Adrift.

Page 162.

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Adrift in the Ice-Fields, by Charles W. Hall This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Adrift in the Ice-Fields Author: Charles W. Hall Release Date: May 25, 2007 [EBook #21607] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK ADRIFT IN THE ICE-FIELDS *** Produced by David Clarke, Marcia Brooks and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

To open to the youth of America a knowledge of some of the winter sports of our neighbors of the maritime provinces, with their attendant pleasures, perils, successes, and reverses, the following tale has been written.

It does not claim to teach any great moral lesson, or even to be a guide to the young sportsman; but the habits of all birds and animals treated of here have been carefully studied, and, with the mode of their capture, have been truthfully described.

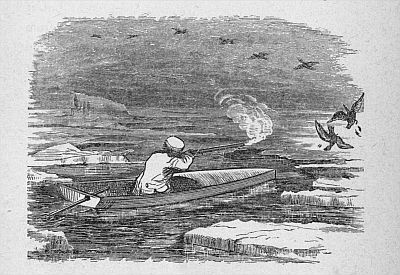

It attempts to chronicle the adventures and misadventures of a party of English gentlemen, during the early spring, while shooting sea-fowl on the sea-ice by day, together with the stories with which they whiled away the long evenings, each of which is intended to illustrate some peculiar dialect or curious feature of the social life of our colonial neighbors.

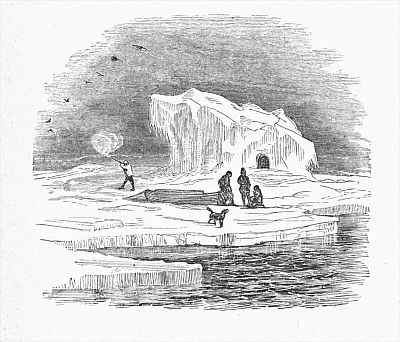

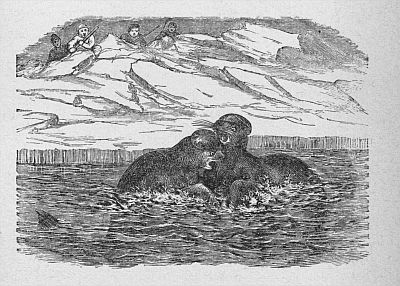

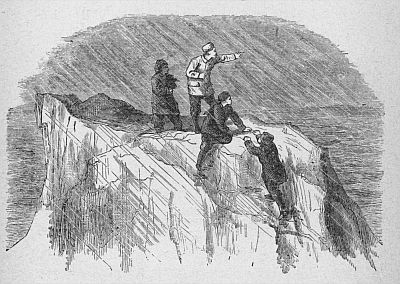

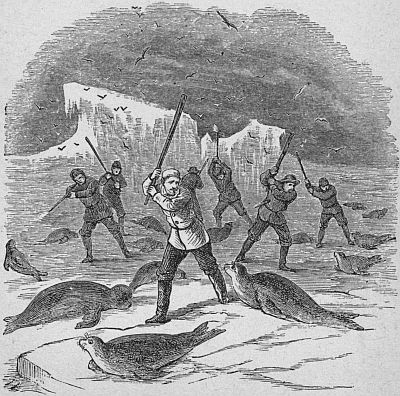

Later in the season the breaking up of the ice carries four hunters into involuntary wandering, amid the vast ice-pack which in winter fills the great Gulf of St. Lawrence. Their perils, the shifts to which they are driven to procure shelter, food, fire, medicine, and other necessaries, together with their devious drift and final rescue by a sealer, are used to give interest to what is believed to be a reliable description of the ice-fields of the Gulf, the habits of the seal, and life on board of a sealing steamer.[Pg 4]

It would seem that the world had been ransacked to provide stories of adventure for the boys of America; but within the region between the Straits of Canso and the shores of Hudson's Bay there still lie hundreds of leagues of land never trodden by the white man's foot; and the folk-lore and idiosyncrasies of the population of the Lower Provinces are almost as unknown to us, their near neighbors.

The descendants of emigrants from Bretagne, Picardy, Normandy, and Poitou, still retaining much of their ancient patois, costume, habits, and superstitions; the hardy Gael, still ignorant of any but the language of Ossian and his burr-tongued Lowland neighbors; the people of each of Ireland's many counties, clinging still to feud, fun, and their ancient Erse tongue, together with representatives from every English shire, and the remnants of Indian tribes and Esquimaux hordes,—offer an opportunity for study of the differences of race, full of picturesque interest, and scarcely to be met with elsewhere.

The century which has with us almost realized the apostolic announcement, "Old things are passed away; behold, all things have become new," with them has witnessed little more than the birth, existence, and death of so many generations, and the old feuds and prejudices of race and religion, little softened by the lapse of time, still remain with their appropriate developments, in the social life of the scattered peoples of these northern shores.

Regretting that the will to depict those life-pictures has not been better seconded by more skill in word-painting, the author lays down his pen, hoping that the pencil of the artist will atone, in some degree, for his own "many short-comings."

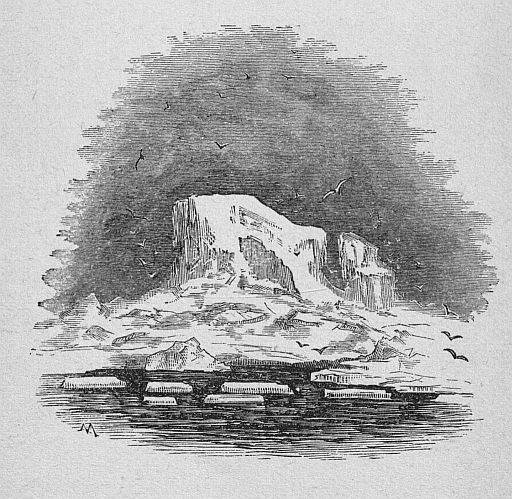

ive hundred miles away to the north and east lies the snug little Island of St. Jean; a beautiful land in summer, with its red cliffs of red sandstone and ruddy clay, surmounted by green fields, which stretch away inland to small areas of the primeval forest, which once extended unbroken from the shores of the Gulf of St. Lawrence to the waters of the Straits of Northumberland.

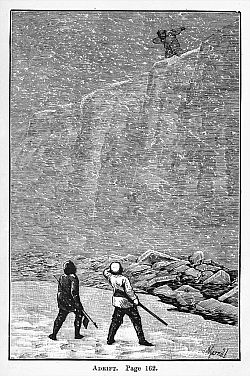

Drear and desolate is it in winter, when the straits are filled with ice, which, in the shape of floe, and berg, and pinnacle, pass in ghostly procession to and fro, as the wind wafts them, or they feel the diurnal impetus of the tides they cover, to escape in time from the narrow limits of the pass, and lose themselves in the vast ice-barrier that for five long months shuts out the havens of St. Jean from the open sea.

No ship can enter the deserted ports, over whose[Pg 10] icy covering the farmer carries home his year's firing, and the young gallant presses his horse to his greatest speed to beat a rival team, or carry his fair companion to some scene of festivity twenty miles away. Many spend the whole winter in idleness; and to all engaged in aught but professional duties, the time hangs heavily for want of enjoyable out-of-door employment. It is, therefore, a season of rejoicing to the cooped-up sportsman when the middle of March arrives, attended, as is usually the case, by the first lasting thaws, and the advent of a few flocks of wild geese.

Among the wealthier sportsmen great preparations are made for a spring campaign, which often lasts six or eight weeks. Decoys of wood, sheet-iron, and canvas, boats for decoy-shooting and stealthy approach, warm clothes, caps, and mittens of spotless white, powder by the keg, caps and wads by the thousand, and shot by the bag, boots and moccasins water and frost proof, and a vast variety of small stores for the inner man, are among the necessaries provided, sometimes weeks in advance of the coming of the few scattering flocks which form, as it were, the skirmish line of the migrating hosts of the Canada goose.

It is usual for a small party to board with some farmer, as near as possible to the shooting grounds, or rather ice, for not infrequently the strong-winged foragers, who press so closely on the rearguard of the retreating frost king, find nothing in the shape of[Pg 11] open water; but after leaving their comrades, dead and dying, amid the fatal decoys on the frozen channels, sweep hastily southward before cold, fatigue, hunger, and the wiles and weapons of man, can finish the deadly work so thoroughly begun.

Such a party of six, in the spring of 186-, took up their quarters with Captain Lund, a pilot, who held the larger portion of the arable land of the little Island of St. Pierre, which lies three miles south of the mouth of the harbor of C., and ends in two long and dangerous shoals, known as the East and West Bars.

The party was composed of Messrs. Risk, Davies (younger and older), Kennedy, Creamer, and La Salle. Mr. Henry Risk was an English gentleman, of about fifty-five years of age, handsome, portly, and genial, a keen sportsman, and sure shot with the long, single, English ducking-gun, to which he stuck, despite of the jeers and remonstrances of the owners of muzzle and breech-loading double barrels.

Davies the elder, an old friend of the foregoing, had for many years been accustomed to leave his store and landed property to the care of his partners and family, while, in company with Risk, he found in the half-savage life and keen air of the ice-fields a bracing tonic, which prepared them for the enervating cares of the rest of the year. The two had little in common—Risk being a stanch Episcopalian, and Davies an uncompromising Methodist. Risk, rather conservative, and his comrade a ready liberal; but they both possessed[Pg 12] the too rare quality of respect for the opinions of others, and their occasional disputations never degenerated into quarrels.

Ben Davies, a nephew of the foregoing, and also a merchant, was an athletic young fellow, of about five feet eight, just entering upon his twenty-second year. A proficient in all manly exercises, and a keen sportsman, he entered into this new sport with all the enthusiasm of youth, and his preparations for the spring campaign were on the most liberal scale of design and expenditure. In these matters he relied chiefly on the skill, experience, and judgment of his right-hand man and shooting companion, Hughie Creamer.

Hughie was of Irish descent, and middle size, but compact, lithe, and muscular, with a not unkindly face, which, however, showed but too plainly the marks of habitual dissipation. A rigger by occupation, a sailor and pilot at need, a skilful fisherman, and ready shot, with a roving experience, which had given him a smattering of half a score of the more common handicrafts, Hughie was an invaluable comrade on such a quest, and as such had been hired by his young employer. It may be added, that a more plausible liar never mixed the really interesting facts of a changeable life with well-disguised fiction; and it may be doubted if he always knew himself which part of some of his favorite "yarns" were truths, and which were due, as a phrenologist would say, "to[Pg 13] language and imaginativeness large, insufficiently balanced by conscientiousness."

Kennedy was a wiry little New Brunswicker, born just across the St. Croix, but a thorough-going Yankee by education, business habits, and naturalization. "A Brahmin among the Brahmins," he believed in the New York Tribune, as the purest source of all uninspired wisdom; and bitterly regretted that the manifold avocations of Horace Greeley had thus far prevented that truly great man from enlightening his fellow-countrymen on the habits and proper modes of capture of the Anser Canadiensis. As, despite his attenuated and dry appearance, there was a deal of real humor in his composition, Kennedy was considered quite an addition to our little party.

La Salle was—Well, reader, you must judge for yourself of what he was, by the succeeding chapters of this simple history, for he it is who recalls from the past these faint pen-pictures of scenes and pleasures never to be forgotten, although years have passed since their occurrence, and the grave has already claimed two of the six,—Risk, the robust English gentlemen, and Hughie, the cheery, ingenious adventurer. It is not easy to draw a fair picture of one's self, even with the aid of a mirror, and when one can readily note the ravages of time in thinning locks and increasing wrinkles, it is hard to speak of the robust health of youth without exaggeration. At that time, however, he was about twenty-three, having[Pg 14] dark hair and eyes, a medium stature, and splendid health. Like Hughie, in a humbler sphere, he was a dabbler in many things,—lawyer, novelist, poet, trader, inventor, what not?—taking life easily, with no grand aspirations, and no disturbing fears for the future. In the intervals of business he found a keen delight in the half-savage life and wholly natural joys of the angler and sportsman, and ever felt that to wander by river and mere, with rod and gun, would enable him to draw from the breast of dear old Mother Earth that rude but joyous physical strength, with the possession of which it is a constant pleasure even to exist.

It was late at night when, by the light of the winter moon, the boats and decoys were unloaded from the heavy sleds, and placed in position on the various bars and feeding-grounds. The ice that season was of unusual thickness, and gave promise of lasting for many weeks. As under the guidance of Black Bill, they entered the farm-yard of his master, the elder Lund, they found the rest of the family just entering the house, and joining them, attacked, with voracious appetites, a coarse but ample repast of bacon, potatoes, coarse bread, sweet butter, and strong black tea. After this guns were prepared, ammunition and lunch got ready for the coming morning, for, with the earliest gleam of the rising sun, they were to commence the first short day of watching for the northward coming hosts of heaven.

[Pg 15]The exact manner in which the ingenious Mrs. Lund managed to accommodate six sportsmen, besides her usual family of four girls, three boys, and a hired man, within the limits of a low cottage of about nine small apartments, has always been an unsolved mystery to all except members of the household. To be sure, Risk and the elder Davies occupied a luxurious couch of robes and blankets in the little parlor, and a huge settle before the kitchen stove opened its alluring recesses to Ben and his man Friday, while one of the elder sons and Black Bill shared with Kennedy and La Salle the largest of the upper rooms. In later years, the question of where the eight others slept, has attained a prominent place among the unsolved mysteries of life; but at that time all were tired enough to be content with knowing that they could sleep soundly, at all events.

Few have ever passed from port to port of the great Gulf, without meeting, or at least hearing, of "Captain Tom Lund," known as the most skilful pilot on the coast.

And when his skill could not make a desired haven, or tide over a threatened danger, the mariners of the Gulf deemed the case hopeless indeed.

Every winter, however, the swift Princess lay in icy bonds, beside the deserted wharves, and the vet[Pg 16]eran pilot went home to his farm, his little house with its brood of children, his shaggy horses, Highland cows, and long-bodied sheep, and became as earnest a farmer as if he had never turned a vanishing furrow on the scarless bosom of the ocean. Always pleasant, anxious to oblige, careful of the safety of his guests, and with a seaman's love of the wonderful and marvellous, he played the host to general satisfaction, and in the matter of charges set an example of moderation such as is seldom imitated in this selfish and mercenary world.

After supper, however, on this first evening, an unwanted cloud hung over the brow of the host, which yielded not to the benign influence of four cups of tea, and eatables in proportion; withstood the sedative consolations of a meerschaum of the best "Navy," and scarcely gave way when, with the two eldest of the party, he sat down to a steaming glass of "something hot," whose "controlling spirit" was "materialized" from a bottle labeled "Cabinet Brandy." After a sip or two, he hemmed twice, to attract general attention, and said, solemnly,—

"It is nonsense, of course, to warn you, gents, of danger, when the ice is so thick everywhere that you couldn't get in if you tried; but mark my words, that something out of the common is going to happen this spring, on this here island. I went over to the Pint, just now, after you came into the yard, to look up one of the cows, and saw two men in white walking up the[Pg 17] track, just below the bank. I thought it must be some of you coming up from the East Bar, but all of a sudden the men vanished, and I was alone; and when I came into the yard, you were all here! Now something of the kind almost always precedes a death among us, and I shan't feel easy until your trip is safely over, and you are all well and comfortable at home."

"Now, Lund," said the elder Davies, "you don't believe in any such nonsense, do you?"

"Nonsense!" said Lund, quietly but gravely; "little Johnnie there, my youngest boy, will tell you that he has often seen on the East Bar the warning glare of the Packet Light, which often warns us of the approach of a heavy storm. It is nearly thirty years since it first glowed from the cabin windows of the doomed mail packet, but to all who dwell upon this island its existence is beyond doubt. Few who have sailed the Gulf as I have, but have seen the Fireship which haunts these waters, and more than once I have steered to avoid an approaching light, and after changing my course nearly eight pints, found the spectre light still dead ahead. No, gentlemen, I shan't slight the warning. If you value life, be careful; for if we get through the breaking up of the ice without losing two men, I shall miss my guess."

"Come, Tom," said Risk, quickly, "don't depress the spirits of the youngsters with such old-world[Pg 18] superstitions. As you say, they couldn't get through the ice now if they would, without cutting a hole; and when the ice grows weak, will be time enough for you to worry. Take another ruffle to your night-cap, Tom, and you youngsters had better get to bed, and prepare to take to the ice at six o'clock, after a cup of hot coffee and a lunch of sandwiches. Here's luck all round, gentlemen."

The toasts were drank by the three elderly men, and re-echoed by the younger ones, who chose not to avail themselves of the proffered stimulant, and then all sought repose in their allotted quarters. Fifteen minutes later the house was in utter darkness and silence, through which the varied breathings of sixteen adults and children would have given ample opportunities for comparison to any waking auditor, had such there been; but no one kept awake, and to all intents and purposes "silence reigned supreme."

t daybreak the gunners arose, and without disturbing the members of the family, took some strong, hot coffee, prepared by the indefatigable Creamer, and ate a breakfast, or rather lunch, of cold meats and bread and butter, after which all proceeded to don their shooting costume, which, being unlike that worn in any other sport, is worthy of description here.

In ice-shooting, every color but pure white is totally inadmissible; for the faintest shade of any other color shows black and prominent against the spotless background of glittering ice-field and snow-covered cliffs. Risk and his partner wore over their ordinary clothing long frocks of white flannel, with white "havelocks" over their seal-skin caps, and their gray, homespun pants were covered to the knee by seal-skin Esquimaux boots—the best of all water-proof walking-gear for cold weather. Risk carried the single ducking-piece before mentioned, but Davies had a Blissett breech-loading double-barrel. They had[Pg 20] chosen their location to the north of the island, near a channel usually opening early in the season, but now covered with ice that would have borne the weight of an elephant. With much banter as to who should count first blood, the party separated at the door; the younger Davies and Creamer, with Kennedy and La Salle, plunging into the drifted fields to the eastward, and in Indian file, trampling a track to be daily used henceforward, until the snows should disappear forever. The two former relied on over-frocks of strong cotton, and a kind of white night-caps, while La Salle wore a heavy shooting-coat of white mole-skin, seal-skin boots reaching to the knee, and armed with "crampets," or small iron spikes, to prevent slipping, while a white cover slipped over his Astrachan cap, completed his outre costume. Kennedy, however, outshone all others in the strangeness of his shooting apparel. Huge "arctics" were strapped on his feet, from which seemed to spring, as from massive roots, his small, thin form, clad in a scanty robe de chambre of cotton flannel, surmounted by a broad sou'wester, carefully covered by a voluminous white pocket handkerchief. The general effect was that of a gigantic mushroom carrying a heavy gun, and wearing a huge pair of blue goggles.

La Salle alone of the four carried a huge single gun of number six gauge, and carrying a quarter of a pound of heavy shot to tremendous distances. The others used heavy muzzle-loading double-barrels. A[Pg 21] brisk walk of fifteen minutes brought them to the extremity of the island, and from a low promontory they saw before them the Bay, and the East Bar, the scene of their future labors.

Below them the Bar, marked by a low ridge, rising above the level of the lower shallows,—for the tide was at ebb,—trended away nearly a league into the spacious bay, covered everywhere with ice, level, smooth, and glittering in the rising sun, save where, here and there, a huge white hummock or lofty pinnacle, the fragments of some disintegrated berg, drifted from Greenland or Labrador, rose along the Bar, where the early winter gales had stranded them. Leaping down upon the ice-foot, the party hastened to their respective stands, nearly a mile out on the Bar—Davies being some four hundred yards from that of La Salle.

The "stand" of the former was a water-tight box of pine, painted white, and about six feet square by four deep, which was quickly sunk into the snow-covered ice to about half its depth; the snow and ice removed by the shovel, being afterwards piled against the sides, beaten hard and smooth, and finally cemented by the use of water, which in a few moments froze the whole into the semblance of one of the thousands of hummocks, which marked the presence of crusted snow-drifts on the level ice.

La Salle, however, had provided better for comfort and the vicissitudes of sea-fowl shooting; occu[Pg 22]pying a broad, flat-bottomed boat, furnished with steel-shod runners, and "half-decked" fore-and-aft, further defended from the sea and spray by weather-boards, which left open a small well, capable of seating four persons. Four movable boards, fastened by metal hooks, raised the sides of the well to a height of nearly three feet, and a fifth board over the top formed a complete housing to the whole fabric. La Salle and Kennedy swung the boat until her bow pointed due east, leaving her broadsides bearing north and south; and then, excavating a deeper furrow in the hollow between two hummocks, the boat was slid into her berth, and the broken masses of icy snow piled against and over her, until nothing but her covering-board was visible.

A huge pile of decoys stood near, of which about two dozen were of wood, such as the Micmac Indian whittles out with his curved waghon, or single-handed draw-knife, in the long winter evenings. He has little cash to spend for paint, and less skill in its use, but scorches the smooth, rounded blocks to the proper shade of grayish brown, and, with a little lampblack and white lead, using his fore-finger in lieu of a brush, manages to imitate the dusky head and neck with its snowy ring, and the white feathers of breast and tail.

These rude imitations, with some more artistic ones, painted in profile on sheet-iron shapes, of life-size, and a few cork-and-canvas "floaters," were quickly[Pg 23] placed in a long line heading to the wind, which was north-west, and tailing down around the boat, the southernmost "stools" being scarce half a gun-shot from the stands.

By the time these arrangements were completed it was nearly midday, and the sky, so clear in the morning, had become clouded and threatening. The chilly north-west breeze, which had made the shelter of their boats very desirable, had died away, and a calm, broken only by variable puffs of wind, succeeded.

"We shall have rain or snow to-night," remarked La Salle to Kennedy, who, after a few moments of watching, had curled himself down in the dry straw, and begun to peruse a copy of the Daily Tribune, his inseparable companion.

"Yes, I dare say. Greeley says—"

What Greeley said was never known, for at that moment a distant sound rung like a trumpet-call on the ear of La Salle, and amid the gathering vapors of the leaden eastern sky, his quick eye marked the wedge-like phalanx of the distant geese, whose leader had already marked the long lines of decoys, which promised so much of needed rest and welcome companionship, but concealed in their treacherous array nothing but terror and death.

"There they are, Kennedy! Throw your everlasting paper down, and get your gun ready. Put your ammunition where you can get at it quick; if[Pg 24] you want to reload. Ah, here comes the wind in good earnest!"

A gust of wind out of the north-east whistled across the floes, and the next moment a thick snow-squall shut out the distant shores, the lowering icebergs, the decoys of their friends, in fact, everything a hundred yards away.

"Where are the geese?" asked Kennedy, as, with their backs to the wind, the two peered eagerly into the impenetrable pouderie to leeward.

"They were about two miles away, in line of that hummock, when the squall set in. I'll try a call, and see if we can get an answer."

"Huk! huk!" There was a long silence, unbroken save by the whistle of the blasts and the metallic rattle of the sleety snow:

"Ah-huk! ah-huk! ah—"

"There they are to windward. Down, close; keep cool, and fire at the head of the flock, when I say fire!" said La Salle, hurriedly, for scarce sixty yards to windward, with outstretched necks and widespread pinions, headed by their huge and wary leader, the weary birds, eager to alight, but apprehensive of unseen danger, swung round to the south-west, and then, setting their wings, with confused cries, "scaled" slowly up against the storm to the hindmost decoy.

"Hŭ-ŭk! hŭ-ŭk!" called La Salle, slowly and more softly.[Pg 25]

"Huk! hū-uk!" answered the huge leader, not a score of yards away, and scarce ten feet from the ice.

"Let them come until you see their eyes. Keep cool! aim at the leader! Ready!—fire!"

Bang! bang! roared the heavy double-barrel, as the white snow-cloud was lit up for an instant with the crimson tongues of levin-fire, and the huge leader, with a broken wing, fell on the limp body of his dead mate. Bang! growled the ponderous boat-gun, as it poured a sheet of deadly flame into the very eyes of the startled rearguard.

A mingled and confused clamor followed, as the demoralized flock disappeared in the direction of the next ice-house, from which, a few seconds later, a double volley told that Davies and Creamer had been passed, at close range, by the scattered and frightened birds.

La Salle reloaded, and then leaped upon the ice, and gave chase to the gander, which he soon despatched, and returning, picked up Kennedy's other bird, with three which lay where "the Baby" had hurled her four ounces of "treble B's." Composing the dead bodies in the attitude of rest among the other decoys, he returned to the boat, and for the first time perceived that the geese were not the only bipeds which had suffered in the late bombardment.

Leaning over the side-boards of the boat, the fastenings of which were broken or unfastened, appeared Kennedy, apparently engaged in deep meditation, for[Pg 26] his head was bowed until the broad rim of his preposterous head-covering effectually concealed his face from view.

"Here, Kennedy, both your birds are dead, and noble ones they are."

"I'm glad of it, for I'm nearly dead, too," came in a melancholy snuffle from the successful shot, at whose feet La Salle for the first time perceived a huge pool of blood.

"Good Heavens! are you hurt? Did your gun burst?" asked La Salle, anxiously.

"No, I've nothin' but the nose-bleed and a broken shoulder, I reckon. Braced my back against that board so as to get good aim, and I guess the pesky gun was overloaded; and when she went off it felt like a horse had kicked me in the face, and the wheel had run over my shoulder."

"Didn't you know better than to put your shoulder between the butt of a gun like that and a half ton of ice?" asked La Salle. "Why, you've broken two brass hooks, and knocked down all the ice-blocks on that side. Can't I do anything to stop that bleeding? Lay down, face upward, on the ice. Hold an icicle to the back of your neck."

"No, thank you; I guess it will soon stop of itself. A little while ago I cut some directions for curing nose-bleed out of the Tribune, and I guess they're in my pocket-book. Yes, here they are: 'Stuff the nostrils with pulverized dried beef, or insert a small plug[Pg 27] of cotton-wool, moistened with brandy, and rolled in alum.' I'll carry some brandy and alum the next time I go goose-shooting."

"Or provide a lunch of dried beef," laughed La Salle; "but you had better keep your shoulder free after this, and you'll have no trouble. There, the bleeding has stopped, and you'd better load up, while I clean away this blood, and cover the boards with clean ice."

In a short time the marks of the disaster were removed, and the hunters again took shelter from the increasing storm, which had set in harder than ever. The snow, however, inconvenienced the friends but little, and as Kennedy could not read, they talked over the cause of his little accident.

"I had no idea that a gun could kick with such force. I shan't dare to fire her again, if another flock puts in an appearance," said the disabled goose-shooter.

"Had your shoulder been free, you would not have felt the recoil, which, even in a heavy, well-made gun, is equal to the fall of a weight fifty to sixty pounds from a height of one foot, and in overloaded or defective guns, exceeds twice and even three times that. It is a wonder that your shoulder was not broken, and a still greater wonder that you killed your birds."

At this moment a hail came from the direction of the other boat, which was answered by La Salle, and in a few moments, after several halloos and replies,[Pg 28] two human forms were seen through the scud, and Ben and Creamer made their appearance, gun in hand. A brace of geese, held by the necks, dangled by the side of the latter, and showed that their shots had not been thrown away.

"This storm will last all night," said Davies, anxiously, "and we're only an hour to sundown. Creamer, here, started a little while ago to find out what you had shot. He lost his way, and was going right out to sea past me, when I called to him, and I thought we had better try to get ashore before it gets any darker."

"Does any one know in just what direction the Point lies?" asked Creamer, with that "dazed" expression peculiar to persons who have been "lost."

"Our boat lies nearly in a direct line east and west, and a line intersecting her stem and stern will fall a few rods inside of the island. We are about three quarters of a mile from the house, and by counting thirteen hundred and twenty paces in that direction, we should find ourselves near the shore, just below the house, if our course was correct," said La Salle.

"Yes," said Creamer, "but no man can keep a straight line in a storm like this, when one hummock looks just like another, and there isn't a star to lay one's course by."

"I once saw in the Tribune," said Kennedy, eagerly, "a way to lay a farm-line by poles stuck in[Pg 29] the ground. It also recommended 'blazing' trees in the woods for the same purpose."

"To blazes with yer poles and blazed trees, Mr. Kennedy, saving yer presence; all the newspapers in Boston can't teach me anything in laying a straight line where I can have or make marks that can be seen; but there are no poles here, and we couldn't see them if we had them."

"Creamer, don't get so desperate. Kennedy has furnished the idea, and I think I can get the party ashore without any trouble. Now let all get ready to start, and I'll lay the course for the others."

In a few moments the decoys were stacked to prevent drifting, and the boat covered so that no snow could penetrate. A pair of small oars were first, however, removed, which were set upright at either extremity of the boat, and in direct line with the keel.

"There is our proper direction," said La Salle. "Now, Creamer, take your birds, gun, and one decoy, and align yourself with these oars when you have counted one hundred paces. When you have done so, face about and turn the beak of the decoy towards the boat. Now, Ben," continued he, when this was done, "walk up within twenty yards of Creamer, and let me align you; Kennedy will go with you, and, counting one hundred paces beyond Creamer, will be aligned by you. You will then be relieved by me, and placing yourself behind Kennedy, will direct[Pg 30] Creamer to the right position, when he has paced one hundred yards farther. At every other hundred yards an iron decoy must be placed, pointing towards the boat."

The plan thus conceived was carried out until thirteen hundred paces had been counted, when La Salle, begging all to keep their places, hurried to the front. It was now nearly dark, and nothing but driving snow was anywhere visible. Creamer was at the lead, but disconsolate and terrified, having utterly lost his reckoning.

"We're astray, sir, completely," he said, hopelessly. "Mother of Heaven!" he ejaculated, as a dim radiance shone through the scud a little to their rear, "there's the 'Packet Light,' and we are lost men."

Buffeted by the heavy gusts and sharp sleet which froze on the face as it fell, La Salle felt for a moment a thrill of the superstitious fear which had overcome the usually stout nerves of his companion; but his cooler nature reasserted itself, although he knew that no house stood in the direction of the mysterious light, which seemed at times almost to disappear, and then to shine with renewed radiance.

"There is nothing earthly about that thing, sir. Macquarrie's house is a long piece from the shore, and Lund's is hidden by the woods. See; look there, sir, for the love of Heaven!" and the stout sailor trembled like a child as the light, describing a sharp curve, rose ten or twelve feet higher into the air,[Pg 31] where it seemed to oscillate violently for a few seconds, and then to be at rest.

"Let us hail it, any way," said La Salle; "perhaps we have made some house on the opposite shore."

"We haven't gone a mile, sir; and as for hailing that, sir, I'd as soon speak the Flying Dutchman, and ask her captain aboard to dinner."

"Well, I'll try it, anyhow.—'Halloo! Light, ahoy!'" he shouted, placing his hands so as to aid the sound against the wind, which blew across the line of direction between them and the mysterious light. Again and again the hail was repeated, but no answer followed.

"You may call until doomsday, but they who have lit that lamp will never answer mortal hail again. They died thirty falls ago, amid frost and falling snow, ay, and foaming breakers, on this very bar, and the men on shore saw the light shiver, and swing, and disappear, as we saw it just now."

"Well, I don't believe in that kind of light, and I, for one, am going to see what it is. Now, don't move from your place, but watch the light, and if you hear the report, or see the flash, of my gun, answer it once with both barrels, counting three between the first and second shots. If I fire a second time, call all hands and come ashore."

"Well, Master Charley, I wouldn't venture it for all on the face of the earth; but we must do something, and the Lord be between ye and harm. See, now,"[Pg 32] he added, in a lower tone, "you're a heretic, I know, the Virgin pardon ye; but I'll say a Pater and two Aves, and if you never come back—"

"There, there, Hughie, old fellow, don't go mad with your foolish fears. Pray for yourself and us, if you please, for it is a terrible night, and we may well stand in need of prayer; but do your duty like a man. Stand in your place until I summon you, and then come, if a score of ghosts stand in the way."

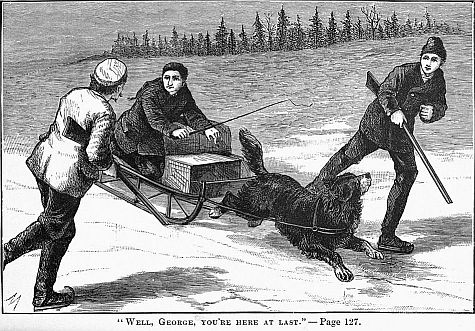

The next second Hughie stood alone, watching the tremulous radiance of the mysterious beacon, which La Salle rapidly approached, not without fear, it may be, but with a settled determination superior to the weakness which he felt, for the danger, exposure, and settled fears of his companion had almost transmitted their contagion to his own mind. As he drew nearer, however, the apparition resolved itself into a large reflecting lantern, suspended from a pole, in the hands of Captain Lund, who had headed a party to assist their friends to find the shore. The approach of our hero was not at first noticed, as he came up the bank a little to the rear of the party.

"I'm sure, gentlemen, I don't know what to advise; and yet we can't let them perish on the floes. We had better get the guns, and build a bonfire on the cape below; perhaps they may see it; but it wasn't for nothing that I saw those men the other night. Poor La Salle laughed at it, but if he was here now—"

"He is here, captain, thanks to your lantern, although Hughie, who is out on the ice yonder, shivering with fright and fear, vowed that it was the 'Packet Light,' and would scarcely let me come to see what it was. But this is no time to tell long stories; so I'll give the signal at once."

Creamer, fearfully watching the luminous spot, saw suddenly beside a jet of red flame, as the heavy gun roared the welcome signal that all was well; and scarcely a half moment later a still heavier report called the perplexed and wearied party to the shore, where they found themselves but about ten minutes' walk from the house.

Half an hour later, the bustling housewife summoned them to the spacious table, which was crowded with a profusion of smoking-hot viands, among which two huge geese, roasted to a turn, attracted the attention of all. Mr. Risk saw the inquiring looks of the others, and "rose to explain."

"Davies and I claim 'first blood,' as you see, having killed this pair, which, early in the morning, flew in from the westward, and were just lighting among our decoys, when we each dropped our bird. We came in early, seeing the storm brewing, and, being warned by Indian Peter, we escaped much inconvenience, if not danger, and were able to supply a brace of hot geese for supper. We shall expect a similar contribution to the general comfort from each party in rotation, in accordance with the ancient[Pg 34] usage of professors of our venerable and honorable mystery.

"Well, Lund," he continued, "the omen is not yet verified, although the party was nearly lost, and would have been altogether, if Hughie here had had his way, when he took your lantern for a ghost."

"Well, it does seem foolish, now that it is all over; but I have seen the 'Packet Light' myself too often not to believe in it, and so I was as simply frightened at the captain's lantern as the people of Loughrea were at Matthew Collins's ghost."

La Salle noted the look of annoyance which clouded the usually placid brow of their host, and hastened to allay the threatened storm. Rising from his seat, he begged the attention of the company.

"As we are to spend our evenings together for some weeks, it seems to me that it would not be a bad plan to require of each of our company, in rotation, some tale of wonder or personal adventure. Hughie has just referred to what must be an interesting and little known local legend of his mother isle. I move that we adjourn to the kitchen, and pass an hour in listening to it."

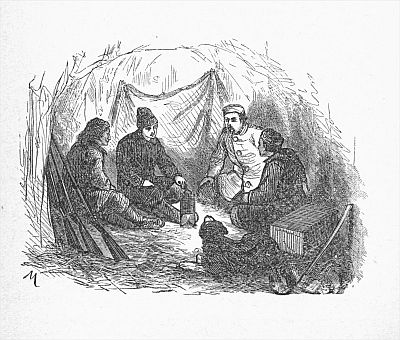

The proposition met with general favor, and rising, the company passed into the unplastered kitchen, through whose thin walls and poorly seasoned sashes came occasional little puffs of the furious wind, which whistled and howled like a demon without. The gunners seated themselves around the huge fireplace, in[Pg 35] which a pile of dried gnarled roots filled the room with light and warmth, and lighting pipe or cigar, as fancy dictated, gave a respectful attention to the promised story.

As will be gathered from the preceding conversation, Creamer spoke excellent English, but as is often the case when excited, he lapsed at times into a rich brogue. This he did to a considerable degree in relating what he was pleased to call the story of

"I was only a babe in arms when my father crossed the ocean to settle down on the Fane estate as one of the number of settlers, called for by the terms of the original grant. His father was a warm houlder in Errigle-Trough, and had my father been patient and industhrious, he would in a few years have rinted as good an hundhred acres as there was in that section. But the agent tould of land at a shillin' an acre, with wood in plenty, and trees that grew sugar, and game and fish for every one, and my father thought that he was provided for for life, when, with his lease in his pocket and a free passage, he stepped on board the ould ship that bore us to this little island.

"He wasn't far wrong, for he died when I was fifteen, worn out with clearin' woodland, and working all winter in the deep snow at lumbering, to keep us in bread and herrin'. He was a disappointed, worn-out old man at forty, and it was only when he told of[Pg 36] the good old times of his youth that I ever seen him smile at all, at all.

"Matthew Collins was a well-to-do farmer of the neighboring parish of Errigle-Keeran, and had a snug cottage and barn, with a good team of plough-horses, a cow, two goats, and a pig, beside poulthry enough to keep him in egg-milk, and even an occasional fowl or two on a birthday, or holy feast. He married Katty Bane, one of the prettiest girls and greatest coquettes in the whole parish. She, however, made him a good wife and careful manager, until the events of my sthory.

"One day, late in the fall, Matthew harnessed his horses in a hay-riggin', and drove off to the bog, five miles away, to haul in his winter's firin'. He wrought all day, getting the dried turfs into a pile, and had just half loaded his team, when a stranger, decently dressed, came up to him, and asked if his name was Matthew Collins.

"'That, indeed, is the name that's on me,' said Matthew; 'and what might you be wantin' of me?'

"'I've sorrowful news for you, Mat,' said the stranger. 'Your sister Rose, that married my poor cousin Tim Mulloy, beyant the mountains, is dead, and I'm sint to bid ye to the berryin' to-morrow.'

"For a few moments Matthew gave way to a natural feeling of grief at the loss of his sister; but he soon bethought himself that he was five miles from home, and that a circuitous road of at least twenty miles lay[Pg 37] between his house and the parish of his sister's husband.

"'I can never do it, that's certain,' said he to the stranger. 'It's five miles home, and there's changin' my clothes, and a twenty-mile drive over a road that it's timptin' Providence to attimpt in the dark.'

"'It's a great bother, intirely," said the stranger, reflectively. 'Musha! I have it. Take my clothes, and take the short cut across the Devil's Nose. In three hours you'll be at the wake, and I'll dhrive the team home and tell the good woman, and be round with a saddle-horse before mornin'.'

"'Faith it's yourself that's the dacent thing, any how; and I'm sorry that I can't be at home to thrate you with a bottle of the rale poteen. Never mind; tell Nancy it's in the thatch above the dure; and you're welcome to it all the same as if I were there myself.'

"'We won't part without a glass, any how,' said the stranger, laughingly. 'I've a pint bottle of the rale stuff, and some boiled eggs, and we'll soon have a couple of the shells emptied, in the shake of a lamb's tail, and thin we'll change clothes and dhrink to your safe journey.'

"Accordingly the two exchanged clothes, and sat for half an hour, while the stranger described the last illness of the deceased, and the respect shown her memory by the people of her parish.

"'Divil a whole head will be left in the parish, if they dhrink all the whiskey; and there's stacks of[Pg 38] pipes, and lashin's of tobacky, with tay and cakes, and the house in a blaze with mould candles. Is the road azy to find?' continued he. 'For I'm goin', mylone, where I never was afore.'

"'It's as plain as a pikestaff to the very door. Only take tent of the bridge at the slough, two miles beyant; for there's a broken balk that may upset ye.'

"'I'll warrant I'll look out for that. Have one more noggin. Here's a safe journey and a dacint berrin' to us both.'

"With this rather Irish toast, the two separated, Matthew seeing the stranger safe off the moss, and then commencing his short but fatiguing journey over the narrow mountain path which lay between him and his destination.

"Long before sunset, the careful Katty had had the delph teapot simmering among the hot peat ashes; and the well-browned bacon and mealy potatoes, carefully covered to retain the heat, only awaited the return of 'the master' from the distant bog. They had no children; but Andy, Katty's brother (a gossoon of thirteen), eyed the simple supper anxiously, going from time to time to the door to see if he could see the well-known gray horses coming by the old buckthorn, where the little lane joined the main road.

"The sunset, the night, came on, and Katty became hungry and out of temper.

"'Andy, alannah,' said she, 'run to the hill beyant, and try can you see aught of the masther; for I'm[Pg 39] tired wid the day's spinnin', and hungry, and wake.'

"The boy went, but returned, saying that no team was in sight.

"'Thin, Andy, jewel, we'll have our supper anyhow; for the tay'll be black wid thrawin', and the bacon and praties spilt intirely.'

"Accordingly the two sat down and finished their evening meal, expecting every moment to hear the cheery voice of Matthew as he urged his garrons with their heavy load up the steep lane beside the cottage.

"About nine o'clock, the wife became alarmed, and with Andy went to a neighbor's. Tim O'Connell, the village blacksmith, had just fallen asleep after a hard day's work, and woke in no very amiable frame of mind as Katty rapped at the door.

"'Who's there at all at this time of night?' said he, gruffly.

"'Only meself, Katty Collins, and Andy,' said Katty, rather dolorously, for she was now thoroughly alarmed.

"'Alice, colleen, up and unbar the dure. Come in, neighbor, and tell us what is the matther at all.'

"'O, Tim! Matthew's been gone all day to the bog, and isn't home yet. Could ye go wid the lad down the road, and see if anything has happened to himself or the bastes, the craters?'

"It was not like Tim O'Connell to refuse, and, calling[Pg 40] his assistant in the forge, young Larry Callaghan, he lighted a tallow candle, which he placed in a battered tin lantern, and hastened out on his neighborly errand, while Katty was easily persuaded by Mrs. O'Connell to 'stay by the fire' until the men returned.

"The party saw nothing of the team or its owner until the dangerous road led into a narrow but deep ravine, at whose bottom an ill-made causeway led across a dangerous slough.

"'Holy Virgin, boys, but he's been upset! There's the cart across the road, and one of the bastes in the wather; but where's the masther at all? Come on, b'ys; we'll thry and save the garrons any way.'

"They found the cart upset as described, and one of the horses exhausted with struggling under the pole. The other, saved only from drowning by the fact that its collar had held its head against the bank, had evidently kicked and splashed until the water was thick with the black muck stirred up from the bottom.

"It was only the work of a few moments to free the horse in the road, and then the three proceeded to unloose the other, and draw him to a less steep part of the embankment, where, making a sudden effort, with a mighty plunge, he gained the road, and stood trembling and shaking beside his companion.

"'Well done, our side,' said Tim, exultingly. 'Now for the masther. They've run away I doubt, and he's.—What's the matter with you, Andy, at all?[Pg 41] What do you see? Mother of Heaven! it's himself, sure enough!'

"Tossed up from the shallows by the convulsive plunge of the steed, whose heavy hoofs, in his first mad struggles, had beaten the head out of all shape of humanity, in the narrow lane of light cast through the door of the open lantern, lay the dead farmer, with his worn frieze coat torn and blackened, and his black hair knotted with pond weeds, and clotted with gore.

"It was scarce an hour later that the emptied cart, slowly drawn by its exhausted span, bore to the little cottage a dead body, amid the wails of scores of the simple peasants, and the hysterical and passionate grief of the bereaved wife. It was with the greatest difficulty that she was induced to refrain from looking at the dead body; although so terribly was it mangled that the coroner's jury performed their duties with the greatest reluctance, and the obsequies were ordered for the very next day.

"The body was accordingly placed in a coffin, above which deals, supported on trestles, and covered by white sheets, bore candles, plates of cut tobacco, pipes, and whiskey. Although but little of the night remained after the coroner had performed his duties, yet so quickly did the news of the accident spread that hundreds of the neighbors came in before morning 'to the wake of poor Matthew! God rest his sowl.'[Pg 42]

"The following evening, an unusually large procession followed the remains to their last resting-place. Nothing could have been more heart-broken than the bearing of the widow. Tears, sobs, and cries proclaimed her anguish incessantly, notwithstanding the attempts of friends to assuage her sorrow.

"As they drew near the graveyard, one Lanty Casey, an old flame of Katty's, tried to comfort her in his rough way.

"'Katty, avourneen, don't cry so, avillish. There's may be happiness for you yet, and there's them left that will love ye as well as him that's gone—if they'd be let.'

"Lanty was a noted lad at fair and pattern, but he got a box on the ear that made his head ring until the body was safely deposited in the grave.

"'Who are ye that talks love to a broken-hearted woman at the very grave? O, Matthew, Matthew, that I should live to see this day! Ochone, ochone! are you dead? are you dead?'

"On her way home to her solitary hearth, Katty saw ahead of her the hapless Lanty, and hastened to overtake him.

"'Lanty, avick," said she, sweetly, 'what were you saying there beyant, a while agone?'

"'What I'm not likely to say again. I'm not fond of such ansthers as ye gev me; an' if ye don't know when you're well off—'

"'There, there, Lanty, dear; I'm sorry for that[Pg 43] same, but what wud the people say, an' my husband not berrid? But I mustn't be seen talkin' more wid you. I'll be alone to-night when the gossoon is asleep, and ye can dhrap in, and tell me what ye like, av ye plaze.'

"At about ten o'clock that night, the Rev. Patrick Mulcahy, while talking over the funeral, and the sad events which had led to it, was asked for by the young lad, Katty's brother.

"'Well, Andy, lad, what's wanting now? Is your sister feeling better, avick?'

"'Yes, sir; and she sint me, your riverence, to see wud ye come down and marry her to Lanty Casey the night.'

"'Are your wits gone ashaughran, ye gomeral? Or is Katty run mad altogether?'

"'It's just as I say, your riverence; and she says she'll pay you a pound English for that same.'

"'And I say that if I go down there to-night, that I'll take my whip with me to the shameless hussy. The Jezabel, and she nearly dyin' with grief this evening.'

"'An' you won't marry them, sir?'

"A staggering box on the ear with a heavy slipper flung from across the room sent the unfortunate messenger whimpering out of the door; while the priest, honest man, stormed up and down the room until the housekeeper entered with a waiter, on which were[Pg 44] arrayed a decanter, some tumblers, a lemon, and a large tumbler full of loaf sugar.

"'Come, Peter,' said he, more calmly, 'reach the kettle from the hob, and we'll let the jade go. Perhaps she's out of her head, poor thing! and will forget all about what she says to-night by to-morrow morning. What are you grinning at there?'

"'Do you remimber the coult ye won from me whin I bet that ye couldn't light your pipe wid the sun?'

"'Yis, Pether. Ah, I had ye thin, sharp as you count yourself!'

"'Well, now, I'll bet the very moral of him against himself that Katty'll send up again—if she don't come herself.'

"'Done! for twice as much if you will. She doesn't dare—'

"'Good evening, your riverence,' said a woman's voice. And in the doorway stood Lanty Casey and Katty Collins.

"'We've come up, your riverence, to see if you'd plaze to marry us this night. They tould us you wor angry, sur, and, indade, I don't blame you; for you don't know all. The man who lies dead beyant was able to give me a home, and to keep a roof over the heads of my poor father and mother, and I gave up Lanty here for him. Now, sir, if you'll marry us, I'll give you the pig down below—and a finer's not in the parish; and if not—'

"The speaker paused, and, touching the arm of her[Pg 45] companion, who evidently feared to speak, retreated into the kitchen to await the decision of Father Patrick, who was almost bursting with chagrin at the loss of his wager, and anger at the boldness of his parishioner.

"Peter laughed, silently enjoying his brother's discomfiture, and then suddenly broke out,—

"'Now, what's the use, sir, of spitin' yourself? You've lost the coult, and the woman is bound to have her way. Sure, an' if you don't tie the knot, all they're to do is to sind over to Father Cahill—'

"'The hedge priest—is it? No, I'll marry them. Let them come in, Mrs. Hartigan, but no blessin' can come on such a rite as this.'

"Without a word of congratulation, the priest performed the service of his church, and in silence the pair proceeded to the cottage of the bride, where they fastened the doors and windows securely, and retired. The rising moon lighted up the surrounding scenery, and the priest and his brother sat later than usual over their 'night-caps' of hot Irish whiskey.

"'Peter,' said Father Mulcahy, 'sind young Costigan down for the pig. Perhaps to-morrow Katty will rue her bargain, and we won't get the crathur.'

"Costigan (a tight little lad of fourteen), roused from the settle-bed by the kitchen fire, soon procured a short cord and a whip, and set off on his rather untimely errand.

"A few moments before, a man dressed in holyday[Pg 46] garb tried the doors and windows of the cottage, and, finding them securely fastened, murmured,—

"''Tis frighted she is, an' I away, an' tired, too, wid spinnin', I'll be bound. Well, I'll not rise her now. There's clane sthraw in the barn, an' I'll slape there till mornin'.'

"The tired traveller had hardly laid himself down, with his head on a sheaf of oats, when he saw a youth enter the barn, and, deliberately taking a cord from his pocket, proceed to affix it to one of the hind legs of his much-prized pig, which resented the insult with a tremendous squealing.

"Matthew rose quietly, and lowered himself to the floor, catching a bridle rein, and getting between the trespasser and the wall.

"'I don't know what thievish crew claims ye, but I'll lay they'll see the marks of my hand-write under your shirt to-morrow,' said Matthew, savagely; but to his surprise the lad gave a single shriek, and sank down as if in a fit. A dash of water from the stable bucket recovered him somewhat, although his mind seemed to wander.

"'Holy angels be about us!—an' him dead and berrid—his very self—come back again!' And broken sentences of similar import were hurriedly murmured with closed eyes, as if to shut out some hideous sight; and the angry farmer was disarmed completely by the evident terror of the boy, who at last rose, fearfully opened his eyes, and looked around.[Pg 47]

"'Yes, ye little thafe of the world, I've come in time—'

"With a meaningless yell, or rather shriek of terror, the boy rushed out of the door, fell on the frosty roadway, tearing his clothes and cutting through the skin of both knees; and heeding nothing but the terror behind, sprang again to his feet, and rushed down the lane and along the moonlit road, until, panting, bleeding, and breathless, he rushed into the priest's dining-room.

"'O, yer riverince, he's come back!' was all that the boy could find breath to say for a moment; and Peter, who was rather irascible, took up the discourse at once.

"'It's yourself that's come back in a fine plight, you graceless, rioting, fighting, thaving young scullion. Whose cottage have ye been skylarkin' round now? And where's the pig ye was sint for, at all, at all?'

"'Peace, Pether, and let me discoorse him. Don't ye know that when I sent ye for the dues of the church, ye was engaged in its sarvice,—in holy ordhers, as it were? And how comes it, then, that you come back without the pig, and looking as frighted as if Matthew Collins himself had come back?'

"'And so he has masther, dear,' said the poor boy. 'O, wirra, wirra, but afther this night I'll never be out mylone again. I shall always think that I see him forninst me, as I met him beyant, the night.'[Pg 48]

"'Met Matthew Collins? The gossoon's crazy,' said the priest.

"'The young devil is lying, more likely. The dead don't come back to frighten honest folk, who want only their own,' said Peter, scornfully.

"'Now, Costigan, go back at wanst, and fetch the pig,' said Father Mulcahy, firmly, but kindly. 'Ye'll be ready enough to ate him this winther.'

"'O, masther, don't send me again! Ate that pig? An' if the pope himself said grace, I'd sooner starve than ate a collop of the crater. Why, either his sperit, or the devil in his shape, kapes watch over it; and all the money in Dublin wouldn't timpt me there agin after dark.'

"'Well, sir,' said Peter, savagely, 'the boy's frikened at somethin', that's certin'; and we shan't get the crather up here the night at all, unless it's done soon. It's only a stip just, and I'll go and get the pig, and find out what frighted the lad—a loose horse or cow, I'll be bound.'

"Accordingly, Peter set off on his errand, accompanied by Costigan, who went only on condition that he should not enter the barn, and only consented to go at all under threat of a tremendous thrashing if he refused.

"Scarcely an hour, therefore, had elapsed before Matthew was again awakened from sleep by the intrusion of a second midnight visitor.[Pg 49]

"'Where is the baste, any way?' asked the man, in gruff, angry tones.

"'He's right at the ind of the haggard, in the right hand corner,' tremulously answered a boyish voice from the distance of a few rods.

"'Faith, but the villains is intent on my pig, any how,' muttered the perplexed but angry Matthew, as he saw the struggles of his favorite when the robber attempted to secure a cord to her hind leg, which he seemed to find a difficult task.

"'The curse of Crom'll upon ye for an unaisy brute, any how, Ned! Ned Costigan, I say, come, ye little divil, and help me tie the knot, ye frikened omadhaun. There's nothing here to be afraid of, barrin' the gray horses an' the ould cow. Come, I say.—The Vargin and St. Pather presarve me! Are ye come back?'

"'Yes, I've come back, and ye'll go back to whoever sint ye, with my mark on yer shoulthers,' said Matthew, grimly, as, suiting the action to the word, he drew a stout stick from his sleeping-place, and brought it down with emphasis upon the head and shoulders of the priest's brother, who, though ordinarily considered 'as good a man' as there was in the parish, could scarcely persuade himself that he was not the victim of a terrible dream. Although he mechanically grappled and strove with his fearful antagonist, he felt the fierce breath of a demon, as his breast pressed against that of the dead, and the fierce eyes of a fiend, or an avenging ghost, glared[Pg 50] into his, as they fought and wrestled, now in the dark shadows, and now in the narrow lane of moonlight, which peered through the open door. It was no wonder that even the instinct of self-preservation failed to nerve him to meet such a foe, and that Matthew found it a surprisingly easy matter to give him a terrible beating.

"Fifteen minutes later, Peter, wan and covered with cuts and bruises, entered the priest's house, and swooned on the threshold. It was nearly daylight before he recovered himself sufficiently to corroborate the story of the lad, that the ghost of Matthew Collins jealously watched over his favorite pig.

"'An' why didn't he watch his wife too, Peter?' asked the priest, archly.

"'Faix! an' I dunno. But the same man set great store by that same baste—bad scran to her! I wish you had been wid us to discoorse the shpirit, and sind him back to his place.'

"'Faith, and only that it's daylight now, an' near time for matins, I'd just step over, and show ye the powers that are delegated to the clargy, avick. I'd like to see if Matthew Collins would dare to face me afther I've buried him dacently.'

"'An' married his wife again,' said Peter, with a feeble attempt at pleasantry.

"'I've doubts if I did wisely there, Peter. Sure and if the ungratefulness of those they love is enough to keep the dead from resting quietly, Matthew Collins[Pg 51] should be one of the first to come back and haunt his dishonored homestead.'

"'But if all the dead min that lave wifes aisily consoled for their loss, were to come back, there'd be plinty of haunted houses,' said Peter, pithily.

"'Well, we'll watch there the night, and try to find out the mysthery,' said the priest. 'But I'm off to matins. Be sure and see that Mrs. Hartigan has the breakfast ready when I return.'

"The bell calling the peasantry to their morning service awoke Matthew, who hastened to his cottage, which he found as closely barred and bolted as the night before.

"'She's gone to chapel long before this. Well, I'll have a wash at the spring, and away to church.' Saying which, he carefully picked the straw from his coat, cleaned his dusty shoes with a wisp of dry grass, and after a thorough washing of face and hands, he took up the worn felt hat of the stranger, and set off down the lane.

"As he got nearly to the main road, a group of neighbors passed along; but instead of answering his cheerful greeting, they crossed themselves, and hastened on with longer strides, turning from time to time, and looking at him in a most puzzling manner.

"'Sure, the folks are mad,' muttered poor Matthew, 'or else 'tis late we are—that must be it. Well, we can run, any way.' And suiting the action to the word, he began to run after his neighbors, who, terri[Pg 52]bly frightened, strove with all their might to preserve undiminished the distance between them.

"'Faix, half the people is late—or is it a fire is ragin'? Well, I dunno, but I'll be on hand any how.' And Matthew, taking a long breath, pressed on after the flying crowd, which grew larger each moment, as group after group of staid and devout worshipers recognized the features of their dead neighbor, and joined the panting crowd, which, crossing and blessing themselves, and shrieking and praying with terror, sought the protection of the church, and having, as they deemed, found a refuge from the apparition, sank exhausted into their seats, to thank God for a place of safety.

"But they had reckoned without their host, for the next moment the dead man strode through the arched door, and deliberately glided towards his accustomed seat. In speechless horror the people, with one accord, arose and rushed to the altar for protection, while many rushed out through the rear entrances, to carry the terrible news far and wide.

"Pale, but resolute, attended by two trembling altar boys with bell and censer, Father Mulcahy advanced in front of the astonished cause of this unwonted disturbance.

"'In the name of the Blessed Thrinity, I command you to retire from this blissid an' sacred church to the place from whence you came.'[Pg 53]

"'An' why wud I go back, your riverince? Shure, the body's buried, an' I've no call there now.'

"'Why, then, can you find no rest in the grave?'

"This last question 'broke the camel's back.'

"'H—— to my—There, the Lord forgive me for cursin', and in this blessed an' howly place. But are all the people mad—prastes and clarks, payrents and childher? Or am I losin' my sinses, or enchanted by the fairies?'

"'Matthew,' said the priest, solemnly, 'are you alive an' well?'

"'Yis, your riverence, if I know meself I am.'

"'Will you go to the font an' thrink a taste of the holy wather?'

"'Yes, your riverince, an it's plasin' to ye.'

"It was with much doubt that Father Mulcahy awaited the result of his test; but Matthew drank about a pint of the consecrated water, and a short conversation made all plain to the priest, and to poor Matthew, to whom the various events were far from being a matter of mirth.

"Accompanied by the priest, he went home, to the unutterable horror of the newly-married pair, which was little lessened when they found that their unwelcome visitor was not from another world.

"'I am dead to you, Katty,' said he, with a gentle sadness, so different from the burst of passion which the priest had feared, that he knew that his heart was broken. 'All the happiness I had was in your love,[Pg 54] and that was false. Go with your new love where I may see you no more.'

"Matthew died years after, a soured and misanthropic man; but few legends are better known in his native district than the story of Matthew Collins's ghost."

As the story ended, Risk thanked the narrator in behalf of the auditory, adding, "The storm will probably change to a thaw before morning, and if it does we must be on hand bright and early, for it will bring the main body of 'the first flight.'"

As the company rose to retire, Ben approached La Salle. "Will you tell me why you made us leave decoys at every hundred yards?"

"To help us find the way back, should we fail to reach the shore. We could have lived out a night like this in my ice-boat, but we should long since have been sleeping our last sleep beneath the snow-wreaths, had we lost our way upon the floes."

At daybreak La Salle awoke, but turned again to his pillow, as he noted the snow-flakes form in tiny drifts against the lower window panes; and it was nine o'clock before the tired sportsmen completed their hasty toilet, and seated themselves around the breakfast table.

he snow at nine o'clock had ceased to fall, but had given place to a thick hail, which rattled merrily on roof and window pane, but soon became softer, and mingled with rain as the wind veered more to the east and south.

"We are in for a heavy thaw," said the elder Davies, "and to-morrow we shall have good sport. It is hardly worth while to get wet to the skin, however, for what few birds we shall get to-day."

"Charley," said the younger Davies, "let us go down to the bar and look up our decoys, for if we have a heavy thaw they may all be washed away and lost."

Putting on their water-proof coats, boots, and sou'westers, the young men took their guns and started for the eastern end of the island. The drifts were very heavy along the fences and under the steep banks which overhung the eastern and northern shores of the island, and huge hummocks, white, smooth, and unbroken, showed where the snow had[Pg 56] entombed huge bergs and fantastic pinnacles. Facing the storm with some difficulty, they got out as far as the ice-boat of La Salle, which they found completely covered to the depth of two or three feet.

"We should have been smothered if we had taken refuge there last night," said Ben, as he proceeded to search for the buried decoys.

"I think not; for men can breathe below a great depth of snow, and I have heard of sheep being taken alive from a heavy drift after an entombment of twenty or thirty days."

The decoys were soon gathered, and they proceeded to the farther stand, where they took the same precaution against the expected flooding of the floes, piling the decoys into the box until a pyramid of clumsy wooden birds rose several feet above the level of the ice, which was fast becoming soft, and covered with dirty pools of snow water and nasty "sludge."

"Here is the track of a fox," cried Davies, "and here is where he has killed a goose this morning;" and La Salle, on hastening to the spot, found a fresh trail leading from the main land, and beside the last decoy a slight depression around which loose feathers and clots of blood told in unmistakable terms that a single bird, and not improbably a wounded one, had alighted amid the decoys, and trusting to the vigilance of his supposed companions, had fallen an easy prey to his soft-footed assailant.[Pg 57]

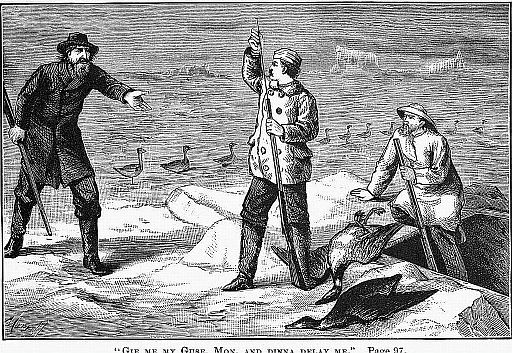

"Here comes one-armed Peter on his track," said La Salle; and in a few moments a tall, finely-built, middle-aged Micmac came noiselessly up, bearing in his only remaining hand, not a gun, but an axe.

"Where's your gun, Peter?" said Ben, carelessly; "you don't expect to kill a fox with an axe—do you?"

The Indian's brow contracted a little, and instantly relaxed, as he answered, "That not fox track at all; that Indian dog, I guess. Martin Mitchell have dog; lun alound like that. No good dog that. Sposum mine, kill um."

"Yes, Peter, I've no doubt you'd like to kill that dog very well. See, he finds his own living for himself. He killed a goose here last night, I see. I s'pose your Indian dogs will eat geese raw, but mine never would. He sat down here a moment after he had killed his bird, and left the marks of a very bushy tail. Here's some of the hair, too. By thunder! 'tis the hair of a black fox."

The Indian laughed silently, with no little admiration of the close observation of the other visible in his countenance. "Yes, that black fox. I see his track last night; trail him two tree mile dis morning. No use try to fool you; fool other white man over back there; you know trail well as Indian. No use carry gun, I think; fox in wet weather get in hollow tlee, or under big loot. I cut down tlee and knock on head with axe. But if fox on island, I lose him; no tlee there at all big enough."[Pg 58]

"Well, Peter, his trail is straight for the end of the point, and he must be in the swamp at the other end of the island. We'll go with you and surround the swamp while you enter it. If you fail to tree him, we'll shoot him when he breaks cover, and we'll divide equally whether one or two help to kill him." And La Salle, resting the butt of his heavy gun on his boot, drew his load of loose shot, and substituted an Eley's cartridge, containing two ounces of large "swan-drops."

A cloud settled upon the smiling face of the Indian, and he broke forth vehemently, "I no want you to help me. I need all that money; you got plenty. I been sick, had sick boy, sick old woman,—bery sick. I see that fox two time. No got gun; borrow money on him to pay doctor, and get blead. I borrow gun one day; sit all day, no get nothing; go home, nothing to eat. Next day, man use his own gun, kill plenty. I know fox in wet day find hollow tlee; no like to wet his tail. I say to-day I kill him, get good gun, get cloes, get plenty blead and tee. I know I kill that fox."

"Well, Peter, we won't trouble you. We'll go to see you kill him, and watch out to see that he don't get clear," said Davies; and the Indian, rather hesitatingly, assented.

There was little woodcraft in following the "sign," for the tracks were deeply impressed in the soft snow, and the heavy body and long neck of his prey had left[Pg 59] numerous impressions where the fox had rested for a moment. In the course of half an hour the party had gained the shore, and, passing through several fields, found themselves in a heavy growth of beech and maple.

The fox, however, had not halted here, but emerging into a small meadow, had crossed into a close copse of young firs and elders, in whose midst a huge stump, whitened and splintered, rose some twenty-five feet into the air.

Peter groaned audibly. "That old fox mean as debbil. Know that place no good. No hollow tlee, only brush and thick branch. Fox get under loot, and eat, watch twenty way at once: well, I try, any way."

Ben and La Salle hastily passed around the woods surrounding the glade, until they reached the opposite side of the motte to that which Peter was now entering. Noticing that only a narrow space of open ground intervened at one point, Davies crept noiselessly down to the very edge of the underbrush, about sixty yards from La Salle.

He had scarcely drawn himself up from his crouching position, when a magnificent black fox crossed the opening almost at his very feet, followed by the light axe of the Indian, which, thrown with astonishing force and precision, passed just above the animal, and was buried almost to the helve in a small tree not a yard from Davies's head.

Flurried out of his usual good judgment, Ben drew[Pg 60] both triggers, with uncertain aim, and the fox, swerving a little, passed him like a shot. La Salle, springing forward through the narrow belt of woods, saw the frightened animal a score of rods off, making across the fields for the Western Bar. A fence bounded the field some six score yards away, under which the fox must pass, and whose top rail, scarce three feet above the level, marked the necessary elevation to allow for the "drop" of the tiny missiles used. La Salle felt that all depended on his aim, and that his nerves were at the utmost tension of excited interest; but he forced himself to act with deliberate promptitude at a moment when the most feverish haste would have seemed interminable dallying. Steadily the ponderous tube was levelled in line of the fleeing beast, until the beaded sight rested on the top rail above him. An instant the heavy weapon seemed absolutely without motion; then the report crashed through the forest, and the snow-crust was dashed into impalpable powder by a hundred riddling pellets.

The shot was fired just as the fox sprang up the slight embankment on which, as is usual, the line of fence was placed. For an instant he seemed to falter, then leaped the top rail, and disappeared beyond the enclosure.

Peter and Davies had seen the shot, and with La Salle rushed forward to note its effect, although neither hoped for more than a wound whose bleeding would ultimately disable him, when patient tracking[Pg 61] would secure his much-prized fur. As they ran to the fence they noted the deeply-cut scores in the icy crust which marked the first dropping shot, and Peter became loud in his praises of the weapon.

"I never see gun like that; at hundred yards you kill him, sure; but no gun ever kill so far as you fire. See there, shot strike dis stump. Hah! there spot of blood on bank. Damn! here fox dead, sure enough."

"Hurrah! the Baby forever for a long shot. Charley, old boy, shake hands on it. Peter, don't you wish you hadn't been so sure of killing him without our help?"

The thoughtless triumph of the young Englishman recalled the memory of his obstinate refusal to accept the proffered aid of the sportsmen to the mind of the poor Indian. Such a look of utter disappointment took the place of his joy at the successful shot, that La Salle could scarcely contain his sympathy.

"So it is always. White man win, Indian lose; white man get food, Indian starve; white man live, Indian die. Once, all this Indian land. No white people were here, and many Indians hunt and find enough. Now, the Indian must buy the wood which he makes into baskets. He cannot spear a salmon in the rivers. The woods are cut down, and the many ships and guns frighten off the game."

He looked a moment at the dead fox, smoothed its glossy fur with a hand that trembled with suppressed[Pg 62] emotion, and then, with a curt "good evening," turned to go.

"I wish, Peter, you would come down to the house and skin this beast for me," said La Salle. "If you will do so carefully, and stretch it for drying in good style, I'll give you a pair of boots."

Without a word the Indian seized the dead animal and strode ahead of them, like one who seeks in bodily fatigue a refuge from anguish of spirit.

"What will you give for such a skin, Davies?" asked La Salle.

"I will give you one hundred and fifty dollars for that one. It is the largest, finest, and blackest that I ever saw."

"You have another gun like your own in your store at C.—have you not?"

"Yes, exactly like my own. I can only tell them apart by this curl in the wood of the stock."

"What is she worth?"

"I will sell her to you for fifteen pounds."

"That would be fifty dollars. Well, Ben, I'll tell you what, we must give Peter one half of the fox. I should never forgive myself if we didn't. I know he has been sick all summer, and his disappointment must be very hard to bear. Are you willing to give him half?"

"Do just as you please, Charley," said the warmhearted hunter. "I don't claim any share, for we are all on our own hook, unless by special agreement; but[Pg 63] I shall be very glad if you are kind enough to share with him, poor fellow!"

"Well, Ben, you are to take the fox at your own price, giving Peter an order on your partner for the gun, and credit to the amount of twenty-five dollars more. The other seventy-five we divide. You have only to give me credit for my moiety, as I owe you nearly that amount."

"I'm satisfied if you are; so let us hurry up, and see Peter prepare the skin, and send him home happy."

"The finest skin I ever saw," said Risk. "It's worth three hundred dollars in St. Petersburg, if it's worth a cent."

"Who killed him?" said the elder Davies. "If you did, Ben, I'd like to buy the skin."

"I bought it myself of La Salle for one hundred and fifty. He killed it, and sold it to me. I guess I can sell to good advantage."

In the mean time Peter had drawn his waghon, or curved Indian knife, from his belt, and, carefully commencing at the rear of the body, skinned the animal without forming another aperture, removing the mask, and ears attached, with great nicety. With equal dexterity he whittled a piece of pine board to the proper shape, and, turning the skin inside out, drew it tightly over the batten, fastening it in place with a few tacks. His task completed, he handed it to La[Pg 64] Salle, and rose to go. The latter restrained him, saying,—

"Hold, Peter; you must have your pay first. Here is a pair of rubber boots and some dry stockings. Put them on, and throw away those old moccasons, and take these few things to your wife."

"You very kind, brother," said Peter, simply, taking the small bundle of tea, sugar, bread, cake, and jellies which could be spared from their limited stock of "small stores."

"And, Peter," continued La Salle, "Ben and I have concluded to share with you in the matter of the fox. We have no wives yet, and therefore think about one half the price ought to go to you. This paper will get you that double-barrel of Ben's father to-morrow, if you feel like going over for it; and you will also be allowed to purchase twenty-five dollars' worth more of ammunition, food, and clothing."

The tears came into the poor fellow's eyes.

"Damn! I know you hite men. I know you heretic. I say I no hunt with you. I try cheat you on the trail, and you make Peter cly like squaw. I wish—I wish—you two, tlee, six fathom deep in river. I jump in for you if I die."

And, seizing the bundle and the precious order, he dashed the moisture from his eyes, and took the road homeward.