There was no escape but death

from that fetid prison planet

and its crazed, sadistic overseer.

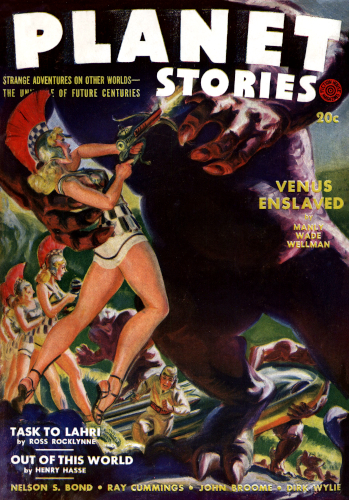

[Transcriber's Note: This etext was produced from

Planet Stories Summer 1942.

Extensive research did not uncover any evidence that

the U.S. copyright on this publication was renewed.]

When the Earth supply ship set down upon prison planet Number Seven last week, a curious state of affairs was found: the prisoners below mining the ore as usual, the overseer dead, and every indication of some stark drama having taken place. In the study of the overseer's house one man was found dead, apparently by his own hand, and beside him on the desk was a hastily scribbled document which is herewith published.

We hated Marnick.

Because he was an Earthman and because he laughed, we hated him. Awake and asleep, at our daily drudge of labor and in the throes of sluggish nightmare, with a fierce tenacity from the very depths of our souls—those of us who still had souls—we hated him. And there was not a man among us who had not sworn to kill him if given the chance, who did not dream of being the one. For we knew that some day it was going to happen.

But when? It seemed impossible. Daily that is what I thought as I trudged wearily to my place in B-Tunnel two miles below. We were forty men against him, Martians and Earthmen alike. Once there had been Venusians here, too, but they died too easily, and now Venusian criminals were sent elsewhere. Forty against Marnick, but still he was Law here on the tiny barren satellite of Jupiter—the seventh or eighth in orbit, I have long since forgotten which. The Tri-Planet Federation had appointed him overseer, then had immediately forgotten him and us. Out of our way, you criminal scum! Out of the sight and memory of men! Thus it was.

Yes, Marnick was law and lord and master of all he surveyed, and believe me he surveyed us well. He used to come down the central vertical shaft in his little case of special glassite, and hover there above us, watching; sometimes unbeknownst by us; and heaven help any worker who fell under his gaze, who he thought might be shirking. Marnick reserved a very special fate for shirkers, a certain torture, so I had heard.

Now all that I had heard came rushing back to flood my brain, as I stood tensely alert, listening to the raucous, inhuman laughter that surged down the central shaft to reach our ears. Again it came and yet again, rising to insane pitch.

I rested my short-handled hand-pick against the little heap of radite ore. I wiped my sweated brow with fingers that burned and tingled from contact with the radite. I peered covertly around at the many tunnels converging into the central place, and saw the other workers, Martians, and Earthmen, cowering under that sound of laughter. I wondered if I looked to them as they looked to me. I knew I was afraid. That was Marnick's laughter, I had heard it before. His special torture was going on again. Would I be next? So far I had luckily escaped.

I tried to straighten up into a semblance of courage, but again that shrieking laughter came drifting down to cower me. At the same time McGowan left his tunnel next to mine, and came strolling over to me. I was aghast. For any man to so much as leave his post, meant that he would receive the same punishment that some poor devil up there was now receiving. But McGowan always was a reckless one. Tall, brutish, dark and always scowling, a light of indomitable spirit shone perpetually out of his contrasting gray eyes. Those eyes were now hate-filled as he cocked his head and listened to that laughter.

"If only he wouldn't laugh," McGowan said in a voice so calm that it was doubly terrible. "If only he would go ahead with his torture, and watch it if he wished. But to laugh! And to let us know that he laughs! That is the crowning touch. Some day, Reed, I swear to you—"

"Yes, I know," I whispered fearfully. "Some day one of us is going to kill him. A favorite dream here."

"Not someone, Reed. Me! That is a privilege I reserve. And I shall not kill him. At least not in the usual way. I have a very special revenge planned for Mr. Marnick."

That was a story I had heard before, too; but now something in McGowan's voice caused me to look sharply up at him. And the hate that smouldered in those eyes was such as I cared not to look upon. I glanced quickly away, and then I heard a smooth familiar hum from the central shaft. I knew what it was. I swooped for my hand-pick and began to ply it industriously.

"Quick, McGowan, get back to your work!" I whispered. "Marnick's coming down again!" I'm sure McGowan knew that as well as I did, but he simply stood there, gazing almost expectantly at the place where the shaft led up through the cave roof. "You damn fool!" I whispered, but there was a tight little smile on McGowan's lips as he stood there.

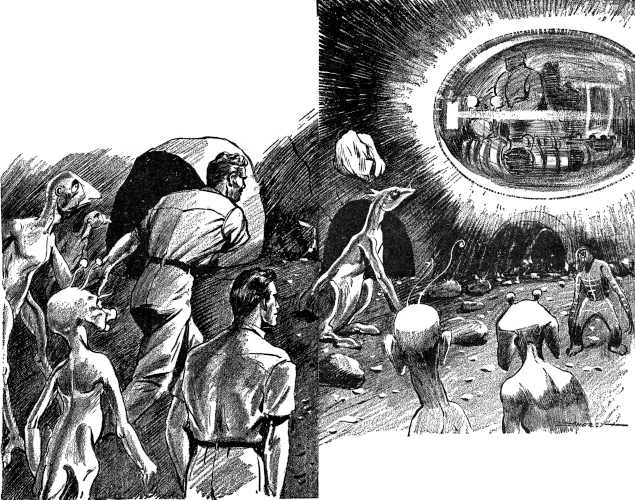

The hum continued. Even as I continued to hack at the hard-grained rock I shot a sidelong glance up at the shaft. Marnick's vehicle appeared suddenly there, seemingly suspended in the air. It was simply a glassite-enclosed, rounded cage, large enough to contain Marnick and the two lumbering, Jovian brutes he kept always with him. A pale violet halo hovered around the entire structure. It hung there just below the cave roof.

I could glimpse Marnick standing there erect, arms folded, peering haughtily down at us. Naturally a tall man, he always seemed taller and more forbidding in that posture. His hair was gray, but no grayer than his face; and against that grayness his eyes were dull black and quite expressionless, as if at one time he had seen some sight that had burned them out.

But now his arms unfolded and he leaned tensely forward. His thin colorless lips twitched as if in disbelief. A second later his rasping voice went bounding about the walls: "You! Earthman, over there! Get back to your work!"

He was speaking to McGowan and we all knew it. McGowan stood only a few feet from me, but I dared not even glance up at him now. I glimpsed him, however, bending down slowly, deliberately, and I saw his right hand seize a good-sized lump of radite ore from my pile. He straightened just as deliberately, turned to face Marnick and then said: "Go to hell!" With those words, McGowan drew back his hand and hurled the radite lump at Marnick's cage.

All of us in that moment paused to watch, and all of us were aghast at McGowan's futile bravado. We knew that not even an atom-blast, much less a lump of rock, could penetrate that mysterious force-barrier Marnick had erected around himself. That's what made the act so terrible, for McGowan knew it, too. And he wore a satisfied little smile as he did it.

Straight at the glittering machine McGowan hurled the heavy boulder.

The rock didn't come within a yard of Marnick's cage. It struck against the violet force-halo, bounded back and clattered to the floor. Marnick's lips split into what might have been a grin; he touched a button beside him and the cage dropped the rest of the way to the cave floor. Its door opened and the two Jovian brutes stepped quickly out. Grinning through thick, blubbery lips, with huge powerful hands reaching out, they strode purposefully toward McGowan.

McGowan made no defensive gesture. He stood there still smiling a little, as though hugely satisfied with what he had done. The Jovians seized him ungently, hurried him back to the cage and into it. The door closed and the cage slowly began to rise. The Jovians released his arms then, and McGowan acted with customary deliberateness as his right fist lashed up and crashed into Marnick's mouth. Marnick staggered back, his face a gushing well of red; but with a seeming flick of the wrist his paralyzer tube was in his hand, its pale beam spurting out. McGowan sank down in a huddled little heap, but even so, his very attitude as he lay there unconscious seemed one of satisfaction. The cage rose swiftly up and out of sight.

I didn't allow myself to think of the fate that would be McGowan's now. As we worked we listened again for the sound of Marnick's insane laughter. But it never came. He knew that we hated him, and he loved it. It was a sort of little game he played with us. He knew that we would be listening for his laughter now, so he chose not to let us hear it; to make us wonder. Psychologically it was much more terrible.

That Marnick was a devil.

Four days later McGowan came back to us.

Rumor among us had it that Marnick maintained special quarters up on the surface of this satellite, a stone house against the barren rock; and that in this house was a certain room into which Marnick thrust the men who displeased him. Beyond this even rumor failed to go, but we often hazarded guesses. The most prevalent guess was that Marnick released hordes of Callistan Gnishii into this room, then stood at a glass-paned door and shrieked with insane laughter at the antics of the unfortunate victims. The Gnishii are tiny little sharp-tipped devils, scarcely three inches in length. Hard-shelled, blazing red in color, they surely must be a spawn of hell; for they are quite harmless except when in the presence of human flesh, and then they seem to go wild.

We guessed that Marnick might be employing these Gnishii, because several of his victims who came back to us had hundreds of fresh scars covering their legs from ankles to knees. But these men seemed to prefer not to speak of what they had undergone, and the rest of us weren't too anxious to know.

So now, four days later, McGowan came back to us. He stumbled into our quarters along the murky tunnel just above the vein we were at present working. I rose up out of restless sleep and saw McGowan going along the tunnel to certain of the men, silently rousing them. Kueelo and V'Narik, both Martians, joined him; as well as Smith and Blakely and Wilkinson, Earthmen. These five, together with McGowan, had formed a special little cliche among themselves, and almost daily went off for a secret meeting somewhere during our sleep period. Innumerable times I had seen them do that, but I didn't much care, feeling that whatever they might be planning would be futile in the end.

Now I rolled over in my bunk, turned my face to the stone wall and tried to get back to sleep; I needed much sleep in preparation for the morrow, because lately the radite emanations had been fast sapping my strength. Then, to my amazement, I felt a light hand on my shoulder and I knew it was McGowan. I heard his voice in my ear, scarcely a whisper:

"Reed! You awake? Come on and go with us; we need you!"

They needed me! Wondering and doubting, I rose silently up and followed the six of them toward the dead end of the tunnel. Blakely carried an electric lantern, carefully shaded. A quarter of a mile further we came to the tunnel's end. There in the dim light I gazed around me at the worked-out rock. The radite vein here, I knew, had been exhausted years ago, even before I had come.

As I stood apart, watching, the six of them seized upon a protruding rock and pushed with a certain unison that could only have come with long practice. The rock rolled smoothly away and revealed a ragged little ravine leading up and into the tunnel wall. We entered, and they pulled the huge rock back into place. We began to climb. The ravine was scarcely shoulder-width. A few minutes later, however, it widened out into a large, natural cave!

Blakely placed the light in the center, and we sat in a circle around it. We could only see each other's faces dimly. The two Martians' were dark and leathery, with thick-lidded expressionless eyes. The three Earthmen appeared a little anxious as they glanced at McGowan. I knew what they were thinking, wondering; I was wondering myself.

As though reading our thoughts McGowan said: "Yes, it—it was pretty terrible." But by the look in his eyes alone, dim as it was, we knew that was a masterpiece of understatement. "But that's beside the point," he went on. "Whatever I went through up there, it was worth it. And it had to be done. For your information, Reed"—he turned his head to look at me—"we're going to escape from these tunnels. Then we're going to kill Marnick. When that's accomplished, we'll think about escaping from this planet."

"But—but how—" I stammered. "You know you can't possibly—"

McGowan gestured impatiently. "I know everything you're going to say. We've gone over it thoroughly. Let's see, you've been here only two years, isn't it, Reed? And the average life here is five; and I have already been here seven. Yes, I've clung on here longer than most men do, knowing that some day my chance would come; and now it is near. For the moment we will not think of escape. If only I can succeed in getting rid of that monster up there, and doing it in my own special way, all this will have been worth while. Do you agree?"

I most emphatically agreed, and said so.

McGowan arose and led me to the other side of the cave. There I saw a small, dark opening, perhaps four feet in diameter. A tunnel! A man-made tunnel leading steeply upward through solid rock!

"For about four years we've worked on this," McGowan said with a tinge of pride in his voice. "We've hacked our way inches at a time with whatever crude implements we could smuggle here. More than a mile of solid rock lies between us and the surface, and we've gone more than three-quarters of the way already."

"But why didn't you let me in on this!" I gasped, a sudden surge of hope welling up in my throat so that I could hardly speak. I could hardly even think! My brain was churning crazily. To get out of these tunnels, to even glimpse a star again against the black night sky, or breathe fresh air once more—those were hopes that many of us had abandoned, as we gradually became living automatons and the radite ore took its insidious toll of us.

McGowan looked at me steadily and answered my question: "Because we don't trust everyone. Marnick has certain methods up there of extracting information, and if ever—Well, anyway, you've been rather a baffling entity since you came here. You still are. Right now we don't know whether to trust you, but we have to because we need you."

"But you can trust me!" I exclaimed in an excess of anxiety.

"We need you," McGowan went on coldly, "because we understand you're something of an expert with directional beam finders. We suspected that Marnick might have a network of beams raying downward, to detect any such escape attempt as this. We had to make sure, and that's why I had to get to the surface, although it meant torture. And I did find out, never mind how. He has a battery of directional beams. They won't reach through rock very far, but we can't be too careful now that we're getting near the surface. So, Reed: do you think you could detect any such beams, before we break through into them?"

"Yes, I'm sure I could," I answered, perhaps a little too eagerly.

"Good. Then you're in with us to the finish." He turned to the others. "Wilkinson—I think it's your turn tonight? Reed here will go up with you. Incidentally, you might veer a few degrees to the right; as near as I could judge, we're coming a little too close to Marnick's quarters. And you, Reed, keep a sharp lookout for those beams."

I entered the dark little tunnel behind Wilkinson, and we began the climb. He carried the lantern. It was rather precarious. The tunnel, I judged, was on a forty-five-degree angle, but wisely they had leveled out little hand and foot holds, so that we could rest occasionally.

Three-quarters of a mile, McGowan had said. It seemed more like five, but I didn't mind at all. All my weariness and sleepiness had left me now; every time I scraped a knee or elbow against the rock it was a pleasure, now that a new hope was born in me. At last we reached the top, and I cautioned Wilkinson to remain still while I tried to determine if any of the magnetic finder beams were near us. First I stripped myself to the waist, then pressed my body against the rock wall in various spots. Wilkinson watched the process curiously.

"No," I told him at last. "I can't feel a thing yet. Probably we're still too far down."

"How come you can feel those beams when other men can't?" Wilkinson asked.

So I told him the story. "Years ago I worked in one of the electrical laboratories where these beams were being developed. One day I was accidentally locked in the testing room—a small chamber where the beams were projected upon metal plates to test their intensity. Luckily for me, the beams that day were of a very low intensity, or I wouldn't be here now. But the power kept increasing by slow degrees, until I could feel the vibration tearing through every fiber of my body. At last, and just in time, I managed to attract attention. I was violently ill for weeks. But after that, I seemed to be hyper-sensitive to such beams."

Wilkinson continued digging at the rock with a small metal implement. Bit by bit the rock came out, in powdery dust and tiny chunks. I noticed that his hands were scarred and roughened from day after day of this work.

"When we first began," he explained, "we made much faster progress. But now a man can't work more than two or three hours up here, for the air gets pretty stale. We take turns, of course, day after day. It's going to be pretty tough on you from now to the finish, because you'll have to be up here every day for a couple of hours. We're counting on you."

Yes, they were counting on me. Now for the first time I began to realize how much; and I began to doubt myself. I wasn't really sure that I could still detect those finder beams. It had been a long time since I had experienced it. Besides, the radite ore emanations had effected my body in that curious tingling way, just as it had every man here. So perhaps that would prevent—?

I only knew that if we ever blundered into one of those directional finder beams, which McGowan said were raying down, it would instantly set off an alarm in Marnick's quarters. I tried not to imagine what would happen after that. In a sort of panic I pressed my sweating body against the rocky wall, but all I could feel was the familiar radite-tingling crawling through my skin.

So we worked day after day until they lengthened into weeks. My daily labor at the radite vein was almost a pleasure now as I anticipated the few hours of work that would come later in our secret tunnel. Daily I accompanied a different one of our group. I wanted to take my own turn at the digging, but McGowan wouldn't stand for this, preferring that I direct all my attention toward the detector beams.

Weeks passed and still I detected no beams.

Kueelo, I found, was sullen and silent. The other Martian, V'Narik, talked to me only on a few occasions. "I have a curious presentiment," he told me once, "that I shall never escape from here. You others, perhaps, but not me. I am with you on this only because there is nothing better to do. But if I can only reach the surface, and glimpse the stars once again—especially the redness of Mars—this will have been worth while."

The Martians are a strange race. I never could understand them. I tried to cheer V'Narik, but he only shook his head solemnly.

From the others I gradually learned much that I had often wondered about, especially concerning Marnick. "There are various stories about him," McGowan told me once. "The one I'm inclined to believe is that Marnick incurred his hatred of men long ago, during the early years of the Mars mines. He was one of the earliest pioneers there. He brought his wife and child from Earth. He struck a rich iridium vein and worked it slowly, alone. Then certain Earth corporations stepped in, as you know. They wanted Marnick to sell but he would not. He defied them to the end, which was foolish. Well, one day Marnick came back to his mine to find his wife dead, rayed mercilessly by a heat-gun, and his young son missing, probably lost in the Martian wastes."

"You don't mean," I gasped, "that the Earth corporations would—"

"Would do a thing like that? They would hire it done. That's the way they worked in the early days, they always got what they wanted, in one way or another. Well, Marnick must have sworn a terrible vengeance then. He fought them and plagued them, for years he pirated the spaceways until the Tri-Planet Patrol was formed and became too strong for him."

I pondered this story. "So now," I mused, "he's come to this. As overseer of this penal planet, he must be—"

"He is assuredly insane," McGowan finished for me. "But he is still vengeful. He was never certain whether they were Martians or Earthmen who killed his loved ones—those men hired by the Earth corporation. But ever since, I believe, Marnick has had a brooding hate for both races, especially the criminal element. That's why he's devised his tortures here. That's why he laughs as he indulges in his wholesale revenge. A sort of revenge by proxy, as it were."

I was aghast as I glanced at McGowan, wondering just how close to the truth about Marnick he had come. McGowan's eyes were steel hard again with hate as he went on:

"And that's why, Reed, we must put an end to Marnick's mad reign here. He was done a terrible injustice in the past, yes; but he's had his revenge many times over, on the unfortunate men who have passed through his hands. That's why I hate him, and that's why I shall have my own revenge, in my own way."

McGowan's face was not a thing I liked to look upon, in that moment.

Then came the day when I felt the first detector beam. I had been wondering and doubting, but when it came it was unmistakable; a single sharp pain through every fiber of my body, like the exposed nerve of a tooth when it's unexpectedly touched; and then a strong, steady tingling utterly different from that of the radite ore.

I was with Blakely at the time. He stopped his work instantly. "We'd better go down and get McGowan," he said.

McGowan came back up with us. "What would you say, Reed? Think we're enough into that beam to have set off an alarm?"

"How close would you say we are?" I asked.

"According to my estimates, there must be at least another hundred yards of rock."

"Then I'd say we're safe. We must be on the very fringe of this beam. But if it weren't for me—"

"Yes, I know. But now your work's only beginning. We're going to have to cut parallel to the surface and get beyond range of the furthest beam before we can go up again."

McGowan was right. And this took several more weeks. We were very impatient now, but he impressed upon us the need for extreme caution. At last, however, we reached a point where I was definitely sure we were beyond the range. It had been agony for me, that constant proximity to the beams that seemed to tear at my every nerve-center; but I endured it and said nothing.

"This doesn't mean we're safe yet," McGowan cautioned us, when we began the vertical climb again. "To get near Marnick's house will be a problem in itself; he's sure to have it barricaded with beams, and we have to watch out for those two Jovian brutes of his."

I wonder if it could have been quite by chance that we broke through the surface during McGowan's turn? He must have had our distance calculated to the very foot. I felt a sudden current of fresh night air that nearly overwhelmed me, and then I saw that he had broken through.

We simply lay there for a long while, not speaking, breathing in that intoxicating air. I had never really known how I missed it until now; never had I known that the stars could be so close and so brilliant, until I glimpsed a handful of them through those few square inches of space.

At last McGowan carefully plugged that opening with a few bits of rock. He turned to me and said: "We must wait 'til tomorrow; we will bring the others."

It seemed to me that tomorrow would never come. At last, however, our next sleep period rolled around, and we met in our secret place. McGowan held a special, final little conclave.

"There is something," he said, "that I have withheld from you until now. As you all undoubtedly know, we are not entirely abandoned here; that is to say, twice a year an official Earth ship sets down to leave supplies and take aboard the radite we have mined. And I know what most of you have been thinking: that if we can once reach the surface, and get Marnick out of the way, we can hide out until that Earth ship comes, then overpower the crew and escape."

Murmurs of approval came from the six of us, especially from the group of Earthmen.

"I'm sorry," McGowan went on, "but that's not the way the thing's going to work out."

Sounds of discontent arose.

"Because I have a better plan. The Earth ship won't arrive here for two more months. Its crew outnumbers us, and they are well armed. Therefore, we won't wait for it at all; instead we'll take Marnick's own ship.

"Yes!" he exclaimed, smiling at the amazement on our faces, "he has a cruiser here. That's what I didn't want you to know until the last moment, for there is a difficulty. There are seven of us here, and the cruiser will accommodate only five at the most; it will take five across to Callisto, and there I can make connections that will mean safety for us."

We looked blankly around at each other, and no man knew what the other was thinking. McGowan smiled in a way I did not like, as if he somehow knew which five it would be.

"Furthermore," he went on, "there will soon be eight of us. For now Elson's got to come along."

"Elson!" exclaimed a chorus of voices, mine among them.

"Yes." McGowan's eyes narrowed infinitesimally. "I haven't steered you wrong yet, have I? I've worked out this entire plan, so believe me when I say that Elson is very necessary to our endeavor."

I thought of Elson, and wondered why he was necessary. He, to put it cruelly, was the least among us; the butt of all our jokes; for even hopeless men such as we must sometimes have amusement. Elson had been here probably as long as McGowan, but he had suffered much more. Elson always seemed to suffer Marnick's wrath when the latter couldn't decide upon a more suitable victim. Elson was twisted and misshapen now, the result of a fall through the shaft, so I had heard; and he was blank-eyed and feeble-witted.

Now McGowan sent for him, and he came shuffling into our cave with a bewildered look. Tersely McGowan explained the situation. Elson smiled crookedly; he had always had a special fondness for McGowan, and obeyed him implicitly in everything.

We began the climb. An hour later we stood panting but unbowed upon the surface, staring at stars most of us had not seen in years! We were eight men, determined, but armed only with the short metal hook we had used for digging out the rock. McGowan carried it. He gestured with it to the left, as he whispered:

"This way. We must be about a mile from the ravine where Marnick's located. Stay in sight of each other now, and watch your step—no noise!"

The terrain was rocky and rough; the horizon of the tiny planet seemed very near, and curved sharply down. The night was pitch black and boundless, with only the pinpoints of stars to guide us.

Hours later, it seemed, we glimpsed another pinpoint of light that was not a star. It was too low against the blackness for that; we knew it was a light from Marnick's abode, at the entrance of a rocky little canyon perhaps a quarter of a mile away. We proceeded with infinite caution.

Suddenly, I felt that awful agony through every nerve again, and I knew we had stumbled into more of Marnick's detector beams. This time we may have blundered far enough to set off an alarm, but I didn't especially care. I fell to the ground as the warning along my nerves persisted. For a minute I was almost violently ill. Luckily, the others stopped instantly. McGowan dragged me back and waited until I had recovered.

"Our human beam detector. Lucky we've got you with us, Reed!" But there was no humor in his voice, in fact I caught a note of pity. I think he already realized, just as I was slowly beginning to—

But I shall not think of that. McGowan spoke a few words to Elson that we could not hear. Elson nodded obediently. We moved away at a sharp angle to the right, but now I noticed Elson did not accompany us.

I was still dizzy and weak, but I clenched my teeth and determined to see this thing through to the finish. I guided us away from those beams. As near as I could determine, they rayed out in a sort of semi-circular barrier, invisible, of course. Carefully we skirted the edge of it, toward the far wall of the canyon that sheltered Marnick's house. How I stayed on my feet I cannot understand, for every step was an agony as the faintest out-reaches of those rays stabbed fiercely through me. The others, of course, felt nothing.

"We've got to get past it," McGowan whispered tensely to me, "or we're finished!"

I nodded curtly. I didn't know what McGowan had in mind, but I realized we had to get closer to Marnick's house. We came nearer and nearer to the canyon and then the power of the beams began to diminish. We pressed flat against the rocky walls and moved swiftly forward. Suddenly we were beyond the barrier. The squat stone dwelling was a bare fifty yards from us now, and we could see a little square of light from the side window.

We paused there in a huddled little group, wondering what McGowan's next move would be. Apparently he was waiting for something. And a second later we knew what it was, as a ringing alarm shattered the silence! I knew it must have been Elson out there who had set it off, according to McGowan's instructions. I glanced sharply at McGowan and he seemed satisfied, as he cautioned us to silence.

Another square of light appeared and we glimpsed the tall form of Marnick in the open doorway. But he knew better than to remain there long against the light. He stepped quickly outside, but not before we glimpsed an atom-pistol in his hand.

"This is it!" McGowan whispered. "I only wanted to get him outside." We moved silently across the space toward the side of the house that hid us from Marnick. There we could peer into the lighted window. I saw a large room quite like a library, and I was amazed at how richly it was furnished, with books and tables and tapestries and a fireplace at one end. It seemed utterly incongruous here on this dark, mad planet.

But I didn't have much time to think about it. McGowan was fumbling at the window, and at last it swung silently open. "I've got to get hold of a weapon!" he whispered. "The rest of you wait here. I don't think Marnick will come around to this side, but keep a sharp lookout anyway." With that he climbed through the window and moved silently across the room.

Anxiously, I watched him, expecting Marnick to return at any moment. McGowan searched the room thoroughly, opening drawers and tumbling books in disarray, but no weapon was forthcoming. He did find a small flashlight, however, and with it in hand he moved into another dark room leading off this one, there to continue his search. He was out of my sight now, but I glimpsed his light flashing around cautiously. The seconds seemed like eternities.

I was so interested in watching the inside of the house that I had almost forgotten my companions behind me. Suddenly, I heard a muffled commotion near by, and whirled quickly around.

The two Jovians had crept silently upon us out of the darkness; perhaps Marnick, as a cautionary measure, had sent them out to scout around the house. At any rate, there was a silent struggle of bodies behind me, and all I could distinguish clearly was one of the Jovians who had seized V'Narik's neck in his two powerful hands. Blakely was standing there with the heavy metal hook upraised, and it seemed to me that he hesitated about ten seconds too long before he brought it crashing down on the Jovian's skull. But by that time V'Narik was dead, and it suddenly dawned on me that Blakely's hesitation had been deliberate; and that left only seven of us instead of eight.

The other Jovian was more than holding his own, and Blakely seemed content to watch. I seized the heavy bar from him and leaped into the mêlée, waiting for an opening. I brought the bar wildly down, and by pure luck it landed on the Jovian skull, crushing it like an eggshell. The others staggered weakly up.

I leaped back to the window, for I thought surely Marnick must have returned; what I didn't realize then was that scarcely a minute had yet elapsed since the alarm had sounded. But McGowan had found his weapon. He held an atom-pistol in his hand as he crossed the lighted room to the window, and climbed back out to us.

It was not until that moment that I had my curious foreboding. McGowan, if he had wanted to kill Marnick, could easily have crossed that room to the front door that was still open, and rayed Marnick down from behind. He wanted to kill Marnick all right, but in his own way. He had his own special revenge mapped out. I suddenly remembered that, and I knew that McGowan was going to carry it through.

"So far so good," he murmured as he rejoined us. He weighed the atom-pistol familiarly in his hand. "Now, if only Elson out there comes through all right—Come on, let's see where Marnick is. Not too far from the house, I hope. And remember, all of you, this is strictly my party; so no interference."

Those last words struck an ominous note in me, but I said nothing, nor did the others as we followed McGowan along to the far corner of the house. There we could see the long, dim rectangle of light from the room streaming out onto the barren rock. Marnick was not in sight but we knew he must be somewhere very near, waiting in the darkness, watching for whoever had set off that alarm.

Seemingly, for a long while we waited, but it couldn't have been more than a minute; we crowded close to each other, staring, trying to accustom our eyes to the night. Then McGowan pointed, and we saw a darker shape very near the house, and we knew it was Marnick, waiting.

Again that curious feeling of impending drama overwhelmed me, and I wanted to act to prevent something, but I didn't know how—or what—

McGowan's gesture shifted imperiously, and we saw another vague blur of a figure out there and we knew it was Elson. McGowan, in that moment, reminded me of a stage director, proud of his work and trying to impress its subtleties upon us. My gaze went back to the slouching figure of Elson, and I realized he was moving toward us.

Marnick saw him at the same time. Marnick straightened up, leaned tautly forward and seemed to be peering. Then Marnick's hated voice came stabbing through the darkness to us, but not directed at us:

"I see you out there. Whoever you are, it was foolish of you to try to come near my house, for you have set off a detector beam. Stop immediately or I will blast you. I have an atom-pistol trained on you at this moment."

For a single instant everything seemed to stand still. Elson stood still. McGowan, close beside me, caught his breath sharply in his throat. Then Elson moved forward again, and McGowan breathed a slow sigh of relief.

"Good," he murmured in my ear, though I am sure he was not conscious that I was there. "I knew Elson would obey me. Elson obeys me in everything." And then: "Poor Elson."

In that sudden moment I realized what was going to happen; I knew McGowan had planned this step by step from start to finish, and I knew Elson was going to die! I started forward with a cry in my throat, but McGowan's hand clamped roughly over my mouth and his fingers dug cruelly into my arm.

I could see, though, and I saw Elson come forward in his slouching, ungainly gait, arms dangling at his side and an idiotic grin on his face. I heard Marnick's warning once more, and I saw the almost invisible beam of his atom-pistol slashing the darkness. I saw Elson stumble and plough forward on his face and lay still. And not until then did McGowan release me.

But then it was too late. Elson was dead, and I heard a sound that was almost a chuckle deep in McGowan's throat. Then his voice slashed through the darkness and I realized that here was the acme of triumph in all his years of planning:

"Drop your pistol, Marnick."

Marnick whirled toward his voice and took a tense step toward us; but McGowan's pistol rayed across the rock and slashed dangerously near Marnick's feet. Marnick's pistol dropped from his fingers with a clanging sound.

"That's better. You're a madman, Marnick, but not too mad to fail to realize when the game is over. I'm going to kill you, I want you to know that; and I want you to know who is speaking. This is McGowan. But before I kill you I want you to realize what you've done tonight. You've killed a man. Know who it is? Go take a look."

Marnick stood there hesitant. I could almost picture the indecision on his face. But McGowan's pistol rayed again, very close to his feet, and Marnick stumbled out to where Elson lay.

"Good," McGowan went on. "Now look at 'im. It's Elson, you see?" McGowan's voice seemed different now than I had ever heard it. It wasn't his voice at all. But it went on inexorably, and I felt chills chasing up and down my spine.

"Do you know who Elson really is, Marnick? No, of course, you don't. I saw to that. He came to this prison planet about the same time I did. He was tall and straight and youthful then, but somehow you couldn't stand that; you made him your special victim, you tortured and maimed him and now you've killed him. Look very closely, Marnick. You still do not know? Then I suggest you turn him over—that's right. And I suggest you look very closely on the outer part of his left thigh. A curious blemish is there, an unmistakable birthmark. You realize now? Yes, I see that you do.

"Your son, Marnick, never died on Mars. I was one of that party of men who—Well, I don't care to think about that now. The others left him there beside his mother, thinking him dead, but I knew better. I went back and took him, and kept him with me until he was sixteen, when we parted. Perhaps he inherited some of his criminal ways from his association with me. Anyway, when I was sentenced here, and he came a little later, I knew what I must do!"

It was a nightmare. I couldn't believe it. I glimpsed Marnick out there huddling over the body of the man he had just slain ... his own son ... and even at that distance and through that dimness there was something that made me feel sorry for him.

He arose very slowly, turned to face McGowan and tried to speak something but could not. He took a few faltering steps in our direction and then McGowan rayed him down. There was still a satisfied little smile on McGowan's lips as he did it. I hated McGowan in that moment as much as I had ever hated Marnick, but I could do nothing, for my mind was a little numbed.

"I waited seven years for that," McGowan said, and he breathed very deeply. Then he walked through us and strode back to where the two Jovians lay, and V'Narik.

"V'Narik's dead," he said as if he'd just discovered it. "He always had a hunch he wouldn't get away from here, didn't he? But he got to see the stars and Mars again, just as he wanted to. And Elson's dead, of course. That still leaves six of us." He looked at me significantly.

I knew what he meant. I had known all the time that I would never set foot on Earth again, and McGowan had known it, too. "Make it five," I said, "for I'm staying."

The others didn't quite understand, and they didn't much care. They went rushing off to find Marnick's cruiser that would bear them safely to Callisto. McGowan stepped forward with that enigmatic smile on his lips, and seized my hand.

"Thanks," he said simply. "Thanks for all you've done for us, and don't hate me too much."

"Just go away," I said, "and leave me alone. I want to think. You might leave me that atom-pistol if you want to."

It is a good thing they left as quickly as they did, or I would have killed McGowan. I watched their cruiser blast up and away into the dark void. I said I wanted to think, and I have thought. And whenever I remember that terrible revenge, I must decide that McGowan was the madman, not Marnick. Perhaps they were both mad. Anyway, it does not matter any more.

I only know that I shall soon die; for my constant proximity to those detector beams in the past several weeks, in conjunction with these radite emanations, has produced a curious illness in me from which I know I should never recover. The symptoms become stronger hourly, and the agony is almost unbearable. Perhaps soon, if it continues, I shall—

But I must finish this document first. I have been writing it, here in Marnick's study, for the past twenty-four hours. I hope it will be found when the next Earth supply ship comes. I think it even likely that those other unfortunate men, in the tunnels below, will continue to work as usual until then, unknowing of what has taken place up here; for they have become automatons.

I can only hope that this document will serve, in the future, to make the fate of such men a little less severe.

Well, now I think it is finished.