The Project Gutenberg eBook of A campaign in Mexico, by Benjamin Franklin Scribner

Title: A campaign in Mexico

Author: Benjamin Franklin Scribner

Release Date: September 8, 2022 [eBook #68938]

Language: English

Produced by: The Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

BATTLE

OF

BUENA VISTA

BY

“ONE WHO WAS THAR.”

“Variety is the spice of life.”

PHILADELPHIA:

JAMES GIHON.

AND FOR SALE BY ALL BOOKSELLERS AND COUNTRY MERCHANTS

SOUTH AND WEST.

1850.

In thus bringing myself before the public as an author, I offer no apology. I make no pretensions to literary merit. The following pages were written in the confusion and inconvenience of camp, with limited sources of information, and without any expectation of future publication. I offer nothing but a faithful description of my own feelings, and of incidents in the life of a volunteer. To such as may be interested in an unvarnished relation of facts, connected with the duties, fatigues and perils of a soldier’s life, I respectfully submit this volume.

B. F. SCRIBNER.

New Albany,

Indiana.

To the interest of a simple personal narrative, this volume adds the value of a faithful description of that part of a soldier’s duty in the camp and field, which is necessarily excluded from official accounts or general histories. It attracted in manuscript the attention of the publishers, as a work similar in spirit and purpose to Dana’s “Two Years before the Mast,” although necessarily less varied in incident, and less comprehensive in information than that very popular production.

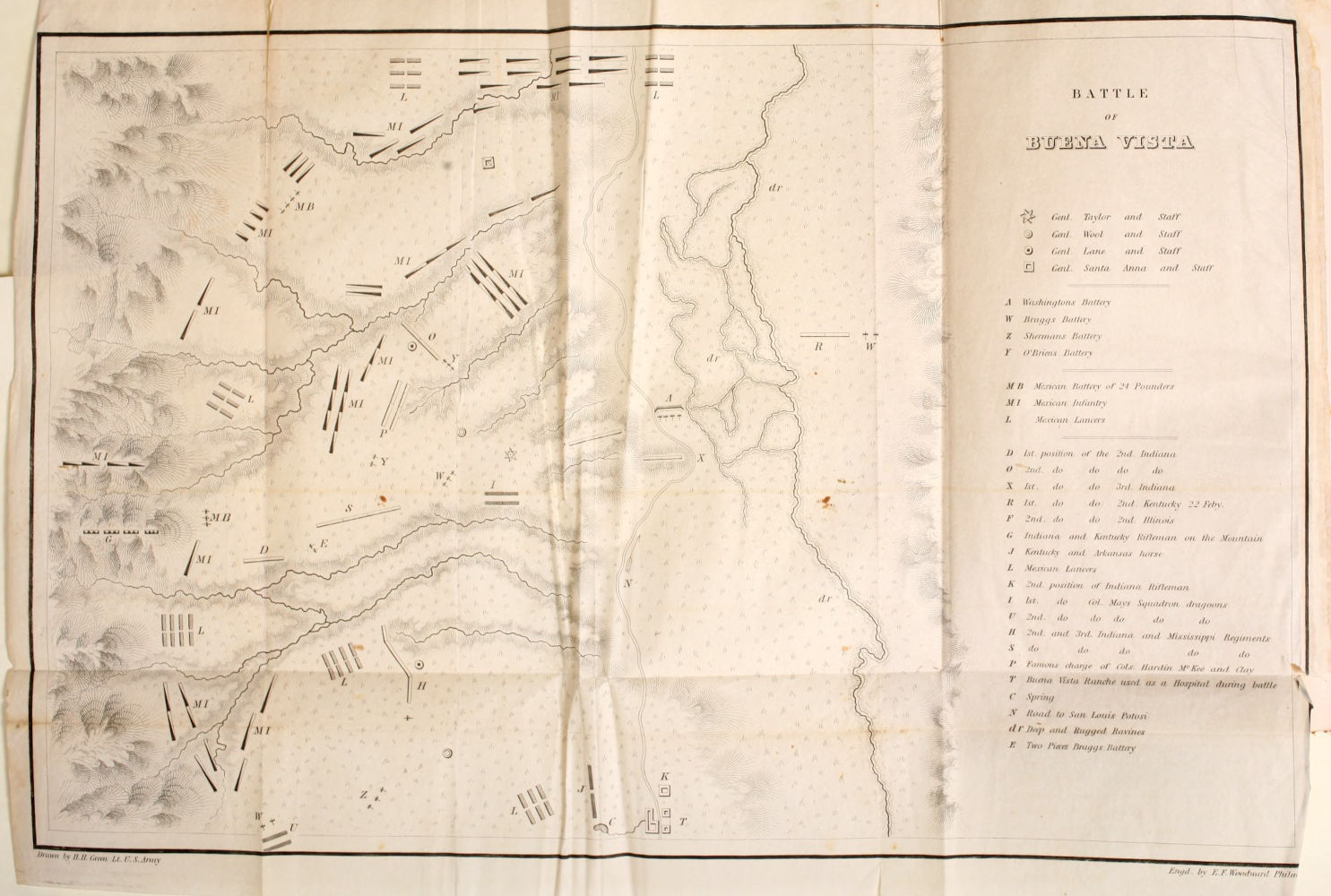

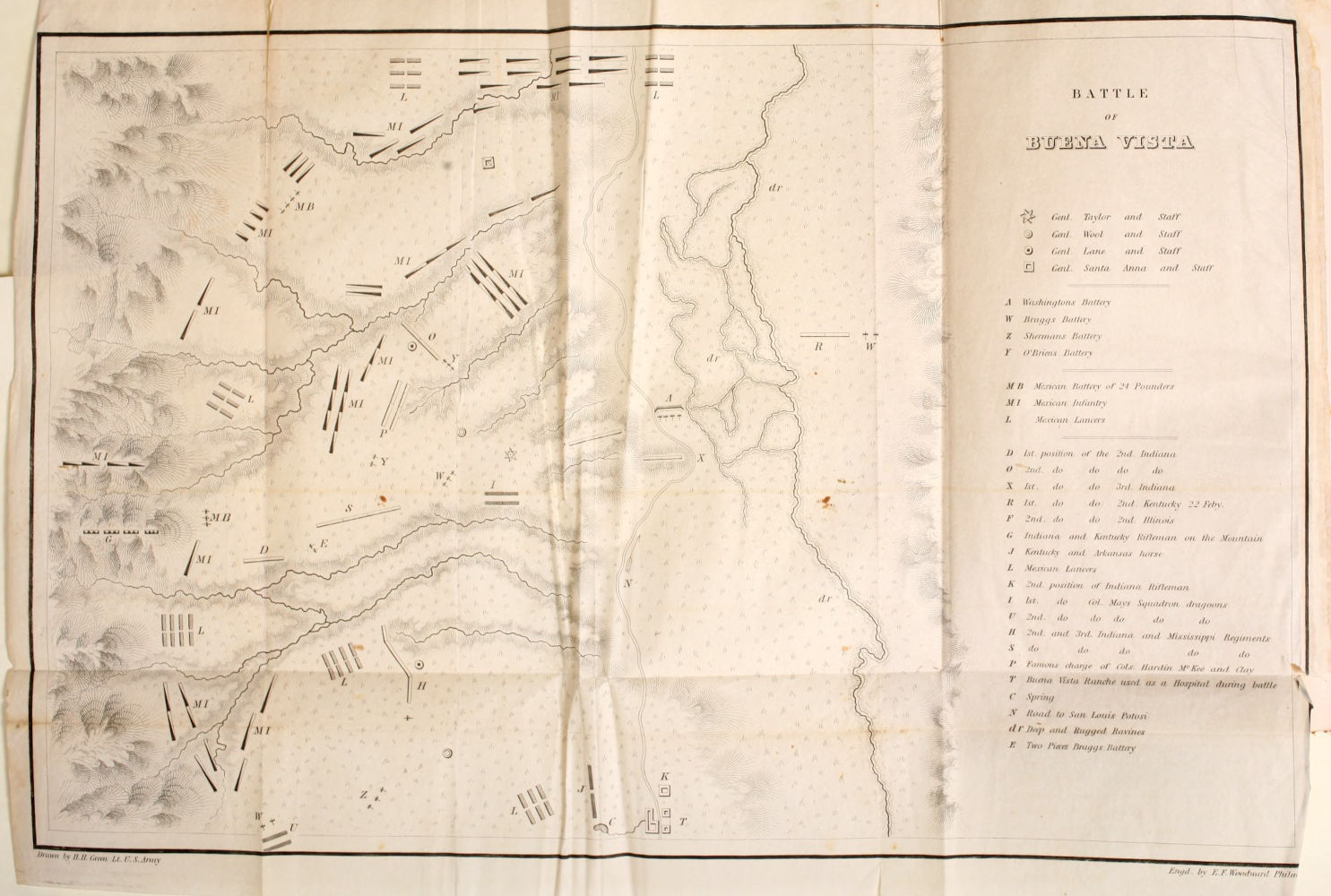

The map of the field of Buena Vista by Lieutenant Green, of the 15th infantry, is presented as the most accurate yet published, having been approved by many distinguished officers as a true representation of the ground, and of the relative positions of the corps of the American and Mexican armies, on the day of the battle. A careful examination of the map and references, will afford a clearer idea of the movements of both, and of the progress of the action, than any of the descriptions which have yet appeared.

[Pg 11]

July.—We left the New Albany wharf, July 11th, 1846, at one o’clock A.M., and are now winding our way to New Orleans, on the noble steamer Uncle Sam, en route to the wars in Mexico. I am wholly unable to describe my thoughts and emotions, at leaving my native home, with its endearing associations, and embarking upon a venturesome career of fatigue, privation, and danger. I stood upon the hurricane deck, and could see by the moonlight crowds of my fellow townsmen upon the bank, and in the intervals of the cannon’s roar, returned their encouraging cheers. As we glided down, the last objects that met my lingering gaze, were the white dresses and floating handkerchiefs of our fair friends. How few of us may return to receive their welcome!

I am becoming more and more impressed with the aristocracy of office. Those who hold commissions have the best pay, the best fare, and all the honor. The private performs the work, endures the privation, and when the toils and sufferings of the campaign are over, forgetfulness folds him gracefully in her capacious mantle. The cabin has been reserved for the staff and commissioned officers, while the non-commissioned and privates enjoy decks the best way they can. I now realize that when one takes up arms voluntarily in defence of his country’s institutions, he forfeits his claim to gentility, thereby rendering himself liable to all kinds of cold, cheerless inattention. Under a full appreciation of this fact, one of my companions and myself applied to the Captain of the steamer for a cabin passage. He granted our request, with the Colonel’s consent, and by paying extra ten dollars, we were permitted to occupy the[Pg 12] last remaining room, and enjoy the very great privilege of sitting at the same table with our titled superiors.

There are five companies on board, and all appear in good spirits. They are following the bent of their several inclinations. At a table above me is a group of “Greys” busily engaged in signing resolutions indicative of their disapprobation of the course of Gov. Whitcomb and his advisers, in officering and forming our regiments. I will not here try to show how all our plans have been frustrated, nor speak of the many discouraging circumstances under which we go away; suffice to say, I willingly signed the resolutions, which will be sent home for publication. I pause to listen to a song in which Prof. Goff appears to lead.

How pleasing are the impressions made upon the mind by a beautiful landscape, when advantageously seen and properly appreciated. We have just passed three islands lying almost side by side, thereby giving great width to the river. They are indeed beautiful. Viewed in the distance they appear like three huge tufts of grass.

12th.—Our noble craft is now ploughing the bosom of the “Great Father of Waters.” There is something truly sublime in beholding a mighty river moving on in its course, defying every resistance, and bearing silently on towards the ocean. There is a tiresomeness in the scenery upon the banks of this noble stream, when compared with the diversified character of that found upon either side of the beautiful Ohio.

It is remarked generally by those among us, accustomed to travelling, that a more orderly set of men they have never seen than the volunteers from Indiana. The Greys attract much attention by their jokes and animation. They lead in the dance, and three of their number take the front rank in music. Goff with his guitar, Tuley with his violin, and Matthews with his vocal accompaniments, constitute a musical trio, possessing power to cheer the soldier’s saddest hour. I have formed quite an agreeable acquaintance with the clerks of the boat, who manifest much interest in my future welfare. We have just passed the mouth of the Arkansas river, and I do not remember to have seen a single farmhouse for a distance of many miles, that indicates competency or convenience.

17th.—After a most delightful trip of five days we arrived at the great City of the South, and are now encamped on the “Battle[Pg 13] Ground” of the memorable 8th of January. We are almost deluged in water and mud, as it has rained almost every day since we left home. Having pitched our tents, several of us not particularly delighted with our new quarters, sought more congenial lodgings in the city, where we have remained ever since, but shall rendezvous and proceed to camp in the morning. In relation to my visit to the city, I shall not particularize except to say, that I delivered a letter of introduction kindly given me by a friend, and was joyfully recognized and received.

18th.—In pursuance of appointment, several of us met next morning at the Lower Market, negotiated with some Spaniards to take us in their sail-boat to the encampment, and were soon under way. Having arrived, we were forced to wade from the river to our tents, nearly to the knees in mud and water. We were truly in a sorry plight.

Some of the more enterprising in camp have greatly improved their condition, by laying cordwood in the bottom of their tents. Our condition is rendered more insupportable from the fact that the “Barracks” are so short a distance from us, presenting so much of comfort. We truly envy the regulars.

On the afternoon of the same day we received orders to strike tents and prepare for embarkation, which we joyfully obeyed. About midnight five companies were economically stowed under the hatches of the ship Gov. Davis. Our vessel, together with the Partheon, also containing Indiana troops, was soon towed onward to the Gulf.

19th.—We entered the Gulf next morning, and started upon our course with a fair wind, which, however, was of short duration. It soon commenced raining, and while I write, head winds impede our progress. Sea sickness and low spirits prevail. I have not yet been affected by the former, but am by no means realizing the pleasure trip, which some of my friends anticipated. If they could spend a night in the hold of this crowded vessel, they would not dream of citron groves or perfumed bowers.

20th.—In view of bettering my condition last night, I sought new lodgings by climbing up under the seat of an inverted yawl, where I slept, or tried to sleep; for the seat was short, narrow and hard,[Pg 14] as my bones can testify. It was also dark and stormy. The wind, rain, thunder, lightning, and creaking of the ship, as she heaved and surged through the billows, filled my mind with fear and anxiety, and kept me the whole night clinging to my narrow perching place. The sky is now clear, and wind fair, and the whole face of nature changed. We are gracefully gliding through the white spray, as it glitters in the sunbeams. The gorgeously tinted clouds are reflected upon the waves, in all the colors of the rainbow. This is the first time I have enjoyed a scene at sea, or fully realized being out sight of land. The undulating motion of the vessel, instead of making me sick, produces real pleasure. How exhilarating to feel ourselves riding up, up, and down, down with such regularity, fanned by the breezes that whistle through the sails!

21st.—Last evening was spent in organizing a debating club from the soldier fragments of the Caleopean Society, together with several new members. Grave and powerful speeches were made, and the question “Should the pay of volunteers be increased?” was discussed in a masterly manner. Arguments on both sides were unanswerable, and consequently unanswered. But as the exercises were got up more for amusement than improvement, they closed at an early hour, with a musical finale by the trio performers, who, with the captain of the ship, and others were convened upon the quarter-deck. We then stretched ourselves upon the deck, where we slept undisturbed, save when in the way of the sailors managing the ship.

This morning there appeared to be a general depression of spirits among the Greys. Complaints were heard from many who before had not been known to murmur. Our quarters between decks are truly unenviable, and the heat and stench almost insupportable. We had a fine treat to-day for dinner. The captain of the Greys had the good fortune to capture a young shark. It was very acceptably served up in the form of chowder. The wind is rather more favorable than it has yet been, but our progress is still slow, and it is the general opinion, it will be several days before we arrive at Point Isabel. Another and myself spent a portion of the afternoon upon the quarter deck reading plays from Shakspeare, after which we were all richly entertained in listening to the glowing descriptions of Napoleon and his marshals by Headley.

[Pg 15]

22d.—We have now fair wind, and are making fine speed. This morning the reading party was broken up by the fantastic gambols of a shoal of porpoises. This was quite an incident, and was hailed with much pleasure by the ennui-burdened passengers. At noon we found by the altitude, that we were but six hours’ sail from Galveston, and but half way to our destination. The captain says if the wind continues favorable, we shall, however, reach there in two days. I have felt gloomy and low spirited all day; owing, I suppose, to our uncomfortable situation.

23d.—This has been a miserable day. I do not think I ever spent one more unhappily. In fact, ever since I have been aboard this ship, I have had the blues most supremely. The crowd, the confusion, the dirt, the continual heaving of the vessel, and the dismal wo-begone countenances, of companions, are well calculated to fill the mind with reckless despondency.

24th.—We are now lying at anchor five miles from Brazos Santiago. About 8 o’clock, last night we witnessed the affecting sight of a burial at sea. It was indeed a thrilling scene. The moon and stars shone in all their brilliancy, as if indifferent to human woes. The body of the dead wrapped in his blanket—the soldier’s winding-sheet—was brought upon deck. A few words of consolation to friends composed the ceremony, and the body was lowered into the quiet deep, food for the “hyenas of the ocean.” I never shall forget the foreboding pause of the vessel, or the awful splash of the corpse as it fell into its watery grave. With sad emotions awakened in my bosom, I lay down upon the quarter-deck, and was ruminating upon the blighted hopes of this unfortunate youth, when I was aroused by an approaching storm. I sought shelter in the hold, but the crowd, the heat, the stench and the groanings of the sick, rendering it almost insupportable, I soon went aloft, preferring death by drowning to suffocation. The rain had ceased, but having lost my blanket, I was forced to take the wet deck and make the best of it. We shall have to remain on the vessel anchored in the offing, until conveyed ashore by steamers, to procure which the general and staff have just started in a long boat.

It is grateful, under any circumstances, to have friends, but how much additional pleasure it gives to find them among strangers. To find one here and there, who can sympathize with us in misfortune,[Pg 16] and feel interested in our welfare, when we least expect it, is calculated to give us better views of humanity. My thoughts were directed to this subject by the kindness of one of the mates of the ship. One day, when I was sitting in a rather musing mood, he introduced himself by familiarly accosting me with “Frank, how goes it?” After some conversation on matters of present interest, he inquired how I came to volunteer. I explained to him some of the causes. Among others I told him the “Spencer Greys” was an independent company formed several years ago, and chiefly composed of young men of New Albany. They had attracted much attention by the splendor of their uniform, their prompt and accurate movements in the drill, and their superior skill in target firing. They had won many prizes from neighboring companies, and thereby gained a celebrity, as possessing all the requisite qualifications to meet the foe, providing courage, that essential quality in a soldier, was not wanting. The call went forth for volunteers, and the inquiry was naturally made, “Where are the Greys?” To say nothing of the many motives that may prompt, pride to sustain the reputation already gained was sufficient for most of us. Our company was filled up, and we reported ourselves in readiness to the governor, and were duly accepted. Here my new friend was called to supper, and upon declining to accompany him, he kindly insisted I should receive a package of finely flavored cigars, upon which I can regale luxuriously.

25th.—We are still waiting in the most painful suspense and anxiety, for transportation ashore. For my own part I have made up my mind to bear everything like a philosopher. I entered upon this campaign, expecting to meet with privation and suffering; and judging from the past I am likely to realize my expectations. But trifling officers, and our very unpleasant situation on this filthy ship, are distresses that most of us overlooked in our calculation. Hereafter I am resolved to take everything easy, and complain as little as possible. Surfeited with bacon and hard mouldy bread, and in consideration of the frequent invitations from the mate to eat with him, I went to the steward, and negotiated for one dollar a day to take my meals at the table of the ship. After dinner I was beckoned to the lower cabin by my friend the mate, where he brought forth a rare collation, upon which we feasted like epicures. He opened his chest and showed me many curiosities from China, Java, and other[Pg 17] foreign countries. He also furnished a list of clothing, handkerchiefs, paper, pencils, and lastly his hammock, and begged me to take freely anything that would contribute to my comfort, as it would give him great pleasure to share with me. I declined receiving anything upon the ground that I was well provided, and could not carry his hammock, upon the comforts of which he so fully expatiated. I did, however, accept a superior cedar pencil, and warmly thanked him for his kind offers. He tells me he is a native of Boston, and a brother of Thayres, who is interested in the Boston and Liverpool line of steamers.

26th.—We are spending another Lord’s day in a heathenish manner. There are very few among us who spend the day differently from other days. We have not yet heard from our officers. Most of us have ceased to make calculations upon the future. How strangely is man subject to fluctuation of feeling!—with what suddenness the mind can fly from pleasure to pain! Last night I realized this in its fullest sense. I was seated astern luxuriating under the influence of a fine cigar, (thanks to my new friend,) and for the first time witnessed a clear sunset at sea. It was one of the most glorious scenes I ever beheld. The whole western sky was illuminated with the most gorgeous colors. The refulgent sun slowly sinking into the liquid blue until nearly immersed, sank at once, and a dark mist shot upward in his pathway to the clouds, which still retained their variegated tints. The whole scene was sublimely beautiful, and filled me with a joyful enthusiasm. The sea breeze, and the graceful rocking of the ship contributed to the effect. At such a moment how sweet is the thought of home, and the pleasures we long to share with loved ones left behind! These alluring reflections led me at length to a vein of melancholy, and produced a complete reaction in my whole feelings, which harmonized well with the changed and threatening aspect of the gathering clouds. We have just been thrown into a state of intense excitement by the arrival of a steamer which has taken three of our companies. The rest will remain till morning.

27th.—According to arrangement, the steamer arrived this morning, to transport us to the island. During the bustle of transfer, we were attracted to the stern of the ship, where the sailors had caught a shark, on a hook baited with bacon. Soon a great crowd[Pg 18] was collected, many climbing over the bulwarks and among the rigging to witness the captured fish. He was at length harpooned and shot, but was so large we could not conveniently bring it on board. Just as we were leaving the ship an affray took place between the steward and one of our men, which was soon participated in by the mates, and many of our party. Several blows passed, pistols were presented, and for a time serious consequences were feared, but the trouble was soon settled, when the mate understood the circumstances of the case. It appeared that one of our men and an officer claimed the same piece of ice, each one persisting in having bought it of the steward, to whom it was at last left to decide. He declared in favor of the officer and gave our man the lie, &c. Then came the knocks. But as I said before, everything was soon adjusted, and we separated with perfect good feeling. As we shoved off the mates and crew (steward excepted) leaned over the bulwarks, and gave us three hearty cheers. We landed at Brazos Santiago about noon, having had several hard thumps as we passed the reefs.

28th.—Yesterday about dark we pitched our tents, and ate our suppers, after which many of us proceeded to the beach, and enjoyed the luxury of sea-bathing. The convenience here for this refreshing operation cannot be surpassed. We waded out on the reefs and turning our faces to the shore, received the angry surges upon our backs, or facing them again could see one after another coming at regular distances, roaring like a cataract fall, and with foam and spray, dashing onward, like a white plumed army rushing to the charge. In regular succession they swept over our heads. We were all highly delighted with the novelty of the scene, which may be enjoyed, but not described. After rising this morning, the first thing was to repeat the exercises of last night, which greatly refreshed us, and sharpened our appetites for the morning meal. The scorching rays of the sun came down upon us “doubly distilled and highly concentrated;” the effects of which are, however, greatly counteracted by the sea-breeze. The thermometer stood yesterday at 90°.

The island is about 3¹⁄₂ miles wide, and very prolific in oysters, clams, crabs and fish. It may be compared to a sand bar occasionally diversified by little mounds, which are moved about by the storms that visit it. I am told that not long ago several families were destroyed by one of these dreadful tempests. One of our[Pg 19] officers, when walking along the beach the other day, unconsciously trod upon the exposed body of a man partially decayed, that two weeks ago was buried six feet in the sand. I am informed that the 1st Indiana regiment will leave for the Rio Grande in two days. If this be the case, our stay here will not be long. There are about 5000 troops here, most of whom will leave before us. We are in fine health and spirits, and continually congratulating ourselves, upon our escape from the detested ship.

31st.—I have spent the last two days in running about, and in writing letters to my friends, one of which I shall here embody in my journal, as it contains all that has transpired since my last date:

“Having already delayed too long, in hopes of sending you some news, I will commence at once, as your facilities for obtaining the truth are not much better than mine. There are so many conflicting rumors continually floating about the camp, and orders arriving daily purporting to be from Gen. Taylor, that we are getting to believe nothing, and to make as few calculations upon the future as possible. I shall therefore send you nothing in the news line that I don’t think correct.

“The 1st and 3d Indiana regiments left yesterday for the Rio Grande, the mouth of which is eight miles down the beach. From thence they will be taken by steamboats up the river. We expect to start on to-morrow. Some say we will stop at Barita, and others at the head-quarters opposite Matamoras.

“I am sitting upon the sand and writing this, while some of the boys are cooking, others washing, and some enjoying the luxury of a sea bath, hunting shells, oysters, &c. We would all present a novel appearance, could you see us now. I sometimes almost lose my own identity. The sudden change of occupation and associations affects us all.

“The health of the company is good, and all are making the best of everything. We have but two or three sick, and they are recovering, except one, and he is very low. He has been prevailed upon to accept a discharge, and will return home in the first vessel. He is a good fellow, and all of us regret to part with him.

“General Lane has just returned from an interview with General Taylor, bearing orders for us to leave in the morning. Another election in our regiment for Colonel will take place this evening, and, if possible, I will send you the result.

[Pg 20]

“The day before yesterday another and myself obtained permission to visit Point Isabel. We accordingly set out early in the morning. After crossing the Brazos in a sail-boat, we first visited the hospital containing the sick and wounded of the 8th and 9th. The rooms were large and airy, and everything characterized by cleanliness and order. It is an affecting sight for an American to behold his countrymen wounded in carrying out the demands of his government, to see them with their legs and arms blown off, rendering them ever afterwards incapable of enjoying active life. I was surprised and delighted with the patience and good humor they exhibited, and with what good feeling the infantry and dragoons joked and rallied each other. The first instance was brought about by my addressing one of them with, ‘My friend you do not look much like a wounded man.’ Said he, ‘I wasn’t much hurt, but that man sitting on my right, belongs to May’s dragoons, who have so immortalized themselves. He was shot all over with six pounders.’ The one pointed out pleasantly rejoined. ‘You are jealous because we fought harder than you did.’ Then turning to us he continued: ‘Yes, the infantry got into a difficulty and cried, “come and help us;” that was enough, so we rode up and saved them; now they envy us our distinction.’ ‘No we don’t,’ replied the other, ‘no we don’t. We know you did all the fighting. Uncle Sam could not get along without you.’ ‘Do you see,’ said the dragoon, still addressing us, ‘how they try to take away our laurels? I will not talk with my inferiors. You know our privates rank with their orderly sergeants.” We then passed on to others, who freely answered all our questions. They are all convalescent with the exception of one prisoner, who was shot in both legs. One leg has been amputated, and it is supposed the other will have to be, and that he will not be able to survive the operation. From here we proceeded to the armory, and were shown some copper balls taken in the late battles. We then visited Major Ringgold’s grave. It is enclosed with a wooden fence, the rails of which are filled with holes, so as to admit musket barrels. These form the palings, the bayonets serving as pickets. Two boards painted black serve for tombstones. The newly made graves of volunteers were scattered around, with no names to distinguish them. Thus we realize all their day-dreams of an unfading name. We then retraced our steps towards the quartermaster’s depot, stopping at[Pg 21] intervals to speak with the regulars, who were very courteous and patronizing, evidently feeling their superiority.

“At the outer edge of the entrenchments, we passed by a party of Mexicans. We could not but exclaim, ‘Are these the people we came to fight against?’ You can form no idea of their wretched appearance, without thinking of the most abject poverty and ignorance. They had brought hides to sell, on carts with wooden wheels, drawn by oxen with a straight stick lashed to the horns for a yoke. Having arrived at the quartermaster’s, we were shown some pack saddles, and camp equipage taken in the two battles. I never was more disappointed with the appearance of a place than I was with Point Isabel. The government houses are built principally like barns with canvas roofs. There are in the place only three or four old Spanish huts, with thatched roofs; the rest are tents and canvas covered booths. Capt. Bowles has been elected Colonel by about 100 of a majority. We start for the mouth of the Rio Grande to-morrow at daylight.”

Aug. 1.—As I stated in the foregoing letter, W. A. Bowles of Orange County is now our Colonel elect, Captains Sanderson and Reauseau being the opposing candidates. I shall here refrain from speaking of the present defeat, but I am well assured that Sanderson was honestly elected at New Albany; and yet losing one of the company returns, was enough to break the election, although the clerks were willing to swear that Sanderson had a majority! How we have been gulled and led about by a set of political demagogues, who, regardless of the fearful responsibility, have forced themselves into positions they possess no qualifications to fill, with a hope thereby to promote their future political aggrandizement. O! shame on such patriotism!—According to orders early this morning, we took up the line of march for the mouth of the Rio Grande, stopping only to prepare to wade the lagoon. Having arrived, we pitched our tents to await transportation.

19th.—By way of relating what has transpired in the last two weeks, I will copy a letter to two of my relatives, containing most that I would have journalized.

“I received your letter, and under no circumstances could it have been more acceptable. The company left the mouth of the Rio Grande on the 3d inst., except one of the lieutenants and myself,[Pg 22] who were sent up the day before with eight men, to guard the commissary stores. We arrived at this place, Camp Belknap, fourteen miles below Matamoros, in the night, and remained on duty in the rain and mud with no shelter for twenty-six hours. When the regiment arrived, we exchanged the duty of sentinels for that of pack horses. We carried our baggage and camp equipage, nearly a mile through a swamp, into the chaparel situated on a slight elevation or ridge. It is universally admitted that a chaparel cannot be described. I shall therefore attempt it no further than to give some of the outlines of its character.

“At a short distance it is indeed beautiful, resembling a well cultivated young orchard. Upon a near approach we find the largest trees do not exceed in size the peach or plum tree. These are very crooked and ill-shaped, with pinnate leaves somewhat resembling the locust. They are called musquite trees, and are scattered about at irregular distances. The intervals are filled up with a kind of barren-looking under-growth, which meets the branches of the former. Prongs of this bush, with sharp steel-colored thorns, shoot out in all directions, commencing just above the surface of the ground. The rest of the chaparel is composed of all kinds of weeds, thickly interwoven with briars, and interspersed with large plats of prickly pear and other varieties of the cactus family.

“I am conscious I have not done this subject justice. My powers of description are inadequate, and in order to have a full and clear conception of a chaparel, you must see and feel it too. Two days occupied in clearing it away, preparing for an encampment, will give any one a clear idea of its character. The expression so common with us,

All bushes have thorns

All insects have horns,

is almost true without exception. Even the frogs and grasshoppers are in possession of the last mentioned appendages.

“Our encampment is beautifully situated upon a grassy ridge, bounded in front by the Rio Grande, opposite Barita, and in the rear by a vast plain bedecked with little salt lakes. Now if you think this a romantic spot, or that there is poetry connected with our situation, you need only imagine us trudging through a swamp, lugging our mouldy crackers and fat bacon, (for we are truly living on the fat of the land,) to become convinced that this is not a visionary abode, but stern reality. I have yet encountered but little[Pg 23] else than sloughs, thorns, and the ‘rains and storms of heaven,’ and consequently have not appreciated the clear nights and bright skies of the ‘sunny South.’ At present we have finer weather, and it is said the rainy season is nearly over.

“I hope that by speaking freely of things as they are, I am not conveying the idea that I am discontented. Notwithstanding the attractions of home, and the greatness of the contrast when compared with these scenes, I never yet have regretted the step I have taken. We sometimes think it hard to bear with the ignorance and inattention of our field officers. The badly selected ground and our frequent want of full rations may possibly not be attributable to their ignorance and neglect, but they are certainly the ones to whom we look for redress. Other regiments around us better officered, fare very differently. I visited another corps the other day, and to my surprise found that they had for some time been drawing an excellent article of flour, good pickles, and molasses. This was the first time I knew that such things could be obtained, except from the sutlers, who charged seventy-five cents per quart for the last-mentioned article.

“The more I see of our boys the stronger is my impression that a better selection could not have been made. Our messmates are all well chosen, and had we no other difficulties than those incident to a soldier’s life, a happier set of fellows could not be found. The plans we form to enliven, not only succeed with ourselves, but attract other companies. Our quarters are frequently sought by them, to listen to our music, and look upon our merry moonlight dances.

“I am sometimes struck with the patience and philosophy exercised, even while performing the humiliating drudgery of the camp. In my own case I do not know whether it is owing to my selection of companions or not, but I have never realized the exhaustion and fatigue a description of our manner of procuring water and provisions would indicate. I have just returned from one of these expeditions, and will here give you a faithful description of the schemes resorted to, in order to lighten our burdens. Another and myself set out with two iron camp-kettles swung upon a tent pole. Walking about half a mile up the ridge, we came to the crossing place—the narrowest place of the slough, which ebbs and flows with the tide. This is unfit to drink on account of possessing the essence of weeds, distilled by the combined action of water and[Pg 24] sun. In this clime he trifles not, but sends his rays down with earnestness and energy. Well, after struggling through the tangled weeds with water nearly to the waist, we in due time arrived at the bank of the river, dipped up our water and sat down to rest. We found but little inconvenience in getting water from the stream, as it was filled to the top of its banks. The country here of late has been almost inundated. The oldest residents say such a flood has not been before for thirty years. If there is fatigue in going with empty buckets, you may readily conceive what is the effect of filled ones returning. The pole was kept continually twisting by the swinging motion of the kettles, it being impossible to keep them steady on account of the irregularities of the road. The difficulties of the journey were greatly augmented by the depth and tenacity of the mud, which kept us plunging about, and to our great consternation, causing us to spill the precious liquid.

“From this description you may think we had a cheerless trip. It was not so. All was characterized by good humor. We started out crying the lead, ‘a quarter less twain,’ until we exhausted the vein; then turning military, the command was given, ‘guide right, cover your file leader, left, left, left,’ &c. The novelty of the scenery and genial influences of the sun,—for I know of no other cause,—gradually excited our minds as we proceeded through the quiet wave, and inspired us to more noble and exalted demonstrations. Glory became the subject of our song. Touching quotations from the poets, and inflamed, impressive recitations, from ardent, patriotic orators and statesmen, were resorted to, expressive of the high aspirations with which we set out upon this glorious campaign. We then in lower tones spoke of the realization of these day-dreams. With feelings thus awakened we continued our wade. As we approached the land, whether it was owing to a sensitive feeling upon the shoulders, a general physical debility, the interesting associations, or the lulling murmur of the ripples in our wake, I pretend not to say; at any rate ‘a change came over the spirit of our dreams.’ Our minds reverted to the pleasing recollections of home. The departed shades of good dinners, and clear, cool refreshing drinks, rose before us, seducing our appetites from coarser fare. Thus ended our trip, which, from our own reflections, and the ludicrous contrasts of the present with the past, wound up with the heartiest merriment. Safely landed, we drained our boots and proceeded to tent No. 1.,[Pg 25] where the water was received by our thirsty messmates with countenances expressive of joy and satisfaction.

“The day before yesterday we lost one of our comrades, John Lewis, who died from the effects of measles. Not one, to my knowledge, taken down here with this disease has ever recovered. He was the second in size in the company, and possessed a powerful frame and a strong constitution. We gave him a soldier’s burial. We have obtained discharges for all our sick who are dangerously ill. There is but a small chance for recovery here. The disease may be partially overcome, but to regain strength, when but little reduced, is almost impossible. I don’t wonder that our hospitals are full when I think of that dreadful slough. For my own part I was never blessed with better health. Ever since we landed at Brazos, I have not in a single instance failed to report myself fit for duty, at roll call every morning. None have escaped better. The boys say I look so much like a Mexican in complexion, you would hardly recognize me. I cannot say much about my face, as I seldom get a sight of it, but my hands look very much the color of a new saddle. You would be surprised to see the bronzing effect of the sun upon our finger nails. This climate suits my constitution admirably, you therefore need give yourselves no uneasiness about my health.

“I do think I never had anything diffuse joy more suddenly through my heart, than did the arrival of your letter. I had just returned from wading the slough, loaded with provisions, as the company was going out on four o’clock drill. I was wet to the waist, and worn out by heat and over exercise. I perceived one of the lieutenants beckoning to me with a paper in his hand. As soon as he attracted my attention, he threw it on the ground, and hastened to join the company, which was marching to the parade ground. I seized it, and without changing my clothes read it over, and over again. It was soon spread among my friends, that I had received a letter, and congratulations from all were showered upon me. I read the expression, ‘Home; that word is dearer to you than ever,’ which met with a hearty response.

“The camp is continually agitated by rumors brought in by our scouting parties. The other day the regiment was ordered out, our effective force computed, and ammunition distributed, on account of one of these reports.

“You say you often wonder what I am doing. I will give you[Pg 26] our daily order of exercises. We are aroused at daylight by the reveille, and have a company or squad drill for two hours; after which eight men and a sergeant, or corporal, are detailed for guard. Company drill again at four o’clock and regimental at five. The intervals are filled up in getting wood, water and provisions, cooking and washing. Hunting parties go out sometimes and kill fowls, cattle, wolves and snakes. One day last week mess No. 14 served up for dinner a rattlesnake seven feet long. There are many things I should like to write, but having already spun this letter to an outlandish length, I conclude by thanking you for the attention and consolation you have given my dear mother. The affectionate regards of my brothers greatly encourage me. I am writing this lying on the ground, with my paper on my blanket, and with noise and confusion around.”

31st.—If our spirits are depressed, and loneliness and ennui pervade our feelings, when in good health, how much greater must be the discontent and gloom that weigh upon us when sick? Nothing could be more unenviable than my situation for the last two days. Last Thursday we moved our encampment about a mile further down the river, below the slough, upon the ground formerly occupied by the 2d regiment from Kentucky. The heat, rain, violent exertions and other causes combined, have brought upon me the prevailing disease of the season. I have suffered from accompanying headaches and fever. My condition has been much ameliorated by the kind attentions of officers and men. These examples of generosity are teaching me gratitude, but I place myself under obligation as little as possible.

If any one should wish to fully appreciate home with its endearing associations, let him imagine himself a sick soldier, with his body protected from the ground only by the thickness of his blanket, a coat or knapsack for a pillow, and the hot scorching sun beating through his crowded tent. And in the intervals of a burning fever, should his aching bones find repose in sleep, and in dreams

“Friends and objects loved

Before the mind appear,”

yet how fleeting are all earthly joys! The company on the right must be drilled. He dreams again. He meets in fond embrace the object of his purest affections, and is about to snatch a warm kiss[Pg 27] of welcome. That detested drum. Complain not. The sentinels must be relieved. I can write no more now. My head grows dizzy.

September 2d.—Last night the whole encampment was thrown into the most intense excitement, by a row which broke out between two companies of Georgia troops, who were embarking on the steamer Corvette for Camargo. The combatants were principally Irish, and fought with their characteristic determination. Although we were some distance from the river, we could hear distinctly the blows, and demoniacal yells of the rioters, which were truly appalling. The conflict continued for two hours, during which several were killed, and wounded, and quite a number terribly bruised, and others were knocked overboard and perhaps drowned. Colonel Baker, of the 4th Illinois regiment, marched on board with twelve men, and demanded peace. He was himself attacked by four men with bayonets, which he warded off with his scabbard, at the same time defending himself with his sword, from the attack of the Irish captain, and succeeded in disabling him, by thrusting his sword into his mouth, and cutting open the whole side of his cheek. A savage yell was immediately heard from the mob, and the report of a pistol, which was aimed at the brave colonel’s head. He fell badly wounded, the ball entering the back of his neck, and coming out of his mouth. Then came the cry, “Help, your colonel is shot,—they have killed Colonel Baker.” This was too much, and we made a simultaneous rush for our arms. Colonel Bowles ordered out five companies, the Greys among the number,—and in five minutes we had a line formed around the boat, and the riot quelled, before the Illinois regiment had arrived. The exposure of last night has quite laid me up to-day, although the captain of the guard called me from the ranks, and sent me to my quarters long before morning.

This has been a solemn day. We had two burials, and it is thought Colonel Baker will not recover. The whole day has been occupied in the court martial, which has resulted in sending the officers engaged in the riot, under arrest, to General Taylor, who is now at Camargo.

7th.—I am as well as ever again, and on duty. The regiment has just been mustered by Captain Churchill, for two months’ pay.[Pg 28] I have been gloomy and low-spirited all day. When I reflect upon my situation here in contrast with that at home, I can hardly realize that I am the same person. Everything appears like a dream, and I almost believe I am acting a part in which my own character is not represented. I am thrown among the temptations of camp, but do not think the effect will be demoralizing, or its impressions lasting. The more I see of vice and dissipation, the firmer I believe a moral and virtuous life constitutes the only sure guarantee of happiness. If permitted to return home, I shall better appreciate its blessings, be a better friend, a kinder brother and a more dutiful son. The more I know of the world, the higher value I set upon friends. Oh! how sweet to enjoy their society, and feel the capacities of the affections filled with congenial objects! Here I have nothing to love, no one who knows my heart, or understands my feelings. When I recall the impressions of mind under which I volunteered, I have a presentiment that an unhappy fate awaits me. I doubt whether a warm heart or a flowing soul is a source of more pleasure than pain to its possessor. * * * *

14th.—Two others and myself have just returned from a visit to Matamoros. Three or four days since we left the camp in company with several of the officers, on board the steamer Whiteville. They were going to draw pay. The captain of the boat was quite disconcerted to see so many of us (nearly twenty in all), coming on board. Having got under way he still insisted he could not accommodate us; that he had no right to stop for us, and that our orders from the quartermaster were nothing to him. After much debate in relation to provisions, starvation, &c., we settled down, and made up our minds for the worst, which was bad enough, to say the least. The boat lay-to at night on account of fog and the serpentine windings of the river. We stopped twice to wood on the way. The ranchos along the banks are principally owned by the rich, who live in the cities. General Arista’s crossing was the first place we stopped. There are here about half a dozen thatched huts, and about twenty “peons” employed in cutting wood, and hauling it on carts with wooden wheels. Quite a number of us went ashore and distributed ourselves among them. I went to the farthest hut, where I was greatly amused by the little urchins. They were running around the yard perfectly naked, notwithstanding the rain was pouring down in torrents. I approached the house which contained[Pg 29] one man, two women and three or four children. They all arose, and made the kindest demonstrations for me to enter. I declined, at the same time pointing to my muddy feet. They signified “never mind the mud,” and I walked in and seated myself upon a bench. One of the females furnished me with a cushion to sit upon, covered with cloth of their own weaving, which was fringed and ornamented with the brightest and most showy of colors. We could understand each other very well upon some subjects, such as the various articles of clothing, and the prices of the different materials. Everything in the room was of the roughest construction. The fire was placed at one end of the room upon a floor, which was of the most primitive order. An aperture in the roof served for a chimney, which but partially performed the agency. They were destitute of chairs and bedsteads. Hides spread upon the ground constituted their beds, an arrangement admirably adapted to prevent injury upon the heads of children, caused by falling during the dreamy hours of sleep. I was greatly pleased with the two women, and with one especially. She appeared to belong to a higher station. She was apparently about twenty-one, and looked very differently from any of the sex I had yet seen in that region. Her forehead was high and intellectual, her countenance was animated and intelligent. In her ears were large golden pendants, which contrasted strangely with the rude furniture around. Her beautifully delicate hand did honor to the glittering jewels encircling her tapering fingers, which were gracefully entwining the hair of her companion seated by her side. Perhaps my preference for one was induced by the approving glances from her “large, dark, eloquent eyes.” She had smoothed for me the cushion, and flattered me with her looks, and I being in a frame of mind rather susceptible to kind attentions, my vanity was very naturally somewhat excited. They were both attired in the simplest manner. A white chemise, and skirt girded around the waist with a yellow silk sash comprised the whole arrangement. Their small beautiful feet were not cramped in stockings or shoes, or their ankles hid with a skirt too long. Their bosoms were not compressed in stays, or mantled in cashmeres, but heaved freely under the healthful influences of the genial sun and balmy air of the sunny south. I approached the mat where they were sitting, and took the hand of a little girl, and touching the shoulders of my favorite, I pointed to the child and asked if it was hers. She shook her head, and looked intelligibly towards her companion. I then[Pg 30] took up the child in my arms and pointed to the “States,” as if I would take it home with me. They both snatched the child with great fondness, exclaiming “no, no, no,” to the infinite amusement of the men who came around me, making every demonstration of gratification and good will. At this interesting crisis the steamboat bell summoned me, and by running at full speed I arrived just in time, while one of the party less fortunate was left behind. He was greatly frightened, and plead earnestly, but his supplications were in vain. The captain said he could walk across the country, and get to Matamoros before we would. I would almost willingly have exchanged situations with him.

We at length arrived at Matamoros, having been in sight of the town for five hours before we landed. The river is so crooked that there are landings on different sides of the city. We registered our names at the Exchange Hotel. This is a two story brick building with a flat roof, and an open court in the centre. It was formerly the Mexican custom house. Our sleeping room was the one through which two cannon balls had passed, during the bombardment from Fort Brown. The next morning we rose early and visited the market. The building is about twenty-five feet high, supported by columns and arches. The whole interior is divided into stalls, where can be bought meats of all kinds. The outside is reserved for vegetables and varieties, sold from mats spread upon the ground, by women with half-clothed figures, and disheveled hair, presenting an appearance uncouth and repulsive. Bread, milk, pies and hot coffee are sold in large quantities.

I was surprised to find so many Mexicans still residing in the city. And was still more surprised to find the alcalde and police officers performing their respective duties, and all the municipal laws enforced as formerly. The alcalde, however, receives instruction from Colonel Clark.

The dress most common for the women I have already described; I will, however, mention that they never wear bonnets, but throw a scarf ingeniously over the head and shoulders. The young men dress with much taste and neatness, and most of them possess fine figures. They generally appear in white, and instead of suspenders they wear around the waist sashes of various colors. The bottoms of their pants are of enormous width. Some, more showy than the rest, wear blue over the white, with the outer seam left open to the hips, and buttons down the side. The hat, which is made of straw[Pg 31] or wool, and often covered with oil-cloth, has its peculiarities. On each side and about three inches from the top, are fixed little silver knobs in oval plates. The bands are often made of gold or silver. My thoughts and feelings while passing through the streets, were in keeping with the novelty of my situation. Suddenly thrown into a foreign city, where everything presented an appearance so dissimilar to anything I had ever seen, I was constantly surprised into expressions of wonder and curiosity. The side walks are so narrow but two persons can walk abreast. The houses on the principal streets are built generally of brick, with flat roofs, brick floors in the first story, and open court yards in the centre. Those in the less frequented parts of the city, are made of slabs and stakes driven into the ground, the intervals filled with mud and straw, and thatched with palmito.

One of the most distinguishing characteristics of this people is their insatiate thirst for gaming. It amounts almost to monomania. Play seems to be the sole occupation of a large portion in this place. Crowds of both sexes may be seen at almost any time in the streets, and on the banks of the river, betting on their universally favorite game “monte.” The hotels, restaurants and coffee-houses are infested with gamblers from all nations. Those boarding at the Exchange follow their respective games, with all the dignity that characterizes the professor of law or medicine. Many of them are very showy in their appearance, courteous in their manner, and agreeable in their intercourse. To the volunteers, they are attentive and obliging, always ready to give them any information or advice, and ever ready to rid them of any extra dimes they may wish to hazard upon their games. It would doubtless surprise any of our good merchants at home, to witness the unceremonious rancheros entering their stores, leading in their favorite mustangs after them,—a general practice here. But it is time I should close this prosy description. It would be an endless task, should I attempt to relate all I saw and heard in the church, in the hospitals, and especially the never-to-be-forgotten incidents on the lower plaza, and at the fandango.

Just before we unexpectedly embarked for the camp, our attention was attracted by music, and a crowd, following a company of rope dancers. We were informed that they came in every Sunday afternoon, and performed at three o’clock. The party consisted of three men and one woman on horseback. They were gaudily[Pg 32] dressed, very much after the manner of our circus riders, but, if possible, more grotesque and showy. The music consisted of a clarinet, a drum and a kind of ophicleide painted green and red. The pompous cavalcade, supported by the motley crew of men, women and children, making every gesticulation of delight, presented truly a rich and ludicrous scene. About this time the steamer Corvette rounded to with a load of sick volunteers from Camargo, for the general hospital, and as we expected to leave immediately, we hastened on board.

I never in my life regretted so much to leave any place after so short an acquaintance. I was just becoming familiar with the city, and the next night promised much. That by the way. I went on board without a murmur, and was soon on my way to the camp.

20th.—This day has opened upon me fraught with new cares and responsibilities. This is my twenty-first birth-day. My country can now fairly claim my influence in sustaining her laws, and supporting her institutions. When an American youth enters upon the stage of political life, he should endeavor fully to comprehend the genius of its government, and the high and glorious privileges it imparts. His freedom of thought and right of suffrage place him far above, in point of privilege, any other people, and secure to him blessings not enjoyed by any other nation under heaven. In view of the inestimable rights he enjoys, how great are his obligations! How carefully should he endeavor to avoid party influences; and remain firm in noble principles, in spite of the deluding sophistry of heartless demagogues. As he approaches the ballot-box, that sacred guarantee of liberty when unabused, let him pause and reflect whether he is acting from impulse or the dictates of reason. I am now twenty-one! We all look forward with interest to the period! We expect, and we anticipate, and how often, during the flow of buoyant thought, we map out the way to future greatness. My feelings are so fluctuating, my anticipations so frequently unrealized, that no result can be very unexpected. From this candid and free expression of my feelings, I do not wish to convey the idea that I am disposed to find fault with the world, or with the organization of society, but only to indicate more clearly the constitution of my mind with native sources of unhappiness.

In looking back over a few years in which I have mingled some in society, I cannot say I have derived no pleasures from the past,[Pg 33] that I have seen no bright spots, or enjoyed no valued objects. It would be base ingratitude were I to disclaim participation in some delightful scenes where sympathy and affection warmed kindred hearts. Was this more than balanced by painful reaction?

The frequent brooding upon saddening subjects, pride, and, I may add, a sprinkling of patriotism, will, to some extent, account for this day finding me a soldier upon the borders of Mexico. It is time I should leave this subject. I drop it at once to recount some of the events of the day.

Yesterday we were visited by a strong north-wester, so common to the season in this latitude. It blew so hard that the water from the Gulf was driven up into the sloughs, causing a swelling from the little salt lakes of which I have before spoken; but to-day we have a clear sky and a calm breeze. After breakfast this morning, I went to the sutlers, and bought a large box of sardines and some claret, as a little treat for the mess. Our captain and lieutenants were invited to partake, and toasting my birth-day, they all wished me success. I spent the night until tattoo, in writing these random reflections, and in thinking what a contrast the associations of to-day will present, when compared with three preceding anniversaries of my birth-day.

October 5th.—For the last two weeks nothing has transpired worthy of note. The time drags heavily when waiting for orders.—Col. Lane’s regiment has moved up to Palo Alto, seven miles from Matamoros. General Lane still drills our regiment, as our colonels are both sick, and one gone home. Yesterday I wrote a letter, and will copy it in part.

“* * * * * It is Sunday evening, and just about the time you are returning from church in the afternoon. I fancy I can see the friends convened in your front room. I often think of your parlor. At this time what a different scene our camp presents from that of the drawing-room! Instead of handling gloves, fans, or parasols, our boys are engaged in brightening their arms and equipments, to surprise the regiment this evening on dress parade. I am sitting in tent No. 1, and writing this epistle upon a box that some of the boys have picked up at the commissary’s. While speaking of the mess I will pronounce a short eulogium. It is the only one, with perhaps one exception, that has undergone no changes since we left home. We have had no difficulties, but have[Pg 34] lived together in uninterrupted harmony. We now number six, one of our mess having been discharged. What a place this for the study of human nature! Points of character that at home lie concealed from every one, are here developing every day, and consequently much change of opinion in relation to character. Even one’s own self changes views respecting one’s self, in regard to the natural disposition, motives, and impulses of action. The more I see of a soldier’s life, the stronger is my conviction that there are worse evils to be feared than those of the battle field. A retrograde in morals or a total loss of moral principle, is incalculably worse. Take young men, who, from their position in society at home, are excluded from the haunts of strong temptations and the greater vices, and for the most part you will find them moral from habit, rather than fixed principles, and a clear discrimination between right and wrong. O! how many such will be wrecked and ruined in this campaign!

“I am daily realizing the force of that old adage, ‘we know not what we can do until we try.’ If any one had told me only a few months ago, that I could with impunity, sleep upon the ground in the open air, and rise at reveille in the morning, and drill two hours before breakfast, I should certainly have been at a loss to know of what kind of materials he thought I was made. Yet these I do almost every day, and so accustomed am I to a soldier’s couch, I seldom think of a softer bed. Then, there is poetry in reposing under the direct gaze of the moon and stars, which, like guardian angels, superintend, while the watchful sentinel guards around. Apropos: we do have some of the finest nights you ever witnessed. The moonlight is so clear and bright, we easily see to read by it. And then what a range for the imagination. How plainly do happy meetings, delightful visions of love and sympathy, rise before us. Under such pleasing emotions we sink into the most refreshing slumbers, which are only disturbed by the musical mosquitoes or industrious ants. I close this epistle. The drum calls to parade.”

31st.—The only apology I offer for such a distance between dates, is the absence of anything worthy of relation. I have occupied a part of the interim in writing letters, and as they contain the little of incident transpiring, I will copy another in part.

“As a good opportunity presents itself to send you a few lines, I will avail myself of it, although it is very disagreeable to write with[Pg 35] a strong northerly sweeping over, blowing sand and dirt in the eyes, and covering the paper. I received your last letter, and I assure you it gave me great pleasure to hear you were well, and partially resigned to our separation. I waited for it so long, I had become used to disappointment, and thought myself partially hardened and indifferent, but it has awakened anew all my anxieties. How lonely and melancholy it makes me feel to see others around reading epistles from their friends, while I am apparently forgotten and uncared for. Indeed, these reflections are sources of much unhappiness. Do not think from these expressions, that our condition is worse than previously. It is greatly improved since the many unfavorable accounts you have heard from us. There is not now one among us confined to his tent, and everything goes on as well as a soldier could expect. My brothers can form no idea of the encouragement and gratification they afforded me by their assurances of interest and regard. I can conceive of no incentive to action greater than to gain their affection and approbation. Assure them of my kind remembrances. I feel this separation will only tend to bind us closer together, if we are ever permitted to meet again.

“As the armistice has not yet expired, I cannot with certainty inform you of our future movements. If the war continues, we expect to move towards Tampico, where we expect active service, a glorious end or a wreath of laurels. General Patterson deems it no mark of disrespect to the Indiana troops, that they have not been pushed forward, nor will it affect our reputation. Our hospital has recently been greatly enlarged and improved. Our stock of medicines is very low, but fortunately the camp was never in a healthier condition. Cease your care for me and bestow your sympathy upon a needier object. The sick soldier with a hard bed and burning fever, has a stronger claim upon you. Forget him not.

“I commenced this letter intending to send it immediately, but shall not be able to do so for a week or two.”

10th.—I transcribe here a fragment of a letter to my sister “——. I do think you have used me shamefully, by not noticing one of my letters, and I have a great mind to fill this whole sheet with scoldings. I left home as you know, with but few associates. I have no friends of my own age with you, that I have any claims upon, or from whom I have a right to expect any favors. But from you I expected much, or at least I felt assured you would not forget[Pg 36] me. How much I have been disappointed, you yourself can judge. Your inattention becomes more unpardonable, when I think of the many subjects of interest you have to write about. If you would just give a list of the friends who have called upon you, within the last week, or fill a page with the innocent sayings of the little ones, it would be hailed by me as a God-send in this dreary place. I am beginning to feel quite like an old soldier, and ‘forward, march, guide left,’ and other phrases of the drill are becoming as familiar as if I had spent years in the service. We have had quite an excitement in relation to moving, for the last two weeks. General Lane has received orders to hold this regiment ready to march at an hour’s notice. Ever since he has drilled it twice a day. The Tampico fever and rage for Monterey have abated, but still the general keeps up his two drills a day. The paymaster was here last week, and paid off all save three companies,—ours one of them. The money gave out. The health of the company is better than ever, and we do have some of the greatest jollifications you ever heard of. We get a couple of violins, and do up dancing to their music à la Mexicana. You would deem it a rich treat to hear the promptings, and attempts at Spanish, which some of the boys have picked up in the neighborhood, at the various fandangos. We sometimes have half the regiment about our quarters. The captain’s marque, like his shop door at home, is the emporium of anecdote and humor.

“15th.—Lieutenant Cayce has just arrived from among you, and has enriched us all. How shall I express my gratitude, for the kind favors you have shown me? The shirts from my dear mother came just in time. And although the expression of Falstaff,—‘I have but a shirt and half to all my company; and the half shirt is two napkins tacked together,’ was not true of us generally, yet I assure you my under ‘tunic’ answered mighty well to the half shirt. Your letter, and those of other friends are thankfully received. This has been a happy day to us all, notwithstanding the north-wester. I now take a hasty leave. The bearer waits for this.”

21st.—For the last two days we have all been busily engaged in preparing for, and in celebrating the fourth anniversary of the Spencer Greys, which came off yesterday in fine style. Our arms and equipments were all polished and whitened, in the best manner[Pg 37] our limited conveniences would allow. Our fatigue dresses were not so showy as our handsome uniforms at home, yet we made an imposing appearance, and attracted much attention, while performing some maneuvers of the fancy drill, upon our parade ground. One of the paymasters said it was the finest display he had seen on the Rio Grande. I am told that our general, in a burst of admiration, said, “I would rather command a regiment of such boys than be the president.” In fact we did ourselves great credit both in the field, and target firing. Above all the rest our beautiful flag was universally admired.

It was a fine day, and everything appeared to good advantage. The sun once more shone forth with all his refulgence, which contrasted happily with the cold and dreary weather of the three or four previous days, during which a strong norther was sweeping over us, blowing down tents and covering everything with sand. But our birth-day anniversary was ushered in with an unclouded sky, and a complete change in the whole face of nature. The whole day proved an auspicious one, as the paymaster arrived and forked over our seven dollars a month. At night music and dancing were the order of exercises until tattoo, after which I took the arm of a messmate and strolled out upon the bank of the river, where we called up to our minds images of the past, spoke of home, and drew many interesting contrasts. The pleasures of memory, how varied they are! How inestimable are the faculties by which we can enjoy again, former pleasures, and happy unions of the past! I sometimes think that pleasures retrospective are purer than those of anticipation or realization. “How grand is the power of thought! My God! how great it is.” These reflections and our mutual interchanges of sentiment were at length interrupted by the sound of a guitar, which emanated from the sutler’s tent, to which we at once proceeded, and found quite a number of officers, listening to the laudable performances of our musical trio. We remained by invitation, until the party broke up, then returned to our quarters.

“23d.—Dear M —— I have just returned from a visit to Point Isabel after letters. Most of the boys were paid for their pains, except myself. It is an anomaly to me that others around me are continually receiving epistles from their friends, while I am generally doomed to disappointment. The party consisted of five. After walking sixteen miles, we arrived at Brazos Santiago, where[Pg 38] we were struck with the change everything presented. It appeared more like the levee at New Orleans, than the desert island on which we first encamped. The government has about one hundred and fifty teamsters and laborers employed, and whole acres are covered with baggage wagons and army stores. The harbor is filled with hundreds of vessels. Having regaled ourselves with a dish of oysters and clams, we took a boat and sailed to the point. We registered our names at the “Palo Alto House,”—repaired to the post office, and performed various errands for the boys. The next morning we witnessed the thrilling spectacle of the disinterment of the remains of Major Ringgold, for the Baltimore committee. The coffin was escorted to the quartermaster’s depot, by a company of regulars. Others formed a procession in the rear, and all marched to the tune of “Adeste Fideles,” accompanied by the roaring of one eighteen pounder. Having arrived at the destined place, the body was removed to a leaden coffin. It was so decayed we could form no idea of its form or features. After dinner we returned to the Brazos, and put up at the Greenwood Hotel. During the night there came up a tremendous storm, which swept over the island driving everything before it. It was quite amusing to see the barrels and hats, bounding before the gale. Even part of an old steamboat chimney was started, and rolled before the wind, faster than a horse could gallop, and was thus driven as far as the eye could see on the other side into the gulf. A bet was made upon the comparative speed of the barrel, hat and chimney—the hat won. Having finished our suppers, we repaired to the theatre. The Young Widow and Irish Tutor, composed the exercises of the evening, interspersed with songs and dances. Two or three of the characters were tolerably well sustained, and one of the mess remarked, ‘It is as good a theatre as I want to go to.’ The storm continued during the performances with redoubled fury, and the tide coming up between us and our lodgings, we were forced to wade it against wind and sand, which lashed our faces unmercifully. The next morning we started for the camp, stopping by the way to pick up shells, which I will send you the first opportunity. The Tampico fever rages higher than ever, and our general is of the impression, we will not be here six days hence. * * * * * Messes No. 1 and 13 have this day united into one. We now think we are the greatest mess alive. Every one possesses some peculiarity of taste and disposition,[Pg 39] that affords fun for the rest. Every meal is attended with the life and jollity of a public dinner.” * * * *

“22d.—Dear Mother. The letter and clothing you sent me were gratefully received. You can form some idea of my health, when I tell you the shirts would not button at the neck by two inches, nor at the wrist without an effort. In the pants the boys say I look like a ‘stuffed paddy.’ Nevertheless they all answer the purpose.

This has been quite an eventful day. In consideration of having no extra dinner on the day of our celebration, and this being the birthday of two of our boys, the combined efforts of messes 1 and 13, were brought to bear upon the preparation of a sumptuous dinner for the company. Guests were invited, among whom were many officers of the brigade and regiment. Everything was got up in a style truly rich and rare. Cooking was done in a manner unsurpassable. Roast beef, fish, potatoes, peach pies and pound cake without eggs, constituted the principal dishes. Cigars and claret, were the accompaniments. Managers, cooks and waiters, all performed in their happiest way, in their appropriate departments, and our guests congratulated us upon the entire success of our efforts.” * * *

December 5th.—We all thought yesterday, that last night would close our stay in camp Belknap, as we had received orders to embark on the first boat, for Camargo, and thence to Monterey. The joyous excitement this news diffused among us, surpasses any description I can give. In our company the whole night was spent in music and dancing. Our musicians acquitted themselves ably. Our captain and others joined in our merriment. I was on duty as corporal of the police, and as the officer of the day only ordered me to suppress all riots, and see that the lights were put out at tattoo, I did not think dancing included, so I joined in the festivities with an ardor that has rendered me to-day almost unable to walk, and my head aches as if it would split. “Those who dance must pay the fiddler.” We have just removed to the river, where we will await conveyance.

7th.—Night before last seven companies of the regiment embarked for Camargo, leaving the two rifle companies and Spencer Greys for the next boat. We are detained in consequence of the[Pg 40] captain refusing to go on the steamer Enterprise, as it is too small to be safe for three companies. So the Lanesville Legion took our place, it being a smaller company. We expected to start next morning, but have been disappointed.

Last night we were thrown into great excitement by the alarm of an attack from the enemy. Just before dark the general and others thought they heard sounds of a bugle, in the chaparel on the Mexican side of the river, supposing them to proceed from the enemy. In consideration of our exposed position,—there being only one hundred and fifty of us, with but little ammunition, it was thought prudent to station a picket around the camp. The three companies were ordered out, and four cartridges apiece distributed, then marched up to be reviewed by the general. He told us what he had heard, and other causes which made our position a dangerous one. He urged the necessity of watchfulness, saying that we would never have so good an opportunity of showing what we were made of. Many other things he said, calculated to excite our attention, then dismissed us charging us to lay near our arms, and not be taken by surprise. We returned to our tents, and arranged everything, and lying as directed upon our arms, we made up our minds to do our best, if we were disturbed before morning. About two hours after midnight, we were suddenly aroused by a discharge of musketry from our outpost, and the cry, “to arms, to arms.” In ten minutes the whole three companies were at the general’s quarters.

I think I know now the feeling one experiences while going into battle. My emotions this night I never shall forget. When first aroused I seized my musket and equipments, and rushed from the tent in the greatest excitement. The firing from the pickets, the universal rushing, hurry and confusion, the impatient cries of, “make haste, men; fall in,” etc., made me so nervous that doubtless for a few minutes, my words were unintelligible. After a short period of agitation everything was ready. As we were marching out to take our position, it seemed that this would be a wonderful night in my earthly career, and my fate was to be decided by my success in the coming conflict. I said within, be calm and do your duty. I aroused all my energy and decision of character. I then moved with an unwavering step, and would have given all my possessions to come in contact with the foe. Our men never marched better, dressing to the guide as it was shifted, with as much calmness as when on ordinary drill.

[Pg 41]

Having formed our line in front of a dense chaparel, a party was sent out to reconnoitre. Here I had a presentiment that the enemy would not meet us; that this was not the night for our military laurels to be secured. Had we met the enemy in the field of battle; had we gained victory amidst adverse circumstances, how gratifying to ambitious desire that friends should read eloquent descriptions of our deeds of chivalry. Great was our anxiety while waiting for the return of the detachment.

At length the party came; they reported to the general; the general addressed us in complimentary terms, expressing his unlimited confidence in our fidelity and courage. He dismissed us saying our only enemies here, the wolves, had retired to the chaparel. We returned to our tents crest-fallen, very few having a disposition to joke or laugh over this evening’s adventure.

10th.—At last we have departed from camp Belknap. The place that a few months ago contained 8000 souls, is now without an inhabitant. I left this beautiful spot with mingled emotions of pain and pleasure. Here we had light duties, we had opportunities to hear from home, and other sources of comfort. On these accounts I confess I left camp Belknap with regret. But on the other hand it could be no longer said, they still remain away from active duties and scenes of glory. I thought of the upper camp and wonders in other lands. On these accounts I left our old encampment with feelings of delight.

We transported ourselves, our camps and equipments to the river bank; but how heavily many an hour passed away before the arrival of a steamboat. We several times laid in provisions and cooked them for the trip, and several times we eat up our provisions before we started on our trip. It is said man is a poor economist in domestic matters, and indeed our conduct on this occasion seemed to prove it.

Well, at last we are on board the steamboat Whiteville, the same upon which many of us went some time ago to Matamoros. Before its arrival the three captains drew lots for choice of quarters. Our captain was successful, and he selected the boiler deck. But the captain of the steamboat refused to let us occupy the place specified. His plea was “’Tis unsafe, the boat rolls so.” Accordingly all three companies were stowed away amidst the filth, noise and confusion of the engine room. O! ’tis revolting to the feelings of one[Pg 42] accustomed to the decency and luxuries of civilized life, to be herded together like cattle in some dirty little enclosure, and there treated with the hauteur and chilling neglect of the most abject slaves. How the hot blood mantles my cheek when I look at our situation. “The boat rolls so!” A fine excuse truly! Other boats of no greater strength carry troops upon the boiler deck; yet this hireling says, we “have no more right there than his firemen.” Behold the sacrifices of the soldier! He forfeits his self-respect, his sense of right and wrong, his liberty of speech, his freedom of action, and his rank in society. All this for the public good, and what is his reward? Why, one ration a day, and seven dollars a month, the cold indifference of the hireling citizen, and of the avaricious or ambitious officer, holding in his hand the regulations of the Army. How many such officers when at home, in newspaper articles or public orations, give vent to fires of eloquence and of patriotism. They would shed the last drop of blood for their dear country! but they seem mighty unwilling to shed the first drop, or why don’t they shed a little reflection for the comfort of the poor soldier, or why don’t they shed out some of their big salaries for the advantage of those who have left firesides and friends for their dear country?

So far as this government boat was concerned, it had this regulation: “No private shall enter the cabin, or be permitted to sit at the table,” the money or intrinsic worth of the soldier notwithstanding. Well, I have this consolation, that I have endeavored to show proper respect without truckling to office or power. In my intercourse and associations with officers, I have kept up appearances without blushing, at the inferiority of my living to theirs. As to the monthly pay of the volunteer, one of my messmates well expressed himself. “I hope Congress may not increase our pay to ten dollars, for I never can be paid with money for the wounds my pride has received.”