CARLYLE’S LAUGH

AND OTHER SURPRISES

BY

THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

MDCCCCIX

Thomas Wentworth Higginson

WORKS. Newly arranged. 7 Vols. 12mo, each, $2.00.

THE PROCESSION OF THE FLOWERS. $1.25.

THE AFTERNOON LANDSCAPE. Poems and Translations. $1.00.

THE MONARCH OF DREAMS. 18mo, 50 cents.

MARGARET FULLER OSSOLI. In the American Men of Letters Series. 16mo, $1.50.

HENRY W. LONGFELLOW. In American Men of Letters Series. 16mo, $1.10, net. Postage 10 cents.

PART OF A MAN’S LIFE. Illustrated. Large 8vo, $2.50, net. Postage 18 cents.

LIFE AND TIMES OF STEPHEN HIGGINSON. Illustrated. Large crown 8vo, $2.00, net. Postage extra.

CARLYLE’S LAUGH AND OTHER SURPRISES. 12mo, $2.00, net. Postage 15 cents.

EDITED WITH MRS. E. H. BIGELOW.

AMERICAN SONNETS. 18mo, $1.25.

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

Boston and New York

CARLYLE’S LAUGH

AND OTHER SURPRISES

BY

THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN COMPANY

The Riverside Press Cambridge

MDCCCCIX

COPYRIGHT, 1909, BY THOMAS WENTWORTH HIGGINSON

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Published October 1909

The two papers in this volume which bear the titles “A Keats Manuscript” and “A Shelley Manuscript” are reprinted by permission from a work called “Book and Heart,” by Thomas Wentworth Higginson, copyright, 1897, by Harper and Brothers, with whose consent the essay entitled “One of Thackeray’s Women” also is published. Leave has been obtained to reprint the papers on Brown, Cooper, and Thoreau, from Carpenter’s “American Prose,” copyrighted by the Macmillan Company, 1898. My thanks are also due to the American Academy of Arts and Sciences for permission to reprint the papers on Scudder, Atkinson, and Cabot; to the proprietors of “Putnam’s Magazine” for the paper entitled “Emerson’s Foot-Note Person”; to the proprietors of the New York “Evening Post” for the article on George Bancroft from “The Nation”; to the editor of the “Harvard Graduates’ Magazine” for the paper on “Göttingen and Harvard”; and to the editors of the “Outlook” for the papers on Charles Eliot Norton, Julia Ward Howe, Edward Everett Hale, William J. Rolfe, and “Old Newport Days.” Most of the remaining sketches appeared originally in the “Atlantic Monthly.”

T. W. H.

| I. | CARLYLE’S LAUGH | 1 |

| II. | A SHELLEY MANUSCRIPT | 13 |

| III. | A KEATS MANUSCRIPT | 21 |

| IV. | MASSASOIT, INDIAN CHIEF | 31 |

| V. | JAMES FENIMORE COOPER | 45 |

| VI. | CHARLES BROCKDEN BROWN | 55 |

| VII. | HENRY DAVID THOREAU | 65 |

| VIII. | EMERSON’S “FOOT-NOTE PERSON,”—ALCOTT | 75 |

| IX. | GEORGE BANCROFT | 93 |

| X. | CHARLES ELIOT NORTON | 119 |

| XI. | EDMUND CLARENCE STEDMAN | 137 |

| XII. | EDWARD EVERETT HALE | 157 |

| XIII. | A MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL, RUFUS SAXTON | 173 |

| XIV. | ONE OF THACKERAY’S WOMEN | 183 |

| XV. | JOHN BARTLETT | 191 |

| XVI. | HORACE ELISHA SCUDDER | 201[viii] |

| XVII. | EDWARD ATKINSON | 213 |

| XVIII. | JAMES ELLIOT CABOT | 231 |

| XIX. | EMILY DICKINSON | 247 |

| XX. | JULIA WARD HOWE | 285 |

| XXI. | WILLIAM JAMES ROLFE | 313 |

| XXII. | GÖTTINGEN AND HARVARD A CENTURY AGO | 325 |

| XXIII. | OLD NEWPORT DAYS | 349 |

| XXIV. | A HALF-CENTURY OF AMERICAN LITERATURE | 367 |

None of the many sketches of Carlyle that have been published since his death have brought out quite distinctly enough the thing which struck me more forcibly than all else, when in the actual presence of the man; namely, the peculiar quality and expression of his laugh. It need hardly be said that there is a great deal in a laugh. One of the most telling pieces of oratory that ever reached my ears was Victor Hugo’s vindication, at the Voltaire Centenary in Paris, of that author’s smile. To be sure, Carlyle’s laugh was not like that smile, but it was something as inseparable from his personality, and as essential to the account, when making up one’s estimate of him. It was as individually characteristic as his face or his dress, or his way of talking or of writing. Indeed, it seemed indispensable for the explanation of all of these. I found in looking back upon my first interview with him, that all I had known of Carlyle through others, or through his own books, for twenty-five years, had been utterly defective,—had left out, in fact, the key to his whole nature,—inasmuch as nobody had ever described to me his laugh.

It is impossible to follow the matter further without a little bit of personal narration. On visiting England for the first time, in 1872, I was offered a letter to Carlyle, and declined it. Like all of my own generation, I had been under some personal obligations to him for his early writings,—though in my case this debt was trifling compared with that due to Emerson,—but his “Latter-Day Pamphlets” and his reported utterances on American affairs had taken away all special desire to meet him, besides the ungraciousness said to mark his demeanor toward visitors from the United States. Yet, when I was once fairly launched in that fascinating world of London society, where the American sees, as Willis used to say, whole shelves of his library walking about in coats and gowns, this disinclination rapidly softened. And when Mr. Froude kindly offered to take me with him for one of his afternoon calls on Carlyle, and further proposed that I should join them in their habitual walk through the parks, it was not in human nature—or at least in American nature—to resist.

We accordingly went after lunch, one day in May, to Carlyle’s modest house in Chelsea, and found him in his study, reading—by a chance very appropriate for me—in Weiss’s “Life of Parker.” He received us kindly, but[5] at once began inveighing against the want of arrangement in the book he was reading, the defective grouping of the different parts, and the impossibility of finding anything in it, even by aid of the index. He then went on to speak of Parker himself, and of other Americans whom he had met. I do not recall the details of the conversation, but to my surprise he did not say a single really offensive or ungracious thing. If he did, it related less to my countrymen than to his own, for I remember his saying some rather stern things about Scotchmen. But that which saved these and all his sharpest words from being actually offensive was this, that, after the most vehement tirade, he would suddenly pause, throw his head back, and give as genuine and kindly a laugh as I ever heard from a human being. It was not the bitter laugh of the cynic, nor yet the big-bodied laugh of the burly joker; least of all was it the thin and rasping cackle of the dyspeptic satirist. It was a broad, honest, human laugh, which, beginning in the brain, took into its action the whole heart and diaphragm, and instantly changed the worn face into something frank and even winning, giving to it an expression that would have won the confidence of any child. Nor did it convey the impression of an exceptional thing that had occurred for the first time that day, and might[6] never happen again. Rather, it produced the effect of something habitual; of being the channel, well worn for years, by which the overflow of a strong nature was discharged. It cleared the air like thunder, and left the atmosphere sweet. It seemed to say to himself, if not to us, “Do not let us take this too seriously; it is my way of putting things. What refuge is there for a man who looks below the surface in a world like this, except to laugh now and then?” The laugh, in short, revealed the humorist; if I said the genial humorist, wearing a mask of grimness, I should hardly go too far for the impression it left. At any rate, it shifted the ground, and transferred the whole matter to that realm of thought where men play with things. The instant Carlyle laughed, he seemed to take the counsel of his old friend Emerson, and to write upon the lintels of his doorway, “Whim.”

Whether this interpretation be right or wrong, it is certain that the effect of this new point of view upon one of his visitors was wholly disarming. The bitter and unlovely vision vanished; my armed neutrality went with it, and there I sat talking with Carlyle as fearlessly as if he were an old friend. The talk soon fell on the most dangerous of all ground, our Civil War, which was then near enough to inspire curiosity; and he put questions showing that he[7] had, after all, considered the matter in a sane and reasonable way. He was especially interested in the freed slaves and the colored troops; he said but little, yet that was always to the point, and without one ungenerous word. On the contrary, he showed more readiness to comprehend the situation, as it existed after the war, than was to be found in most Englishmen at that time. The need of giving the ballot to the former slaves he readily admitted, when it was explained to him; and he at once volunteered the remark that in a republic they needed this, as the guarantee of their freedom. “You could do no less,” he said, “for the men who had stood by you.” I could scarcely convince my senses that this manly and reasonable critic was the terrible Carlyle, the hater of “Cuffee” and “Quashee” and of all republican government. If at times a trace of angry exaggeration showed itself, the good, sunny laugh came in and cleared the air.

We walked beneath the lovely trees of Kensington Gardens, then in the glory of an English May; and I had my first sight of the endless procession of riders and equipages in Rotten Row. My two companions received numerous greetings, and as I walked in safe obscurity by their side, I could cast sly glances of keen enjoyment at the odd combination visible in their[8] looks. Froude’s fine face and bearing became familiar afterwards to Americans, and he was irreproachably dressed; while probably no salutation was ever bestowed from an elegant passing carriage on an odder figure than Carlyle. Tall, very thin, and slightly stooping; with unkempt, grizzly whiskers pushed up by a high collar, and kept down by an ancient felt hat; wearing an old faded frock coat, checked waistcoat, coarse gray trousers, and russet shoes; holding a stout stick, with his hands encased in very large gray woolen gloves,—this was Carlyle. I noticed that, when we first left his house, his aspect attracted no notice in the streets, being doubtless familiar in his own neighborhood; but as we went farther and farther on, many eyes were turned in his direction, and men sometimes stopped to gaze at him. Little he noticed it, however, as he plodded along with his eyes cast down or looking straight before him, while his lips poured forth an endless stream of talk. Once and once only he was accosted, and forced to answer; and I recall it with delight as showing how the unerring instinct of childhood coincided with mine, and pronounced him not a man to be feared.

We passed a spot where some nobleman’s grounds were being appropriated for a public park; it was only lately that people had been[9] allowed to cross them, and all was in the rough, preparations for the change having been begun. Part of the turf had been torn up for a road-way, but there was a little emerald strip where three or four ragged children, the oldest not over ten, were turning somersaults in great delight. As we approached, they paused and looked shyly at us, as if uncertain of their right on these premises; and I could see the oldest, a sharp-eyed little London boy, reviewing us with one keen glance, as if selecting him in whom confidence might best be placed. Now I am myself a child-loving person; and I had seen with pleasure Mr. Froude’s kindly ways with his own youthful household: yet the little gamin dismissed us with a glance and fastened on Carlyle. Pausing on one foot, as if ready to take to his heels on the least discouragement, he called out the daring question, “I say, mister, may we roll on this here grass?” The philosopher faced round, leaning on his staff, and replied in a homelier Scotch accent than I had yet heard him use, “Yes, my little fellow, r-r-roll at discraytion!” Instantly the children resumed their antics, while one little girl repeated meditatively, “He says we may roll at discraytion!”—as if it were some new kind of ninepin-ball.

Six years later, I went with my friend Conway to call on Mr. Carlyle once more, and found the[10] kindly laugh still there, though changed, like all else in him, by the advance of years and the solitude of existence. It could not be said of him that he grew old happily, but he did not grow old unkindly, I should say; it was painful to see him, but it was because one pitied him, not by reason of resentment suggested by anything on his part. He announced himself to be, and he visibly was, a man left behind by time and waiting for death. He seemed in a manner sunk within himself; but I remember well the affectionate way in which he spoke of Emerson, who had just sent him the address entitled “The Future of the Republic.” Carlyle remarked, “I’ve just noo been reading it; the dear Emerson, he thinks the whole warrld’s like himself; and if he can just get a million people together and let them all vote, they’ll be sure to vote right and all will go vara weel”; and then came in the brave laugh of old, but briefer and less hearty by reason of years and sorrows.

One may well hesitate before obtruding upon the public any such private impressions of an eminent man. They will always appear either too personal or too trivial. But I have waited in vain to see some justice done to the side of Carlyle here portrayed; and since it has been very commonly asserted that the effect he produced on strangers was that of a rude and offensive person,[11] it seems almost a duty to testify to the very different way in which one American visitor saw him. An impression produced at two interviews, six years apart, may be worth recording, especially if it proved strong enough to outweigh all previous prejudice and antagonism.

In fine, I should be inclined to appeal from all Carlyle’s apparent bitterness and injustice to the mere quality of his laugh, as giving sufficient proof that the gift of humor underlay all else in him. All his critics, I now think, treat him a little too seriously. No matter what his labors or his purposes, the attitude of the humorist was always behind. As I write, there lies before me a scrap from the original manuscript of his “French Revolution,”—the page being written, after the custom of English authors of half a century ago, on both sides of the paper; and as I study it, every curl and twist of the handwriting, every backstroke of the pen, every substitution of a more piquant word for a plainer one, bespeaks the man of whim. Perhaps this quality came by nature through a Scotch ancestry; perhaps it was strengthened by the accidental course of his early reading. It may be that it was Richter who moulded him, after all, rather than Goethe; and we know that Richter was defined by Carlyle, in his very first literary essay, as “a humorist and a philosopher,” putting[12] the humorist first. The German author’s favorite type of character—seen to best advantage in his Siebenkäs of the “Blumen, Frucht, und Dornenstücke”—came nearer to the actual Carlyle than most of the grave portraitures yet executed. He, as is said of Siebenkäs, disguised his heart beneath a grotesque mask, partly for greater freedom, and partly because he preferred whimsically to exaggerate human folly rather than to share it (dass er die menschliche Thorheit mehr travestiere als nachahme). Both characters might be well summed up in the brief sentence which follows: “A humorist in action is but a satirical improvisatore” (Ein handelnder Humorist ist blos ein satirischer Improvisatore). This last phrase, “a satirical improvisatore,” seems to me better than any other to describe Carlyle.

Were I to hear to-morrow that the main library of Harvard University, with every one of its 496,200 volumes, had been reduced to ashes, there is in my mind no question what book I should most regret. It is that unique, battered, dingy little quarto volume of Shelley’s manuscript poems, in his own handwriting and that of his wife, first given by Miss Jane Clairmont (Shelley’s “Constantia”) to Mr. Edward A. Silsbee, and then presented by him to the library. Not only is it full of that aroma of fascination which belongs to the actual handiwork of a master, but its numerous corrections and interlineations make the reader feel that he is actually traveling in the pathway of that delicate mind. Professor George E. Woodberry had the use of it; he printed in the “Harvard University Calendar” a facsimile of the “Ode to a Skylark” as given in the manuscript, and has cited many of its various readings in his edition of Shelley’s poems. But he has passed by a good many others; and some of these need, I think, for the sake of all students of Shelley, to be put in print, so that in case of the loss or[16] destruction of the precious volume, these fragments at least may be preserved.

There occur in this manuscript the following variations from Professor Woodberry’s text of “The Sensitive Plant”—variations not mentioned by him, for some reason or other, in his footnotes or supplemental notes, and yet not canceled by Shelley:—

[Moon is clearly morn in the Harvard MS.]

[The prefatory And is not in the Harvard MS.]

[The word brambles appears for mandrakes in the Harvard MS.]

These three variations, all of which are interesting, are the only ones I have noted as uncanceled in this particular poem, beyond those recorded by Professor Woodberry. But there are many cases where the manuscript shows, in Shelley’s own handwriting, variations subsequently canceled by him; and these deserve[17] study by all students of the poetic art. His ear was so exquisite and his sense of the balance of a phrase so remarkable, that it is always interesting to see the path by which he came to the final utterance, whatever that was. I have, therefore, copied a number of these modified lines, giving, first, Professor Woodberry’s text, and then the original form of language, as it appears in Shelley’s handwriting, italicizing the words which vary, and giving the pages of Professor Woodberry’s edition. The cancelation or change is sometimes made in pen, sometimes in pencil; and it is possible that, in a few cases, it may have been made by Mrs. Shelley.

[“&” perhaps written carelessly for “at.”]

These comparisons are here carried no further than “The Sensitive Plant,” except that[20] there is a canceled verse of Shelley’s “Curse” against Lord Eldon for depriving him of his children,—a verse so touching that I think it should be preserved. The verse beginning—

opened originally as follows:—

This was abandoned and the following substituted:—

This also was erased, and the present form substituted, although I confess it seems to me both less vigorous and less tender. Professor Woodberry mentions the change, but does not give the canceled verse. In this and other cases I do not venture to blame him for the omission, since an editor must, after all, exercise his own judgment. Yet I cannot but wish that he had carried his citation, even of canceled variations, a little further; and it is evident that some future student of poetic art will yet find rich gleanings in the Harvard Shelley manuscript.

“Touch it,” said Leigh Hunt, when he showed Bayard Taylor a lock of brown silky hair, “and you will have touched Milton’s self.” The magic of the lock of hair is akin to that recognized by nomadic and untamed races in anything that has been worn close to the person of a great or fortunate being. Mr. Leland, much reverenced by the gypsies, whose language he spoke and whose lore he knew better than they know it, had a knife about his person which was supposed by them to secure the granting of any request if held in the hand. When he gave it away, it was like the transfer of fairy power to the happy recipient. The same lucky spell is attributed to a piece of the bride’s garter, in Normandy, or to pins filched from her dress, in Sussex. For those more cultivated, the charm of this transmitted personality is best embodied in autographs, and the more unstudied and unpremeditated the better. In the case of a poet, nothing can be compared with the interest inspired by the first draft of a poem, with its successive amendments—the path by which his thought attained its final and perfect utterance. Tennyson,[24] for instance, was said to be very indignant with those who bore away from his study certain rough drafts of poems, justly holding that the world had no right to any but the completed form. Yet this is what, as students of poetry, we all instinctively wish to do. Rightly or wrongly, we long to trace the successive steps. To some extent, the same opportunity is given in successive editions of the printed work; but here the study is not so much of changes in the poet’s own mind as of those produced by the criticisms, often dull or ignorant, of his readers,—those especially who fail to catch a poet’s very finest thought, and persuade him to dilute it a little for their satisfaction. When I pointed out to Browning some rather unfortunate alterations in his later editions, and charged him with having made them to accommodate stupid people, he admitted the offense and promised to alter them back again, although, of course, he never did. But the changes in an author’s manuscript almost always come either from his own finer perception and steady advance toward the precise conveyance of his own thought, or else from the aid he receives in this from some immediate friend or adviser—most likely a woman—who is in close sympathy with his own mood. The charm is greatest, of course, in seeing and studying and touching the original[25] page, just as it is. For this a photograph is the best substitute, since it preserves the original for the eye, as does the phonograph for the ear. Even with the aid of photography only, there is as much difference between the final corrected shape and the page showing the gradual changes, as between the graceful yacht lying in harbor, anchored, motionless, with sails furled, and the same yacht as a winged creature, gliding into port. Let us now see, by actual comparison, how one of Keats’s yachts came in.

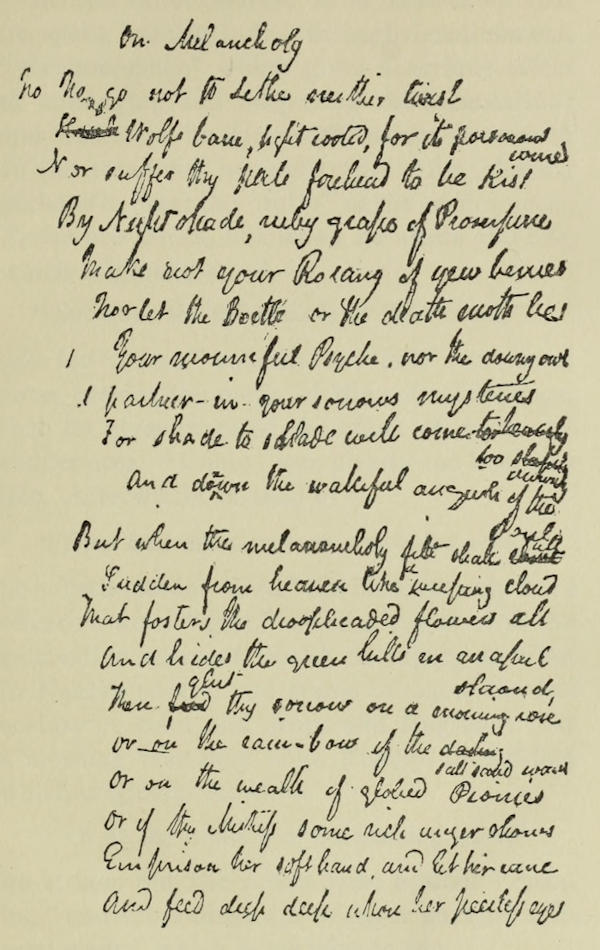

There lies before me a photograph of the first two stanzas of Keats’s “Ode on Melancholy,” as they stood when just written. The manuscript page containing them was given to John Howard Payne by George Keats, the poet’s brother, who lived for many years at Louisville, Kentucky, and died there; but it now belongs to Mr. R. S. Chilton, United States Consul at Goderich, Ontario, who has kindly given me a photograph of it. The verses are in Keats’s well-known and delicate handwriting, and exhibit a series of erasures and substitutions which are now most interesting, inasmuch as the changes in each instance enrich greatly the value of the word-painting.

To begin with, the title varies slightly from that first adopted, and reads simply “On Melancholy,” to which the word “Ode” was later prefixed[26] by the printers. In the second line, where he had half written “Henbane” for the material of his incantation, he blots it out and puts “Wolfsbane,” instantly abandoning the tamer suggestion and bringing in all the wildness and the superstition that have gathered for years around the Loup-garou and the Wehr-wolf. This is plainly no amendment suggested afterward by another person, but is due unmistakably to the quick action of his own mind. There is no other change until the end of the first stanza, where the last two lines were originally written thus:—

It is noticeable that he originally wrote “down” for “drown,” and, in afterward inserting the r, put it in the wrong place—after the o, instead of before it. This was a slip of the pen only; but it was that word “heavily” which cost him a struggle. The words “too heavily” were next crossed out, and under them were written “too sleepily”; then this last word was again erased, and the word “drowsily” was finally substituted—the only expression in the English language, perhaps, which could have precisely indicated the exact shade of debilitating languor he meant.

In the other stanza, it is noticeable that he spells “melancholy,” through heedlessness, “melanancholy,” which gives a curious effect of prolonging and deepening the incantation; and this error he does not discover or correct. In the same way he spells “fit,” “fitt,” having perhaps in mind the “fytte” of the earlier poets. These are trifles, but when he alters the line, which originally stood,—

and for “come” substitutes “fall,” we see at once, besides the merit of the soft alliteration, that he gives more of the effect of doom and suddenness. “Come” was clearly too business like. Afterwards, instead of—

he substitutes for “feed” the inexpressibly more effective word “glut,” which gives at once the exhaustive sense of wealth belonging so often to Keats’s poetry, and seems to match the full ecstasy of color and shape and fragrance that a morning rose may hold. Finally, in the line which originally stood,—

he strikes out the rather trite epithet “dashing,” and substitutes the stronger phrase “salt-sand wave,” which is peculiar to him.

All these changes are happily accepted in the common editions of Keats; but these editions make two errors that are corrected by this manuscript, and should henceforth be abandoned. In the line usually printed,—

the autograph text gives “or” in the place of the second “nor,” a change consonant with the best usage; and in the line,—

the middle word is clearly not “hill,” but “hills.” This is a distinct improvement, both because it broadens the landscape and because it averts the jangle of the closing ll with the final words “fall” and “all” in previous lines.

It is a fortunate thing that, in the uncertain destiny of all literary manuscripts, this characteristic document should have been preserved for us. It will be remembered that Keats himself once wrote in a letter that his fondest prayer, next to that for the health of his brother Tom, would be that some child of his brother George “should be the first American poet.” This letter, printed by Milnes, was written October 29, 1818. George Keats died about 1851, and his youngest daughter, Isabel, who was thought greatly to resemble her uncle[29] John, both in looks and genius, died sadly at the age of seventeen. It is pleasant to think that we have, through the care exercised by this American brother, an opportunity of coming into close touch with the mental processes of that rare genius which first imparted something like actual color to English words. To be brought thus near to Keats suggests that poem by Browning where he speaks of a moment’s interview with one who had seen Shelley, and compares it to picking up an eagle’s feather on a lonely heath.

There was paid on October 19, 1907, one of the few tributes ever openly rendered by the white races to the higher type of native Indian leaders. Such was that given by a large company at Warren, Rhode Island, to Massasoit, the friendly Indian Sachem who had first greeted the early Pilgrims, on their arrival at Plymouth in 1620. The leading address was made by the author of this volume.

The newspaper correspondents tell us that, when an inquiry was one day made among visitors returning from the recent Jamestown Exposition, as to the things seen by each of them which he or she would remember longest, one man replied, “That life-size group in the Smithsonian building which shows John Smith in his old cock-boat trading with the Indians. He is giving them beads or something and getting baskets of corn in exchange.”[1] This seemed to the speaker, and quite reasonably, the very first contact with civilization on the part of the American Indians. Precisely parallel to this is the memorial which we meet to dedicate, and which records the first interview in 1620 between the little group of Plymouth Pilgrims and Massasoit, known as the “greatest commander of the country,” and “Sachem[34] of the whole region north of Narragansett Bay.”[2]

“Heaven from all creatures hides the book of fate,” says the poet Pope; and nothing is more remarkable in human history than the way in which great events sometimes reach their climax at once, instead of gradually working up to it. Never was this better illustrated than when the Plymouth Pilgrims first met the one man of this region who could guarantee them peace for fifty years, and did so. The circumstances seem the simplest of the simple.

The first hasty glance between the Plymouth Puritans and the Indians did not take place, as you will recall, until the newcomers had been four days on shore, when, in the words of the old chronicler, “they espied five or sixe people with a Dogge coming towards them, who were savages: who when they saw them ran into the Woods and whistled the Dogge after them.” (This quadruped, whether large or small, had always a capital letter in his name, while human savages had none, in these early narratives.) When the English pursued the Indians, “they ran away might and main.”[3] The next interview was a stormier one; four days later, those same Pilgrims were asleep on board the[35] “shallope” on the morning of December 8, 1620 (now December 19), when they heard “a great and strange cry,” and arrow-shots came flying amongst them which they returned and one Indian “gave an extraordinary cry” and away they went. After all was quiet, the Pilgrims picked up eighteen arrows, some “headed with brass, some with hart’s horn” (deer’s horn), “and others with eagles’ claws,”[4] the brass heads at least showing that those Indians had met Englishmen before.

Three days after this encounter at Namskeket,—namely, on December 22, 1620 (a date now computed as December 23),—the English landed at Patuxet, now Plymouth. (I know these particulars as to dates, because I was myself born on the anniversary of this first date, the 22d, and regarded myself as a sort of brevet Pilgrim, until men, alleged to be scientific, robbed me of one point of eminence in my life by landing the Pilgrims on the 23d). Three months passed before the sight of any more Indians, when Samoset came, all alone, with his delightful salutation, “Welcome, Englishmen,” and a few days later (March 22, 1621), the great chief of all that region, Massasoit, appeared on the scene.

When he first made himself visible, with[36] sixty men, on that day, upon what is still known as Strawberry Hill, he asked that somebody be sent to hold a parley with him. Edmund Winslow was appointed to this office, and went forward protected only by his sword and armor, and carrying presents to the Sachem. Winslow also made a speech of some length, bringing messages (quite imaginary, perhaps, and probably not at all comprehended) from King James, whose representative, the governor, wished particularly to see Massasoit. It appears from the record, written apparently by Winslow himself, that Massasoit made no particular reply to this harangue, but paid very particular attention to Winslow’s sword and armor, and proposed at once to begin business by buying them. This, however, was refused, but Winslow induced Massasoit to cross a brook between the English and himself, taking with him twenty of his Indians, who were bidden to leave their bows and arrows behind them. Beyond the brook, he was met by Captain Standish, with an escort of six armed men, who exchanged salutations and attended him to one of the best, but unfinished, houses in the village. Here a green rug was spread on the floor and three or four cushions. The governor, Bradford, then entered the house, followed by three or four soldiers and preceded by a flourish[37] from a drum and trumpet, which quite delighted and astonished the Indians. It was a deference paid to their Sachem. He and the governor then kissed each other, as it is recorded, sat down together, and regaled themselves with an entertainment. The feast is recorded by the early narrator as consisting chiefly of strong waters, a “thing the savages love very well,” it is said; “and the Sachem took such a large draught of it at once as made him sweat all the time he staied.”[5]

A substantial treaty of peace was made on this occasion, one immortalized by the fact that it was the first made with the Indians of New England. It is the unquestioned testimony of history that the negotiation was remembered and followed by both sides for half a century: nor was Massasoit, or any of the Wampanoags during his lifetime, convicted of having violated or having attempted to violate any of its provisions. This was a great achievement! Do you ask what price bought all this? The price practically paid for all the vast domain and power granted to the white man consisted of the following items: “a pair of knives and a copper chain with a jewel in it, for the grand Sachem; and for his brother Quadequina, a knife, a jewel to hang in his ear, a pot of strong[38] waters, a good quantity of biscuit and a piece of butter.”[6]

Fair words, the proverb says, butter no parsnips, but the fair words of the white men had provided the opportunity for performing that process. The description preserved of the Indian chief by an eye-witness is as follows: “In his person he is a very lusty man in his best years, an able body, grave of countenance and spare of speech; in his attire little or nothing differing from the rest of his followers, only in a great chain of white bone beads about his neck; and at it, behind his neck, hangs a little bag of tobacco, which he drank, and gave us to drink (this being the phrase for that indulgence in those days, as is found in Ben Jonson and other authors). His face was painted with a sad red, like murrey (so called from the color of the Moors) and oiled, both head and face, that he looked greasily. All his followers likewise were in their faces, in part or in whole painted, some black, some red, some yellow, and some white, some with crosses and other antic works; some had skins on them and some naked: all strong, tall men in appearance.”[7]

All this which Dr. Young tells us would have been a good description of an Indian party under[39] Black Hawk, which was presented to the President at Washington as late as 1837; and also, I can say the same of such a party seen by myself, coming from a prairie in Kansas, then unexplored, in 1856.

The interchange of eatables was evidently at that period a pledge of good feeling, as it is to-day. On a later occasion, Captain Standish, with Isaac Alderton, went to visit the Indians, who gave them three or four groundnuts and some tobacco. The writer afterwards says: “Our governor bid them send the king’s kettle and filled it full of pease which pleased them well, and so they went their way.” It strikes the modern reader as if this were to make pease and peace practically equivalent, and as if the parties needed only a pun to make friends. It is doubtful whether the arrival of a conquering race was ever in the history of the world marked by a treaty so simple and therefore noble.

“This treaty with Massasoit,” says Belknap, “was the work of one day,” and being honestly intended on both sides, was kept with fidelity as long as Massasoit lived.[8] In September, 1639, Massasoit and his oldest son, Mooanam, afterwards called Wamsutta, came into the court at Plymouth and desired that this ancient league should remain inviolable, which was accordingly[40] ratified and confirmed by the government,[9] and lasted until it was broken by Philip, the successor of Wamsutta, in 1675. It is not my affair to discuss the later career of Philip, whose insurrection is now viewed more leniently than in its own day; but the spirit of it was surely quite mercilessly characterized by a Puritan minister, Increase Mather, who, when describing a battle in which old Indian men and women, the wounded and the helpless, were burned alive, said proudly, “This day we brought five hundred Indian souls to hell.”[10]

But the end of all was approaching. In 1623, Massasoit sent a messenger to Plymouth to say that he was ill, and Governor Bradford sent Mr. Winslow to him with medicines and cordials. When they reached a certain ferry, upon Winslow’s discharging his gun, Indians came to him from a house not far off who told him that Massasoit was dead and that day buried. As they came nearer, at about half an hour before the setting of the sun, another messenger came and told them that he was not dead, though there was no hope that they would find him living. Hastening on, they arrived late at night.

“When we came thither,” Winslow writes, “we found the house so full of men as we could[41] scarce get in, though they used their best diligence to make way for us. There were they in the midst of their charms for him, making such a hellish noise as it distempered us that were well, and therefore unlike to ease him that was sick. About him were six or eight women, who chafed his arms, legs and thighs to keep heat in him. When they had made an end of their charming, one told him that his friends, the English, were come to see him. Having understanding left, but his sight was wholly gone, he asked who was come. They told him Winsnow, for they cannot pronounce the letter l, but ordinarily n in place thereof. He desired to speak with me. When I came to him and they told him of it, he put forth his hand to me, which I took. When he said twice, though very inwardly: ‘Keen Winsnow?’ which is to say ‘Art thou Winslow?’ I answered: ‘Ahhe’; that is, ‘Yes.’ Then he doubled these words: ‘Matta neen wonckanet nanem, Winsnow!’ That is to say: ‘Oh, Winslow, I shall never see thee again!’ Then I called Hobbamock and desired him to tell Massasowat that the governor, hearing of his sickness, was sorry for the same; and though by many businesses he could not come himself, yet he sent me with such things for him as he thought most likely to do good in this extremity; and whereof if he pleased to take, I[42] would presently give him; which he desired, and having a confection of many comfortable conserves on the point of my knife, I gave him some, which I could scarce get through his teeth. When it was dissolved in his mouth, he swallowed the juice of it; whereat those that were about him much rejoiced, saying that he had not swallowed anything in two days before.”[11]

Then Winslow tells how he nursed the sick chief, sending messengers back to the governor for a bottle of drink, and some chickens from which to make a broth for his patient. Meanwhile he dissolved some of the confection in water and gave it to Massasoit to drink; within half an hour the Indian improved. Before the messengers could return with the chickens, Winslow made a broth of meal and strawberry-leaves and sassafras-root, which he strained through his handkerchief and gave the chief, who drank at least a pint of it. After this his sight mended more and more, and all rejoiced that the Englishman had been the means of preserving the life of Massasoit. At length the messengers returned with the chickens, but Massasoit, “finding his stomach come to him, ... would not have the chickens killed, but kept them for breed.”

From far and near his followers came to see their restored chief, who feelingly said: “Now I see the English are my friends and love me; and whilst I live I will never forget this kindness they have showed me.”

It would be interesting, were I to take the time, to look into the relations of Massasoit with others, especially with Roger Williams; but this has been done by others, particularly in the somewhat imaginative chapter of my old friend, Mr. Butterworth, and I have already said enough. Nor can I paint the background of that strange early society of Rhode Island, its reaction from the stern Massachusetts rigor, and its quaint and varied materials. In that new state, as Bancroft keenly said, there were settlements “filled with the strangest and most incongruous elements ... so that if a man had lost his religious opinions, he might have been sure to find them again in some village in Rhode Island.”

Meanwhile “the old benevolent sachem, Massasoit,” says Drake’s “Book of the Indians,” “having died in the winter of 1661-2,” so died, a few months after, his oldest son, Alexander. Then came by regular succession, Philip, the next brother, of whom the historian Hubbard says that for his “ambitious and haughty spirit he was nicknamed ‘King Philip.’” From[44] this time followed warlike dismay in the colonies, ending in Philip’s piteous death.

As a long-deferred memorial to Massasoit with all his simple and modest virtues, a tablet has now been reverently dedicated, in the presence of two of the three surviving descendants of the Indian chief, one of these wearing his ancestral robes. The dedication might well close as it did with the noble words of Young’s “Night Thoughts,” suited to such an occasion:—

These were the words in which Fitz-Greene Halleck designated Cooper’s substantial precedence in American novel-writing. Apart from this mere priority in time,—he was born at Burlington, New Jersey, September 15, 1789, and died at Cooperstown, New York, September 14, 1851,—he rendered the unique service of inaugurating three especial classes of fiction,—the novel of the American Revolution, the Indian novel, and the sea novel. In each case he wrote primarily for his own fellow countrymen, and achieved fame first at their hands; and in each he produced a class of works which, in spite of their own faults and of the somewhat unconciliatory spirit of their writer, have secured a permanence and a breadth of range unequaled in English prose fiction, save by Scott alone. To-day the sale of his works in his own language remains unabated; and one has only to look over the catalogues of European booksellers in order to satisfy himself that this popularity continues, undiminished, through the medium of translation.[48] It may be safely said of him that no author of fiction in the English language, except Scott, has held his own so well for half a century after death. Indeed, the list of various editions and versions of his writings in the catalogues of German booksellers often exceeds that of Scott. This is not in the slightest degree due to his personal qualities, for these made him unpopular, nor to personal manœuvring, for this he disdained. He was known to refuse to have his works even noticed in a newspaper for which he wrote, the “New York Patriot.” He never would have consented to review his own books, as both Scott and Irving did, or to write direct or indirect puffs of himself, as was done by Poe and Whitman. He was foolishly sensitive to criticism, and unable to conceal it; he was easily provoked to a quarrel; he was dissatisfied with either praise or blame, and speaks evidently of himself in the words of the hero of “Miles Wallingford,” when he says: “In scarce a circumstance of my life that has brought me in the least under the cognizance of the public have I ever been judged justly.” There is no doubt that he himself—or rather the temperament given him by nature—was to blame for this, but the fact is unquestionable.

Add to this that he was, in his way and in what was unfortunately the most obnoxious way, a[49] reformer. That is, he was what may be called a reformer in the conservative direction,—he belabored his fellow citizens for changing many English ways and usages, and he wished them to change these things back again, immediately. In all this he was absolutely unselfish, but utterly tactless; and inasmuch as the point of view he took was one requiring the very greatest tact, the defect was hopeless. As a rule, no man criticises American ways so unsuccessfully as an American who has lived many years in Europe. The mere European critic is ignorant of our ways and frankly owns it, even if thinking the fact but a small disqualification; while the American absentee, having remained away long enough to have forgotten many things and never to have seen many others, may have dropped hopelessly behindhand as to the facts, yet claims to speak with authority. Cooper went even beyond these professional absentees, because, while they are usually ready to praise other countries at the expense of America, Cooper, with heroic impartiality, dispraised all countries, or at least all that spoke English. A thoroughly patriotic and high-minded man, he yet had no mental perspective, and made small matters as important as great. Constantly reproaching America for not being Europe, he also satirized Europe for being what it was.

As a result, he was for a time equally detested by the press of both countries. The English, he thought, had “a national propensity to blackguardism,” and certainly the remarks he drew from them did something to vindicate the charge. When the London “Times” called him “affected, offensive, curious, and ill-conditioned,” and “Fraser’s Magazine,” “a liar, a bilious braggart, a full jackass, an insect, a grub, and a reptile,” they clearly left little for America to say in that direction. Yet Park Benjamin did his best, or his worst, when he called Cooper (in Greeley’s “New Yorker”) “a superlative dolt and the common mark of scorn and contempt of every well-informed American”; and so did Webb, when he pronounced the novelist “a base-minded caitiff who had traduced his country.” Not being able to reach his English opponents, Cooper turned on these Americans, and spent years in attacking Webb and others through the courts, gaining little and losing much through the long vicissitudes of petty local lawsuits. The fact has kept alive their memory; but for Lowell’s keener shaft, “Cooper has written six volumes to show he’s as good as a lord,” there was no redress. The arrow lodged and split the target.

Like Scott and most other novelists, Cooper was rarely successful with his main characters,[51] but was saved by his subordinate ones. These were strong, fresh, characteristic, human; and they lay, as I have already said, in several different directions, all equally marked. If he did not create permanent types in Harvey Birch the spy, Leather-Stocking the woodsman, Long Tom Coffin the sailor, Chingachgook the Indian, then there is no such thing as the creation of characters in literature. Scott was far more profuse and varied, but he gave no more of life to individual personages, and perhaps created no types so universally recognized. What is most remarkable is that, in the case of the Indian especially, Cooper was not only in advance of the knowledge of his own time, but of that of the authors who immediately followed him. In Parkman and Palfrey, for instance, the Indian of Cooper vanishes and seems wholly extinguished; but under the closer inspection of Alice Fletcher and Horatio Hale, the lost figure reappears, and becomes more picturesque, more poetic, more thoughtful, than even Cooper dared to make him. The instinct of the novelist turned out more authoritative than the premature conclusions of a generation of historians.

It is only women who can draw the commonplace, at least in English, and make it fascinating. Perhaps only two English women have done this, Jane Austen and George Eliot; while[52] in France George Sand has certainly done it far less well than it has been achieved by Balzac and Daudet. Cooper never succeeded in it for a single instant, and even when he has an admiral of this type to write about, he puts into him less of life than Marryat imparts to the most ordinary midshipman. The talk of Cooper’s civilian worthies is, as Professor Lounsbury has well said,—in what is perhaps the best biography yet written of any American author,—“of a kind not known to human society.” This is doubtless aggravated by the frequent use of thee and thou, yet this, which Professor Lounsbury attributes to Cooper’s Quaker ancestry, was in truth a part of the formality of the old period, and is found also in Brockden Brown. And as his writings conform to their period in this, so they did in other respects: describing every woman, for instance, as a “female,” and making her to be such as Cooper himself describes the heroine of “Mercedes of Castile” to be when he says, “Her very nature is made up of religion and female decorum.” Scott himself could also draw such inane figures, yet in Jeanie Deans he makes an average Scotch woman heroic, and in Meg Merrilies and Madge Wildfire he paints the extreme of daring self-will. There is scarcely a novel of Scott’s where some woman does not show qualities which[53] approach the heroic; while Cooper scarcely produced one where a woman rises even to the level of an interesting commonplaceness. She may be threatened, endangered, tormented, besieged in forts, captured by Indians, but the same monotony prevails. So far as the real interest of Cooper’s story goes, it might usually be destitute of a single “female,” that sex appearing chiefly as a bundle of dry goods to be transported, or as a fainting appendage to the skirmish. The author might as well have written the romance of an express parcel.

His long introductions he shared with the other novelists of the day, or at least with Scott, for both Miss Austen and Miss Edgeworth are more modern in this respect and strike more promptly into the tale. His loose-jointed plots are also shared with Scott, but Cooper knows as surely as his rival how to hold the reader’s attention when once grasped. Like Scott’s, too, is his fearlessness in giving details, instead of the vague generalizations which were then in fashion, and to which his academical critics would have confined him. He is indeed already vindicated in some respects by the advance of the art he pursued; where he led the way, the best literary practice has followed. The “Edinburgh Review” exhausted its heavy artillery upon him for his accurate descriptions of costume and[54] localities, and declared that they were “an epilepsy of the fancy,” and that a vague general account would have been far better. “Why describe the dress and appearance of an Indian chief, down to his tobacco-stopper and button-holes?” We now see that it is this very habit which has made Cooper’s Indian a permanent figure in literature, while the Indians of his predecessor, Charles Brockden Brown, were merely dusky spectres. “Poetry or romance,” continued the “Edinburgh Review,” “does not descend into the particulars,” this being the same fallacy satirized by Ruskin, whose imaginary painter produced a quadruped which was a generalization between a pony and a pig. Balzac, who risked the details of buttons and tobacco pipes as fearlessly as Cooper, said of “The Pathfinder,” “Never did the art of writing tread closer upon the art of the pencil. This is the school of study for literary landscape painters.” He says elsewhere: “If Cooper had succeeded in the painting of character to the same extent that he did in the painting of the phenomena of nature, he would have uttered the last word of our art.” Upon such praise as this the reputation of James Fenimore Cooper may well rest.

When, in 1834, the historian Jared Sparks undertook the publication of a “Library of American Biography,” he included in the very first volume—with a literary instinct most creditable to one so absorbed in the severer paths of history—a memoir of Charles Brockden Brown by W. H. Prescott. It was an appropriate tribute to the first imaginative writer worth mentioning in America,—he having been born in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on January 17, 1771, and died there of consumption on February 22, 1810,—and to one who was our first professional author. He was also the first to exert a positive influence, across the Atlantic, upon British literature, laying thus early a few modest strands towards an ocean-cable of thought. As a result of this influence, concealed doors opened in lonely houses, fatal epidemics laid cities desolate, secret plots were organized, unknown persons from foreign lands died in garrets, usually leaving large sums of money; the honor of innocent women was constantly endangered, though usually saved in time; people were subject to somnambulism and[58] general frenzy; vast conspiracies were organized with small aims and smaller results. His books, published between 1798 and 1801, made their way across the ocean with a promptness that now seems inexplicable; and Mrs. Shelley, in her novel of “The Last Man,” founds her whole description of an epidemic which nearly destroyed the human race, on “the masterly delineations of the author of ‘Arthur Mervyn.’”

Shelley himself recognized his obligations to Brown; and it is to be remembered that Brown himself was evidently familiar with Godwin’s philosophical writings, and that he may have drawn from those of Mary Wollstonecraft his advanced views as to the rights and education of women, a subject on which his first book, “Alcuin,” offered the earliest American protest. Undoubtedly his books furnished a point of transition from Mrs. Radcliffe, of whom he disapproved, to the modern novel of realism, although his immediate influence and, so to speak, his stage properties, can hardly be traced later than the remarkable tale, also by a Philadelphian, called “Stanley; or the Man of the World,” first published in 1839 in London, though the scene was laid in America. This book was attributed, from its profuse literary quotations, to Edward Everett, but was soon understood to be the work of a very young man of twenty-one, Horace[59] Binney Wallace. In this book the influence of Bulwer and Disraeli is palpable, but Brown’s concealed chambers and aimless conspiracies and sudden mysterious deaths also reappear in full force, not without some lingering power, and then vanish from American literature forever.

Brown’s style, and especially the language put by him into the mouths of his characters, is perhaps unduly characterized by Professor Woodberry as being “something never heard off the stage of melodrama.” What this able critic does not sufficiently recognize is that the general style of the period at which they were written was itself melodramatic; and that to substitute what we should call simplicity would then have made the picture unfaithful. One has only to read over the private letters of any educated family of that period to see that people did not then express themselves as they now do; that they were far more ornate in utterance, more involved in statement, more impassioned in speech. Even a comparatively terse writer like Prescott, in composing Brown’s biography only sixty years ago, shows traces of the earlier period. Instead of stating simply that his hero was a born Quaker, he says of him: “He was descended from a highly respectable family, whose parents were of that estimable sect who came over with William Penn, to seek an asylum[60] where they might worship their Creator unmolested, in the meek and humble spirit of their own faith.” Prescott justly criticises Brown for saying, “I was fraught with the apprehension that my life was endangered”; or “his brain seemed to swell beyond its continent”; or “I drew every bolt that appended to it”; or “on recovering from deliquium, you found it where it had been dropped”; or for resorting to the circumlocution of saying, “by a common apparatus that lay beside my head I could produce a light,” when he really meant that he had a tinder-box. The criticism on Brown is fair enough, yet Prescott himself presently takes us halfway back to the florid vocabulary of that period, when, instead of merely saying that his hero was fond of reading, he tells us that “from his earliest childhood Brown gave evidence of studious propensities, being frequently noticed by his father on his return from school poring over some heavy tome.” If the tome in question was Johnson’s dictionary, as it may have been, it would explain both Brown’s style of writing and the milder amplifications of his biographer. Nothing is more difficult to tell, in the fictitious literature of even a generation or two ago, where a faithful delineation ends and where caricature begins. The four-story signatures of Micawber’s letters, as represented by[61] Dickens, go but little beyond the similar courtesies employed in a gentlewoman’s letters in the days of Anna Seward. All we can say is that within a century, for some cause or other, English speech has grown very much simpler, and human happiness has increased in proportion.

In the preface to his second novel, “Edgar Huntley,” Brown announces it as his primary purpose to be American in theme, “to exhibit a series of adventures growing out of our own country,” adding, “That the field of investigation opened to us by our own country should differ essentially from those which exist in Europe may be readily conceived.” He protests against “puerile superstition and exploded manners, Gothic castles and chimeras,” and adds: “The incidents of Indian hostility and the perils of the western wilderness are far more suitable.” All this is admirable, but unfortunately the inherited thoughts and methods of the period hung round him to cloy his style, even after his aim was emancipated. It is to be remembered that almost all his imaginative work was done in early life, before the age of thirty, and before his powers became mature. Yet with all his drawbacks he had achieved his end, and had laid the foundation for American fiction.

With all his inflation of style, he was undoubtedly, in his way, a careful observer. The proof of this is that he has preserved for us many minor points of life and manners which make the Philadelphia of a century ago now more familiar to us than is any other American city of that period. He gives us the roving Indian; the newly arrived French musician with violin and monkey; the one-story farmhouses, where boarders are entertained at a dollar a week; the gray cougar amid caves of limestone. We learn from him “the dangers and toils of a midnight journey in a stage coach in America. The roads are knee deep in mire, winding through crags and pits, while the wheels groan and totter and the curtain and roof admit the wet at a thousand seams.” We learn the proper costume for a youth of good fortune and family,—“nankeen coat striped with green, a white silk waistcoat elegantly needle-wrought, cassimere pantaloons, stockings of variegated silk, and shoes that in their softness vie with satin.” When dressing himself, this favored youth ties his flowing locks with a black ribbon. We find from him that “stage boats” then crossed twice a day from New York to Staten Island, and we discover also with some surprise that negroes were freely admitted to ride in stages in Pennsylvania,[63] although they were liable, half a century later, to be ejected from street-cars. We learn also that there were negro free schools in Philadelphia. All this was before 1801.

It has been common to say that Brown had no literary skill, but it would be truer to say that he had no sense of literary construction. So far as skill is tested by the power to pique curiosity, Brown had it; his chapters almost always end at a point of especial interest, and the next chapter, postponing the solution, often diverts the interest in a wholly new direction. But literary structure there is none: the plots are always cumulative and even oppressive; narrative is inclosed in narrative; new characters and complications come and go, while important personages disappear altogether, and are perhaps fished up with difficulty, as with a hook and line, on the very last page. There is also a total lack of humor, and only such efforts at vivacity as this: “Move on, my quill! wait not for my guidance. Reanimated with thy master’s spirit, all airy light. A heyday rapture! A mounting impulse sways him; lifts him from the earth.” There is so much of monotony in the general method, that one novel seems to stand for all; and the same modes of solution reappear so often,—somnambulism,[64] ventriloquism, yellow fever, forged letters, concealed money, secret closets,—that it not only gives a sense of puerility, but makes it very difficult to recall, as to any particular passage, from which book it came.

There has been in America no such instance of posthumous reputation as in the case of Thoreau. Poe and Whitman may be claimed as parallels, but not justly. Poe, even during his life, rode often on the very wave of success, until it subsided presently beneath him, always to rise again, had he but made it possible. Whitman gathered almost immediately a small but stanch band of followers, who have held by him with such vehemence and such flagrant imitation as to keep his name defiantly in evidence, while perhaps enhancing the antagonism of his critics. Thoreau could be egotistical enough, but was always high-minded; all was open and aboveboard; one could as soon conceive of self-advertising by a deer in the woods or an otter of the brook. He had no organized clique of admirers, nor did he possess even what is called personal charm,—or at least only that piquant attraction which he himself found in wild apples. As a rule, he kept men at a distance, being busy with his own affairs. He left neither wife nor children to attend to his memory; and his sister seemed for a time to repress[68] the publication of his manuscripts. Yet this plain, shy, retired student, who when thirty-two years old carried the unsold edition of his first book upon his back to his attic chamber; who died at forty-four still unknown to the general public; this child of obscurity, who printed but two volumes during his lifetime, has had ten volumes of his writings published by others since his death, while four biographies of him have been issued in America (by Emerson, Channing, Sanborn, and Jones), besides two in England (by Page and Salt).

Thoreau was born in Boston on July 12, 1817, but spent most of his life in Concord, Massachusetts, where he taught school and was for three years an inmate of the family of Ralph Waldo Emerson, practicing at various times the art of pencil-making—his father’s occupation—and also of surveying, carpentering, and housekeeping. So identified was he with the place that Emerson speaks of it in one case as Thoreau’s “native town.” Yet from that very familiarity, perhaps, the latter was underestimated by many of his neighbors, as was the case in Edinburgh with Sir Walter Scott, as Mrs. Grant of Laggan describes.

When I was endeavoring, about 1870, to persuade Thoreau’s sister to let some one edit his journals, I invoked the aid of Judge Hoar, then[69] lord of the manor in Concord, who heard me patiently through, and then said: “Whereunto? You have not established the preliminary point. Why should any one wish to have Thoreau’s journals printed?” Ten years later, four successive volumes were made out of these journals by the late H. G. O. Blake, and it became a question if the whole might not be published. I hear from a local photograph dealer in Concord that the demand for Thoreau’s pictures now exceeds that for any other local celebrity. In the last sale catalogue of autographs which I have encountered, I find a letter from Thoreau priced at $17.50, one from Hawthorne valued at the same, one from Longfellow at $4.50 only, and one from Holmes at $3, each of these being guaranteed as an especially good autograph letter. Now the value of such memorials during a man’s life affords but a slight test of his permanent standing,—since almost any man’s autograph can be obtained for two postage-stamps if the request be put with sufficient ingenuity;—but when this financial standard can be safely applied more than thirty years after a man’s death, it comes pretty near to a permanent fame.

It is true that Thoreau had Emerson as the editor of four of his posthumous volumes; but it is also true that he had against him the vehement[70] voice of Lowell, whose influence as a critic was at that time greater than Emerson’s. It will always remain a puzzle why it was that Lowell, who had reviewed Thoreau’s first book with cordiality in the “Massachusetts Quarterly Review,” and had said to me afterwards, on hearing him compared to Izaak Walton, “There is room for three or four Waltons in Thoreau,” should have written the really harsh attack on the latter which afterwards appeared, and in which the plain facts were unquestionably perverted. To transform Thoreau’s two brief years of study and observation at Walden, within two miles of his mother’s door, into a life-long renunciation of his fellow men; to complain of him as waiving all interest in public affairs when the great crisis of John Brown’s execution had found him far more awake to it than Lowell was,—this was only explainable by the lingering tradition of that savage period of criticism, initiated by Poe, in whose hands the thing became a tomahawk. As a matter of fact, the tomahawk had in this case its immediate effect; and the English editor and biographer of Thoreau has stated that Lowell’s criticism is to this day the great obstacle to the acceptance of Thoreau’s writings in England. It is to be remembered, however, that Thoreau was not wholly of English but partly of French origin, and was, it might[71] be added, of a sort of moral-Oriental, or Puritan Pagan temperament. With a literary feeling even stronger than his feeling for nature,—the proof of this being that he could not, like many men, enjoy nature in silence,—he put his observations always on the level of literature, while Mr. Burroughs, for instance, remains more upon the level of journalism. It is to be doubted whether any author under such circumstances would have been received favorably in England; just as the poems of Emily Dickinson, which have shafts of profound scrutiny that often suggest Thoreau, had an extraordinary success at home, but fell hopelessly dead in England, so that the second volume was never even published.

Lowell speaks of Thoreau as “indolent”; but this is, as has been said, like speaking of the indolence of a self-registering thermometer. Lowell objects to him as pursuing “a seclusion that keeps him in the public eye”; whereas it was the public eye which sought him; it was almost as hard to persuade him to lecture (crede experto) as it was to get an audience for him when he had consented. He never proclaimed the intrinsic superiority of the wilderness, as has been charged, but pointed out better than any one else has done its undesirableness as a residence, ranking it only as “a resource and[72] a background.” “The partially cultivated country it is,” he says, “which has chiefly inspired, and will continue to inspire, the strains of poets such as compose the mass of any literature.” “What is nature,” he elsewhere says, “unless there is a human life passing within it? Many joys and many sorrows are the lights and shadows in which she shines most beautiful.” This is the real and human Thoreau, who often whimsically veiled himself, but was plainly enough seen by any careful observer. That he was abrupt and repressive to bores and pedants, that he grudged his time to them and frequently withdrew himself, was as true of him as of Wordsworth or Tennyson. If they were allowed their privacy, though in the heart of England, an American who never left his own broad continent might at least be allowed his privilege of stepping out of doors. The Concord school-children never quarreled with this habit, for he took them out of doors with him and taught them where the best whortleberries grew.

His scholarship, like his observation of nature, was secondary to his function as poet and writer. Into both he carried the element of whim; but his version of the “Prometheus Bound” shows accuracy, and his study of birds and plants shows care. It must be remembered that he antedated the modern school, classed[73] plants by the Linnæan system, and had necessarily Nuttall for his elementary manual of birds. Like all observers, he left whole realms uncultivated; thus he puzzles in his journal over the great brown paper cocoon of the Attacus Cecropia, which every village boy brings home from the winter meadows. If he has not the specialized habit of the naturalist of to-day, neither has he the polemic habit; firm beyond yielding, as to the local facts of his own Concord, he never quarrels with those who have made other observations elsewhere; he is involved in none of those contests in which palæontologists, biologists, astronomers, have wasted so much of their lives.

His especial greatness is that he gives us standing-ground below the surface, a basis not to be washed away. A hundred sentences might be quoted from him which make common observers seem superficial and professed philosophers trivial, but which, if accepted, place the realities of life beyond the reach of danger. He was a spiritual ascetic, to whom the simplicity of nature was luxury enough; and this, in an age of growing expenditure, gave him an unspeakable value. To him, life itself was a source of joy so great that it was only weakened by diluting it with meaner joys. This was the standard to which he constantly held his contemporaries.[74] “There is nowhere recorded,” he complains, “a simple and irrepressible satisfaction with the gift of life, any memorable praise of God.... If the day and the night are such that you greet them with joy, and life emits a fragrance, like flowers and sweet-scented herbs,—is more elastic, starry, and immortal,—that is your success.” This was Thoreau, who died unmarried at Concord, Massachusetts, May 6, 1862.

The phrase “foot-note person” was first introduced into our literature by one of the most acute and original of the anonymous writers in the “Atlantic Monthly” (July, 1906), one by whose consent I am permitted to borrow it for my present purpose. Its originator himself suggests, as an illustration of what he means, the close relation which existed through life between Ralph Waldo Emerson and his less famous Concord neighbor, Amos Bronson Alcott. The latter was doubtless regarded by the world at large as a mere “foot-note” to his famous friend, while he yet was doubtless the only literary contemporary to whom Emerson invariably and candidly deferred, regarding him, indeed, as unequivocally the leading philosophic or inspirational mind of his day. Let this “foot-note,” then, be employed as the text for frank discussion of what was, perhaps, the most unique and picturesque personality developed during the Transcendental period of our American literature. Let us consider the career of one who was born with as little that seemed advantageous[78] in his surroundings as was the case with Abraham Lincoln, or John Brown of Ossawatomie, and who yet developed in the end an individuality as marked as that of Poe or Walt Whitman.

In looking back on the intellectual group of New England, eighty years ago, nothing is more noticeable than its birth in a circle already cultivated, at least according to the standard of its period. Emerson, Channing, Bryant, Longfellow, Hawthorne, Holmes, Lowell, even Whittier, were born into what were, for the time and after their own standard, cultivated families. They grew up with the protection and stimulus of parents and teachers; their early biographies offer nothing startling. Among them appeared, one day, this student and teacher, more serene, more absolutely individual, than any one of them. He had indeed, like every boy born in New England, some drop of academic blood within his traditions, but he was born in the house of his grandfather, a poor farmer in Wolcott, Connecticut, on November 29, 1799. He went to the most primitive of wayside schools, and was placed at fourteen as apprentice in a clock factory; was for a few years a traveling peddler, selling almanacs and trinkets; then wandered as far as North Carolina and Virginia in a similar traffic; then became[79] a half-proselyte among Quakers in North Carolina; then a school-teacher in Connecticut; always poor, but always thoughtful, ever gravitating towards refined society, and finally coming under the influence of that rare and high-minded man, the Rev. Samuel J. May, and placing himself at last in the still more favored position of Emerson’s foot-note. When that took place, it suddenly made itself clear to the whole Concord circle that there was not one among them so serene, so equable, so dreamy, yet so constitutionally a leader, as this wandering child of the desert. Of all the men known in New England, he seemed the one least likely to have been a country peddler.

Mr. Alcott first visited Concord, as Mr. Cabot’s memoir of Emerson tells us, in 1835, and in 1840 came there to live. But it was as early as May 19, 1837, that Emerson wrote to Margaret Fuller: “Mr. Alcott is the great man. His book [‘Conversations on the Gospels’] does him no justice, and I do not like to see it.... But he has more of the Godlike than any man I have ever seen and his presence rebukes and threatens and raises. He is a teacher.... If he cannot make intelligent men feel the presence of a superior nature, the worse for them; I can never doubt him.”[12] It is suggested by[80] Dr. W. T. Harris, one of the two joint biographers of Alcott, that the description in the last chapter of Emerson’s book styled “Nature,” finished in August, 1836, was derived from a study of Mr. Alcott, and it is certain that there was no man among Emerson’s contemporaries of whom thenceforward he spoke with such habitual deference. Courteous to all, it was to Alcott alone that he seemed to look up. Not merely Alcott’s abstract statements, but his personal judgments, made an absolutely unique impression upon his more famous fellow townsman. It is interesting to notice that Alcott, while staying first in Concord, “complained of lack of simplicity in A⸺, B⸺, C⸺, and D⸺ (late visitors from the city).” Emerson said approvingly to his son: “Alcott is right touchstone to test them, litmus to detect the acid.”[13] We cannot doubt that such a man’s own judgment was absolutely simple; and such was clearly the opinion held by Emerson, who, indeed, always felt somewhat easier when he could keep Alcott at his elbow in Concord. Their mutual confidence reminds one of what was said long since by Dr. Samuel Johnson, that poetry was like brown bread: those who made it in their own houses never quite liked the taste of what they got elsewhere.

And from the very beginning, this attitude was reciprocated. At another time during that same early period (1837), Alcott, after criticising Emerson a little for “the picture of vulgar life that he draws with a Shakespearian boldness,” closes with this fine tribute to the intrinsic qualities of his newly won friend: “Observe his style; it is full of genuine phrases from the Saxon. He loves the simple, the natural; the thing is sharply presented, yet graced by beauty and elegance. Our language is a fit organ, as used by him; and we hear classic English once more from northern lips. Shakespeare, Sidney, Browne, speak again to us, and we recognize our affinity with the fathers of English diction. Emerson is the only instance of original style among Americans. Who writes like him? Who can? None of his imitators, surely. The day shall come when this man’s genius shall shine beyond the circle of his own city and nation. Emerson’s is destined to be the high literary name of this age.”[14]

No one up to that time, probably, had uttered an opinion of Emerson quite so prophetic as this; it was not until four years later, in 1841, that even Carlyle received the first volume of Emerson’s “Essays” and said, “It is once more the voice of a man.” Yet from that[82] moment Alcott and Emerson became united, however inadequate their twinship might have seemed to others. Literature sometimes, doubtless, makes strange friendships. There is a tradition that when Browning was once introduced to a new Chinese ambassador in London, the interpreter called attention to the fact that they were both poets. Upon Browning’s courteously asking how much poetry His Excellency had thus far written, he replied, “Four volumes,” and when asked what style of poetic art he cultivated, the answer was, “Chiefly the enigmatical.” It is reported that Browning afterwards charitably or modestly added, “We felt doubly brothers after that.” It may have been in a similar spirit that Emerson and his foot-note might seem at first to have united their destinies.

Emerson at that early period saw many defects in Alcott’s style, even so far as to say that it often reminded him of that vulgar saying, “All stir and no go”; but twenty years later, in 1855, he magnificently vindicated the same style, then grown more cultivated and powerful, and, indeed, wrote thus of it: “I have been struck with the late superiority Alcott showed. His interlocutors were all better than he: he seemed childish and helpless, not apprehending or answering their remarks aright, and they masters of their[83] weapons. But by and by, when he got upon a thought, like an Indian seizing by the mane and mounting a wild horse of the desert, he overrode them all, and showed such mastery, and took up Time and Nature like a boy’s marble in his hand, as to vindicate himself.”[15]

A severe test of a man’s depth of observation lies always in the analysis he gives of his neighbor’s temperament; even granting this appreciation to be, as is sometimes fairly claimed, a woman’s especial gift. It is a quality which certainly marked Alcott, who once said, for instance, of Emerson’s combination of a clear voice with a slender chest, that “some of his organs were free, some fated.” Indeed, his power in the graphic personal delineations of those about him was almost always visible, as where he called Garrison “a phrenological head illuminated,” or said of Wendell Phillips, “Many are the friends of his golden tongue.” This quality I never felt more, perhaps, than when he once said, when dining with me at the house of James T. Fields, in 1862, and speaking of a writer whom I thought I had reason to know pretty well: “He has a love of wholeness; in this respect far surpassing Emerson.”

It is scarcely possible, for any one who recalls from his youth the antagonism and satire called[84] forth by Alcott’s “sayings” in the early “Dial,” to avoid astonishment at their more than contemptuous reception. Take, for example, in the very first number the fine saying on “Enthusiasm,” thus:—

“Believe, youth, that your heart is an oracle; trust her instinctive auguries; obey her divine leadings; nor listen too fondly to the uncertain echoes of your head. The heart is the prophet of your soul, and ever fulfils her prophecies; reason is her historian; but for the prophecy, the history would not be.... Enthusiasm is the glory and hope of the world. It is the life of sanctity and genius; it has wrought all miracles since the beginning of time.”

Or turn to the following (entitled: “IV. Immortality”):—