This file combines the two volumes of Westermarck’s book into one file.

You may go to Volume 1 (chapters 1 to 27),

Initial matter

Table of Contents

Volume 2 (chapters 28 to 53, etc.),

Initial matter

Table of Contents

First Edition 1906

Second Edition 1912

Reprinted 1924

THE frequent references made in the present work, on my own authority, to customs and ideas prevalent among the natives of Morocco, require a word of explanation. Seeing the close connection between moral opinions and magic and religious beliefs, I thought it might be useful for me to acquire first-hand knowledge of the folk-lore of some non-European people, and for various reasons I chose Morocco as my field of research. During the four years I spent there, largely among its country population, I have not only collected anthropological data, but tried to make myself familiar with the native way of thinking; and I venture to believe that this has helped me to understand various customs occurring at a stage of civilisation different from our own. I purpose before long to publish the detailed results of my studies in a special monograph on the popular religion and magics of the Moors.

For these researches I have derived much material support from the University of Helsingfors. I am also indebted to the Russian Minister at Tangier, M. B. de Bacheracht, for his kindness in helping me on several occasions when I was dependent on the Sultan’s Government. All the time I have had the valuable assistance of my Moorish friend Shereef ‘Abd-es-Salâm el-Baḳḳâli, to whom creditvi is due for the kind reception I invariably received from peasants and mountaineers, not generally noted for friendliness towards Europeans.

I beg to express my best thanks to Mr. Stephen Gwynn for revising the first thirteen chapters, and to Mr. H. C. Minchin for revising the remaining portion of the book. To their suggestions I am indebted for the improvement of many phrases and expressions. I have likewise to thank my friend Mr. Alex. F. Shand for kindly reading the proofs of the earlier chapters and giving me the benefit of his opinion.

Throughout the work the reader will easily find how much I owe to British science and thought—a debt which is greater than I can ever express.

E. W.

LONDON,

January, 1906.

THE present edition is only a reprint of the first, with a few inaccurate expressions corrected.

E. W.

LONDON,

July, 1912.

The origin of the present investigation, p. 1.—Its subject-matter, p. 1 sq.—Its practical usefulness, p. 2 sq.

The moral concepts essentially generalisations of tendencies in certain phenomena to call forth moral emotions, pp. 4–6.—The assumed universality or “objectivity” of moral judgments, p. 6 sq.—Theories according to which the moral predicates derive all their import from reason, “theoretical” or “practical,” p. 7 sq.—Our tendency to objectivise moral judgments, no sufficient ground for referring them to the province of reason, p. 8 sq.—This tendency partly due to the comparatively uniform nature of the moral consciousness, p. 9.—Differences of moral estimates resulting from circumstances of a purely intellectual character, pp. 9–11.—Differences of an emotional origin, pp. 11–13.—Quantitative, as well as qualitative, differences, p. 13.—The tendency to objectivise moral judgments partly due to the authority ascribed to moral rules, p. 14.—The origin and nature of this authority, pp. 14–17.—General moral truths non-existent, p. 17 sq.—The object of scientific ethics not to fix rules for human conduct, but to study the moral consciousness as a fact, p. 18.—The supposed dangers of ethical subjectivism, pp. 18–20.

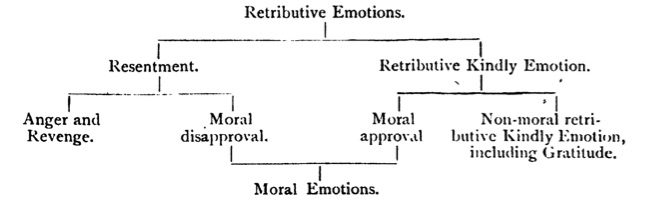

The moral emotions of two kinds: disapproval, or indignation, and approval, p. 21.—The moral emotions retributive emotions, disapproval forming a sub-species of resentment, and approval a sub-species of retributive kindly emotion, ibid.—Resentment an aggressive attitude of mind toward a cause of pain, p. 22 sq.—Dr. Steinmetz’s suggestion that revenge is essentially rooted in the feeling of power and superiority, and originally “undirected,” pp. 23–27.—The true import of the facts adduced as evidence for this hypothesis, pp. 27–30.—The collective responsibility usually involved in the institution of the blood-feud, pp. 30–32.—Explanation of it, pp. 32–35.—viiiThe strong tendency to discrimination which characterises resentment not wholly lost even behind the veil of common responsibility, p. 35 sq.—Revenge among the lower animals, p. 37 sq.—Violation of the “self-feeling” a common incentive to resentment, p. 38 sq.—But the reaction of the wounded “self-feeling” not necessarily, in the first place, concerned with the infliction of pain, p. 39 sq.—Revenge only a link in a chain of emotional phenomena for which “non-moral resentment” may be used as a common name, p. 40.—The origin of these phenomena, pp. 40–42.—Moral indignation closely connected with anger, p. 42 sq.—Moral indignation, like non-moral resentment, a reactionary attitude of mind directed towards the cause of inflicted pain, though the reaction sometimes turns against innocent persons, pp. 43–48.—In their administration of justice gods still more indiscriminate than men, pp. 48–51.—Reasons for this, p. 51 sq.—Sin looked upon in the light of a contagious matter, charged with injurious energy, pp. 52–57.—The curse looked upon as a baneful substance injuring or destroying anybody to whom it cleaves, p. 57 sq.—The tendency of curses to spread, pp. 58–60.—Their tendency to contaminate those who derive their origin from the infected individual, p. 60 sq.—The vicarious suffering involved in sin-transference not to be confounded with vicarious expiatory sacrifice, p. 61.—Why scapegoats are sometimes killed, pp. 61–64.—Why sacrificial victims are sometimes used as scapegoats, p. 64 sq.—Vicarious expiatory sacrifices, pp. 65–67.—The victim accepted as a substitute on the principle of social solidarity, p. 67 sq.—Expiatory sacrifices offered as ransoms, p. 68 sq.—Protests of the moral consciousness against the infliction of penal suffering upon the guiltless, pp. 70–72.

Whilst, in the course of mental evolution, the true direction of the hostile reaction involved in moral disapproval has become more apparent, its aggressive character has become more disguised, p. 73.—Kindness to enemies not a rule in early ethics, p. 73 sq.—At the higher stages of moral development retaliation condemned and forgiveness of enemies laid down as a duty, pp. 74–77.—The rule of retaliation and the rule of forgiveness not radically opposed to each other, p. 77 sq.—Why enlightened and sympathetic minds disapprove of resentment and retaliation springing from personal motives, p. 78 sq.—The aggressive character of moral disapproval has also become more disguised by the different way in which the aggressiveness displays itself, p. 79.—Retributive punishment condemned, and the end of punishment considered to be either to deter from crime, or to reform the criminal, or to repress crime by eliminating or secluding him, pp. 79–81.—Objections to these theories, p. 82 sq.—Facts which, to some extent, fill up the gap between the theory of retribution and the utilitarian theories of punishment, pp. 84–91.—The aggressive element in moral disapproval has undergone a change which tends to conceal its true nature by narrowing the channel in which it discharges itself, deliberate and discriminating resentment being apt to turn against the will rather than against the willer, p. 91 sq.—Yet it is the instinctive desire to inflict counter-pain that gives to moral indignation its most important characteristic, p. 92 sq.—Retributive kindly emotion a friendly attitude of mind towards a cause of pleasure, p. 93 sq.—Retributive kindly emotion among the lower animals, p. 94.—Its intrinsic object, p. 94 sq.—The want of discrimination which is sometimes found in retributive kindness, p. 95.—Moral approval a kind of retributive kindly emotion, ibid.—Moral approval sometimes bestows its favours upon undeserving individuals for the merits of others, pp. 95–97.—Explanation of this, p. 97 sq.—Protests against the notion of vicarious merit, p. 98 sq.

Refutation of the opinion that moral emotions only arise in consequence of moral judgments, p. 100 sq.—However, moral judgments, being definite expressions of moral emotions, help us to discover the true nature of these emotions, p. 101.—Disinterestedness and apparent impartiality characteristics by which moral indignation and approval are distinguished from other, non-moral, kinds of resentment or retributive kindly emotion, pp. 101–104.—Besides, a moral emotion has a certain flavour of generality, p. 104 sq.—The analysis of the moral emotions which has been attempted in this and the two preceding chapters holds true not only of such emotions as we feel on account of the conduct of others, but of such emotions as we feel on account of our own conduct as well, pp. 105–107.

We may feel disinterested resentment, or disinterested retributive kindly emotion, on account of an injury inflicted, or a benefit conferred, upon another person with whose pain, or pleasure, we sympathise, and in whose welfare we take a kindly interest, p. 108.—Sympathetic feelings based on association, p. 109 sq.—Only when aided by the altruistic sentiment sympathy induces us to take a kindly interest in the feelings of our neighbours, and tends to produce disinterested retributive emotions, p. 110 sq.—Sympathetic resentment to be found in all animal species which possess altruistic sentiments, p. 111 sq.—Sympathetic resentment among savages, p. 113 sq.—Sympathetic resentment may not only be a reaction against sympathetic pain, but may be directly produced by the cognition of the signs of anger (punishment, language, &c.), pp. 114–116.—Disinterested antipathies, p. 116 sq.—Sympathy springing from an altruistic sentiment may also produce disinterested kindly emotion, p. 117.—Disinterested likings, ibid.—Why disinterestedness, apparent impartiality, and the flavour of generality have become characteristics by which so-called moral emotions are distinguished from other retributive emotions, p. 117 sq.—Custom not only a public habit, but a rule of conduct, p. 118.—Custom conceived of as a moral rule, p. 118 sq.—In early society customs the only moral rules ever thought of, p. 119.—The characteristics of moral indignation to be sought for in its connection with custom, p. 120.—Custom characterised by generality, disinterestedness, and apparent impartiality, p. 120 sq.—Public indignation lies at the bottom of custom as a moral rule, p. 121 sq.—As public indignation is the prototype of moral disapproval, so public approval is the prototype of moral approval, p. 122.—Moral disapproval and approval have not always remained inseparably connected with the feelings of any special society, p. 122 sq.—Yet they remain to the last public emotions if not in reality, then as an ideal, p. 123.—Refutation of the opinion that the original form of the moral consciousness has been the individual’s own conscience, p. 123 sq.—The antiquity of moral resentment, p. 124.—The supposition that remorse is unknown among the lower races contradicted by facts, p. 124 sq.—Criticism of Lord Avebury’s statement that modern savages seem to be almost entirely wanting in moral feeling, pp. 125–129.—The antiquity of moral approval, p. 129 sq.

Our analysis to be concerned with moral concepts formed by the civilised mind, p. 131.—Moral concepts among the lower races, pp. 131–133.—Language a rough generaliser, p. 133.—Analysis of the concepts bad, vice, and wrong, p. 134.—Of ought and duty, pp. 134–137.—Of right, as an adjective, pp. 137–139.—Of right, as a substantive, p. 139 sq.—Of the relations between rights and duties, p. 140 sq.—Of injustice and justice, pp. 141–145.—Of good, pp. 145–147.—Of virtue, pp. 147–149.—Of the relation between virtue and duty, p. 149 sq.—Of merit, p. 150 sq.—Of the relation between merit and duty, p. 151 sq.—The question of the super-obligatory, pp. 152–154.—The question of the morally indifferent, pp. 154–157.

How we can get an insight into the moral ideas of mankind at large, p. 158.—The close connection between the habitualness and the obligatoriness of custom, p. 159.—Though every public habit is not a custom, involving an obligation, men’s standard of morality is not independent of their practice, p. 159 sq.—The study of moral ideas to a large extent a study of customs, p. 160.—But custom never covers the whole field of morality, and the uncovered space grows larger in proportion as the moral consciousness develops, p. 160 sq.—At the lower stages of civilisation custom the sole rule for conduct, p. 161.—Even kings described as autocrats tied by custom, p. 162.—In competition with law custom frequently carries the day, p. 163 sq.—Custom stronger than law and religion combined, p. 164.—The laws themselves command obedience more as customs than as laws, ibid.—Many laws were customs before they became laws, p. 165.—The transformation of customs into laws, p. 165 sq.—Laws as expressions of moral ideas, pp. 166–168.—Punishment and indemnification, p. 168 sq.—Definition of punishment, p. 169 sq.—Savage punishments inflicted upon the culprit by the community at large, pp. 170–173.—By some person or persons invested with judicial authority, pp. 173–175.—The development of judicial organisation out of a previous system of lynch-law, p. 175.—Out of a previous system of private revenge, p. 176.—Public indignation displays itself not only in punishment, but to a certain extent in the custom of revenge, p. 176 sq.—The social origin of the lex talionis, pp. 177–180.—The transition from revenge to punishment, and the establishment of a central judicial and executive authority, pp. 180–183.—The jurisdiction of chiefs, p. 183 sq.—The injured party or the accuser acting as executioner, but not as judge, p. 184 sq.—The existence of punishment and judicial organisation among a certain people no exact index to its general state of culture, p. 185.—The supposition that punishment has been intended to act as a deterrent, p. 185 sq.—Among various semi-civilised and civilised peoples the criminal law has assumed a severity which far surpasses the rigour of the lex talionis, pp. 186–183.—Wanton cruelty not a general characteristic of the public justice of savages, pp. 188–190. Legislators referring to the deterrent effects of punishment, p. 190 sq.—The practice of punishing criminals in public, p. 191 sq.—The punishment actually inflicted on the criminal in many cases much less severe than the punishment with which the law threatens him, p. 192 sq.—The detection of criminals was in earlier times much rarer and more uncertain than it is now, p. 193.—The chief explanation of the great severity of certain xicriminal codes lies in their connection with despotism or religion or both, pp. 193–198.—Punishment may also be applied as a means of deterring from crime, p. 198 sq.—But the scope which justice leaves for determent pure and simple is not wide, p. 199.—The criminal law of a community on the whole a faithful exponent of moral sentiments prevalent in that community at large, pp. 199–201.

Definitions of the term “conduct,” p. 202 sq.—The meaning of the word “act,” p. 203 sq.—The meaning of the word “intention,” p. 204.—There can be only one intention in one act, p. 204 sq. The moral judgments which we pass on acts do not really relate to the event, but to the intention, p. 205 sq.—A person morally accountable also for his deliberate wishes, p. 206.—A deliberate wish is a volition, p. 206 sq.—The meaning of the word “motive,” p. 207.—Motives which are volitions fall within the sphere of moral valuation, ibid.—The motive of an act may be an intention, but an intention belonging to another act, ibid.—Even motives which consist of non-volitional conations may indirectly exercise much influence on moral judgments, p. 207 sq.—Refutation of Mill’s statement that “the motive has nothing to do with the morality of the action,” p. 208 sq.—Moral judgments really passed upon men as acting or willing, not upon acts or volitions in the abstract, p. 209.—Forbearances morally equivalent to acts, p. 209 sq.—Distinction between forbearances and omissions, p. 210.—Moral judgments refer not only to willing, but to not-willing as well, not only to acts and forbearances, but to omissions, p. 210 sq.—Negligence, heedlessness, and rashness, p. 211.—Moral judgments of blame concerned with not-willing only in so far as this not-willing is attributed to a defect of the “will,” p. 211 sq.—Distinction between conscious omissions and forbearances, and between not-willing to refrain from doing and willing to do, p. 212.—The “known concomitants of acts,” p. 213.—Absence of volitions also gives rise to moral praise, p. 213 sq.—The meaning of the term “conduct,” p. 214.—The subject of a moral judgment is, strictly speaking, a person’s will, or character, conceived as the cause either of volitions or of the absence of volitions, p. 214 sq.—Moral judgments that are passed on emotions or opinions really refer to the will, p. 215 sq.

Cases in which no distinction is made between intentional and accidental injuries, pp. 217–219.—Yet even in the system of self-redress intentional or foreseen injuries often distinguished from unintentional and unforeseen injuries, pp. 219–221.—A similar distinction made in the punishments inflicted by many savages, p. 221 sq.—Uncivilised peoples who entirely excuse, or do not punish, persons for injuries which they have inflicted by mere accident, p. 222 sq.—Peoples of a higher culture who punish persons for bringing about events without any fault of theirs, pp. 223–226.—At the earlier stages of civilisation gods, in particular, attach undue importance to the outward aspect of conduct, pp. 226–231.—Explanation of all these facts, pp. 231–237.—The great influence which the outward event exercises upon moral estimates even among ourselves, pp. 238–240.—Carelessness generally not punished if no injurious result follows, p. 241.—An unsuccessful attempt to commit a criminal act, if punished at all, as a rule punished much less xiiseverely than the accomplished act, p. 241 sq.—Exceptions to this rule, p. 242.—The question, which attempts should be punished, p. 243.—The stage at which an attempt begins to be criminal, and the distinction between attempts and acts of preparation, p. 243 sq.—The rule that an outward event is requisite for the infliction of punishment, p. 244 sq.—Exceptions to this rule, p. 245.—Explanation of laws referring to unsuccessful attempts, pp. 245–247.—Moral approval influenced by external events, p. 247.—Owing to its very nature, the moral consciousness, when sufficiently influenced by thought, regards the will as the only proper object of moral disapproval or praise, p. 247 sq.

An agent not responsible for anything which he could not be aware of, p. 249.—The irresponsibility of animals, pp. 249–251.—Resentment towards an animal which has caused some injury, p. 251.—At the lower stages of civilisation animals deliberately treated as responsible beings, ibid.—The custom of blood-revenge extended to the animal world, pp. 251–253.—Animals exposed to regular punishment, pp. 253–255.—The origin of the mediæval practice of punishing animals, p. 255 sq.—Explanation of the practice of retaliating upon animals, pp. 256–260.—At the earlier stages of civilisation even inanimate things treated as if they were responsible agents, pp. 260–262.—Explanation of this, pp. 262–264.—The total or partial irresponsibility of childhood and early youth, pp. 264–267.—According to early custom, children sometimes subject to the rule of retaliation, p. 267.—Parents responsible for the deeds of their children, p. 267 sq.—In Europe there has been a tendency to raise the age at which full legal responsibility commences, p. 268 sq.—The irresponsibility of idiots and madmen, p. 269 sq.—Idiots and insane persons objects of religious reverence, p. 270 sq.—Lunatics treated with great severity or punished for their deeds, pp. 271–274.—Explanation of this, p. 274 sq.—The ignorance of which lunatics have been victims in the hands of lawyers, pp. 275–277.—The total or partial irresponsibility of intoxicated persons, p. 277 sq.—Drunkenness recognised as a ground of extenuation, pp. 278–280.—Not recognised as a ground of extenuation, p. 280 sq.—Explanation of these facts, p. 281 sq.

Motives considered only in proportion as the moral judgment is influenced by reflection, p. 283.—Little consideration for the sense of duty as a motive, ibid.—Somewhat greater discrimination shown in regard to motives consisting of powerful non-volitional conations, p. 283 sq.—Compulsion as a ground of extenuation, p. 284 sq.—“Compulsion by necessity,” pp. 285–287.—Self-defence, pp. 288–290.—Self-redress in the case of adultery, and other survivals of the old system of self-redress, pp. 290–294.—The moral distinction made between an injury which a person inflicts deliberately, in cold blood, and one which he inflicts in the heat of the moment, on provocation, pp. 294–297.—Explanation of this distinction, p. 297 sq.—The pressure of a non-volitional motive on the will as a ground of extenuation, p. 298 sq.—That moral judgments are generally passed, in the first instance, with reference to acts immediately intended, and consider motives only in proportion as the judgment is influenced by reflection, holds good not only of moral blame, but of moral praise, pp. 299–302.

Why in early moral codes the so-called negative commandments are much more prominent than the positive commandments, p. 303.—The little cognisance which the criminal laws of civilised nations take of forbearances and omissions, p. 303 sq.—The more scrutinising the moral consciousness, the greater the importance which it attaches to positive commandments, p. 304 sq.—Yet the customs of all nations contain not only prohibitions, but positive injunctions as well, p. 305.—The unreflecting mind apt to exaggerate the guilt of a person who out of heedlessness or rashness causes harm by a positive act, ibid.—Early custom and law may be anxious enough to trace an event to its source, pp. 305–307.—But they easily fail to discover where there is guilt or not, and, in case of carelessness, to determine the magnitude of the offender’s guilt, p. 307 sq.—The opinion that a person is answerable for all the damage which directly ensues from an act of his, even though no foresight could have reasonably been expected to look out for it, p. 308 sq.—On the other hand, little or no censure passed on him whose want of foresight or want of self-restraint is productive of suffering, if only the effect is sufficiently remote, p. 309 sq.—The moral emotions may as naturally give rise to judgments on human character as to judgments on human conduct, p. 310.—Even when a moral judgment immediately refers to a distinct act, it takes notice of the agent’s will as a whole, p. 310 sq.—The practice of punishing a second or third offence more severely than the first, p. 311 sq.—The more a moral judgment is influenced by reflection, the more it scrutinises the character which manifests itself in that individual piece of conduct by which the judgment is occasioned, p. 312 sq.—But however superficial it be, it always refers to a will conceived of as a continuous entity, p. 313.

Explanation of the fact that moral judgments are passed on conduct and character, p. 314.—The correctness of this explanation proved by the circumstance that not only moral emotions, but non-moral retributive emotions as well, are felt with reference to phenomena exactly similar in nature to those on which moral judgments are passed, pp. 314–319.—Whether moral or non-moral, a retributive emotion is essentially directed towards a sensitive and volitional entity, or self, conceived of as the cause of pleasure or the cause of pain, p. 319.—The futility of other attempts to solve the problem, p. 319 sq.—The nature of the moral emotions also gives us the key to the problem of the co-existence of moral responsibility with the general law of cause and effect, p. 320.—The theory according to which responsibility, in the ordinary sense of the term, and moral judgments generally, are inconsistent with the notion that the human will is determined by causes, p. 320 sq.—Yet, as a matter of fact, moral indignation and moral approval are felt by determinists and libertarians alike, p. 321 sq.—Explanation of the fallacy which lies at the bottom of the conception that moral valuation is inconsistent with determinism, p. 322.—Causation confounded with compulsion, pp. 322–324.—The difference between fatalism and determinism, pp. 324–326.—The moral emotions not concerned with the origin of the innate character, p. 326.

Necessity of restricting the investigation to the more important modes of conduct with which the moral consciousness is concerned, p. 327 sq.—The six groups into which these modes of conduct may be divided, p. 328.—The most sacred duty which we owe to our fellow-creatures generally considered to be regard for their lives, ibid.—Among various uncivilised peoples human life said to be held very cheap, p. 328 sq.—Among others homicide or murder said to be hardly known, p. 329 sq.—In other instances homicide expressly said to be regarded as wrong, p. 330 sq.—In every society custom prohibits homicide within a certain circle of men, p. 331.—Savages distinguish between an act of homicide committed within their own community and one where the victim is a stranger, pp. 331–333.—In various instances, however, the rule, “Thou shalt not kill,” applies even to foreigners, p. 333 sq.—Some uncivilised peoples said to have no wars, p. 334.—Savages’ recognition of intertribal rights in times of peace obvious from certain customs connected with their wars, p. 334 sq.—Savage custom does not always allow indiscriminate slaughter even in warfare, p. 335 sq.—The readiness with which savages engage in war, p. 337.—The old distinction between injuries committed against compatriots and harm done to foreigners remains among peoples more advanced in culture, p. 337 sq.—The readiness with which such peoples wage war on foreign nations, and the estimation in which the successful warrior is held, pp. 338–340.—The life of a guest sacred, p. 340.—The commencement of international hostilities preceded by special ceremonies, ibid.—Warfare in some cases condemned, or a distinction made between just and unjust war, pp. 340–342.—Even in war the killing of an enemy under certain circumstances prohibited, either by custom or by enlightened moral opinion, pp. 342–344.

Homicide of any kind condemned by the early Christians, p. 345.—Their total condemnation of warfare, p. 345 sq.—This attitude towards war was soon given up, pp. 346–348.—The feeling that a soldier scarcely could make a good Christian, p. 348.—Penance prescribed for those who had shed blood in war, p. 348 sq.—Wars forbidden by popes, p. 349.—The military Christianity of the Crusades, pp. 348–352.—Chivalry, pp. 352–354.—The intimate connection between chivalry and religion displayed in tournaments, p. 354 sq.—The practice of private war, p. 355 sq.—The attitude of the Church towards private war, p. 356.—The Truce of God, p. 357.—The main cause of the abolition of private war was the increase of the authority of emperors or kings, p. 357 sq.—War looked upon as a judgment of God, p. 358.—The attitude adopted by the great Christian congregations towards war one of sympathetic approval, pp. 359–362.—Religious protests against war, pp. 362–365.—Freethinkers’ opposition to war, pp. 365–367.—The idea of a perpetual peace, p. 367.—The awakening spirit of nationalism, and the glorification of war, p. 367 sq.—Arguments against arbitration, p. 368.—The opposition against war rapidly increasing, p. 368 sq.—The prohibition of needless destruction in war, p. 369 sq.—The survival, in modern civilisation, of the old feeling that the life of a foreigner is not equally sacred with that of a countryman, p. 370.—The behaviour of European colonists towards coloured races, p. 370 sq.

Sympathetic resentment felt on account of the injury suffered by the victim a potent cause of the condemnation of homicide, p. 372 sq.—No such resentment felt if the victim is a member of another group, p. 373.—Why extra-tribal homicide is approved of, ibid.—Superstition an encouragement to extra-tribal homicide, ibid.—The expansion of the altruistic sentiment largely explains why the prohibition of homicide has come to embrace more and more comprehensive circles of men, ibid.—Homicide viewed as an injury inflicted upon the survivors, p. 373 sq.—Conceived as a breach of the “King’s peace,” p. 374.—Stigmatised as a disturbance of public tranquillity and an outrage on public safety, ibid.—Homicide disapproved of because the manslayer gives trouble to his own people, p. 374 sq.—The idea that a manslayer is unclean, pp. 375–377.—The influence which this idea has exercised on the moral judgment of homicide, p. 377.—The disapproval of the deed easily enhanced by the spiritual danger attending on it, as also by the inconvenient restrictions laid on the tabooed manslayer and the ceremonies of purification to which he is subject, p. 377 sq.—The notion of a persecuting ghost may be replaced by the notion of an avenging god, pp. 378–380.—The defilement resulting from homicide particularly shunned by gods, p. 380 sq.—Priests forbidden to shed human blood, p. 381 sq.—Reasons for Christianity’s high regard for human life, p. 382.

Parricide the most aggravated form of murder, pp. 383–386.—The custom of abandoning or killing parents who are worn out with age or disease, p. 386 sq.—Its causes, pp. 387–390.—The custom of abandoning or killing persons suffering from some illness, p. 391 sq.—Its causes, p. 392 sq.—The father’s power of life and death over his children, p. 393 sq.—Infanticide among many savage races permitted or even enjoined by custom, pp. 394–398.—The causes of infanticide, and how it has grown into a regular custom, pp. 398–402.—Among many savages infanticide said to be unheard of or almost so, p. 402 sq.—The custom of infanticide not a survival of earliest savagery, but seems to have grown up under specific conditions in later stages of development, p. 403.—Savages who disapprove of infanticide, p. 403 sq.—The custom of infanticide in most cases requires that the child should be killed immediately or soon after its birth, p. 404 sq.—Infanticide among semi-civilised or civilised races, pp. 405–411.—The practice of exposing new-born infants vehemently denounced by the early Fathers of the Church, p. 411.—Christian horror of infanticide, p. 411 sq.—The punishment of infanticide in Christian countries, p. 412 sq.—Feticide among savages, p. 413 sq.—Among more civilised nations, p. 414 sq.—According to Christian views, a form of murder, p. 415 sq.—Distinctions between an embryo informatus and an embryo formatus, p. 416 sq.—Modern legislation and opinion concerning feticide, p. 417.

The husband’s power of life and death over his wife among many of the lower races, p. 418 sq.—The right of punishing his wife capitally not universally xvigranted to the husband in uncivilised communities, p. 419.—The husband’s power of life and death among peoples of a higher type, ibid.—Uxoricide punished less severely than matricide, p. 419 sq.—The estimate of a woman’s life sometimes lower than that of a man’s, sometimes equal to it, sometimes higher, p. 420 sq.—The master’s power of life and death over his slave, p. 421 sq.—The right, among many savages, of killing his slave at his own discretion expressly denied to the master, p. 422 sq.—The murder of another person’s slave largely regarded as an offence against the property of the owner, but not exclusively looked upon in this light, p. 423.—When the system of blood-money prevails, the price paid for the life of a slave less than that paid for the life of a freeman, ibid.—Among the nations of archaic culture, also, the life of a slave held in less estimation than that of a freeman, but not even the master in all circumstances allowed to put his slave to death, pp. 423–426.—Efforts of the Christian Church to secure the life of the slave against the violence of the master, p. 426.—But neither the ecclesiastical nor the secular legislation gave him the same protection as was bestowed upon the free member of the Church and State, pp. 426–428.—In modern times, in Christian countries, the life of the negro slave was only inadequately protected by law, p. 428 sq.—Why the life of a slave is held in so little regard, p. 429.—The killing of a freeman by a slave, especially if the victim be his owner, commonly punished more severely than if the same act were done by a free person, p. 429 sq.—In the estimate of life a distinction also made between different classes of freemen, p. 430 sq.—The magnitude of the crime may depend not only on the rank of the victim, but on the rank of the manslayer as well, pp. 431–433.—Explanation of this influence of class, p. 433.—In progressive societies each member of the society at last admitted to be born with an equal claim to the right to live, ibid.

The prevalence of human sacrifice, pp. 434–436.—This practice much more frequently found among barbarians and semi-civilised peoples than among genuine savages, p. 436 sq.—Among some peoples it has been noticed to become increasingly prevalent in the course of time, p. 437.—Human sacrifice partly due to the idea that gods have an appetite for human flesh or blood, p. 437 sq.—Sometimes connected with the idea that gods require attendants, p. 438.—Moreover, an angry god may be appeased simply by the death of him or those who aroused his anger, or of some representative of the offending community, or of somebody belonging to the kin of the offender, pp. 438–440.—Human sacrifice chiefly a method of life-insurance, based on the idea of substitution, p. 440.—Human victims offered in war, before a battle, or during a siege, p. 440 sq.—For the purpose of stopping or preventing epidemics, p. 441 sq.—For the purpose of putting an end to a devastating famine, p. 442 sq.—For the purpose of preventing famine, p. 443 sq.—Criticism of Dr. Frazer’s hypothesis that the human victim who is killed for the purpose of ensuring good crops is regarded as a representative of the corn-spirit and is slain as such, pp. 444–451.—Human victims offered with a view to getting water, p. 451 sq.—With a view to averting perils arising from the sea or from rivers, pp. 452–454.—For the purpose of preventing the death of some particular individual, especially a chief or a king, from sickness, old age, or other circumstances, pp. 454–457.—For the purpose of helping other men into existence, p. 457 sq.—The killing of the first-born child, or the first-born son, p. 458 sq.—Explanation of this practice, pp. 459–461.—Human sacrifices offered in connection with the foundation of buildings, p. 461 sq.—The building-sacrifice, like other kinds of human sacrifice, probably based on the idea of substitution, pp. 462–464.—The belief that xviithe soul of the victim is converted into a protecting demon, p. 464 sq.—The human victim regarded as a messenger, p. 465 sq.—Human sacrifice not an act of wanton cruelty, p. 466.—The king or chief sometimes sacrificed, ibid.—The victims frequently prisoners of war or other aliens, or slaves, or criminals, pp. 466–468.—The disappearance of human sacrifice, p. 468.—Human sacrifice condemned, p. 465 sq.—Practices intended to replace it, p. 469.—Human effigies or animals offered instead of men, p. 469 sq.—Human sacrifices succeeded by practices involving the effusion of human blood without loss of life, p. 470.—Bleeding or mutilation practised for the same purpose as human sacrifice, p. 470 sq.—Why the penal sacrifice of offenders has outlived all other forms of human sacrifice, p. 471.—Human beings sacrificed to the dead in order to serve them as slaves, wives, or companions, pp. 472–474.—This custom dwindling into a survival, p. 475.—The funeral sacrifice of men and animals also seems to involve an intention to vivify the spirits of the deceased with blood, p. 475 sq.—Manslayers killed in order to satisfy their victims’ craving for revenge, p. 476.

The prevalence of the custom of blood-revenge, pp. 477–479.—Blood-revenge regarded not only as a right, but as a duty, p. 479 sq.—This duty in the first place regarded as a duty to the dead, whose spirit is believed to find no rest after death until the injury has been avenged, p. 481 sq.—Blood-revenge a form of human sacrifice, p. 482.—Blood-revenge also practised on account of the injury inflicted on the survivors, p. 482 sq.—Murder committed within the family or kin left unavenged, p. 483.—The injury inflicted on the relatives of the murdered man suggests not only revenge, but reparation, ibid.—The taking of life for life may itself, in a way, serve as compensation, p. 483 sq.—Various methods of compensation, p. 484.—The advantages of the practice of composition, p. 484 sq.—Its disadvantages, p. 485.—The importance of these disadvantages depends on the circumstances in each special case, p. 486 sq.—Among many peoples the rule of revenge strictly followed, and to accept compensation considered disgraceful, p. 487.—The acceptance of compensation does not always mean that the family of the slain altogether renounce their right of revenge, p. 487 sq.—The acceptance of compensation allowed as a justifiable alternative for blood-revenge, or even regarded as the proper method of settling the case, p. 488 sq.—The system of compensation partly due to the pressure of some intervening authority, p. 489 sq.—The adoption of this method for the settling of disputes a sign of weakness, p. 491.—When the central power of jurisdiction is firmly established, the rule of life for life regains its sway, ibid.—A person may forfeit his right to live by other crimes besides homicide, p. 491 sq.—Opposition to and arguments against capital punishment, pp. 492–495.—Modern legislation has undergone a radical change with reference to capital punishment, p. 495.—Arguments against its abolition, p. 495 sq.—The chief motive for retaining it in modern legislation, p. 496.

Duelling resorted to as a means of bringing to an end hostilities between different groups of people, p. 497 sq.—Duels fought for the purpose of settling disputes between individuals, either by conferring on the victor the right of possessing xviiithe object of the strife, or by gratifying a craving for revenge and wiping off the affront, pp. 498–502.—The circumstances to which these customs are due, p. 503 sq.—The duel as an ordeal or “judgment of God,” p. 504 sq.—The judicial duel fundamentally derived its efficacy as a means of ascertaining the truth from its connection with an oath, p. 505 sq. How it came to be regarded as an appeal to the justice of God, p. 506 sq.—The decline and disappearance of the judicial duel, p. 507.—The modern duel of honour, pp. 507–509.—Its causes, p. 509.—Arguments adduced in support of it, p. 509 sq.

In the case of bodily injuries the magnitude of the offence, other things being equal, proportionate to the harm inflicted, pp. 511–513.—The degree of the offence also depends on the station of the parties concerned, and in some cases the infliction of pain held allowable or even a duty, p. 513.—Children using violence against their parents, ibid.—Parents’ right to inflict corporal punishment on their children, p. 513 sq.—The husband’s right to chastise his wife, pp. 514–516.—The master’s right to inflict corporal punishment on his slave, p. 516 sq.—The maltreatment of another person’s slave regarded as an injury done to the master, rather than to the slave, p. 517.—Slaves severely punished for inflicting bodily injuries on freemen, p. 510.—The penalties or fines for bodily injuries influenced by the class or rank of the parties when both of them are freemen, p. 518 sq.—Distinction between compatriots and aliens with reference to bodily injuries, p. 519.—The infliction of sufferings on vanquished enemies, p. 519 sq.—The right to bodily integrity influenced by religious differences, p. 520—Forfeited by the commission of a crime, p. 520 sq.—Amputation or mutilation of the offending member has particularly been in vogue among peoples of culture, p. 521 sq.—The disappearance of corporal punishment in Europe, p. 522.—Corporal punishment has been by preference a punishment for poor and common people or slaves, p. 522 sq.—The status of a person influencing his right to bodily integrity with reference to judicial torture, p. 523 sq.—Explanation of the moral notions regarding the infliction of bodily injuries, p. 524.—The notions that an act of bodily violence involves a gross insult, and that corporal punishment disgraces the criminal more than any other form of penalty, p. 524 sq.

The mother’s duty to rear her children, p. 526.—The husband’s and father’s duty to protect and support his family, pp. 526–529.—The parents’ duty of taking care of their offspring in the first place based on the sentiment of parental affection, p. 529.—The universality not only of the maternal, but of the paternal, sentiment in mankind, pp. 529–532.—Marital affection among savages, p. 532.—Explanation of the simplest paternal and marital duties, p. 533—Children’s duty of supporting their aged parents, pp. 533–538. The duty of assisting brothers and sisters, p. 538.—Of assisting more distant relatives, pp. 538–540.—Uncivilised peoples as a rule described as kind towards members of their own community or tribe, enjoin charity between themselves as a duty, and praise generosity as a virtue, pp. 540–546.—Among many savages the old people, in particular, have a claim to support and assistance, p. 546.—The sick often carefully attended to, pp. 546–548.—xixAccounts of uncharitable savages, p. 548 sq.—Among semi-civilised and civilised nations charity universally regarded as a duty, and often strenuously enjoined by their religions, pp. 549–556.—In the course of progressing civilisation the obligation of assisting the needy has been extended to wider and wider circles of men, pp. 556–558.—The duty of tending wounded enemies in war, p. 558.—Explanation of the gradual expansion of the duty of charity, p. 559.—This duty in the first place based on the altruistic sentiment, p. 559 sq.—Egoistic motives for the doing of good to fellow-creatures, p. 560.—By niggardliness a person may expose himself to supernatural dangers, pp. 560–562.—Liberality may entail supernatural reward, p. 562 sq.—The curses and blessings of the poor partly account for the fact that charity has come to be regarded as a religious duty, pp. 563–565.—The chief cause of the extraordinary stress which the higher religions put on the duty of charity seems to lie in the connection between almsgiving and sacrifice, the poor becoming the natural heirs of the god, p. 565.—Instances of sacrificial food being left for, or distributed among, the poor, p. 565 sq.—Almsgiving itself regarded as a form of sacrifice, or taking the place of it, pp. 566–569.

Instances of great kindness displayed by savages towards persons of a foreign race, pp. 570–572.—Hospitality a universal custom among the lower races and among the peoples of culture at the earlier stages of their civilisation, pp. 572–574.—The stranger treated with special marks of honour, and enjoying extraordinary privileges as a guest, pp. 574–576.—Custom may require that hospitality should be shown even to an enemy, p. 576 sq.—To protect a guest looked upon as a most stringent duty, p. 577 sq.—Hospitality in a remarkable degree associated with religion, pp. 578–580.—The rules of hospitality in the main based on egoistic considerations, p. 581.—The stranger, supposed to bring with him good luck or blessings, pp. 581–583.—The blessings of a stranger considered exceptionally powerful, p. 583 sq.—The visiting stranger regarded as a potential source of evil, p. 584.—His evil wishes and curses greatly feared, owing partly to his quasi-supernatural character, partly to the close contact in which he comes with the host and his belongings, pp. 584–590.—Precautions taken against the visiting stranger, pp. 590–593.—Why no payment is received from a guest, p. 593 sq.—The duty of hospitality limited by time, p. 594 sq.—The cause of this, p. 595 sq.—The decline of hospitality in progressive communities, p. 596.

The right of personal freedom never absolute, p. 597.—Among some savages a man’s children are in the power of the head of their mother’s family or of their maternal uncle, p. 597 sq.—Among the great bulk of existing savages children are in the power of their father, though he may to some extent have to share his authority with the mother, p. 598 sq.—The extent of the father’s power subject to great variations, p. 599.—Among some savages the father’s authority practically very slight, p. 599 sq.—Other savages by no means deficient in filial piety, p. 600 sq.—The period during which the paternal authority lasts, p. 601 sq.—Old age commands respect and gives authority, pp. 603–605.—Superiority of age also gives a certain amount xxof power, p. 605 sq.—The reverence for old age may cease when the grey-head becomes an incumbrance to those around him, and imbecility may put an end to the father’s authority over his family, p. 606 sq.—Paternal, or parental, authority and filial reverence at their height among peoples of archaic culture, pp. 607–613.—Among these peoples we also meet with reverence for the elder brother, for persons of a superior age generally, and especially for the aged, p. 614 sq.—Decline of the paternal authority in Europe, p. 615 sq.—Christianity not unfavourable to the emancipation of children, though obedience to parents was enjoined as a Christian duty, p. 616 sq.—The Roman notions of paternal rights and filial duties have to some extent survived in Latin countries, p. 617 sq.—Sources of the parental authority, p. 618 sq.—Among savages, in particular, filial regard is largely regard for one’s elders or the aged, p. 619.—Causes of the regard for old age, pp. 619–621.—The chief cause of the connection between filial submissiveness and religious beliefs the extreme importance attached to parental curses and blessings, pp. 621–626.—Why the blessings and curses of parents are supposed to possess an unusual power, p. 626 sq.—Explanation of the extraordinary development of the paternal authority in the archaic State, p. 627 sq.—Causes of the downfall of the paternal power, p. 628.

Among the lower races the wife frequently said to be the property or slave of her husband, p. 629 sq.—Yet even in such cases custom has not left her entirely destitute of rights, p. 630 sq.—The so-called absolute authority of husbands over their wives not to be taken too literally, p. 631 sq.—The bride-price does not eo ipso confer on the husband absolute rights over her, p. 632 sq.—The hardest drudgeries of life often said to be imposed on the women, p. 633 sq.—In early society each sex has its own pursuits, p. 634.—The rules according to which the various occupations of life are divided between the sexes are on the whole in conformity with the indications given by nature, p. 635 sq.—This division of labour emphasised by custom and superstition, p. 636 sq.—It is apt to mislead the travelling stranger, p. 637.—It gives the wife authority within the circle which is exclusively her own, ibid.—Rejection of the broad statement that the lower races in general hold their women in a state of almost complete subjection, pp. 638–646.—The opinion that a people’s civilisation may be measured by the position held by the women not correct, at least so far as the earlier stages of culture are concerned, p. 646 sq.—The position of woman among the peoples of archaic civilisation, pp. 647–653.—Christianity tended to narrow the remarkable liberty granted to married women under the Roman Empire, p. 653 sq.—Christian orthodoxy opposed to the doctrine that marriage should be a contract on the footing of perfect equality between husband and wife, p. 654 sq.—Criticism of the hypothesis that the social status of women is connected with the system of tracing descent, p. 655 sq.—The authority of a husband who lives with his wife in the house or community of her father, p. 656 sq.—Wives’ subjection to their husbands in the first place due to the men’s instinctive desire to exert power, and to the natural inferiority of women in such qualities of body and mind as are essential for personal independence, p. 657.—Elements in the sexual impulse which lead to domination on the part of the man and to submission on the part of the woman, p. 657 sq.—But if the man’s domination is carried beyond the limits of female love, the woman feels it as a burden, p. 658 sq.—In extreme cases of oppression, at any rate, the community at large would sympathise with her, and the public resentment against the oppressor would result in customs or laws limiting the xxihusband’s rights, p. 659.—The offended woman may count upon the support of her fellow-sisters, ibid.—The children’s affection and regard for their mother gives her power, ibid.—The influence which economic conditions exercise on the position of woman, pp. 659–661.—The status of wives connected with the ideas held about the female sex in general, p. 661.—Woman regarded as intellectually and morally vastly inferior to man, especially among nations more advanced in culture, pp. 661–663.—Progress in civilisation has exercised an unfavourable influence on the position of woman by widening the gulf between the sexes, p. 663.—Religion has contributed to her degradation by regarding her as unclean, p. 663 sq.—Women excluded from religious worship and sacred functions, pp. 664–666.—The notion that woman is unclean, however, gives her a secret power over her husband, as women are supposed to be better versed in magic than men, pp. 666–668.—The curses of women greatly feared, p. 668.—Woman as an asylum, p. 668 sq.—In archaic civilisation the status of married women was affected by the fact that the house-father was invested with some part of the power which formerly belonged to the clan, p. 669.—Causes of the decrease of the husband’s authority over his wife in modern civilisation, ibid.

Definition of slavery, p. 670 sq.—The distribution of slavery and its causes among savages, pp. 671–674.—The earliest source of slavery was probably war or conquest, p. 674 sq.—Intra-tribal slavery among savages, p. 675 sq.—The master’s power over his slave among slave-holding savages, pp. 676–678.—Among the lower races slaves are generally treated kindly, pp. 678–680.—Intra-tribal slaves, especially such as are born in the house, generally treated better than extra-tribal or purchased slaves, p. 680 sq.—Slavery among the nations of archaic culture, pp. 681–693.—The attitude of Christianity towards slavery, pp. 693–700.—The supposed causes of the extinction of slavery in Europe, pp. 697–701.—The chief cause the transformation of slavery into serfdom, p. 701.—Serfdom only a transitory condition leading up to a state of entire liberty, pp. 701–703.—The attitude of the Church towards serfdom, p. 703 sq.—The negro slavery in the colonies of European countries and the Southern States of America, and the legislation relating to it, pp. 704–711.—The support given to it by the clergy, pp. 711–713.—The want of sympathy for, or positive antipathy to, the coloured race, p. 713 sq.—The opinions regarding slavery and the condition of slaves influenced by altruistic considerations, p. 714 sq.—The condition of slaves influenced by the selfish considerations of their masters, p. 715 sq.

THE main object of this book will perhaps be best explained by a few words concerning its origin.

Its author was once discussing with some friends the point how far a bad man ought to be treated with kindness. The opinions were divided, and, in spite of much deliberation, unanimity could not be attained. It seemed strange that the disagreement should be so radical, and the question arose, Whence this diversity of opinion? Is it due to defective knowledge, or has it a merely sentimental origin? And the problem gradually expanded. Why do the moral ideas in general differ so greatly? And, on the other hand, why is there in many cases such a wide agreement? Nay, why are there any moral ideas at all?

Since then many years have passed, spent by the author in trying to find an answer to these questions. The present work is the result of his researches and thoughts.

The first part of it will comprise a study of the moral concepts: right, wrong, duty, justice, virtue, merit, &c. Such a study will be found to require an examination into the moral emotions, their nature and origin, as also into the relations between these emotions and the various 2moral concepts. There will then be a discussion of the phenomena to which such concepts are applied—the subjects of moral judgments. The general character of these phenomena will be scrutinised, and an answer sought to the question why facts of a certain type are matters of moral concern, while other facts are not. Finally, the most important of these phenomena will be classified, and the moral ideas relating to each class will be stated, and, so far as possible, explained.

An investigation of this kind cannot be confined to feelings and ideas prevalent in any particular society or at any particular stage of civilisation. Its subject-matter is the moral consciousness of mankind at large. It consequently involves the survey of an unusually rich and varied field of research—psychological, ethnographical, historical, juridical, theological. In the present state of our knowledge, when monographs on most of the subjects involved are wanting, I presume that such an undertaking is, strictly speaking, too big for any man; at any rate it is so for the writer of this book. Nothing like completeness can be aimed at. Hypotheses of varying degrees of probability must only too often be resorted to. Even the certainty of the statements on which conclusions are based is not always beyond a doubt. But though fully conscious of the many defects of his attempt, the author nevertheless ventures to think himself justified in placing it before the public. It seems to him that one of the most important objects of human speculation cannot be left in its present state of obscurity; that at least a glimpse of light must be thrown upon it by researches which have extended over some fifteen years; and that the main principles underlying the various customs of mankind may be arrived at even without subjecting these customs to such a full and minute treatment as would be required of an anthropological monograph.

Possibly this essay, in spite of its theoretical character, may even be of some practical use. Though rooted in the emotional side of our nature, our moral 3opinions are in a large measure amenable to reason. Now in every society the traditional notions as to what is good or bad, obligatory or indifferent, are commonly accepted by the majority of people without further reflection. By tracing them to their source it will be found that not a few of these notions have their origin in sentimental likings and antipathies, to which a scrutinising and enlightened judge can attach little importance; whilst, on the other hand, he must account blamable many an act and omission which public opinion, out of thoughtlessness, treats with indifference. It will, moreover, appear that a moral estimate often survives the cause from which it sprang. And no unprejudiced person can help changing his views if he be persuaded that they have no foundation in existing facts.

THAT the moral concepts are ultimately based on emotions either of indignation or approval, is a fact which a certain school of thinkers have in vain attempted to deny. The terms which embody these concepts must originally have been used—indeed they still constantly are so used—as direct expressions of such emotions with reference to the phenomena which evoked them. Men pronounced certain acts to be good or bad on account of the emotions those acts aroused in their minds, just as they called sunshine warm and ice cold on account of certain sensations which they experienced, and as they named a thing pleasant or painful because they felt pleasure or pain. But to attribute a quality to a thing is never the same as merely to state the existence of a particular sensation or feeling in the mind which perceives it. Such an attribution must mean that the thing, under certain circumstances, makes a certain impression on the mind. By calling an object warm or pleasant, a person asserts that it is apt to produce in him a sensation of heat or a feeling of pleasure. Similarly, to name an act good or bad, ultimately implies that it is apt to give rise to an emotion of approval or disapproval in him who pronounces the judgment. Whilst not affirming the actual existence of any specific emotion in the mind of the person judging or of anybody else, the predicate of a moral judgment attributes to the subject a tendency to arouse an emotion. The moral 5concepts, then, are essentially generalisations of tendencies in certain phenomena to call forth moral emotions.

However, as is frequently the case with general terms, these concepts are mentioned without any distinct idea of their contents. The relation in which many of them stand to the moral emotions is complicated; the use of them is often vague; and ethical theorisers, instead of subjecting them to a careful analysis, have done their best to increase the confusion by adapting the meaning of the terms to fit their theories. Very commonly, in the definition of the goodness or badness of acts, reference is made, not to their tendencies to evoke emotions of approval or indignation, but to the causes of these tendencies, that is, to those qualities in the acts which call forth moral emotions. Thus, because good acts generally produce pleasure and bad acts pain, goodness and badness have been identified with the tendencies of acts to produce pleasure or pain. The following statement of Sir James Stephen is a clearly expressed instance of this confusion, so common among utilitarians:—“Speaking generally, the acts which are called right do promote, or are supposed to promote general happiness, and the acts which are called wrong do diminish, or are supposed to diminish it. I say, therefore, that this is what the words ‘right’ and ‘wrong’ mean, just as the words ‘up’ and ‘down’ mean that which points from or towards the earth’s centre of gravity, though they are used by millions who have not the least notion of the fact that such is their meaning, and though they were used for centuries and millenniums before any one was or even could be aware of it.”1 So, too, Bentham maintained that words like “ought,” “right,” and “wrong,” have no meaning unless interpreted in accordance with the principle of utility;2 and James Mill was of opinion that “the very morality” of the act lies, not in the sentiments raised in the breast of him who perceives or contemplates it, but in “the consequences of the act, good or evil, and their being 6within the intention of the agent.”3 He adds that a rational assertor of the principle of utility approves of an action “because it is good,” and calls it good “because it conduces to happiness.”4 This, however, is to invert the sequence of the facts, since, properly speaking, an act is called good because it is approved of, and is approved of by an utilitarian in so far as it conduces to happiness.

1 Stephen, Liberty, Equality, Fraternity, p. 338.

2 Bentham, Principles of Morals and Legislation, p. 4.

3 James Mill, Fragment on Mackintosh, pp. 5, 376.

4 Ibid. p. 368.

Such confusion of terms cannot affect the real meaning of the moral concepts. It is true that he who holds that “actions are right in proportion as they tend to promote happiness, wrong as they tend to produce the reverse of happiness,”5 may, by a merely intellectual process, pass judgment on the moral character of particular acts; but, if he is an utilitarian from conviction, his first principle, at least, has an emotional origin. The case is similar with many of the moral judgments ordinarily passed by men. They are applications of some accepted general rule: conformity or non-conformity to the rule decides the rightness or wrongness of the act judged of. But whether the rule be the result of a person’s independent deductions, or be based upon authority, human or divine, the fact that his moral consciousness recognises it as valid implies that it has an emotional sanction in his own mind.

5 Stuart Mill, Utilitarianism, p. 9 sq.

Whilst the import of the predicate of a moral judgment may thus in every case be traced back to an emotion in him who pronounces the judgment, it is generally assumed to possess the character of universality or “objectivity” as well. The statement that an act is good or bad does not merely refer to an individual emotion; as will be shown subsequently, it always has reference to an emotion of a more public character. Very often it even implies some vague assumption that the act must be recognised as good or bad by everybody who possesses a sufficient knowledge of the case and of all attendant circumstances, and who has a “sufficiently developed” 7moral consciousness. We are not willing to admit that our moral convictions are a mere matter of taste, and we are inclined to regard convictions differing from our own as errors. This characteristic of our moral judgments has been adduced as an argument against the emotionalist theory of moral origins, and has led to the belief that the moral concepts represent qualities which are discerned by reason.

Cudworth, Clarke, Price, and Reid are names which recall to our mind a theory according to which the morality of actions is perceived by the intellect, just as are number, diversity, causation, proportion. “Morality is eternal and immutable,” says Richard Price. “Right and wrong, it appears, denote what actions are. Now whatever any thing is, that it is, not by will, or degree, or power, but by nature and necessity. Whatever a triangle or circle is, that it is unchangeably and eternally…. The same is to be said of right and wrong, of moral good and evil, as far as they express real characters of actions. They must immutably and necessarily belong to those actions of which they are truly affirmed.”6 And as having a real existence outside the mind, they can only be discerned by the understanding. It is true that this discernment is accompanied with an emotion: “Some impressions of pleasure or pain, satisfaction or disgust, generally attend our perceptions of virtue and vice. But these are merely their effects and concomitants, and not the perceptions themselves, which ought no more to be confounded with them, than a particular truth (like that for which Pythagoras offered a hecatomb) ought to be confounded with the pleasure that may attend the discovery of it.”7

6 Price, Review of the Principal Questions in Morals, pp. 63, 74 sq.

7 Ibid. p. 63.

According to another doctrine, the moral predicates, though not regarded as expressions of “theoretical” truth, nevertheless derive all their import from reason from “practical” or “moral” reason, as it is variously 8called. Thus Professor Sidgwick holds that the fundamental notions represented by the word “ought” or “right,” which moral judgments contain expressly or by implication, are essentially different from all notions representing facts of physical or psychical experience, and he refers such judgments to the “reason,” understood as a faculty of cognition. By this he implies “that what ought to be is a possible object of knowledge, i.e., that what I judge ought to be, must, unless I am in error, be similarly judged by all rational beings who judge truly of the matter.” The moral judgments contain moral truths, and “cannot legitimately be interpreted as judgments respecting the present or future existence of human feelings or any facts of the sensible world.”8

8 Sidgwick, Methods of Ethics, pp. 25, 33 sq.

Yet our tendency to objectivise the moral judgments is no sufficient ground for referring them to the province of reason. If, in this respect, there is a difference between these judgments and others that are rooted in the subjective sphere of experience, it is, largely, a difference in degree rather than in kind. The aesthetic judgments, which indisputably have an emotional origin, also lay claim to a certain amount of “objectivity.” By saying of a piece of music that it is beautiful, we do not merely mean that it gives ourselves aesthetic enjoyment, but we make a latent assumption that it must have a similar effect upon everybody who is sufficiently musical to appreciate it. This objectivity ascribed to judgments which have a merely subjective origin springs in the first place from the similarity of the mental constitution of men, and, generally speaking, the tendency to regard them as objective is greater in proportion as the impressions vary less in each particular case. If “there is no disputing of tastes,” that is because taste is so extremely variable; and yet even in this instance we recognise a certain “objective” standard by speaking of a “bad” and a “good” taste. On the other hand, if the appearance of objectivity in the moral judgments is so illusive as to 9make it seem necessary to refer them to reason, that is partly on account of the comparatively uniform nature of the moral consciousness.

Society is the school in which men learn to distinguish between right and wrong. The headmaster is Custom, and the lessons are the same for all. The first moral judgments were pronounced by public opinion; public indignation and public approval are the prototypes of the moral emotions. As regards questions of morality, there was, in early society, practically no difference of opinion; hence a character of universality, or objectivity, was from the very beginning attached to all moral judgments. And when, with advancing civilisation, this unanimity was to some extent disturbed by individuals venturing to dissent from the opinions of the majority, the disagreement was largely due to facts which in no way affected the moral principle, but had reference only to its application.

Most people follow a very simple method in judging of an act. Particular modes of conduct have their traditional labels, many of which are learnt with language itself; and the moral judgment commonly consists simply in labelling the act according to certain obvious characteristics which it presents in common with others belonging to the same group. But a conscientious and intelligent judge proceeds in a different manner. He carefully examines all the details connected with the act, the external and internal conditions under which it was performed, its consequences, its motive; and, since the moral estimate in a large measure depends upon the regard paid to these circumstances, his judgment may differ greatly from that of the man in the street, even though the moral standard which they apply be exactly the same. But to acquire a full insight into all the details which are apt to influence the moral value of an act is in many cases anything but easy, and this naturally increases the disagreement. There is thus in every advanced society a diversity of opinion regarding the moral value of certain modes of conduct which results from circumstances of a purely 10intellectual character—from the knowledge or ignorance of positive facts,—and involves no discord in principle.

Now it has been assumed by the advocates of various ethical theories that all the differences of moral ideas originate in this way, and that there is some ultimate standard which must be recognised as authoritative by everybody who understands it rightly. According to Bentham, the rectitude of utilitarianism has been contested only by those who have not known their own meaning:—“When a man attempts to combat the principle of utility … his arguments, if they prove anything, prove not that the principle is wrong, but that, according to the applications he supposes to be made of it, it is misapplied.”9 Mr. Spencer, to whom good conduct is that “which conduces to life in each and all,” believes that he has the support of “the true moral consciousness,” or “moral consciousness proper,” which, whether in harmony or in conflict with the “pro-ethical” sentiment, is vaguely or distinctly recognised as the rightful ruler.10 Samuel Clarke, the intuitionist, again, is of opinion that if a man endowed with reason denies the eternal and necessary moral differences of things, it is the very same “as if a man that has the use of his sight, should at the same time that he beholds the sun, deny that there is any such thing as light in the world; or as if a man that understands Geometry or Arithmetick, should deny the most obvious and known proportions of lines or numbers.”11 In short, all disagreement as to questions of morals is attributed to ignorance or misunderstanding.

9 Bentham, Principles of Morals and Legislation, p. 4 sq.

10 Spencer, Principles of Ethics, i. 45, 337 sq.

11 Clarke, Discourse concerning the Unchangeable Obligations of Natural Religion, p. 179.

The influence of intellectual considerations upon moral judgments is certainly immense. We shall find that the evolution of the moral consciousness to a large extent consists in its development from the unreflecting to the reflecting, from the unenlightened to the enlightened. All higher emotions are determined by cognitions, they arise 11from “the presentation of determinate objective conditions”;12 and moral enlightenment implies a true and comprehensive presentation of those objective conditions by which the moral emotions, according to their very nature, are determined. Morality may thus in a much higher degree than, for instance, beauty be a subject of instruction and of profitable discussion, in which persuasion is carried by the representation of existing data. But although in this way many differences may be accorded, there are points in which unanimity cannot be reached even by the most accurate presentation of facts or the subtlest process of reasoning.

12 Marshall, Pain, Pleasure, and Aesthetics, p. 83.

Whilst certain phenomena will almost of necessity arouse similar moral emotions in every mind which perceives them clearly, there are others with which the case is different. The emotional constitution of man does not present the same uniformity as the human intellect. Certain cognitions inspire fear in nearly every breast; but there are brave men and cowards in the world, independently of the accuracy with which they realise impending danger. Some cases of suffering can hardly fail to awaken compassion in the most pitiless heart; but the sympathetic dispositions of men vary greatly, both in regard to the beings with whose sufferings they are ready to sympathise, and with reference to the intensity of the emotion. The same holds good for the moral emotions. The existing diversity of opinion as to the rights of different classes of men and of the lower animals, which springs from emotional differences, may no doubt be modified by a clearer insight into certain facts, but no perfect agreement can be expected as long as the conditions under which the emotional dispositions are formed remain unchanged. Whilst an enlightened mind must recognise the complete or relative irresponsibility of an animal, a child, or a madman, and must be influenced in its moral judgment by the motives of an act—no intellectual enlightenment, no scrutiny of facts, can decide how far the interests of the 12lower animals should be regarded when conflicting with those of men, or how far a person is bound, or allowed, to promote the welfare of his nation, or his own welfare, at the cost of that of other nations or other individuals. Professor Sidgwick’s well-known moral axiom, “I ought not to prefer my own lesser good to the greater good of another,”13 would, if explained to a Fuegian or a Hottentot, be regarded by him, not as self-evident, but as simply absurd; nor can it claim general acceptance even among ourselves. Who is that “Another” to whose greater good I ought not to prefer my own lesser good? A fellow-countryman, a savage, a criminal, a bird, a fish—all without distinction? It will, perhaps, be argued that on this, and on all other points of morals, there would be general agreement, if only the moral consciousness of men were sufficiently developed.14 But then, when speaking of a “sufficiently developed” moral consciousness (beyond insistence upon a full insight into the governing facts of each case), we practically mean nothing else than agreement with our own moral convictions. The expression is faulty and deceptive, because, if intended to mean anything more, it presupposes an objectivity of the moral judgments which they do not possess, and at the same time seems to be proving what it presupposes. We may speak of an intellect as sufficiently developed to grasp a certain truth, because truth is objective; but it is not proved to be objective by the fact that it is recognised as true by a “sufficiently developed” intellect. The objectivity of truth lies in the recognition of facts as true by all who understand them fully, whilst the appeal to a sufficient knowledge assumes their objectivity. To the verdict of a perfect intellect, that is, an intellect which knows everything existing, all would submit; but we can form no idea of a moral consciousness which could lay claim to a similar authority. If the believers in an all-13good God, who has revealed his will to mankind, maintain that they in this revelation possess a perfect moral standard, and that, consequently, what is in accordance with such a standard must be objectively right, it may be asked what they mean by an “all-good” God. And in their attempt to answer this question, they would inevitably have to assume the objectivity they wanted to prove.

13 Sidgwick, op. cit. p. 383.

14 This, in fact, was the explanation given by Professor Sidgwick himself in a conversation which I had with him regarding his moral axioms.

The error we commit by attributing objectivity to moral estimates becomes particularly conspicuous when we consider that these estimates have not only a certain quality, but a certain quantity. There are different degrees of badness and goodness, a duty may be more or less stringent, a merit may be smaller or greater.15 These quantitative differences are due to the emotional origin of all moral concepts. Emotions vary in intensity almost indefinitely, and the moral emotions form no exception to this rule. Indeed, it may be fairly doubted whether the same mode of conduct ever arouses exactly the same degree of indignation or approval in any two individuals. Many of these differences are of course too subtle to be manifested in the moral judgment; but very frequently the intensity of the emotion is indicated by special words, or by the way in which the judgment is pronounced. It should be noticed, however, that the quantity of the estimate expressed in a moral predicate is not identical with the intensity of the moral emotion which a certain mode of conduct arouses on a special occasion. We are liable to feel more indignant if an injury is committed before our eyes than if we read of it in a newspaper, and yet we admit that the degree of wrongness is in both cases the same. The quantity of moral estimates is determined by the intensity of the emotions which their objects tend to evoke under exactly similar external circumstances.

15 It will be shown in a following chapter why there are no degrees of rightness. This concept implies accordance with the moral law. The adjective “right” means that duty is fulfilled.

14Besides the relative uniformity of moral opinions, there is another circumstance which tempts us to objectivise moral judgments, namely, the authority which, rightly or wrongly, is ascribed to moral rules. From our earliest childhood we are taught that certain acts are right and that others are wrong. Owing to their exceptional importance for human welfare, the facts of the moral consciousness are emphasised in a much higher degree than any other subjective facts. We are allowed to have our private opinions about the beauty of things, but we are not so readily allowed to have our private opinions about right and wrong. The moral rules which are prevalent in the society to which we belong are supported by appeals not only to human, but to divine, authority, and to call in question their validity is to rebel against religion as well as against public opinion. Thus the belief in a moral order of the world has taken hardly less firm hold of the human mind than the belief in a natural order of things. And the moral law has retained its authoritativeness even when the appeal to an external authority has been regarded as inadequate. It filled Kant with the same awe as the star-spangled firmament. According to Butler, conscience is “a faculty in kind and in nature supreme over all others, and which bears its own authority of being so.”16 Its supremacy is said to be “felt and tacitly acknowledged by the worst no less than by the best of men.”17 Adam Smith calls the moral faculties the “vicegerents of God within us,” who “never fail to punish the violation of them by the torments of inward shame and self-condemnation; and, on the contrary, always reward obedience with tranquillity of mind, with contentment, and self-satisfaction.”18 Even Hutcheson, who raises the question why the moral sense should not vary in different men as the palate does, considers it 15“to be naturally destined to command all the other powers.”19

16 Butler, ‘Sermon II.—Upon Human Nature,’ in Analogy of Religion, &c. p. 403.

17 Dugald Stewart, Philosophy of the Active and Moral Powers of Man, i. 302.

18 Adam Smith, Theory of Moral Sentiments, p. 235.

19 Hutcheson, System of Moral Philosophy, i. 61.