The Project Gutenberg EBook of History of the Fifty-Seventh Regiment,

Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at

www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll

have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using

this ebook.

Title: History of the Fifty-Seventh Regiment, Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteer Infantry

First Brigade, First Division, Third Corps and Second

Brigade, Third Division, Second Corps, Army of the Potomac

Author: Various

Release Date: November 20, 2018 [EBook #58315]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

*** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK HISTORY OF THE FIFTY-SEVENTH ***

Produced by David King and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net. (This file was

produced from images generously made available by The

Internet Archive.)

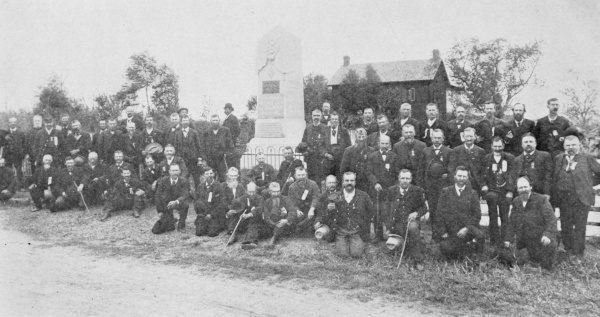

Monument of 57th Pa. Vet. Vols., at Sherfy's house on the battlefield of Gettysburg.

Chapter I. 9

Organization of the Regiment—Camp Curtin—Departure for Washington—In Old Virginia—Colonel Maxwell Resigns—Colonel Campbell

Chapter II. 18

We Embark for the Peninsula—Yorktown—Camping in the Mud—Peach Orchard—Artillery Practice—Battle of Williamsburg

Chapter III. 29

Battle of Fair Oaks—Death of Major Culp—Increasing Sick List—Advancing Our Lines—The Seven Days' Battles—Glendale or Charles City Cross Roads—The Fifty-Seventh Under Captain Maxwell as Rear Guard—Malvern Hill—Retreat to Harrison's Landing

Chapter IV. 43

Camp Life at Harrison's Landing—Major Birney Assigned to the Command of the Regiment—Transferred to General Birney's Brigade—Evacuation of Harrison's Landing and the Peninsula—The Army of the Potomac is Sent to Reenforce General Pope

Chapter V. 53

Second Bull Run Campaign—Battle of Chantilly—Death of General Kearny—His Body Escorted to Washington by a Detachment of the Fifty-Seventh—Retreat to Alexandria—Conrad's Ferry—Colonel Campbell Rejoins the Regiment

Chapter VI. 61

On to Richmond Once More—Foragers Captured—General McClellan Superseded by General Burnside—The March to the Rappahannock—Battle of Fredericksburg

Chapter VII. 69

Camp Pitcher—The "Mud March"—General Hooker in Command of the Army—Resolutions Adopted by the Fifty-Seventh—Re-assignment to the First Brigade—Anecdote of Colonel Campbell—Drill and Inspection—Adoption of Corps Badges—The Chancellorsville Campaign—Jackson Routs the Eleventh Corps—A "Flying Dutchman"—In a Tight Place—General Hooker Disabled—General Sedgwick's Movements—A New Line Established—Strength of the Fifty-Seventh and Its Losses

Chapter VIII. 82

Back Again in Our Old Camp—Cavalry Battle at Brandy Station—The March to Gettysburg—Hooker's Request for Troops at Harper's Ferry—Asks to be Relieved from the Command of the Army—We Arrive at Gettysburg—Battle of July 2d—Strength of the Fifty-Seventh—Its Losses—General Graham Wounded and Captured—Wounding of General Sickles—Battle of July 3d—July 4th—The Confederates Retreat—General Sickles Asks for a Court of Inquiry—President Lincoln to Sickles—A Visit to the Battlefield Twenty-five Years Later

Chapter IX. 95

We Leave Gettysburg—Rebel Spy Hung—French's Division Joins the 3d Corps—Enemy's Position at Falling Waters—He Escapes Across the Potomac—In Old Virginia Again—Manassas Gap—Camp at Sulphur Springs—Movement to Culpepper—Eleventh and Twelfth Corps Sent West—Lee's Efforts to Gain Our Rear—Skirmish at Auburn Creek—Warren's Fight at Bristow Station—Deserter Shot—Retreat of the Enemy—Kelly's Ford—Mine Run Campaign—The Regiment Re-enlists—The "Veteran Furlough"—Recruiting—Presented with a New Flag by Governor Curtin—Back to the Front—General Grant Commands the Army—Reorganization—The Wilderness Campaign—Three Days of Hard Fighting—Loss in Fifty-Seventh

Chapter X. 111

The Movement to Spottsylvania Court House—General Sedgwick Killed—Hancock's Grand Charge of May 12th—Great Capture of Prisoners, Guns and Colors—The Famous Oak Tree—Ewell's Effort to Capture Our Wagon Train—Losses in the Fifty-Seventh at Spottsylvania—Movement to North Anna River—Fight at Chesterfield Ford—We Cross the Pamunkey—Skirmish at Haw's Shop and Totopotomoy Creek—Battle of Cold Harbor—Our Colors Struck and Badly Torn by a Piece of Shell—Flank Movement to the James River—March to Petersburg—Severe Fighting at Hare's Hill—Battle of June 22d—Losses in the Fifty-Seventh—Fort Alex. Hays—Petersburg—We Move to the North Side of the James—Strawberry Plains—Return to Petersburg—The "Burnside Mine"—General Mott in Command of Our Division—Deep Bottom—Other Marching and Fighting Around Petersburg

Chapter XI. 126

Recruits—Dangerous Picket Duty—Muster-out of Old Regiments—Composition of the Brigade—Expedition Against the South Side Railroad—Battle of Boydton Plank Road or Hatcher's Run—Disguised Rebels Capture Our Picket Line—Election Day—Thanksgiving Dinner of Roast Turkey—Change of Camp—Raid on Weldon Railroad—A Hard March Returning—"Applejack"—General Humphreys in Command of the Second Corps

Chapter XII. 138

Disbanding of Companies A and E—Regiment Organized Into a Battalion of Six Companies—Consolidation of the Eighty-Fourth with the Fifty-Seventh Pennsylvania—Necessity for Changing the Letter of Some of the Companies—Confusion in Company Rolls Growing Out of It—Officers of the Consolidated Regiment—Another Move Across Hatcher's Run—The Regiment Again Engaged with the Enemy—Great Length of the Line in Front of Petersburg—A Lively Picket Skirmish—Battle Near Watkin's House—Enemy's Picket Line and Many Prisoners Captured

Chapter XIII. 147

Beginning of Our Last Campaign—Battle of Five Forks—On Picket Duty on Old Hatcher's Run Battlefield—Jubilant Rebels—Enemy's Lines Broken—Petersburg and Richmond Evacuated—In Pursuit of the Enemy—Battle of Sailor's Creek—High Bridge—General Mott Wounded—Lee's Army Breaking Up—Appomattox—Joy Over the Surrender—On the Backward March—Camp at Burkesville Junction

Chapter XIV. 157

Departure from Burkesville—Marching Through Richmond—The March to Washington—Passing Over Old Battlefields—Camp at Bailey's Cross Roads—Grand Review of the Army of the Potomac—The Order of March—The Fifty-Seventh Ordered Mustered Out—Names of Engagements in which the Regiment Participated—Its Casualties—We Start for Harrisburg—Finally Paid and Discharged—Farewell Address of Our Field Officers

Appendix A.—Roster of Officers 164

Appendix B.—Medical Report of Surgeon Lyman for year 1862 170

Appendix C.—Address of Lieut.-Col. L. D. Bumpus at the Dedication of the Regimental Monument at Gettysburg, July 2d, 1888 176

Appendix D.—Reminiscences of the Fifty-Seventh Regiment by Gen. William Birney 190

When the idea of publishing the History of the Fifty-Seventh Pennsylvania Veteran Volunteers was first conceived and a committee appointed to prepare the manuscript for the same, the chief difficulty to be met with was to confine the limits of the work to such a size that the price of the book would be such that it might be placed within the means of all the survivors of the regiment.

The committee regrets that the muster-out rolls of the regiment were not accessible, nor could they be copied from the rolls at Washington, D. C.

Even if the rolls could have been copied and published in the book, it would have greatly added to the price of the work and would have required a much greater fund than the committee had on hand for that purpose.

A great deal of pains have been taken and the marches, campaigns and battles of the regiment have been carefully studied, and it is to be hoped that they will be found to be accurately described.

If the labor of the committee will meet the approval of those who have marched and fought with the gallant old regiment, it will be duly appreciated by those compiling the work.

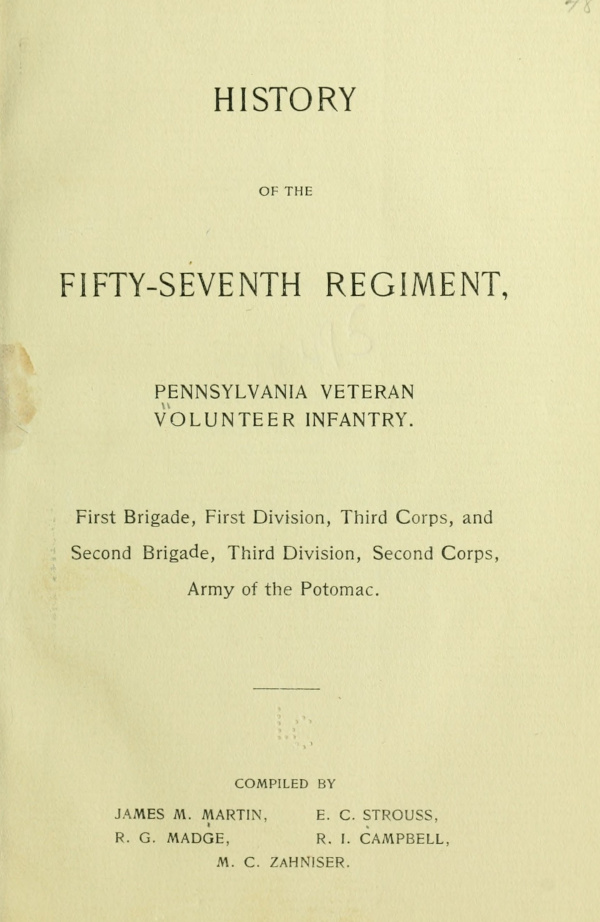

The Historical Committee

Organization of the Regiment—Camp Curtin—Departure for Washington—In Old Virginia—Colonel Maxwell Resigns—Colonel Campbell.

The sanguinary battle, and almost disgraceful rout of the Union army under General McDowell at the first Bull Run in July, 1861, convinced the authorities at Washington that the insurrection of the slave states was not a mere spasm of anger at their defeat in the preceding presidential election to be crushed out by the levy of 75,000 troops, undisciplined and indifferently equipped, in a three months' service of holiday soldiering, and that Secretary Seward's prophecy that a sixty days' campaign would restore the Union and bring peace to the nation was a dream destined not to be realized. Acting on this conviction a call was made for 300,000 volunteers to serve for three years, or during the war.

To meet the emergency, evident to many, who were not disposed to accept the prophecy of the Secretary of State, Andrew G. Curtin, whose name will go down in history as "Pennsylvania's War Governor," organized, equipped and had put in training that superb body of men, "The Pennsylvania Reserves," who through all the four years of bloody conflict to follow, were to find the place their name indicated, on the skirmish and picket line, and in the front of the battle, were the first to respond, and none too quickly, for the safety of the Nation's Capital. In obedience to this call other regiments and battalions were promptly organized and forwarded so that by September 1, 1861, Arlington Heights and the environments of Washington were thickly studded with the camps of these new levies, and out of the mass was being moulded, under the hand of that skillful drill master, General George B. McClellan, that mighty host known in history as the Army of the Potomac, whose valiant deeds in the cause of Union and Liberty are co-eternal with that of the Nation.

At the first, regiments were recruited and mustered from single cities, towns and counties, but as time passed and the first flood of recruits were mustered into service, companies and squads, to the number of a corporal's guard, were gathered from distantly separated districts, and rendezvousing at some common camp were consolidated into regiments and battalions. Such was the case in the organization of the 57th Pennsylvania Volunteers, the place of rendezvous and final mustering being in Camp Curtin at the State Capital.

The roster of the regiment, by company, shows the different sections of the state whence recruited, viz:

Company A, Susquehanna and Wyoming counties.

Company B, Mercer county.

Company C, Mercer county.

Company D, Tioga county.

Company E, Allegheny, Mercer and Lawrence counties.

Company F, Mercer county.

Company G, Bradford county.

Company H, Bradford county.

Company I, Mercer and Venango counties.

Company K, Crawford county.

Thus it will be seen at a glance on the state map that there were representatives in the regiment from Wyoming county in the east; thence along the northern border of Crawford, Mercer, Venango and Lawrence counties in the extreme west. Before, however, the final rendezvous of these several companies at Camp Curtin there were smaller camps established for recruiting in several localities, notably that at Mercer, Mercer county, where it may be said was established the original regimental headquarters.

The Hon. William Maxwell, a graduate of West Point, but at that time pursuing the peaceful avocation of the practice of law in that county, was, about September 1, 1861, authorized by Governor Curtin to recruit a regiment for the service. With this in view he established a rendezvous camp outside of the borough limits of the town of Mercer, on North Pittsburg street, in a field given for that purpose by the late Hon. Samuel B. Griffith, and which was named in honor of the donor, "Camp Griffith." Here temporary barracks were erected and a regular system of camp duties inaugurated, and the usually quiet hamlet of Mercer became the scene of quite active military enthusiasm; the still breezes of the Neshannock being stirred by the beat of drums and shrill notes of fife. In two or three weeks after the establishing of this camp a large number of volunteers were recruited who formed the nucleus of what afterwards became Companies B, C, E, F and I, of the regiment. When the number of these recruits became sufficient for the formation of a battalion Colonel Maxwell transferred them to Camp Curtin. In making this transfer the men were taken in conveyances overland to the "Big Bend" on the Shenango and there embarked on a canal boat for Rochester, Beaver county, and thence by the only line of railway, the Pittsburg, Ft. Wayne & Chicago, to Pittsburg and Harrisburg. Along the way from Camp Griffith to the Ohio these recruits enjoyed a continual ovation; the last, alas! that many in that band ever received. At Pittsburg they were joined by others from Allegheny and a small contingent from the northeastern part of Lawrence county, who cast their fortunes with Company E.

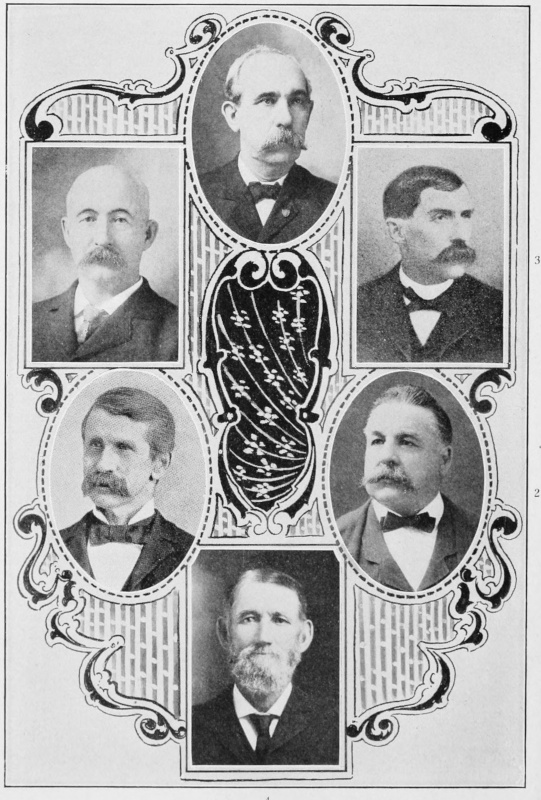

Col. William Maxwell

Arriving at Camp Curtin the regiment was rapidly filled up to the required ten companies by the addition of Companies A, D, G, H and K. In the latter part of October the regiment was organized and mustered into the United States service.

Immediately following the mustering, clothing was distributed, and stripped of every habiliment and insignia of the citizen and arrayed in forage caps, dark blue blouses, sky blue pants and army brogans the regiment marched to the armory in the city and received its equipment—Springfield muskets and cartridge boxes. An impressive ceremony, one not to be forgotten by those present, was the committing by Governor Curtin with appropriate words to the care of the regiment the colors:

Sacred emblem of our Union, in defense of which many who that day stood as stalwarts in those ranks, gave health, and limb, and life in the three years to follow.

Thus fully inducted into service the regiment settled down to the daily routine of camp duty, drill and guard mounting, waiting for the call to the more heroic service at the front beyond the Potomac.

To those accustomed to the dainties of the home table and unstinted in their access to the larder, the black coffee and indigestible sea biscuits, with the suggestive initials "B. C." stamped upon them, soon mollified their love of camp life and cultivated a craving desire to terminate the "cruel war" at the earliest date possible, even at the risk of being hurt or hurting somebody in the attempt.

During the month of November that destructive pest of the camp, measles, broke out in the regiment, and proved to many a foe more to be dreaded than the bullets of the enemy; besides, to go a soldiering in defense of one's country and be ambushed by a disease that at home was regarded as a trifling affliction of childhood, was a source of real humiliation.

About December 14th orders were received to transfer the regiment to Washington. The transfer was anything but a pleasure jaunt. Instead of the commodious and comfortable passenger coaches, the ordinary box freight cars were used, and packed in there, that cold December night of transfer was truly one of misery. The cars were seatless, consequently the Turkish style of sitting had to be adopted by all who did not prefer to stand or were so fortunate as to obtain a seat in the side doors from which the feet could swing with freedom. The night was exceedingly chilly and with no facilities for warmth the discomfort was at the maximum. The day following, the regiment arrived at Washington, where it was lodged for the night in the "Soldiers' retreat," the hard floors of which were as downy pillows to our wearied and cold stiffened limbs. The next day we marched out of the city, passing the Capitol, and formed camp near the Bladensburg road. It was now the dead of winter, a Washington winter, with frequent storms of rain, sleet and snow. The camp was on the lowlands and the regiment experienced to the full the disagreeableness of the mud and slush of "My Maryland." Here we had our first introduction to the Sibley tent, a species of canvas tepee of the western Indian pattern, each of which afforded shelter to a dozen men. A small sheet iron stove, with the pipe braced against the center pole, diffused warmth, while a hole in the canvas at the apex afforded an exit for the pungent smoke of the green pine used for fuel.

It was while in camp at this place we first heard the booming of the enemy's guns away to the westward across the Potomac. These deep notes were of such frequent recurrence that all were fully convinced that a battle was in progress. Steed-like "we snuffed the battle from afar," and many were the expressed fears that victory would perch upon our banners, and the war be ended ere we should reach the Virginia shores.

Alas! poor, ignorant mortals that we were! Little dreaming of what scenes of carnage and hot battle we should be called to witness before the last notes of the hostile guns should be heard. The next morning the papers brought us the news of the battle of Dranesville and the repulse of the enemy, and our sorrow was deep and loud spoken, that we were not forwarded and permitted, at once, to put an end to this southern fracas! Such was our confidence of easy victory!

While in this camp the measles again broke out in the regiment. Many of the men had contracted severe colds during that night of dismal ride from Harrisburg, and cases of pneumonia were numerous, many proving fatal, while others lingered for months in hospitals, either to be discharged on account of disability or to again return to their companies mere wrecks of their former selves.

In February, 1862, the regiment broke camp, and crossing the Potomac, took its place in the left wing of the army near Fort Lyon, below Alexandria. Here in the organization of the army it was assigned to Jameson's brigade of Heintzelman's division, which later, upon the organization of the army corps, constituted the first brigade, first division, third corps, commanded respectively by Generals Jameson, Hamilton and Heintzelman, General Hamilton later being superseded in division command by that intrepid and fearless fighter, General Philip Kearny, whom the enemy dubbed with the uneuphoneous soubriquet of the "One Armed Devil." The brigade as then organized consisted of the 57th, 63d, 105th Pennsylvania regiments and the 87th New York, and from that date so long as the old Third corps existed these Pennsylvania regiments retained their place side by side. Our associations were most pleasant, many last friendships were formed, and the courage of each was ever held in highest esteem by the others.

On March 1st, Colonel Maxwell resigned his commission as colonel of the regiment and was succeeded by Colonel Charles T. Campbell. Colonel Campbell was by education and choice an artillerist, and had seen service on that arm in the Mexican war. He had had command of a battery of Pennsylvania artillery in the three months' service, and had been commissioned by Governor Curtin colonel of artillery and had recruited and organized the first Pennsylvania regiment of light artillery as part of the Pennsylvania Reserve Corps. When, however, the regiment entered the United States' service, such an organization was deemed impracticable and the regiment as a compact body was disbanded and the batteries assigned to the several corps. Thus Colonel Campbell found himself a colonel in commission without a command. But he was enlisted for the war and with uncomplaining patriotism he willingly took his place where duty called. At the first the members of the regiment were impressed with the thought that they had "caught a Tartar." Tall and commanding in figure, gruff voiced and with sanguinary hair and whiskers, the colonel did not give the impression of being a weakling, but it was not long until they began to realize that beneath the rough exterior there beat a considerate and tender heart and in the gruff voice there was a soft chord, and soon the name "Charley" was more frequently on the lips about the camp fires than the more stately title of "Colonel." These characteristics of the new commander were manifested in many acts that the men appreciated. He was always ready to take the rough side of soldier life and share privations with the rank and file, and at the end of a hard day's march he would lie down with only the heavens for a covering with any of the boys rather than ask a detail to erect his headquarter tents. And many a comrade can remember when on camp guard and the weather was threatening, hearing that gruff voice calling from his tent door: "Officer of the day, release the guards and send them into their quarters!"

Gen. Charles T. Campbell

We Embark for the Peninsula—Yorktown—Camping in the Mud—Peach Orchard—Artillery Practice—Battle of Williamsburg.

On the 17th of March the regiment embarked and steamed down the Potomac, past Mount Vernon, of hallowed memories, on its way to Fortress Monroe, whither the army was being transferred to enter upon the historic and ill-fated Peninsular campaign. Upon arrival it went into camp near the ancient, but then recently burned town of Hampton, crumbling brick walls and charred chimneys being the only remaining monuments to mark the site of the once pleasant village, the beginning, to us, of the scenes of the war's "rude desolations," while protruding from the placid waters of the bay were to be seen the masts of the "Cumberland," that but a few days before had gone down with flag flying before the onset of the ram "Merrimac," while over by the Ripraps peacefully floated low on the waters the little "Monitor" that David-like, had single-handed put to flight this Goliath of the rebellion, that had defied our navy; a veritable "tub on a plank."

On the morning of April 4 the grand advance was begun. Across the narrow neck of land that divided the waters of the Chesapeake and James, the magnificent hosts of the Army of the Potomac, stretching from shore to shore, moved forward to the fortified post of the enemy at Yorktown. Battlefields, like history, repeat themselves. It is said the plains of Esdraelon have been the theater of a greater number of conflicts at arms than any other known portion of the globe, so here at Yorktown, where the Sons of Virginia, Pennsylvania and others of the thirteen colonies humbled the British under Cornwallis in 1781, and whose lines of entrenchments were yet visible, were again to meet in 1862, the sons of these sires of revolutionary fame, in martial combat, not shoulder to shoulder, as then, but in opposing phalanx. The line of advance of the 57th was by the main road leading from Hampton to Yorktown by way of Little and Big Bethel, the latter place being the scene of General B. F. Butler's unfortunate night venture of 1861.

The afternoon of the second day's march brought the advance of the army in front of the enemy's formidable works around Yorktown and along the Warwick river. For the space of nearly a mile, immediately in front of the town, the country was open, scarcely a tree or a shrub impeding the view of the fortifications, whose embrasures bristled with heavy ordnance. With drums beating and colors flying we marched boldly along the way and filing off into the open fields deliberately proceeded to pitch our tents and make our camp in the very jaws, as it were, of these frowning batteries. Whether it was a fear of bringing on a general engagement, or amazement at our audacity that kept the Confederates quiet behind their earth-works we did not then know, but subsequent events proved the former to be the cause. Not until the day following did they manifest a disposition to disturb our repose, and then only by a solitary shot that plunged into one of our company's streets, burying itself deep in the soft earth. This shot was sufficient, however, to admonish us of the fact that they had a perfect range of our camp, and could, of they chose, make it exceedingly uncomfortable for us. As a result we very deliberately withdrew, without the loss of a tent or knapsack, back to the main line in the woods, though not wholly beyond the range of their guns.

Once in our established camp there began a month of as arduous duty as untried soldiers were ever called to perform. Digging trenches, constructing earthworks, and picket duty, kept us constantly engaged, and to add to our discomfort the weather was extremely unpleasant; frequent rains wetting us to the skin and rendering the earth about the consistency of a mortar bed. Of this time Surgeon Lyman writes: "Here for three weeks the men walked in mud, slept in mud and drank water from holes scooped out of the mud. The combined remonstrances of the medical officers of the brigade, 'that a month's continuance in that place would deprive the government of the services of one-half of its members,' were met by the silencing reply, 'It is a military necessity.' The result showed that our fears were well founded. The malaria of the marshes and swamps of Yorktown, with the excessive labor performed in the trenches and on picket duty, debilitated our men for months, sending dozens of them to their graves, and rendering hundreds unfit for service, and many for life."

Here we had our first experience with the wild garlic, which grew spontaneously in the uncultivated fields and after a day or two's pasturing rendered the flesh of the beeves unpalatable, the taste of the garlic remaining long in the mouth after the act of mastication. Here, too, the regiment had its baptismal of blood, in the known to us, though never historically christened, "Battle of the Peach Orchard."

On the afternoon of April 11 the 63d Pennsylvania Volunteers, while on picket duty in the woods to the left of the Yorktown road, was attacked by the enemy. The 57th was ordered to its assistance and advancing at double quick, formed in line of battle, moving over the open field in face of a hot fire and quickly putting to flight the columns of the enemy, driving them back to the protection of their heavy batteries. In this short but exciting engagement, the regiment lost by wounds two men, Samuel Merven, of Company E, and John Cochran, of Company F. Cochran subsequently died from the effects of his wound and Merven was discharged. In this engagement, insignificant as it was, compared with its after battles, the regiment exhibited great coolness and gave token of its ability and readiness for future duty and service.

An incident occurred about this date, while the regiment was on picket duty, that is worthy of passing notice. Lieutenant Wagner, of the topographic engineers, was engaged in making drawings of the Confederate works. He had placed a camp table in an exposed position and spread his drafting material upon it. The white paper made an excellent target for the enemy's gunners. One of their shots struck the table and fatally wounded the lieutenant. A few moments after he rode along the rear of our lines, his shattered and bleeding arm dangling at his side. This shot is referred to, after these many years, by General Longstreet in his recent work, as one of two of the most remarkable shots, for accuracy of aim, of the war. He says:

"An equally good one (shot) was made by a Confederate at Yorktown. An officer of the topographical engineers walked into the open in front of our lines, fixed his plane table and seated himself to make a map of the Confederate works. A non-commissioned officer, without orders, adjusted his gun, carefully aimed it, and fired. At the report of the gun all eyes were turned to see the occasion of it, and then to observe the object, when the shell was seen to explode as if in the hands of the officer. It had been dropped squarely upon the drawing table and Lieutenant Wagner was mortally wounded."—Gen. Longstreet, in "From Manassas to Appomattox."

This shot appears, by a note to the text written by Capt. A. B. Moore, of Richmond, Va., to have been fired by Corporal Holzbudon, of the 2d company, Richmond Howitzers, from a ten-pound parrott gun.

Another incident more immediately connected with the regiment, worthy of a place in its history as an exhibition of accurate firing, occurred here. On the left of our regimental picket line was stationed a section of a field battery whose duty was to shell the enemy's works and prevent their annoying our lines. For some time Colonel Campbell watched with manifest disgust the green cannoneers blazing away at random, and with evidently little effect. At length stepping to one of the guns the colonel said:

"Boys, let me sight this gun for you." Running his eye along the sights and giving the elevating screw a turn, he said:

"Now, let her go!"

In an instant the death-dealing missile was speeding on its way, entered the enclosure and exploded amid the startled gunners of the enemy.

"There, boys, that's the way to shoot. Don't waste your powder!" said the colonel, as he turned and walked away, an expression of satisfaction wreathing his florid face.

By the 3d of May all things were in readiness to open our batteries of big guns on the Confederate fortifications and all were in excited expectation of the bombardment and possible storming of the enemy's works on the following day, but the morning light of the 4th revealed the enemy's strong works abandoned and empty. In the night, Johnson, who had superseded Magruder in command, like the Arab had "folded his tent and silently stolen away." The 105th Pennsylvania were the first to enter the abandoned works. The news of the evacuation of the works and retreat of the Confederates spread rapidly from regiment to regiment, and our bloodless victory, but not without the loss of many a brave boy, was celebrated with wild shouts and cheers. The cavalry followed closely on the heels of the retreating enemy, but the infantry did not take up the line of march until later in the day; Fighting Joe Hooker's division following first, with Kearny close in his rear. As we marched through the Confederate works, stakes planted upright in the ground with red danger signals attached gave warning that near them were planted torpedoes, placed there for the injury of the unwary by the enemy.

A story was told at the time that the planting of these torpedoes was revealed to Lieut. R. P. Crawford, of Company E, of the 57th, then serving as aid on General Jameson's staff, by a Confederate deserter. That the 105th Pennsylvania, being about to enter the abandoned works, this Confederate stepped out from the shelter of a building, and, throwing up his hands as an indication that he desired to surrender, came forward and revealed to Lieutenant Crawford, who chanced to be present, the secret danger that threatened them if they attempted to enter the works without caution. Thus forewarned of their danger, a squad of prisoners, under compulsion, were made to search out, and locate these concealed missiles, thereby preventing possible loss of life and woundings.

During the afternoon of the 4th the regiment marched with the division about four miles on the main road to Williamsburg and bivouacked for the night. By dark rain began to fall and continued throughout the night and the day following. The early morning of the 5th found us on the march again. The rain had thoroughly soaked the light clay soil and the preceding ammunition trains and batteries had worked the soft clay roads into deep ruts and numerous mud holes. To take to the fields and roadsides did not better much the marching, the unsodded fields being little better than quagmires, in which the men floundered to the knees.

All the forenoon there was now and then cannonading to our front with occasional rattle of musketry, indicative of skirmishing, but by two or three o'clock there came the long swelling roar of infantry firing, giving evidence that our advance had overtaken the enemy and they were making a stubborn stand. The atmospheric conditions were such that from these sounds the battle appeared to be but a mile or two in our advance, and at every turn of the way we expected to see the blue line of smoke and snuff the odors of burning powder, while in fact the engagement was five or six miles distant. Reaching a point about two miles from the battlefield the regiment was ordered to unsling knapsacks, doff blankets and overcoats and march at quick step to the front. As we neared the field, panting from our exertion, we passed a brass band standing by the roadside. General Heintzelman, observing them as he passed, exclaimed in that nasal twang so familiar to all:

"Play, boys, play! Play Hail Columbia! Play Yankee Doodle! Play anything! Play like h—l!"

It is needless to add that the band promptly obeyed and the strains of the national quickstep put a new spring in our weary limbs, revived our flagging spirits and with a rousing cheer we pressed forward. Arriving on the field the regiment was deployed in line of battle in the woods to the right of the road, but darkness was settling over the field, the firing soon ceased and we were not engaged. The night following was extremely disagreeable. The rain continued to fall, and drenched to the skin we lay on our arms all night without fire, blankets or rations. By morning the lowering clouds were gone, and so also were the Johnnies, leaving their dead unburied and their wounded to our tender care. Many private houses of the ancient town, all of the churches and that venerable seat of learning, from whose halls came many of the nation's most eminent statesmen and patriots, William and Mary College, were turned into hospitals, where friend and foe were gathered from the field of conflict, housed, and cared for by our surgeons and nurses with undiscriminating attention.

An incident that well illustrates the reckless daring of General Kearny, and which ultimately lost him to our cause, as well as the influence of such acts upon others, occurred during this engagement. During the battle, General Kearny, accompanied by General Jameson, rode out to the front, and on an open piece of ground, in full view of the contending forces, the two sat there observing the progress of the battle, apparently oblivious of the fact that they were exposing themselves as targets to the enemy's sharpshooters. Past them the minie balls were zipping, while the air was redolent with the "ting" of musket balls and buck-shot. At length, satisfied with their observations, they coolly turned their horses about and rode to the rear. The day following, General Jameson was approached by one of his aides who had witnessed the act, who said to him:

"General, don't you think the risk you and General Kearny exposed yourselves to yesterday was unjustifiable?"

"I certainly do," the general candidly replied.

"Then why did you take the risk?" the aide queried.

"Captain," said the general, gravely, "If I had been conscious that I would have been hit the next minute I would not have turned my horse's head. Why, what would Kearny have thought of me!"

After the battle the regiment camped immediately west of town. Of course the commands that had borne the brunt of the battle were lionized, as were also those officers who had acted a conspicuous part. On this field General Hancock received his chief sobriquet, "The Superb," which clung to him throughout life. Regimental ranks, after a hard day's fighting, often were very much broken, the losses not always being catalogued as of the killed and wounded; roll calls exhibiting many names marked "missing," or "absent without leave." These absentees invariably reported fearful losses in their commands. While in camp at Williamsburg a strapping big fellow with turbaned head, blue jacket profusely decorated with gold lace, and baggy red trousers, wandered into our midst.

"Hello! What regiment?" one of the boys inquired.

"—— regiment."

"But what state?"

"New York, of course."

"In the fight?"

"Yep. All cut to pieces. I'm the only one left!"

Battle of Fair Oaks—Death of Major Culp—Increasing Sick List—Advancing Our Lines—The Seven Days' Battles—Glendale or Charles City Cross Roads—The Fifty-Seventh Under Captain Maxwell as Rear Guard—Malvern Hill—Retreat to Harrison's Landing.

On the 7th the army resumed the march "on to Richmond," the 57th diverging from the main line to Cumberland Landing on the Pamunkey, where for several days it guarded the army stores that had been shipped by steamer to that point. Afterwards we rejoined the brigade at Baltimore Store, and on the 24th crossed the famous Chickahominy at Bottom's bridge and camped on a pine covered bluff to the left of the railroad, a short distance from the river and near Savage station.

As soldiers we knew little of the danger that confronted us, and nothing of the councils being held by the enemy plotting our discomfiture. This knowledge was reserved for us until the 31st. On that day about one o'clock, just after the regiment had its midday ration, like a clap of thunder out of a clear sky the crash of musketry came to our ears from the front. Casey's division of Key's corps, which had pushed about three miles to our front, and had erected some slight fortifications near Fair Oaks station, had been suddenly and fiercely attacked by overpowering numbers. For what seemed to us hours, that probably did not exceed minutes, we stood listening to the crash and roar of the battle. Soon the long roll was beaten, the bugle blast sounded, the order to "fall in" was given, and we knew our hour had come. Forming in line with the other regiments of the brigade, we were soon on the march toward the front at a quick-step. Taking the line of the railroad, and the sound of the battle for our guide, we pressed on. Nearing the battlefield we began to meet the scattered and retreating men of Casey's division, many of them wounded and bleeding, but the majority suffering only from panic. Among this fleeing and panic-stricken mass, field and staff officers rode, seeking to stay their flight and reform their broken lines. General Kearny rode among them shouting, "This is not the road to Richmond, boys." Approaching nearer the field of battle the lines assumed a more defiant order, and it was evident that the greater mass of the troops were nobly standing, and lustily cheered us as we passed. A short distance beyond Fair Oaks station the brigade was deployed in line of battle in an open field to the right of the railroad. The thick woods to our front afforded an excellent cover for the enemy's sharpshooters, of which they speedily availed themselves, field and staff officers being their tempting targets. In a few moments orders were received to move to the left. There was a slight cut at the point of crossing the railway track and under the sharp fire from the enemy there was some confusion in making the crossing. While effecting this movement Major Culp was instantly killed and several of the line wounded. After crossing to the left of the railroad the brigade was again formed in line, face front, and stood waiting orders to advance. Immediately in our front was a "slashing," several rods in width. Beyond that was standing timber quite open. We were not long waiting orders and soon were moving cautiously forward, scrambling over and through the felled timber. Once beyond the "slashing," our lines that had become disarranged were again formed. From our position we could see an open field beyond, across which extended a line of Confederate infantry, their compact ranks presenting a fine mark and in easy range of our Austrian rifles, with which we were then armed. Colonel Campbell, who had dismounted, having left his horse beyond the "slashing," standing a few paces to the rear of the column, in low, but distinct tone gave the command, "Ready! Aim! Fire!"

Every gun in the line responded. What the execution was is not known, the smoke from our pieces completely excluding our view, but that every Johnnie had not bitten dust was soon evident from the lively manner in which they sent their missiles amongst us in very brief time. After the first volley the regiment loaded and fired "at will," the men seeking cover behind logs and trees as best they could from the enemy's returning compliments. How long this duel was maintained it is impossible to state, as the occasion was such that to take note of passing time was out of question. The troops holding the extreme right of our line at length gave way, and the enemy, seizing the opportunity, threw forward a strong flanking column that soon began a severe enfilading fire that compelled us to fall back obliquely to avoid a retreat through the slashing, and take a position in the woods beyond the open field in which we first formed. This closed the fighting for the day, and night soon settled over the scene, and while we had met with reverses, yet we were encouragingly satisfied, for the enemy had not succeeded in his purpose, by overwhelming numbers, to drive us into the Chickahominy before reinforcement could come to our aid from the north side. That night we slept on our arms, without tents or blankets, for these we had left in our camp to the rear. During the night Sumner's corps succeeded in crossing the river, swollen by recent rains, and by daybreak was on the field, and engaging the enemy, drove him back to the shelter of his works about Richmond. The regiment lost severely in this engagement. Colonel Campbell was dangerously wounded in the groin and while being carried to the rear was again shot in the arm. Major Culp, as before stated, was killed, and Captain Chase, of Company K, mortally wounded. The loss in the line was eleven killed and forty-nine wounded. The command of the regiment now devolved on Lieutenant Colonel Woods, and Captain Simonton of Company B, was promoted to the rank of major. The battle was immediately followed by heavy rain storms. Tents and camp equipage were back in the rear and were not forwarded for two or three days. In the meantime the men stood about, drenched to the skin, or sat upon logs drying their saturated clothing upon their backs in the hot sunshine that interspersed the showers. The earth was soaked with water, which for lack of springs or wells, was used for drinking and cooking purposes, it only being necessary to dig a shallow hole anywhere to gather the needed supply. The damp hot weather brought about rapid decomposition of the dead and unburied animals and the chance bodies of friend or foe who had fallen in "slashing" or thicket and thus remained undiscovered, produced a sickening stench. These causes soon produced much sickness and the swamp fevers carried many to the hospitals, some never to return. Rumors of the renewal of hostilities, possibly by night attack, kept the army constantly on the alert, and our accouterments were rarely taken off night or day; orders being issued to sleep in shoes ready to "fall out" and "into line" at a moment's notice. On one occasion a kicking mule was the innocent cause of a hasty mustering of our forces, to the great chagrin of the weary and sleepy soldiery.

General Hooker, ever anxious for fight and adventure, made an advance on his own motion, in which he was actively supported by General Kearny, pushing his lines close up to the enemy's defenses, so that from a lookout station established in the top of a large tree the church spires and steeples of the coveted Confederate capital could plainly be seen. But this movement was not in accord with General McClellan's plan of campaign. The position was hazardous in the extreme, inviting another onset by the enemy, and we were soon withdrawn to our original lines and the shelter of our breastworks. This was our nearest approach to Richmond until after Appomattox in the spring of 1865. Amid these scenes of constant picket duty, digging rifle-pits, and building fortifications the regiment passed the month of June. On the 26th the sound of heavy firing on the extreme right came to our ears all the afternoon. The enemy in our front was exceedingly vigilant and we drew the fire of their pickets on the slightest exposure. Late in the evening loud cheering was heard to our right, and the report was circulated, and credited, that that wing of our army had carried the Confederate defenses to the north of the city, and we lustily joined our comrades, as we supposed, in their shout of victory. But, alas! for the truthfulness of camp rumors! It was all a mistake; our lines had only successfully repulsed the enemy's repeated assaults at Mechanicsville! That was all. The next day, the 27th, the battle was renewed at Gaines Mill, a little nearer to our position. The day following, the 28th, our immediate line withdrew from its advanced position and stood ready to repel any attack that might be made on the battle-worn troops of Porter and Warren as they slowly filed across the Chickahominy to the south side. Late in the afternoon General Kearny directed the distribution to each man of one hundred and fifty rounds of ammunition (more than twice our usual allowance), and also that each officer in his command should place a red patch in conspicuous view upon his hat or cap. What to do with the superfluous ammunition was a question, and called forth many uncomplimentary remarks, some even suggesting that it was intended to relieve the mules of the ammunition trains by making pack-horses of the soldiery. But we had not long to wait to know the real cause and the wisdom of it, and glad were we to have the extra cartridges for convenient use! The red patch order also proved an important event in army history, in that it was the beginning of the corps badge so popular and useful in the after years of the war. The afternoon of the next day, the 29th, after a day of anxious waiting and expectancy, the regiment took up the line of march, with the crash of the battle of Savage station ringing in their ears, southward across the White Oak swamp. Late in the evening we filed off upon a by-road leading at right angles to the road on which we were moving. Soon we reached a wide swamp, across which had recently been constructed a causeway, or bridge of logs laid in the mud and water side by side, and which was perhaps twenty rods in length. Without hesitation the regiment marched out upon this bridge. When the head of the column had about reached the opposite end it was fired upon by the enemy's pickets. Here was a dilemma calculated to try the nerve of the bravest. What the enemy's force was none knew, but anyone could realize the terrible slaughter that might be wrought had a section of artillery been turned upon that narrow roadway with a swamp of unknown depth on either side. General Kearny, with his accustomed daring, was at the head of the column. Turning about, he rode back along the line, his face grave, but calm. "Keep quiet, boys, keep quiet. Don't be alarmed. About face and move to the rear!" he said as he passed. Every man in the regiment seemed to realize the gravity of the situation, and that upon his personal coolness depended the safety of the retreat, and without noise or confusion the regiment "about faced" and soon was back on the road from which we had strayed. That night we bivouacked without tents or fires, wrapping ourselves in our blankets, and, lying down, star gazed until our eyes closed in slumber.

The 30th dawned hot and sultry, and as the men trudged along under the fierce glare of the sun, and their burden of knapsack, haversack, and extra ammunition, many succumbed and fell out of the ranks. Arriving at the intersection of the Charles City road with that upon which we were marching about mid-day, the regiment filed to the right into an open field, stacked arms and broke ranks. Some of our number sought rest in convenient shade, others busied themselves building fires and cooking coffee. In all our surroundings there was not a sign of the enemy's presence, or that from the cover of the woods beyond the field his scouts were watching our every movement. Cannonading from the direction whence we had come gave evidence that he was yet beyond the dismal swamps through which we had passed the day before, and the rank and file at least was not aware that a strong force was at that moment marching upon our line from the west with a purpose to intercept us on our way toward the James. To the left of us a section of Randolph's battery stood unlimbered, a circumstance rare to be seen while on the march, and to the old soldiers suggestive of possible battle, but the gunners were lolling upon their pieces or sitting about the ground chatting, apparently indifferent, and if they were so, why need others feel concern? Thus time passed until 2 o'clock p. m., when suddenly one of those unlimbered pieces, with a crash that brought every man to his feet, sent a screaming shell far out over the woods beyond. This defiant shot seemed at once to be accepted by the enemy as a challenge to action, for immediately there followed a spattering discharge of musketry along our front, the bugle notes sounded and the command to "fall in" rang out along the lines.

In advancing to take our position in the line of battle each man seized a rail of a convenient fence that stood in the way, and when halted, out of these constructed an improvised shelter, behind which we crouched to meet and repel the enemy's desperate onslaughts. From that hour until darkness covered the scene, the battle raged furiously and almost incessantly. Charge after charge was made upon our lines, often coming so near that faces were clearly discernible through the smoke of battle, so determined was the enemy to break our lines and reach the road in our rear, over which our wagon trains and unengaged forces were pressing toward the James river.

Perhaps in no battle of the war was there so long and continuous fighting by the same troops as in this engagement. It was all important that the army should be safely guarded past this most vulnerable point, and posted on the river bluffs and under the protection of our gunboats. The enemy, as well, seemed to realize the need of breaking our lines or lose the fruits of their victory purchased at such fearful cost, and therefore pressed our line hard and continuously, so that if disposed to do so, there was little time given to relieve us by the substitution of other troops.

In this engagement Major Simonton was wounded in the shoulder about 6 o'clock in the evening. Lieutenant Colonel Woods was absent on sick leave, and the command of the regiment devolved upon Captain Ralph Maxwell, of Company F. Before midnight the troops were withdrawn from the line of battle and were on the march to Malvern Hill, the place of rendezvous of the army, near the James river. As we moved quietly along in the darkness General Kearny rode up and asked Captain Maxwell what regiment we were. When informed, he complimented us very highly for the part we had taken in the recent battle, then ordered him to return us to our old position and hold it until daylight, when he would have us relieved. We "about faced" and were soon back in our old place as nearly as could be determined in the darkness. The supposition was that the whole brigade was with us and we did not discover differently until an hour or more later. Of this occurrence Captain Maxwell says: "I thought along toward midnight I would go and have a talk with whoever commanded the 105th. I went to the right of the 57th, but could find no one; all was vacancy. I immediately retraced my steps and, passing to the left, found the 63d gone also. Nobody there but one poor, little, lone regiment! It then came to me that we were placed there to be sacrificed for the safety of the rest of the army. I knew the penalty for violating General Kearny's orders, but at the same time I could not think of sacrificing these men to certain capture and imprisonment. I did not like to break orders and I could not do the other. Soon after we heard the trundle of artillery, and the tread of the marching men to our front, and then lights gleaming to our front. Evidently this was the enemy. I made up my mind I would try and save the regiment, orders or no orders, and let them court-martial me and be d—d. I ordered the regiment to form silently in two ranks, then gave the order to march and file right. They did so and all filed past me and got on the road. I then ran along the line to the head of the regiment and gave the order to double quick, and we went down that road on the run, and none too soon. Five minutes more and we would have been prisoners! We caught up to the main body of the army and took our usual position in the brigade. I was afraid to ask any questions and never heard anything about our disobedience of orders. But one thing is certain, I am glad I did what I did that night!"

In this engagement our regiment lost seven killed and fifty-six wounded, a number of whom subsequently died.

The next morning found the regiment in line on Malvern Hill. This position was almost impregnable. On the south side flowed the James river on which floated the Union fleet of gunboats. On the north side was an impenetrable swamp. To attack, the Confederates had to charge from the west and in our front over long stretches of open ground in the face of our batteries posted along the hill side, their right flank enfiladed by the fire from our gunboats. General Porter, speaking of the strength of this position, says that when by inspections he realized its natural advantages, and had seen his division properly posted, he returned to the Malvern House, where he had established his headquarters, and, lying down on a cot, dropped at once into so sound a sleep, that although the battle following surged up to the front yard of the house, he was not awakened, although at any other time during the campaign the snap of a cap would rouse him instantly, so great was his sense of the security of his position. Notwithstanding these natural advantages, the elated, but weary forces of Jackson, Longstreet, and Hill, reinforced by the fresh troops of Magruder and Hugar, charged and recharged our lines with desperate persistence deserving of a better cause, but each time were repulsed with fearful slaughter. The losses of the 57th in this engagement were two killed and eight wounded, Lieutenant Charles O. Etz and the orderly sergeant of Company D being the two fatal casualties. The death of Lieutenant Etz and his companion occurred under peculiarly sad circumstances. Wearied with the battle of the preceding afternoon and the night vigil following, these two comrades had lain down together, the sergeant's head resting on the lieutenant's breast, and were snatching a moment's sleep. A shot from one of the enemy's batteries struck the two sleepers, killing them instantly. Thus, all unconscious of their danger, they were swept by one swift stroke into that sleep that knows no waking.

The battle over and the enemy severely chastised, the grand Army of the Potomac, with thinned and broken ranks, a mere shadow of its former greatness, continued the retreat, Harrison's Landing, a place of historic importance in that the line of its occupants has given to our country two chief executives, lying a few miles below Malvern Hill on the James, being the place selected for final rendezvous. During the night following the battle the 57th was again on outpost duty, but early the following morning was quietly withdrawn and in a drenching rain that continued throughout the day, again took up its wearisome march, arriving in the vicinity of the landing toward evening, weary, wet and worn!

The Harrison mansion, a substantial structure of brick, reared in colonial days, stood on an eminence overlooking the broad sweep of the James river. Between the mansion and the river was a stretch of grass-covered field gently sloping to the water's edge. Adjoining this to the west, or northwest, was a large wheat field. A greater part of the standing grain had been cut and was in shock. These golden sheaves were quickly appropriated by our troops and spread upon the water-sodden ground, whereon to rest their weary bodies. A few brief hours sufficed to obliterate every trace of this harvest scene, and where the husbandman had so recently been reaping in peace the fruits of his field, batteries were now thickly packed and soldiers' tents, not white, but wet and earth soiled, stood in long ranks.

Camp Life at Harrison's Landing—Major Birney Assigned to the Command of the Regiment—Transferred to General Birney's Brigade—Evacuation of Harrison's Landing and the Peninsula—The Army of the Potomac is Sent to Reenforce General Pope.

The regiment, upon its arrival at Harrison's Landing, presented a most pitiable spectacle. But three months before it numbered almost nine hundred; now but little over half a hundred responded for duty at first roll-call, and there was not a field officer present. Says Surgeon Lyman: "All were exhausted and disheartened, scarcely a well man in the regiment, with two hundred and thirty, for the first few days, on the sick list." For a time Captain Ralph Maxwell was in command of the regiment, but was succeeded later by Captain Strohecker. Funerals were of such frequent occurrence that the solemn notes of the dead march were almost continually to be heard, until, for the benefit of the living, burials with military honors were suppressed by general order. To the great annoyance of brigade commanders they could muster no more men for brigade drill than would compose an ordinary battalion; the regiments presenting no better appearance as to numbers than a company, and a company than a corporal's guard. As a consequence there were frequent charges of "shirking duty" preferred, and the officers of the line watched and counted with greatest care their rolls for available men. An amusing anecdote of this watchful regard of the superior officers is told by Colonel Strohecker. He says:

"For a few days our regiment was attached to the 63d, and under the command of Colonel Alexander Hayes. On one occasion he had the two regiments 'fall in,' and passing along the line counted the men in each company with great care, comparing their number with the adjutant's report which he held in his hand. When he counted my company I lacked three men to fill the report, and then the colonel commenced cursing me for reporting more men than I turned out. I replied that I did not report more men than I had in line. At this he exhibited to me the adjutant's report and said he would see me later. True enough, there were three more men reported for duty on the adjutant's report than I had turned out. The figures were against me. He dismissed me and I went to my quarters crestfallen. I took up my morning report book, and discovered there was a mistake somewhere. My morning report and the number of men I had in line tallied exactly. I immediately called upon the colonel and armed with my morning report proved that I was right. He called his adjutant and asked him to explain. That officer replied that in consolidating the company reports he could not make them agree, so he just put three more men to my account! 'What!' exclaimed the colonel. 'You falsify the morning report of a captain and his orderly? I'll let you know' and then the very air seemed blue! To me he only said, 'Captain won't you have a drink?'"

General Kearny was no admirer of a rifle-pit campaign. "An open field and a fair fight," was more to the pleasing of the military taste of this intrepid commander; he was, therefore, loth to have his troops exhausted with the labor of their construction, and as occasion offered was not slow to so express himself. One quiet Sabbath morning, while in camp at this place, a detail from the 57th was on its way, armed with pick and spade, to this duty. As they trudged along their way Kearny met them, and, returning the salute of the lieutenant commanding the squad, inquired:

"Lieutenant, where are these men going?"

"To work on the breastworks, general," replied the officer.

"About face your men, and return to your quarters," sharply replied the general. "Six days in the week are enough to work on fortifications. These men need their Sunday rest!"

It is needless to say the order was promptly obeyed and regard for their commander rose several degrees in the estimation of these weary veterans.

The camp of the regiment was near a fine stream of water on which was erected a dam that afforded the men most excellent bathing opportunities, which doubtless contributed much to their general health besides personal cleanliness. Ovens were also built and for a time they enjoyed the luxury of "soft bread." There was, however, a dearth of vegetables, and aside from an occasional ration of onions, and that conglomeration of pumpkin, squash, etc., compounded under the euphonious name of "dessicated vegetables," but which the boys derisively dubbed "desecrated vegetables," green truck was unknown in their daily bill of fare, in consequence of which diarrhoea and kindred complaints were prevalent, and many disqualified for active duty.

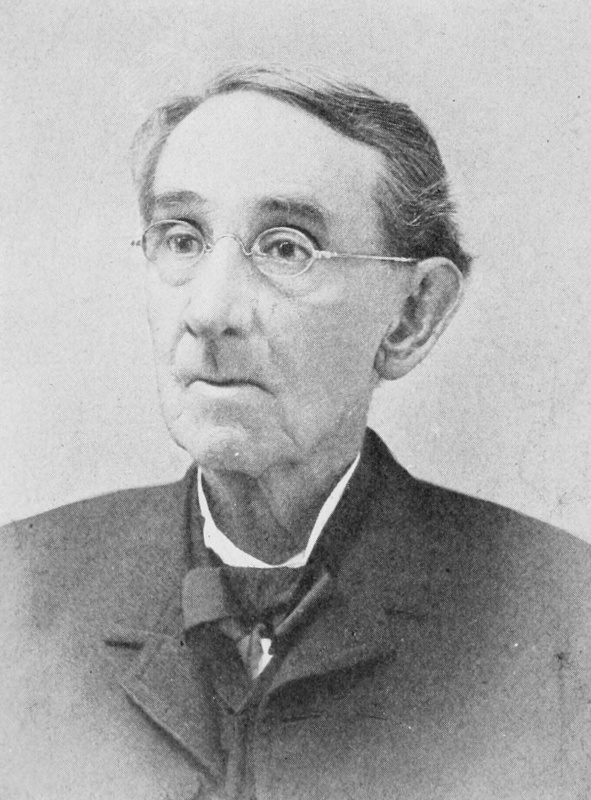

William Birney

During the encampment at Harrison's Landing Major William Birney, of the 4th New Jersey regiment, a brother of General David B. Birney, was assigned to the command of the 57th regiment. Major Birney was an officer of rare ability, a strict disciplinarian, an indefatigable drill-master, and withal a gentleman, winning and courteous to the humblest when off duty, and abhorring the petty tyrannies in which some officers of brief authority seemed to delight. He also enjoyed to the highest degree the confidence of his superiors, and very soon won the respect and esteem, as well, of the rank and file. A story told about the camp fires, whether true or false, well illustrates the characteristics of the man and deserves recording. At the breaking out of the war Major Birney was commissioned an officer in one of the New Jersey regiments composing the New Jersey brigade, commanded by General Kearny, but possessed of little knowledge of his duties as such, or ability to drill his men. On one occasion while attempting to put his regiment through its evolutions General Kearny chanced to pass, and halting, watched the major in his attempts with evident disgust. The general was never noted for his patience, especially with inefficiency of an officer in his line of duty, and riding up to the major, reprimanded him sharply, bidding him to go to his quarters and never attempt to drill his men again until he had mastered the tactics. It is said, the major, stung with reproof, went to his quarters, not to sulk over this and possibly resign his commission, but to study, and when he next appeared on drill he was the best informed and most efficient drill master in the brigade, receiving the compliments of the general, who ever after held him in highest esteem. Of the major's persistency, if not his efficiency, as a drill master, every member of the 57th regiment would willingly certify.

Major Birney's discipline was not confined to camp life, and the drill ground. It extended as well to the march. Every morning on the march the regular detail for guard duty was made, and this detail, under command of the officer of the day, marched at the rear of the column, and proved an efficient preventive to "straggling," a habit exceedingly demoralizing to an army on the march. If any fell sick or gave out by the way they were taken charge of, and if possible, were placed in an ambulance, or in the absence of such, in one of the regimental or brigade wagons. If canteens needed replenishing a detail was made from each company to perform that duty. If foraging was to be engaged in it was done in the same methodical manner, and this was not infrequent, for the major was a strong believer in the doctrine of the rights of the army to live off the products of the enemy's country, but it had to be done "decently and in order."

When on the march, if an obstruction was encountered, the head of the column was always halted until all had passed the obstruction and the ranks closed up. By this means the men in the rear were saved the necessity of moving at a "double quick" to overtake those in advance, a duty very exhausting, and as a consequence the command was always kept in compact order and could, with less fatigue, march twenty miles a day than ten by the old "go as you please" methods so common while on the march.

During our army's encampment at Harrison's Landing the Confederates were quiet and only deigned to make their presence known on one occasion and that was in the way of a night surprise, sending by way of a reminder that they were yet alive and alert, a number of shells across from the heights on the south side of the river. This piece of pleasantry was replied to promptly by our batteries, and the next day arrangements were made to prevent a repetition by sending a division of infantry under General Butterfield over to that side and taking possession of those hills for ourselves.

On August 12th the 57th was transferred from Jameson's old brigade (the 1st) to General D. B. Birney's (2d) brigade. General Jameson was injured by the falling of his horse at Fair Oaks and died from his injuries the following November. He was one of the finest looking officers in the army. General J. C. Robinson succeeded him in command, and led the brigade in the seven days' battles. General Birney was one of the original brigade commanders of Kearny's division. His brigade now comprised the following regiments, viz: the 57th and 99th Pennsylvania; 3d and 4th Maine; 38th, 40th and 101st New York. There were seven regiments, but numerically, they scarcely exceeded the strength of two full regiments.

On August 15th, the army broke camp and commenced the retrograde movement back through Williamsburg and Yorktown, our campaign ground of the earlier spring, its ultimate destination being to join Pope in his disastrous campaign with headquarters "in the saddle."

The breaking camp of a great army is always a stirring scene. The mounted aids and orderlies riding in hot haste; the mustering legions and forming squadrons with flying colors; the bonfires of camp debris; the popping of discarded cartridges with occasional deeper intonation of exploding bomb, altogether make a scene not soon to be forgotten.

The time of year was the "roasting ear" season of the Virginia cornfields, and great fears were entertained by the army medical staff as to the probable disastrous results to the men of a too free indulgence by them in that luxury. As a consequence they were strictly admonished to abstain from the toothsome viand, but all to no purpose. We had roasting ears boiled, roasting ears roasted, and roasting ears broiled in the husk. We had green corn on the cob and off the cob. Green corn for breakfast, green corn for dinner, and green corn for supper, with an occasional lunch of green corn between times. Yet, wonderful to relate, instead of any injury resulting, on the contrary the effect was decidedly beneficial, in that by the time we arrived at Yorktown there was scarcely a man to respond to sick call.

The evening of the first day's march the regiment camped near a large brick plantation house. The owner and family were absent, but the negro servants were very much "at home" with the "Yanks" and until late in the night were busily employed baking "hoe cake" for all who applied.

The following day the 57th with the 4th Maine were detached and served as "flankers" on the left of the army, marching by a road that intersected the road by which the regiment had advanced from Williamsburg toward Richmond at a point near Barhamsville, thence by the last named road to Williamsburg and Yorktown. At Williamsburg there still remained many evidences of the struggle of the preceding May, particularly the marks of shot and shell upon the standing timber, many of these marks being high up on the tree trunks and exhibiting a very unsteady aim.

At Yorktown the regiment embarked for Alexandria and from thence were speedily transferred by rail on the Orange and Alexandria road to a point near Warrenton Junction.

At Alexandria many of the men took the opportunity to imbibe a liberal quantity of liquid refreshments, the first chance they had to do so since the issuing of whiskey rations in the swamps in front of Richmond. To the credit of the 57th, but very few indulged beyond their capacity to carry their load steadily, but such could not be said of some of the other regiments in the division, notably one of New York, in which there were not a sufficient number of "sobers" to care for the "drunks." The cars on which we were shipped to the front were the ordinary "flats." By the time their "drunks" were safely deposited on these cars by the "sobers" fully one-half had rolled off into the side ditches, and so the process of reloading had to be repeated time and again with many intervening, and sometimes amusing, sparring matches to add to the confusion and delay. While these bacchanalian exhibitions were going on General Kearny and staff rode along the side of the railway track, doing what they could in the way of encouragement to the overworked "sobers" in their apparently endless task. As the general passed the 57th some member called out to a comrade near to the scene of drunken strife in progress on the adjoining cars, inquiring if any of the 57th were engaged in the fracas then going on. The general promptly turned in his saddle and shouted back, "No, thank God, there's none of the 57th!"

It was not the regiment's privilege to ride all the way from Alexandria to its destination at the front. Disembarking near Catlett Station it advanced by easy marches.

Somewhere on the Virginia Peninsula Captain Maxwell, of Company F, had secured the services of an old negro as his cook. At Malvern Hill this old fellow had not put sufficient space between himself and the enemy for safety, and found himself in rather close proximity for comfort to the shells of their batteries. While at Harrison's Landing it was the delight of the boys to get this old man to describe the battle and give his experience under fire. His inimitable imitation of the screaming shot and shell accompanied with grotesque pantomime was amusing in the extreme. We little thought, however, the deep impression these scenes and experiences had made upon his mind until again we came in sound of the enemy's guns. As the regiment advanced toward Bealeton the cannonading in our front became at times quite heavy. The old cook was trudging along by the side of the marching column, carrying a camp kettle, when suddenly the batteries opened fire. He stopped, looked and listened, with fear depicted in every lineament of his dusky face. "Dis chil' done gone fur 'nuf dis way!" he exclaimed. Then turning about took toward the rear as fast as his legs could carry him. It was the last seen of the captain's cook.

Second Bull Run Campaign—Battle of Chantilly—Death of General Kearny—His Body Escorted to Washington by a Detachment of the Fifty-Seventh—Retreat to Alexandria—Conrad's Ferry—Colonel Campbell Rejoins the Regiment.

Our stay in the neighborhood of Bealeton and Warrenton Junction was brief. Lee was moving northward, the main body of his army being west of the Bull Run mountains, while Jackson with Stewart's cavalry was on the east. The 3d corps in which the 57th served fell back to Centerville by way of Greenwich and Manassas Junction. As we passed the latter the buildings and many cars were smouldering ruins, showing that Jackson's outflankers had recently been there, and that the main body of his troops could not be far distant. The night of the 28th we bivouacked at Centerville and the next morning marched out the Warrenton turnpike. On our way we met quite a number of paroled prisoners who had just been sent through the lines by Jackson. They were quite jubilant, reporting that desperate fighter completely hemmed in at the base of the mountains and likely to fall an easy prey to our army. With this hopeful intelligence we pressed on with stimulated zeal toward the front. Arriving on the battlefield Kearny's division was deployed on the extreme right of the line, which position it held during the two succeeding days of the battle, most of the division at one time or other being hotly engaged. The 57th, however, escaped, though frequently under fire. Along the left and center the battle raged fiercely. The issue hung upon the ability of Pope to crush his antagonist, the redoubtable "Stonewall," before assistance could come to him from his chief beyond the mountains. But alas for our fondest expectations! Longstreet pressed his way through the insecurely guarded mountain pass, Thoroughfare Gap, and late in the afternoon of the 30th, when victory seemed about to perch on our banners, threw himself with irresistible force against our left. The onset was so fierce and unexpected that it did not lie in human power to resist, and in a few brief moments, all hope vanished, rout followed, and an almost fac simile of the disaster of the preceding summer was the consequence, except that our legions were veterans now, the army retained its morale and (especially the right wing) fell back in good order upon Centerville, the enemy, either from being sorely crippled, or satisfied with his success, giving little annoyance. The army in this encounter could not be said to have been defeated. Fully one-third of its efficient force had not been engaged. A general impression prevailed in the ranks that we either had been outgeneraled or that some stupendous blunder had been made.

Rumors of disobedience of orders by officers high in rank filled the air, and mortification and chagrin the breasts of all. We were not whipped; that would have been satisfying. The story was that in the game of war our adversary, in playing his winning card, had been aided by the petty strifes and jealousies among our own leaders. Happily history has done much to remove this feeling and as well the clouds that overcast the fair name and fame of at least one of our corps commanders, whose bravery and ability none doubted. But then it was different, and provoked by defeat, slight evidence was sufficient to call down maledictions loud and bitter.

During August 31st and September 1st the regiment camped near Centerville, but in the afternoon of the 1st received marching orders and filed out on the road leading to Fairfax Court House. Marching leisurely along, all unconscious of the near presence of an enemy, we were suddenly startled by the sound of skirmish firing to our left. A moment later General Kearny and staff rode past at a gallop. The desultory firing of the skirmishers increased rapidly to volleys and soon we were advancing to the front at a double quick. Wheeling to the left of the road on which we were marching we were deployed in line of battle; part of the division immediately advanced and soon was hotly engaged. In the midst of the roar of battle a fierce electric storm burst upon the contending forces, and the flashes of lightning and peals of thunder mingled with the crash of musketry and booming of cannon, while rain descended in torrents. While the regiments of the division were being advanced General Kearny sat on his horse but a few paces from the 57th. Some of his staff suggested that the regiment be assigned to the advance column. "No," replied the general, "place the 57th in reserve. If these men have to retreat I want them to fall back upon men that won't run!" These were the last words he ever uttered in our presence. Within a brief hour he lay cold in death within the enemy's lines, the victim of that spirit within him so often manifested on the field of battle and at the post of danger, never to send another where he himself would not willingly go.

To the 57th was accorded the honor of receiving from the Confederates under a flag of truce the following morning the remains of their fallen leader, the five right companies, A, B, C, D and E, with the colors subsequently acting as special escort of the body to Washington, D. C.

The day following the short, but sanguinary engagement at Chantilly, the remaining companies of the regiment, not detached for the above mentioned sad duty, marched to Alexandria and encamped near the regiment's old quarters of the preceding winter. While in camp an incident occurred that came near breaking up the regimental organization. During the Peninsula and Bull Run campaigns the regiment had become reduced in numbers to scarcely one-fourth of its original strength, and as a consequence an order was issued directing the consolidation of the regiment with the 99th Pennsylvania Volunteers, which was a comparatively new organization, had seen but little field service and had but recently been assigned to the brigade. The news of this order caused the most intense feeling, the men declaring that "having received from Governor Curtin their colors when they were returned to the state capital they would return with them." Major Birney was still absent, having accompanied the remains of General Kearny to Newark, New Jersey. Chaplain McAdam immediately visited Washington, interviewed the Secretary of War, put himself in communication with Governor Curtin and soon brought to us the good news that the order had been countermanded. Chaplain McAdam's success in this important undertaking gave him great popularity in the regiment, if, indeed, his popularity could be increased, for from the first organization of the regiment the chaplain had a warm place in the esteem and confidence of the men, irrespective of rank or condition.

The regiment had not been visited by its paymaster since some time before the Seven Days' battle. As a consequence few if any were the possessors of a "greenback." This alone was aggravating, but when our proximity to Alexandria brought us daily visits by numerous hucksters of fruit and gingerbread, not to mention real and toothsome pie, the aggravation was intensified to a degree unbearable. This reached the climax when on a certain occasion a wagon load of watermelons was deliberately driven into camp and displayed on the parade ground. The vender of this luxury, however, demanded a price that no sixteen dollar soldier of "Uncle Sam" could think of paying. The temptation to enjoy the luscious fruit was too great. One of the boys, disregarding the admonitions of a home-cultured conscience which he still cherished, picked up a melon and walked off with it to his quarters. The huckster followed to collect pay or to recover his property, but alas! his efforts to reclaim the lost melon left the remainder unguarded, and he returned to his wagon only to find the last one gone and his wagon empty. Gone, doubtless, in the way of all good melons in an army camp.