CONTENTS

CHAPTER II—THE HOUSE OF THE FIRST MEN

CHAPTER III—THE HERMIT'S CRUST

CHAPTER IV—THE MAIDEN OP THE WATERS

CHAPTER VII—THE COUNSEL OP WISDOM

CHAPTER VIII—THE WOMAN ON THE WALL

CHAPTER XI—THE CHART OP THE TREASURE

CHAPTER XII—THE SERVANTS OP YAHVEH

CHAPTER XIV—THE PLACE OP PROPHECY

CHAPTER XV—THE VULNERABLE SPOT

CHAPTER XVI—THE LESSON IN MAGIC

CHAPTER XVII—THE STAIR OF VISIONS

CHAPTER XVIII—THE SIGN BY THE WAY

CHAPTER XIX—THE CHAMBER OP LIGHT

CHAPTER XXI—THE IMPOTENT SPELL

CHAPTER XXIV—THE TASTE OF DEATH

CHAPTER XXVI—THE CITY OF DREAMS

When the train crept out of Euston into the wet night the Marchesa Soderrelli sat for a considerable time quite motionless in the corner of her compartment. The lights, straggling northward out of London, presently vanished. The hum and banging of passing engines ceased. The darkness, attended by a rain, descended.

Beside the Marchesa, on the compartment seat, as the one piece of visible luggage, except the two rugs about her feet, was a square green leather bag, with a flat top, on which were three gold letters under a coronet. It was perhaps an hour before the Marchesa Soderrelli moved. Then it was to open this bag, get out a cigarette case, select a cigarette, light it, and resume her place in the corner of the compartment. She was evidently engaged with some matter to be deeply considered; her eyes widened and narrowed, and the muscles of her forehead gathered and relaxed.

The woman was somewhere in that indefinite age past forty. Her figure, straight and supple, was beginning at certain points to take on that premonitory plumpness, realized usually in middle life; her hair, thick and heavy, was her one unchanged heritage of youth; her complexion, once tender and delicate, was depending now somewhat on the arts. The woman was coming lingeringly to autumn. Her face, in repose, showed the freshness of youth gone out; the mouth, straightened and somewhat hardened; the chin firmer; there was a vague irregular line, common to persons of determination, running from the inner angle of the eye downward and outward to the corner of the mouth; the eyes were drawn slightly at the outer corners, making there a drooping angle.

Her dress was evidently continental, a coat and skirt of gray cloth; a hat of gray straw, from which fell a long gray veil; a string of pearls around her neck, and drop pearl earrings.

As she smoked, the Marchesa continued with the matter that perplexed her. For a time she carried the cigarette mechanically to her lips, then the hand holding it dropped on the arm of the compartment seat beside her. There the cigarette burned, sending up a thin wisp of smoke.

The train raced north, gliding in and out of wet blinking towns, where one caught for a moment a dimly flashing picture of a wet platform a few trucks, a smoldering lamp or two a weary cab horse plodding slowly up a phantom street, a wooden guard, motionless as though posed before a background of painted card board, or a little party of travelers, grouped wretchedly together at a corner of the train shed, like poor actors playing at conspirators in some first rehearsal.

Finally the fire of the cigarette touched her fingers. She ground the end of it against the compartment window, sat up, took off her hat and placed it in the rack above her head; then she lifted up the arm dividing her side of the compartment into two seats, rolled one of her rugs into a pillow, lay down, and covering herself closely with the remaining rug, was almost immediately asleep.

The train arrived at Stirling about 7:30 the following morning. The Marchesa Soderrelli got out there, walked across the dirty wooden platform—preempted almost exclusively by a flaming book stall, where the best English author finds-himself in the same sixpenny shirt with the worst—out a narrow way by the booking office, and up a long cobble-paved street to an inn that was doubtless sitting, as it now sits, in the day of the Pretender.

A maid who emerged from some hidden quarter of this place at the Marchesa's knocking on the window of the office led the way to a little room in the second story of the inn, set the traveler's bag on a convenient chair, and, as if her duties were then ended, inquired if Madam wished any further attendance. The Marchesa Soderrelli wished a much further attendance, in fact, a continual attendance, until her breakfast should be served at nine o'clock. The tin bath tub, round like a flat-bottomed porringer, was taken from its decorative place against the wall and set on a blanket mat. The pots over the iron crane in the kitchen of the inn were emptied of hot water. The maid was set to brushing the traveler's wrinkled gown. The stable boy was sent to the chemist to fetch spirits of wine for Madam's toilet lamp. The very proprietor sat by the kitchen fire polishing the Marchesa Soderrelli's boots. The whole inn, but the moment before a place abandoned, now hummed and clattered under the various requirements of this traveler's toilet.

The very details of this exacting service impressed the hostelry with the importance of its guest. The usual custom of setting the casual visitor down to a breakfast of tea, boiled eggs, finnan haddock, or some indefinite dish with curry, in the common dining room with the flotsam of lowland farmers, was at once abandoned. A white cloth was laid in the long dining room of the second floor, open only from June until September, while the tourist came to do Stirling Castle under the lines of Ms Baedeker, a room salted for the tourist, as a Colorado mine is salted for an Eastern investor. No matter in what direction one looked he met instantly some picture of Queen Mary, some old print, some dingy steel engraving. No two of these presented to the eye the same face or figure of this unhappy woman, until the observer came presently to realize that the Scottish engraver, when drawing the features of his central figure, like the Madonna painters of Italy, availed himself of a large and catholic collection.

To this room the innkeeper, having finished the Marchesa's boots, and while the maid still clattered up and down to her door, brought now the dishes of her breakfast. Porridge and a jug of cream, a dripping comb of heather honey, hot scones, a light white roll, called locally a "bap," and got but a moment before from the nearest baker, a mutton cutlet, a pot of tea, and a brown trout that but yesterday was swimming in the Forth.

When the Marchesa came in at nine o'clock to this excellent breakfast, every mark of fatigue had wholly vanished. Youth, vigor, freshness, ladies, once in waiting to this woman, ravished from her train by the savage days, were now for a period returned, as by some special, marked concession. The maid following behind her, the obsequious innkeeper, bowing by the door, saw and knew instantly that their estimate of the traveler was not a whit excessive. This guest was doubtless a great foreign lady come to visit the romantic castle on the hill, perhaps crossed from France with no object other than this pilgrimage.

The innkeeper waited, loitering about the room, moving here a candlestick and there a pot, until his prints, crowded on the walls, should call forth some comment. But he waited to disappointment. The great lady attended wholly to her breakfast. The "bap," the trout, the cutlet shared no interest with the prints. This man, skilled in divining the interests of the tourist, moved his pots without avail, his candlesticks to no seeming purpose. The Marchesa Soderrelli was wholly unaware of his designing presence.

Presently, when the Marchesa had finished with her breakfast, she took up the silver case, which, in entering, she had put down by her plate, and rolling a cigarette a moment between her thumb and finger, looked about inquiringly for a means to light it. The innkeeper, marking now the arrival of his moment, came forward with a burning match and held it over the table—breaking on the instant, with no qualm, the fourth of his printed rules, set out for warning on the corner of his mantel shelf. He knew now that his guest would speak, and he sorted quickly his details of Queen Mary for an impressive answer. The Marchesa did speak, but not to that cherished point.

"Can you tell me," she said, "how near I am to Doune in Perthshire?"

The innkeeper, set firmly in his theory, concluded that his guest wished to visit the neighboring castle after doing the one at Stirling, and answered, out of the invidious distinctions of a local pride.

"Quite near, my Lady, twenty minutes by rail, but the castle there is not to be compared with ours. When you have seen Stirling Castle, and perhaps Edinburgh Castle, the others are not worth a visit. I have never heard that any royal person was ever housed at Doune. Sir Walter, I believe, gives it a bit of mention in 'Waverley,' but the great Bruce was in our castle and Mary Queen of Scots."

He spoke the last sentence with uncommon gravity, and, swinging on his heel, indicated his engravings with a gesture. Again these prints failed him. The Marchesa's second query was a bewildering tangent.

"Have you learned," she said, "whether or not the Duke of Dorset is in Perthshire?"

"The Duke of Dorset," he repeated, "the Duke of Dorset is dead, my Lady."

"I do not mean the elder Duke of Dorset," replied the Marchesa, "I am quite aware of his death within the year. I am speaking of the new Duke."

The innkeeper came with difficulty from that subject with which his guns were shotted, and, like all persons of his class, when turned abruptly to the consideration of another, he went back to some familiar point, from which to approach, in easy stages, the immediate inquiry.

"The estates of the Duke of Dorset," he began, "are on the south coast, and are the largest in England. The old Duke was a great man, my Lady, a great man. He wanted to make every foreigner who brought anything over here, pay the government something for the right to sell it. I think that was it; I heard him speak to the merchants of Glasgow about it. It was a great speech, my Lady—I seemed to understand it then," and he scratched his head. "He would have done it, too, everybody says, if something hadn't broken in him one afternoon when he was with the King down at Ascot. But he never married. You know, my Lady, every once in a while, there is a Duke of Dorset who does not marry. They say that long ago, one of them saw a heathen goddess in a bewitched city by the sea, but something happened, and he never got her."

"That is very sad," said the Marehesa, "a fairy story should turn out better."

"But that is not the end of the story, my Lady," continued the innkeeper. "Right along after that, every other Duke has seen her, and won't have any mortal woman for a wife." The Marehesa was amused. "So fine a devotion," she said, "ought to receive some compensation from heaven."

"And so it does, my Lady," cried the innkeeper, "and so it does. The brother's son who comes into the title, is always exactly like the old childless Duke—just as though he were reborn somehow." Then a light came beaming into his face. "My Lady!" he cried, like one arrived suddenly upon a splendid recollection. "I have a print of the old Duke just over the fireplace in the kitchen; I will fetch it. Janet, the cook, says that the new Duke is exactly like him."

The Marehesa stopped him. "No," she said, "I would not for the world disturb the decorations of your kitchen."

The thwarted host returned, rubbing his chin. A moment or two he puzzled, then he ventured another hesitating service.

"If it please your Ladyship, I will ask Janet, the cook, about the new Duke of Dorset. Janet reads all about them every Sunday in the Gentle Lady, and she sticks a pin in the map to remind her where the nicest ones are."

Before the smiling guest could interfere with a further negative, the obliging host had departed in search of that higher authority, presiding thus learnedly among his pots. The Marchesa, left to her devices, looked about for the first time at the innkeeper's precious prints. But she looked leisurely, without an attaching interest, until she chanced upon a little wood engraving of Prince Charles Edward Stuart, half hidden behind a luster bowl on the sideboard. She arose, took up the print, and returning to her chair, set it down on the cloth beside her. She was in leisurely contemplation of this picture when the innkeeper returned, sunning, from his interview with Janet. On the forty-three steps of his stairway the good man unfortunately lost the details of Janet's diction, but he came forth triumphant with the substance of her story.

The new Duke of Dorset was, at this hour, in Perthshire. He was not the son of the old Duke, but an only nephew, brought forth from some distant country to inherit his uncle's shoes. His father had married some Austrian, or Russian, or Italian—Janet was a bit uncertain on this trivial point. For the last half dozen years the young Duke had been knocking about the far-off edges of Asia. There had been fuss about his succession, and there might have been a kettle of trouble, but it came out that he had been of a lot of service to the government in effecting the Japanese alliance. He had somehow gotten at the inside of things in the East. So the foreign office was at his back. He had given up, too, some princely station in his mother's country; a station of which Janet was not entirely clear, but, in her mind, somehow, equal to a kingdom. But he gave it up to be a peer of England, as, in Janet's opinion, any reasonable person would. My Lady was rightly on her way, if she wished to see this new Duke.

The Doune Castle and the neighboring estate were shooting property of his father. This property, added to the vast holdings of the old Duke, made the new once perhaps the richest peer in England. He looked the part, too; more splendidly fit than any of his class coming under Janet's discriminating eye. She had gone with Christobel MacIntyre to see him pass through Stirling some weeks earlier. And he was one of the "nicest of them." Janet's pin had been sticking in Doune since August.

The Marchesa did not attempt to interrupt this pleasing flow of data. The innkeeper delivered it with a variety of bows, certain decorative, mincing steps, and illustrative gestures. It came forth, too, with that modicum of pride natural to one who housed, thus opportunely, so nice an observer as this Janet. He capped it at the end with a comment on this Japanese alliance. It did not please him. They were not white, these Japanese. And this alliance—it was against nature. His nephew, Donald MacKensie, had been with the army in China, when the powers marched on Pekin, and there the British Tommy had divided the nations of the earth into three grand divisions, namely, niggers, white men, and dagoes. There were two kinds of niggers—real niggers, and faded-out niggers; there were four kinds of dagoes—vodka dagoes, beer-drinking dagoes, frog-eating dagoes, and the macaroni dagoes; but there was only one kind of white men—"Us," he said, "and the Americans."

The Marchesa laughed, and the innkeeper rounded off his speech with a suggestion of convenient trains, in case my Lady was pleased to go to-morrow or the following day to Doune. A good express left the station here at ten o'clock, and one could return—he marked especially the word—at one's pleasure. The schedule of returning trains was beautifully appointed.

He had arranged, too, in the interval of absence, for the Marchesa's comfort in the morning visit to Stirling Castle. A carriage would take her up the long hill; a guide, whom he could unreservedly recommend, would be there for any period at her service—a pensioned sergeant who had gone into the Zulu rush at Rorke's Drift, and come out somewhat fragmentary. Then he stepped back with a larger bow, like an orator come finally to his closing sentence. Was my Lady pleased to go now?

The Marchesa was pleased to go, but not upon the way so delicately smoothed for her. She arose, went at once to her room, got her hand bag and coat, paid the good man his charges, and walked out of the door, past the cab driver, to her train, leaving that expectant public servant, like the young man who had great possessions, sorrowing.

One, arriving over the Caledonian railway at Doune, will at once notice how that station exceeds any other of this line in point of nice construction. The framework of the building is of steel; the roof, glass; the platform of broad cement blocks lying like clean gray bands along the car tracks. There is here no dirt, no smoke, no creaky floor boards, no obtrusive glaring bookstalls, and no approach given over to the soiling usages of trade. One goes out from the spotless shed into a gravel court, inclosed with a high brick wall, stone capped, planted along its southern exposure with pear trees, trained flat after the manner of the northern gardener.

The Marchesa Soderrelli, following the little street into the village, stopped in the public square at the shop of a tobacconist for a word of direction. This square is one of the old landmarks of Doune. In the center of it is a stone pillar, capped at the top with a quaint stone lion, the work of some ancient cutter, to whom a lion was a fairy beast, sitting like a Skye dog on his haunches with his long tail jauntily in the air, and his wizened face cocked impudently.

From this square she turned east along a line of shops and white cottages, down a little hill, to an old stone bridge, crossing the Ardoch with a single high, graceful span. South of it stood the restored walls of Doune Castle, once a Lowland stronghold, protected by the swift waters of the Teith, now merely the most curious and the best preserved ruin in the North. East of the Ardoch the land rises into a park set with ancient oaks, limes, planes, and gnarled beeches. Here the street crossing the Ardoch ends as a public thoroughfare, and barred by the park gates, continues up the hill as a private road between two rows of plane trees.

The Marchesa opened the little foot gate, cut like a door in the wall of the park beside the larger gate, and walked slowly up the hill, over the dead plane leaves beginning now to fall. As she advanced the quaint split stone roof and high round wall of Old Newton House came prominently into view. This ancient house, one of the most picturesque in Scotland, deserves a word of comment. It was built in 1500 a.d., as a residence for the royal keepers of Doune Castle, and built like that castle with an eye forward to a siege. The stone walls are at some points five feet thick. The main wing of the house is flanked with a semicircular tower, capped with a round crow-step coping. The windows high up in the wall were originally barred with iron; the holes in the stones are still plainly visible. Under the east wing of the house is an arched dungeon with no ray of light; under the west wing, a well for the besieged. A secret opening in the wall of the third story descends under the Ardoch, it is said, to Doune Castle. To the left are the formal gardens inclosed by a tall holly hedge, and to the right, the green sward of the park. The road climbing the hill turns about into a gravel court.

The place is incrusted with legends. Prince Charlie on his daring march south with a handful of Highlanders to wrest a kingdom from the Hanoverian, coming to this stone span by the Ardoch, was met at the park gate by the daughters of the house with a stirrup cup. He drank, as the story runs, and pulling off his glove put down his hand to kiss. But one madcap of the daughters answered, "I would rather prie your mou," and the Prince, kissing her like a sweetheart, rode over the Ardoch to his fortunes.

This old stronghold had originally but one way of entrance cut in the solid wall of the tower. An iron door, set against a wide groove of the stone, held it—barring against steel and fire. The door so low that one entering must stoop his head, making him thus ready for that other, waiting on the stairway with his ax.

This stone stairway ascending in the semicircular tower is one of the master conceptions of the old-time builder. Each step is a single fan-shaped stone, five inches thick, with a round end like a vertebra. These round ends of the stones are set one above the other, making thus a solid column, of which the flat part of each stone is a single step of a spiral stairway. The early man doubtless took here his plan direct from nature, in contemplation of the backbone of a stag twisted about, and going thus to the great Master for his lesson, his work, to this day, has not been bettered. His stairway was as solid and enduring as his wall, with no wood to burn and no cemented joint to crumble.

The Marchesa, having come now to the gravel court before the iron door, found there the brass knob of a modern bell. At her ringing, a footman crossed the court from the service quarter of the house, took her card and disappeared. A moment later he opened the creaking door and led the way up the stone stair into a little landing, a sort of miniature entresol, to the first floor of the house. This cell, made now to do service as a hall, was lighted by a square window, cut in modern days through the solid masonry of the tower. In the corner of it was a rack for walking sticks, and on the row of brass hooks set into the wall were dog whips, waterproofs, a top riding coat, and several shooting capes, made of that rough tweed, hand spun and hand woven, by the peasants of the northern islands, dyed with erotal and heather tips, and holding yet faintly the odor of the peat smoke in which it was laboriously spun.

The footman now opened the white door at the end of this narrow landing, and announced the Marchesa Soderrelli. As the woman entered a man arose from a chair by a library table in the middle of the room.

To the eye he was a tall, clean-limbed Englishman, perhaps five and thirty; his fair hair, thick and close cropped, was sunburned; his eyes, clear and hard, were dark-blue, shading into hazel; his nose, aquiline in contour, was as straight and clean cut as the edges of a die; his mouth was strong and wide; his face lean and tanned. Under the morning sunlight falling through the high window, the man was a thing of bronze, cast in some old Tuscan foundry, now long forgotten by the Amo.

The room was that distinctive chamber peculiar to the English country house, a man's room. On the walls were innumerable trophies; elk from the forests of Norway, red deer from the royal preserves of Prussia, the great branching antlers of the Cashmire stag, and the curious ebon horns of the Gaur, together with old hunting prints and pencil drawings of big game. On the floor were skins. The buffalo, found only in the vast woodlands of Lithuania; the brown bear of Russia, the Armenian tiger. Along the east wall were three rows of white bookshelves, but newly filled; on a table set before these cases were several large volumes apparently but this day arrived, and as yet but casually examined. To the left and to the right of the mantel were gun cases built into the wall, old like the house, with worn brass keyholes, and small diagonal windows of leaded glass, through which one could see black stocks and dark-blue barrels.

Over the mantel in a smoke-stained frame was a painting of the old Duke of Dorset, at the morning of his life, in the velvet cap and the long red coat of a hunter. The face of the painting was, in every detail, the face of the man standing now below it, and the Marchesa observed, with a certain wonder, this striking verification of the innkeeper's fantastic story.

On the table beside the leather chair from which the man had arisen were the evidences of two conflicting interests. A volume of political memoirs, closed, but marked at a certain page with the broad blade of a paper cutter—shaped from a single ivory tusk, its big gray handle pushing up the leaves of the book—and beside it, the bolt thrown open, the flap of the back sight pulled up, was a rifle.

An observer entering could not say, on the instant, with which of these two interests that one at the table had been latest taken. Had he gone, however, to the books beyond him on the wall, he might have fixed in a way the priority of those interests. The thick volumes on the table were the political memoirs of the late Duke of Dorset. The newer books standing in the shelves were exclusively political and historical, having to do with the government of England, speeches, journals, essays, memoirs, the first sources of this perplexing and varied knowledge; while the older, worn volumes, found now and then among them, were records of big-game shooting, expeditions into little known lands, works rising to a scientific accuracy on wild beast stalking, the technic of the rifle, the flight and effect of the bullet, and all the varied gear of the hunter. It would seem that the master of this house, having for a time but one consuming interest in his life, had come now upon a second.

The Duke of Dorset advanced and extended his hand to the woman standing in the door.

"It is the Marchesa Soderrelli," he said; "I am delighted."

The words of the man were formal and courteous, but colored with no visible emotion; a formula of greeting rather, suited equally to a visitor from the blue or one coming, with a certain claim upon the interest, from the nether darkness. The hospitality of the house was presented, but the emotions of the host retained.

The Marchesa put her gloved fingers for a moment into the man's hand.

"I hope," she answered, "that I do not too greatly disturb you."

"On the contrary, Madam," replied the Duke, "you do me a distinction." Then he led her to his chair, and took another at the far end of the table. He indicated the book, the rifle, with a gesture.

"You find me," he said, "in council with these conflicting symbols. Permit me to remove them."

"Pray do not," replied the Marchesa, smiling; "I attach, like Pompey, a certain value to the flight of birds. Signs found waiting at the turn of the road affect me. Those articles have to me a certain premonitory value."

"They have to me," replied the Duke, "a highly symbolic value. They are signposts, under which I have been standing, somewhat like a runaway lad, now on one foot and now on the other." Then he added, as in formal inquiry, "I hope, Madam, that the Marquis Soderrelli is quite well."

A cloud swept over the woman's face. "He is no longer in the world," she said.

The man saw instantly that by bungling inadvertence he had put his finger on a place that ached. This dissolute Italian Marquis was finally dead then. And fragments of pictures flitted for a moment through the background of his memory. A woman, young, beautiful, but like the spirit of man—after the figure of Epictetus—chained invisibly to a corpse. He saw the two, as in a certain twilight, entering the Hotel Dardanelle in Venice; the two coming forth from some brilliant Viennese café, and elsewhere in remote Asiatic capitols, always followed by a word, pitying the tall, proud girl to whom a sardonic destiny had given such beauty and such fortune. The very obsequious clerks of the Italian consulate, to which this Marquis was attached, named him always with a deprecating gesture.

The Duke's demeanor softened under the appealing misery of these fragments. He blamed the thoughtless word that had called them up. Still he was glad, as that abiding sense of justice in every man is glad, when the oppressor, after long immunity, wears out at last the incredible patience of heaven. The Marquis had got, then, the wage which he had been so long earning.

The Duke sought refuge in a conversation winging to other matters. He touched the steel muzzle of the rifle lying on the table.

"You will notice," he said, "that I do not abandon myself wholly to the memoirs of my uncle. I am going out to Canada to look into the Japanese difficulties that we seem to have on our hands there. And I hope to get a bit of big-game shooting. I have been trying to select the proper rifle. Usually, after tramping about for half a day, one gets a single shot at his beast, and possibly, not another. He must, therefore, not only hit the beast with that shot, but he must also bring him down with it. The problem, then, seems to be to combine the shock, or killing power, of the old, big, lead bullet with the high velocity and extreme accuracy of the modern military rifle. With the Mauser and the Lee-Enfield one can hit his man or his beast at a great distance, but the shock of the bullet is much less than that of the old, round, lead one. The military bullet simply drills a little clean hole which disables the soldier, but does not bring down the beast, unless it passes accurately through some vital spot. I have, therefore, selected what I consider to be the best of these military rifles, the Mannlicher of Austrian make, and by modifying the bullet, have a weapon with the shock or killing power of the old 4:50 black powder Express."

The man, talking thus at length with a definite object, now paused, took a cartridge out of the drawer of the table, and set it down by the muzzle of the rifle.

"You will notice," he said, "that this is the usual military cartridge, but if you look closer you will see that the nickel case of the bullet has four slits cut near the end. Those simple slits in the case cause the bullet, when it strikes, to expand. The scientific explanation is that when the nose of the projectile meets with resistance, the base of it, moving faster, pushes forward through this now weakened case and expands the diameter of the bullet, and so long as this resistance to the bullet continues, the expansion continues until there is a great flattened mass of spinning lead."

The Marchesa Soderrelli, visualizing the terrible effect of such a weapon, could not suppress a shudder.

"The thing is cruel," she said.

"On the contrary," replied the man, "it is humane. With such a bullet the beast is brought down and killed. Nothing is more cruel than to wound an animal and leave it to die slowly, or to be the lingering prey of other beasts."

The Duke of Dorset spun the cartridge a moment on the table, then he tossed it back into the drawer.

"I fear," he said, "that I cannot bring quite the same measure of enthusiasm to the duties of this new life. The great mountains, the vast wind-scoured Steppes allure me. I have lived there when I could. I suppose it is this English blood." Again smiling, he indicated the pile of volumes beyond him by the bookcase. "But I have, happily, the assistance of my uncle."

The Marchesa took instant advantage of this opening.

"You are very fortunate," she said; "most of us are taken up suddenly by the Genii of circumstance and set down in an unknown land without a hand to help us."

The Duke's face returned to its serious outlines. "I do not believe that," he said; "there is always aid."

"In theory, yes," replied the Marchesa, "there is always food, clothing, shelter; but to that one who is hungry, ragged, cold, it is not always available."

"The tongue is in one's head," answered the Duke; "one can always ask."

"No," said the woman, "one cannot always ask. It is sometimes easier to starve than to ask for the loaf lying in the baker's window."

"I have tried starving," replied the Duke; "I went for two days hungry in the Bjelowjesha forest; on the third day I begged a wood chopper for his dinner and got it. I broke my leg once trying to follow a wounded beast into one of those inaccessible peaks of the Pusiko. I crawled all that night down the mountain to the hut of a Cossack, and there I begged him, literally begged him for his horse. I had nothing; I was a dirty mass of blood and caked earth; it was pure primal beggary. I got the horse. The heart in every man, when one finally reaches to it, is right. In his way, at the bottom of him, one is always pleased to help. The pride, locking the tongue of the unfortunate, is false."

"Doubtless," replied the Marchesa, "in a state of nature, such a thing is easy. But I do not mean that. I mean the humiliation, the distress, of that one forced by circumstance to appeal to an equal or a superior for aid—perhaps to a proud, arrogant, dominating person in authority."

"I have done that, too," replied the Duke, "and I still live. Once in India I came upon a French explorer of a helpless, academic type. He had come into the East to dig up a buried city, and the English Resident of the native state would not permit him to go on. He had put his whole fortune into the preparation for the work, and I found him in despair. I went to the Resident, a person of no breeding, who endeavored, like all those of that order, to make up for this deficiency with insolence. I was ordered to wait on the person's leisure, to explain in detail the explorer's plan, literally to petition the creature. It was not pleasant, but in the end I got it; and I rather believe that this Resident was not, at bottom, the worst sort, after one got to the real man under his insolence."

The Marchesa recalled vaguely some mention of this incident in a continental paper at the time.

"But," she said, "that was aid asked for another. That is easy. It is aid asked for oneself that is crucifixion."

"If," replied the Duke, "any man had a thing which I desperately needed, I should have the courage to ask him for it."

A tinge of color flowed up into the woman's face.

"I thought that, too," she said, "until I came into your house this morning."

The Duke leaned forward and rested his elbows on the table.

"Have I acted then, so much like that English Resident?" he said. The voice was low, but wholly open and sincere.

"Oh, no," replied the Marchesa, "no, it is not that."

"Then," he said, "you will tell me what it is that I can do."

The woman's color deepened. "It is so common, so sordid," she said, "that I am ashamed to ask."

"And I," replied the Duke, "shall be always ashamed if you do not. I shall feel that by some discourtesy I have closed the lips of one who came trusting to a better memory of me. What is it?"

The woman's face took on a certain resolution under its color. "I have come," she said, "to ask you for money."

The Duke's features cleared like water under a lifting fog. He arose, went into an adjoining room, and returned with a heavy pigskin dispatch case. He set the case on the table, opened it with, a little brass key, took out a paper blank, wrote a moment on it and handed it with the pen to the Marchesa. The woman divining that he had written a check did not at first realize why he was giving her the pen. Then she saw that the check was merely dated and signed and left blank for her to fill in any sum she wished. She hesitated a moment with the pen in her fingers, then wrote "five hundred pounds."

The Duke, without looking at the words that the Marchesa had written, laid the check face downward on a blotter, and ran the tips of his fingers over the back to dry the ink. Then he crossed to the mantel, and pulled down the brass handle of the bell. When the footman entered, he handed the check to him, with a direction to bring the money at once. Then he came back, as to his chair, but pausing a moment at the back of it, followed the footman out of the room.

A doubt of the man's striking courtesy flitted a moment into the woman's mind. Had he gone, then, after this delicate unconcern, to see what sum she had written into the body of the check? She arose quickly and looked out of the high window. What she saw there set her blushing for the doubt. The footman was already going down the road to the village. She was hardly in her chair, smarting under the lesson, when the Duke returned.

"I have taken the liberty to order a bit of luncheon," he said. "This village is not celebrated for its inn."

The Marchesa wished to thank him for this new courtesy, but she felt that she ought to begin with some word about the check, and yet she knew, as by a subtle instinct, that she could not say too little about it.

"You are very kind," she said, "I thank you for this money"; and swiftly, with a deft movement of the fingers, she undid the strand of pearls at her throat, and held it out across the table. "Until I can repay it, please put this necklace in the corner of your box."

The Duke put her hand gently back. "No," he said, his mouth a bit drawn at the corners, "you must not make a money lender of me."

"And you," replied the Marchesa, "must not make a beggar of me. I must be permitted to return this money or I cannot take it."

"Certainly," replied the Duke, "you may repay me when you like, but I will not take security like a Jew."

The butler, announcing luncheon, ended the controversy.

The Marchesa passed through the door held open by the butler, across a little stone passage, into the dining room.

This room was in structure similar to the one she had just quitted, except for the two long windows cut through the south wall—flood gates for the sun. The table was laid with a white cloth almost to the floor. In the center of it was a single silver bowl, as great as a peck measure, filled with fruit, an old massive piece, shaped like the hull of a huge acorn, the surface crudely cut to resemble the outside of that first model for his cup, which the early man found under the oak tree. The worn rim marked the extreme antiquity of this bowl. Somewhere in the faint dawn of time, a smith, melting silver in a pot, had cast the clumsy outline of the piece in a primitive sand mold on the floor of his shop, and then sat down with his model—picked up in the forest—before him on his bench, to cut and hammer the outside as like to nature as he could get it with his tools—the labor of a long northern winter; and then, when that prodigious toil was ended, to grind the inside smooth with sand, rubbed laboriously over the rough surface. But his work remained to glorify his deftness ages after his patient hands were dust. It sat now on the center of the white cloth, the mottled spots, where the early smith had followed so carefully his acorn, worn smooth with the touching of innumerable fingers.

At the end of the room was a heavy rosewood sideboard, flanked at either corner by tall silver cups—trophies, doubtless, of this Duke of Dorset—bearing inscriptions not legible to the Marchesa at the distance. The luncheon set hastily for the unexpected guest was conspicuously simple. The butler, perhaps at the Duke's direction, did not follow into the dining room. The host helped the guest to the food set under covers on the sideboard. Cold grouse, a glass of claret, and later, from the huge acorn, a bunch of those delicious white grapes grown under glass in this north country.

The Duke, having helped the Marchesa to the grouse, sat down beyond her at the table, taking out of courtesy a glass of wine and a biscuit.

"You will pardon this hunter's luncheon," he said; "I did not know how much leisure you might have."

"I have quite an hour," replied the Marchesa; "I go on to Oban at twenty minutes past one."

The answer set the man to speculating on the object of this trip to Oban. He did not descend to the commonplace of such a query, but he lifted the gate for the Marchesa to enter if she liked.

"The bay of Oban," he said, "is thought to be one of the most beautiful in the world. I believe it is a meeting place for yachts at this season."

The Marchesa Soderrelli returned a bit of general explanation. "I believe that a great number of yachts come into the harbor for the Oban Gathering," she answered; "it is considered rather smart for a day or two then."

"I had forgotten the Oban Gathering for the moment," said the Duke. "Does it not seem rather incongruous to attend land games with a fleet of yachts? The Celt is not a person taking especially to water in any form but rain." The Marchesa laughed. "It is the rich wanderer who comes in with his yacht."

"I wonder why it is," replied the Duke, "that we take usually to the road in the extremes of wealth and poverty. The instinct of vagrancy seems to dominate a man when necessity emancipates him."

"I think it is because the great workshop is not fitted with a lounging room," said the Marchesa, "and, so, when one is paid off at the window, he can only go about and watch the fly wheels spin. If there is a little flurry anywhere in the great shop he hurries to it." Then she added, "Have you ever attended a Northern Gathering?"

"No," replied the Duke, "but I may possibly go to Oban for a day of it."

The answer seemed to bring some vital matter strikingly before the Marchesa Soderrelli.

She put down her fork idly on the plate. She took up her glass of claret and drank it slowly, her eyes fixed vacantly on the cloth. But she could have arisen and clapped her hands. The gods, sitting in their spheres, were with her. The moving object of her visit was to get this man to Oban. And he was coming of himself! Surely Providence was pleased at last to fill the slack sails of her fortune.

Then a sense of how little this man resembled the popular conception of him, thrust itself upon her like a thing not until this moment thought of. He was a stranger, almost wholly unknown in England, but the title was known. Next to that of the reigning house it was the greatest in the Empire. The story of its descent to this new Duke of Dorset was widely known. The romance of it had reached even to that Janet, toasting scones in the innkeeper's kitchen. The story, issuing from every press in Europe, was colored like a tale of treasure. But it was vague as to the personality of this incoming Duke. He had been drawn for the reader wholly from the fancy. In the great hubbub he had been painted—like that picture which she had examined in the innkeeper's dining room—young, handsome, a sort of fairy prince. The man, while the sensation ran its seven days, was hunting somewhere in the valley of the Saagdan on the Great Laba, inaccessible for weeks. The romance passed, turning many a pretty head with this new Prince Charlie, coming, as by some Arabian enchantment, to be the richest and the greatest peer in England. Other events succeeded to the public notice. The matter of the succession adjusted itself slowly under the cover of state portfolios, the steps of it coming out now and then in some brief notice. But the portrait of the new Duke remained, as the dreamers had created him, a swaggering, handsome, orphaned lad, moved back into an age of romance.

The reality sat now before the Marchesa Soderrelli in striking contrast to this fancy. A man of five and thirty, hard as the deck of a whale ship; his hair sunburned; the marks of the wilderness, the desert, the great silent mountains stamped into his bronze face; his hands sinewy, callous; his eyes steady, with the calm of solitudes—an expression, common to the eye of every living thing dwelling in the waste places of the earth.

"You will come to Oban?" she said, putting down her cup and lifting her face, brightened with this pleasing news. "I am delighted. The Duke of Dorset will be a great figure at this little durbar. Perhaps on some afternoon there, when you are tired of bowing Highlanders, you will permit me to carry you off to an American yacht." She paused a moment, smiling. "Now, that you are a great personage in England, you should give a bit of notice to great personages in other lands. The peace of the world, and all that, depends, we are told, on such social intermixing. I promise you a cup of tea with a most important person." Then she laughed in a cheery note.

"You will pardon the way I run on. I do not really depend on the argument I am making. I ought rather to be quite frank; in fact, to say, simply, that an opportunity to present the Duke of Dorset to my friends will help me to make good a little feminine boasting. I confess to the weakness. When the romance of your succession to the greatest title in England was being blown about the world, I could not resist a little posing. I had seen you in various continental cities, now and then, and I boasted it a bit. I added, perhaps, a little color to your imaginary portrait. I stood out in the gay season at Biarritz as the only woman who actually knew this fairy prince. King Edward was there, and with him London and New York. You were the consuming topic, and this little distinction pleased my feminine vanity."

The Marchesa smiled again. "It seems infinitely little, doesn't it? And to a man it would be, but not so to a woman. A woman gets the pleasure of her life out of just such little things. You must not measure us in your big iron bushel. If you take away our little vanities, our flecks of egotism, our bits of fiction, you leave us with nothing by which we can manage to be happy. And so," she continued, lowering her eyes to the cloth and tapping the rim of the plate with her fingers, "if the Duke of Dorset appears in Oban and does not know me, I am conspicuously pilloried."

It was not possible to determine from the man's face with what internal comment he took this feminine confession. He arose, filled the Marchesa's glass, set the decanter on the table, and returned to his chair; then he answered.

"If I should attend this Gathering," he said, "I will certainly do myself the honor of looking you up."

The words rang on the Marchesa Soderrelli like a rebuke descended from the stars. She might have saved herself the doubtful effect of her ingenuous confession.

The man's face gave no sign. He was still talking—words which the Marchesa, engrossed with the various aspects of her error, did not closely follow. He was going on to explain that he was just setting out for Canada, but if he had a day or two he would likely come to Oban. He was curious to see a Highland Gathering. And if he came he would be charmed to know the Marchesa's friends—to see her again there, and so forth.

The Marchesa Soderrelli murmured some courteous platitudes, some vague apology, and arose from the table. The Duke held back the door for her to pass and then followed her into the next room. There the Marchesa, inquiring the hour, announced that she must go. She said the words with a bit of brightened color, with visible confusion, and remained standing, embarrassed, until the Duke should put into her hands the money which he had sent for. But he did not do it. He bade her a courteous adieu.

A certain sense of loss, of panic, enveloped her. This man had doubtless forgotten, but she could not remind him. She felt that such words rising now into her throat, would choke her. The butler stood there by the door. She walked over to it, bowed to the Duke remaining now by his table as he had been when she had first crossed the threshold; then she went out and slowly down the stone stairway, empty handed as she had come that morning up it. At every step, clicking under her foot, the panic deepened. She had not two sovereigns remaining in her bag. She was going down these steps to ruin.

As the butler, preceding her, threw open the iron door to the court, she saw, in the flood of light thus admitted, a footman standing at the bottom of the stairway, holding a silver tray, and lying on it a big blue envelope sealed with a splash of red wax.

The whine of innumerable sea gulls awoke the Marchesa Soderrelli. She arose and opened the white shutters of the window.

A flood of sun entered—the thin, brilliant, inspiring sun of the sub-Arctic. A sun to illumine, to bring out fantastic colors, to dye the sea, to paint the mountains, to lay forever on the human heart the mysterious lure of the North. A sun reaching, it would seem, to its farthest outpost. A faint sheet of the thinnest golden light, fading out into distant colors, as though here, finally, one came to the last shore of the world. Beyond the emerald rim of the distant water was utter darkness, or one knew not what twilight sea, sinister and mystic, undulating forever without the breaking of a wave crest, in eternal silence. Or beyond that blue, smoky haze holding back the sun, were to be found all those fabled countries for which the human heart has desired unceasingly, where every man, landing from his black ship, finds the thing for which he has longed, upward from the cradle; that one bereaved, the dead glorified, and that one coming hard in avarice, red and yellow gold.

The bay of Oban on such a morning, under such a sun, surpasses in striking beauty the bay of Naples. The colors of the sea seem to come from below upward. The Firth of Lorn is then the vat of some master alchemist, wherein lies every color and every shade of color, varying with the light, the angle of incidence, the traveling of clouds; and yet, always, the waters of that vat are green, viscous, sinister. The rocks, rising out of this sea, look old, wrinkled, drab. The mountains, hemming it in, seem in the first lights of the morning covered loosely with mantles of worn, gray velvet—soft, streaked with great splashes of pink powder, as though some careless beauty had spilled her cosmetic over the cover of her table.

To the Marchesa Soderrelli, on this morning, the beauties of this north outpost of the world were wholly lost. The whining of the gulls, of all sounds in the heaven above the most unutterably dreary, had brought her to the window, and there a white yacht, lying in the bay, held exclusively her attention. It was big, with two oval stacks; the burger of the Royal Highland Yacht Club floated from its foremast and the American flag from its jack staff. From its topmast was a variegated line of fluttering signals. Beyond, crowding the bay, were yachts of every prominent club in the world, from the airy, thin sailing craft with its delicate lines to the steamer with its funnels.

The woman, looking from this window, studied the triangular bits of silk descending from the topmast, like one turning about a puzzle which he used to understand. For a time the signal eluded her, then suddenly, as from some hidden angle, she caught the meaning. She laughed, closed the window, and began hurriedly with those rites by which a woman is transformed from the toilet of Godiva to one somewhat safer to the eye. When that work was ended she went down to the clerk's window, gave a direction about her luggage, and walked out of the hotel along the sea wall to the beach. There the yacht's boat with two sailors lay beside a little temporary wooden pier, merely a plank or two on wooden horses. She returned the salute of the two men with a nod, stepped over the side, and was taken, under the flocks of gulls maneuvering like an army, to the yacht. But before they reached it the Mar-chesa Soderrelli put her hand into the water and dropped the silver case, that had been, heretofore, so great a consolation. It fled downward gleaming through the green water. She was a resolute woman, who could throttle a habit when there was need.

On the yacht deck a maid led the Marchesa down the stairway through a tiny salon fitted exquisitely, opened a white door, and ushered her into the adjoining apartment. This apartment consisted of two rooms and a third for the bath. The first which the Marchesa now entered was a dressing room, finished in white enamel, polished dull like ivory—old faintly colored ivory—an effect to be got only by rubbing down innumerable coats of paint laboriously. The floor was covered with a silk oriental rug glistening like frost, lying as close to the planks as a skin. A beautiful dressing table was set into the wall below a pivot mirror; on this table were toilet articles in gold, carved with dryads, fauns, cupids, and piping satyrs in relief. A second table stood in the center of the room, covered with a cloth. Two mirrors, extending from the ceiling to the floor, were set into the walls, one opposite to the other. These walls were paneled in delicate rose-colored brocade.

The second room was a bedchamber, covered with a second of those rugs, upon which innumerable human fingers had labored, under a tropic sun, until age doubled them into their withered palms. The nap of this rug was like the deepest yielding velvet, and the colors bright and alluring. The first rug, with its shimmering surface, was evidently woven for a temple, a thing to pray on; but this second had been designed for domestic uses, under a sultan's eye, with nice discrimination, for a cherished foot.

This room contained a bedstead of inlaid brass and hangings of exquisite silk. The ripple and splash of the bath told how the occupant of this dainty apartment was engaged—in green sea water like that Aphrodite of imperishable legend. Water, warmed by the trackless currents of the gulf, cooled by wandering ice floes; of mightier alchemy to preserve the gloss of firm white shoulders, and the alluring hues of bright, red blood glowing under a satin skin, than the milk of she asses, or the scented tubbings of Egypt.

The Marchesa Soderrelli entering was greeted by a merry voice issuing from the bath of splashing waters.

"Good morning," said the voice, "could you read my signal?"

"With some difficulty," replied the Marchesa; "one does not often see an invitation to breakfast dangling from a topmast."

The voice laughed among the rippling waters.

"Old Martin was utterly scandalized when I ordered him to run it up, but Uncle had gone ashore somewhere, and I remained First Lord of the Admiralty, so he could not mutiny. It was obey or go to the yardarm. For rigorous unyielding etiquette, give me an English butler or an American yacht captain."

"It was rather unconventional," replied the Marchesa.

"Quite so," the voice assented, "but at the same time it was a most practical way of getting you here promptly to breakfast with me. This place is crowded with hotels. I did not know in which of them you were housed, and it would have taken Martin half a day to present himself formally to all the hall porters in Oban."

Then the voice added, "I am breaking every convention this morning. I invite you to breakfast by signal, and I receive you in my bath."

"This latter is upon old and established authority, I think," replied the Marchesa. "It was a custom of the ancient ladies of Versailles, only you do not follow it quite to the letter. The bath door is closed."

"I am coming out," declared the voice.

"If you do," replied the Marchesa, "I shall not close my eyes, even if they shrivel like those of that inquisitive burgher of poetic memory." The voice laughed and the door opened.

It is quite as well perhaps that photography was unknown to the ancients; that the fame of reputed beauties rests solely upon certain descriptive generalities; words of indefinite and illusive meaning; various large and comprehensive phrases, into which one's imagination can fill such detail as it likes. If they stood before us uncovered to the eye, youth, always beautiful, would in every decade shame them with comparison. The historical detective, following his clew here and there among forgotten manuscripts, has stripped them already of innumerable illusions. We are told that Helen was forty when she eloped to Ilium, and, one fears, rather fat into the bargain; that Cleopatra at her heyday was a middle-aged mother; that Catherine of Russia was pitted with the smallpox; and, upon the authority of a certain celebrated Englishman, that every oriental beauty cooing in Bagdad was a load for a camel.

It is then the idea of perennial youth, associated by legend with these names, that so mightily affects us. As these beauties are called, it is always the slim figure of Daphne, of Ariadne, of Nicolette, as under the piping of Prospero, that rises to the eye—fresh color, slender limbs, breasts like apples—daughters of immortal morning, coming forth at dawn untouched as from the silver chamber of a chrysalis. It is youth that the gods love!

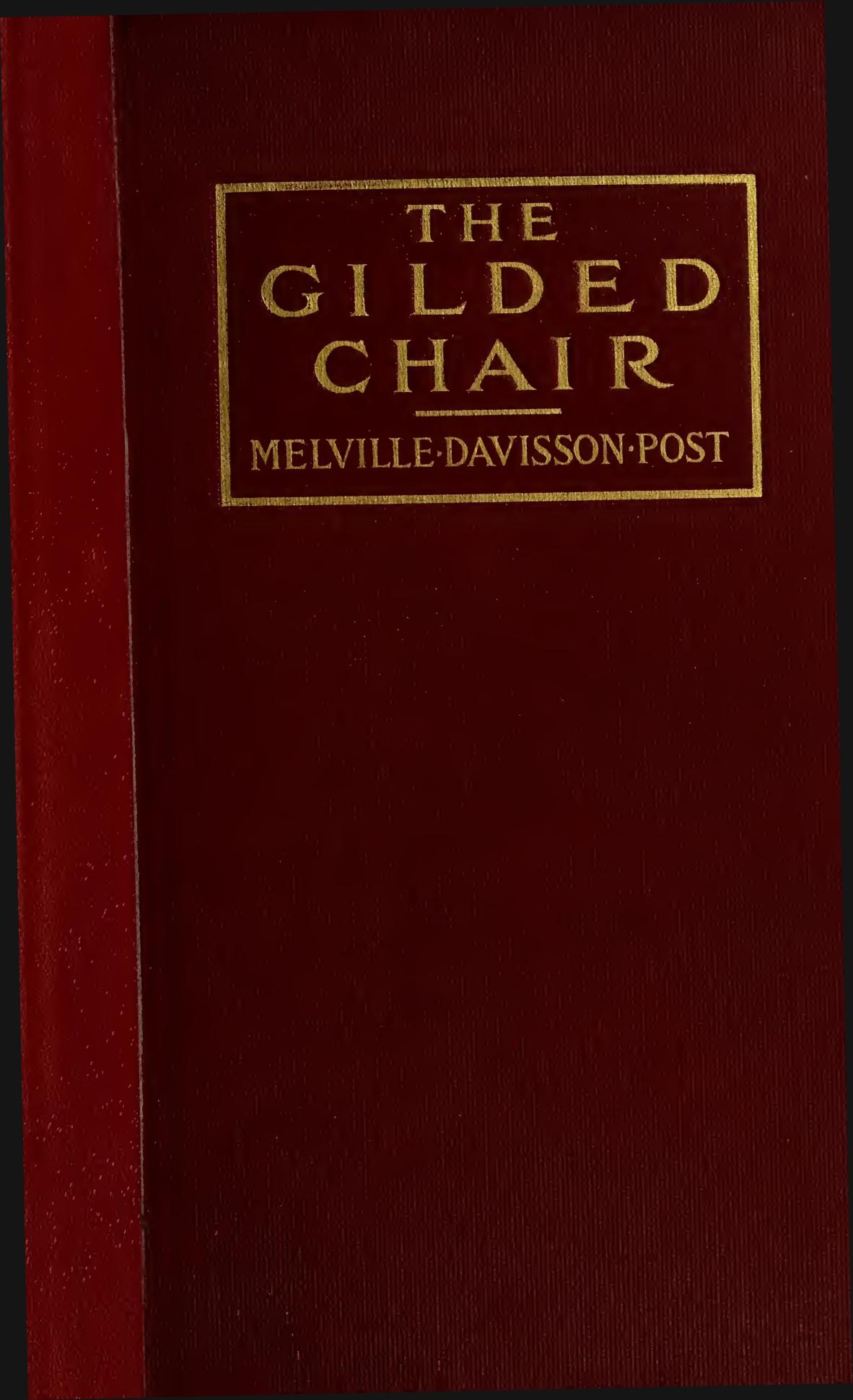

And it was youth, fresh, incomparable youth, that came now through the bath door. A girl packed yet into the bud; slender, a little tall, a little of authority, perhaps in the carriage of the head, a bit of hauteur maybe in the lifting of the chin—but gloriously young. Her hair, long, heavy, in two wrist-thick plaits, fell on either side of her face to her knees over a rose-colored bath robe of quilted satin. This hair was black; blue against the exquisite whiteness of the skin; purple against the dark-rose-colored quiltings. Her eyes, too, were black; but they were wide apart, open, and thereby escaped any suggestion of that shimmering, beady blackness of Castilian women. Their very size made this feature perhaps too prominent in the girl's face. It is a thing often to be noticed, as though the eye came first to its maturity, and disturbed a little the harmony of features not yet wholly filled in. But it is a beauty to be had only from the cradle, and for that reason priceless.

"Oh, Caroline," cried the Marchesa, rising, "you are so splendidly, so gloriously young!" The girl laughed. "It is a misfortune, Marchesa, from which I am certain to recover."

"Oh," continued the woman, drinking in the girl from her dainty feet, incased in quaint Japanese sandals, to the delicate contour of her bosom, showing above the open collar of the robe. "If only one could be always young, then one could, indeed, be always beautiful; but each year is sold to us, as it goes out it takes with it some bit of our priceless treasure, like evil fairies, stealing sovereigns from a chest, piece by piece, until the treasure is wholly gone."

She paused, as though caught on the instant by some returning memory of a day long vanished, when she saw, reflected from a glass, on such a morning, a counterpart of this splendid picture, only that girl's hair was gold, and her eyes gray, but she was slim, too, and brilliantly colored and alluring.

Then she continued: "The bit taken seems a very little, a strand of hair, a touch of color, the almost imperceptible lessening of a perfect contour, but in the end we are hags."

"Then," replied the girl, smiling, "I beg that I may become, in the end, such a hag as the Marchesa Soderrelli."

"Child," said the woman, still speaking as though moved by the inspiration of that picture, "beg only for youth, in your prayers, as the Apostle would say it, unceasingly. If you should be given a wish by the fairies, or three wishes, let them all be youth. Women arriving at middle life adhere to the Christian religion upon the promise of a resurrection of the body. Were that promise wanting, we should be, to the last one, pagans."

"But, Marchesa," replied the girl, "old, wise men tell us that the mind is always young."

There was something adverse to this wisdom in the girl's soft voice; a voice low, lingering, peculiar to the deliberate peoples of the South.

The Marchesa made a depreciating gesture. "My dear," she said, "what man ever loved a woman for her mind! What Prince Charming ever rode down from his enchanted palace to wed a learned prig, doing calculus behind her spectacles! The sight would set the sides of every god in his sphere shaking. It is always the lily lass, the dainty maiden of red blood and dreams, the slim youngling of gloss and porcelain that the Prince takes up, after adventures, into his saddle. Every man born into this world is at heart a Greek. Learning, cleverness, and wisdom he may greatly, he may extravagantly, admire, but it is beauty only that he loves. He may deny this with a certain heat, with well-turned and tripping phrases, with specious arguments to the ear sound, but, believe me for a wise old woman, it is a seizure of unconscionable lying."

A soft hand put for a moment into that of the Marchesa, a wet cheek touched a moment to her face, brought her lecture abruptly to a close.

"I refuse," replied the girl, laughing, "to do lessons before breakfast even under so charming a teacher as the Marchesa Soderrelli."

Then she went into the bedchamber of the apartment, and sent a maid to order breakfast laid on the Buhl table in the dressing room. The maid returned, removed the cover, placed a felt pad over the exquisite face of the table, and on that a linen cloth with a clock center, and borders of Venetian point lace. Upon this the breakfast, brought in by a second maid, was set under silver covers. While these preparations went swiftly forward, the young woman, concerned with the details of her toilet, maintained a running conversation with the Marchesa Soderrelli.

"Did you find that fairy person, the Duke of Dorset?"

"Yes," replied the Marchesa, "at Doune in Perthshire."

"Charming! Will he come to Oban?"

"He will come," answered the Marchesa.

"How lovely!" And then a volley of queries upon that alluring picture which the press of Europe had drawn in fancy of this mysterious Duke—queries which the inquisitive young woman herself interrupted by coming, at that moment, through the door. She now wore slippers and a dressing gown of silk, in hunters' pink, embroidered with Japanese designs, but her hair in its two splendid plaits still hung on either side of her face, over the red folds of the gown, as they had done over the quiltings of the bath robe. She sat down opposite the Marchesa at the table, in the subdued light of this sumptuous apartment.

The picture thus richly colored, set under a yacht's deck in the bay of Oban, belonged rather behind a casement window, opening above a blue sea, in some Arabian story. The beauty of the girl, the barbaric richness of the dressing gown, her dark, level eyebrows, the hair in its two plaits, were the distinctive properties of those first women of the earth glorified by fable. But the girl responding visibly to these ancient extravagances, was, in mental structure, aptly fitted to her time. The wisdom of the débutante lay in her mouth.

"And now, Marchesa," she said, balancing her fork on the tips of her fingers, "tell me all about him."

The Highland Gathering is a sort of northern durbar, and of an antiquity equaling those of India.

The custom of the Scottish clans to meet for a day of games, piping and parade, had its origin anterior to the running of the Gaelic memory. A durbar it may be called, and yet a contrast in that word cannot be laid here alongside the gorgeous pageant of Delhi. The word may stand, albeit, in either case equally descriptive. Both are Gatherings. The distinction lies not in the essential and moving motive of the function, but in the diametric differences of the races. The Orient contrasted against the North. The rajah in his cape of diamonds, attended by his retinue, stripped of: his Eastern splendor, is but a chief accompanied by his "tail." The roll of skin drums is a music of no greater mystery to the stranger than the whine of pipes. The fakirs, the jugglers of India, disclose the effeminate nature of the East, while the games of the Highland disclose equally the hardy nature of the North.

Here under this cis-Arctic sun can be displayed no vestige of that dazzling splendor, making the oriental gathering a saturnalia of gems and color. But one will find in lieu of it hardy exhibitions of the strength, the courage, the endurance, the indomitable unflagging spirit that came finally to set an English Resident in every state of India.

The games of the Oban Gathering are in a way those to be seen at Fort William, Inverness, and elsewhere in the North; the simple sturdy contests of the first men, observed by Homer, and to be found in a varying degree among all peoples not fallen to decadence. Wrestling as it was done, doubtless, before Agamemnon; the long jump; the putting of the stone; the tossing of the caber, a section of a fir tree, and to be cast so mightily that it turns end over in the air, a feat of strength possible only to fingers thick as the coupling pins of a cart and sinews of iron; the high vault, not that theatrical feat of a college class day, but a thing of tremendous daring, learned among the ice ledges of Buachaill-Etive, when the man's life depended on the strength lying in his tendons. Contests, also, of agility, unknown to any south country of the world; the famous sword dance, demanding incredible swiftness and precision; the Sean Triubhais; the Highland fling, a Gaelic dance requiring limbs oiled with rangoon and strung with silk, a dance resembling in no heavy detail its almost universal imitation; a thing, light, fantastic, airy, learned from the elfin daughters dancing in the haunted glens of the Garry, from the kelpie women shaking their white limbs in the boiling pools of the Coe.

But it is not for these field sports that butterflies swarm into the bay of Oban. A certain etiquette requires, however, that one should go for half an hour to these games; an etiquette, doubtless, after that taking the indolent noble, once upon a time, to the Circus Maximus; having its origin in the custom of the feudal chiefs, to lend the splendor of their presence to these animal contests. One finds, then, on such a day, streams of fashionable persons strolling out to the field in which these games are held, and returning leisurely along the road to Oban. Adequate carriages cannot be had, and one goes afoot. The sun, the bright heaven, the gala air of the bedecked city, the color and distinctive dresses of the North, lend to the scene the fantastic charm of a masquerade.

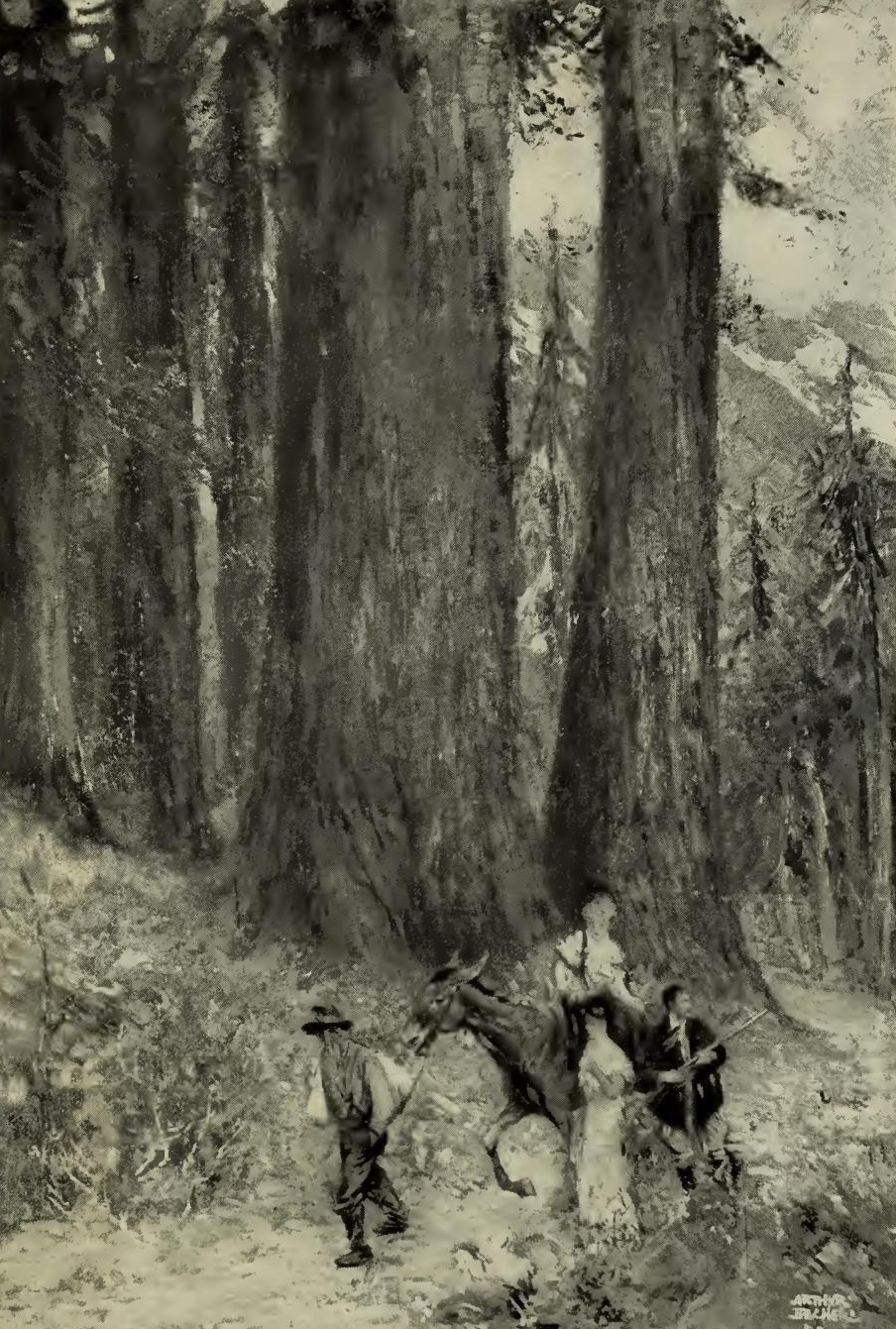

At noon, on the second day of the Gathering, the Duke of Dorset came through the turnstile of the field into this road, following, at some paces, two persons everywhere conspicuously noticed. The two were of so strikingly a relation that few eyes failed to notice that fitness. The observers' interest arose at it wondering. In the fantastic gala mood of such a day, one came easily to see, passing here, in life, under his eye, that perfect sample of youth and age—that king and that king's daughter—of which the legend has descended to us through the medium of stories told in the corner by the fire. Those two running through every tale of mystery, coming now, unknown, as if by some enchantment. The girl, dark eyed, dark haired, smiling. Her white cloth gown fitting to her figure; her drooping hat loaded with flowers of a delicate blossom. The man, old, but unbent and unwithered, and walking beside her with a step that remained firm and elastic. He was three inches less in stature than the Duke of Dorset, but he looked quite as tall. He was old—eighty! But his hair was only streaked with white, and his body was unshrunken, save for the rising veins showing in his hands and throat. He might have appeared obedient to some legend; his face fitted to the requirements of such a fancy. Here was the bony, crooked nose of the tyrant, the eyes of the dreamer—of one who imagines largely and vastly—and under that face, like an iron plowshare, sat the jaw that carries out the dream. And from the whole body of the man, moving here in the twilight of his life, vitality radiated.

The two, mated thus picturesquely, caught and stimulated the fancy of the crowds of natives thronging the road to Oban. Little children, holding wisps of purple heather tied with bits of tartan ribbon, ran beside them, and forgot, in their admiration, to offer the bouquets for a sixpence; a dowager duchess, old and important, looked after the pair through the jeweled rims of her lorgnette; she was gouty and stout now, but once upon a time, slim like that girl, she had held a ribbon dancing with the exquisite prince sitting now splendidly above the land, and the picture recalled by this youth, this beauty, was a memory priceless. Once a soldier of some northern regiment saluted, moved by a deference which he gave himself no trouble to define; and once a Fort William piper, touched somewhere in the region of his fancies, struck up one of those haunting airs inspired by the Pretender—=

```"Speed, bonnie boat, like a bird on the wing.

````'Onward!' the sailors cry.

```Carry the lad that was born to be King

````Over the sea to Skye—-"=

preserving forever in the memory the weird cry of gulls, the long rhythmic wash of the sea, and the loneliness of Scotland.

But the impression that seized and dominated the Duke of Dorset was that he knew these two persons. Not as living people—never in his life had he seen either of them as living people. But in some other way, as, for example, pictures out of some nursery story book come to life. And yet, not quite that. The knowledge of them seemed to emerge from that mysterious period of childhood, existing anterior to the running of the human memory. And he tried to recall them as a child tries to recall the language of the birds which he seems once to have understood, or the meaning of the pictures which the frost etches on the window pane—things he had once known, but had somehow forgotten.

The idea was bizarre and fantastic, but it was strangely compelling, and he followed along the road, obsessed by the mood of it.

Presently, as the old man now and then looked about him, his bearing, the contrasts in his face, the strange blend of big dominating qualities, suggested something to the Duke of Dorset which he seemed recently to have known—a relation—an illusive parallel, which, for a time, he was unable definitely to fix. Then, as though the hidden idea stepped abruptly from behind a curtain, he got it.

On certain ruins in Asia, one finds again and again, cut in stone, a figure with a lion body, eagle wings, and a human face—that mysterious symbol formulated by the ancients to represent the authority that dominates the energies of the world.

But it was the other, this girl with the dark eyes, the dark hair, the slender, supple body, that particularly disturbed him. He could not analyze this feeling. But he knew that if he were a child, without knowing why, without trying to know why, he would have gone to her and said, "I am so glad you have come." And he would have been filled with the wonder of it. So it would have been with him before the years stripped him of that first wisdom; and yet, now at maturity, stripped of it, the impulse and the wonder remained.

The Duke of Dorset continued to walk slowly, at a dozen paces, behind these two persons. He wore the dress usual to a north-country gentleman—a knickerbocker suit of homespun tweed, with woolen stockings and the low Norwegian shoes, with thin double seam running around the top of the foot. This costume set in relief the man's sinewy figure. Among those contesting in the field, which they were now leaving, there was hardly to be found, in physique, one the equal of this Duke. Thicker shoulders and bigger muscles were to be seen there, but they belonged to men slow and heavy like the Clydesdale draft horse. The height, the symmetry, the even proportions of the Duke of Dorset were not to be equaled. Moreover, the man was lean, compact and hard, like a hunter put by grooms, with unending care, into condition.

This he had got from following the spoor of beasts into the desolation of wood and desert; from the clean air of forests, drawn into lungs sobbing with fatigue; from the sun hardening fiber into iron, leaching out fat, binding muscles with sheathings of copper; from bread, often black and dry; meat roasted over embers, and the crystal water of springs. It was that gain above rubies, with which Nature rewards those walking with her in the waste places of the earth.

Ordinarily, such a person would have claimed the attention of the crowds along the road to Oban, but here, behind this old man and this girl, he was unnoticed.

The day was perfect. From the sea came the thin, weird cry of gulls, from the field behind him, the wail of pipes. Presently the two persons whom he followed stopped to speak with some one in a shop, and he overtook them on the road.

At this moment the Marchesa Soderrelli came through the shop door.

The Duke of Dorset had gone to tea on the American yacht. It was a thing which he had not intended to do when he came to Oban. The general conception of that nation current on the Continent of Europe had not impressed him with the excellence of its people. The United States of America was thought to be a sort of Spanish Main, full of adventurers, where no one of the old, sure, established laws of civilization ran. A sort of "house of refuge" for the revolutionary middle class of the world—the valet who would be a gentleman, the maid who would he a lady. It was a country of pretenders, posers, actors. Those who came out of it with their vast, incredible fortunes were, after all, only rich shopkeepers. They were clever, unusually clever, but they were masqueraders.

But, somehow, he could not attach either the one or the other of these two persons to this conception of the United States of America.

He did not stop to consider whether this curious old man, whose face, whose body, whose big, dominant manner recalled in suggestion those stone figures covered with vines forgotten in Asia, was a mere powerful bourgeois, grown rich by some idiosyncrasy of chance, a mere trader taking over with a large hand the avenues of commerce, a mere, big tropical product of a country, in wealth-producing resources itself big and tropical; or one of another order who had drawn this nation of middle class exiles under him, as in romances some hardy marquis had made himself the king of outlaws.

Nor did he stop to consider whether this girl was a new order of woman evolved out of the exquisite blend of some choice alien bloods.

The thing that moved him was the dominion of that mood already on him when the Marchesa Soderrelli came so opportunely through the shop door.

Let us explain that sensation as we like. One of those innumerable hypnotic suggestions of Nature drawing us to her purpose, or a trick of the mind, or some vagrant memory antedating the experiences of life. The answer is to seek. The philosopher of Dantzic was of the first opinion, our universities of the second, and the ancients of the third. One may stand as he pleases in this distinguished company. Certain it is, that, when human reason was in its clearest luster, old, wise men, desperately set on getting at the truth, were of the opinion that some shadowy memories entered with us through the door of life.

Caroline Childers poured the tea and the Duke of Dorset sat with his eyes on her. He seemed to see before him in this girl two qualities which he had not believed it possible to combine: The first delicate sheen of things newly created, as, for instance, the first blossom of the wild brier, that falls to pieces under the human hand, and an experience of life. This young girl, who, at such an age in any drawingroom of Europe, would be merely a white fragment in a corner, was here easily and without concern taking the first place. The little party was, in a sense, a thing of fragments.

Cyrus Childers was talking. The Duke was watching the young girl, and replying when he must. The Marchesa Soderrelli sat with her hands idly in her lap and her eyes narrowed, looking out at something in the harbor.

It was an afternoon slipped somehow through the door of heaven. The sea dimpled under a sheet of sun. The bay was covered with every manner of craft, streaming with pennants, yachts from every country of Europe in gala trimmings. It was as though the world had met here for a festival. Crews from rival yacht clubs were rowing. The bay was full of music, laughter, color, if one looked straight out toward Loch Lynne, but, if off toward the open water, following the Marchesa's eyes, he saw on the edge of all this music, these lights, this color, this swimming fête, the gray looming bulk of a warship, with her long, lean steel back, and her dingy turrets, lying low in the sea, as though she had this moment emerged from the blue water—as though she were some deep-sea monster come up unnoticed on the border of this festival.

The Marchesa interrupted the conversation.

"Do you know what that reminds me of?" she said, indicating the warship. "It reminds me of the silent Iroquois that used always to attend the Puritan May Days."

Cyrus Childers replied in his big voice.

"Are you seeing the yellow peril, Marchesa?" he said.

"I don't like it," she replied. "It seems out of place. Every other nation that we know is here, dancing in its ribbons around the May pole, and there stands the silent Iroquois in his war paint."

"Perhaps," said Caroline Childers, "the little brown man came in the only clothes he had."

"I think Miss Childers has it right," said the Duke of Dorset. "I think the brown man came in the only clothes he had, and he has possessed these clothes only for a fortnight."

"Is it a new cruiser, then?" said Mr. Childers.

"It was built on the Clyde for Chile, I think," replied the Duke, "and the Japanese Government bought it on the day it was launched."

"How like the Oriental," said the Marchesa, "to keep the purchase a secret until the very day the warship went into the sea. Other nations build their ships in the open; this one in the dark. She pretends to be poor; she shows us her threadbare coat; she takes our ministers to look into her empty treasury, but she buys a warship. How true it is that the Anglo-Saxon never knows what is in the 'back' of the oriental mind."

"Perhaps," said Caroline Childers, "we are quite as puzzling to the Oriental."

"That is the very point of it," replied the Marchesa. "They do not understand each other and they never will. They are oil and water; they will not mix. They can only be friends in make-believe, and therefore they must be enemies in reality. Why do we deceive ourselves? In the end the world must be either white, or it must be yellow."

"Such a conclusion," said the Duke of Dorset, "seems to me to be quite wrong. Certain portions of the earth are adapted to certain races. Why should not these races retain them, and when they have approached a standard of civilization, why should they not be admitted into the confederacy of nations?"

"I do not know a doctrine," replied the Mar-chesa, "more remote from the colonial policy of England."

"Do you always quite understand England?" said the Duke. "Here, for instance, is a new and enlightened nation, arising in the East. We do not set ourselves to beat it down and possess its islands. We welcome it; we open the door to it."