the Indians cheap, was very much inclined to doubt the truth of the account brought by Winnemak, but he agreed that Uncle Jeff’s plan was a prudent one.

Bartle Won immediately volunteered to start off to try and find the whereabouts of the supposed marauding party. His offer was at once accepted; and before many minutes were over he had left the farm, armed with his trusty rifle, and his axe and hunting-knife in his belt.

“Take care they do not catch you,” observed the lieutenant.

“If you knew Bartle, you would not give him such advice,” said Uncle Jeff. “He is not the boy to be caught napping by Redskins; he is more likely to lay a dozen of them low than lose his own scalp.”

The Indian seeing Bartle go, took his leave, saying that he would join his own people, who were to encamp, according to his orders, near a wood in the valley below. He too intended to keep a watch on the enemy; and should he ascertain that they were approaching, he would, he said, give us warning.

“We can trust to your assistance, should we be attacked,” said Uncle Jeff; “or, if you will come with your people inside the house, you may help us in defending it.”

Winnemak shook his head at the latter proposal.

“We will aid you as far as we can with our small party,” he answered; “but my people would never consent to shut themselves up within walls. They do not understand that sort of fighting. Trust to Winnemak; he will do all he can to serve you.”

“We are very certain of that, friend,” said Uncle Jeff.

The Indian, after once more shaking hands with us, set off to join his tribe.

Lieutenant Broadstreet expressed his satisfaction at having come to the farm. “If you are attacked, my four men and I may be of some use to you; for I feel sure that we shall quickly drive away the Redskins, however numerous they may be,” he observed.

He advised that all the doors and lower windows should be barricaded, in case a surprise might be attempted; and that guards should be posted, and another scout sent out to keep watch near the house, in case Bartle might have missed the enemy, or any accident have happened to him. The latter Uncle Jeff deemed very unnecessary, so great was his confidence in Bartle’s judgment and activity.

Notice was sent to the hut directing the men to come in should they be required, but it was not considered necessary for them to sleep inside the house.

These arrangements having been made, those not on watch retired to rest. But although Uncle Jeff took things so coolly, I suspect that he was rather more anxious than he wished it to appear. I know that I myself kept awake the greater part of the night, listening for any sounds which might indicate the approach of a foe, and ready to set out at a moment’s notice with my rifle in hand,—which I had carefully loaded and placed by my bedside before I lay down. Several times I started up, fancying that I heard a distant murmur; but it was simply the roaring of the cataract coming down the cañon.

At daybreak I jumped up, and quickly dressing, went downstairs. Soon afterwards Gideon Tuttle, who had been scouting near the house, came in, stating that he had seen no light to the southward which would indicate the camp-fires of an enemy, and that, according to his belief, none was likely to appear. In this Uncle Jeff was inclined to agree with him.

Lieutenant Broadstreet now expressed a wish to proceed on his way; at the same time, he said that he did not like to leave us until it was certain that we were not likely to be exposed to danger.

“Much obliged to you, friend,” said Uncle Jeff, “you are welcome to stay here as long as you please; and Bartle Won will soon be in, when we shall know all about the state of affairs.”

It was our custom to breakfast at an early hour in the morning, as we had to be away looking after the cattle, and attending to the other duties of the farm.

The lieutenant happened to ask me why we called the location “Roaring Water.”

“I see only a quiet, decent stream flowing by into the valley below,” he observed.

“Wait until we have a breeze coming down the cañon, and then you will understand why we gave the name of ‘Roaring Water’ to this place,” I answered. “As I can be spared this morning, and there is not much chance of the enemy coming, if you like to accompany me I will take you to the cataract which gives its name to this ‘quiet, decent stream,’ as you call it; then you will believe that we have not misnamed the locality.”

We set off together. The lieutenant looked as if he would have liked to ask Clarice to accompany us; but she was busy about her household duties, and gave no response to his unspoken invitation.

Boy-like, I took a great fancy to the young officer. He was quiet and gentlemanly, and free from all conceit.

I took him to Cold-Water Spring, at which Clarice had met the Indian; and after swallowing a draught from it, we made our way onward over the rough rocks and fallen logs until we came in sight of what we called our cataract. It appeared directly before us, rushing, as it were, out of the side of the hill (though in reality there was a considerable stream above us, which was concealed by the summits of the intervening rocks); then downward it came in two leaps, striking a ledge about half-way, where masses of spray were sent off; and then taking a second leap, it fell into a pool; now rushing forth again foaming and roaring down a steep incline, until it reached the more level portion of the cañon.

“That is indeed a fine cataract, and you have well named your location from it,” observed the lieutenant. “I wish I had had my sketch-book with me; I might have made a drawing of it, to carry away in remembrance of my visit here.”

“I will send you one with great pleasure,” I answered.

“Do you draw?” he asked, with a look of surprise, probably thinking that such an art was not likely to be possessed by a young backwoodsman.

“I learned when I was a boy, and I have a taste that way, although I have but little time to exercise it,” I answered.

He replied that he should be very much obliged. “Does your sister draw?—I conclude that young lady is your sister?” he said in a tone of inquiry.

“Oh yes! Clarice draws better than I do,” I said. “But she has even less time than I have, for she is busy from morning till night; there is no time to spare for amusement of any sort. Uncle Jeff would not approve of our ‘idling our time,’ as he would call it, in that sort of way.”

The lieutenant seemed inclined to linger at the waterfall, so that I had to hurry him away, as I wanted to be back to attend to my duties. I was anxious, also, to hear what account Bartle Won would bring in.

But the day passed away, and Bartle did not appear. Uncle Jeff’s confidence that he could have come to no harm was not, however, shaken.

“It may be that he has discovered the enemy, and is watching their movements; or perhaps he has been tempted to go on and on until he has found out that there is no enemy to be met with, or that they have taken the alarm and beat a retreat,” he observed.

Still the lieutenant was unwilling to leave us, although Uncle Jeff did not press him to stay.

“It will never do for me to hurry off with my men, and leave a party of whites in a solitary farm to be slaughtered by those Redskin savages,” he said.

At all events, he stayed on until the day was so far spent that it would not have been worth while to have started.

Clarice found a little leisure to sit down at the table with her needle-work, very much to the satisfaction of the lieutenant, who did his best to make himself agreeable.

I was away down the valley driving the cattle into their pen, when I caught sight of Bartle coming along at his usual swinging pace towards the farm.

“Well, what news?” I asked, as I came up to him.

“Our friend Winnemak was not romancing,” he answered. “There were fully as many warriors on the war-path as he stated; but, for some reason or other, they turned about and are going south. I came upon their trail after they had broken up their last camp, and I had no difficulty in getting close enough to them to make out their numbers, and the tribes they belong to. The appearance of their camp, however, told me clearly that they are a very large body. We have to thank the chief for his warning; at the same time, we need not trouble ourselves any more on the subject.”

“Have they done any harm on their march?” I asked.

“As to that, I am afraid that some settlers to the south have suffered; for I saw, at night, the glare of several fires, with which the rascals must have had something to do. I only hope that the poor white men had time to escape with their lives. If I had not been in a hurry to get back, I would have followed the varmints, and picked off any stragglers I might have come across.”

“As you, my friends, are safe for the present, I must be off to-morrow morning with my men,” said the lieutenant when I got back; “but I will report the position you are in at Fort Harwood, and should you have reason to expect an attack you can dispatch a messenger, and relief will, I am sure, be immediately sent you.”

I do not know that Uncle Jeff cared much about this promise, so confident did he feel in his power to protect his own property,—believing that his men, though few, would prove staunch. But he thanked the lieutenant, and hoped he should have the pleasure of seeing him again before long.

During the night the sergeant was taken ill; and as he was no better in the morning, Lieutenant Broadstreet, who did not wish to go without him, was further delayed. The lieutenant hoped, however, that by noon the poor fellow might have sufficiently recovered to enable them to start.

After breakfast I accompanied him to the hut to visit the other men. Although he summoned them by name,—shouting out “Karl Klitz,” “Barney Gillooly,” “Pat Sperry,”—no one answered; so, shoving open the door, we entered. At first the hut appeared to be empty, but as we looked into one of the bunks we beheld the last-named individual, so sound asleep that, though his officer shouted to him to know what had become of his comrades, he only replied by grunts.

“The fellow must be drunk,” exclaimed the lieutenant, shaking the man.

This was very evident; and as the lieutenant intended not to set off immediately, he resolved to leave him in bed to sleep off his debauch.

But what had become of the German and the fat Irishman? was the question. The men belonging to the hut were all away, so we had to go in search of one of them, to learn if he could give any account of the truants. The negro, who went by no other name than Sam or Black Sam, was the first we met. Sam averred, on his honour as a gentleman, that when he left the hut in the morning they were all sleeping as quietly as lambs; and he concluded that they had gone out to take a bath in the stream, or a draught of cool water at the spring. The latter the lieutenant thought most probable, if they had been indulging in potations of whisky on the previous evening; as to bathing, none of them were likely to go and indulge in such a luxury.

To Cold-Water Spring we went; but they were not to be seen, nor could the other men give any account of them.

The lieutenant burst into a fit of laughter, not unmixed with vexation.

“A pretty set of troops I have to command—my sergeant sick, one drunk, and two missing.”

“Probably Klitz and Gillooly have only taken a ramble, and will soon be back,” I observed; “and by that time the other fellow will have recovered from his tipsy fit; so it is of no use to be vexed. You should be more anxious about Sergeant Custis, for I fear he will not be able to accompany you for several days to come.”

On going back to the house, we found the sergeant no better. Rachel, indeed, said that he was in a raging fever, and that he must have suffered from a sunstroke, or something of that sort.

The lieutenant was now almost in despair; and though the dispatches he carried were not of vital importance, yet they ought, he said, to be delivered as soon as possible, and he had already delayed two days. As there was no help for it, however, and he could not at all events set out until his men came back, I invited him to take a fishing-rod and accompany me to a part of the stream where, although he might not catch many fish, he would at all events enjoy the scenery.

It was a wild place; the rocks rose to a sheer height of two or three hundred feet above our heads, broken into a variety of fantastic forms. In one place there was a cleft in the rock, out of which the water flowed into the main stream. The lieutenant, who was fond of fishing, was soon absorbed in the sport, and, as I expected, forgot his troubles about his men.

He had caught several trout and a couple of catfish, when I saw Rachel hurrying towards us.

“Massa Sergeant much worse,” she exclaimed; “him fear him die; want bery much to see him officer, so I come away while Missie Clarice watch ober him. Him bery quiet now,—no fear ob him crying out for present.”

On hearing this, we gathered up our fishing-rods and hastened back to the house, considerably outwalking Rachel, who came puffing after us.

We found Clarice standing by the bedside of the sick man, moistening his parched lips, and driving away the flies from his face.

“I am afraid I am going, sir,” he said as the lieutenant bent over him. “Before I die, I wish to tell you that I do not trust those two men of ours, Karl Klitz and Gillooly. I learned from Pat Sperry that they have been constantly putting their heads together of late, and he suspects that they intend either to desert, or to do some mischief or other.”

“Thank you,” said the lieutenant; “but do not trouble yourself about such matters now. I will look after the men. You must try to keep your mind quiet. I hope that you are not going to die, as you suppose. I have seen many men look much worse than you do, and yet recover.”

The sergeant, after he had relieved his mind, appeared to be more quiet. Rachel insisted on his taking some of her remedies; and as evening drew on he was apparently better,—at all events, no worse. Clarice and the negress were unremitting in their attentions, utterly regardless of the fever being infectious; I do not think, indeed, that the idea that it was so ever entered their heads.

The lieutenant had been so occupied with his poor sergeant, that he seemed to have forgotten all about his missing men. At last, however, he recollected them, and I went back with him to the hut.

On the way we looked into the stables, where we found the five horses and baggage-mules all right; so that the men, if they had deserted, must have done so on foot.

We opened the door of the hut, hoping that possibly by this time the missing men might have returned; but neither of them was there. The drunken fellow was, however, still sleeping on, and probably would have slept on until his hut companions came back, had we not roused him up.

“You must take care that your people do not give him any more liquor, or he will be in the same state to-morrow morning,” observed the lieutenant.

We had some difficulty in bringing the man to his senses; but the lieutenant finding a pitcher of water, poured the contents over him, which effectually roused him up.

“Hullo! murther! are we all going to be drowned entirely at the bottom? Sure the river’s burst over us!” he exclaimed, springing out of his bunk. He looked very much astonished at seeing the lieutenant and me; but quickly bringing himself into position, and giving a military salute, “All right, your honour,” said he.

“Yes, I see that you are so now,” said the lieutenant; “but little help you could have afforded us, had we been attacked by the enemy. I must call you to account by-and-by. What has become of your comrades?”

“Sure, your honour, are they not all sleeping sweetly as infants in their bunks?” He peered as he spoke into the bunks which had been occupied by the other men. “The drunken bastes, it was there I left them barely two hours ago, while I jist turned in to get a quiet snooze. They are not there now, your honour,” he observed, with a twinkle in his eye; “they must have gone out unbeknown to me. It is mighty surprising!”

“Why, you impudent rascal, you have been asleep for the last twelve hours,” said the lieutenant, scarcely able to restrain his gravity. “Take care that this does not happen again; keep sober while you remain here.”

“Sure, your honour, I would not touch a dhrop of the cratur, even if they were to try and pour it down me throat,” he answered. “But I found a countryman of mine living here. It is a hard matter, when one meets a boy from Old Ireland, to refuse jist a sip of the potheen for the sake of gintility!”

“Follow me to the house as soon as you have put yourself into decent order,” said the lieutenant, not wishing to exchange further words with the trooper.

Pat touched his hat, to signify that he would obey the order, and the lieutenant and I walked on.

“I cannot put that fellow under arrest, seeing that I have no one to whom I can give him in charge,” said the lieutenant, laughing. “But what can have become of the others? I do not think, notwithstanding what Sergeant Custis said, that they can have deserted. They would scarcely make an attempt to get over this wild country alone, and on foot.”

As soon as Pat made his appearance, the lieutenant ordered him to stand on guard at the door, where he kept him until nightfall.

When our men came in, I inquired whether they knew anything of the troopers. They one and all averred that they had left them sleeping in the hut, and that they had no notion where they could have gone.

“Could the fellows, when probably as drunk as Pat, have fallen into the torrent and been drowned!” exclaimed the lieutenant anxiously.

“Sure, they were as sober as judges,” observed Dan, one of our men. Then an idea seemed to strike him. “To be sure, your honour, they might have gone fishing up the stream. That broth of a boy Barney might jist have rolled in, and the long Dutchman have tried to haul him out, and both have been carried away together. Ill luck to Roaring Water, if it has swallowed up my countryman Barney.”

I suspected, from the way in which Dan spoke, that he had no great belief that such a catastrophe had occurred; in fact, knowing the fellow pretty well, I thought it very probable that, notwithstanding what he said, he was cognisant of the whereabouts of the truants.

Uncle Jeff and the lieutenant examined and cross-examined all the men; but no satisfactory information could be got out of them.

“Whether they come back or not, I must be on my way to-morrow morning with Sperry; while I leave my sergeant under your care, if you will take charge of him,” said the lieutenant.

Uncle Jeff willingly undertook to do this.

“As you are unacquainted with the way, and Pat is not likely to be of much assistance, if Uncle Jeff will allow me I will act as your guide to the mouth of the pass, after which you will have no great difficulty in finding your way to Fort Harwood,” I said to the lieutenant.

He gladly accepted my offer.

“But what about the possibility of the farm being attacked by the Indians? You would not like in that case to be absent, and I should be unwilling to deprive your friends of your aid,” he observed. “If you accompany me, I must leave Sperry to attend on Sergeant Custis, and to come on with him when he is well enough. Although I do not compare the Irishman to you, yet, should the farm be attacked, I can answer for his firing away as long as he has a bullet left in his pouch.”

Uncle Jeff, much to my satisfaction, allowed me to accompany the lieutenant. I had a good horse, too, and had no fears about making my way back safely, even should the country be swarming with Indians.

When the lieutenant spoke of the possibility of the farm being attacked by the Redskins, Uncle Jeff laughed. “They will not venture thus far,” he observed. “But even if they do come, we will give a good account of them. Not to speak of my rifle, Bartle’s and Gideon’s are each worth fifty muskets in the hands of the Indians; our other four fellows, with your trooper, will keep the rest at bay, however many there may be of them. The sergeant, too, will be able to handle a rifle before long, I hope; while Clarice and Rachel will load the arms, and look after any of us who may be hurt. But we need not talk about that; the varmints will not trouble us, you may depend upon it.”

When Bartle Won heard of the disappearance of the troopers, and that we had examined our men, but had been unable to elicit any information from them as to what had become of the truants, he observed,—“Leave that to me. If they know anything about the matter, I will get it out of them before long. As to the fellows having tumbled into the torrent, I do not believe it. They are not likely to have gone off without our people knowing something about it. They are either in hiding somewhere near Roaring Water,—and if so, I shall soon ferret them out,—or else they have gone away to take squaws from among the Indians, and set up for themselves.”

The lieutenant did not think that the latter proceeding was very probable; but their absence was mysterious, and we had to confess that we were no wiser as to their whereabouts than we were at first.

Chapter Three.

My family history—My father, once a captain in the British army, comes to America and marries Uncle Jeff’s sister—He settles on a farm in Ohio—Clarice and I are born—My grandfather’s farm destroyed by a flood—The next year our farm is burnt—My father resolves to migrate to the west—We set off in waggons with an emigrant train—Prosperous commencement of journey—Provisions run short—I witness a buffalo hunt—The emigrants suffer from cholera—My mother dies—Many of the emigrants turn back—My father perseveres—Fiercely attacked by Indians—We keep them at bay—Again attacked, when a stranger comes to our assistance—Clarice gives him a book—He promises to read it—We continue our journey, and reach Fort Kearney—Remain there for some months—My father, though still suffering, insists on setting out again—He soon becomes worse, and dies—I am digging his grave, when an emigrant train comes by—Uncle Jeff is the leader, and we accompany him to Roaring Water.

But the readers of my Journal, if so I may venture to call it, would like to know how Clarice and I came to be at Uncle Jeff’s farm. To do so, I must give a little bit of my family history, which probably would not otherwise interest them.

My father, Captain Middlemore, had been an officer in the English army, but sold out and came to America. Being, I suspect, of a roving disposition, he had travelled through most of the Eastern States without finding any spot where he could make up his mind to settle. At length he bent his steps to Ohio; in the western part of which he had one night to seek shelter from a storm at the farm of a substantial settler, a Mr Ralph Crockett (the father of Uncle Jeff). Mr Crockett treated the English stranger with a hospitality which the farmers of Ohio never failed to show to their guests. He had several sons, but he spoke of one who seemed to have a warm place in his heart, and who had gone away some years before, and was leading a wild hunter’s life on the prairies.

“I should like to fall in with him,” said my father. “It is the sort of life I have a fancy for leading,—hunting the buffalo and fighting the Red Indian.”

“Better stay and settle down among us, stranger,” said Mr Crockett. “In a few years, if you turn to with a will, and have some little money to begin with, you will be a wealthy man, with broad acres of your own, and able to supply the Eastern States with thousands of bushels of wheat. It is a proud thing to feel that we feed, not only the people of our own land, but many who would be starving, if it were not for us, in that tax-burdened country of yours.”

My father laughed at the way in which the Ohio farmer spoke of Old England; but notwithstanding that, he thought the matter over seriously. He was influenced not a little, too, I have an idea, by the admiration he felt for the farmer’s only daughter, Mary Crockett.

My father had the price of his commission still almost intact; and it was looked upon as almost a princely fortune to begin with in that part of the world. So, as he received no hint to go,—indeed, he was warmly pressed to stay whenever he spoke of moving,—he stayed, and stayed on. At last he asked Mary Crockett to become his wife, and promised to settle down on the nearest farm her father could obtain for him.

Mr Crockett applauded his resolution; and he purchased a farm which happened to be for sale only a few miles off, and gave him his daughter for a wife. She had gone to school in Philadelphia, where she had gained sufficient accomplishments to satisfy my father’s fastidious taste; and she was, besides being very pretty, a Christian young woman.

She often spoke of her brother Jeff with warm affection, for he, when at home, had ever showed himself to be a loving, kind brother; indeed, Mary was his pet, and if anybody could have induced him to lead a settled life, she might have done it. He had had, somehow or other, a quarrel with her one day,—little more than a tiff,—so off he went into the woods and across the prairies; and, as it turned out, he never came back. She was not the cause of his going, for he had been thinking about it for a long time before, but this tiff just set the ball rolling.

My parents were perfectly happy in their married life, and might have remained so had it not been for my poor father’s unsettled disposition. I was born, then Clarice; and both my father and mother devoted all the time they could spare from the duties of the farm to our education. Clarice was always a bright, intelligent little creature, and rapidly took in all the instruction she received. My mother’s only unhappiness arose from the thought of sending her to Philadelphia,—where she might have to complete her education, as she wished her to become as perfect a lady as our father was a thorough gentleman. He, being well informed, was able to instruct me, and I made as much progress as my sister. Rough in some respects as were our lives, we found the advantage of this, as we could enjoy many amusements from which we should otherwise have been debarred. Clarice learned to play and sing from our mother; and I was especially fond of drawing, an art in which my father was well able to instruct me.

But our family, hitherto prosperous, were now to suffer severe reverses. My grandfather’s property lay in a rich bottom, and one early spring the floods came and swept away his corn-fields, destroyed his meadows, and carried off his cattle. One of my uncles was drowned at that time, another died of fever caught from exposure, and a third was killed by the fall of a tree. The old man did not complain at God’s dealing with him, for he was a true Christian, but he bowed his head; and he died shortly afterwards, at our house. My father’s property had escaped the floods, but the following summer, which was an unusually dry one, a fire swept over the country. It reached our farm, and although my father had timely notice, so that he was able to put my mother and us into one of the waggons, with the most valuable part of his household property, the rest was enveloped in flames shortly after we had left the house. The next day not a building, not a fence, remained standing. The whole farm was a scene of black desolation.

“We have had a pretty strong hint to move westward, which I have long been thinking of doing,” said my father. “Many who have gone to the Pacific coast have become possessed of wealth in half the time we have taken to get this farm in order. What do you say, Mary?”

Our mother was always ready to do whatever he wished, although she would rather have remained in the part of the country where she was born and still had many friends.

“I should say, let us go eastward, and purchase a small farm in some more civilised district; we can then send our children to school, and be able to see them during the holidays,” she observed.

“We ourselves can give them such schooling as they require,” replied my father. “You will make Clarice as accomplished as yourself, and I will take good care of Ralph. It is not book learning a lad requires to get on in this country. He is a good hand at shooting and fishing, understands all sorts of farm work, and is as good a rider as any boy of his age. He will forget all these accomplishments if we go eastward; whereas if we move westward, he will improve still more. And as he is as sharp as a Yankee, he will do well enough in whatever line he follows.”

The truth was, my father had made up his mind to go in the direction he proposed, and was not to be turned aside by any arguments, however sensible, which my mother might offer. So it was settled that we should make a long journey across the prairie. As for the difficulties and dangers to be encountered, or the hardships to which my mother and Clarice would be exposed, he did not take these into consideration. There are people with minds so constituted that they only see one side of a question; and my father was unhappily one of these.

He proposed to unite himself with some respectable party of emigrants, who would travel together for mutual protection. He considered that they might thus set at defiance any band of Indians, however numerous, which they might encounter.

The two farms were no doubt much inferior in value to what they would have been with buildings, outhouses and fencings, standing crops and stock; yet, even as they stood, they were worth a good sum, for they were already cleared—the chief work of the settler being thus done. However, they realised as much as my father expected, and with a well-equipped train and several hired attendants we set out.

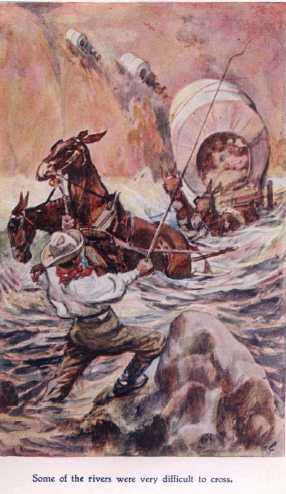

The first part of our journey was tolerably easy; the emigrants were good-humoured, we had abundance of provisions, the country was well watered, and the cattle could obtain plenty of rich grass to keep up their strength. But as soon as we got out of the more civilised districts our difficulties began. Some of the rivers were very difficult to cross, and often there was no small danger of the waggons sticking fast in some spots, or being carried down by the current in others; then we had hills to surmount and rocky ground to pass over, where there was no herbage or water for our beasts.

My father kept aloof as much as possible from the other emigrants, so that we did not hear of the complaints they were making. At last a rumour reached us that the owners of several of the waggons were talking of turning back. We had met at different times two or three trains of people who had given up the journey, and these had declared that the hardships were greater than any human beings could bear; but my father had made up his mind, and go on he would, even if he carried his own waggons alone over the prairie. A few Indians hovered round us at times, but our rifle-shots warned them to keep off; and at night we encamped, under my father’s direction, in military fashion, with the waggons placed so as to form a fortification round the camp.

Our fresh provisions had come to an end, too, and it now became very important that we should procure game.

We had encamped one evening, when several Indians approached, making signs that they were friends. They proved to belong to a tribe which had been at peace with the white people. Our guide knew one of them, and we had no doubt that they could be trusted. They have long since been driven from their old hunting-grounds, and I forget even the name of the tribe. When they heard that we were in want of fresh food, they said that if any of our hunters would accompany them they would show us where buffalo could be found; and that we might either shoot them ourselves, or that they would try to kill some for us.

Few of our people, although hardy backwoodsmen, were accustomed to hunting; and few, indeed, had ever seen any buffalo. But my father, feeling the importance of obtaining some fresh meat, volunteered to go,—directing a light cart to follow, in order to bring back our game,—and I obtained leave to accompany him.

One of the Indians could speak English sufficiently well to make himself understood by us. Talking to my father, and finding that even he had never shot any buffalo, the Indian advised that we should allow him and his people to attack the herd in their own manner, as the animals might take alarm before we could get up to them, and escape us altogether. My father agreed to this, saying that, should they fail, he would be ready with his rifle to ride after the herd and try to bring down one or more of them. This plan was agreed to, and we rode forward.

I observed our Indian friend dismount and put his ear to the ground several times as we rode forward. My father asked him why he did this. He replied that it was to ascertain how far off the buffalo were: he could judge of the distance by the sound of their feet, and their occasional roars as the bulls engaged in combat. Not an animal, however, was yet visible.

At last we caught sight of a number of dark objects moving on the prairie in the far distance.

“There is the herd!” exclaimed the Indian; “we must now be wary how we approach.”

Still we went on, the animals being too busily engaged in grazing, or in attacking each other, to observe us. At last the Indian advised that we should halt behind a knoll which rose out of the plain, with a few bushes on the summit. Here we could remain concealed from the herd. So, having gained the foot of the knoll, we dismounted; and leaving our horses in charge of the men with the cart, my father and I climbed up to the top, where by crouching down we were unseen by the herd, although we could observe all that was going forward.

The Indian hunters now took some wolf-skins which had been hanging to their saddles, and completely covering themselves up, so as to represent wolves, they began to creep towards the herd, trailing their rifles at their sides; thus they got nearer and nearer the herd. Whenever any of the animals stopped to look at them, they stopped also; when the buffalo went on feeding, they advanced. At length each hunter, having selected a cow, suddenly sprang to his knees and fired, and three fine animals rolled over; though, had the buffalo bulls known their power, they might, with the greatest ease, have crushed their human foes. On hearing the shots, the whole herd took to flight.

“Well done!” cried my father. “I should like to have another, though;” and hurrying down the hill, he mounted his horse and galloped off in chase of the retreating herd.

Heavy and clumsy as the animals looked, so rapidly did they rush over the ground that he could only got within range of two or three of the rearmost. Pulling up, he fired; but the buffalo dashed on; and, unwilling to fatigue his horse, my father came back, somewhat annoyed at his failure.

The three animals which had been killed were quickly cut up, and we loaded our cart with the meat; after which the Indians accompanied us back to the camp to receive the reward we had promised. The supply of fresh meat was very welcome, and helped to keep sickness at a distance for some time longer.

After this we made several days’ journey, the supply of fresh provisions putting all hands into better spirits than they had shown for some time. There was but little chance, however, of our replenishing our stock when that was exhausted, for we saw Indians frequently hovering round our camp who were not likely to prove as friendly as those we had before met with, and it would be dangerous to go to any distance in search of game, as there was a probability of our being cut off by them.

We had soon another enemy to contend with, more subtile than even the Redskins. Cholera broke out among the emigrants, and one after another succumbed. This determined those who had before talked of going back to carry out their intentions; and notwithstanding the expostulations of my father and others, they turned round the heads of their cattle, and back they went over the road we had come.

I had by this time observed that my mother was not looking so well as usual. One night she became very ill, and in spite of all my father and two kind women of our party could do for her, before morning she was dead. My father appeared inconsolable; and, naturally, Clarice and I were very unhappy. We would willingly have died with her.

“But we must not complain at what God ordains,” said Clarice; “we must wish to live, to be of use to poor papa. She is happy, we know; she trusted in Christ, and has gone to dwell with him.”

Clarice succeeded better than I did in soothing our poor father’s grief. I thought that he himself would now wish to go back, but he was too proud to think of doing that. He had become the acknowledged leader of the party, and the sturdy men who remained with us were now all for going forward; so, after we had buried our dear mother in a grove of trees which grew near the camp, and had built a monument of rough stones over her grave, to mark the spot, we once more moved forward.

We had just formed our camp the next day, in a more exposed situation than usual, when we saw a party of mounted Indians hovering in the distance. My father, who had not lifted his head until now, gave orders for the disposal of the waggons as could best be done. There were not sufficient to form a large circle, however, so that our fortifications were less strong than they had before been. We made the cattle graze as close to the camp as possible, so that they might be driven inside at a moment’s notice; and of course we kept strict watch, one half of the men only lying down at a time.

The night had almost passed away without our being assailed, when just before dawn those on watch shouted out—

“Here they are! Up, up, boys! got in the cattle—quick!”

Just as the last animal was driven inside our fortifications the enemy were upon us. We received them with a hot fire, which emptied three saddles; when, according to their fashion, they lifted up their dead or wounded companions and carried them off out of the range of our rifles.

Our men shouted, thinking that they had gained the victory; but the Indians were only preparing for another assault. Seeing the smallness of our numbers, they were persuaded that they could overwhelm us; and soon we caught sight of them moving round so as to encircle our camp, and thus attack us on all sides at once.

“Remember the women and children,” cried my father, whose spirit was now aroused. “If we give in, we and they will be massacred; so we can do nothing but fight to the last.”

The men shouted, and vowed to stand by each other.

Before the Indians, however, got within range of our rifles, they wheeled round and galloped off again, but we could still see them hovering round us. It was pretty evident that they had not given up the intention of attacking us; their object being to weary us out, and make our hearts, as they would call it, turn pale.

Just before the sun rose above the horizon they once more came on, decreasing the circumference of the circle, and gradually closing in upon us; not at a rapid rate, however, but slowly—sometimes so slowly that they scarcely appeared to move.

“Do not fire, friends, until you can take good aim,” cried my father, as the enemy got within distant rifle range. “It is just what they wish us to do; then they will come charging down upon us, in the hope of finding our rifles unloaded. Better let them come sufficiently near to see their eyes; alternate men of you only fire.”

The savages were armed only with bows and spears; still they could shoot their arrows, we knew, when galloping at full speed.

At a sign from one of their leaders they suddenly put their horses to full speed, at the same time giving vent to what I can only describe as a mingling of shrieks and shouts and howls, forming the terrific Indian war-whoop. They were mistaken, however, if they expected to frighten our sturdy backwoodsmen. The first of our men fired when they were about twenty yards off. Several of the red warriors were knocked over, but the rest came on, shooting their arrows, and fancying that they had to attack men with empty firearms. The second shots were full in their faces, telling therefore with great effect; while our people raised a shout, which, if not as shrill, was almost as telling as that of the Indian war-whoop. The first men who had fired were ramming away with all their might to reload, and were able to deliver a second fire; while those who had pistols discharged them directly afterwards.

The Indians, supposing that our party, although we had but few waggons, must be far more numerous than they had expected, wheeled round without attempting to break through the barricade, and galloped off at full speed,—not even attempting to pick up those who had fallen.

The women and children, with Clarice, I should have said, had been protected by a barricade of bales and chests; so that, although a number of arrows had flown into our enclosure, not one of them was hurt.

On looking at my father, I saw that he was paler than usual; and what was my dismay to find that an arrow had entered his side! It was quickly cut out, although the operation caused him much suffering. He declared, however, that it was only a flesh wound, and not worth taking into consideration.

The Indians being still near us, we thought it only too probable that we should again be attacked. And, indeed, our anticipations were soon fully realised. In less than half an hour, after having apparently been reinforced, they once more came on, but this time with; the intention of attacking only one side.

We were looking about us, however, in every direction, to ascertain what manoeuvres they might adopt, when we saw to the westward another body of horsemen coming across the prairie.

“We are to have a fresh band of them upon us,” cried some of our party.

“No, no,” I shouted out; “they are white men! I see their rifle-barrels glancing in the sun; and there are no plumes above their heads!”

I was right; and before many minutes were over the Indians had seen them too, and, not liking their looks, had galloped off to the southward.

We received the strangers with cheers as they drew near; and they proved to be a large body of traders.

“We heard your shots, and guessed that those Pawnee rascals were upon you,” said their leader, as he dismounted.

He came up to where my father was lying by the side of the waggon.

“I am sorry to see that you are hurt, friend,” he said. “Any of the rest of your people wounded? If there are, and your party will come on to our camp, we will render you all the assistance in our power.”

“Only two of our men have been hit, and that but slightly; and my wound is nothing,” answered my father. “We are much obliged to you, however.”

“Well, at all events I would advise you to harness your beasts and move on, or these fellows will be coming back again,” said the stranger. “We too must not stay here long, for if they think that our camp is left unguarded they may pay it a visit.” His eye, as he was speaking, fell on Clarice. “Why! my little maiden, were you not frightened at seeing those fierce horsemen galloping up to your camp?” he asked.

“No,” she answered simply; “I trusted in God, for I knew that he would take care of us.”

The stranger gazed at her with surprise, and said something which made her look up.

“Why! don’t you always trust in God?” she asked.

“I don’t think much about him; and I don’t suppose he thinks much about such a wild fellow as I am,” he said in a careless tone.

“I wish you would, then,” she said; “nobody can be happy if they do not trust in God and accept his offer of salvation, because they cannot feel secure for a moment without his love and protection; and they will not know where they are to go to when they die.”

“I have not thought about that,” said the stranger, in the same tone as before; “and I do not suppose I am likely to find it out.”

“Then let me give you a book,” said Clarice, “which will tell you all about it.”

She went to the waggon, and brought out a small Bible.

“There! If you will read that, and do what it tells, you will become wise and happy.”

“Well, my dear, I will accept your book, and do as you advise me. I once knew something about the Bible, before I left home, years and years ago; but I have not looked into one since.”

Without opening the book, the stranger placed it in his breast-pocket; then, after exchanging a few words with my father, who promised to follow his advice, he left the camp and rejoined his companions.

My father, being unable to ride without difficulty, had himself placed in the waggon by the side of Clarice; and the animals being put to, we once more moved on to the westward, while we saw our late visitors take an easterly course.

My father, however, made but slow progress towards recovery; his wound was more serious than he had supposed, and it was too clear that he was in a very unfit state to undergo the fatigue of a journey.

We at length reached Fort Kearney, on the Platte River, where we met with a kind reception from the officers of the garrison, while my father received that attention from the surgeon he so much required. The rest of our party were unwilling to delay longer than was necessary; but the surgeon assured my father that he would risk his life should he continue, in the state in which he then was, to prosecute his journey. Very unwillingly, therefore, he consented to remain,—for our sakes more than his own,—while our late companions proceeded towards their destination. We here remained several months, of course at great expense, as both our men and animals had to be fed, although we ourselves were entertained without cost by our hospitable hosts.

At last another emigrant train halted at the post, and my father, unwilling longer to trespass on the kindness of his entertainers, insisted on continuing his journey with them. The surgeon warned him that he would do so at great risk; observing that should the wound, which was scarcely healed, break out again, it would prove a serious matter. Still, his desire to be actively engaged in forming the new settlement prevailed over all other considerations, and on a fatal day he started, in company with about a dozen other waggons. The owners, who were rough farmers, took very little interest either in my poor father or in us.

We had been travelling for about ten days or a fortnight when my father again fell ill. He tried to proceed in the waggon, but was unable to bear the jolting; and we were at length obliged to remain in camp by ourselves, while the rest of the train continued on the road. Our camp was pitched in an angle formed by a broad stream on the side of a wood, so that we were pretty well protected should enemies on horseback attack us. My father proposed to remain here to await another emigrant train, hoping in a short time to be sufficiently recovered to move on. But, to our great grief, Clarice and I saw that he was rapidly sinking. He himself did not appear to be aware of his condition; and fearing that it would aggravate his sufferings were he to think he was about to leave us, young as we were, in the midst of the wild prairie among strangers, we were unwilling to tell him what we thought.

The men with us began to grumble at the long delay, and declared their intention of moving forward with the next emigrant train which should come by. But what was our dismay, one morning, to find that both the villains had gone, carrying off the cart, and a considerable amount of our property! We were not aware at this time, however, that they had managed to get hold of the chest which contained our money. Our father was so ill, too, that we did not tell him what had occurred; and that very evening, as Clarice and I were sitting by his side holding his hands, he ceased to breathe.

At first we could not persuade ourselves that he was dead. That was indeed a terrible night. I felt, however, that something must be done, and that the first thing was to bury our poor father. We had spades and pick-axes in the waggon, so, taking one of each, I commenced my melancholy task near the banks of a stream.

I was thus engaged when I heard Clarice cry out; and on looking up I saw a small emigrant train passing, which must have been encamped at no great distance from us down the river. Fearing that they might pass without observing us, I ran forward shouting out, entreating the leader to stop. The train immediately came to a standstill, and a man advanced towards me, in whom I soon recognised the person to whom Clarice had given the book many months before.

“Why, my man,” he said, “I thought I knew you! How are your sister and your father? He had got an ugly hurt, I recollect, when I saw him.”

“He is just dead,” I answered.

“Dead!” he exclaimed; “and are you two young ones left on the prairie alone?”

“Yes,” I replied; “our men have made off, and I was going to beg you to take us along with you.”

“That I will do right gladly,” said the stranger.