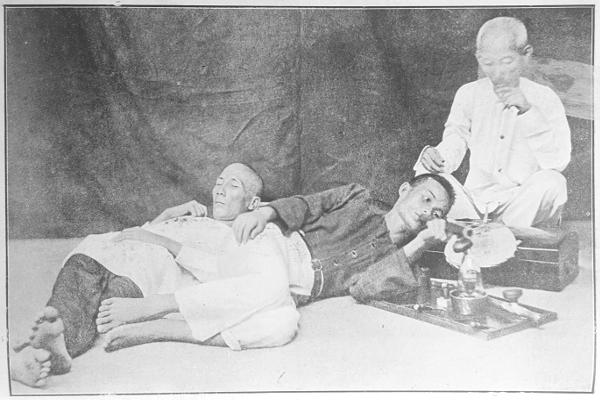

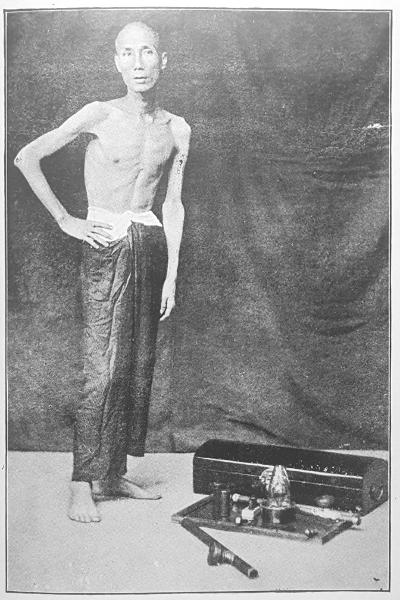

Group of Opium Smokers

Group of Opium Smokers

BY

ROY. K. ANDERSON, F.R.S.A.

Superintendent, Burma Excise Department

ILLUSTRATED

CALCUTTA and SIMLA

THACKER, SPINK & CO.

1922

PRINTED BY

THACKER, SPINK & CO.

CALCUTTA

At a time when the drug-evil, as it is called, is attracting so much attention all over the world, it does not seem out of place to tell the public something about how conditions in regard to it obtain in India and Burma. As far as I have been able to ascertain there is no literature on this subject outside “blue books,” and those admirable compilations are notoriously dry reading. A novel called “Dope” by Sax Rohmer professes to deal with the drug-evil and the traffic in drugs in the West; but it is a novel; has a hero, a heroine, a forbidding type of detective, and some degenerates, and a few impossible Chinamen in it, to give verisimilitude to the title and all that it implies.

I do not profess to write as an authority on the subjects I have taken up. I realise that there are scores of others more experienced, and infinitely better able to make a book on these subjects than I am; but there seems to be little hope of their ever getting the better of their modesty and appearing in print. I write[iv] of what I have seen for myself, and ventilate opinions I have formed which I expect no one to subscribe to who differs from them. My readers may rest assured, however, that what I relate is true. I have not consciously exaggerated, nor have I suppressed facts. I write on a subject in which I am interested; and, if the attention that has at different times been given to my verbal accounts is an indication of something more than the polite toleration of the raconteur, then there are others also who are interested, and I need offer no apologies for my attempt to supply a deficiency in the bookshelves of those who want more information.

A preface often affords the writer an opportunity of performing a pleasant duty. That which I have to perform is to record my thanks to Mr. F. W. Dillon, Barrister, and author of “From an Indian Bar Room,” for the trouble he took in reading the manuscript, and his many helpful suggestions.

R. K. ANDERSON.

Redfern,

26th March, 1921.

| Page | ||

| Preface | iii | |

| Chapter | ||

| I. | Smuggling and Smugglers | 1 |

| II. | Bribery and Corruption | 9 |

| III. | Informers and Information | 14 |

| IV. | Some Anecdotes of Smugglers and Smuggling | 20 |

| V. | More Anecdotes | 28 |

| VI. | Observations on Smugglers and Smuggling | 33 |

| VII. | Opium | 35 |

| VIII. | Opium Smoking and Opium Eating | 44 |

| IX. | Some Observations on the Opium Habit | 51 |

| X. | Morphia | 57 |

| XI. | Cocaine | 65 |

| XII. | Hemp Drugs | 75 |

| Appendix. | An Historical Note on Opium in India and Burma | 82 |

| Group of Opium Smokers | Frontispiece |

| Facing page |

|

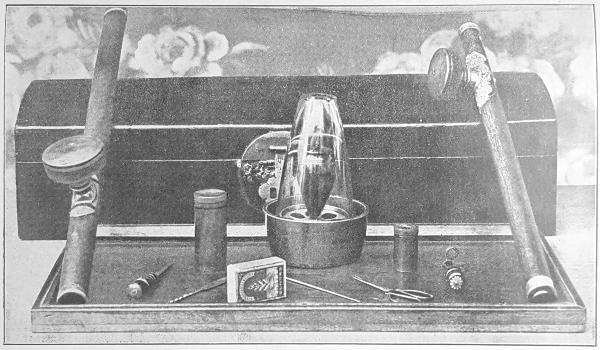

| An Excessive Opium Smoker | 40 |

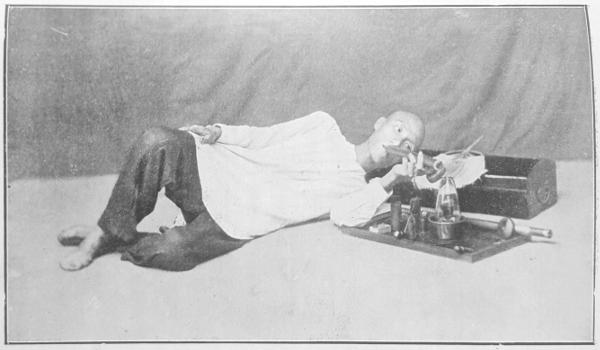

| Opium Smokers’ Appliances | 46 |

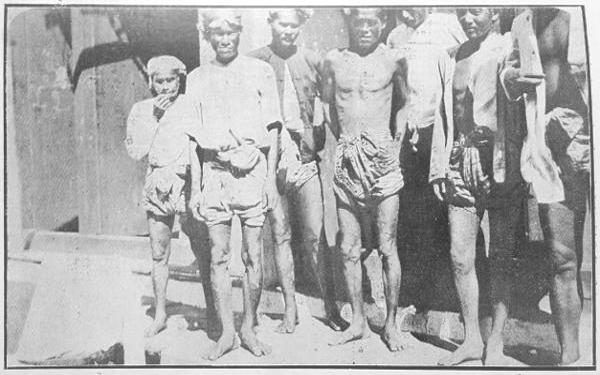

| Preparing to Smoke Opium | 48 |

| Chinaman Smoking Opium | 50 |

| Group of Morphia Injectors | 58 |

| An Indian Morphinist | 62 |

| A Burman Cocaine Eater | 72 |

Everybody is a smuggler at heart!

Our innate free-trade instincts and love of liberty revolt against what we look upon as uncalled for interference with our rights when we are called upon to declare and pay duty on a box of cigars or a bottle of whisky when we disembark at a Customs port; and we look upon evasions of these obligations, not as evidences of moral obliquity, but as a very proper exercise of the exemption which we claim as our right. On the whole, this point of view is to be sympathized with, and in the case of such innocuous articles as laces, scent, and feathers, it is to be excused; the mysteries of the revenue law, and the underlying principles of taxation, are unfamiliar to most of us. But a greater degree of culpability must be attached to those who seek to evade the law by the illicit importation of articles whose unrestricted use produces nothing but harm; and while the former class of delicts may be classed as mere revenue offences, the latter must be treated as crimes and severely punished as such.

It is in the nature of things that articles which have come to be looked upon as necessaries of life, such as tea, tobacco, wine and spirits, should be taxed moderately; and indeed, were any attempt made to render them less easily obtained by raising the taxes on them, unless this course was vital in the interests of the country, there would be just reasons for profound popular dissatisfaction and disgust; but in the matter of noxious intoxicating drugs the case is reversed, and authoritative opinion inclines to the highest taxation, or even to total prohibition. Opium is taxed to a point little short of prohibition; morphia and cocaine are entirely prohibited to the public except for medical purposes; and hemp drugs are highly taxed in India, and totally prohibited in Burma. Those who quarrel with this state of things are such as have become habituated to these drugs, and of this class there is, unhappily, a large number, so large a number indeed, that their demand for a regular and sufficient supply constitutes a rich market, a market which is supplied by the smuggler who reaps abundant profits.

As in the case of other articles of commerce—and smuggling is as much a branch of commerce as the traffic in rice or jute—the scarcity or abundance of supply of drugs is what regulates their price in the illicit market. Normally, opium is sold from Government Opium Shops at from Rs. 100 to Rs. 123 a seer. Illicitly, it costs from Rs. 200 to Rs. 300 a seer, and[3] when scarce, from Rs. 350 to Rs. 400 a seer. Illicitly, cocaine and morphia are sold at from five to six times the chemist’s price. It is true that the smuggler has to pay and maintain a large staff of assistants, and has to bear other heavy expenses, but the net profit he eventually gets is a very substantial one.

It is impossible to entirely prevent smuggling: the interested motives of mankind will always prompt them to attempt it. All that the Government can do is to compromise with an offence which, whatever the criminal law on the subject may say, appears to the mind of the smuggler, and of the drug habitué he supplies, as not at all equalling in turpitude those acts which are clear breaches of the elementary principles of ethics.

To the generality of people the smuggler is a bold, bad man with a fierce, heavily-whiskered face, and armed to the teeth with knives, pistols, and other lethal accoutrements. His surroundings are a rugged cliff, with a roaring surf at its feet; while a dimly lit cave, stocked with barrels of spirit and bales of tobacco, completes the mental picture. In reality the smuggler—the Indian smuggler at any rate—is nothing of the sort. To all appearances he is a respectable, well-to-do, easy-going merchant with a flourishing business in piece-goods, rice, or timber. But he is a thorough-paced smuggler for all that, and his business is merely a blind to his real occupation which is the importation and traffic in opium, cocaine, morphia, and[4] hemp-drugs. It is this business which is the real source of his wealth; it is his mind that directs and accomplishes great ventures in smuggling.

To be successful as a smuggler, a man needs to have more than ordinary ability. His powers of organization, and the ability to rapidly appreciate a situation, must be of the first order, and in addition, he must be endowed with an unusually large measure of low cunning and deceit. It is true that the smuggler’s plans sometimes miscarry, but this is usually owing to treachery on the part of one of his assistants. The possibility of such treachery exemplifies the need the smuggler has for a strong personality and ability to judge character, and appraise men at their true worth; its infrequency testifies to the possession by smugglers of these qualities in an unusual degree.

It must not be supposed that the smuggler takes a very active part in his nefarious traffic; it is doubtful whether he ever sees the drugs for the importation of which he is responsible. His assistants look to all minor details, he only supplying the necessary money, and directing operations as a general directs an army in the field. His host of underlings realise only too well how relentless would be the fate that would overtake them were they to “give away” their employer, for those who have proved faithless to their trust have not survived long enough to enjoy the fruits of their perfidy! The faithful ones know they have nothing to lose or fear. Fines are paid by their employer, and[5] jail has no terrors for them, because their families are provided for by the smuggler while they are away, and they return to their employment and the society of their companions after release from a course of hard, healthful, muscle-forming labour.

So far I have dealt exclusively with the man who smuggles in a large and extended way. He might be likened to the big importer of ordinary business. But, as in ordinary business, there are the retailers: those who take the goods to the consumer. These men operate up-country, in the sense that they work in the interior of the country. They may be agents of the big men, or they may be merely his customers; but except that their activities are confined, sometimes within the limits of a single district, they are otherwise similar to the big men who live in the cities. More often than not these men take an active and personal part in disseminating drugs, and consequently coming frequently into contact with the authorities, are more often brought to book for their misdemeanours. But they do not have much at stake, and rarely risk more than they can afford to lose if plans go wrong. Of course, there are these men in big cities also; as a matter of fact there are a host of them in every big city. To the square mile, there are many more consumers in a city than in the interior, and as the big smuggler cannot be troubled with retailing minute quantities of drugs, there is plenty to do for the lesser lights.

Why is it that these importers are never brought to book, is a question that might reasonably be asked. The answer is simple. It is because they never by chance handle the goods; they never allow it into their houses. That a certain man is a smuggler is well known to the authorities. In fact, the suspect will cheerfully admit it; he will even go as far as telling them how it was that they failed to seize his last consignment of contraband, and defy them to seize the next one he expects to import! But he is perfectly acquainted with the law, and he knows that he cannot be touched unless the contraband is found in his actual possession, or, under such circumstances, within his house or its precincts, that possession of it cannot be ascribed to anyone but himself. The law prescribes a punishment for any person who, according to general repute, earns his living, wholly or in part, by opium or morphia trafficking. The smuggler evades the first part of this provision by keeping a mercantile business going; and relies upon his personality, and the dread he inspires in those who might otherwise seek to interfere with him, for avoiding the second. The instinctive reluctance of respectable people to make themselves party to judicial proceedings, and a very understandable fear of extremely unpleasant consequences to themselves, deters them from coming forward to give evidence against the smuggler, and this is a great handicap to this very excellent piece of legislation. All that the executive can hope to do is to seize as much of his contraband as[7] possible, and so, gradually, deprive him of the means to carry on his trade.

Smugglers have been reduced to impotence in this way, by repeated seizure of their wares, but their number is not numerous. The weak link in the chain that can be wound round the smuggler is, indubitably, the corrupt preventive officer. It is regrettable, but nevertheless true, that a proportion of the preventive staff is corrupt and amenable to bribes. The smuggler pays them handsomely to keep their eyes closed, and their mouths shut, and being poorly paid by Government the temptation to bribery, which swells their monthly incomes to four or five times what they legitimately earn, is too great to resist. Besides this, many of the men recruited are not of the type most suitable. Their ideals of honesty are nebulous, self-respect to them consists merely in wearing clean clothes. It is a fact that a certain official once appointed his man-servant to the subordinate grade of a preventive department. Rumour had it that this servant was brother to the woman this official was keeping as his mistress, but that was mere scandal, and probably untrue. At the same time, one cannot expect much from a staff which can be recruited in so haphazard a manner. In other walks of life, the need for cautious recruitment is not so vital, and the need to pay for honesty is not so great as in departments whose duty it is to safeguard the revenue, and ensure the moral welfare of the people. It should be made a principle[8] that for every ten rupees paid for actual work, fifty rupees will be paid for its honest performance. The need for this is accentuated in departments in which cupidity, which exists to a greater or less extent in every man, is excited and tempted to the utmost.

No matter how powerful and reckless of consequences a smuggler may be, there is, nevertheless, a lurking respect in his bosom for the myrmidons of the Law. It is to his interest to have the authorities on his side, and, as he cannot have them on other terms, he must pay them handsomely. An excise or police officer, especially if he be of the lower ranks, can make it uncommonly uncomfortable for a smuggler; and it may be taken for granted that a smuggler is not completely satisfied until he has a large proportion of the preventive staff in his pay. To some, however, he will pay nothing because he has nothing to fear from incapables; some who occasionally come in his way he will tip with the economy of the uncle who tips his nephew; but to the able ones, the ones that can make it very warm for him, he will pay handsome monthly salaries, and he will look upon the outlay as money well invested. It is in this way that the smuggler keeps his traffic going; it is thus that he makes it possible to smuggle with profit.

Now, the preventive can only prevent by seizing contraband articles; so that it stands to reason that[10] its efficiency, and the ability of the individuals who compose it, must be judged largely by results; by the number of arrests made, and the quantity of contraband seized. An able officer who makes no hauls may be not unjustly put down as a bribe-taker, and a chief who knows that there is lots of contraband to be seized for the trying, will come down heavily on such a subordinate.

What does the smuggler do when the well-paid watchdog of the Law comes to him and tells him that he will be obliged to seize some, if not all, of the smuggler’s next consignment of opium, because the game is, to all intents and purposes, up? Does he wring his hands and roundly curse his ill luck? No; he merely smiles and advises the watchdog to stand at the corner of such-and-such a street, near so-and-so’s shop between certain hours next morning, and search the man who passes him with a spotted bandanna round his neck, and a bundle under his right arm. The watchdog acts on the advice, searches the man with the spotted bandanna, finds two cakes of opium, and walks the culprit off to the police station. For this he is commended and paid a reward; the smuggler gets off with the loss of two cakes of opium instead of the hundred he stood to lose; and the man with the spotted bandanna who is ultimately sent to prison for six months, merely fulfils the duty for which he is paid a regular monthly salary.

The foregoing is an example of the methods of smugglers, and of the cupidity of some of the staff employed by Government to guard its revenues. But it is only one. It would weary the reader to be told of the scores of other means employed. The smuggler, knowing that a certain officer is financially embarrassed, will approach him with the offer of a loan, and accept a note of hand for the accommodation. That note of hand releases the smuggler from all further obligation to pay the officer in question. He is well aware that certain dismissal of the latter must result if he shows the scrap of paper in the proper quarter. He has the unfortunate man completely in his hands. But it is obvious that there can be little to fear from a man who provides such damning evidence against himself.

People might well ask how it is that so much corruption can go on and yet no one be caught and punished. Now, it is a well-known principle of evidence that one man’s word is as good as another’s, and in law, no matter how convincing the truth of a man’s story might be, it must usually be corroborated before a magistrate will convict. The giving and receiving of bribes are, by their very nature, secret transactions—transactions to which there are no independent witnesses, so that it is very rarely that the charge can be brought home; and it is usually only those cases in which a confirmed bribe-taker has been lured into a trap, skilfully laid with the aid of marked notes or[12] coins, which have a satisfactory conclusion. It must, moreover, be borne in mind that the giver or offerer of a bribe is just as much liable in law as the receiver or solicitor of it; so that it is seldom that a complaint to a magistrate is made.

The two anecdotes I give here will afford the reader food for thought:

X was a responsible officer. He had the control of a district, and was widely respected. One afternoon, when at office, he had occasion to leave his room, and on his return to it, found ten one-hundred rupee notes under a paperweight on his table. He well knew who had placed them there. He took three of these notes to his superior officer, and with much apparent indignation, handed them to him, and asked that the sum be credited to Government. The guileless superior, ever after thought highly of X’s honesty, and reported on him in flattering terms. X became a richer man by seven hundred rupees!

Now for the second story:

Y was one night visited by a smuggler who produced a bag containing five hundred rupees, and offered the money as a bribe. Y stormed at him, and calling in his men, had the smuggler arrested, and sent up for trial on a charge of offering a bribe. The money was produced and counted in court. “How many rupees are there there?” enquired the smuggler. “Five hundred rupees,” replied the magistrate. “Oh!” said the rascal, “The bag had a thousand rupees in it[13] when I gave it to the sahib!” And Y was generally regarded as a taker of bribes for the rest of his official life. So does fate sometimes serve the virtuous!

I have given the seamy side of things here. There are, however, many excellent and deserving men in preventive departments—men who would rather stay poor than sell their honour.

Of all those who threaten the smuggler with arrest and loss, the informer is the one he fears most, and accordingly regards with bitter hatred as his greatest foe.

Without information, the hands of the executive are tied; without informers, they would be wholly ineffective; and except for a chance seizure now and then, there would be little for them to do. As things are, the organization of a detective department is so linked up with informers and information that one finds it difficult to conceive of its existing with these eliminated. Detectives of the Sherlock Holmes type exist only in fiction, and although it goes without saying that powers of observation above the ordinary, and an intimate knowledge of men are indispensable in a detective, it is equally indispensable that a detective, as things are, must rely upon information if he wishes successfully to solve any problem of crime.

In writing about informers, I deal mainly with the professional blackguards who make a regular living out of giving information. I do not include those who, to work off a grudge, or who, having seen a crime[15] committed, lodge information in the proper quarter.—I do not look upon these as informers. The first is a mean-minded person; the second, one who has a very proper conception of his duty towards society. But the man I deal with is essentially a blackguard, and a very despicable blackguard at that. He has only one object in view when he gives information, and that object is money. He is not burdened with notions of his duty as a citizen. If there was no money to be made out of giving information, he would be the last to go a step out of his way to give any; but he recognizes his value as an important factor in detection, places a price on it, and is paid generously.

I have often been asked by magistrates whether my informers were respectable men. I have felt no hesitation in answering the question emphatically in the negative, and I have no doubt I often set them wondering. But one has only to give the matter a moment’s consideration to see how diametrically opposed to all one’s notions of fair-play and honour must be the nature and calling of an informer. He must for a time pose as the friend and confidant of his victim, and then turn traitor; and he must bribe, coerce, and wheedle from their allegiance scores of subordinates who would otherwise serve their masters with unswerving loyalty. He is the tempter in excelsis; he is unscrupulous in the extreme; he is utterly bad. But for all this, he is, as I have already said, a very necessary link in the chain of detection, and we may, like the[16] pharisee, take comfort in the thought that we are not as other men are—even as these informers! The “unco gude” would find a monotonous sameness in their existence if there were none to set-off their unco gudeness!

Nowhere is the need for sharp-witted informers so keenly felt as in departments whose duty it is to prevent smuggling, and it may be taken for granted that the greater the blackguard the fellow is, the more useful he will be, and the more useful an informer is to the executive, the greater danger he goes in of losing his life (because the smuggler does not hesitate as to the means he employs in removing obstacles from his path). The authorities have therefore to consider these things when they come to pay the informer. The legislature also protects him by providing that no officer shall be compelled in a law court to disclose the name of his informer. That advantage is duly taken of this provision there need be no doubt. The officer who gives up the name of his informer has little further information to expect, as the informer very naturally values his life, and will give no information to an indiscreet and injudicious officer.

That the authorities are often imposed upon by informers is a matter of course. There are lots of men in this world who would like to pay off an old score against another, and an easy way to do this is to lodge an information against him. A search of the premises occupied by the suspect results, and although nothing[17] may be found, the attention of the neighbourhood is attracted, and for some time the search is a topic of conversation, which is by no means pleasant for the man whose house is searched. The disgrace attending such an occurrence is intensified if the householder happens to be a man who is respected as upright and honest. Severe punishment is provided by the law for givers of false information, but such cases are happily not numerous.

To take action against an informer for giving false information usually results in deterring genuine informers from giving genuine information; for there are factors which operate against the success of the genuine informer. For instance, the object searched for may be removed just before the search is made, or even during the search, and a blank is drawn. To prosecute the informer for giving false information in such circumstances would be manifestly unjust. If he were prosecuted, other informers would not run the risk of giving information and work would come to a standstill. Where, then, is the line to run? This is a question which confronts the executive with ever-increasing perplexity. It seems to be better to disregard the stray cases of false informing, than to jeopardise the entire preventive department’s being. A certain officer, suspecting that a search had been made on false information, issued an order, ex cathedra, that all informations should be verified before search was made. As the only way in which information can be[18] verified is by making a search, it is not clear to what extent this order was conceived in a spirit of bumptiousness, and how much of it in ignorance.

“Planting,” or the fabrication of false evidence, is a favourite and much practised trick of the informer. By means best known to himself he introduces something incriminating into the house of a person against whom he has a spite, and lays an information. A search is made, the stuff is found, and very often an innocent man is fined or sent to jail. Against this there seems to be no remedy, except the employment of well-known, reliable informers, and also a sort of intuition which develops with experience in officers themselves.

In olden days, when coastguards did not exist, Cornwall was a hot-bed of smuggling, and the temper of the Cornishmen towards informers can be gauged by the following story which has much in it that is apropos:—

The Rev. R. S. Hawker, of the parish of Morwenstowe, relates how on one occasion a predecessor of his presided, as the custom was, at a parish feast, in cassock and bands, and presented, with his white hair and venerable countenance, quite an apostolic aspect and mien. On a sudden, a busy whisper among the farmers at the lower end of the table attracted his notice, interspersed as it was with sundry nods and glances towards himself. At last one bolder than the rest addressed him, and said that they had a great wish to ask his reverence a question, if he would kindly grant them a reply; it was[19] on a religious subject that they had dispute, he said. The bland old gentleman assured them of his readiness to yield them any information in his power, but what was the point in dispute? “Why, sir, we wish to be informed if there are not sins which God Almighty will never forgive?” Surprised, and somewhat shocked, he told them that he trusted there were no transgressions common to themselves, but if repented of and abjured, they might clearly hope to be forgiven. But with natural curiosity, he inquired what sorts of iniquities they contemplated as too vile for pardon. “Why, sir,” replied the spokesman, “we thought that if a man should find out where run-goods was deposited, and should inform the Gauger, that such a villain was too bad for mercy!”

As an inducement to seize contraband, Government pays its preventive staff money-rewards which bear a ratio to the value of the stuff seized, and the ability displayed in seizing it; and an officer who is active and conscientious very often can earn in this way from three to four times the amount of his monthly salary. But the seizing of contraband is by no means easy, as the smuggler has brought concealment to a fine art, and there seems to be no end to the ingenuity which may be exercised by him in getting his consignments through safely to their destination. A few examples will serve to demonstrate this.

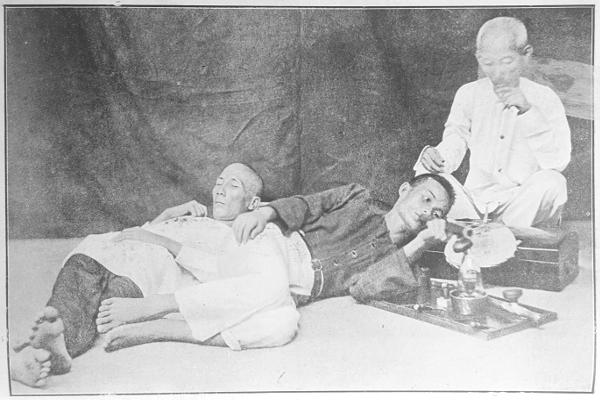

Vigorous search had failed to bring to light the cocaine which was reported to be on board the S.S. “Contrebandier” from Marseilles, and the search party were about to reluctantly abandon their quest when attention was directed to a pile of bundles of planks, each bundle consisting of from four to six half-inch planks, bound together at each end with iron bands. More from curiosity than with any idea of discovering cocaine, one of these bundles was pulled apart. The[21] top plank was found to be intact, and so was the bottom one, but the intervening planks had had spaces cut through them which were packed with one-ounce packets of cocaine. A large quantity of the alkaloid, valued at several thousands of rupees, was found. An illustration to make the method clear is shown.

Top plank removed.

Bundle of planks.

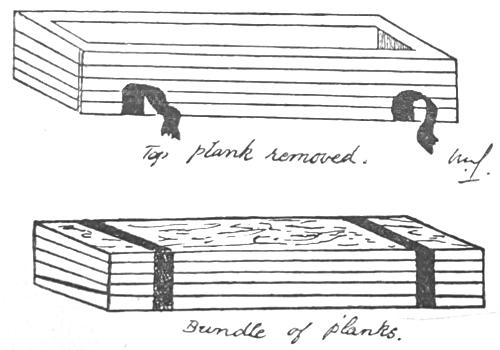

Another example: The weekly steamer from India had come into a Burma port, and the deck-passengers had been lined up on the pier for inspection by the Customs officers. An excise officer on the pier was made curious by four natives of India, whose only effects consisted of earthen pots of water containing small fishes. Knowing that the place to which these men had come abounded with fish of the best kinds, he was not convinced when they explained that they had brought these small fry to stock the local tanks[22] with. A closer scrutiny disclosed the fact that whereas by percolation the outsides of the pots ought to have been wet, these were quite dry. Measurements taken with his walking stick inside a pot and outside it disagreed too greatly to leave any doubt of the existence of a false bottom, and on breaking a pot, he found that it not only had a false bottom, but that the inter-space was packed with segments of opium. The remaining pots, needless to say, were treated in the same way, and a rich haul was made. An illustration of this method, also, is given. Considering there was no seam, the workmanship of these pots was uncommonly clever.

Space packed with opium.

Section

There are doubtless hundreds of other methods as yet undiscovered by which smugglers get[23] their goods through safely. There is the heavy wooden bedstead, whose every leg is hollowed out to receive stuff, whose frame is but a shell to receive morphia phials. It is likely that the Chinaman who walks in front of you wearing a pith hat has cut-out spaces under the padded cover, in the pith, which are occupied by segments of opium; there is the Holy Bible that comes by post, with a square cut in the pages, containing opium or some other drug. The ways in which concealment is practised are legion. The wonder is that so many of these tricks are discovered!

But there are a number of cases in which the methods come to light only after the coup has been completed. A European, Hobson by name, ostensibly a coffee planter, whose plantation was on the frontier which separates an opium-producing country from British India, took to smuggling opium down to city smugglers, and in time accumulated great wealth. His methods were simple, but on one occasion a consignment he had sent down in charge of an assistant of his very nearly fell into the hands of the authorities, and he became more cautious. On one occasion after this, he ordered a consignment of fifty one-pound tins of tea from an oilmanstore merchant in the city, and on its arrival, took delivery. Next day, the same package was returned by rail to the address of the grocer. On arrival of the package in the city, a European, purporting to be an assistant of the grocer firm, called at the railway booking office, and producing the railway receipt, took[24] delivery of the case; the grocer being duly paid, never knew that the package had ever been returned to his address. The explanation is that Mr. Hobson had emptied the tea tins when he got them, refilled them with opium, and sent them back; but the railway receipt was sent to his assistant who, on arrival of the package, took delivery of it, and handed it over to the local smuggler in exchange for hard cash!

How this same Mr. Hobson once played a trick on a prominent detective will bear relating, even as inadequately as I am able to do it. Hobson was once travelling down to the city by train, when our sleuth, who happened to be on tour, entered the same compartment at a small wayside station. Having already seen Mr. Hobson’s descriptive roll, he had no difficulty in identifying him as the smuggler whom he had often dreamt about catching; and having the strongest reason to believe that H could not possibly know who he was, introduced himself as Mr. Jackson, travelling for a firm of leather merchants. The two got into conversation, and our sleuth, being an adept in the art of worming out details of other people’s affairs, soon got Hobson to open his heart to him. Facts and figures were eagerly noted whenever Hobson was not observant of it, and our sleuth was very pleased indeed with himself. Next morning, however, as he parted from his late companion at the city railway station, Hobson said, “Good-bye, Mr. ——” addressing him by his real name, “I am very pleased indeed to have[25] made your acquaintance. Here,” producing it from his pocket book, “is your latest photograph! Let me advise you to represent anything but leather another time. You don’t know a thing about it.” And then, as an afterthought, “Better tear up those notes you took. I’ve told you nothing that isn’t a damned lie!”

An Indian smuggler once took a rise out of a certain high police official, whom I shall call Duncan, and thereby made a mortal enemy for life. F. was the chief smuggler in this city, and his transactions in illicit drugs ran into lakhs of rupees. It was most desirable that this prince of smugglers should be brought to book. He was also by way of being a desperate character; for although it could not be proved, it was morally certain that more than one of the mysterious murders that had taken place in recent years had been committed or instigated by him. One day Duncan got information that F. had a large quantity of drugs, arms, and ammunition in his house, and that if search were made at once, F. would, to a certainty, be caught red-handed. This was luck indeed, and Duncan decided to make the search personally. Collecting a party of constables, he set out at once, but meeting the Black Maria (prison van) on its way back to the prison from the Courts, a brilliant idea came to him, and halting this grim conveyance, he and his party entered it, giving instructions to the driver to stop opposite F.’s house. Arriving there, some of the party soon[26] surrounded the house, while Duncan and the rest of them entered the place. F. was in his “Office,” to all appearances deeply immersed in piece-goods transactions.

“F.,” said Duncan, “I am going to search your house on information received. I believe you have contraband drugs, arms, and ammunition concealed somewhere on these premises, and I mean to find them. If you wish to search me and my party before we begin, do so at once.”

“I am a humble, law-abiding merchant, Sahib, and have no concern with drugs and firearms. You are quite at liberty to search anywhere you please.”

The search began. Duncan, although by no means a young man, worked with the rest. The place was ransacked from cellar to attic, but not a trace of what was sought was to be found. Duncan, covered from head to foot in grime and cob-web, at last reluctantly decided to give it up, and slowly descended the stairs to the lower room, where he was struck speechless with indignation. There was a table covered with the whitest of linen cloths, and groaning under an assortment of fruit and sweetmeats, crowned by a bottle of Pommery and Greno; while F., with a snowy towel over his arm, and a silver bowl of water in his hands, greeted Duncan with an invitation to wash and partake of refreshment “as your honour looks tired and dusty.”

“Damn you! I shall have you yet,” said the infuriated Duncan when he found his tongue; and[27] strode out of the house with rage and hatred in his heart!

It was discovered later that F., in a mischievous mood, had himself forwarded the information on which Duncan acted!

Bloody encounters with smugglers are rare, but they do happen sometimes, and as it is always on the cards that active opposition may be encountered when a party sets off to intercept a smuggler on his way to “market,” the work of an exciseman is not entirely free from danger. Very often when a smuggler goes on a journey, he travels armed with sword or spear; sometimes with a musket; sometimes even with a modern revolver or shot-gun. He is prepared to use these, and unless the intercepting party gets the “drop” on him, he will put up a good fight. Unfortunately, the officer, as a rule, though acquainted to some extent with the law governing the right of private defence of public servants acting in an official capacity, does not take full advantage of it; he has not been bred to kill; and it is probable that there is a lurking fear in him that the magistrate, who will hold the enquiry, will not see quite eye to eye with him, and that he may, perhaps, be convicted of a rash and negligent act, or grievous hurt, if he merely wounds his man, or even, perhaps, of culpable homicide. To some extent he probably is justified in so thinking. Not long ago, an officer fired[29] off his pistol in a melee following on a seizure, and wounded one of his assailants in the arm. A complaint was made, and the unfortunate young officer was convicted of grievous hurt, and sentenced to three months rigorous imprisonment and a fine. It is true he was afterwards retried and acquitted, but he was in no way compensated for the agony of mind he suffered, or for the degradation he had undergone in being tried as an ordinary criminal. This is chiefly to show that there is justification for an officer thinking twice or oftener before he proceeds to take risks. But the general run of magistrates are broad-minded men; men who combine with a sound knowledge of law, worldly wisdom, and a knowledge of the special conditions, and it is extremely rare for a conscientious officer to be “let down.” I shall now tell a story based on fact.

Information was brought to the inspector of ... that a certain well-known smuggler was on his way to ... and that he had a large quantity of illicit opium with him. Report had it that he was armed, and, accordingly, the inspector, providing himself with a revolver of small calibre—really nothing more than a toy—and his peon, with a shot-gun loaded with slugs in both barrels, set off with a small party to a certain pass in the hills near by, through which the smuggler would have to pass. In due time the smuggler, with a load on his shoulders, and a Tower musket in his hand, came along.

“Halt,” called the inspector, jumping from his place of concealment, and covering the smuggler with his toy revolver.

The only reply was a flash and bang from the smuggler’s musket, and for a moment, the air was thick with smoke and nasty whining sounds, as missiles of all kinds flew past the inspector’s head.

“Now I will shoot you,” said the inspector, and he fired a shot over the smuggler. The smuggler poured some powder down his musket barrel.

“Put down that gun!” ordered the inspector, and he fired another shot over the smuggler’s head. Now a piece of wadding clanged down under the smuggler’s ramrod.

“I shall certainly shoot you now,” threatened the inspector, and another tiny bullet whistled harmlessly past the smuggler. This time a handful of slugs went rattling down the long barrel.

“Can my master be bewitched?” thought the peon, who had the loaded shot-gun in his hands. “It must be so; but matters are getting too serious for further argument,” and levelling the gun at the smuggler he fired off both barrels at once, almost cutting the fellow in halves. A large quantity of opium was found in the smuggler’s bundle and the judicial officer who held the inquiry, a man who had risen from the bottom of the ladder, and whose experience was wide, while admiring the inspector’s humanity, considered that he had no right to expose himself and his party in the way[31] he did. He wanted it to be widely known that smugglers who went armed with the idea of terrorising the executive did so at the risk of being shot at sight, and he undertook to see that officers who did this did not suffer. The peon was handsomely rewarded and promoted for his presence of mind and opportune action.

Here is another story.

I had received information that a certain smuggler of repute expected a big consignment of opium, and that it would reach his house sometime during the night and be concealed there. It was about nine o’clock in the evening when I set out, clad in an old grey suit, cap, and muffler, for the smuggler’s house, intending to conceal myself somewhere near, and watch proceedings. As I entered the quarter where the smuggler lived, I was accosted by two beat constables who suggested that I was a member of the crew of one of the tramp steamers then lying in the harbour. After apparently satisfying them of my identity, I continued on my way, and was soon ensconced under a large tree, with the smuggler’s house and compound in full view. I had not been there an hour, when I heard the sound of approaching footsteps, and looking round, was not a little annoyed to find the beat constables again on my track. They had spotted me in the gloom of the tree, and being suspicious, had come to see who I was. To me it seemed that there was nothing to be gained after this by continuing the watch, and so, roundly abusing the two inquisitive myrmidons of the law, I went home.[32] I was later to regret my unkindness to my two preservers, for that, indeed, they proved to be. Next morning I was called upon by one of my spies, who handed me a wicked looking dagger with a blade at least five inches long.

“What might this be?” I asked.

“Sahib,” he replied, “if it had not been for the two policemen that disturbed your watch last night, that dagger would have taken your life. While you watched, there was one who watched you with this dagger. When the two policemen came along, he dropped the weapon and made off.”

No name was given, and it would have done no good to have taken proceedings against my would-be assailant, even if I had known his name. Such things are all in the day’s work. But I had the satisfaction the same day of going down to the smuggler’s house and unearthing over a maund of his opium. It is true that he got off at the trial on a technical point, but he lost a great deal of money, actually and potentially, and I felt I had called quits to the person who was the instigator of my attempted murder.

Taken all round, I think it must be admitted that the smuggler is a sportsman, in the sense that he plays a hazardous game at great personal risk, at the risk of his fortune, and against great odds. It is true that he takes all the care he can to minimize risks, but he can never hope entirely to eliminate the element of danger; and if his game be divested of all its peccancy, and most of its immorality, we discover in it the essentials of what goes to make horse-racing so popular a “sport” all over the civilized world. What is it that attracts millions to a race-course? Money! The desire to get money coupled with the excitement of the game. Out of every thousand persons who go to a race-meeting, nine hundred and ninety-nine go to gain money under feverishly exciting conditions, and one to see the horses run. Spanish bull-fighting however it may please the Spaniard, can never be otherwise than disgusting to an Englishman. But however shocked an Englishman might be at the ruin the smuggler causes to thousands of his fellow-men, he can never feel for the smuggler the contempt which he feels for the gaudy and[34] bespangled Toreador. He recognizes that the smuggler is playing a dangerous game, sustained by the arts of a subtle intellect, and that he also possesses the qualities which go to make a good fighter.

It may be that the smuggler has little notion of the havoc he spreads. It may be that he argues thus: “There is a demand for drugs, and people will be supplied by some means or other. They are willing to pay almost any price for the drugs they want; they are grown up people and well able to judge for themselves; why should I not make a fortune by supplying them with their wants at my own price?” This is a form of reasoning which contains no fallacy for a man unacquainted with the principles of ethics, and it is certain that the smuggler has not burdened his mind with such learning, admirable as it may be.

His offence against the revenue laws provides the smuggler with a never-ending source of pure delight. Every fresh triumph in this direction he looks upon as another feather in his already innumerably be-feathered cap.

But there can be no question about the dreadful misery for which the smuggler is directly responsible, and in succeeding chapters I shall endeavour to give as realistic a picture as I can of the awful results of this damnable traffic in drugs.

It may be taken for granted that most people are in some degree acquainted with the use of opium, having had it at some time or other administered to them as a medicine. Dover’s powder, so useful a remedy for a cold, contains opium; Laudanum is a preparation of it which is familiar to everybody; and there are scores of other remedies and proprietary preparations which contain opium to a greater or less extent. But useful as opium may be, it must be used with discretion, and must not be allowed to change its character of a faithful servant for that of a master. It can become an exacting and dominating master, and the habit once formed is well nigh ineradicable.

For the information of those who have not seen the pure drug, I may mention that opium is a dark brown, putty-like substance with an agreeable, sweetish, odour. It is the dried resin obtained by incising the unripe[36] capsules of a certain variety of poppy, and is prepared in large, well-equipped factories, from which it is issued in cakes and balls weighing eighty tolas.[2]

The opium industry is a Government monopoly. The poppy crops are grown under Government supervision, and the factories where it is prepared belong to Government and are staffed by Government servants. The prepared product is sold from Government opium shops from which consumers who are so privileged can get their requirements at a certain fixed price.[3] But as is the case with all monopolized commodities, opium may assume a money value far in excess of its intrinsic worth and be sold for its weight in silver. In fixing the price of opium, Government is confronted with a choice between two courses: either to sell opium cheap, and so extinguish the smuggler; or to prohibit it entirely and thereby convert India into a happy hunting ground for the avaricious and rapacious fortune hunter. It takes a middle course, therefore, and sells opium at such a rate that facilities for obtaining it are reasonable, without, on the one hand, rendering it cheap and easily obtainable, or, on the other, making it prohibitive. The policy pursued is one of eventual suppression; the discouragement of recruits to the opium habit being the[37] means employed as best adapted to bring about its realization.

The opium habit was an established thing in India centuries before the British first set foot in the country, and it is surmised that it was the Arab conquerors, who invaded India in the 11th century who first introduced it. The cultivation of the poppy, and the preparation of opium, were live industries in India in the 16th century, as Portuguese chroniclers tell us, and when the British East India Company took over the administration of Bengal after Clive’s victory at Plassey in 1757, all that they found themselves able to do was to adopt a policy of regulation leading to ultimate suppression. This policy has been followed ever since.

It is a fundamental weakness of human nature that we desire most that which it is most difficult to obtain. It is a perpetuation of the genesiac myth of the forbidden fruit; and no matter how optimistic some may be that the opium habit will eventually be stamped out, it is to be feared that this cannot come about until human nature ceases to be what it always has been. This contention applies with special cogency to the opium habit whose insistence in our midst is not only owing to the fact that it satisfies the sensuousness and voluptuousness which forms a part of every man’s nature, but that it establishes a dominance over its victims which requires almost super-human power of will to overthrow. In a letter to his friend and medical attendant Mr. Gilman, Coleridge, who was for[38] twenty-five years a victim to the opium habit, writes about the giving up of it as a “trivial task” and as requiring no more than seven days to accomplish; yet elsewhere he describes it pathetically, and sometimes with almost frantic pathos, as the scourge, the curse, the one almighty blight which had desolated his life. De Quincey very justly calls this a “very shocking contradiction,” and asks, “Is, indeed, Leviathan so tamed?”

It has been more than once suggested that the dissemination of a healthy propaganda would be the best means of deterring recruits to the opium habit, and that reliance upon the efforts of a strong preventive staff can result only in a diminution of the vice, and not its extinction. On some, such propaganda might have the desired effect; but with others, it may have just that effect which we seek to avoid. There is always a desire to experience new and strange sensations; there are always some who want an unfailing panacea for pain of body or mind; there are always some who long for oblivion. All these things are to be got from opium—the sovereign panacea for pain, grief, “for all human woes”; a weaver of dreams and ecstasies! And so, with the personal equation always solving itself, the problem remains to all intents and purposes unsolvable.

Let us see what the effects of opium are. A writer on the subject says, “A small dose not unfrequently acts as a stimulant: there is a feeling of vigour, a[39] capability of severe exertion, and an endurance of labour without fatigue. A large dose often exerts a calming influence with a dreamy state in which images and ideas pass rapidly before the mind without fatigue, and often in disorder, and without apparent sequence. Time seems to be shortened as one state of consciousness quickly succeeds another, and there is a pleasant feeling of grateful rest. This is succeeded by sleep which, according to the strength of the dose, and the idiosyncrasy of the person, may be light and dreamy, or like normal profound sleep, or deep and heavy, passing into stupor or coma. From this a person may awaken with a feeling of depression, or langour, or wretchedness, often associated with sickness, headache, or vomiting.” I have verified these statements by questioning numerous consumers of opium, and, in substance, their descriptions tallied exactly with that I have quoted.

How the opium habit is first contracted is a matter which deserves investigation, but it would seem that the most fertile cause is its injudicious administration in its character of an anodyne. De Quincey, in his “Confessions of an English Opium-Eater” tells us that he first took opium for a severe toothache. The poet Coleridge, who, like De Quincey, was a confirmed opium-eater, “began in rheumatic pains”; and if a census of consumers was taken, it would not be surprising to find that eighty per cent. of them were first introduced to this “dread agent of[40] unimaginable pleasure and pain” by its being given them for a stomachache, toothache, or some such wrecker of the peace of their mind. The other twenty per cent. are the victims of curiosity. The Burman is said to get the taste for opium when he is drugged with it while young, when he is, according to Burmese custom, tattoed from the waist to above his knees.

Nobody needs to be told that a habit is formed by the frequent repetition of acts or indulgences, and that some habits are more difficult to break ourselves of than others. The opium habit falls in this category. It is formed, of course, in the same way as other habits, but there are peculiarities connected with it on which those who are ready to condemn opium-eaters as degenerates might well ponder. The physiological effects of opium are such, that the wearing off of the effects of a dose are attended with the keenest mental and physical distress. No one who has not been an opium-eater can describe these adequately. The need, therefore, for a corrective of this condition becomes what seems an urgent necessity, and the only immediate corrective is “a hair from the dog.” A succession of these “hairs”—and a not very long succession—forms the habit. Unlike other habits, it is a habit that cannot be cured without immense strength of will, and a readiness to undergo great suffering: pains in the body, diarrhœa, and a general upset of the mental equilibrium. We see, therefore, that the cause of the[41] habit lies here: the need for opium to alleviate the pangs caused by opium.

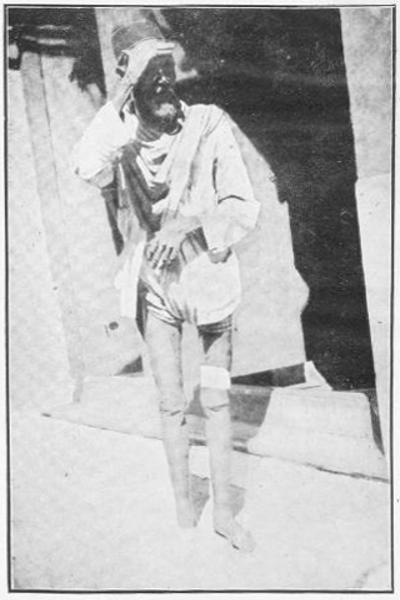

An Excessive Opium Smoker

Amongst unromantically inclined people of the type who form the bulk of consumers—cultivators, coolies, artisans of all kinds, humble folk whose creed is “pice and rice”—it would be difficult (and ludicrous) to suppose that their object in taking opium is to go in their dreams to:

Possibly, they do have pleasant dreams; but the exertion and hard exercise they must undergo to earn their daily bread is known to counteract the sedative effects of opium; and as they take small quantities only, its effect is to stimulate them rather than to make them dreamy and sensuous; and I contend that, primâ facie, it is not to evoke sensuous imaginings that these people take opium. They take it because they cannot get away from it, once the pain to ease which it was given has passed. What strength of will do we expect to find in an unlettered cooly?

Without any apology I reproduce here some verses which appeared in 1894, about the time when the Royal Opium Commission came to India:

THE OPIUM-EATER’S SOLILOQUY.

There are two modes of taking opium. It is either eaten in its crude form, or it is clarified with water and smoked in a pipe of peculiar construction.

It is generally conceded that opium smoking is less injurious than opium eating, bulk for bulk, of the amount consumed, and that the intemperate or immoderate opium smoker is less liable to the toxic effects of opium than the man who eats it raw. Why this is will be clear when it is explained that as a result of the process of preparation for smoking it, which consists in boiling opium with water, filtering several times, and boiling it down again to a treacly consistency, a considerable portion of the narcotine, caoutchouc, resin, and other deleterious elements are removed, and this prolonged boiling and evaporation have the effect of lessening the amount of alkaloids in the finished product. The only alkaloids likely to remain in the prepared opium, and capable of producing marked physiological effects, are morphia, codeia, and narceia. Morphia in its unmixed state can be sublimed; but codeia and narceia are said not to give a sublimate. But even if not sublimed in the process, morphia would, in the opinion of Mr. Hugh M’Callum (Government[45] Analyst at Hong Kong), be deposited in the bowl of the pipe before the smoke reached the mouth of the smoker. The bitter taste of morphia is not noticeable when smoking opium, and it is therefore possible that the pleasure derived from smoking opium is due to some product formed during combustion. This supposition is rendered probable by the fact that the opium most prized by smokers is not that containing the most morphia.

But what constitutes moderation or the reverse? The answer is idiosyncrasy, or the degree of toleration. This is a factor which is lost sight of by most of those who declaim against the occasional glass or pipe. They wish to push temperance to the point of total abstinence, and condemn the man who takes a peg of whisky without evil results, with the man who becomes maudlin after taking a single glass of white wine, for it is only by outward appearances they are able to judge. But leaving them to rage in their ignorance, we must recognise the fact that opium is one of those drugs the effects of which depend largely upon personal idiosyncrasy and toleration. Dr. Chapman, in his Elements of Therapeutics, gives two instances of remarkable cases of toleration of opium. In one, a wineglassful of laudanum was taken by a patient several times in the twenty-four hours; and in another, a case of cancer, the quantity of laudanum was gradually increased to three pints daily, a considerable quantity of crude opium being also taken in the same period!

The usual dose, as a medicine, is from one to three grains of opium, but a consumer can take from ten to twenty, while I have met many able to take from sixty to eighty grains. The degree of tolerance is increased by usage and habit, and the tendency is to increase the dose with habituation. With smokers, it is not uncommon to find Chinamen, the heaviest consumers of opium in the world, who can dispose of three tolas[5] of opium in the day; but they smoke it, and so can stand far more of it than if they ate it in the crude state.

The reader who has troubled to come so far with me will not unreasonably be curious to know how opium is smoked; so, if he will accompany me farther, I will take him into a den and satisfy his curiosity. It is a Chinese den. From the street it has nothing to proclaim its character; it is like any other entrance in the street. Ah! Here comes a smoker. Observe his deathly pallor, his appearance of emaciation, his dazed expression. He must be a heavy smoker, soaked in the vice. Let us go in with him! We enter. For a moment the dimness of the room flanked on three sides with raised wooden platforms waist-high, and covered with mats, is accentuated by our sudden entrance from the sunlit street. We become aware of a peculiar odour in the atmosphere of the room, not unpleasant, but peculiar. It is like nothing that we have ever sniffed before. It is the odour of smoked[47] opium. When our eyes, having got used to the light, or rather darkness, of the room, we look round and see on the platforms, sleeping forms sprawled round trays containing their smoking utensils. Let us examine these: First there is the pipe. It is made of a single joint of bamboo about a foot and a half long, hollow, and closed at one end, and about an inch in diameter. About a quarter of its length up from the closed end, there is an earthenware protuberance, not unlike a door-knob in appearance, firmly fixed into the stem; on its top, and in the centre, is a small orifice. This is the pipe-bowl.

Opium Smokers’ Appliances

Next we notice a lamp. This has a base of wood, and consists of a glass reservoir of oil, with a string wick leading from it through a small brass cap. Over this is a glass chimney.

Then we see the wire, like an ordinary fine knitting needle; and several horn phials, each containing prepared opium.

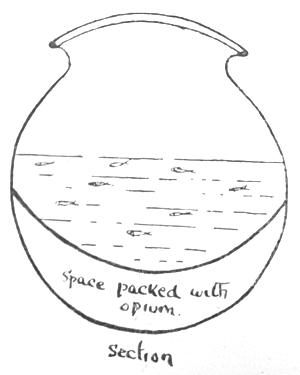

Preparing to Smoke Opium

(The opium on the end of the dipper being roasted over the lamp.)

But here is the new-comer whom we followed in. He has paid the den-keeper the small fee which makes him the temporary owner of a tray of smoking utensils, and with these he passes us, and getting on to the platform between two sleepers, he puts his tray down, and assumes a recumbent attitude beside it. Lying on his left side, with his head on a hard lacquered pillow, he draws the tray towards him and takes the pipe in his left hand. With the other hand he takes the piece of wire, and plunges one end of it into the horn phial[48] containing treacly prepared opium, withdrawing it immediately with a drop of the fluid adhering to the point. This he maintains on the point by rapidly twirling the instrument between two fingers, and carrying it over the flame of the lamp, he proceeds to roast the opium. This is a delicate operation, and requires practice. The needle is dipped into the phial again and again, and the opium adhering to the end roasted over the flame until an appreciable quantity of the drug has accumulated on the end of the wire. He rolls this accumulation, still on the end of the dipper, on the flattened top of the pipe bowl, until it has acquired the desired shape, and then thrusts the end into the orifice in the centre of the bowl, and twirling the wire sharply round, withdraws it, leaving the opium in the orifice. Now, taking the lower end of the pipe in his right hand, and the mouth end of the pipe in his left, he applies the open end to his lips and holding the bowl almost inverted over the top of the lamp begins to take long inhalations, the smoke escaping through his nostrils. The little plug of opium in the orifice crackles and burns in the heat of the flame, and we notice that the smoker now and then scrapes towards the orifice in the bowl, all the particles of opium which remain unburnt. He finally clears the orifice by thrusting the wire into it several times, and disconnects the bowl from the stem. We notice it contains an appreciable quantity of black, evil-smelling opium residue. This is the “dross,” carefully preserved[49] by smokers, and later on boiled with raw opium to which it is believed to add strength. We watch him smoke a few more pipes, and eventually the pipe falls from his nerveless hands, and he lies still. What are the dreams which flock through his mind? We do not know, but Bayard Taylor in his book India, China and Japan tells us of his personal experience of the effects of opium smoking. It was his first and last attempt, and his record is interesting. He says:—“To my surprise I found the taste of the drug as delicious as its smell is disagreeable. It leaves a sweet, rich, flavour, like the finest liquorice, upon the palate, and the gentle stimulus it conveys to the blood in the lungs fills the whole body with a sensation of warmth and strength. The fumes of the opium are no more irritating to the windpipe or bronchial tubes than common air, while they seem imbued with a richness of vitality far beyond our diluted oxygen.

“Beyond the feeling of warmth, vigour, and increased vitality, softened by a happy consciousness of repose, there was no effect until after finishing the sixth pipe. My spirits then became joyously excited with a constant disposition to laugh; brilliant colours floated before my eyes, but in a confused and cloudy way, sometimes converging into spots like the eyes in a peacock’s tail, but oftenest melting into and through each other, like the hues of changeable silk. Had the physical excitement been greater, they would have taken form and substance, but after smoking nine[50] pipes I desisted, through fear of subjecting myself to some unpleasant after-effects. Our Chinese host informed me that he was obliged to take twenty pipes in order to elevate his mind to the pitch of perfect happiness. I went home feeling rather giddy, and became so drowsy, with slight qualms at the stomach, that I went to bed at an early hour—after a deep and refreshing sleep, I arose at sunrise, feeling stronger and brighter than I had done for weeks past.”

Chinaman Smoking Opium

It is now proper that we should ask the question “Is opium the very dreadful thing it is made out to be?” My answer is, yes and no. Anything immoderately indulged in is bad for one. Over-eating, excess in smoking and drinking, are all bad. There is such a thing as too much of even a good thing. I am prepared to admit that excess in opium is worse than most things; but as a choice between opium and drink, I consider drunkenness to be the greater evil. It may be that it is more common, and therefore responsible for more distress in the world than opium; but opium does not, and can never, degrade as drink does, and a man does not make a beast of himself with opium. It does not make a nuisance of a man; it does not lead to violence and to murder as drink does. I do not ask reformers to subscribe to this view. I express it as my own opinion, founded as it is upon close acquaintance with numerous opium consumers, and many drunkards.

What is it that reformers have to urge against opium? They will not admit that opium in moderation does no great harm; they will not agree that the degree[52] of toleration varies in people. Let us take their contentions seriatim, and see how they will stand against logical and informed discussion:

They say: (1) That opium in any degree induces physical degeneration.

I say, I have met men of wretched physique who are opium consumers, and men of wretched physique who are not opium consumers. Also, I have met giants in strength who are not opium consumers, and giants in strength who are confirmed opium consumers. I will also say this, that among the hard-working class of Indians and Burmans, such as coolies and porters, the proportion of consumers to non-consumers is about equal, but I have been able to observe no inferiority in capacity in the consumers, and very often have found them superior. Those who wish to learn what the powers of bodily endurance of an opium consumer may be are recommended to read that very readable book “An Australian in China.”

(2) That the consumer is mentally inferior to his non-consuming brother.

This I qualify. It depends on the degree of indulgence, and unless this is considered, it is not possible to argue. It is a proved fact that the effect of opium is to quicken the perceptions, and stimulate the imagination. Too often this is taken to be evanescent; and it is assumed that the intellect weakens, and that, eventually, it is enfeebled beyond chance of recovery. But if opium were not taken; in such a case, would not[53] advancing years bring about a like condition? Charles Lamb, who drank more than was good for him, and Coleridge, who was an opium-eater, complained that the effect of their particular “poisons” was to deprive them of their capacity for singing when they awoke in the morning! Lamb complained of this when he was forty-five, and Coleridge at the age of sixty-three. Does anyone imagine they would have been able to “revive the vivacities of thirty-five” if they had been always temperate men?

There is no doubt that, taken in large quantities, opium induces a sluggishness, a lethargy, a stupor; but does not an unusually heavy meal induce a torpor which is incompatible with any sort of intellectual labour? I hold only with moderation.

(3) That indulgence in opium weakens the character and morals.

This applies with equal force to immoderation in most things. It does not hold good of opium taken in moderation. To affirm this is a clear indication of ignorance of the subject. Why, in the name of all that is extraordinary, should a moderate dose of opium make a man a thief, or a criminal, or a moral imbecile? Indians and Burmans, whose religion forbids all manner of intoxicants, condemn their opium-eating brothers to a sort of social ostracism, and when asked for a reason, say, “It is against our religious tenets; and it is very bad in every way.” Such uninformed statements are excusable in the unenlightened, but what of those[54] who ought to know, and who pride themselves upon their education and reasoning faculties? They are as clamorous against opium and other things in a more censurable ignorance of facts. Some who will not clear their minds of cant, declaim against a glass of wine with all the fervour and denunciation of fanatics, without rhyme, reason, or apprehension of what they are talking about. In their more fluent and exuberant way, when pressed for a reason, they tell us in effect that indulgence in opium is “Against our religious tenets, and it is very bad in every way.” It is time reformers recognised that opium is not such a dreadful thing after all, and confined their attention, and devoted some of their ample leisure, to winning back those who have gone over the limit of moderation, instead of anathematizing them.

It is a pity that reformers do not pursue their propaganda along reasonable and obvious lines, because they would have more supporters and helpers if they did. To publish fulminatory pamphlets against the opium evil, without having any experience of it at first hand beyond an occasional hurried visit to an opium den, is worse than futile; and they cannot hope to convince those who are really in a position, and qualified to help them in their efforts. This is due to a profound ignorance of facts, and a lot of people in India are responsible for the dissemination of a lot of ill-digested nonsense. An enthusiast visits an opium den and finds half a dozen Chinamen sprawled around,[55] with as many opium pipes. He does not know that these men have come in from a ten-hour day’s work. He throws up his hands in pious consternation, and writes home about the dreadful place he has visited, and of the horrors of intoxication he witnessed there. The vividness of his description is modified only by the amount of rhetoric at his command, and no one who has come into contact with this sort of person will deny that he always has a vast store!

I once met a missionary, and in the course of conversation, we happened upon the opium evil. He was eloquent, his views on the subject were decided. In fact he was so decided in his views that I found it impossible to convince him that what he described as the effects of opium were really those symptomatic of an overdose of bhang. And yet, I have little doubt that this person must have written home lurid accounts of the opium evil, and the ruin and havoc it was causing. What reformers ought to do is to cease memorializing Government to totally prohibit the traffic, and try to help them more by taking an active part in checking immoderation. Moderate indulgence in opium is less harmful in every way than the habit of passing public resolutions and submitting memorials.

By the foregoing, I do not wish it to be surmised that I hold a brief for the opium habit, or that I consider it a desirable thing. To be a slave in any degree to anything is bad; the tobacco habit is bad; the over-eating habit is bad. But opium comes in for too much[56] of the attention of religious propagandists, and the Government is taxed with the charge of reaping revenue at the expense of the bodies and souls of the people. This is a view it is the duty of anyone who knows the subject intimately to correct. The Royal Commission on Opium in India, which sat under the chairmanship of Lord Brassey, some thirty years ago, collected a mass of evidence for and against opium which is unrivalled in its extent and value. The conclusion come to by a majority of the Commissioners was that opium in moderation did no great harm; and to ensure moderation, they recommended a policy of close control. In deference to popular opinion, and the religious scruples of the bulk of Indians, they thought it desirable that the opium habit should eventually be suppressed, and trusted that close control would, by attrition, bring about this result.

Morphia, which is the active principle of opium, is interesting in its being the first “alkaloid” to be discovered. Its basic nature was first noticed by Serturner in 1816.

As a medicine, principally as an anodyne, morphia is to pharmacy what chloroform is to surgery, and, as a “boon and blessing” to man in that character, it is second to none. But like all good things in this world, it has become the object of the grossest abuse at the hand of man; and its devotees, in an euphonic sense, number hundreds of thousands.

Morphia is a narcotic; that is, it “has the power to produce lethargy or stupor which may pass into a state of profound coma or unconsciousness, along with complete paralysis, terminating in death.” The degree of insensibility depends upon the strength of the dose; one-sixth of a grain for an adult man, and one-tenth of a grain for an adult woman, being the largest safe dose given hypodermically. Two or three grains given by the stomach is dangerous. But, as with opium, the dose varies with idiosyncrasy, and some can tolerate larger doses than others. With habituation, some[58] persons can take with impunity an amount of morphia which would prove fatal to five or six healthy, full-grown men. To have its full effect as an hypnotic or anodyne—and its power as the one depends upon its potency as the other—morphia must be given hypodermically.

The possession of morphia by people other than medical men and chemists is prohibited by law; and the rules governing its sale by chemists are rigid and exact. They must account for every grain sold, and all entries in their sales registers must be supported by prescriptions signed by qualified medical men. Yet morphia injecting is more prevalent in cities than the public is aware of; and it does not require a very penetrating mind to discover that the morphia used by its unfortunate victims comes from illicit sources—from the smuggler. There are, of course, unscrupulous physicians, dentists, and quacks, who pander to the cravings of some of their “patients” by administering regular injections; but we are dealing here with the type of persons who do not call in doctors, accommodating or otherwise. The ones I write about are catered for by an organization which, in spite of the greatest efforts, has been found to be unrepressible.

Group of Morphia-Injectors

How do these people get their supplies? Let us go into a morphia den unofficially, and take a glance at it in all its sordidity. We draw aside a filthy sheet of cloth which does service as a curtain, and enter a room about twenty feet square. It is dim almost to darkness;[59] but at the farther end, opposite the entrance door, we notice a wooden partition which has a locked door in it, and near it a hole not unlike the window of a box or ticket office. Through this hole a light is seen, so we presume that there is someone behind the locked door in the partitioned-off portion of the room. Looking round us, we see a row of human figures, clad in the foulest rags, lying along the two sides of the room, near the walls. Some are apparently asleep; actually, they are drugged, overcome by the last injection of morphia. Others are about to make themselves comfortable for a sleep, having just had an injection; while some, too poor to afford the cost of another dose, are groaning and whimpering with the combined agonies of some painful disease, and the wearing off of the effects of the last injection. These accost everybody that enters the den for the price of “just one little injection.” They appeal to those who have endured the same pangs with which these unfortunates are wracked. The appeal is to a real, live sympathy; and if it can be spared, the required money is handed over.

One of these beings has not appealed in vain to a fellow votary who has just entered the den in company with two companions, and the four make their way to the hole in the partition, and in exchange for the coppers handed in, a skinny hand passes out four little paper packets, each one containing a dose of morphia powder. Let us peep through the hole, and look at the owner of[60] the skinny hand before following the four to the place to which they have retired. It is a Chinaman, characteristically lean, sitting at a rough table on which is a cigar box filled with paper packets similar to those we saw being handed to the late purchasers. The red and green ones contain morphia, the white cocaine (for he caters for both classes, the injecters of morphia, and eaters of cocaine). Looking up at the hole, he sees us, and thinking we are either excise or police officers, he hastily gathers up his wares, and rushing to the sanitary arrangement in the corner of his cubicle, empties them into the receptacle, and pulling the chain, flushes away the incriminating evidences of his occupation. Being assured that they are well on their way to the sea through the sewer, he turns towards us with a “smile that is child-like and bland,” and explains that he has “got nothing—all gone—you can’t do nothing.” We explain that we had no intention of doing anything, and were merely curious. Recollecting that he had heard no call from his ever watchful colleague who stands by to give timely warning in the event of a raiding party coming in sight, he admits that he has been precipitate; but in no way disconcerted, he sends his colleague off to some place best known to themselves, for a fresh supply of packets.

We now return to the four men who provided themselves with morphia two or three minutes ago. We find them sitting in a ring round another fellow who we learn is the operator. He possesses a hypodermic[61] syringe. Let us take and examine it. It is not the sort of thing one would expect to find in a chemist’s show-case or a medical man’s pocket-case. This is a weird instrument; the barrel a length of glass tubing; the plunger a bit of knitting needle, whose plunging head consists of tightly wound rag, and whose other end is topped with a conglomerate of sealing wax and sewing thimble. Both joints are lumps of sealing wax, through the lower of which an inch and a half of hollow needle projects. Handing back this septic instrument to the operator, who, by the way, tells us that he gets a copper for every injection he gives, he proceeds to empty the contents of the packets into a small china egg-cup. Adding a modicum of water, and stirring the mixture until a clear solution is formed, he takes up some in the syringe, and one of the expectant waiters draws nearer him. A search is made by the operator for a clear spot on the body of the man, where a dirty needle has not already penetrated and caused a foul sore, and after some search such a spot is found, on the palm of the hand, and here the needle is introduced, and the contents of the syringe discharged, after which the man operated on limps away to his place, and lying down, is soon asleep. The next draws near, and having received his share of the dose with the same needle, unsterilized and unwashed, he in turn limps off; and so with the others.

Let us hope that the fell, loathesome, unnameable disease, from which one at any rate of the four was too[62] apparently suffering, has not been introduced into the blood of the others by that death-dealing needle! But it is a hope that we cannot think is justified; the means of propagation employed are too certain to admit of any hope!

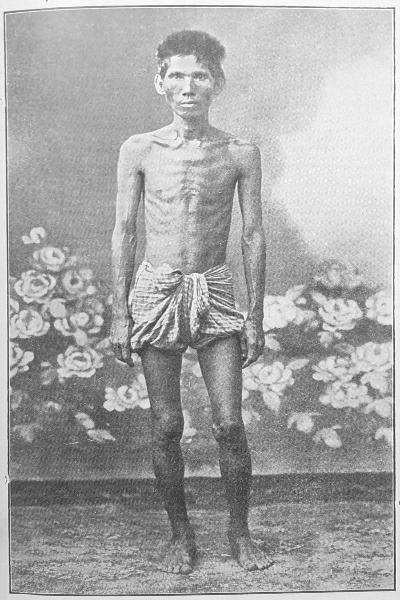

The foul and fetid atmosphere of the crowded room is almost overpowering, in spite of the strong tobacco we smoke in our well-lit pipes, but we will linger a little longer and take a glance at those who are lying around like so many logs. Look at this one of them. What an object lesson he is to impetuous youth! Thin to emaciation; his hair fallen off in tufts; his nose almost eaten away; his body covered with sores and ulcers. There is nothing to wonder at in this being taking morphia to ease his pain of mind and body. Since death will not come, let him have oblivion. It is better so.