The Project Gutenberg EBook of Not Snow Nor Rain, by Miriam Allen deFord This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you are located before using this ebook. Title: Not Snow Nor Rain Author: Miriam Allen deFord Release Date: November 18, 2019 [EBook #60725] Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NOT SNOW NOR RAIN *** Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

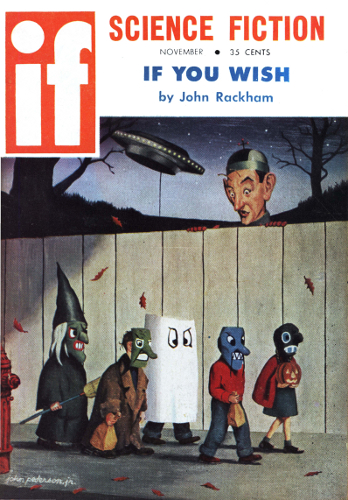

Sam should have let the 22 nixies

go to the dead letter office ... or

gone there himself for sanctuary!

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Worlds of If Science Fiction, November 1959.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

On his first day as a mail carrier, Sam Wilson noted that inscription, cribbed from Herodotus, on the General Post Office, and took it to heart: "Not snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night stays these couriers from the swift completion of their appointed rounds."

It couldn't be literally true, of course. Given a real blizzard, it would be impossible to make his way through the pathless drifts; and if there had been a major flood, he could hardly have swum to deliver letters to the marooned. Moreover, if he couldn't find the addressee, there was nothing to do but mark the envelope "Not known at this address," and take it back to be returned to the addresser or consigned to the Dead Letter Office. But through the years, Sam Wilson had been as consciously faithful and efficient as any Persian messenger.

Now the long years had galloped by, and this was the very last time he would walk his route before his retirement.

It would be good to put his feet up somewhere and ease them back into comfort; they had been Sam's loyal servants and they were more worn out than he was. But the thought of retirement bothered him. Mollie was going to get sick of having him around the house all day, and he was damned if he was going to sit on a park bench like other discarded old men and suck a pipe and stare at nothing, waiting for the hours to pass in a vacuum. He had his big interest, of course—his status as a devoted science fiction fan; he would have time now to read and reread, to watch hopefully from the roof of his apartment house for signs of a flying saucer. But that wasn't enough; what he needed was a project to keep him alert and occupied.

On his last delivery he found it.

The Ochterlonie Building, way down on lower Second Avenue, was a rundown, shabby old firetrap, once as solid as the Scotsman who had built it and named it for himself, but now, with its single open-cage elevator and its sagging floors, attracting only quack doctors and dubious private eyes and similar fauna on the edge of free enterprise. Sam had been delivering to it now for 35 years, watching its slow deterioration.

This time there was a whole batch of self-addressed letters for a tenant whose name was new to him, but that was hardly surprising—nowadays, in the Ochterlonie Building, tenants came and went.

They were small envelopes, addressed in blue, in printing simulating handwriting, to Orville K. Hesterson, Sec.-Treas., Time-Between-Time, 746 Ochterlonie Building, New York 3, N. Y. Feeling them with experienced fingers, Sam Wilson judged they were orders for something, doubtless enclosing money.

In most of the buildings on his last route, Sam knew, at least by sight, the employees who took in the mail, and they knew him. A lot of them knew this was his last trip; there were farewells and good wishes, and even a few small donations (since he wouldn't be there next Christmas) which he gratefully tucked in an inside pocket of the uniform he would never wear again. There were also two or three invitations to a drink, which, being still on duty, he had regretfully to decline.

But in the Ochterlonie Building, with its fly-by-night clientele, he was just the postman, and nobody greeted him except Howie Mallory, the decrepit elevator operator. Sam considered him soberly. It was going to be pretty tough financially from now on; could he, perhaps, find a job like Howie's? No. Not unless things got a lot tougher; standing all day would be just as bad as walking.

He went from office to office, getting rid of his load—mostly bills, duns and complaints, he imagined, in this hole. There was nothing for the seventh floor except this bunch for Time-Between-Time.

The seventh floor? He must be nuts. The Ochterlonie Building was six floors high.

Puzzled, he rang for Howie.

"What'd they do, build a penthouse office on top of this old dump?" he inquired.

The elevator operator laughed as at a feeble jest. "Sure," he said airily. "General Motors is using it as a hideaway."

"No, Howie—no fooling. Look here."

Mallory stared and shook his head. "There ain't no 746. Somebody got the number wrong. Or they got the building wrong. There's nobody here by that name."

"They couldn't—printed envelopes like these."

"O. K., wise guy," said Howie. "Look for yourself."

He led the way to the short flight of iron stairs and the trap door. While Mallory stood jeering at him, Sam determinedly climbed through. There was nothing in sight but the plain flat roof. He climbed down again.

"Last letters on my last delivery and I can't deliver them," Sam Wilson said disgustedly.

"Somebody's playing a joke, maybe."

"Crazy joke. Well, so long, Howie. Some young squirt will be taking his life in his hands in this broken-down cage of yours tomorrow."

Sam Wilson, whom nothing could deter from the swift completion of his appointed rounds, had to trudge back to the post office with 22 undelivered letters.

Years ago the United States Post Office gave up searching directories and reference books, or deciphering illiterate or screwy addresses, so as to make every possible delivery. That went out with three daily and two Saturday deliveries, two-cent drop postage, and all the other amenities that a submissive public let itself lose without a protest. But there was still a city directory in the office. Sam Wilson searched it stubbornly. Time-Between-Time was not listed. Neither was Orville K. Hesterson.

There was nothing to do but consider the letters nixies and turn them over to the proper department. If there was another bunch of them tomorrow, he would never know.

Retirement, after the first carefree week, was just as bad as Sam Wilson had suspected it was going to be. Not bad enough to think yet about elevator operating or night watching, but bad enough to make him restless and edgy, and to make him snap Mollie's head off until they had their first bad quarrel for years. He'd never had time enough before to keep up with all the science fiction magazines and books. Now, with nothing but time, there weren't enough of them to fill the long days. What he needed was something—something that didn't involve walking—to make those endless hours speed up. He began thinking again about those 22 nixies.

He sat gloomily on a bench in Tompkins Square in the spring sunshine: just what he had sworn not to do, but if he stayed home another hour, Mollie would heave the vacuum cleaner at him. In the public library he had searched directories and phone books, for all the boroughs and for suburban New Jersey, Connecticut and Pennsylvania; Orville K. Hesterson appeared in none of them.

He didn't know why it was any of his business, except that Time-Between-Time had put a blot on the very end of his 35-year record and he wanted revenge. Also, it was something to do and be interested in. In a way, science fiction and detection had a lot in common, and Sam Wilson prided himself on his ability to guess ahead what was going to happen in a story. So why couldn't he figure out this puzzle, right here in Manhattan, Terra? But he was stymied.

Or was he?

Sam took his gloomy thoughts to Mulligan's. Every large city is a collection of villages. The people who live long enough in a neighborhood acquire their own groceries, their own drugstores, their own bars. The Wilsons had lived six years in their flat, and Mulligan's, catercornered across the street, was Sam's personal bar.

He was cautious as to what he said there. He'd heard enough backtalk already when he had been indiscreet enough once, after four beers, to express his views on UFOs. He had no desire to gain a reputation as a crackpot. But it was safe enough to remark conversationally, "How do you find out where a guy is when he says he's someplace and you write him there and the letter comes back?"

"You ought to know, Sam," said Ed, the day barkeep. "You were a postman long enough."

"If I knew, I wouldn't ask."

"Ask Information on the phone."

"He hasn't got a phone." That was the weirdest part of it—a business office without a phone.

In every bar, at every moment, there is somebody who knows all the answers. This somebody, a nondescript fellow nursing a Collins down the bar, spoke up: "It could be unlisted."

Sam's acquaintance didn't include people with unlisted phones; he hadn't thought of that.

"Then how do you find out his number?"

"You don't, unless he tells you. That's why he has it unlisted."

The police could get it, Sam thought. But they wouldn't, without a reason.

"Hey, maybe this guy's office is in one of them flying saucers and he forgot to come down and get his mail," Ed suggested brightly.

Sam scowled and walked out.

Nevertheless....

Nothing to do with UFOs, of course. That was ridiculous.

But suppose there was a warp in the space-time continuum? Suppose there had once been another Ochterlonie Building, or some day in the future there was going to be another one, somewhere in New York? There wasn't another now, in any of the boroughs, or any other building with a name remotely like it; his research had already established that.

Sam went back to the Public Library. The building he knew had been erected in 1898. He consulted directories as far back as they went; there never had been one of the name before. Then a time-slip from the future?

That was hopeless, so far as he could do anything about it, so he cast about for another solution. How about a parallel world?

That could be, certainly: some accident by which mail for that other Ochterlonie Building, the seven-story one, had (maybe just once) arrived in the wrong dimension.

He couldn't do anything to prove or disprove that, either. What he needed was a break.

He got it.

One morning in early summer his own mailbox in the downstairs hallway disgorged a long envelope, addressed to Mr. Samuel Wilson. The upper left-hand corner bore a printed return address: Time-Between-Time, 746 Ochterlonie Building, New York 3, N. Y. He raced upstairs, locked himself in the bathroom, the one place Mollie couldn't interrupt him, and tore the envelope open with trembling fingers.

It was a form letter, with the "Dear Mr. Wilson" not too accurately typed in. It enclosed one of those blue-printed envelopes in simulated handwriting. The letterhead carried the familiar impossible address, but no phone number.

Maybe it was chance, maybe it was ESP, but he himself had got onto Time-Between-Time's mailing list!

He had trouble focusing his eyes to read the letter.

Dear Mr. Wilson:

Would you invest $1 to get a chance at $1,000?

Of course you would, especially if, win or lose, you got your dollar back.

In this atomic age, yesterday's science fiction has become today's and tomorrow's science fact. Time-Between-Time, a new organization, is planning establishment of a publishing company to bring out the best in new books, both fact and fiction, in the field of science, appealing to people who have never been interested until now.

Before we start, we are conducting a poll to find out what the general public thinks and feels about our probabilities of success. We're asking for your co-operation.

Our statisticians have told us that from the answers to one question—which may look off the beam but isn't—we can make a pretty good estimate. Here it is:

If tomorrow morning a spaceship landed in front of your house, and from it issued a band of extraterrestrial beings, who might or might not be human in appearance, what, in your best judgment, would be your own immediate reaction? Check one, or if you agree with none of the choices, indicate in the blank space beneath what your personal reaction would probably be.

1. Phone for the police. 2. Attack the aliens physically. 3. Faint. 4. Run away. 5. Call for assistance to seize the visitors. 6. Greet them, attempt to communicate, and welcome them in the name of your fellow-terrestrials. 7. Other (please specify).

Return this letter, properly marked, in the enclosed envelope. To defray promotion expenses, enclose a dollar bill (no checks or money orders).

At the conclusion of this poll, all answers will be evaluated. The writer of the one which comes nearest to the answer reached by our electronic computer, which will be fed the same question, will receive $1,000 in dollar bills. Ties will receive duplicate prizes.

In addition, all participants, when our publishing firm has been established, will receive for their $1 a credit form entitling them to $1 off any book we publish.

Don't delay. Send in your answer NOW. Only letters enclosing $1 will be entered.

Very truly yours,

Time-Between-Time,

Orville K. Hesterson,

Sec.-Treas.

Sam Wilson read the letter three times. "It's crazy," he muttered. "It's a gyp."

What he ought to do was take the letter to the post office—Mr. Gross would be the one to see—and let them decide whether this Hesterson was using the mails to defraud. Let Mr. Gross and his department try to find 746 in the six-story Ochterlonie Building. As a faithful employee for 35 years, it was Sam's plain duty.

But then it would be out of his hands forever; he'd never even find out what happened. And he'd be back in the dull morass that retirement was turning out to be.

"Sam!" Mollie yelled outside the locked door. "Aren't you ever coming out of there?"

"I'm coming, I'm coming!" He put the letter and its enclosure back in the envelope and placed them in a pocket.

Time enough to decide that afternoon what he was going to do.

He escaped after lunch to what was becoming his refuge on a park bench. There he read the letter for the fourth time. For a long while he sat ruminating. About three o'clock he walked to the General Post Office—walking had become a habit hard to break—and hunted up the man who now had his old route, a youngster not more than 30 named Flanagan.

From the letter Sam extracted the return envelope.

"You been delivering any like this?" he asked.

Flanagan peered at it.

"Yeah," he said. "Plenty." He looked worried. "Gee, Wilson, I'm glad you came in. There's something funny about those deliveries, and I don't want to get in Dutch."

"Funny how?"

"My very first day on the route, I started up to the seventh floor of that building to deliver them—and there wasn't any seventh floor. So I asked the old elevator man—"

"Howie Mallory. I know him. He's been there for years."

"I guess so. Anyway, he said it was O. K. just to give them to him. He showed me a paper, signed with the name of this outfit, by the secretary or something—"

"Orville K. Hesterson," Sam said.

"That was it—saying that all mail for them was to be delivered to the elevator operator until further notice. So I've been giving it to him ever since—there's a big bunch every day. Is something wrong, Sam? Have I pulled a boner? Am I going to be in trouble?"

"No trouble. I'm just checking—little job they asked me to do for them, seeing I'm retired." Sam was surprised at the glibness with which that fib came out.

Flanagan looked still more worried. "He said their office was being remodeled or something, so he was looking after their mail till they could move in."

"Sure. Don't give it another thought." Another idea occurred to him; he lowered his voice. "I oughtn't to tell you this, Flanagan, but every new man on a route, they kind of check up on him the first few weeks, see if he's handling everything O.K. I'll tell them you're doing fine."

"Hey, thanks. Thanks a lot."

"Don't say anything about this. It's supposed to be secret."

"Oh, I won't."

Sam Wilson waved and walked out. He sat on the steps a while to think.

Was old Howie Mallory pulling a fast one? Was he Orville K. Hesterson? Had he cooked up a scheme to make himself some crooked money?

Three things against that. First, those nixies the first day: why wouldn't Mallory have told him the same thing he told Flanagan? Sam would have believed him, if he had said they were building an office on the roof and giving it a number.

Second, Howie just wasn't smart enough. Of course he could be fronting for the real crook. But Sam had known him for years, and old Howie had always seemed downright stupidly honest. A man doesn't suddenly turn into a criminal after a lifetime of probity.

Third, if this was some fraudulent scheme involving Mallory, nobody the old man knew—least of all the postman who used to deliver mail to that very building—would ever have been allowed to appear on the sucker list.

Sam Wilson thought some more. Then he hunted up the nearest pay phone and called Mollie.

"Mollie? Sam. Look, I just met an old friend of mine—" he picked a name from a billboard visible from the phone booth—"Bill Seagram, you remember him—oh, sure you do; you've just forgotten. Anyway, he's just here for the day and we're going to have dinner and see a show. Don't wait up for me. I might be pretty late.... No, I'm not phoning from Mulligan's.... Now you know me, Mollie; do I ever drink too much?... Yeah, sure, he ought to've asked you too, but he didn't. O.K., he's impolite. Aw, Mollie, don't be like that—"

She hung up on him.

Sam Wilson stood concealed in a doorway from which he could see the cramped lobby of the Ochterlonie Building. It was ten minutes before somebody entered it and rang for the elevator. The minute Howie Mallory started up with his passenger, Sam darted into the building and started climbing the stairs. He heard Mallory passing him, going down again, but the elevator wasn't visible from the stairway. On the sixth floor, after a quick survey to see that the hall was clear and the doors closed that he had to pass, he found the iron steps to the trapdoor.

The roof was just as empty as the other time he had visited it. No, it wasn't. In a corner by the parapet, weighted with a brick to keep it from blowing away, was a large paper bag. Sam picked up the brick and looked inside. It was stuffed with those blue-printed return envelopes.

He looked carefully about him. There were buildings all around, towering over the little old Ochterlonie Building. There were plenty of windows from which a curious eye could discern anything happening on that roof. But at night anybody in those buildings would be either working late or cleaning offices, with no reason whatever to go to a window; and Sam was sure nothing was going to happen till after dark.

It was a warm day and he had been carrying his coat. He folded it and put it down near the paper bag and sat on it with his back against the parapet. He cursed himself for not having had more foresight; he should have brought something to eat and something to read. Well, he wasn't going to climb down all those stairs and up again. He lighted his pipe and began waiting.

He must have dozed off, for he came to himself with a start and found it was almost dark. The paper bag was still there. It was just as well he had slept; now he'd have no trouble staying awake and watching. He might very well be there all night—in fact, he'd have to be, whether anything happened or not. The front door would be locked by now. Mollie would have a fit, but he had his alibi ready.

There was only one explanation left. Not time travel. Not alternate universes. Not an ordinary confidence game. Not—decidedly not—a hoax.

If he was wrong, then tomorrow morning he'd take the whole business to Mr. Gross. But he had a hunch he wasn't going to be wrong.

It was 12:15 by his wristwatch when he saw it coming.

It had no lights; nobody could have spotted it as it appeared suddenly out of nowhere and climbed straight down. It landed lightly as a drop of dew. The port opened and a small, spare man, very neatly dressed, as Sam could see with eyes accustomed to the darkness, stepped out. Orville K. Hesterson in person.

He tiptoed quickly to the paper bag. Then he saw Sam and stopped short. Sam reached out and grabbed a wrist. It felt like flesh, but he couldn't be sure.

"Who are you? What are you doing here?" the newcomer said in a strained whisper, just like a scared character in a soap opera. So he spoke English. Good: Sam didn't speak anything else.

"I'm from the United States Post Office," Sam replied suavely. Well, he had been, long enough, hadn't he?

"Oh. Well, now look, my friend—"

"You look. Talk. How much are you paying the elevator operator to put your mail up here every day?"

"Five dollars a day, in dollar bills, six days a week, left in the empty bag," answered Hesterson—it must be Hesterson—sullenly. "That's no crime, is it? Call this my office, and call that my rent. All I need an office for is to have somewhere to get my letters."

"Letters with money in them."

"We have to have funds for postage, don't we?"

"What about the postage on the first mailing list, before you got any dollars to pay for stamps?"

If it had been a little lighter, Sam would have been surer of the alarm that crossed Hesterson's face.

"I—well, we had to fabricate some of your currency for that. We regretted it—we aim to obey all local rules and regulations. As soon as we have enough coming in, we intend to send the amount to the New York postmaster as anonymous conscience money."

"How about the $1,000 prize? And those dollar book credits?"

"Oh, that. Well, we say 'when our publishing firm has been established,' don't we? That publishing thing is just a gimmick. As for the $1,000, we give no intimation of when the poll will end."

Sam tightened his grasp on the wrist, which was beginning to wriggle.

"I see. O.K., explain the whole setup. It sounds crazy to me."

"I couldn't agree with you more," said Mr. Hesterson, to Sam's surprise. "That's exactly what, in our own idiom, I told—" Sam couldn't get the name; it sounded like a grunt. "But he's the boss and I'm only a scout third class." His voice grew plaintive. "You can't imagine what an ordeal it is, almost every week, to have to land in a secluded place where I can hide the flyer, make my way to New York, and buy a bunch of stamps and mail a batch of letters in broad daylight. We can simulate your paper and printing and typing well enough, but"—that grunt again—"insists we use genuine stamps. I told you we try to follow all your laws, as far as we possibly can. It's very difficult for me to keep this absurd shape for long at a time; I'm exhausted after every trip. I can assure you, these little night excursions from the mother-ship to pick up the letters are the very least of my burdens!"

"What in time does your boss think he's going to gain by such a screwy come-on?"

"'In time'? Oh, just an idiomatic phrase. Like our calling our organization Time-Between-Time, time of course being just a dimension of space. I learned your tongue mostly from the B.B.C. and I don't always understand your speech in New York. My dear sir, do you here on this planet ask your bosses why they concoct their plans? Mine has a very profound mind; that's why he is the boss. All I know is that he persuaded the Council to try it out. A softening-up process—isn't that what you people call it when you use it in your silly wars with one another?"

"Softening for what?" But Sam Wilson knew the answer already.

"Why, for the invasion, of course," said Orville K. Hesterson, whose own name was probably a grunt. "Surely you must be aware that, with planetwide devastation likely and even imminent, every world whose inhabitants can live comfortably under extreme radiation is looking to yours—Earth, as you call it—as a possible area for colonization? So many planets are so terribly overcrowded—there's always a rush for a new frontier. We've missed out too often; this time we're determined to be first."

"I'll be darned," said Sam, "if I can see how that questionnaire would be any help to you."

"But it's elementary, as I believe one of your famous law-enforcers once declared. First of all, we're gaining a pretty good idea of what kind of reception we're likely to meet when we arrive, and therefore whether we're going to need weapons to destroy what will be left of the population, or can reasonably expect to take over without difficulty. We figure that a cross-section of one of your largest cities will be a pretty good indication, and we can extrapolate from that. In the second place, the question itself is deliberately worded to startle the recipients, who have never in their lives contemplated such a thing as an extraterrestrial visitor—"

"Not me. I'm a science fiction fan from way back. It's all old stuff to me."

Hesterson clicked his tongue—or at least the tongue he was wearing. "Oh, dear, that was an error. We tried particularly not to include on our lists subscribers to any of your speculative periodicals. That wasn't my mistake, thank goodness; it was another scout who had the horrible job of spending several days here and compiling the lists. Under your present low radioactivity it's real agony for us."

"I'll tell you one mistake you did make, though," said Sam angrily. "You ought to've arranged with the elevator man before your first lot of answers was due. If you want to know, that's how I got onto the whole thing. I'm a mail carrier—I'm retired now, but I was then—and I was the one supposed to deliver the first batch. Mallory—that's the elevator operator—laughed in my face and told me there wasn't any 746 in this building, and I had to take the letters back to the post office—on my last delivery!" Sam couldn't keep the bitterness out of his voice. "After 35 years—well, that's neither here nor there. But I didn't like that and I made up my mind to find out what was happening."

"So that's it. Oh, dear, dear. I'll have to compensate for that or I will be in trouble."

Sam had had enough. "You are in trouble right now," he growled, pushing the little alien back against the parapet. "We're staying right here till morning, and then I'm going to call for help and take you and your flying saucer or whatever it is straight to the F.B.I."

The counterfeit Mr. Hesterson laughed.

"Oh, no indeed you aren't," he said mildly. "I can slip right back into my own shape whenever I want to—the only reason I haven't done it yet is that then I wouldn't have the equipment to talk to you—and I assure you that you couldn't hold me then. On the contrary. As you just pointed out to me, I did make one bad error, and my boss doesn't like errors. I have no intention of making another one by leaving you here to spread the news."

"What do you mean?" Sam Wilson cried. For the first time, after the years of accustomedness to the idea of extraterrestrial beings, a thrill of pure terror shot through him.

"This," said the outsider softly.

Before Sam could take another breath, the wrist he was holding slid from his grasp, all of Mr. Hesterson slithered into something utterly beyond imagining, and Sam found himself enveloped in invisible chains against which he was unable to make the slightest struggle. He felt himself being lifted and thrown into the cockpit. Something landed on top of him—undoubtedly the package of prize entries and dollar bills. His last conscious thought was a despairing one of Mollie.

Sam Wilson, devoted mail carrier, was making a longer trip than any Persian courier ever dreamed of, and not snow, nor rain, nor heat, nor gloom of night could stay him from his appointed round.

But he may not be gone forever. If he can be kept alive on that planet in some other solar system, they plan to bring him back as Exhibit One whenever World War III has made Earth sufficiently radioactive for Orville K. Hesterson's co-planetarians to live here comfortably.

End of Project Gutenberg's Not Snow Nor Rain, by Miriam Allen deFord

*** END OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK NOT SNOW NOR RAIN ***

***** This file should be named 60725-h.htm or 60725-h.zip *****

This and all associated files of various formats will be found in:

http://www.gutenberg.org/6/0/7/2/60725/

Produced by Greg Weeks, Mary Meehan and the Online

Distributed Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

Updated editions will replace the previous one--the old editions will

be renamed.

Creating the works from print editions not protected by U.S. copyright

law means that no one owns a United States copyright in these works,

so the Foundation (and you!) can copy and distribute it in the United

States without permission and without paying copyright

royalties. Special rules, set forth in the General Terms of Use part

of this license, apply to copying and distributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works to protect the PROJECT GUTENBERG-tm

concept and trademark. Project Gutenberg is a registered trademark,

and may not be used if you charge for the eBooks, unless you receive

specific permission. If you do not charge anything for copies of this

eBook, complying with the rules is very easy. You may use this eBook

for nearly any purpose such as creation of derivative works, reports,

performances and research. They may be modified and printed and given

away--you may do practically ANYTHING in the United States with eBooks

not protected by U.S. copyright law. Redistribution is subject to the

trademark license, especially commercial redistribution.

START: FULL LICENSE

THE FULL PROJECT GUTENBERG LICENSE

PLEASE READ THIS BEFORE YOU DISTRIBUTE OR USE THIS WORK

To protect the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting the free

distribution of electronic works, by using or distributing this work

(or any other work associated in any way with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg"), you agree to comply with all the terms of the Full

Project Gutenberg-tm License available with this file or online at

www.gutenberg.org/license.

Section 1. General Terms of Use and Redistributing Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works

1.A. By reading or using any part of this Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic work, you indicate that you have read, understand, agree to

and accept all the terms of this license and intellectual property

(trademark/copyright) agreement. If you do not agree to abide by all

the terms of this agreement, you must cease using and return or

destroy all copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in your

possession. If you paid a fee for obtaining a copy of or access to a

Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work and you do not agree to be bound

by the terms of this agreement, you may obtain a refund from the

person or entity to whom you paid the fee as set forth in paragraph

1.E.8.

1.B. "Project Gutenberg" is a registered trademark. It may only be

used on or associated in any way with an electronic work by people who

agree to be bound by the terms of this agreement. There are a few

things that you can do with most Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

even without complying with the full terms of this agreement. See

paragraph 1.C below. There are a lot of things you can do with Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic works if you follow the terms of this

agreement and help preserve free future access to Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works. See paragraph 1.E below.

1.C. The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation ("the

Foundation" or PGLAF), owns a compilation copyright in the collection

of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works. Nearly all the individual

works in the collection are in the public domain in the United

States. If an individual work is unprotected by copyright law in the

United States and you are located in the United States, we do not

claim a right to prevent you from copying, distributing, performing,

displaying or creating derivative works based on the work as long as

all references to Project Gutenberg are removed. Of course, we hope

that you will support the Project Gutenberg-tm mission of promoting

free access to electronic works by freely sharing Project Gutenberg-tm

works in compliance with the terms of this agreement for keeping the

Project Gutenberg-tm name associated with the work. You can easily

comply with the terms of this agreement by keeping this work in the

same format with its attached full Project Gutenberg-tm License when

you share it without charge with others.

1.D. The copyright laws of the place where you are located also govern

what you can do with this work. Copyright laws in most countries are

in a constant state of change. If you are outside the United States,

check the laws of your country in addition to the terms of this

agreement before downloading, copying, displaying, performing,

distributing or creating derivative works based on this work or any

other Project Gutenberg-tm work. The Foundation makes no

representations concerning the copyright status of any work in any

country outside the United States.

1.E. Unless you have removed all references to Project Gutenberg:

1.E.1. The following sentence, with active links to, or other

immediate access to, the full Project Gutenberg-tm License must appear

prominently whenever any copy of a Project Gutenberg-tm work (any work

on which the phrase "Project Gutenberg" appears, or with which the

phrase "Project Gutenberg" is associated) is accessed, displayed,

performed, viewed, copied or distributed:

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no

restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it

under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included with this

eBook or online at www.gutenberg.org. If you are not located in the

United States, you'll have to check the laws of the country where you

are located before using this ebook.

1.E.2. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is

derived from texts not protected by U.S. copyright law (does not

contain a notice indicating that it is posted with permission of the

copyright holder), the work can be copied and distributed to anyone in

the United States without paying any fees or charges. If you are

redistributing or providing access to a work with the phrase "Project

Gutenberg" associated with or appearing on the work, you must comply

either with the requirements of paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 or

obtain permission for the use of the work and the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark as set forth in paragraphs 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.3. If an individual Project Gutenberg-tm electronic work is posted

with the permission of the copyright holder, your use and distribution

must comply with both paragraphs 1.E.1 through 1.E.7 and any

additional terms imposed by the copyright holder. Additional terms

will be linked to the Project Gutenberg-tm License for all works

posted with the permission of the copyright holder found at the

beginning of this work.

1.E.4. Do not unlink or detach or remove the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License terms from this work, or any files containing a part of this

work or any other work associated with Project Gutenberg-tm.

1.E.5. Do not copy, display, perform, distribute or redistribute this

electronic work, or any part of this electronic work, without

prominently displaying the sentence set forth in paragraph 1.E.1 with

active links or immediate access to the full terms of the Project

Gutenberg-tm License.

1.E.6. You may convert to and distribute this work in any binary,

compressed, marked up, nonproprietary or proprietary form, including

any word processing or hypertext form. However, if you provide access

to or distribute copies of a Project Gutenberg-tm work in a format

other than "Plain Vanilla ASCII" or other format used in the official

version posted on the official Project Gutenberg-tm web site

(www.gutenberg.org), you must, at no additional cost, fee or expense

to the user, provide a copy, a means of exporting a copy, or a means

of obtaining a copy upon request, of the work in its original "Plain

Vanilla ASCII" or other form. Any alternate format must include the

full Project Gutenberg-tm License as specified in paragraph 1.E.1.

1.E.7. Do not charge a fee for access to, viewing, displaying,

performing, copying or distributing any Project Gutenberg-tm works

unless you comply with paragraph 1.E.8 or 1.E.9.

1.E.8. You may charge a reasonable fee for copies of or providing

access to or distributing Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works

provided that

* You pay a royalty fee of 20% of the gross profits you derive from

the use of Project Gutenberg-tm works calculated using the method

you already use to calculate your applicable taxes. The fee is owed

to the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm trademark, but he has

agreed to donate royalties under this paragraph to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation. Royalty payments must be paid

within 60 days following each date on which you prepare (or are

legally required to prepare) your periodic tax returns. Royalty

payments should be clearly marked as such and sent to the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation at the address specified in

Section 4, "Information about donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation."

* You provide a full refund of any money paid by a user who notifies

you in writing (or by e-mail) within 30 days of receipt that s/he

does not agree to the terms of the full Project Gutenberg-tm

License. You must require such a user to return or destroy all

copies of the works possessed in a physical medium and discontinue

all use of and all access to other copies of Project Gutenberg-tm

works.

* You provide, in accordance with paragraph 1.F.3, a full refund of

any money paid for a work or a replacement copy, if a defect in the

electronic work is discovered and reported to you within 90 days of

receipt of the work.

* You comply with all other terms of this agreement for free

distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm works.

1.E.9. If you wish to charge a fee or distribute a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work or group of works on different terms than

are set forth in this agreement, you must obtain permission in writing

from both the Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation and The

Project Gutenberg Trademark LLC, the owner of the Project Gutenberg-tm

trademark. Contact the Foundation as set forth in Section 3 below.

1.F.

1.F.1. Project Gutenberg volunteers and employees expend considerable

effort to identify, do copyright research on, transcribe and proofread

works not protected by U.S. copyright law in creating the Project

Gutenberg-tm collection. Despite these efforts, Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, and the medium on which they may be stored, may

contain "Defects," such as, but not limited to, incomplete, inaccurate

or corrupt data, transcription errors, a copyright or other

intellectual property infringement, a defective or damaged disk or

other medium, a computer virus, or computer codes that damage or

cannot be read by your equipment.

1.F.2. LIMITED WARRANTY, DISCLAIMER OF DAMAGES - Except for the "Right

of Replacement or Refund" described in paragraph 1.F.3, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation, the owner of the Project

Gutenberg-tm trademark, and any other party distributing a Project

Gutenberg-tm electronic work under this agreement, disclaim all

liability to you for damages, costs and expenses, including legal

fees. YOU AGREE THAT YOU HAVE NO REMEDIES FOR NEGLIGENCE, STRICT

LIABILITY, BREACH OF WARRANTY OR BREACH OF CONTRACT EXCEPT THOSE

PROVIDED IN PARAGRAPH 1.F.3. YOU AGREE THAT THE FOUNDATION, THE

TRADEMARK OWNER, AND ANY DISTRIBUTOR UNDER THIS AGREEMENT WILL NOT BE

LIABLE TO YOU FOR ACTUAL, DIRECT, INDIRECT, CONSEQUENTIAL, PUNITIVE OR

INCIDENTAL DAMAGES EVEN IF YOU GIVE NOTICE OF THE POSSIBILITY OF SUCH

DAMAGE.

1.F.3. LIMITED RIGHT OF REPLACEMENT OR REFUND - If you discover a

defect in this electronic work within 90 days of receiving it, you can

receive a refund of the money (if any) you paid for it by sending a

written explanation to the person you received the work from. If you

received the work on a physical medium, you must return the medium

with your written explanation. The person or entity that provided you

with the defective work may elect to provide a replacement copy in

lieu of a refund. If you received the work electronically, the person

or entity providing it to you may choose to give you a second

opportunity to receive the work electronically in lieu of a refund. If

the second copy is also defective, you may demand a refund in writing

without further opportunities to fix the problem.

1.F.4. Except for the limited right of replacement or refund set forth

in paragraph 1.F.3, this work is provided to you 'AS-IS', WITH NO

OTHER WARRANTIES OF ANY KIND, EXPRESS OR IMPLIED, INCLUDING BUT NOT

LIMITED TO WARRANTIES OF MERCHANTABILITY OR FITNESS FOR ANY PURPOSE.

1.F.5. Some states do not allow disclaimers of certain implied

warranties or the exclusion or limitation of certain types of

damages. If any disclaimer or limitation set forth in this agreement

violates the law of the state applicable to this agreement, the

agreement shall be interpreted to make the maximum disclaimer or

limitation permitted by the applicable state law. The invalidity or

unenforceability of any provision of this agreement shall not void the

remaining provisions.

1.F.6. INDEMNITY - You agree to indemnify and hold the Foundation, the

trademark owner, any agent or employee of the Foundation, anyone

providing copies of Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works in

accordance with this agreement, and any volunteers associated with the

production, promotion and distribution of Project Gutenberg-tm

electronic works, harmless from all liability, costs and expenses,

including legal fees, that arise directly or indirectly from any of

the following which you do or cause to occur: (a) distribution of this

or any Project Gutenberg-tm work, (b) alteration, modification, or

additions or deletions to any Project Gutenberg-tm work, and (c) any

Defect you cause.

Section 2. Information about the Mission of Project Gutenberg-tm

Project Gutenberg-tm is synonymous with the free distribution of

electronic works in formats readable by the widest variety of

computers including obsolete, old, middle-aged and new computers. It

exists because of the efforts of hundreds of volunteers and donations

from people in all walks of life.

Volunteers and financial support to provide volunteers with the

assistance they need are critical to reaching Project Gutenberg-tm's

goals and ensuring that the Project Gutenberg-tm collection will

remain freely available for generations to come. In 2001, the Project

Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation was created to provide a secure

and permanent future for Project Gutenberg-tm and future

generations. To learn more about the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation and how your efforts and donations can help, see

Sections 3 and 4 and the Foundation information page at

www.gutenberg.org Section 3. Information about the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

The Project Gutenberg Literary Archive Foundation is a non profit

501(c)(3) educational corporation organized under the laws of the

state of Mississippi and granted tax exempt status by the Internal

Revenue Service. The Foundation's EIN or federal tax identification

number is 64-6221541. Contributions to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation are tax deductible to the full extent permitted by

U.S. federal laws and your state's laws.

The Foundation's principal office is in Fairbanks, Alaska, with the

mailing address: PO Box 750175, Fairbanks, AK 99775, but its

volunteers and employees are scattered throughout numerous

locations. Its business office is located at 809 North 1500 West, Salt

Lake City, UT 84116, (801) 596-1887. Email contact links and up to

date contact information can be found at the Foundation's web site and

official page at www.gutenberg.org/contact

For additional contact information:

Dr. Gregory B. Newby

Chief Executive and Director

gbnewby@pglaf.org

Section 4. Information about Donations to the Project Gutenberg

Literary Archive Foundation

Project Gutenberg-tm depends upon and cannot survive without wide

spread public support and donations to carry out its mission of

increasing the number of public domain and licensed works that can be

freely distributed in machine readable form accessible by the widest

array of equipment including outdated equipment. Many small donations

($1 to $5,000) are particularly important to maintaining tax exempt

status with the IRS.

The Foundation is committed to complying with the laws regulating

charities and charitable donations in all 50 states of the United

States. Compliance requirements are not uniform and it takes a

considerable effort, much paperwork and many fees to meet and keep up

with these requirements. We do not solicit donations in locations

where we have not received written confirmation of compliance. To SEND

DONATIONS or determine the status of compliance for any particular

state visit www.gutenberg.org/donate

While we cannot and do not solicit contributions from states where we

have not met the solicitation requirements, we know of no prohibition

against accepting unsolicited donations from donors in such states who

approach us with offers to donate.

International donations are gratefully accepted, but we cannot make

any statements concerning tax treatment of donations received from

outside the United States. U.S. laws alone swamp our small staff.

Please check the Project Gutenberg Web pages for current donation

methods and addresses. Donations are accepted in a number of other

ways including checks, online payments and credit card donations. To

donate, please visit: www.gutenberg.org/donate

Section 5. General Information About Project Gutenberg-tm electronic works.

Professor Michael S. Hart was the originator of the Project

Gutenberg-tm concept of a library of electronic works that could be

freely shared with anyone. For forty years, he produced and

distributed Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks with only a loose network of

volunteer support.

Project Gutenberg-tm eBooks are often created from several printed

editions, all of which are confirmed as not protected by copyright in

the U.S. unless a copyright notice is included. Thus, we do not

necessarily keep eBooks in compliance with any particular paper

edition.

Most people start at our Web site which has the main PG search

facility: www.gutenberg.org

This Web site includes information about Project Gutenberg-tm,

including how to make donations to the Project Gutenberg Literary

Archive Foundation, how to help produce our new eBooks, and how to

subscribe to our email newsletter to hear about new eBooks.