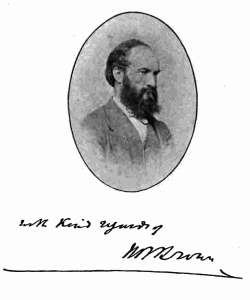

Portrait of Dr. Robert Brown

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org

Title: The Adventures of John Jewitt

Only Survivor of the Crew of the Ship Boston During a Captivity of Nearly Three Years Among the Indians of Nootka Sound in Vancouver Island

Author: John Rodgers Jewitt

Editor: Robert Brown

Release Date: November 14, 2011 [eBook #38010]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

***START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE ADVENTURES OF JOHN JEWITT***

| Note: | Images of the original pages are available through Internet Archive. See http://www.archive.org/details/adventuresofjohn00jewiuoft |

A sad interest attaches to this little book. Although published after his death, and therefore deprived of his final revision, it was not the last work which Dr. Robert Brown did. His manuscript was actually completed many months ago, but at his own request it was returned to him to receive a last careful overhaul at his hands. This revision had been practically finished, and the MS. lay ready uppermost among the papers in his desk, where it was found after his death. Dr. Brown died on the morning of the 26th of October, 1895, working almost to his last hour. Before the leader he had written for the Standard on the evening of the 25th had come under the eyes of its readers, the hand that had penned it was cold in death. Between the evening and the morning he went home. He was only fifty-three, but "a righteous man, though he die before his time, shall be at rest."

And in one sense Dr. Brown needed rest—ay, even this last and sweetest rest of all. His life had been one of unremitting work—work well done, which the busy, hurrying world mostly heeded not, knowing naught of the hand that did it. Some twenty years ago, when I first knew him, he was a fair, stalwart Northerner, full of vigour, mirthful also, and apparently looking out on the voyage of life with the confident, joyous eye of one who[6] felt he had strength within him to conquer. His latter days were saddened by incessant toil, performed in weakness of body and jadedness of brain, and by the feeling that his best work, the work into which he put his rich stores of knowledge, was neither recognised nor requited as it should have been.

To a sensitive man the daily wear and tear of a journalist's life in London is often murderous, always exhausting—and Dr. Brown was very sensitive. Beneath the genial exterior, which seemed to indicate a careless, light-hearted spirit, lay great depths of feeling, and a tenderness that shrank from expressing itself. The man was too proud and self-restrained to betray these depths even to those nearest and dearest to him. This was at once a nobility in him and a weakness. Had he opened his heart more, he would have chafed and fretted less, little annoyances would not have become mountain loads of care. But the truth is, Dr. Brown was not cut out for the life of an everyday journalist, either by training, habits, or disposition. The ideal post for him would have been that of a professor at some great university, where he could have had abundant leisure to pursue his favourite studies, where young men would have surrounded him and listened with delight to the outpouring of the wealth of lore with which his capacious intellect was stored. His lot was otherwise cast, and he accepted it manfully, battling with his destiny to his last hours, grimly and in silence of soul, intent only on one thing, to lift his children clear above the necessity for treading the same rough road upon which he had worn himself out.

Other and worthier hands than mine may trace, it is to be hoped, the story of his life, his expeditions in[7] America and Greenland, and his many literary labours not only in popularising scientific subjects, with a thoroughness and attractiveness too little recognised, but in walks apart where the multitude could not judge him. My dominant feeling about him for many years has been one of regret that he should be wearing his life away so fast. He never learned to play; to be completely idle for a day even became, latterly, irksome, almost irritating, to him. His fingers itched to hold the pen, to handle a book. Although in earlier times he could enjoy a brief holiday, he ever mixed work with his pleasure; could, indeed, accept no pleasure which did not imply work somewhere close to his hand. Thus his various journeys to Morocco, ostensibly taken, at any rate the earlier of them, to escape from all kinds of work, and from the sight of the day's newspaper, ended in his becoming the foremost authority in Great Britain upon the literature, present social condition, and probable future of that perishing country. The acquisition of this knowledge was all in his day's enjoyment.

The testimony of the introduction and notes to this little book is enough to prove how thoroughly and conscientiously everything that Dr. Brown undertook was done. The question of payment rarely entered into his calculations. Some of his very best work was done for nothing, because he loved to do it. Witness his edition of Leo Africanus, prepared for the Hakluyt Society, and his innumerable memoirs to the various learned Societies of which he was a member.

Few of Dr. Brown's London friends were aware that his attainments as a scientific botanist were of the highest order. Yet in this department of science alone he had written thirty papers and reports, besides an[8] advanced text-book of Botany (published by William Blackwood and Sons), before the summer of 1872, when he was only thirty years of age. These were entirely outside his contributions to general literature on that and other subjects, already at that date numerous; and if we add to the list the various reports, essays, memoranda contributed by him to the Royal Physical Society of Edinburgh, of which he was President, to the Royal Geographical Society, of whose Council he was a member at his death, and to numerous other bodies, as well as to scientific and popular journals, on geographical, geological, and zoological subjects, from first to last the total mounts to several hundreds. In these branches of science his heart lay always, but he laboured for his daily bread and to give to him that needed.

The portrait forming the frontispiece to this volume is from a photograph of Dr. Brown taken in 1870, just after his return from his last expedition to Greenland, and represents him much as he looked when, some years later, he first came to London, after failing to obtain the chair of Botany in Edinburgh University. That was a disappointment which he cannot be said ever to have entirely surmounted. The memory of it to some extent kept him aloof from his fellow-labourers in the world of journalism. What work he had to do he did loyally, manfully, and with the most scrupulous care; but he lived a man apart, more or less, from his first coming among us to the end. In his family circle, and where he was really known, his loss has brought a great sorrow.

London, February 16, 1896.

| PAGE | |

| INTRODUCTION. By Dr. Robert Brown | 13 |

| CHAPTER I | |

| Birth, Parentage, and Early Life of the Author | 43 |

| CHAPTER II | |

| Voyage to Nootka Sound | 53 |

| CHAPTER III | |

| Intercourse with the Natives—Maquina—Seizure of the | |

| Vessel and Murder of the Crew | 58 |

| CHAPTER IV | |

| Reception of Jewitt by the Savages—Escape of Thompson—Arrival | |

| of Neighbouring Tribes—An Indian Feast | 70 |

| CHAPTER V | |

| Burning of the Vessel—Commencement of Jewitt's Journal | 83 |

| CHAPTER VI | |

| Description of Nootka Sound—Manner of Building | |

| Houses—Furniture—Dresses | 95 |

| CHAPTER VII | |

| Appearance of the Natives—Ornaments—Otter-Hunting—Fishing—Canoes | 112 |

| [10] | |

| CHAPTER VIII | |

| Music—Musical Instruments—Slaves—Neighbouring | |

| Tribes—Trade with these—Army | 129 |

| CHAPTER IX | |

| Situation of the Author—Removal to Tashees—Fishing Parties | 142 |

| CHAPTER X | |

| Conversation with Maquina—Fruits—Religious Ceremonies—Visit | |

| to Upquesta | 156 |

| CHAPTER XI | |

| Return to Nootka (Friendly Cove)—Death of Maquina's | |

| Nephew—Insanity of Tootoosch—An Indian Mountebank | 172 |

| CHAPTER XII | |

| War with the A-y-Charts—A Night Attack—Proposals to | |

| Purchase the Author | 185 |

| CHAPTER XIII | |

| Marriage of the Author—His Illness—Dismisses his | |

| Wife—Religion of the Natives—Climate | 198 |

| CHAPTER XIV | |

| Arrival of the Brig "Lydia"—Stratagem of the Author—Its Success | 223 |

| APPENDIX | |

| I. The "Boston's" Crew | 247 |

| II. War-Song of the Nootka Tribe | 248 |

| III. A List of Words | 249 |

| INDEX | 253 |

| PAGE | |

| Portrait of Dr. Robert Brown (1870) | Frontispiece |

| Dr. Brown's "Boy" | 14 |

| Port San Juan Indians | 16 |

| Ohyaht Indian | 24 |

| Indian Encampment near the Landing-stage, Esquimault | 33 |

| Habitations in Nootka Sound (Temp. 1803) | 97 |

| Interior of a Habitation in Nootka Sound | 103 |

| Nootka Sound Indians | 111 |

| Indian Canoes, Victoria, V. I. (Temp. 1863) | 125 |

| Uk-Lulac-Aht Indian | 135 |

| Salmon Wear near the Indian Village of Quamichan, V. I. | 149 |

| Callicum and Maquilla, Chiefs of Nootka Sound (Temp. 1803) | 159 |

| Indian Chief's Grave (Temp. 1863) | 209 |

Many years ago—when America was in the midst of war, when railways across the continent were but the dream of sanguine men, and when the Pacific was a faraway sea—the writer of these lines passed part of a pleasant summer in cruising along the western shores of Vancouver Island. Our ship's company was not distinguished, for it consisted of two fur-traders and an Indian "boy," and the sloop in which the crew and passengers sailed was so small, that, when the wind failed, and the brown folk ashore looked less amiable and the shore more rugged than was desirable, we put her and ourselves beyond hail by the aid of what seamen know as a "white ash breeze." Out of one fjord we went, only to enter another so like it that there was often a difficulty in deciding by the mere appearance of the shore which was which. Everywhere the dense forest of Douglas fir and Menzies spruce covered the country from the water's edge to the summit of the rounded hills which here and there caught the eye in the still little known, but at that date almost entirely unexplored interior. Wherever a tree could obtain a foothold, there a tree[14] grew, until in places their roots were at times laved by the spray. Beneath this thick clothing of heavy timber flourished an almost equally dense undergrowth of shrubs, which until then were only known to us from the specimens introduced from North-West America into the European gardens. Gay were the thickets of thimbleberry[1] and salmonberry[2] wherever the soil was rich, and for miles the ground was carpeted with the salal,[3] while the huckleberry,[4] the crab-apple,[5] and the flowering currant[6] varied the monotony of the gloomy woods. In places the ginseng, or, as the woodmen call it, the "devil's walking-stick,"[7] with its long prickly stem and palm-like head of great leaves, imparted an almost tropical aspect to scenery which, seen from the deck of our little craft, looked so like that of Southern Norway, that I have never seen the latter without recalling the outer limits of British Columbia. On the few flat spits where the sun reached, the gigantic cedars[8] and broad-leaved maples[9] lighted up the scene, while the dogwood,[10] with its large white flowers reflected in the water of some river which, after a turbulent course, had reached the sea through a placid mouth, or a Menzies arbutus,[11] whose glossy leaves and brown bark presented a more southern facies to the sombre jungles, afforded here and there a relief to the never-ending fir and pine and spruce.

A more solitary shore, so far as white men are concerned, it would be hard to imagine. From the day we left until the day we returned, we sighted only one sail; and from Port San Juan, where an Indian trader lived a lonely life in an often-beleaguered blockhouse, to Koskeemo Sound, where another of these voluntary exiles passed his years among the savages, there was not a christened man, with the exception of the little settlement of lumbermen at the head of the Alberni Canal. For months at a time no keel ever ploughed this sea, and then too frequently it was a warship sent from Victoria to chastise the tribesmen for some outrage committed on wayfaring men such as we. The floating fur-trader with whom we exchanged the courtesies of the wilderness had indeed been despitefully used. For had he not taken to himself some savage woman, who had levanted to her tribe with those miscellaneous effects which he termed "iktas"? And the Klayoquahts had stolen his boat, and the Kaoquahts his beans and his vermilion and his rice, and threatened to scuttle his schooner and stick his head on its masthead. And, moreover, to complete this tale of public pillage and private wrong, a certain chief, to whom he applied many ornate epithets, had declared that he cared not a salal-berry for all of "King George's warships." So that the conclusion of this merchant of the wilds was that, until "half the Indians were hanged, and the other half badly licked, there would be no peace on the coast for honest men such as he." Then, under a cloud of playful blasphemy, our friend sailed away.

For if civilisation was scarce in the Western Vancouver[17] of '63, savagedom was all-abounding. Not many hours passed without our having dealings with the lords of the soil. It was indeed our business—or, at least, the business of the two men and the Indian "boy"—to meet with and make profit out of the barbarous folk. Hence it was seldom that we went to sleep without the din of a board village in our ears, or woke without the ancient and most fish-like smell of one being the first odour which greeted our nostrils. In almost every cove, creek, or inlet there was one of these camps, and every few miles we entered the territory of a new tribe, ruled by a rival chief, rarely on terms with his neighbour, and as often as not at war with him. More than once we had occasion to witness the gruesome evidence of this state of matters. A war party returning from a raid on a distant hamlet would be met with, all painted in hideous colours, and with the bleeding heads of their decapitated enemies fastened to the bows of their cedar canoes, and the cowering captives, doomed to slavery, bound among the fighting men. Or, casting anchor in front of a village, we would be shown with pride a row of festering skulls stuck on poles, as proof of the military prowess of our shifty hosts.

These were, however, unusually unpleasant incidents. More frequently we saw little except the more lightsome traits of what was then a very primitive savage life, and the barbarous folk treated us kindly. A marriage feast might be in progress, or a great "potlatch," or merrymaking, at which the giving away of property was the principal feature (p. 82), might be in full blaze at the very moment we steered round the wooded point. Halibut[18] and dog-fish were being caught in vast quantities—the one for slicing and drying for winter use; the other for the sake of the oil extracted from the liver, then as now an important article of barter, being in ready demand by the Puget Sound saw-mills. Now and then a fur-seal or, better still, a sea-otter would be killed. But this is not the land of choice furs. Even the marten and the mink were indifferent. Beaver—which in those days, after having been almost hunted to death, were again getting numerous, owing to the low prices which the pelts brought having slackened the trappers' zeal—would often be brought on board, and a few hides of the wapiti, the "elk" of the Western hunter, and the black-tailed deer which swarm in the Vancouver woods, generally appeared at every village. The natives are, however, essentially fish-eaters, and though in every tribe there is generally a hunter or two, the majority of them seldom wander far afield, the interior being in their mythology a land of evil things, of which wise men would do well to keep clear. Even the black bear, which in autumn was often a common feature of the country, where it ranged the crab-apple thickets, was not at this season an object of the chase. Like the deer and the wolves, it was shunning the heat and the flies by summering near the snow which we could notice still capping some of the inland hills, rising to heights of from five thousand to seven thousand feet, and feasting on the countless salmon which were descending every stream, until, with the receding waters, they were left stranded in the upland pools. So cheap were salmon, that at times they could be bought for a cent's worth of "trade goods," and deer in winter for a few[19] charges of powder and shot. A whale-hunt, in which the behemoth was attacked by harpoons with attached inflated sealskins, after a fashion with which I had become familiar when a resident among the Eskimo of Baffin Bay, was a more curious sight. Yet dog-fish oil was the staple of the unpicturesque traffic in which my companions engaged; while I, a hunter after less considered trifles, landed to roam the woods and shores for days at a time, gathering the few flowers which bloomed under these umbrageous forests, though in number sufficient to tempt the red-beaked humming-bird[12] to migrate from Mexico to these northern regions, its tiny nest being frequently noticed on the tops of low bushes.

But, after all, the most interesting sight on the shore was the people who inhabited it. They were the "Indians," whom my friend Gilbert Sproat afterwards described as the "Ahts,"[13] for this syllable terminates the name of each of the many little tribes into which they are divided. Yet, with a disregard of the laws of nomenclature, the Ethnological Bureau at Washington has only recently announced its intention of knowing them officially by the meaningless title of "Wakashan." They are a people by themselves, speaking a language which was confined to Vancouver Island, with the exception of Cape Flattery, the western tip of Washington, where the Makkahs speak it. In Vancouver Island, a region about the size of Ireland, three, if not four distinct aboriginal tongues are in use, in addition to Chinook Jargon, a sort of lingua franca employed by the Indians in their intercourse with the whites or with tribes whose speech they do not understand. The Kawitshen (Cowitchan) with its various dialects, the chief of which is the Tsongersth (Songer) of the people near Victoria, prevails from Sooke in the Strait of Juan de Fuca, northwards to Comox. From that point to the northern end of the island various dialects of the Kwakiool (Cogwohl of the traders) are the medium in which the tribesmen do not conceal their thoughts. The people of Quatseno and Koskeemo Sounds, owing to their frequent intercourse with Fort Rupert on the other side of the island, which at this point is at its narrowest, understand and frequently speak the Kwakiool. But after passing several days entirely alone among these people, I can vouch for the fact that this dialect is so peculiar that it almost amounts to a separate language. However, from this part, or properly, from Woody Point southwards to Port San Juan, the Aht language is entirely different.

The latter locality,[14] nearly opposite Cape Flattery, on the other side of Juan de Fuca Strait, the most southern part, and the only one on the mainland where it is spoken, is the special territory of the Pachenahts. When I knew them, they were, like all of their race, a dwindling people. A few years earlier, Grant had estimated them to number a hundred men. In 1863 there were not more than a fifth of that number fit to manage a canoe, and the total number of the tribe did not exceed sixty. War with the Sclallans and Makkahs on the opposite shore, and smallpox, which is more powerful than gunpowder, had so decimated them that, no longer able to hold their own, they had leagued with the Nettinahts, old allies of theirs, for mutual defence. Quixto, the chief, I find described in my notes as a stout fellow, terrible at a bargain, very well disposed towards the whites, as are all his tribe, the husband of four wives, an extraordinary number for the Indians of the coast, and reputed to be rich in blankets and the other gear which constitutes wealth among the aborigines of this part of the British Empire. In their palmy days they had made way as far north as Clayoquat Sound and the Ky-yoh-quaht-cutz in one direction, and with the Tsongersth to the eastward, though that now pusillanimous tribe had generally the best of them. Their eastern border is, however, the Jordan River, but they have a fishing station at the Sombria (Cockles), and several miles up both the Pandora and Jordan Rivers flowing into their bay. Karleit is their western limit.

The Nettinahts[15] are a more powerful tribe; indeed, at the period when the writer of this book was a prisoner in Nootka Sound, they were among the strongest of all the Aht people. Even then, they had four hundred[16] fighting men, and were a people with whom it did not do to be off your guard. They have—or had—many villages, from Pachena Bay[17] to the west and Karleit to the east, besides three villages in Nettinaht Inlet,[18] eleven fishing stations on the Nettinaht River, three stations on the Cowitchan Lake, and one at Sguitz on the Cowitchan River itself, while they sometimes descend as far as Tsanena to plant potatoes. They have thus the widest borders of any Indian tribe in Vancouver Island, and have a high reputation as hunters, whale-fishers, and warriors. Moqulla was then the head chief, but every winter a sub-tribe hunted and fished on the Cowitchan Lake, a sheet of water which I was among the first to visit, and the very first to "lay down" with approximate accuracy. Though nowadays—Eheu fugaces, Postume, Postume, labuntur anni!—there is a waggon road to the lake, and, I am told, "a sort of hotel" on the spot where eight-and-twenty years ago we encamped on extremely short rations, though with the soothing knowledge that if only the Fates were kindly and the wind favourable, there were plenty of trout in the water, and a dinner at large in the woods around. In those days most of the Nettinaht villages were fortified with wooden pickets to prevent any night attack, and from its situation, Whyack, the principal one (built on a cliff, stockaded on the seaward side, and reached only by a narrow entrance where the surf breaks continuously), is impregnable to hostile canoemen. This people accordingly carried themselves with a high hand, and bore a name correspondingly bad.

Barclay—or Berkeley Sound—is the home of various petty tribes—Ohyahts, Howchuklisahts, Yu-clul-ahts, Toquahts, Seshahts, and Opechesahts. The two with whom I was best acquainted were the last named. The Seshahts lived at the top of the Alberni—a Canal[23] long narrow fjord or cleft in the island—and on the Seshaht Islands in the Sound. During the summer months they came for salmon-fishing to Sa ha, or the first rapids on the Kleekort or Saman River,[19] their chief being Ia-pou-noul, who had just succeeded to this office owing to the abdication of his father, though the entire fighting force of the tribe did not number over fifty men. As late as 1859 the Seshahts seized an American ship, the Swiss Boy. The Opechesahts, of whom I have very kindly memories, as I encamped with their chief for many days, and explored Sproat Lake in his company, were an offshoot of the Seshahts, and had their home on the Kleekort River, but, owing to a massacre by the now extinct Quallehum (Qualicom) Indians from the opposite coast, who caught them on an island in Sproat Lake, they were reduced to seventeen men, most of them, however, tall, handsome fellows, and good hunters. Chieftainship in that part of the world goes by inheritance. Hence there may be many of these hereditary aristocrats in a very small tribe. Accordingly, few though the Opechesaht warriors were, three men, Quatgenam, Kalooish or Kanash, and Quassoon, a shaggy, thick-set, and tremendously strong individual who crossed the island with me in 1865, were entitled to that rank; and it may be added that the women of this, the most freshwater of all the Vancouver tribes, were noted for a more than usual share of good looks.

The Howchuklisahts, whose chief was Maz-o-wennis, numbered forty-five people, including twenty-eight men. They lived in Ouchucklesit[20] Harbour, off the Alberni Canal; they had also a fishing camp on Henderson Lake, and two or three lodges on the rapid or stream flowing out of that sheet of water, which was discovered and named by me. But they were "bad to deal with."

The You-clul-ahts of Ucluelt Inlet, ruled by Ia-pou-noul, a wealthy man in blankets and other Indian wealth, numbered about one hundred. The chief of the Toquahts in Pipestem Inlet was Sow-wa-wenes, a middle-aged man, who had an easy task, as his lieges numbered only eleven, so that they were thirty years ago on the eve of extinction. The Ohyahts of Grappler Creek were estimated in 1863 to be about one hundred and seventy-five in fighting strength—which, multiplied by four for women and children, would make them, for that region, an unusually strong community. These figures are probably [25] correct, since the man who made the statement was, after living for years amongst them, eventually murdered by the savages,[21] whom he had trusted too implicitly. Kleesheens, a notorious scoundrel, was their chief. In Clayoquat Sound were the Klahoquahts, Kellsmahts, Ahousahts, Heshquahts, and Mamosahts—the last a little tribe numbering only five men. Indeed, with the exception of the Klahoquahts (who numbered one hundred and sixty men) and the Ahousahts (who claimed two hundred and fifty), these little septs, all devoured by mutual hatred, and frequently at war with each other, were even then dwindling to nothingness. But the Opetsahts, though marked on the Admiralty Chart[22] as a separate tribe, are—or were—only a village of the Ahousahts.

In Nootka Sound, the Muchlahts and Mooachahts lived. In Esperanza Inlet were the villages of two tribes—the Noochahlahts and Ayattisahts, numbering forty and twenty-two men respectively, and chiefed at that time[26] by two worthies of the names of Mala-koi-Kennis, and Quak-ate-Komisa, whom we left in the delectable condition of each expecting the other round to cut his and his tribesmen's throats.

North of this inlet were Ky-yoh-quahts, of the Sound of that name (Kaioquat), numbering two hundred and fifty men. To us they were exceedingly friendly, though a trader whom we met had a different tale to tell of their treatment of him. Kanemat, a young man of about twenty-two, was their chief, though the tribe was virtually governed by his mother, a notable lady named Shipally, and at times by his pretty squaw, Wick-anes, and his lively son and heir, Klahe-ek-enes. The Chaykisahts, the Klahosahts, and the Neshahts of Woody Point are the other Aht tribes, though the latter is not included among them by Mr. Sproat. But they speak their language, of which their chief village is its most northern limit.

Everywhere their tribes showed such evident signs of decadence that by this time some of them must be all but extinct. Still, as the whites had not come much in contact with them—though all of them asked us for "lum" (rum), but did not get it, it is clear enough what had been the traders' staple—the "diseases of civilisation" could not be blamed for their decay. Even then the practical extermination of two tribes was so recent that the facts were still fresh in their neighbours' memory. These were the Ekkalahts, who lived at the top of the Alberni Canal, but were all but killed off in the same massacre by which the Opechesahts were decimated. The only survivor was a man named Keekeon, who lived with the Seshahts, most of whom had forgotten[27] even the name of this vanquished little nationality. The other tribe was the Koapinahts (or Koapin-ah), who at that time numbered sixty or seventy people, but at the period to which I refer they were reduced to two adults—a man and a woman—all the rest having been slaughtered a few years earlier by the Kwakiools from the other side of the island, in conjunction with the Neshahts of Woody Point. In after days I learned to know these tribes very familiarly, crossing and recrossing the island with or to them, hunting and canoeing with them, in the woods, up the rivers, or on the lakes, and gathering from their lips

At first sight these "tinkler loons and siclike companie" were by no means attractive. They were frowsy, and, undeniably, they were not clean. But it was only after penetrating their inner ways, after learning the wealth of custom and folk-lore of which they, all unconscious of their riches, were the jealous custodians, that one began to appreciate these primitive folk from a scientific point of view. Even yet, as the writer recalls the days when he was prone to find men more romantic than is possible in "middle life forlorn," it is difficult not to associate the most prosaic of savages with something of the picturesqueness which, in novels at least, used to cling to all their race. For, as the charm of such existence as theirs unfolded itself to the lover of woods and prairies, and lakes and virgin streams, the neglect of soap and of sanitation was forgotten. As Mr. Leland has remarked about the[28] gipsies: "When their lives and legends are known, the ethnologist is apt to think of Tieck's elves, and of the Shang Valley, which was so grim and repulsive from without, but which, once entered, was the gay forecourt of Goblin-land."

In those days little was known—and little cared—about any of the Western tribes, except by the "schooner-men," as the Indians called the roving traders. Their very names were strange to the majority of the Victoria people, and I am told that very few of the colonists of to-day are any better informed. It has therefore been thought fitting that I should go somewhat minutely into the condition of the Indians, at a period when they were more primitive than now, as a slight contribution to the meagre chronicles of a dying race. For if not preserved here, it is likely to perish with almost the last survivor of a little band with whom, during the last two decades, death has been busy.

Among the many inlets which we entered on the cruise which has enabled me to edit this narrative of a less fortunate predecessor, was Nootka Sound. No portion of North-West America was more famous than this spot, for once upon a time it was the former centre of the fur trade, and a locality which more than once figured prominently in diplomatic correspondence. Indeed, so associated was it as the type of this part of the western continent, that in many works the heterogeneous group of savages who inhabit the entire coast between the Columbia River and the end of Vancouver Island was described as the "Nootka-Columbians." More than one species of plant and animal attest the fact of this Sound having been the locality at which the naturalist first broke ground in North-West [29] America. There are, for instance, a Haliotis Nutkaensis (an ear shell), a Rubus Nutkanus (a raspberry); and a yellow cypress, which, however, attained its chief development on the mainland much farther north, bears among its synonyms that of Chamcæcyparis Nutkaensis. For though it is undeniable that Ensign Juan Perez discovered it as early as 1779, and named it Port San Lorenzo, after the saint on whose day it was first seen, this fact was unknown or forgotten, when, four years later, Cook entered, and called it King George Sound, though he tells us it was afterwards found that it was called Nootka by the natives. Hence arose the title it has ever since borne, though this was an entire mistake on the great navigator's part, since there is no word in the Aht language at all corresponding to Nootka, unless indeed it is "Nootche," a mountain, which not unlikely Cook mistook for that of the inlet generally. The proofs of the presence of earlier visitors were iron and other tools, familiarity with ships, and two silver spoons of Spanish manufacture, which, we may take it, had been stolen from Perez's ship. The next vessel to enter the Sound was the Sea Otter, under the command of Captain James Hanna, who made such a haul in the shape of sea-otter skins that for many years Nootka was the great rendezvous of the fur-traders who cruised as far north as Russian America—now Alaska—and, like Portlock, Dixon, and Meares, charted and named many of the most familiar parts of the British Columbian coast. Meares built the North-West America by the aid of Chinese carpenters in Nootka Sound in the winter of 1788-89, this little sloop being the first vessel, except[30] a canoe, ever constructed in the country north of California.

The lucrative trade done by the English and American traders, some of whom, disposing of their furs in China, sailed under the Portuguese flag and fitted out at Macao as the port most readily open to them, determined the Spaniards to assert their rights to the original discovery. This was done by Don Estevan Martinez "taking possession" of the Sound, seizing the vessels there, and erecting a fort to maintain the territory against all comers. A hot diplomatic warfare ensued, the result of which was the Convention of Nootka, by which the Sound was made over to Great Britain; and it was while engaged on this mission of receiving the Sound that Vancouver, conjointly with Quadra, the Spanish commander, discovered that the region it intersects is an island, which for a time bore their joint names, but by general consent has that of Vancouver only attached to it nowadays.

This was in the year 1795. Being now indisputably British territory, Nootka and the coasts north and south of it became more and more frequented by fur-traders, who found, in spite of the increasing scarcity of pelts, and the higher prices which keener competition brought about, an ample profit in buying tolerably cheap on the American coast and selling very dear to the Chinese, whose love for the sea-otter continues unabated. Many of these adventurers were Americans—hailing, for the most part, from Boston. Hence to this day an American is universally known among the North-Western Indians as a "Boston-man," while an Englishman[31] is quite as generally termed a "Kintshautsh man" (King George man), it being during the long reign of George III. that they first became acquainted with our countrymen. Their barter was carried on in knives, copper plates, copper kettles, muskets, brass-hilted swords, soldiers' coats and buttons, pistols, tomahawks, and blankets, which soon superseded the more costly "Kotsaks" of sea-otter until then the principal garment, though the women wore, as they do still at times (or did when I knew the shore), blankets woven out of pine-tree bark. Rum also seemed to have been freely disposed of, and no doubt many of the outrages which early began to mark the intercourse of the brown men and their white visitors were not a little due to this, and to the customs, ever more free than welcome, in which it is the habit of the mariner to indulge when he and the savage forgather. At all events, the natives and their foreign visitors seem to have come very soon into collision. Indeed, it was seldom that a voyage was completed without some outrage on one or both sides, followed by reprisals from the party supposed to have been wronged. Thus part of the crew of the Imperial Eagle, under the command of Captain Barclay,[23] who discovered and named in his own honour the Sound so called, were murdered at "Queenhythe,"[24] south of Juan de Fuca Strait, which Barclay was amongst the first to explore, or rather to rediscover. At a later date, namely, in 1805, the Atahualpa of Rhode Island was attacked in Millbank Sound, and her captain, mate, and six seamen were killed. In 1811 the Tonquin, belonging to John Jacob Astor's romantic fur-trading adventure, which is so well known from Washington Irving's Astoria, was seized by the savages on this coast, and then blown up by M'Kay, the chief trader, with the entire crew and their assailants. The scene of the catastrophe has been stated to be Nootka, but other commentators have fixed upon Barclay Sound, and as late as 1863 an intelligent trader informed me that some ship's timbers, half buried in the sand there, were attributed by the Indians to some disastrous event, which he believed to have been the one in question.[25] I am, however, now inclined to think that in crediting Nahwitti, at the northern end of Vancouver Island, with this notable event in the early history of North-West America,[26] Dr. George Dawson has arrived at the truth.

[32] To this day—or until very recently—the Indians of the North-West coast are not accounted very trustworthy, and at the period when I knew them they were suspected of killing several traders and of looting more than one small vessel, acts which earned for them frequent visits from the gunboats at Esquimault, and in several instances the undesirable distinction of having their villages shelled when they refused to give up the offenders—generally a difficult operation, since it meant pretty well the entire village.

[35]But the most famous of all the piracies of the Western Indians is that of which an account is contained in John Jewitt's Narrative. The ostensible author of this work was a Hull blacksmith, the armourer of the Boston, an American ship which was seized while lying in Nootka Sound, and the entire crew massacred, with the exception of Jewitt, who was spared owing to his skill as a mechanic being valuable to the Indians, and John Thompson, the sail-maker, who, though left for dead, recovered, and was saved by the tact of Jewitt in representing him to be his father. This happened in March 1803, and from that date until the 20th of July 1805, these two men were kept in slavery to the chief Maquenna or Moqulla, when they were freed by the arrival of the brig Lydia of Boston, Samuel Hill master. During this servitude, Jewitt, who seems to have been a man of some education, kept a journal and acquired the Aht language, though the style in which his book is written shows that in preparing it for the press he had obtained the assistance of a more practised writer than himself. Still, his work is a valuable contribution to ethnology. For, omitting the brief but excellent accounts by Cook and Meares, it is the earliest, and, with the exception of Mr. Sproat's lecture, the fullest description of these Indians. It is indeed the only one treating specially on the Nootka people, with whom alone he had any minute acquaintance. Some of the habits he pictures are now obsolete, or greatly modified, but[36] others—it may be said the greater number—are exactly as he notes them to have been eighty-six years ago. Besides the internal evidences of its authenticity, the truth of the adventures described was vouched for at the time by Jewitt's companion in slavery; and though there is no absolute proof of its credibility, it may not be uninteresting to state that, thirty years ago, I conversed with an American sea captain, who, as a boy, distinctly remembered Jewitt working as a blacksmith in the town of Middleton in Connecticut. When the book was first published, in the year 1815, several editions appeared in America, and at least two reprints were called for in England, so that the Narrative enjoyed considerable popularity in the first two decades of the century. Writing in 1840, Robert Green Low, Librarian to the Department of State at Washington, characterises it as "a simple and unpretending narrative, which will, no doubt, in after centuries, be read with interest by the enlightened people of North-West America." Again, in 1845, the same industrious, though not always impartial, historian remarks that "this little book has been frequently reprinted, and, though seldom found in libraries, is much read by boys and seamen in the United States." As copies are now seldom met with, this is no longer the case, though on our cruise in 1863 it was one of the well-thumbed little library of the traders, one of whom had inherited it from William Edy Banfield, whose name has already been mentioned (p. 25). This trader, for many years a well-known man on the out-of-the-way parts of the coast, furnished a curious link between Jewitt's time and our own. For an old Indian told him that he had, as a boy, served in[37] the family of a chief of Nootka, called Klan-nin-itth, at the time when Jewitt and Thompson were in slavery; and that he often assisted Jewitt in making spears, arrows, and other weapons required for hostile expeditions. He said, further, that the white slave generally accompanied his owner on visits which he paid to the Ayhuttisaht, Ahousaht, and Klahoquaht chiefs. This old man especially remembered Jewitt, who was a good-humoured fellow, often reciting and singing in his own language for the amusement of the tribesmen. He was described as a tall, well-made youth, with a mirthful countenance, whose dress latterly consisted of nothing but a mantle of cedar bark. Mr. Sproat, who obtained his information from the same quarter that I did, adds that there was a long story of Jewitt's courting, and finally abducting, the daughter of Waughclagh, the Ahousaht chief. This incident in his career is not recorded by our author, who, however, was married to a daughter of Upquesta, an Ayhuttisaht Indian.

Apart, however, from Jewitt not caring to enlighten the decent-living puritans of Connecticut too minutely regarding his youthful escapades, it is not unlikely that Mr. Banfield's informant mixed up some half-forgotten legends regarding another white man, who, seventeen years before Jewitt's captivity, had voluntarily remained among these Nootka Indians. This was a scapegrace named John M'Kay,[27] an Irishman, who, after being in the East India Company's Service in some minor medical capacity, shipped in 1785 on board the Captain Cook as surgeon's mate, and was left behind in Nootka Sound, in the hope that he would so ingratiate himself with the natives, as to induce them to refuse furs to any other traders except those with whom he was connected. This man seems to have been an ignorant, untruthful braggart, who contradicted himself in many important particulars. But entire credence may be given to his statement that in a short time he sank into barbarism, becoming as filthy as the dirtiest of his savage companions. For when Captain Hanna saw him in August 1786, the natives had stripped him of his clothes, and obliged him to adopt their dress and habits. He even refused to leave, declaring that he had begun to relish dried fish and whale oil—though, owing to a famine in the Sound, he got little of either—and was well satisfied to stay for another year. After making various excursions in the country about Nootka Sound, during which he came to the conclusion that it was not a part of the American continent, but a chain of detached islands, he gladly deserted his Indian wife, and left with Captain Berkeley in 1787. To "preach, fight, and mend a musket" seems to have been too much for this medical pluralist. His further history I am unable to trace, though, for the sake of historical roundness, it would have been interesting to believe that he was the same M'Kay who twenty-four years later ended his career so terribly by blowing up the Tonquin, with whose son I was well acquainted.

In all of these transactions the head chief of Nootka, or at least of the Mooachahts, figures prominently. This was Maquenna or Moqulla (Jewitt's Maquina), who, with his relative Wikananish, ruled over most of the tribes from here to Nettinaht Inlet. He was a shifty savage,[39] endowed with no small mental ability, and, though at times capable of acts which were almost generous, untrustworthy like most of his race, and when offended ready for any act of vindictiveness. Wikananish was on a visit to Maquenna when the Discovery and Resolution entered the Sound, and among the relics which Maquenna kept for many years were a brass mortar left by Cook, which in Meares's day was borne before the chief as a portion of his regalia, and three "pieces of a brassy metal formed like cricket bats," on which were the remains of the name and arms of Sir Joseph Banks, and the date 1775—Banks, it may be remembered, being the scientific companion of Cook. In every subsequent voyage Maquenna figures, and not a few of the outrages committed on that coast were due either to him or to his instigation. Some, like his attempt to seize Hanna's vessel in 1785, are known from extraneous sources, and others were boasted of by him to Jewitt. The last of his proceedings of which history has left any record, is the murder of the crew of the Boston and the enslavement of Thompson and Jewitt, and in the narrative of the latter we are afforded a final glimpse of this notorious "King."[28]

When I visited Nootka Sound in 1863, fifty-eight years had passed since the captivity of the author of this book. In the interval [40] many things had happened. But though the Indians had altered in some respects, they were perhaps less changed than almost any other savages in America since the whites came in contact with them. Eighty-five years had passed since Cook had careened his ships in Resolution Cove, and seventy since Vancouver entered the Sound on his almost more notable voyage. Yet the bricks from the blacksmith's forge, fresh and vitrified as if they had been in contact with the fire only yesterday, were at times dug up from among the rank herbage. The village in Friendly Cove—a spot which not a few mariners found to be very unfriendly—differed in no way from the picture in Cook's Voyage; and though some curio-hunting captain had no doubt long ago carried off the mortar and emblazoned brasses, the natives still spoke traditionally of Cook and Vancouver, and were ready to point out the spots where in 1788 Meares built the North-West America and the white men had cultivated. Memories of Martinez and Quadra existed in the shape of many legends, of Indians with Iberian features, and of several old people who by tradition (though some of them were old enough to have remembered these navigators), could still repeat the Spanish numerals. And the head chief of the Mooachahts in Friendly Cove—vastly smaller though his tribe was, and much abridged his power—was a grandson of Maquenna, called by the same name, and had many of his worst characteristics. This fact I am likely to remember. For he had been accused of having murdered, in the previous January, Captain Stev of the Trader, and since that time no whites had ventured near him. He, however, assured us that the report was simply a scandal raised by the [41] neighbouring tribes, who had long hated him and his people, and would like to see them punished by the arrival of a gunboat, and that in reality the vessel was wrecked, and the white men were drowned. At the same time, among the voices heard that night at the council held in Maquenna's great lodge, supported by the huge beams described by Jewitt, were some in favour of killing his latest visitors, on the principle that dead men tell no tales. But that the Noes had it, the present narrative is the best proof.

So far as their habits were concerned, they were in a condition as primitive as at almost any period since the whites had visited them. Many of the old people were covered only with a mantle of woven pine bark, and beyond a shirt, in most cases made out of a flour sack, a blanket was the sole garment of the majority of the tribesmen. At times when they wanted to receive any goods, they simply pulled off the blanket, wrapped up the articles in it, and went ashore stark naked, with the exception of a piece of skin round the loins. The women wore for the most part no other dress except the blanket and a curious apron made of a fringe of bark strings. All of them painted hideously, the women adding a streak of vermilion down the middle division of the hair, and on high occasions the glittering mica sand, spoken of by Jewitt, was called into requisition. Their customs—and I had plenty of opportunities to study them in the course of the years which followed—were in no way different from what they were in Cook's time. No missionary seemed ever to have visited them, and their religious observances were accordingly[42] still the most unadulterated of paganism. Jewitt's narrative is, however, as might have been expected, very vague on such matters; and, curiously enough, he makes no mention of their characteristic trait of compressing the foreheads of the children, the tribes in Koskeemo Sound squeezing it, while the bones are still cartilaginous, in a conical shape—though the brain is not thereby permanently injured: it is simply displaced.

Since that day, the tribesmen of the west coast of Vancouver Island have grown fewer and fewer. Some of the smaller septs have indeed become extinct, and others must be fast on the wane. They have, however, eaten of the tree of knowledge, and the gunboats have now little occasion to visit them for punitive purposes. Missionaries have even attempted to teach them better manners. The Alberni saw-mills have long been deserted, though other settlers have taken possession of the ground, and several have squatted in Koskeemo Sound, in the hope that the coal-seams there might induce the Pacific steamers to make that remote region their headquarters. Finally, an effort is being made to induce fishermen from the West of Scotland to settle on that coast. There is plenty of work for them, and the Indians nowadays are very little to be feared. Indeed, so far from the successors of Moqulla and Wikananish menacing Donald and Sandy, they will be ready to help them for a consideration; though a great deal of tact and forbearance will be necessary before people so conservative as the hot-tempered Celts work smoothly with a race quite as fiery and quite as wedded to old ways, as the Ahts among whom John Jewitt passed the early years of this century.

R. B.

[1] Rubus Nutkanus.

[2] Rubus spectabilis.

[3] Gaultheria Shallon.

[4] Vaccinium ovatum.

[5] Pyrus rivularis.

[6] Ribes sanguineum, now a common shrub in our ornamental grounds.

[7] Echinopanax horridum.

[8] Thuja gigantea, a tree which to the Indian is what the bamboo is to the Chinese.

[9] Acer macrophyllum.

[10] Cornus Nuttallii.

[11] Arbutus Menziesii.

[12] Selasphorus rufus. It is one of one hundred and fifty-three birds which I catalogued from Vancouver Island (Ibis, Nov. 1868).

[13] Scenes and Studies of Savage Life (1868), by the Hon. G. M. Sproat, late Commissioner of Indian Affairs for British Columbia.

[14] "Pachena" of the Indians.

[15] Or, as they call themselves in their dialect of the Aht, "Dittinahts." Nettinaht is a white man's corruption.

[16] A few years earlier they were estimated at a thousand.

[17] "Klootis" of the Indians.

[18] Known to them as "Etlo."

[19] They were not permitted this privilege until the whites came to Alberni in August 1860.

[20] Though the orthography of these names is often incorrect, and not even phonetically accurate, I have, in order to avoid the mischief of a confusion of nomenclature, kept to that of the Admiralty Chart.

[21] This was the Banfield who acted as Indian agent in Barclay Sound. He was drowned by Kleetsak, a slave of Kleesheens, capsizing the canoe in which he was sailing, in revenge for a slight passed upon the chief. I went ashore at the Ohyaht village in the same canoe, and was asked whether I was not afraid, "for Banipe was killed in it." There was also a story that the capsize was an accident.

[22] It may be proper to state in this place that the interior details of that chart are, with very few exceptions, from my explorations. But the map on which they were laid down by me has been so often copied by societies, governments, and private individuals without permission (and without acknowledgment), that the author of it has long ceased to claim a property so generally pillaged. The original, however, appeared, with a memoir on the interior—"Das Innere der Vancouver Insel"—which has not yet been translated, in Petermann's Geographische Mittheilungen, 1869.

[23] Or Berkeley—for the name is spelt both ways.

[24] Destruction Island, in lat. 47° 35'. This was almost the same spot as that in which the Spaniards of Bodega's crew were massacred in 1775, and for this reason they named it Isla de Dolores—the "Island of Sorrows." It is in what is now the State of Washington, U.S.A.

[25] Green Low will even blame Wikananish, who figures in Jewitt's narrative, as the instigator of the outrage.

[26] The Nahwitti Indians. Compare the Tlā-tlī-sī—Kwela and Nekum-ke-līsla septs of the Kwakiool people. They now inhabit a village named Meloopa, on the south-east side of Hope Island. But their original hamlet was situated on a small rocky peninsula on the east side of Cape Commerell, which forms the north point of Vancouver Island. Here remains of old houses are still to be seen, at a place known to the Indians as Nahwitti. It was close to this place that the Tonquin was blown up.—Science, vol. ix. p. 341.

[27] "Maccay" (Meares); "M'Key" (Dixon).

[28] There is a portrait of him, apparently authentic, in Meares's Voyages, vol. ii. (1791). That in the original edition of Jewitt's Narrative, like the plate of the capture of the Boston, appears to have been drawn from description, though there is a certain resemblance in it to Meares's sketch made fourteen or fifteen years earlier. But the scenery, the canoes, the people, and, above all, the palm trees in Nootka Sound, are purely imaginary.

BIRTH, PARENTAGE AND EARLY LIFE OF THE AUTHOR

I was born in Boston, a considerable borough town in Lincolnshire, in Great Britain, on the 21st of May, 1783. My father, Edward Jewitt, was by trade a blacksmith, and esteemed among the first in his line of business in that place. At the age of three years I had the misfortune to lose my mother, a most excellent woman, who died in childbed, leaving an infant daughter, who, with myself, and an elder brother by a former marriage of my father, constituted the whole of our family. My father, who considered a good education as the greatest blessing he could bestow on his children, was very particular in paying every attention to us in that respect, always exhorting us to behave well, and endeavouring to impress on our minds the principles of virtue and morality, and no expense in his power was spared to have us instructed in whatever might render us useful and respectable in society. My brother, who was four years older than myself and of a more hardy constitution, he destined for his own trade, but to me he had[44] resolved to give an education superior to that which is to be obtained in a common school, it being his intention that I should adopt one of the learned professions. Accordingly, at the age of twelve he took me from the school in which I had been taught the first rudiments of learning, and placed me under the care of Mr. Moses, a celebrated teacher of an academy at Donnington, about eleven miles from Boston, in order to be instructed in the Latin language, and in some of the higher branches of the mathematics. I there made considerable proficiency in writing, reading, and arithmetic, and obtained a pretty good knowledge of navigation and of surveying; but my progress in Latin was slow, not only owing to the little inclination I felt for learning that language, but to a natural impediment in my speech, which rendered it extremely difficult for me to pronounce it, so that in a short time, with my father's consent, I wholly relinquished the study.

The period of my stay at this place was the most happy of my life. My preceptor, Mr. Moses, was not only a learned, but a virtuous, benevolent, and amiable man, universally beloved by his pupils, who took delight in his instruction, and to whom he allowed every proper amusement that consisted with attention to their studies.

One of the principal pleasures I enjoyed was in attending the fair, which is regularly held twice a year at Donnington, in the spring and in the fall,[29] the second day being wholly devoted to selling horses, a prodigious number of which are brought thither for that purpose. As the scholars on these occasions were always indulged with a holiday, I cannot express with what eagerness of youthful expectation I used to anticipate these fairs, nor what delight I felt at the various shows, exhibitions of wild beasts, and other entertainments that they presented; I was frequently visited by my father, who always discovered much joy on seeing me, praised me for my acquirements, and usually left me a small sum for my pocket expenses.

Among the scholars at this academy, there was one named Charles Rice, with whom I formed a particular intimacy, which continued during the whole of my stay. He was my class and room mate, and as the town he came from, Ashby, was more than sixty miles off, instead of returning home, he used frequently during the vacation to go with me to Boston, where he always met with a cordial welcome from my father, who received me on these occasions with the greatest affection, apparently taking much pride in me. My friend in return used to take me with him to an uncle of his in Donnington, a very wealthy man, who, having no children of his own, was very fond of his nephew, and on his account I was always a welcome visitor at the house. I had a good voice, and an ear for music, to which I was always passionately attached, though my father endeavoured to discourage this propensity, considering it (as is too frequently the case) but an introduction to a life of idleness and dissipation; and, having been remarked for my singing at church, which was regularly attended on Sundays and festival days by the scholars, Mr. Morthrop, my friend Rice's uncle, used frequently to request me to sing; he was always pleased[46] with my exhibitions of this kind, and it was no doubt one of the means that secured me so gracious a reception at his house. A number of other gentlemen in the place would sometimes send for me to sing at their houses, and as I was not a little vain of my vocal powers, I was much gratified on receiving these invitations, and accepted them with the greatest pleasure.

Thus passed away the two happiest years of my life, when my father, thinking that I had received a sufficient education for the profession he intended me for, took me from school at Donnington in order to apprentice me to Doctor Mason, a surgeon of eminence at Reasby, in the neighbourhood of the celebrated Sir Joseph Banks.[30] With regret did I part from my school acquaintance, particularly my friend Rice, and returned home with my father, on a short visit to my family, preparatory to my intended apprenticeship. The disinclination I ever had felt for the profession my father wished me to pursue, was still further increased on my return. When a child I was always fond of being in the shop, among the workmen, endeavouring to imitate what I saw them do; this disposition so far increased after my leaving the academy, that I could not bear to hear the least mention made of my being apprenticed to a surgeon, and I used so many entreaties with my father to persuade him to give up this plan and learn me his own trade, that he at last consented.

More fortunate would it probably have been for me, had I gratified the wishes of this affectionate parent, in adopting the profession he had chosen for me, than thus to have induced him to sacrifice them to mine. However it might have been, I was at length introduced into the shop, and my natural turn of mind corresponding with the employment, I became in a short time uncommonly expert at the work to which I was set. I now felt myself well contented, pleased with my occupation, and treated with much affection by my father, and kindness by my step-mother, my father having once more entered the state of matrimony, with a widow much younger than himself, who had been brought up in a superior manner, and was an amiable and sensible woman.

About a year after I had commenced this apprenticeship, my father, finding that he could carry on his business to more advantage in Hull, removed thither with his family. An event of no little importance to me, as it in a great measure influenced my future destiny. Hull being one of the best ports in England, and a place of great trade, my father had there full employment for his numerous workmen, particularly in vessel work. This naturally leading me to an acquaintance with the sailors on board some of the ships: the many remarkable stories they told me of their voyages and adventures, and of the manners and customs of the nations they had seen, excited a strong wish in me to visit foreign countries, which was increased by my reading the voyages of Captain Cook, and some other celebrated navigators.

Thus passed the four years that I lived at Hull, where my father was esteemed by all who knew him, as a worthy, industrious, and thriving man. At this period a circumstance occurred which afforded me the opportunity[48] I had for some time wished, of gratifying my inclination of going abroad.

Among our principal customers at Hull were the Americans who frequented that port, and from whose conversation my father as well as myself formed the most favourable opinion of that country, as affording an excellent field for the exertions of industry, and a flattering prospect for the establishment of a young man in life. In the summer of the year 1802, during the peace between England and France, the ship Boston, belonging to Boston, in Massachusetts, and commanded by Captain John Salter, arrived at Hull, whither she came to take on board a cargo of such goods as were wanted for the trade with the Indians, on the North-West coast of America, from whence, after having taken in a lading of furs and skins, she was to proceed to China, and from thence home to America. The ship having occasion for many repairs and alterations, necessary for so long a voyage, the captain applied to my father to do the smith's work, which was very considerable. That gentleman, who was of a social turn, used often to call at my father's house, where he passed many of his evenings, with his chief and second mates, Mr. B. Delouisa and Mr. William Ingraham,[31] the latter a fine young man of about twenty, of a most amiable temper, and of such affable manners, as gained him the love and attachment of the whole crew. These gentlemen used occasionally to take me with them to the theatre, an amusement which I was very fond of, and which my father rather encouraged than objected to, as he thought it a good means of preventing young men, who are naturally inclined to seek for something to amuse them, from frequenting taverns, ale-houses, and places of bad resort, equally destructive of the health and morals, while the stage frequently furnishes excellent lessons of morality and good conduct.

In the evenings that he passed at my father's, Captain Salter, who had for a great number of years been at sea, and seen almost all parts of the world, used sometimes to speak of his voyages, and, observing me listen with much attention to his relations, he one day, when I had brought him some work, said to me in rather a jocose manner, "John, how should you like to go with me?" I answered, that it would give me great pleasure, that I had for a long time wished to visit foreign countries, particularly America, which I had been told so many fine stories of, and that if my father would give his consent, and he was willing to take me with him, I would go.

"I shall be very glad to do it," said he, "if your father can be prevailed on to let you go; and as I want an expert smith for an armourer, the one I have shipped for that purpose not being sufficiently master of his trade, I have no doubt that you will answer my turn well, as I perceive you are both active and ingenious, and on my return to America I shall probably be able to do something much better for you in Boston. I will take the first opportunity of speaking to your father about it, and try to persuade him to consent." He[50] accordingly, the next evening that he called at our house, introduced the subject: my father at first would not listen to the proposal. That best of parents, though anxious for my advantageous establishment in life, could not bear to think of parting with me, but on Captain Salter's telling him of what benefit it would be to me to go the voyage with him, and that it was a pity to keep a promising and ingenious young fellow like myself confined to a small shop in England, when if I had tolerable success I might do so much better in America, where wages were much higher and living cheaper, he at length gave up his objections, and consented that I should ship on board the Boston as an armourer, at the rate of thirty dollars per month, with an agreement that the amount due to me, together with a certain sum of money, which my father gave Captain Salter for that purpose, should be laid out by him on the North-West coast in the purchase of furs for my account, to be disposed of in China for such goods as would yield a profit on the return of the ship; my father being solicitous to give me every advantage in his power of well establishing myself in my trade in Boston, or some other maritime town of America. Such were the flattering expectations which this good man indulged respecting me. Alas! the fatal disaster that befell us, not only blasted all these hopes, but involved me in extreme distress and wretchedness for a long period after.

The ship, having undergone a thorough repair and been well coppered, proceeded to take on board her cargo, which consisted of English cloths, Dutch blankets, looking-glasses, beads, knives, razors, etc., which were[51] received from Holland, some sugar and molasses, about twenty hogsheads of rum, including stores for the ship, a great quantity of ammunition, cutlasses, pistols, and three thousand muskets and fowling-pieces. The ship being loaded and ready for sea, as I was preparing for my departure, my father came to me, and, taking me aside, said to me with much emotion, "John, I am now going to part with you, and Heaven only knows if we shall ever again meet. But in whatever part of the world you are, always bear it in mind, that on your own conduct will depend your success in life. Be honest, industrious, frugal, and temperate, and you will not fail, in whatsoever country it may be your lot to be placed, to gain yourself friends. Let the Bible be your guide, and your reliance in any fortune that may befall you, that Almighty Being, who knows how to bring forth good from evil, and who never deserts those who put their trust in Him." He repeated his exhortations to me to lead an honest and Christian life, and to recollect that I had a father, a mother, a brother, and sister, who could not but feel a strong interest in my welfare, enjoining me to write him by the first opportunity that should offer to England, from whatever part of the world I might be in, more particularly on my arrival in Boston. This I promised to do, but long unhappily was it before I was able to fulfil this promise. I then took an affectionate leave of my worthy parent, whose feelings would hardly permit him to speak, and, bidding an affectionate farewell to my brother, sister, and step-mother, who expressed the greatest solicitude for my future fortune, went on board the ship, which proceeded to the Downs, to be ready for the first favourable[52] wind. I found myself well accommodated on board as regarded my work, an iron forge having been erected on deck; this my father had made for the ship on a new plan, for which he afterwards obtained a patent; while a corner of the steerage was appropriated to my vice-bench, so that in bad weather I could work below.

[29] These fairs are still held, though the dates are now May 26th, September 4th, and October 27th.

[30] The companion of Cook, and for many years President of the Royal Society.

[31] This William Ingraham must not be confounded with Joseph Ingraham, who also visited Nootka Sound, and played a considerable part in the exploration of the North-West American coast.

VOYAGE TO NOOTKA SOUND

On the third day of September, 1802, we sailed from the Downs with a fair wind, in company with twenty-four sail of American vessels, most of which were bound home.

I was sea-sick for a few of the first days, but it was of short continuance, and on my recovery I found myself in uncommonly fine health and spirits, and went to work with alacrity at my forge, in putting in order some of the muskets, and making daggers, knives, and small hatchets for the Indian trade, while in wet and stormy weather I was occupied below in filing and polishing them. This was my employment, having but little to do with sailing the vessel, though I used occasionally to lend a hand in assisting the seamen in taking in and making sail.

As I had never before been out of sight of land, I cannot describe my sensations, after I had recovered from the distressing effects of sea-sickness, on viewing the mighty ocean by which I was surrounded, bound only by the sky, while its waves, rising in mountains, seemed every moment to threaten our ruin. Manifest as is the hand of Providence in preserving its creatures from destruction, in no instance is it more so[54] than on the great deep; for whether we consider in its tumultuary motions the watery deluge that each moment menaces to overwhelm us, the immense violence of its shocks, the little that interposes between us and death, a single plank forming our only security, which, should it unfortunately be loosened, would plunge us at once into the abyss, our gratitude ought strongly to be excited towards that superintending Deity who in so wonderful a manner sustains our lives amid the waves.

We had a pleasant and favourable passage of twenty-nine days to the Island of St. Catherine,[32] on the coast of Brazils, where the captain had determined to stop for a few days to wood and water. This place belongs to the Portuguese. On entering the harbour, we were saluted by the fort, which we returned. The next day the governor of the island came on board of us with his suite; Captain Salter received him with much respect, and invited him to dine with him, which he accepted. The ship remained at St. Catherine's four days, during which time we were busily employed in taking in wood, water, and fresh provisions, Captain Salter thinking it best to furnish himself here with a full supply for his voyage to the North-West coast, so as not to be obliged to stop at the Sandwich Islands. St. Catherine's is a very commodious place for vessels to stop at that are bound round Cape Horn, as it abounds with springs of fine water, with excellent oranges, plantains, and bananas.

Having completed our stores, we put to sea, and on the twenty-fifth of December, at length passed Cape Horn, which we had made no less than thirty-six days before, but were repeatedly forced back by contrary winds, experiencing very rough and tempestuous weather in doubling it.

Immediately after passing Cape Horn, all our dangers and difficulties seemed to be at an end; the weather became fine, and so little labour was necessary on board the ship, that the men soon recovered from their fatigue and were in excellent spirits. A few days after we fell in with an English South Sea whaling ship homeward bound,[33] which was the only vessel we spoke with on our voyage. We now took the trade wind or monsoon, during which we enjoyed the finest weather possible, so that for the space of a fortnight we were not obliged to reeve a topsail or to make a tack, and so light was the duty and easy the life of the sailors during this time, that they appeared the happiest of any people in the world.

Captain Salter, who had been for many years in the East India trade, was a most excellent seaman, and preserved the strictest order and discipline on board his ship, though he was a man of mild temper and conciliating manners, and disposed to allow every indulgence to his men, not inconsistent with their duty. We had on board a fine band of music, with which on Saturday nights, when the weather was pleasant, we were accustomed to be regaled, the captain ordering them to play for several hours for the amusement of the crew. This to me was most delightful, especially during the serene evenings we experienced in traversing the Southern Ocean. As for myself, during the day I was constantly occupied at my forge, in refitting or repairing some of the ironwork of the vessel, but principally in making tomahawks, daggers, etc., for the North-West coast.

During the first part of our voyage we saw scarcely any fish, excepting some whales, a few sharks, and flying fish; but after weathering Cape Horn we met with numerous shoals of sea porpoises, several of whom we caught, and as we had been for some time without fresh provisions, I found it not only a palatable, but really a very excellent food. To one who has never before seen them, a shoal of these fish[34] presents a very striking and singular appearance; beheld at a distance coming towards a vessel, they look not unlike a great number of small black waves rolling over one another in a confused manner, and approaching with great swiftness. As soon as a shoal is seen, all is bustle and activity on board the ship, the grains and the harpoons are immediately got ready, and those who are best skilled in throwing them take their stand at the bow and along the gunwale, anxiously awaiting the welcome troop as they come, gambolling and blowing around the vessel, in search of food. When pierced with the harpoon and drawn on board, unless the fish is instantly killed by the stroke, which rarely happens, it utters most pitiful cries, greatly resembling those of an infant. The flesh, cut into steaks and broiled, is not unlike very coarse beef, and the harslet in appearance and taste is so much like that of a hog, that it would be no easy matter to distinguish the one [57] from the other; from this circumstance the sailors have given the name of the herring hog[35] to this fish. I was told by some of the crew, that if one of them happens to free itself from the grains or harpoons, when struck, all the others, attracted by the blood, immediately quit the ship and give chase to the wounded one, and as soon as they overtake it, immediately tear it in pieces. We also caught a large shark, which had followed the ship for several days, with a hook which I made for the purpose, and although the flesh was by no means equal to that of the herring hog, yet to those destitute as we were of anything fresh, I found it eat very well. After passing the Cape, when the sea had become calm, we saw great numbers of albatrosses, a large brown and white bird of the goose kind, one of which Captain Salter shot, whose wings measured from their extremities fifteen feet. One thing, however, I must not omit mentioning, as it struck me in a most singular and extraordinary manner. This was, that on passing Cape Horn in December, which was midsummer in that climate, the nights were so light, without any moon, that we found no difficulty whatever in reading small print, which we frequently did during our watches.

[32] Santa Catharina.

[33] This is now, so far as Great Britain is concerned, a reminiscence of a vanished trade: the South Sea whaling is extinct.

[34] The zoological reader does not require to be told that the porpoise, a very general term applied by sailors to many small species of cetaceans, is not a "fish."

[35] Porc poisson of the French, of which porpoise is simply a corruption.

INTERCOURSE WITH THE NATIVES—MAQUINA—SEIZURE OF THE VESSEL AND MURDER OF THE CREW

In this manner, with a fair wind and easy weather from the 28th of December, the period of our passing Cape Horn, we pursued our voyage to the northward until the 12th of March, 1803, when we made Woody Point in Nootka Sound, on the North-West coast of America. We immediately stood up the Sound for Nootka, where[36] Captain Salter had determined to stop, in order to supply the ship with wood and water before proceeding up the coast to trade. But in order to avoid the risk of any molestation or interruption to his men from the Indians while thus employed, he proceeded with the ship about five miles to the northward of the village, which is situated on Friendly Cove, and sent out his chief mate with several of the crew in the boat to find a good place for anchoring her. After sounding for some time, they returned with information that they had discovered a secure place for anchorage, on the western side of an inlet or small bay, at about half a mile from the coast, near a small island which protected it from the sea, and where there was plenty of wood and excellent water. The ship accordingly came to anchor in this place, at twelve o'clock at night, in twelve fathom water, muddy bottom, and so near the shore that to prevent the ship from winding we secured her by a hawser to the trees.