Pugilistic Veteran. "Come erlong, young un—come erlong; put some beef into it. That ain't the stuff I did at your age."

The Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 146, June 3, 1914, by Various This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol. 146, June 3, 1914 Author: Various Release Date: June 2, 2008 [EBook #25676] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH *** Produced by Neville Allen, Malcolm Farmer and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

"When the King and Queen visit Nottinghamshire as the guests of the Duke and Duchess of Portland at Welbeck, three representative colliery owners and four working miners will," we read, "be presented to their Majesties at Forest Town." A most embarrassing gift, we should say, and one which cannot, without hurting susceptibilities, be passed on to the Zoological Society.

Are the French, we wonder, losing that valuable quality of tact for which they have so long enjoyed a reputation? Amongst the Ministers introduced at Paris to King Christian of Denmark, who enjoys his designation of "The tall King," was M. Maginol, who is an inch taller than His Majesty. He should surely have been told to stay at home.

In the Bow County Court, last week, a woman litigant carried with her, for luck, an ornamental horse-shoe, measuring at least a foot in length, and won her case. Magistrates trust that this idea, pretty as it is, may not spread to Suffragettes of acknowledged markmanship.

Extract from an account in The Daily Chronicle of the Silver King disturbance:—"The officers held her down, and, with the ready aid of members of the audience, managed to keep her fairly quiet, though she bit those who tried to hold their hands over her mouth. A stage hand was sent for ..." If we are left to assume that she did not like the taste of that, we regard it as an insult to a deserving profession.

"Do people read as much as they used to?" is a question which is often asked nowadays. There are signs that they are, anyhow, getting more particular as to what they read. Even the House of Commons is becoming fastidious. It refused, the other day, to read the Weekly Rest Day Bill a second time, and the Third Reading of the Home Rule Bill was regarded as a waste of time and intelligence.

The superstitions of great men are always interesting, and we hear that, after his experience at Ipswich and on the Stock Exchange, Mr. Lloyd George is now firmly convinced that it is unlucky for him to have anything to do with anyone whose name ends in "oni."

Professor Metchnikoff, the great authority on the prevention of senile decay, will shortly celebrate his seventieth birthday, and a project is on foot to congratulate him on his good fortune in living so long.

The Central Telephone Exchange is now prepared to wake up subscribers at any hour for threepence a call, and it is forming an "Early Risers' List." So many persons are anxious to take a rise out of the Telephone Service that the success of the innovation is assured.

By crossing the Channel in a biplane, the Princess Loewenstein-Wertheim has earned the right to be addressed as "Your Altitude."

We see from an advertisement that we now have in our midst an "Institute of Hand Development." This should prove most useful to parents who own troublesome children. No doubt after a short course of instruction the spanking power of the hand may be doubled.

Reading that two houses in King Street, Cheapside, were sold last week "for a price equal to nearly £13 10s. per foot super," a correspondent asks, "What is a super foot?" If it is not a City policeman's we give it up.

There are now 168 house-boats on the Thames, states the annual report of the Conservators, and it has been suggested that a race between these craft might form an attractive item at Henley.

Shoals of mackerel entered Dover Bay last week, and many of the fish were caught by what is described as a novel form of bait, namely a cigarette paper on a hook drawn through the water in the same way as a "spinner." As a matter of fact we believe that smoked salmon are usually caught this way.

We learn from an announcement in The Medical Officer that Dr. T. S. McSwiney has sold his practice to Dr. Hogg—and it only remains for us to hope that Dr. Hogg has not bought a pig in a poke.

It looks as if even in America the respect for Titles is on the wane. We venture to extract the following item from the catalogue of an American dealer in autographs:—"Bryce, James, Viscount. Historian. Original MS. 33 pp. 4to of his article 'Equality.' In this he says:—'The evils of hereditary titles exceed their advantage. In Great Britain they produce snobbishness both among those who possess them and those who do not, without (as a rule) any corresponding sense of duty to sustain the credit of the family or the caste. Their abolition would be clear gain....' And now he is a Viscount. Price 30 dollars."

Pugilistic Veteran. "Come erlong, young un—come erlong; put some beef into it. That ain't the stuff I did at your age."

From a letter in The East African Standard:—

"We have indeed reached the stage known as the last straw on the camel's back, and I, for one, am quite prepared, as one of the least component parts of that camel, to add my iota to the endeavour to kick over the traces. Let us unite and, marching shoulder to shoulder and eye to eye, set sail for that glorious and equally well-known goal—'Who pays the piper calls the tune.'"

No man of spirit could resist so stirring an appeal.

From the latest Official Report on anti-aircraft guns:—

"Another arrangement, constructed by Messrs. Lenz, is that in which the layer's seat is attached to the muzzle of the gun."

"The mediators who are to intervene to bring peace in Mexico have begun their sittings at Niagara in a situation which is full of perplexity."

The Saturday Westminster Gazette.

If the spot alluded to is immediately under the Falls we can well understand their lack of confidence.

["The effect, however," (of the Nationalists' enthusiasm) "was somewhat marred by the apathy of the Liberals."—"The Times," on the Third Reading of the Home Rule Bill.]

Why was the timbrel's note suppressed?

Why rang there not a rousing pæan

When Ireland, waiting to be blest,

Hanging about for half an æon,

Achieved at length the heights of Heaven

By a majority of 77?

Why was the trombone's music dumb?

Why did the tears of joy not splash on

The vellum of the big bass drum

To indicate your ardent passion

For that Green Isle across the way

Which you must really visit some fine day?

Was it the three elections (by-)

That left you for the time prostrated

(They should have raised your spirits high,

So Infant Samuel calculated),

Concluding with the worst of slips which

Occurred between the cup and mouth at Ipswich?

Was it because your Home Rule Bill

(Though perfect) craves to be amended,

And to the Lords you love so ill

That you would gladly see 'em ended

The delicate task has been referred

Of patching up the places where you erred?

Was it that you were pained to find

How Ulster took your noble Charter;

With what composure she declined

To bear it like a Christian martyr;

How there she stood, too firm to shake,

With no idea of stepping to the stake?

Or did you hear a still small voice

Under your waistcoat, where your heart is:

"We fought by contract, not by choice,

Ay, and the spoils are not our party's;

The Tories may be beat, but we know

This is not Asquith's, it is Redmond's beano"?

Or did you doubt if all was right

With Erin when you heard O'Brien

Foreboding doom by second sight

And roaring like a wounded lion,

And saw what venomed hate convulsed her

Apart from any little tiff with Ulster?

Or could it be you felt so fain

About your imminent vacation

That the same breast could not contain

The joy of Ireland-as-a-Nation?

There wasn't room for both inside,

And so the Bill gave way to Whitsuntide?

If that was why you would not hail

Your chance of bringing down the ceiling,

But let the holiday mood prevail,

I understand, and share your feeling;

I find my bowl of joy o'er-bubbling

Whenever Parliament has ceased from troubling.

The amazing upheaval in provincial journalism consequent on the issue of the Little Titley Parish Magazine at one penny is the sole topic of conversation in Dampshire, to the exclusion of Ulster, Mexico, the scarcity of meat, and even golf. Perhaps the most remarkable and significant outcome of this momentous change is the sudden abandonment by the Nether Wambleton Parish Magazine of its familiar claim that its sale amounted to an average which, if tested, would show an excess of two to one over any other church periodical in Wessex. The Nether Wambleton Parish Magazine in its May number contented itself with asserting that it is the largest religious monthly in North Dampshire, also that its average sale, if tested, would show a circulation calculated to stagger humanity.

These assertions have led to a long and recriminatory correspondence in the columns of The Tittersham Observer. The Rev. Eldred Bolster, Vicar of Little Titley, writing in the issue of May 9th, characterises them as grotesque and preposterous fabrications. He points out, to begin with, that the Nether Wambleton Parish Magazine only contains eighteen pages, of which no fewer than sixteen are provided from London and have no reference to local matters, while the Little Titley Parish Magazine contains twenty-four pages, of which no fewer than four are entirely devoted to parish affairs. As regards circulation, Mr. Bolster sarcastically observes that humanity is sometimes staggered by the infinitely little even more than by the infinitely great, and challenges the Vicar of Nether Wambleton to publish the net figures of the sale of his periodical.

The challenge was promptly taken up, and in the issue of The Tittersham Observer of May 16th the Vicar of Nether Wambleton prints the following statement of the sales of his magazine since April, 1913. The figures are as follows:—

| 1913 | May | 54 |

| " | June | 57 |

| " | July | 51 |

| " | August | 49 |

| " | September | 52 |

| " | October | 58 |

| " | November | 59 |

| " | December | 57 |

| 1914 | January | 61 |

| " | February | 55 |

| " | March | 59 |

The statement is signed by the Rev. Auriel Potts, Vicar of Nether Wambleton, and Andrew Jobling and Septimus Wicks, sidesmen.

This evasive reply could not be expected to satisfy Mr. Bolster, who returns to the charge in The Tittersham Observer of the 23rd May. Side by side with the sale figures of the Nether Wambleton Parish Magazine he prints those of his own periodical, which for the same period never fell below sixty and on the occasion of the Harvest Festival reached a total of seventy-nine. With scathing emphasis he points out that the Nether Wambleton figures cease with the month in which Little Titley came down to one penny, since which the latter has gone up by leaps and bounds, no fewer than eighty-four copies of the May number having already been sold. Moreover, these are net sales, while the Nether Wambleton figures (for all he knows) represent gross circulation, including copies gratuitously distributed at mothers' meetings, choir treats and other gatherings.

It might have been thought that Mr. Potts would have withdrawn from the controversial arena after this painful exposure, but with a persistence worthy of a better cause he rejoins in a long and irrelevant letter in The Tittersham Observer of the 30th May. He undoubtedly scores a point in maintaining that the Nether Wambleton Parish Magazine is the largest in Wessex on the strength of the fact that its page is half-an-inch longer and a quarter-of-an-inch wider than that of its rival, but in[Pg 424] other respects his reply can hardly be considered convincing. For instance, he lays stress on the [Pg 425]fact that the gigantic gooseberry grown in his parish and chronicled in his current issue was appreciably greater in diameter than that described in the corresponding issue of the rival publication. He also dwells on the superior artistic quality of the programme of the Penny Reading in his parish hall as compared with that of the Little Titley Temperance Reed Band at their annual concert. And, finally, with ill-timed levity, he disclaims any intention of "bolstering up" his parish magazine by crude appeals to democratic sentiment—an allusion to the name of the Vicar of Little Titley which has been deeply resented by the numerous admirers of that esteemed cleric.

The saddest feature about this painful controversy is the personal estrangement which it has brought about between the two Vicars. Only six months ago the Rev. Mr. Bolster presided at a meeting at which the friends and parishioners of the Rev. Mr. Potts presented him with a testimonial and a set of electro-plated fish-knives to commemorate the celebration of his silver wedding. The testimonial, which was composed by Mr. Bolster, was a document couched in terms of the most affectionate admiration, and special reference was made to Mr. Potts's editorial abilities and the extraordinarily high literary standard of his parish magazine. In acknowledging the presentation Mr. Potts said that Mr. Bolster's energy and goodwill in carrying it out had given him more satisfaction than anything else, and when the two eminent divines were photographed in the act of embracing on the platform there was hardly a dry eye in the huge audience, numbering fully forty persons, who attended the proceedings.

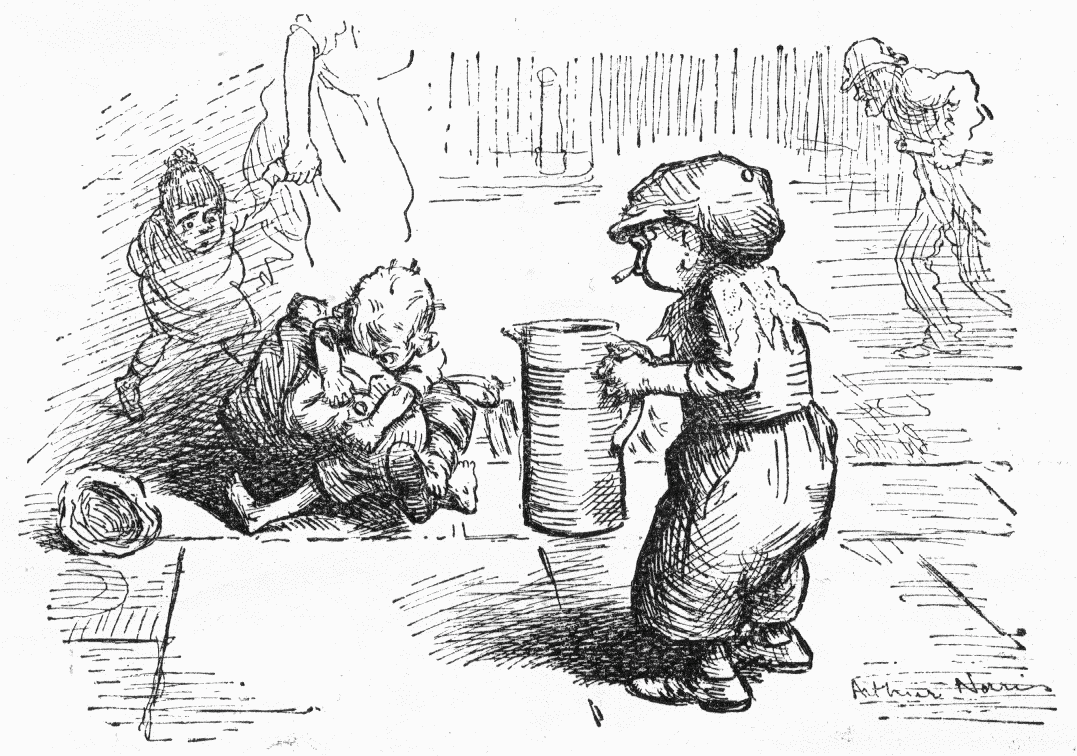

Turkey (to Europa, ring-mistress). "INFIRM OF PURPOSE! GIVE ME BACK THE WHIP."

Sympathetic Friend (to gloomy batsman, disgusted at being given out for a catch at the wicket). "Wot's wrong, Bill? Was it dahtful?"

Batsman. "Dahtful! I should think it was dahtful! I could 'ardly 'ear it myself."

A farmer once, to scare the birds away,

O'er his poor seeds set up, to leer and ogle,

A raffish moon-face, stuffed with straw and hay,

A Tattie-Bogle;

And rook and daw and stare their pinions spread

Incontinent; for, so they judged the matter,

Some scowling foe stood there, and off they fled

With startled chatter.

A week the portent stood in sun and rain

And fluttered rags of dread. A sparrow, nathless,

Whose nestlings cried, dashed down and snatched a grain,

And got off scathless.

Emboldened, back she flew; to such good end

The others followed, craning and alarmful,

To find the monster, if perhaps no friend,

At least unharmful.

To-day the bogle wags, a thing of jest

And open scorn; the very pipits mock it;

A jenny wren, I'm told, has built her nest

In one torn pocket!

Heart of my heart, and so prove aught of awe

That darkens on your path; the buckram rogue'll

Stand, when you face him, but a ghost of straw—

A Tattie-Bogle!

[A] Scarecrow. Scots.

Exasperated Subscriber (having found six different numbers engaged). "Well, what numbers HAVE you got?"

Although the last race on the programme had yet to be run the railway station that adjoined the course was already packed to discomfort with the crowd of those who had left early in order to avoid each other. When the train that had been waiting drew alongside the platform there was a considerable bustle; but the individual whom (from his costume and general appearance) I will call the Complete Sportsman was nimble enough to secure a corner seat in a compartment that was immediately filled. A couple of quiet-looking elderly men, wearing hard hats and field-glasses, took the cornerson the far side and began to discuss the day's events in undertones. They were followed by a stout red-faced gentleman in a suit of pronounced check, a curate (at sight of whom the Complete Sportsman elevated his eyebrows) and a hatchet-nosed individual in gaiters who looked like a vet.

As the train started, Red-face, catching the eye of the Complete Sportsman, smiled genially. "Nice bit o' sport to-day, guv'nor," he observed.

The person thus addressed agreed, a little nervously.

"And why shouldn't we keep it up?" continued the other. He gazed round upon the company at large. "If so be as no gentleman here has any objection to winning a bit more."

Since no one offered any protest it appeared that no such prejudice existed. Red-face, diving into the pocket of his check coat, produced cards and a folding board. "Then here goes!" said he. "Who's the Lady and Find the Woman. Half-a-quid on it every time against any gent as chooses to back his fancy!"

With an air of benevolent detachment he began to shuffle three of the cards face downwards upon the board. Still no one appeared willing to tempt fortune. The two quiet men in the far corner, after a hasty and somewhat contemptuous glance at Red-face's proceedings, had resumed their talk and took no further heed of him.

The cards, fell, slid, were turned up and slid again under his nimble lingers. "In the centre—and there she is!"—showing the queen. "Now on the left, quite correct. Once more, this time on the ri—no, Sir, as you say, left again. Pity for you we weren't betting on that round!"

This was to the hatchet-nosed man who (as though involuntarily) had pointed out an obvious defect in the manipulations. Seeming to be encouraged by this initial success, he bent forward with sudden interest. "Don't mind if I do have half-a-quid on it just once," he said.

It certainly seemed as though the Red-faced man must be actuated by motives of philanthropy. Quite a considerable number of times did Hatchet-nose back his fancy, and almost always with success. The result was that perhaps ten or a dozen sovereigns were transferred to his pockets from those of the bank. Even the curate was spurred by the sight into taking a part—though he was only fortunate enough to find the queen on three occasions out of five.

It was apparently this last circumstance, and the ease with which he himself could have pointed out the errors of the reverend gentleman, that finally overcame the reluctance of the Complete Sportsman. He blushed, hesitated, then began to feel in his waistcoat pocket.

"It looks easy enough," he ventured dubiously.

"Easy as winkin'," said the red-faced man. "At least to the gents' in this carriage. Begin to wish I hadn't proposed it."

However, he didn't show any signs of abandoning his amiable pursuit; not even when the Complete Sportsman, having assiduously searched all his pockets, produced a leather wallet and extracted thence a couple of notes.

"I'm afraid that I haven't got any change," he said in rather a disappointed tone.

"Perhaps," suggested the card-manipulator, "this gentleman could oblige you."

It being obvious that Hatchet-nose, the gentleman in question, was fully able to do this out of his recent winnings, he had, of course, no excuse for hesitation. The two five-pound notes changed hands; and the Sportsman pocketed twenty half-sovereigns.

Then he turned towards the cards with alacrity. The quiet couple in the corner had not been wholly unmindful of these proceedings. The slightest glance of amused and derisory intelligence passed between them as the Complete Sportsman plunged into the game.

For the first two attempts he was successful. No sooner, however, did he settle to serious play, beaming with triumph at his good fortune, than it unaccountably deserted him. He lost the two half-sovereigns that he had just won, and then another and another; till in the event he found himself no less than four-pounds-ten out of pocket.

"I—I seem somehow to have lost the knack of it," he said, glancing round at the company with an air almost of apology.

Red-face was loud in his commiseration and encouragements to proceed. "Luck's bound to turn," he protested.

The Complete Sportsman, however, seemed to have had enough. No amount of persuasion could induce him to tempt fortune further, though, to do him justice, he appeared to take his rebuff in a philosophic spirit. Desisting at length from his good-humoured attempts, the proprietor of the cards and board replaced them in his pocket and lit a cigar.

"Ah, well, somebody's got to lose, I suppose," he said tolerantly, adding, as the train slackened speed, "By Jove, Vauxhall already! I get out here. So long, all!"

He was on the platform immediately. By a coincidence as surprising as pleasant it appeared that Hatchet-nose and the curate were also alighting. The three walked away together; and the Complete Sportsman was left to share with the quiet couple a compartment in which there was now ample room to stretch his fawn-coloured limbs.

He did so with a sigh of relief, leaning back and smiling gently to himself as the train glided forward upon its[Pg 427] final stage. His recent misfortune appeared to trouble him not at all; indeed, as Waterloo was approached, the smile grew if anything more pronounced. He might have been thinking about some subject that amused him greatly.

Presently, turning towards his companions, he found the gaze of both the quiet men fixed upon him with a look of somewhat derisive compassion. It was apparent that the ease with which the Sportsman had been tempted into parting with his money had excited at once their pity and their contempt. For a time he endured this regard in uneasy silence. Then, as the preliminary jar of the brakes heralded Waterloo, he spoke.

"I perceive, gentlemen," said he, "that you are apparently labouring under a delusion with regard to my part in the transactions that you have just witnessed."

"I was wondering," returned the first of the quiet men, "how anyone could in these days be gulled by so transparent a set of rogues."

"Your wonder is, as I have said, misplaced. With regard to the persons who lately left us, the word transparent is, if anything, an understatement. The curate, the horsey stranger and the red-faced man were, of course, discredited before Noah entered the Ark."

"And yet," said the quiet man, staring, "we have this moment seen them take good money from you!"

"That," answered the Complete Sportsman as he prepared to alight, "is precisely where you make your mistake. The notes for which you saw me obtain change from one of the confederates, and of which change I lost less than half, were themselves——"

He paused, startled by the alteration that had taken place in the demeanour of the quiet men, who had risen simultaneously. The train had now stopped, and, glancing hastily over his shoulder, he saw that Red-face and his companions, who must have continued their journey in another compartment, were now surrounding the door.

For the first time the smile of the Complete Sportsman betrayed uneasiness. "What—what does this mean?" he demanded.

"Merely," said the first of the quiet men blandly, "that your game is up. You uttered at least twenty of those notes on the course to-day, and we were bound to have you. My name is Inspector Pilling, of Scotland Yard, and these gentlemen are my colleagues. We are five to one, so I suggest that you come quietly."

To the curate he added, as they entered a waiting taxi, "You were quite right, George; the chance of that little score was a soft thing."

The comments of the Complete Sportsman are best omitted. We are not the author of Pygmalion.

Mistress. "Why, Mary, isn't this your Sunday afternoon out? Aren't you going for a walk this lovely day?"

Mary. "Please, 'M, I'd rather stay in. You see, most of the people out on a Sunday is couples, and I don't like to be conspicuous."

From the Great North of Scotland Railway's advertisement in The Aberdeen Daily Journal:—

"A train will leave Aberdeen at 7.30 p.m. for Aberdeen."

Thus enabling the cautious Aberdonian to improve his mind by travel at a minimum of expense.

I take it that every able-bodied man and woman in this country wants to write a play. Since the news first got about that Orlando What's-his-name made £50,000 out of The Crimson Sponge, there has been a feeling that only through the medium of the stage can literary art find its true expression. The successful playwright is indeed a man to be envied. Leaving aside for the moment the question of super-tax, the prizes which fall to his lot are worth striving for. He sees his name (correctly spelt) on 'buses which go to such different spots as Hammersmith and West Norwood, and his name (spelt incorrectly) beneath the photograph of somebody else in The Illustrated Butler. He is a welcome figure at the garden-parties of the elect, who are always ready to encourage him by accepting free seats for his play; actor-managers nod to him; editors allow him to contribute without charge to a symposium on the price of golf balls. In short he becomes a "prominent figure in London Society"—and, if he is not careful, somebody will say so.

But even the unsuccessful dramatist has his moments. I knew a young man who married somebody else's mother, and was allowed by her fourteen gardeners to amuse himself sometimes by rolling the tennis-court. It was an unsatisfying life; and when rash acquaintances asked him what he did he used to say that he was reading for the Bar. Now he says he is writing a play—and we look round the spacious lawns and terraces and marvel at the run his last one must have had.

However, I assume that you who read this are actually in need of the dibs. Your play must be not merely a good play but a successful one. How shall this success be achieved?

Frankly I cannot always say. If you came to me and said, "I am on the Stock Exchange, and bulls are going down," or up, or sideways, or whatever it might be; "there's no money to be made in the City nowadays, and I want to write a play instead. How shall I do it?"—well, I couldn't help you. But suppose you said, "I'm fond of writing; my people always say my letters home are good enough for Punch. I've got a little idea for a play about a man and a woman and another woman, and—but perhaps I'd better keep the plot a secret for the moment. Anyhow it's jolly exciting, and I can do the dialogue all right. The only thing is, I don't know anything about technique and stage-craft and the three unities and that sort of rot. Can you give me a few hints?" Suppose you spoke to me like this, then I could do something for you. "My dear Sir," I should reply (or Madam), "you have come to the right shop. Lend me your ear for a few weeks, and you shall learn just what stage-craft is." And I should begin with a short homily on

If you ever read your Shakspeare—and no dramatist should despise the works of another dramatist; he may always pick up something in them which may be useful for his next play—if you ever read your Shakspeare, it is possible that you have come across this passage:—

"Enter Hamlet.

Ham. To be, or not to be——"

And so on in the same vein for some thirty lines.

These few remarks are called a soliloquy, being addressed rather to the world in general than to any particular person on the stage. Now the object of this soliloquy is plain. The dramatist wished us to know the thoughts which were passing through Hamlet's mind, and it was the only way he could think of in which to do it. Of course a really good actor can often give a clue to the feelings of a character simply by facial expression. There are ways of shifting the eyebrows, distending the nostrils, and exploring the lower molars with the tongue by which it is possible to denote respectively Surprise, Defiance and Doubt. Indeed, irresolution being the keynote of Hamlet's soliloquy, a clever player could to some extent indicate the whole thirty lines by a silent working of the jaw. But at the same time it would be idle to deny that he would miss the finer shades of the poet's meaning. "The insolence of office, and the spurns"—to take only one line—would tax the most elastic face.

So the soliloquy came into being. We moderns, however, see the absurdity of it. In real life no one thinks aloud or in an empty room. The up-to-date dramatist must at all costs avoid this hall-mark of the old-fashioned play.

What, then, is to be done? If it be granted, first, that the thoughts of a certain character should be known to the audience, and, secondly, that soliloquy, or the habit of thinking aloud, is in opposition to modern stage technique, how shall a soliloquy be avoided without damage to the play?

Well, there are more ways than one; and now we come to what is meant by stage-craft. Stage-craft is the art of getting over these difficulties, and (if possible) getting over them in a showy manner, so that people will say, "How remarkable his stage-craft is for so young a writer," when otherwise they mightn't have noticed it at all. Thus, in this play we have been talking about, an easy way of avoiding Hamlet's soliloquy would be for Ophelia to speak first.

Oph. What are you thinking about, my lord?

Ham. I am wondering whether to be or not to be, whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer——

And so on, till you get to the end, when Ophelia might say, "Ah, yes," or something non-committal of that sort. This would be an easy way of doing it, but it would not be the best way, for the reason that it is too easy to call attention to itself. What you want is to make it clear that you are conveying Hamlet's thoughts to the audience in rather a clever manner.

That this can now be done we have to thank the well-known inventor of the telephone. (I forget his name.) The telephone has revolutionised the stage; with its aid you can convey anything you like across the footlights. In the old badly-made play it was frequently necessary for one of the characters to take the audience into his confidence. "Having disposed of my uncle's body," he would say to the stout lady in the third row of the stalls, "I now have leisure in which to search for the will. But first to lock the door lest I should be interrupted by Harold Wotnott." In the modern well-constructed play he simply rings up an imaginary confederate and tells him what he is going to do. Could anything be more natural?

Let us, to give an example of how this method works, go back again to the play we have been discussing.

Enter Hamlet. He walks quickly across the room to the telephone, and takes up the receiver impatiently.

Ham. Hallo! Hallo! I want double-nine—hal-lo! I want double-nine two—hal-lo! Double-nine two three, Elsinore ... Double-nine, yes ... Hallo, is that you, Horatio? Hamlet speaking. Er—to be or not to be, that is the question; whether 'tis nobler in the mind to suffer the slings and arrows—— What? No, Hamlet speaking. What? Aren't you Horatio? I want double-nine two three——sorry.... Is that you, exchange? You gave me double-five, I want double-nine ... Hallo, is that you, Horatio? Hamlet speaking. To be or not to be, that is the—— What? No, I said, To be or not to be ... No,

'be'—b-e. Yes, that's right. To be or not to be, that is the question; whether 'tis nobler——

And so on. You see how effective it is.

But there is still another way of avoiding the soliloquy, which is sometimes[Pg 429] used with good results. It is to let Hamlet, if that happens to be the name of your character, enter with a small dog, pet falcon, mongoose, tame bear or whatever animal is most in keeping with the part, and confide in this animal such sorrows, hopes or secret history as the audience has got to know. This has the additional advantage of putting the audience immediately in sympathy with your hero. "How sweet of him," all the ladies say, "to tell his little bantam about it!"

If you are not yet tired (as I am) of the Prince of Denmark, I will explain (for the last time) how a modern author might re-write his speech.

Enter Hamlet with his favourite boar-hound.

Ham. (to B.-H.) To be or not to be—ah, Fido, Fido! That is the question—eh, old Fido, boy? Whether 'tis nobler in—how now, a rat! Rats, Fido, fetch 'em—in the mind to suffer The slings and—down, Sir!—arrows—put it down! Arrows of—drop it, Fido; good old dog——

And so on. Which strikes me as rather sweet and natural.

A. A. M.The S.P.C.L.A. (Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Labour Agitators) has mooted a novel and, we consider, very far-seeing scheme. It is recognised now that a time must come when no State will be able to ship its undesirables to another country, for the simple reason that the available dumping grounds will gradually be exhausted or refuse to be dumping grounds any longer. That is where the S.P.C.L.A. comes in with its proposal, which is to charter or, if necessary, build a 50,000 ton liner as an ocean hotel for the unfortunate exiles. This leviathan will be coaled by lighters outside the three-miles limit and will ride the high seas for ever and a day. In the event of internal disturbances (in the hotel itself) another maritime hostelry will be chartered, until—who knows—someday we may witness the almost unthinkable anomaly of a Labour Fleet.

The kindly action of the N.L.E.S.R.O. (Navvies' League for the Encouragement of Spectators at Roadmending Operations) in providing deck chairs upon the pavement at a penny an hour is universally appreciated, and it is now no uncommon thing to see a navvy taking a holiday and egging on his sturdy comrades to greater efforts from a seat marked "Deadhead."

The S.P.S.K.K. (Society for the Promotion of Steam-heating in Kaffir Kraals) displayed a regrettable lack of judgment in choosing Christmas Day for the laying of its foundation pipe, Christmas being the South African midsummer.

The D.M.S.P.T.O.H. (Dyspeptic Millionaires' Society for the Promotion of Their Own Happiness) is in urgent need of funds.

At the unveiling of the statue to its founder by the S.I.D.R.I. (Society for Insisting on the Divine Right of Iconoclasts) it is understood that several conversions were effected through the conduct of a band of youthful enthusiasts who, faithful to their principles and unable to restrain their zeal for the cause, rushed at the newly-revealed masterpiece and smashed it to atoms.

The S.F.S. (Society for the Formation of Societies) and the S.F.S.F.S. (Society for the Formation of Societies for the Formation of Societies) are both doing splendid work.

Petty Officer of Patrol. "Hello, you. What's your ship?"

Sailor (returning from revelry). "'Ow long 'ave you been blind? It's wrote plain enough on my cap, ain't it?"

From a poster:—

"New King's Capital Invested by Rebels."

In something safe, we hope.

Notice in a gramophone shop window:—

"Just Suitable for the River."

New Proprietor of Public-house (that levies a fine for every swear-word). "'Ere, Bill, that's a penny you owe to the parson's swear-box."

Bill. "I'd better do what I done afore—put a 'arf-crown in and 'ave a season-ticket."

(A reflection on the recent Amateur Golf Championship at Sandwich suggested by a study of the illustrated papers.)

They swung with the accurate grace of the clockwork at Greenwich;

Their brassies unswervingly held to the line of the pegs;

Their chip-shots came down on the greens and mistook them for spinach,

And stopped like poached eggs;

Not theirs the desire for the sandpit, not theirs the inadequate legs.

Or if over they failed to lie moribund, dauntless the heroes

Stooped down to impossible putts for a half or a win,

Stooped down in voluminous knickers and all sorts of queer hose

And stuffed the ball in,

Like American packers of pig-meat, hard home to the floor of the tin.

These things I admired; but I wondered still more when the mighty,

The mystical thumpers of pills by the marge of the spray,

Having somehow offended Poseidon or else Aphrodite,

Got chucked from the fray,

Passed forth till they left Mr. Jenkins sole lord of the hazardous bay.

When the ultimate putt was holed out in each notable duel

How grandly they took it, remarking "I think (or I guess)

That the right man has conquered," not shouting that Fortune was cruel,

Not murmuring, "Bless!"

What a glory illumined their features when snapped by the popular Press!

Full glad is the face of the earth when the vineyards are laden;

Loud laughs with innumerous laughter in wreath upon wreath

The ocean at Blackpool or Margate; most blithely the maiden

Unfastens the sheath

Of her mouth like the bloom of a musk rose, when Fangol has furbished her teeth;

So fair was the smile of the sea-kings; so sweet was the look on

The faces of Hezlet and Ouimet and most of their peers

When they passed from the contest, a smile with a sort of a hook on,

Unclouded with tears;

It went slap through their cheeks down the fair-way and bunkered itself by their ears.

And if e'er in the future, cast down from the promise of Heaven,

Half-stymied by William, I grumble and groan at my fate

When he captures the hole (and the game) with a pretty bad 7,

Whilst my score is 8,

And I bubble with impotent anger, I seethe with tumultuous hate.

Let me think of my album of photos, whose title is "After,"

All cut from the dailies; it gives you most wonderful tips

For producing without any pressure the right kind of laughter;

It gives you the grips

And the stance of the teeth of the plus men, and how to get length from the lips.

"Hobbs lbw b Bold c Pearson."—Scotsman.

Pearson ought really to be told that you cannot catch a man off his pads.

Prime and War Minister. "AFRAID I'VE LET YOU IN FOR RATHER AN AWKWARD JOB WITH THIS AMENDING BILL."

Lord Crewe. "MY DEAR FELLOW, YOU'RE SO VERSATILE—WHY NOT SPEND THE REST OF THE RECESS MAKING YOURSELF A BARON OR A BISHOP? THEN YOU COULD TAKE IT ON INSTEAD OF ME."

House of Commons, Monday, May 25.—"Let the curtain ring down, Mr. Speaker, and the sooner the better. It is a farce, and I think a contemptible farce."

Thus Bonner Law—the farce being the Third Reading of the Home Rule Bill.

The curtain had risen on a thronged and excited House. Were it the custom at the T. R. Westminster to put out notice-boards one might have borne the legend dear to the heart of the manager, "Standing room Only." Even late-comers among the peers were fain to stand by the doorway opening on the Gallery, where earlier birds had found twigs on which to sit. Overflow of Commoners into the side galleries gave the last touch to stirring scene presented but twice or thrice in history of a Session.

Conjurer. "Ladies and gentlemen, I will now place this scroll in the hat, and in a few weeks I shall show you something—er—something which will surprise you."

A Voice. "You've got it up your sleeve."

Conjurer. "On the contrary, gentlemen." (Aside) "Wish to Heaven I had!"

Ordered business of sitting was the stage of the measure alluded to in phrase quoted from Leader of opposition. But, as was testified anew last Thursday, business in House of Commons does not always run through expected courses. In strained temper of the hour anything might happen, even a bout of fisticuffs. What actually did happen was that within space of hour and a-half from Speaker's taking the Chair, a period including the ordinary Question-hour, Home Rule Bill was read a third time and carried over to House of Lords through cheering crowd waiting in Central Lobby.

Speaker introduced soothing note by frank confession that, when on Thursday he invited Leader of Opposition to state whether he approved the outburst of disorder among his followers which prevented their authorised spokesman being heard, he "was betrayed into an expression he ought not to have used." Bonner Law "gratefully accepted the explanation," and eloquently extolled the character of the Speaker.

Speaker invited Premier to yield to insistent demand of Opposition and give further particulars with regard to the Amending Bill. The Premier, always ready to oblige, responded in a few luminous, courteous sentences, which did not add a syllable of information beyond what had been reiterated in previous references to subject. It was then that Bonner Law, with rare dramatic gesture, gave the command, "Ring down the curtain!" "It is the end of the Act, but not of the play," he added amid loud cheers from host behind him, reinforced this afternoon by arrival of recruits from North-East Derbyshire and Ipswich. "The final Act in the drama will be played not in the House of Commons, but in the country, and there, Sir, it will not be a farce."

"If the Bill becomes an Act it will be born with a rope round its neck."—Mr. William O'Brien.

Prime Minister, amid constant interruption from benches opposite, made short reply. Curtain about to fall as directed when William O'Brien hurried to front of stage. Reasonably expected that, having through forty years made strenuous fight for Home Rule, he was now about to sing a pæan suitable to eve of final victory. On the contrary what he wished to remark, and like the Heathen Chinee his language was plain, was that, "If the Bill becomes an Act it will be born with a rope round its neck."

Home Rule for Ireland all very well. But not Home Rule cum John Redmond and sine William O'Brien.

House listened with impatience to this tirade, calling again and again for the division. When it was taken it appeared that 351 voted for Third Reading and 274 against, a majority of 77. Redmondites leaped to their feet and wildly cheered. Ministerialists did not respond to enthusiastic outburst. They were dumbly glad that a measure wrangled over for three sessions was out of the way at last, leaving behind, it is true, the shadow of an Amending Bill.

Business done.—Both Houses adjourn for Whitsun recess. Commons resume 9th of June; Lords six days later.

From an advertising tailor's guarantee:—

"If the smallest hole appears after six months' wear, we will make another absolutely free."

It is a very kind offer, but we would always rather find somebody who would mend the first hole.

"It is an interesting fact that Mr. Gidney (Marlborough) went round the course in, approximately, 97, which is, we understand, a record for the Hungerford course, the bogey for which is 82."

Marlborough Times.

Somebody must have done it in more than this. Personally we are always good for a century.

When Mr. Walford Sploshington bought Hydra House we all hoped that beyond papering and painting, dabbing on a bit of plaster where it was needed, and grubbing the groundsel in the drive, he would allow it to remain in the state of old-world picturesqueness in which he had found it. We would not have objected even if he had decided on having water laid on; although this would be getting dangerously near our limit, as there was a dear old draw-well in the garden and one in the ripping old courtyard. We were justly proud of the fact of Hydra House being the finest and purest example of Tudor architecture in our corner of England. When I say "we" I mean the Weatherspoons, the Malcomson-Pagets, Gaddingham, and one or two others, and myself. It was as near to being a mansion as it is reasonable to expect a house to be without its being actually a mansion; and there was a romance in its very name that compelled our reverence. The first owner—the ancestor in a direct line of the gentleman who, because of the increased cost of petrol combined with the Undeveloped Land Tax, was obliged to sell it to Mr. Walford Sploshington, the highest bidder—was one of those fine fellows who in the spacious days of Elizabeth did so much towards making England what she is to-day, or rather what she was until the General Election of 1906. On one of his voyages of adventure he visited the Hydra Islands, in the Gulf of Ægina, where he became enamoured of the daughter of a vineyard proprietor. As she heartily reciprocated his affection, he married her, and, bringing her home to England, installed her as mistress of a brand-new home presented to him by a grateful Queen and country. Given a similar set of circumstances, ninety-nine out of any hundred newly-married men would have done as he did, and called it Hydra House.

But Mr. Walford Sploshington disappointed us. He did more: he grieved us; he insulted our instincts, sentimental and artistic, and he offended our eyes. He filled in the dear old wells. He mutilated the Tudor garden out of all semblance of a Tudor garden. He enlarged the windows and made bays of them. He painted a vivid green all the exposed timbering that is the characteristic feature of Tudor houses. In short, he did everything to outrage the decencies. He even carried his vandalisms out to the old gateway. There he erected two Corinthian columns, and spanned them with the roof of a pagoda. It was a surprise to us that he retained the ancient name of Hydra House. We had expected, even hoped, that he would change it to something ornate and vulgar, and so leave nothing to remind us of the old place of which we had all been so fond and proud. But one sunny morning a sign-painter began work on the Corinthian columns. Gaddingham and I did not, of course, stand to watch him; but, having occasion to pass the pagoda during the afternoon, I happened upon Sploshington himself, standing in the middle of the road, poising his head this way and that, and quite obviously lost in admiration of ten six-inch gilt letters, five on each column.

The five on the left-hand column made up the mystery word "Mydra." Those on the right constituted "Mouse." Of course, I got it right almost the moment I had passed. What I had taken to be an "M" in each word was merely a highly-ornamental "H" with its horizontal bar sagging in the centre with the weight of its grandeur. There had never been a name on the gate in the whole history of Hydra House, but we agreed that Sploshington felt that after all his vandalism no one would recognise the place unless he labelled it, and, of course, he was unequal to providing a plain, unassuming label.

Then Gaddingham and I took counsel together, and we decided that I should write a nice letter to Sploshington. This is what I wrote:—

Dear Sir,—I trust you will pardon the liberty I am taking in writing to you, but a friend of mine and I have made a small bet on a question which, as it happens, no one but you is in a position to decide. Passing your gate the other day, we were both struck by the beauty of the gilt stencilling on the column on either side, more especially by the chaste idea followed out in the ornamentation of the initial letters—the "H's." They are, as I am convinced you are aware, suggestive of the letter "M," and this it is that has led to the little difference between my friend and myself. I hold the opinion that this suggestion is intentional, and that in giving your instructions to the decorator's artist you had in mind the celebrated Mouse of Mydra. My friend, whose strong point, I regret to say, is not history, confessed, ignorance of this famous animal, and I had to enlighten him there and then by telling him how the sagacious little creature saved the life of the King of Mydra by nibbling at his ear while he slept one night, all unconscious of an outbreak of fire in the palace, thereby rousing him in time to enable him to make his escape. And how, in gratitude, the King decreed that every family in his realm should on every 1st of April—the date of the fire—receive three barley loaves, a Dutch cheese, and a stoop of ale; and every child be given a pink sugar-mouse. My friend, however, holds to the opinion that the resemblance of the "H" to an "M" is merely accidental. As we have both backed our fancy, as the saying is, to the extent of five shillings, we shall be grateful if you will settle the little dispute for us.

Yours faithfully,

F. Melrush.

We had no fear that Sploshington would know that Mydra and its king and its mouse were as apocryphal as Mrs. Harris; but his reply exceeded our wildest expectations. This is it:—

Dear Sir,—I am obliged by your letter, and am pleased to inform you that you have won your bet. The resemblance of the "H" to an "M" is not accidental, as I had the incident of the Mydra Mouse in my mind when giving my directions to the artist. It may perhaps be of further interest to you to know that on every 1st of April it is my intention to present every working-class family in this parish with three four-pound loaves, a Dutch cheese, and a gallon of six ale; and every child with a pink sugar-mouse.

Faithfully yours,

Walford Sploshington.

Little Girl (in disgrace, to Mother as she enters nursery.) "Do you love me, mummy?"

Mother. "Yes, darling."

Little Girl. "Do you love me very much?"

Mother. "Of course, darling."

Little Girl. "Well, I've frown my pudden under the table."

Dear Sir, I shall not write a line to-day,

Though many subjects merit my attention.

To take one instance only, there is May

(The month) at present in her last declension.

Lord, what a dance she leads us on her May-toes,

And spoils the beans and ruins the potatoes.

The gloomy gardener stands and counts the cost,

His once proud thoughts to sheer depression turning.

Darkly he marks the intempestive frost,

Though the laburnum still keeps on laburning,

And though the rose renews her ancient story

And bursts her bonds and blazes in her glory.

No, Sir, I shall not write a single line,

Not though the Tories storm with angry lips which

Salute the serried ranks of the combine

With shouts of "'journ, 'journ, 'journ" or howls for Ipswich.

These do not stir me, and I see, unheeding,

The Home Rule Bill receive its hundredth reading.

As for my dogs, at any other time—

One is a massive hound and three are particles—

They might provoke a stave or two of rhyme,

Or shine in prose and be described in articles.

But, if I owned the swift melodious Meynell,

To-day I would not write about my kennel.

The woes of butlers and the ways of cooks,

The contumely of wives, the scorn of daughters;

Golf, too, and tennis, or reviews of books;

Breezes and bees and trees and rippling waters,

All these are writable, but I, Sir, shun them—

Take thirty lines: I've been and gone and done them!

"A Banker's business," the cashier explained, "is to borrow money from one customer and lend it to another."

I smiled an innocent smile.

"To me, for instance," I suggested.

"No, not to you. The general state of your account does not warrant an overdraft."

I bowed respectfully and promised to be careful.

As a matter of fact it has been extremely difficult. They keep a little book which tells them exactly how much I have got left. At the end of last year it was 2s.6d. Until the beginning of this month I let it stand at that; then I grew restive and ordered a new cheque-book. The cashier's eyes glistened as he handed it over. "Thirty, I suppose," he said sarcastically. I thanked him and withdrew. Half-a-crown aside; balance nothing.

Yesterday I went in and wrote out a cheque. Meanwhile the cashier disappeared into the back regions. Perhaps he went to make sure how I stood, but I am certain he knew all the time. On his return the cheque was ready.

"I'm just off for a tour round the world," I said. "You might take care of this till I come back," and I handed him the cheque-book. Then I drew out two shillings and fivepence.

The Cost of Ennoblement.—A Lover of Art.—A Very Natural Inquiry.—The Oaks.—A Remarkable Old Master.—A Delicate Trial of Tact.—Old Books.—Mr. Kipling.

The Cost of Ennoblement.

Can you tell me what I should have to pay to become a marquis? My wifeThe market price of a marquisate at this moment is £150,000. A few questions are asked. It is not usual to make a commoner a marquis at one step. There are no Turkish marquisates, nor any yet in Albania, but as one never knows what that country may bring forth perhaps it would be wise to wait a little. America confers no titles of such importance as marquis, but a dental degree is not difficult to obtain at, say, Milwaukee. Tammany has its bosses, but that title carries with it no distinction for the wife.

A Lover of Art.

Can you tell me where the best choppers are to be obtained and what areThere are excellent chopper shops near Smithfield. Opinions differ as to the best pictures in the Tate Gallery, individual taste being a powerful factor in the making of a choice.

A Very Natural Enquiry.

Can you tell me where I can procure a book which instructs one how toWe do not know that one has yet been published, but doubtless many are in preparation. We advise you to write to the Revue King, Mr. Max Pemberton, who is always delighted to answer letters and is the soul of courtesy; or to Mr. Alfred Butt, who has plenty of time on his hands.

The Oaks.

Will you kindly give me some facts about the race called the Oaks? ItYour friend, I am told, is right. You must have been confusing oaks with acorns.

A Remarkable Old Master.

I have a picture which my friends tell me is either by Leonardo daFrom your description of your picture we imagine it to be one of those on which these two clever artists collaborated. It would, however, be wiser to take it to one of the experts than to bring it to a noisy and restless newspaper office. We recommend either Sir Sidney Colvin, Sir Charles Holroyd or Sir Claude Phillips. As a precaution against the negligible risk mentioned in the second part of your query we advise you, when submitting the picture to these gentlemen, to have it chained to your body.

A Delicate Trial of Tact.

The other day I had lunch with an uncle with whom I wish to be on theYour problem is a very interesting one and we should find it easier to answer if you had told us what you actually did. To rise suddenly, apparently for the purpose of flinging your arms round your uncle's neck in a spasm of affection, and at the same time to sweep from the table the bottle and both glasses seems to us the course which possesses most elements of tact. The circumstance that you were inspired by admiration and love would mitigate your uncle's wrath, and a new and sound bottle could quickly be obtained. We admit that the restaurant would remain unpunished; but then that is a restaurant's métier.

Old Books.

I have recently turned up in a loft the following books: "CompleteFourpence for the lot.

Mr. Kipling.

Kindly tell me if the Mr. Kipling who has been making such a splendidWe are making enquiries.

When Elizabeth presented me with my first safety razor we were both extremely hopeful about the future. She, fresh from the influence of a chemist's assistant, was convinced that breakfast would receive my attentions at more nearly its official hour; while I, reading folded eulogies that had nestled mid the dismembered parts of the razor itself, was looking forward to quite ten minutes extra in bed each morning.

Incidentally we were both disappointed.

For some time everything went well. And then the disused razor blades began to collect!

Now, one of the duties of our seventh housemaid (the seventh this year) was to light gas and things in the bedrooms when it became dark. And one evening, when she was groping about with her hands and snatching at things on the dressing-table in the hope of finding matches, she clutched a group of discarded razor-blades by mistake, strewed them and her blood over[Pg 437] Elizabeth's best blue carpet, and gave notice the next morning.

"Now, what is to be done?" said Elizabeth next day as she sat on the floor and massaged the blue Axminster. "No housemaid, and a bedroom carpet disguised as a third-rate murder clue."

"Either get a red carpet, or apply for your next housemaid to a Society for Destitute Aristocrats, blue blood guaranteed," I suggested.

Elizabeth left off massaging and gazed searchingly at the murder clue.

"All because you didn't throw away those wretched razor blades," she said. "Hughie, I hate you! Throw them away at once!"

"Unhate me first," I stipulated.

Elizabeth unhated me, ruffling my newly-made hair in the process.

It took but two strides to reach the dressing-table; it was the work of hardly one minute to collect that ever-growing herd of assertive "has beens," and then ... I began to wonder where I was going to throw them.

Where did one generally throw away things? Out of the window?

I turned my head away in horror. Who was I that I should shower razor blades on that passing archdeacon?

The waste-paper basket?

My housemaid's life was too valuable.

The dust-bin?

But there again the dustman might delve; the Employers' Liability Act is a tricky business and I am only insured against my own death—which always seems to me silly.

"Look here," I said, "it's not so easy to throw these things away as you appear to think. Where am I to throw them?"

Elizabeth opened her mouth to suggest places. Then she shut it again without speaking and became thoughtful.

"Yes," she admitted at length, "it is a little difficult. One can't even bury them in the garden in case they should damage the potatoes."

"There," I cried triumphantly—"they've floored you too!"

Elizabeth gathered together her pails and sponges and held out a hand to be helped up.

"Not at all," she said. "All you've got to do is to put them in a cardboard box and make them into a nice parcel, and I'll write a label."

"Now," she said, when she had finished attaching it, "let's take the dogs for a walk, just to the end of the road. This parcel contains things that are dangerous to the public welfare, doesn't it? Very well, then, I shall make sure that it's taken into safe custody by the nearest policeman."

"Look here, Elizabeth," I said firmly, "I'll have nothing to do with your silly ass tricks. If we draw blood from the police——"

"Oh, that'll be all right," she remarked cheerfully as we reached the end of the road. "We shan't wait to explain. Quick! There is a policeman coming! Here's the parcel. Put it down just at the bottom of the letter-box."

As I stooped with it, "He won't get hurt," said Elizabeth. "He'll open it too gingerly to cut himself. He'll think it's a bomb."

"Why?" said I.

And then first I saw the writing on the label. It said, Votes for Women.

"Ole Bill yonder's got a job. Thinks he's goin' to set the Thames on fire."

"Not 'im; 'e takes 'arf a box o' matches to light a Woodbine."

This has cheered Mr. Masterman up a good deal.

"He left to his eldest son to devolve as an heirloom his picture by Velasquez of a girl with a bird on her finger and a boy and a basket of limes and £500 to the Foundling Hospital."—Times.

No doubt the Hospital will be grateful for its three legacies.

As was anticipated by the promoters of the tercentenary celebration of the discovery of Logarithms, to be held next July, the application for tickets has been overwhelming. The Albert Hall, Olympia, and the White City, each of which in turn was selected for the place of meeting, have been successively abandoned as inadequate, and it has now been decided to roof in the whole of Hyde Park. Even with the huge amount of accommodation thus available it is feared that many millions will have to be turned away.

Excursion trains will be run from all parts, and the advanced bookings are already said to have eclipsed the record for the Cup Final.

The whole period of the celebration will be regarded as a public holiday, and the Stock Exchange will be closed.

Some idea of the entertaining character of the festival will be gathered from the following abstracts from the preliminary programme, a copy of which we have had the privilege of inspecting.

The ceremony will open to the strains of Sir Edwin Elgar's Logarithmic Symphony, composed specially for the occasion.

Among the papers to be read in the course of the proceedings we note:

"State-aided Logarithms," by Mr. Lloyd George.Mr. John Masefield will recite a poem, entitled "The Log of the Widow's Cruise."

An interesting contrast to the flood of eulogy will be supplied by Sir Almroth Wright, who, taking the view that the simplicity with which logarithms can be handled is leading the nation inevitably towards mental atrophy, will introduce the question, "The Logarithm: is it a Public Menace?"

The programme will conclude with a costume ball, at which everybody present will be disguised as a different logarithm.

I carefully searched through all my pockets for the third time.

"Smithers," I said, "I have lost my railway ticket."

"Not really?" replied Smithers, scarcely looking up from his newspaper. "Have another look."

I had another look. I looked in my hat-band, in the turned-up bottoms of my trousers, and in the hole in my handkerchief. "No," I said firmly, "it's gone!"

"Extraordinary thing!"

"I have no doubt," I continued, "that the railway company are in some way to blame for it, but for the moment I cannot quite fix the responsibility. Let us view the matter bravely. We are now within a few miles of our destination; in a short time we shall be asked to produce our tickets; what are we to do?"

"I shall give mine up."

"Smithers," I said; "there is a selfish callousness about your reply which I do not like. A crisis in the life of another evidently does not move you."

"You can, I presume, pay again?"

"No," I said, "I have an absurd prejudice against paying twice for the same thing; I inherit it from a great-aunt on my mother's side."

"Then you'd better explain to the ticket-collector."

"Explanations are a sign of mental and moral weakness."

"Well, I've nothing more to suggest. You'll have to pay again."

"I shall not pay again," I replied, taking the paper gently from him. "I am a man and an Englishman; and Englishmen are not to be intimidated."

"Do you think," I continued, "that you could hold the collector in conversation while I glide imperceptibly from the precincts of the station?"

"I'm perfectly sure I couldn't."

"I was afraid not," I said sadly; "that would require imagination, tact, pluck, adroitness, in all of which commodities, my dear Smithers——Well, no doubt it's a good thing nature doesn't mould us all alike."

"No doubt, else your handicap would not be 16, while mine is scratch."

"Golf is not life," I answered. "But I will tax your genius a little less. Could you for a few moments look like a director of the line, or a foreman shunter, or something of that sort?"

"I could try."

"Then," I said cheerfully, "we will bluff the collector—bluff him into believing we are that which we are not. Many people go through life like that. It is quite simple. All we have to do is to stroll up the station looking as much like commercial or mechanical despots as possible; give a kindly smile of condescension to the ticket-collector, make a casual remark about the working of the coupling rods, and pass out of the station."

"Yes," said Smithers.

"Is that all you have to say?"

"Yes," said Smithers.

"I see how it is," I said, taking my golf clubs out of the rack as the train pulled up. "You have no stomach for it; the spice of adventure it contains does not appeal to you. Well, so much for modern civilisation. I will go through alone with it; pray, if you wish, detach yourself from me until we are out of the station."

I sprang out and hurried up the platform; a servant of the company was in waiting.

"Tickets, please," he said coldly—unnecessarily coldly, I thought.

I smiled. "I am glad to see," I observed genially, "that on my line at any rate even the commander-in-chief cannot pass the sentries unchallenged. Your sense of duty shall not go unrewarded; let me have your card."

He stared at me stonily.

"Don't you recognise me?" I asked.

"Tickets, please," he repeated.

I have never seen a face so lacking in that gracious trustfulness which is at once the pride and the adornment of the normal ticket-collector. I think in his youth he must have committed a murder or robbed an orchard, for the shadow of a crime seemed to hang over him. I felt instinctively that he was not fit to play the part I had allotted to him.

I looked back. Smithers was pluckily doing up his bootlace several yards away; a tactless grin seemed to desolate his features. The grin decided me.

"Smithers," I called, "hurry up with the tickets; the inspector is waiting for them. Good day, inspector."

And I walked briskly from the station.

"One hundred and seventy started out, the number including the best of the English players and the entire American continent."

Montreal Gazette.

If this is so America was hardly worth discovering.

Long-suffering Vegetarian Lodger. "Don't trouble to cook the caterpillars in future, Mrs. Gedge. I never eat them."

The dry sticks, as it were, of The Bale Fire (Hutchinson) are not very cunningly laid, with the result that from a spectacular point of view the conflagration fizzles out rather tamely. But there are so many bright passages in the book and so many sympathetic sketches of characters that I cannot help wishing the Frasers (Hugh and Mrs.) had either written a longer story depending completely on the interplay of temperament, or else built more carefully on their melodramatic substructure. For though Captain Mayhune, the villain of the piece, is the proprietor of a gaming-hell and terrorises Lady Trague with a piece of blotting-paper on which may be read a portion of her letter to a young man whom she indiscreetly though innocently adores, nothing very serious comes of his machinations, and our interest in the book is mainly confined to the emotional relations between Sir Charles, a fussy elderly martinet, his too young wife, and Maisie, her seventeen-year-old step-daughter, who varies from deeper moods to those of a silly and self-willed child. Then there is Captain Mayhune himself, a man of good impulses and evil, in whom, somehow or other, though never without a struggle, the evil always triumphs. Other characters are rather jerkily introduced, amongst whom a family of good-natured and thoroughly "nice" Americans, who help to straighten things out and bring people to a better understanding, are most conspicuous. But that piece of blotting-paper! If I were a stationer and kept a circulating library, I think I should try to turn an honest penny by selling sand to my customers along with their packets of linen-wove and blue-black writing-fluid. "Simple, effective, and leaves no chance to the blackmailer."

It is pleasant to receive in this age of realism a novel that is frankly romantic. Miss Kaye-Smith in Three against the World (Chapman and Hall) colours up life with lavish brush. We have a returned convict who fiddles in the rain for the benefit of dancing village children; we have impresarios who stand at the doors of inns and hear him thus fiddling; an untidy heroine who speaks in gasps and gurglings; and a lover who goes to literary parties in London and therefore (the inference is implied by the author) falls in love with two ladies at once. Such a novel is refreshing after the mathematical accuracy with which clerks, barmaids and politicians are perpetually presented to us by our novelists, but I am not at all sure that Miss Kaye-Smith is wise in trusting our credulity too far. There was a day when one would have accompanied her Tramping Methodist anywhere, but of late years that promise has not been fulfilled, and her last novel is, I think, distinctly her poorest. I like her affection for Sussex, her catalogue of Sussex names, the fine colour of her descriptive work; but her story is on the present occasion too obviously arranged behind the scenes. One can see the author working again and again for the romantic moment, and scenes that should have convinced and wrung the reader's heart (always eager to be wrung) have in their appearance some suspicion of the paint and paste-pot of the cheaper drama. I hope[Pg 440] that Miss Kate-Smith will get back in her next book to her earlier strength and sincerity.

That Second Nature (Duckworth), which John Travers has in mind, is the innate sense of obligation which compels a gentleman to be a gentleman, whatever else he may be, in all that he does, says, thinks, eats, drinks and wears. The family of Westfield went back to times past remembering, and it came a little hard to the descendant of such a stock to have to choose his wife from among women who had done time or else to lose that legacy by the help of which alone he could hope to keep up the ancestral castle as a going concern. But so it was, by reason of the testamentary caprice of a spiteful uncle; and the position was not eased by the special condition for publicity, designed to bring it about that the family records, which began proudly in Doomsday Book, should conclude ignominiously in The Daily Mail. For Jim, always the gentleman, there was choice only between the devil of poverty or the deep sea of the Prisoners' Aid Society. He resorted to the latter (refusing Suffragettes), and came by Joan Murphy for wife who, with all her excellent capacity, was no lady. Manslaughter, however, may be a venial crime and physical beauty is a very saving grace, and, as these things all happened in the earliest chapters, I readily foresaw an ultimate end of the happiest nature and a solution of all difficulties worked out in defiance of the probabilities. A disappointed prophet is a captious critic and, the story turning out quite otherwise, I was very much on the alert for latent faults. Of these I found none. True, I did not altogether like Jim Westfield, but then I doubt if I was altogether meant to. Furthermore I give many extra marks to the author (as to whose sex, by the way, I have in my ignorance had moments of doubt) for moving the scene to India and thus giving substance and colour to a very remarkable love-story, while at the same time assisting his original theme with the subtle comparison, rather hinted at than dwelt upon, of caste.

Pot-Pourri Mixed by Two (Smith, Elder) is a book to live with, but not to be read at a sitting. After spending some hours with Mrs. C. W. Earle and Miss Ethel Case I found that my critical palate was unequal to the demands of so liberal and varied a banquet; and when I had finished a poem by Mr. Masefield, and found that it was followed by a recipe for cucumber soup, I wanted badly to laugh out loud. My advice, therefore, to readers is to take a snack from time to time, but not to make a square meal of it. While dissenting from some of Mrs. Earle's opinions—I do not, for instance, think that the paper she mentions is "the best of all evening papers"—there is no getting away from her sincerity or from a certain indefinable charm which prevents her from causing irritation even when she is proclaiming her very pronounced views. Miss Case, the other mixer, supplies some really valuable hints on gardens. These are drawn from her practical experience and are given succinctly enough. The only fault to be found with her is that in her efforts to be a pot-pourrist she occasionally finds it easier to mix than to blend. With each chapter we are furnished with various recipes which should, at any rate, gladden the heart of all vegetarians. Even I, whom Mrs. Earle possibly would think a heretic, am prepared to take my chance with salsify scallops, walnut pie and hominy cutlets.

The Magic Tale of Harvanger and Yolande (Mills and Boon) is set forth by a new scrivener, to wit, one G. P. Baker, in more than ordinarily flamboyant Wardour Street English. Harvanger, a Shepherd, hies forth on his Quest for the Best Thing in the World. It turneth out in sooth to be Love and Yolande. Perhaps Mr. Baker, an easy prey to the magic of jolly old words, has let himself do a little too much embroidery to the square inch of happening. There are indeed some good fights, though, by reason of this excess of embroidery, they are a little vague and difficult to follow. It is very well to have orgulous messires and men of courteoisie, with côtehardie of crocus or hose of purpure (showing how History repeateth herself), gearing and graithing for battle, mounted on coal-black destriers and generally behaving right this, that and the other withal; but when Yolande, asking Harvanger what will happen to her when he is away, receiveth for answer, "Truly I fear that thou wilt be very dull"; or when Bernlak, the fighter, says of a dead man, "I took over such effects as he left" (very much after the manner of my solicitor), one can't help feeling a little let down. Of such indeed are the perils of the Higher Tushery. They should not, however, be allowed to prejudice the consideration of a painstaking narrative which may well delight the confirmed romantic.

Mr. Laurence Kettle, as quoted by The Irish Volunteer and re-quoted by The Dublin Evening Mail (and they may share the glory between them):—

However, it is no good going to the Zoo to look for these in the Wolf House. Stay at home quietly and read "Maud" and "The Destruction of Sennacherib," and then you will understand how Milton would have plagiarised Tennyson and Byron in one line if he had only lived long enough.

"When Mr. Asquith came in he was greeted with Opposition shouts of 'Ipswich' and 'Where's Masterman?' Mr. Asquith said—The Government adhered to decision not to take part officially in Panama Exposition."—Star.

If Mr. Asquith wishes to be a success in the House he must improve his powers of repartee. At present his back-answers are entirely lacking in snap.

End of the Project Gutenberg EBook of Punch, or the London Charivari, Vol.

146, June 3, 1914, by Various

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK PUNCH ***

***** This file should be named 25676-h.htm or 25676-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/2/5/6/7/25676/

Produced by Neville Allen, Malcolm Farmer and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions

will be renamed.

Creating the works from public domain print editions means that no

one owns a United States copyright in these works, so the Foundation

(and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United States without

permission and without paying copyright royalties. Special rules,

set forth in the General Terms of Use part of this license, apply to

copying and distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works to

protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm concept and trademark. Project

Gutenberg is a registered trademark, and may not be used if you

charge for the eBooks, unless you receive specific permission. If you

do not charge anything for copies of this eBook, complying with the

rules is very easy. You may use this eBook for nearly any purpose

such as creation of derivative works, reports, performances and

research. They may be modified and printed and given away--you may do

practically ANYTHING with public domain eBooks. Redistribution is

subject to the trademark license, especially commercial

redistribution.

*** START: FULL LICENSE ***

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full Project

Gutenberg-tm License (available with this file or online at

http://gutenberg.org/license).

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or destroy

all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your possession.

If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound by the

terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the person or

entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph 1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this agreement

and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm electronic

works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the Foundation"

or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection of Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual works in the

collection are in the public domain in the United States. If an

individual work is in the public domain in the United States and you are

located in the United States, we do not claim a right to prevent you from

copying, distributing, performing, displaying or creating derivative

works based on the work as long as all references to Project Gutenberg

are removed. Of course, we hope that you will support the Project

Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting free access to electronic works by