The Project Gutenberg eBook of Memorials of Old Dorset, by Various

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere in the United States and

most other parts of the world at no cost and with almost no restrictions

whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or re-use it under the terms

of the Project Gutenberg License included with this eBook or online

at

www.gutenberg.org. If you

are not located in the United States, you will have to check the laws of the

country where you are located before using this eBook.

Title: Memorials of Old Dorset

Author: Various

Editors: Thomas Perkins

Herbert Pentin

Release Date: May 19, 2022 [eBook #68128]

Language: English

Produced by: Tim Lindell, Les Galloway and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive/Canadian Libraries)

*** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK MEMORIALS OF OLD DORSET ***

Transcriber’s Notes

Obvious typographical errors have been silently corrected. Variations

in hyphenation and accents have been standardised but all other

spelling and punctuation remains unchanged.

The repetition of the title immediately before the title page has been

removed.

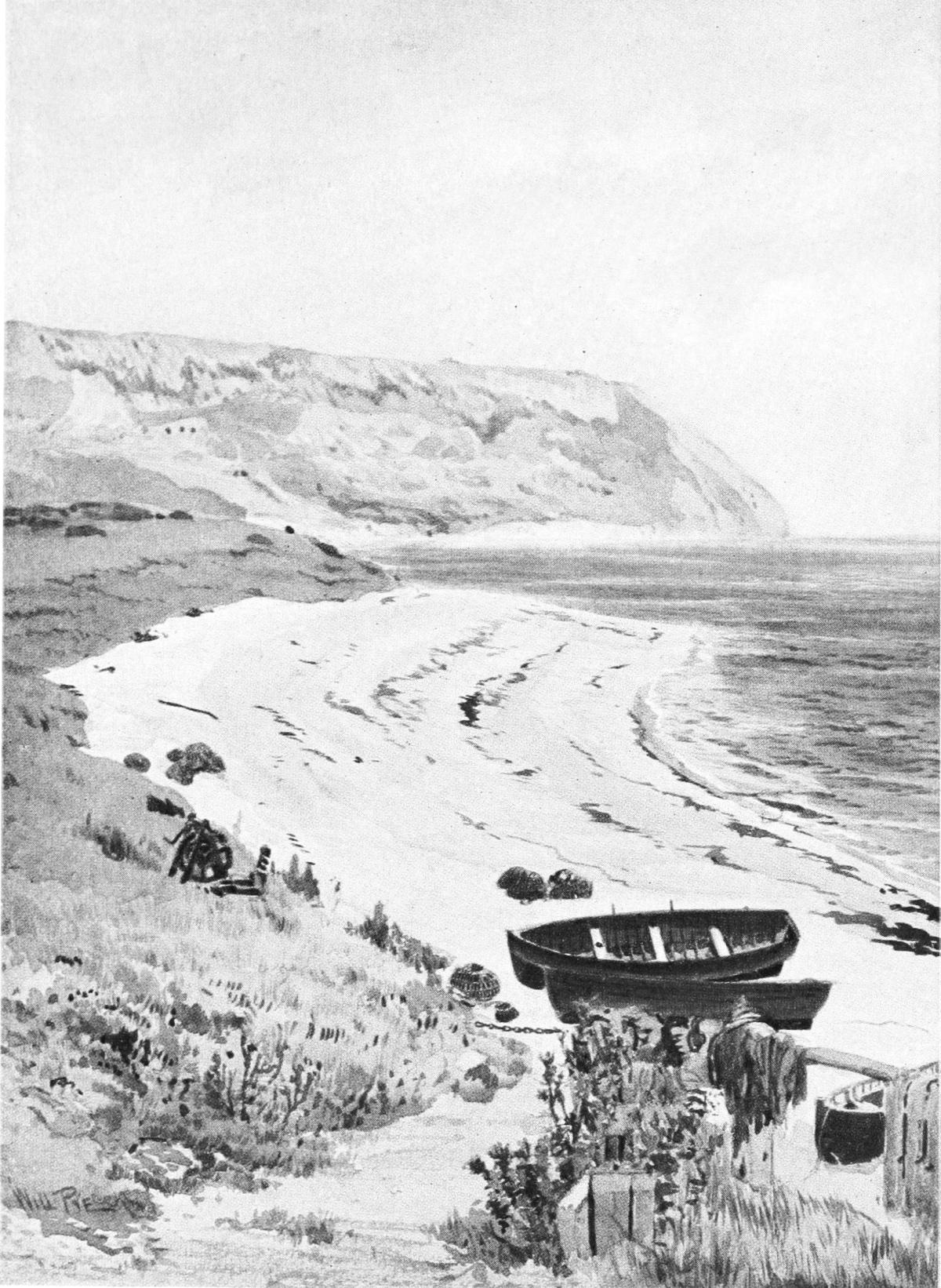

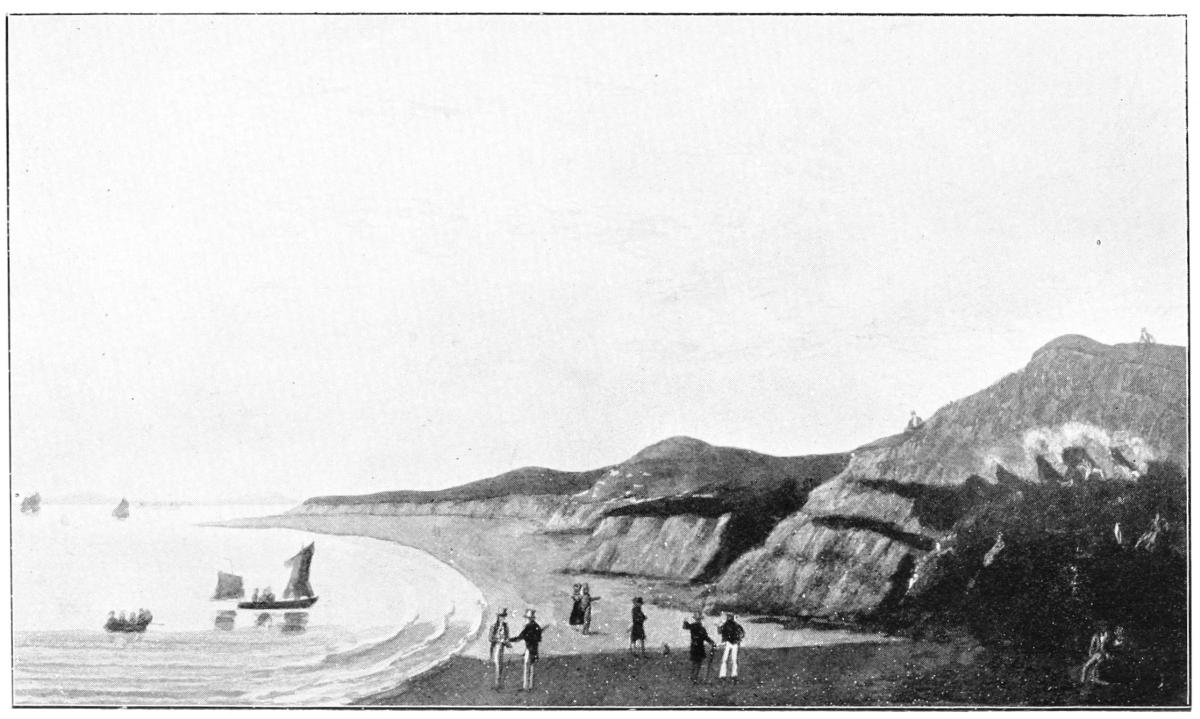

Ringstead and Holworth.

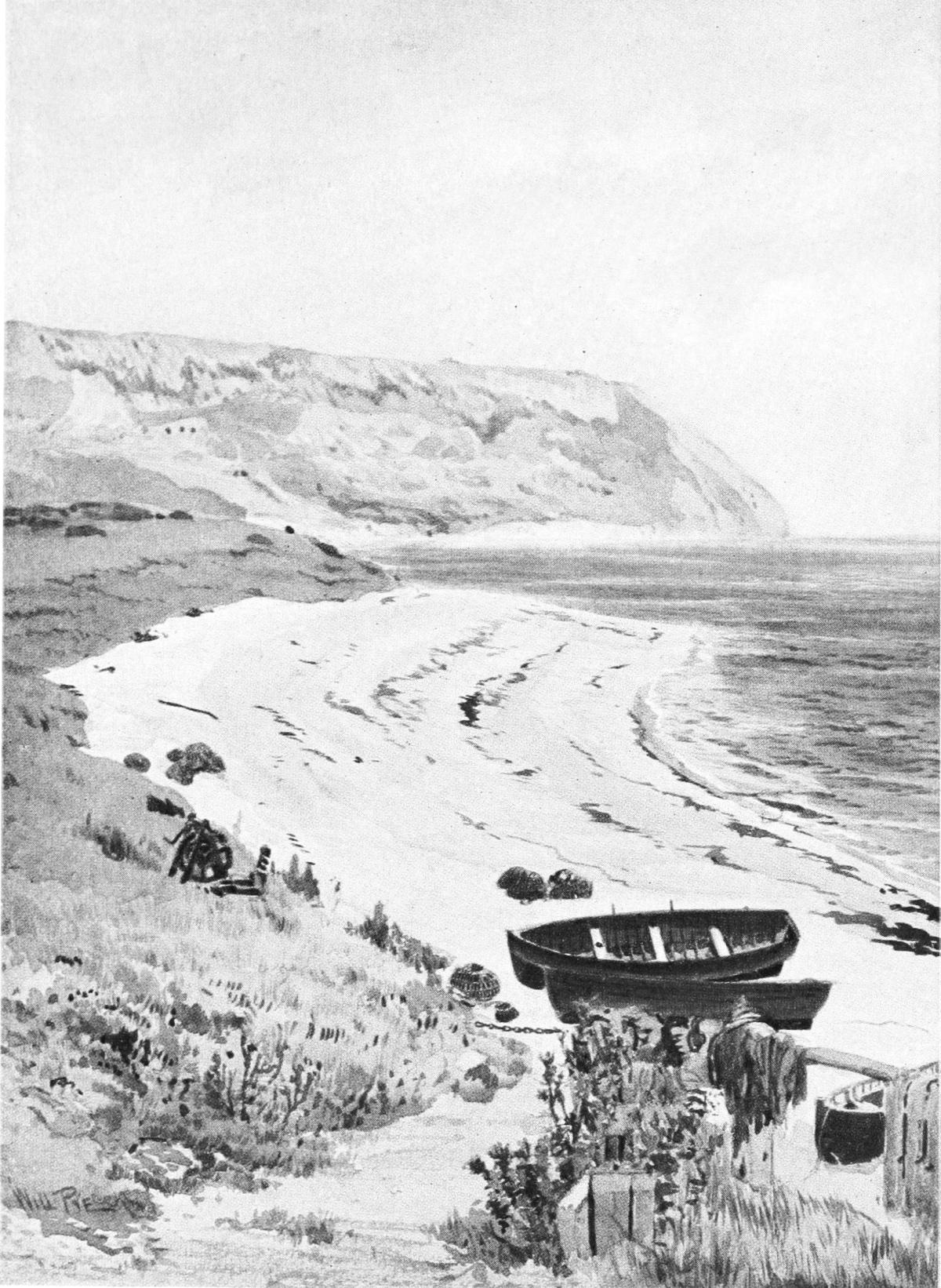

“Where one may walk along the undulating

downs that skirt the Channel, held in place

by parapets of cliff that break down straight

into the sea; where one may walk mile after

mile on natural lawn and not meet a soul—just

one’s self, the birds, the glorious scenery,

and God.” (See page 109.)

From a water-colour sketch by Mr. William Pye.

Memorials of the Counties of England

General Editor: Rev. P. H. Ditchfield, M.A., F.S.A.

MEMORIALS

OF OLD DORSET

EDITED BY

THOMAS PERKINS, M.A.

Late Rector of Turnworth, Dorset

Author of

“Wimborne Minster and Christchurch Priory”

“Bath and Malmesbury Abbeys” “Romsey Abbey” &c.

AND

HERBERT PENTIN, M.A.

Vicar of Milton Abbey, Dorset

Vice-President, Hon. Secretary, and Editor

of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club

With many Illustrations

LONDON

BEMROSE & SONS LIMITED, 4 SNOW HILL, E.C.

AND DERBY

1907

[All Rights Reserved]

TO

THE RIGHT HONOURABLE

LORD EUSTACE CECIL, F.R.G.S.

PAST PRESIDENT OF THE DORSET NATURAL

HISTORY AND ANTIQUARIAN FIELD CLUB

THIS BOOK IS DEDICATED

BY HIS LORDSHIP’S

KIND

PERMISSION

PREFACE

he editing of this Dorset volume was originally

undertaken by the Rev. Thomas Perkins, the

scholarly Rector of Turnworth. But he, having

formulated its plan and written four papers therefor,

besides gathering material for most of the other chapters,

was laid aside by a very painful illness, which culminated

in his unexpected death. This is a great loss to his many

friends, to the present volume, and to the county of

Dorset as a whole; for Mr. Perkins knew the county as

few men know it, his literary ability was of no mean

order, and his kindness to all with whom he was brought

in contact was proverbial.

After the death of Mr. Perkins, the editing of the

work was entrusted to the Rev. Herbert Pentin,

Vicar of Milton Abbey, whose knowledge of the

county and literary experience as Editor of the Dorset

Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club enabled him

to gather up the threads where his friend Mr. Perkins

had been compelled to lay them down, and to complete

the work and see it safely through the press. As General

Editor of the series, I desire to express my most grateful

thanks to him for his kind and gracious services in[Pg viii]

perfecting a work which had unfortunately been left

incomplete; and all lovers of Old Dorset and readers of

this book will greatly appreciate his good offices.

Few counties can rival Dorset either in natural

beauty or historic interest, and it deserves an honoured

place among the memorials of the counties of England.

In preparing the work the Editors have endeavoured to

make the volume comprehensive, although it is of course

impossible in a single volume to exhaust all the rich

store of historical treasures which the county affords.

After a general sketch of the history of Dorset by the

late Editor, the traces of the earliest races which inhabited

this county are discussed by Mr. Prideaux, who tells of

the ancient barrows in Dorset, and the details of the

Roman occupation are shown by Captain Acland. Dorset

is rich in churches, and no one was more capable to

describe their chief features than Mr. Perkins. His chapter

is followed by others of more detail, dealing with the

three great minsters still standing—Sherborne, Milton,

and Wimborne, the monastic house at Ford, and the

memorial brasses of Dorset. A series of chapters on

some of the chief towns and “islands” of the county

follows, supplemented by a description of two well-known

manor-houses. The literary associations of the county

and some of its witchcraft-superstitions form the subjects

of the concluding chapters. The names of the able writers

who have kindly contributed to this volume will commend

themselves to our readers. The Lord Bishop of Durham,

the Rev. R. Grosvenor Bartelot, Mr. Sidney Heath, Mr.

Wildman, Mr. Prideaux, Mr. Gill, Mrs. King Warry, and[Pg ix]

our other contributors, are among the chief authorities

upon the subjects of which they treat, and our thanks

are due to them for their services; and also to Mr. William

Pye for the beautiful coloured frontispiece, to Mr. Heath

for his charming drawings, and to those who have supplied

photographs for reproduction. We hope that this volume

will find a welcome in the library of every Dorset book-lover,

and meet with the approbation of all who revere

the traditions and historical associations of the county.

P. H. Ditchfield,

General Editor.

|

Page |

| Historic Dorset |

By the Rev. Thomas Perkins, M.A. |

1 |

| The Barrows of Dorset |

By C. S. Prideaux |

19 |

| The Roman Occupation of Dorset |

By Captain J. E. Acland |

28 |

| The Churches of Dorset |

By the Rev. Thomas

Perkins, M.A. |

44 |

| The Memorial Brasses of Dorset |

By W. de C. Prideaux |

62 |

| Sherborne |

By W. B. Wildman, M.A. |

75 |

| Milton Abbey |

By the Rev. Herbert

Pentin, M.A. |

94 |

| Wimborne Minster |

By the Rev. Thomas

Perkins, M.A. |

117 |

| Ford Abbey |

By Sidney Heath |

131 |

| Dorchester |

By the Lord Bishop of Durham, D.D. |

145 |

| Weymouth |

By Sidney Heath |

157 |

| The Isle of Portland |

By Mrs. King Warry |

177 |

| The Isle of Purbeck |

By A. D. Moullin |

187 |

| Corfe Castle |

By Albert Bankes |

200 |

| Poole |

By W. K. Gill |

222 |

| Bridport |

By the Rev. R. Grosvenor

Bartelot, M.A. |

232[Pg xii] |

| Shaftesbury |

By the Rev. Thomas

Perkins, M.A. |

240 |

| Piddletown and Athelhampton |

By Miss Wood Homer |

257 |

| Wolfeton House |

By Albert Bankes |

264 |

| The Literary Associations of

Dorset |

By Miss M. Jourdain |

273 |

| Some Dorset Superstitions |

By Hermann Lea |

292 |

| Index |

307 |

[Pg xiii]

INDEX TO ILLUSTRATIONS

| Ringstead and Holworth |

Frontispiece |

| (From a water-colour sketch by Mr. William Pye) |

|

Page, or

Facing Page |

| Bronze Age Objects from Dorset Round Barrows |

20 |

| (From photographs by Mr. W. Pouncy) |

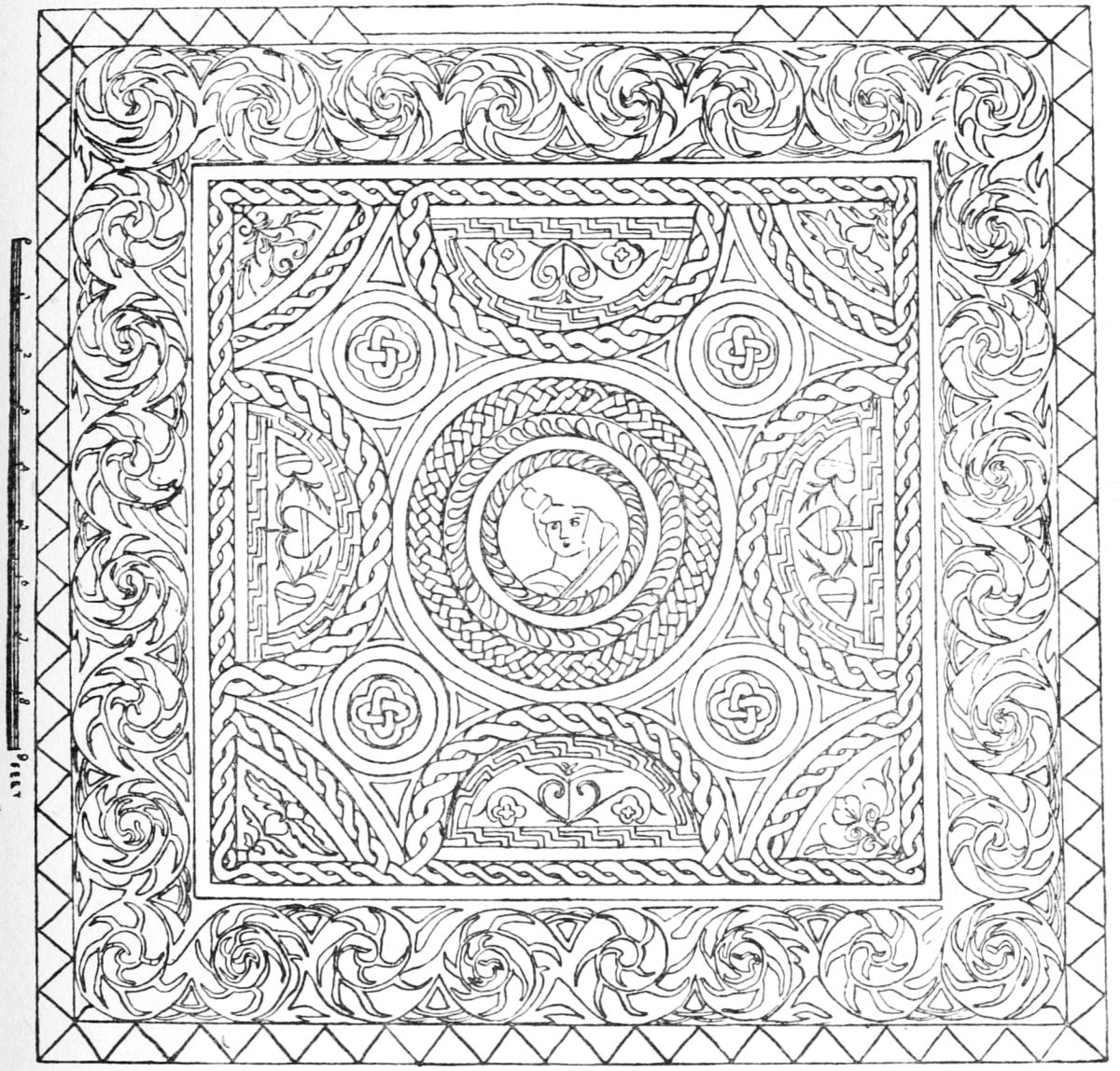

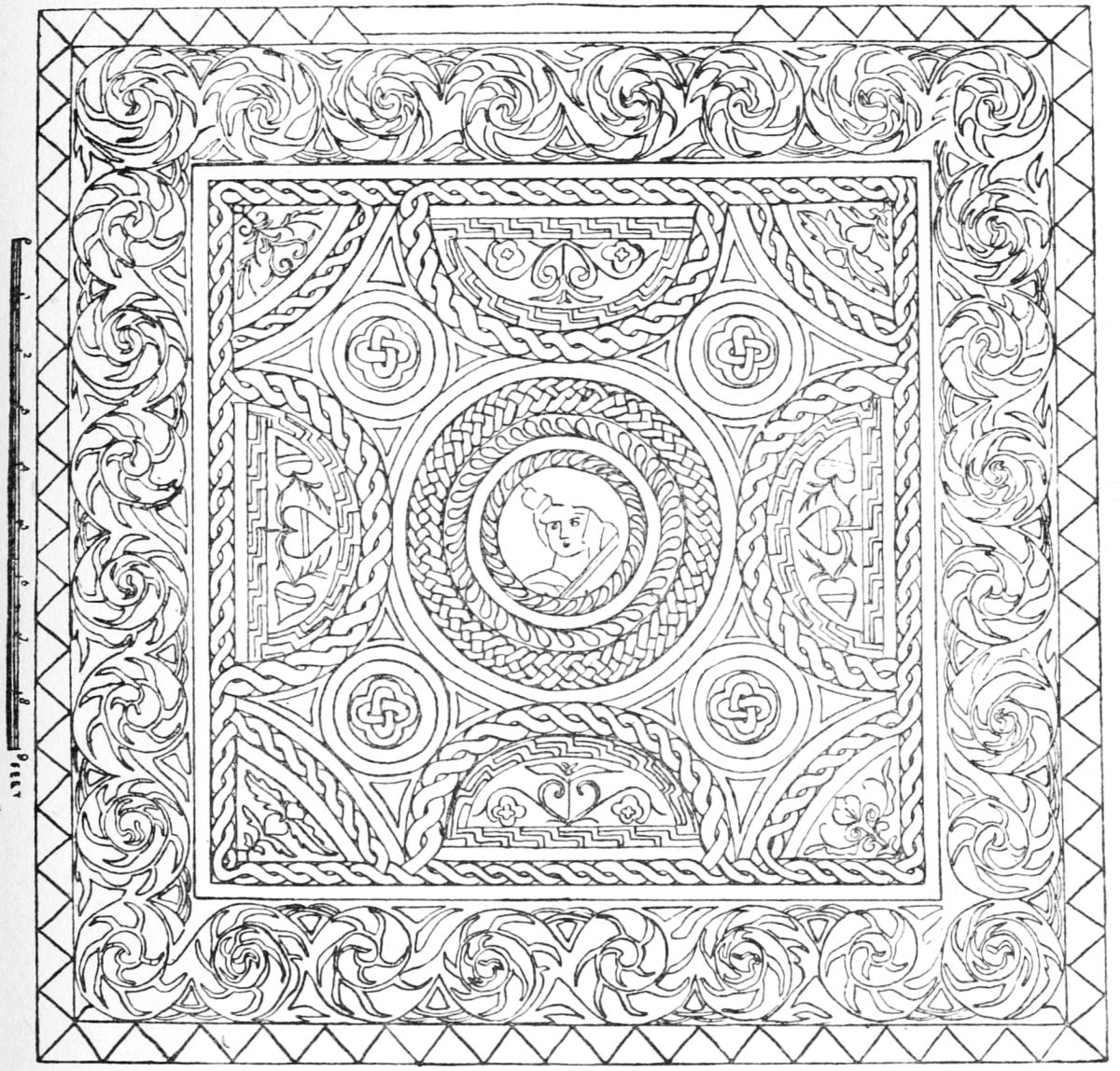

| Part of the Olga Road Tessellated Pavement, Dorchester |

38 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

| Tessellated Pavement at Fifehead Neville |

41 |

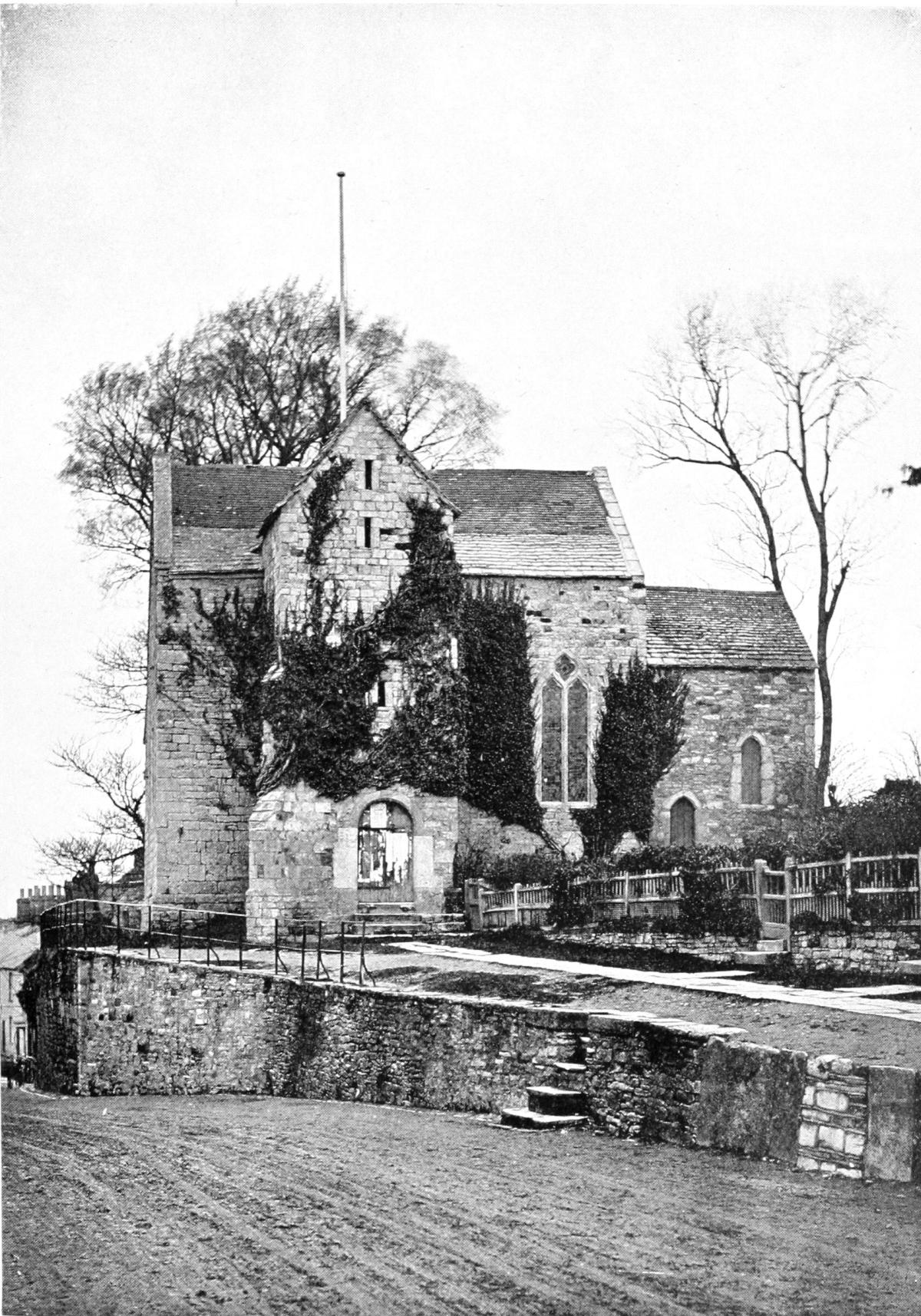

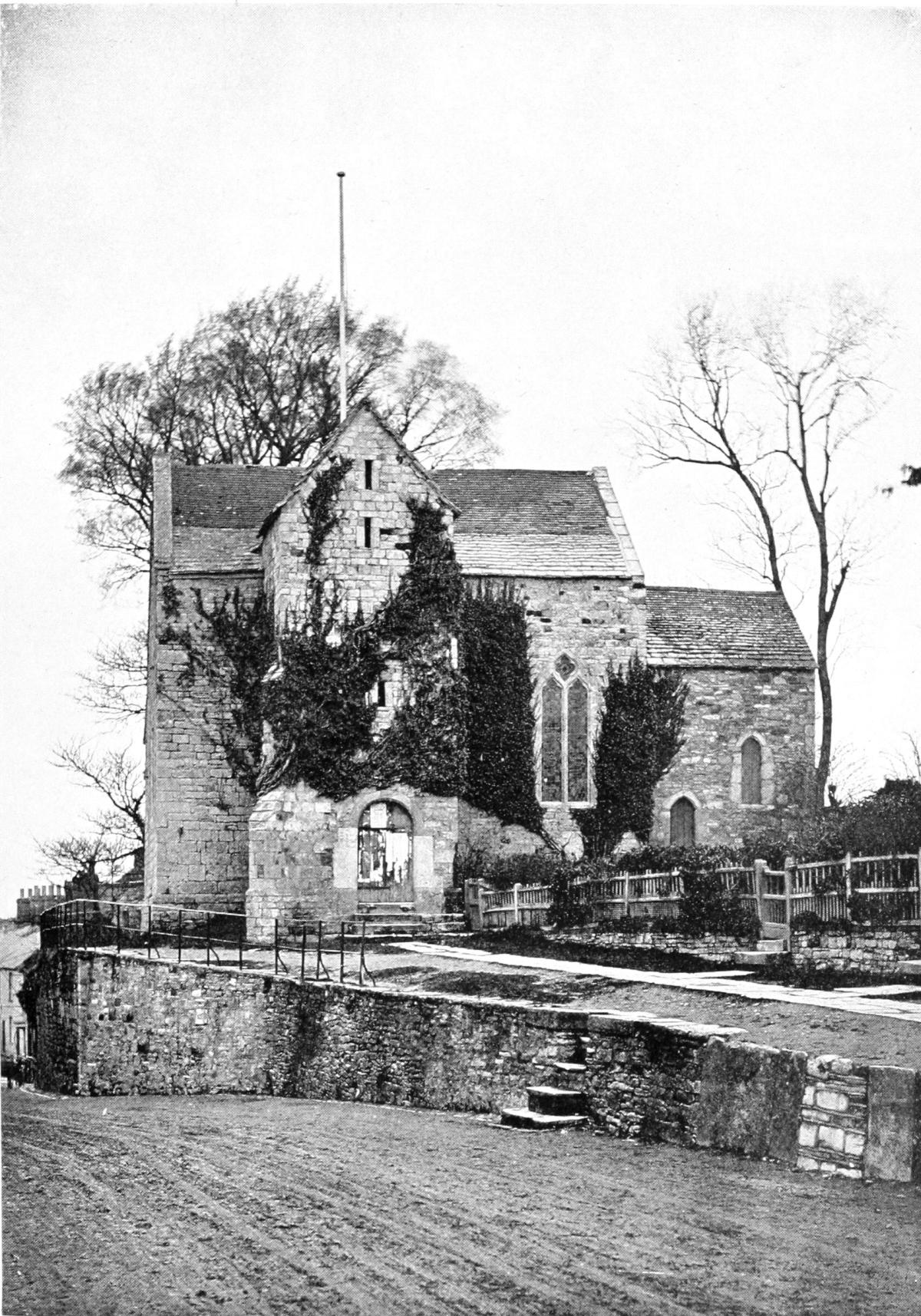

| St. Martin’s Church, Wareham |

48 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

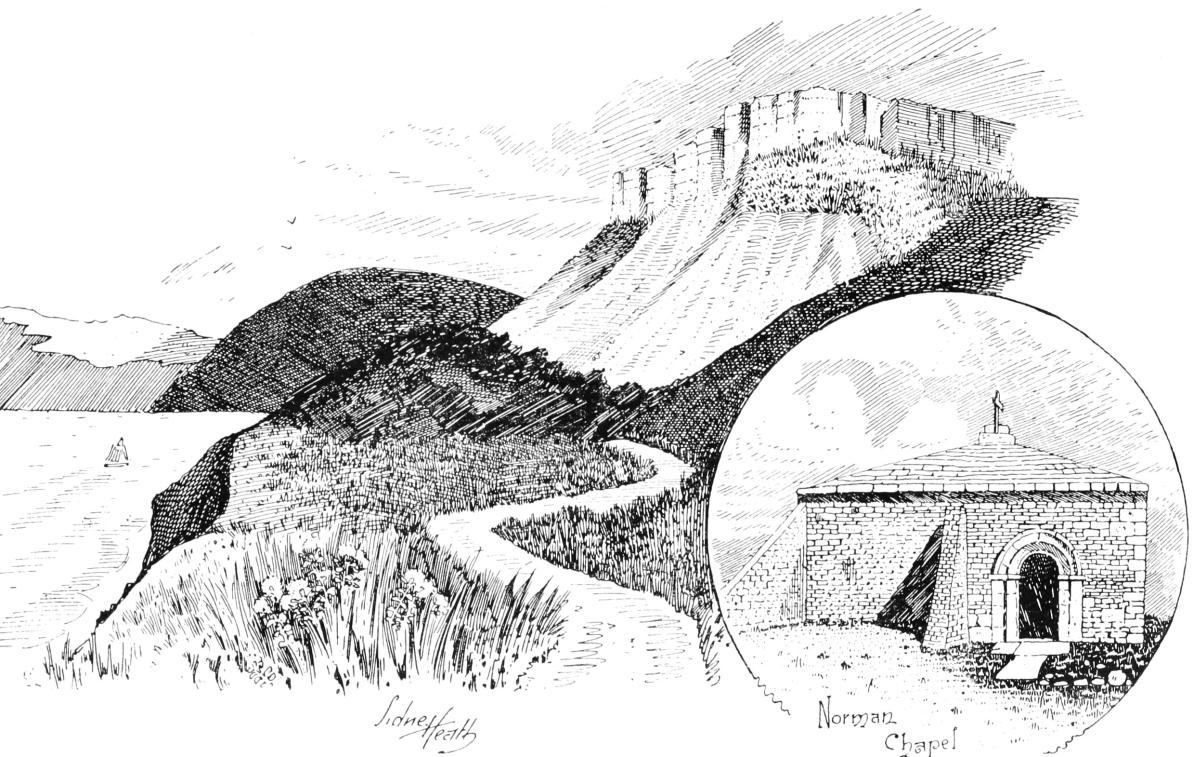

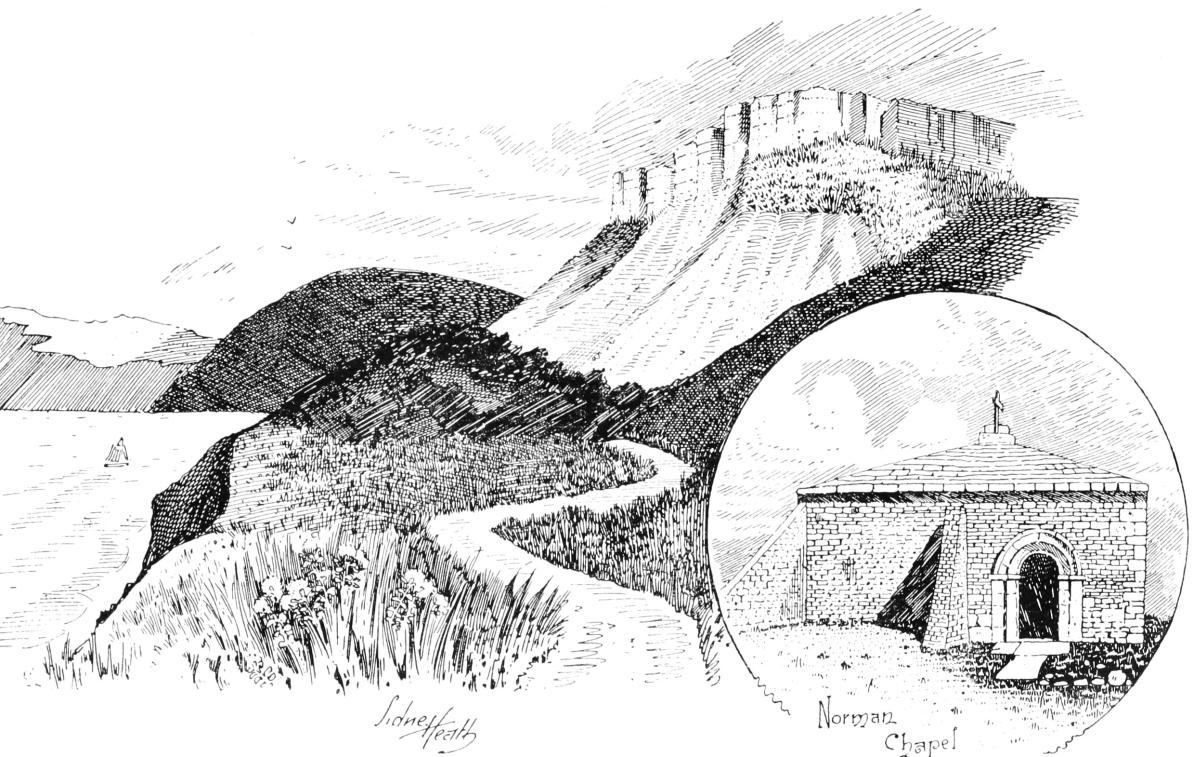

| The Chapel on St. Ealdhelm’s Head |

50 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

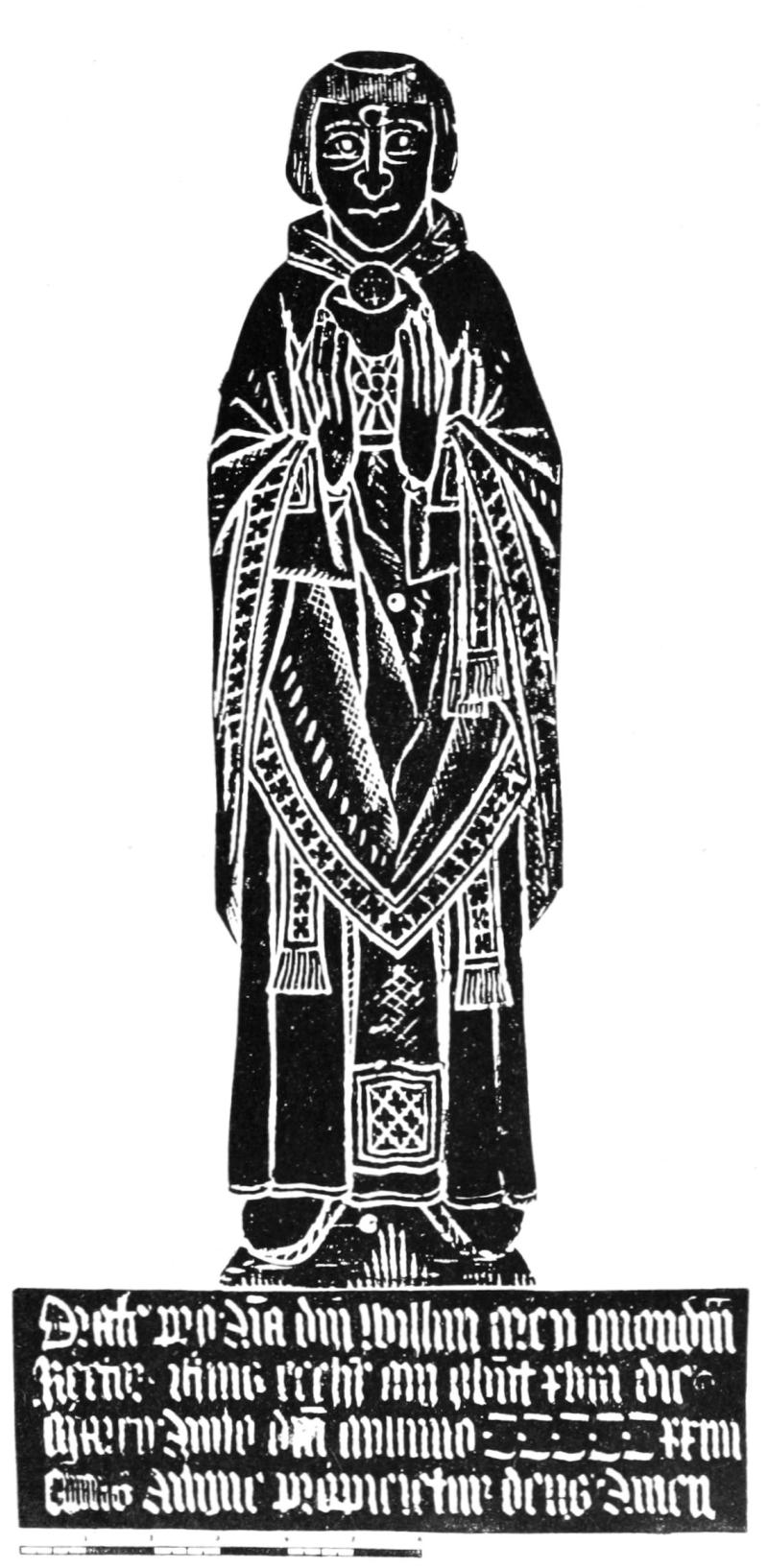

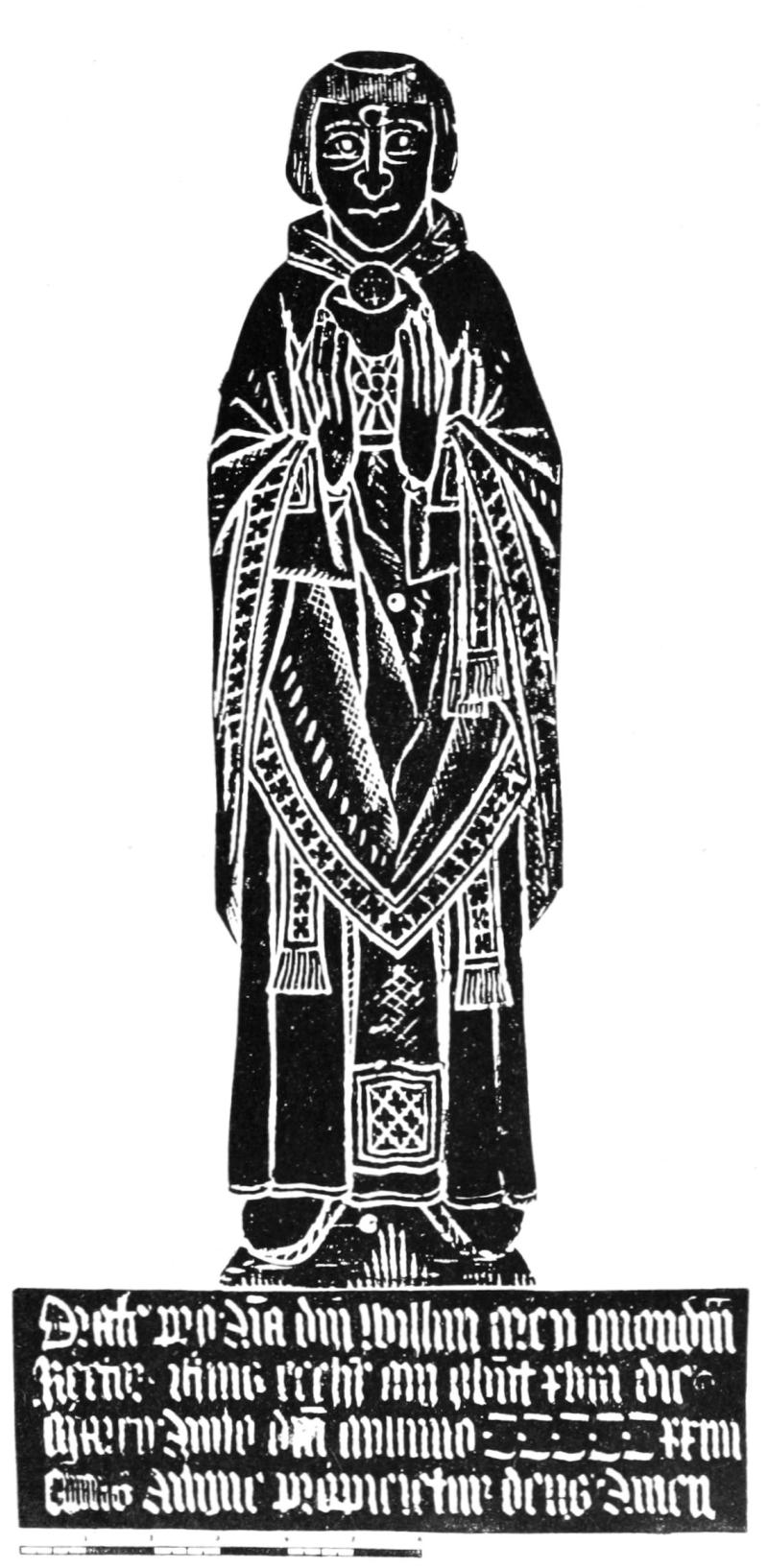

| Brass to William Grey, Rector of Evershot |

70 |

| (From a rubbing by Mr. W. de C. Prideaux) |

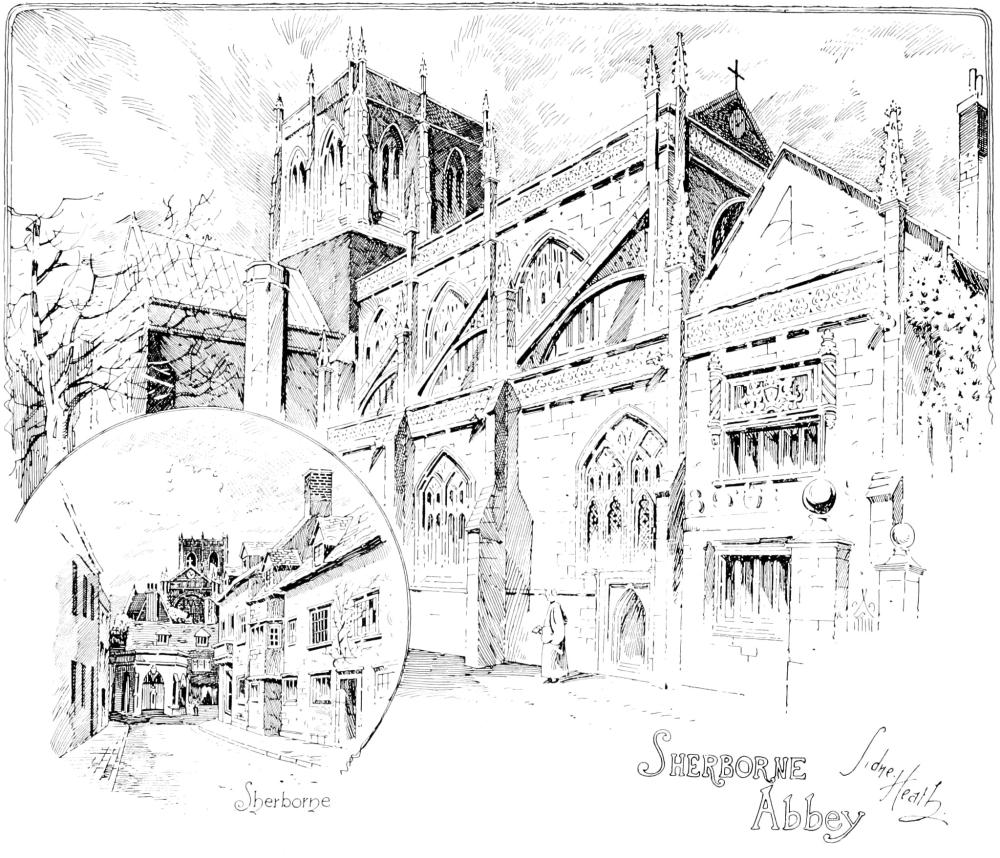

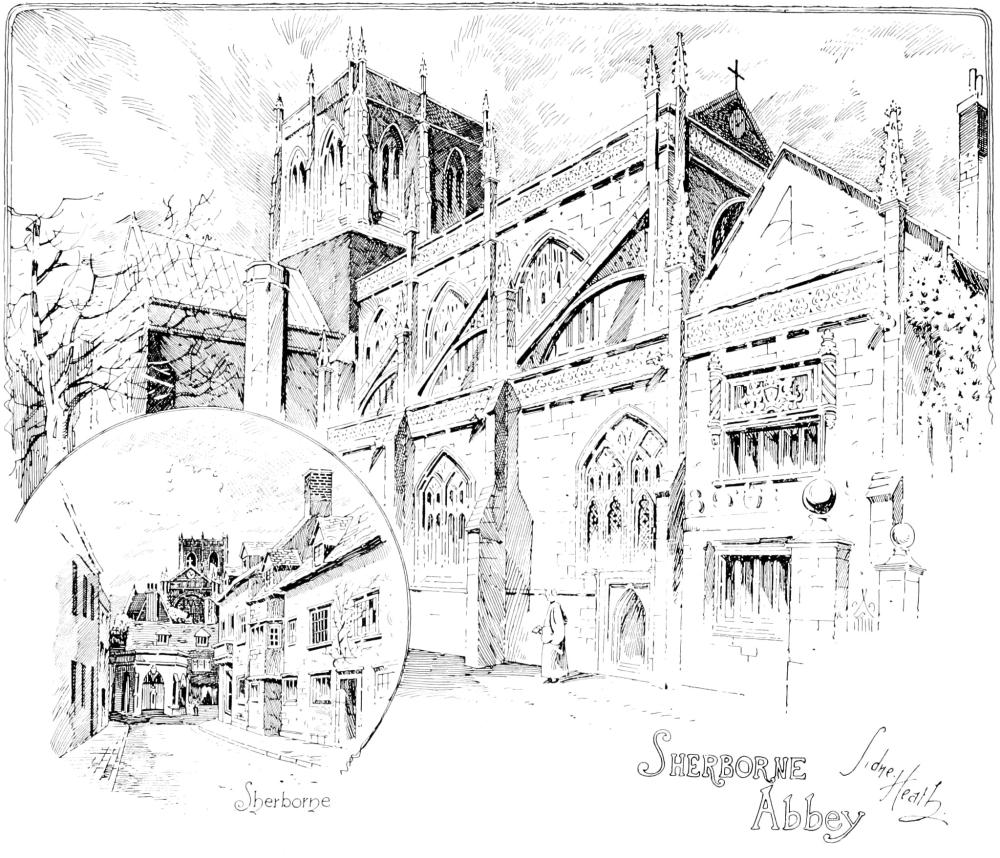

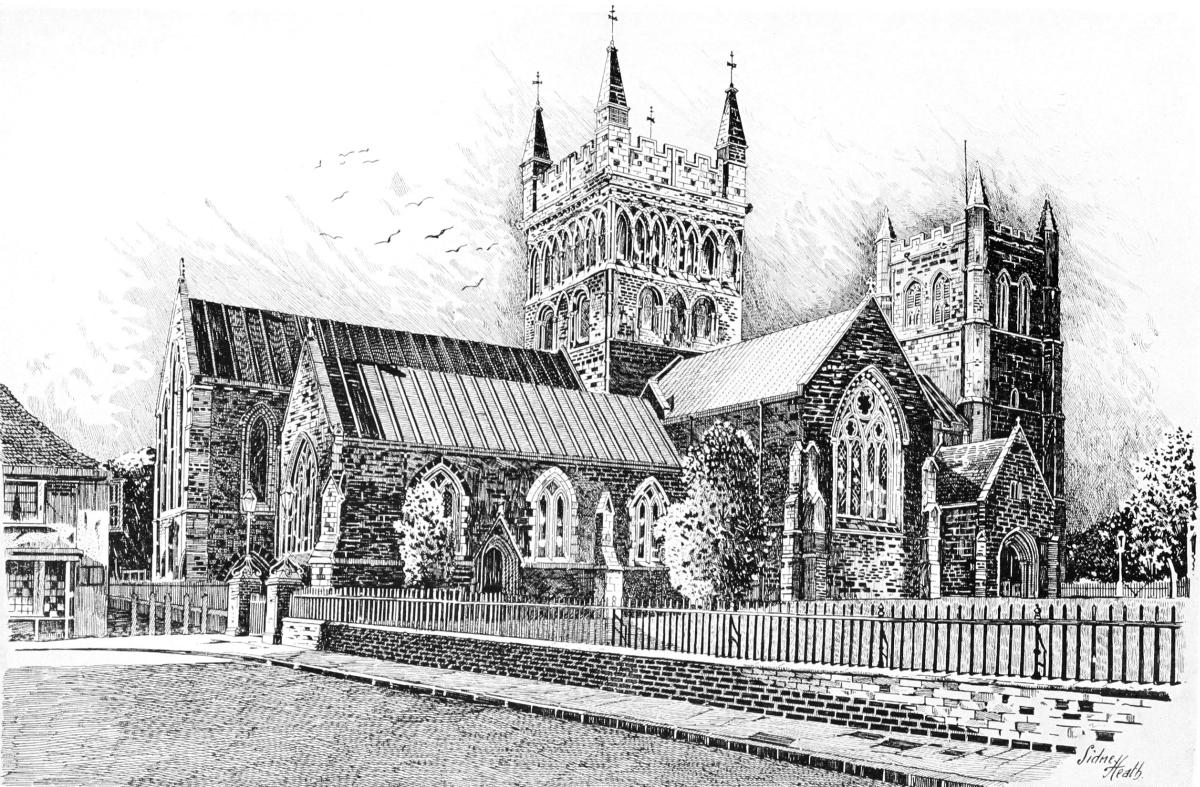

| Sherborne Abbey |

76 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

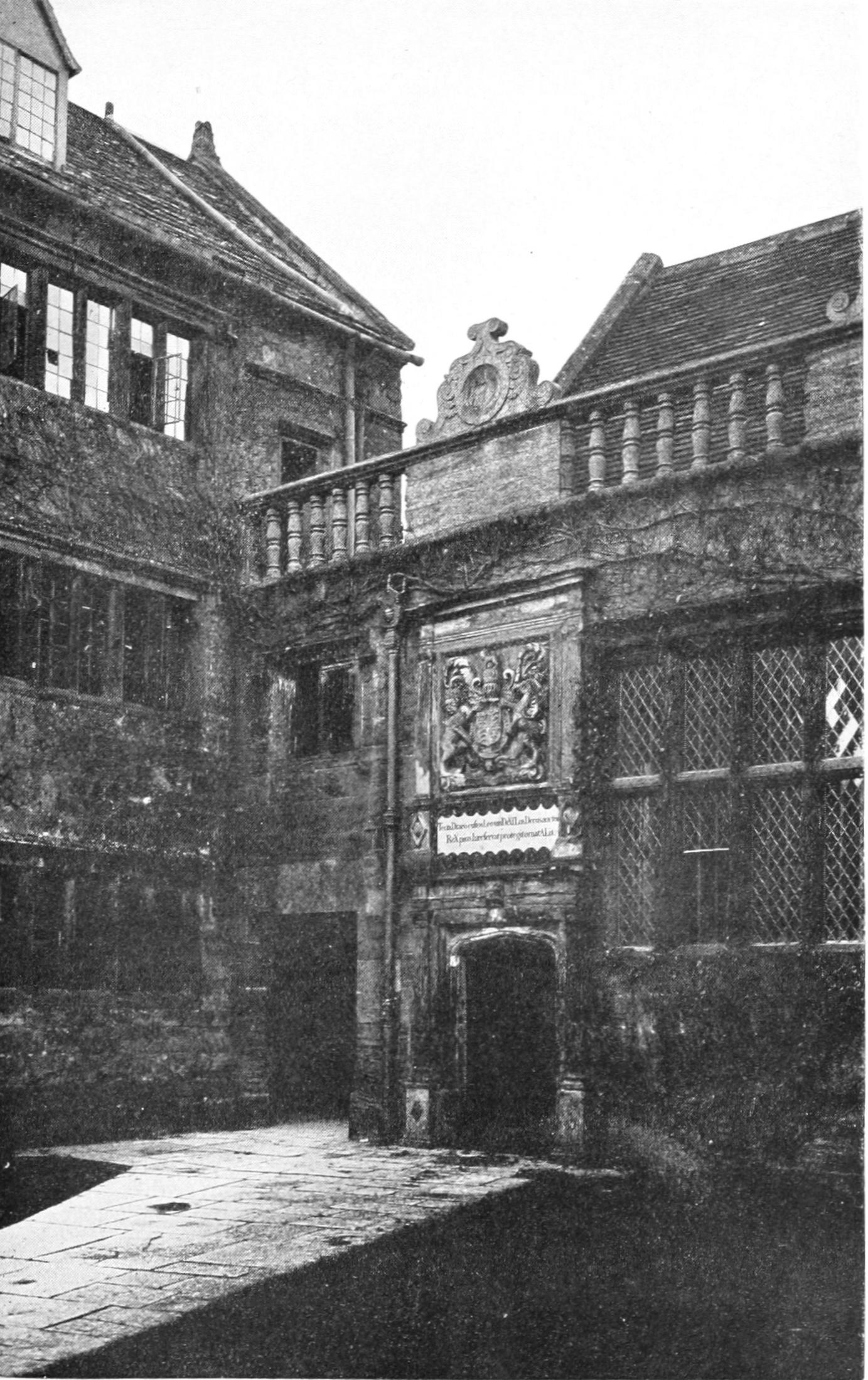

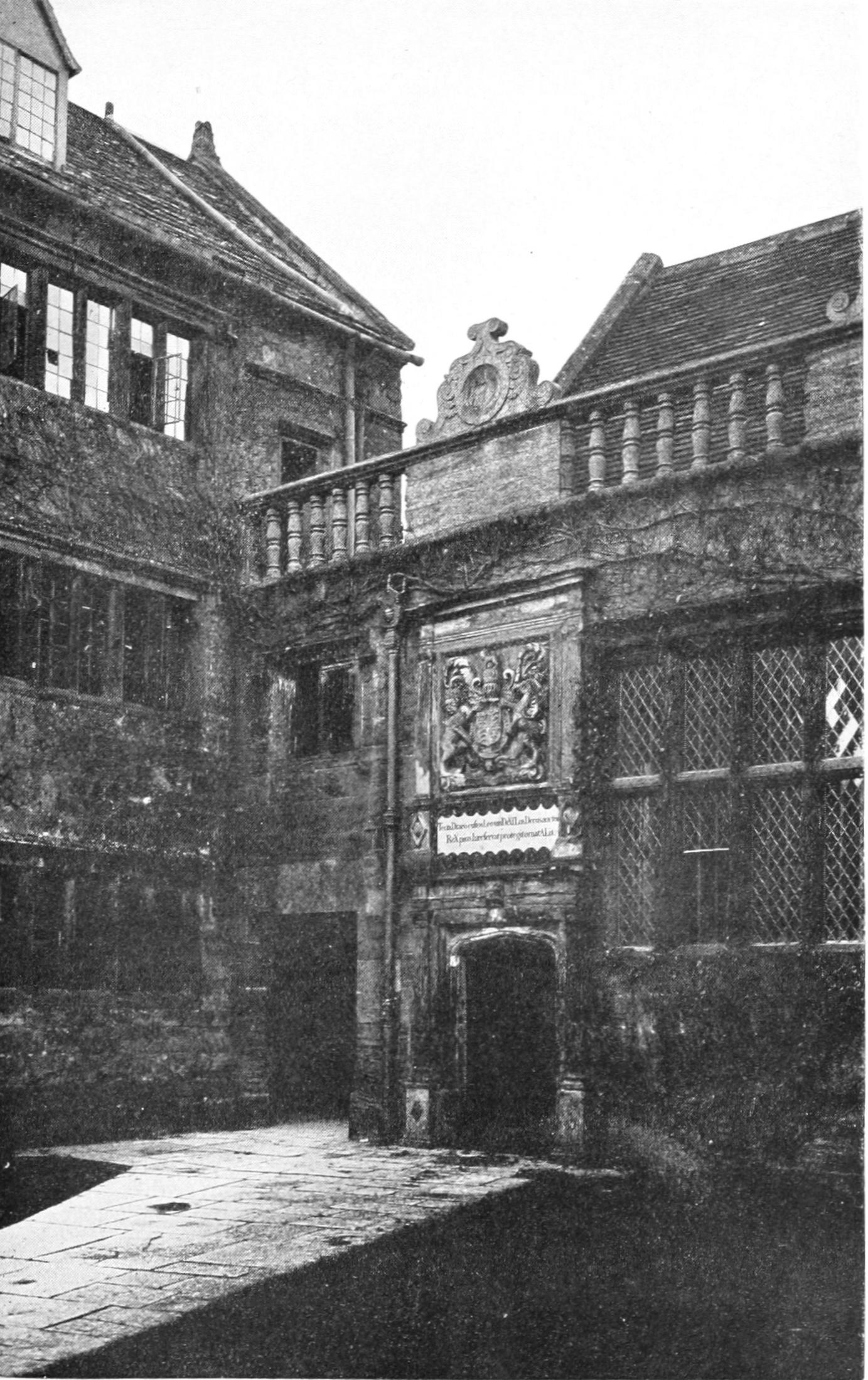

| The Entrance to Sherborne School |

86 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

| Milton Abbey |

94 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

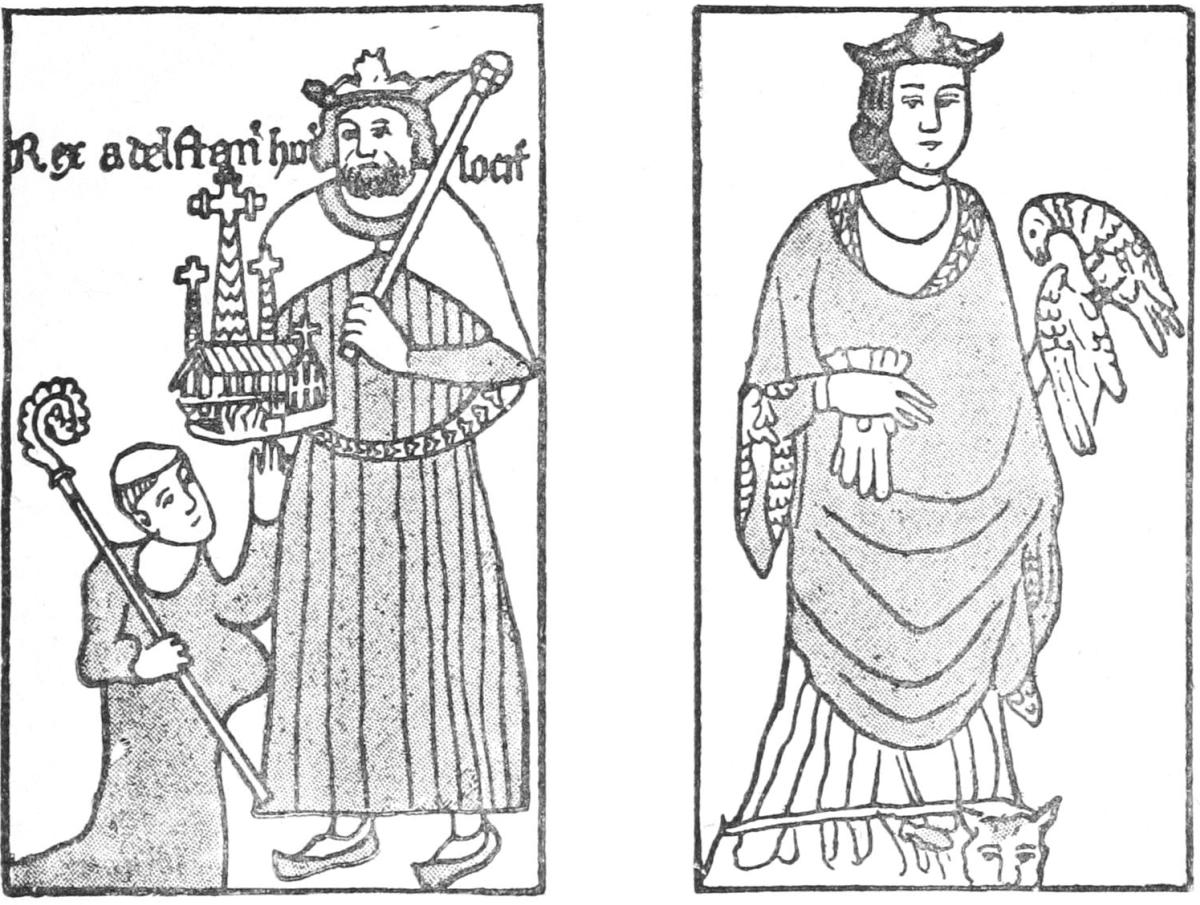

| The Paintings in Milton Abbey |

95 |

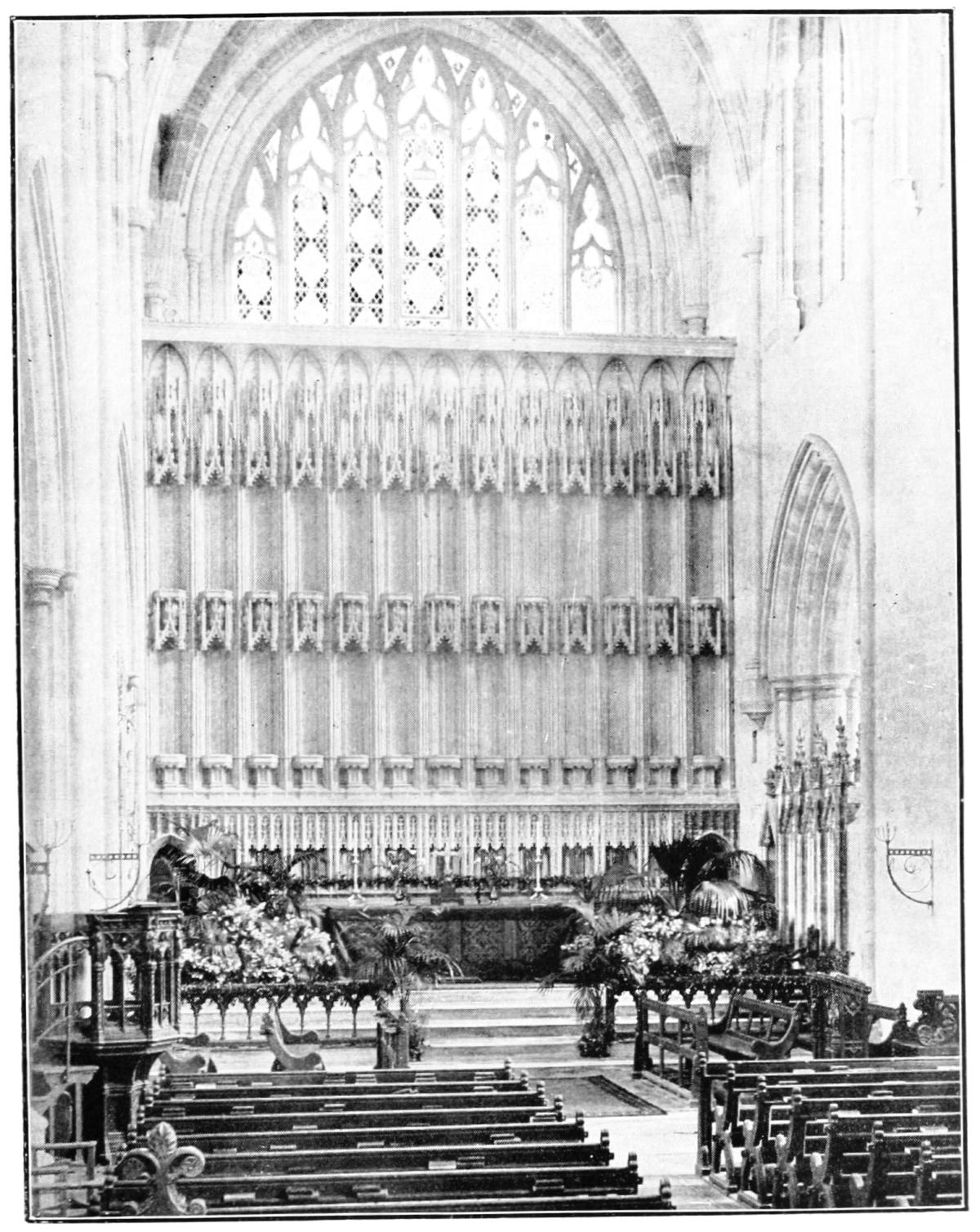

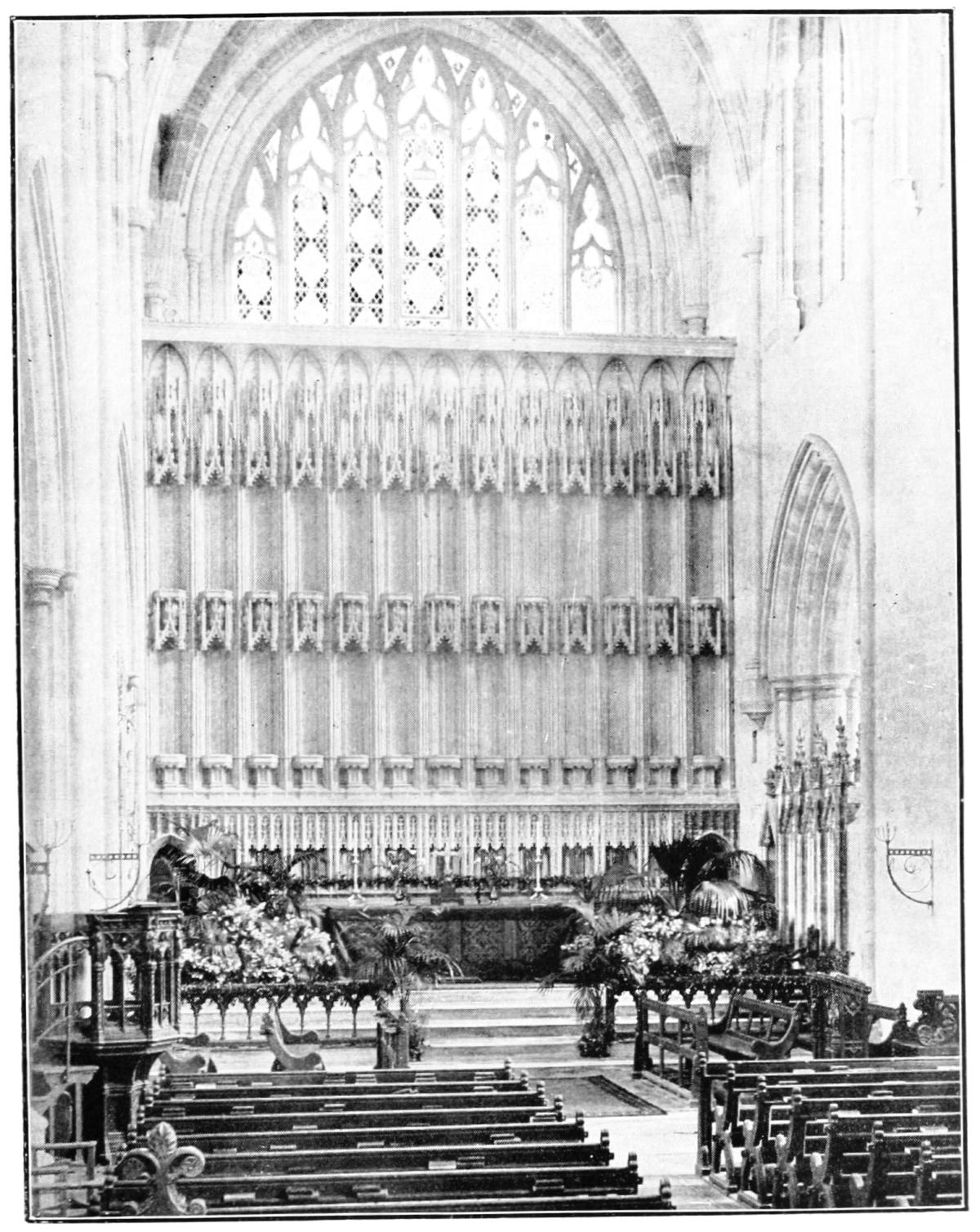

| Milton Abbey: Interior |

96 |

| (From a photograph by Mr. S. Gillingham) |

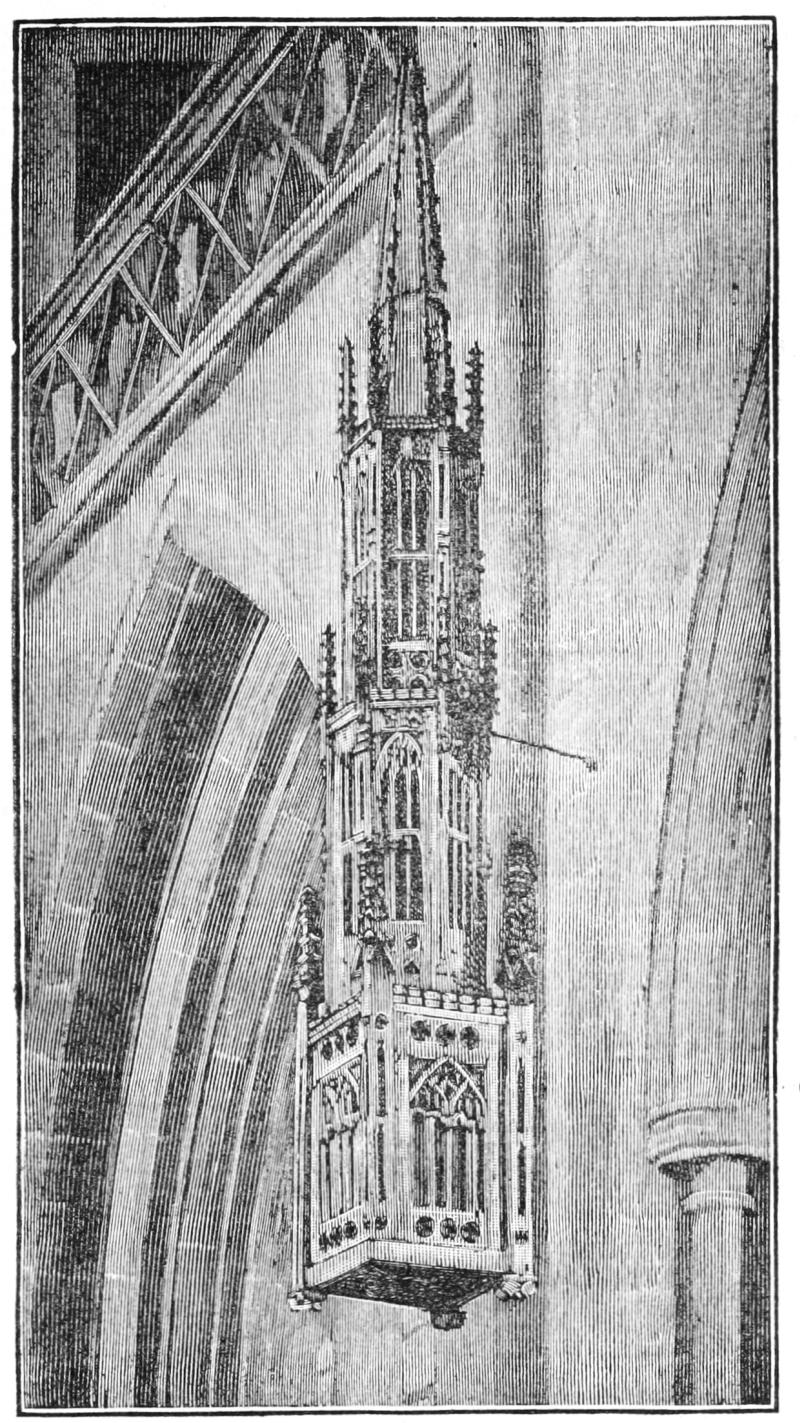

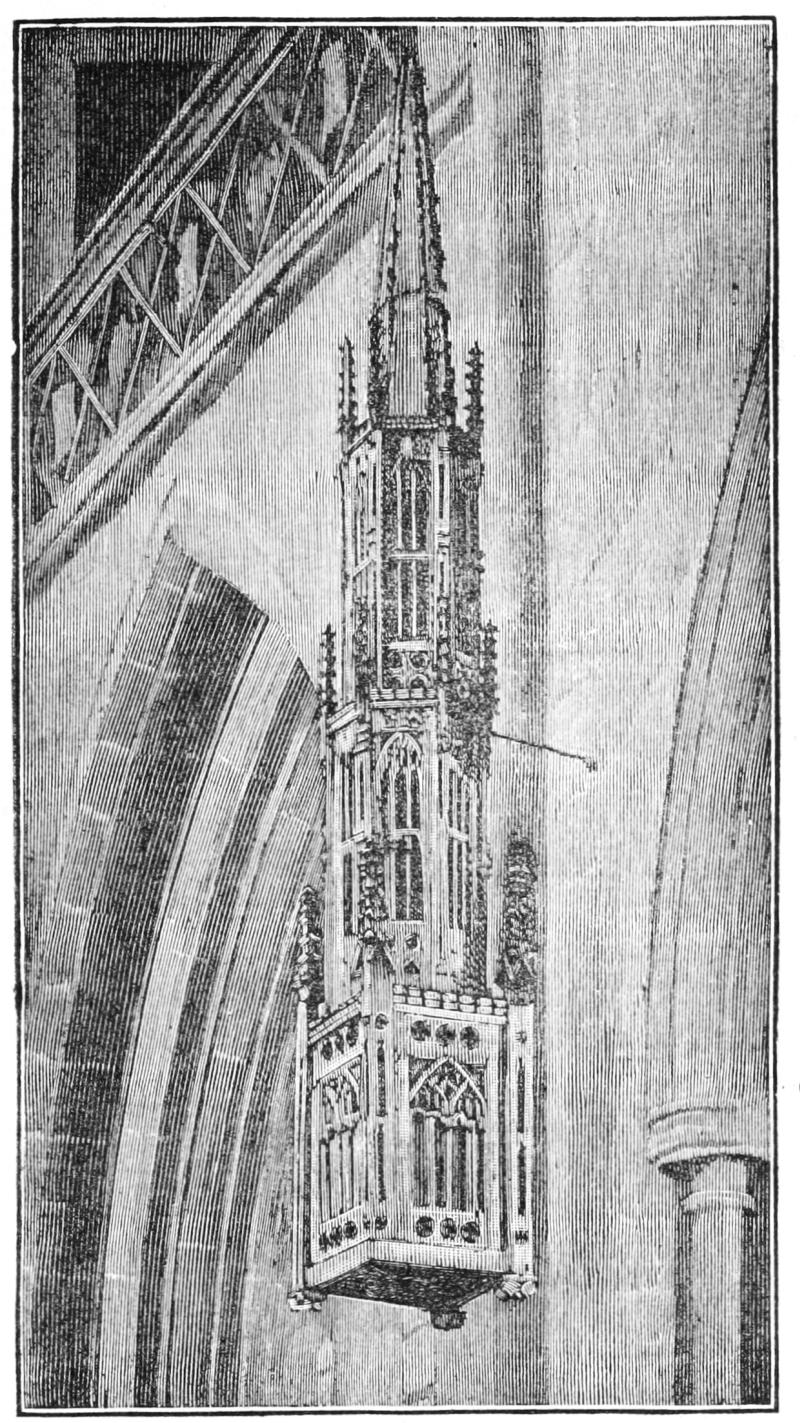

| The Tabernacle in Milton Abbey |

97 |

| ” ” ” |

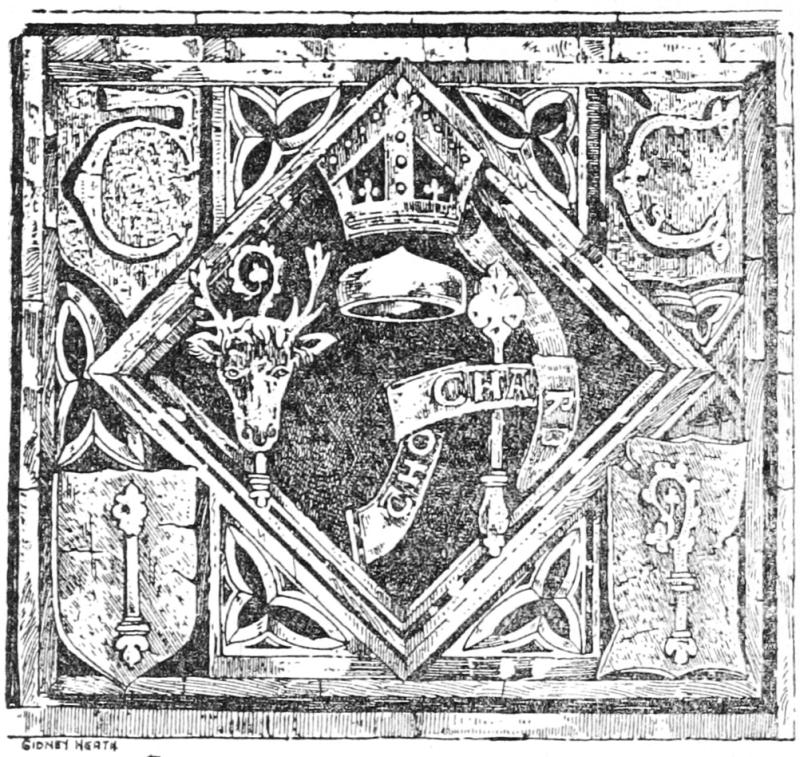

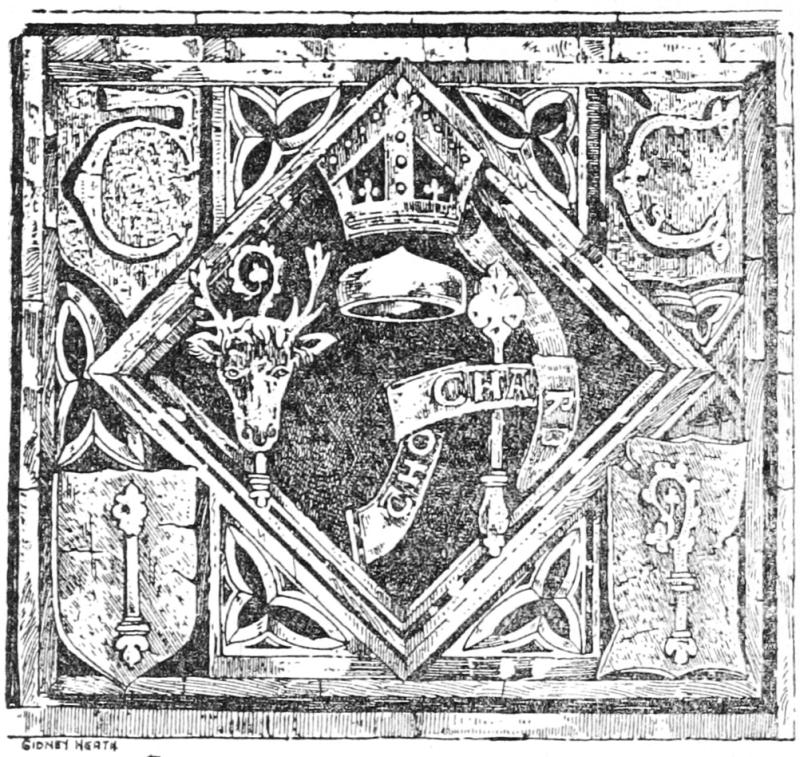

| Abbot Middleton’s Rebus |

101 |

| St. Catherine’s Chapel, Milton Abbey |

104 |

| (From a photograph by Mr. S. Gillingham) |

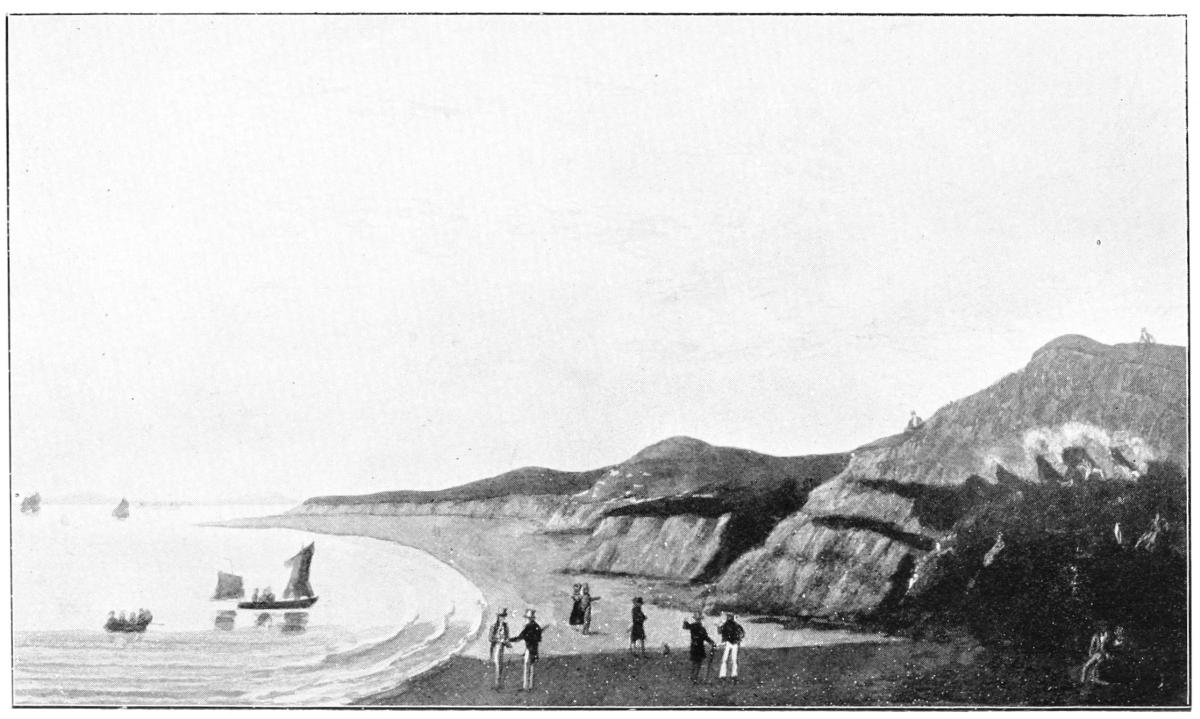

| Holworth Burning Cliff in 1827 |

106 |

| (From a coloured print by Mr. E. Vivian)[Pg xiv] |

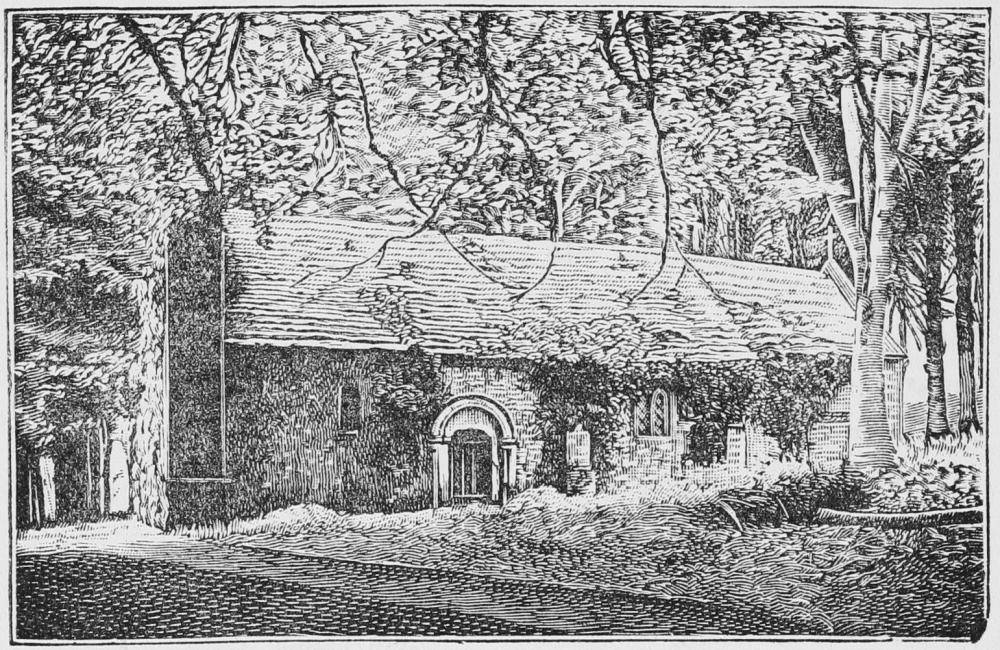

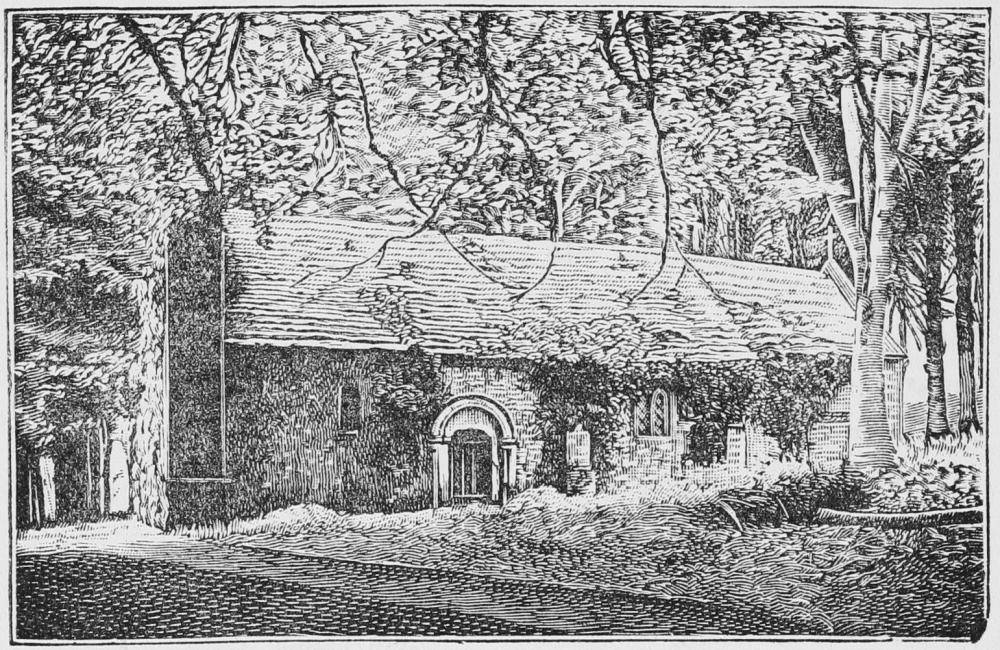

| Liscombe Chapel |

107 |

| (From a photograph by Mr. S. Gillingham) |

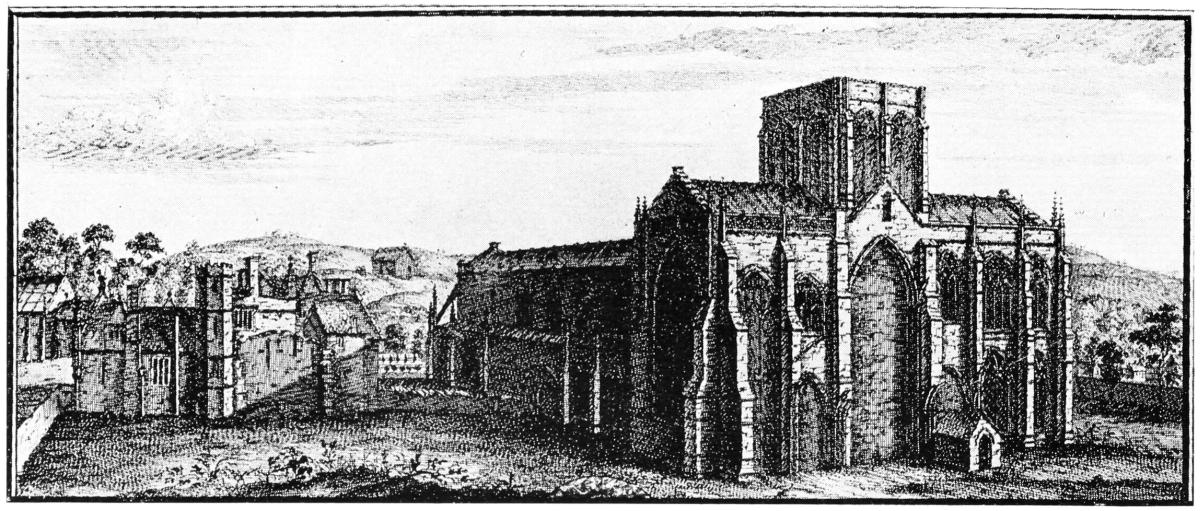

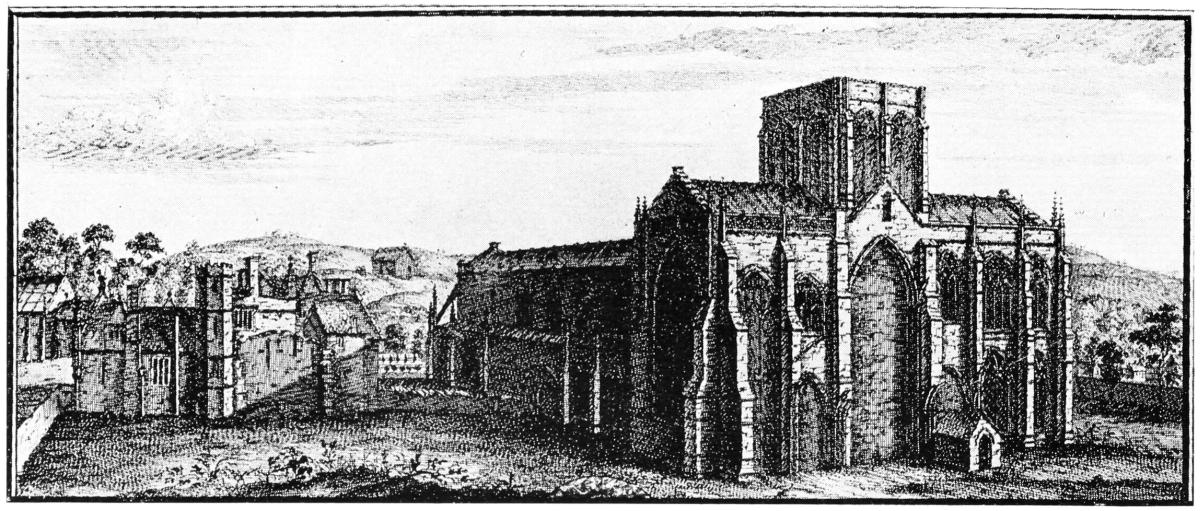

| Milton Abbey in the year 1733 |

110 |

| (From an engraving by Messrs. S. and N. Buck) |

| The Seal of the Town of Milton in America |

116 |

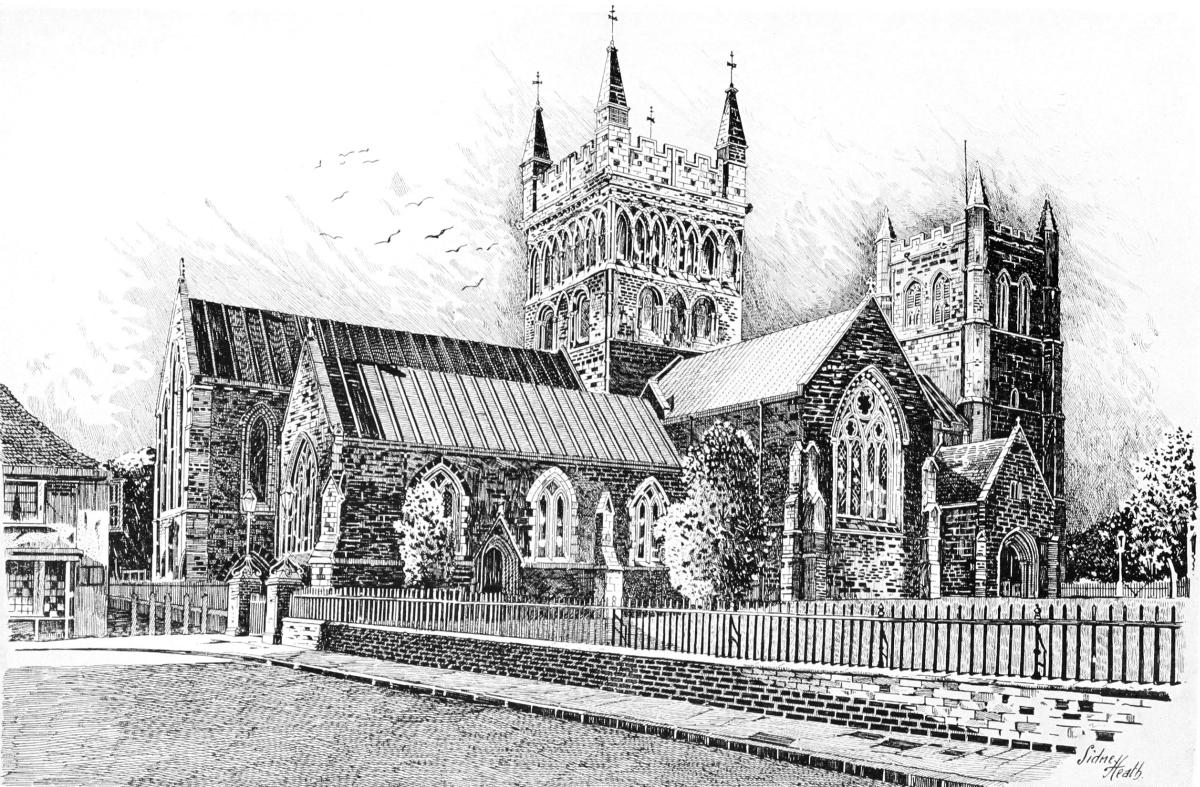

| Wimborne Minster |

118 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

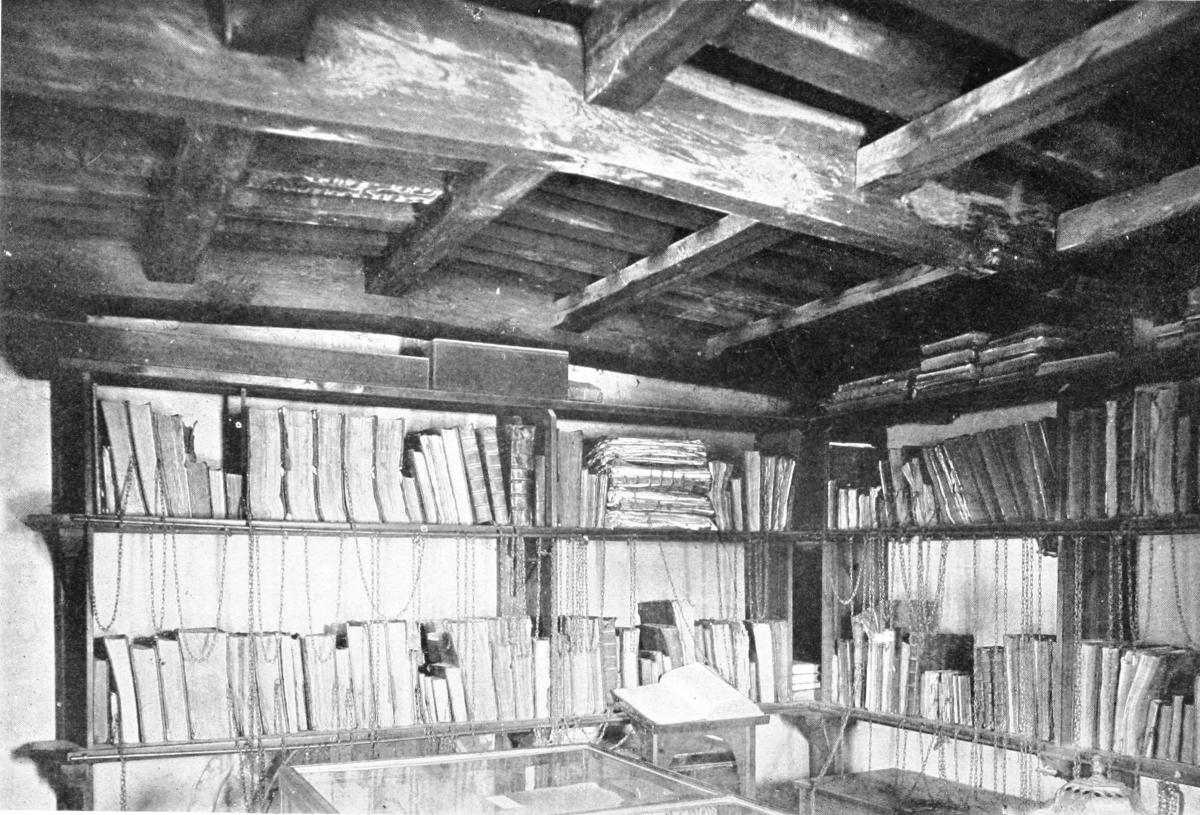

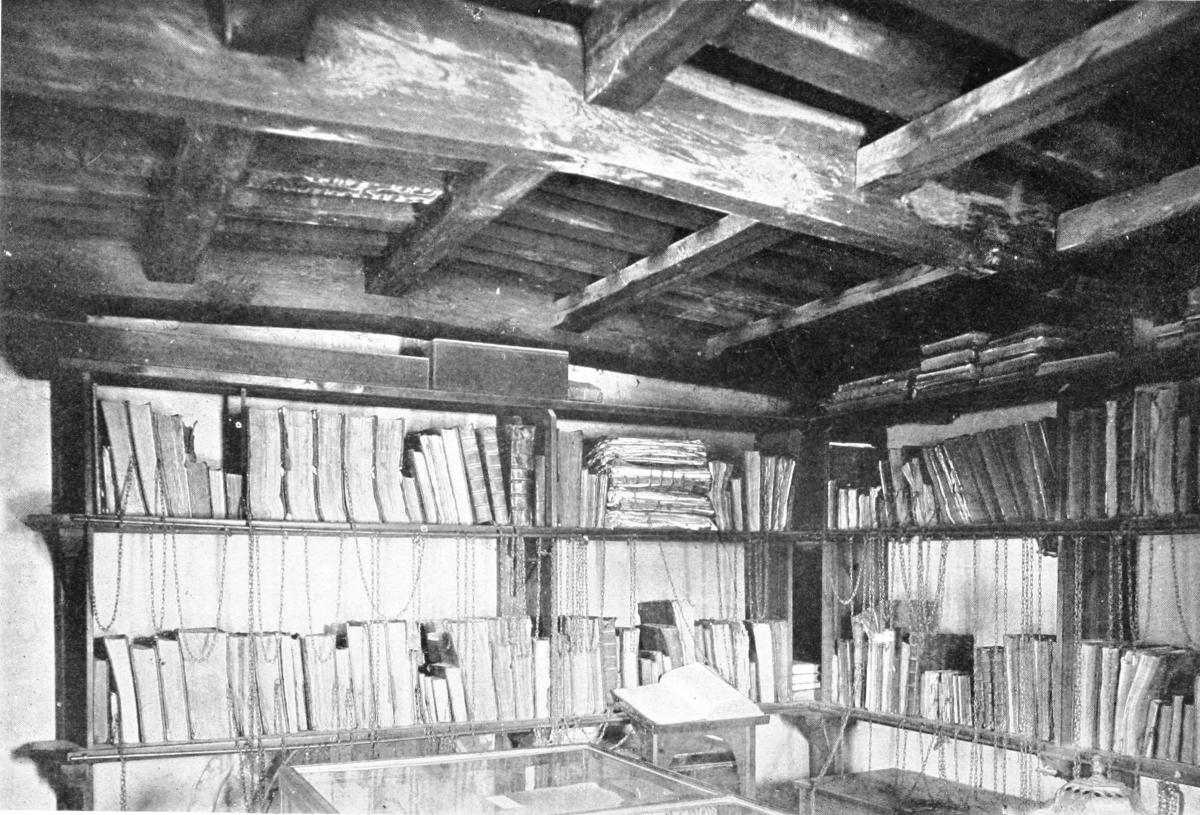

| The Chained Library, Wimborne Minster |

128 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

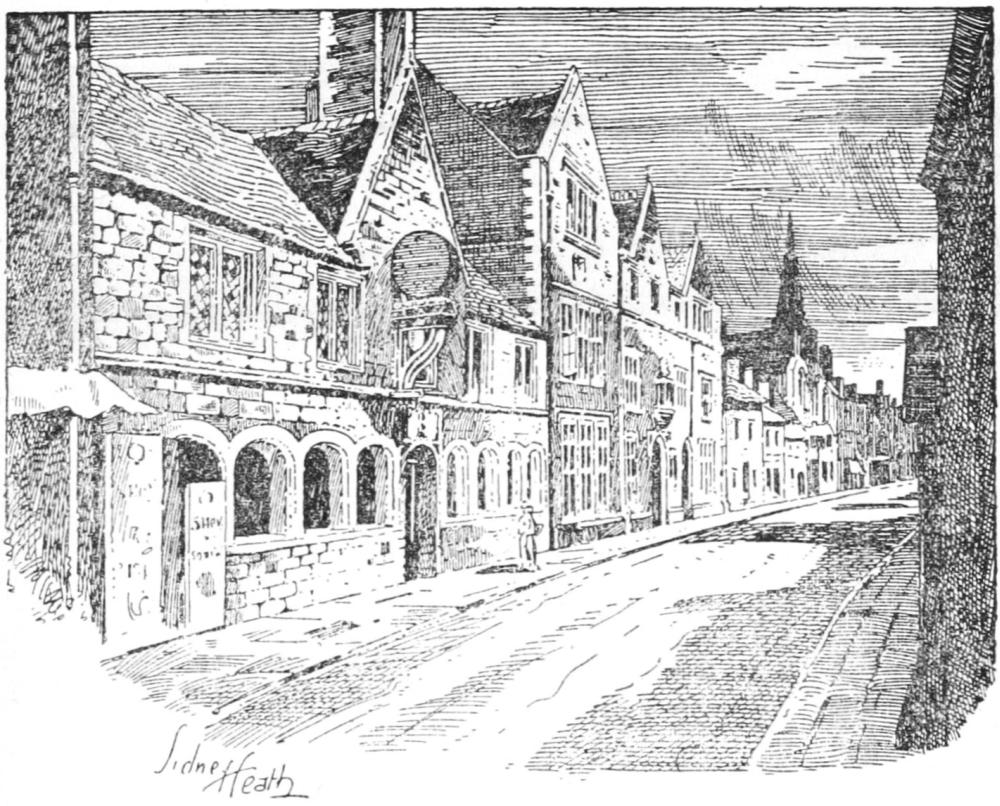

| Ford Abbey |

132 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

| Details from Cloisters, Ford Abbey |

134 |

| (From drawings by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

| The Chapel, Ford Abbey |

136 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

| Panel from Cloisters, Ford Abbey |

136 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

| The Seal of Ford Abbey |

140 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

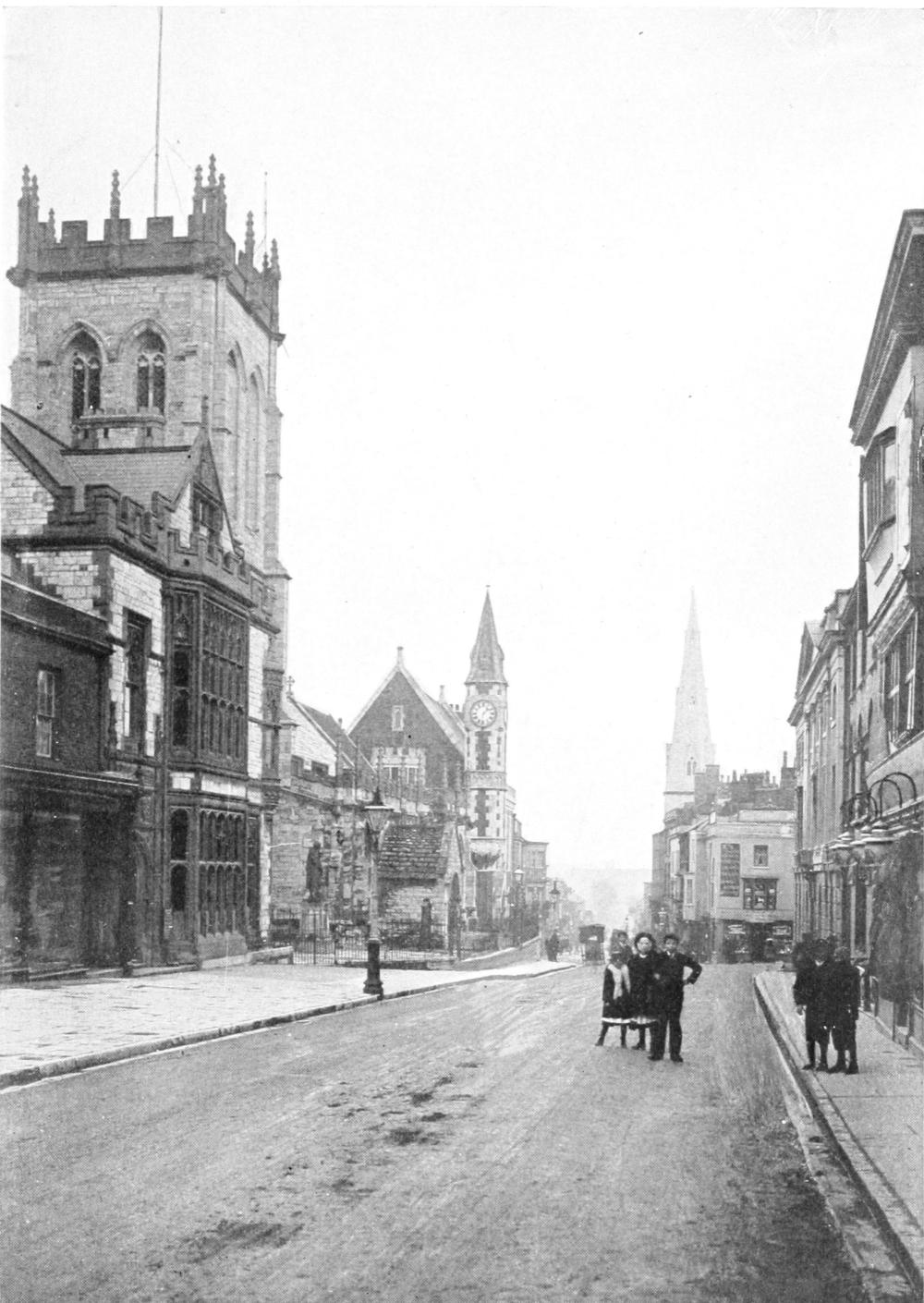

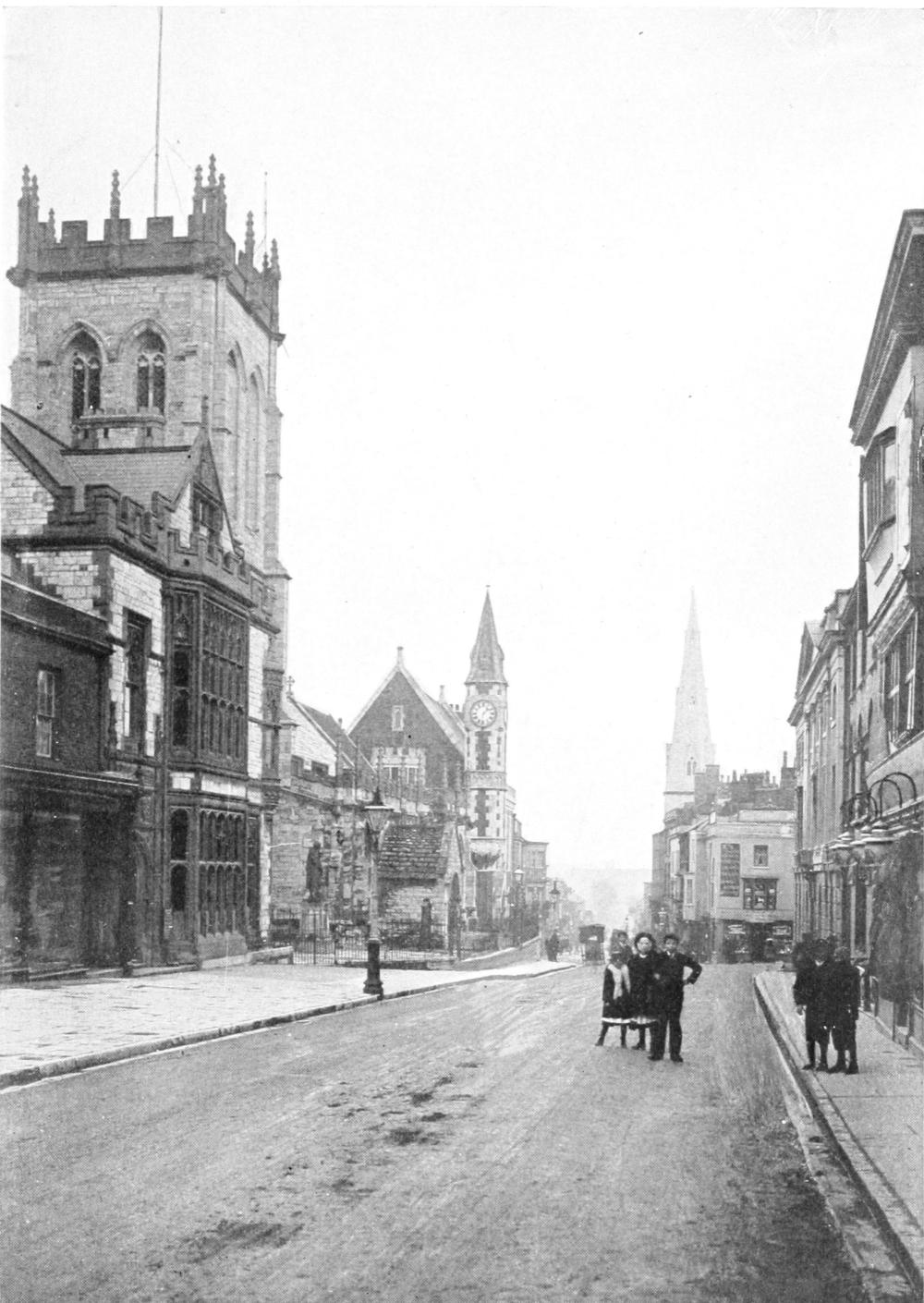

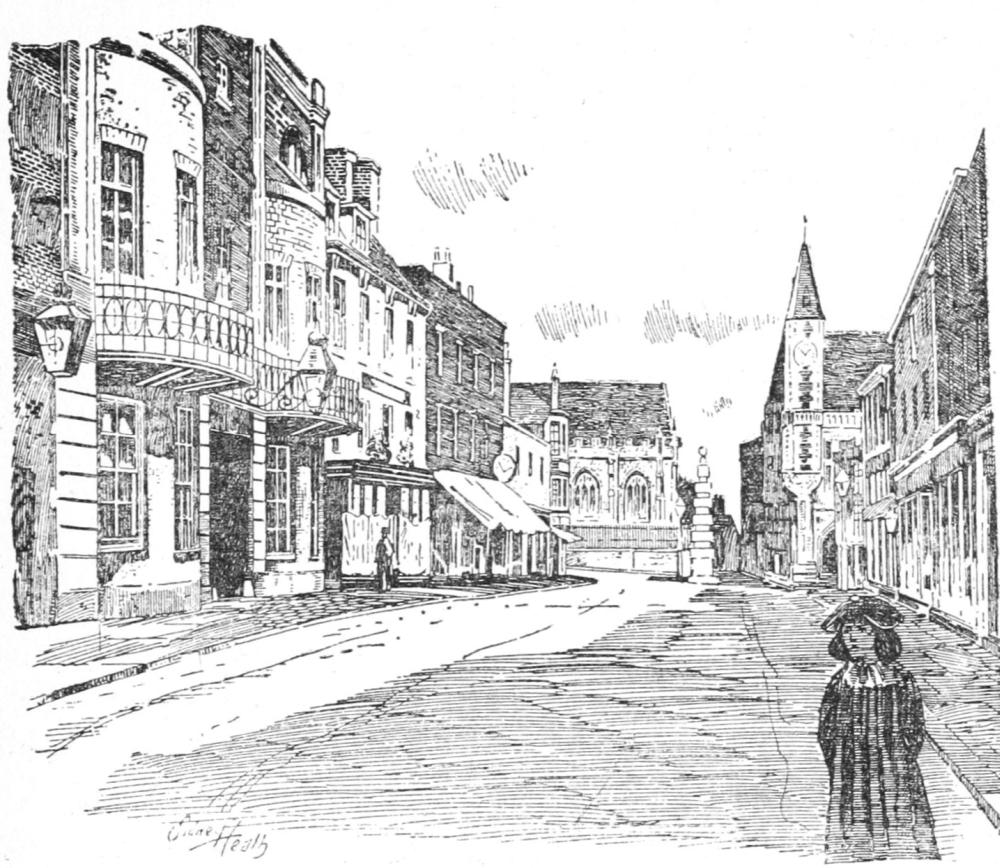

| High Street, Dorchester |

146 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

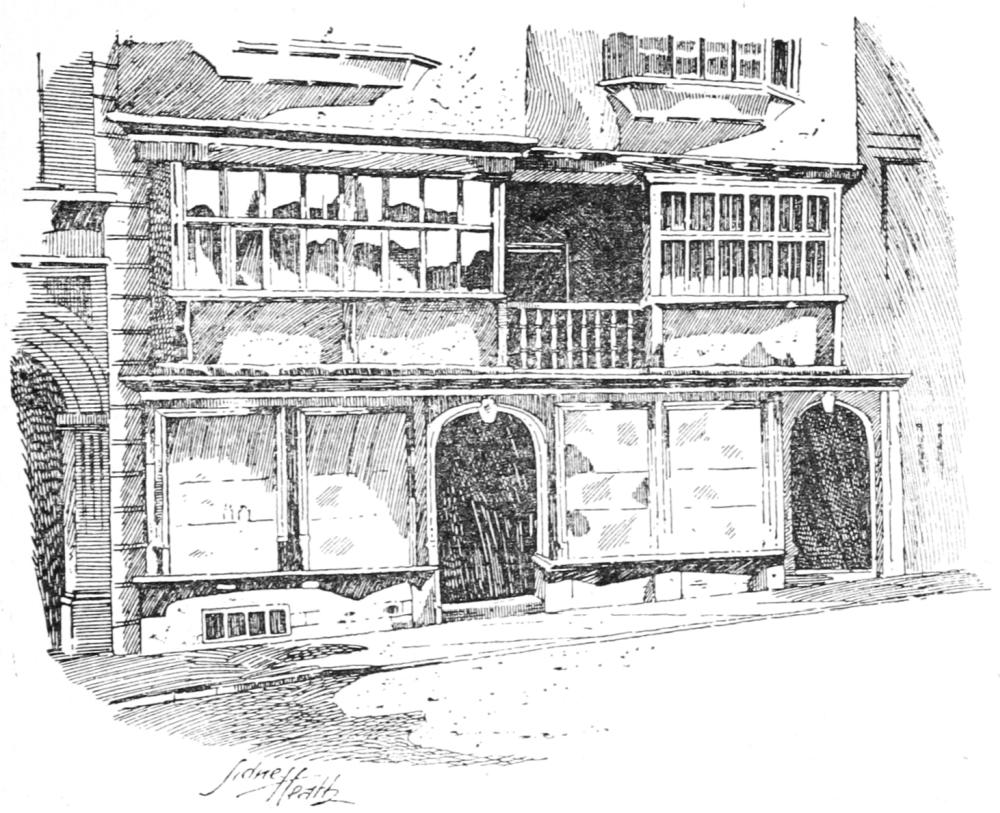

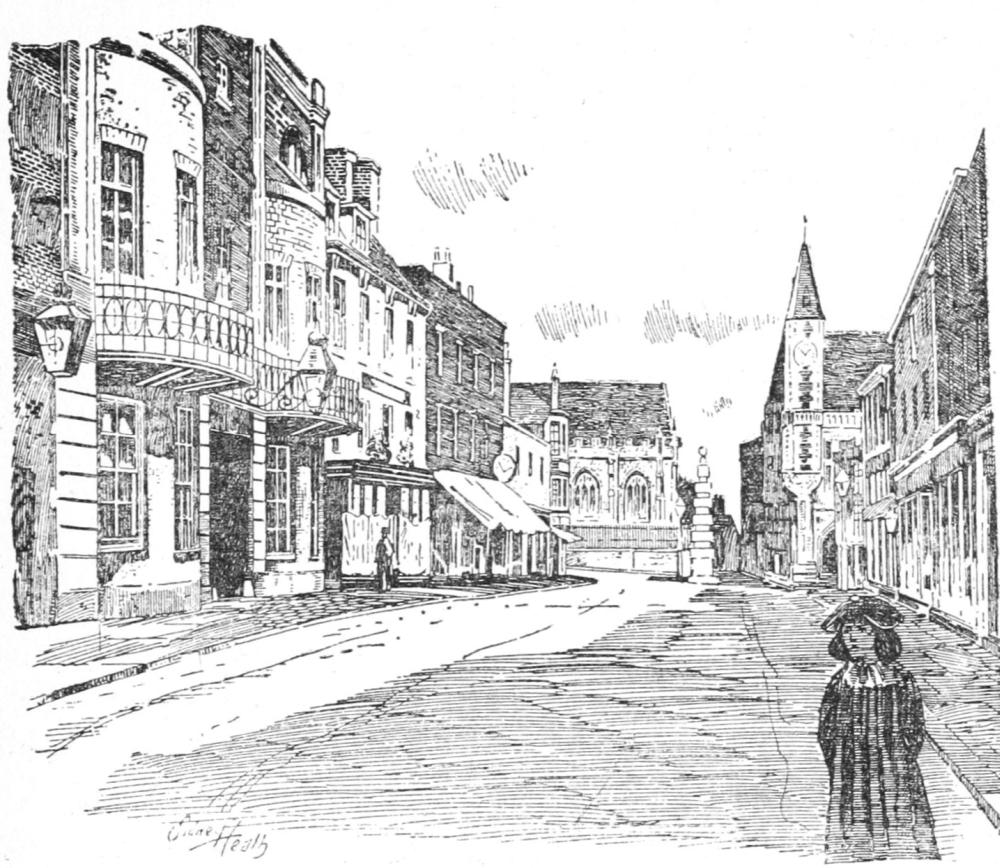

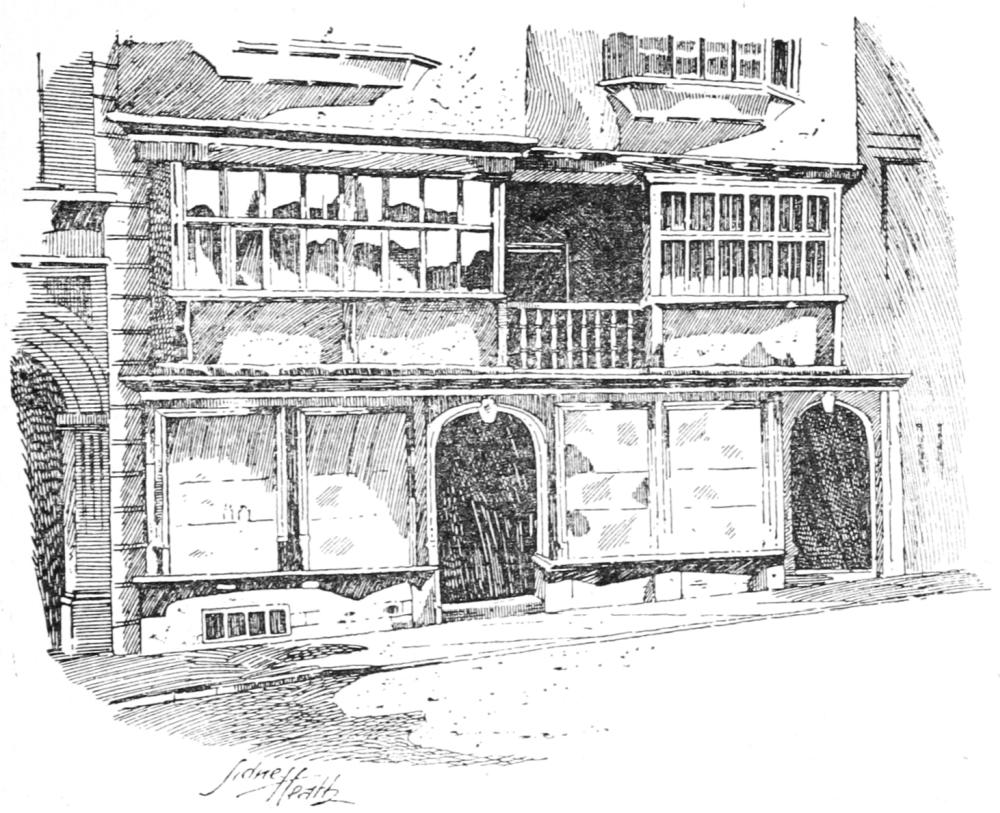

| Judge Jeffreys’ Lodgings, Dorchester |

149 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

| Cornhill, Dorchester |

153 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

| “Napper’s Mite,” Dorchester |

155 |

| ” ” ” |

| The Quay, Weymouth |

158 |

| ” ” ” |

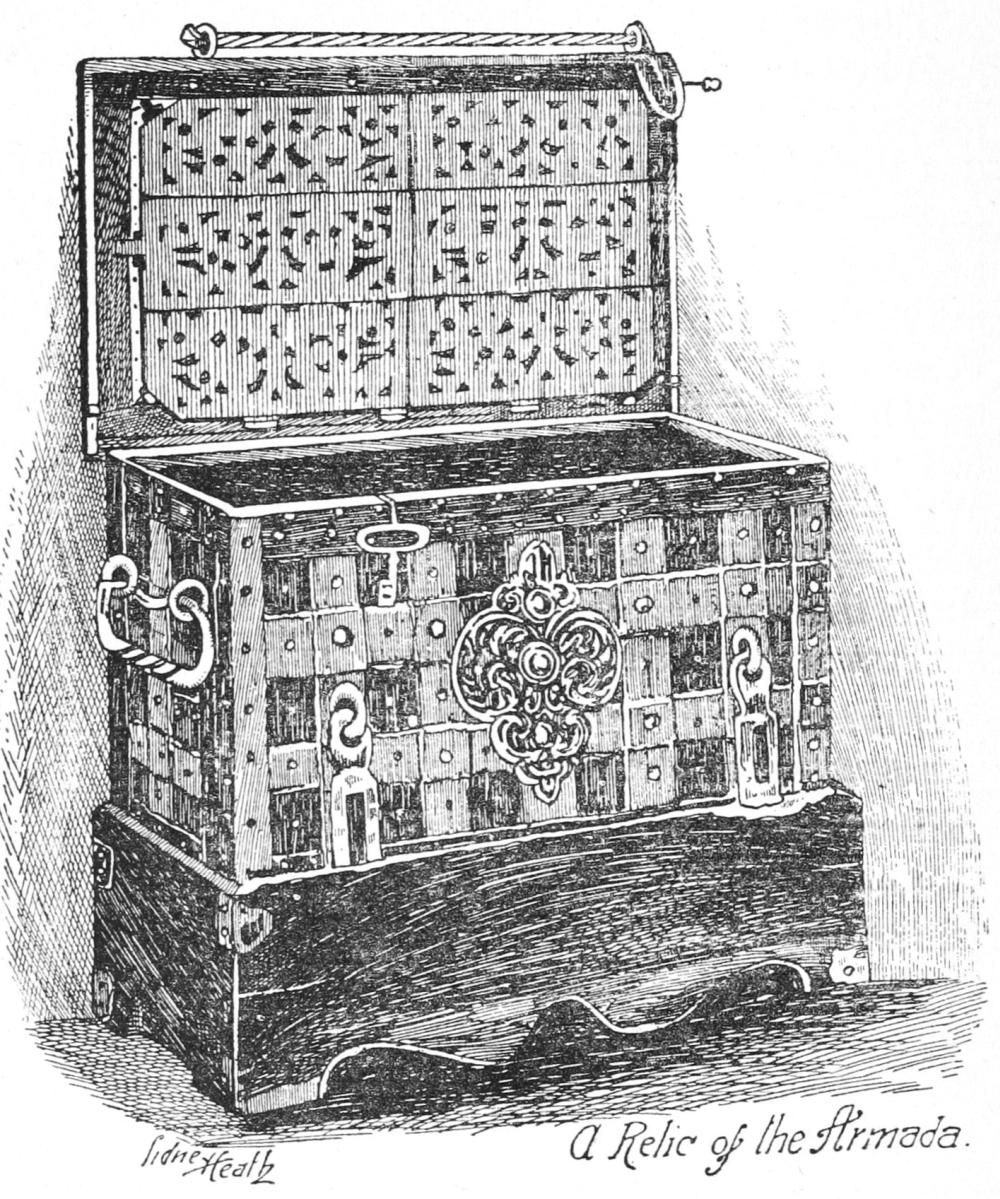

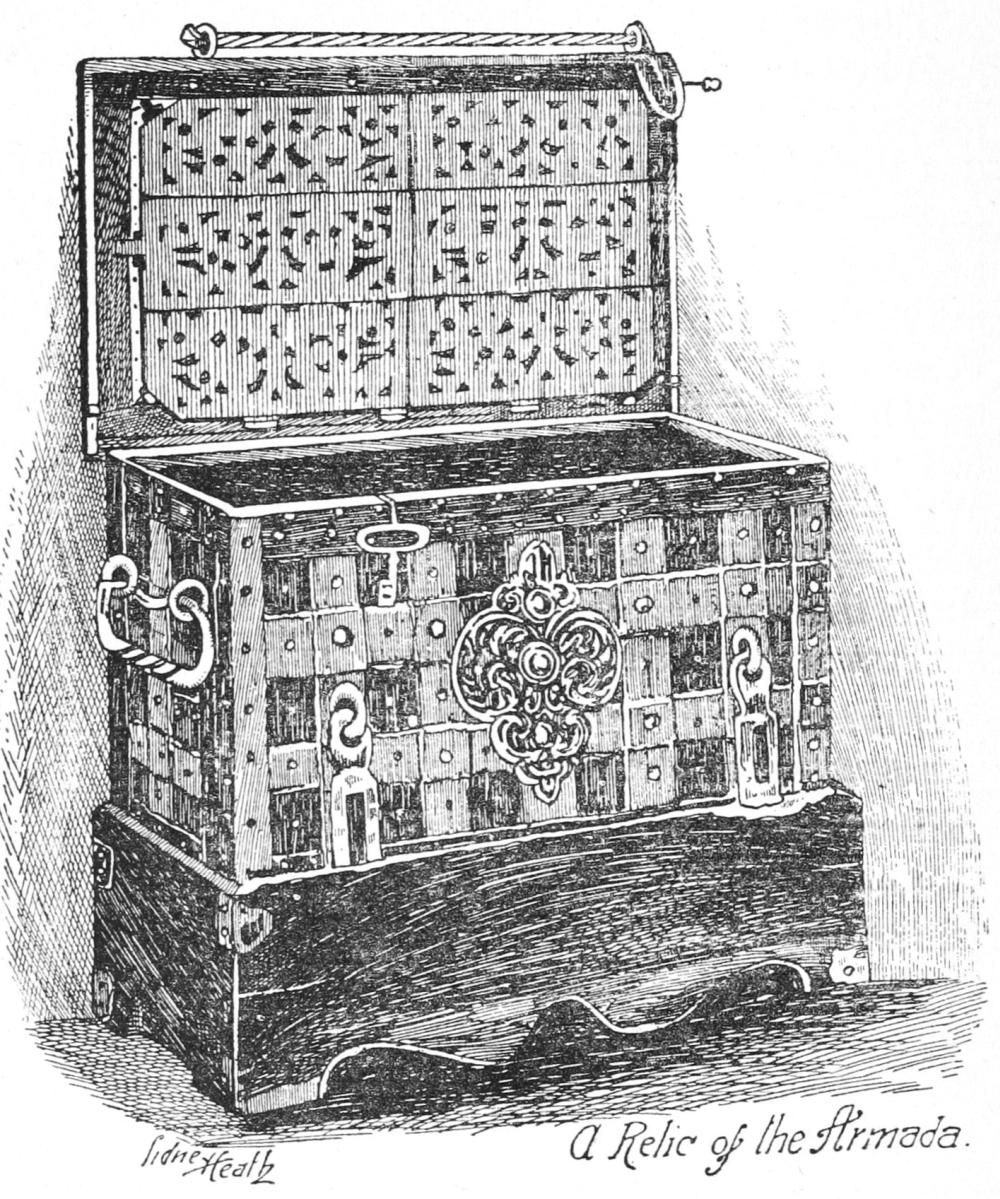

| Chest in the Guildhall, Weymouth |

164 |

| ” ” ” |

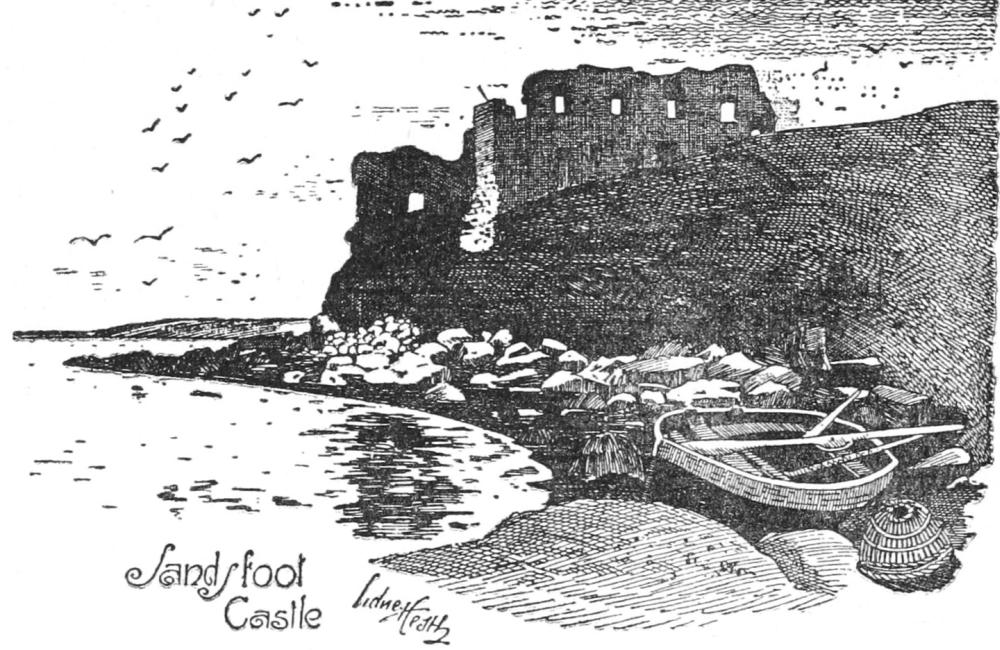

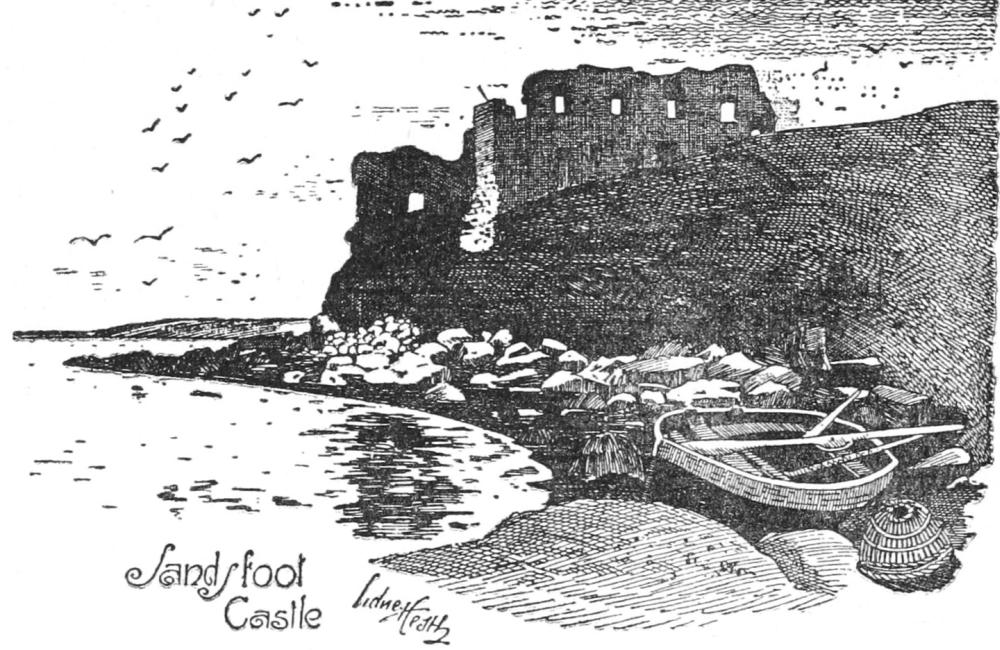

| Sandsfoot Castle, Weymouth |

166 |

| ” ” ” |

| Doorway, Sandsfoot Castle |

167 |

| ” ” ” |

| Some Weymouth Tokens |

169 |

| ” ” ” |

| The Arms of Weymouth |

170 |

| ” ” ” |

| Old House on North Quay, Weymouth |

171 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

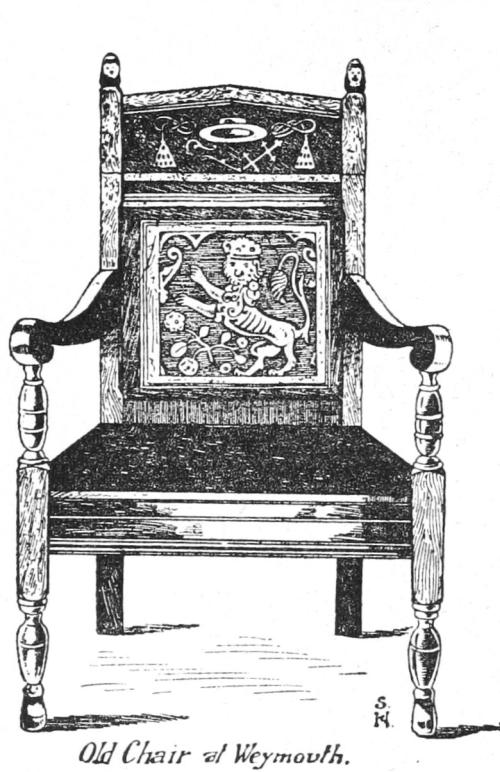

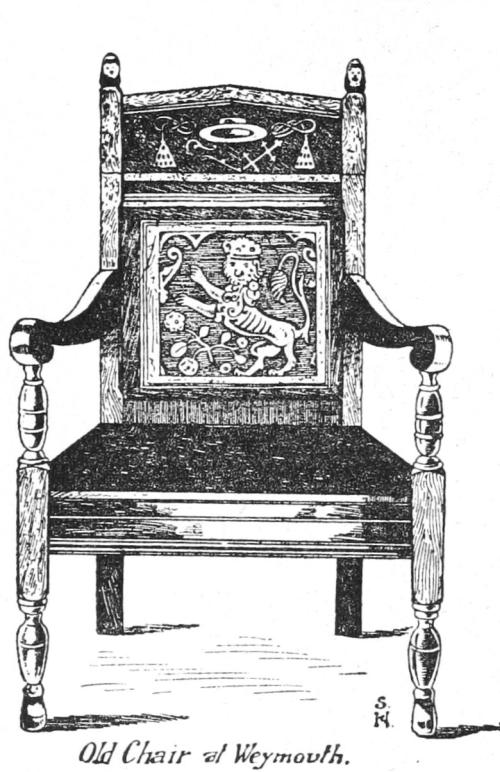

| An Old Chair in the Guildhall, Weymouth |

172 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

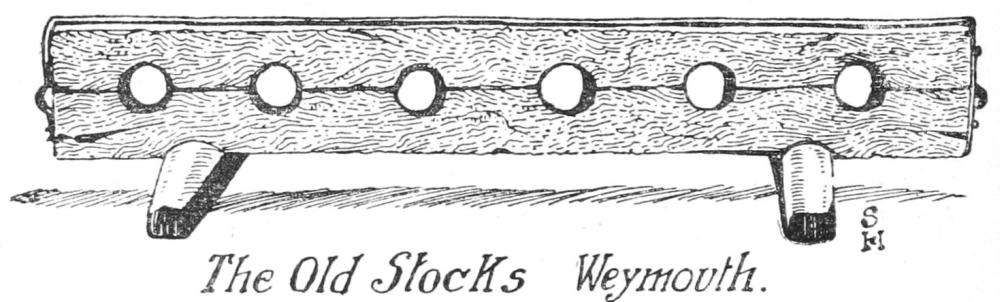

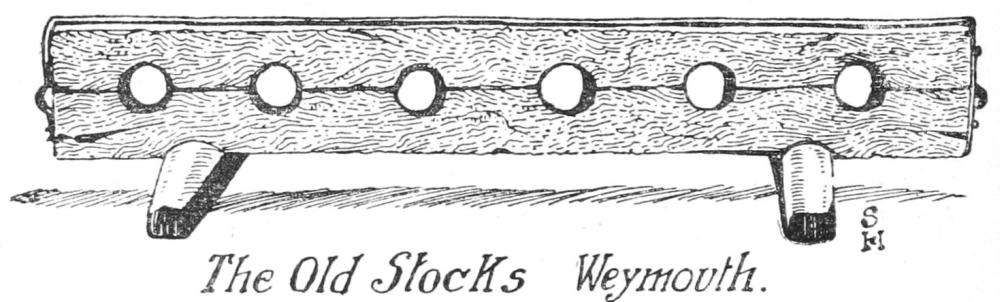

| The Old Stocks, Weymouth |

176 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

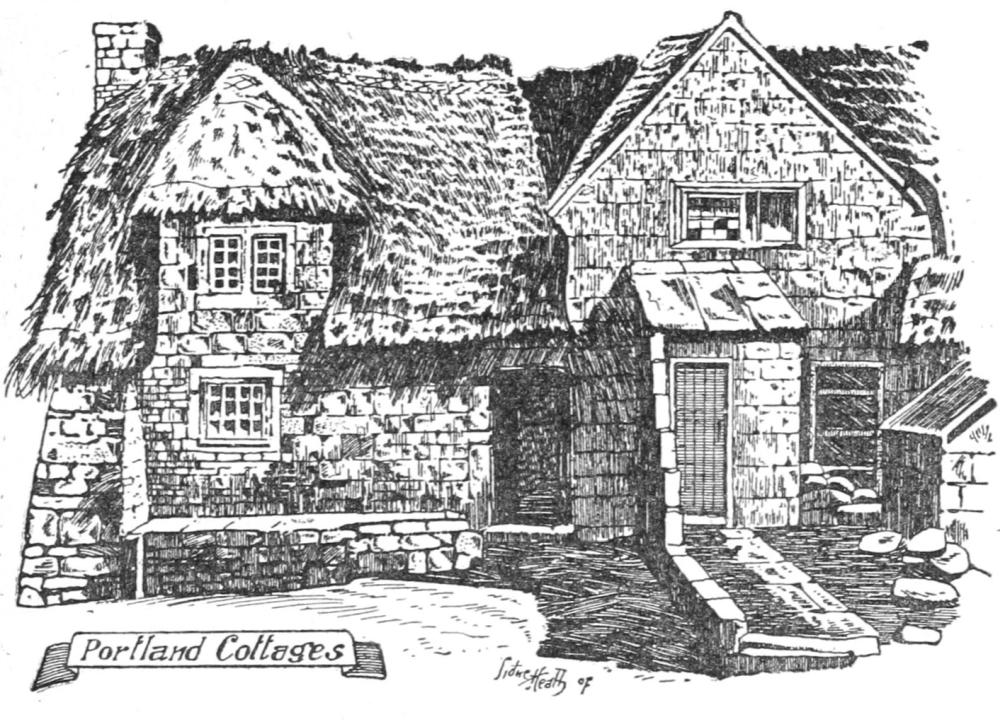

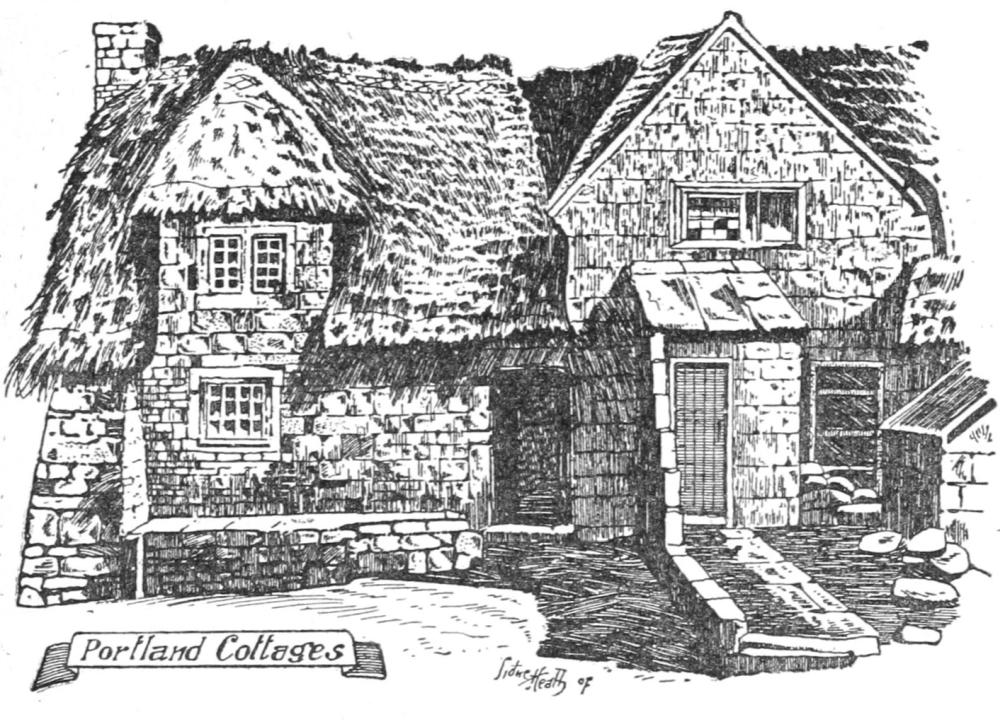

| Portland Cottages |

185 |

| ” ” ” |

| “Kimmeridge Coal Money” |

192 |

| (From a photograph by Mr. A. D. Moullin) |

| Corfe Castle |

200 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

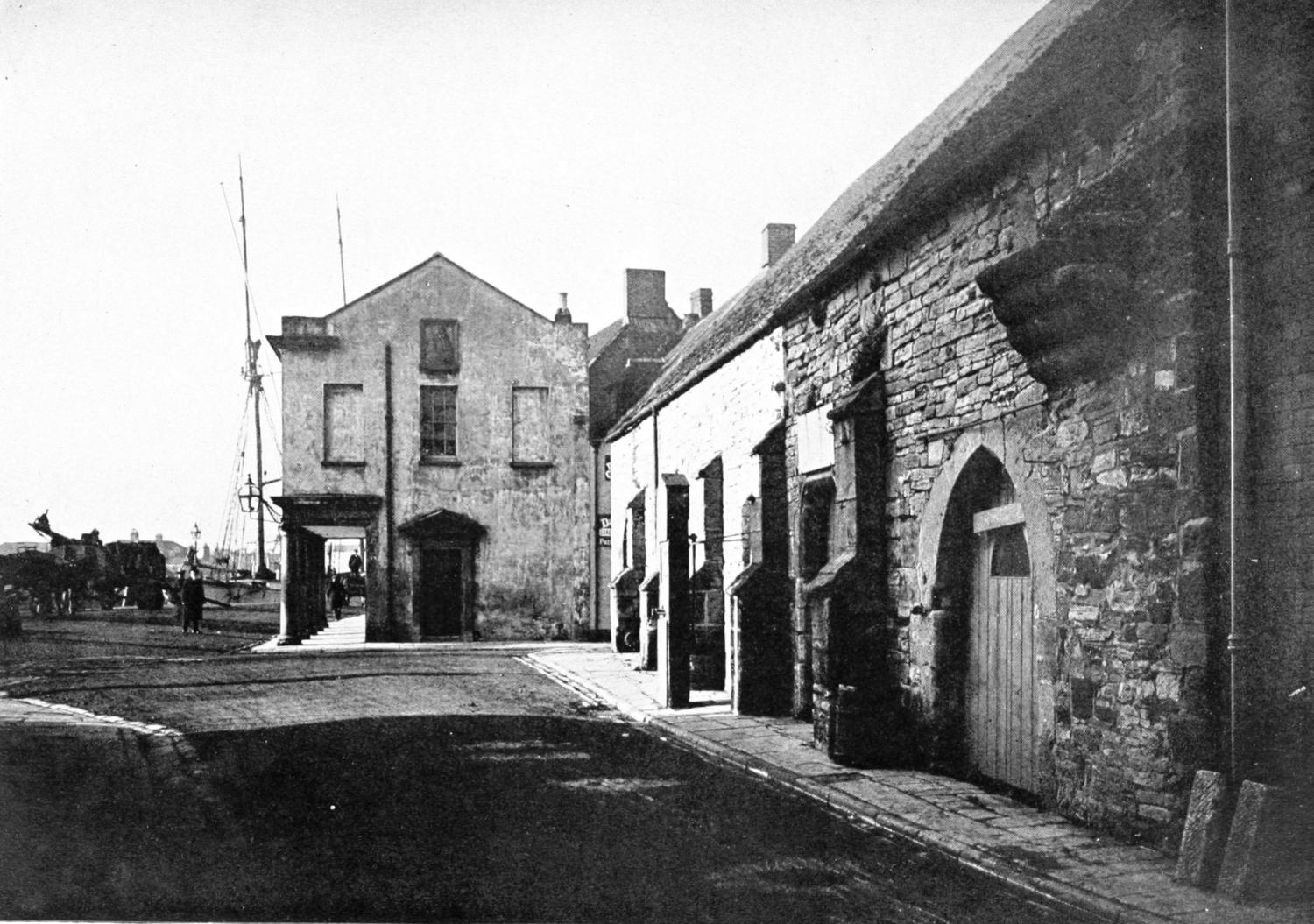

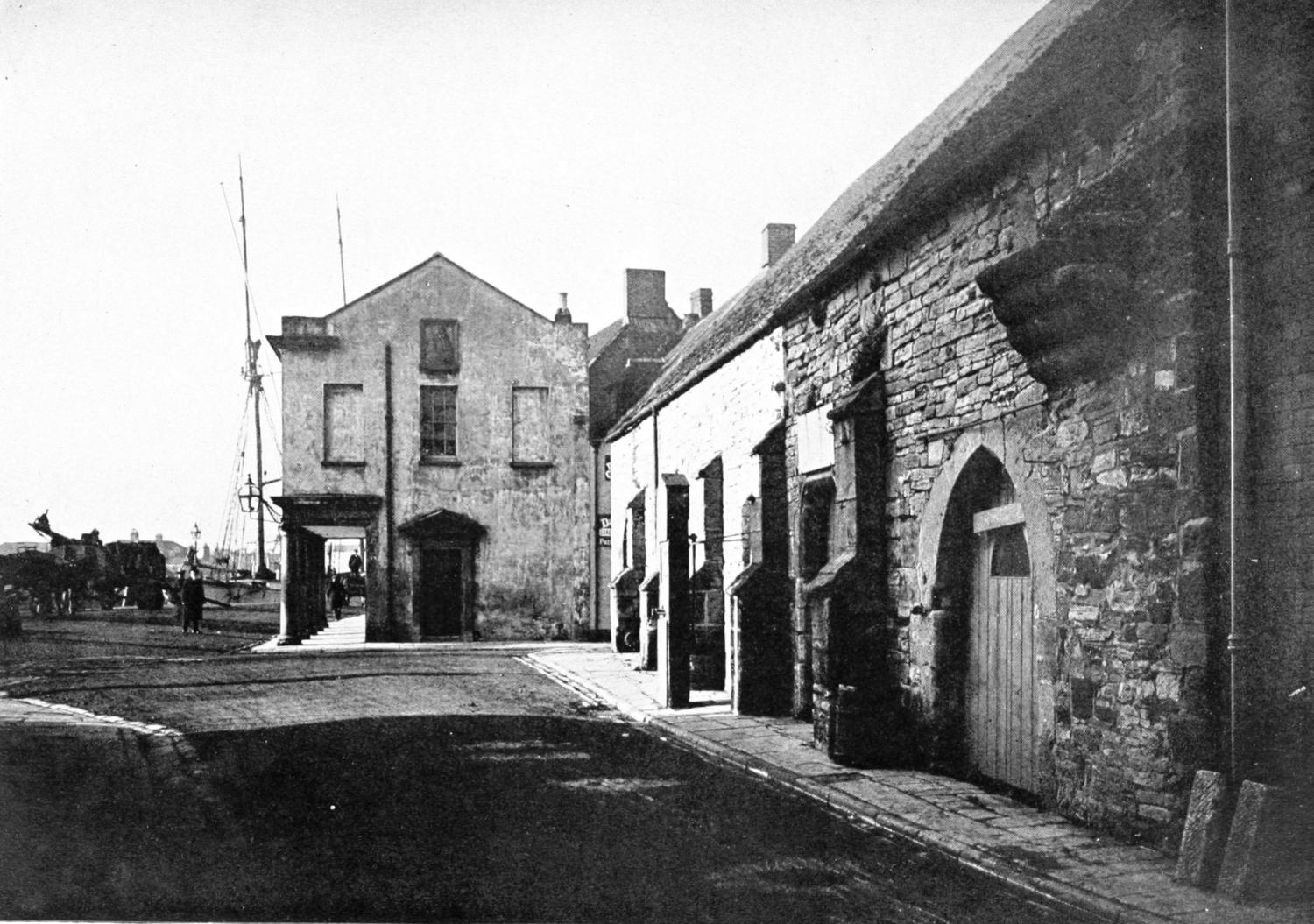

| The Town Cellars, Poole |

222[Pg xv] |

| ” ” ” |

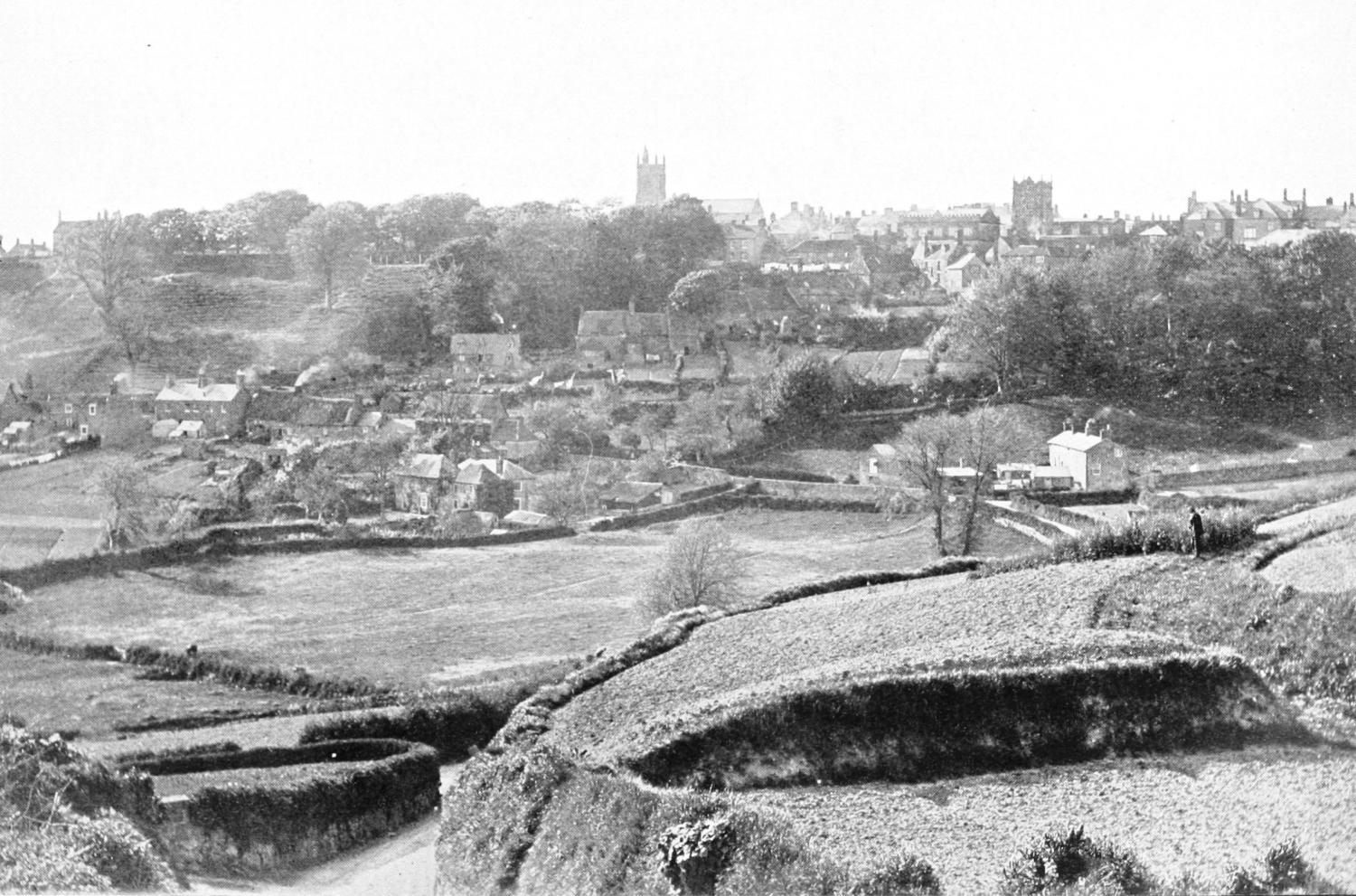

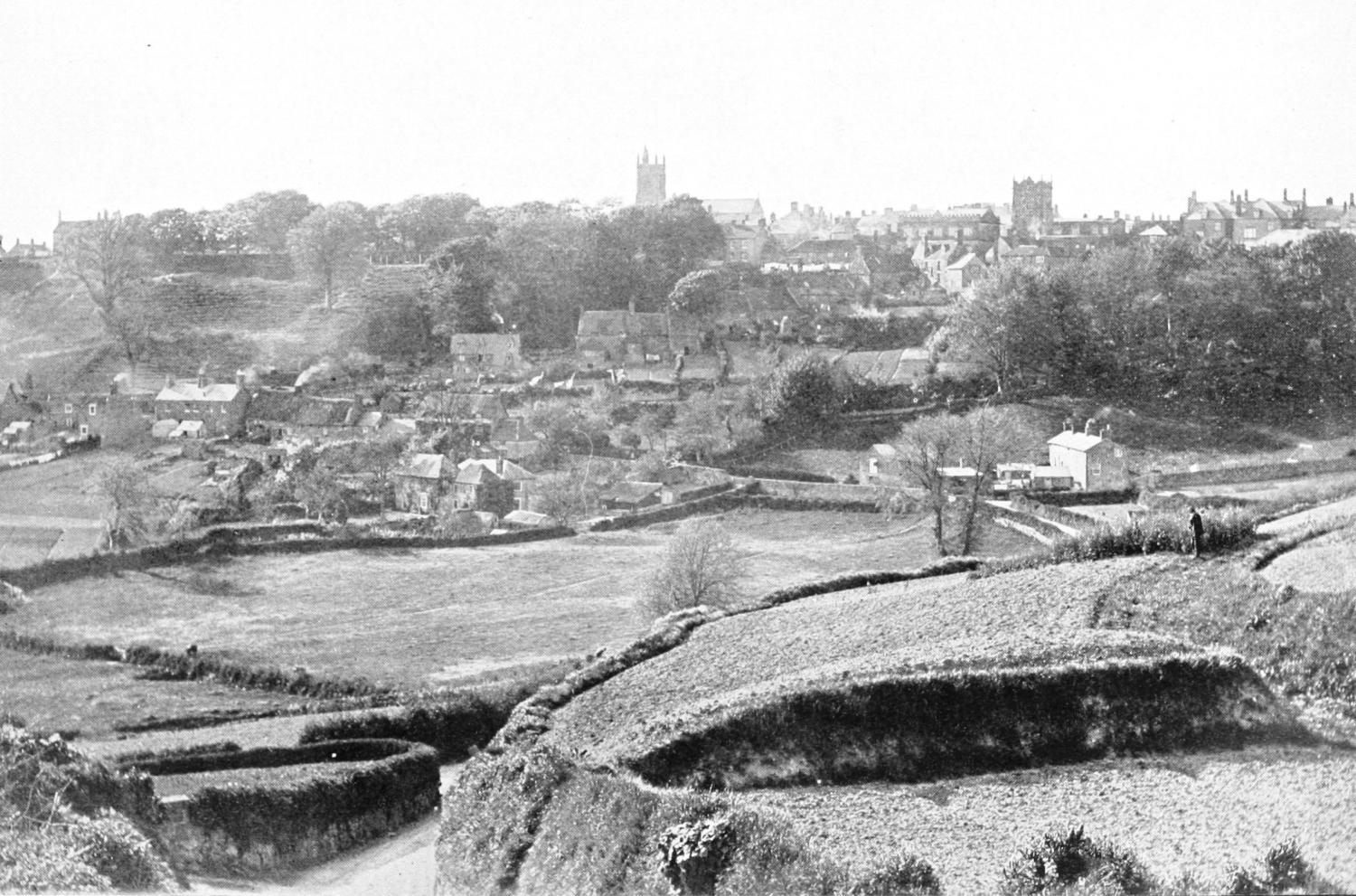

| Shaftesbury |

240 |

| ” ” ” |

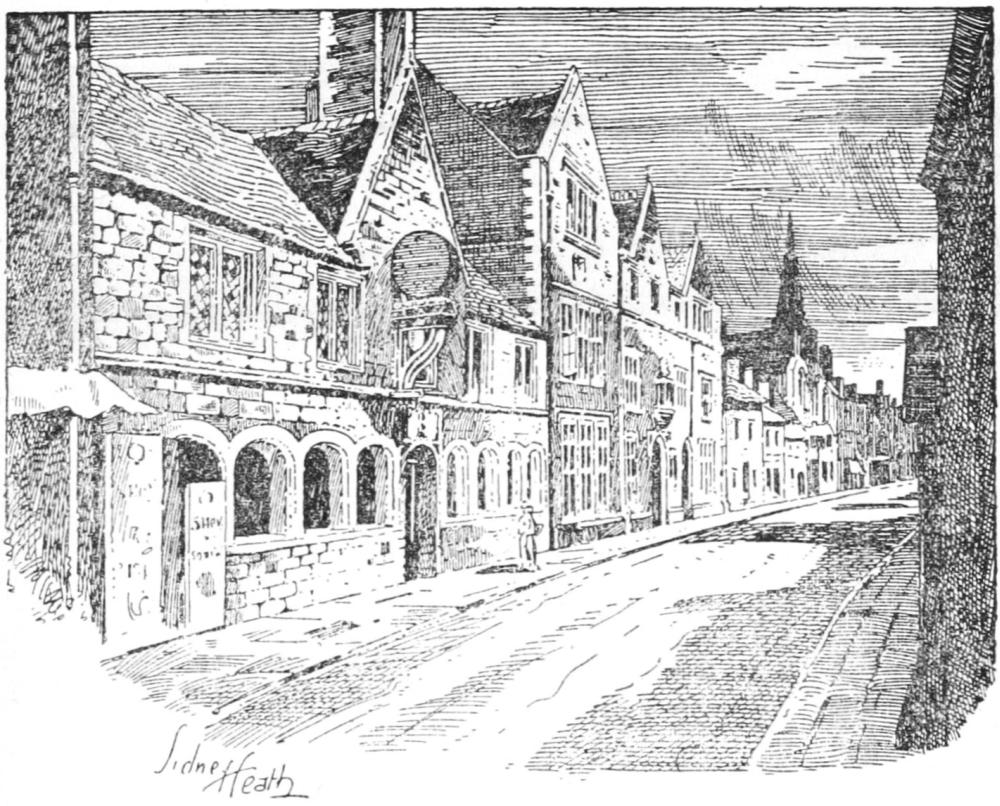

| Gold Hill, Shaftesbury |

248 |

| ” ” ” |

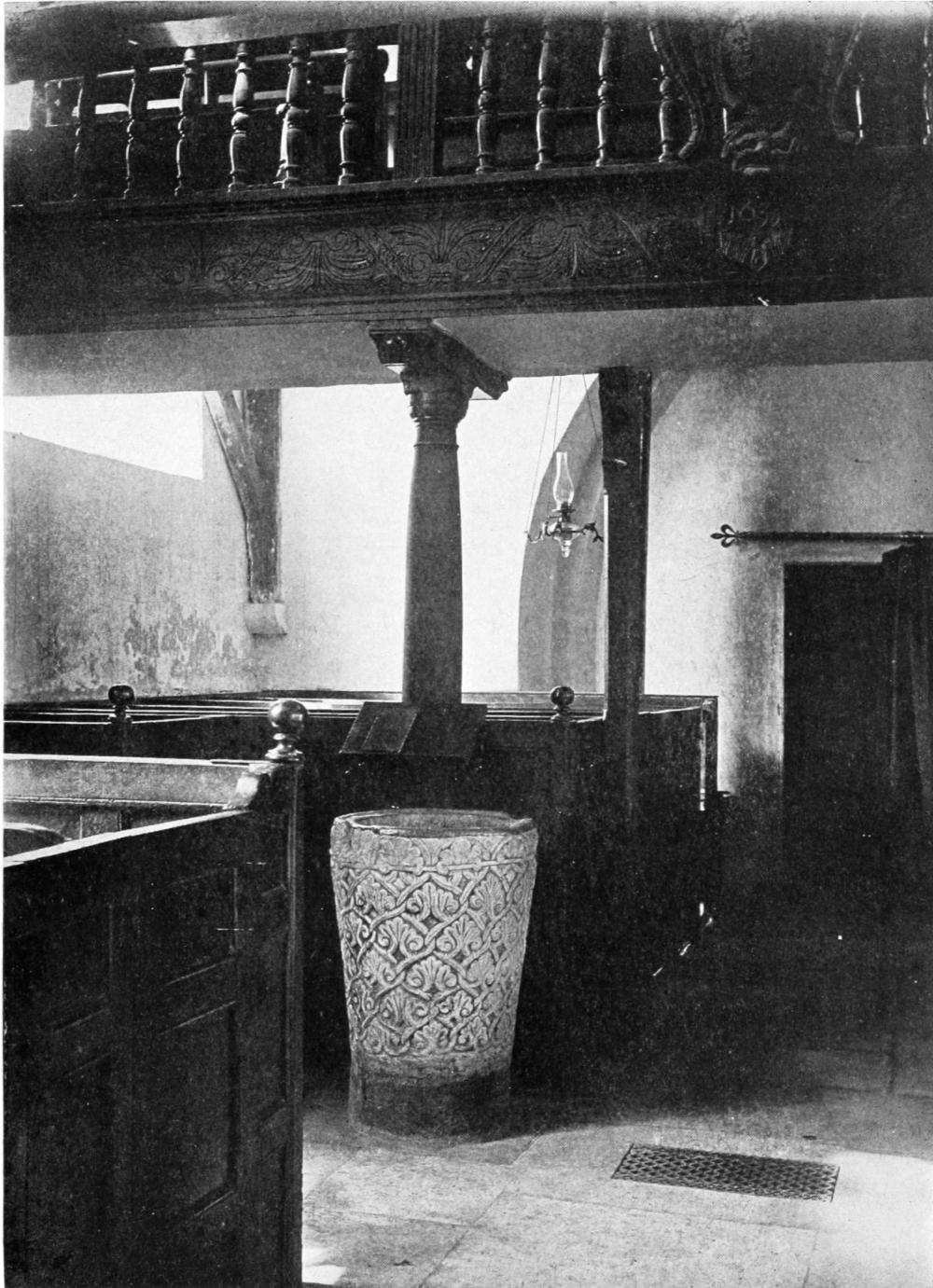

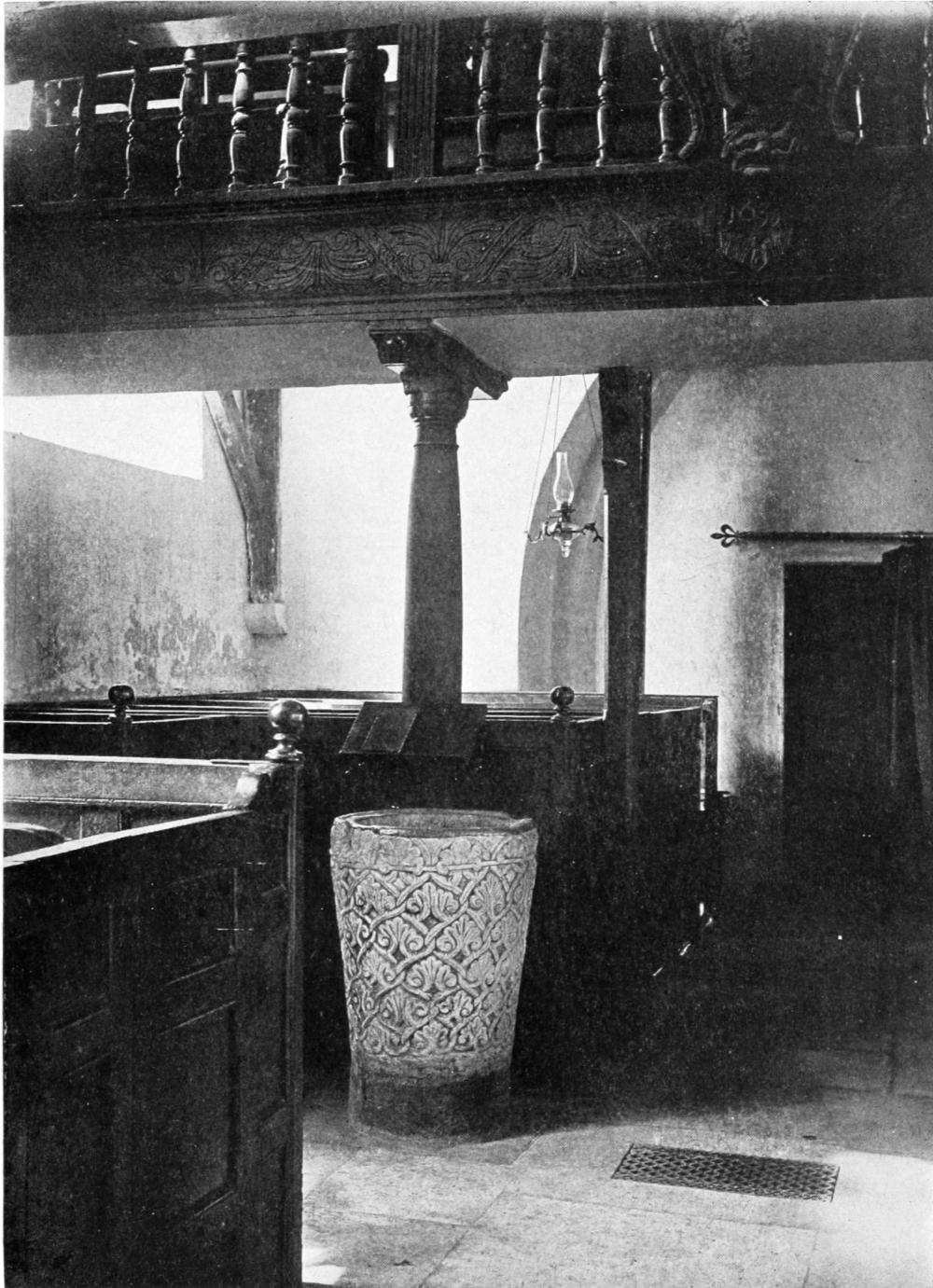

| Piddletown Church |

258 |

| ” ” ” |

| Athelhampton Hall |

262 |

| ” ” ” |

| Wolfeton House |

264 |

| ” ” ” |

| The East Drawing Room, Wolfeton House |

268 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

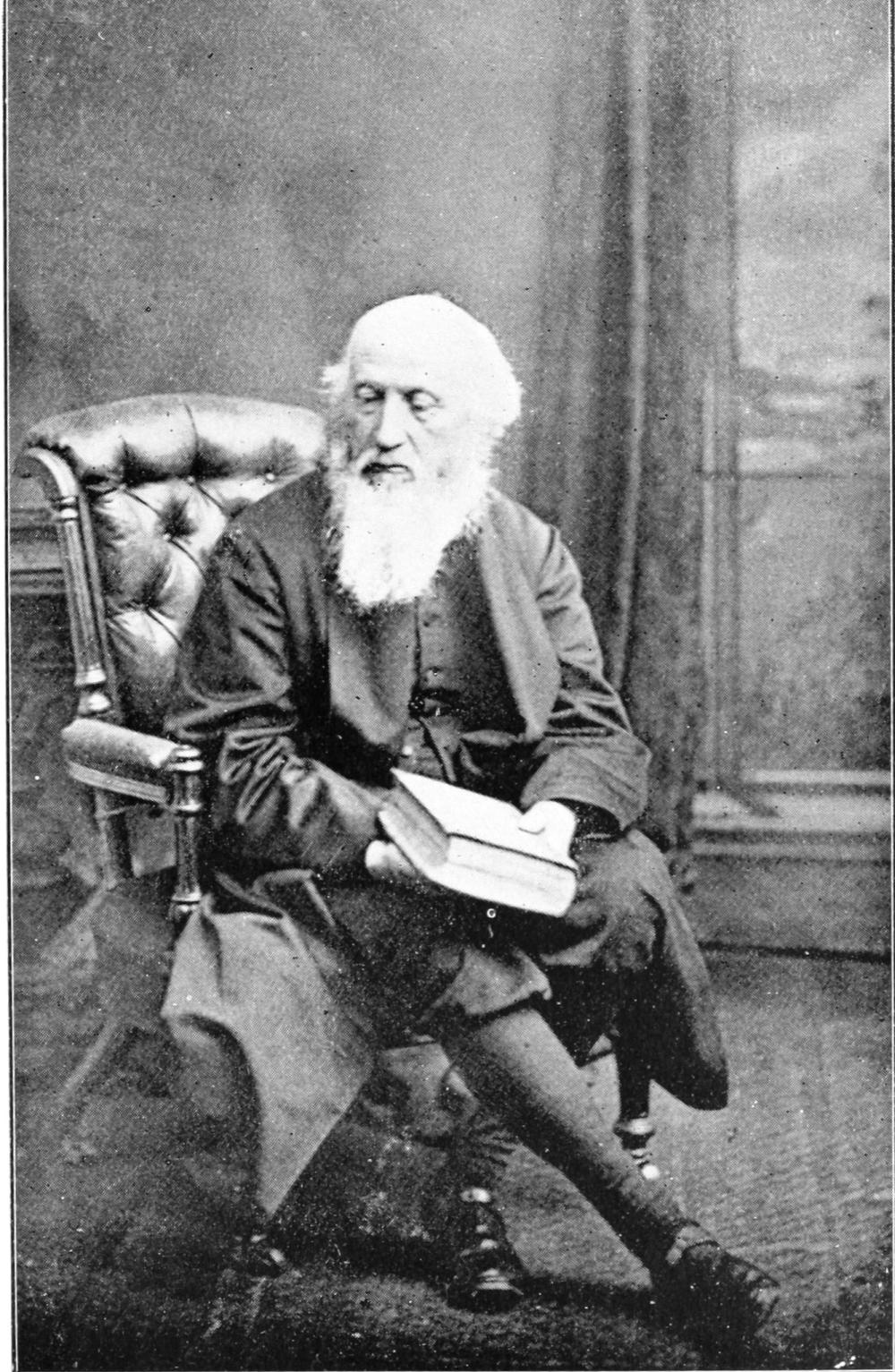

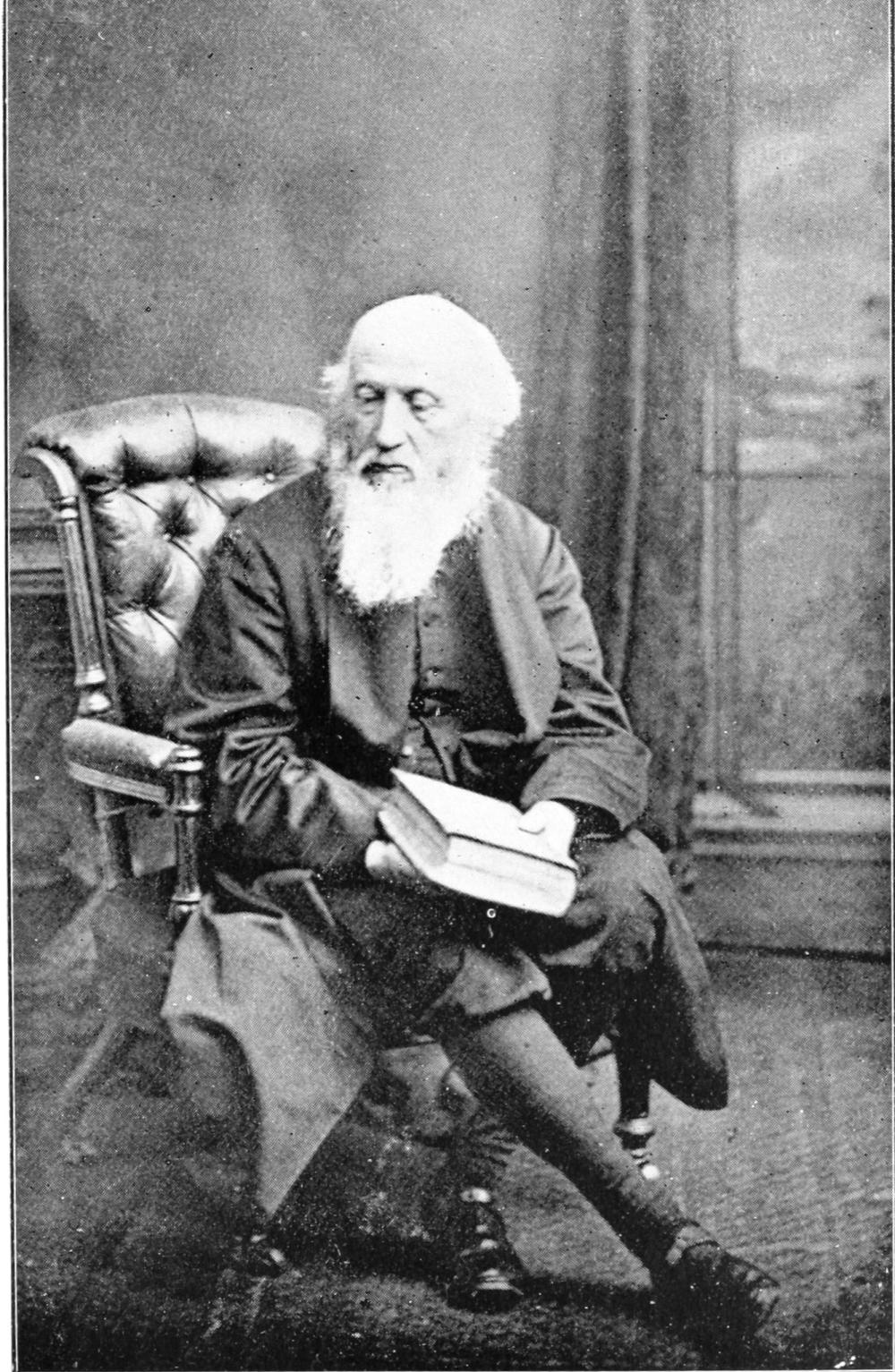

| William Barnes |

280 |

| (From a photograph by Messrs. Dickinsons) |

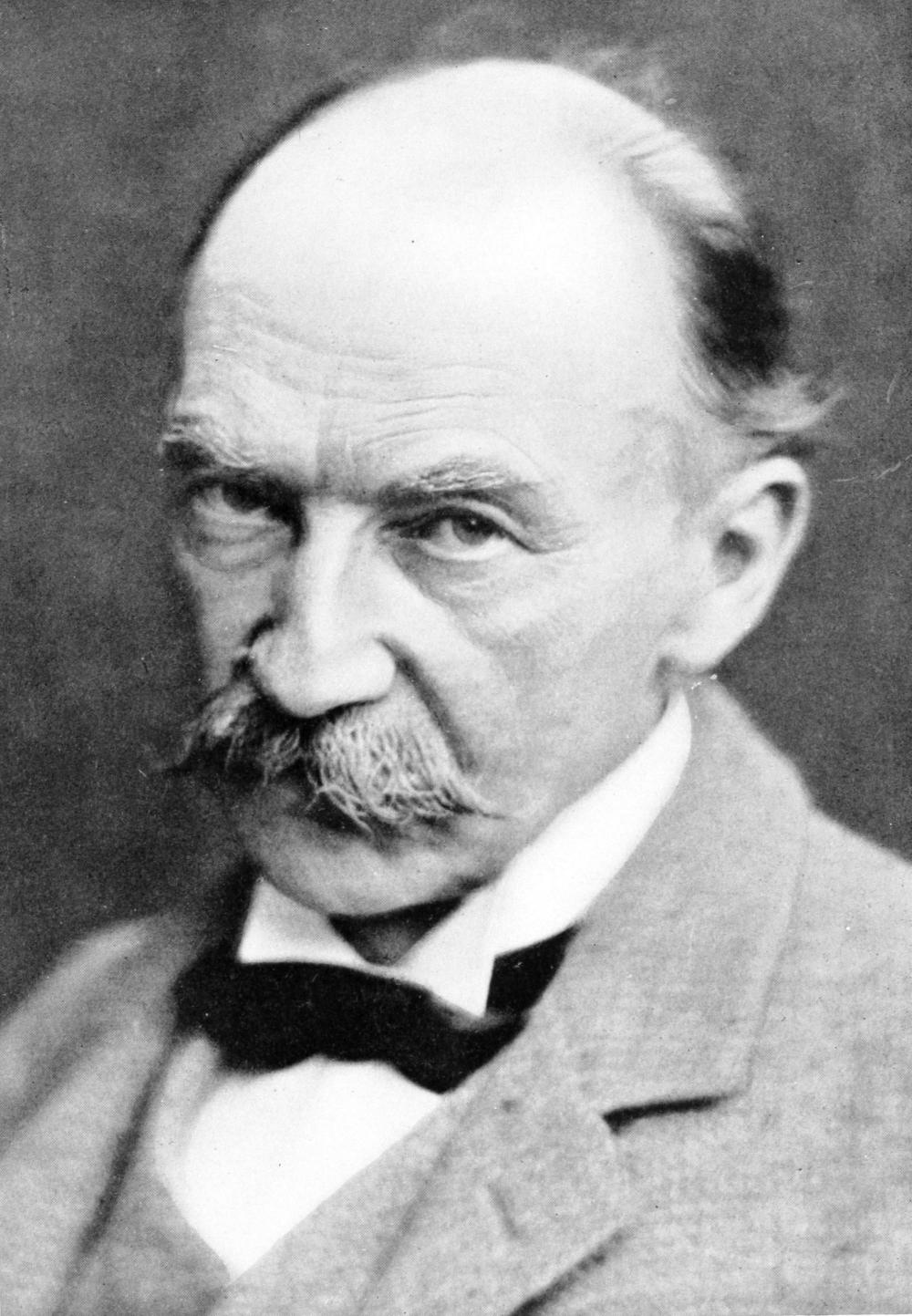

| Thomas Hardy |

284 |

| (From a photograph by the Rev. T. Perkins) |

| Came Rectory |

291 |

| (From a drawing by Mr. Sidney Heath) |

[Pg 1]

HISTORIC DORSET

By the Rev. Thomas Perkins, M.A.

HE physical features due to the geological

formation of the district now called Dorset have

had such an influence on the inhabitants and their

history that it seems necessary to point out

briefly what series of stratified rocks may be seen in

Dorset, and the lines of their outcrop.

There are no igneous rocks, nor any of those classed

as primary, but, beginning with the Rhætic beds, we find

every division of the secondary formations, with the

possible exception of the Lower Greensand, represented,

and in the south-eastern part of the district several of

the tertiary beds may be met with on the surface.

The dip of the strata is generally towards the east;

hence the earlier formations are found in the west.

Nowhere else in England could a traveller in a journey

of a little under fifty miles—which is about the distance

from Lyme to the eastern boundary of Dorset—cross the

outcrop of so many strata. A glance at a geological map

of England will show that the Lias, starting from Lyme

Regis, sweeps along a curve slightly concave towards the

west, almost due north, until it reaches the sea again at

Redcar, while the southern boundary of the chalk starting

within about ten miles of Lyme runs out eastward to

Beechy Head. Hence it is seen that the outcrops of the

various strata are wider the further away they are from

Lyme Regis.

[Pg 2]

Dorset has given names to three well-known formations

and to one less well known: (1) The Portland beds,

first quarried for building stone about 1660; (2) the

Purbeck beds, which supplied the Early English church

builders with marble for their ornamental shafts;

(3) Kimmeridge clay; and (4) the Punfield beds.

The great variety of the formation coming to the

surface in the area under consideration has given a

striking variety to the character of the landscape: the

chalk downs of the North and centre, with their rounded

outlines; the abrupt escarpments of the greensand in the

neighbourhood of Shaftesbury; the rich grazing land of

Blackmore Vale on the Oxford clay; and the great Heath

(Mr. Hardy’s Egdon) stretching from near Dorchester out

to the east across Woolwich, Reading, and Bagshot beds,

with their layers of gravel, sand, and clay. The chalk

heights are destitute of water; the streams and rivers are

those of the level valleys and plains of Oolitic clays—hence

they are slow and shallow, and are not navigable, even

by small craft, far from their mouths.

The only sides from which in early days invaders were

likely to come were the south and east; and both of these

boundaries were well protected by natural defences, the

former by its wall of cliffs and the deadly line of the Chesil

beach. The only opening in the wall was Poole Harbour,

a land-locked bay, across which small craft might indeed

be rowed, but whose shores were no doubt a swamp

entangled by vegetation. Swanage Bay and Lulworth

Cove could have been easily defended. Weymouth Bay

was the most vulnerable point. Dense forests protected

the eastern boundary. These natural defences had a

marked effect, as we shall see, on the history of the people.

Dorset for many centuries was an isolated district, and

is so to a certain extent now, though great changes have

taken place during the last fifty or sixty years, due to the

two railways that carry passengers from the East to

Weymouth and the one that brings them from the North[Pg 3]

to Poole and on to Bournemouth. This isolation has

conduced to the survival not only of old modes of speech,

but also of old customs, modes of thought, and

superstitions.

It may be well, before speaking of this history, to state

that the county with which this volume deals should always

be spoken of as “Dorset,” never as “Dorsetshire”; for

in no sense of the word is Dorset a shire, as will be

explained further on.

We find within the boundaries of the district very few

traces of Palæolithic man: the earliest inhabitants, who

have left well-marked memorials of themselves, were

Iberians, a non-Aryan race, still represented by the

Basques of the Pyrenees and by certain inhabitants of

Wales. They were short of stature, swarthy of skin, dark

of hair, long-skulled. Their characteristic weapon or implement

was a stone axe, ground, not chipped, to a sharp

edge; they buried their dead in a crouching attitude in

the long barrows which are still to be seen in certain parts

of Dorset, chiefly to the north-east of the Stour Valley.

When and how they came into Britain we cannot tell for

certain; it was undoubtedly after the glacial epoch, and

probably at a time when the Straits of Dover had not

come into being and the Thames was still a tributary of

the Rhine. They were in what is known as the Neolithic

stage of civilisation; but in course of time, after this

country had become an island, invaders broke in upon

them, Aryans of the Celtic race, probably (as Professor

Rhys thinks, though he says he is not certain on this

point) of the Goidelic branch. These men were tall, fair-haired,

blue-eyed, round-skulled, and were in a more

advanced stage of civilisation than the Iberians, using

bronze weapons, and burying their dead, sometimes after

cremation, in the round barrows that exist in such large

numbers on the Dorset downs. Their better arms and

greater strength told in the warfare that ensued: whether

the earlier inhabitants were altogether destroyed, or[Pg 4]

expelled or lived on in diminished numbers in a state of

slavery, we have no means of ascertaining. But certain

it is that the Celts became masters of the land. These

men were some of those who are called in school history

books “Ancient Britons”; the Wessex folk in after days

called them “Welsh”—that is, “foreigners”—the word

that in their language answered to βάρβαροι and

“barbari” of the Greeks and Romans. What they called

themselves we do not know. Ptolemy speaks of them as

“Durotriges,” the name by which they were known to the

Romans. Despite various conjectures, the etymology of

this word is uncertain. The land which they inhabited

was, as already pointed out, much isolated. The lofty

cliffs from the entrance to Poole Harbour to Portland

formed a natural defence; beyond this, the long line of

the Chesil beach, and further west, more cliffs right on to

the mouth of the Axe. Most of the lowlands of the interior

were occupied by impenetrable forests, and the slow-running

rivers, which even now in rainy seasons overflow

their banks, and must then, when the rainfall was much

heavier than now, have spread out into swamps, rendered

unnavigable by their thick tangle of vegetation. The

inhabitants dwelt on the sloping sides of the downs,

getting the water they needed from the valleys,

and retiring for safety to the almost innumerable

encampments that crowned the crests of the hills, many of

which remain easily to be distinguished to this day.

Nowhere else in England in an equal area can so many

Celtic earthworks be found as in Dorset. The Romans

came in due course, landing we know not where, and

established themselves in certain towns not far from the

coasts.

The Celts were not slain or driven out of their land,

but lived on together with the Romans, gradually

advancing in civilisation under Roman influence. They

had already adopted the Christian religion: they belonged

to the old British Church, which lived on in the south-west[Pg 5]

of England even through that period when the Teutonic

invaders—Jutes, Angles, Saxons—devastated the south-east,

east, north, and central parts of the island, and utterly

drove westward before them the Celtic Christians into

Wales and the south-west of Scotland. Dorset remained

for some time untouched, for though the Romans had

cleared some of the forests before them, and had cut

roads through others, establishing at intervals along them

military stations, and strengthening and occupying many

of the Celtic camps, yet the vast forest—“Selwood,” as the

English called it—defended Dorset from any attack of the

West Saxons, who had settled further to the east. Once,

and once only, if we venture, with Professor Freeman, to

identify Badbury Rings, near Wimborne, on the Roman

Road, with the Mons Badonicus of Gildas, the Saxons,

under Cerdic, in 516, invaded the land of the Durotriges,

coming along the Roman Road which leads from Salisbury

to Dorchester, through the gap in the forest at

Woodyates, but found that mighty triple ramparted

stronghold held by Celtic Arthur and his knights, round

whom so much that is legendary has gathered, but who

probably were not altogether mythical. In the fight that

followed, the Christian Celt was victorious, and the

Saxon invader was driven in flight back to his own

territory beyond Selwood. Some place Mons

Badonicus in the very north of England, or even in

Scotland, and say that the battle was fought between

the Northumbrians and the North Welsh: if this view

is correct, we may say that no serious attack was

made on the Celts of Dorset from the east.

According to Mr. Wildman’s theory, as stated in his

Life of St. Ealdhelm—which theory has a great air of

probability about it—the Wessex folk, under Cenwealh,

son of Cynegils, the first Christian King of the West

Saxons, won two victories: one at Bradford-on-Avon in

652, and one at the “Hills” in 658. Thus North Dorset

was overcome, and gradually the West Saxons passed on[Pg 6]

westward through Somerset, until in 682 Centwine,

according to the English Chronicle, drove the

Welsh into the sea. William of Malmesbury calls

them “Norht Walæs,” or North Welsh, but this

is absurd: Mr. Wildman thinks “Norht” may be

a mistake for “Dorn,” or “Thorn,” and that the Celts of

Dorset are meant, and that the sea mentioned is the

English Channel. From this time the fate of the

Durotriges was sealed: their land became part of the great

West Saxon kingdom. Well indeed was it for them that

they had remained independent until after the time when

their conquerors had ceased to worship Woden and

Thunder and had given in their allegiance to the White

Christ; for had these men still been worshippers of the

old fierce gods, the Celts would have fared much worse.

Now, instead of being exterminated, they were allowed

to dwell among the West Saxon settlers, in an inferior

position, but yet protected by the West Saxon laws, as we

see from those of Ine who reigned over the West Saxons

from 688 to 728. The Wessex settlers in Dorset were

called by themselves “Dornsæte,” or “Dorsæte,” whence

comes the name of Dorset. It will be seen then, that

Dorset is what Professor Freeman calls a “ga”—the land

in which a certain tribe settled—and differs entirely from

those divisions made after the Mercian land had been won

back from the Danes, when shires were formed by shearing

up the newly recovered land, not into its former divisions

which the Danish conquest had obliterated, but into

convenient portions, each called after the name of the

chief town within its borders, such as Oxfordshire from

Oxford, Leicestershire from Leicester. The Danes

did for a time get possession of the larger part

of Wessex, but it was only for a time: the

boundaries of Dorset were not wiped out, and there

was no need to make any fresh division. So when

we use the name Dorset for the county we use the very

name that it was known by in the seventh century. It[Pg 7]

is also interesting to observe that Dorset has been

Christian from the days of the conversion of the Roman

Empire, that no altars smoked on Dorset soil to Woden,

no temples were built in honour of Thunder, no prayers

were offered to Freya; but it is also worth notice that

the Celtic Christian Church was not ready to amalgamate

with the Wessex Church, which had derived its Christianity

from Papal Rome. However, the Church of the

Conquerors prevailed, and Dorset became not only part

of the West Saxon kingdom, but also of the West Saxon

diocese, under the supervision of a bishop, who at first

had his bishop-stool at Dorchester, not the Dorset town,

but one of the same name on the Thames, not far from

Abingdon. In 705, when Ine was King, it received a

bishop of its own in the person of St. Ealdhelm, Abbot of

Malmesbury, who on his appointment placed his bishop-stool

at Sherborne: he did not live to hold this office

long, for he died in 709. But a line of twenty-five bishops

ruled at Sherborne, the last of whom—Herman, a Fleming

brought over by Eadward the Confessor—transferred his

see in 1075 to Old Sarum, as it is now called; whereupon

the church of Sherborne lost its cathedral rank.

The southern part of Dorset, especially in the neighbourhood

of Poole Harbour, suffered much during the

time that the Danes were harrying the coast of England.

There were fights at sea in Swanage Bay, there were

fights on land round the walls of Wareham, there were

burnings of religious houses at Wimborne and Wareham.

Then followed the victories of Ælfred, and for a time

Dorset had rest. But after Eadward was murdered at

“Corfes-geat” by his stepmother Ælfthryth’s order, and

the weak King Æthelred was crowned, the Danes gave

trouble again. The King first bribed them to land alone;

and afterwards, when, trusting to a treaty he had made

with them, many Danes had settled peacefully in the

country, he gave orders for a general massacre—men,

women and children—on St. Brice’s Day (November 13th),[Pg 8]

1002. Among those who perished was a sister of Swegen,

the Danish King, Christian though she was. This

treacherous and cruel deed brought the old Dane across

the seas in hot haste to take terrible vengeance on the

perpetrator of the dastardly outrage. All southern

England, including Dorset, was soon ablaze with burning

towns. The walls of Dorchester were demolished, the

Abbey of Cerne was pillaged and destroyed, Wareham was

reduced to ashes. Swegen became King, but reigned only

a short time, and his greater son, Cnut, succeeded him.

When he had been recognised as King by the English,

and had got rid of all probable rivals, he governed well and

justly, and the land had rest. Dorset had peace until Harold

had fallen on the hill of Battle, and the south-eastern and

southern parts of England had acknowledged William as

King. The men of the west still remained independent,

Exeter being the chief city to assert its independence.

In 1088 William resolved to set about to subdue these

western rebels, as he called them. He demanded that

they should accept him as King, take oaths of allegiance

to him, and receive him within their walls. To this the

men of Exeter made answer that they would pay tribute

to him as overlord of England as they had paid to the

previous King, but that they would not take oaths of

allegiance, nor would they allow him to enter the city.

William’s answer was an immediate march westward.

Professor Freeman says that there is no record of the

details of his march; but naturally it would lie through

Dorset, the towns of which were in sympathy with Exeter.

Knowing what harsh and cruel things William could do

when it suited his purpose, we cannot for a moment doubt

that he fearfully harried all the Dorset towns on the line

of his march, seeking by severity to them to overawe the

city of Exeter.

In the wars between Stephen and Maud, Dorset was

often the battle-ground of the rival claimants for the

throne. Wareham, unfortunate then, as usual, was taken[Pg 9]

and re-taken more than once, first by one party, then by

the other; but lack of space prevents the telling of this

piece of local history.

King John evidently had a liking for Dorset. He

often visited it, having houses of his own at Bere Regis,

Canford, Corfe, Cranborne, Gillingham, and Dorchester.

In the sixteenth year of his reign he put strong garrisons

into Corfe Castle and Wareham as a defence against his

discontented barons.

In the wars between his son, Henry III., and the

Barons there was fighting again in Dorset, especially at

Corfe. Dorset, among other sea-side counties, supplied

ships and sailors to Edward III. and Henry V. for their

expeditions against France.

The Wars of the Roses seem hardly to have touched

the county; but one incident must be mentioned: On

April 14th, 1471, Margaret, wife of Henry VI., landed at

Weymouth with her son Edward and a small band of

Frenchmen; but she soon heard that on the very day of

her landing her great supporter, though once he had been

her bitterest enemy, Warwick the King-maker, had been

defeated and slain at Barnet. This led her to seek

sanctuary in the Abbey at Cerne, about sixteen miles to

the north of Weymouth; but her restless spirit would not

allow her long to stay in this secluded spot, and she started

with young Edward, gathering supporters as she went,

till on May 4th her army was defeated at Tewkesbury,

and there her last hopes were extinguished when King

Edward IV. smote her son, who had been taken prisoner,

with gauntleted hand upon the mouth, and the daggers

of Clarence and Gloucester ended the poor boy’s life.

We hear nothing of resistance on the part of Dorset

to the Earl of Richmond when he came to overthrow

Richard III. Probably, as the Lancastrian family of the

Beauforts were large landowners in Dorset, Dorset

sympathy was enlisted on the side of the son of the Lady

Margaret, great-granddaughter of John of Gaunt.

[Pg 10]

Like all the rest of England, Dorset had to see its

religious houses suppressed and despoiled; its abbots and

abbesses, with all their subordinate officers, as well as

their monks and nuns, turned out of their old homes,

though let it in fairness be stated, not unprovided for, for

all those who surrendered their ecclesiastical property to

the King received pensions sufficient to keep them in

moderate comfort, if not in affluence. Dorset accepted

the dissolution of the monasteries and the new services

without any manifest dissatisfaction. There was no

rioting or fighting as in the neighbouring county of

Devon.

Dorset did not escape so easily in the days of the Civil

War. Lyme, holden for the Parliament by Governor

Creely and some 500 men, held out from April 20th to

June 16th, 1644, against Prince Maurice with 4,000 men,

when the Earl of Essex came to its relief. Corfe Castle

and Sherborne Castle were each besieged twice. Abbotsbury

was taken by Sir Anthony Ashley Cooper in

September, 1644. Wareham, also, was more than once

the scene of fighting. In the north of Dorset a band of

about 5,000 rustics, known as “Clubmen,” assembled.

These men knew little and cared less for the rival causes

of King and Parliament which divided the rest of

England; but one thing they did know and greatly cared

for: they found that ever and again bands of armed horsemen

came riding through the villages, some singing

rollicking songs and with oaths on their lips, others

chanting psalms and quoting the Bible, but all alike

treading down their crops, demanding food, and sometimes

their horses, often forgetting to pay for them; so they

resolved to arm themselves and keep off Cavaliers and

Roundheads alike. At one time they encamped at

Shaftesbury, but could not keep the Roundheads

from occupying the Hill Town; so they, to the number of

4,000, betook themselves to the old Celtic camp of

Hambledon, some seven or eight miles to the south.[Pg 11]

Cromwell himself, in a letter to Fairfax, dated August 4th,

1645, tells what befell them there:

We marched on to Shaftesbury, when we heard a great body of them

was drawn up together about Hambledon Hill. I sent up a forlorn hope

of about 50 horse, who coming very civilly to them, they fired upon

them; and ours desiring some of them to come to me were refused with

disdain. They were drawn into one of the old camps upon a very high

hill. They refused to submit, and fired at us. I sent a second time

to let them know that if they would lay down their arms no wrong should

be done them. They still—through the animation of their leaders, and

especially two vile ministers[1]—refused. When we came near they let

fly at us, killed about two of our men, and at least four horses. The

passage not being for above three abreast kept us out, whereupon Major

Desborow wheeled about, got in the rear of them, beat them from the

work, and did some small execution upon them, I believe killed not

twelve of them, but cut very many, and put them all to flight. We have

taken about 300, many of whom are poor silly creatures, whom, if you

please to let me send home, they promise to be very dutiful for time

to come, and will be hanged before they come out again.

From which we see that “Grim old Oliver,” who could be

severe enough when policy demanded it, yet could show

mercy at times, for throughout this episode his dealings

with the Clubmen were marked with much forbearance.

Charles II., after his defeat at Worcester, September

3rd, 1651, during his romantic wanderings and hidings

before he could get safe to sea, spent nearly three weeks

in what is now Dorset, though most of the time he was

in concealment at the Manor House at Trent, which was

then within the boundaries of Somerset, having only

recently been transferred to Dorset. This manor house

belonged to Colonel Francis Wyndham. Hither on

Wednesday, September 17th, came Jane Lane, sister of

Colonel Lane, from whose house at Bentley, Worcestershire,

she had ridden on a pillion behind one who passed

as her groom, really Charles in disguise, with one

attendant, Cornet Lassels. Jane and the Cornet left Trent

the next day on their return journey, and Charles was[Pg 12]

stowed away in Lady Wyndham’s room, from which there

was access to a hiding-place between two floors. His

object was to effect his escape from one of the small

Dorset ports. Colonel Wyndham rode next day to

Melbury Sampford, where lived Sir John Strangways, to

see if either of his sons could manage to hire a boat at

Lyme, Weymouth, or Poole, which would take Charles to

France. He failed in this, but brought back one hundred

pounds, the gift of Sir John Strangways. Colonel

Wyndham then went to Lyme to see one Captain Ellesdon,

to whom he said that Lord Wilmot wanted to be taken

across to France. Arrangements were then made with

Stephen Limbrey, the skipper of a coasting vessel, to take

a party of three or four royalist gentlemen to France from

Charmouth. Lord Wilmot was described as a Mr. Payne,

a bankrupt merchant running away from his creditors,

and taking his servant (Charles) with him. It was agreed

that Limbrey should have a rowing-boat ready on Charmouth

beach on the night of September 22nd, when the

tide was high, to convey the party to his ship and carry

them safe to France, for which service he was to receive

£60. September 22nd was “fair day” at Lyme, and as

many people would probably be about, it was necessary

that the party should find some safe lodging where they

could wait quietly till the tide was in, about midnight.

Rooms were secured, as for a runaway couple, at a small

inn at Charmouth. At this inn on Monday morning

arrived Colonel Wyndham, who acted as guide, and his

wife and niece, a Mrs. Juliana Coningsby (the supposed

eloping damsel), riding behind her groom (Charles). Lord

Wilmot, the supposed bridegroom, with Colonel

Wyndham’s confidential servant, Peters, followed.

Towards midnight Wyndham and Peters went down to

the beach, Wilmot and Charles waiting at the inn ready

to be called as soon as the boat should come. But no

signs of the boat appeared throughout the whole night.

It seems that Mrs. Limbrey had seen posted up at Lyme[Pg 13]

a notice about the heavy penalty that anyone would

incur who helped Charles Stuart to escape, and

suspecting that the mysterious enterprise on which her

husband was engaged might have something to do with

helping in such an escape, she, when he came back in the

evening to get some things he had need of for the voyage,

locked him in his room and would not let him out; and

he dared not break out lest the noise and his wife’s violent

words might attract attention and the matter get noised

abroad. Charles, by Wyndham’s advice, rode off to

Bridport the next morning with Mistress Coningsby, as

before, the Colonel going with them; Wilmot stayed

behind. His horse cast a shoe, and Peters took it to the

smith to have another put on; and the smith, examining

the horse’s feet, said: “These three remaining shoes were

put on in three different counties, and one looks like a

Worcester shoe.” When the shoe was fixed, the smith

went to a Puritan minister, one Bartholomew Wesley, and

told him what he suspected. Wesley went to the landlady

of the inn: “Why, Margaret,” said he, “you are now a

maid of honour.” “What do you mean by that, Mr.

Parson?” said she. “Why, Charles Stuart lay at your

house last night, and kissed you at his departure, so that

you cannot now but be a maid of honour.” Whereupon

the hostess waxed wroth, and told Wesley that he was an

ill-conditioned man to try and bring her and her house

into trouble; but, with a touch of female vanity, she

added: “If I thought it was the King, as you say it was,

I should think the better of my lips all the days of my

life. So, Mr. Parson, get you out of my house, or I’ll get

those who shall kick you out.”

However, the matter soon got abroad, and a pursuit

began. Meanwhile, Charles and his party had pressed on

into Bridport, which happened to be full of soldiers

mustering there before joining a projected expedition

to capture the Channel Islands for the Parliament.

Charles’s presence of mind saved him. He pushed through[Pg 14]

the crowd into the inn yard, groomed the horse, chatted

with the soldiers, who had no suspicion that he was other

than he seemed, and then said that he must go and serve

his mistress at table. By this time Wilmot and Peters

had arrived, and they told him of the incident at the

shoeing forge; so, losing no time, the party started on

the Dorchester road, but, turning off into a by-lane, got

safe to Broadwinsor, and thence once more to Trent,

which they reached on September 24th. On October 5th

Wilmot and Charles left Trent and made their way to

Shoreham in Sussex. But they had not quite done with

Dorset yet; for it was a Dorset skipper, one Tattersal,

whose business it was to sail a collier brig, The Surprise,

between Poole and Shoreham, who carried Charles Stuart

and Lord Wilmot from Shoreham to Fécamp, and

received the £60 that poor Limbrey might have had save

for his wife’s interference.

Dorset was the stage on which were acted the first and

one of the concluding scenes of the Duke of Monmouth’s

rebellion in 1685. On June 11th the inhabitants of Lyme

Regis were sorely perplexed when they saw three foreign-looking

ships, which bore no colours, at anchor in the bay;

and their anxiety was not lessened when they saw the

custom house officers, who had rowed out, as their habit

was, to overhaul the cargo of any vessel arriving at the

port, reach the vessels but return not again. Then from

seven boats landed some eighty armed men, whose leader

knelt down on the shore to offer up thanksgiving for his

safe voyage, and to pray for God’s blessing on his enterprise.

When it was known that this leader was the Duke

of Monmouth the people welcomed him, his blue flag was

set up in the market place, and Monmouth’s undignified

Declaration—the composition of Ferguson—was read.

That same evening the Mayor, who approved of none of

these things, set off to rouse the West in the King’s favour,

and from Honiton sent a letter giving information of the

landing. On June 14th, the first blood was shed in a[Pg 15]

skirmish near Bridport (it was not a decisive engagement).

Monmouth’s men, however, came back to Lyme, the

infantry in good order, the cavalry helter-skelter; and

little wonder, seeing that the horses, most of them taken

from the plough, had never before heard the sound of firearms.

Then Monmouth and his men pass off our stage. It

is not for the local Dorset historian to trace his marches

up and down Somerset, or to describe the battle that was

fought in the early hours of the morning of July 6th under

the light of the full moon, amid the sheet of thick mist,

which clung like a pall over the swampy surface of the level

stretch of Sedgemoor. Once again Dorset received

Monmouth, no longer at the head of an enthusiastic and

brave, though a badly armed and undisciplined multitude,

but a lonely, hungry, haggard, heartbroken fugitive. On

the morning of July 8th he was found in a field near

Horton, which still bears the name of Monmouth’s Close,

hiding in a ditch. He was brought before Anthony

Etricke of Holt, the Recorder of Poole, and by him sent

under escort to London, there to meet his ghastly end on

Tower Hill, and to be laid to rest in what Macaulay calls

the saddest spot on earth, St. Peter’s in the Tower, the

last resting-place of the unsuccessfully ambitious, of those

guilty of treason, and also of some whose only fault it

was that they were too near akin to a fallen dynasty,

and so roused the fears and jealousy of the reigning

monarch.

Everyone has heard of the Bloody Assize which

followed, but the names and the number of those who

perished were not accurately known till a manuscript of

forty-seven pages, of folio size, was offered for sale among

a mass of waste paper in an auction room at Dorchester,

December, 1875.[2] It was bought by Mr. W. B. Barrett,[Pg 16]

and he found that it was a copy of the presentment of

rebels at the Autumn Assizes of 1685, probably made for

the use of some official of the Assize Court, as no doubt

the list that Jeffreys had would have been written on

parchment, and this was on paper. It gives the names

of 2,611 persons presented at Dorchester, Exeter, and

Taunton, as having been implicated in the rebellion, the

parishes where they lived, and the nature of their callings.

Of these, 312 were charged at Dorchester, and only about

one-sixth escaped punishment. Seventy-four were

executed, 175 were transported, nine were whipped or

fined, and 54 were acquitted or were not captured. It is

worth notice that the percentage of those punished at

Exeter and Taunton was far less than at Dorchester.

Out of 488 charged at Exeter, 455 escaped; and at

Taunton, out of 1,811, 1,378 did not suffer. It is possible

that the Devon and Somerset rebels, having heard of

Jeffreys’ severity at Dorchester, found means of escape.

No doubt many of the country folk who had not

sympathized with the rebellion would yet help to conceal

those who were suspected, when they knew (from what

had happened at Dorchester) that if they were taken they

would in all probability be condemned to death or slavery—for

those “transported” were really handed over to

Court favourites as slaves for work on their West Indian

plantations. It is gratifying to know that it has been

discovered, since Macaulay’s time, that such of the transported

as were living when William and Mary came to the

throne were pardoned and set at liberty on the application

of Sir William Young.

Monmouth was the last invader to land in Dorset;

but there was in the early part of the nineteenth century

very great fear among the Dorset folk that a far more

formidable enemy might choose some spot, probably

Weymouth, on the Dorset coast for landing his army.

Along the heights of the Dorset downs they built beacons

of dry stubs and furze, with guards in attendance,[Pg 17]

ready to flash the news of Napoleon’s landing, should he

land. The general excitement that prevailed, the false

rumours that from time to time made the peaceable

inhabitants, women and children, flee inland, and sent the

men capable of bearing arms flocking seaward, are well

described in Mr. Hardy’s Trumpet Major. But Napoleon

never came, and the dread of invasion passed away for

ever in 1805.

In the wild October night time, when the wind raved round the land,

And the back-sea met the front-sea, and our doors were blocked with sand,

And we heard the drub of Dead-man’s Bay, where bones of thousands are,

(But) knew not what that day had done for us at Trafalgar.

[3]

The isolation of Dorset, which has been before spoken

of, has had much to do with preserving from extinction

the old dialect spoken in the days of the Wessex

kings. Within its boundaries, especially in “outstep

placen,” as the people call them, the old speech may be

heard in comparative purity. Let it not be supposed that

Dorset is an illiterate corruption of literary English. It is

an older form of English; it possesses many words that

elsewhere have become obsolete, and a grammar with rules

as precise as those of any recognised language. No one

not to the manner born can successfully imitate the speech

of the rustics who, from father to son, through many

generations have lived in the same village. A stranger

may pick up a few Dorset words, only, in all probability,

to use them incorrectly. For instance, he may hear the

expression “thic tree” for “that tree,” and go away with

the idea that “thic” is the Dorset equivalent of “that,”

and so say “thic grass”—an expression which no true

son of the Dorset soil would use; for, as the late William

Barnes pointed out, things in Dorset are of two classes:

(1) The personal class of formed things, as a man, a tree,[Pg 18]

a boot; (2) the impersonal class of unformed quantities of

things, as a quantity of hair, or wood, or water. “He”

is the personal pronoun for class (1); “it” for class (2).

Similarly, “thëase” and “thic” are the demonstratives of

class (1); “this” and “that” of class (2). A book is

“he”; some water is “it.” We say in Dorset: “Thëase

tree by this water,” “Thic cow in that grass.” Again,

a curious distinction is made in the infinitive mood: when

it is not followed by an object, it ends in “y”; when an

object follows, the “y” is omitted:—“Can you mowy?”

but “Can you mow this grass for me?” The common

use of “do” and “did” as auxiliary verbs, and not only

when emphasis is intended, is noteworthy (the

“o” of the “do” being faintly heard). “How

do you manage about threading your needles?”

asked a lady of an old woman engaged in sewing, whose

sight was very dim from cataract. The answer came:

“Oh, he” (her husband) “dô dread ’em for me.” In

Dorset we say not only “to-day” and “to-morrow,” but

also “to-week,” “to-year.” “Tar’ble” is often used for

“very,” in a good as well as a bad sense. There are many

words bearing no resemblance to English in Dorset speech.

What modern Englishman would recognise a “mole hill”

in a “wont-heave,” or “cantankerous” in “thirtover”?

But too much space would be occupied were this fascinating

subject to be pursued further.

National schools, however, are corrupting Wessex

speech, and the niceties of Wessex grammar are often

neglected by the children. Probably the true Dorset will

soon be a thing of the past. William Barnes’ poems and

Thomas Hardy’s Wessex novels, especially the latter,

will then become invaluable to the philologist. In some

instances Mr. Barnes’ spelling seems hardly to represent

the sound of words as they are uttered by Dorset, or, as

they say here, “Darset” lips.

[Pg 19]

THE BARROWS OF DORSET

By C. S. Prideaux

HE County of Dorset is exceedingly rich in

the prehistoric burial-places commonly called

barrows. At the present time considerably over

a thousand are marked on the one-inch Ordnance

Map, and, considering the numbers which have been

destroyed, we may surely claim that Dorset was a

populous centre in prehistoric times, owing probably to

its proximity to the Continent and its safe harbours,

as well as to its high and dry downs and wooded valleys.

The long barrow is the earliest form of sepulchral mound,

being the burial-place of the people of the Neolithic or

Late Stone Age, a period when men were quite ignorant

of the use of metals, with the possible exception of gold,

using flint or stone weapons and implements, but who

cultivated cereals, domesticated animals, and manufactured

a rude kind of hand-made pottery. Previous to this, stone

implements and weapons were of a rather rude type; but

now not only were they more finely chipped, but often

polished.

The round barrows are the burial-places of the Goidels,

a branch of the Celtic family, who were taller than the

Neolithic men and had rounder heads. They belong to the

Bronze Age, a period when that metal was first introduced

into Britain; and although comparatively little is found in

the round barrows of Dorset, still less has been discovered

in the North of England, probably owing to the greater

distance from the Continent.

[Pg 20]

Hand-made pottery abounds, artistically decorated with

diagonal lines and dots, which are combined to form such

a variety of patterns that probably no two vessels are found

alike. Stone and flint implements were still in common

use, and may be found almost anywhere in Dorset,

especially on ploughed uplands after a storm of rain, when

the freshly-turned-up flints have been washed clear of

earth.

In discussing different periods, we must never lose sight

of the fact that there is much overlapping; and although

it is known that the long-barrow men had long heads and

were a short race, averaging 5 ft. 4 in. in height, and that

the round-barrow men had round heads and averaged

5 ft. 8 in.,[4] we sometimes find fairly long-shaped skulls in

the round barrows, showing that the physical peculiarities

of the two races became blended.

Long barrows are not common in Dorset, and little has

been done in examining their contents. This is probably

due to their large size, and the consequent difficulty in

opening them. They are generally found inland, and

singly, with their long diameter east and west; and the

primary interments, at any rate in Dorset, are unburnt,

and usually placed nearer the east end. Some are chambered,

especially where large flat stones were easily obtainable,

but more often they are simply formed of mould and

chalk rubble. Their great size cannot fail to impress us,

and we may well wonder how such huge mounds were

constructed with the primitive implements at the disposal

of Neolithic man. One near Pimperne, measured by Mr.

Charles Warne, is 110 yards long, and there are others

near Bere Regis, Cranborne, Gussage, and Kingston

Russell; and within a couple of miles of the latter place,

besides the huge long barrow, are dozens of round barrows,

the remains of British villages, hut circles, stone circles,

and a monolith.

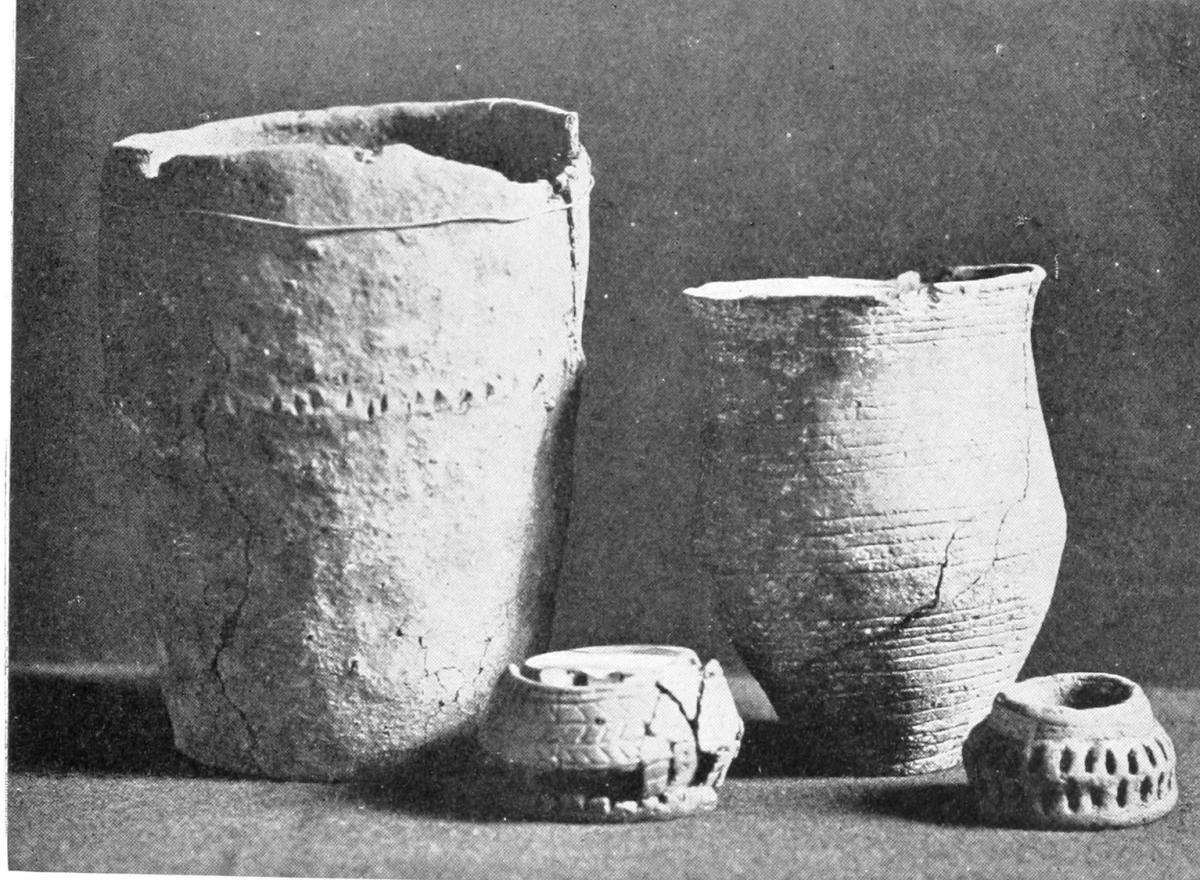

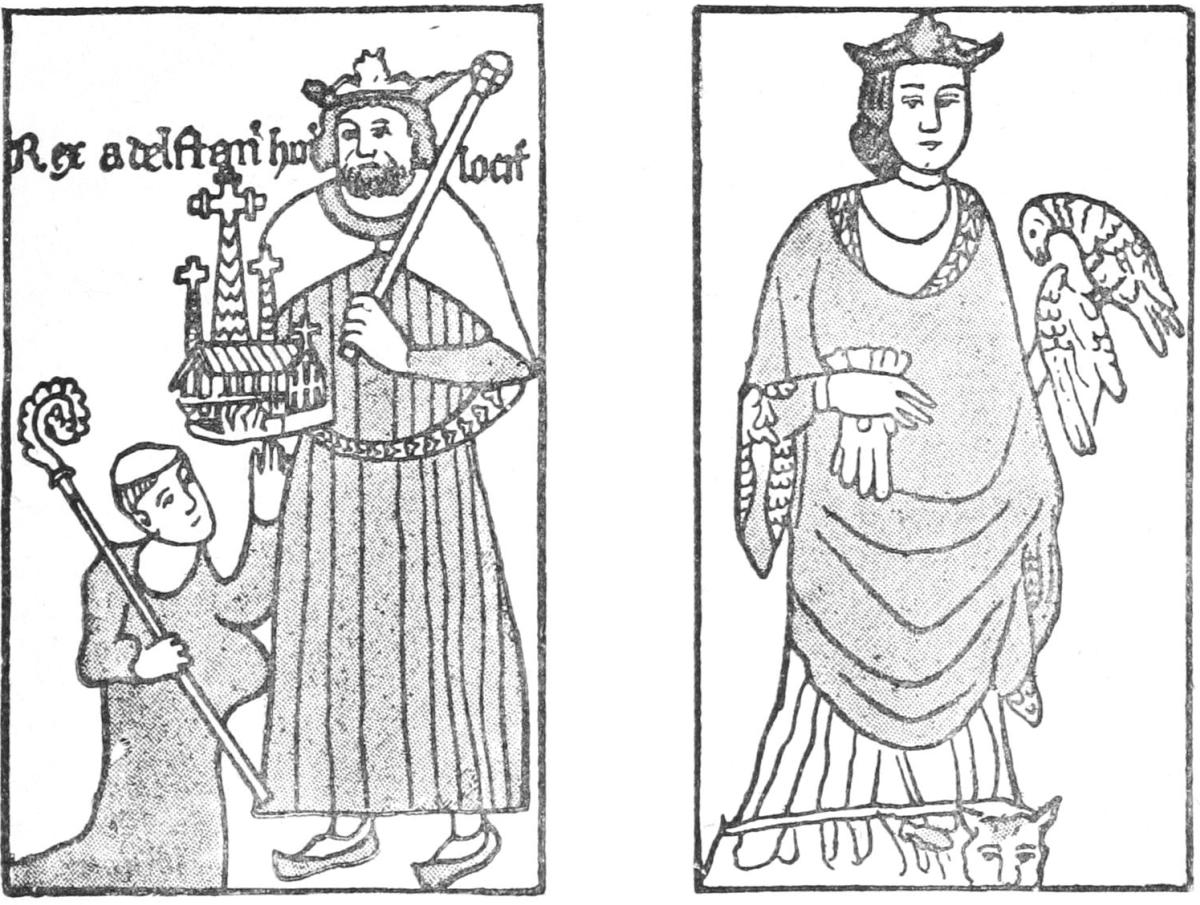

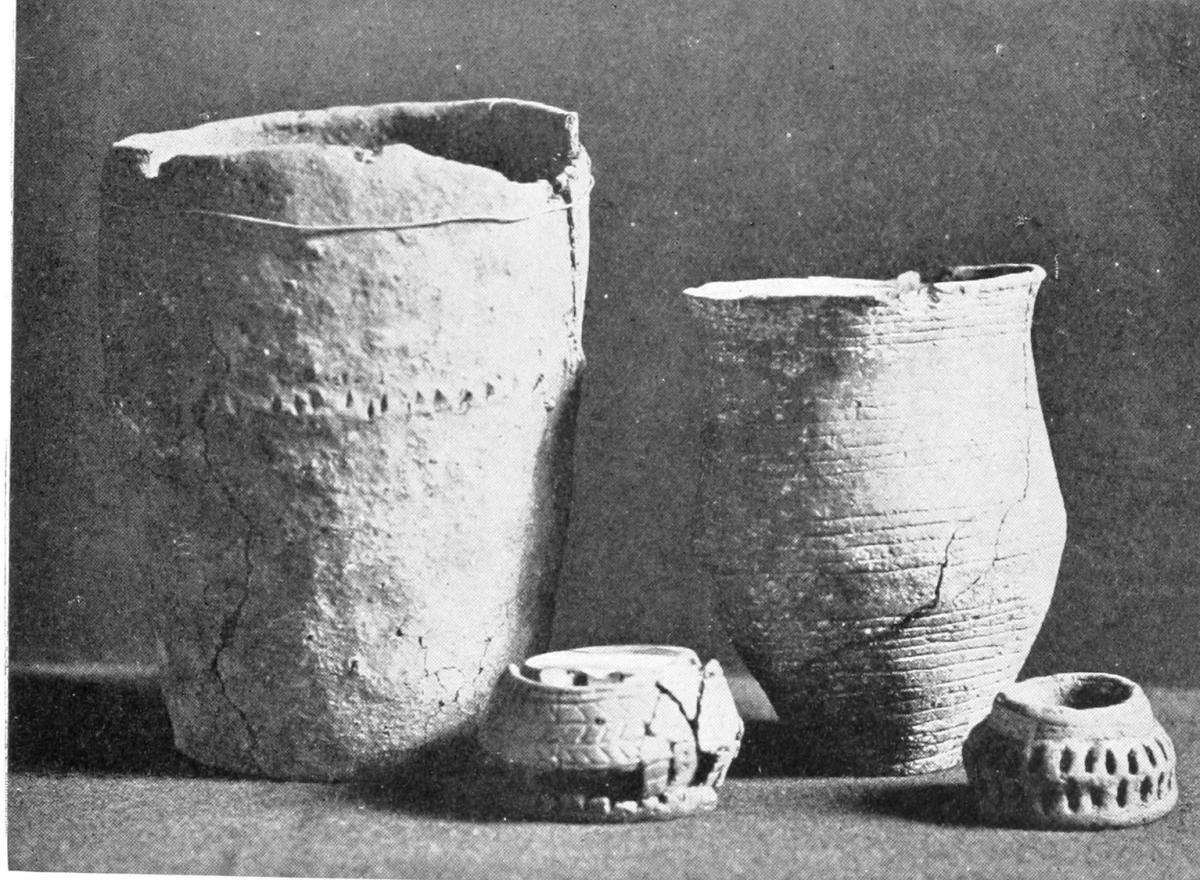

PLATE I. Figs. 1 3 2 4 6 5

Bronze Age Objects from Dorset Round Barrows

(IN THE DORSET COUNTY MUSEUM).

⅕ Scale.

PLATE II. Figs. 1 3 2 4

Bronze Age Objects from Dorset Round Barrows

(IN THE DORSET COUNTY MUSEUM).

⅕ Scale.

[Pg 21]

The late Lieut.-General Pitt-Rivers, in 1893, removed

the whole of Wor Barrow, on Handley Down,[5] and made

a very exhaustive examination of its contents, which presented

many features of peculiar interest. This barrow,

with ditch, was about 175 feet long, 125 feet wide, and

13½ feet high; inside the mound on the ground level was

an oblong space, 93 ft. by 34 ft., surrounded by a trench

filled with flints. The earth above the trench bore traces

of wooden piles, which were, no doubt, originally stuck into

the trench with the flints packed around to keep them in

place, thus forming a palisade; the wooden piles in this

case taking the place of the stone slabs found in the stone-chambered

long barrows of Gloucestershire and elsewhere.

Six primary interments by inhumation were discovered

at the south-east part of the enclosure, with a fragment

of coarse British pottery. Three of the bodies were in a

crouched position. The remaining three had been deposited

as bones, not in sequence, the long bones being laid out

by the side of the skulls; and careful measurement of

these bones shows that their owners were the short people

of the long-headed or Neolithic race, which confirms the

first part of Dr. Thurnam’s axiom: “Long barrows long

skulls, round barrows round skulls.” Nineteen secondary

interments of a later date were found in the upper part

of the barrow and in the surrounding ditch, with numerous

pieces of pottery, flint implements, fragments of bronze and

iron, and coins, proving that the barrow was used as a

place of burial down to Roman times.

In Dorset the round barrows are generally found on

the summits of the hills which run through the county,

more particularly on the Ridgeway, which roughly follows

the coast line from near Bridport to Swanage, where may

be seen some hundreds of all sizes, from huge barrows over

100 feet in diameter and 15 feet in height to small mounds,

so little raised above the surface that only the tell-tale[Pg 22]

shadows cast by the rising or setting sun show where a

former inhabitant lies buried.

In the western part of the county they may be traced

from Kingston Russell to Agger-Dun, through Sydling and

Cerne Abbas to Bulbarrow, and in the east, from Swanage

Bay to Bere Regis; and also near Dorchester, Wimborne,

Blandford, and other places.

In the Bronze Age cremation and inhumation were both

practised; but in Dorset burials by cremation are the more

common. The cremated remains were sometimes placed

in a hole or on the surface line, with nothing to protect

them from the weight of the barrow above; at other times

they were covered by flat slabs of stone, built in the form

of a small closed chamber or cist. Often they were placed

on a flat piece of stone, and covered with an inverted urn,

or put in an urn, with a covering slab over them; and they

have been found wrapped in an animal’s skin, or in a bag

of some woven material, or even in a wooden coffin.

The inhumed bodies are nearly always found in a contracted

posture, with the knees drawn up towards the

chin; and a larger number face either east, south or west,

than north. In the case of an inhumation, when the body

was deposited below the old surface level, the grave was

often neatly hewn and sometimes lined with slabs of stone,

and it was the common custom to pile a heap of flints

over it, affording a protection from wild animals; above

the flints was heaped the main portion of the mound, which

consisted of mould and chalk rubble.

A ditch, with or without a causeway,[6] usually surrounds

each barrow, but is so often silted up that no trace of it

can be seen on the surface; it probably helped to supply

the chalk rubble of the barrow.

Bronze Age sepulchral pottery, which is hand-made,

often imperfectly baked and unglazed, has been divided

into four classes: the beaker or drinking vessel, the food[Pg 23]

vessel, the incense cup, and the cinerary urn. The two

former are usually associated with inhumations; the two

latter with cremations.

As a type of prehistoric ceramic art in Britain, the

Hon. J. Abercromby says that the beaker is the earliest,

and the cinerary urn the latest.[7]

Plate II., fig. 2, is a typical drinking vessel or beaker

which was found in the hands of a skeleton during alterations

to the Masonic Hall at Dorchester. It is made of

thin, reddish, well-baked pottery, and from the stains

inside it evidently contained food or liquid at some time.

The beaker is more often met with than the food vessel,

being found on the Continent as well as in England. The

food vessel, on the other hand, is a type unrepresented

outside the British Isles, and is entirely wanting in Wiltshire,[8]

although common in the North of England, Scotland,

and Ireland. In the Dorset County Museum at Dorchester

there are several fine examples found in the county, and

Plate I., fig. 1, represents one taken from a barrow near

Martinstown.[9] It is of unusual interest, as one-handled

food-vessels are rare. In this inhumed primary interment

the vessel was lying in the arms of the skeleton, whilst

close by was another and much smaller vessel, with the

remains of three infants.

The terms “drinking-vessel” and “food-vessel” may

possibly be accurate, as these vessels may have held liquids

or food; but there is no evidence to show that the so-called

“incense cups” had anything to do with incense. The more

feasible idea seems to be that they were used to hold embers

with which to fire the funeral pile, and the holes with

which they are generally perforated would have been most

useful for admitting air to keep the embers alight.[10] These[Pg 24]

small vessels are usually very much ornamented, even on

their bases, with horizontal lines, zigzags, chevrons, and

the like, and occasionally a grape-like pattern. They are

seldom more than three inches in height, but vary much

in shape, and often are found broken, with the fragments

widely separated, as if they had been smashed purposely

at the time of the burial. Plate II., figs. 3 and 4, are from

specimens in the Dorset County Museum, which also contains

several other Dorset examples.

There can be no doubt as to the use of the cinerary

urn, which always either contains or covers cremated

remains. The urn (Plate II., fig. 1) is from the celebrated

Deverel Barrow, which was opened in 1825 by Mr. W. A.

Miles. The shape of this urn is particularly common in

Dorset, as well as another variety which has handles, or,

rather, perforated projections or knobs. A third and

prettier variety is also met with, having a small base, and

a thick overhanging rim or band at the mouth, generally

ornamented.

It is rare to find curved lines in the ornamentation of

Bronze Age pottery, but sometimes concentric circles and

spiral ornaments are met with on rock-surfaces and

sculptured stones. Mr. Charles Warne found in tumulus

12, Came Down, Dorchester, two flat stones covering two

cairns with incised concentric circles cut on their surfaces.[11]

There is no clear evidence of iron having been found

in the round barrows of Dorset in connection with a Bronze

Age interment; but of gold several examples may be seen

in the County Museum, and one, which was found in

Clandon Barrow, near Martinstown, with a jet head of a

sceptre with gold studs, is shown in Plate I., fig 2. Others

were discovered in Mayo’s Barrow and Culliford Tree.[12]

Bronze, which is an alloy of copper and tin, is the only

other metal found with primary interments in our Dorset

round barrows.

[Pg 25]

The County Museum possesses some excellent celts and

palstaves; a set of six socketed celts came from a barrow

near Agger-Dun, and look as if they had just come from

the mould. They are ornamented with slender ridges,

ending in tiny knobs, and have never been sharpened (two

of them are figured in Plate I., figs. 3 and 4); another celt,

from a barrow in the Ridgeway, is interesting as having

a fragment of cloth adhering to it. Daggers are found,

generally, with cremated remains, and are usually

ornamented with a line or lines, which, beginning just

below the point, run down the blade parallel with the

cutting edges. The rivets which fastened the blade to the

handle are often in position with fragments of the original

wooden handle and sheath.[13] These daggers seem to be

more common in Dorset than in the northern counties,

and many examples may be seen in the County Museum,

and two are illustrated in Plate I., figs. 5 and 6.

Bronze pins, glass beads, amber and Kimmeridge shell

objects, bone tweezers and pins, slingstones and whetstones,

are occasionally met with; but by far the most common

objects are the flint and stone implements, weapons, and

flakes.

In making a trench through a barrow near Martinstown,[14]

more than 1,200 flakes or chips of flints were found, besides

some beautifully-formed scrapers, a fabricator, a flint saw,

most skilfully notched, and a borer with a gimlet-like

point.

Arrow-heads are not common in Dorset, but six were

found in a barrow in Fordington Field, Dorchester. They

are beautiful specimens, barbed and tongued; the heaviest

only weighs twenty-five grains, and the lightest sixteen

grains. Mr. Warne mentions the finding of arrow-heads,

and also (a rare find in Dorset) a stone battle-axe, from a

barrow on Steepleton Down.

[Pg 26]

Charred wood is a conspicuous feature, and animal

bones are also met with in the county, and in such positions

as to prove that they were placed there at the time of the

primary interment. Stags’ horns, often with the tips worn

as though they had been used as picks, are found, both in

the barrows and in the ditches.

So far only objects belonging to the Bronze Age have

been mentioned; but as later races used these burial-places,

objects of a later date are common. Bronze and

iron objects and pottery, and coins of every period, are

often found above the original interment and in the ditches.

This makes it difficult for an investigator to settle with

certainty the different positions in which the objects were

deposited; and unless he is most careful he will get the

relics from various periods mixed. Therefore, the practice

of digging a hole into one of these burial-mounds, for

the sake of a possible find, cannot be too heartily condemned.

Anyone who is ambitious to open a barrow

should carefully read those wonderful books on Excavations

in Cranborne Chase, by the late Lieut.-General Pitt-Rivers,

before he puts a spade into the ground; for a careless dig

means evidence destroyed for those that come after.

Most Dorset people will remember the late curator of

the County Museum, Mr. Henry Moule, and perhaps some

may have heard him tell this story, but it will bear

repeating. A labourer had brought a piece of pottery to

the Museum, and Mr. Moule explained to him that it not

only came from a barrow, but that it was most interesting,

and that he would like to keep it for the Museum. The

man looked surprised, and said, “Well, Meäster, I’ve

a-knocked up scores o’ theäsem things. I used to level

them there hipes (or heäps) an’ drawed awaÿ the vlints

vor to mend the roads; an’ I must ha’ broke up dozens

o’ theäse here wold pots; but they niver had no cwoins

inzide ’em.” Those who knew Mr. Moule can imagine

his horror.

Much more remains to be done by Dorset people in[Pg 27]

investigating these most interesting relics of the past, for

we know little of the builders of these mounds; and, as

Mr. Warne says in his introduction to The Celtic Tumuli

of Dorset:—

If the Dorsetshire barrows cannot be placed in comparison with many

of those of Wiltshire ... or Derbyshire, they may, nevertheless, be

regarded with intense interest, as their examination has satisfactorily

established the fact that they constitute the earliest series of tumuli in any

part of the kingdom; whilst they identify Dorset as one of the earliest

colonised portions of Britain.

[Pg 28]

THE ROMAN OCCUPATION

By Captain J. E. Acland

Curator, Dorset County Museum

LTHOUGH we are dealing with historic and

not prehistoric times in describing the

occupation of the County of Dorset by the

Romans, it is to the work of the spade and not

of the pen that we must turn for the memorials of that

most interesting and important period, which lasted nearly

four hundred years; when the all-powerful, masterful race,

the conquerors of the world, held sway, enforced obedience

to their laws, and inaugurated that system of colonisation

which was perhaps the best the world has ever seen—a

system designed and developed according to exact

regulations, which savoured more of military discipline

than of that civil liberty which we associate with the

profession of agriculture.

The Roman occupation was indeed an admirable

combination of military and civil rule; and the memorials

fall naturally into two distinct classes, corresponding with

two distinct periods. There is, first, the period of

conquest, embracing the years during which the Roman

Legions drove back the native levies, and captured their

strongholds; not in one summer campaign we may well

believe, but year after year, with irresistible force, until

the subjugated tribes laid down their arms and yielded

the hostages demanded by the conquerors. Then followed

the period of peace, of civilisation, and of colonising; of

improving the roads, and marking out of farms; the days[Pg 29]

of trade and commerce, and of building houses, temples,

and places for public amusement.

Now both aspects of the occupation are to be seen

as clearly at this day as if they were described in the

pages of a book; and yet what is the fact? Scarcely a

sentence can be found of written history which deals with

it. General Pitt-Rivers, who, living in Dorset, devoted

many years of his life to antiquarian research, asserts that

having read with attention all the writings that were

accessible upon that obscure period of history, some by

scholars of great ability, nothing definite can be found to

relate to the Roman Conquest. It is, however, generally

assumed that it fell to the lot of Vespasian, in command

of the world-famous “Legio Secunda,” to commence, if

not to complete, the subjugation of the Durotriges, the

people who are believed to have inhabited the southern

portion of the county. The only reference to Vespasian’s

campaign by contemporary historians is made by

Suetonius. He says that Vespasian crossed to Britain,

fought with the enemy some thirty times, and reduced

to submission two most warlike tribes and twenty fortified

camps, and the island (Isle of Wight) adjacent to the

coast. In this statement, which is all too brief to satisfy

our curiosity, may lie the main facts of the passing of

Dorset into Roman power. The work begun by Vespasian

may, indeed, have been completed by others—by Paulinus

Suetonius, the Governor of Britain about the year 60, and

by Agricola; and where so much is left to conjecture, it

is at least worth while to give once more the theory

propounded by the well-known antiquary, the late Mr.

Charles Warne, F.S.A. In a paper read before the Society

of Antiquaries in June, 1867, he suggests that as the south-eastern

parts of Britain had been previously visited by

Roman armies, Vespasian directed his course further to

the west, and either made the Isle of Wight the base of

his operations or anchored his ships in the harbours of

Swanage or Poole. Close by is the commencement of the[Pg 30]

long range of hills, The Ridgeway, which, with few

interruptions, follows the coast line, and still shews by

the number of the burial-mounds the district inhabited

by the British.

Mr. Warne proceeds to enumerate the various camps

along this route, all at convenient distances from one

another, some of which shew by their construction that

they were Roman camps, and others British camps,

captured by the conquering legions, as narrated by

Suetonius. If Vespasian had pursued this plan of

campaign, it would have had the additional advantage

of enabling him to keep in touch with his transports.

As one hill fortress after another was captured in the

march westward along the Ridgeway heights, so the fleet

might have changed its anchorage from Swanage Bay

to Lulworth, from Lulworth to the shelter of Weymouth

and Portland, and finally to the neighbourhood of

Charmouth or Lyme Regis.

There is this also to be said in favour of Mr. Warne’s

conjecture. An attacking force must find out and capture

the strongholds of the defenders, which would naturally

be made more strongly, and therefore last longer than the

camps of the invaders. And this is what we see in the

suggested line of the Roman advance. First, on the east,

Flowers, or Florus Bury Camp, and Bindun, then Mai-dun

(Maiden Castle), after that Eggardun, and finally, at the

western limit of the county, Conig’s Castle and Pylsdun.

All these are (as far as can be seen now) British camps

of refuge; all of them must have been captured before

the Roman generals could feel secure in their own isolated

position on a foreign shore. That they were one and

all occupied by the conquerors is also most probable,

and would account for the discovery of Roman relics

within their areas. No Roman camps can be seen at

all approaching in strength or size these magnificent hill

fortresses. It is, of course, well known that the armies

of Rome never halted for a night without forming an[Pg 31]

entrenchment of sufficient size to include not only the

fighting men, but the baggage train, and though traces

of these still remain on the hills of Dorset, the majority

have long ago disappeared.

Perhaps the most interesting example of the military

occupation of the two races is to be seen at Hod Hill,

near Blandford, where a well-defined Roman Camp is

constructed within the area of a previously occupied

British fortress, and here have been found spear heads,

arrow heads, spurs and portions of harness, rings and

fibulæ, and fragments of pottery, all indicating the Roman

occupation; iron was found more generally than bronze,

and the coins are those of the earlier emperors, including

Claudius, in whose reign Vespasian made his conquests.

Badbury, four miles north-west of Wimborne, Woodbury,

near Bere Regis, and Hambledon, five miles north of

Blandford, may be referred to as memorials of the time

of the Roman occupation, though not of Roman construction.

Poundbury Camp, with its Saxon appellation, deserves

special mention, for, being situated on the outskirts of

Dorchester, it has been studied more frequently perhaps

than any other earthwork in the county. It has the form

of an irregular square, with a single vallum, except on

the more exposed west side, where it is doubled, and

traces have been discovered of other ramparts now

obliterated. On the north the camp overhangs the river

and valley, once probably a lake or morass, and here the

defences are slight. The area within the vallum is about

330 yards from east to west, and 180 yards from north

to south. Some authorities affirm that it was raised by

the Danes about A.D. 1002, when they attacked Dorchester.

Stukeley regards it as one of Vespasian’s camps when

engaged in his conquest of the Durotriges, while other

antiquarians claim for it a British origin, prior to the

Roman invasion. Mr. Warne, whose opinions are always

worthy of most careful consideration, “holds it to be a[Pg 32]

safer speculation to regard it as a Roman earthwork,”

and, no doubt, in form and general outline and size it

is very similar to other Roman camps, and altogether

different to the magnificent British fortress Maiden Castle,

not two miles away. Many Roman relics have been found,

including coins ranging from the times of Claudius to

Constantine, and a tumulus is still to be seen within the

vallum, which alone would be an argument against its

Celtic origin.

Poundbury is insignificant indeed when compared with

Mai-dun, and it is impossible by mere description to

convey an adequate impression of this great earth fortress,

singled out by many as the finest work of its kind. It

certainly surpasses all others in the land of the Durotriges,

and probably nowhere in the world can entrenchments

be seen of such stupendous strength. This camp, which

is said to occupy 120 acres, is in form an irregular oval,

embracing the whole of the hill on which it stands; its

length is nearly 800 yards, and width 275 yards. On the

north, facing the plain, there are three lines of ramparts,

with intervening ditches, the slopes being exceedingly

steep, and measuring over 60 feet from apex to base.

On the south the number of ramparts is increased, but

they are not so grand, and, indeed, as Mr. Warne remarks,

they appear to have been left in an unfinished condition.

At the east and west ends are the two principal entrances,

and here the ingenuity of the designer is manifested in

a surprising manner. At one end five or six ramparts,

at the other as many as seven or eight are built, so as

to cover or overlap one another; vallum and fossa,

arranged with consummate skill, to complete the intricacies

of entrance, and to compel an enemy to undertake a task

of the utmost difficulty and danger.

In later times this camp was, no doubt, occupied by

Roman troops as summer quarters, its healthy position

rendering it very suitable for the purpose. Perhaps, still

later, it became the residence of some Roman magnate,[Pg 33]

who selected that fine eminence for his country villa; at

any rate, there should be no difficulty in accounting for

the discovery of Roman coins and implements, or even

of villas, on the sites of the camps and castles of the

British. Many a hard fought battle must have raged

around their earthen walls.

Ever and anon, with host to host,

Shocks, and the splintering spear, the hard mail hewn,

Shield breakings, and the clash of brands, the crash

Of battle axes on shattered helms.

Many a shout of victory must have been heard as the

conquering legions forced their way over the ramparts