TRANSCRIBER’S NOTE

The cover image was created by the transcriber and is placed in the public domain.

Some minor changes to the text are noted at the end of the book.

1913

Indianapolis Printing Co.

Printers

This history is based on my pocket memorandum which I kept during the late Civil War, 1861-1865.

Richard J. Fulfer.

General Fremont.

U. S. Grant.

N. P. Banks.

E. S. Canby.

W. T. Sherman.

DIVISION OFFICERS.

General Pope.

Lew Wallace.

A. P. Hovey.

General McClernard.

E. O. C. Ord.

C. C. Andrews.

REGIMENT OFFICERS.

Colonel A. P. Hovey.

Lieutenant Colonel Gurber.

Major C. C. Hines.

Colonel William T. Spicely.

Lieutenant Colonel R. F. Barter.

Major John F. Grill.

Captain—Hugh Erwin.

First Lieutenant—George Sheaks.

Second Lieutenant—H. F. Braxton (resigned). J. L. Cain.

First Sergeant—Richard F. Cleveland. (Non-commissioned.)

Second Sergeant—John East. (Non-commissioned.)

Third Sergeant—Francis M. Jolley. (Non-commissioned.)

Fourth Sergeant—Henry B. East. (Non-commissioned.)

Fifth Sergeant—Van B. Kelley. (Non-commissioned.)

First Corporal—Josiah Botkin. (Non-commissioned.)

Second Corporal—Chas. H. Dunnihue. (Non-commissioned.)

Third Corporal—J. N. Wright. (Non-commissioned.)

Fourth Corporal—John Edwards. (Non-commissioned.)

Fifth Corporal—George F. Otta. (Non-commissioned.)

Sixth Corporal—William Erwin. (Non-commissioned.)

Seventh Corporal—King A. Trainer. (Non-commissioned.)

Eighth Corporal—Jasper N. Maiden. (Non-commissioned.)

Musician—James S. Cole.

Teamster—Alfred Cambron.

Hospital Steward—Robert J. Mills.

Sergeant Major—George A. Barnes.

Arms, Thomas R.

Bartlett, Haines.

Blevins, Willoughby.

Busic, William S.

Clark, John C.

Clark, William G.

Cole, William C.

Coward, Joel.

Coward, James.

Collins, James W.

Conley, David.

Cox, Andrew.

Crow, Walter S.

Douglass, Edgar L.

Edwards, William.

Enness, Charles.

Erwin, Jarred.

Fulfer, Richard J.

Fullen, John.

George, Andrew J.

Harvey, James.

Hamer, Henry.

Hamer, George.

Hostetler, Samuel.

Harbaugh, Benjamin F.

Higginbotham, David D.

Gross, James A.

Gross, Wm. C.

Jolly, George W.

Keedy, William.

Lee, John.

Lochner, John C.

Lynn, Ephriam.

McPike, Francis M.

Melvin, William

Mitchell, William H.

Neugent, Willoughby.

Orr, Patrick.

Painter, Noah.

Palmer, Noah.

Peters, Henry C.

Phipps, David.

Phipps, Isaiah.

Ramsey, William W.

Riggle, Timothy.

Robbins, William.

Smith, F. M.

Staples, Abraham.

Stotts, David.

Stroud, Washington.

Tanksley, Charles.

Teft, James.

Tinsley, David.

Toliver, John.

Walker, Wesley.

Williamson, George.

Williamson, Joseph.

Woody, Henderson.

Pruitt, David R.

Pace, David.

Walker, Lewis.

Bearley, William T.

Melvin, Ezekiel M.

Clark, Francis M.

Harvey, Robert.

Landrom, Archie.

Dodd, John S.

Watson, Thomas.

Deceased—

Discharged—

Dalton, James R.

Hostetter, John W.

Keithley, Jesse.

Mitchell, Isaac.

Rudyard, Jeremiah.

Stogell, Hamilton R.

Helton, Pleasant.

Williams, Solomon.

Low, John C.

Andrews, James T.

Miller, William.

Harvey, Bird.

Landreth, William H.

The places at which the different companies were made up:

| Company | A—Bedford | Lawrence County, Ind. |

| “ | B—Paolia | Orange County, Ind. |

| “ | C—Evansville | Vanderburgh County, Ind. |

| “ | D—Washington | Davis County, Ind. |

| “ | E—Petersburgh | Pike County, Ind. |

| “ | F—Princeton | Gibson County, Ind. |

| “ | G—Orleans | Orange County, Ind. |

| “ | H—Petersburgh | Pike County, Ind. |

| “ | I—Logotee | Martin County, Ind. |

| “ | K—Medora | Jackson County, Ind. |

| Names. | Located at. | Date. |

| Knox | Vincennes, Ind. | August 18, 1861 |

| Jessey | St. Louis, Mo. | August 2, 1861 |

| Allen | Carondalet, Mo. | September 16, 1861 |

| Jessup | Syracuse, Mo. | September 20, 1861 |

| Lamine Bridge, Mo. | September 24, 1861 | |

| Georgetown, Mo. | October 16, 1861 | |

| Tipton, Mo. | October 21, 1861 | |

| Burr | Missouri | November 1, 1861 |

| Near Springfield, Mo. | November 9, 1861 | |

| Warsaw, Mo. | November 16, 1861 | |

| S. E. of Tipton, Mo. | November 27, 1861 | |

| S. of Syracuse, Mo. | November 29, 1861 | |

| N. E. of Sedalia, Mo. | December 8, 1861 | |

| Below Sedalia | December 15, 1861 | |

| Otterville, Mo. | December 23, 1861 | |

| Fort Donnelson, Tenn. | February 18, 1862 | |

| Fort Henry, Tenn. | March 1, 1862 | |

| Crump’s Landing, Tenn. | March 18, 1862 | |

| Shiloh, Tenn. | April 18, 1862 | |

| Broomsage | May 10, 1862 | |

| Gravel Ridge, Tenn. | June 5, 1862 | |

| Boliver, Tenn. | June 8, 1862 | |

| Union Station | June 12, 1862 | |

| Memphis, Tenn. | June 18, 1862 | |

| White River, Ark. | July 4, 1862 | |

| Helena, Ark. | July 5, 1862 | |

| Vicksburg, Miss. | July 4, 1863 | |

| Jackson, Miss. | July 10, 1863 | |

| Vicksburg, Miss. | July 20, 1863 | |

| Natchez, Miss. | August 5, 1863 | |

| Carrolton, La. | August 13, 1863 | |

| Brasier City, La. | October 3, 1863 | |

| New Iberia, La. | October 6, 1863 | |

| Vermillion Bayou, La. | October 10, 1863 | |

| Camp View, La. | October 18, 1863 | |

| Barres Landing, La. | October 21, 1863 | |

| Opelousas, La. | October 21, 1863 | |

| Caron Crow Bayou, La. | November 1, 1863 | |

| Vermillion Bayou, La. | November 5, 1863 | |

| New Iberia, La. | November 9, 1863 | |

| Algers, La. | December 22, 1863 | |

| Evansville, Ind. | March 2, 1864 | |

| New Orleans, La. | April 3, 1864 | |

| Baton Rouge, La. | August 16, 1864 | |

| Morganza Bend, La. | December 24, 1864 | |

| Baton Rouge, La. | December 25, 1864 | |

| Shell | Carrolton, La. | January 5, 1865 |

| Mud | Kennerville, La. | January 19, 1865 |

| Redoubt | Pensacola, Fla. | January 26, 1865 |

| Beauty | Florida | February 11, 1865 |

| Fort Blakely | April 9, 1865 | |

| Fort Spanish, Fla. | April 12, 1865 | |

| Selma, Ala. | April 29, 1865 | |

| Mobile, Ala. | May 8, 1865 | |

| Galveston, Texas | November 16, 1865 |

The Twenty-fourth Indiana regiment was one of the first called for as three years’ volunteers. We were enrolled on the 9th day of July, 1861, to serve for three years, if not sooner discharged. We were mustered into service July 31st, 1861, at Camp Knox, which is near Vincennes, Indiana.

Our first camp life after being enrolled was a new mode of living and sport. Some of the boys had never been very far from our homes, and were not posted in the pranks and tricks of the times, even in those early days.

We soon drew a few old Harper’s Ferry muskets. We had a string guard around the camp. Company drill was held four hours each day. This was the only amusement which we had in the daytime, but at night we had magicians, sleight of hand performers, and others who made amusement for some of us who had never seen many shows. The tall man and elephant also paraded through the quarters at night, and this furnished a great deal of amusement for us.

We got our uniforms August 7th. They were gray and were about as appropriate as our old Harper’s Ferry muskets. The guards soon beat the stocks off of the muskets and bent the ends of the barrels. These they used as canes.

Getting used to camp life was quite a change for some of us who had been raised up on corn bread, hominy and buttermilk. There was also a change in the bill of fare. We now had hard tack, sow belly, and black coffee. There were many other[16] changes of life which must be made to make us a happy, united family.

The weather was very warm at this time, and we soon began to think that army life was no soft snap.

On the 16th of August we again drew arms. These were new Harper’s Ferry muskets. Six Enfield rifles were allowed to each company.

On the next day we marched through the city of Vincennes on review. All was a hurry and excitement, as the troops were being sent to the front on that day.

We got marching orders on the 18th, and we got on board a train bound for East St. Louis, Ill. We arrived there on the morning of the 19th. We crossed the Mississippi river on the steamer “Alton City,” marched two and a half miles through the city of St. Louis, Mo., and went into camp in the Lafayette Park. Here were the first tents we ever pitched, and all the boys wanted to learn how.

Lafayette Park is a beautiful park. It contains many fine animals. There were many of our boys who had never seen such sights as the city of St. Louis contained. Some of them had sore eyes on account of so much sight-seeing.

There were many regiments in camp at this park at the same time we were there.

In a short time we struck tents and marched down the river a distance of seven miles. We went into camp at Carondelet. One of the officers named this camp, Camp Allen.

August 27th, Colonel Alvin P. Hovey took command of our regiment. He soon commenced battalion drill, which was very hard on us, owing to the warm weather. We had battalion drill four hours each day and company drill two hours, so you see that we were somewhat busy.

September 6th, Colonel Hovey, with six of our companies,[17] boarded a train on the Iron Mountain railway and made a trip of twenty-five miles. We left the cars at 8 o’clock p. m. and made a rapid march of several miles out through a very rough, broken country. At 5 o’clock in the morning we got orders to lie down on our arms for a little rest, but not to speak above a whisper and to be ready to fall in line at a minute’s notice. When morning came we learned that the rebels had evacuated their camps and skipped. Thus we were knocked out of a fight at this place. On account of not having any rebels to shoot at, we could do nothing else but march back over the roughest roads we had ever marched on.

Here was our first experience in foraging off of the country. But we got a plenty on this trip, such as cream, honey and peaches—all of which were good things that we could not get in camp.

This trip was called the Betty Decker march. I don’t know why this name was given it unless she was the lady who furnished us so many good things for our suppers.

We got back to the railroad at 8 p. m., got aboard a train, and at 10 o’clock arrived at our camp at Carondelet.

While here we had to guard the dry docks while the ironclad vessels, St. Louis and Carondelet were being built. It was rumored that these vessels would be blown out of existence before they were finished, and as half of the people in St. Louis were ready to do anything for the Southern cause, we believed it. But nevertheless they were completed and had an active part in putting down the rebellion.

While we were drilling and guarding at this place we could see other regiments at Benton Barracks who were strengthening their fortifications. Now was the time when something had to be done to invade Missouri.

September 16th, 1861, we got marching orders, struck tents, and boarded a steamboat which carried us to St. Louis. We left the boat and while marching up Main street on our way to the Union station was the first charge which the old Twenty-fourth struck. Drums and fifes were playing when four large gray horses drawing a big delivery wagon collided with the head of our column, knocking it east and west. Several of our boys were slightly bruised, but they were more frightened than injured. In this way James R. Dalton and John W. Hostetter got their discharges.

That night we boarded a train, pulled by two engines, of twenty flat cars, fifty men to a car. We started westward to open up the Union Pacific railroad over which a train had not run for months. The weeds had grown upon the track until the engines could hardly pull their own weight. We traveled very slowly, and the morning of the 17th found us not many miles from St. Louis.

Half of our train had been cut loose and the engines had pulled on to the next switch. They soon returned for the balance of the train. At this place we heard the first national songs which we had heard sung in rebeldom. Some ladies carrying the grand old Stars and Stripes came out on the portico and sang “The Star Spangled Banner,” “The Red, White and Blue,” and other national songs. You bet there were cheers which went up for those union ladies.

This was the first time that Colonel Hovey knew that In[19]diana soldiers would eat chickens. But he found it out now, as the boys came straggling to the cars, at the call of the whistle, loaded with chickens and peaches. Colonel Hovey called, “Take them back, you d—— chicken thieves, or I’ll have you arrested. I didn’t think I had started out with a clan of Indiana thieves.”

Some of the boys became angry and made threats, while others laughed and were jolly about it. But it was all soon forgotten as the train pulled out. We had to walk by the side of the engine and throw gravel under the drive-wheels so that the engine would pull anything.

We went through three tunnels and came to Jefferson City. This is the capital of Missouri. Governor Jackson had the State House burned and skipped out with the old rebel, General Price.

At 11 o’clock p. m., September 7th, two engines, coupled together, and pulling our full train, went on west. Just as we started one of the boys of Company D fell under the car and was instantly killed.

On the morning of the 18th the engines could not pull their own weights and each company cut loose and pushed their own cars. While doing this, Brown of Company B, fell under the car and the wheels ran over his leg.

We pushed up the grades and rode down them. Sometimes we even had to push the engines.

We reached Syracuse late on the evening of the 18th. We got off of the cars, marched out and went into camp near the town. A strong picket line was posted and a strict order was placed on the pickets. A heavy penalty of death was imposed on those who slept on their post.

The moon shined bright and at 10 o’clock the still night air was disturbed by the tramp of horses’ feet and rattle of sabers coming towards our camp. The picket who was posted on the[20] road did not wait to challenge the supposed enemy, but fired his gun and skedaddled to camp. The pickets all around the camp fired their guns and ran.

The long roll was beat and all was hustle and bustle in camp. “Fall in, fall in!” was the order from colonel and captains, “and get ready for action.” In four minutes the old Twenty-fourth was ready for action and facing the supposed enemy. Several were shaking as with the ague, yet they were ready to take their medicine.

In a few minutes we saw a single orderly coming down the road. He rode up and asked, “What the h—— does this mean?” Colonel Hovey, standing there in his night clothes, with his fighting blood up, answered him pretty roughly and wanted to know who it was. We found out that it was Colonel Eads’ home guards of “Jayhawkers” who had come from California to join our army. We then broke ranks and went back to our quarters to dream of the false alarm and the excitement which Colonel Eads’ Jayhawkers caused us.

On the morning of the 20th we struck tents and marched seven miles west. Here, at the Lamine river, we went into camp. THIS camp was called Camp Morton.

The next morning heavy details were sent out to build fortifications for picket duty and to guard the Lamine bridge while the carpenters rebuilt it. This bridge had been burned by the rebels a few days before we got there.

The Twenty-fourth Indiana was the first regiment to arrive at this place, but there were more brigades on the way to reinforce us, some by way of the Missouri river and some by rail, as we had come.

On the morning of the 23d we were joined by the Second Indiana Cavalry. We now had the bridge completed, and the[21] trains ran over it and went as far as Sedalia, this being as far as the road was completed at that time.

At about this time, the Eighteenth and Twenty-sixth Indiana landed on the banks of the Missouri river, and it being a very dark night, they ran into the Twenty-second Indiana. They had quite a little spat before they found out their mistake. The Major and six men of the Twenty-second were killed.

On the 30th of September we marched to Georgetown, the county seat of Pettice county. It was dark when we reached the town. As we found no enemy to oppose us we went into quarters in the court house.

Here the Eighth, Eighteenth, Twenty-second, Twenty-fifth, Twenty-sixth Indiana regiments and the Eighth Missouri and ten pieces of artillery joined us. We were collecting an army to raise the siege of Lexington, which was twenty miles above here. Rebel General Price had had Colonel Muligan, with a handful of our soldiers, cooped up there for several days. General Fremont was getting his troops together to raise the siege, but he was too slow. The little garrison of 2,800 Union men defended the fort five days against a superior force of 11,000 men.

An order was given to mount the Twenty-fourth Indiana on mules. We marched to the corral and tried to break several of those wild bucking mules. The order was countermanded. That evening we started on the march, but had only gone a few miles when we met our paroled prisoners. They reported that they held out five days and then ran out of rations and ammunition. They also stated that their loss was 60 killed and 40 wounded. The rebel loss was unknown.

We about faced and went back to camp. On the 5th of October we moved out on an open field and pitched tents. Here[22] we drew two months’ pay. This was the first time that we had ever drawn any of Uncle Sam’s money. The officers were paid with gold coin.

While at this place we drilled six hours each day. We received marching orders on the tenth of the month, but the order was countermanded. On the morning of the 16th we again received marching orders. We struck tents and marched a distance of two miles to Sedalia, a town at the end of the Pacific railroad.

The war had stopped all the progress of the railroad. The workmen had stacked their shovels, picks, and wheelbarrows in a large cut and had fled in all directions.

We boarded a train and went to Tipton, which was twenty miles distant. Here, on the 19th, we drew uniforms.

On the morning of the 21st we received marching orders, struck tents, packed our knapsacks and marched in the direction of Springfield, which is south of this place. At the end of a fifteen-mile march we halted and went into camp. On the morning of the 2d we continued our march. At 4 o’clock we came to a halt and went into camp in a little black-oak grove. Our feet were blistered from marching over the rough mountain roads, and many of the boys fell out of the ranks and straggled in late at night.

On the morning of the 24th we took up our line of march. After a hard day of travel we came to the little town of Warsaw. We crossed the Osage river and went into camp.

While here General Fremont received the news from one of his spies that General Price’s army was at Springfield. We were called into line early the next morning. We moved out seven miles and the order was then countermanded. Therefore we went into camp in a field which was covered with burrs. For this reason we named this place Camp Burr.

Our boys were about played out on account of heavy marching, and so each of our companies bought an ox team to haul our baggage. Our quartermaster sent our train back to Tipton after supplies of ammunition and rations. This was supposed to be our base of supplies.

On the evening of November 1st, 1861, we received orders[24] to leave our tents, and in light marching order move out and march in the direction of Springfield. At 8 p. m. we moved out eight miles through the dark night and came to our main army to consolidate our regiment with our division, brigades, etc., which were commanded by Generals Pope, Hunter, and Jeff C. Davis.

The next morning we marched through a little town by the name of Black Oak Point, and after a hard day’s march we went into camp in a meadow. We were all very tired and foot-sore.

On the morning of the 3d we marched through the little town of Buffalo, crossed Greasy Creek, and went into camp.

We were all worn out with the day’s journey. Most of us had eaten a cold lunch and had lain down for a little rest. A few of the boys were cooking beef and trying to prepare some food for the morrow when the bugle sounded the assembly to fall in line and march. We slung knapsacks, fell in line, and marched off in double quick time. Some of the boys were swearing because they had to throw their beef, which had just started to boil, out of the kettles.

We felt sure that we would have a chance to take old General Price in that night. Everyone was worn out and angry, and their fighting blood was at its highest pitch. We marched all night, and early in the morning we waded Pometytor creek. We then halted for a short rest. We had nothing for breakfast except a few pieces of hard tack to munch on.

This was the 4th day of November. After a short rest we fell in line, marched off as fast as our swollen feet would allow us to. At 4 o’clock we reached Springfield. After a forced march of fifty miles, without sleep and with very little to eat, we were in splendid fighting order—mad and worn out.

But our chance for a battle had slipped.

As old Price’s army had skipped, all mounted on gray horses, General Fremont with his one hundred bodyguards, started in pursuit. They ran into Price’s rear guard. I heard some shots fired, and it was reported that a few shots were exchanged with the rear guard of General Price’s retreating army.

Here we forced a junction with General Lane’s army, which swelled the number of our forces to about 35,000. General Lane had several Indians under his command—some 1,200 Cherokees. It was reported that he sent them after the rebel forces which were retreating towards Cassville, which is in Barry county. I never heard of those Indians afterwards. They must have been disbanded.

We went into camp that night about a mile from town. On the morning of the 5th of November, Colonel Hovey took command of a brigade.

On the night of the 6th, cheering was heard throughout our army, as some grapevine or false dispatches had reached our officers of a great victory gained in the east. The thunder of drums and voices were heard for miles.

General Fremont received instructions not to follow Price farther into the mountains, or he would be caught in a trap. On the morning of the 9th we received orders to march back to Tipton.

On the 13th our regiment and the Forty-second Illinois marched on a race to Camp Burr. We beat them by five hours. On the morning of the 14th we made double quick time back to Osage Bridge, in order that we might get there before General Sturges’ brigade arrived there. We crossed the river and went into camp. We stayed two days waiting for our supply train.

We went to Tipton on the 20th of November. This completed the Springfield march.

While on this expedition General Fremont issued a proclamation to free all the slaves who made their way into our lines. Soon they were flocking in by the score. For assuming this authority General Fremont was superceded by General Pope. His name was never mentioned again in the history of our late civil war, as he was placed on the retired list of our good old generals who had served their time faithfully in our past wars.

We pitched tents at Tipton and went into camp for a few days rest. The weather was getting somewhat cold, making our camp life somewhat disagreeable. We stayed here until the morning of the 27th, when we struck tents and marched to Syracuse. Here we went into camp and stayed until the morning of the 29th, at which time we got orders to march back to Tipton again. We were getting tired of running around so much, and having no fighting to do, as we had been promised that we would put down the rebellion in thirty days. As yet we had not even made a start. Some of our boys were getting homesick and wanted to fight it out in a pitched battle. Some of them thought that they could clean up five little greased rebels.

We went into camp two miles north of Tipton, in a little grove. On the night of December 1st five inches of snow fell, we then had a grand time hunting rabbits. We remained here until the 6th, when we drew two months’ pay.

We broke camp the next day and marched to the Lamine bridge. A heavy rain fell that night, overflowing our camp and making it a disagreeable place. We lay here until the morning of the 15th, when we got marching orders to move over to Sedalia. We went into camp a little north of town. While here we received the report that our advance under Pope had captured 1,540 prisoners, without firing a shot.

While here we formed a scouting party detailed out of the Twenty-fourth Indiana. Concealed in covered wagons we traveled all night. In the morning we came to an open prairie.[28] From here we sent part of the detail to a large mill and distillery. A few shots were exchanged between the guards and our boys. In a short time the guards mounted their horses and rode as if for their lives. There were about twenty men on guard. They had a number of bushels of corn, several pounds of bacon, and some barrels of old copper distilled whiskey. The boys loaded one of our wagons with the beverage and set fire to the building. We then started back to Sedalia, as we had accomplished what we were sent to do. On our way back the wagon loaded with whiskey broke down and we had to leave it. Out of all of that whiskey we only got a small drink of whiskey each. We reached camp and reported our success. As soon as it was dark Lieutenant Sheeks, with a small detail, started after the wagon which we had left.

Colonel Eads had run across the wagon and went into camp at this place. They were having a time drinking the good old liquor which the wagon contained. The night was very dark, and when Lieutenant Sheeks reached the top of the hill he heard quite a number of men around the wagon. Thinking that they were rebels, he ordered the boys to fire into them. Colonel Eads’ men also thought that we were rebels, and returned the fire. After several shots were exchanged, Lieutenant Sheeks withdrew, as we were outnumbered five to one. We never learned of our mistake until the next evening. No one was seriously injured, as all the shots flew wide of their mark on account of the darkness. This battle was named “Sheeks’ Defeat.”

While here a five-inch snow fell, making a very disagreeable time. On the night of the 23d of December we got orders to march back to our old camp at Lamine Bridge. This was one of the coldest, hardest marches of our service. While on the journey a sleet fell and froze. The batteries all had to be left[29] at the foot of the hills, as the horses could not pull them up the hill on account of it being so slippery.

When we reached camp we were almost frozen and there was no wood to make fires with. We had built log cabins here for winter quarters, but there was no chance to get fire only to tear down our cabins. We did this and piled the logs in heaps. We set fire to these. We made coffee and soon became warm and comfortable.

We soon began preparations for sleeping. We spread tents on the snow and sixteen to a bed we lay down and pulled our blankets over us. A snow fell, which covered us over and kept us warm. When the reveille sounded at four o’clock the next morning it was a sight to see the boys crawling out from under their snow beds to answer roll call.

A heavy detail from the Twenty-fourth Indiana was sent to pull the batteries up the hill. The horses and mules had failed but the old Twenty-fourth was reliable.

The 24th of December found us with tents once more, with tents pitched at the Lamine Bridge. On Christmas Day some of the boys got drunk on stomach bitters and had a jolly time.

January 1st, 1862, we had a general inspection. Our work at this place was hard, as we now built Fort Lamine. The snow lay on the ground six inches deep, and the ground was frozen to a depth of eighteen inches. This made it slow work building fortifications. Some days each man could not pick out a yard of the frozen dirt.

While at this work several of the boys froze their hands and feet and some of them had to have their fingers and toes amputated. These received discharges.

January 18th a detail of twenty men was called out to go with a foraging train after hay and corn. We went ten miles northwest. Here we found plenty of hay and corn. We camped[30] in negro quarters. We killed a hog and had the negro cooks to get our supper and breakfast.

We loaded our train and gave the old farmer a due bill on Uncle Sam and started to camp with lots of good things, such as apples, honey and potatoes, hidden in the hay. The weather continued to turn colder, and we almost froze on our return to camp.

On the 12th another train composed of ox teams, was sent after corn and hay. Several of the guards of this train were badly frozen.

On the 15th we drew Sibly tents and stoves, but it wasn’t before we needed them. On the 27th we drew pay for two months. We also drew plenty of rations. We had bacon to spare. There was no wood to burn in our little sheet iron stoves and so we kept them red hot with bacon.

The citizens brought cakes, pies, apples, and cider into camp and sold them cheap. The boys ran some of them out and called them rebels, but we had not yet seen a real rebel.

At about this date we had one soldier in Company I who did not fill inspection. For this a detail carried him to the Lamine river, cut the ice and stripped and washed him all over. He was afterwards one of our best lieutenants.

After February 1st, 1862, our camp duty was lighter. A string guard which was composed of the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Illinois, Twenty-fourth and Twenty-sixth Indiana, and Fryberger’s battery of six twelve-pound guns, was placed around the brigade at this fort.

Friday, February 7th, 1862, we received marching orders, struck tents, and marched as far as Syracuse. On the 8th we marched through Tipton and on the evening of the 10th we went into camp near Jefferson City. We stayed in this camp until the 13th, when we went to town. Here a part of the regiment had quarters in the State House and the rest were in a large church house.

The weather at this date was below zero and there was plenty of snow on the ground. We had marched about eighty miles, over a very rough road and were worn out. Some of the boys almost played out on the morning of the 15th.

Stowed away in box cars, with fifty men to a car, we started for St. Louis. Early in the morning our train stopped at a small station for fuel and water. We were just in front of a little saloon, and as the boys were almost frozen, some were allowed to get out and get them a dram. Frank Smith, of our company, brought back a five-gallon keg of peach brandy and rolled it in through the car door. The door was closed as soon as all could get in. Some kind of a hammer was procured and the head of the keg was knocked in. The boys soon had their cups filled with brandy instead of coffee. The train started and the boys soon had the brandy keg emptied.

There was no more complaining of the cold, but it was certainly a mixed up drunken mess. Some of the boys wanted to fight but it did not amount to much because we were too thick and crowded to fight.

We got to the Union depot at St. Louis at 7 p. m. and at 8 o’clock we marched on board the steamer Iatan. On the morning of the 16th we ran into blocked ice at Cairo, Ill., the place where the Ohio runs into the Mississippi. We had to hammer away about four hours in order that we might get through the ice.

We passed Cairo, turned up the Ohio river, and landed at Paducah, Kentucky.

Here, on February 17th, we heard of the surrender of Fort Donellson. Several boats were lying at this place filled with the wounded. We went on up the river to Smithland, and here we turned our boat up the Cumberland river.

On the morning of the 18th of February, 1862, we landed at the Bluffs, under the big guns of Fort Donellson, Tennessee. We marched out through the dead bodies of both armies which had not yet been buried, for our troops were almost played out after three days of hard fighting.

During the battle, General Pillow and Johnson cut their way through our lines and made their escape to Nashville with a brigade. Our final charge was made on the 17th, at which time the garrison surrendered with 5,000 prisoners and a number of heavy guns which were mounted on the fort. Our loss at this place was heavy, about 1,500 in killed, wounded and prisoners. The rebel loss was about 1,800.

We went into camp on a small island opposite Donellson. At 10 o’clock that night the river rose and overflowed our camp. There was some hustling around to get our tents and camp equipage moved. We then pitched tents on the other side of the river.

On the 23d a squad of twenty men was detailed to go up the river on a scouting expedition. We went as far as Bell[33]wood Furnace, which was nine miles from Donellson. We saw a few rebels at a distance, fired a few shots at them and fell back. On our return to camp we killed several squirrels for our sick in the hospital. The squirrels were plentiful and gentle at this place.

We remained at this camp until March 6th, when we received marching orders. We struck tents, got on a boat, and crossed the river. While landing at this place Adjutant Barter lost his horse. It fell through the staging and broke its leg.

We marched in the direction of Fort Henry until 5 o’clock in the evening, when we went into camp for the night. The land was rolling and timbered with pine at this place.

On the 7th we marched to Fort Henry on the Tennessee river. We went into camp near the fort. This place had been taken by our forces about three weeks before. It was well fortified and was mounted with sixty heavy guns. It showed the marks of a hard-fought battle.

We lay here until the 9th. We then marched down to the landing, and got on board the steamboat, “Telegraph No. 3,” and ran up the river as far as High Piney Bluffs. Here we lashed on to another boat, which had on board the Eleventh Indiana and Eighth Missouri regiments. The two boats pulled on up the river one hundred miles and on the evening of the 12th of March, 1862, we landed at a little town called Savannah.

We marched off of the boats and formed our brigade in hollow square. Washington’s Farewell Address was read to us by A. J. Smith, who was to be the commander of our brigade. It was composed of the Eleventh, Twenty-third and Twenty-fourth Indiana and the Eighth Missouri. General Lew Wallace commanded the Twelfth Division.

We moved back on to the boats and at 10 o’clock that night we ran on up the river seven miles to Crump’s Landing. Here a[34] shot was fired by one of our gunboats as a signal for us to land. Our boat ran into the shore with such force that it knocked almost everyone down. But we were soon on our feet again. As soon as the staging reached the shore we got to land as fast as we could run off of the boat.

This was a night long to be remembered. The rain was pouring down, and it was so dark that we could not see where we were going, only by the frequent flashes of lightning.

We moved out five miles, found no enemy. We then halted for a short rest, as the mud was very bad and the water was sometimes knee deep. When daylight appeared, some were leaning against trees, some were on brush-piles and others were even laying down in the mud and water, and all were sound asleep.

Our cavalry passed us here. They went on as far as Perdy, found no enemy, and returned in the evening. We all marched back to the boats on the night of the 14th.

Our regiment was called out on picket duty. A battery was planted on the road, making a strong guard. We knew that there was a large force of rebels somewhere near us. At daylight we were relieved by the Eighth Missouri, and went back to the boat. The rain had poured down all night and we were in somewhat of a soaked condition.

Tuesday, the 18th, our division of 9,000 men moved off of the boats and marched out into the timber half a mile. Here all of the divisions went into camp. Grant, whose headquarters[35] were at Savannah, had 35,000 more troops at Pittsburgh Landing nine miles above here.

We still continued our brigade drill. April 1st, 1862, our brigade was on review. We could hear the boom of the cannon in the direction of Corinth. On that day Colonel Hovey made us a little talk.

He said, “I think that the battle has commenced on our left wing. But I wish that we could see the whites of the rebels’ eyes. Now, Twenty-fourth, all of you have mothers, sisters and sweethearts back in Indiana homes and I hope and trust that you will never let the disgraceful name of a coward go back to those dear ones who are praying each day for your honor and life to be spared.” When his speech was ended three cheers went up for Colonel A. P. Hovey.

At eleven o’clock in the evening of the 5th our bugle sounded the assembly for us to fall in line. The rain was falling as fast as I ever saw rain fall, but it was all the same, we had to march to—no one knew where. The water was from shoe-top deep to knee deep, all over the road. Still we plunged on. It was so dark that we could not see where to go and we had to keep touch with the file men.

Lieutenant Colonel Gurber’s horse fell into a hole but got out again. Captain Erwin measured his length in a ditch that was five feet deep. There was plenty of swearing and grumbling going on that night. We marched as far as Adamsville, found no enemy, and returned to camp at 7 o’clock April 6th, 1862.

The roar of cannon and rattle of musketry could plainly be heard. The battle of Shiloh had now commenced in earnest. At nine o’clock General Grant, on his way from Savannah to Shiloh, landed and gave us orders to get to the battlefield as quickly as possible. We were called into line in light marching orders.

Colonel Hovey spoke a few encouraging words to the boys, impressing upon their minds friends and honor. He told us what we were about to go into. He also said that he wanted us to go in like soldiers and men.

We started off on quick time, our regiment in the advance. The roar of the battle became plainer every minute. About 11 a. m. our advance guard came dashing back and reported us to be exactly in the rear of Bragg’s army and only a few miles distant. We got orders to about face. We double quicked three miles back and went the river road. This road curves with the river and this made the march much longer. We could hear the noise from that desperate struggle and carnage all evening.

Late in the day we passed squad after squad of our soldiers coming from the battlefield, whipped. We came up within a mile of the battle ground. Here we passed one soldier laying on his face and scared to death. Some of the officers said, “Turn him over and see if he is dead.” He then spoke and said, “Boys, you had better go back. We are all killed or captured. There ain’t enough of us left for a string guard.” When we slipped in between the lines a short time later we found that he had come near telling the truth. But we found a few brave fellows huddled down at the landing, who were not yet whipped, but Sherman’s battery and the gunboats were all that saved the little band of heroes. They also saved the day.

General Prentice was surprised on the morning of the 6th. Most of his brigade were taken as prisoners, and the General himself captured as a prisoner, and it was seven months before he was exchanged.

Sidney Johnson had been killed in the evening and this had put a damper over the rebel army.

Beauregard had been too sure of a victory. He made his brags that he could let his troops rest during the night, and in[37] the morning ride down to the river to water his horse and find the yanks all sticking up white rags. But he missed his mark.

Beauregard and Johnson had 60,000 men and they had pounced upon a force of 35,000, many of whom had never been in such a fight. There were not more than 7,000 in the ranks of the Union forces at the closing charge on the evening of the first day’s fight at Shiloh.

Between sundown and dark our division, under Wallace, slipped in between the lines of the rebel and union forces, while our gunboats constantly threw shells over into the rebel ranks. All during the night, under this same protection, Nelson’s forces were being brought across the river, and General Buell’s army was coming up the river from Savannah, as reinforcements. These two forces numbered 35,000.

The union force outnumbered that of the confederates then by 17,000.

That night the rebels drew their lines back about one and a half miles. Our division laid down in line of battle and remained in that position all night, with the rain pouring down all the time. The groans of the dying and wounded were terrible to hear, yet many of us slept soundly until we were awakened to fall in line.

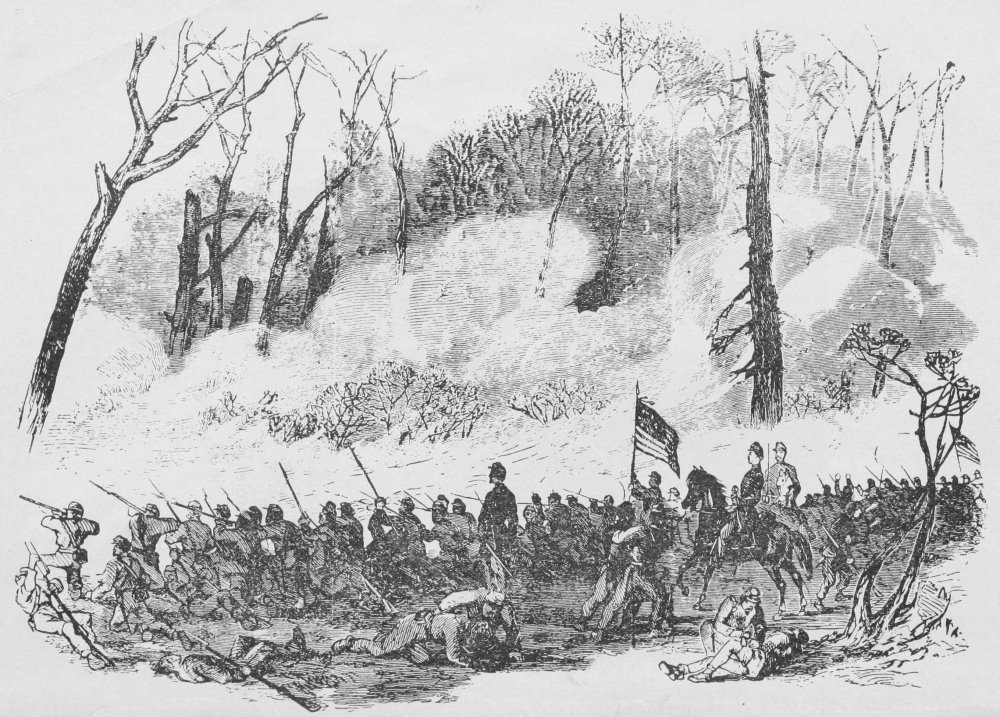

At 4 o’clock on the morning of the 7th, drenched in rain and very hungry, Wallace’s division plunged into the fight on the right of the army of the Tennessee and opened the battle of the second day’s fight.

We moved out one mile and formed our line of battle. Our brigade supported the Ninth Indiana battery. We were charged by a regiment of rebel cavalry. They were repulsed in a short time and went back faster than they came.

Companies A and B were placed on the skirmish line with Birds’ sharpshooters. We charged on two big twelve-pound batteries which were raining shot and shell into our lines, causing[39] great destruction. We got within forty yards of their guns and silenced them for a few minutes, but they then double shotted with canister and drove us back. We soon met our main column coming up into the charge.

Our two companies got lost from our regiment and fell in line with a Kentucky regiment. We supported the center of our army, while it was driving the enemy back on the flanks in every charge. The center which we supported was masked with three firing lines. The fighting was awful.

The batteries were pushed up by hand and as many as two files of wounded were going back to the rear for an hour. The earth shook as if with an earthquake. It seemed as if nothing could live in the hell of fire. One could taste the sulphur and the shell and bullets could have been stirred with a stick. The atmosphere was blue with lead.

The rebels were drawing off on the flanks and were holding their center with all their strength to cover their retreat. At 3 p. m. General Bragg, seeing that he had come to stay, withdrew his army and skedaddled in the direction of Corinth. He was whipped and had left 8,000 men on the field dead and dying. Among them was Sidney Johnson, one of the South’s best generals.

Our cavalry followed up the retreat a few miles, picked up a few prisoners and was called back.

The union loss at this place was 10,000. The loss in the Twenty-fourth Indiana was thirty-two killed and wounded. We lost three officers who were as good and brave as any who ever drew saber. Lieutenant Colonel Gruber was struck in the breast with a spent cannon ball while in front of the regiment on the charge. Lieutenant Southwick of Company B, had his jaw shot off with grape shot. Captain McGuffin, of Company I, was shot through the breast.

A report From History of the Battle of Shiloh.

Grant, with his victorious army, moved up the Tennessee river to Shiloh. Here, April the 6th, 1862, he was attacked by General A. S. Johnson and driven back.

The night after the battle General Buell brought a large force of Union troops. The Union troops outnumbered the Confederates now by seventeen thousand. The next day Grant gained his second great victory.

He said in his report, “I am indebted to General Sherman for the success of the battle.”

Twenty-five thousand men, dead and wounded, lay on the field after the battle.

When the battle was over we lay down on the battlefield and remained there all night without anything to eat. A steady rain was falling and had been for several days. The 8th and 9th the wounded were cared for and the dead buried. This put an end to the bloody battle of Shiloh.

The Battle of Shiloh Hill in verse:

We lay here on the field five days without shelter or rations, except what the other regiments, stationed here gave to us. On the 13th a detail was sent after our tents and camp equipage. It was still raining, but we had to move out and do something, as we could already hear the “graybacks” crawling in the leaves.

On the 16th we moved out to the front and went into a camp in a nice meadow. Here we had four hours’ brigade drill each day.

General Halleck soon took charge of this army and commenced to advance on Corinth, where Bragg had a force of 60,000 troops, well fortified. On the 20th a small squad of rebel cavalry ran into our picket line. Our lines were reinforced and we had to stand in line of battle from 4 o’clock until daylight.

Our fatigue guard duty was now heavy. Almost all of our time was employed. The weather was getting fine. Leaves were putting forth and the aroma of the flowers filled the air. The birds warbled their sweet songs and all Nature seemed to say, “How foolish for human butchers to slaughter one another.”

On the 26th we marched to a place called Hamburgh, seven miles away. We found no enemy and returned to camp on the 27th of April.

May 2d, 1862, we marched out near Perdy, a distance of about ten miles. We halted, went into camp, and sent a force of cavalry on to burn the railroad bridge. The cavalry returned at 4 o’clock in the evening of the 3d and reported that there was a heavy guard at the bridge, and they had not fired a shot at the enemy. General Wallace sent them back with orders to burn that bridge at all hazards, or he would dismount them and send the infantry on their mounts. That trip they burned the bridge, captured some prisoners, and ran the train into the bridge.

We could hear the distant boom of our gunboats and heavy artillery that were advancing on Corinth. We started back to camp. It had rained and we had a very muddy, hard march on the return.

On May 8th we took up our line of march to the front. We moved out in the direction of Corinth, Mississippi, and went into camp on Gravel Ridge.

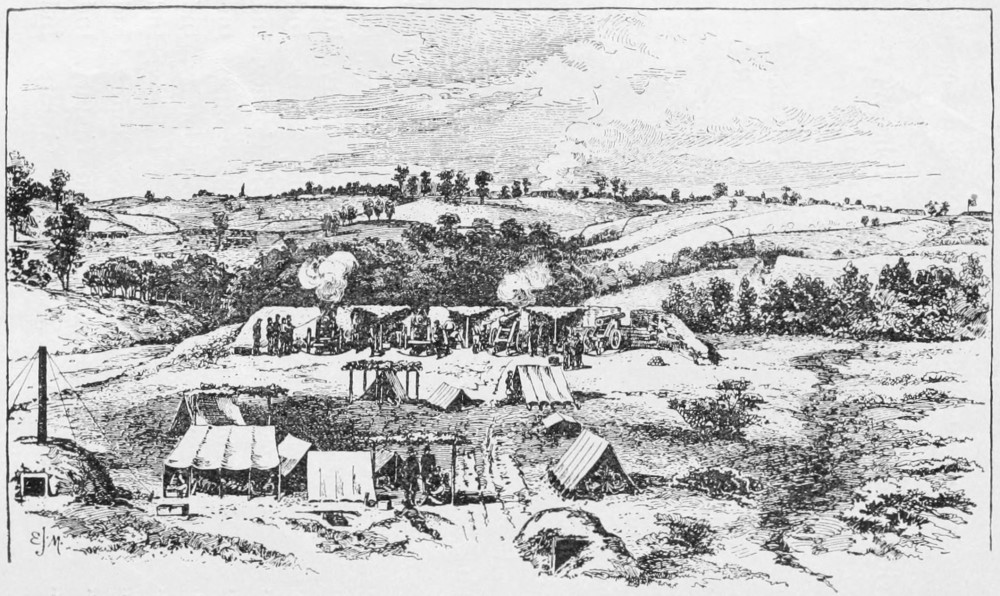

Our division was held in reserve four miles in the rear of our main army. We had an army of 80,000 collected here. The Union force was trying to dig a canal to get the gunboats near enough for action. We had Corinth almost surrounded and the heavy guns kept up a constant bombardment.

We had battalion drill two hours each day. We were drilled by Spicely, who was major at that time. About this time we drew four months’ pay, which amounted to fifty-two dollars.

Our picket duty was extremely heavy, as the rebel cavalry made frequent visits to our lines. There was heavy skirmishing in the advance at all times. We were closing in too near to suit old Beauregard and Bragg.

On the 26th of May Bragg’s army to a man evacuated Cor[43]inth. It was no siege—merely a draw battle. That army went in the direction of Richmond. Most of them went by railroad. This was the end of the first battle of Corinth.

June 2d we received marching orders, and on the morning of the 3d we marched in the direction of Memphis, Tennessee. The roads were dry and dusty, making our march very disagreeable. We passed through Union Town on the 8th. Here was the first place on this march where we had seen the Stars and Stripes waved by citizens, and you bet the boys gave them three cheers and a tiger.

We marched on through Bolivar and on the night of the 13th we went into camp near Memphis. After a march of a hundred miles, we were all tired and ready for a little rest, but our rest was yet to come, for at 1 a. m. o’clock the next morning the bugle sounded the assembly. We fell in line and marched to the city.

but on our weary boys tramped into Memphis. We took refuge under sheds, porches or any place else to get shelter from the rain. The next morning we marched down to the river bank, pitched tents and went into camp.

On the morning of the 16th we were ordered out seven miles back of the town on a scout. We found no enemy and marched back to camp. We had a heavy provost guard at this place to keep the boys from running around over town.

We received marching orders on the morning of the 17th. We embarked on a steamer, and went as far as Helena, Arkansas. Here we got orders to reinforce General Curtis who was in Missouri with a small force, at that time. We got on board a[44] boat and ran down the river, sixty miles below Helena. Here we turned our course up White River as far as Aberdeen, a small town on the bank of the river.

We could not hear of the whereabouts of Curtis’ army, and on the 4th of July, we remained all day at Crockett’s Bluff. On the 6th, six companies of our regiment under command of Colonel W. T. Spicely, marched out about six miles to Grand Prairie. Here we ran into a force of the 2nd Texas cavalry, about four hundred in number. Only four of our companies were in line. These companies numbered about 180. The rebels charged up within thirty steps of us. They lay over on the opposite sides of their horses and fired at us with double barrel shotguns, from under their horses’ necks.

They were repulsed, tried the second charge, and were driven off in disorder.

Colonel Fitch’s command was two miles in our rear but they did not get up in time for the fight. Late in the evening we returned to the boats and Colonel Fitch treated us to the beer. On the morning of the 7th all the troops marched to Grand Prairie again. There was some skirmishing with the rebel pickets but they made no stand. We had battalion drill at 10 o’clock that night.

July 7th, we marched as far as Clarenden, a distance of ten miles. We crossed the river and went into camp in the town. We remained here until the evening of the 9th. We got a dispatch that Curtis’ army had made its way through to Helena.

We embarked on boats and at night ran back down the river. Our boat ran on to a snag and almost sank, but we got it off and repaired after quite a lot of work. On the 14th we landed at Helena again. We found General Curtis’ command here. They had had a hard time marching from Missouri down through Arkansas.

We stayed here drilling and doing camp duty until August 9th. We then marched to Clarenden on White River, sixty miles distant, but found no enemy. The weather was hot and the roads dusty, making a fearful march. But nevertheless, we found plenty to eat on the way, such as pork, chicken, honey and other good things. On the 19th we got back to Helena, covered with sweat and dust. We looked more like the black brigade than white folks.

August 27th, we got on board a boat and went thirty miles up the St. Francis river, on a scout. We landed the boat, got off, and marched through the canebrake seven miles. We found no enemy and returned to our boat the “Hamilton Belle.” When we got on board we found her loaded to the guard with cattle, cotton, sugar, pork, and all kinds of forage picked up by the boys.

We started back to Helena, and landed a short distance from our camp at 2 o’clock in the morning of the 28th. We had quite[46] a time getting our private forage ashore as the general, E. O. C. Ord, put a guard at the staging and would not let the boys take anything with them off of the boat. What they didn’t get off they rolled into the river.

September 4th, 1862, several companies of our regiment went on a scout up the river after Bushwhackers. We went up to Chalk Bluffs, below Memphis. We found no enemy and started back to Helena. We had not gone far when a volley was fired into us by a force of mounted rebels. Our boat in command of Lieutenant Colonel Barter, landed. He ordered us off and out after them. After a run of three miles we decided that we could not run down mounted rebels and make them fight.

We marched back to the boat and continued our return to Helena. We landed there the evening of the 6th.

On the 16th, a detail got on a boat and went thirty miles up the river, after a load of wood. On the 23rd, we had a sham battle. We had quite a time at this and we then settled down to camp life. We had brigade drill four hours each day from then until October 16th when we got orders to go up White River.

We embarked on boats and went down to the mouth of the river, but the water was so shallow that we could not get in at the mouth. We then returned to Helena.

Our drill and picket duty was very heavy, as we had pickets on the opposite side of the river. We were in all kinds of employment, some peddling, some fishing, and some playing games. We had a general routine of camp life.

November 20th, some of the 11th Indiana boys, while out foraging were fired into by the rebels. One man was killed.

On the morning of the 28th, we got marching orders. We boarded a boat and went to Delta, nine miles below. We got[47] off of the boat and marched out forty miles east, to the crossroads. We went into camp in a bottom.

December 3rd, General Washburn with part of the command marched to the railroad. Here they had a sharp skirmish with the enemy, losing one piece of the 1st Indiana cavalry’s artillery. This was a draw battle. We got plenty of pork and sweet potatoes on this march.

On the 5th we marched back to Coldwater. The next morning we began our march at 4 o’clock. Sunday, the 7th, we marched three hours before day. Half of the boys didn’t get their breakfasts that day. We reached the river and got on the boats. We landed at Helena at 10 p. m.

On the 9th of December, General Gorman took command of the post, and we had grand review. On the 11th we were reviewed by Generals Gorman and Steel. About the 15th, some heavy rains fell, causing the sloughs to rise, so that we had to haul the picket guards to their posts in wagons.

On the 21st, General Sherman, with his army and a fleet of gunboats, passed Helena. This army was on an expedition against Vicksburg.

On the 22nd, Lieutenant Colonel Barter was appointed Provost-marshal, and the boys of Company B of our regiment were guards.

About the 25th, General Grant’s communications were cut off while he was on an expedition against the rebels at Meridian. This caused his failure to form a junction with Sherman at Vicksburg. Generals Sherman and Smith with their forces charged Haines’ Bluffs. They were repulsed with heavy loss.

Sherman was now reinforced by McClearnand. They went up the Arkansas River and took the Arkansas Post, with six or seven thousand prisoners and some heavy guns. Sherman captured more prisoners at this place than he had lost at Vicksburg.

On the morning of January 11th, all of our troops at Helena under Gorman, except one cavalry regiment, got on boats and went down to the mouth of White River. We went up the river to St. Charles which place the rebels had evacuated. On the 15th of January, 1863, a seven-inch snow fell. The canebrakes and timber bent under their heavy loads.

The heavy rains had overflowed the river and it was all over the bottom land. This together with the snow made a very gloomy morning. That night, the pickets had been sent out with orders not to kindle any fires. Some of them were angry and set fire to some buildings, thus causing some excitement in camp. The pickets were called in and we got on the boat. We went up the river to Clarendon, and on the evening of the 16th, we landed at Duvall’s Bluff. The rebels had just evacuated this place. Our cavalry moved out after them and picked up a few prisoners.

The rebels left two sixty-four pound guns in our possession. We loaded these on to the boats. On the morning of the 17th, Colonel Spicely, in command of the 24th and three gunboats, went to Desarc. This is a beautiful little town. It is about as far up White River as navigation is carried on.

We found many sick and wounded rebels here. Our officers paroled them. There was also a great deal of small arms and ammunition here which we took.

January 19th, all of the command moved to St. Charles. At night several houses were set on fire, making quite an illumination. On the 21st we went down near Helena, but had to tie up on account of the fog. On the morning of the 22nd, after a distance of 540 miles had been traveled, we landed at Helena again.

The weather was cold and disagreeable, and we began building winter quarters. There were to be sixteen men to a log cabin.

We remained here until the 18th of February. Our camp[49] was then overflowed and we moved back from the river. We went into camp on higher camp ground.

The 19th we embarked on a boat and went down the river as far as Moon Lake. Here the levee had been blown up, and every foot of the lowland to Yazoo City, had been flooded. In early days this place had been called Yazoo Pass, and boats had run along here. We crossed the lake and marched five miles. We went into camp for the night.

On the 20th, we drew some cornmeal. This was quite a treat as we were tired of hardtack. We found a mill, set her to going, and soon had enough meal ground for a good corn cake. Some baked their cake in half canteens, some on boards, and others rolled the dough on a stick and held it near the fire until it baked.

A cold rain had set in making a very muddy and disagreeable time, but we had to pull the heavy trees out of the pass, which the rebels had felled to keep our boats from going through. We fastened two-inch cables around the butts of the trees, and pulled them out, tops and all. Several cables broke, throwing the boys twenty feet each way. We finished cleaning out the pass on the second evening. We were wet and muddy all over. The officers took pity on us and issued a thimbleful of commissary whiskey to each man. Some of the boys paid twenty-five cents a thimbleful for enough whiskey to make a good drink.

On the evening of the 22nd we got on the boat and went down to the mouth of the pass. We found no more obstructions. When we got to Coldwater River, our gunboat threw shells into the woods on each side. We ran down this stream twenty-five miles and tied up for the night. We could see the signs of a great many rebel boats which had peeled the bark off of the trees near the shore. All of this country was flooded.

On the morning of the 24th, our task completed, we turned[50] the bow of the boat up stream. On our return, we ran up near Moon Lake. When night set in it was so foggy that we had to tie up for the night. The next morning we decked our boat with holly and other evergreens and set out on our journey. We ran into Moon Lake and here met General Quinby’s division on their way to Fort Greenwood.

We returned to Helena. General Quinby moved on down to the fort and found that country all under water. At night he planted two guns on a small knoll near the fort. The next morning the gunboats opened fire on the fort. The rebels threw a shell into the port of the Benton, killing seven gunners. The union troops then had to draw off, as they could not get to the fort. They left the two guns which had been planted there.

They came back to Helena after a hard struggle to get through to Yazoo City. All of their plans had failed.

General Prentice was now in charge of the post at Helena. On the 28th of February, he issued an order for all citizens to be sent out of our lines who would not take the oath of allegiance to our government.

The river rose, overflowing our camp, and we had to move it.

March 14th, Company B of our regiment was relieved from provost duty, and they returned to the regiment. Nothing of importance occurred until the 26th of March, at which time we received two months’ pay.

In the morning of April 6, 1863, we were called into line. Our brigade marched into the fort and was addressed by Adjutant General Thomas. He spoke in regard to arming the negroes, as the Emancipation Act had already been passed. He had come direct from Washington, D. C., with full authority to arm and equip the colored troops. He advocated that it would be much better to put the negroes up for a target to be shot at than for us to risk all of the danger ourselves.

This proclamation caused quite an excitement throughout the army. Many of the boys deserted and went back home, but they were afterwards pardoned, and came back to their regiments. About this time we received two months’ pay.

April 9th, we received marching orders which were read to us at dress parade. On the evening of the 10th we struck tents, marched on to the boats, and went down the river four miles. Here we joined General Quinby’s division. General Hovey was now in command of our division. On the morning of the 12th, our squadron moved on down the river. We went past Napoleon at 4 o’clock in the afternoon. On the morning of the 13th, we ran past Lake Providence, Louisiana.

We landed at Millikin’s Bend at 12 o’clock at noon, this being about 210 miles below Helena. On the morning of the 14th we went up the river two miles, got off of the boat, and went into camp.

April 15th, we loaded all of our baggage on a barge and prepared for a march. This country was low and swampy, and a great many of our boys had died from malaria and other diseases. Many of them were buried on the levee. Our troops had lain here since the charge at Chickasaw Landing.

On the morning of the 16th we started to march around Vicksburg. We went into camp at night near Richmond, a small town in Madison Parish, Louisiana. The next morning we marched twelve miles and went into camp on Dawson’s Plantation. We remained at this place three days. Our teams went back for rations.

About this time General Grant sent his Yankee gunboat past the blockade at night. It fooled the rebel gunners and each fired a shot at the supposed monster. As the nights were very dark,[53] we could see the flashes of the guns and hear the boom of the heavy guns which were planted on the river bluff for seven miles in length.

At this place we had roll call seven times each day in order to keep the boys in camp. On the 19th, our cavalry had a small engagement. After they had taken a few prisoners the rebels fell back.

On the 21st, we marched to Fisk’s Plantation, a distance of about thirteen miles. We went into camp near the bayou. Grant had been trying to open up this bayou for several months, so that he might get the gunboats around Vicksburg. It rained all that day making it very disagreeable.

There was heavy cannonading at night, as our gunboats and transports were running the blockade. We must have been twenty-five miles away but the roar and flashes could plainly be heard and seen.

We lay here several days while our pioneers were constructing pontoon bridges across the bayou. Here our siege guns were brought up. They were drawn by several yoke of cattle, as it was too muddy in that black sticky soil for horses or mules to get through, with big loads.

On the 27th we resumed our march. While crossing the bridge one of our heavy guns fell over the side of the bridge, and went down into thirty feet of water, dragging the teams with it. It began raining and after marching nine miles through the rain and mud which was knee deep, we came to the banks of the Mississippi River.

All of our fleet which had run the blockade at Vicksburg, lay at this place, which we named Perkins’ Landing.

On the 28th, General A. P. Hovey’s division embarked on boats and barges and went fifteen miles to Hard Times Landing, which is five miles above Grand Gulf.

On the morning of the 29th, all of us marched on to boats with barges lashed on either side, which were filled with troops ready for the charge. Our squadron of ironclads, seven in number, moved in line on down toward the rebel forts. It was a grand sight to behold those great ironclad monsters gliding down against this mighty fortress at Grand Gulf, with its large guns, to receive tons of iron hail against their iron sides.

Everything was as still as death when we neared the fort. Many were holding their breaths and listening for the terrible fray to begin. On the boats went, the Benton in advance. When she got opposite the fort, she circled round until within 150 yards of it. She then opened up with a broadside of six heavy one hundred pounders one after the other. Each boat followed in succession. Scarcely had our guns opened fire when the enemy replied with their heavy 284 pound guns.

The fort became a mass of fire and smoke. The Tuscumba in the same manner as the Benton, poured in her broadside. Next came the Baron, DeKalb, the Lafayette, the Carondalet and so on.

The fort seemed to be silenced and then it was that our brigade on a boat and two barges, moved on down with orders to charge that American Gibraltar. We were in good spirits, for we thought that no human life could exist in that flame of hell and destruction, which rained over the rebels for two long hours. All was silent, but we had run down but a short distance when a white cloud of smoke belched out of the fort like a volcano, and the heavy shot and shell once more poured out from that crater.

One of the largest shots struck not over twenty yards from our bow. It was not many seconds before our pilot had the bows of our boats turned in the opposite direction.

We were about two miles from the fort when the battle was[55] renewed, part of our gunboats running close to the fort and using grape shot and cannister. The old Lafayette lay at a distance of three miles up the gulf, using her big stern gun and dropping shell directly into the fort.

The hog chains were cut off of the Tuscumba, and she, put out of business, dropped down below the fort.

After four hours of hard fighting, our boats drew off to cool down and rest a while. It must have been terrible for the boys who were shut up in those iron monsters.

Our force landed and a detail of volunteers was called to stay on the boats while the blockade was being run. We marched round six miles on the west side of the river. At 8 o’clock we were on the river bank, five miles below Grand Gulf. At nine o’clock our entire fleet ran the blockade. This sight will be remembered by many persons as long as they live. We could see tongues of fire pouring forth from the mouths of those mighty monsters. The sound on the still night air was heard many miles away. The earth trembled as far away as where we were looking on. Our boats got through but they were riddled up somewhat badly.

Our loss was twelve killed and wounded. The rebel loss was twenty-six. Among their wounded was a brigadier general. We lost six battery horses on the transports, while they were running the blockade.

On the morning of the 30th we crossed the river. Our regiment crossed on the old ironclad Benton. The marks of the shot on her iron plates were terrible. Great pieces of shell had been forced under her iron plates, and they were blue all over where the minnie balls had struck and glanced off.

After we had crossed we drew a small amount of hardtack and a little piece of bacon. At four o’clock we started on a march in the direction of Port Gibson, which is seven miles back[56] of Grand Gulf. We marched all night over a very rough, broken country. At 2 o’clock on the morning of the 1st of May, we ran into the rebel army. We were halted from our tiresome march by the terrific sound and the crashing shell of a battery, which broke the still morning air with its echo over hill and valley for many miles and warned even the little birds of that desperate day which was to come and cause so many homes to mourn the loss of some dear friend.

Hovey’s division being in front, our regiment moved down and stacked our arms in line of battle. We were not farther than 100 yards from a concealed line of rebels. They lay in a canebrake. Everything was as still as death and this was the darkest part of the night, the hour just before day. Our regiment was ordered to move to the right and form the right wing of our line of battle so that the troops in the rear might come up and form in line. But before our lines were formed, that ravine and canebrake became a solid sheet of fire, caused by the rebel batteries and small arms. Daylight was now beginning to break and we could see that the shells were playing havoc with our troops on the hill, that were forcing their way up to the front to form our lines.

We had stacked our guns and the boys were trying to make some coffee, but the battery in front seeing that the hungry boys needed some heat to make their coffee boil quickly, rolled in a few shells and blew all of the fire out. Some of the boys swearing, declared that it had come from our own guns, for the shell came directly from the place where we had stacked our arms that morning.

The fight was now on in earnest, and there was no time for arguing about the matter. We now piled our knapsacks and prepared for the charge.

General Osterhos had charged in front, and our regiment[57] charged down across a large ravine, which was grown up with cane, making it almost impassable. The rattle of shot and shell striking the cane and the whoops and yells of the charging regiments made a terrible noise.

We moved across and supported the 8th Indiana, which was commanded by General Benton. The rebels gave way on all parts of their lines and fell back. We then moved up and supported a battery in the edge of a big plantation. They were shelling the rebels on the retreat. Some old houses were near by and the rebel batteries were knocking the chinking and splinters in all directions.

We followed up the retreat five miles. We found everything imaginable scattered along the road. The rebels halted and formed their lines in the timber near Port Gibson. We moved up within a mile of their lines, halted, and stacked our arms, to take a rest.

At two o’clock, the rebels were reinforced by General Tracy and Green, who had fresh forces, and they were also good fighters. We could see them coming down on us in as nice a line as was ever seen in any army. We then had to get busy, and in a hurry too. We advanced to meet the enemy. Our regiment stopped at a ditch. The 47th Indiana and the 19th Kentucky stayed with us.

When the rebel line got within forty yards of us their men fell to the ground and remained there one and one-fourth hours, before we repulsed them. We averaged fifty-eight rounds of cartridges to the man before the rebels withdrew. After that we never grumbled about carrying sixty rounds of cartridges.

After General Tracy and many others had been slain, the rebels fell back demoralized. Very many of their men had been slain and wounded. Our regiment had only thirty-four killed[58] and wounded, as we were protected by the ditch, and did not suffer like other regiments.

The fighting along the line was kept up until five o’clock in the evening when the rebels fell back, some by the way of Grand Gulf and the others in the direction of Vicksburg. At two o’clock on the morning of the 2nd of May we were awakened by the jar and report of the exploding magazines which were blown up at Grand Gulf, when the rebels evacuated that strong fortress. We could see their signals going up all night, and thought that the rebels meant to concentrate their forces and fight a pitched battle with us, on the next day, but they saw that we had come to stay and decided that it would be better for them to take all of their men to Vicksburg.

Now it could plainly be seen that nothing could hold the blockade of the Mississippi against our mighty force of ironclads and the army which had undertaken to open it up.

Our loss at Port Gibson was 500 killed and wounded. The rebel loss was about 600 killed and wounded and we also took 700 of their men as prisoners. The divisions that were engaged at this place were A. P. Hovey’s, Osterhos’, and Carr’s. Logan’s division came up just at dark, and Quinby’s division did not get into the fight at all.

May 2, 1863, we moved into Port Gibson. Here we had to wait until a pontoon bridge could be constructed over Bayou Pierre, as the rebels had burned the bridges, while on their retreat.

Our boys found many valuables, such as watches, jewelry, silverware, and some gold and silver coin at this place. We also found plenty of good bacon which was buried in hogsheads and sodded over. This came in good play as our rations were getting slim. The citizens all seemed to be in mourning. Many of[59] them had their property burned on the supposition that they had fought us the day before.

On the morning of the 3rd, our regiment crossed the bayou, and marched out six miles in the direction of Grand Gulf on a scout. We found plenty of bacon and other articles of food, which the rebels had concealed in the woods, but they were not sharp enough to hide anything from a yankee.

At two o’clock we started back, but when we came to the Jackson road we learned that our entire army had moved on. We then followed up as a rear guard.

We marched twelve miles and went into camp near Rocky Springs. Our army had nothing to eat and we were cut off from our base of supplies. Thus we had to forage off of the country. We foraged corn and ran one or two mills, and this furnished a half pint of meal to the man. Some made bread and cooked it on coals and others rolled the dough on sticks and baked it, and still others mixed water and meal together, making mush without any salt. At least we had a time to get something to satisfy our gnawing stomachs.

We lay here until the evening of the 6th when we moved up eight miles. We went into camp and drew one cracker to the man, for supper, but we had plenty of water to wash it down with.

On the morning of the 7th we moved up three miles and formed on the line of battle which was being established. Our cavalry had a sharp skirmish and took twelve prisoners. We had grand review by General Grant.

Sherman’s corps arrived on the 10th. We marched ten miles and went into camp. Sherman’s corps passed us late in the evening and went into camp two miles in advance of us. This was near the enemy’s line of battle and we looked for a heavy battle at any moment.

On the morning of the 12th we marched on past Sherman’s division. After a march of five miles we came up with our cavalry command, which was engaged in a sharp little fight with the rebel advance. We drove them back to the main Vicksburg army near Edward’s Depot.

We crossed Baker’s Creek and went into the camp for the night. We were so near the rebels that we could hear them talk at night, and our teamsters and their cavalry got corn at the same cribs, between our lines. While our teamster of company A, Timothy Riggle, was in the crib filling his sack, a squad of rebel cavalry came to the door.

One of the rebels looked in and called out, “Boys, heah is a d—— yank in heah stealing ouah cohn.” Then this to the yankee, “Get out of heah.”

Our teamster hardly knew how to answer, but he replied, “Gentlemen, please give me time to get a few more ears. My mules are nearly starved.”

When they heard him call them gentlemen they gave him a little time. I suppose that they had never been called gentlemen before. But the teamster didn’t take time to fill his sack. He was glad to change places with the rebs, and feed his mules on half rations. When he came into camp with his hair standing on end, and reported his escape from prison, the Captain said to him, “Bully for you, Tim.”

That night Sherman, with his corps passed to our rear, and went with all speed toward Raymond. On the morning of the 13th we heard the batteries of Sherman’s force open up on the rebel army at Raymond.

During the night the rebels had concentrated a large force with the expectation of a general fight the next morning. But at daybreak when they heard the noise of Sherman’s batteries at Raymond, they came down on us like demons. The bullets flew[61] thick and fast but the most of them went too high as we were under the hill.

As we had only a small detachment against the main rebel army, we were ordered to fall in line and pull out on double quick time.

I will relate a little circumstance which took place while we were in this critical position. In forming our lines we were ordered to left wheel into line. One of our old comrades by the name of John Lochner, who was a very clumsy Dutchman, slipped on a pile of rails and peeled all of the skin off of half of his nose. He was standing there cursing in Dutch and the Captain seeing him with the blood running down his face, yelled out, “Lochner, if you are shot, go to the ambulance.”

“Shoot, hell Ciptain, shoot mit a rail in de nose.” he replied. But he stayed in his place in the ranks anyway.

We crossed the creek and were soon out of the range of the rebels’ bullets. A very heavy rain set in making a hard muddy march. Seeing the rebels did not follow us, we crossed over Baker’s Creek on a bridge and then set the bridge on fire. We went into camp in the bottom.

That night we tore down some cotton pens and each fellow had a good, soft, cotton bed. But just as a person thinks that he is getting some great pleasure for himself, death and destruction come along and cut off his happiness. About 10 o’clock that night, we were almost washed out of that camp by a flood. We waded to the hills in water that was sometimes waist deep.

On the 14th, we marched through Raymond. Here we passed over the battleground. It bore the marks of a hard fought battle. In the fight Sherman had taken several prisoners, but he had lost 500 men, killed and wounded. He had gone on to Jackson, the capital of Mississippi.