The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Death Shot, by Mayne Reid

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Death Shot

A Story Retold

Author: Mayne Reid

Release Date: October 21, 2007 [EBook #23140]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE DEATH SHOT ***

Produced by Nick Hodson of London, England

Captain Mayne Reid

"The Death Shot"

Preface.

Long time since this hand hath penned a preface. Now only to say, that this romance, as originally published, was written when the author was suffering severe affliction, both physically and mentally—the result of a gun-wound that brought him as near to death as Darke’s bullet did Clancy.

It may be asked, Why under such strain was the tale written at all? A good reason could be given; but this, private and personal, need not, and should not be intruded on the public. Suffice it to say, that, dissatisfied with the execution of the work, the author has remodelled—almost rewritten it.

It is the same story; but, as he hopes and believes, better told.

Great Malvern, September, 1874.

Prologue.

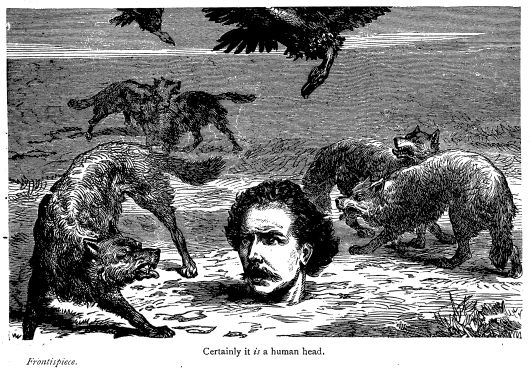

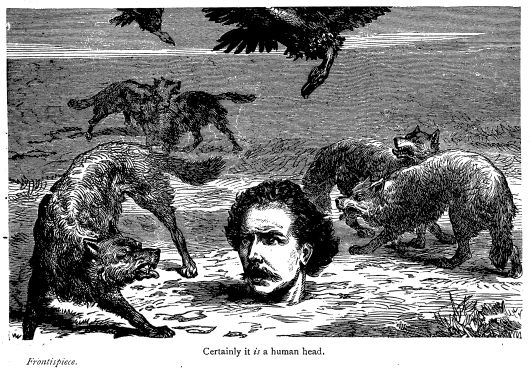

Plain, treeless, shrubless, smooth as a sleeping sea. Grass upon it; this so short, that the smallest quadruped could not cross over without being seen. Even the crawling reptile would not be concealed among its tufts.

Objects are upon it—sufficiently visible to be distinguished at some distance. They are of a character scarce deserving a glance from the passing traveller. He would deem it little worth while to turn his eyes towards a pack of prairie wolves, much less go in chase of them.

With vultures soaring above, he might be more disposed to hesitate, and reflect. The foul birds and filthy beasts seen consorting together, would be proof of prey—that some quarry had fallen upon the plain. Perhaps, a stricken stag, a prong-horn antelope, or a wild horse crippled by some mischance due to his headlong nature?

Believing it any of these, the traveller would reloosen his rein, and ride onward,—leaving the beasts and birds to their banquet.

There is no traveller passing over the prairie in question—no human being upon it. Nothing like life, save the coyotes grouped over the ground, and the buzzards swooping above.

They are not unseen by human eye. There is one sees—one who has reason to fear them.

Their eager excited movements tell them to be anticipating a repast; at the same time, that they have not yet commenced it.

Something appears in their midst. At intervals they approach it: the birds swoopingly from heaven, the beasts crouchingly along the earth. Both go close, almost to touching it; then suddenly withdraw, starting back as in affright!

Soon again to return; but only to be frayed as before. And so on, in a series of approaches, and recessions.

What can be the thing thus attracting, at the same time repelling them? Surely no common quarry, as the carcase of elk, antelope, or mustang? It seems not a thing that is dead. Nor yet looks it like anything alive. Seen from a distance it resembles a human head. Nearer, the resemblance is stronger. Close up, it becomes complete. Certainly, it is a human head—the head of a man!

Not much in this to cause surprise—a man’s head lying upon a Texan prairie! Nothing, whatever, if scalpless. It would only prove that some ill-starred individual—traveller, trapper, or hunter of wild horses—has been struck down by Comanches; afterwards beheaded, and scalped.

But this head—if head it be—is not scalped. It still carries its hair—a fine chevelure, waving and profuse. Nor is it lying upon the ground, as it naturally should, after being severed from the body, and abandoned. On the contrary, it stands erect, and square, as if still on the shoulders from which it has been separated; the neck underneath, the chin just touching the surface. With cheeks pallid, or blood spotted, and eyes closed or glassy, the attitude could not fail to cause surprise. And yet more to note, that there is neither pallor, nor stain on the cheeks; and the eyes are neither shut, nor glassed. On the contrary, they are glancing—glaring—rolling. By Heavens the head is alive!

No wonder the wolves start back in affright; no wonder the vultures, after stooping low, ply their wings in quick nervous stroke, and soar up again! The odd thing seems to puzzle both beasts and birds; baffles their instinct, and keeps them at bay.

Still know they, or seem to believe, ’tis flesh and blood. Sight and scent tell them so. By both they cannot be deceived.

And living flesh it must be? A Death’s head could neither flash its eyes, nor cause them to revolve in their sockets. Besides, the predatory creatures have other evidence of its being alive. At intervals they see opened a mouth, disclosing two rows of white teeth; from which come cries that, startling, send them afar.

These are only put forth, when they approach too threateningly near—evidently intended to drive them to a distance. They have done so for the greater part of a day.

Strange spectacle! The head of a man, without any body; with eyes in it that scintillate and see; a mouth that opens, and shows teeth; a throat from which issue sounds of human intonation; around this object of weird supernatural aspect, a group of wolves, and over it a flock of vultures!

Twilight approaching, spreads a purple tint over the prairie. But it brings no change in the attitude of assailed, or assailants. There is still light enough for the latter to perceive the flash of those fiery eyes, whose glances of menace master their voracious instincts, warning them back.

On a Texan prairie twilight is short. There are no mountains, or high hills intervening, no obliquity in the sun’s diurnal course, to lengthen out the day. When the golden orb sinks below the horizon, a brief crepusculous light succeeds; then darkness, sudden as though a curtain of crape were dropped over the earth.

Night descending causes some change in the tableau described. The buzzards, obedient to their customary habit—not nocturnal—take departure from the spot, and wing their way to their usual roosting place. Different do the coyotes. These stay. Night is the time best suited to their ravening instincts. The darkness may give them a better opportunity to assail that thing of spherical shape, which by shouts, and scowling glances, has so long kept them aloof.

To their discomfiture, the twilight is succeeded by a magnificent moon, whose silvery effulgence falling over the plain almost equals the light of day. They see the head still erect, the eyes angrily glancing; while in the nocturnal stillness that cry, proceeding from the parted lips, affrights them as ever.

And now, that night is on, more than ever does the tableau appear strange—more than ever unlike reality, and more nearly allied to the spectral. For, under the moonlight, shimmering through a film that has spread over the plain, the head seems magnified to the dimensions of the Sphinx; while the coyotes—mere jackals of terrier size—look large as Canadian stags!

In truth, a perplexing spectacle—full of wild, weird mystery.

Who can explain it?

Chapter One.

Two sorts of Slave-Owners.

In the old slave-owning times of the United States—happily now no more—there was much grievance to humanity; proud oppression upon the one side, with sad suffering on the other. It may be true, that the majority of the slave proprietors were humane men; that some of them were even philanthropic in their way, and inclined towards giving to the unholy institution a colour of patriarchism. This idea—delusive, as intended to delude—is old as slavery itself; at the same time, modern as Mormonism, where it has had its latest, and coarsest illustration.

Though it cannot be denied, that slavery in the States was, comparatively, of a mild type, neither can it be questioned, that among American masters occurred cases of lamentable harshness—even to inhumanity. There were slave-owners who were kind, and slave-owners who were cruel.

Not far from the town of Natchez, in the State of Mississippi, lived two planters, whose lives illustrated the extremes of these distinct moral types. Though their estates lay contiguous, their characters were as opposite, as could well be conceived in the scale of manhood and morality. Colonel Archibald Armstrong—a true Southerner of the old Virginian aristocracy, who had entered the Mississippi Valley before the Choctaw Indians evacuated it—was a model of the kind slave-master; while Ephraim Darke—a Massachusetts man, who had moved thither at a much later period—was as fair a specimen of the cruel. Coming from New England, of the purest stock of the Puritans—a people whose descendants have made much sacrifice in the cause of negro emancipation—this about Darke may seem strange. It is, notwithstanding, a common tale; one which no traveller through the Southern States can help hearing. For the Southerner will not fail to tell him, that the hardest task-master to the slave is either one, who has been himself a slave, or descended from the Pilgrim Fathers, whose feet first touched American soil by the side of Plymouth Rock!

Having a respect for many traits in the character of these same Pilgrim Fathers, I would fain think the accusation exaggerated—if not altogether untrue—and that Ephraim Darke was an exceptional individual.

To accuse him of inhumanity was no exaggeration whatever. Throughout the Mississippi valley there could be nothing more heartless than his treatment of the sable helots, whose luckless lot it was to have him for a master. Around his courts, and in his cotton-fields, the crack of the whip was heard habitually—its thong sharply felt by the victims of his caprice, or malice. The “cowhide” was constantly carried by himself, and his overseer. He had a son, too, who could wield it wickedly as either. None of the three ever went abroad without that pliant, painted, switch—a very emblem of devilish cruelty—in their hands; never returned home, without having used it in the castigation of some unfortunate “darkey,” whose evil star had caused him to stray across their track, while riding the rounds of the plantation.

A far different discipline was that of Colonel Armstrong; whose slaves seldom went to bed without a prayer poured forth, concluding with: “God bress de good massr;” while the poor whipped bondsmen of his neighbour, their backs oft smarting from the lash, nightly lay down, not always to sleep, but nearly always with curses on their lips—the name of the Devil coupled with that of Ephraim Darke.

The old story, of like cause followed by like result, must, alas! be chronicled in this case. The man of the Devil prospered, while he of God came to grief. Armstrong, open-hearted, free-handed, indulging in a too profuse hospitality, lived widely outside the income accruing from the culture of his cotton-fields, and in time became the debtor of Darke, who lived as widely within his.

Notwithstanding the proximity of their estates, there was but little intimacy, and less friendship, between the two. The Virginian—scion of an old Scotch family, who had been gentry in the colonial times—felt something akin to contempt for his New England neighbour, whose ancestors had been steerage passengers in the famed “Mayflower.” False pride, perhaps, but natural to a citizen of the Old Dominion—of late years brought low enough.

Still, not much of this influenced the conduct of Armstrong. For his dislike to Darke he had a better, and more honourable, reason—the bad behaviour of the latter. This, notorious throughout the community, made for the Massachusetts man many enemies; while in the noble mind of the Mississippian it produced positive aversion.

Under these circumstances, it may seem strange there should be any intercourse, or relationship, between the two men. But there was—that of debtor and creditor—a lien not always conferring friendship. Notwithstanding his dislike, the proud Southerner had not been above accepting a loan from the despised Northern, which the latter was but too eager to extend. The Massachusetts man had long coveted the Mississippian’s fine estate; not alone from its tempting contiguity, but also because it looked like a ripe pear that must soon fall from the tree. With secret satisfaction he had observed the wasteful extravagance of its owner; a satisfaction increased on discovering the latter’s impecuniosity. It became joy, almost openly exhibited, on the day when Colonel Armstrong came to him requesting a loan of twenty thousand dollars; which he consented to give, with an alacrity that would have appeared suspicious to any but a borrower.

If he gave the money in great glee, still greater was that with which he contemplated the mortgage deed taken in exchange. For he knew it to be the first entering of a wedge, that in due time would ensure him possession of the fee-simple. All the surer, from a condition in that particular deed: Foreclosure, without time. Pressure from other quarters had forced planter Armstrong to accept these terrible terms.

As, Darke, before locking it up in his drawer, glanced the document over, his eyes scintillating with the glare of greed triumphant, he said to himself, “This day’s work has doubled the area of my acres, and the number of my niggers. Armstrong’s land, his slaves, his houses,—everything he has, will soon be mine!”

Chapter Two.

A flat refusal.

Two years have elapsed since Ephraim Darke became the creditor of Archibald Armstrong. Apparently, no great change has taken place in the relationship between the two men, though in reality much.

The twenty thousand dollars’ loan has been long ago dissipated, and the borrower is once more in need.

It would be useless, idle, for him to seek a second mortgage in the same quarter; or in any other, since he can show no collateral. His property has been nearly all hypothecated in the deed to Darke; who perceives his long-cherished dream on the eve of becoming a reality. At any hour he may cause foreclosure, turn Colonel Armstrong out of his estate, and enter upon possession.

Why does he not take advantage of the power, with which the legal code of the United States, as that existing all over the world, provides him?

There is a reason for his not doing so, wide apart from any motive of mercy, or humanity. Or of friendship either, though something erroneously considered akin to it. Love hinders him from pouncing on the plantation of Archibald Armstrong, and appropriating it!

Not love in his own breast, long ago steeled against such a trifling affection. There only avarice has a home; cupidity keeping house, and looking carefully after the expenses.

But there is a spendthrift who has also a shelter in Ephraim Darke’s heart—one who does much to thwart his designs, oft-times defeating them. As already said, he has a son, by name Richard; better known throughout the settlement as “Dick”—abbreviations of nomenclature being almost universal in the South-Western States. An only son—only child as well—motherless too—she who bore him having been buried long before the Massachusetts man planted his roof-tree in the soil of Mississippi. A hopeful scion he, showing no improvement on the paternal stock. Rather the reverse; for the grasping avarice, supposed to be characteristic of the Yankee, is not improved by admixture with the reckless looseness alleged to be habitual in the Southerner.

Both these bad qualities have been developed in Dick Darke, each to its extreme. Never was New Englander more secretive and crafty; never Mississippian more loose, or licentious.

Mean in the matter of personal expenditure, he is at the same time of dissipated and disorderly habits; the associate of the poker-playing, and cock-fighting, fraternity of the neighbourhood; one of its wildest spirits, without any of those generous traits oft coupled with such a character.

As only son, he is heir-presumptive to all the father’s property—slaves and plantation lands; and, being thoroughly in his father’s confidence, he is aware of the probability of a proximate reversion to the slaves and plantation lands belonging to Colonel Armstrong.

But much as Dick Darke may like money, there is that he likes more, even to covetousness—Colonel Armstrong’s daughter. There are two of them—Helen and Jessie—both grown girls,—motherless too—for the colonel is himself a widower.

Jessie, the younger, is bright-haired, of blooming complexion, merry to madness; in spirit, the personification of a romping elf; in physique, a sort of Hebe. Helen, on the other hand, is dark as gipsy, or Jewess; stately as a queen, with the proud grandeur of Juno. Her features of regular classic type, form tall and magnificently moulded, amidst others she appears as a palm rising above the commoner trees of the forest. Ever since her coming out in society, she has been universally esteemed the beauty of the neighbourhood—as belle in the balls of Natchez. It is to her Richard Darke has extended his homage, and surrendered his heart.

He is in love with her, as much as his selfish nature will allow—perhaps the only unselfish passion ever felt by him.

His father sanctions, or at all events does not oppose it. For the wicked son holds a wonderful ascendancy over a parent, who has trained him to wickedness equalling his own.

With the power of creditor over debtor—a debt of which payment can be demanded at any moment, and not the slightest hope of the latter being able to pay it—the Darkes seem to have the vantage ground, and may dictate their own terms.

Helen Armstrong knows nought of the mortgage; no more, of herself being the cause which keeps it from foreclosure. Little does she dream, that her beauty is the sole shield imposed between her father and impending ruin. Possibly if she did, Richard Darke’s attentions to her would be received with less slighting indifference. For months he has been paying them, whenever, and wherever, an opportunity has offered—at balls, barbecues, and the like. Of late also at her father’s house; where the power spoken of gives him not only admission, but polite reception, and hospitable entertainment, at the hands of its owner; while the consciousness of possessing it hinders him from observing, how coldly his assiduities are met by her to whom they are so warmly addressed.

He wonders why, too. He knows that Helen Armstrong has many admirers. It could not be otherwise with one so splendidly beautiful, so gracefully gifted. But among them there is none for whom she has shown partiality.

He has, himself, conceived a suspicion, that a young man, by name Charles Clancy—son of a decayed Irish gentleman, living near—has found favour in her eyes. Still, it is only a suspicion; and Clancy has gone to Texas the year before—sent, so said, by his father, to look out for a new home. The latter has since died, leaving his widow sole occupant of an humble tenement, with a small holding of land—a roadside tract, on the edge of the Armstrong estate.

Rumour runs, that young Clancy is about coming back—indeed, every day expected.

That can’t matter. The proud planter, Armstrong, is not the man to permit of his daughter marrying a “poor white”—as Richard Darke scornfully styles his supposed rival—much less consent to the so bestowing of her hand. Therefore no danger need be dreaded from that quarter.

Whether there need, or not, the suitor of Helen Armstrong at length resolves on bringing the affair to an issue. His love for her has become a strong passion, the stronger for being checked—restrained by her cold, almost scornful behaviour. This may be but coquetry. He hopes, and has a fancy it is. Not without reason. For he is far from being ill-favoured; only in a sense moral, not physical. But this has not prevented him from making many conquests among backwood’s belles; even some city celebrities living in Natchez. All know he is rich; or will be, when his father fulfils the last conditions of his will—by dying.

So fortified, so flattered, Dick Darke cannot comprehend why Miss Armstrong has not at once surrendered to him. Is it because her haughty disposition hinders her from being too demonstrative? Does she really love him, without giving sign?

For months he has been cogitating in this uncertain way; and now determines upon knowing the truth.

One morning he mounts his horse; rides across the boundary line between the two plantations, and on to Colonel Armstrong’s house. Entering, he requests an interview with the colonel’s eldest daughter; obtains it; makes declaration of his love; asks her if she will have him for a husband; and in response receives a chilling negative.

As he rides back through the woods, the birds are trilling among the trees. It is their merry morning lay, but it gives him no gladness. There is still ringing in his ears that harsh monosyllable, “no.” The wild-wood songsters appear to echo it, as if mockingly; the blue jay, and red cardinal, seem scolding him for intrusion on their domain!

Having recrossed the boundary between the two plantations, he reins up and looks back. His brow is black with chagrin; his lips white with rancorous rage. It is suppressed no longer. Curses come hissing through his teeth, along with them the words,—

“In less than six weeks these woods will be mine, and hang me, if I don’t shoot every bird that has roost in them! Then, Miss Helen Armstrong, you’ll not feel in such conceit with yourself. It will be different when you haven’t a roof over your head”. So good-bye, sweetheart! Good-bye to you.

“Now, dad!” he continues, in fancy apostrophising his father, “you can take your own way, as you’ve been long wanting. Yes, my respected parent; you shall be free to foreclose your mortgage; put in execution; sheriff’s officers—anything you like.”

Angrily grinding his teeth, he plunges the spur into his horse’s ribs, and rides on—the short, but bitter, speech still echoing in his ears.

Chapter Three.

A Forest Post-Office.

From the harsh treatment of slaves sprang a result, little thought of by the inhuman master; though greatly detrimental to his interests. It caused them occasionally to abscond; so making it necessary to insert an advertisement in the county newspaper, offering a reward for the runaway. Thus cruelty proved expensive.

In planter Darke’s case, however, the cost was partially recouped by the cleverness of his son; who was a noted “nigger-catcher,” and kept dogs for the especial purpose. He had a natural penchant for this kind of chase; and, having little else to do, passed a good deal of his time scouring the country in pursuit of his father’s advertised runaways. Having caught them, he would claim the “bounty,” just as if they belonged to a stranger. Darke, père, paid it without grudge or grumbling—perhaps the only disbursement he ever made in such mood. It was like taking out of one pocket to put into the other. Besides, he was rather proud of his son’s acquitting himself so shrewdly.

Skirting the two plantations, with others in the same line of settlements, was a cypress swamp. It extended along the edge of the great river, covering an area of many square miles. Besides being a swamp, it was a network of creeksy bayous, and lagoons—often inundated, and only passable by means of skiff or canoe. In most places it was a slough of soft mud, where man might not tread, nor any kind of water-craft make way. Over it, at all times, hung the obscurity of twilight. The solar rays, however bright above, could not penetrate its close canopy of cypress tops, loaded with that strangest of parasitical plants—the tillandsia usneoides.

This tract of forest offered a safe place of concealment for runaway slaves; and, as such, was it noted throughout the neighbourhood. A “darkey” absconding from any of the contiguous plantations, was as sure to make for the marshy expanse, as would a chased rabbit to its warren.

Sombre and gloomy though it was, around its edge lay the favourite scouting-ground of Richard Darke. To him the cypress swamp was a precious preserve—as a coppice to the pheasant shooter, or a scrub-wood to the hunter of foxes. With the difference, that his game was human, and therefore the pursuit more exciting.

There were places in its interior to which he had never penetrated—large tracts unexplored, and where exploration could not be made without great difficulty. But for him to reach them was not necessary. The runaways who sought asylum in the swamp, could not always remain within its gloomy recesses. Food must be obtained beyond its border, or starvation be their fate. For this reason the fugitive required some mode of communicating with the outside world. And usually obtained it, by means of a confederate—some old friend, and fellow-slave, on one of the adjacent plantations—privy to the secret of his hiding-place. On this necessity the negro-catcher most depended; often finding the stalk—or “still-hunt,” in backwoods phraseology—more profitable than a pursuit with trained hounds.

About a month after his rejection by Miss Armstrong, Richard Darke is out upon a chase; as usual along the edge of the cypress swamp, rather should it be called a search: since he has found no traces of the human game that has tempted him forth. This is a fugitive negro—one of the best field-hands belonging to his father’s plantation—who has absented himself, and cannot be recalled.

For several weeks “Jupiter”—as the runaway is named—has been missing; and his description, with the reward attached, has appeared in the county newspaper. The planter’s son, having a suspicion that he is secreted somewhere in the swamp, has made several excursions thither, in the hope of lighting upon his tracks. But “Jupe” is an astute fellow, and has hitherto contrived to leave no sign, which can in any way contribute to his capture.

Dick Darke is returning home, after an unsuccessful day’s search, in anything but a cheerful mood. Though not so much from having failed in finding traces of the missing slave. That is only a matter of money; and, as he has plenty, the disappointment can be borne. The thought embittering his spirit relates to another matter. He thinks of his scorned suit, and blighted love prospects.

The chagrin caused him by Helen Armstrong’s refusal has terribly distressed, and driven him to more reckless courses. He drinks deeper than ever; while in his cups he has been silly enough to let his boon companions become acquainted with his reason for thus running riot, making not much secret, either, of the mean revenge he designs for her who has rejected him. She is to be punished through her father.

Colonel Armstrong’s indebtedness to Ephraim Darke has become known throughout the settlement—all about the mortgage. Taking into consideration the respective characters of the mortgagor and mortgagee, men shake their heads, and say that Darke will soon own the Armstrong plantation. All the sooner, since the chief obstacle to the fulfilment of his long-cherished design has been his son, and this is now removed.

Notwithstanding the near prospect of having his spite gratified, Richard Darke keenly feels his humiliation. He has done so ever since the day of his receiving it; and as determinedly has he been nursing his wrath. He has been still further exasperated by a circumstance which has lately occurred—the return of Charles Clancy from Texas. Someone has told him of Clancy having been seen in company with Helen Armstrong—the two walking the woods alone!

Such an interview could not have been with her father’s consent, but clandestine. So much the more aggravating to him—Darke. The thought of it is tearing his heart, as he returns from his fruitless search after the fugitive.

He has left the swamp behind, and is continuing on through a tract of woodland, which separates his father’s plantation from that of Colonel Armstrong, when he sees something that promises relief to his perturbed spirit. It is a woman, making her way through the woods, coming towards him, from the direction of Armstrong’s house.

She is not the colonel’s daughter—neither one. Nor does Dick Darke suppose it either. Though seen indistinctly under the shadow of the trees, he identifies the approaching form as that of Julia—a mulatto maiden, whose special duty it is to attend upon the young ladies of the Armstrong family, “Thank God for the devil’s luck!” he mutters, on making her out. “It’s Jupiter’s sweetheart; his Juno or Leda, yellow-hided as himself. No doubt she’s on her way to keep an appointment with him? No more, that I shall be present at the interview. Two hundred dollars reward for old Jupe, and the fun of giving the damned nigger a good ‘lamming,’ once I lay hand on him. Keep on, Jule, girl! You’ll track him up for me, better than the sharpest scented hound in my kennel.”

While making this soliloquy, the speaker withdraws himself behind a bush; and, concealed by its dense foliage, keeps his eye on the mulatto wench, still wending her way through the thick standing tree trunks.

As there is no path, and the girl is evidently going by stealth, he has reason to believe she is on the errand conjectured.

Indeed he can have no doubt about her being on the way to an interview with Jupiter; and he is now good as certain of soon discovering, and securing, the runaway who has so long contrived to elude him.

After the girl has passed the place of his concealment—which she very soon does—he slips out from behind the bush, and follows her with stealthy tread, still taking care to keep cover between them.

Not long before she comes to a stop; under a grand magnolia, whose spreading branches, with their large laurel like leaves, shadow a vast circumference of ground.

Darke, who has again taken stand behind a fallen tree, where he has a full view of her movements, watches them with eager eyes. Two hundred dollars at stake—two hundred on his own account—fifteen hundred for his father—Jupe’s market value—no wonder at his being all eyes, all ears, on the alert!

What is his astonishment, at seeing the girl take a letter from her pocket, and, standing on tiptoe, drop it into a knot-hole in the magnolia!

This done, she turns shoulder towards the tree; and, without staying longer under its shadow, glides back along the path by which she has come—evidently going home again!

The negro-catcher is not only surprised, but greatly chagrined. He has experienced a double disappointment—the anticipation of earning two hundred dollars, and giving his old slave the lash: both pleasant if realised, but painful the thought in both to be foiled.

Still keeping in concealment, he permits Julia to depart, not only unmolested, but unchallenged. There may be some secret in the letter to concern, though it may not console him. In any case, it will soon be his.

And it soon is, without imparting consolation. Rather the reverse. Whatever the contents of that epistle, so curiously deposited, Richard Darke, on becoming acquainted with them, reels like a drunken man; and to save himself from falling, seeks support against the trunk of the tree!

After a time, recovering, he re-reads the letter, and gazes at a picture—a photograph—also found within the envelope.

Then from his lips come words, low-muttered—words of menace, made emphatic by an oath.

A man’s name is heard among his mutterings, more than once repeated.

As Dick Darke, after thrusting letter and picture into his pocket, strides away from the spot, his clenched teeth, with the lurid light scintillating in his eyes, to this man foretell danger—maybe death.

Chapter Four.

Two good girls.

The dark cloud, long lowering over Colonel Armstrong and his fortunes, is about to fall. A dialogue with his eldest daughter occurring on the same day—indeed in the same hour—when she refused Richard Darke, shows him to have been but too well aware of the prospect of impending ruin.

The disappointed suitor had not long left the presence of the lady, who so laconically denied him, when another appears by her side. A man, too; but no rival of Richard Darke—no lover of Helen Armstrong. The venerable white-haired gentleman, who has taken Darke’s place, is her father, the old colonel himself. His air, on entering the room, betrays uneasiness about the errand of the planter’s son—a suspicion there is something amiss. He is soon made certain of it, by his daughter unreservedly communicating the object of the interview. He says in rejoinder:—

“I supposed that to be his purpose; though, from his coming at this early hour, I feared something worse.”

These words bring a shadow over the countenance of her to whom they are addressed, simultaneous with a glance of inquiry from her grand, glistening eyes.

First exclaiming, then interrogating, she says:—

“Worse! Feared! Father, what should you be afraid of?”

“Never mind, my child; nothing that concerns you. Tell me: in what way did you give him answer?”

“In one little word. I simply said no.”

“That little word will, no doubt, be enough. O Heaven! what is to become of us?”

“Dear father!” demands the beautiful girl, laying her hand upon his shoulder, with a searching look into his eyes; “why do you speak thus? Are you angry with me for refusing him? Surely you would not wish to see me the wife of Richard Darke?”

“You do not love him, Helen?”

“Love him! Can you ask? Love that man!”

“You would not marry him?”

“Would not—could not. I’d prefer death.”

“Enough; I must submit to my fate.”

“Fate, father! What may be the meaning of this? There is some secret—a danger? Trust to me. Let me know all.”

“I may well do that, since it cannot remain much longer a secret. There is danger, Helen—the danger of debt! My estate is mortgaged to the father of this fellow—so much as to put me completely in his power. Everything I possess, land, houses, slaves, may become his at any hour; this day, if he so will it. He is sure to will it now. Your little word ‘no,’ will bring about a big change—the crisis I’ve been long apprehending. Never mind! Let it come! I must meet it like a man. It is for you, daughter—you and your sister—I grieve. My poor dear girls; what a change there will be in your lives, as your prospects! Poverty, coarse fare, coarse garments to wear, and a log-cabin to live in! Henceforth, this must be your lot. I can hold out hope of no other.”

“What of all that, father? I, for one, care not; and I’m sure sister will feel the same. But is there no way to—”

“Save me from bankruptcy, you’d say? You need not ask that. I have spent many a sleepless night thinking it there was. But no; there is only one—that one. It I have never contemplated, even for an instant, knowing it would not do. I was sure you did not love Richard Darke, and would not consent to marry him. You could not, my child?”

Helen Armstrong does not make immediate answer, though there is one ready to leap to her lips.

She hesitates giving it, from a thought, that it may add to the weight of unhappiness pressing upon her father’s spirit.

Mistaking her silence, and perhaps with the spectre of poverty staring him in the face—oft inciting to meanness, even the noblest natures—he repeats the test interrogatory:—

“Tell me, daughter! Could you marry him?”

“Speak candidly,” he continues, “and take time to reflect before answering. If you think you could not be contented—happy—with Richard Darke for your husband, better it should never be. Consult your own heart, and do not be swayed by me, or my necessities. Say, is the thing impossible?”

“I have said. It is impossible!”

For a moment both remain silent; the father drooping, spiritless, as if struck by a galvanic shock; the daughter looking sorrowful, as though she had given it.

She soonest recovering, makes an effort to restore him.

“Dear father!” she exclaims, laying her hand upon his shoulder, and gazing tenderly into his eyes; “you speak of a change in our circumstances—of bankruptcy and other ills. Let them come! For myself I care not. Even if the alternative were death, I’ve told you—I tell you again—I would rather that, than be the wife of Richard Darke.”

“Then his wife you’ll never be! Now, let the subject drop, and the ruin fall! We must prepare for poverty, and Texas!”

“Texas, if you will, but not poverty. Nothing of the kind. The wealth of affection will make you feel rich; and in a lowly log-hut, as in this grand house, you’ll still have mine.”

So speaking, the fair girl flings herself upon her father’s breast, her hand laid across his forehead, the white fingers soothingly caressing it.

The door opens. Another enters the room—another girl, almost fair as she, but brighter, and younger. ’Tis Jessie.

“Not only my affection,” Helen adds, at sight of the newcomer, “but hers as well. Won’t he, sister?”

Sister, wondering what it is all about, nevertheless sees something is wanted of her. She has caught the word “affection,” at the same time observing an afflicted cast upon her father’s countenance. This decides her; and, gliding forward, in another instant she is by his side, clinging to the opposite shoulder, with an arm around his neck.

Thus grouped, the three figures compose a family picture expressive of purest love.

A pleasing tableau to one who knew nothing of what has thus drawn them together; or knowing it, could truly appreciate. For in the faces of all beams affection, which bespeaks a happy, if not prosperous, future—without any doubting fear of either poverty, or Texas.

Chapter Five.

A photograph in the forest.

On the third day, after that on which Richard Darke abstracted the letter from the magnolia, a man is seen strolling along the edge of the cypress swamp. The hour is nearly the same, but the individual altogether different. Only in age does he bear any similarity to the planter’s son; for he is also a youth of some three or four and twenty. In all else he is unlike Dick Darke, as one man could well be to another.

He is of medium size and height, with a figure pleasingly proportioned. His shoulders squarely set, and chest rounded out, tell of great strength; while limbs tersely knit, and a firm elastic tread betoken toughness and activity. Features of smooth, regular outline—the jaws broad, and well balanced; the chin prominent; the nose nearly Grecian—while eminently handsome, proclaim a noble nature, with courage equal to any demand that may be made upon it. Not less the glance of a blue-grey eye, unquailing as an eagle’s.

A grand shock of hair, slightly curled, and dark brown in colour, gives the finishing touch to his fine countenance, as the feather to a Tyrolese hat.

Dressed in a sort of shooting costume, with jack-boots, and gaiters buttoned above them, he carries a gun; which, as can be seen, is a single-barrelled rifle; while at his heels trots a dog of large size, apparently a cross between stag-hound and mastiff, with a spice of terrier in its composition. Such mongrels are not necessarily curs, but often the best breed for backwoods’ sport; where the keenness of scent required to track a deer, needs supplementing by strength and staunchness, when the game chances, as it often does, to be a bear, a wolf, or a panther.

The master of this trebly crossed canine is the man whose name rose upon the lips of Richard Darke, after reading the purloined epistle—Charles Clancy. To him was it addressed, and for him intended, as also the photograph found inside.

Several days have elapsed since his return from Texas, having come back, as already known, to find himself fatherless. During the interval he has remained much at home—a dutiful son, doing all he can to console a sorrowing mother. Only now and then has he sought relaxation in the chase, of which he is devotedly fond. On this occasion he has come down to the cypress swamp; but, having encountered no game, is going back with an empty bag.

He is not in low spirits at his ill success; for he has something to console him—that which gives gladness to his heart—joy almost reaching delirium. She, who has won it, loves him.

This she is Helen Armstrong. She has not signified as much, in words; but by ways equally expressive, and quite as convincing. They have met clandestinely, and so corresponded; the knot-hole in the magnolia serving them as a post-box. At first, only phrases of friendship in their conversation; the same in the letters thus surreptitiously exchanged. For despite Clancy’s courage among men, he is a coward in the presence of women—in hers more than any.

For all this, at their latest interview, he had thrown aside his shyness, and spoken words of love—fervent love, in its last appeal. He had avowed himself wholly hers, and asked her to be wholly his. She declined giving him an answer viva voce, but promised it in writing. He will receive it in a letter, to be deposited in the place convened.

He feels no offence at her having thus put him off. He believes it to have been but a whim of his sweetheart—the caprice of a woman, who has been so much nattered and admired. He knows, that, like the Anne Hathaway of Shakespeare, Helen Armstrong “hath a way” of her own. For she is a girl of no ordinary character, but one of spirit, free and independent, consonant with the scenes and people that surrounded her youth. So far from being offended at her not giving him an immediate answer, he but admires her the more. Like the proud eagle’s mate, she does not condescend to be wooed as the soft cooing dove, nor yield a too easy acquiescence.

Still daily, hourly, does he expect the promised response. And twice, sometimes thrice, a day pays visit to the forest post-office.

Several days have elapsed since their last interview; and yet he has found no letter lying. Little dreams he, that one has been sent, with a carte de visite enclosed; and less of both being in the possession of his greatest enemy on earth.

He is beginning to grow uneasy at the delay, and shape conjectures as to the cause. All the more from knowing, that a great change is soon to take place in the affairs of the Armstrong family. A knowledge which emboldened him to make the proposal he has made.

And now, his day’s hunting done, he is on his way for the tract of woodland in which stands the sweet trysting tree.

He has no thought of stopping, or turning aside; nor would he do so for any small game. But at this moment a deer—a grand antlered stag—comes “loping” along.

Before he can bring his gun to bear upon it, the animal is out of sight; having passed behind the thick standing trunks of the cypresses. He restrains his hound, about to spring off on the slot. The stag has not seen him; and, apparently, going unscared, he hopes to stalk, and again get sight of it.

He has not proceeded over twenty paces, when a sound fills his ears, as well as the woods around. It is the report of a gun, fired by one who cannot be far off. And not at the retreating stag, but himself!

He feels that the bullet has hit him. This, from a stinging sensation in his arm, like the touch of red-hot iron, or a drop of scalding water. He might not know it to be a bullet, but for the crack heard simultaneously—this coming from behind.

The wound, fortunately but a slight one, does not disable him; and, like a tiger stung by javelins, he is round in an instant, ready to return the fire.

There is no one in sight!

As there has been no warning—not a word—he can have no doubt of the intent: some one meaning to murder him!

He is sure about its being an attempt to assassinate him, as of the man who has made it. Richard Darke—certain, as if the crack of the gun had been a voice pronouncing the name.

Clancy’s eyes, flashing angrily, interrogate the forest. The trees stand close, the spaces between shadowy and sombre. For, as said, they are cypresses, and the hour twilight.

He can see nothing save the huge trunks, and their lower limbs, garlanded with ghostly tillandsia here and there draping down to the earth. This baffles him, both by its colour and form. The grey gauze-like festoonery, having a resemblance to ascending smoke, hinders him from perceiving that of the discharged gun.

He can see none. It must have whiffed up suddenly, and become commingled with the moss?

It does not matter much. Neither the twilight obscurity, nor that caused by the overshadowing trees, can prevent his canine companion from discovering the whereabouts of the would-be assassin. On hearing the shot the hound has harked back; and, at some twenty paces off, brought up beside a huge trunk, where it stands fiercely baying, as if at a bear. The tree is buttressed, with “knees” several feet in height rising around. In the dim light, these might easily be mistaken for men.

Clancy is soon among them; and sees crouching between two pilasters, the man who meant to murder him—Richard Darke as conjectured.

Darke makes no attempt at explanation. Clancy calls for none. His rifle is already cocked; and, soon as seeing his adversary, he raises it to his shoulder, exclaiming:—

“Scoundrel! you’ve had the first shot. It’s my turn now.”

Darke does not remain inactive, but leaps—forth from his lurking-place, to obtain more freedom for his arms. The buttresses hinder him from having elbow room. He also elevates his gun; but, perceiving it will be too late, instead of taking aim, he lowers the piece again, and dodges behind the tree.

The movement, quick and subtle, as a squirrel’s bound, saves him. Clancy fires without effect. His ball but pierces through the skirt of Darke’s coat, without touching his body.

With a wild shout of triumph, the latter advances upon his adversary, whose gun is now empty. His own, a double-barrel, has a bullet still undischarged. Deliberately bringing the piece to his shoulder, and covering the victim he is now sure of, he says derisively,—

“What a devilish poor shot you’ve made, Mister Charlie Clancy! A sorry marksman—to miss a man scarce six feet from the muzzle of your gun! I shan’t miss you. Turn about’s fair play. I’ve had the first, and I’ll have the last. Dog! take your death shot!”

While delivering the dread speech, his finger presses the trigger; the crack comes, with the flash and fiery jet.

For some seconds Clancy is invisible, the sulphurous smoke forming a nimbus around him. When it ascends, he is seen prostrate upon the earth; the blood gushing from a wound in his breast, and spurting over his waistcoat.

He appears writhing in his death agony.

And evidently thinks so himself, from his words spoken in slow, choking utterance,—

“Richard Darke—you have killed—murdered me!”

“I meant to do it,” is the unpitying response.

“O Heavens! You horrid wretch! Why—why—”

“Bah! what are you blubbering about? You know why. If not, I shall tell you—Helen Armstrong, After all, it isn’t jealousy that’s made me kill you; only your impudence, to suppose you had a chance with her. You hadn’t; she never cared a straw for you. Perhaps, before dying, it may be some consolation for you to know she didn’t. I’ve got the proof. Since it isn’t likely you’ll ever see herself again, it may give you a pleasure to look at her portrait. Here it is! The sweet girl sent it me this very morning, with her autograph attached, as you see. A capital likeness, isn’t it?”

The inhuman wretch stooping down, holds the photograph before the eyes of the dying man, gradually growing dim.

But only death could hinder them from turning towards that sun-painted picture—the portrait of her who has his heart.

He gazes on it lovingly, but not long. For the script underneath claims his attention. In this he recognises her handwriting, well-known to him. Terrible the despair that sweeps through his soul, as he deciphers it:—

“Helen Armstrong.—For him she loves.”

The picture is in the possession of Richard Darke. To him have the sweet words been vouchsafed!

“A charming creature!” Darke tauntingly continues, kissing the carte, and pouring the venomous speech into his victim’s ear. “It’s the very counterpart of her sweet self. As I said, she sent it me this morning. Come, Clancy! Before giving up the ghost, tell me what you think of it. Isn’t it an excellent likeness?”

To the inhuman interrogatory Clancy makes no response—either by word, look, or gesture. His lips are mute, his eyes without light of life, his limbs and body motionless as the mud on which they lie.

A short, but profane, speech terminates the terrible episode; four words of most heartless signification:—

“Damn him; he’s dead!”

Chapter Six.

A coon-chase interrupted.

Notwithstanding the solitude of the place where the strife, apparently fatal, has occurred, and the slight chances of its being seen, its sounds have been heard. The shots, the excited speeches, and angry exclamations, have reached the ears of one who can well interpret them. This is a coon-hunter.

There is no district in the Southern States without its coon-hunter. In most, many of them; but in each, one who is noted. And, notedly, he is a negro. The pastime is too tame, or too humble, to tempt the white man. Sometimes the sons of “poor white trash” take part in it; but it is usually delivered over to the “darkey.”

In the old times of slavery every plantation could boast of one, or more, of these sable Nimrods; and they are not yet extinct. To them coon-catching is a profit, as well as sport; the skins keeping them in tobacco—and whisky, when addicted to drinking it. The flesh, too, though little esteemed by white palates, is a bonne-bouche to the negro, with whom animal food is a scarce commodity. It often furnishes him with the substance for a savoury roast.

The plantation of Ephraim Darke is no exception to the general rule. It, too, has its coon-hunter—a negro named, or nicknamed, “Blue Bill;” the qualifying term bestowed, from a cerulean tinge, that in certain lights appears upon the surface of his sable epidermis. Otherwise he is black as ebony.

Blue Bill is a mighty hunter of his kind, passionately fond of the coon-chase—too much, indeed, for his own personal safety. It carries him abroad, when the discipline of the plantation requires him to be at home; and more than once, for so absenting himself, have his shoulders been scored by the “cowskin.”

Still the punishment has not cured him of his proclivity. Unluckily for Richard Darke, it has not. For on the evening of Clancy’s being shot down, as described, Blue Bill chances to be abroad; and, with a small cur, which he has trained to his favourite chase, is scouring the timber near the edge of the cypress swamp.

He has “treed” an old he-coon, and is just preparing to ascend to the creature’s nest—a cavity in a sycamore high up—when a deer comes dashing by. Soon after a shot startles him. He is more disturbed at the peculiar crack, than by the mere fact of its being the report of a gun. His ear, accustomed to such sounds, tells him the report has proceeded from a fowling-piece, belonging to his young master—just then the last man he would wish to meet. He is away from the “quarter” without “pass,” or permission of any kind.

His first impulse is, to continue the ascent of the sycamore, and conceal himself among its branches.

But his dog, remaining below—that will betray him?

While hurriedly reflecting on what he had best do, he hears a second shot. Then a third, coming quickly after; while preceding, and mingling with the reports are men’s voices, apparently in mad expostulation. He hears, too, the angry growling of a hound, at intervals barking and baying.

“Gorramity!” mutters Blue Bill; “dar’s a skrimmage goin’ on dar—a fight, I reck’n, an’ seemin’ to be def! Clar enuf who dat fight’s between. De fuss shot wa’ Mass’ Dick’s double-barrel; de oder am Charl Clancy rifle. By golly! ’taint safe dis child be seen hya, no how. Whar kin a hide maseff?”

Again he glances upward, scanning the sycamore: then down at his dog; and once more to the trunk of the tree. This is embraced by a creeper—a gigantic grape-vine—up which an ascent may easily be made; so easily, there need be no difficulty in carrying the cur along. It was the ladder he intended using to get at the treed coon.

With the fear of his young master coming past—and if so, surely “cow-hiding” him—he feels there is no time to be wasted in vacillation.

Nor does he waste any. Without further stay, he flings his arm around the coon-dog: raises the unresisting animal from the earth; and “swarms” up the creeper, like a she-bear carrying her cub.

In ten seconds after, he is snugly ensconced in a crotch of the sycamore; screened from observation of any one who may pass underneath, by the profuse foliage of the parasite.

Feeling fairly secure, he once more sets himself to listen. And, listening attentively, he hears the same voices as before. But not any longer in angry ejaculation. The tones are tranquil, as though the two men were now quietly conversing. One says but a word or two; the other all. Then the last alone appears to speak, as if in soliloquy, or from the first failing to make response.

The sudden transition of tone has in it something strange—a contrast inexplicable.

The coon-hunter can tell, that he continuing to talk is his young master, Richard Darke; though he cannot catch, the words, much less make out their meaning. The distance is too great, and the current of sound interrupted by the thick standing trunks of the cypresses.

At length, also, the monologue ends; soon after, succeeded by a short exclamatory phrase, in voice louder and more earnest.

Then there is silence; so profound, that Blue Bill hears but his own heart, beating in loud sonorous thumps—louder from his ribs being contiguous to the hollow trunk of the tree.

Chapter Seven.

Murder without remorse.

The breathless silence, succeeding Darke’s profane speech, is awe-inspiring; death-like, as though every living creature in the forest had been suddenly struck dumb, or dead, too.

Unspeakably, incredibly atrocious is the behaviour of the man who has remained master of the ground. During the contest, Dick Darke has shown the cunning of the fox, combined with the fiercer treachery of the tiger; victorious, his conduct seems a combination of the jackal and vulture.

Stooping over his fallen foe, to assure himself that the latter no longer lives, he says,—

“Dead, I take it.”

These are his cool words; after which, as though still in doubt, he bends lower, and listens. At the same time he clutches the handle of his hunting knife, as with the intent to plunge its blade into the body.

He sees there is no need. It is breathless, almost bloodless—clearly a corpse!

Believing it so, he resumes his erect attitude, exclaiming in louder tone, and with like profanity as before,—

“Yes, dead, damn him!”

As the assassin bends over the body of his fallen foe, he shows no sign of contrition, for the cruel deed he has done. No feeling save that of satisfied vengeance; no emotion that resembles remorse. On the contrary, his cold animal eyes continue to sparkle with jealous hate; while his hand has moved mechanically to the hilt of his knife, as though he meant to mutilate the form he has laid lifeless. Its beauty, even in death, seems to embitter his spirit!

But soon, a sense of danger comes creeping over him, and fear takes shape in his soul. For, beyond doubt, he has done murder.

“No!” he says, in an effort at self-justification. “Nothing of the sort. I’ve killed him; that’s true; but he’s had the chance to kill me. They’ll see that his gun’s discharged; and here’s his bullet gone through the skirt of my coat. By thunder, ’twas a close shave!”

For a time he stands reflecting—his glance now turned towards the body, now sent searchingly through the trees, as though in dread of some one coming that way.

Not much likelihood of this. The spot is one of perfect solitude, as is always a cypress forest. There is no path near, accustomed to be trodden by the traveller. The planter has no business among those great buttressed trunks. The woodman will never assail them with his axe. Only a stalking hunter, or perhaps some runaway slave, is at all likely to stray thither.

Again soliloquising, he says,—

“Shall I put a bold face upon it, and confess to having killed him? I can say we met while out hunting; quarrelled, and fought—a fair fight; shot for shot; my luck to have the last. Will that story stand?”

A pause in the soliloquy; a glance at the prostrate form; another, which interrogates the scene around, taking in the huge unshapely trunks, their long outstretched limbs, with the pall-like festoonery of Spanish moss; a thought about the loneliness of the place, and its fitness for concealing a dead body.

Like the lightning’s flashes, all this flits through the mind of the murderer. The result, to divert him from his half-formed resolution—perceiving its futility.

“It won’t do,” he mutters, his speech indicating the change. “No, that it won’t! Better say nothing about what’s happened. They’re not likely to look for him here...”

Again he glances inquiringly around, with a view to secreting the corpse. He has made up his mind to this.

A sluggish creak meanders among the trees, some two hundred yards from the spot. At about a like distance below, it discharges itself into the stagnant reservoir of the swamp.

Its waters are dark, from the overshadowing of the cypresses, and deep enough for the purpose he is planning.

But to carry the body thither will require an effort of strength; and to drag it would be sure to leave traces.

In view of this difficulty, he says to himself,—

“I’ll let it lie where it is. No one ever comes along hero—not likely. At the same time, I take it, there can be no harm in hiding him a little. So, Charley Clancy, if I have sent you to kingdom come, I shan’t leave your bones unburied. Your ghost might haunt me, if I did. To hinder that you shall have interment.”

In the midst of this horrid mockery, he rests his gun against a tree, and commences dragging the Spanish moss from the branches above. The beard-like parasite comes off in flakes—in armfuls. Half a dozen he flings over the still palpitating corpse; then pitches on top some pieces of dead wood, to prevent any stray breeze from sweeping off the hoary shroud.

After strewing other tufts around, to conceal the blood and boot tracks, he rests from his labour, and for a time stands surveying what he has done.

At length seeming satisfied, he again grasps hold of his gun; and is about taking departure from the place, when a sound, striking his ear, causes him to start. No wonder, since it seems the voice of one wailing for the dead!

At first he is affrighted, fearfully so; but recovers himself on learning the cause.

“Only the dog!” he mutters, perceiving Clancy’s hound at a distance, among the trees.

On its master being shot down, the animal had scampered off—perhaps fearing a similar fate. It had not gone far, and is now returning—by little and little, drawing nearer to the dangerous spot.

The creature seems struggling between two instincts—affection for its fallen master, and fear for itself.

As Darke’s gun is empty, he endeavours to entice the dog within reach of his knife. Despite his coaxing, it will not come!

Hastily ramming a cartridge into the right-hand barrel, he aims, and fires.

The shot takes effect; the ball passing through the fleshy part of the dog’s neck. Only to crease the skin, and draw forth a spurt of blood.

The hound hit, and further frightened, gives out a wild howl, and goes off, without sign of return.

Equally wild are the words that leap from the lips of Richard Darke, as he stands gazing after.

“Great God!” he cries; “I’ve done an infernal foolish thing. The cur will go home to Clancy’s house. That’ll tell a tale, sure to set people searching. Ay, and it may run back here, guiding them to the spot. Holy hell!”

While speaking, the murderer turns pale. It is the first time for him to experience real fear. In such an out-of-the-way place he has felt confident of concealing the body, and along with it the bloody deed. Then, he had not taken the dog into account, and the odds were in his favour. Now, with the latter adrift, they are heavily against him.

It needs no calculation of chances to make this clear. Nor is it any doubt which causes him to stand hesitating. His irresolution springs from uncertainty as to what course he shall pursue.

One thing certain—he must not remain there. The hound has gone off howling. It is two miles to the widow Clancy’s house; but there is an odd squatter’s cabin and clearing between. A dog going in that guise, blood-bedraggled, in full cry of distress, will be sure of being seen—equally sure to raise an alarm.

On the probable, or possible, contingencies Dick Darke does not stand long reflecting. Despite its solitude, the cypress forest is not the place for tranquil thought—at least, not now for him. Far off through the trees he can hear the wail of the wounded Molossian.

Is it fancy, or does he also hear human voices?

He stays not to be sure. Beside that gory corpse, shrouded though it be, he dares not remain a moment longer.

Hastily shouldering his gun, he strikes off through the trees; at first in quick step; then in double; this increasing to a rapid run.

He retreats in a direction contrary to that taken by the dog. It is also different from the way leading to his father’s house. It forces him still further into the swamp—across sloughs, and through soft mud, where he makes footmarks. Though he has carefully concealed Clancy’s corpse, and obliterated all other traces of the strife, in his “scare,” he does not think of those he is now making.

The murderer is only—cunning before the crime. After it, if he have conscience, or be deficient in coolness, he loses self-possession, and is pretty sure to leave behind something which will furnish a clue for the detective.

So is it with Richard Darke. As he retreats from the scene of his diabolical deed, his only thought is to put space between himself and the spot where he has shed innocent blood; to get beyond earshot of those canine cries, that seem commingled with the shouts of men—the voices of avengers!

Chapter Eight.

The coon-hunter cautious.

During the time that Darke is engaged in covering up Clancy’s body, and afterwards occupied in the attempt to kill his dog, the coon-hunter, squatted in the sycamore fork, sticks to his seat like “death to a dead nigger.” And all the time trembling. Not without reason. For the silence succeeding the short exclamatory speech has not re-assured him. He believes it to be but a lull, denoting some pause in the action, and that one, or both, of the actors is still upon the ground. If only one, it will be his master, whose monologue was last heard. During the stillness, somewhat prolonged, he continues to shape conjectures and put questions to himself, as to what can have been the fracas, and its cause. Undoubtedly a “shooting scrape” between Dick Darke and Charles Clancy. But how has it terminated, or is the end yet come? Has one of the combatants been killed, or gone away? Or have both forsaken the spot where they have been trying to spill each other’s blood?

While thus interrogating himself, a new sound disturbs the tranquillity of the forest—the same, which the assassin at first fancied was the voice of one wailing for his victim. The coon-hunter has no such delusion. Soon as hearing, he recognises the tongue of a stag-hound, knowing it to be Clancy’s. He is only astray about its peculiar tone, now quite changed. The animal is neither barking nor baying; nor yet does it yelp as if suffering chastisement. The soft tremulous whine, that comes pealing in prolonged reverberation through the trunks of the cypresses, proclaims distress of a different kind—as of a dog asleep and dreaming!

And now, once more a man’s voice, his master’s. It too changed in tone. No longer in angry exclaim, or quiet conversation, but as if earnestly entreating; the speech evidently not addressed to Clancy, but the hound.

Strange all this; and so thinks the coon-hunter. He has but little time to dwell on it, before another sound waking the echoes of the forest, interrupts the current of his reflections. Another shot! This time, as twice before, the broad round boom of a smooth-bore, so different from the short sharp “spang” of a rifle.

Thoroughly versed in the distinction—indeed an adept—Blue Bill knows from whose gun the shot has been discharged. It is the double-barrel belonging to Richard Darke. All the more reason for him to hug close to his concealment.

And not the less to be careful about the behaviour of his own dog, which he is holding in hard embrace. For hearing the bound, the cur is disposed to give response; would do so but for the muscular fingers of its master closed chokingly around its throat, at intervals detached to give it a cautionary cuff.

After the shot the stag-hound continues its lugubrious cries; but again with altered intonation, and less distinctly heard; as though the animal had gone farther off, and were still making away.

But now a new noise strikes upon the coon-hunter’s ears; one at first slight, but rapidly growing louder. It is the tread of footsteps, accompanied by a swishing among the palmettoes, that form an underwood along the edge of the swamp. Some one is passing through them, advancing towards the tree where he is concealed.

More than ever does he tremble on his perch; tighter than ever clutching the throat of his canine companion. For he is sure, that the man whose footsteps speak approach, is his master, or rather his master’s son. The sounds seem to indicate great haste—a retreat rapid, headlong, confused. On which the peccant slave bases a hope of escaping observation, and too probable chastisement. Correct in his conjecture, as in the prognostication, in a few seconds after he sees Richard Darke coming between the trees; running as for very life—the more like it that he goes crouchingly; at intervals stopping to look back and listen, with chin almost touching his shoulder!

When opposite the sycamore—indeed under it—he makes pause longer than usual. The perspiration stands in beads upon his forehead, pours down his cheeks, over his eyebrows, almost blinding him. He whips a kerchief out of his coat pocket, and wipes it off. While so occupied, he does not perceive that he has let something drop—something white that came out along with the kerchief. Replacing the piece of cambric he hurries on again, leaving it behind; on, on, till the dull thud of his footfall, and the crisp rustling of the stiff fan-like leaves, become both blended with the ordinary noises of the forest.

Then, but not before, does Blue Bill think of forsaking the fork. Descending from his irksome seat, he approaches the white thing left lying on the ground—a letter enveloped in the ordinary way. He takes it up, and sees it has been already opened. He thinks not of drawing out the sheet folded inside. It would be no use; since the coon-hunter cannot read. Still, an instinct tells him, the little bit of treasure-trove may some time, and in some way, prove useful. So forecasting, he slips it into his pocket.

This done he stands reflecting. No noise to disturb him now. Darke’s footsteps have died away in the distance, leaving swamp and cypress forest restored to their habitual stillness. The only sound, Blue Bill hears, is the beating of his own heart, yet loud enough.

No longer thinks he of the coon he has succeeded in treeing. The animal, late devoted to certain death, will owe its escape to an accident, and may now repose securely within its cave. Its pursuer has other thoughts—emotions, strong enough to drive coon-hunting clean out of his head. Among these are apprehensions about his own safety. Though unseen by Richard Darke—his presence there unsuspected—he knows that an unlucky chance has placed him in a position of danger. That a sinister deed has been done he is sure.

Under the circumstances, how is he to act? Proceed to the place whence the shots came, and ascertain what has actually occurred?

At first he thinks of doing this; but surrenders the intention. Affrighted by what is already known to him, he dares not know more. His young master may be a murderer? The way in which he was retreating almost said as much. Is he, Blue Bill, to make himself acquainted with the crime, and bear witness against him who has committed it? As a slave, he knows his testimony will count for little in a court of justice. And as the slave of Ephraim Darke, as little would his life be worth after giving it.

The last reflection decides him; and, still carrying the coon-dog under his arm, he parts from the spot, in timid skulking gait, never stopping, not feeling safe, till he finds himself inside the limits of the “negro quarter.”

Chapter Nine.

An assassin in retreat.

Athwart the thick timber, going as one pursued—in a track straight as the underwood will allow—breaking through it like a chased bear—now stumbling over a fallen log, now caught in a trailing grape-vine—Richard Darke flees from the place where he has laid his rival low.

He makes neither stop, nor stay. If so, only for a few instants, just long enough to listen, and if possible learn whether he is being followed.

Whether or not, he fancies it; again starting off, with terror in his looks, and trembling in his limbs. The sangfroid he exhibited while bending over the dead body of his victim, and afterwards concealing it, has quite forsaken him now. Then he was confident, there could be no witness of the deed—nothing to connect him with it as the doer. Since, there is a change—the unthought-of presence of the dog having produced it. Or, rather, the thought of the animal having escaped. This, and his own imagination.

For more than a mile he keeps on, in headlong reckless rushing. Until fatigue overtaking him, his terror becomes less impulsive, his fancies freer from exaggeration; and, believing himself far enough from the scene of danger, he at length desists from flight, and comes to a dead stop.

Sitting down upon a log, he draws forth his pocket-handkerchief, and wipes the sweat from his face. For he is perspiring at every pore, panting, palpitating. He now finds time to reflect; his first reflection being the absurdity of his making such precipitate retreat; his next, its imprudence.

“I’ve been a fool for it,” he mutters. “Suppose that some one has seen me? ’Twill only have made things worse. And what have I been running away from? A dead body, and a living dog! Why should I care for either? Even though the adage be true—about a live dog better than a dead lion. Let me hope the hound won’t tell a tale upon me. For certain the shot hit him. That’s nothing. Who could say what sort of ball, or the kind of gun it came from? No danger in that. I’d be stupid to think there could be. Well, it’s all over now, and the question is: what next?”

For some minutes he remains upon the log, with the gun resting across his knees, and his head bent over the barrels. He appears engaged in some abstruse calculation. A new thought has sprang up in his mind—a scheme requiring all his intellectual power to elaborate.

“I shall keep that tryst,” he says, in soliloquy, seeming at length to have settled it. “Yes; I’ll meet her under the magnolia. Who can tell what changes may occur in the heart of a woman? In history I had a royal namesake—an English king, with an ugly hump on his shoulders—as he’s said himself, ‘deformed, unfinished, sent into the world scarce half made up,’ so that the ‘dogs barked at him,’ just as this brute of Clancy’s has been doing at me. And this royal Richard, shaped ‘so lamely and unfashionable,’ made court to a woman, whose husband he had just assassinated—more than a woman, a proud queen—and more than wooed, he subdued her. This ought to encourage me; the better that I, Richard Darke, am neither halt, nor hunchbacked. No, nor yet unfashionable, as many a Mississippian girl says, and more than one is ready to swear.

“Proud Helen Armstrong may be, and is; proud as England’s queen herself. For all that, I’ve got something to subdue her—a scheme, cunning as that of my royal namesake. May God, or the Devil, grant me like success!”

At the moment of giving utterance to the profane prayer, he rises to his feet. Then, taking out his watch, consults it.

It is too dark for him to see the dial; but springing open the glass, he gropes against it, feeling for the hands.

“Half-past nine,” he mutters, after making out the time. “Ten is the hour of her assignation. No chance for me to get home before, and then over to Armstrong’s wood-ground. It’s more than two miles from here. What matters my going home? Nor any need changing this dress. She won’t notice the hole in the skirt. If she do, she wouldn’t think of what caused it—above all it’s being a bullet. Well, I must be off! It will never do to keep the young lady waiting. If she don’t feel disappointed at seeing me, bless her! If she do, I shall curse her! What’s passed prepares me for either event. In any case, I shall have satisfaction for the slight she’s put upon me. By God I’ll get that!”

He is moving away, when a thought occurs staying him. He is not quite certain about the exact hour of Helen Armstrong’s tryst, conveyed in her letter to Clancy. In the madness of his mind ever since perusing that epistle, no wonder he should confuse circumstances, and forget dates.

To make sure, he plunges his hand into the pocket, where he deposited both letter and photograph—after holding the latter before the eyes of his dying foeman, and witnessing the fatal effect. With all his diabolical hardihood, he had been awed by this—so as to thrust the papers into his pocket, hastily, carelessly.

They are no longer there!

He searches in his other pockets—in all of them, with like result. He examines his bullet-pouch and gamebag. But finds no letter, no photograph, not a scrap of paper, in any! The stolen epistle, its envelope, the enclosed carte de visite—all are absent.

After ransacking his pockets, turning them inside out, he comes to the conclusion that the precious papers are lost.

It startles, and for a moment dismays him. Where are they? He must have let them fall in his hasty retreat through the trees; or left them by the dead body.

Shall he go back in search of them?

No—no—no! He does not dare to return upon that track. The forest path is too sombre, too solitary, now. By the margin of the dank lagoon, under the ghostly shadow of the cypresses, he might meet the ghost of the man murdered!

And why should he go back? After all, there is no need; nothing in the letter which can in any way compromise him. Why should he care to recover it?

“It may go to the devil, her picture along! Let both rot where I suppose I must have dropped them—in the mud, or among the palmettoes. No matter where. But it does matter, my being under the magnolia at the right time, to meet her. Then shall I learn my fate—know it, for better, for worse. If the former, I’ll continue to believe in the story of Richard Plantagenet; if the latter, Richard Darke won’t much care what becomes of him.”

So ending his strange soliloquy, with a corresponding cast upon his countenance, the assassin rebuttons his coat—thrown open in search for the missing papers. Then, flinging the double-barrelled fowling-piece—the murder-gun—over his sinister shoulder, he strides off to keep an appointment not made for him, but for the man he has murdered!

Chapter Ten.

The eve of departure.

The evil day has arrived; the ruin, foreseen, has fallen.

The mortgage deed, so long held in menace over the head of Archibald Armstrong—suspended, as it were, by a thread, like the sword of Damocles—is to be put into execution. Darke has demanded immediate payment of the debt, coupled with threat of foreclosure.

The demand is a month old, the threat has been carried out, and the foreclosure effected. The thread having been cut, the keen blade of adversity has come down, severing the tie which attached Colonel Armstrong to his property, as it to him. Yesterday, he was owner, reputedly, of one of the finest plantations along the line of the Mississippi river, an hundred able-bodied negroes hoeing cotton in his fields, with fifty more picking it from the pod, and “ginning” the staple clear of seed; to-day, he is but their owner in seeming, Ephraim Darke being this in reality. And in another day the apparent ownership will end: for Darke has given his debtor notice to yield up houses, lands, slaves, plantation-stock—in short, everything he possesses.

In vain has Armstrong striven against this adverse fate; in vain made endeavours to avert it. When men are falling, false friends grow falser; even true ones becoming cold. Sinister chance also against him; a time of panic—a crisis in the money-market—as it always is on such occasions, when interest runs high, and second mortgages are sneered at by those who grant loans.

As no one—neither friend nor financial speculator—comes to Armstrong’s rescue, he has no alternative but submit.

Too proud, to make appeal to his inexorable creditor—indeed deeming it idle—he vouchsafes no answer to the notice of foreclosure, beyond saying: “Let it be done.”

At a later period he gives ear to a proposal, coming from the mortgagee: to put a valuation upon the property, and save the expenses of a public sale, by disposing of it privately to Darke himself.