The Project Gutenberg EBook of The Every-day Book and Table Book. v. 3 (of

3), by William Hone

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most

other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of

the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have

to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook.

Title: The Every-day Book and Table Book. v. 3 (of 3)

Everlasting Calendar of Popular Amusements, etc, etc

Author: William Hone

Release Date: October 15, 2016 [EBook #53277]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK EVERY-DAY BOOK ***

Produced by Chris Curnow, Harry Lamé, Google Books for

some images. and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team

at http://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images

generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Please see the Transcriber’s Notes

at the end of this text.

The cover image has been created for this e-text and is placed in the public domain.

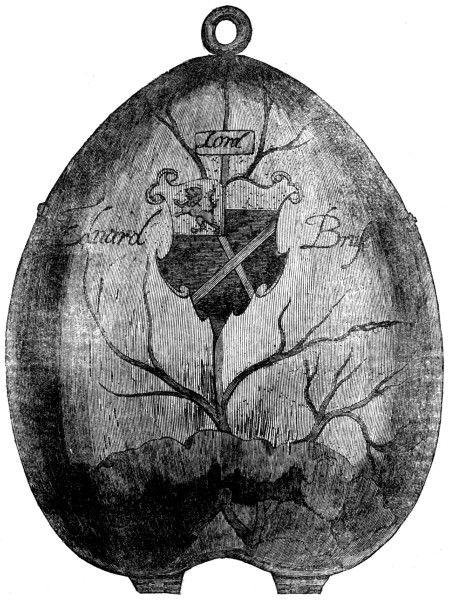

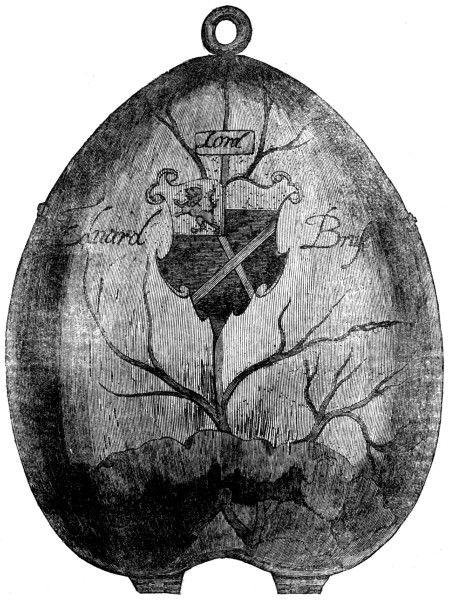

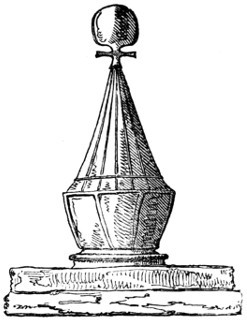

PETRARCH’S INKSTAND.

In the Possession of Miss Edgeworth, presented to her by a Lady.

By beauty won from soft Italia’s land,

Here Cupid, Petrarch’s Cupid, takes his stand.

Arch suppliant, welcome to thy fav’rite isle,

Close thy spread wings, and rest thee here awhile;

Still the true heart with kindred strains inspire,

Breathe all a poet’s softness, all his fire;

But if the perjured knight approach this font,

Forbid the words to come as they were wont,

Forbid the ink to flow, the pen to write,

And send the false one baffled from thy sight.

Miss Edgeworth.

THE

EVERY-DAY BOOK

AND

TABLE BOOK;

OR,

EVERLASTING CALENDAR OF POPULAR AMUSEMENTS,

SPORTS, PASTIMES, CEREMONIES, MANNERS,

CUSTOMS, AND EVENTS,

INCIDENT TO

Each of the Three Hundred and Sixty-five Days,

IN PAST AND PRESENT TIMES;

FORMING A

COMPLETE HISTORY OF THE YEAR, MONTHS, AND SEASONS,

AND A

PERPETUAL KEY TO THE ALMANAC;

INCLUDING

ACCOUNTS OF THE WEATHER, RULES FOR HEALTH AND CONDUCT, REMARKABLE AND

IMPORTANT ANECDOTES, FACTS, AND NOTICES, IN CHRONOLOGY, ANTIQUITIES, TOPO-

GRAPHY,

BIOGRAPHY, NATURAL HISTORY, ART, SCIENCE, AND GENERAL LITERATURE;

DERIVED FROM THE MOST AUTHENTIC SOURCES, AND VALUABLE ORIGINAL COMMUNI-

CATIONS,

WITH POETICAL ELUCIDATIONS, FOR DAILY USE AND DIVERSION.

BY WILLIAM HONE.

I tell of festivals, and fairs, and plays,

Of merriment, and mirth, and bonfire blaze;

I tell of Christmas-mummings, new year’s day,

Of twelfth-night king and queen, and children’s play;

I tell of valentines, and true-love’s-knots,

Of omens, cunning men, and drawing lots:

I tell of brooks, of blossoms, birds and bowers,

Of April, May, of June, and July-flowers;

I tell of May-poles, hock-carts, wassails, wakes,

Of bridegrooms, brides, and of their bridal cakes;

I tell of groves, of twilights, and I sing

The court of Mab, and of the fairy king.

Herrick.

WITH FOUR HUNDRED AND THIRTY-SIX ENGRAVINGS.

IN THREE VOLUMES.

VOL. III.

LONDON:

PRINTED FOR THOMAS TEGG,

73, CHEAPSIDE.

J. HADDON, PRINTER, CASTLE STREET, FINSBURY.

PREFACE.

On the close of the Every-Day Book, which commenced on New Year’s

Day, 1825, and ended in the last week of 1826, I began this work.

The only prospectus of the Table Book was the eight versified lines on the

title-page. They appeared on New Year’s Day, prefixed to the first number;

which, with the successive sheets, to the present date, constitute the volume

now in the reader’s hands, and the entire of my endeavours during the half

year.

So long as I am enabled, and the public continue to be pleased, the Table

Book will be continued. The kind reception of the weekly numbers, and the

monthly parts, encourages me to hope that like favour will be extended to the

half-yearly volume. Its multifarious contents and the illustrative engravings,

with the help of the copious index, realize my wish, “to please the young,

and help divert the wise.” Perhaps, if the good old window-seats had not gone

out of fashion, it might be called a parlour-window book—a good name for a

volume of agreeable reading selected from the book-case, and left lying about,

for the constant recreation of the family, and the casual amusement of visitors.

W. HONE.

Midsummer, 1827.

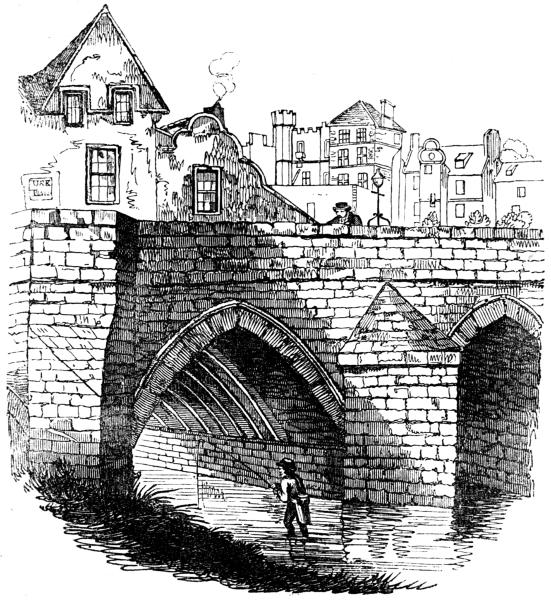

THE FRONTISPIECE.

PETRARCH’S INKSTAND.

Miss Edgeworth’s lines express her estimation

of the gem she has the happiness

to own. That lady allowed a few casts

from it in bronze, and a gentleman who

possesses one, and who favours the “Table

Book” with his approbation, permits its

use for a frontispiece to this volume. The

engraving will not be questioned as a decoration,

and it has some claim to be regarded

as an elegant illustration of a miscellany

which draws largely on art and literature,

and on nature itself, towards its supply.

“I delight,” says Petrarch, “in my pictures.

I take great pleasure also in images;

they come in show more near unto nature

than pictures, for they do but appear; but

these are felt to be substantial, and their

bodies are more durable. Amongst the

Grecians the art of painting was esteemed

above all handycrafts, and the chief of all

the liberal arts. How great the dignity hath

been of statues; and how fervently the study

and desire of men have reposed in such

pleasures, emperors and kings, and other

noble personages, nay, even persons of inferior

degree, have shown, in their industrious

keeping of them when obtained.”

Insisting on the golden mean, as a rule of

happiness, he says, “I possess an amazing

collection of books, for attaining this, and

every virtue: great is my delight in beholding

such a treasure.” He slights persons

who collect books “for the pleasure of

boasting they have them; who furnish their

chambers with what was invented to furnish

their minds; and use them no otherwise

than they do their Corinthian tables, or

their painted tables and images, to look

at.” He contemns others who esteem not

the true value of books, but the price at

which they may sell them—“a new practice”

(observe it is Petrarch that speaks)

“crept in among the rich, whereby they may

attain one art more of unruly desire.” He

repeats, with rivetting force, “I have great

plenty of books: where such scarcity has

been lamented, this is no small possession:

I have an inestimable many of books!”

He was a diligent collector, and a liberal

imparter of these treasures. He corresponded

with Richard de Bury, an illustrious

prelate of our own country, eminent

for his love of learning and learned men,

and sent many precious volumes to England

to enrich the bishop’s magnificent

library. He vividly remarks, “I delight

passionately in my books;” and yet he who

had accumulated them largely, estimated

them rightly: he has a saying of books

worthy of himself—“a wise man seeketh

not quantity but sufficiency.”

Petrarch loved the quiet scenes of nature,

and these can scarcely be observed from a

carriage or while riding, and are never

enjoyed but on foot; and to me—on whom

that discovery was imposed, and who am

sometimes restrained from country walks,

by necessity—it was no small pleasure,

when I read a passage in his “View of

Human Nature,” which persuaded me of

his fondness for the exercise: “A journey

on foot hath most pleasant commodities;

a man may go at his pleasure; none

shall stay him, none shall carry him beyond

his wish; none shall trouble him; he hath

but one labour, the labour of nature—to

go.”

In “The Indicator” there is a paper of

peculiar beauty, by Mr. Leigh Hunt, “on

receiving a sprig of myrtle from Vaucluse,”

with a paragraph suitable to this occasion:

“We are supposing that all our readers

are acquainted with Petrarch. Many of

them doubtless know him intimately.

Should any of them want an introduction

to him, how should we speak of him in the

gross? We should say, that he was one

of the finest gentlemen and greatest scholars

that ever lived; that he was a writer

who flourished in Italy in the fourteenth

century, at the time when Chaucer was

young, during the reigns of our Edwards;

that he was the greatest light of his age;

that although so fine a writer himself, and

the author of a multitude of works, or

rather because he was both, he took the

greatest pains to revive the knowledge of

the ancient learning, recommending it every

where, and copying out large manuscripts

with his own hand; that two great cities,

Paris and Rome, contended which should

have the honour of crowning him; that he

was crowned publicly, in the metropolis of

the world, with laurel and with myrtle;

that he was the friend of Boccaccio the

father of Italian prose; and lastly, that his

greatest renown nevertheless, as well as the

predominant feelings of his existence, arose

from the long love he bore for a lady of

Avignon, the far-famed Laura, whom he

fell in love with on the 6th of April, 1327,

on a Good Friday; whom he rendered

illustrious in a multitude of sonnets, which

have left a sweet sound and sentiment in

the ear of all after lovers; and who died,

still passionately beloved, in the year 1348,

on the same day and hour on which he first

beheld her. Who she was, or why their

connection was not closer, remains a mystery.

But that she was a real person, and

that in spite of all her modesty she did not

show an insensible countenance to his passion,

is clear from his long-haunted imagination,

from his own repeated accounts,

from all that he wrote, uttered, and thought.

One love, and one poet, sufficed to give the

whole civilized world a sense of delicacy

in desire, of the abundant riches to be

found in one single idea, and of the going

out of a man’s self to dwell in the soul and

happiness of another, which has served to

refine the passion for all modern times;

and perhaps will do so, as long as love renews

the world.”

At Vaucluse, or Valchiusa, “a remarkable

spot in the old poetical region of Provence,

consisting of a little deep glen of

green meadows surrounded with rocks, and

containing the fountain of the river Sorgue,”

Petrarch resided for several years, and

composed in it the greater part of his

poems.

The following is a translation by sir

William Jones, of

AN ODE, BY PETRARCH,

To the Fountain of Valchiusa

Ye clear and sparkling streams!

(Warm’d by the sunny beams)

Through whose transparent crystal Laura play’d;

Ye boughs that deck the grove,

Where Spring her chaplets wove,

While Laura lay beneath the quivering shade;

Sweet herbs! and blushing flowers!

That crown yon vernal bowers,

For ever fatal, yet for ever dear;

And ye, that heard my sighs

When first she charm’d my eyes,

Soft-breathing gales! my dying accents hear.

If Heav’n has fix’d my doom,

That Love must quite consume

My bursting heart, and close my eyes in death

Ah! grant this slight request,—

That here my urn may rest,

When to its mansion flies my vital breath.

This pleasing hope will smooth

My anxious mind, and soothe

The pangs of that inevitable hour;

My spirit will not grieve

Her mortal veil to leave

In these calm shades, and this enchanting bower

Haply, the guilty maid

Through yon accustom’d glade

To my sad tomb will take her lonely way

Where first her beauty’s light

O’erpower’d my dazzled sight,

When love on this fair border bade me stray:

There, sorrowing, shall she see,

Beneath an aged tree,

Her true, but hapless lover’s lowly bier;

Too late her tender sighs

Shall melt the pitying skies,

And her soft veil shall hide the gushing tear

O! well-remember’d day,

When on yon bank she lay,

Meek in her pride, and in her rigour mild;

The young and blooming flowers,

Falling in fragrant showers,

Shone on her neck, and on her bosom smil’d

Some on her mantle hung,

Some in her locks were strung,

Like orient gems in rings of flaming gold;

Some, in a spicy cloud

Descending, call’d aloud,

“Here Love and Youth the reins of empire hold.”

I view’d the heavenly maid

And, rapt in wonder, said—

“The groves of Eden gave this angel birth,”

Her look, her voice, her smile,

That might all Heaven beguile,

Wafted my soul above the realms of earth

The star-bespangled skies

Were open’d to my eyes;

Sighing I said, “Whence rose this glittering scene?”

Since that auspicious hour,

This bank, and odorous bower,

My morning couch, and evening haunt have been.

Well mayst thou blush, my song,

To leave the rural throng

And fly thus artless to my Laura’s ear,

But, were thy poet’s fire

Ardent as his desire,

Thou wert a song that Heaven might stoop to hear

It is within probability to imagine, that

the original of this “ode” may have been

impressed on the paper, by Petrarch’s pen,

from the inkstand of the frontispiece.

[I-1,

I-2]

Vol. I.—1.

THE

TABLE BOOK.

Formerly, a “Table Book” was a memorandum

book, on which any thing was

graved or written without ink. It is mentioned

by Shakspeare. Polonius, on disclosing

Ophelia’s affection for Hamlet to the

king, inquires

“When I had seen this hot love on the wing,

—————————— what might you,

Or my dear majesty, your queen here, think,

If I had play’d the desk, or table-book?”

Dr. Henry More, a divine, and moralist,

of the succeeding century, observes, that

“Nature makes clean the table-book first,

and then portrays upon it what she pleaseth.”

In this sense, it might have been

used instead of a tabula rasa, or sheet of

blank writing paper, adopted by Locke as

an illustration of the human mind in its

incipiency. It is figuratively introduced

to nearly the same purpose by Swift: he

tells us that

“Nature’s fair table-book, our tender souls,

We scrawl all o’er with old and empty rules,

Stale memorandums of the schools.”

Dryden says, “Put into your Table-Book

whatsoever you judge worthy.”[1]

I hope I shall not unworthily err, if, in

the commencement of a work under this

title, I show what a Table Book was.

Table books, or tablets, of wood, existed

before the time of Homer, and among the

Jews before the Christian æra. The table

books of the Romans were nearly like ours,

which will be described presently; except

that the leaves, which were two, three, or

more in number, were of wood surfaced

with wax. They wrote on them with a style,

one end of which was pointed for that purpose,

and the other end rounded or flattened,

for effacing or scraping out. Styles were

made of nearly all the metals, as well as of

bone and ivory; they were differently formed,

and resembled ornamented skewers; the

common style was iron. More anciently,

the leaves of the table book were without

wax, and marks were made by the iron

style on the bare wood. The Anglo-Saxon

style was very handsome. Dr. Pegge was

of opinion that the well-known jewel of

Alfred, preserved in the Ashmolean

museum at Oxford, was the head of the

style sent by that king with Gregory’s

Pastoral to Athelney.[2]

A gentleman, whose profound knowledge

of domestic antiquities surpasses that of

preceding antiquaries, and remains unrivalled

by his contemporaries, in his “Illustrations

of Shakspeare,” notices Hamlet’s

expression, “My tables,—meet it is I set

it down.” On that passage he observes,

that the Roman practice of writing on wax

tablets with a style was continued through

the middle ages; and that specimens of

wooden tables, filled with wax, and constructed

in the fourteenth century, were

preserved in several of the monastic libraries

in France. Some of these consisted of

as many as twenty pages, formed into a

book by means of parchment bands glued

to the backs of the leaves. He says that

in the middle ages there were table books

of ivory, and sometimes, of late, in the form

of a small portable book with leaves and

clasps; and he transfers a figure of one of

the latter from an old work[3] to his own:

it resembles the common “slate-books”

still sold in the stationers’ shops. He presumes

that to such a table book the archbishop

of York alludes in the second part

of King Henry IV.,

“And therefore will he wipe his tables clean

And keep no tell tale to his memory.”

As in the middle ages there were table-books

with ivory leaves, this gentleman

remarks that, in Chaucer’s “Sompnour’s

Tale,” one of the friars is provided with

“A pair of tables all of ivory,

And a pointel ypolished fetishly,

And wrote alway the names, as he stood,

Of alle folk that yave hem any good.”

He instances it as remarkable, that neither

public nor private museums furnished specimens

of the table books, common in

Shakspeare’s time. Fortunately, this observation

is no longer applicable.

A correspondent, understood to be Mr.

Douce, in Dr. Aikin’s “Athenæum,” subsequently

says, “I happen to possess a

table-book of Shakspeare’s time. It is a

little book, nearly square, being three inches

wide and something less than four in length,

bound stoutly in calf, and fastening with

four strings of broad, strong, brown tape.

The title as follows: ‘Writing Tables, with

a Kalender for xxiiii yeeres, with sundrie

necessarie rules. The Tables made by

Robert Triple. London, Imprinted for the

Company of Stationers.’ The tables are

inserted immediately after the almanack.

At first sight they appear like what we

call asses-skin, the colour being precisely

[I-3,

I-4]

the same, but the leaves are thicker: whatever

smell they may have had is lost, and

there is no gloss upon them. It might be

supposed that the gloss has been worn off;

but this is not the case, for most of the

tables have never been written on. Some

of the edges being a little worn, show that

the middle of the leaf consists of paper;

the composition is laid on with great

nicety. A silver style was used, which is

sheathed in one of the covers, and which

produces an impression as distinct, and as

easily obliterated as a black-lead pencil.

The tables are interleaved with common

paper.”

In July, 1808, the date of the preceding

communication, I, too, possessed a table

book, and silver style, of an age as ancient,

and similar to that described; except that

it had not “a Kalender.” Mine was

brought to me by a poor person, who found

it in Covent-garden on a market day.

There were a few ill-spelt memoranda

respecting vegetable matters formed on its

leaves with the style. It had two antique

slender brass clasps, which were loose; the

ancient binding had ceased from long wear

to do its office, and I confided it to Mr. Wills,

the almanack publisher in Stationers’-court,

for a better cover and a silver clasp. Each

being ignorant of what it was, we spoiled

“a table-book of Shakspeare’s time.”

The most affecting circumstance relating

to a table book is in the life of the beautiful

and unhappy “Lady Jane Grey.”

“Sir John Gage, constable of the Tower,

when he led her to execution, desired her

to bestow on him some small present,

which he might keep as a perpetual memorial

of her: she gave him her table-book,

wherein she had just written three sentences,

on seeing her husband’s body; one in

Greek, another in Latin, and a third in

English. The purport of them was, that

human justice was against his body, but

the divine mercy would be favourable to

his soul; and that, if her fault deserved

punishment, her youth at least, and her

imprudence, were worthy of excuse, and

that God and posterity, she trusted, would

show her favour.”[4]

Having shown what the ancient table

book was, it may be expected that I should

say something about

My

Table Book.

The title is to be received in a larger

sense than the obsolete signification: the

old table books were for private use—mine

is for the public; and the more the public

desire it, the more I shall be gratified. I

have not the folly to suppose it will pass

from my table to every table, but I think that

not a single sheet can appear on the table

of any family without communicating some

information, or affording some diversion.

On the title-page there are a few lines

which briefly, yet adequately, describe the

collections in my Table Book: and, as regards

my own “sayings and doings,” the

prevailing disposition of my mind is perhaps

sufficiently made known through the

Every-Day Book. In the latter publication,

I was inconveniently limited as to

room; and the labour I had there prescribed

to myself, of commemorating every day,

frequently prevented me from topics that

would have been more agreeable to my

readers than the “two grains of wheat in

a bushel of chaff,” which I often consumed

my time and spirits in endeavouring to

discover—and did not always find.

In my Table Book, which I hope will

never be out of “season,” I take the liberty

to “annihilate both time and space,” to

the extent of a few lines or days, and lease,

and talk, when and where I can, according

to my humour. Sometimes I present an

offering of “all sorts,” simpled from out-of-the-way

and in-the-way books; and, at

other times, gossip to the public, as to an

old friend, diffusely or briefly, as I chance

to be more or less in the giving “vein,”

about a passing event, a work just read, a

print in my hand, the thing I last thought

of, or saw, or heard, or, to be plain, about

“whatever comes uppermost.” In short,

my collections and recollections come forth

just as I happen to suppose they may be

most agreeable or serviceable to those

whom I esteem, or care for, and by whom

I desire to be respected.

My Table Book is enriched and diversified

by the contributions of my friends;

the teemings of time, and the press, give it

novelty; and what I know of works of art,

with something of imagination, and the

assistance of artists, enable me to add pictorial

embellishment. My object is to

blend information with amusement, and

utility with diversion.

My Table Book, therefore, is a series

of continually shifting scenes—a kind of

literary kaleidoscope, combining popular

forms with singular appearances—by which

youth and age of all ranks may be amused;

and to which, I respectfully trust, many

will gladly add something, to improve its

views.

[I-5,

I-6]

Ode to the New Year

From the Every Day Book: set to Music for the Table Book,

By J. K.

All hail to the birth of the Year! See golden-hair’d

Phœbus afar, Prepares to renew his career, And is

mounting his dew-spangled car. Stern Winter congeals every

brook, That murmur’d so lately with glee, And places a

snowy peruke On the head of each bald-pated tree.

Play music:

midi (3 kB)

⁂ For the remaining verses, see the Every-Day Book,

vol ii. p. 25.

[I-7,

I-8]

The New Year.

HAGMAN-HEIGH.

Anciently on new year’s day the Romans

were accustomed to carry small presents,

as new year’s gifts, to the senators,

under whose protection they were severally

placed. In the reigns of the emperors,

they flocked in such numbers with valuable

ones, that various decrees were made to

abolish the custom; though it always

continued among that people. The Romans

who settled in Britain, or the families connected

with them by marriage, introduced

these new year’s gifts among our forefathers,

who got the habit of making presents, even

to the magistrates. Some of the fathers of

the church wrote against them, as fraught

with the greatest abuses, and the magistrates

were forced to relinquish them. Besides

the well-known anecdote of sir Thomas

More, when lord chancellor,[5] many instances

might be adduced from old records,

of giving a pair of gloves, some with “linings,”

and others without. Probably from

thence has been derived the fashion of giving

a pair of gloves upon particular occasions,

as at marriages, funerals, &c. New

year’s gifts continue to be received and

given by all ranks of people, to commemorate

the sun’s return, and the prospect of

spring, when the gifts of nature are shared

by all. Friends present some small tokens

of esteem to each other—husbands to their

wives, and parents to their children. The

custom keeps up a cheerful and friendly

intercourse among acquaintance, and leads

to that good-humour and mirth so necessary

to the spirits in this dreary season. Chandlers

send as presents to their customers

large mould candles; grocers give raisins,

to make a Christmas pudding, or a pack of

cards, to assist in spending agreeably the

long evenings. In barbers’ shops “thrift-box,”

as it is called, is put by the apprentice

boys against the wall, and every customer,

according to his inclination, puts

something in. Poor children, and old infirm

persons, beg, at the doors of the charitable,

a small pittance, which, though

collected in small sums, yet, when put

together, forms to them a little treasure;

so that every heart, in all situations of life,

beats with joy at the nativity of his Saviour.

The Hagman Heigh is an old custom

observed in Yorkshire on new year’s eve, as

appertaining to the season. The keeper of

the pinfold goes round the town, attended

by a rabble at his heels, and knocking at

certain doors, sings a barbarous song, beginning

with—

“Tonight it is the new year’s night, to-morrow is the day;

We are come about for our right and for our ray,

As we us’d to do in old king Henry’s day:

Sing, fellows, sing, Hagman Heigh,” &c.

The song always concludes with “wishing

a merry Christmas and a happy new

year.” When wood was chiefly used as

fuel, in heating ovens at Christmas, this was

the most appropriate season for the hagman,

or wood-cutter, to remind his customers of

his services, and to solicit alms. The word

hag is still used in Yorkshire, to signify a

wood. The “hagg” opposite to Easby

formerly belonged to the abbey, to supply

them with fuel. Hagman may be a name

compounded from it. Some derive it from

the Greek Αγιαμηνη, the holy month, when

the festivals of the church for our Saviour’s

birth were celebrated. Formerly, on the

last day of the year, the monks and friars

used to make a plentiful harvest, by begging

from door to door, and reciting a kind of

carol, at the end of every stave of which

they introduced the words “agia mene,”

alluding to the birth of Christ. A very

different interpretation, however, was given

to it by one John Dixon, a Scotch presbyterian

minister, when holding forth against

this custom in one of his sermons at Kelso.

“Sirs, do you know what the hagman signifies?

It is the devil to be in the house;

that is the meaning of its Hebrew original.”[6]

SONNET

ON THE NEW YEAR.

When we look back on hours long past away,

And every circumstance of joy, or woe

That goes to make this strange beguiling show,

Call’d life, as though it were of yesterday,

We start to learn our quickness of decay.

Still flies unwearied Time;—on still we go

And whither?—Unto endless weal or woe,

As we have wrought our parts in this brief play.

Yet many have I seen whose thin blanched locks

But ill became a head where Folly dwelt,

Who having past this storm with all its shocks,

Had nothing learnt from what they saw or felt:

Brave spirits! that can look, with heedless eye,

On doom unchangeable, and fixt eternity.

[I-9,

I-10]

Antiquities.

Westminster Abbey.

The following letter, written by Horace

Walpole, in relation to the tombs, is curious.

Dr. ——, whom he derides, was Dr. Zachary

Pearce, dean of Westminster, and

editor of Longinus, &c.

Strawberry-hill, 1761.

I heard lately, that Dr. ——, a very

learned personage, had consented to let the

tomb of Aylmer de Valence, earl of Pembroke,

a very great personage, be removed

for Wolfe’s monument; that at first he had

objected, but was wrought upon by being

told that hight Aylmer was a knight templar,

a very wicked set of people as his lordship

had heard, though he knew nothing of

them, as they are not mentioned by Longinus.

I own I thought this a made story,

and wrote to his lordship, expressing my

concern that one of the finest and most

ancient monuments in the abbey should be

removed; and begging, if it was removed,

that he would bestow it on me, who would

erect and preserve it here. After a fortnight’s

deliberation, the bishop sent me an

answer, civil indeed, and commending my

zeal for antiquity! but avowing the story

under his own hand. He said, that at first

they had taken Pembroke’s tomb for a

knight templar’s;—observe, that not only

the man who shows the tombs names it

every day, but that there is a draught of it

at large in Dart’s Westminster;—that upon

discovering whose it was, he had been very

unwilling to consent to the removal, and at

last had obliged Wilton to engage to set it

up within ten feet of where it stands at present.

His lordship concluded with congratulating

me on publishing learned authors

at my press. I don’t wonder that a man

who thinks Lucan a learned author, should

mistake a tomb in his own cathedral. If I

had a mind to be angry, I could complain

with reason,—as having paid forty pounds

for ground for my mother’s funeral—that the

chapter of Westminster sell their church

over and over again: the ancient monuments

tumble upon one’s head through

their neglect, as one of them did, and killed

a man at lady Elizabeth Percy’s funeral;

and they erect new waxen dolls of queen

Elizabeth, &c. to draw visits and money

from the mob.

Biographical Memoranda.

Cometary Influence.

Brantome relates, that the duchess of

Angoulême, in the sixteenth century, being

awakened during the night, she was surprised

at an extraordinary brightness which

illuminated her chamber; apprehending it

to be the fire, she reprimanded her women

for having made so large a one; but they

assured her it was caused by the moon.

The duchess ordered her curtains to be undrawn,

and discovered that it was a comet

which produced this unusual light. “Ah!”

exclaimed she, “this is a phenomenon

which appears not to persons of common

condition. Shut the window, it is a comet,

which announces my departure; I must

prepare for death.” The following morning

she sent for her confessor, in the certainty

of an approaching dissolution. The physicians

assured her that her apprehensions

were ill founded and premature. “If I had

not,” replied she, “seen the signal for

death, I could believe it, for I do not feel

myself exhausted or peculiarly ill.” On

the third day after this event she expired,

the victim of terror. Long after this period

all appearances of the celestial bodies, not

perfectly comprehended by the multitude,

were supposed to indicate the deaths of

sovereigns, or revolutions in their governments.

Two Painters.

When the duke d’Aremberg was confined

at Antwerp, a person was brought in as a

spy, and imprisoned in the same place.

The duke observed some slight sketches by

his fellow prisoner on the wall, and, conceiving

they indicated talent, desired Rubens,

with whom he was intimate, and

by whom he was visited, to bring with

him a pallet and pencils for the painter, who

was in custody with him. The materials

requisite for painting were given to the

artist, who took for his subject a group of

soldiers playing at cards in the corner of a

prison. When Rubens saw the picture, he

cried out that it was done by Brouwer,

whose works he had often seen, and as

often admired. Rubens offered six hundred

guineas for it; the duke would by no means

part with it, but presented the painter with

a larger sum. Rubens exerted his interest,

and obtained the liberty of Brouwer, by

becoming his surety, received him into his

house, clothed as well as maintained him,

and took pains to make the world acquainted

with his merit. But the levity of Brouwer’s

temper would not suffer him long to consider

his situation any better than a state

of confinement; he therefore quitted Rubens,

and died shortly afterwards, in consequence

of a dissolute course of life.

[I-11,

I-12]

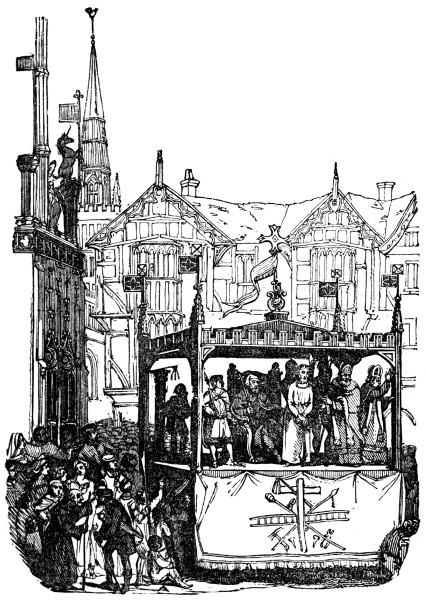

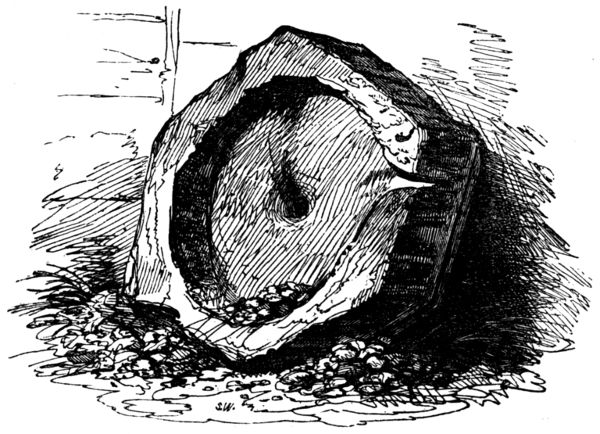

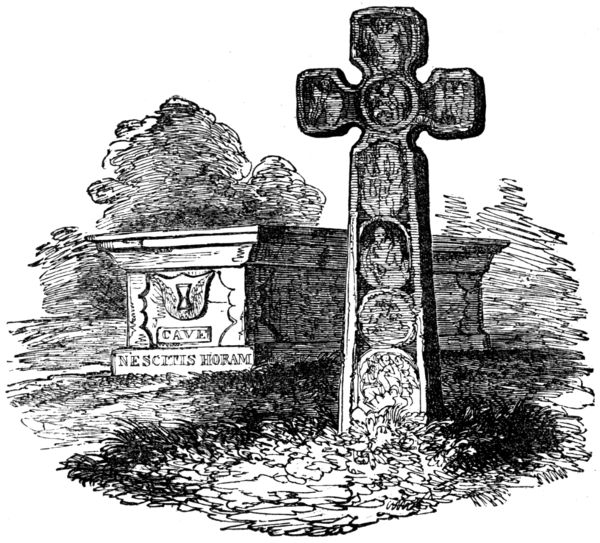

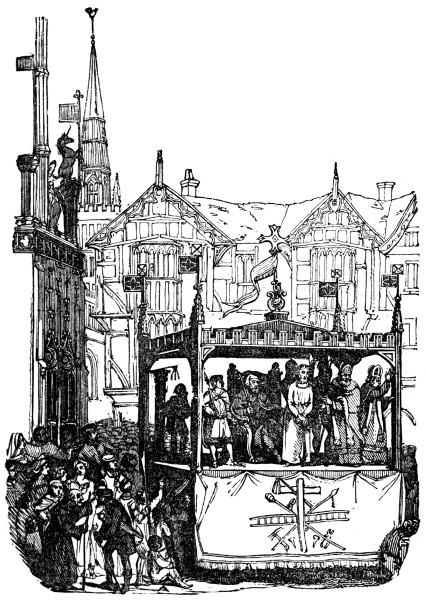

Representation of a Pageant Vehicle and Play.

Representation of a Pageant Vehicle and Play.

The state, and reverence, and show,

Were so attractive, folks would go

From all parts, ev’ry year, to see

These pageant-plays at Coventry.

This engraving is from a very curious

print in Mr. Sharp’s “Dissertatien on the

Pageants or Dramatic Mysteries, anciently

performed at Coventry.”

[I-13,

I-14]

Coventry is distinguished in the history

of the drama, because, under the title of

“Ludus Coventriæ,” there exists a manuscript

volume of most curious early plays,

not yet printed, nor likely to be, unless

there are sixty persons, at this time sufficiently

concerned for our ancient literature

and manners, to encourage a spirited gentleman

to print a limited number of copies.

If by any accident the manuscript should

be destroyed, these plays, the constant

theme of literary antiquaries from Dugdale

to the present period, will only be known

through the partial extracts of writers, who

have sometimes inaccurately transcribed

from the originals in the British Museum.[7]

Mr. Sharp’s taste and attainments qualifying

him for the task, and his residence

at Coventry affording him facility of research

among the muniments of the corporation,

he has achieved the real labour

of drawing from these and other unexplored

sources, a body of highly interesting

facts, respecting the vehicles, characters,

and dresses of the actors in the pageants or

dramatic mysteries anciently performed by

the trading companies of that city; which,

together with accounts of municipal entertainments

of a public nature, form his meritorious

volume.

Very little has been known respecting

the stage “properties,” before the rise of

the regular drama, and therefore the abundant

matter of that nature, adduced by this

gentleman, is peculiarly valuable. With

“The Taylors’ and Shearemens’ Pagant,”

complete from the original manuscript, he

gives the songs and the original music,

engraved on three plates, which is eminently

remarkable, because it is, perhaps, the only

existing specimen of the melodies in the

old Mysteries. There are ten other plates

in the work; one of them represents the

club, or maul, of Pilate, a character in the

pageant of the Cappers’ company. “By a

variety of entries it appears he had a club

or maul, stuffed with wool; and that the

exterior was formed of leather, is authenticated

by the actual existence of such a

club or maul, discovered by the writer of

this Dissertation, in an antique chest within

the Cappers’ chapel, (together with an iron

cresset, and some fragments of armour,)

where it had probably remained ever since

the breaking up of the pageant.” The

subject of the Cappers’ pageant was usually

the trial and crucifixion of Christ, and the

descent into hell.

The pageant vehicles were high scaffolds

with two rooms, a higher and a lower,

constructed upon four or six wheels; in

the lower room the performers dressed,

and in the higher room they played. This

higher room, or rather, as it may be called,

the “stage,” was all open on the top, that

the beholders might hear and see. On the

day of performance the vehicles were

wheeled, by men, from place to place,

throughout the city; the floor was strewed

with rushes; and to conceal the lower

room, wherein the performers dressed,

cloths were hung round the vehicle: there

is reason to believe that, on these cloths,

the subject of the performance was painted

or worked in tapestry. The higher room

of the Drapers’ vehicle was embattled, and

ornamented with carved work, and a crest;

the Smiths’ had vanes, burnished and

painted, with streamers flying.

In an engraving which is royal quarto,

the size of the work, Mr. Sharp has laudably

endeavoured to convey a clear idea of

the appearance of a pageant vehicle, and

of the architectural appearance of the houses

in Coventry, at the time of performing the

Mysteries. So much of that engraving as represents

the vehicle is before the reader on

the preceding page. The vehicle, supposed

to be of the Smiths’ company, is stationed

near the Cross in the Cross-cheaping, and

the time of action chosen is the period when

Pilate, on the charges of Caiphas and Annas,

is compelled to give up Christ for execution.

Pilate is represented on a throne,

or chair of state; beside him stands his son

with a sceptre and poll-axe, and beyond

the Saviour are the two high priests; the

two armed figures behind are knights. The

pageant cloth bears the symbols of the

passion.

Besides the Coventry Mysteries and other

matters, Mr. Sharp notices those of Chester,

and treats largely on the ancient setting of

the watch on Midsummer and St. John’s

Eve, the corporation giants, morris dancers,

minstrels, and waites.

I could not resist the very fitting opportunity

on the opening of the new year,

and of the Table Book together, to introduce

a memorandum, that so important an accession

has accrued to our curious literature,

[I-15,

I-16]

as Mr. Sharp’s “Dissertation on the

Coventry Mysteries.”

“The Thing to a T.”

A young man, brought up in the city of

London to the business of an undertaker,

went to Jamaica to better his condition.

Business flourished, and he wrote to his

father in Bishopsgate-street to send him,

with a quantity of black and grey cloth,

twenty gross of black Tacks. Unfortunately

he had omitted the top to his T, and

the order stood twenty gross of black Jacks.

His correspondent, on receiving the letter,

recollected a man, near Fleet-market, who

made quart and pint tin pots, ornamented

with painting, and which were called black

Jacks, and to him he gave the order

for the twenty gross of black Jacks. The

maker, surprised, said, he had not so many

ready, but would endeavour to complete

the order; this was done, and the articles

were shipped. The undertaker received

them with other consignments, and was

astonished at the mistake. A friend, fond

of speculation, offered consolation, by proposing

to purchase the whole at the invoice

price. The undertaker, glad to get rid of

an article he considered useless in that part

of the world, took the offer. His friend

immediately advertised for sale a number

of fashionable punch vases just arrived from

England, and sold the jacks, gaining 200

per cent.!

The young undertaker afterwards discoursing

upon his father’s blunder, was

told by his friend, in a jocose strain, to

order a gross of warming-pans, and see

whether the well-informed correspondents

in London would have the sagacity to consider

such articles necessary in the latitude

of nine degrees north. The young man

laughed at the suggestion, but really put

in practice the joke. He desired his father

in his next letter to send a gross of warming-pans,

which actually, and to the great

surprise of the son, reached the island of

Jamaica. What to do with this cargo he

knew not. His friend again became a purchaser

at prime cost, and having knocked

off the covers, informed the planters, that

he had just imported a number of newly-constructed

sugar ladles. The article under

that name sold rapidly, and returned a

large profit. The parties returned to England

with fortunes, and often told the story

of the black jacks and warming-pans over

the bottle, adding, that “Nothing is lost in

a good market.”

Books.

——————————————

Give me

Leave to enjoy myself. That place, that does

Contain my books, the best companions, is

To me a glorious court, where hourly I

Converse with the old sages and philosophers;

And sometimes for variety, I confer

With kings and emperors, and weigh their counsels;

Calling their victories, if unjustly got,

Unto a strict account; and in my fancy,

Deface their ill-placed statues. Can I then

Part with such constant pleasures, to embrace

Uncertain vanities? No: be it your care

To augment a heap of wealth: it shall be mine

To increase in knowledge.

Fletcher.

Imagination.

Imagination enriches every thing. A

great library contains not only books, but

“the assembled souls of all that men held

wise.” The moon is Homer’s and Shakspeare’s

moon, as well as the one we look

at. The sun comes out of his chamber in

the east, with a sparkling eye, “rejoicing

like a bridegroom.” The commonest thing

becomes like Aaron’s rod, that budded.

Pope called up the spirits of the Cabala to

wait upon a lock of hair, and justly gave it

the honours of a constellation; for he has

hung it, sparkling for ever, in the eyes of

posterity. A common meadow is a sorry

thing to a ditcher or a coxcomb; but by the

help of its dues from imagination and the

love of nature, the grass brightens for us,

the air soothes us, we feel as we did in the

daisied hours of childhood. Its verdures,

its sheep, its hedge-row elms,—all these,

and all else which sight, and sound, and

association can give it, are made to furnish

a treasure of pleasant thoughts. Even

brick and mortar are vivified, as of old at

the harp of Orpheus. A metropolis becomes

no longer a mere collection of houses

or of trades. It puts on all the grandeur

of its history, and its literature; its towers,

and rivers; its art, and jewellery, and

foreign wealth; its multitude of human

beings all intent upon excitement, wise or

yet to learn; the huge and sullen dignity

of its canopy of smoke by day; the wide

gleam upwards of its lighted lustre at night-time;

and the noise of its many chariots,

heard, at the same hour, when the wind sets

gently towards some quiet suburb.—Leigh

Hunt.

Actors.

Madame Rollan, who died in 1785, in

the seventy-fifth year of her age, was a

principal dancer on Covent-garden stage in

[I-17,

I-18]

1731, and followed her profession, by private

teaching, to the last year of her life.

She had so much celebrity in her day, that

having one evening sprained her ancle, no

less an actor than Quin was ordered by the

manager to make an apology to the audience

for her not appearing in the dance.

Quin, who looked upon all dancers as “the

mere garnish of the stage,” at first demurred;

but being threatened with a forfeiture,

he growlingly came forward, and in

his coarse way thus addressed the audience:

“Ladies and Gentlemen,

“I am desired by the manager to inform

you, that the dance intended for this night

is obliged to be postponed, on account of

mademoiselle Rollan having dislocated her

ancle: I wish it had been her neck.”

In Quin’s time Hippesley was the Roscius

of low comedy; he had a large scar on his

cheek, occasioned by being dropped into

the fire, by a careless nurse, when an infant,

which gave a very whimsical cast to

his features. Conversing with Quin concerning

his son, he told him, he had some

thoughts of bringing him on the stage.

“Oh,” replied the cynic, “if that is your

intention, I think it is high time you should

burn his face.”

On one of the first nights of the opera

of Cymon at Drury-lane theatre, when the

late Mr. Vernon began the last air in the

fourth act, which runs,

“Torn from me, torn from me, which way did they take her?”

a dissatisfied musical critic immediately

answered the actor’s interrogation in the

following words, and to the great astonishment

of the audience, in the exact tune of

the air,

“Why towards Long-acre, towards Long-acre.”

This unexpected circumstance naturally

embarrassed poor Vernon, but in a moment

recovering himself, he sung in rejoinder,

the following words, instead of the author’s:

“Ho, ho, did they so,

Then I’ll soon overtake her,

Then I’ll soon overtake her.”

Vernon then precipitately made his exit

amidst the plaudits of the whole house.

Home Department.

Potatoes.

If potatoes, how much soever frosted,

be only carefully excluded from the atmospheric

air, and the pit not opened until

some time after the frost has entirely subsided,

they will be found not to have sustained

the slightest injury. This is on

account of their not having been exposed

to a sudden change, and thawing gradually.

A person inspecting his potato heap,

which had been covered with turf, found

them so frozen, that, on being moved, they

rattled like stones: he deemed them irrecoverably

lost, and, replacing the turf, left

them, as he thought, to their fate. He

was not less surprised than pleased, a considerable

time afterwards, when he discovered

that his potatoes, which he had given

up for lost, had not suffered the least detriment,

but were, in all respects, remarkably

fine, except a few near the spot which

had been uncovered. If farmers keep their

heaps covered till the frost entirely disappears,

they will find their patience amply

rewarded.

London.

Lost Children.

The Gresham committee having humanely

provided a means of leading to the discovery

of lost or strayed children, the following

is a copy of the bill, issued in consequence

of their regulation:—

To the Public.

London.

If persons who may have lost a child, or

found one, in the streets, will go with a

written notice to the Royal Exchange, they

will find boards fixed up near the medicine

shop, for the purpose of posting up such

notices, (free of expense.) By fixing their

notice at this place, it is probable the

child will be restored to its afflicted parents

on the same day it may have been missed.

The children, of course, are to be taken

care of in the parish where they are found

until their homes are discovered.

From the success which has, within a

short time, been found to result from the

immediate posting up notices of this sort,

there can be little doubt, when the knowledge

of the above-mentioned boards is

general, but that many children will be

speedily restored. It is recommended that

a bellman be sent round the neighbourhood,

as heretofore has been usually done.

Persons on receiving this paper are requested

to fix it up in their shop-window,

or other conspicuous place.

The managers of Spa-fields chapel

improving upon the above hint, caused

[I-19,

I-20]

a board to be placed in front of their chapel

for the same purpose, and printed bills which

can be very soon filled up, describing the

child lost or found, in the following

forms:—

| CHILD LOST. |

CHILD FOUND. |

| Sex |

Age |

Sex |

Age |

| Name |

Name |

| Residence |

May be heard of at |

| Further particulars |

Further particulars |

The severe affliction many parents suffer

by the loss of young children, should induce

parish officers, and others, in populous

neighbourhoods, to adopt a plan so

well devised to facilitate the restoration of

strayed children.

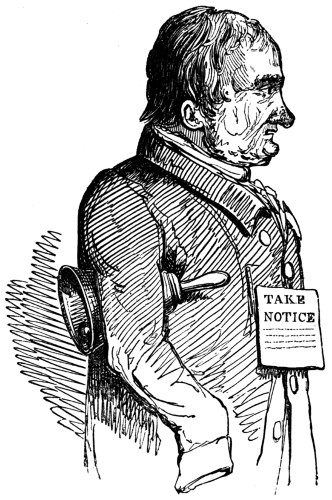

Ticket Porters.

By an Act of common council of the city

of London, Heygate, mayor, 1823, the

ticket porters are not to exceed five hundred.

A ticket porter, when plying or working,

is to wear his ticket so as to be plainly

seen, under a penalty of 2s. 6d. for each

offence.

No ticket porter is to apply for hire in

any place but on the stand, appointed by

the acts of common council, or within six

yards thereof, under a penalty of 5s.

| FARES OF TICKET-PORTERS. |

For

every

half

mile

farther. |

| |

Qr.

Mile. |

Half

Mile. |

One

Mile. |

11⁄2

Mile. |

Two

Mile. |

| s. |

d. |

s. |

d. |

s. |

d. |

s. |

d. |

s. |

d. |

s. |

d. |

| For any Package, Letter, &c. not exceeding 56 lbs. |

0 |

4 |

0 |

6 |

0 |

9 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

0 |

6 |

| Above 56 lbs. and not exceeding 112 lbs. |

0 |

6 |

0 |

9 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

0 |

9 |

| Above 112 lbs. and not exceeding 168 lbs. |

0 |

8 |

1 |

0 |

1 |

6 |

2 |

0 |

2 |

6 |

1 |

0 |

| For every parcel above 14 lbs. which they may have to

bring back, they are allowed half the above fares. |

A ticket porter not to take more than one

job at a time, penalty 2s. 6d.

Seven, or more, rulers of the society, to

constitute a court.

The governor of the society, with the

court of rulers, to make regulations, and

annex reasonable penalties for the breach

thereof, not exceeding 20s. for each offence,

or three months’ suspension. They may discharge

porters who persist in breach of

their orders.

The court of rulers to hear and determine

complaints in absence of the governor.

Any porter charging more than his regular

fare, finable on conviction to the

extent of 20s., by the governor, or the court

of rulers.

Persons employing any one within the

city, except their own servants or ticket

porters, are liable to be prosecuted.

Manners.

Oliver Cromwell.

The following is an extract from one of

Richard Symons’s Pocket-books, preserved

amongst the Harleian MSS. in the British

Museum, No. 991. “At the marriage of

his daughter to Rich, in Nov. 1657, the

lord protector threw about sack-posset

among all the ladyes to soyle their rich

cloaths, which they tooke as a favour, and

also wett sweetmeats; and daubed all the

stooles where they were to sit with wett

sweetmeats; and pulled off Rich his peruque,

and would have thrown it into the

fire, but did not, yet he sate upon it.”

Old Women.

De Foe remarks in his “Protestant

Monastery,” that “If any whimsical or

ridiculous story is told, ’tis of an Old Woman.

If any person is awkward at his

business or any thing else, he is called an

Old Woman forsooth. Those were brave

days for young people, when they could

swear the old ones out of their lives, and

get a woman hanged or burnt only for

being a little too old—and, as a warning

to all ancient persons, who should dare to

live longer than the young ones think convenient.”

Duel with a Bag.

Two gentlemen, one a Spaniard, and

the other a German, who were recommended,

[I-21,

I-22]

by their birth and services, to

the emperor Maximilian II., both courted

his daughter, the fair Helene Scharfequinn,

in marriage. This prince, after

a long delay, one day informed them,

that esteeming them equally, and not being

able to bestow a preference, he should

leave it to the force and address of the

claimants to decide the question. He did

not mean, however, to risk the loss of one

or the other, or perhaps of both. He

could not, therefore, permit them to encounter

with offensive weapons, but had

ordered a large bag to be produced. It

was his decree, that whichever succeeded

in putting his rival into this bag should

obtain the hand of his daughter. This

singular encounter between the two gentlemen

took place in the face of the whole

court. The contest lasted for more than an

hour. At length the Spaniard yielded, and

the German, Ehberhard, baron de Talbert,

having planted his rival in the bag, took it

upon his back, and very gallantly laid it at

the feet of his mistress, whom he espoused

the next day.

Such is the story, as gravely told by M.

de St. Foix. It is impossible to say what

the feelings of a successful combatant in a

duel may be, on his having passed a small

sword through the body, or a bullet through

the thorax, of his antagonist; but might

he not feel quite as elated, and more consoled,

on having put his adversary “into a

bag?”

“A New Matrimonial Plan.”

This is the title of a bill printed and distributed

four or five years ago, and now

before me, advertising “an establishment

where persons of all classes, who are anxious

to sweeten life, by repairing to the altar of

Hymen, have an opportunity of meeting

with proper partners.” The “plan” says,

“their personal attendance is not absolutely

necessary, a statement of facts is all

that is required at first.” The method is

simply this, for the parties to become subscribers,

the amount to be regulated according

to circumstances, and that they

should be arranged in classes in the following

order, viz.

“Ladies.

“1st Class. I am twenty years of age,

heiress to an estate in the county

of Essex of the value of 30,000l.,

well educated, and of domestic

habits; of an agreeable, lively disposition

and genteel figure. Religion

that of my future husband.

“2d Class. I am thirty years of age, a

widow, in the grocery line in

London—have children; of

middle stature, full made, fair

complexion and hair, temper

agreeable, worth 3,000l.

“3d Class. I am tall and thin, a little

lame in the hip, of a lively disposition,

conversable, twenty years

of age, live with my father, who,

if I marry with his consent, will

give me 1,000l.

“4th Class. I am twenty years of age; mild

disposition and manners; allowed

to be personable.

“5th Class. I am sixty years of age; income

limited; active, and rather

agreeable.

“Gentlemen.

“1st Class. A young gentleman with dark

eyes and hair; stout made; well

educated; have an estate of 500l.

per annum in the county of Kent;

besides 10,000l. in the three per

cent. consolidated annuities; am

of an affable disposition, and very

affectionate.

“2d Class. I am forty years of age, tall

and slender, fair complexion and

hair, well tempered and of sober

habits, have a situation in the

Excise of 300l. per annum, and a

small estate in Wales of the annual

value of 150l.

“3d Class. A tradesman in the city of

Bristol, in a ready-money business,

turning 150l. per week, at

a profit of 10l. per cent., pretty

well tempered, lively, and fond

of home.

“4th Class. I am fifty-eight years of age;

a widower, without incumbrance;

retired from business upon a

small income; healthy constitution;

and of domestic habits.

“5th Class. I am twenty-five years of age;

a mechanic, of sober habits; industrious,

and of respectable connections.

“It is presumed that the public will not

find any difficulty in describing themselves;

if they should, they will have the assistance

of the managers, who will be in attendance

at the office, No. 5, Great St. Helen’s,

Bishopgate-street, on Mondays, Wednesdays,

and Fridays, between the hours of

eleven and three o’clock.—Please to inquire

for Mr. Jameson, up one pair of

stairs. All letters to be post paid.

“The subscribers are to be furnished

[I-23,

I-24]

with a list of descriptions, and when one

occurs likely to suit, the parties may correspond;

and if mutually approved, the

interview may be afterwards arranged.

Further particulars may be had as above.”

Such a strange device in our own time,

for catching would-be lovers, seems incredible,

and yet here is the printed plan, with

the name and address of the match-making

gentleman you are to inquire for “up one

pair of stairs.”

Topographical Memoranda.

Clerical Longevity.

The following is an authentic account,

from the “Antiquarian Repertory,” of the

incumbents of a vicarage near Bridgenorth

in Shropshire. Its annual revenue, till the

death of the last incumbent here mentioned,

was not more than about seventy pounds

per annum, although it is a very large and

populous parish, containing at least twenty

hamlets or townships, and is scarcely any

where less than four or five miles in diameter.

By a peculiar idiom in that country,

the inhabitants of this large district are

said to live “in Worfield-home:” and the

adjacent, or not far distant, parishes (each

of them containing, in like manner, many

townships, or hamlets) are called Claverly,

or Clarely-home, Tatnall-home, Womburn-home,

or, as the terminating word is every

where pronounced in that neighbourhood,

“whome.”

“A list of the vicars of Worfield in the

diocese of Lichfield and Coventry, and in the

county of Salop, from 1564 to 1763, viz.

“Demerick, vicar, last popish priest, conformed

during the six first years of Elizabeth.

He died 1564.

| Barney, vicar |

44 years; died 1608. |

| Barney, vicar |

56 years; died 1664. |

| Hancocks, vicar |

42 years; died 1707. |

| Adamson, vicar |

56 years; died 1763. |

Only 4 vicars in 199 years.”

Spelling for a Wake.

Proclamation was made a few years ago,

at Tewkesbury, from a written paper, of

which the following is a copy:—

“Hobnail’s Wake—This his to give

notis on Tusday next—a Hat to be playd

at bac sord fore. Two Belts to be tuseld

fore. A plum cack to be gump in bags

fowr. A pond of backer to be bold for,

and a showl to danc lot by wimen.”

THE BEAUTIES OF SOMERSET.

A BALLAD.

I’m a Zummerzetzhire man,

Zhew me better if you can,

In the North, Zouth, East, or West;

I waz born in Taunton Dean,

Of all places ever seen

The richest and the best.

Old Ballad

Tune, Alley Croker.

That Britain’s like a precious gem

Set in the silver ocean,

Our Shakspeare sung, and none condemn

Whilst most approve the notion,—

But various parts, we now declare,

Shine forth in various splendour,

And those bright beams that shine most fair,

The western portions render;—

O the counties, the matchless western counties,

But far the best,

Of all the rest,

Is Somerset for ever.

For come with me, and we’ll survey

Our hills and vallies over,

Our vales, where clear brooks bubbling stray

Through meads of blooming clover;

Our hills, that rise in giant pride,

With hollow dells between them,

Whose sable forests, spreading wide,

Enrapture all who’ve seen them;

O the counties, &c.

How could I here forgetful be

Of all your scenes romantic,

Our rugged rocks, our swelling sea,

Where foams the wild Atlantic!

There’s not an Eden known to men

That claims such admiration,

As lovely Culbone’s peaceful glen,

The Tempe of the nation;

O the counties, &c.

To name each beauty in my rhyme

Would prove a vain endeavour,

I’ll therefore sing that cloudless clime

Where Summer sets for ever;

Where ever dwells the Age of Gold

In fertile vales and sunny,

Which, like the promis’d land of old,

O’erflows with milk and honey;

O the counties, &c.

But O! to crown my county’s worth,

What all the rest surpasses,

There’s not a spot in all the earth

Can boast such lovely lasses;

There’s not a spot beneath the sun

Where hearts are open’d wider.

Then let us toast them every one,

In bowls of native cider;

O the counties, &c.

[I-25,

I-26]

Weather.

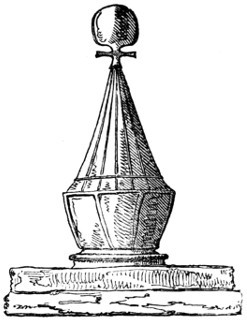

A new Hygrometer.

A new instrument to measure the degrees

of moisture in the atmosphere, of

which the following is a description, was

invented by M. Baptist Lendi, of St. Gall:

In a white flint bottle is suspended a

piece of metal, about the size of a hazle

nut, which not only looks extremely beautiful,

and contributes to the ornament of a

room, but likewise predicts every possible

change of weather twelve or fourteen hours

before it occurs. As soon as the metal is

suspended in the bottle with water, it

begins to increase in bulk, and in ten or

twelve days forms an admirable pyramid,

which resembles polished brass; and it

undergoes several changes, till it has attained

its full dimensions. In rainy weather,

this pyramid is constantly covered

with pearly drops of water; in case of

thunder or hail, it will change to the finest

red, and throw out rays; in case of wind

or fog, it will appear dull and spotted;

and previously to snow, it will look quite

muddy. If placed in a moderate temperature,

it will require no other trouble than

to pour out a common tumbler full of

water, and to put in the same quantity of

fresh. For the first few days it must not

be shaken.

Omniana.

Calico Company.

A red kitten was sent to the house of a

linen-draper in the city; and, on departing

from the maternal basket, the following

lines were written:—

The Red Kitten.

O the red red kitten is sent away,

No more on parlour hearth to play;

He must live in the draper’s house,

And chase the rat, and catch the mouse,

And all day long in silence go

Through bales of cotton and calico.

After the king of England fam’d,

The red red kitten was Rufus nam’d.

And as king Rufus sported through

Thicket and brake of the Forest New,

The red red kitten Rufus so

Shall jump about the calico.

But as king Rufus chas’d the deer,

And hunted the forest far and near,

Until as he watch’d the jumpy squirrel,

He was shot by Walter Tyrrel;

So, if Fate shall his death ordain,

Shall kitten Rufus by dogs be slain,

And end his thrice three lives of woe

Among the cotton and calico.

Twelfth-Day

SONNET

TO A PRETTY GIRL IN

A PASTRY-COOK’S

SHOP.

Sweet Maid, for thou art maid of many sweets,

Behind thy counter, lo! I see thee standing,

Gaz’d at by wanton wand’rers in the streets,

While cakes, to cakes, thy pretty fist is handing.

Light as a puff appears thy every motion,

Yet thy replies I’ve heard are sometimes tart;

I deem thee a preserve, yet I’ve a notion

That warm as brandied cherries is thy heart.

Then be not to thy lover like an ice,

Nor sour as raspberry vinegar to one

Who owns thee for a sugar-plum so nice,

Nicer than comfit, syllabub, or bun.

I love thee more than all the girls so natty,

I do, indeed, my sweet, my savoury Patty.

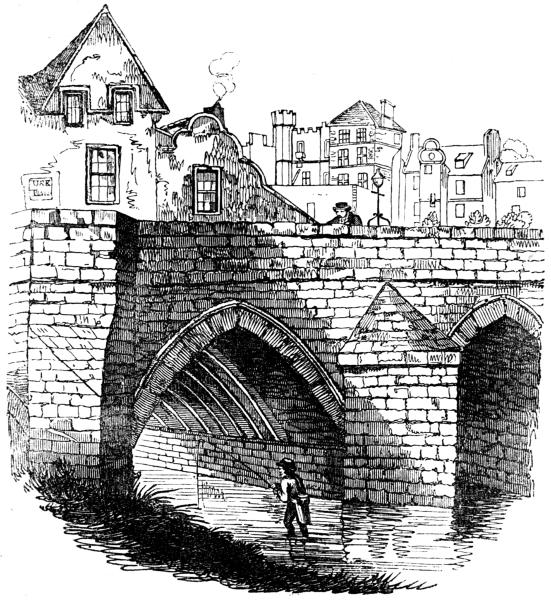

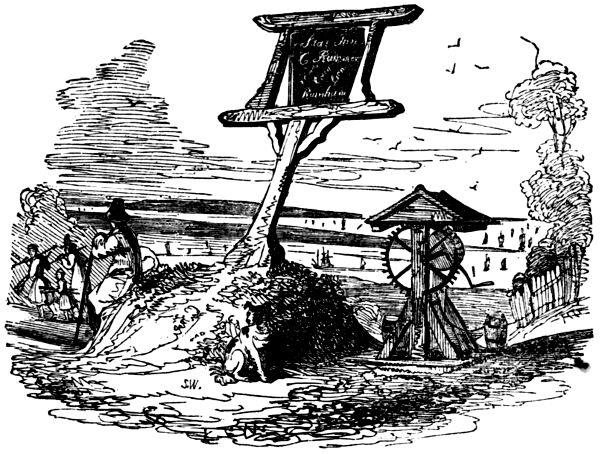

“Holly Night” at Brough.

For the Table Book.

The ancient custom of carrying the

“holly tree” on Twelfth Night, at Brough

in Westmoreland, is represented in the accompanying

engraving.

Formerly the “Holly-tree” at Brough was

really “holly,” but ash being abundant,

the latter is now substituted. There are

two head inns in the town; which provide

for the ceremony alternately, though the

good townspeople mostly lend their assistance

in preparing the tree, to every branch

of which they fasten a torch. About eight

o’clock in the evening, it is taken to a convenient

part of the town, where the torches

are lighted, the town band accompanying

and playing till all is completed, when

it is removed to the lower end of the town;

and, after divers salutes and huzzas from

the spectators, is carried up and down the

town, in stately procession, usually by a

person of renowned strength, named Joseph

Ling. The band march behind it, playing

their instruments, and stopping every

time they reach the town bridge, and the

cross, where the “holly” is again greeted

with shouts of applause. Many of the inhabitants

carry lighted branches and flambeaus;

and rockets, squibs, &c. are discharged

on the joyful occasion. After the

tree is thus carried, and the torches are

sufficiently burnt, it is placed in the middle

of the town, when it is again cheered by

the surrounding populace, and is afterwards

thrown among them. They eagerly watch

for this opportunity; and, clinging to each

end of the tree, endeavour to carry it away

to the inn they are contending for, where

they are allowed their usual quantum of

ale and spirits, and pass a “merry night,”

which seldom breaks up before two in the

morning.

[I-27,

I-28]

Carrying the “Holly Tree” at Brough, Westmoreland.

To every branch a torch they tie,

To every torch a light apply;

At each new light send forth huzzas

Till all the tree is in a blaze;

And then bear it flaming through the town,

With minstrelsy, and rockets thrown.

Although the origin of this usage is lost,

and no tradition exists by which it can be

traced, yet it may not be a strained surmise

to derive it from the church ceremony of

the day when branches of trees were carried

in procession to decorate the altars, in commemoration

of the offerings of the Magi,

whose names are handed down to us as

Melchior, Gaspar, and Balthasar, the patrons

of travellers. In catholic countries,

flambeaus and torches always abound in

their ceremonies; and persons residing in

the streets through which they pass, testify

their zeal and piety by providing flambeaus

at their own expense, and bringing them

lighted to the doors of their houses.

W. H. H.

Note.

Communications for the Table Book addressed to

me, in a parcel, or under cover, to the care of the publishers,

will be gladly received.

Notices to Correspondents will appear on the

wrappers of the monthly parts only.

The Table Book, therefore, after the present sheet,

will be printed continuously, without matter of this

kind, or the intervention of temporary titles, unpleasant

to the eye, when the work comes to be bound in

volumes.

Lastly, because this is the last opportunity of the

kind in my power, I beg to add that some valuable

papers which could not be included in the Every-Day

Book, will appear in the Table Book.

Moreover Lastly, I earnestly solicit the immediate

activity of my friends, to oblige and serve me, by

sending any thing, and every thing they can collect or

recollect, which they may suppose at all likely to render

my Table Book instructive, or diverting.

W. Hone.

[I-29,

I-30]

Vol. I.—2.

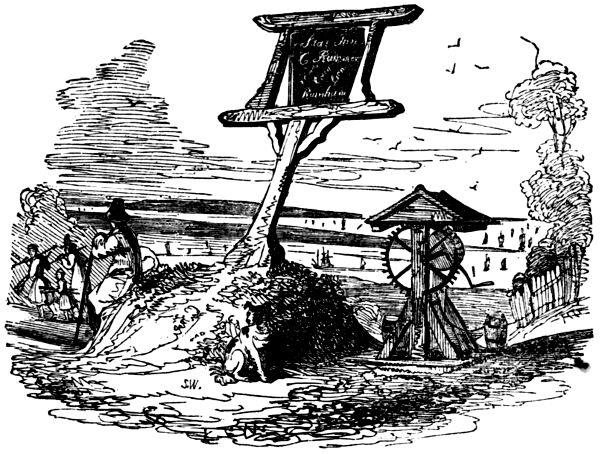

Emigration of the Deer from Cranbourn Chase, 1826.

Emigration of the Deer from Cranbourn Chase, 1826

The genial years increase the timid herd

Till wood and pasture yield a scant supply;

Then troop the deer, as at a signal word,

And in long lines o’er barren downs they hie,

In search what food far vallies may afford—

Less fearing man, their ancient enemy,

Than in their native chase to starve and die.

[I-31,

I-32]

The deer of Cranbourn chase usually

average about ten thousand in number. In

the winter of 1826, they were presumed to

amount to from twelve to fifteen thousand.

This increase is ascribed to the unusual

mildness of recent winters, and the consequent

absence of injuries which the animals

are subject to from severe weather.

In the month of November, a great

number of deer from the woods and pastures

of the Chase, between Gunvile and

Ashmore, crossed the narrow downs on the

western side, and descended into the adjacent

parts of the vale of Blackmore in

quest of subsistence. There was a large

increase in the number about twelve years

preceding, till the continued deficiency of

food occasioned a mortality. Very soon

afterwards, however, they again increased

and emigrated for food to the vallies, as in

the present instance. At the former period,

the greater part were not allowed or were

unable to return.

The tendency of deer to breed beyond

the means of support, afforded by parks

and other places wherein they are kept,

has been usually regulated by converting

them into venison. This is clearly more

humane than suffering the herds so to enlarge,

that there is scarcely for “every one

a mouthfull, and no one a bellyfull.” It is

also better to pay a good price for good

venison in season, than to have poor and

cheap venison from the surplus of starving

animals “killed off” in mercy to the remainder,

or in compliance with the wishes

of landholders whose grounds they invade

in their extremity.

The emigration of the deer from Cranbourn

Chase suggests, that as such cases

arise in winter, their venison may be bestowed

with advantage on labourers, who

abound more in children than in the means

of providing for them; and thus the surplus

of the forest-breed be applied to the

support and comfort of impoverished human

beings.

Cranbourn.

Cranbourn is a market town and parish in

the hundred of Cranbourn, Dorsetshire, about

12 miles south-west from Salisbury, and 93

from London. According to the last census,

it contains 367 houses and 1823 inhabitants,

of whom 104 are returned as being employed

in trade. The parish includes a

circuit of 40 miles, and the town is pleasantly

situated in a fine champaign country

at the north-east extremity of the county,

near Cranbourn Chase, which extends

almost to Salisbury. Its market is on a

Thursday, it has a cattle market in the

spring, and its fairs are on St. Bartholomew’s

and St. Nicholas’ days. It is the capital of

the hundred to which it gives its name, and

is a vicarage valued in the king’s books at

£6. 13s. 4d. It is a place of high antiquity,

famous in the Saxon and Norman times for

its monastery, its chase, and its lords. The

monastery belonged to the Benedictines, of

which the church at the west end of the

town was the priory.[8]

Affray in the Chase.

On the night of the 16th of December,

1780, a severe battle was fought between

the keepers and deer-stealers on Chettle

Common, in Bursey-stool Walk. The deer-stealers

had assembled at Pimperne, and

were headed by one Blandford, a sergeant

of dragoons, a native of Pimperne, then

quartered at Blandford. They came in the

night in disguise, armed with deadly offensive

weapons called swindgels, resembling

flails to thresh corn. They attacked the

keepers, who were nearly equal in number,

but had no weapons but sticks and short

hangers. The first blow was struck by the

leader of the gang, it broke a knee-cap of

the stoutest man in the chase, which disabled

him from joining in the combat, and

lamed him for ever. Another keeper, from

a blow with a swindgel, which broke three

ribs, died some time after. The remaining

keepers closed in upon their opponents

with their hangers, and one of the dragoon’s

hands was severed from the arm,

just above the wrist, and fell on the ground;

the others were also dreadfully cut and

wounded, and obliged to surrender. Blandford’s

arm was tightly bound with a list

garter to prevent its bleeding, and he was

carried to the lodge. The Rev. William

Chafin, the author of “Anecdotes respecting

Cranbourn Chase,” says, “I saw

him there the next day, and his hand

in the window: as soon as he was well

enough to be removed, he was committed,

with his companions, to Dorchester gaol.

The hand was buried in Pimperne church-yard,

and, as reported, with the honours

of war. Several of these offenders

were labourers, daily employed by Mr.

Beckford, and had, the preceding day,

dined in his servants’ hall, and from thence

went to join a confederacy to rob their

master.” They were all tried, found guilty

and condemned to be transported for seven

years; but, in consideration of their great

[I-33,

I-34]

suffering from their wounds in prison, the

humane judge, sir Richard Perryn, commuted

the punishment to confinement for an

indefinite term. The soldier was not dismissed

from his majesty’s service, but suffered

to retire upon half-pay, or pension;