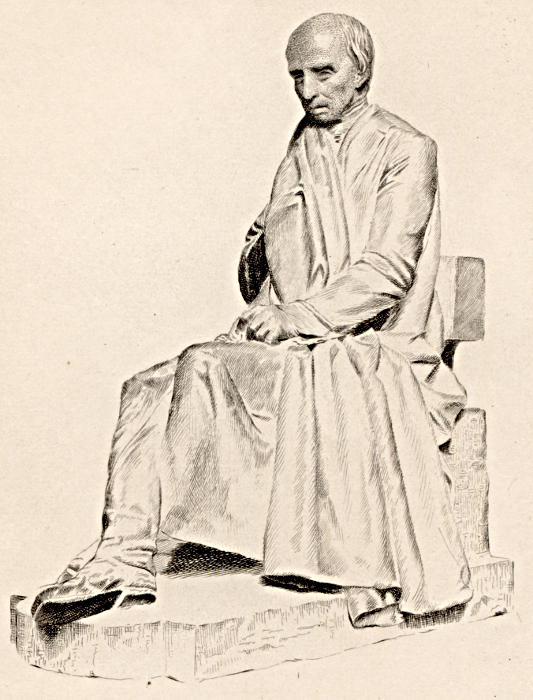

William Wordsworth

after Thomas Woolner

Printed by Ch Wittmann Paris

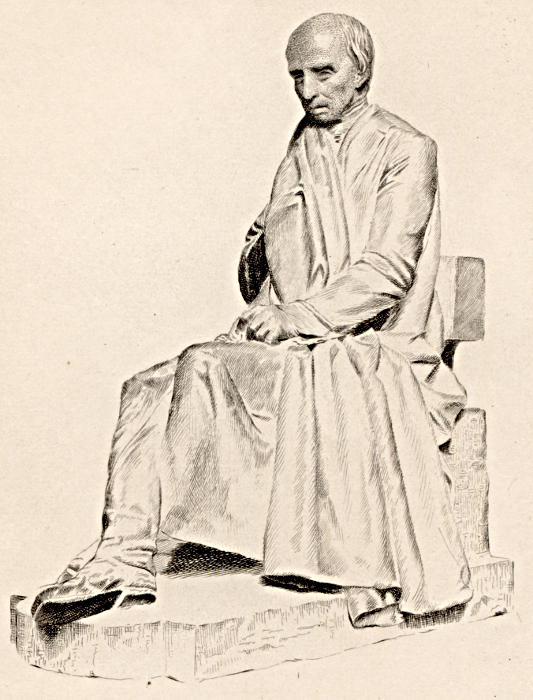

William Wordsworth

after Thomas Woolner

Printed by Ch Wittmann Paris

THE POETICAL WORKS

OF

WILLIAM WORDSWORTH

EDITED BY

WILLIAM KNIGHT

VOL. VIII

Gallow Hill

Yorkshire

London

MACMILLAN AND CO., Ltd.

New York: Macmillan & Co.

1896

All rights reserved.

| PAGE | |

| 1834 | |

| Lines suggested by a Portrait from the Pencil of F. Stone | 1 |

| The foregoing Subject resumed | 6 |

| To a Child | 7 |

| Lines written in the Album of the Countess of Lonsdale, Nov. 5, 1834 | 8 |

| 1835 | |

| “Why art thou silent? Is thy love a plant” | 12 |

| To the Moon | 13 |

| To the Moon | 15 |

| Written after the Death of Charles Lamb | 17 |

| Extempore Effusion upon the Death of James Hogg | 24 |

| Upon seeing a Coloured Drawing of the Bird of Paradise in an Album | 29 |

| “Desponding Father! mark this altered bough” | 31 |

| “Four fiery steeds impatient of the rein” | 31 |

| To —— | 32 |

| Roman Antiquities discovered at Bishopstone, Herefordshire | 33 |

| St. Catherine of Ledbury | 34 |

| “By a blest Husband guided, Mary came” | 35 |

| [vi]“Oh what a Wreck! how changed in mien and speech!” | 36 |

| 1836 | |

| November 1836 | 37 |

| To a Redbreast—(In Sickness) | 38 |

| 1837 | |

| “Six months to six years added he remained” | 39 |

| Memorials of a Tour in Italy, 1837—To Henry Crabb Robinson | 41 |

| I. Musings near Aquapendente, April, 1837 | 42 |

| II. The Pine of Monte Mario at Rome | 58 |

| III. At Rome | 59 |

| IV. At Rome—Regrets—in Allusion to Niebuhr and other Modern Historians | 60 |

| V. Continued | 61 |

| VI. Plea for the Historian | 61 |

| VII. At Rome | 62 |

| VIII. Near Rome, in Sight of St. Peter’s | 63 |

| IX. At Albano | 64 |

| X. “Near Anio’s stream, I spied a gentle Dove” | 65 |

| XI. From the Alban Hills, looking towards Rome | 65 |

| XII. Near the Lake of Thrasymene | 66 |

| XIII. Near the same Lake | 67 |

| XIV. The Cuckoo at Laverna | 67 |

| XV. At the Convent of Camaldoli | 72 |

| XVI. Continued | 73 |

| XVII. At the Eremite or Upper Convent of Camaldoli | 74 |

| XVIII. At Vallombrosa | 75 |

| XIX. At Florence | 78 |

| XX. Before the Picture of the Baptist, by Raphael, in the Gallery at Florence | 79 |

| [vii]XXI. At Florence—From Michael Angelo | 80 |

| XXII. At Florence—From Michael Angelo | 81 |

| XXIII. Among the Ruins of a Convent in the Apennines | 82 |

| XXIV. In Lombardy | 83 |

| XXV. After leaving Italy | 84 |

| XXVI. Continued | 85 |

| At Bologna, in Remembrance of the late Insurrections, 1837.—I. | 86 |

| II. Continued | 86 |

| III. Concluded | 87 |

| “What if our numbers barely could defy” | 87 |

| A Night Thought | 88 |

| The Widow on Windermere Side | 89 |

| 1838 | |

| To the Planet Venus | 92 |

| “Hark! ’tis the Thrush, undaunted, undeprest” | 93 |

| “’Tis He whose yester-evening’s high disdain” | 94 |

| Composed at Rydal on May Morning, 1838 | 94 |

| Composed on a May Morning, 1838 | 97 |

| A Plea for Authors, May 1838 | 99 |

| “Blest Statesman He, whose Mind’s unselfish will” | 101 |

| Valedictory Sonnet | 102 |

| 1839 | |

| Sonnets upon the Punishment of Death— | |

| I. Suggested by the View of Lancaster Castle (on the Road from the South) | 103 |

| II. “Tenderly do we feel by Nature’s law” | 104 |

| [viii]III. “The Roman Consul doomed his sons to die” | 105 |

| IV. “Is Death, when evil against good has fought” | 106 |

| V. “Not to the object specially designed” | 106 |

| VI. “Ye brood of conscience—Spectres! that frequent” | 107 |

| VII. “Before the world had past her time of youth” | 107 |

| VIII. “Fit retribution, by the moral code” | 108 |

| IX. “Though to give timely warning and deter” | 109 |

| X. “Our bodily life, some plead, that life the shrine” | 109 |

| XI. “Ah, think how one compelled for life to abide” | 110 |

| XII. “See the Condemned alone within his cell” | 110 |

| XIII. Conclusion | 111 |

| XIV. Apology | 112 |

| “Men of the Western World! in Fate’s dark book” | 112 |

| 1840 | |

| To a Painter | 114 |

| On the same Subject | 115 |

| Poor Robin | 116 |

| On a Portrait of the Duke of Wellington upon the Field of Waterloo, by Haydon | 118 |

| 1841 | |

| Epitaph in the Chapel-Yard of Langdale, Westmoreland | 120 |

| 1842 | |

| “Intent on gathering wool from hedge and brake” | 122 |

| Prelude, prefixed to the Volume entitled “Poems chiefly of Early and Late Years” | 123 |

| Floating Island | 125 |

| “The Crescent-moon, the Star of Love” | 127 |

| [ix]“A Poet!—He hath put his heart to school” | 127 |

| “The most alluring clouds that mount the sky” | 128 |

| “Feel for the wrongs to universal ken” | 129 |

| In Allusion to various Recent Histories and Notices of the French Revolution | 130 |

| Continued | 131 |

| Concluded | 131 |

| “Lo! where she stands fixed in a saint-like trance” | 132 |

| The Norman Boy | 132 |

| The Poet’s Dream | 135 |

| Suggested by a Picture of the Bird of Paradise | 140 |

| To the Clouds | 142 |

| Airey-Force Valley | 146 |

| “Lyre! though such power do in thy magic live” | 147 |

| Love lies Bleeding | 148 |

| “They call it Love lies bleeding! rather say” | 150 |

| Companion to the Foregoing | 150 |

| The Cuckoo-Clock | 151 |

| “Wansfell! this Household has a favoured lot” | 153 |

| “Though the bold wings of Poesy affect” | 154 |

| “Glad sight wherever new with old” | 154 |

| 1843 | |

| “While beams of orient light shoot wide and high” | 156 |

| Inscription for a Monument in Crosthwaite Church, in the Vale of Keswick | 157 |

| To the Rev. Christopher Wordsworth, D.D., Master of Harrow School | 162 |

| 1844 | |

| “So fair, so sweet, withal so sensitive” | 164 |

| [x]On the projected Kendal and Windermere Railway | 166 |

| “Proud were ye, Mountains, when, in times of old” | 167 |

| At Furness Abbey | 168 |

| 1845 | |

| “Forth from a jutting ridge, around whose base” | 170 |

| The Westmoreland Girl | 172 |

| At Furness Abbey | 176 |

| “Yes! thou art fair, yet be not moved” | 176 |

| “What heavenly smiles! O Lady mine” | 177 |

| To a Lady | 177 |

| To the Pennsylvanians | 179 |

| “Young England—what is then become of Old” | 180 |

| 1846 | |

| Sonnet | 181 |

| “Where lies the truth? has Man, in wisdom’s creed” | 182 |

| To Lucca Giordano | 183 |

| “Who but is pleased to watch the moon on high” | 184 |

| Illustrated Books and Newspapers | 184 |

| Sonnet. To an Octogenarian | 185 |

| “I know an aged Man constrained to dwell” | 186 |

| “The unremitting voice of nightly streams” | 187 |

| “How beautiful the Queen of Night, on high” | 188 |

| On the Banks of a Rocky Stream | 188 |

| Ode. Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood | 189 |

| [xi]POEMS BY WILLIAM WORDSWORTH AND BY DOROTHY WORDSWORTH NOT INCLUDED IN THE EDITION OF 1849-50 |

|

| 1787 | |

| Sonnet, on seeing Miss Helen Maria Williams weep at a Tale of Distress | 209 |

| Lines written by William Wordsworth as a School Exercise at Hawkshead, Anno Ætatis 14 | 211 |

| 1792 (or earlier) | |

| “Sweet was the walk along the narrow lane” | 214 |

| “When Love was born of heavenly line” | 215 |

| The Convict | 217 |

| 1798 | |

| “The snow-tracks of my friends I see” | 219 |

| The Old Cumberland Beggar (MS. Variants, not inserted in Vol. I.) | 220 |

| 1800 | |

| Andrew Jones | 221 |

| “There is a shapeless crowd of unhewn stones” | 223 |

| 1802 | |

| “Among all lovely things my Love had been” | 231 |

| [xii]“Along the mazes of this song I go” | 233 |

| “The rains at length have ceas’d, the winds are still’d” | 233 |

| “Witness thou” | 234 |

| Wild-Fowl | 234 |

| Written in a Grotto | 234 |

| Home at Grasmere | 235 |

| “Shall he who gives his days to low pursuits” | 257 |

| 1803 | |

| “I find it written of Simonides” | 258 |

| 1804 | |

| “No whimsey of the purse is here” | 258 |

| 1805 | |

| “Peaceful our valley, fair and green” | 259 |

| “Ah! if I were a lady gay” | 262 |

| 1806 | |

| To the Evening Star over Grasmere Water, July 1806 | 263 |

| Michael Angelo in Reply to the Passage upon his Statue of Night sleeping | 263 |

| “Come, gentle Sleep, Death’s image tho’ thou art” | 264 |

| “Brook, that hast been my solace days and week” | 265 |

| Translation from Michael Angelo | 265 |

| 1808 | |

| [xiii]George and Sarah Green | 266 |

| 1818 | |

| “The Scottish Broom on Bird-nest brae” | 270 |

| Placard for a Poll bearing an old Shirt | 271 |

| “Critics, right honourable Bard, decree” | 271 |

| 1819 | |

| “Through Cumbrian wilds, in many a mountain cove” | 272 |

| “My Son! behold the tide already spent” | 273 |

| 1820 | |

| Author’s Voyage down the Rhine | 273 |

| 1822 | |

| “These vales were saddened with no common gloom” | 275 |

| Translation of Part of the First Book of the Æneid | 276 |

| 1823 | |

| “Arms and the Man I sing, the first who bore” | 281 |

| 1826 | |

| Lines addressed to Joanna H. from Gwerndwffnant in June 1826 | 282 |

| Holiday at Gwerndwffnant, May 1826 | 284 |

| Composed when a Probability existed of our being obliged to quit Rydal Mount as a Residence | 289 |

| [xiv]“I, whose pretty Voice you hear” | 295 |

| 1827 | |

| To my Niece Dora | 297 |

| 1829 | |

| “My Lord and Lady Darlington” | 298 |

| 1833 | |

| To the Utilitarians | 299 |

| 1835 | |

| “Throned in the Sun’s descending car” | 300 |

| “And oh! dear soother of the pensive breast” | 301 |

| 1836 | |

| “Said red-ribboned Evans” | 301 |

| 1837 | |

| On an Event in Col. Evans’s Redoubted Performances in Spain | 303 |

| 1838 | |

| “Wouldst thou be gathered to Christ’s chosen flock” | 303 |

| Protest against the Ballot, 1838 | 304 |

| “Said Secrecy to Cowardice and Fraud” | 304 |

| A Poet to his Grandchild | 305 |

| 1840 | |

| On a Portrait of I.F., painted by Margaret Gillies | 306 |

| To I.F. | 307 |

| [xv]“Oh Bounty without measure, while the Grace” | 308 |

| 1842 | |

| The Eagle and the Dove | 309 |

| Grace Darling | 310 |

| “When Severn’s sweeping flood had overthrown” | 314 |

| The Pillar of Trajan | 314 |

| 1846 | |

| “Deign, Sovereign Mistress! to accept a lay” | 319 |

| 1847 | |

| Ode, performed in the Senate-House, Cambridge, on the 6th of July 1847, at the First Commencement after the Installation of His Royal Highness the Prince Albert, Chancellor of the University | 320 |

| To Miss Sellon | 325 |

| “The worship of this Sabbath morn” | 325 |

| Bibliographies— | |

| I. Great Britain | 329 |

| II. America | 380 |

| III. France | 421 |

| Errata and Addenda List | 431 |

| Index to the Poems | 433 |

| Index to the First Lines | 451 |

The American Bibliography is almost entirely the work of Mrs. St. John of Ithaca, and is the result of laborious and careful critical research on her part. The French Bibliography is not so full. I have been assisted in it mainly by M. Legouis at Lyons, and by workers at the British Museum. I have also collected a German Bibliography, but it is in too incomplete a state for publication in its present form.

The English Bibliography is fuller than any of its predecessors; but there is no such thing as finality in such work, especially when an addition to the literature of the subject is made nearly every week. Many kind friends, and coadjutors, have assisted me in it, amongst whom I may mention Dr. Garnett of the British Museum, and very specially Mr. Tutin, of Hull, and also Mr. John J. Smith, St. Andrews, and Mr. Maclauchlan, Dundee. If I omit, either here or elsewhere, to record the assistance which I have received from any one, in my efforts to make this edition of Wordsworth as perfect as is possible at this stage of literary criticism and editorship, I sincerely regret it; but many of my correspondents have specially requested that no mention should be made of their names or their services.

In the Preface to the first volume of this edition there was an unfortunate omission. In returning the final proofs to press, I accidentally transmitted an uncorrected one, in which two names did not appear. They were those of Mr. Thomas Hutchinson, Dublin, and Mr. S. C. Hill, of Hughli College, Bengal. The former kindly revised most of the sheets of Volumes I. and II., and corrected errors, besides making other valuable suggestions and additions. When his own Clarendon Press edition of Wordsworth was being prepared for press, Mr. Hutchinson asked permission to incorporate in it materials which were not afterwards inserted. This I granted cordially, as a similar permission had been given to Professor Dowden for his Aldine edition. The unfortunate omission of Mr. Hutchinson’s name was not discovered by me till after the issue of volumes I. and II. (which appeared simultaneously), and it was first brought under my notice by Mr. Hutchinson’s own letters to the newspapers. My debt to Mr. Hutchinson is great; and, although I have already thanked him for the services which he has rendered to the world in connection with Wordsworthian literature, I may perhaps be allowed to repeat the acknowledgment now. The revised sheets of Vols. I. and II. of this edition were, however, submitted to others at the same time that they were sent to Mr. Hutchinson; more especially to the late Mr. Dykes Campbell, and on his death to Mr. Belinfante, and then to the late Mr. Kinghorn, all of whom were engaged by my publishers to assist in the work entrusted to me. They “turned on the microscope” on my own work, and Mr. Hutchinson’s; and to them I have been indebted in many ways.

Mr. Hill’s services, in tracing the sources of numerous quotations from other poets which occur in Wordsworth’s text, have been great. He sent me his discoveries, unsolicited, and I wish to express very cordially my indebtedness to him. To discover some of these quotations—there are several hundreds of them—cost me much labour, before I had the pleasure of hearing from, or knowing, Mr. Hill; and his assistance in this matter has been greater than that of any other person. It will be seen that I have failed—after much study and extensive correspondence—to discover them all.

In addition to actual quotations—indicated by Wordsworth by inverted commas in his poems—to trace parallel passages from other poets, or phrases which may have suggested to him what he recast and glorified, has seemed to me work not unworthy of accomplishment. At the same time, and in the same connection, to discover the somewhat similar debts of later poets to Wordsworth, and to indicate this here and there in footnotes, may not be wholly useless to posterity.

My obligations to my friend, Mr. Dykes Campbell, are greater than I can adequately express. He supplied me with much material, drawn from many quarters; and, although he did not always mention his sources, I had implicit confidence in him, both as a literary man and a friend. After his death, through the kindness of Mrs. Campbell, I examined some MS. volumes of Wordsworthiana written by him, which were of much use to me.

Some of these were from unknown sources, which I should perhaps have traced out before making use of them, but, in all my Wordsworth work, I have acted from first to last on the legal opinion of a distinguished[xx] Judge, that the heir of the writer of literary work could alone authorise its subsequent publication; and, since the heirs of the Poet had kindly given me permission to collect and publish his works, I did so, with a view to the benefit of posterity.

Some of Mr. Campbell’s material was derived from MSS. now in the possession of Mr. T. Norton Longman, and I have to express my sincere regret that in the earlier volumes I copied from Mr. Campbell’s transcripts of these MSS.—which were lent to him on the condition that no public use should be made of them without Mr. Longman’s permission—some variations of the text, without mentioning the source whence they were derived.

I was unaware that these MSS. were lent to Mr. Campbell with the condition attached, and regret very much that I am unable to trust my memory to indicate now what variations of text I have quoted from them. But I may add that Mr. Longman is about to publish a work which will enable Wordsworth students to become practically acquainted with the contents of his MSS.

In reference to the poems not published by Wordsworth or his sister during their lifetime, I have included in this volume not only fugitive pieces printed in Magazines and elsewhere, but also those which have been since recovered from numerous manuscript sources. They are of varying merit. It would be interesting to know, and to record in every instance, where these manuscripts now are; but this is impossible. In many cases the manuscripts have recently changed ownership. I have obtained a sight of many of them, and have been granted permission to transcribe them, from[xxi] the fortunate possessors of large autograph collections, and also from dealers in autographs; but, after the sale of manuscripts at public auction-rooms, it is, as a rule, impossible to trace them.

In many cases the MS. variants which have been published in previous volumes occur in copies of the poems, transcribed by the Wordsworth household in private letters to friends. I have occasionally indicated this in footnotes; but, to have done so always would have disfigured the pages, and frequently the notes would have been longer than the text. To trace the present possessors of the MSS. would be well-nigh impossible. It is perhaps worth mentioning that in several cases Wordsworth entered as “misprints” in future editions, what some of his editors have considered “new readings.” E.g. in The Excursion, book ix. l. 679, “wild” demeanour, instead of “mild” demeanour.

On Nov. 4, 1893, Mr. Aubrey de Vere wrote to me—

“I earnestly hope that, in your ‘monumental edition,’ you will restore the Ode, Intimations of Immortality, to the place which Wordsworth always assigned to it, that of the High Altar of his poetic Cathedral; remitting Quillinan’s laureate Ode on an unworthy, because ‘occasional,’ subject to an Appendix, as a work that at the time of publication was attributed to Wordsworth, but was written by another, though it probably was seen by him, and had a line or two of his in it, and corrections by him.

“This is certainly the truth; and I should think that he probably himself told all that truth to the officials, when transmitting the Ode; but that they concealed the circumstance; and that Wordsworth, then profoundly depressed in spirits, gave no more thought to the subject, and soon forgot all about it.…

“Yours very sincerely,

“Aubrey de Vere.”

It was in compliance with Mr. Aubrey de Vere’s request that, in this edition, I departed, in a single instance, from the chronological arrangement of the poems.

It may not be too trivial a detail to mention that I gladly gave permission to other editors of Wordsworth to make use of any of the material which I discovered, and brought together, in former editions; e.g. to Mr. George, in Boston, for his edition of The Prelude (in which, if the reader, or critic, compares my original edition with his notes, he will see what Mr. George has done); and to Professor Dowden, Trinity College, Dublin, for his most admirable Aldine edition. For the latter—which will always hold a high place in Wordsworth literature—I placed everything asked from me at the disposal of Mr. Dowden.

While these sheets are passing through the press, Dr. Garnett, of the British Museum—one of the kindest and ablest of bibliographers—has forwarded to me a contribution, previously sent by him to The Academy, and printed in its issue of January 2, 1897.

I have no means of knowing—or of ultimately discovering—whether that sonnet, printed as Wordsworth’s, is really his. Dr. Garnett says, in his letter to me, “The verses were undoubtedly in Wordsworth’s hand”;[xxiii] and, he adds, “I think they should be preserved, because they are Wordsworth’s, and as an additional proof of his regard for Camoens, whom he enumerates elsewhere among great sonnet-writers. I have added a version of the quatrains, that the piece may be complete. From the character of the handwriting, the lines would seem to have been written down in old age; and I am not quite certain of the word which I have transcribed as ‘Austral.’”

WORDSWORTH’S POETICAL WORKS

Composed 1834.—Published 1835

[This Portrait has hung for many years in our principal sitting-room, and represents J. Q.[1] as she was when a girl. The picture, though it is somewhat thinly painted, has much merit in tone and general effect: it is chiefly valuable, however, from the sentiment that pervades it. The anecdote of the saying of the monk in sight of Titian’s picture was told in this house by Mr. Wilkie, and was, I believe, first communicated to the public in this poem, the former portion of which I was composing at the time. Southey heard the story from Miss Hutchinson, and transferred it to the Doctor; but it is not easy to explain how my friend Mr. Rogers, in a note subsequently added to his Italy, was led to speak of the same remarkable words having many years before been spoken in his hearing by a monk or priest in front of a picture of the Last Supper, placed over a Refectory-table in a convent at Padua.—I.F.]

One of the “Poems of Sentiment and Reflection.”—Ed.

[1] Jemima Quillinan, the eldest daughter of Edward Quillinan, Wordsworth’s future son-in-law. The portrait was taken when she was a school-girl, and while her father resided at Oporto.—Ed.

[2] Wilkie. See the Fenwick note.—Ed.

[3] 1837.

[4] “When Wilkie was in the Escurial, looking at Titian’s famous picture of the Last Supper, in the Refectory there, an old Jeronymite said to him: ‘I have sate daily in sight of that picture for now nearly three score years; during that time my companions have dropt off, one after another—all who were my seniors, all who were my contemporaries, and many, or most of those who were younger than myself; more than one generation has passed away, and there the figures in the picture have remained unchanged! I look at them till I sometimes think that they are the realities, and we but shadows!’

I wish I could record the name of the monk by whom that natural feeling was so feelingly and strikingly expressed.

says the author of the tragedy of Nero, whose name also I could wish had been forthcoming; and the classical reader will remember the lines of Sophocles:

These are reflections which should make us think

(Southey, The Doctor, vol. iii. p. 235.)—Ed.

[5] 1837.

[6] The pile of buildings, composing the palace and convent of San Lorenzo, has, in common usage, lost its proper name in that of the Escurial, a village at the foot of the hill upon which the splendid edifice, built by Philip the Second, stands. It need scarcely be added, that Wilkie is the painter alluded to.—W.W. 1835.

Composed 1834.—Published 1835.

One of the “Poems of Sentiment and Reflection.”—Ed.

[7] In the class entitled “Musings,” in Mr. Southey’s Minor Poems, is one upon his own miniature picture, taken in childhood, and another upon a landscape painted by Gaspar Poussin. It is possible that every word of the above verses, though similar in subject, might have been written had the author been unacquainted with those beautiful effusions of poetic sentiment. But, for his own satisfaction, he must be allowed thus publicly to acknowledge the pleasure those two poems of his Friend have given him, and the grateful influence they have upon his mind as often as he reads them, or thinks of them.—W.W. 1835.

Composed 1834.—Published 1835

[This quatrain was extempore on observing this image, as I had often done, on the lawn of Rydal Mount. It was first written down in the Album of my God-daughter, Rotha Quillinan.—I.F.]

In 1837 this was one of the “Inscriptions.” In 1845 it was transferred to the “Miscellaneous Poems.”—Ed.

[8] The original title (1835) was “Written in an Album.” In 1837 it was “Written in the Album of a Child.” In 1845 the title was reconstructed as above.

[9] 1845.

Composed 1834.—Published 1835

[This is a faithful picture of that amiable Lady, as she then was. The youthfulness of figure and demeanour and habits, which she retained in almost unprecedented degree, departed a very few years after, and she died without violent disease by gradual decay before she reached the period of old age.—I.F.]

This was placed, in 1845, among the “Miscellaneous Poems.”—Ed.

[11] 1837.

[12] The Lowther stream passes the Castle, and joins the Eamont below Brougham Hall, near Penrith.—Ed.

[13] 1837.

[15] Compare September, 1819, and Upon the Same Occasion, vol. vi. pp. 201, 202, especially the lines in the latter—

Ed.

[16] 1837.

Two Evening Voluntaries, two Elegies (on the deaths of Charles Lamb and James Hogg), the lines on the Bird of Paradise, and a few sonnets, make up the poems belonging to the year 1835.—Ed.

Composed 1835 (or earlier).—Published 1835

[In the month of January,—when Dora and I were walking from Town-end, Grasmere, across the Vale, snow being on the ground, she espied, in the thick though leafless hedge, a bird’s nest half-filled with snow. Out of this comfortless appearance arose this Sonnet, which was, in fact, written without the least reference to any individual object, but merely to prove to myself that I could, if I thought fit, write in a strain that Poets have been fond of. On the 14th of February in the same year, my daughter, in a sportive mood, sent it as a Valentine, under a fictitious name, to her cousin C.W.—I.F.]

One of the “Miscellaneous Sonnets.”—Ed.

Composed 1835.—Published 1837

One of the “Evening Voluntaries.”—Ed.

[18] Compare—

in the lines Written in a Grotto, p. 235.—Ed.

Composed 1835.—Published 1837

One of the “Evening Voluntaries.”—Ed.

[19] Compare The Triad, vol. vii. p. 181.—Ed.

[21] See a fragment of ten lines, which was written by Wordsworth in MS. after the above, in a copy of his poems. They are printed in the Appendix to this volume.—Ed.

[Light will be thrown upon the tragic circumstance alluded to in this poem when, after the death of Charles Lamb’s Sister, his biographer, Mr. Sergeant Talfourd, shall be at liberty to relate particulars which could not, at the time his Memoir was written, be given to the public. Mary Lamb was ten years older than her brother, and has survived him as long a time. Were I to give way to my own feelings, I should dwell not only on her genius and intellectual powers, but upon the delicacy and refinement of manner which she maintained inviolable under most trying circumstances. She was loved and honoured by all her brother’s friends; and others, some of them strange characters, whom his philanthropic peculiarities induced him to[18] countenance. The death of C. Lamb himself was doubtless hastened by his sorrow for that of Coleridge, to whom he had been attached from the time of their being school-fellows at Christ’s Hospital. Lamb was a good Latin scholar, and probably would have gone to college upon one of the school foundations but for the impediment in his speech. Had such been his lot, he would most likely have been preserved from the indulgences of social humours and fancies which were often injurious to himself, and causes of severe regret to his friends, without really benefiting the object of his misapplied kindness.—I.F.]

In the edition of 1837, these lines had no title. They were printed privately,—before their first appearance in that edition,—as a small pamphlet of seven pages without title or heading. A copy will be found in the fifth volume of the collection of pamphlets, forming part of the library bequeathed by the late Mr. John Forster to the South Kensington Museum. There are several readings to be found only in this privately-printed edition. The poem was placed among the “Epitaphs and Elegiac Pieces.”—Ed.

Composed November 19, 1835.—Published 1837

[22] 1837.

[23] Charles Lamb died December 27, 1834, and was buried in Edmonton Churchyard, in a spot selected by himself.—Ed.

[24] This way of indicating the name of my lamented friend has been found fault with, perhaps rightly so; but I may say in justification of the double sense of the word, that similar allusions are not uncommon in epitaphs. One of the best in our language in verse, I ever read, was upon a person who bore the name of Palmer†; and the course of the thought, throughout, turned upon the Life of the Departed, considered as a pilgrimage. Nor can I think that the objection in the present case will have much force with any one who remembers Charles Lamb’s beautiful sonnet addressed to his own name, and ending—

W. W. 1837.

† 1840. Pilgrim; 1837.

Professor Henry Reed, in his edition of 1837, added the following note to Wordsworth’s. “In Hierologus, a Church Tour through England and Wales, I have met with an epitaph which is probably the one alluded to above … a Kentish epitaph on one Palmer:

The above is Professor Reed’s note. The following is an exact copy of the epitaph:—

Ed.

[25] Compare Talfourd’s Final Memorials of Charles Lamb, passim.—Ed.

[26] 1837.

[27] 1837.

Professor Dowden quotes, from “a slip of MS. in the poet’s hand-writing,” the following variation of these lines—

Ed.

[28] Lamb’s indifference to the country “was a sort of ‘mock apparel,’ in which it was his humour at times to invest himself.” (H. N. Coleridge, Supplement to the Biographia Literaria, p. 333.)—Ed.

[29] 1837.

[30] 1837.

[31] 1837.

[32] 1837.

[33] 1837.

[34] Compare the testimony borne to Mary Lamb by Mr. Procter (Barry Cornwall), and by Henry Crabb Robinson.—Ed.

[35] 1837.

Wordsworth originally meant to write an epitaph on Charles Lamb, but his verse grew into an elegy of some length. A reference to the circumstance of its “composition” will be found in one of his letters, in a later volume.—Ed.

Composed 1835.—Published 1835

[These verses were written extempore, immediately after reading a notice of the Ettrick Shepherd’s death, in the Newcastle paper, to the Editor of which I sent a copy for publication. The persons lamented in these verses were all either of my friends or acquaintance. In Lockhart’s Life of Sir Walter Scott, an account is given of my first meeting with him in 1803. How the Ettrick Shepherd and I became known to each other has already been mentioned in these notes. He was undoubtedly a man of original genius, but of coarse manners and low and offensive opinions. Of Coleridge and Lamb I need not speak here. Crabbe I have met in London at Mr. Rogers’s, but more frequently and favourably at Mr. Hoare’s upon Hampstead Heath. Every spring he used to pay that family a visit of some length, and was upon terms of intimate friendship with Mrs. Hoare, and still more with her daughter-in-law, who has a large collection of his letters addressed to herself. After the Poet’s decease, application was made to her to give up these letters to his biographer, that they, or at least part of them, might be given to the public. She hesitated to comply, and asked my opinion on the subject. “By no means,” was my answer, grounded not upon any objection there might be to publishing a selection from these letters, but from an aversion I have always felt to meet idle curiosity by calling[25] back the recently departed to become the object of trivial and familiar gossip. Crabbe obviously for the most part preferred the company of women to that of men, for this among other reasons, that he did not like to be put upon the stretch in general conversation: accordingly in miscellaneous society his talk was so much below what might have been expected from a man so deservedly celebrated, that to me it seemed trifling. It must upon other occasions have been of a different character, as I found in our rambles together on Hampstead Heath, and not so much from a readiness to communicate his knowledge of life and manners as of natural history in all its branches. His mind was inquisitive, and he seems to have taken refuge from the remembrance of the distresses he had gone through, in these studies and the employments to which they led. Moreover, such contemplations might tend profitably to counterbalance the painful truths which he had collected from his intercourse with mankind. Had I been more intimate with him, I should have ventured to touch upon his office as a minister of the Gospel, and how far his heart and soul were in it so as to make him a zealous and diligent labourer: in poetry, though he wrote much as we all know, he assuredly was not so. I happened once to speak of pains as necessary to produce merit of a certain kind which I highly valued: his observation was—“It is not worth while.” You are quite right, thought I, if the labour encroaches upon the time due to teach truth as a steward of the mysteries of God: if there be cause to fear that, write less: but, if poetry is to be produced at all, make what you do produce as good as you can. Mr. Rogers once told me that he expressed his regret to Crabbe that he wrote in his later works so much less correctly than in his earlier. “Yes,” replied he, “but then I had a reputation to make; now I can afford to relax.” Whether it was from a modest estimate of his own qualifications, or from causes less creditable, his motives for writing verse and his hopes and aims were not so high as is to be desired. After being silent for more than twenty years, he again applied himself to poetry, upon the spur of applause he received from the periodical publications of the day, as he himself tells us in one of his prefaces. Is it not to be lamented that a man who was so conversant with permanent truth, and whose writings are so valuable an acquisition to our country’s literature, should have required an impulse from such a quarter? Mrs. Hemans was unfortunate as a poetess in being obliged by circumstances to write for money, and that so[26] frequently and so much, that she was compelled to look out for subjects wherever she could find them, and to write as expeditiously as possible. As a woman, she was to a considerable degree a spoilt child of the world. She had been early in life distinguished for talent, and poems of hers were published while she was a girl. She had also been handsome in her youth, but her education had been most unfortunate. She was totally ignorant of housewifery, and could as easily have managed the spear of Minerva as her needle. It was from observing these deficiencies, that, one day while she was under my roof, I purposely directed her attention to household economy, and told her I had purchased Scales which I intended to present to a young lady as a wedding present; pointed out their utility (for her especial benefit) and said that no ménage ought to be without them. Mrs. Hemans, not in the least suspecting my drift, reported this saying, in a letter to a friend at the time, as a proof of my simplicity. Being disposed to make large allowances for the faults of her education and the circumstances in which she was placed, I felt most kindly disposed towards her, and took her part upon all occasions, and I was not a little affected by learning that after she withdrew to Ireland, a long and severe sickness raised her spirit as it depressed her body. This I heard from her most intimate friends, and there is striking evidence of it in a poem written and published not long before her death. These notices of Mrs. Hemans would be very unsatisfactory to her intimate friends, as indeed they are to myself, not so much for what is said, but what for brevity’s sake is left unsaid. Let it suffice to add, there was much sympathy between us, and, if opportunity had been allowed me to see more of her, I should have loved and valued her accordingly; as it is, I remember her with true affection for her amiable qualities, and, above all, for her delicate and irreproachable conduct during her long separation from an unfeeling husband, whom she had been led to marry from the romantic notions of inexperienced youth. Upon this husband I never heard her cast the least reproach, nor did I ever hear her even name him, though she did not wholly forbear to touch upon her domestic position; but never so that any fault could be found with her manner of adverting to it. —I.F.]

This first appeared in The Athenæum, December 12, 1835, and in the edition of 1837 it was included among the “Epitaphs and Elegiac Pieces.”—Ed.

[36] Compare Yarrow Visited (September, 1814), vol. vi. p. 35.—Ed.

[37] Compare Yarrow Revisited (1831), vol. vii. p. 278.—Ed.

[38] Scott died at Abbotsford, on the 21st September 1832, and was buried in Dryburgh Abbey.—Ed.

[39] Hogg died at Altrive, on the 21st November 1835.—Ed.

[40] Coleridge died at Highgate, on the 25th July 1834.—Ed.

[41] Compare the Stanzas written in my Pocket Copy of Thomson’s “Castle of Indolence” (vol. ii. p. 307)—

Ed.

[42] Lamb died in London, on the 27th December 1834.—Ed.

[43] “This expression is borrowed from a sonnet by Mr. G. Bell, the author of a small volume of poems lately printed at Penrith. Speaking of Skiddaw he says—

(Henry Reed, 1837.)—Ed.

[44] 1845.

[45] George Crabbe died at Trowbridge, Wiltshire, on the 3rd of February 1832.—Ed.

[46] Felicia Hemans died 16th May 1835.—Ed.

Composed 1835.—Published 1836

[I cannot forbear to record that the last seven lines of this Poem were composed in bed during the night of the day on which my sister Sara Hutchinson died about 6 P.M., and it was the thought of her innocent and beautiful life that, through faith, prompted the words——

The reader will find two poems on pictures of this bird among my Poems. I will here observe that in a far greater number of instances than have been mentioned in these notes one poem has, as in this case, grown out of another, either because I felt the subject had been inadequately treated, or that the thoughts and images suggested in course of composition have been such as I found interfered with the unity indispensable to every work of art, however humble in character.—I.F.]

One of the “Poems of Sentiment and Reflection.”—Ed.

[48] Compare, in Robert Browning’s poem on Guercino’s picture of The Guardian-Angel at Fano——

Ed.

Composed 1835.—Published 1835

One of the “Miscellaneous Sonnets.”—Ed.

[49] Compare The Excursion (book iii. l. 649), and the sonnet (vol. vi. p. 72) beginning——

Ed.

Composed 1835.—Published 1835

[Suggested on the road between Preston and Lancaster where it first gives a view of the Lake country, and composed on the same day, on the roof of the coach.—I.F.]

One of the “Miscellaneous Sonnets.”—Ed.

[50] 1837.

Composed 1835.—Published 1835

[The fate of this poor Dove, as described, was told to me at Brinsop Court, by the young lady to whom I have given the name of Lesbia.—I.F.]

One of the “Miscellaneous Sonnets.”—Ed.

[51] Miss Loveday Walker, daughter of the Rector of Brinsop. See the Fenwick note to the next sonnet.—Ed.

Composed 1835.—Published 1835

[My attention to these antiquities was directed by Mr. Walker, son to the itinerant Eidouranian Philosopher. The beautiful pavement was discovered within a few yards of the front door of his parsonage, and appeared from the site (in full view of several hills upon which there had formerly been Roman encampments) as if it might have been the villa of the commander of the forces, at least such was Mr. Walker’s conjecture.—I.F.]

One of the “Miscellaneous Sonnets.”—Ed.

Composed 1835.—Published 1835

[Written on a journey from Brinsop Court, Herefordshire.—I.F.]

One of the “Miscellaneous Sonnets.”—Ed.

[52] The Ledbury bells are easily audible on the Malvern hills.—Ed.

Published 1835

[This lady was named Carleton; she, along with a sister, was brought up in the neighbourhood of Ambleside. The epitaph, a part of it at least, is in the church at Bromsgrove, where she resided after her marriage.—I.F.]

One of the “Epitaphs and Elegiac Pieces.”—Ed.

[53] 1837.

In the edition of 1835 the title was “Epitaph.”

[54] 1837.

Composed 1835.—Published 1838

[The sad condition of poor Mrs. Southey[55] put me upon writing this. It has afforded comfort to many persons whose friends have been similarly affected.—I.F.]

One of the “Miscellaneous Sonnets.”—Ed.

[55] Mrs. Southey died 16th November 1837. She had long been an invalid. See Southey’s Life and Correspondence, vol. vi. p. 347.—Ed.

[56] 1842.

[57] Compare a remark of Wordsworth’s that he never saw those with mind unhinged, but he thought of the words, “Life hid in God.” It is a curious oriental belief that idiots are in closer communion with the Infinite than the sane are.—Ed.

So far as can be ascertained, only one sonnet was written by Wordsworth in 1836. The verses To a Redbreast, by his sister-in-law, Sarah Hutchinson, may however be placed alongside of the sonnet addressed to her.—Ed.

Composed 1836.—Published 1837.

One of the “Miscellaneous Sonnets.”—Ed.

[58] Sarah Hutchinson—Mrs. Wordsworth’s sister—died at Rydal on the 23rd June 1836. It was after her that the poet named one of the two “heath-clad rocks” referred to in the “Poems on the naming of Places,” and which he called respectively “Mary-Point” and “Sarah-Point.” In 1827 he inscribed to her the sonnet beginning—

and the lines she wrote To a Redbreast, beginning—

were published among Wordsworth’s own poems.

The sonnet written in 1806, beginning—

was, Wordsworth tells us, a great favourite with S. H. He adds, “When I saw her lying in death I could not resist the impulse to compose the sonnet that follows it.” (See vol. iv. p. 46.)

In a letter to Southey (unpublished), Wordsworth refers to her death, and adds: “I saw her within an hour after her decease, in the silence and peace of death, with as heavenly an expression on her countenance as ever human creature had. Surely there is food for faith in these appearances: for myself, I can say that I have passed a wakeful night, more in joy than in sorrow, with that blessed face before my eyes perpetually as I lay in bed.”

Published 1842

[Almost the only verses by our lamented sister Sara Hutchinson.—I.F.]

One of the “Miscellaneous Poems.”—Ed.

The poems belonging to the year 1837 include the “Memorials of a Tour in Italy” with Henry Crabb Robinson in that year, and one or two additional sonnets.—Ed.

Published 1837

One of the “Epitaphs and Elegiac Pieces.”—Ed.

[59] This refers to the poet’s son Thomas, who died December 1, 1812. He was buried in Grasmere churchyard, beside his sister Catherine; and Wordsworth placed these lines upon his tombstone. They may have been written much earlier than 1836, probably in 1813, but it is impossible to ascertain the date, and they were not published till 1837.—Ed.

Composed 1837.—Published 1842

[During my whole life I had felt a strong desire to visit Rome and the other celebrated cities and regions of Italy, but[40] did not think myself justified in incurring the necessary expense till I received from Mr. Moxon, the publisher of a large edition of my poems, a sum sufficient to enable me to gratify my wish without encroaching upon what I considered due to my family. My excellent friend H.C. Robinson readily consented to accompany me, and in March 1837, we set off from London, to which we returned in August, earlier than my companion wished or I should myself have desired had I been, like him, a bachelor. These Memorials of that tour touch upon but a very few of the places and objects that interested me, and, in what they do advert to, are for the most part much slighter than I could wish. More particularly do I regret that there is no notice in them of the South of France, nor of the Roman antiquities abounding in that district, especially of the Pont de Degard, which, together with its situation, impressed me full as much as any remains of Roman architecture to be found in Italy. Then there was Vaucluse, with its Fountain, its Petrarch, its rocks of all seasons, its small plots of lawn in their first vernal freshness, and the blossoms of the peach and other trees embellishing the scene on every side. The beauty of the stream also called forcibly for the expression of sympathy from one who, from his childhood, had studied the brooks and torrents of his native mountains. Between two and three hours did I run about climbing the steep and rugged crags from whose base the water of Vaucluse breaks forth. “Has Laura’s Lover,” often said I to myself, “ever sat down upon this stone? or has his foot ever pressed that turf?” Some, especially of the female sex, would have felt sure of it: my answer was (impute it to my years) “I fear, not.” Is it not in fact obvious that many of his love verses must have flowed, I do not say from a wish to display his own talent, but from a habit of exercising his intellect in that way rather than from an impulse of his heart? It is otherwise with his Lyrical poems, and particularly with the one upon the degradation of his country: there he pours out his reproaches, lamentations, and aspirations like an ardent and sincere patriot. But enough: it is time to turn to my own effusions such as they are.—I.F.]

[60] The following is the Itinerary of the Italian Tour of 1837, supplied by Mr. Henry Crabb Robinson. (See Memoirs of Wordsworth, vol. ii. pp. 316, 317.) The spelling of the names of places is Robinson’s.

[61] 1845.

The Tour of which the following Poems are very inadequate remembrances was shortened by report, too well founded, of the prevalence of Cholera at Naples. To make some amends for what was reluctantly left unseen in the South of Italy, we visited the Tuscan Sanctuaries among the Apennines, and the principal Italian Lakes among the Alps. Neither of those lakes, nor of Venice, is there any notice in these Poems, chiefly because I have touched upon them elsewhere. See, in particular, Descriptive Sketches, “Memorials of a Tour on the Continent in 1820,” and a Sonnet upon the extinction of the Venetian Republic.—W.W.

April, 1837

His, Sir Walter Scott’s, eye, did in fact kindle at them, for the lines, “Places forsaken now” and the two that follow, were adopted from a poem of mine which nearly forty years ago was in part read to him, and he never forgot them.

Sir Humphry Davy was with us at the time. We had ascended from Patterdale, and I could not but admire the vigour with which Scott scrambled along that horn of the mountain called “Striding Edge.” Our progress was necessarily slow, and was beguiled by Scott’s telling many stories and amusing anecdotes, as was his custom. Sir H. Davy would have probably been better pleased if other topics had occasionally been interspersed, and some discussion entered upon: at all events he did not remain with us long at the top of the mountain, but left us to find our way down its steep side together into the Vale of Grasmere, where, at my cottage, Mrs. Scott was to meet us at dinner.

See among these notes the one on Yarrow Revisited.

This, though introduced here, I did not know till it was told me at Rome by Miss Mackenzie of Seaforth, a lady whose friendly attentions during my residence at Rome I have gratefully acknowledged with expressions of sincere regret that she is no more. Miss M. told me that she accompanied Sir Walter to the Janicular Mount, and, after showing him the grave of Tasso in the church upon the top, and a mural monument, there erected to his memory, they left the church and stood together on the brow of the hill overlooking the City of Rome: his daughter Anne was with them, and she, naturally desirous, for the sake of Miss Mackenzie especially, to have some expression of pleasure from her father, half reproached him for showing nothing of that kind either by his looks or voice: “How can I,” replied he,[44] “having only one leg to stand upon, and that in extreme pain!” so that the prophecy was more than fulfilled.

We took boat near the lighthouse at the point of the right horn of the bay which makes a sort of natural port for Genoa; but the wind was high, and the waves long and rough, so that I did not feel quite recompensed by the view of the city, splendid as it was, for the danger apparently incurred. The boatman (I had only one) encouraged me saying we were quite safe, but I was not a little glad when we gained the shore, though Shelley and Byron—one of them at least, who seemed to have courted agitation from any quarter—would have probably rejoiced in such a situation: more than once I believe were they both in extreme danger even on the lake of Geneva. Every man, however, has his fears of some kind or other; and no doubt they had theirs: of all men whom I have ever known, Coleridge had the most of passive courage in bodily peril, but no one was so easily cowed when moral firmness was required in miscellaneous conversation or in the daily intercourse of social life.

There is not a single bay along this beautiful coast that might not raise in a traveller a wish to take up his abode there, each as it succeeds seems more inviting than the other; but the desolated convent on the cliff in the bay of Savona struck my fancy most; and had I, for the sake of my own health or that of a dear friend, or any other cause, been desirous of a residence abroad, I should have let my thoughts loose upon a scheme of turning some part of this building into a habitation provided as far as might be with English comforts. There is close by it a row or avenue, I forget which, of tall cypresses. I could not forbear saying to myself—“What a sweet family walk, or one for lonely musings, would be found under the shade!” but there, probably, the trees remained little noticed and seldom enjoyed.

The broom is a great ornament through the months of March and April to the vales and hills of the Apennines, in the wild[45] parts of which it blows in the utmost profusion, and of course successively at different elevations as the season advances. It surpasses ours in beauty and fragrance,[62] but, speaking from my own limited observations only, I cannot affirm the same of several of their wild spring flowers, the primroses in particular, which I saw not unfrequently but thinly scattered and languishing compared to ours.

The note at the end of this poem, upon the Oxford movement, was entrusted to my friend, Mr. Frederick Faber.[63] I told him what I wished to be said, and begged that, as he was intimately acquainted with several of the Leaders of it, he would express my thought in the way least likely to be taken amiss by them. Much of the work they are undertaking was grievously wanted, and God grant their endeavours may continue to prosper as they have done.—I.F.]

[62] Wordsworth himself, his nephew tells us, had no sense of smell (see the Memoirs, by his nephew Christopher, vol. ii. p. 322).—Ed.

[63] Afterwards Father Faber, priest of the Oratory of St. Philip Neri.—Ed.

[64] Monte Amiata,—Ed.

[65] On the old high road from Siena to Rome.—Ed.

[66] The mountain between Rydal Head and Helvellyn.—Ed.

[67] Seat Sandal is the mountain between Tongue Ghyll and Grisedale Tarn on the south and east, and the Dunmail Raise road on the west.—Ed.

[68] Compare The Eclipse of the Sun, l. 78, in “Memorials of a Tour on the Continent in 1820” (vol. vi. p. 345).—Ed.

[69] Keppelcove, Nethermost cove, and the cove in which Red Tarn lies bounded by the “skeleton arms” of Striding Edge and Swirrel Edge. Compare Fidelity, l. 17, vol. iii. p. 45—

Ed.

[70] Descending to Ullswater from Helvellyn, Greenside Fell and Mines are passed.—Ed.

[71] The Glenridding Screes are bold rocks on the left as you descend Helvellyn to Patterdale.—Ed.

[72] Glencoign is an offshoot of the Patterdale valley between Glenridding and Goldbarrow.—Ed.

[73] 1845.

[74] See the Fenwick note.—Ed.

[75] These words were quoted to me from Yarrow Unvisited, by Sir Walter Scott, when I visited him at Abbotsford, a day or two before his departure for Italy: and the affecting condition in which he was when he looked upon Rome from the Janicular Mount, was reported to me by a lady who had the honour of conducting him thither.—W.W. 1842. See also the Fenwick note to this poem, and compare Lockhart’s Memoirs of the Life of Sir Walter Scott (chapter lxxx. vol. x. p. 104).—Ed.

[76] The Janicular Mount.—Ed.

[77] See the Fenwick note prefixed to this poem.—Ed.

[78] He was then sixty-seven years of age.—Ed.

[79] See the Fenwick note.—Ed.

[80] The Campo Santo, or Burial Ground, founded by Archbishop Ubaldo (1188-1200).—Ed.

[81] “There are forty-three flat arcades, resting on forty-four pilasters.… In the interior there is a spacious hall, the open round-arched windows of which, with their beautiful tracery, sixty-two in number, look out upon a green quadrangle.… The walls are covered with frescoes by the Tuscan School of the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries, below which is a collection of Roman, Etruscan, and mediaeval sculptures.… The tombstones of persons interred here form the pavement.” (Baedeker’s Northern Italy, p. 324.)—Ed.

[82] Ubaldo conveyed hither fifty-three ship-loads of earth from Mount Calvary, in the Holy Land, in order that the dead might repose in holy ground.—Ed.

[83] The Baptistery in Pisa was begun in 1153 by Diotisalvi, and completed in 1278. It is a circular structure, covered by a conical dome, 190 feet high.—Ed.

[84] The Cathedral of Pisa is a basilica, built in 1063, in the Tuscan style, and has an elliptical dome.—Ed.

[85] The Campanile, or Clock-Tower, rises in eight stories to the height of 179 feet, and (from its oblique position) is known as the Leaning-Tower.—Ed.

[86] 1845.

[87] See the Fenwick note to this poem. Savona is a town on the Gulf of Genoa, capital of the Montenotte Department under Napoleon.—Ed.

[88] The theatre in Savona is dedicated to Chiabrera, who was a native of the place.—Ed.

[89] If any English reader should be desirous of knowing how far I am justified in thus describing the epitaphs of Chiabrera, he will find translated specimens of them in this Volume, under the head of “Epitaphs and Elegiac Pieces.”—W.W. 1842.

[90] Tusculum was the birthplace of the elder Cato, and the residence of Cicero.—Ed.

[91] “Satis beatus unicis Sabinis.” Odes, ii. 18, 14.—Ed.

[92] See Horace, Odes, iii. 13.—Ed.

[93] See Horace, Epistles, i. 10, 49—

Vacuna was a Sabine divinity. She had a sanctuary near Horace’s Villa. (Compare Pliny, Nat. Hist. iii. 42, 47.) A traveller in Italy writes: “Following a path along the brink of the torrent Digentia, we passed a towering rock, on which once stood Vacuna’s shrine.” See also Ovid, Fasti, vi. 307.—Ed.

[94] The Bay of Naples. Neapolis (the new city) received its ancient name of Parthenope from one of the Sirens, whose body was said to have been washed ashore in that bay. Sil. 12, 33.—Ed.

[95] See Georgics, iv. 564.—Ed.

[96] Virgil died at Brundusium, but his remains were carried to his favourite residence, Naples, and were buried by the side of the road leading to Puteoli—the Via Puteolana. His tomb is still pointed out near Posilipo,—close to the sea, and about half way from Naples to Puteoli, the Scuola di Virgilio.

“The monument, now called the tomb of Virgil, is not on the road which passes through the tunnel of Posilipo; but if the Via Puteolana ascended the hill of Posilipo, as it may have done, the situation of the monument would agree very well with the description of Donatus.” (George Long, in Smith’s Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography.)

The inscription said to have been placed on the tomb was as follows:—

Ed.

[97] The catacombs were subterranean chambers and passages, usually cut out of the solid rock, and used as places of burial, or of refuge. The early Christians made use of the catacombs in the Appian Way for worship, as well as for sepulture.—Ed.

[98] The Carcer Mamertinus,—one of the most ancient Roman structures,—overhung the Forum, as Livy tells us, “imminens foro,” underneath the Capitoline hill. It still exists, and is entered from the sacristy of the church of S. Giuseppe de Falagnami, to the left of the arch of Severus. It was originally a well (the Tullianum of Livy), and afterwards a prison, in which Jugurtha was starved to death, and Catiline’s accomplices perished. There are two chambers in the prison, one beneath the other; the lower-most containing, in its rock floor, a spring, which rises nearly to the surface. For the legend connected with it see the next note.—Ed.

[99] According to the legend, St. Peter, who was imprisoned in the Carcer Mamertinus under Nero, caused this spring to flow miraculously in order to baptize his jailors. Hence the building is called S. Pietro in Carcere.—Ed.

[100] Compare “Despondency Corrected,” The Excursion, book iv. l. 1058—

Ed.

[101] See the Fenwick note.—Ed.

[102] It would be ungenerous not to advert to the religious movement that, since the composition of these verses in 1837, has made itself felt, more or less strongly, throughout the English Church;—a movement that takes, for its first principle, a devout deference to the voice of Christian antiquity. It is not my office to pass judgment on questions of theological detail; but my own repugnance to the spirit and system of Romanism has been so repeatedly and, I trust, feelingly expressed, that I shall not be suspected of a leaning that way, if I do not join in the grave charge, thrown out, perhaps in the heat of controversy, against the learned and pious men to whose labours I allude. I speak apart from controversy; but, with strong faith in the moral temper which would elevate the present by doing reverence to the past, I would draw cheerful auguries for the English Church from this movement, as likely to restore among us a tone of piety more earnest and real than that produced by the mere formalities of the understanding, refusing, in a degree, which I cannot but lament, that its own temper and judgment shall be controlled by those of antiquity.—W.W. 1842.

[Sir George Beaumont told me that, when he first visited Italy, pine-trees of this species abounded, but that on his return thither, which was more than thirty years after, they had disappeared from many places where he had been accustomed to admire them, and had become rare all over the country, especially in and about Rome. Several Roman villas have within these few years passed into the hands of foreigners, who, I observed with pleasure, have taken care to plant this tree, which in course of years will become a great ornament to the city and to the general landscape. May I venture to add here, that having ascended the Monte Mario, I could not resist embracing the trunk of this interesting monument of my departed friend’s feelings for the beauties of nature, and the power of that art which he loved so much, and in the practice of which he was so distinguished?—I.F.]

[103] The Monte Mario is to the north-west of Rome, beyond the Janiculus and the Vatican. The view from the summit embraces Rome, the Campagna, and the sea. It is capped by the villa Millini, in which the “magnificent solitary pine-tree” of this sonnet still stands, amidst its cypress plantations.—Ed.

[104] “It was Mr. Theed, the sculptor, who informed us of the pine-tree being the gift of Sir George Beaumont.” H.C. Robinson. (See Memoirs of Wordsworth, by his nephew, vol. ii. p. 330.)—Ed.

[105] From the Mons Pincius, “collis hortorum,” where were the gardens of Lucullus, there is a remarkable view of modern Rome.—Ed.

[106] Within a couple of hours of my arrival at Rome, I saw from Monte Pincio, the Pine tree as described in the sonnet; and, while expressing admiration at the beauty of its appearance, I was told by an acquaintance of my fellow-traveller, who happened to join us at the moment, that a price had been paid for it by the late Sir G. Beaumont, upon condition that the proprietor should not act upon his known intention of cutting it down.—W.W. 1842.

[Sight is at first sight a sad enemy to imagination and to those pleasures belonging to old times with which some exertions of that power will always mingle: nothing perhaps brings this truth home to the feelings more than the city of Rome; not so much in respect to the impression made at the moment when it is first seen and looked at as a whole, for then the imagination may be invigorated and the mind’s eye quickened; but when particular spots or objects are sought out, disappointment is I believe invariably felt. Ability to recover from this disappointment will exist in proportion to knowledge, and the power of the mind to reconstruct out of fragments and parts, and to make details in the present subservient to more adequate comprehension of the past.—I.F.]

[107] The Tarpeian rock, from which those condemned to death were hurled, is not now precipitous, as it used to be: the ground having been much raised by successive heaps of ruin.—Ed.

[108] Niebuhr, in his Lectures on Roman History (1826-29), was one of the first to point out the legendary character of much of the earlier history, and its “historical impossibility.” He explained the way in which much of it had originated in family and national vanity, etc.—Ed.

[109] Clio, daughter of Zeus and Mnemosyne, the first-born of the Muses, presided over History. It was her office to record the actions of illustrious heroes.—Ed.

[110] 1845.

[111] 1845.

[112] 1845.

[I have a private interest in this Sonnet, for I doubt whether it would ever have been written but for the lively picture given me by Anna Ricketts of what she had witnessed of the indignation and sorrow expressed by some Italian noblemen of their acquaintance upon the surrender, which circumstances had obliged them to make, of the best portion of their family mansions to strangers.—I.F.]

[114] 1845.

[115] 1845.

[This Sonnet is founded on simple fact, and was written to enlarge, if possible, the views of those who can see nothing but evil in the intercessions countenanced by the Church of Rome. That they are in many respects lamentably pernicious must be acknowledged; but, on the other hand, they who reflect, while they see and observe, cannot but be struck with instances which will prove that it is a great error to condemn in all cases such mediation as purely idolatrous. This remark bears with especial force upon addresses to the Virgin.—I.F.]

[116] Albano, 10 miles south-east of Rome, is a small town and episcopal residence, a favourite autumnal resort of Roman citizens. It is on the site of the ruins of the villa of Pompey. Monte Carlo (the Monte Calvo of this sonnet) is the ancient Mons Latialis, 3127 feet high. At its summit a convent of Passionist Monks occupies the site of the ancient temple of Jupiter.—Ed.

[117] The ilex-grove of the Villa Doria is one of the most marked features of Albano.—Ed.

[118] 1845.

[119] The Anio joins the Tiber north of Rome, flowing from the north-east past Tivoli.—Ed.

[120] 1845.

[121] 1845.

[122] The ancient Classic period, and that of the Renaissance.—Ed.

[123] This period seems to have been already entered. Compare Mrs. Browning’s “Poems before Congress,” passim.—Ed.

[124] The Carthaginian general Hannibal defeated the Roman Consul C. Flaminius, near the lacus Trasimenus, 217 B.C., with a loss of 15,000 men. (See Livy, book xxii. 4, etc.)—Ed.

[125] Compare Hannibal, A Historical Drama, by the late Professor John Nichol, act II. scene vi. p. 107—

Ed.

[126] Sanguinetto.—W.W. 1845.

[127] Lake Thrasymene is the largest of the Etrurian lakes, being ten miles in length and three in breadth.—Ed.

[128] C. Flaminius.—Ed.

[129] After the battle of Lake Thrasymene, Hannibal did not push on to Rome, but turned through the Apennines to Apulia, just as subsequently after the battle of Cannas he remained inactive.—Ed.

May 25th 1837

[Among a thousand delightful feelings connected in my mind with the voice of the cuckoo, there is a personal one[68] which is rather melancholy. I was first convinced that age had rather dulled my hearing, by not being able to catch the sound at the same distance as the younger companions of my walks; and of this failure I had a proof upon the occasion that suggested these verses. I did not hear the sound till Mr. Robinson had twice or thrice directed my attention to it.]

[130] Laverna is a corruption of Alverna (now called Alverniac). It is about five or six hours’ walk from Camaldoli, on a height of the Apennines, not far from the sources of the Anio. To reach it, “the southern height of the Monte Valterona is ascended as far as the chapel of St. Romaiald; then a descent is made to Moggiona, beyond which the path turns to the left, traversing a long and fatiguing succession of gorges and slopes; the path at the base of the mountain is therefore preferable. The market town of Soci in the valley of the Archiano is first reached, then the profound valley of the Corsaline; beyond it rises a blunted cone, on which the path ascends in windings to a stony plain with marshy meadows. Above this rises the abrupt sandstone mass of the Vernia, to the height of 850 feet. On its S.W. slope, one-third of the way up, and 3906 feet above the sea-level, is seen a wall with small windows, the oldest part of the monastery, built in 1218 by St. Francis of Assisi. The church dates from 1284.… One of the grandest points is the Penna della Vernia (4796 feet), the ridge of the Vernia, also known as l’Apennino, the ‘rugged rock between the sources of the Tiber and Anio,’ as it is called by Dante (Paradiso, ii. 106).… Near the monastery are the Luoghi Santi, a number of grottos and rock-hewn chambers in which St. Francis once lived.” (See Baedeker’s Northern Italy, 1886, p. 463.)

“The Monte Alverno, or Monte della Verni is situated on the border of Tuscany, near the sources of the Tiber and Anio, not far from the Castle of Chiusi, where Orlando lived.” (Mrs. Oliphant’s Francis of Assisi, chap. xvi. p. 248.)

See also Herzog’s Real-Encyklopädie für protestantische Theologie und Kirche, vol. iv. p. 655.—Ed.

[133] From the difference in the colour of each side of the leaf, a grove of olives when wind-tossed is pre-eminently a “twinkling canopy.”—Ed.

[134] See note, p. 67.—Ed.

[135] St. Francis of Assisi, founder of the order of Friars Minors, after establishing numerous monasteries in Italy, Spain, and France, resigned his office and retired to this, one of the highest of the Apennine heights. See note, p. 67. He was canonised in 1230. Henry Crabb Robinson tells us, “It was at Laverna that he” [W.W.] “led me to expect that he had found a subject on which he could write, and that was the love which birds bore to St. Francis. He repeated to me a short time afterwards a few lines, which I do not recollect amongst those he has written on St. Francis in this poem. On the journey, one night only I heard him in bed composing verses, and on the following day I offered to be his amanuensis; but I was not patient enough, I fear, and he did not employ me a second time. He made inquiries for St. Francis’s biography, as if he would dub him his Leibheiliger (body-saint), as Goethe (saying that every one must have one) declared St. Philip Neri to be his.” (See the Memoirs of William Wordsworth, by his nephew, vol. ii. p. 331)—Ed.

[136] The characteristic feature of the Franciscan order was its vow of Poverty, and Francis desired that it should be taken in the most rigorous sense, viz. that no individual member of the fraternity, nor the fraternity itself, should be allowed to possess any property whatsoever, even in things necessary to human use.—Ed.

[137] The members of the Franciscan order were the Stoics of Christendom. The order has been powerful, and of great service to the Roman Church—alike in literature, and in practical action and enterprise.—Ed.

This famous sanctuary was the original establishment of Saint Romualdo (or Rumwald, as our ancestors saxonised the name) in the 11th century, the ground (campo) being given by a Count Maldo. The Camaldolensi, however, have spread wide as a branch of Benedictines, and may therefore be classed among the gentlemen of the monastic orders. The society comprehends two orders, monks and hermits; symbolised by their arms, two doves drinking out of the same cup. The monastery in which the monks here reside is beautifully situated, but a large unattractive edifice, not unlike a factory. The hermitage is placed in a loftier and wilder region of the forest. It comprehends between 20 and 30 distinct residences, each including for its single hermit an inclosed piece of ground and three very small apartments. There are days of indulgence when the hermit may quit his cell, and when old age arrives, he descends from the mountain and takes his abode among the monks.

My companion had, in the year 1831, fallen in with the monk, the subject of these two sonnets, who showed him his abode among the hermits. It is from him that I received the following[138] particulars. He was then about 40 years of age, but his appearance was that of an older man. He had been a painter by profession, but on taking orders changed his name from Santi to Raffaello, perhaps with an unconscious reference as well to the great Sanzio d’Urbino as to the archangel. He assured my friend that he had been 13 years in the hermitage and had never known melancholy or ennui. In the little recess for study and prayer, there was a small collection of books. “I read only,” said he, “books of asceticism and mystical theology.” On being asked the names of the most famous[139] mystics, he enumerated Scaramelli, San Giovanni della Croce, St. Dionysius the Areopagite (supposing the work which bears his name to be really his),[140] and with peculiar emphasis Ricardo di San Vittori. The works of Saint Theresa are also in high repute among ascetics.[141] These names may interest some of my readers.

We heard that Raffaello was then living in the convent; my friend sought in vain to renew his acquaintance with him. It was probably a day of seclusion. The reader will perceive that these sonnets were supposed to be written when he was a young man.—W.W. 1842.

The monastery of Camaldoli is on the highest point of the hills near Naples (1476 feet), and commands one of the finest views in Italy.—Ed.

[138] 1845.

[139] 1845.

[140] 1845.

[141] 1845.

[142] 1845.

[143] In justice to the Benedictines of Camaldoli, by whom strangers are so hospitably entertained, I feel obliged to notice, that I saw among them no other figures at all resembling, in size and complexion, the two Monks described in this Sonnet. What was their office, or the motive which brought them to this place of mortification, which they could not have approached without being carried in this or some other way, a feeling of delicacy prevented me from inquiring. An account has before been given of the hermitage they were about to enter. It was visited by us towards the end of the month of May; yet snow was lying thick under the pine-trees, within a few yards of the gate.—W.W. 1842.

[144] See note, pp. 72, 73.—Ed.

[I must confess, though of course I did not acknowledge it in the few lines I wrote in the Strangers’ book kept at the convent, that I was somewhat disappointed at Vallombrosa. I had expected, as the name implies, a deep and narrow valley overshadowed by enclosing hills; but the spot where the convent stands is in fact not a valley at all, but a cove or crescent open to an extensive prospect. In the book before mentioned, I read the notice in the English language that if anyone would ascend the steep ground above the convent, and wander over it, he would be abundantly rewarded by magnificent views. I had not time to act upon this recommendation, and only went with my young guide to a point, nearly on a level with the site of the convent, that overlooks the Vale of Arno for some leagues. To praise great and good men has ever been deemed one of the worthiest employments of poetry,[76] but the objects of admiration vary so much with time and circumstances, and the noblest of mankind have been found, when intimately known, to be of characters so imperfect, that no eulogist can find a subject which he will venture upon with the animation necessary to create sympathy, unless he confines himself to a particular part or he takes something of a one-sided view of the person he is disposed to celebrate. This is a melancholy truth, and affords a strong reason for the poetic mind being chiefly exercised in works of fiction: the poet can then follow wherever the spirit of admiration leads him, unchecked by such suggestions as will be too apt to cross his way if all that he is prompted to utter is to be tested by fact. Something in this spirit I have written in the note attached to the Sonnet on the King of Sweden; and many will think that in this poem and elsewhere I have spoken of the author of Paradise Lost in a strain of panegyric scarcely justifiable by the tenor of some of his opinions, whether theological or political, and by the temper he carried into public affairs, in which, unfortunately for his genius, he was so much concerned.—I.F.]

[145] The name of Milton is pleasingly connected with Vallombrosa in many ways. The pride with which the Monk, without any previous question from me, pointed out his residence, I shall not readily forget. It may be proper here to defend the Poet from a charge which has been brought against him, in respect to the passage in Paradise Lost, where this place is mentioned. It is said, that he has erred in speaking of the trees there being deciduous, whereas they are, in fact, pines. The fault-finders are themselves mistaken; the natural woods of the region of Vallombrosa are deciduous, and spread to a great extent; those near the convent are, indeed, mostly pines; but they are avenues of trees planted within a few steps of each other, and thus composing large tracts of wood; plots of which are periodically cut down. The appearance of those narrow avenues, upon steep slopes open to the sky, on account of the height which the trees attain by being forced to grow upwards, is often very impressive. My guide, a boy of about fourteen years old, pointed this out to me in several places.—W.W. 1842.

[146] Compare Paradise Lost, book i. l. 302. Vallombrosa—the shady valley—is 18 miles distant from Florence. Wordsworth’s quotation from Milton was from memory. It is not quite accurate.—Ed.

[147] See for the two first lines, Stanzas composed in the Simplon Pass.—W.W. 1842. (See vol. vi. p. 357.)—Ed.

[148] The monastery of Vallombrosa was founded about 1050, by S. Giovanni Gnalberto. It was suppressed in 1869, and is now converted into the R. Instituto Forestale, or forest school. The “cell,” the “sequestered retreat” referred to by Wordsworth, is doubtless Il Paradisino, or Le Celle, a small hermitage 266 feet above the monastery, which is itself 2980 feet above the sea.—Ed.

[149] Compare Milton’s letter to Benedetto Bonmattei of Florence, written during his stay in the city, September 10, 1638.—Ed.

[150] 1845.

[151] 1845.

[152] Compare Paradise Lost, book iii. l. 29—

Ed.

[153] 1845.

[Upon what evidence the belief rests that this stone was a favourite seat of Dante, I do not know; but a man would little consult his own interest as a traveller, if he should busy himself with doubts as to the fact. The readiness with which traditions of this character are received, and the fidelity with which they are preserved from generation to generation, are an evidence of feelings honourable to our nature. I remember how, during one of my rambles in the course of a college vacation, I was pleased on being shown a seat near a kind of rocky cell at the source of the river, on which it was said that Congreve wrote his Old Bachelor. One can scarcely hit on any performance less in harmony with the scene; but it was a local tribute paid to intellect by those who had not troubled themselves to estimate the moral worth of that author’s comedies; and why should they? He was a man distinguished in his day; and the sequestered neighbourhood in which he often resided was perhaps as proud of him as Florence of her Dante: it is the same feeling, though proceeding from persons one cannot bring together in this way without offering some apology to the Shade of the great Visionary.—I.F.]

[154] The Sasso di Dante is built into the wall of the house, No. 29 Casa dei Canonici, close to the Duomo.—Ed.