The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Man, by Elbert Hubbard

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Man

A Story of To-day

Author: Elbert Hubbard

Release Date: May 11, 2016 [EBook #52049]

Language: English

Character set encoding: UTF-8

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK THE MAN ***

Produced by Craig Kirkwood, Demian Katz and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net (Images

courtesy of the Digital Library@Villanova University

(http://digital.library.villanova.edu/).)

The Table of Contents was created by the transcriber and placed in the public domain.

Images for some complicated pages are included, and the formats of the digital versions of those pages were simplified for improved legibility.

Additional Transcriber’s Notes are at the end.

CONTENTS

THREE OPEN LETTERS.

CHAPTER I. MYSELF.

CHAPTER II. OURSELVES.

CHAPTER III. A LITTLE LOCAL HISTORY.

CHAPTER IV. SOME THINGS.

CHAPTER V. LOST.

CHAPTER VI. THE LOG CABIN.

CHAPTER VII. THE MAN.

CHAPTER VIII. FIRST SUNDAY—A LOOK AROUND.

CHAPTER IX. MARTHA HEATH.

CHAPTER X. SECOND SUNDAY—TO THE WOODS AWAY.

CHAPTER XI. IS IT SO?

CHAPTER XII. THIRD SUNDAY—PRELIMINARY.

CHAPTER XIII. FOURTH SUNDAY—ATMOSPHERE.

CHAPTER XIV. FIFTH SUNDAY—A REVELATION.

CHAPTER XV. SHAKESPEARIANA—“TRUTH, LORD.”

CHAPTER XVI. SIXTH SUNDAY—THE MAN CONTINUES THE TRUE STORY OF SHAKESPEARE.

CHAPTER XVII. THOSE TWO.

CHAPTER XVIII. SEVENTH SUNDAY.—THE SECRET OF SUCCESS.

CHAPTER XIX. EIGHTH SUNDAY—WOMAN’S LOVE.

CHAPTER XX. THE ARREST.

CHAPTER XXI. PERSECUTION.

CHAPTER XXII. BY THE WAY.

CHAPTER XXIII. THE FREEZER.

CHAPTER XXIV. THE TRIAL.

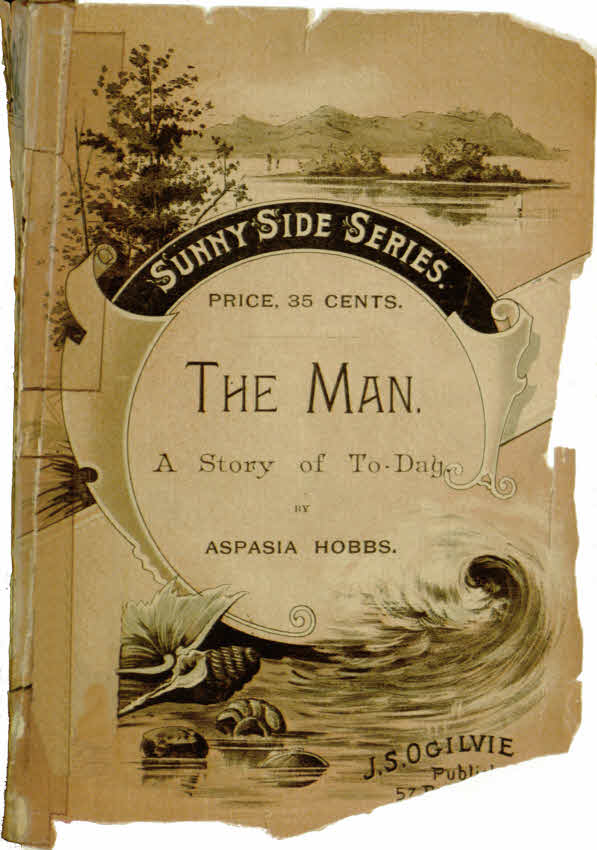

Van Houten’s Cocoa.

Mr. Pickwick.

“Chops and tomato sauce are excellent, my dear Mrs. Bardell, but let the liquid be Van Houten’s Cocoa.

“It is a glorious restorative after a fatiguing journey.”

“Best & Goes Farthest.”

The Standard Cocoa of the World.

A Substitute for Tea & Coffee.

Better for the Nerves and Stomach.

Cheaper and more Satisfying.

At all Grocers. Ask for VAN HOUTEN’S.

Perfectly Pure—“Once tried, used always.”

☞A comparison will quickly prove the great superiority of Van Houten’s Cocoa. Take no substitute. Sold in 1/8, 1/4, 1/2 and 1 lb. Cans. ☞If not obtainable, enclose 25c. in stamps or postal note to either Van Houten & Zoon, 106 Reade Street, New York, or 45 Wabash Ave., Chicago, and a can containing enough for 35 to 40 cups will be mailed if you mention this publication. Prepared only by the inventors, Van Houten & Zoon, Weesp, Holland.

A STORY OF TO-DAY,

With Facts, Fancies and Faults Peculiarly its Own; Containing Certain Truths Heretofore Unpublished Concerning Right Relation of the Sexes, etc., etc.

By Aspasia Hobbs.

Copyright, 1891, by J. S. Ogilvie.

THE SUNNYSIDE SERIES, No. 47. Issued Monthly. December, 1891. Extra. $3.00 per year. Entered at New York Post-Office as second-class matter.

LETTER NO. 1.

Buffalo, N. Y., July 1, 1891.

To Martha Heath,

Friend:—You said that someone would surely print it, and I write you this to say that after four publishers had most politely rejected the manuscript, the fifth has written me saying the story does not amount to much; in fact, that I have no literary style, but as the book is so out of the general run they concluded to accept it. They sent me a check for $300.00 which they say is a bonus, and after the first 5,000 copies are sold they propose to pay me a royalty. So you see even if I have lost my place at Hustler’s, I am not destitute, so I will not accept your offer of a loan. You and Grimes (dear old Grimes) are the only persons in all this great city who have stood by me in my trouble. If you had presented me with a box of candy I would thank you, but for all the kindness I have received, prompted by your outspoken and generous nature, I offer not a single word. Words, in times like these, to such as you, are of small avail, my heart speaks. You say you dislike awfully to see those last five chapters in print, and so will I, my dear. Little did we think when I began this book that the story would have such an ending; but, Martha, I am not writing a pretty novel, but simple truth just as the facts occurred. I offer no excuse nor apology, but will simply give you this from Charles Kingsley’s “Alton Locke:”

Scene: A street corner in London, on one hand a gin palace, opposite a pawn shop—those two monsters who feed on the vitals of the poor—all about is abject wretchedness.

Locke stops, sighs and says, “Oh, this is so very unpoetic.” Sandy Mackaye replies, “What, man, no poetry here! Why, what is poetry but chapters lifted from the drama of life, and what is the drama if not the battle between man and circumstance, and shall not man eventually conquer? I will show you too in many a garret where no eye but that[4] of the good God enters, the patience, the fortitude, the self-sacrifice and the love stronger than death, all flourishing while oppression and stupid ignorance are clawing at the door!”

But right will conquer, dearest, and the goodness that has never been weighed in the balances, nor tried in the fire, how do you know it is goodness at all? It may only be namby-pamby—wishy-washy—goody-goody, who knows? We are all in God’s hand, sister, and the bad is the stuff sent, on which to try our steel.

Yours ever,

Aspasia.

LETTER NO. 2.

July 3, 1891.

To Pygmalion Woodbur, Esq., Attorney-at-Law.

Sir:—I have received your letter warning me that if I use your name in a certain book of local history (said book entitled The Man) that you will cause my arrest for malicious libel, and also sue me for damages. To this I can only say that the book is now in the hands of the electrotypers, and I am not inclined to change a line in it, on your suggestion, even if I could. Please believe me, when I say, that I bear you no ill-will and have no desire to injure you or place you in a wrong light before the public, what I have written being but truth penned without exaggeration or coloring. I make no apology or excuse. What I have written I have written.

Yours, etc.,

Aspasia Hobbs.

LETTER NO. 3.

Buffalo, N. Y., July 3, 1891.

To John Bilkson, of Hustler & Co.,

Sir:—Your registered letter of June 30th, received, wherein you state that you have no further use for my services, and that whereas you generally give an employee[5] a letter of recommendation when you discharge them, yet in my case you cannot do so.

Although I have made no request for such recommendation, I regret your conscience will not allow you to supply it.

You remember the scene of five years ago in your office? No one knows a word of this, and never will, unless you tell it (which I hardly think you care to do). You swore then you would get even with me—is your vengeance now satisfied?

I have no malice toward you—I cannot afford to have against anyone—although I must say that your action in deducting from my wages the price of one set of false teeth purchased from Dr. Poole is not exactly right. You know, Mr. Bilkson, you lost those teeth purely through accident and no one regretted the occurrence more than I. With best wishes for the continued prosperity of Hustler & Co., I remain,

Yours, as ever,

Aspasia Hobbs.

THE MAN.

What I have to write is of such great value, the circumstances so peculiar, the record so strange, and the truths so startling, that it is but proper I should explain who and what I am, in order that any person, so disposed, may fully verify for himself the things I am about to relate.

Just at that most quiet hour of all the twenty-four, in the city, on a summer’s morning, when the darkness is stubbornly giving way to daylight, there came a violent ring at Mr. Hobbs’ door-bell, followed up with what seemed to be quite an unnecessary knocking.

Mr. Hobbs was interested in an elevator, and when he heard that ring he was sure the elevator had burned—in fact, he had a presentiment that such would be the case; besides this, Mr. Hobbs always carried a goodly assortment of fears ready to use at any moment.

“There, didn’t I tell you!” he excitedly exclaimed to his wife, as he rushed down the stairs—he hadn’t told[8] his wife anything, just bottled up his fears in his own bosom and let them ferment, but that made no difference—“Didn’t I tell you!” and he hastily unlocked and opened the door. No one there!

He looked up the street and down the street. Nothing but a clothes-basket, covered over with a threadbare shawl, which evidently a long time ago had been a costly one. Mr. Hobbs expected a messenger with bad news and Mr. Hobbs was disappointed, in fact was mad; and he snatched that shawl from the basket, staggered against the door, and a voice, like unto that of a young and lusty bull, went up the stairway where Mrs. Hobbs stood peering over the banisters:

“Maria, for God’s sake come quick! There’s something awful happened! Quick, will you!”

Mrs. Hobbs was not very brave, but curiosity often reinforces courage; so the good lady came down the stairs two steps at a time, and stood by the side of her liege, who had got his breath by this time and stood peering over the basket.

And there they stood together, all in white, with bare feet, on the front porch, and nearly broad daylight.

In the basket, all wrapped up in dainty flannel, smiling, cooing and kicking up its heels, lay a baby—well, perhaps two months old, and on a card written with pencil were these words:

“God knows.”

Mr. and Mrs. Hobbs had no children, and they each looked upon this as a gift from providence—basket and all. They cared for the waif as their own child, and if their reward does not come in this life, I am sure it will in another.

“Her name shall be Aspasia Hobbs, for I always said my first girl (Mr. and Mrs. Hobbs had been married five years, and had no children, but the babies were already named; which, I am told, is the usual custom) should be named Aspasia, after your mother, dear,” said Mrs. Hobbs.

And Aspasia Hobbs it was, and is yet: and I am Aspasia Hobbs: and Mr. and Mrs. Hobbs are the only parents I have ever known.

I am now an old maid, aged thirty-seven (I must tell the truth). I am homely and angular, and can pass along the street without a man turning to look at me. From five years’ constant pounding on a caligraph my hands have grown large and my knuckles and the ends of my fingers are like knobs. I can walk twenty miles a day, or ride a wheel fifty.

The bishop of Western New York, in a sermon preached recently, said riding bicycles is “unladylike” (and so is good health for that matter)—but if the good bishop would lay aside prejudice and robe and mount a safety, he could still show men the right way as well as now—possibly better, who knows?

But, in the language of Spartacus, “I was not always thus.” Thank Heaven, I am strong and well! They used to say, “She is such a delicate, sensitive child, we can not keep her without we take very, v-e-r-y good care of her.” Some fool has said that hundreds of people die every year because they have such “very good care.”

My father was a member of the firm of Hobbs, Nobbs & Porcine, was a Board of Trade man, and, therefore, had no time to give to his children; but he was a good provider, as the old ladies say, and used to remind us of it quite often. “Don’t I get you everything you need?” he once roared at my mother, when she hinted that an evening home once in a while would not be out of place. “Here you have an up-stairs girl, a cook, a laundress, a coachman, a gardener, a tutor for Aspasia, and don’t I pay Doctor Bolus just five hundred dollars a year to call here every week and examine you all so as to keep you healthy? Great Scott, the ingratitude of woman! they are getting worse and worse every day!”

My father was a good man—that is he was not bad, so he must have been good. He never used tobacco, and I never heard him swear but once, and that was when Professor Connors brought in a bill reading:

“Debtor, to calisthenics for wife and daughter, $50.”

“I’ll pay it,” said my father grimly, “but I will deduct it from Bolus’ check, for you say it’s for the health and[11] therefore it belongs to Bolus’ department and he should have furnished the goods.”

We lived on Delaware avenue, in one of the finest houses, which my father bought and had furnished throughout before my mother or any one of us were allowed to enter. He was a good man, and wanted to astonish—that is to say, surprise us. So one Saturday night, at dinner, he said,

“On Monday, my dears, we will leave this old Michigan street for a house on the ‘Avenue.’ I have given up our pew in Grace Church, and to-morrow, and hereafter, Rev. Fred. C. Inglehart and Delaware avenue are plenty good enough for us.”

Our family have the finest monument in Forest Lawn, and father assured us that if Methusalah was now a boy this monument would be new when his great grandchildren died of old age. He waxed enthusiastic, and added, as he lapsed into reverie,

“It’s a regular James Dandy, and knocks out Rodgers and Jowette in one round.”

I am a graduate of Dr. Chesterfield’s academy, and also of the high-school. I have studied music with Mr. McNerney and Senor Nuno, elocution with Steele Mackaye; and father once offered to wager Mr. Porcine that “Aspasia could do up any girl on the avenue or Franklin street at the piano.”

I was a rich (alleged) man’s daughter, and as I had a[12] managing mamma and went in society I had the usual love (how that word is abused!) experiences. I am not writing an autobiography, but merely telling what is absolutely necessary for you to know of me; otherwise, I would relate some insipid mush about flirtations with several gilded youths, who waltzed delightfully and made love abominably—just as if a man could make love! But suffice it to say, I never, in those old days, met a man I could not part with and feel relieved when he had taken his “darby” and slender cane and hied him down the steps. Mamma said I was heartless and didn’t know a good chance when I saw it.

One little affair of the pocket-book—that is, I mean of the heart—might be mentioned. A certain attorney, Pygmalion Woodbur by name—old Buffalonians know him well—paid his respects to me in an uneasy and stilted fashion. He was ten years my senior, had a monster yellow moustache generally colored black, which he combed down over the cavern in his face. He dressed in the latest, and was looked upon as a great catch. How these old bachelor men-about-town are lionized by a certain set of women!

He called several times, invited himself to dinner, took mamma riding and threw out side glances—grimaces—in my direction. One fine evening I sat reading in the parlor, alone, and in walked Mr. Woodbur and began about thusly:

“Aspasia—I may call you by your first name, now can’t I?—and you must call me Pyggie, for short. I have just spoken to your father and he says it’s all right,” etcetera, etcetera, etcetera.

He slid off from the sofa on his knees, and seized my left hand and kissed it violently.

Fair lady, have you ever been kissed with a rush, by a man with a large yellow moustache colored black? Well it’s just like being jabbed with a paint brush!

Now, after his poorly memorized speech had been delivered, and I had jerked my hand away, there was a pause. I tried to laugh and I tried to cry; then I tried to faint, and was too mad to do either; so I just inwardly raged and then came the explosion—

“No! no! no! a thousand times no! Stick to you, Woodbur! Never! I hate you—get out of my sight, quick!”

Just then in came papa and mamma, who it seems were taking a turn about at the keyhole.

“Why! why what’s the matter with my little girl,” and I fell sobbing in my mother’s arms.

“You must excuse her, Mr. Woodbur,” said the good lady. “Since her sunstroke, she has these spells quite often. You will excuse her, I know.”

“Why, when was the gal struck! You never told me nothing about it,” broke in my father.

“Now Hobbs, don’t be a fool,” said my mother under her breath.

Father started to answer. Woodbur saw his opportunity, and escaped under cover of the smoke, and forgot to come back for his umbrella, which I now have tied up with a white ribbon and put away with mint and lavender in memory of days gone by—and the best that I can say of the days that have gone by is that they have gone by.

As time wore, life seemed to grow dull and heavy, my cheeks grew pale, and in summer I sat on the piazza, often from breakfast until dinner-time, with a white crepe shawl thrown about my shoulders, listlessly watching the passers-by. Mother said, “Poor girl, I wish she would get mad just once as she used to. She is so good and submissive.” Doctor Bolus said I needed cod liver oil with strong doses of quinine, and once a week Glauber salts taken in molasses and sulphur; but still in spite of all medicine could do for me, I grew weaker and weaker. I fed on Mrs. Hemans and Tupper, and finally they carried me daily out to the big carriage, and the coachman was instructed to drive very slowly, and we went out through the Park, out to Forest Lawn and looked at our family monument, which gleamed in the beautiful sunshine.

Mother generally rode with me, and one morning she left me waiting in the carriage while she went over near[15] our “lot,” so she could more closely inspect the monument. While waiting the coachman turned to me and said:

“Missis, yer father have bust, yer mother don’t know it; but you are no fool, missis, and I thought you should know it, to kinder prepare like. They have been around inventizering the horses and carriages and are going to sell them next week—see? And my wife said you are the only one who has sense, and I should break the news to you easy like—see?”

I heard him rattling on, but did not seem to understand what he said; but I felt my heart beating fast and the blood coming to my cheeks. The old dead submissiveness was gone, and I said:

“John, shut up, and repeat to me what you said first.”

“Nothin’,” said John, “only that your father have bust and run off to Canada, and C. J. Hummer and the rest is goin’ to bounce you out next week.”

I saw his grieved tone, or felt it rather, and said:

“John, I did not mean to speak cross to you.”

“Never mind, missis, I have no favors to ax, and you couldn’t grant eny even if I did—for your father have bust, dwye see?”

Mother was coming from the monument, and greatly vexed, I saw.

“Why, Smythe has not put any foundation under it[16] at all scarcely,” she said, as she stepped into the carriage. “The weight on top is gradually crushing the bottom, and I believe it is full six inches toppled over to the west.”

“It is probably going west to grow up with the country,” I said.

Think of such a remark from a dying invalid!

My mother turned in astonishment to see if it was really her daughter.

“John,” said I, “drive home—go fast—let them out, will you—go home quick. Mrs. Hobbs is not well.”

I felt an awful propensity to joke, and a wild exultation and pleasure came over me that I had not known since we used to climb the hills at our summer-house at Strykersville. John cracked the whip and saluted all the other coachmen as we passed. He whistled, and so did I. For the first time in five years I felt free; and John had lost the fear that he would not be impressive, and he too was free. My mother sat bolt upright in a rage.

“You are both drunk,” she said. “John, sit straight on that box. Don’t carry the whip over your shoulder, and don’t cross your legs or I will discharge you Saturday night!”

John turned round—smiled—looked at me and winked.

As the carriage stopped in the portière the big gardener came down, and placing one arm under and the other about me, was just going to lift the invalid out as usual.

“Go away,” I fairly screamed. “Let me walk, will you! Carry mother in quick,” for sure enough, she was the one who had to be carried. Her rigid dignity had disappeared, and she had dropped back listless and disheveled, moaning:

“Oh, John is drunk and Aspasia crazy! Look at her! she is so sick she can’t walk, and yet see her run up those steps! What shall I do, what shall I do! And the monument that they warranted in writing to last for ever or no pay is tumbling down. I must have it fixed, even if it costs ten thousand dollars; for the name of Hobbs must not grow dim.” “Dear he” (she always spoke of her husband as simply “he” or “him”) “has so often said, ‘You married Hobbs for better or worse’—says he to me—‘and your name will be carved on the finest monument in Forest Lawn.’“

Reader bold—lacking in knowledge and therefore in[18] faith, limiting possibility to your own tiny experience, quick to deny—you doubt that I went away an invalid and returned in an hour cured. Let me whisper in your ear that it was all in accordance with natural law, and not at all strange or miraculous, excepting in the sense that all nature is miraculous (let us not quarrel over definitions). That which cured me was a good dose of Animating Purpose.

Men retire from business and die in a year from lack of animating purpose. Women are protected, hedged about and propped up, cared for, and die for the lack of this essential.

“Faith Cure,” “Christian Science” and any other strong desire filled with hope and a determination to be and to do, supply animating purpose of a good kind, although sometimes, possibly, alloyed with error: but any good idea which makes us forget self and sends the blood coursing through our veins, is healing in its nature.

When the stays that held me were cut, and I knew I must live and work and be useful, the old sickly self was thrust far behind by Animating Purpose; not the finest quality of animating purpose, I will admit, but a fairly good serviceable article, and certainly a thousand times better than none.

You must not think that my mother was naturally weak—not so. Of a fine delicate organization, she married when nineteen and had given herself unreservedly[19] to her husband in mind and body (for have not husbands “rights?”) never doubting but what it was her wifely duty to do so. She even gave up her own church and joined his—adopted his opinions—quoted his sayings and repeated his jokes. “Well, he says so and that is an end to it.” In the house of Hobbs, Hobbs was the court of last appeal.

In some marriages women say “I will” audibly, with mental reservation of “when circumstances permit.” Such women have been instructed in diplomacy. They have been told to meet their husbands at the door with a smile and clean collar, to make home pleasant, to smooth down the rough places—in short, to manage the man and never let him discover it, which is the finest of the finest arts. They can examine his pockets at such convenient times when he will not know it, count his money, take what they need—which is better than harassing a man and whining for a dollar—read his note-book, and thus in a thousand little ways keep such close track of him that with proper skill there would be positively no excuse for rubbing him the wrong way of the fur.

But not so with my mother. She said to Mr. Hobbs on their wedding night,

“I am yours—wholly yours. In your presence I will think aloud, there shall be no concealment. To you I give my soul and body!”

Mr. Hobbs took the latter, and in a hoarse whisper said:

“I have an income of six thousand dollars a year, and you shall never regret you married Hobbs, of Hobbs, Nobbs & Porcine. I will shield you from every unpleasant thing; you shall never know care or trouble; never a day’s work shall you do; nothing but just be happy and look pretty the livelong day; and anything you want at Barnes & Bancroft’s, Peter Paul’s, Dickinson’s or Fulton Market, why get it and have it charged to Hobbs, for I am rated in ‘Dun’ ‘E. 2,’ and next year it will be ‘2 plus.’”

Such total unselfishness touched the virgin heart of this nineteen-year’s-old woman—that is to say, child. She lived in a Hobbs’ atmosphere. The two lives did not grow into one, she became Mrs. Hobbs not only in name but in fact. Now any thinking person will admit that this was better than for her to have endeavored to retain her individuality, for if she had done this and still was honest and frank, there would have been strife. She would always have thought of her girlhood as the ante bellum times, for Mr. Hobbs had ideas, or believed he had, and nothing gave him such delicious joy as to rub these ideas into one, especially if they squirmed and protested.

I have seen precocious children that astonished or made jealous as the case might be. How they did sing,[21] play the banjo, or speak! One such boy I remember—we were all sure he would grow to be an orator who would shake the nation. I watched him, and saw him to-day presiding at the second chair in Chadduck’s tonsorial palace, and noted the Ciceronian wave of his hand as he shouted the legend, “Next gentleman—shave.”

Walking across a prairie in Iowa with a friend, we suddenly found ourselves going through a miniature grove, where the highest trees did not reach my shoulders. I examined the leaves and found the trees to be black-oak of the most perfect type.

“What beautiful young trees! How they will grow and grow and put out their roots in every direction, and search the very bowels of the earth for the food and sustenance they need! How they will toss their branches in defiance to the storm, and be a refuge and defence for the wearied traveler! How——”

“Stop that gush, will you please!” said my companion. “These are only scrub-oaks and will not be any larger if they live a hundred years.”

Possibly this grove explains why the average man of sixty is no wiser and no better than the average man of forty—it is Arrested Development.

My good mother is only a fine type of Arrested Development.

With my woman’s intuition I knew all just from the hint John gave. My father a week before had gone to Montreal, saying he would be back Wednesday. It was now Friday and he had not returned. I remember the two men who had come to “take an inventory for the ‘Tax Office,’” one said, and he winked at the other. How they walked through the house with their hats on and joked each other as they tried the piano! I saw it all! My father had lost money and had given a chattel mortgage on the furniture, having first raised all the money he could on the real estate.

I asked my mother if she remembered giving the mortgage, and she looked at me, grieved and surprised, saying:

“Why, of course not, dear. I always signed the papers he brought me. Do you think it a woman’s place to ask questions about business?”

Well, if I were writing my own history, I would tell you how the two men from the “Tax Office” came back with Robert McCann the auctioneer; how they hung a big red flag over the sidewalk and took up[23] the carpets so that when they walked across the bare floor of the big parlors the echo of the footsteps rang through the whole house; how greasy men with hook noses came and examined the furniture; of how one such insisted on seeing my mother on very private business, when he asked, “If dot bainting was a real Millais or only a schnide; and if it was a schnide, to gif a zerdificate dat it vas a Millais and I will bid it off at a hundred, so hellup me gracious!”; of how kind neighbors came and bought in all the dishes and silverware and gave them back to us; of how a certain widowed gentleman offered to bid in the piano if I would accept a position as governess for his daughter and live at his house.

Well, the furniture went and so did we. The Fitch ambulance came and took mother down to our new quarters, which I had rented on South Division street, near Cedar, and right pretty did the little house look too. Mrs. Grimes, the laundress, came with us—in fact, came in spite of us.

“I have no money to pay you, and you cannot come. That is all there is about it,” I protested.

“Well, I don’t want no money,” said this gray-haired old woman. “I have ’leven hundred dollars in the Erie County, and it is all yours if you want it. Haven’t I worked for the Hobbses three weeks lacking two days before you was left on the steps? I was the only girl they[24] had then, and I am the only girl you got now. I have sent my hair trunk down to South Division street, and I’m going myself on the next load with Bill Smith, who drives the van for Charlie Miller. I knowed Bill before I did you, and Bill says he will stand by Aspasia Hobbs too, he does.”

What could I do but kiss the grizzled kindly face of this old “girl” on both cheeks and let her come?

It was a full month before we got track of my father. I went to Montreal and brought back an old man, with tottering mind, crushed in spirit. He had fixed his heart on things of earth—he became a part of them, they of him—and when they went down there was only one result. He lingered along for three months, constantly reproaching himself; seeing also reproach in the face of every passer-by, imagining upbraidings in each look of those who sought to comfort and care for him, and the light of his life went out in darkness.

“Judge not that ye be not judged.”

My mother received a little money from the life insurance companies. Father patronized only assessment companies, as they are cheap. He prided himself on his financial ability, always saying he could invest money as well as any rascally insurance president and that there was “nothing like having your money where you can put your claw on it in case you get a straight tip.”

Idle I could not be, and I resolved to get a situation.

“Verily, I will teach school, for the young must be educated,” I said, “or the world cannot be tamed. I must, I will mould growing character.” In fact, I felt a call; so I called on Mr. Straight, the superintendent of education, never doubting but that he would at once give me an opportunity to show my ability. I displayed my Dr. Chesterfield and the high-school diplomas, and various certificates from long-haired and eccentric foreigners, (not forgetting Prof. Franklin of Col. Webber’s and Judge Lewis’s testimonials, who imparts dramatic instruction for one dollar an impart) as to my ability in music, dancing, French, German, and deportment.

The superintendent counted the certificates and diplomas as he piled them up on his desk, and asked me if I had any “pull.” Then he asked me why I did not get married, and said he had been looking for me, “for whenever a man busts his daughters always come here for a job.” He took my name in a big book, and as he waved me out remarked that “there are only seven hundred applicants ahead of you. I’m afraid you are not in it. You had better catch on to some young fellow, my dear, before the crow’s feet get too pronounced——ta, ta.”[1]

I stood outside the door confused, defeated, angry. I thought of a thousand things I should have said to that grinning insinuating superintendent, and here I had not said a word. I was out in the hall, the door was shut. Slowly my wrath took form in action, and I walked off[27] with a much more emphatic tread than was becoming in a young woman. I slammed my parasol against the banisters at every stride as I went down the city hall steps. I had a plan. Straight to the News office I went, intending to insert an advertisement and thus secure exactly the position I desired. I bought a paper to see how other people advertised, and my eyes fell on the following:

Wanted: As correspondent, book-keeper and stenographer, a young woman who can translate German, French, and Italian, who is not afraid to work, and can look after the business in proprietor’s absence. Wages, $4.75 per week.

Apply to Hustler & Co.,

Manufacturers of Glue,

Genesee Street.

I took the paper and entered a herdic, telling the driver to hurry as I wanted to go to Hustler & Co.’s.

Arriving there, I walked in, banged the door, and demanded to see Hustler, omitting all title and prefix. Straight had brow-beaten and insulted me an hour before—let Hustler try if he dare. I wanted a position, not advice, and would brook no parley or nonsense.

“Are you Hustler?” I asked of a little meek bald-headed man, with a ginger-colored fringe of hair like a lambrequin around his occiput. He plead guilty. “And did you,” I continued hurriedly, but in a determined manner, “and did you insert this advertisement?” and I spread out the paper before him.

He hesitated.

“Did you, or did you not?”

Here I moved back three paces and gazed at him as though I had him on cross-examination. He admitted that he had inserted the advertisement, had not yet found a young woman who could fill all of the conditions, and that I could have the place.

“To-morrow, when the whistle blows for seven o’clock,” said he.

“To-morrow, when the whistle blows for seven o’clock,” said I.

At last I was no longer a dependent! From this time on I would not only earn my own living, but I would do for others. I was no longer a pensioner.

“He who receives a pension gives for it his manhood,” said Plato. A pension makes a man a mendicant. When the world is peopled by God’s people, every man will work according to his ability, and will be paid for his services, so there will neither be pensioners nor bumptious bestowers.

My work at Hustler & Co.’s was not difficult, when I got over the scare and the belief that it was awfully complex. In short, the lion was chained, as it always is when we get up close and inspect the animal; or perhaps, it is only a stuffed lion that has been terrifying us. Possibly some evilly disposed person, seeing our fear, has taken pains to wipe the dust off the fiery glass eyes, to rough up the tawny mane, and set the tail at that terrific angle—but who is afraid of a lion on wheels? When I became composed and took a common sense view of the work, the difficulties took wing, and at the end of the first week, Mr. Hustler gave me the assurance “that I[30] was no slouch,” which is the highest compliment that Rustler Hustler, of the firm of Hustler & Co., glue makers, was ever known to pay to any living soul.

One of the girls in the office told me that the former stenographer lost her place by taking dictation for Mr. Bilkson, the junior partner, at close range; which being interpreted, meant that when Mr. Bilkson dictated his letters to the young lady, he had her sit on his knee. Mrs. Bilkson is a large, determined woman with a jealous nature and red parasol. As she appeared in the private office one day without first sending in her card, the close range plan was discovered. Soon after that little Miss Bustle was found to be incompetent, and the cashier gave her her time. Bilkson still remains.

When the junior dictates letters to me, it is through the little sliding window that connects my room with the general office. This was at my suggestion after a few days’ acquaintanceship with the gentleman. I fear I also incurred his enmity when I told him I was hired to do the work, not to entertain the firm.

Saturdays we have half a day off—that is, we work until 1:30 and are docked half a day.

Every one who knows me, knows I am a great bicycler—in fact, working closely, if it were not for the outdoor exercise I get, I could never stand the strain, but would be a candidate for nervous prostration (technical name Americanitis). Some years ago I had an awful[31] bad spell. Dr. Bolus was sent for and prescribed quinine and iron with a trip to Bermuda and rest for a year. My old friend, Martha Heath, came in soon after, and I asked her to go to Stoddard’s drugstore for the quinine.

“I won’t,” said Martha Heath. “Bounce Bolus and buy a bicycle!”

I followed her advice, and have blessed Martha Heath ever since.

It was my custom on Saturdays after I had eaten my lunch at the factory, to take my wheel and go on a long ride, sometimes in the summer as far as Niagara Falls, getting back late in the evening. These long quiet rides I anticipated with much pleasure, for to get away from the strife of men out into the quiet country, seemed to give me new life. The winter gave me little opportunity for these trips, so I looked forward longingly to the coming of spring.

The month of April, 1891, it will be remembered was remarkable, in that there was not a single fall of rain from the 10th to the 30th. The roads were dry and dusty as in summer. Saturday afternoon, April 30th, when I rode out Clinton street in the delightful sunshine which seemed to bear healing on its wings, women were working in the gardens, cleaning up the rubbish; children playing on the road; a faint smell of bonfire from burning rubbish, people starting in in the spring to keep the yards clean; men plowing in the fields; and[32] how the frogs did croak! Joy and gladness on every hand. Out through Gardenville, past Ebenezer, five o’clock found me at Hurdville. I was so very busy drinking in the glorious scene that I had ridden slower than I intended, for I had made calculations to be at Aurora before this time, and well on the way homeward.

“Well,” said I, “Aspasia Hobbs, you had better hurry up or night will catch you. Besides, the wind has come up strong from the southwest, and away off over the Colden hills is a little black cloud—what a joke if you should get wet?”

There is a lane running across from Hurdville to the Buffalo plank road, so I decided to cut my trip short and strike across at once. I looked at my watch and it was just 5:15 when I entered the lane, which was grass-grown and not at all adapted for bicycling. As I pushed on, the road grew worse, so I got off and pushed the wheel ahead of me. Rather hard work it proved, as I wore a long woolen dress, which I had to hold up in walking.

Then I tried riding again. A great yellow ominous brightness was in the west, and soon I noticed it was growing dark, and that the little cloud had grown until it seemed to cover the whole western sky. A few big rain drops fell as I looked again at my watch, which said six o’clock. I kept thinking I must come to the plank road every minute, and strained my eyes for the[33] telegraph poles which I knew marked the highway. But no, I could not see them. “Surely this lane must cross the main road or I am turned around and am following a road running parallel with the other,” I concluded.

Still I trudged on, now riding, then walking. It began to rain now in right good earnest. I felt the mud sticking to my shoes and my clothes growing heavy. My arms grew tired pushing the wheel before me as I walked. The spokes had become a solid mass of mud. I tried to mount the wheel. It swerved and I lay in the ditch. I then realized that to try to push the bicycle further or to ride would be folly; so I pulled the machine into the bushes, and looked around me on every side. Not even a lightning glare to relieve the gloom and brighten the landscape. The rain still fell in torrents. I covered my face with my hands. I thought of my mother waiting in the bright light of our little dining-room, the supper on the table. I tried to imagine this howling wind and blackness of the night was a dream; but no, I was alone—alone, lost.

It was the worst night I ever saw, and I hope I may never see another one like it. How the winds did roar through the branches and the wild crash now and then of a falling tree was most appalling. The darkness was intense. The cold rain came in beating gusts, and I felt it was gradually turning to sleet and snow.

Think of it, I, a city-bred woman, alone on an out-of-the-way country road, dense woods on either side, mud and slush ankle deep, wandering I knew not where!

My clothes weighed a hundred pounds. They clung to my tired form and I seemed ready to fall with fatigue, when I saw, not far ahead of me, the glimmer of a light which seemed to come from a small log house a quarter of a mile back from the road.

Straight toward the welcoming glimmering light, through bramble, bush and stumps, I stumbled my way, now and then sinking near knee deep in some hole where a tree had been uprooted. I think I rather pounded on the door than rapped, and so fearful was I that I would not meet with a welcome reception, that I began scarcely before the door was opened explaining in a loud and[35] excited voice (for I am but a woman after all), begging that I might be warmed and sheltered only until daylight, when I could make my way back, promising pay in a sight draft on Hustler & Co., for in my coming away I had left my purse in my office dress. I only remember that what I took for an old man opened the door, led me in, showing not the slightest look of curiosity or surprise, but seeming rather to be expecting me. He stopped my excited talking by saying, in the mildest, sweetest baritone I ever heard,

“Yes, I know. It is turning to snow. You lost your way and are wet and cold. Look at this cheerful fireplace and this pile of pine wood. My wife is here; but no, I have no woman’s clothes either. You had better take off your dress and let it dry over the chair. Then if you stand before the fire your other raiment will soon dry on you, which is as good as changing; and in the meantime, I will get you something to eat.”

That night seems now as if it belonged to a former existence, so soft and hazy when viewed across memory’s landscape. I only know that as soon as the man stopped my hurried explanations, the sense of fear vanished, and I felt as secure as when a child I prattled about my mother’s rocking-chair as she watched me with loving eyes. I said not a word, so great was the peace that had come over me. After a plain supper, of which I partook heartily, I remember climbing a ladder up into[36] the garret of this log house, and stooping so as not to strike my head against the rafters; also The Man’s tucking me in bed as though I were a child, putting an extra blanket over me while saying softly to himself as if he were speaking to a third person,

“She must be kept warm. Nature’s balm will heal, sleep is the great restorer, to-morrow she will feel all the better for this little experience. So is the seeming bad turned into good.”

He passed his hand gently over my eyes, took up the candle and I heard him move down the ladder and—sweet childlike sleep held me fast.

The morning sun came creeping through the cracks of the garret as I slowly awoke to consciousness and began rubbing my eyes, trying to make out where I was and how I came there. Slowly it dawned upon me, the awful work of trying to push that wheel through the mud; the descending darkness; the increasing storm; of how I left the bicycle by the road-side and the sickening sense that came over me as I felt that I had lost my way and must find shelter or perish; of how my heavy woolen dress, soaked with water, tangled my tired legs as I struggled forward; of the glimmering light, and how I feared that though I had at last found a house they might mistake me for an outcast and have no pity on me; of the sweet peace I experienced when the old man spoke to me; of following his suggestion that I should remove my dress; of how I stood clad only in my under-clothing before the fire, and of how he put me to bed, and I was all unabashed and unashamed. I thought of all this and more, and was just getting ready to be thoroughly frightened when my reverie was broken into by hearing a step come lightly up the ladder, and the[38] beautiful face of The Man framed in its becoming snowy white hair appeared.

“Yes, she is awake,” he said, again seemingly talking to a third person. “She will be a little sore of course after the exertion, but refreshed and all the stronger for the hard work. Paradoxical—effort put forth causes power to accumulate in the body, which is only a storage battery after all. By giving out power we gain it, by losing life we save it. How simple yet how wonderful are the works of God!” Then speaking to me: “I will bring you warm water for a bath. It will take the stiffness out of your limbs. Breakfast will be ready when you are.”

I bathed, dressed without the aid of a glass, and was surprised to feel how strong and well I felt. Down I went cautiously on the ladder, and we ate breakfast, neither speaking a word. It seemed as if (glib as I generally am—“A regular gusher,” Martha Heath says) to break in on the silence would be sacrilege. Silence is music at rest.

Out of every fifty men who pass along the street, only one thinks; the forty-nine have feelings but no thoughts. We have no time here to treat of the forty-nine; let us leave them out of the question and deal only with the one, the men of character, so-called, men who have opinions and hold them. In this class we cannot admit the girl-men or boy-men or those who are called men simply[39] because they are not women, or the vicious or even those of doubtful morality. Let us take only the best and not even consider the “unco-gude.” Now having banished the unthinking, the immoral and the doubtful, tell me, reader, have you ever seen a man? Have you? Not a caricature or imitation of one, full of a wish to be manly, and therefore anxious about the result? not a being full of whim and prejudice, receiving the opinions from the past and referring to numbers as proof; who prides himself on his self-reliance and his absence of pride, and yet who can be won by agreeing with him and through diplomacy? not one who endeavors to prove to you the correctness of his views by argument in the endeavor to win you over to his side, in order that that side may be strengthened? not one in whose mouth there is continually a large capital I, or who has a bad case of egomania and studiously avoids all mention of himself?

But what I mean is a man every whit whole, mens sana in corpora sano, who is afraid of no man and of whom no man is afraid, to whom the word ‘fear’ is unknown. Prize fighters sometimes boast that they are without fear, but there is one thing they are afraid of, and that is fear. Fear is the great disturber. It causes all physical ills (Yes, I know what I say.) and it robs us of our heavenly birthright. What is the cause of fear? Sin, and if your education had been begun[40] at the right time and in the right way, you might now be without sin—that is, without fear. Begin the right education now, and in time you will come into possession of your heritage; for you are an immortal spirit, dwelling in this body which to-morrow you may slip off; and all the right education you have acquired will still be yours, for as in matter there is nothing lost, so in spirit nothing is destroyed.

When you stand in the presence of a man you will know it by the holy calm that comes stealing over you. His presence will put you at your ease—with no effort to please and yet without indifference. Both can remain silent without there being an awkward pause or any embarrassment. The atmosphere he will bring will clothe you as with a garment, and though your sins be as scarlet you will make no effort to dissemble, to excuse, to explain, or to apologize. You will find this man is no longer young, for youth is restless and ambitious, and although he fears not death, nor scarcely thinks of it, yet lives as though this body was immortal.

I lived under the same roof with The Man one day in each week for two months, and words utterly fail me when I endeavor to describe him, for how can I describe to you the Ideal?

At first I thought him an old man, for his luxuriant hair and full wavy beard were snowy white; but the face, tanned by exposure to the winds, was free from wrinkles[41] and had the bright anticipatory joyous look of youth; eyes, large, brown and lustrous, looking through and through one, but yet the glance was not piercing, for it spoke of love and sympathy and not of curiosity or aggression; form, strong and athletic; hands, calloused by work; yet this man, strong, brown, with throat bared to the breast, seemed to have the strength of an athlete yet the gentleness of a woman, the high look of wisdom, and with his whole demeanor the composure of Plato. God had breathed into his nostrils and he had become a living soul.

“The roads are very muddy, friend,” the man began, “you had better stay here until to-morrow and return on the morning train. This is the day of rest. What a beautiful word that is, ‘rest’! There is no feverish tossing and longing for the morning to him who has worked rightly, only sweet rest. The heart rests between beats. See how restful and calm the landscape is,” and we looked out over the dripping woodland where the drops sparkled like gems in the bright sunshine. “Nature rests, yet ever works; accomplishing, but is never in haste. Man only is busy. Nature is active, for rest is not idleness. As I sit here in the quietness, my body is taking in new force, my pulse beats regularly, calmly, surely. The circulation of the blood is doing its perfect work by throwing off the worthless particles and building up the tissue where needed. So rest is not rust. While we rest we are taking on board a new cargo of riches. My best thoughts have been whispered to me while sitting at rest, or idle, as men would say. I sit and wait, and all good things are mine, ‘for lo! mine own shall come to me.’”

Thus did The Man speak in a low but most beautiful voice, and the music of that voice lingers with me still and will as long as life shall last. I seemed to have lost my will in that of The Man. I neither decided I would stay or go, but I simply remained. I am not what is called religious—far from it—for I have been a stumbling-block for every pastor and revivalist at both Grace Church and Delaware avenue. Neither have I any special liking for metaphysics, but I hung like a drowning person to every word The Man said; and after all it was not what he said, although I felt the sublime truth of his words, but it was what there was back. I knew, down deep in my soul, that this man possessed a power and was in direct communication with a Something of which other men knew not.

I have traveled much, and studied mankind in every clime, for before my father’s failure we went abroad every year. I know well the sleek satisfied look of success which marks the prosperous merchant; I know the easy confidence of the man satisfied with his clothes; I have seen the serenity of the orator secure in his position through the plaudits of his hearers; I know the actor who has never heard a hiss; the look of beauty on the face of the philanthropist, who can minister to his own happiness by relieving from his bountiful store the sore needs of others; the lawyer, sure of his fee, or the husband who knows he is king of one loving heart and[44] therefore is able to defy the world;—but here was a man alone seemingly, without friends, in the wilderness, in a house devoid of ornament and almost destitute of furniture, whose raiment was of the coarsest; yet here in the face of this man I saw the look that told not of earthly success dependent on men or things, but of riches laid up “where moth and rust cannot corrupt, and where thieves do not break through and steal.”

We sat in silence for perhaps an hour and then The Man spoke.

“Friend, I have called you here. You know that spirit attracts spirit, and once we know how, we attract at will. This secret you shall know. I have somewhat to give to the world. You must come here each Saturday and stay here during the day of rest. I could have gone to you, but the city is full of distractions and the lower thought-currents there render you less sensitive to truth; so here in this grove, God’s temple, I will teach, that you may go forth as a laborer in the vineyard where the harvest shall be not yet, but will be reaped by those who come after. You are a stenographer. Bring pencils and paper, and each Sunday I will give you a little of the truth that you are to publish in a book and give out to dying men, for the world must be saved. Men never needed truth and teachers as much as now. I do not preach nor write, but I act through others, and[45] during the past hundred years I have told to men many things which they have given to the world.”

“A hundred years?” I asked, astonished; and it was the first feeling of surprise I had felt.

The Man smiled faintly and said:

“Yes; three hundred years have I lived in this body. I was born in 1591. Why do you wonder? Have you no faith in God? You see miracles on every hand, and yet you now are ready to doubt. The oyster mends its shell with pearls: some unthinking person twists off the claw of a cray-fish, and you watch another spring forth and grow to full size, and yet you doubt that a man can retain his strength indefinitely!

“We die through violation of law. This violation is through ignorance, or is wilful. If we do away with ignorance and are willing to obey, we can live as long as we wish. Men only die when they are not fit to live. As long as a person’s body is useful, God preserves it. The body is renewed completely every seven years. This you were taught in school. Why should not this renewal continue? An infant has cartilage, but very little bone. Gradually the cartilage ossifies, until in old age the bones are brittle. This is caused by the deposits of lime which are being continually taken into the system. There is constant waste and constant repair in the human body. You know this full well, and you know that at night and in moments of repose the repair exceeds[46] the waste. So where you were tired and ready to faint an hour ago, you are now strong.

“When I was thirty years of age, and my body at its strongest and best, I adopted a simple plan of keeping the excess lime and deteriorating substances out of my system; so you see my flesh is strong yet, soft, for the muscles should not be hard and tense, but pliable. My bones are not brittle, but cartilage is everywhere where needed to form cushions for the articulations. I have not known pain for a century, for nature does her perfect work and the dead tissue is constantly carried off and replaced with new. Pain generally comes from deposits left in the body when they should be carried off. Rheumatism, you know, is only a deposit in the linings of the muscles; but I never think of my body until the subject is brought to my attention, and do not like to talk of it, as the theme is not profitable; but later I will tell you when you are able to understand, how to have the body throw off those excess substances and renew itself without limit.”

Now lest some of my readers who are very young should imagine I was “in love” with this man let me say—not so! In the presence of The Man sex was lost. He was to me neither man nor woman, yet both; although he had that glorious faculty of joyous anticipation, which we see in children—so he was not only man and woman, but child. Yet in wisdom I felt him[47] to be a prophet, and I myself was but a child. For after all we are but grown up children, and the difference between some grown people is no greater than that found among children and some men.

With this man I was a child, and he seemed to regard me so, yet never talked down to me, and I have since discovered that sensible people do not talk baby talk to children, nor do they talk down to people who they imagine ignorant. Men who do this reverse the situation and become veritable ignorami themselves.

Old John Foster, the horse-trainer, used to break horses for my father, and one day old John said to me, “Young lady, when you breaks a colt, don’t get scared yerself and then the colt won’t. Hitch him up just like he was an old hoss, and he will think he is one and go right along and never know when he was broke.”

Some men always change the conversation when a woman enters, thinking the subject too weighty for her comprehension; and in ‘sassiety’ they still talk soft nonsense to women because they think women like it; and lots of women have adopted the same idea, and have accepted the same creed—that they do know nothing and always will, and that scientific subjects, like Plymouth Rock pants, are for men folks.

Not long ago, you remember, we had a preacher who gave a series of sermons to men only, and a friend of mine who attended tells me the reverend divine gave[48] those men more ‘pointers’ in depravity than they could have guessed alone in a dozen years.

But pardon this diversion and let me simply say, that to educate the heart and conscience, you must not separate men from women, nor make foolish distinctions between the ignorant and the cultured. We are all God’s children, and it is all God’s truth, and this is God’s world.

The Man told me this, and much more in that delightful day of rest, and he seemed to make no distinction between my childish ignorance and his own unfathomed wisdom. So the sense of weakness was never thrust upon me, and all during that day I seemed to grow in spirit. There came a greater self-respect, a reverence for my own individuality (you will not misunderstand me), an increased universality, a broader outlook, a wider experience. It was only one day as men count time, but I had lived—lived a century.

Monday morning came. After breakfast The Man arose and said:

“I will go with you, and get the bicycle.” (How did he know? I had not told him anything of my ride). “You can take the train from Jamison, which is about two miles from here. We can soon walk there.”

We found the wheel in the bushes, where I had left it by the roadside, and the man pushed it ahead of him with one hand through the mud, walking at a rapid[49] easy stride, arriving at the station just as the train pulled up. My benefactor lifted the bicycle lightly into the baggage-car, bought me a ticket, handed it to me, smiled and was gone. He did not say good-bye. I did not thank him for his kindness, and in fact, not a word was spoken after we left the little log house.

Albert Love, the conductor, I knew, as I often rode on his train. Helping me on the car, he laughingly said:

“Ah, you got caught in the storm and couldn’t get back, could you?”

“I didn’t want to,” I said.

“Oh! ah! Relative?” nodding his head in the direction of the retreating form of The Man.

“Yes; uncle.”

“Hem—they call him a crank here.—’Ll’board.”

I hurried from the depot to the office, and was only an hour behind time.

“You are late,” said Mr. Hustler, with a cynical, sickly smile which looked much like a scowl. “Only an hour. Make a note of it and give it to the time-keeper.”

I began my work and seemed to possess the strength of two women. My fingers struck the keys of the typewriter like lightning, and my head was clearer than ever before. When I took up a letter to answer, I saw clear through it, and struck the vital point at once; and yet all the time there was before me the mild and receptive face of The Man. The strange experience I had gone through was ever in my mind, and yet the work never disappeared from my desk as well and rapidly before. Where is that old philosopher who said, “The mind cannot think of two things at one time”?

At home I found my mother had waited tea for me until nine o’clock, when Martha Heath entered, and seeing the untouched supper and the look of despair on my mother’s face, knew the situation at a glance; for if a[51] smart woman cannot divine a thing, she will never, never, NEVER, understand it when told.

Martha Heath came to see Aspasia Hobbs, but Martha Heath did not ask for Aspasia Hobbs. She glanced at the face of the trembling old lady, who was trying to keep back the flood, saw the untasted supper, and Martha Heath then and there told a lie:

“Oh, I just dropped in to tell you Aspasia had gone home with one of the girls who was a little nervous, and perhaps would stay over Sunday with her. Who made your new dress, Mrs. Hobbs? Now don’t you feel big! You are so fond of appearing in print that you always wear calico!”

And the laugh that followed was catching, and even the good old grizzled Grimes felt the tension gone and she too chuckled. All three women sat down to tea, and Martha Heath ate supper again, although she had eaten at home before, and they chatted and the visitor talked a little more than was necessary. She told how she had that afternoon ran her bicycle into a nearsighted dude, who was chasing his hat, and how she not only upset the dude but ran over his hat; and how the dude called on a policeman to arrest her, but the policeman said he “darsen’t tackle the gal alone.” The mother forgot her troubles and the Grimes laughed so that she upset her tea, and when Martha Heath said “Good-bye girls,” they all laughed again, and Grimes wiped her brass-rimmed[52] spectacles with the corner of a big check apron and said, “Now ain’t she a queer un? and so kind too for her to come clear down here to tell us ’Pasia wasn’t killed entirely!”

Gentle and pious reader, you would not tell a lie, would you? Oh, no! But, Martha Heath had faith in me. I am self-reliant, strong, and able to take care of myself, and homely enough, thank Heaven! so I am no longer ogled on the street by blear eyed idlers. Martha Heath knows all this. She believes in me. Martha Heath has faith in Providence—have you?

Well, the work did fly! “Everything goes,” said Hustler as he looked on approvingly. Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, Friday, and some way I grew a little more thoughtful; not nervous, but serious. Friday night I scarcely slept an hour. It seemed as if I was about to depart to another and better world. At breakfast Saturday morning my mother said:

“It was a week ago to-day, Aspasia!”

“Oh, yes,” I said, inwardly.

“A week ago to-day! And now, never try to kill your old mother who loves you just the same whether you love her or not, by going off without telling us. Why, if Martha Heath hadn’t come and told us where you was, I would have died before morning. It was awful thoughtless of her too, not to have come here at once. She ought not to have put it off until ten o’clock.”

It was only nine, but we like to make our troubles as great as possible, for greater credit then is ours for bearing them.

I arose, kissed my good mother, and said: “Yes, I will always tell you myself hereafter when I am to be away—and so I tell you now. I am going away every Saturday to be gone over Sunday from now until October.”

“‘How sharper than a rattlesnake’s tooth it is to have a thankless child,’ the Bible says, and after all I have done for you too! Oh, it is too much to think my only child should thus desert me in my old age, and go off nobody knows where, and disgrace us all! Disgrace us, disgrace us, dis——”

It was too much, and she covered her face with her hands and burst into tears, rocking to and fro. Here Mrs. Grimes broke in with:

“Mrs. Hobbs, will you never—! Why, ’Pasia has more sense than all of us. She ain’t no fool. She ain’t—Why, didn’t I come three weeks lackin’ two days afore she was born, and didn’t I wash and dress her myself?” The gentle Grimes always availed herself of the opportunity to tell of my birth, to cut off any quibbler who might state I was not the child of Mr. and Mrs. Hobbs. “Mrs. Hobbs, you are a fool, and if ’Pasia ever does a bad thing it’ll be ’cause you drives her to it. I don’t know where she’s goin’, and dam if I care! I’ll trust her[54] anywhere! Go on, ’Pasia, and stay a year. You’ll find us here when you comes back.”

The Grimes cyclone had cleared the atmosphere, the rain had ceased, although the landscape was a trifle disheveled. I kissed the dear mother, grabbed my lunch-bag, and was gone.

I hurried through my work, dusted off the desk, locked the typewriter, and at two o’clock mounted my bicycle, went straight out Seneca street, over the iron bridge, on out the plank road, past Wendlings, through Springbrook, and stopped then for the first time, and standing on a rising slope of ground, I looked around in every direction. The dandelions seemed to cover the earth as with a carpet, and great masses of white hawthorn-trees in bridal array decked the landscape. The trees were bursting into leaf, and through the silence there came the drowsy hum of insects, and away off in the distance I could just detect the tinkle of a cowbell. To the left, two miles away, I saw a dense wood which seemed to transform the hill on which it stood into a great green mound.

“Yes, that surely is the place,” I said. I followed the plank road a mile further, then turned into a road which seemed like two paths side by side, as a line of green sward filled the centre of the roadway. I came to the wood, let down the bars, and back in the clearing was the log house, and out under the spreading branches[56] of a great oak sat The Man. He smiled the same sweet smile and motioned me to a seat beside him, and together we sat in silence. The calm and rest seemed complete.

“Let us sit here under the trees,” said The Man, “and I will explain several things which you must understand before I make known the higher truths which you are to give to mankind.

“Perhaps you have wondered why I do not go out into the world and teach face to face; and my reason, friend, for not doing this, is because I must needs disguise myself, if I go among the people. They would not comprehend me, but would shout, ‘Crucify him! Crucify him!’ as they did in the days of old. If I should go into the city and teach as the Master did, can you imagine the headlines in the Sunday papers? I would have followers of course, but even they would misunderstand me and quarrel among themselves about who should be the greatest in the Kingdom of Heaven. Many of them would fall down and worship me, and when I passed out of their sight there would be an ever-increasing number who would deify me, confounding my personality with that of a God, while the power I possess is possible for all men. They would say I was not a man but a ‘supreme being.’ On my metaphor they would construct a system of theology, and would use my words as a fence to hedge in[57] and limit truth, instead of accepting my principles as a broad base on which they might build a tower to touch the skies.

“A modern prophet has said, ‘I am astonished at the incredible amount of Judaism and formalism which still exists nineteen centuries after the Redeemer’s proclamation.’ ‘It is the letter that killeth,’ after his protest against the use of a dead symbolism.

“The new religion, which is the old, is so profound that it is not understood even now, and is a blasphemy to the greater number of professing Christians. The person of Christ is the centre of it. Redemption, eternal life, divinity, humanity, propitiation, judgment, Satan, heaven and hell—all these beliefs have been so materialized and coarsened that with a strange irony they present to us the spectacle of things having a profound meaning and yet carnally interpreted. Christian boldness and Christian liberty must be reconquered. It is the Church that is heretical; the Church it is whose soul is troubled and whose heart is timid. Whether we will or no there is an esoteric doctrine—there is a direct revelation, ‘Each man enters into God so much as God enters into him.’

“They would call me a heretic, and you must remember the heretic is one with faith plus. I do not limit faith to this and that, but extend it to all things. Not only is Sunday holy, but all time is holy. The chancel[58] is no more sacred than the pew. The world is God’s and all, everything is sacred to His use—our needs are His use.

“They would literalize my tropes to suit their own prejudices, and still insisting I was a god, distort my meaning in order to give a show of reason to their own wrong acts. This has been done over and over, as history tells you.

“Osiris, Thor, Memnon, Jupiter, Apollo, Gautama, and many others I could name of whom you know, were strong and brave men who lived on earth and bestowed great benefits on mankind; but ignorant and headstrong people, not content that these great men should live out their simple lives—for the great are simple, and pass for what they are—destroyed to a certain extent their good influence by affirming them to be not men at all; and to prove their statements, as untruthful people ever do strain heaven and earth to prove their allegations, they invented many stories and plans, such as that the great man was born in a ‘miraculous’ way—as if the natural birth was not miracle enough!—there being at the time a most erroneous idea that the act of vitalization was vicious and wrong, and this barbaric idea still remains with us to a certain extent.

“You remember in olden time priests (men who were believed to be in direct communication with Deity) were supposed to have power to grant absolution—that is, to forgive sin—and these granted indulgences; that is, leave[59] for the person to perform certain sinful acts, and by paying a certain sum to the priests no punishment was inflicted upon the sinner. The physical relations of the sexes were supposed by these heathen to be sinful (and indeed they certainly are under wrong conditions!) where the symbolic meaning is lost sight of, but like other sacraments, most holy when performed in right spirit, as symbolizing a perfect union of spirit, a complete giving up and surrender of soul to soul; and many men now, having stood with a woman before a priest and made certain promises, and having paid this priest a sum of money, believe that they have certain rights over this woman; and some women, I am sorry to say, believe too that it is their duty to submit to a loveless embrace thus desecrating the body, which is the temple of the Most High. And as it is a law of God that sin cannot go unpunished, you see the almost endless misery this transgression entails.

“Sin can only be wiped out with suffering. No community, scarcely a house is free from this taint; and yet up to to-day, no public teacher (we need teachers not preachers), has lifted his voice or used pen to right this wrong which men and women in their blindness have pulled down on themselves; but in fact men have been continually fixed in the wrong by the encouragement given to marriages of expediency and a multitude of unavowable motives, all of which are supposed to be consecrated by the religious ceremony.”

This was all so new to me that on Sunday morning I began the conversation by asking:

“What, you do not wish to do away with the sacredness of marriage and establish free love in its place?”

The Man was silent for a moment, then turned on me his gentle gaze and I was answered. I was going to apologize for the interruption, but The Man continued:

“Friend, I know what I have left unsaid. No living soul on earth to-day appreciates the vital importance and the sacredness of the true marriage as completely as I, and although I may touch briefly on certain subjects, you must not think I have spoken all there is to be said on the subject, for I know all spiritual laws—all natural law is spiritual, for behind each material fact stands the spiritual Truth.

“The universe is a whole, made up of parts. I know the relation of these parts to each other, and also the relation of parts to the whole. All knowledge is mine back to the First Great Cause, behind which no man can go, but still I am not without hope even of that. Now you of course can not comprehend all I will tell[61] you, but do not combat it. To attempt to refute, mentally or verbally, is to close the valves of the intellect so that you cannot receive. Those who endeavor to controvert use any weapon that is at hand, truth or error, to accomplish their purpose.

“I know lawyers who pride themselves on their ability to controvert any statement any man can make, and I also see that the Chautauqua Herald in endeavoring to complimentarily describe the Rev. Doctor Buckley, speaks of him as a controversialist. The controversionalist is a controversialist, and rushes in to test his steel as quickly with truth as with error. However, he is diplomatic, and endeavors not to kill the pet knight of his queen—Popular Opinion.

“Avoid controversy as you would a venomous snake. If you cultivate it you will find yourself constantly forming a rebuttal whenever you converse. Thus you lose all grasp on truth, and keep yourself ever outside of Heaven’s gate.

“Sit quietly, put prejudice, jealousy and malice out of your way, ever cultivate the receptive mood and you will only receive the good. Life should be reception, just as the oyster with shell partially open receives the waves bearing its food. What it needs is absorbed; what is not is washed away by the same force that brought it. Do not be afraid of receiving that which is harmful. Have faith—we are in God’s hand and He doeth all[62] things well. Does the oyster fear being poisoned? If you cannot accept what I say let it pass. Much that I tell you, you can absorb; if you do not need the rest the tide will bear it back all in good time.

“All violence of direction in will or belief is harmful and wrong, for man is only the medium of truth. He should be a prism, which receiving the great ray of light coming from the one Source of all life and light, reflects all the beauties of the rainbow, the symbol of promise, never omitting the actinic ray. It is within the reach of every man to so mirror the beauty and goodness of the Infinite, and there is no success short of this. Over the temple at Delphi was the inscription—‘Know Thyself.’ Over the temple of our hearts let us write the words in white and gold—‘Trust Thyself.’

“Again, you must believe when I say I know what is left unsaid. Truth is paradoxical, for it holds its perfect poise by the opposition of two forces, just as the earth lies in the soft arms of the atmosphere, poised between centrifugal and centripetal attraction.

“Now I have touched lightly on a few things, just to show you how men in their blindness and hot haste have perverted the good. Eyes accustomed to live in darkness are dazzled when they come to the light, and this partially explains why the great are misunderstood. Men measure them by their little foot rule, which is either six inches or two feet long, and while opinions[63] are divided as to whether the man is a genius or a fool, the majority decide in favor of the latter; but still there are many who, not content in seeing the wonders he performs needs must attribute to him powers which he does not possess. Man now speaks to his friend by word of mouth over a thousand miles of space. The voice with all its peculiar inflections and intonations, is heard and recognized. We know that this is in accordance with natural law, but if the secret was known only to one man, and the rest of us were in ignorance as to the process, we would attribute to that man supernatural powers; and when he died many would relate not only how they heard the voice coming from a thousand miles away, but how they also saw the man jump the entire distance, and many other fables would be invented as to the wonderful acts of this man.

“Now I am in possession of powers which work all smoothly in accordance with natural law, but which you would deem miraculous; but some day you and others will avail yourselves of these same laws, just as your voice can be recorded, bottled up and carried across the ocean in a box, and your body may die and the record of your voice still be preserved and the sounds brought forth at will from this little roll of gelatine. A year hence I will be many miles away, and you will be at home or walking in the fields, and I will speak to you and you will answer.

“Now, have you guessed why I do not reveal myself to the rabble and scatter my pearls before swine? I teach through others, giving them a little truth at a time, and they send it forth. I choose women to carry my messages, for they are more sensitive to truth—more alive—more impressionable! Men are aggressive and bent on conquest—their desire is for place and power, and to be seen and heard of men. But even this has its place, although low down in the scale—is one of the rounds in the spiral of evolution; and all in His own good time men shall be taught, but the work must be done by women. As we are taught in the old fable—which, by the way, is founded on truth—that through woman man fell, so shall woman lead him back to Eden; and even now I see the glorious dawn which betokens the sunrise.

“You now know why I have called you, and you understand too why I cannot afford to run the risk of partial present failure—for in God’s plans there is no failure—by standing before men. I am speaking to many other writers and speakers. Even as I sit here in this beautiful grove, telling them what to say, they are going forth over the whole world preaching the gospel to every creature. You have been surprised possibly to hear of men speaking the same truth at the same time in different parts of the world—now you know how it has come about. Your soul has not yet been quickened[65] into life, so I cannot speak with you excepting through this slow and crude man-contrivance which we call language; but there will soon come a time when we can lay this aside, and you will no longer be a captive to these tethering conditions; for you shall know the truth, and the truth shall make you free.”

So spake The Man, and the stars came out one by one as the daylight died out of the sky, and I sat and seemed filled to overflowing with wondering awe.

“Now take your note-book and pencil and let us take a little look out over the world and see things as they are,” The Man said. “You will then better understand what I will say later.

“The struggling march of Progress is marked on the map of human history by a deep continuous stain of red, but to-day we hear King William apologizing for his vast army by saying it is maintained not for war, but to preserve the peace of Europe.

“In twenty years the population of the United States has increased from forty to sixty-five millions, and our standing army has decreased in like proportion.