The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Niagara River, by Archer Butler Hulbert This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org Title: The Niagara River Author: Archer Butler Hulbert Release Date: February 7, 2011 [EBook #35194] Language: English Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1 *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE NIAGARA RIVER *** Produced by Marcia Brooks, Ross Cooling and the Online Distributed Proofreading Canada Team at http://www.pgdpcanada.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/American Libraries.)

In the endeavour to gather into one volume a proper description of the various interests that centre in and around the Niagara River the author of this book felt very sincerely the difficulties of the task before him. As the geologic wonder of a continent and the commercial marvel of the present century, the Niagara River is one of the most remarkable streams in the world. In historic interest, too, it takes rank with any American river. To combine, then, into the pages of a single volume a proper treatment of this subject would be a task that perhaps no one could accomplish satisfactorily.

Works to which the author is most indebted, especially the historical writings of Hon. Peter A. Porter, Severance's Old Trails of the Niagara Frontier, The Niagara Book, and the writings of the scholar of the old New York frontier, the late O. H. Marshall, and the collections of the historical societies along the frontier, are indicated frequently in footnotes and in text. The author's particular indebtedness to Mr. Porter is elsewhere described; he is also in the debt of F. H. Mautz, Henry Guttenstein, Superintendent Edward H. Perry, whose kindness to the author was so characteristic of his treatment of all comers to the shrine over which he presides, E. O. Dunlap, and many others mentioned elsewhere. He has appreciated Mr. Howells's characteristic conscientiousness when he wrote concerning Niagara, "I have always had to take myself in hand, to shake myself up, to look twice, and recur to what I have heard and read of other people's impressions, before I am overpowered by it. Otherwise I am simply charmed." The author has laboured under the difficulty of attempting to remain "overpowered" during a period of several years. That there have been serious lapses in the shape of lucid intervals, the critic will find full soon!

It has seemed best to treat of modern Niagara under what might have been called "Part I." of this volume. The history of the Niagara region proper begins in Chapter VII., the problems of present-day interest occupying the preceding six chapters.

A. B. H.

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

| I. | Buffalo and the Upper Niagara | 1 |

| II. | From the Falls to Lake Ontario | 23 |

| III. | The Birth of Niagara | 52 |

| IV. | Niagara Bond and Free | 72 |

| V. | Harnessing Niagara Falls | 99 |

| VI. | A Century of Niagara Cranks | 123 |

| VII. | The Old Niagara Frontier | 153 |

| VIII. | From La Salle to De Nonville | 171 |

| IX. | Niagara under Three Flags | 196 |

| X. | The Hero of Upper Canada | 231 |

| XI. | The Second War with England | 263 |

| XII. | Toronto | 292 |

| Index | 315 |

The Strait of Niagara, or the Niagara River, as it is commonly called, ranks among the wonders of the world. The study of this stream is of intense and special interest to many classes of people, notably historians, archæologists, botanists, geologists, artists, mechanics, and electricians. It is doubtful if there is anywhere another thirty-six miles of riverway that can, in this respect, compare with it.

The term "strait" as applied to the Niagara correctly suggests the river's historic importance. The expression, recurring in so many of the relations of French and English military officers, "on this communication" also indicates Niagara's position in the story of the discovery, conquest, and occupation of the continent. It is probably the Falls which, technically, make Niagara a river; and so, in turn, it is the Falls that rendered Niagara an important strategic key of the vast waterway stretching from the mouth of the St. Lawrence to the head of Lake Superior. The lack—so far as it does exist—of historic interest in the immediate Niagara region, the comparative paucity of military [2] events of magnitude along that stream during the old French and the Revolutionary wars proves, on the one hand, what a wilderness separated the English on the South from the French on the North, and, on the other, how strong "the communication" was between Quebec and the French posts in the Middle West. It does not prove that Niagara was the less important.

The Falls increased the historic importance of Niagara because it limited navigation and made a portage necessary; the purposes of trade and missionary enterprise, as well as those of conquest, demanded that this point be occupied, and occupation necessarily meant defence. Here, from Lewiston and Queenston to Chippewa and Port Day (to use modern names) ran the two most famous portage paths of the continent. Here were to be seen at one time or another the footprints of as famous explorers, noble missionaries, and brave soldiers as ever went to conquest in history.

The Niagara River was important in the olden time to every mile of territory drained by the waters that flowed through it. What an empire to hold in fee! Here lies more than one-half the fresh water of the world—the solid contents being, according to Darby 1,547,011,792,300,000; it would form a solid cubic column measuring nearly twenty-two miles on each side.

The most remote body of water tributary to Niagara River is Lake Superior, 381 miles long and 161 miles broad with a circumference of 1150 miles. The Niagara of Lake Superior is the St. Mary's River, twenty-seven miles in length, its current very rapid, with water flowing over great masses of rock into Lake Huron. Lake Huron is 218 [3] miles long and 20 miles wider than Lake Superior, but with a circumference of only 812 miles. Lake Michigan is 345 miles long and 84 broad and enters Lake Huron through Mackinaw Straits which are four miles in length, with a fall of four feet. In turn Lake Huron empties into the St. Clair and Detroit rivers which, with a total fall of eleven feet in fifty-one miles, forms the Niagara of Lake Erie. This sheet of water is 250 miles long and 60 miles broad at its widest part. The area drained by these lakes is as follows, including their own area:

| Lake Superior | 85,000 sq. m. |

| " Huron | 74,000 " |

| " Michigan | 70,040 " |

| " Erie | 39,680 " |

| ———— | |

| Total | 268,720 " |

Considering this as a portion of the St. Lawrence drainage, we have the marvellous spectacle of a navigable waterway from the St. Louis River, Lake Superior, to Cape Gaspé at the mouth of the St. Lawrence, of twenty-one hundred miles in length, the Niagara River being paralleled to-day by the Welland Canal, and lesser canals affording a passageway around the rapids of the St. Mary's in the West and the St. Lawrence in the East. In a previous volume in the present series[1] it was seen that the improved rivers in the Ohio basin now offered a navigable pathway over four thousand miles in length; how insignificant is that prospect in view of this great transcontinental waterway two thousand miles in length but including the 268,000 square miles in the four great lakes alone! Well does George Waldo Browne in his beautiful volume on this subject, The St. Lawrence River, say:

Treated in a more extended manner, according to the ideas of the early French geographers, and taking either the river and lake of Nipigon, on the north of Superior, or the river St. Louis, flowing from the south-west, it has a grand total length of over two thousand miles. With its tributaries it drains over four hundred thousand square miles of country, made up of fertile valleys and plateaux inhabited by a prosperous people, desolate barrens, deep forests, where the foot of man has not yet left its imprint.

Seldom less than two miles in width, it is two and one-half miles wide where it issues from Ontario, and with several expansions which deserve the name of lake it becomes eighty miles in width where it ceases to be considered a river. The influence of the tide is felt as far up as Lake St. Peter, about one hundred miles from the gulf, while it is navigable for sea-going vessels to Montreal, eighty miles farther inland. Rapids impede navigation above this point, but by means of canals continuous communication is obtained to the head of Lake Superior.

If inferior in breadth to the mighty Amazon, if it lacks the length of the Mississippi, if without the stupendous gorges and cataracts of the Yang-tse-Kiang of China, if missing the ancient castles of the Rhine, if wanting the lonely grandeur that still overhangs the Congo of the Dark Continent, the Great River of Canada has features as remarkable as any of these. It has its source in the largest body of fresh water upon the globe, and among all of the big rivers of the world it is the only one whose volume is not sensibly affected by the elements. In rain or in sunshine, in spring floods or in summer droughts, this phenomenon of waterways seldom varies more than a foot in its rise and fall.

The history of the Niagara is so closely interwoven with that of the great "Queen City of the Lakes," Buffalo, that it would seem as though the famous waterway was in the suburb of the city and its greatest scenic attraction. However true this is to-day, it was very far from the case a century ago, for though the site of Buffalo was historic and important, the city, as such, is of comparative recent origin, coming to its own with giant strides in those last decades of the nineteenth century. Writes Mr. Rowland B. Mahany in his excellent chapter on "Buffalo" in The Historic Towns of the Middle States:

Few cities of the United States have a history more picturesque than Buffalo, or more typical of the forces that have made the Republic great. At the time of the adoption of the Federal constitution, in 1787, not a single white settler dwelt on the site of what is now the Queen of the Lakes; and it was not until after the second presidency of Washington, that Joseph Ellicott, the founder of Buffalo, laid out the plan of the town, which he called New Amsterdam.

On February 10, 1810, the "Town of Buffaloe" was created by act of the State Legislature, a name originally given to the locality by the Seneca Indians, who, we shall see, dominated the old Niagara frontier; it is believed that the name came from the animals which visited the neighbouring salt licks; and the name therefore may be much older than any settlement or even camping site. The village of New Amsterdam was now merged into the town of Buffalo, which boasted a newspaper in the second year of its existence, 1811. The story of the following years falls naturally into that of the disastrous war with England from 1812 to 1814, in which Buffalo suffered severely. As Mr. Mahany suggests, the story of Buffalo is characteristically American, and its phases, as such offer an inviting field, but one too wide for full examination in the present history.[2]

[6]The important position of the city with reference to the Great Lakes was very greatly increased with the building of the Erie Canal from 1817 to 1825. It is interesting to recall the fact that it was in reality fear of the possibility of another war with England that caused the deciding vote for the Erie Canal project to be cast in its favour.[3] In the proper place we shall have impressed upon us the great distance that separated the Niagara frontier from the inhabited portion of the Republic at this early period, the great length of the land route and the difficulty of it; it was said to be far more than a cannon was worth to haul it to the frontier during the War of 1812. All this shows very distinctly the early condition surrounding the rise of the metropolis of the Niagara country, and, from being strange that little Buffalo did not grow faster, it is amazing to find such rapid growth during the first twenty-five years of her life.

With the opening of the canal in 1825 a new era dawned; the work of the great land companies in north-eastern New York drew vast armies of people thither, and the canal proved to be the great route for a much longer migration from the seaboard to the further north-west, to Michigan and Wisconsin, as well as to neighbouring Ohio. All this helped Buffalo. Numbers of travellers arriving at the future site of the Queen [7] City of the Lakes at once decided that they could at least go farther and fare very much worse, and so sat down to grow up with the Niagara frontier. The proximity of the Falls had something to do, of course, with bringing increasingly larger numbers of travellers and transients to the Lake Erie village. But it was slow work, this building up a great city, and no doubt the very fact that the stones of the mighty edifice one finds beside that beautiful harbour to-day were laid slowly accounts for the solidity of the structure; Buffalo was not built on a boom.

From James L. Barton's reminiscences, for instance, we have clear pictures of the early struggle for business in this frontier town, which prove it to have been typically American. Mr. Barton owned a line of boats on the Lakes and canal but found it very difficult to find freight for the boats to carry down the State:

A few tons of freight [he writes], was all that we could furnish each boat to carry to Albany. This they would take in, and fill up at Rochester, which place, situated in the heart of the wheat-growing district of Western New York, furnished nearly all the down freight that passed on the canal. Thus we lived and struggled on until 1830. Our population had increased largely, and that year numbered six thousand and thirty-one. In the fall of 1831, I received from Cleveland one thousand bushels of wheat. . . . The next winter I made arrangement with the late Colonel Ira A. Blossom, the resident agent of the Holland Land Company, to furnish storage for all the wheat the settlers should bring in, towards the payment on their land contracts with the company. The whole amount did not exceed three thousand bushels. . . . In 1833 the Ohio canal was completed, which gave us a little more business. Northern Ohio was then the only portion of the great West that had any surplus agricultural products to send to an eastern market. In 1833 a little stir commenced in land operations, which increased the next year, and in 1835 became a perfect fever and swallowed up almost everything else. Nearly every person who had any enterprise got rich from buying and selling land; using little money in these transactions, but paying and receiving in pay, bonds and mortgages to an illimitable amount.

In 1837 the panic affected the young lake city as it did all parts of the land, but by 1840 the population of Buffalo had swelled to over eighteen thousand. The record of growth of the past century is a matter of figures strung on the faith of a great company of active, enterprising, far-sighted business men, until Buffalo ranks among the cities of half a million population, with a future unquestionably secure and brilliant.

The Niagara River is some nineteen hundred feet in width at its mouth here at Buffalo and forty-eight feet deep; the average rate of current here is under six miles per hour, but when south-west gales drive the lake billows in gigantic gulps down the river's mouth the current sometimes races as fast as twelve miles per hour. Old Fort Erie, built here at the mouth of the Niagara immediately after England won the continent from France, in 1764, was formerly the only settlement hereabouts, Black Rock, now part of Buffalo, at the mouth of the Erie Canal, was not settled until near the close of that century. It is believed that five forts have guarded the mouth of this strategic river, all known as Fort Erie. When the people of the opposite sides of the river were in conflict in 1812, Black Rock was the rival of Fort Erie. The large black rock which formed the landing-place of the ferry across the river here, and which gave the hamlet its name, was destroyed when the Erie Canal was built. Black Rock was formally laid out in 1804 and in 1853 was incorporated with the city of Buffalo.

The upper Niagara with its even current and low-lying banks is not specially attractive. Grand Island, two miles below the mouth, divides the river into two narrow arms. This beautiful island, the Indian name of which was Owanunga, so popular to-day as a summering place, is remembered in history especially as the site selected in 1825 for Major M. M. Noah's "New Jerusalem," the proposed industrial centre of the Jews of the New World, but nothing was accomplished on the island itself toward the object in view.

At Buffalo, however, Noah took the title "Judge of Israel," and held a meeting in the old St. Paul's Church, where remarkable initiatory rites took place. In resplendent robes covered by a mantle of crimson silk, trimmed with ermine, the Judge held what he termed "impressive and unique ceremony," in which he read a proclamation to "all the Jews throughout the world," bringing them the glad tidings that on the ancient isle Owanunga "an asylum was prepared and offered to them," and that he did "revive, renew, and establish (in the Lord's name), the government of the Jewish nation, . . . confirming and perpetuating all our rights and privileges, our rank and power, among the nations of the earth as they existed and were recognised under the government of the Judges." Mr. Noah ordered a census of all the Hebrews in the world to be taken and did not forget, incidentally, to levy a tax of about one dollar and a half on every Jew in order to carry on the project. A "foundation stone" was prepared to be erected on the site of the future New Jerusalem; the following inscription was engraved upon it:

At the lower extremity of Grand Island is historic Burnt Ship Bay, made famous, as hereafter related, in the old French War.

The little town of Tonawanda, with its immense lumber interests, and La Salle, famous in history as the building site of the Griffon, elsewhere described, lie opposite Grand Island on the American shore, the former at the mouth of Cayuga Creek. On the opposite shore, a little below the beautiful Navy Island, is the historic town of Chippewa.

Below Navy Island the river spreads out to a width of over two miles; it has fallen twenty feet since leaving Lake Erie, and now gathers into a narrower channel for its magnificent rush to the falls one mile below. In this mile the river drops fifty-two feet, through what are known as the American and Canadian Rapids, on their respective sides of the river.

From a scenic standpoint it is questionable whether any of the delights of Niagara surpass those afforded by this beautiful series of cascades; sightseers are prepared from their earliest days for the magnificent beauty of the Falls themselves, but of the Rapids above little is known until their insidious charm gradually works its way into the heart to remain forever an image of beauty and rapture that cannot be effaced. Guide books will give adequate advice as to the best points of vantage from which to view the various rifts and cascades.[4]

[11]Some years ago [writes Mr. Porter], Colin Hunter, then an Associate, now a Royal Academician, came over from London to paint Niagara. Of all the points of view he selected the one as seen up stream from the head of the Little Brother Island. A temporary bridge was built to it, and here, with a guard at the bridge, so as to be secure from intrusion, he painted his grand view, looking up stream. The upper ledge of rocks, with its long, rapid cascade, was his sky-line; in the foreground were the tumbling Rapids; far to the right of the picture the tops of a few trees appearing on the Canada shore above the waters alone showed the presence of any land. We advise . . . the visitor to clamber over the rocks on the Canadian shore of the Island . . . go out as near the water's edge as possible, and you will appreciate the difference that a few feet in a point of observation may make in what is apparently the same scenery. Just before you reach the foot of the island a gnarled cedar tree and a rock, accessible by leaping from stone to stone, gives you access to a point of observation than which there is nothing more beautiful at Niagara. Do not fail to get this view, for it is the Colin Hunter view, as nearly as you can get it, and you will appreciate the artistic sense of the great painter who chose this incomparable view in preference to the Falls themselves for a reproduction of the very best at Niagara.

Another beautiful point from which to view the Rapids is on Terrapin Rocks, the so-called scenic and geographical centre of Niagara. Here the power of the magnificent river, the "shoreless sea" above you, the clouds for its horizon, grows more impressive with every visit. By day the sight is marvellously impressive; by night, under some circumstances, it is yet more wonderful. Of this night view Margaret Fuller wrote, most feelingly:

After nightfall as there was a splendid moon, I went down to the bridge and leaned over the parapet, where the boiling rapids came down in their might. It was grand, and it was also gorgeous: the yellow rays of the moon made the broken waves appear like auburn tresses twining around the black rocks. But they did not inspire me as before. I felt a foreboding of a mightier emotion to rise up and swallow all others, and I passed on to the Terrapin Bridge. Everything was changed, the misty apparition had taken off its many coloured crown which it had worn by day, and a bow of silvery white spanned its summit. The moonlight gave a poetical indefiniteness to the distant parts of the waters, and while the rapids were glancing in her beams, the river below the Falls was as black as night, save where the reflection of the sky gave it the appearance of a shield of blue steel.

As the Falls of Niagara slowly creep backward in tune to their stupendous recessional toward Lake Erie they encroach more and more on the magnificent domain of the Rapids, nor will their gradual increase in height atone for this savage invasion nor palliate the offence committed. A thousand years more, we are told, and the visitor will view the "Horseshoe" Fall from the upper end of the Third Sister Island, and the marvellous canvas of Colin Hunter will be as meaningless as Hennepin's picture of two centuries and more ago. The American Fall, receding much more slowly than the Horseshoe Fall, will invade the beautiful rapids above Goat Island bridge at a very much later date, for, as we shall see, the greater fall recedes almost as many feet per year as the lesser recedes inches. And in this connection it is interesting to note that if the recession continued to Lake Erie and onward into that lake until the line of fall was a mile long at its crest, with the water falling 336 feet, Victoria Falls in the Zambesi River would still exceed their American rival by sixty-four feet in height!

The accessibility of the Niagara Rapids, because of the fortunate location of the Goat Island group is, in itself, one of the great charms of the region, and this may explain in part the insuppressible desire of early visitors to reach these glorious points of vantage. The view of the rapids from the Goat Island bridge to-day is said to be the source of chief pleasure "to half the visitors to Niagara."[5]

George Houghton's beautiful lines on "The Upper Rapids" express with fine feeling the effect of these racing cascades on the sensitive mind:

When, about 1880, William M. Hunt was commissioned to decorate the immense panels of the Assembly Chamber of the Capitol at Albany, N. Y., he chose, with true artistic feeling, the view of the rapids above Goat Island bridge as the choice picture to represent the great marvel and chief wonder of the Empire State—Niagara. It is generally conceded that Church's Horseshoe Falls takes rank over all other paintings of Niagara, but Colin Hunter's Rapids of Niagara excel any other view of either the Falls, Gorge, or Rapids on canvas to-day.

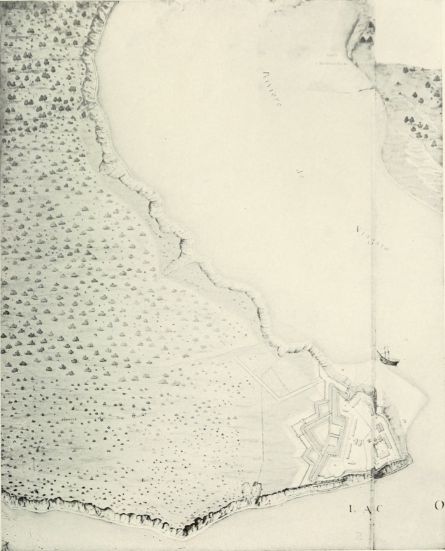

But we must observe here that these Rapids were something aside from beautiful to the French and English officers whose duty it was to defend and supply "the communication" from Fort Frontenac to Fort Chartres; they probably seemed very "horrid," in the old time sense, to those who struggled under the burdens of the ancient portage path. The southern termini of the two pathways—one on either side of the river—were Chippewa and Port Day, respectively. The route from Lewiston to Port Day was evidently the common portage until after the War of 1812 when the Canadian path was opened. A little below what is known as Schlosser Dock stood the French fort guarding this end of their old portage path. Fort du Portage or Little Fort Niagara, built about 1750, nine years before England conquered the region. Near by stands the one famous relic of the old régime, the Old Stone Chimney of Fort du Portage, later a chimney of the English mess-house at Fort Schlosser. As will be noted later Fort du Portage was destroyed by the retreating French, after the capture of Fort Niagara by Sir William Johnson: to guard that end of the portage the English under Colonel Schlosser built Fort Schlosser in 1761. The road occupying the course of the ancient portage does not extend to the river now, but it bears the old name, and on it you may see, not half a mile back, outlines of the earthen works of one of the eleven block-houses built in 1764 by Captain Montresor the first of which was erected on the hill above Lewiston: these block-houses guarded the important roadway from the assaults of Indians such as the famous Bloody Run Massacre of 1763. Frenchman's Landing is the modern name for the cove below the Old Stone Chimney where was the terminus of the earliest portage path guarded by the block-house known as the first Little Fort Niagara. This whole district is now the site [16] of the power-houses and mills that are making Niagara a word to conjure with in the centres of trade as certainly as in the ancient day it was a mesmeric word in the courts and camps of the Old World.

The thunder of Niagara Falls reaches our ears even amid the music of these beautiful Rapids, and we are drawn on to the marvellous group of islands that impinge upon the cataract.

What is commonly known as the Goat Island group consists of the island of that name, containing some seventy acres of land, and sixteen other islands or rocks contiguous thereto. Without undertaking to dispute or defend many of the extravagant assertions made in behalf of Goat Island, to which have been given the titles "Temple of Nature," "Enchanted Isles," "Isle of Beauty," "Shrine of the Deity," "Fairy Isles," etc. it would, I think, be difficult to disprove the statement often made that no other seventy acres on the continent are more interesting than these bearing this homely name. From the standpoint of the artist and naturalist this statement would probably pass unquestioned. The views already alluded to of the American and Canadian rapids to be gained from this delightful vantage point are probably unparalleled. To the botanist Goat Island is a paradise. Sir Joseph Hooker affirmed that he found here a greater variety of vegetation within a given space than he had found in Europe or in America east of the Sierras, and Dr. Asa Gray confirmed the extravagant statement. Wrote Frederick Law Olmsted:

[17]I have followed the Appalachian chain almost from end to end, and travelled on horseback "in search of the picturesque" over four thousand miles of the most promising parts of the continent without finding elsewhere the same quality of forest beauty which was once abundant about the Falls, and which is still to be observed on those parts of Goat Island where the original growth of trees and shrubs has not been disturbed, and where from caving banks trees are not now exposed to excessive dryness at the root.

In a report, prepared by David F. Day for the New York State Reservation Commissioners, we find explained, in part, the notable fertility of this little plot of ground, although the oft-returning misty rain from the Falls, and the fact that Goat Island never experiences the dangers of a "forward" spring have much to do in preserving its beautiful robe of colours:

A calcareous soil enriched with an abundance of organic matter like that of Goat Island would necessarily be one of great fertility. For the growth and sustentation of a forest and of such plants as prefer the woods to the openings it would far excel the deep and exhaustless alluvians of the prairie states.

It would be difficult to find within another territory so restricted in its limits so great a diversity of trees and shrubs and still more difficult to find in so small an area such examples of arboreal symmetry and perfection as the island has to exhibit.

The island received its flora from the mainland, in fact the botanist is unable to point out a single instance of tree, shrub, or herb, now growing upon the island not also to be found upon the mainland. But the distinguishing characteristic of its flora is not the possession of any plant elsewhere unknown, but the abundance of individuals and species, which the island displays. There are to be found in Western New York about 170 species of trees and shrubs. Goat Island and the immediate vicinity of the river near the Falls can show of these no less than 140. There are represented on the island four maples, three species of thorn, two species of ash, and six species, distributed in five genera, of the cone-bearing family. The one species of basswood belonging to the vicinity is also there.

Mr. Day has a catalogue of plants in his report to the Reservation Commissioners, giving 909 species of plants to be found on the Reservation, of which 758 are native and 151 foreign. Wrote Margaret Fuller:

The beautiful wood on Goat Island is full of flowers, many of the fairest love to do homage there. The wake robin and the May apple are in bloom, the former white, pink, green, purple, copying the rainbow of the Falls, and fit it for its presiding Deity when He walks the land, for they are of imperial size and shaped like stones for a diadem. Of the May apple I did not raise one green tent without finding a flower beneath.

Explaining the climatic advantages of the island Mr. Olmsted remarks:

First, the masses of ice which every winter are piled to a great height below the Falls and the great rushing body of ice cold water coming from the northern lakes in the spring prevent at Niagara the hardship under which trees elsewhere often suffer through sudden checks to premature growth. And second, when droughts elsewhere occur, as they do every few years, of such severity that trees in full foliage droop and dwindle and even sometimes cast their leaves, the atmosphere at Niagara is more or less moistened by the constantly evaporating spray of the Falls, and in certain situations bathed by drifting clouds of spray.

It is a very irony of fate that this marvellous gem among the islands of earth could not bear a name befitting its place in the admiration and esteem of a world; it was, I believe, Judge Porter himself that named this beautiful spot "Iris Island," a name altogether fitting in both wealth of suggestion and beauty of association. One John Steadman, remembered as a contractor to widen the old portage path from Lewiston [19] to Fort Schlosser, and former owner of the island under a "Seneca patent," planted some turnips here, we are told, in the year 1770 A.D., and in the following autumn placed here "a number of animals, among them a male goat," to get them out of the reach of the bears and wolves that infested the neighbouring shore near his home two miles up the river. In the spring of 1771 it was found that the severe winter had been too much for all but the "male goat," who, unfortunately, survived the ordeal, and by so doing bids fair to hand his name down through the centuries attached to the most beautiful island in the world. In the Treaty of Ghent, which set our boundary line here, the island bears the name "Iris." Mr. Porter has stated that even if it were desirable to change the name now "it would seem impossible now to do so."[6] Is this the truth? Could not the commissioners who have the matters in hand do a great deal toward inaugurating a change to the old official name that would in the long run prove effective? The present writer is most positive that this could be done and that it is a thing that ought certainly to be attempted immediately. It would be surprising how much the change would be favoured if once attempted, if guide books and maps followed the new nomenclature. The only possible satisfaction that one can have in the present name is in the horrifying reflection that if the male goat had died the island would probably have been "Turnip Island" if not "Colic Island."

[20]Below the islands resound the Falls. Perhaps there is no better method of describing this almost indescribable wonder than by taking the familiar walk about them beginning at the common point of commencement, Prospect Point.

It is important on visiting the Falls for the first time to obtain as good a view as possible, as the first view comes but once. Many are somewhat disappointed with it, since from a distance the Falls give the idea of a long low wall of water, their great height being offset by their great breadth of almost a mile. The best view is from the top of the bank on the Canadian side; but as most of the tourists reach the American side first it is from this standpoint that most visitors gain their first impression. No better vantage ground can be gained on the American side than Prospect Point. Here, placed at the northern end of the American cataract, is the best position to make a study of the geography of Niagara. Stretching from your feet along the line of sight extends the American Fall to a distance of 1060 feet. At the other side of the American Fall is the Goat Island group. This group stretches along the cliff for a distance of 1300 feet more. Beyond this extends the line of the Horseshoe Fall for a further distance of 3010 feet, making in all a total of slightly over a mile. To the right, down the river is the gorge which Niagara has been chiseling and scouring for unnumbered centuries; this chasm extends almost due north for a distance of seven miles to Lewiston. Down the gorge the gaze is uninterrupted for a distance of nearly two miles, almost to the Whirlpool where the river turns abruptly to the left on entering this whirling maelstrom, issuing again almost at right angles to continue its mad plunges. To the left, [21] up the river lie the American Rapids, where the water rushes on in its madness to hurl its volume over the 160 feet of precipice and into the awful chasm below. Just below Prospect Point and somewhat higher in altitude than it, is what has been called Hennepin's View, so named after Father Hennepin, who gave the first written description of the Niagara. Here one sees not only the Horseshoe Fall in the foreground, as at Prospect Point, but the American Fall also, which lies several feet lower than our point of vantage.

Proceeding up the river the next point of interest reached is the steel bridge to Goat Island. The first bridge to this island was constructed by Judge Porter in 1817 about forty rods above the site of the present one. In the spring of the next year this bridge was swept away by the large cakes of ice coming down the river. It was rebuilt at its present site, its projector judging that the added descent of the rapids would so break up the ice as to eliminate any danger to the structure; and the results proved his theory true. This structure stood until 1855 when its place was taken by a steel arch bridge, which served the public until 1900. In that year the present structure authorised by the State of New York took its place.

Looking upon this structure, one wonders how the foundations could possibly have been laid in such an irresistible current of water. First, two of the largest trees to be found in the vicinity were cut down and hewn flat on two sides. A level platform was erected on the shore at the water's edge and on this the hewn logs were placed about eight feet apart, supported on rollers with their shore ends heavily weighted with [22] stone. These logs were then run as far out over the river as possible, and a man walked out on each one armed with an iron pointed staff. On finding a crevice in the rock forming the bottom of the river, these staffs were driven firmly into the rock and then lashed to the ends of the timbers, thus forming a stay to them and furnishing the means necessary for beginning the construction of the crib. The timbers were planked, and the same process was pursued until the island was reached.

While the second bridge was under construction, the famous Indian chieftain and orator, Red Jacket, visited the Falls. The old veteran is said to have sat for a long time watching the process of bridging the angry waters, the transforming power of the white man at work, conquering a force which to him appeared more than able to baffle all the ingenuity of man. On being asked by a bystander what he thought of the work of construction he seemed mortified that the white man's hand should so desecrate these sacred waters; folding his blanket slowly about him, with his eyes fixed upon the works, he is said to have given forth the stereotyped Indian grunt, adding "D——n Yankee!"

Upon this bridge we find one of the best positions, as we have noted, from which to view the Rapids. From the point of their beginning, about a mile above the Falls to the crest of the cliff the descent is over fifty feet. Here, standing upon what seems in comparison but a frail structure, one can realise the grandeur of the Rapids. In the terrible race they seem to be trying to tear away the piers of the bridge which are fretting their current.

These American rivers of ours have their messages, historical, economic, and social, to both reader and loiterer. And, too, are not these streams so very much alive that through the years their personalities remain practically unchanged, while generations of loiterers come and go on forever? Are not the eccentricities of these great living forces forever recurrent, however whimsical they may seem, to us as we stop for our brief instant at the shore?

The word Niagara stands to-day representing power; the most common metaphor used, perhaps, to represent perpetual irresistible force is found in the name Niagara. Now it is admitted that nothing is more interesting than to observe the contradictions noticeable in most strong personalities. View the Niagara from this personal standpoint. I think its most attractive features may be summed up in a catalogue of its eccentric contradictions. It is famous as a waterfall, yet its greatest beauty is to be found in its smallest rapids. Its thundering fall outrivals all other sounds of Nature, yet you can hear a sparrow sing when the spray of the torrent is drenching you; the "noise" of Niagara is often spoken of as the greatest sound ever heard, yet most of the cataract's music has never been heard because it is pitched too low for human ears. Niagara's Whirlpool is a placid, mirrored lake compared to [24] the rapids above and below it and brings from the lips of the majority of sightseers, looking only at the surface of things, words of disappointment. The great message and influence of the foaming cataract and rapids and terrible pool, to all awake to the finer meanings, as has been so beautifully brought out by Mr. Howells, should be one of singular repose. The louder the music the more certain the strange influence of this message of quiet and calm.

Take, for instance, what is so commonly called the roar of Niagara, but which ought to be known as the music of Niagara, first at the Rapids and then the Falls.

There is sweet music in Niagara's lesser rapids. Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer observes, most felicitously:

It is a great and mighty noise, but it is not, as Hennepin thought, an "outrageous noise." It is not a roar. It does not drown the voice or stun the ear. Even at the actual foot of the falls it is not oppressive. It is much less rough than the sound of heavy surf—steadier, more homogeneous, less metallic, very deep and strong, yet mellow and soft; soft, I mean, in its quality. As to the noise of the rapids, there is none more musical. It is neither rumbling nor sharp. It is clear, plangent, silvery. It is so like the voice of a steep brook—much magnified, but not made coarser or more harsh—that, after we have known it, each liquid call from a forest hillside will seem, like the odour of grapevines, a greeting from Niagara. It is an inspiriting, an exhilarating sound, like freshness, coolness, vitality itself made audible. And yet it is a lulling sound. When we have looked out upon the American rapids for many days, it is hard to remember contented life amid motionless surroundings; and so, when we have slept beside them for many nights, it is hard to think of happy sleep in an empty silence.

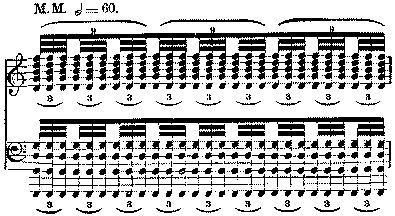

A most original and interesting study of the music of the great Falls was made some years ago in a more or less technical way by Eugene Thayer.[7] It had been this gentleman's theory that Niagara had never been heard as it should be heard, and his mission at the cataract was accomplished when there met his ears, not the "roar," but, rather, a perfectly constructed musical tone, clear, definite, and unapproachable in its majestic proportions; in fact Mr. Thayer affirms that the trained ear at Niagara should hear "a complete series of tones, all uniting in one grand and noble unison, as in the organ, and all as easily recognisable as the notes of any great chord in music." He had heard it rumoured that persons had been known to secure a pitch of the tone of Niagara; he essayed to secure not only the pitch of the chief or ground tone, but that of all accessory or upper tones otherwise known as harmonic or overtones, together with the beat or accent of the Falls and its rhythmical vibrations.

All the tones above the ground tone have been named overtones or harmonics; the tones below are called the subharmonics, or undertones. It will be noticed that they form the complete natural harmony of the ground tone. What is the real pitch of this chord? According to our regular musical notation, the fourth note given represents the normal pitch of diapason; the reason being that the eight-foot tone is the only one that gives the notes as written. According to nature, I must claim the first, or lowest note, as the real or ground tone. In this latter way I shall represent the true tone or pitch of Niagara.

How should I prove all this? My first step was to visit the beautiful Iris Island, otherwise known as Goat Island. Donning a suit of oilcloth and other disagreeable loose stuff, I followed the guide into the Cave of the Winds. Of course, the sensation at first was so novel and overpowering that the question of [26] pitch was lost in one of personal safety. Remaining here a few minutes, I emerged to collect my dispersed thoughts. After regaining myself, I returned at once to the point of beginning, and went slowly in again (alone), testing my first question of pitch all the way; that is, during the approach, while under the fall, while emerging, and while standing some distance below the face of the fall, not only did I ascertain this (I may say in spite of myself, for I could hear but one pitch), but I heard and sang clearly the pitch of all the harmonic or accessory tones, only of course several octaves higher than their actual pitch. Seven times have I been under these singing waters (always alone except the first time), and the impression has invariably been the same, so far as determining the tone and its components. I may be allowed to withhold the result until I speak of my experience at the Horseshoe Fall, and the American Fall proper—it being scarcely necessary to say that the Cave of the Winds is under the smaller cascade, known as the Central Fall.

My next step was to stand on Luna Island, above the Central Fall, and on the west side of the American Fall proper. I went to the extreme eastern side of the island, in order to lose as far as possible the sound of the Central Fall, and get the full force of the larger Fall. Here were the same great ground tone and the same harmonics, differing only somewhat in pitch.

I then went over to the Horseshoe Fall and sat among the Rapids. There it was again, only slightly higher in pitch than on the American side. Not then knowing the fact, I ventured to assert that the Horseshoe Fall was less in height, by several feet, than the American Fall; the actual difference is variously given at from six to twelve feet. Next I went to the Three Sister Islands, and here was the same old story. The higher harmonics were mostly inaudible from the noise of the Rapids, but the same two low notes were ringing out clear and unmistakable. In fact, wherever I was I could not hear anything else! There was no roar at all, but the same grand diapason—the noblest and completest one on earth! I use the word completest advisedly, for nothing else on earth, not even the ocean, reaches anywhere near the actual depth of pitch, or makes audible to the human ear such a complete and perfect harmonic structure.

Remembering always that the actual pitch is four octaves lower, here are the notes which form this matchless diapason:

Mrs. Van Rensselaer tells us there is yet another music at Niagara that must be listened for only on quiet nights. It is like the music of an orchestra so very far away that its notes are attenuated to an incredible delicacy and are intermittently perceived, as though wafted to us on variable zephyrs.

It is the most subtle, the most mysterious music in the world. What is its origin? Such fairy-like sounds are not to be explained. Their appeal is to the imagination only. They are so faint, so far away, that they almost escape the ear, as the lunar bow and the fluted tints of the American Fall almost escape the eye. And yet we need not fear to lose them, for they are as real as the deep bass of the cataracts.

Whether it be the resounding waterfall producing this wondrous harmony of the floods, or the most charming choral of the Rapids, the music of Niagara on the mind properly adjusted and attuned must create a most profound impression of repose. The exception to this rule, most [28] terrible to contemplate, is certainly to be found in the cases of the unfortunates whose minds are so distraught or unbalanced that this same call of the waters acts like poison and lures them to death.

I still think [wrote Mr. Howells in his most delightful sketch, Niagara, First and Last] that, above and below the Falls, the Rapids are the most striking features of the spectacle. At least you may say something about them, compare them to something; when you come to the cataract itself you can say nothing; it is incomparable. My sense of it first, and my sense of it last, was not a sense of the stupendous, but a sense of beauty, of serenity, of repose.

In her beautiful description, given elsewhere in our story, Margaret Fuller explains the effect of the Rapids by moonlight on the heart of one who, during the day, had passed through the familiar throb of disappointment in the great spectacle at Niagara.

Now I take it one must see in Niagara this element of repose or find in it something less than was hoped for. To one who expects an ocean pouring from the moon, a rush of wind and foam like that to be met with only in the Cave of the Winds, there is bound to come that common feeling that the fact is not equal to the picture imagination had previously created. Take the Whirlpool; seen from the heights above, it

has that effect of sculpturesque repose [writes Mr. Howells], which I have always found the finest thing in the Cataract itself. From the top the circling lines of the Whirlpool seemed graven in a level of chalcedony. . . . I have no impression to impart except this sense of its worthy unity with the Cataract in what I may call its highest ęsthetic quality, its repose.[8]

All this is most impressively true of the central wonder of the entire [29] spectacle, the Falls themselves. That mighty flood of water, reborn as it dies, forms a marvellous spectacle. Writes Mrs. Schuyler Van Rensselaer:

Very soon we realise that Niagara's true effect is an effect of permanence. Many as are its variations, it never alters. It varies because light and atmosphere alter. Tremendous movement thus pauseless and unmodified gives, of course, a deeper impression of durability than the most imposing solids. . . . As soon as this fact is felt, the Falls seem to have been created as a voucher for the permanence of all the world.[9]

But how conform this repose and spirit of permanency with the echoing tones of that never-ending, never-satisfied dominant chord? How reconcile the repose of those dropping billows with the tantalising unrest of that for ever incomplete, unfinished recessional that has been playing down this gorge since, perhaps, darkness brooded over the deep—that seems to await its fulfilment in the thunders of Sinai at that Last Day?

And what could be more human than this in any river—a seeming calm with over it all a never-ending cry of unrest, of wonder, of unsatisfied longing never to find repose until in that far resting-place of which Augustine thought when he wrote:

Across the American Rapids lies the Goat Island group which divides the waters into the two falls. Goat Island is about half a mile long and half as wide at its broadest part, but slopes to a point at its eastern extremity. Its area is about seventy acres. Besides this there are a [30] number of smaller islands and rocks varying in diameter from four hundred feet to ten feet. Of these smaller islands five are connected with Goat Island by bridges, as are also the Terrapin Rocks.

At the end of the first bridge is situated Green Island, named after the first president of the Board of Commissioners of the New York Reservation. The former name was Bath Island because of the "old swimming hole"—the only place where one could dip in the fierce current of Niagara without danger. Just a short distance above Green Island are two small patches of land called Ship Island and Bird Island from supposed resemblances to these objects in general contour, the tall leafless trees in winter supposed to be suggestive of masts. These islands were formerly both connected with Goat Island by bridges; one, known as "Lover's Bridge," from its romantic name was so greatly patronised that both bridges were destroyed by the owners on account of danger.

On Green Island formerly stood the immense Porter paper-mill, which not only contributed its own ugliness to the beautiful prospect but also ran out into the current long gathering dams for the purpose of collecting water. All this was removed when the State of New York assumed control.

Passing from the bridge and ascending the steps which lead to the top of the bank, the shelter house is reached. All around and, in fact, covering nearly all the island, is the primeval forest in its ancient splendour—fit companion of the Falls, which defy the puny power of man.

Occasional glimpses of the river may be had through the dense foliage as one proceeds to Stedman Bluff, where one of the grandest panoramas to be seen anywhere on earth bursts upon the view. Here one appreciates the beauty of the American Fall better than at Prospect Point. Turning towards the American shore stone steps lead down to the water's edge, and thence a small bridge spans the stream separating Goat Island and Luna Island, so called from the fact that it has been considered the best place from which to view the lunar bow. The small stream dividing these islands in its plunge over the precipice forms the "Cave of the Winds." Half-way across Luna Island is to be seen a large rock on whose face have been carved by an unknown hand the following lines:

The author of the sentiment is unknown, but no one has more truly voiced the spirit of the great cataract. From the edge of the cliff on Luna Island is to be obtained the finest view down the gorge. Along the front of the American Fall are to be seen the immense masses of wave-washed rocks which have fallen from the cliff above. From rock to rock stretch frail wooden bridges, the more important of which lead to the cave.

Luna Island is the last point which one can reach from Goat Island toward the American shore. Proceeding toward the Canadian Fall, one reaches at a short distance the Biddle Stairs. Here a break in the foliage reveals a grand view down the gorge with the Canadian Fall directly in front. A stairway leads to a wooden building down which runs a spiral stairway to the rocks below. This stairway received its name [32] from Nicholas Biddle, of old National Bank fame, who proposed this means of reaching the rocks below and offered a contribution for its construction. The offer was rejected, but his name was given to the structure. A trip to the rocks below this point is well worth while, difficult though it be; the descent of the spiral stairway is eighty feet. Turning to the right one comes out upon a ledge of rock with the roaring waters below and the line of the cliff above, along the top of which objects appear at only half their real size. Passing around a short curve there bursts upon one's view the fall which forms the Cave of the Winds—a most beautiful sheet of water. The passage of the cave can hardly be described by the pen. Here one is assailed on all sides by fierce storms and clouds of angry spray. The cave seems at first dark and repelling, for in this maddening whirl of wind and water one is at first almost blinded; but as soon as the eye becomes accustomed to the darkness, it can follow the graceful curve of the water to where it leaves the cliff above. The dark, forbidding, terraced rocks are seen dripping with water. The passage of the cave is too exciting to be essayed by persons with weak hearts, but the return across the rocks in front of it on a bright day is genuinely inspiring. Here the symbol of promise is brought down within one's very reach; above, around, on all sides are to be seen colours rivalling the conception of any artist—whole circles of bows, quarter circles, half circles, here within one's very grasp. The far fabled pot of gold is here a boiling, seething mass of running, shimmering silver. If possible, more glorious than all else, up above, along the sky-line, there appears the shining crest of the American Fall, glimmering in the sunlight like the silvery range of some snow-covered mountains.

In size the cave is about one hundred feet wide, a hundred feet deep, and about one hundred and sixty feet high. At one point in the cave, on a bright day, by standing in the very edge of the spray, one becomes the centre of a complete circle of rainbows, an experience probably unequalled elsewhere.

About half-way between the stairway and the cave is the point from which, in 1829, Sam Patch made his famous leap, elsewhere described.

On the side of the Horseshoe Fall is to be found a fine position from which to view the mighty force of the greater mass of waters. For some distance along the front of the fall immense masses of rock have accumulated. The trip over these rocks is fraught with danger and is taken by very few. For those who care to take the risk, the sight is well worth the effort. Just above at the crest are Terrapin Rocks, where formerly stood Terrapin Tower. Professor Tyndall went far out beyond the line of Terrapin Rocks to a point which has been reached by very few of the millions of visitors to this shrine. Passing along the cliff toward Canada, Porter's Bluff is soon reached, which furnishes one of the grandest views of the Horseshoe Fall. Fifty years ago, from this point one could see the whole line of the graceful curve of the Horseshoe; since that time the rapid erosion in the middle of the river (where the volume is greatest) has destroyed almost all trace of what the name suggests. The sides meet now at a very acute angle, the old contour having been entirely destroyed.

[34]One of the most interesting experiments conducted under these great masses of falling water was essayed by the well-known English traveller Captain Basil Hall in 1827. It seems that Babbage and Herschel had said that there was reason to expect a change of elastic pressure in the air near a waterfall. Bethinking himself of the opportunity of testing this theory at Niagara during his American tour, Captain Hall secured a mountain barometer of most delicate workmanship for this specific purpose. In a letter to Professor Silliman the experimenter described his experience as follows, the question being of interest to every one who has attempted to breathe when passing behind any portion of this wall of falling water:

I think you told me that you did not enter this singular cave on your late journey, which I regret very much, because I have no hope of being able to describe it to you. In the whole course of my life, I never encountered anything so formidable in appearance; and yet, I am half ashamed to say so, I saw it performed by many other people without emotion, and it is daily accomplished by ladies, who think they have done nothing remarkable.

You are perhaps aware that it is a standing topic of controversy every summer by the company at the great hotels near the Falls, whether the air within the sheet of water is condensed or rarefied. I have therefore a popular motive as well as a scientific one, in conducting this investigation, and the result, I hope, will prove satisfactory to the numerous persons who annually visit Niagara.

As a first step I placed the barometer at a distance of about 150 feet from the extreme western end of the Falls, on a flat rock as nearly as possible on a level with the top of the "talus" or bank of shingle lying at the base of the overhanging cliff, from which the cataract descends. This station was about 30 perpendicular feet above the pool basin into which the water falls.

[35]The mercury here stood at 29.68 inches. I then moved the instrument to another rock within 10 or 12 feet of the edge of the fall, where it was placed, by means of a levelling instrument, exactly at the same height as in the first instance.

It still stood at 29.68 and the only difference I could observe was a slight continuous vibration of about two or three hundredths of an inch at intervals of a few seconds.

So far, all was plain sailing; for, though I was soundly ducked by this time, there was no particular difficulty in making these observations. But within the sheet of water, there is a violent wind, caused by the air carried down by the falling water, and this makes the case very different. Every stream of falling water, as you know, produces more or less a blast of this nature; but I had no conception that so great an effect could have been produced by this cause.

I am really at a loss how to measure it, but I have no hesitation in saying that it exceeds the most furious squall or gust of wind I have ever met with in any part of the world. The direction of the blast is generally slanting upwards, from the surface of the pool, and is chiefly directed against the face of the cliff, which being of a friable, shaly character, is gradually eaten away so that the top of the precipice now overhangs the base 35 or 40 feet and in a short time I should think the upper strata will prove too weak for the enormous load of water, which they bear, when the whole cliff will tumble down.

These vehement blasts are accompanied by floods of water, much more compact than the heaviest thunder shower, and as the light is not very great the situation of the experimenter with a delicate barometer in his hand is one of some difficulty.

By the assistance of the guide, however, who proved a steady and useful assistant, I managed to set the instrument up within a couple of feet of the "termination rock" as it is called, which is at the distance of 153 feet from the side of the waterfall measured horizontally along the top of the bank of shingle. This measurement, it is right to mention, was made a few days afterward by Mr. Edward Deas-Thompson of London, the guide, and myself with a graduated tape.

While the guide held the instrument firmly down, which required nearly all his force, I contrived to adjust it, so that the spirit level on the top indicated that the tube was in the [36] perpendicular position. It would have been utterly useless to have attempted any observation without this contrivance. I then secured all tight, unscrewed the bag, and allowed the mercury to subside; but it was many minutes before I could obtain even a tolerable reading, for the water flowed over my brows like a thick veil, threatening to wash the whole affair, philosophers and all, into the basin below. I managed, however, after some minutes' delay to make a shelf or spout with my hand, which served to carry the water clear of that part of the instrument which I wished to look at and also to leave my eyes comparatively free. I now satisfied myself by repeated trials that the surface of the mercurial column did not rise higher than 29.72. It was sometimes at 29.70 and may have vibrated two or three hundredths of an inch. This station was about 10 or 12 feet lower than the external ones and therefore I should have expected a slight rise in the mercury; but I do not pretend to have read off the scale to any great nicety, though I feel quite confident of having succeeded in ascertaining that there was no sensible difference between the elasticity of the air at the station on the outside of the Falls and that, 153 feet within them.

I now put the instrument up and having walked back towards the mouth of this wonderful cave about 30 feet, tried the experiment again. The mercury stood now at 29.68, or at 29.70 as near as I could observe it. On coming again into the open air I took the barometer to one of the first stations, but was much disappointed though I cannot say surprised to observe it full of air and water and consequently for the time quite destroyed.

My only surprise, indeed, was that under such circumstances the air and water were not sooner forced in. But I have no doubt that the two experiments on the outside as well as the two within the sheet of water were made by the instrument when it was in a correct state: though I do not deny that it would have been more satisfactory to have verified this by repeating the observations at the first station.

On mentioning these results to the contending parties in the controversy, both asked me the same question, "How then do you account for the difficulty in breathing which all persons experience who go behind the sheet of water?" To which I replied: "That if any one were exposed to the spouts of half a [37] dozen fire engines playing full in his face at the distance of a few yards, his respiration could not be quite free, and for my part I conceived that this rough discipline would be equally comfortable in other respects and not more embarrassing to the lungs than the action of the blast and falling water behind this amazing cataract."

It is almost impossible to conceive of the immense mass of water tumbling over this precipice. It has been estimated in tons, cubic feet, and horse-power, but the figures are so large as to stagger the human mind. Out there at the apex of the angle, the water, over twenty feet deep, is drawn from almost half a continent, forming a picture to make one's nerves thrill with awe and delight, where the international boundary line swings back and forth as the apex of the angle formed sways from side to side.

Just off the shore of the island are seen Terrapin Rocks. Why this name was applied is uncertain. These rocks are scattered in the flood to the very brink of the fall and in the titanic struggle with the rush of waters seem hardly able to maintain their position. Upon these rocks on the very brink of the Falls in 1833 was erected, by Judge Porter, Terrapin Tower, for many years one of the centres visited by every person journeying to the Falls. From its summit could be seen the wild rapids rushing on toward the precipice; below shimmering green of the fall. Down, far down, in the depths beneath was the boiling, seething caldron, from which arose beautiful columns of spray. From this position, forty-five feet above the surface of the water, probably a more comprehensive view of the many features of Niagara could be obtained than from any other point. Forty years later it was blown up, [38] not because it was unsafe, as alleged, but that it might not prove a rival attraction to Prospect Point. Recently suggestions have been made looking toward the restoration of this ancient landmark, but no definite action has been taken.

Over a half-century ago, almost opposite this tower on the Canadian side, was to be seen the immense Table Rock hanging far out over the current below. On the 25th of June, 1850, this large mass of rock fell. Fortunately the fall occurred at noon with no loss of life; it was one of the greatest falls of rock known to have taken place at the cataract, for the dimensions of the rock were two hundred feet long, sixty feet wide, and a hundred feet deep. Like the roar of muffled thunder the crash was heard for miles around.

It was from the Terrapin Rocks to the Canadian side that Blondin wished to stretch his rope, elsewhere described, and it was over the very centre of Niagara's warring powers he desired to perform his daring feat, looking down upon that shimmering guarded secret of the "Heart of Niagara." The Porters, who owned Goat Island, however, refused to become parties to what they considered an improper exposure of life and Blondin stretched his cable farther down the river, near the site of the crescent steel arch bridge.

Standing upon these rocks and looking out over that hurrying mass of waters, it seems almost impossible to imagine any power being able to stop them; but on the 29th of March, 1848, the impossible happened, the Niagara ran dry. From the American shore across the rapids to Goat Island one could walk dry-shod. From Goat Island and the Canadian shore the waters were contracted to a small stream flowing over the centre of [39] what was then the Horseshoe; only a few tiny rivulets remained falling over the precipice at other points. The cause of this unnatural phenomenon was wind and ice. Lake Erie was full of floating ice. The day previous the winds had blown this ice out into the lake. In the evening the wind suddenly changed and blew a sharp gale from exactly the opposite direction, driving the mass of ice into the river and gorging it there, thus cutting off almost the whole water supply, and in the morning people awoke to find that the Niagara had departed. The American Fall was no more, the Horseshoe was hardly a ghost of its former self. Gone were the rapids, the fighting, struggling waters. Niagara's majestic roar was reduced to a moan. All day people walked on the rock bed of the river, although fearful lest the dam formed at its head should give way at any moment. By night, the warmth of the sun and the waters of the lake had begun to make inroads on the barrier and by the morning of the next day Niagara had returned in all its grandeur.

However cold Niagara's winter may be, the moan of falling water here can always be heard, though at times the volume is very small. The winter scenes here often take rank in point of wonder and beauty with the cataract itself. When the river is frozen over below the Falls the phenomenon is called an "Ice Bridge," the blowing spray sometimes building a gigantic sparkling mound of wonderful beauty. The island trees above the Falls, covered by the same spray, assume curiously beautiful forms which, as they glitter in the sun, turn an already wonder-land into a strange fairyland of incomparable whiteness and glory.

[40]A short distance up the river along the shore a position just opposite the apex of the Falls is reached. Here, along the shore of the island, the waters are comparatively shallow, but toward the Canadian shore races the current which carries fully three fourths of Niagara's volume. Out in the very midst of the current is a small speck of land, all that is now left of what was once Gull Island, so named from its having been a favourite resting place for these birds, which can hardly find a footing now on its contracted shores. From what can be learned of the past history of this island, it must have occupied about two acres three quarters of a century ago. Its gradual disappearance shows to what degree the mighty forces of Niagara are removing all obstacles placed in their path. Goat Island is gradually suffering the same fate. At points the shore line has encroached upon the island to a distance of twenty feet in a half-century. At this point the carriage road used to run out beyond the present edge of the bluff.

Passing on along the shore of the island, Niagara's scenery is present everywhere. At quite a distance up stream the Three Sister Islands are reached. These islands were named from the three daughters of General P. Whitney, they being the first women to visit them, probably in winter when the waters were low.

To the first Sister Island leads a massive stone bridge. From this bridge is to be obtained a fine view of the Hermit's Cascade beneath. This little fall receives its name from having been the favourite bathing place of the Hermit of Niagara, a strange half-witted young Englishman by the name of Francis Abbott who lived in solitude here for [41] two years preceding his death by drowning in 1831, during his sojourn at the Falls.

These three islands are replete with small bits of scenery and overflowing with beauty. In them are to be found the smaller attractions of Niagara; not so much of the stern majesty and awful grandeur, but smaller and more comprehensible features come before the view following each other in rapid succession. On the second Sister Island is one point which should be visited by every one. Just before reaching the bridge to third Sister Island, by turning to the right and proceeding along a somewhat difficult path for a short distance one comes to a point at the water's edge and finds lying right below him the boiling waters with their white, feathery spray; here also is the small cataract between the second and third islands fed by the most rapid although small stream of Niagara. From this point is to be obtained one of the most varied of scenic effects of any point at the Falls. The scenery from the third Sister must be seen to be appreciated. From its upper end one looks directly at the low cliff which forms the first descent of the Rapids. Here the waters start from the peaceful stream above on their maddening race for the Falls. Out along the line of the cliff the waters deepen and increase in rapidity toward the Canadian shore. Just below this ledge, probably three hundred feet from the head of the island, the current is directed against some obstruction which causes it to spout up into the air, causing what is called the Spouting Rock.

Many have been the changes wrought by the waters themselves since white men knew the Falls; but a thousand years hence the visitor to Niagara [42] will behold the main fall not from Terrapin Rocks or Porter's Bluff, but from this third Sister Island. The Rapids then shall have almost entirely disappeared, but their beauty will be compensated for by the additional grandeur of the fall itself. The gorge will have widened and the fall itself shall have added fifty feet to its height, making it two hundred feet high. Third Sister Island should be gone over thoroughly, for it offers some of the finest views, especially of colouring, above the Falls, and many of them.

Niagara owes its sublime array of colour to the purity of its water. Nothing finer has been written on this subject than the words of the artist Mrs. Van Rensselaer, whom we quote:

To this purity Niagara owes its exquisite variety of colour. To find the blues we must look, of course, above Goat Island, where the sky is reflected in smooth if quickly flowing currents. But every other tint and tone that water can take is visible in or near the Falls themselves. In the quieter parts of the gorge we find a very dark, strong green, while in its rapids all shades of green and grey and white are blended. The shallower rapids above the Falls are less strongly coloured, a beautiful light green predominating between the pale-grey swirls and the snowy crests of foam—semi-opaque, like the stone called aquamarine, because infused with countless air-bubbles, yet deliciously fresh and bright. The tense, smooth slant of water at the margin of the American fall is not deep enough to be green. In the sunshine it is a clear amber, and when shadowed, a brown that is darker, yet just as pure. But wherever the Canadian fall is visible its green crest is conspicuous. Far down-stream, nearly two miles away, where the railroad-bridge crosses the gorge, it shows like a little emerald strung on a narrow band of pearl. Its colour is not quite like that of an emerald, although the term must be used because no other is more accurate. It is a [43] purer colour, and cooler, with less of yellow in it—more pure, more cool, and at the same time more brilliant than any colour that sea-water takes even in a breaking wave, or that man has produced in any substance whatsoever. At this place, we are told, the current must be twenty feet deep; and its colour is so intense and so clear because, while the light is reflected from its curving surface, it also filters through so great a mass of absolutely limpid water. It always quivers, this bright-green stretch, yet somehow it always seems as solid as stone, smoothly polished for the most part, but, when a low sun strikes across it, a little roughened, fretted. That this is water and that the thinnest smoke above it is water also, who can believe? In other places at Niagara we ask the same question again.

From a distance the American fall looks quite straight. When we stand beside it we see that its line curves inward and outward, throwing the falling sheet into bastion-like sweeps. As we gaze down upon these, every change in the angle of vision and in the strength and direction of the light gives a new effect. The one thing that we never seem to see, below the smooth brink, is water. Very often the whole swift precipice shows as a myriad million inch-thick cubes of clearest glass or ice or solidified light, falling in an envelope of starry spangles. Again, it seems all diamond-like or pearl-like, or like a flood of flaked silver, shivered crystal, or faceted ingots of palest amber. It is never to be exhausted in its variations. It is never to be described. Only, one can always say, it is protean, it is most lovely, and it is not water.

Then, as we look across the precipice, it may be milky in places, or transparent, or translucent. But where its mass falls quickly it is all soft and white—softer then anything else in the world. It does not resemble a flood of fleece or of down, although it suggests such a flood. It is more like a crumbling avalanche, immense and gently blown, of smallest snowflakes; but, again, it is not quite like this. Now we see that, even apart from its main curves, no portion of the swiftly moving wall is flat. It is all delicately fissured and furrowed, by the broken edges of the rock over which it falls, into the suggestion of fluted buttresses, half-columns, pilasters. And the whiteness of these is not quite white. Nor is it consistently iridescent or opalescent. Very faintly, elusively, [44] it is tinged with tremulous stripes and strands of pearly grey, of vaguest straw, shell-pink, lavender, and green—inconceivably ethereal blues, shy ghosts of earthly colours, abashed and deflowered, we feel, by definite naming with earthly names. They seem hardly to tinge the whiteness; rather, to float over it as a misty bloom. We are loath to turn our eyes from them, fearing they may never show again. Yet they are as real as the keen emerald of the Horseshoe.[10]

One should walk through the New York State Reservation, which extends for some distance above the commencement of the Rapids, to get a more complete view of the scenery above the Falls, the wooded shores of Goat Island, the swiftly moving waters, the broad river, the beginning of the Canadian Rapids, and the Canadian shore in the distance. On up the river at a distance are to be seen those forest-clad shores of Navy Island and Grand Island.

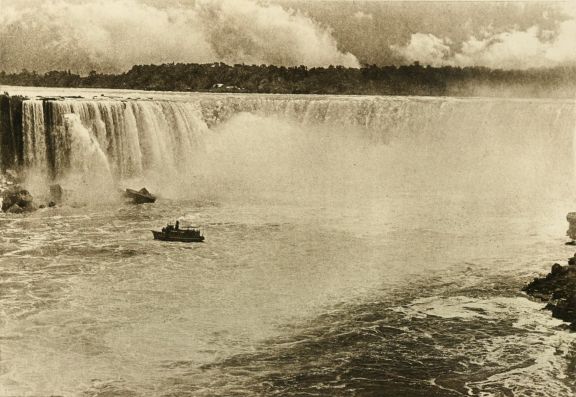

On the Canadian side of the river, after crossing the steel arch bridge just below the Falls, beautiful Victoria Park is first reached. From this position a new and entirely different view of the American Fall is obtained from almost directly in front. Turning and going up the river a fine view of the Horseshoe is obtained from a distance. Just opposite the American Fall is Inspiration Point, from which the best view of the Falls is to be obtained. From here one can watch the little Maid of the Mist as she makes her trips through the boiling waters below.

On up the river one wanders, past Goat Island, whose cliff is seen from directly in front. Just before reaching the edge of the Horseshoe the [45] position of old Table Rock is seen. Little is left of this old and once famous point for observing Niagara's wonders. Several different falls of immense masses of rock, one of which has been mentioned, have reduced it to its present state. Here the Indian worshipped the Great Spirit of the Falls, gazing across at his supposed home on Goat Island; and here comes the white man to look upon the wonders of that mighty cataract with a feeling almost akin to that of his red brother. Here one could stand with the maddening waters rushing beneath, the Falls near at hand, its incessant roar assailing the ears while the spray was wafted all round. Little wonder that the red man worshipped, or that the white man looks on with feelings of awe, admiration, and wonder.