| Next Part | Main Index |

CHAPTER I.

The Party—Across America to Vancouver—On Board the Warrimo—Steamer Chairs—The Captain—Going Home under a Cloud—A Gritty Purser—The Brightest Passenger—Remedy for Bad Habits—The Doctor and the Lumbago—A Moral Pauper—Limited Smoking—Remittance-men.

CHAPTER II.

Change of Costume—Fish, Snake, and Boomerang Stories—Tests of Memory—A Brahmin Expert—General Grant's Memory—A Delicately Improper Tale

CHAPTER III.

Honolulu—Reminiscences of the Sandwich Islands—King Liholiho and His Royal Equipment—The Tabu—The Population of the Island—A Kanaka Diver—Cholera at Honolulu—Honolulu; Past and Present—The Leper Colony

CHAPTER IV.

Leaving Honolulu—Flying-fish—Approaching the Equator—Why the Ship Went Slow—The Front Yard of the Ship—Crossing the Equator—Horse Billiards or Shovel Board—The Waterbury Watch—Washing Decks—Ship Painters—The Great Meridian—The Loss of a Day—A Babe without a Birthday

CHAPTER V.

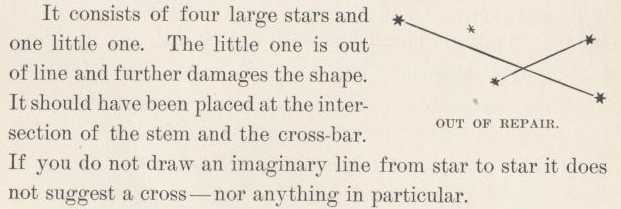

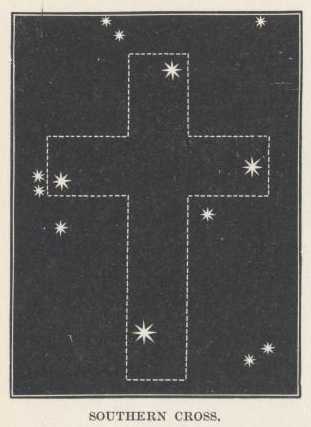

A lesson in Pronunciation—Reverence for Robert Burns—The Southern Cross—Troublesome Constellations—Victoria for a Name—Islands on the Map—Alofa and Fortuna—Recruiting for the Queensland Plantations—Captain Warren's NoteBook—Recruiting not thoroughly Popular

CHAPTER VI.

Missionaries Obstruct Business—The Sugar Planter and the Kanaka—The Planter's View—Civilizing the Kanaka—The Missionary's View—The Result—Repentant Kanakas—Wrinkles—The Death Rate in Queensland

CHAPTER VII.

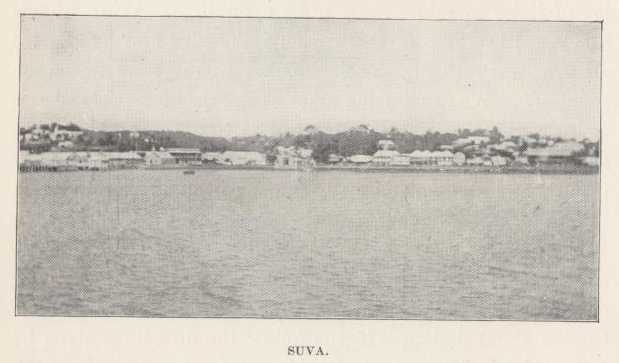

The Fiji Islands—Suva—The Ship from Duluth—Going Ashore—Midwinter in Fiji—Seeing the Governor—Why Fiji was Ceded to England—Old time Fijians—Convicts among the Fijians—A Case Where Marriage was a Failure—Immortality with Limitations

CHAPTER VIII.

A Wilderness of Islands—Two Men without a Country—A Naturalist from New Zealand—The Fauna of Australasia—Animals, Insects, and Birds—The Ornithorhynchus—Poetry and Plagiarism

A man may have no bad habits and have worse.

The starting point of this lecturing-trip around the world was Paris, where we had been living a year or two.

We sailed for America, and there made certain preparations. This took but little time. Two members of my family elected to go with me. Also a carbuncle. The dictionary says a carbuncle is a kind of jewel. Humor is out of place in a dictionary.

We started westward from New York in midsummer, with Major Pond to manage the platform-business as far as the Pacific. It was warm work, all the way, and the last fortnight of it was suffocatingly smoky, for in Oregon and British Columbia the forest fires were raging. We had an added week of smoke at the seaboard, where we were obliged to wait awhile for our ship. She had been getting herself ashore in the smoke, and she had to be docked and repaired.

We sailed at last; and so ended a snail-paced march across the continent, which had lasted forty days.

We moved westward about mid-afternoon over a rippled and sparkling summer sea; an

enticing sea, a clean and cool sea, and apparently a welcome sea to all

on board; it certainly was to me, after the distressful dustings and smokings and

swelterings of the past weeks. The voyage would furnish a three-weeks

holiday, with hardly a break in it. We had the whole Pacific Ocean in

front of us, with nothing to do but do nothing and be comfortable. The

city of Victoria was twinkling dim in the deep heart of her smoke-cloud,

and getting ready to vanish and now we closed the field-glasses and sat

down on our steamer chairs contented and at peace. But they went to

wreck and ruin under us and brought us to shame before all the

passengers. They had been furnished by the largest furniture-dealing

house in Victoria, and were worth a couple of farthings a dozen, though

they had cost us the price of honest chairs. In the Pacific and Indian

Oceans one must still bring his own deck-chair on board or go without,

just as in the old forgotten Atlantic times—those Dark Ages of sea

travel.

Ours was a reasonably comfortable ship, with the customary sea-going fare—plenty of good food furnished by the Deity and cooked by the devil. The discipline observable on board was perhaps as good as it is anywhere in the Pacific and Indian Oceans. The ship was not very well arranged for tropical service; but that is nothing, for this is the rule for ships which ply in the tropics. She had an over-supply of cockroaches, but this is also the rule with ships doing business in the summer seas—at least such as have been long in service. Our young captain was a very handsome man, tall and perfectly formed, the very figure to show up a smart uniform's finest effects. He was a man of the best intentions and was polite and courteous even to courtliness. There was a soft and grace and finish about his manners which made whatever place he happened to be in seem for the moment a drawing room. He avoided the smoking room. He had no vices. He did not smoke or chew tobacco or take snuff; he did not swear, or use slang or rude, or coarse, or indelicate language, or make puns, or tell anecdotes, or laugh intemperately, or raise his voice above the moderate pitch enjoined by the canons of good form. When he gave an order, his manner modified it into a request. After dinner he and his officers joined the ladies and gentlemen in the ladies' saloon, and shared in the singing and piano playing, and helped turn the music. He had a sweet and sympathetic tenor voice, and used it with taste and effect. After the music he played whist there, always with the same partner and opponents, until the ladies' bedtime. The electric lights burned there as late as the ladies and their friends might desire; but they were not allowed to burn in the smoking-room after eleven. There were many laws on the ship's statute book of course; but so far as I could see, this and one other were the only ones that were rigidly enforced. The captain explained that he enforced this one because his own cabin adjoined the smoking-room, and the smell of tobacco smoke made him sick. I did not see how our smoke could reach him, for the smoking-room and his cabin were on the upper deck, targets for all the winds that blew; and besides there was no crack of communication between them, no opening of any sort in the solid intervening bulkhead. Still, to a delicate stomach even imaginary smoke can convey damage.

The captain, with his gentle nature, his polish, his sweetness, his moral and verbal purity, seemed pathetically out of place in his rude and autocratic vocation. It seemed another instance of the irony of fate.

He was going home under a cloud. The passengers knew about his trouble, and were sorry for him. Approaching Vancouver through a narrow and difficult passage densely befogged with smoke from the forest fires, he had had the ill-luck to lose his bearings and get his ship on the rocks. A matter like this would rank merely as an error with you and me; it ranks as a crime with the directors of steamship companies. The captain had been tried by the Admiralty Court at Vancouver, and its verdict had acquitted him of blame. But that was insufficient comfort. A sterner court would examine the case in Sydney—the Court of Directors, the lords of a company in whose ships the captain had served as mate a number of years. This was his first voyage as captain.

The officers of our ship were hearty and companionable young men, and they entered into the general amusements and helped the passengers pass the time. Voyages in the Pacific and Indian Oceans are but pleasure excursions for all hands. Our purser was a young Scotchman who was equipped with a grit that was remarkable. He was an invalid, and looked it, as far as his body was concerned, but illness could not subdue his spirit. He was full of life, and had a gay and capable tongue. To all appearances he was a sick man without being aware of it, for he did not talk about his ailments, and his bearing and conduct were those of a person in robust health; yet he was the prey, at intervals, of ghastly sieges of pain in his heart. These lasted many hours, and while the attack continued he could neither sit nor lie. In one instance he stood on his feet twenty-four hours fighting for his life with these sharp agonies, and yet was as full of life and cheer and activity the next day as if nothing had happened.

The brightest passenger in the ship, and the most interesting and felicitous talker, was a young Canadian who was not able to let the whisky bottle alone. He was of a rich and powerful family, and could have had a distinguished career and abundance of effective help toward it if he could have conquered his appetite for drink; but he could not do it, so his great equipment of talent was of no use to him. He had often taken the pledge to drink no more, and was a good sample of what that sort of unwisdom can do for a man—for a man with anything short of an iron will. The system is wrong in two ways: it does not strike at the root of the trouble, for one thing, and to make a pledge of any kind is to declare war against nature; for a pledge is a chain that is always clanking and reminding the wearer of it that he is not a free man.

I have said that the system does not strike at the root of the trouble, and I venture to repeat that. The root is not the drinking, but the desire to drink. These are very different things. The one merely requires will—and a great deal of it, both as to bulk and staying capacity—the other merely requires watchfulness—and for no long time. The desire of course precedes the act, and should have one's first attention; it can do but little good to refuse the act over and over again, always leaving the desire unmolested, unconquered; the desire will continue to assert itself, and will be almost sure to win in the long run. When the desire intrudes, it should be at once banished out of the mind. One should be on the watch for it all the time—otherwise it will get in. It must be taken in time and not allowed to get a lodgment. A desire constantly repulsed for a fortnight should die, then. That should cure the drinking habit. The system of refusing the mere act of drinking, and leaving the desire in full force, is unintelligent war tactics, it seems to me. I used to take pledges—and soon violate them. My will was not strong, and I could not help it. And then, to be tied in any way naturally irks an otherwise free person and makes him chafe in his bonds and want to get his liberty. But when I finally ceased from taking definite pledges, and merely resolved that I would kill an injurious desire, but leave myself free to resume the desire and the habit whenever I should choose to do so, I had no more trouble. In five days I drove out the desire to smoke and was not obliged to keep watch after that; and I never experienced any strong desire to smoke again. At the end of a year and a quarter of idleness I began to write a book, and presently found that the pen was strangely reluctant to go. I tried a smoke to see if that would help me out of the difficulty. It did. I smoked eight or ten cigars and as many pipes a day for five months; finished the book, and did not smoke again until a year had gone by and another book had to be begun.

I can quit any of my nineteen injurious habits at any time, and without discomfort or inconvenience. I think that the Dr. Tanners and those others who go forty days without eating do it by resolutely keeping out the desire to eat, in the beginning, and that after a few hours the desire is discouraged and comes no more.

Once I tried my scheme in a large medical way. I had been confined to my bed several days with lumbago. My case refused to improve. Finally the doctor said,—

"My remedies have no fair chance. Consider what they have to fight, besides the lumbago. You smoke extravagantly, don't you?"

"Yes."

"You take coffee immoderately?"

"Yes."

"And some tea?"

"Yes."

"You eat all kinds of things that are dissatisfied with each other's company?"

"Yes."

"You drink two hot Scotches every night?"

"Yes."

"Very well, there you see what I have to contend against. We can't make progress the way the matter stands. You must make a reduction in these things; you must cut down your consumption of them considerably for some days."

"I can't, doctor."

"Why can't you."

"I lack the will-power. I can cut them off entirely, but I can't merely moderate them."

He said that that would answer, and said he would come around in twenty-four hours and begin work again. He was taken ill himself and could not come; but I did not need him. I cut off all those things for two days and nights; in fact, I cut off all kinds of food, too, and all drinks except water, and at the end of the forty-eight hours the lumbago was discouraged and left me. I was a well man; so I gave thanks and took to those delicacies again.

It seemed a valuable medical course, and I recommended it to a lady. She had run down and down and down, and had at last reached a point where medicines no longer had any helpful effect upon her. I said I knew I could put her upon her feet in a week. It brightened her up, it filled her with hope, and she said she would do everything I told her to do. So I said she must stop swearing and drinking, and smoking and eating for four days, and then she would be all right again. And it would have happened just so, I know it; but she said she could not stop swearing, and smoking, and drinking, because she had never done those things. So there it was. She had neglected her habits, and hadn't any. Now that they would have come good, there were none in stock. She had nothing to fall back on. She was a sinking vessel, with no freight in her to throw overbpard and lighten ship withal. Why, even one or two little bad habits could have saved her, but she was just a moral pauper. When she could have acquired them she was dissuaded by her parents, who were ignorant people though reared in the best society, and it was too late to begin now. It seemed such a pity; but there was no help for it. These things ought to be attended to while a person is young; otherwise, when age and disease come, there is nothing effectual to fight them with.

When I was a youth I used to take all kinds of pledges, and do my best to

keep them, but I never could, because I didn't strike at the root of the

habit—the desire; I generally broke down within the month. Once I tried

limiting a habit. That worked tolerably well for a while. I pledged

myself to smoke but one cigar a day. I kept the cigar waiting until

bedtime, then I had a luxurious time with it. But desire persecuted me

every day and all day long; so, within the week I found myself hunting

for larger cigars than I had been used to smoke; then larger ones still,

and still larger ones. Within the fortnight I was getting cigars made

for me—on a yet larger pattern. They still grew and grew in size.

Within the month my cigar had grown to such proportions that I could have

used it as a crutch. It now seemed to me that a one-cigar limit was no

real protection to a person, so I knocked my pledge on the head and

resumed my liberty.

To go back to that young Canadian. He was a "remittance man," the first one I had ever seen or heard of. Passengers explained the term to me. They said that dissipated ne'er-do-wells belonging to important families in England and Canada were not cast off by their people while there was any hope of reforming them, but when that last hope perished at last, the ne'er-do-well was sent abroad to get him out of the way. He was shipped off with just enough money in his pocket—no, in the purser's pocket—for the needs of the voyage—and when he reached his destined port he would find a remittance awaiting him there. Not a large one, but just enough to keep him a month. A similar remittance would come monthly thereafter. It was the remittance-man's custom to pay his month's board and lodging straightway—a duty which his landlord did not allow him to forget—then spree away the rest of his money in a single night, then brood and mope and grieve in idleness till the next remittance came. It is a pathetic life.

We had other remittance-men on board, it was said. At least they said

they were R. M.'s. There were two. But they did not resemble the

Canadian; they lacked his tidiness, and his brains, and his gentlemanly

ways, and his resolute spirit, and his humanities and generosities. One

of them was a lad of nineteen or twenty, and he was a good deal of a

ruin, as to clothes, and morals, and general aspect. He said he was a

scion of a ducal house in England, and had been shipped to Canada for the

house's relief, that he had fallen into trouble there, and was now being

shipped to Australia. He said he had no title. Beyond this remark he

was economical of the truth. The first thing he did in Australia was to

get into the lockup, and the next thing he did was to proclaim himself an

earl in the police court in the morning and fail to prove it.

When in doubt, tell the truth.

About four days out from Victoria we plunged into hot weather, and all the male passengers put on white linen clothes. One or two days later we crossed the 25th parallel of north latitude, and then, by order, the officers of the ship laid away their blue uniforms and came out in white linen ones. All the ladies were in white by this time. This prevalence of snowy costumes gave the promenade deck an invitingly cool, and cheerful and picnicky aspect.

From my diary:

There are several sorts of ills in the world from which a person can never escape altogether, let him journey as far as he will. One escapes from one breed of an ill only to encounter another breed of it. We have come far from the snake liar and the fish liar, and there was rest and peace in the thought; but now we have reached the realm of the boomerang liar, and sorrow is with us once more. The first officer has seen a man try to escape from his enemy by getting behind a tree; but the enemy sent his boomerang sailing into the sky far above and beyond the tree; then it turned, descended, and killed the man. The Australian passenger has seen this thing done to two men, behind two trees—and by the one arrow. This being received with a large silence that suggested doubt, he buttressed it with the statement that his brother once saw the boomerang kill a bird away off a hundred yards and bring it to the thrower. But these are ills which must be borne. There is no other way.

The talk passed from the boomerang to dreams—usually a fruitful subject, afloat or ashore—but this time the output was poor. Then it passed to instances of extraordinary memory—with better results. Blind Tom, the negro pianist, was spoken of, and it was said that he could accurately play any piece of music, howsoever long and difficult, after hearing it once; and that six months later he could accurately play it again, without having touched it in the interval. One of the most striking of the stories told was furnished by a gentleman who had served on the staff of the Viceroy of India. He read the details from his note-book, and explained that he had written them down, right after the consummation of the incident which they described, because he thought that if he did not put them down in black and white he might presently come to think he had dreamed them or invented them.

The Viceroy was making a progress, and among the shows offered by the Maharajah of Mysore for his entertainment was a memory-exhibition. The Viceroy and thirty gentlemen of his suite sat in a row, and the memory-expert, a high-caste Brahmin, was brought in and seated on the floor in front of them. He said he knew but two languages, the English and his own, but would not exclude any foreign tongue from the tests to be applied to his memory. Then he laid before the assemblage his program—a sufficiently extraordinary one. He proposed that one gentleman should give him one word of a foreign sentence, and tell him its place in the sentence. He was furnished with the French word 'est', and was told it was second in a sentence of three words. The next gentleman gave him the German word 'verloren' and said it was the third in a sentence of four words. He asked the next gentleman for one detail in a sum in addition; another for one detail in a sum of subtraction; others for single details in mathematical problems of various kinds; he got them. Intermediates gave him single words from sentences in Greek, Latin, Spanish, Portuguese, Italian, and other languages, and told him their places in the sentences. When at last everybody had furnished him a single rag from a foreign sentence or a figure from a problem, he went over the ground again, and got a second word and a second figure and was told their places in the sentences and the sums; and so on and so on. He went over the ground again and again until he had collected all the parts of the sums and all the parts of the sentences—and all in disorder, of course, not in their proper rotation. This had occupied two hours.

The Brahmin now sat silent and thinking, a while, then began and repeated all the sentences, placing the words in their proper order, and untangled the disordered arithmetical problems and gave accurate answers to them all.

In the beginning he had asked the company to throw almonds at him during the two hours, he to remember how many each gentleman had thrown; but none were thrown, for the Viceroy said that the test would be a sufficiently severe strain without adding that burden to it.

General Grant had a fine memory for all kinds of things, including even names and faces, and I could have furnished an instance of it if I had thought of it. The first time I ever saw him was early in his first term as President. I had just arrived in Washington from the Pacific coast, a stranger and wholly unknown to the public, and was passing the White House one morning when I met a friend, a Senator from Nevada. He asked me if I would like to see the President. I said I should be very glad; so we entered. I supposed that the President would be in the midst of a crowd, and that I could look at him in peace and security from a distance, as another stray cat might look at another king. But it was in the morning, and the Senator was using a privilege of his office which I had not heard of—the privilege of intruding upon the Chief Magistrate's working hours. Before I knew it, the Senator and I were in the presence, and there was none there but we three. General Grant got slowly up from his table, put his pen down, and stood before me with the iron expression of a man who had not smiled for seven years, and was not intending to smile for another seven. He looked me steadily in the eyes—mine lost confidence and fell. I had never confronted a great man before, and was in a miserable state of funk and inefficiency. The Senator said:—

"Mr. President, may I have the privilege of introducing Mr. Clemens?"

The President gave my hand an unsympathetic wag and dropped it. He did not say a word but just stood. In my trouble I could not think of anything to say, I merely wanted to resign. There was an awkward pause, a dreary pause, a horrible pause. Then I thought of something, and looked up into that unyielding face, and said timidly:—

"Mr. President, I—I am embarrassed. Are you?"

His face broke—just a little—a wee glimmer, the momentary flicker of a summer-lightning smile, seven years ahead of time—and I was out and gone as soon as it was.

Ten years passed away before I saw him the second time. Meantime I was become better known; and was one of the people appointed to respond to toasts at the banquet given to General Grant in Chicago—by the Army of the Tennessee when he came back from his tour around the world. I arrived late at night and got up late in the morning. All the corridors of the hotel were crowded with people waiting to get a glimpse of General Grant when he should pass to the place whence he was to review the great procession. I worked my way by the suite of packed drawing-rooms, and at the corner of the house I found a window open where there was a roomy platform decorated with flags, and carpeted. I stepped out on it, and saw below me millions of people blocking all the streets, and other millions caked together in all the windows and on all the house-tops around. These masses took me for General Grant, and broke into volcanic explosions and cheers; but it was a good place to see the procession, and I stayed. Presently I heard the distant blare of military music, and far up the street I saw the procession come in sight, cleaving its way through the huzzaing multitudes, with Sheridan, the most martial figure of the War, riding at its head in the dress uniform of a Lieutenant-General.

And now General Grant, arm-in-arm with Major Carter Harrison, stepped out on the platform, followed two and two by the badged and uniformed reception committee. General Grant was looking exactly as he had looked upon that trying occasion of ten years before—all iron and bronze self-possession. Mr. Harrison came over and led me to the General and formally introduced me. Before I could put together the proper remark, General Grant said—

"Mr. Clemens, I am not embarrassed. Are you?"—and that little seven-year smile twinkled across his face again.

Seventeen years have gone by since then, and to-day, in New York, the streets are a crush of people who are there to honor the remains of the great soldier as they pass to their final resting-place under the monument; and the air is heavy with dirges and the boom of artillery, and all the millions of America are thinking of the man who restored the Union and the flag, and gave to democratic government a new lease of life, and, as we may hope and do believe, a permanent place among the beneficent institutions of men.

We had one game in the ship which was a good time-passer—at least it was at night in the smoking-room when the men were getting freshened up from the day's monotonies and dullnesses. It was the completing of non-complete stories. That is to say, a man would tell all of a story except the finish, then the others would try to supply the ending out of their own invention. When every one who wanted a chance had had it, the man who had introduced the story would give it its original ending—then you could take your choice. Sometimes the new endings turned out to be better than the old one. But the story which called out the most persistent and determined and ambitious effort was one which had no ending, and so there was nothing to compare the new-made endings with. The man who told it said he could furnish the particulars up to a certain point only, because that was as much of the tale as he knew. He had read it in a volume of sketches twenty-five years ago, and was interrupted before the end was reached. He would give any one fifty dollars who would finish the story to the satisfaction of a jury to be appointed by ourselves. We appointed a jury and wrestled with the tale. We invented plenty of endings, but the jury voted them all down. The jury was right. It was a tale which the author of it may possibly have completed satisfactorily, and if he really had that good fortune I would like to know what the ending was. Any ordinary man will find that the story's strength is in its middle, and that there is apparently no way to transfer it to the close, where of course it ought to be. In substance the storiette was as follows:

John Brown, aged thirty-one, good, gentle, bashful, timid, lived in a quiet village in Missouri. He was superintendent of the Presbyterian Sunday-school. It was but a humble distinction; still, it was his only official one, and he was modestly proud of it and was devoted to its work and its interests. The extreme kindliness of his nature was recognized by all; in fact, people said that he was made entirely out of good impulses and bashfulness; that he could always be counted upon for help when it was needed, and for bashfulness both when it was needed and when it wasn't.

Mary Taylor, twenty-three, modest, sweet, winning, and in character and person beautiful, was all in all to him. And he was very nearly all in all to her. She was wavering, his hopes were high. Her mother had been in opposition from the first. But she was wavering, too; he could see it. She was being touched by his warm interest in her two charity-proteges and by his contributions toward their support. These were two forlorn and aged sisters who lived in a log hut in a lonely place up a cross road four miles from Mrs. Taylor's farm. One of the sisters was crazy, and sometimes a little violent, but not often.

At last the time seemed ripe for a final advance, and Brown gathered his courage together and resolved to make it. He would take along a contribution of double the usual size, and win the mother over; with her opposition annulled, the rest of the conquest would be sure and prompt.

He took to the road in the middle of a placid Sunday afternoon in the soft Missourian summer, and he was equipped properly for his mission. He was clothed all in white linen, with a blue ribbon for a necktie, and he had on dressy tight boots. His horse and buggy were the finest that the livery stable could furnish. The lap robe was of white linen, it was new, and it had a hand-worked border that could not be rivaled in that region for beauty and elaboration.

When he was four miles out on the lonely road and was walking his horse over a wooden bridge, his straw hat blew off and fell in the creek, and floated down and lodged against a bar. He did not quite know what to do. He must have the hat, that was manifest; but how was he to get it?

Then he had an idea. The roads were empty, nobody was stirring. Yes, he would risk it. He led the horse to the roadside and set it to cropping the grass; then he undressed and put his clothes in the buggy, petted the horse a moment to secure its compassion and its loyalty, then hurried to the stream. He swam out and soon had the hat. When he got to the top of the bank the horse was gone!

His legs almost gave way under him. The horse was walking leisurely along the road. Brown trotted after it, saying, "Whoa, whoa, there's a good fellow;" but whenever he got near enough to chance a jump for the buggy, the horse quickened its pace a little and defeated him. And so this went on, the naked man perishing with anxiety, and expecting every moment to see people come in sight. He tagged on and on, imploring the horse, beseeching the horse, till he had left a mile behind him, and was closing up on the Taylor premises; then at last he was successful, and got into the buggy. He flung on his shirt, his necktie, and his coat; then reached for—but he was too late; he sat suddenly down and pulled up the lap-robe, for he saw some one coming out of the gate—a woman; he thought. He wheeled the horse to the left, and struck briskly up the cross-road. It was perfectly straight, and exposed on both sides; but there were woods and a sharp turn three miles ahead, and he was very grateful when he got there. As he passed around the turn he slowed down to a walk, and reached for his tr—— too late again.

He had come upon Mrs. Enderby, Mrs. Glossop, Mrs. Taylor, and Mary. They were on foot, and seemed tired and excited. They came at once to the buggy and shook hands, and all spoke at once, and said eagerly and earnestly, how glad they were that he was come, and how fortunate it was. And Mrs. Enderby said, impressively:

"It looks like an accident, his coming at such a time; but let no one profane it with such a name; he was sent—sent from on high."

They were all moved, and Mrs. Glossop said in an awed voice:

"Sarah Enderby, you never said a truer word in your life. This is no accident, it is a special Providence. He was sent. He is an angel—an angel as truly as ever angel was—an angel of deliverance. I say angel, Sarah Enderby, and will have no other word. Don't let any one ever say to me again, that there's no such thing as special Providences; for if this isn't one, let them account for it that can."

"I know it's so," said Mrs. Taylor, fervently. "John Brown, I could worship you; I could go down on my knees to you. Didn't something tell you?—didn't you feel that you were sent? I could kiss the hem of your laprobe."

He was not able to speak; he was helpless with shame and fright. Mrs. Taylor went on:

"Why, just look at it all around, Julia Glossop. Any person can see the hand of Providence in it. Here at noon what do we see? We see the smoke rising. I speak up and say, 'That's the Old People's cabin afire.' Didn't I, Julia Glossop?"

"The very words you said, Nancy Taylor. I was as close to you as I am now, and I heard them. You may have said hut instead of cabin, but in substance it's the same. And you were looking pale, too."

"Pale? I was that pale that if—why, you just compare it with this laprobe. Then the next thing I said was, 'Mary Taylor, tell the hired man to rig up the team-we'll go to the rescue.' And she said, 'Mother, don't you know you told him he could drive to see his people, and stay over Sunday?' And it was just so. I declare for it, I had forgotten it. 'Then,' said I, 'we'll go afoot.' And go we did. And found Sarah Enderby on the road."

"And we all went together," said Mrs. Enderby. "And found the cabin set fire to and burnt down by the crazy one, and the poor old things so old and feeble that they couldn't go afoot. And we got them to a shady place and made them as comfortable as we could, and began to wonder which way to turn to find some way to get them conveyed to Nancy Taylor's house. And I spoke up and said—now what did I say? Didn't I say, 'Providence will provide'?"

"Why sure as you live, so you did! I had forgotten it."

"So had I," said Mrs. Glossop and Mrs. Taylor; "but you certainly said it. Now wasn't that remarkable?"

"Yes, I said it. And then we went to Mr. Moseley's, two miles, and all of them were gone to the camp meeting over on Stony Fork; and then we came all the way back, two miles, and then here, another mile—and Providence has provided. You see it yourselves."

They gazed at each other awe-struck, and lifted their hands and said in unison:

"It's per-fectly wonderful."

"And then," said Mrs. Glossop, "what do you think we had better do--let Mr. Brown drive the Old People to Nancy Taylor's one at a time, or put both of them in the buggy, and him lead the horse?"

Brown gasped.

"Now, then, that's a question," said Mrs. Enderby. "You see, we are all tired out, and any way we fix it it's going to be difficult. For if Mr. Brown takes both of them, at least one of us must, go back to help him, for he can't load them into the buggy by himself, and they so helpless."

"That is so," said Mrs. Taylor. "It doesn't look-oh, how would this do?—one of us drive there with Mr. Brown, and the rest of you go along to my house and get things ready. I'll go with him. He and I together can lift one of the Old People into the buggy; then drive her to my house and——

"But who will take care of the other one?" said Mrs. Enderby. "We musn't leave her there in the woods alone, you know—especially the crazy one. There and back is eight miles, you see."

They had all been sitting on the grass beside the buggy for a while, now, trying to rest their weary bodies. They fell silent a moment or two, and struggled in thought over the baffling situation; then Mrs. Enderby brightened and said:

"I think I've got the idea, now. You see, we can't walk any more. Think what we've done: four miles there, two to Moseley's, is six, then back to here—nine miles since noon, and not a bite to eat; I declare I don't see how we've done it; and as for me, I am just famishing. Now, somebody's got to go back, to help Mr. Brown—there's no getting around that; but whoever goes has got to ride, not walk. So my idea is this: one of us to ride back with Mr. Brown, then ride to Nancy Taylor's house with one of the Old People, leaving Mr. Brown to keep the other old one company, you all to go now to Nancy's and rest and wait; then one of you drive back and get the other one and drive her to Nancy's, and Mr. Brown walk."

"Splendid!" they all cried. "Oh, that will do—that will answer perfectly." And they all said that Mrs. Enderby had the best head for planning, in the company; and they said that they wondered that they hadn't thought of this simple plan themselves. They hadn't meant to take back the compliment, good simple souls, and didn't know they had done it. After a consultation it was decided that Mrs. Enderby should drive back with Brown, she being entitled to the distinction because she had invented the plan. Everything now being satisfactorily arranged and settled, the ladies rose, relieved and happy, and brushed down their gowns, and three of them started homeward; Mrs. Enderby set her foot on the buggy-step and was about to climb in, when Brown found a remnant of his voice and gasped out—

"Please Mrs. Enderby, call them back—I am very weak; I can't walk, I can't, indeed."

"Why, dear Mr. Brown! You do look pale; I am ashamed of myself that I didn't notice it sooner. Come back-all of you! Mr. Brown is not well. Is there anything I can do for you, Mr. Brown?—I'm real sorry. Are you in pain?"

"No, madam, only weak; I am not sick, but only just weak—lately; not long, but just lately."

The others came back, and poured out their sympathies and commiserations, and were full of self-reproaches for not having noticed how pale he was.

And they at once struck out a new plan, and soon agreed that it was by far the best of all. They would all go to Nancy Taylor's house and see to Brown's needs first. He could lie on the sofa in the parlor, and while Mrs. Taylor and Mary took care of him the other two ladies would take the buggy and go and get one of the Old People, and leave one of themselves with the other one, and——

By this time, without any solicitation, they were at the horse's head and were beginning to turn him around. The danger was imminent, but Brown found his voice again and saved himself. He said—

"But ladies, you are overlooking something which makes the plan impracticable. You see, if you bring one of them home, and one remains behind with the other, there will be three persons there when one of you comes back for that other, for some one must drive the buggy back, and three can't come home in it."

They all exclaimed, "Why, sure-ly, that is so!" and they were, all perplexed again.

"Dear, dear, what can we do?" said Mrs. Glossop; "it is the most mixed-up thing that ever was. The fox and the goose and the corn and things—oh, dear, they are nothing to it."

They sat wearily down once more, to further torture their tormented heads for a plan that would work. Presently Mary offered a plan; it was her first effort. She said:

"I am young and strong, and am refreshed, now. Take Mr. Brown to our house, and give him help—you see how plainly he needs it. I will go back and take care of the Old People; I can be there in twenty minutes. You can go on and do what you first started to do—wait on the main road at our house until somebody comes along with a wagon; then send and bring away the three of us. You won't have to wait long; the farmers will soon be coming back from town, now. I will keep old Polly patient and cheered up—the crazy one doesn't need it."

This plan was discussed and accepted; it seemed the best that could be done, in the circumstances, and the Old People must be getting discouraged by this time.

Brown felt relieved, and was deeply thankful. Let him once get to the main road and he would find a way to escape.

Then Mrs. Taylor said:

"The evening chill will be coming on, pretty soon, and those poor old burnt-out things will need some kind of covering. Take the lap-robe with you, dear."

"Very well, Mother, I will."

She stepped to the buggy and put out her hand to take it——

That was the end of the tale. The passenger who told it said that when he read the story twenty-five years ago in a train he was interrupted at that point—the train jumped off a bridge.

At first we thought we could finish the story quite easily, and we set to work with confidence; but it soon began to appear that it was not a simple thing, but difficult and baffling. This was on account of Brown's character—great generosity and kindliness, but complicated with unusual shyness and diffidence, particularly in the presence of ladies. There was his love for Mary, in a hopeful state but not yet secure—just in a condition, indeed, where its affair must be handled with great tact, and no mistakes made, no offense given. And there was the mother wavering, half willing-by adroit and flawless diplomacy to be won over, now, or perhaps never at all. Also, there were the helpless Old People yonder in the woods waiting-their fate and Brown's happiness to be determined by what Brown should do within the next two seconds. Mary was reaching for the lap-robe; Brown must decide-there was no time to be lost.

Of course none but a happy ending of the story would be accepted by the jury; the finish must find Brown in high credit with the ladies, his behavior without blemish, his modesty unwounded, his character for self sacrifice maintained, the Old People rescued through him, their benefactor, all the party proud of him, happy in him, his praises on all their tongues.

We tried to arrange this, but it was beset with persistent and irreconcilable difficulties. We saw that Brown's shyness would not allow him to give up the lap-robe. This would offend Mary and her mother; and it would surprise the other ladies, partly because this stinginess toward the suffering Old People would be out of character with Brown, and partly because he was a special Providence and could not properly act so. If asked to explain his conduct, his shyness would not allow him to tell the truth, and lack of invention and practice would find him incapable of contriving a lie that would wash. We worked at the troublesome problem until three in the morning.

Meantime Mary was still reaching for the lap-robe. We gave it up, and

decided to let her continue to reach. It is the reader's privilege to

determine for himself how the thing came out.

|

|

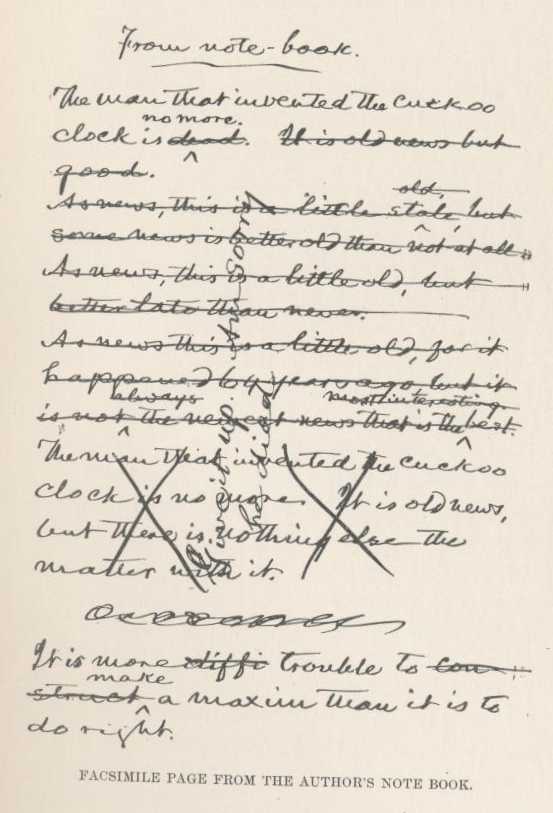

It is more trouble to make a maxim than it is to do right.

On the seventh day out we saw a dim vast bulk standing up out of the wastes of the Pacific and knew that that spectral promontory was Diamond Head, a piece of this world which I had not seen before for twenty-nine years. So we were nearing Honolulu, the capital city of the Sandwich Islands—those islands which to me were Paradise; a Paradise which I had been longing all those years to see again. Not any other thing in the world could have stirred me as the sight of that great rock did.

In the night we anchored a mile from shore. Through my port I could see the twinkling lights of Honolulu and the dark bulk of the mountain-range that stretched away right and left. I could not make out the beautiful Nuuana valley, but I knew where it lay, and remembered how it used to look in the old times. We used to ride up it on horseback in those days—we young people—and branch off and gather bones in a sandy region where one of the first Kamehameha's battles was fought. He was a remarkable man, for a king; and he was also a remarkable man for a savage. He was a mere kinglet and of little or no consequence at the time of Captain Cook's arrival in 1788; but about four years afterward he conceived the idea of enlarging his sphere of influence. That is a courteous modern phrase which means robbing your neighbor—for your neighbor's benefit; and the great theater of its benevolences is Africa. Kamehameha went to war, and in the course of ten years he whipped out all the other kings and made himself master of every one of the nine or ten islands that form the group. But he did more than that. He bought ships, freighted them with sandal wood and other native products, and sent them as far as South America and China; he sold to his savages the foreign stuffs and tools and utensils which came back in these ships, and started the march of civilization. It is doubtful if the match to this extraordinary thing is to be found in the history of any other savage. Savages are eager to learn from the white man any new way to kill each other, but it is not their habit to seize with avidity and apply with energy the larger and nobler ideas which he offers them. The details of Kamehameha's history show that he was always hospitably ready to examine the white man's ideas, and that he exercised a tidy discrimination in making his selections from the samples placed on view.

A shrewder discrimination than was exhibited by his son and successor, Liholiho, I think. Liholiho could have qualified as a reformer, perhaps, but as a king he was a mistake. A mistake because he tried to be both king and reformer. This is mixing fire and gunpowder together. A king has no proper business with reforming. His best policy is to keep things as they are; and if he can't do that, he ought to try to make them worse than they are. This is not guesswork; I have thought over this matter a good deal, so that if I should ever have a chance to become a king I would know how to conduct the business in the best way.

When Liholiho succeeded his father he found himself possessed of an equipment of royal tools and safeguards which a wiser king would have known how to husband, and judiciously employ, and make profitable. The entire country was under the one scepter, and his was that scepter. There was an Established Church, and he was the head of it. There was a Standing Army, and he was the head of that; an Army of 114 privates under command of 27 Generals and a Field Marshal. There was a proud and ancient Hereditary Nobility. There was still one other asset. This was the tabu—an agent endowed with a mysterious and stupendous power, an agent not found among the properties of any European monarch, a tool of inestimable value in the business. Liholiho was headmaster of the tabu. The tabu was the most ingenious and effective of all the inventions that has ever been devised for keeping a people's privileges satisfactorily restricted.

It required the sexes to live in separate houses. It did not allow people to eat in either house; they must eat in another place. It did not allow a man's woman-folk to enter his house. It did not allow the sexes to eat together; the men must eat first, and the women must wait on them. Then the women could eat what was left—if anything was left—and wait on themselves. I mean, if anything of a coarse or unpalatable sort was left, the women could have it. But not the good things, the fine things, the choice things, such as pork, poultry, bananas, cocoanuts, the choicer varieties of fish, and so on. By the tabu, all these were sacred to the men; the women spent their lives longing for them and wondering what they might taste like; and they died without finding out.

These rules, as you see, were quite simple and clear. It was easy to remember them; and useful. For the penalty for infringing any rule in the whole list was death. Those women easily learned to put up with shark and taro and dog for a diet when the other things were so expensive.

It was death for any one to walk upon tabu'd ground; or defile a tabu'd

thing with his touch; or fail in due servility to a chief; or step upon

the king's shadow. The nobles and the King and the priests were always

suspending little rags here and there and yonder, to give notice to the

people that the decorated spot or thing was tabu, and death lurking near.

The struggle for life was difficult and chancy in the islands in those

days.

Thus advantageously was the new king situated. Will it be believed that the first thing he did was to destroy his Established Church, root and branch? He did indeed do that. To state the case figuratively, he was a prosperous sailor who burnt his ship and took to a raft. This Church was a horrid thing. It heavily oppressed the people; it kept them always trembling in the gloom of mysterious threatenings; it slaughtered them in sacrifice before its grotesque idols of wood and stone; it cowed them, it terrorized them, it made them slaves to its priests, and through the priests to the king. It was the best friend a king could have, and the most dependable. To a professional reformer who should annihilate so frightful and so devastating a power as this Church, reverence and praise would be due; but to a king who should do it, could properly be due nothing but reproach; reproach softened by sorrow; sorrow for his unfitness for his position.

He destroyed his Established Church, and his kingdom is a republic today, in consequence of that act.

When he destroyed the Church and burned the idols he did a mighty thing for civilization and for his people's weal—but it was not "business." It was unkingly, it was inartistic. It made trouble for his line. The American missionaries arrived while the burned idols were still smoking. They found the nation without a religion, and they repaired the defect. They offered their own religion and it was gladly received. But it was no support to arbitrary kingship, and so the kingly power began to weaken from that day. Forty-seven years later, when I was in the islands, Kamehameha V. was trying to repair Liholiho's blunder, and not succeeding. He had set up an Established Church and made himself the head of it. But it was only a pinchbeck thing, an imitation, a bauble, an empty show. It had no power, no value for a king. It could not harry or burn or slay, it in no way resembled the admirable machine which Liholiho destroyed. It was an Established Church without an Establishment; all the people were Dissenters.

Long before that, the kingship had itself become but a name, a show. At an early day the missionaries had turned it into something very much like a republic; and here lately the business whites have turned it into something exactly like it.

In Captain Cook's time (1778), the native population of the islands was estimated at 400,000; in 1836 at something short of 200,000, in 1866 at 50,000; it is to-day, per census, 25,000. All intelligent people praise Kamehameha I. and Liholiho for conferring upon their people the great boon of civilization. I would do it myself, but my intelligence is out of repair, now, from over-work.

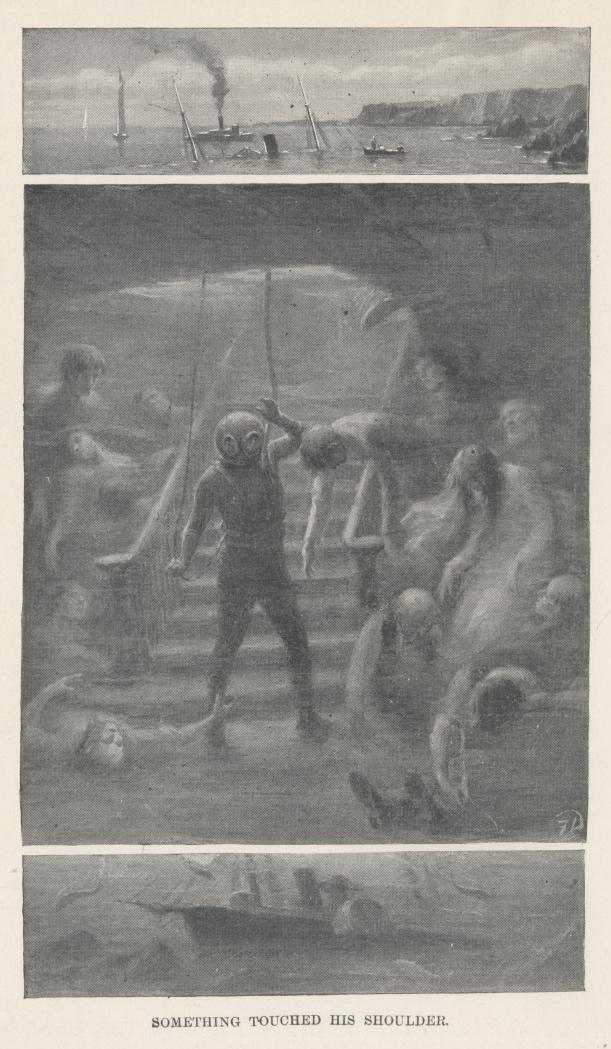

When I was in the islands nearly a generation ago, I was acquainted with

a young American couple who had among their belongings an attractive

little son of the age of seven—attractive but not practicably

companionable with me, because he knew no English. He had played from

his birth with the little Kanakas on his father's plantation, and had

preferred their language and would learn no other. The family removed to

America a month after I arrived in the islands, and straightway the boy

began to lose his Kanaka and pick up English. By the time he was twelve

he hadn't a word of Kanaka left; the language had wholly departed from

his tongue and from his comprehension. Nine years later, when he was

twenty-one, I came upon the family in one of the lake towns of New York,

and the mother told me about an adventure which her son had been having.

By trade he was now a professional diver. A passenger boat had been

caught in a storm on the lake, and had gone down, carrying her people

with her. A few days later the young diver descended, with his armor on,

and entered the berth-saloon of the boat, and stood at the foot of the

companionway, with his hand on the rail, peering through the dim water.

Presently something touched him on the shoulder, and he turned and found

a dead man swaying and bobbing about him and seemingly inspecting him

inquiringly. He was paralyzed with fright.

His entry had disturbed the water, and now he discerned a number of dim corpses making for him and wagging their heads and swaying their bodies like sleepy people trying to dance. His senses forsook him, and in that condition he was drawn to the surface. He was put to bed at home, and was soon very ill. During some days he had seasons of delirium which lasted several hours at a time; and while they lasted he talked Kanaka incessantly and glibly; and Kanaka only. He was still very ill, and he talked to me in that tongue; but I did not understand it, of course. The doctor-books tell us that cases like this are not uncommon. Then the doctors ought to study the cases and find out how to multiply them. Many languages and things get mislaid in a person's head, and stay mislaid for lack of this remedy.

Many memories of my former visit to the islands came up in my mind while we lay at anchor in front of Honolulu that night. And pictures—pictures pictures—an enchanting procession of them! I was impatient for the morning to come.

When it came it brought disappointment, of course. Cholera had broken out in the town, and we were not allowed to have any communication with the shore. Thus suddenly did my dream of twenty-nine years go to ruin. Messages came from friends, but the friends themselves I was not to have any sight of. My lecture-hall was ready, but I was not to see that, either.

Several of our passengers belonged in Honolulu, and these were sent ashore; but nobody could go ashore and return. There were people on shore who were booked to go with us to Australia, but we could not receive them; to do it would cost us a quarantine-term in Sydney. They could have escaped the day before, by ship to San Francisco; but the bars had been put up, now, and they might have to wait weeks before any ship could venture to give them a passage any whither. And there were hardships for others. An elderly lady and her son, recreation-seekers from Massachusetts, had wandered westward, further and further from home, always intending to take the return track, but always concluding to go still a little further; and now here they were at anchor before Honolulu positively their last westward-bound indulgence—they had made up their minds to that—but where is the use in making up your mind in this world? It is usually a waste of time to do it. These two would have to stay with us as far as Australia. Then they could go on around the world, or go back the way they had come; the distance and the accommodations and outlay of time would be just the same, whichever of the two routes they might elect to take. Think of it: a projected excursion of five hundred miles gradually enlarged, without any elaborate degree of intention, to a possible twenty-four thousand. However, they were used to extensions by this time, and did not mind this new one much.

And we had with us a lawyer from Victoria, who had been sent out by the Government on an international matter, and he had brought his wife with him and left the children at home with the servants and now what was to be done? Go ashore amongst the cholera and take the risks? Most certainly not. They decided to go on, to the Fiji islands, wait there a fortnight for the next ship, and then sail for home. They couldn't foresee that they wouldn't see a homeward-bound ship again for six weeks, and that no word could come to them from the children, and no word go from them to the children in all that time. It is easy to make plans in this world; even a cat can do it; and when one is out in those remote oceans it is noticeable that a cat's plans and a man's are worth about the same. There is much the same shrinkage in both, in the matter of values.

There was nothing for us to do but sit about the decks in the shade of the awnings and look at the distant shore. We lay in luminous blue water; shoreward the water was green-green and brilliant; at the shore itself it broke in a long white ruffle, and with no crash, no sound that we could hear. The town was buried under a mat of foliage that looked like a cushion of moss. The silky mountains were clothed in soft, rich splendors of melting color, and some of the cliffs were veiled in slanting mists. I recognized it all. It was just as I had seen it long before, with nothing of its beauty lost, nothing of its charm wanting.

A change had come, but that was political, and not visible from the ship. The monarchy of my day was gone, and a republic was sitting in its seat. It was not a material change. The old imitation pomps, the fuss and feathers, have departed, and the royal trademark—that is about all that one could miss, I suppose. That imitation monarchy, was grotesque enough, in my time; if it had held on another thirty years it would have been a monarchy without subjects of the king's race.

We had a sunset of a very fine sort. The vast plain of the sea was marked off in bands of sharply-contrasted colors: great stretches of dark blue, others of purple, others of polished bronze; the billowy mountains showed all sorts of dainty browns and greens, blues and purples and blacks, and the rounded velvety backs of certain of them made one want to stroke them, as one would the sleek back of a cat. The long, sloping promontory projecting into the sea at the west turned dim and leaden and spectral, then became suffused with pink—dissolved itself in a pink dream, so to speak, it seemed so airy and unreal. Presently the cloud-rack was flooded with fiery splendors, and these were copied on the surface of the sea, and it made one drunk with delight to look upon it.

From talks with certain of our passengers whose home was Honolulu, and from a sketch by Mrs. Mary H. Krout, I was able to perceive what the Honolulu of to-day is, as compared with the Honolulu of my time. In my time it was a beautiful little town, made up of snow-white wooden cottages deliciously smothered in tropical vines and flowers and trees and shrubs; and its coral roads and streets were hard and smooth, and as white as the houses. The outside aspects of the place suggested the presence of a modest and comfortable prosperity—a general prosperity—perhaps one might strengthen the term and say universal. There were no fine houses, no fine furniture. There were no decorations. Tallow candles furnished the light for the bedrooms, a whale-oil lamp furnished it for the parlor. Native matting served as carpeting. In the parlor one would find two or three lithographs on the walls—portraits as a rule: Kamehameha IV., Louis Kossuth, Jenny Lind; and may be an engraving or two: Rebecca at the Well, Moses smiting the rock, Joseph's servants finding the cup in Benjamin's sack. There would be a center table, with books of a tranquil sort on it: The Whole Duty of Man, Baxter's Saints' Rest, Fox's Martyrs, Tupper's Proverbial Philosophy, bound copies of The Missionary Herald and of Father Damon's Seaman's Friend. A melodeon; a music stand, with 'Willie, We have Missed You', 'Star of the Evening', 'Roll on Silver Moon', 'Are We Most There', 'I Would not Live Alway', and other songs of love and sentiment, together with an assortment of hymns. A what-not with semi-globular glass paperweights, enclosing miniature pictures of ships, New England rural snowstorms, and the like; sea-shells with Bible texts carved on them in cameo style; native curios; whale's tooth with full-rigged ship carved on it. There was nothing reminiscent of foreign parts, for nobody had been abroad. Trips were made to San Francisco, but that could not be called going abroad. Comprehensively speaking, nobody traveled.

But Honolulu has grown wealthy since then, and of course wealth has introduced changes; some of the old simplicities have disappeared. Here is a modern house, as pictured by Mrs. Krout:

"Almost every house is surrounded by extensive lawns and gardens enclosed by walls of volcanic stone or by thick hedges of the brilliant hibiscus.

"The houses are most tastefully and comfortably furnished; the floors are either of hard wood covered with rugs or with fine Indian matting, while there is a preference, as in most warm countries, for rattan or bamboo furniture; there are the usual accessories of bric-a-brac, pictures, books, and curios from all parts of the world, for these island dwellers are indefatigable travelers.

"Nearly every house has what is called a lanai. It is a large apartment, roofed, floored, open on three sides, with a door or a draped archway opening into the drawing-room. Frequently the roof is formed by the thick interlacing boughs of the hou tree, impervious to the sun and even to the rain, except in violent storms. Vines are trained about the sides—the stephanotis or some one of the countless fragrant and blossoming trailers which abound in the islands. There are also curtains of matting that may be drawn to exclude the sun or rain. The floor is bare for coolness, or partially covered with rugs, and the lanai is prettily furnished with comfortable chairs, sofas, and tables loaded with flowers, or wonderful ferns in pots.

"The lanai is the favorite reception room, and here at any social function the musical program is given and cakes and ices are served; here morning callers are received, or gay riding parties, the ladies in pretty divided skirts, worn for convenience in riding astride,—the universal mode adopted by Europeans and Americans, as well as by the natives.

"The comfort and luxury of such an apartment, especially at a seashore villa, can hardly be imagined. The soft breezes sweep across it, heavy with the fragrance of jasmine and gardenia, and through the swaying boughs of palm and mimosa there are glimpses of rugged mountains, their summits veiled in clouds, of purple sea with the white surf beating eternally against the reefs, whiter still in the yellow sunlight or the magical moonlight of the tropics."

There: rugs, ices, pictures, lanais, worldly books, sinful bric-a-brac fetched from everywhere. And the ladies riding astride. These are changes, indeed. In my time the native women rode astride, but the white ones lacked the courage to adopt their wise custom. In my time ice was seldom seen in Honolulu. It sometimes came in sailing vessels from New England as ballast; and then, if there happened to be a man-of-war in port and balls and suppers raging by consequence, the ballast was worth six hundred dollars a ton, as is evidenced by reputable tradition. But the ice-machine has traveled all over the world, now, and brought ice within everybody's reach. In Lapland and Spitzbergen no one uses native ice in our day, except the bears and the walruses.

The bicycle is not mentioned. It was not necessary. We know that it is there, without inquiring. It is everywhere. But for it, people could never have had summer homes on the summit of Mont Blanc; before its day, property up there had but a nominal value. The ladies of the Hawaiian capital learned too late the right way to occupy a horse—too late to get much benefit from it. The riding-horse is retiring from business everywhere in the world. In Honolulu a few years from now he will be only a tradition.

We all know about Father Damien, the French priest who voluntarily forsook the world and went to the leper island of Molokai to labor among its population of sorrowful exiles who wait there, in slow-consuming misery, for death to come and release them from their troubles; and we know that the thing which he knew beforehand would happen, did happen: that he became a leper himself, and died of that horrible disease. There was still another case of self-sacrifice, it appears. I asked after "Billy" Ragsdale, interpreter to the Parliament in my time—a half-white. He was a brilliant young fellow, and very popular. As an interpreter he would have been hard to match anywhere. He used to stand up in the Parliament and turn the English speeches into Hawaiian and the Hawaiian speeches into English with a readiness and a volubility that were astonishing. I asked after him, and was told that his prosperous career was cut short in a sudden and unexpected way, just as he was about to marry a beautiful half-caste girl. He discovered, by some nearly invisible sign about his skin, that the poison of leprosy was in him. The secret was his own, and might be kept concealed for years; but he would not be treacherous to the girl that loved him; he would not marry her to a doom like his. And so he put his affairs in order, and went around to all his friends and bade them good-bye, and sailed in the leper ship to Molokai. There he died the loathsome and lingering death that all lepers die.

In this place let me insert a paragraph or two from "The Paradise of the Pacific" (Rev. H. H. Gowen)—

"Poor lepers! It is easy for those who have no relatives or friends among them to enforce the decree of segregation to the letter, but who can write of the terrible, the heart-breaking scenes which that enforcement has brought about?

"A man upon Hawaii was suddenly taken away after a summary arrest, leaving behind him a helpless wife about to give birth to a babe. The devoted wife with great pain and risk came the whole journey to Honolulu, and pleaded until the authorities were unable to resist her entreaty that she might go and live like a leper with her leper husband.

"A woman in the prime of life and activity is condemned as an incipient leper, suddenly removed from her home, and her husband returns to find his two helpless babes moaning for their lost mother.

"Imagine it! The case of the babies is hard, but its bitterness is a trifle—less than a trifle—less than nothing—compared to what the mother must suffer; and suffer minute by minute, hour by hour, day by day, month by month, year by year, without respite, relief, or any abatement of her pain till she dies.

"One woman, Luka Kaaukau, has been living with her leper husband in the settlement for twelve years. The man has scarcely a joint left, his limbs are only distorted ulcerated stumps, for four years his wife has put every particle of food into his mouth. He wanted his wife to abandon his wretched carcass long ago, as she herself was sound and well, but Luka said that she was content to remain and wait on the man she loved till the spirit should be freed from its burden.

"I myself have known hard cases enough:—of a girl, apparently in full health, decorating the church with me at Easter, who before Christmas is taken away as a confirmed leper; of a mother hiding her child in the mountains for years so that not even her dearest friends knew that she had a child alive, that he might not be taken away; of a respectable white man taken away from his wife and family, and compelled to become a dweller in the Leper Settlement, where he is counted dead, even by the insurance companies."

And one great pity of it all is, that these poor sufferers are innocent. The leprosy does not come of sins which they committed, but of sins committed by their ancestors, who escaped the curse of leprosy!

Mr. Gowan has made record of a certain very striking circumstance. Would

you expect to find in that awful Leper Settlement a custom worthy to be

transplanted to your own country? They have one such, and it is

inexpressibly touching and beautiful. When death sets open the

prison-door of life there, the band salutes the freed soul with a burst of glad

music!

A dozen direct censures are easier to bear than one morganatic compliment.

Sailed from Honolulu.—From diary:

Sept. 2. Flocks of flying fish-slim, shapely, graceful, and intensely white. With the sun on them they look like a flight of silver fruit-knives. They are able to fly a hundred yards.

Sept. 3. In 9 deg. 50' north latitude, at breakfast. Approaching the equator on a long slant. Those of us who have never seen the equator are a good deal excited. I think I would rather see it than any other thing in the world. We entered the "doldrums" last night—variable winds, bursts of rain, intervals of calm, with chopping seas and a wobbly and drunken motion to the ship—a condition of things findable in other regions sometimes, but present in the doldrums always. The globe-girdling belt called the doldrums is 20 degrees wide, and the thread called the equator lies along the middle of it.

Sept. 4. Total eclipse of the moon last night. At 7.30 it began to go

off. At total—or about that—it was like a rich rosy cloud with a

tumbled surface framed in the circle and projecting from it—a bulge of

strawberry-ice, so to speak. At half-eclipse the moon was like a gilded

acorn in its cup.

Sept. 5. Closing in on the equator this noon. A sailor explained to a

young girl that the ship's speed is poor because we are climbing up the

bulge toward the center of the globe; but that when we should once get

over, at the equator, and start down-hill, we should fly. When she asked

him the other day what the fore-yard was, he said it was the front yard,

the open area in the front end of the ship. That man has a good deal of

learning stored up, and the girl is likely to get it all.

Afternoon. Crossed the equator. In the distance it looked like a blue ribbon stretched across the ocean. Several passengers kodak'd it. We had no fool ceremonies, no fantastics, no horse play. All that sort of thing has gone out. In old times a sailor, dressed as Neptune, used to come in over the bows, with his suite, and lather up and shave everybody who was crossing the equator for the first time, and then cleanse these unfortunates by swinging them from the yard-arm and ducking them three times in the sea. This was considered funny. Nobody knows why. No, that is not true. We do know why. Such a thing could never be funny on land; no part of the old-time grotesque performances gotten up on shipboard to celebrate the passage of the line could ever be funny on shore—they would seem dreary and witless to shore people. But the shore people would change their minds about it at sea, on a long voyage. On such a voyage, with its eternal monotonies, people's intellects deteriorate; the owners of the intellects soon reach a point where they almost seem to prefer childish things to things of a maturer degree. One is often surprised at the juvenilities which grown people indulge in at sea, and the interest they take in them, and the consuming enjoyment they get out of them. This is on long voyages only. The mind gradually becomes inert, dull, blunted; it loses its accustomed interest in intellectual things; nothing but horse-play can rouse it, nothing but wild and foolish grotesqueries can entertain it. On short voyages it makes no such exposure of itself; it hasn't time to slump down to this sorrowful level.

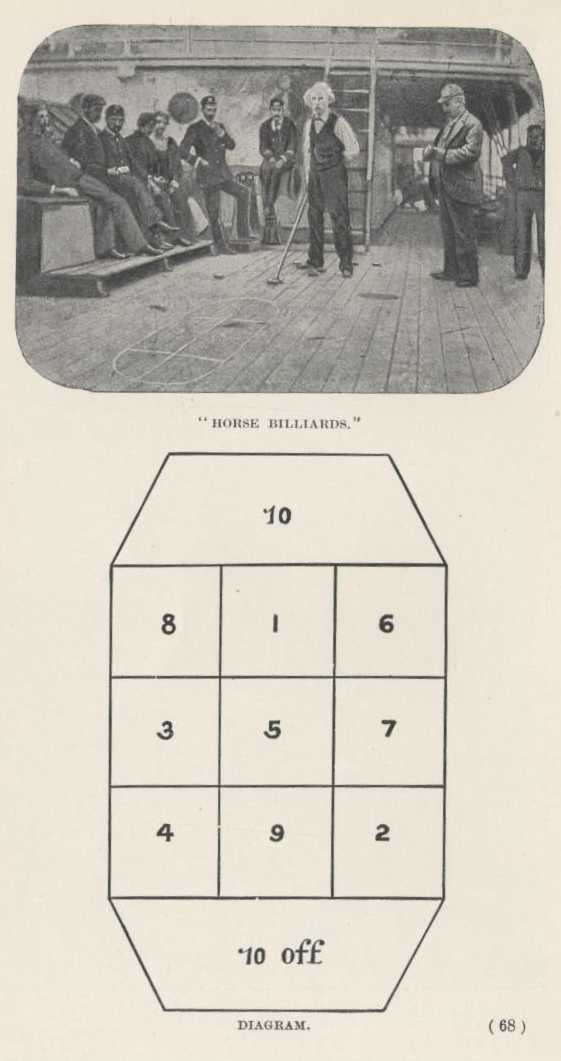

The short-voyage passenger gets his chief physical exercise out of "horse-billiards"—shovel-board. It is a good game. We play it in this ship. A quartermaster chalks off a diagram like this-on the deck.

The player uses a cue that is like a broom-handle with a quarter-moon of

wood fastened to the end of it. With this he shoves wooden disks the

size of a saucer—he gives the disk a vigorous shove and sends it fifteen

or twenty feet along the deck and lands it in one of the squares if he

can. If it stays there till the inning is played out, it will count as

many points in the game as the figure in the square it has stopped in

represents. The adversary plays to knock that disk out and leave his own

in its place—particularly if it rests upon the 9 or 10 or some other of

the high numbers; but if it rests in the "10off" he backs it up—lands

his disk behind it a foot or two, to make it difficult for its owner to

knock it out of that damaging place and improve his record. When the

inning is played out it may be found that each adversary has placed his

four disks where they count; it may be found that some of them are

touching chalk lines and not counting; and very often it will be found

that there has been a general wreckage, and that not a disk has been left

within the diagram. Anyway, the result is recorded, whatever it is, and

the game goes on. The game is 100 points, and it takes from twenty

minutes to forty to play it, according to luck and the condition of the

sea. It is an exciting game, and the crowd of spectators furnish

abundance of applause for fortunate shots and plenty of laughter for the

other kind. It is a game of skill, but at the same time the uneasy

motion of the ship is constantly interfering with skill; this makes it a

chancy game, and the element of luck comes largely in.

We had a couple of grand tournaments, to determine who should be "Champion of the Pacific"; they included among the participants nearly all the passengers, of both sexes, and the officers of the ship, and they afforded many days of stupendous interest and excitement, and murderous exercise—for horse-billiards is a physically violent game.

The figures in the following record of some of the closing games in the first tournament will show, better than any description, how very chancy the game is. The losers here represented had all been winners in the previous games of the series, some of them by fine majorities:

| Chase, | 102 | Mrs. D., | 57 | Mortimer, | 105 | The Surgeon, | 92 |

| Miss C., | 105 | Mrs. T., | 9 | Clemens, | 101 | Taylor, | 92 |

| Taylor, | 109 | Davies, | 95 | Miss C., | 108 | Mortimer, | 55 |

| Thomas, | 102 | Roper, | 76 | Clemens, | 111 | Miss C., | 89 |

| Coomber, | 106 | Chase, | 98 |

And so on; until but three couples of winners were left. Then I beat my man, young Smith beat his man, and Thomas beat his. This reduced the combatants to three. Smith and I took the deck, and I led off. At the close of the first inning I was 10 worse than nothing and Smith had scored 7. The luck continued against me. When I was 57, Smith was 97—within 3 of out. The luck changed then. He picked up a 10-off or so, and couldn't recover. I beat him.

The next game would end tournament No. 1.

Mr. Thomas and I were the contestants. He won the lead and went to the bat—so to speak. And there he stood, with the crotch of his cue resting against his disk while the ship rose slowly up, sank slowly down, rose again, sank again. She never seemed to rise to suit him exactly. She started up once more; and when she was nearly ready for the turn, he let drive and landed his disk just within the left-hand end of the 10. (Applause). The umpire proclaimed "a good 10," and the game-keeper set it down. I played: my disk grazed the edge of Mr. Thomas's disk, and went out of the diagram. (No applause.)

Mr. Thomas played again—and landed his second disk alongside of the first, and almost touching its right-hand side. "Good 10." (Great applause.)

I played, and missed both of them. (No applause.)

Mr. Thomas delivered his third shot and landed his disk just at the right of the other two. " Good 10." (Immense applause.)

There they lay, side by side, the three in a row. It did not seem possible that anybody could miss them. Still I did it. (Immense silence.)

Mr. Thomas played his last disk. It seems incredible, but he actually landed that disk alongside of the others, and just to the right of them-a straight solid row of 4 disks. (Tumultuous and long-continued applause.)

Then I played my last disk. Again it did not seem possible that anybody could miss that row—a row which would have been 14 inches long if the disks had been clamped together; whereas, with the spaces separating them they made a longer row than that. But I did it. It may be that I was getting nervous.

I think it unlikely that that innings has ever had its parallel in the history of horse-billiards. To place the four disks side by side in the 10 was an extraordinary feat; indeed, it was a kind of miracle. To miss them was another miracle. It will take a century to produce another man who can place the four disks in the 10; and longer than that to find a man who can't knock them out. I was ashamed of my performance at the time, but now that I reflect upon it I see that it was rather fine and difficult.

Mr. Thomas kept his luck, and won the game, and later the championship.

In a minor tournament I won the prize, which was a Waterbury watch. I

put it in my trunk. In Pretoria, South Africa, nine months afterward, my

proper watch broke down and I took the Waterbury out, wound it, set it by

the great clock on the Parliament House (8.05), then went back to my room

and went to bed, tired from a long railway journey. The parliamentary

clock had a peculiarity which I was not aware of at the

time—a peculiarity which exists in no other clock, and would not exist in that

one if it had been made by a sane person; on the half-hour it strikes the

succeeding hour, then strikes the hour again, at the proper time. I lay

reading and smoking awhile; then, when I could hold my eyes open no

longer and was about to put out the light, the great clock began to boom,

and I counted ten. I reached for the Waterbury to see how it was getting

along. It was marking 9.30. It seemed rather poor speed for a

three-dollar watch, but I supposed that the climate was affecting it. I shoved

it half an hour ahead; and took to my book and waited to see what would

happen. At 10 the great clock struck ten again. I looked—the Waterbury

was marking half-past 10. This was too much speed for the money, and it

troubled me. I pushed the hands back a half hour, and waited once more;

I had to, for I was vexed and restless now, and my sleepiness was gone.

By and by the great clock struck 11. The Waterbury was marking 10.30. I

pushed it ahead half an hour, with some show of temper. By and by the

great clock struck 11 again. The Waterbury showed up 11.30, now, and I

beat her brains out against the bedstead. I was sorry next day, when I

found out.

To return to the ship.