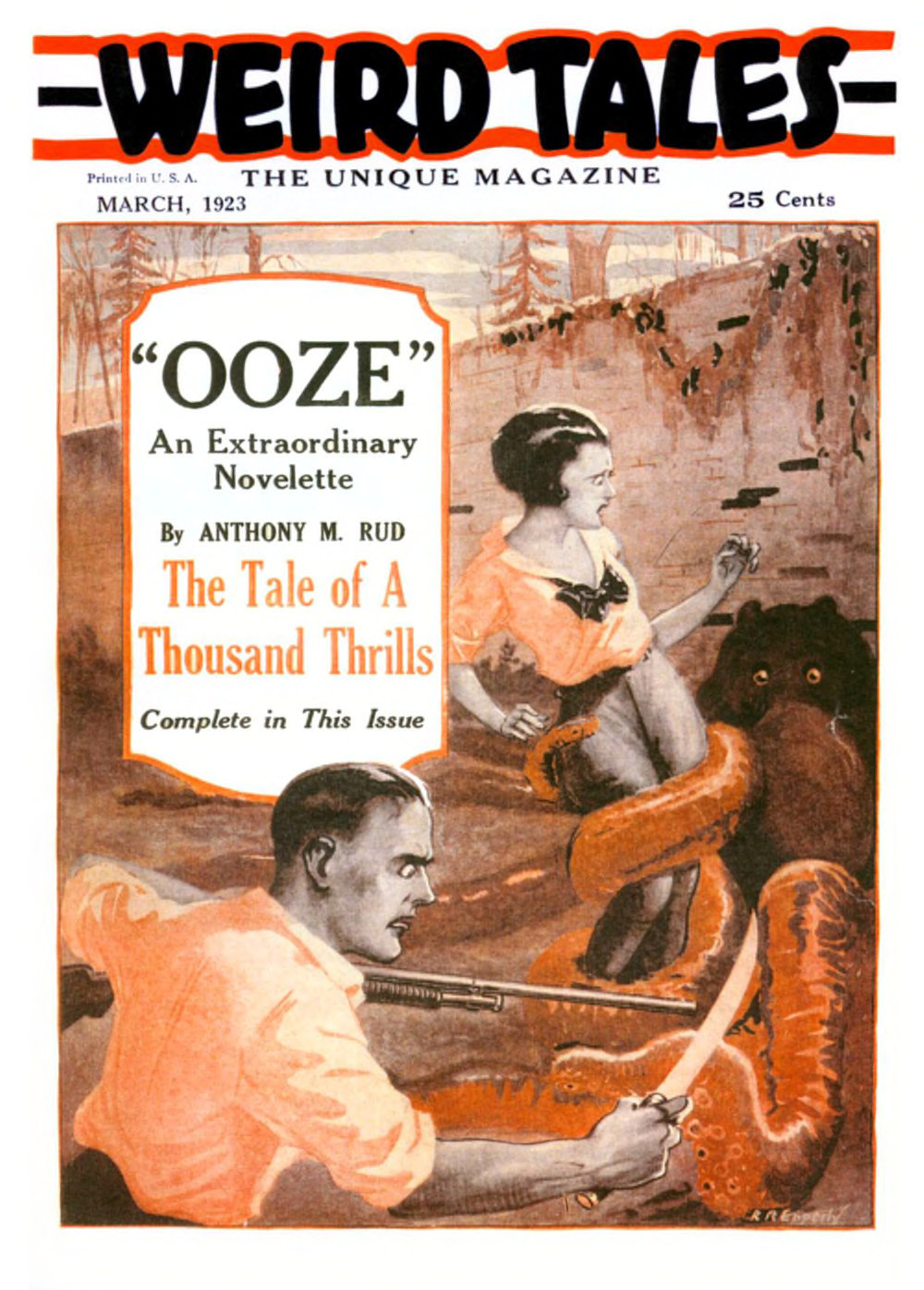

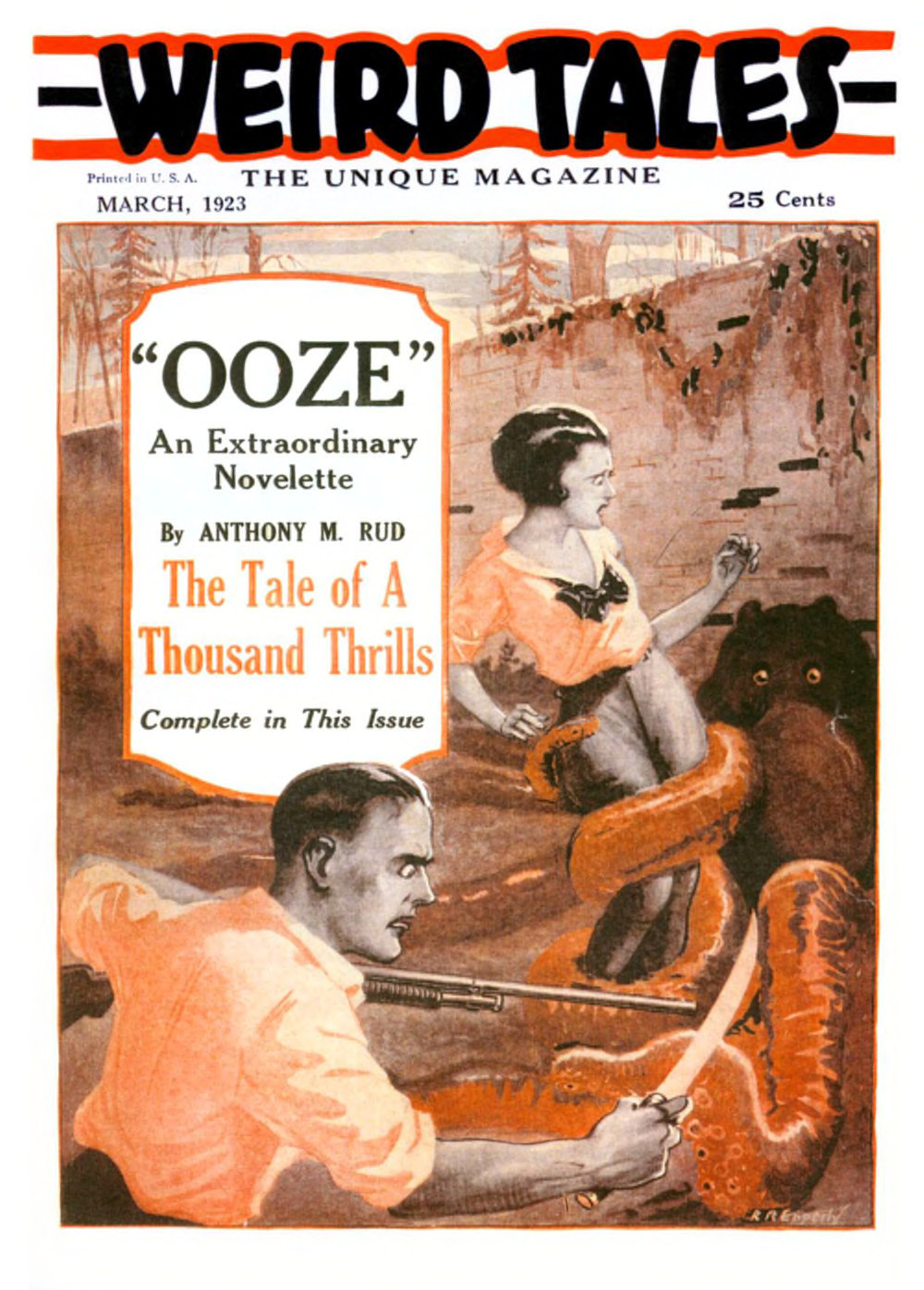

The Project Gutenberg eBook of Weird Tales, Volume 1, Number 1, March 1923, by Various

Title: Weird Tales, Volume 1, Number 1, March 1923

The unique magazine

Author: Various

Editor: Edwin Baird

Release Date: September 10, 2022 [eBook #68957]

Most recently updated: March 14, 2023 [eBook #68957]

Language: English

Produced by: Eric Schmidt, Wouter Franssen and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

[i]

[2]

Published monthly by the Rural Publishing Corporation, 934 North Clark Street, Chicago, Ill. Application made for entry at the postoffice at Chicago, Ill., as second class matter. Single copies, 25 cents: subscription, $3 a year in the United States, $3.50 in Canada. The publishers are not responsible for the loss of unsolicited manuscripts in transit, by fire, or otherwise, although every precaution is taken with such material. All manuscripts should be typewritten and must be accompanied by stamped and self-addressed envelopes. The contents of this magazine are fully protected by copyright, and publishers are cautioned against using the same, either wholly or in part.

| The Mystery of Black Jean | Julian Kilman | 41 |

| A story of blood-curdling realism, with a smashing surprise at the end. | ||

| The Grave | Orville R. Emerson | 47 |

| A soul-gripping story of terror. | ||

| Hark! The Rattle! | Joel Townsley Rogers | 53 |

| An uncommon tale that will cling to your memory for many a day. | ||

| The Ghost Guard | Bryan Irvine | 59 |

| A “spooky” tale with a grim background. | ||

| The Ghoul and the Corpse | G. A. Wells | 65 |

| An amazing yarn of weird adventure in the frozen North. | ||

| Fear | David R. Solomon | 73 |

| Showing how fear can drive a strong man to the verge of insanity. | ||

| The Place of Madness | Merlin Moore Taylor | 89 |

| What two hours in a prison “solitary” did to a man. | ||

| The Closing Hand | Farnsworth Wright | 98 |

| A brief story powerfully written. | ||

| The Unknown Beast | Howard Ellis Davis | 100 |

| An unusual tale of a terrifying monster. | ||

| The Basket | Herbert J. Mangham | 106 |

| A queer little story about San Francisco. | ||

| The Accusing Voice | Meredith Davis | 110 |

| The singular experience of Allen Defoe. | ||

| The Sequel | Walter Scott Story | 119 |

| A new conclusion to Edgar Allen Poe’s “Cask of Amontillado.” | ||

| [3]The Weaving Shadows | W. H. Holmes | 122 |

| Chet Burke’s strange adventures in a haunted house. | ||

| Nimba, the Cave Girl | R. T. M. Scott | 131 |

| An odd, fantastic little story of the Stone Age. | ||

| The Young Man Who Wanted to Die | ? ? ? | 135 |

| An anonymous author submits a startling answer to the question, “What comes after death?” | ||

| The Scarlet Night | William Sanford | 140 |

| A tale with an eerie thrill. | ||

| The Extraordinary Experiment of Dr. Calgroni | Joseph Faus and James Bennett Wooding | 143 |

| An eccentric doctor creates a frightful living thing. | ||

| The Return of Paul Slavsky | Capt. George Warburton Lewis | 150 |

| A “creepy” tale that ends in a shuddering, breath-taking way. | ||

| The House of Death | F. Georgia Stroup | 156 |

| The strange secret of a lonely woman. | ||

| The Gallows | I. W. D. Peters | 161 |

| An out-of-the-ordinary story. | ||

| The Skull | Harold Ward | 164 |

| A grim tale with a terrifying end. | ||

| The Ape-Man | James B. M. Clark, Jr. | 169 |

| A Jungle tale that is somehow “different.” | ||

| The Dead Man’s Tale | Willard E. Hawkins | 7 |

| An astounding yarn that will hold you spellbound and make you breathe fast with a new mental sensation. | ||

| Ooze | Anthony M. Rud | 19 |

| A Remarkable short novel by a master of “gooseflesh” fiction. | ||

| The Chain | Hamilton Craigie | 77 |

| Craigie is at his best here. | ||

| The Thing of a Thousand Shapes | Otis Adelbert Kline | 32 |

| Don’t start this story late at night. | ||

| THE EYRIE | THE EDITOR | 180 |

[4]

TALES of horror—or “gooseflesh” stories—are commonly shunned by magazine editors. Few, if any, will consider such a story, no matter how interesting it may be. They believe that the public doesn’t want this sort of fiction. We, however, believe otherwise. We believe there are tens of thousands—perhaps hundreds of thousands—of intelligent renders who really enjoy “gooseflesh” stories. Hence—

WEIRD TALES offers such fiction as you can find in no other magazine—fantastic stories, extraordinary stories, grotesque stories, stories of strange and bizarre adventure—the sort of stories, in brief, that will startle and amaze you. Every story in this issue of WEIRD TALES is an odd and remarkable flight of man’s imagination. Some are “creepy,” some deal in masterly fashion with “forbidden” subjects, like insanity, some are concerned with the supernatural and others with material things of horror—all are out of the ordinary, surprisingly new and unusual. A sensational departure from the beaten track—that is the reason for

[7]

THE curious narrative that follows was found among the papers of the late Dr. John Pedric, psychical investigator and author of occult works. It bears evidences of having been received through automatic writing, as were several of his publications. Unfortunately, there are no records to confirm this assumption, and none of the mediums or assistants employed by him in his research work admits knowledge of it. Possibly—for the Doctor was reputed to possess some psychic powers—it may have been received by him. At any rate, the lack of data renders the recital useless as a document for the Society for Psychical Research. It is published for whatever intrinsic interest or significance it may possess. With reference to the names mentioned, it may be added that they are not confirmed by the records of the War Department. It could be maintained, however, that purposely fictitious names were substituted, either by the Doctor or the communicating entity.

THEY called me—when I walked the earth in a body of dense matter—Richard Devaney. Though my story has little to do with the war, I was killed in the second battle of the Marne, on July 24, 1918.

Many times, as men were wont to do who felt the daily, hourly imminence of death in the trenches, I had pictured that event in my mind and wondered what it would be like. Mainly I had inclined toward a belief in total extinction. That, when the vigorous, full-blooded body I possessed should lie bereft of its faculties, I, as a creature apart from it, should go on, was beyond credence.[8] The play of life through the human machine, I reasoned, was like the flow of gasoline into the motor of an automobile. Shut off that flow, and the motor became inert, dead, while the fluid which had given it power was in itself nothing.

And so, I confess, it was a surprise to discover that I was dead and yet not dead.

I did not make the discovery at once. There had been a blinding concussion, a moment of darkness, a sensation of falling—falling—into a deep abyss. An indefinite time afterward, I found myself standing dazedly on the hillside, toward the crest of which we had been pressing against the enemy. The thought came that I must have momentarily lost consciousness. Yet now I felt strangely free from physical discomfort.

What had I been doing when that moment of blackness blotted everything out? I had been dominated by a purpose, a flaming desire——

Like a flash, recollection burst upon me, and, with it, a blaze of hatred—not toward the Boche gunners, ensconced in the woods above us, but toward the private enemy I had been about to kill.

It had been the opportunity for which I had waited interminable days and nights. In the open formation, he kept a few paces ahead of me. As we alternately ran forward, then dropped on our bellies and fired, I had watched my chance. No one would suspect, with the dozens who were falling every moment under the merciless fire from the trees beyond, that the bullet which ended Louis Winston’s career came from a comrade’s rifle.

Twice I had taken aim, but withheld my fire—not from indecision, but lest, in my vengeful heat, I might fail to reach a vital spot. When I raised my rifle the third time, he offered a fair target.

God! how I hated him. With fingers itching to speed the steel toward his heart, I forced myself to remain calm—to hold fire for that fragment of a second that would insure careful aim.

Then, as the pressure of my finger tightened against the trigger, came the blinding flash—the moment of blackness.

I HAD evidently remained unconscious longer than I realized.

Save for a few figures that lay motionless or squirming in agony on the field, the regiment had passed on, to be lost in the trees at the crest of the hill. With a pang of disappointment, I realized that Louis would be among them.

Involuntarily I started onward, driven still by that impulse of burning hatred, when I heard my name called.

Turning in surprise, I saw a helmeted figure crouching beside something huddled in the tall grass. No second glance was needed to tell me that the huddled something was the body of a soldier. I had eyes only for the man who was bending over him. Fate had been kind to me. It was Louis.

Apparently, in his preoccupation, he had not noticed me. Coolly I raised my rifle and fired.

The result was startling. Louis neither dropped headlong nor looked up at the report. Vaguely I questioned whether there had been a report.

Thwarted, I felt the lust to kill mounting in me with redoubled fury. With rifle upraised, I ran toward him. A terrific swing, and I crashed the stock against his head.

It passed clear through! Louis remained unmoved.

Uncomprehending, snarling, I flung the useless weapon away and fell upon him with bare hands—with fingers that strained to rend and tear and strangle.

Instead of encountering solid flesh and bone, they too passed through him.

Was it a mirage? A dream? Had I gone crazy? Sobered—for a moment forgetful of my fury—I drew back and tried to reduce the thing to reason. Was Louis but a figment of the imagination—a phantom?

My glance fell upon the figure beside which he was sobbing incoherent words of entreaty.

[9]

I gave a start, then looked more closely.

The dead man—for there was no question about his condition, with a bloody shrapnel wound in the side of his head—was myself!

Gradually the import of this penetrated my consciousness. Then I realized that it was Louis who had called my name—that even now he was sobbing it over and over.

The irony of it struck me at the moment of realization. I was dead—I was the phantom—who had meant to kill Louis!

I looked at my hands, my uniform—I touched my body. Apparently I was as substantial as before the shrapnel buried itself in my head. Yet, when I had tried to grasp Louis, my hand seemed to encompass only space.

Louis lived, and I was dead!

The discovery for a time benumbed my feeling toward him. With impersonal curiosity, I saw him close the eyes of the dead man—the man who, somehow or other, had been me. I saw him search the pockets and draw forth a letter I had written only that morning, a letter addressed to——

With a sudden surge of dismay, I darted forward to snatch it from his hands. He should not read that letter!

Again I was reminded of my impalpability.

But Louis did not open the envelope, although it was unsealed. He read the superscription, kissed it, as sobs rent his frame, and thrust the letter inside his khaki jacket.

“Dick! Buddie!” he cried brokenly. “Best pal man ever had—how can I take this news back to her!”

My lips curled. To Louis, I was his pal, his buddie. Not a suspicion of the hate I bore him—had borne him ever since I discovered in him a rival for Velma Roth.

Oh, I had been clever! It was our “unselfish friendship” that endeared us both to her. A sign of jealousy, of ill nature, and I would have forfeited the paradise of her regard that apparently I shared with Louis.

I had never felt secure of my place in that paradise. True, I could always awaken a response in her, but I must put forth effort in order to do so. He held her interest, it seemed, without trying. They were happy with each other and in each other.

Our relations might be expressed by likening her to the water of a placid pool, Louis to the basin that held her, me to the wind that swept over it. By exerting myself, I could agitate the surface of her nature into ripples of pleasurable excitement—could even lash her emotion into a tempest. She responded to the stimulation of my mood, yet, in my absence, settled contentedly into the peaceful comfort of Louis’ steadfast love.

I felt vaguely then—and am certain now, with a broader perspective toward realities—that Velma intuitively recognized Louis as her mate, yet feared to yield herself to him because of my sway over her emotional nature.

When the great war came, we all, I am convinced, felt that it would absolve Velma from the task of choosing between us.

Whether the agony that spoke from the violet depths of her eyes when we said good-by was chiefly for Louis or for me, I could not tell. I doubt if she could have done so. But in my mind was the determination that only one of us should return, and—Louis would not be that one.

Did I feel no repugnance at thought of murdering the man who stood in my way? Very little. I was a savage at heart—a savage in whom desire outweighed anything that might stand in the way of gaining its object. From my point of view, I would have been a fool to pass the opportunity.

Why I should have so hated him—a mere obstacle in my path—I do not know. It may have been due to a prescience of the intangible barrier his blood would always raise between Velma and me—or to a slumbering sense of remorse.

But, speculation aside, here I was, in a state of being that the world calls death, while Louis lived—was free to return home—to claim Velma—to flaunt his possession of all that I held precious.

[10]

It was maddening! Must I stand idly by, helpless to prevent this?

I HAVE wondered, since, how I could remain so long in touch with the objective world—why I did not at once, or very soon, find myself shut off from earthly sights and sounds as those in physical form are shut off from the things beyond.

The matter seems to have been determined by my will. Like weights of lead, envy of Louis and passionate longing for Velma held my feet to the sphere of dense matter.

Vengeful, despairing, I watched beside Louis. When at last he turned away from my body and, with tears streaming from his eyes, began to drag a useless leg toward the trenches we had left, I realized why he had not gone on with the others to the crest of the hill. He, too, was a victim of Boche gunnery.

I walked beside the stretcher-bearers when they had picked him up and were conveying him toward the base hospital. Throughout the weeks that followed I hovered near his cot, watching the doctors as they bound up the lacerated tendons in his thigh, and missing no detail of his battle with the fever.

Over his shoulder I read the first letter he wrote home to Velma, in which he gave a belated account of my death, dwelling upon the glory of my sacrifice.

“I have often thought that you two were meant for each other” [he wrote] “and that if it had not been for fear of hurting me, you would have been his wife long ago. He was the best buddie a man ever had. If only I could have been the one to die!”

Had I known it, I could have followed this letter across seas—could, in fact, have passed it and, by an exercise of the will, have been at Velma’s side in the twinkling of an eye. But my ignorance of the laws of the new plane was total. All my thoughts were centered upon a problem of entirely different character.

Never was hold upon earthly treasure more reluctantly relinquished than was my hope of possessing Velma. Surely, death could not erect so absolute a barrier. There must be a way—some loophole of communication—some chance for a disembodied man to contend with his corporeal rival for a woman’s love.

Slowly, very slowly, dawned the light of a plan. So feeble was the glimmer that it would scarcely have comforted one in less desperate straits, but to me it appeared to offer a possible hope. I set about methodically, with infinite patience, evolving it into something tangible, even though I had but the most indefinite idea of what the outcome might be.

The first suggestion came when Louis had so far recovered that but little trace of the fever remained. One afternoon, as he lay sleeping, the mail-distributor handed a letter to the nurse who happened to be standing beside his cot. She glanced at it, then tucked it under his pillow.

The letter was from Velma, and I was hungry for the contents. I did not then know that I could have read it easily, sealed though it was. In a frenzy of impatience, I exclaimed:

“Wake up, confound it, and read your letter!”

With a start, he opened his eyes. He looked around with a bewildered expression.

“Under your pillow!” I fumed. “Look under your pillow!”

In a dazed manner, he put his hand under the pillow and drew forth the letter.

A few hours later, I heard him commenting on the experience to the nurse.

“Something seemed to wake me up,” he said, “and I had a peculiar impulse to feel under the pillow. It was just as if I knew I would find the letter there.”

The circumstances seemed as remarkable to me as it did to him. It might be coincidence, but I determined to make a further test.

A series of experiments convinced me that I could, to a very slight degree, impress my thoughts and will upon Louis, especially when he was tired or[11] on the borderland of sleep. Occasionally I was able to control the direction of his thoughts as he wrote home to Velma.

On one occasion, he was describing for her a funny little French woman who visited the hospital with a basket that always was filled with cigarettes and candy.

“Last time” [he wrote], “she brought with her a boy whom she called....”

He paused, with pencil upraised, trying to recall the name.

A moment later, he looked down at the page and stared with astonishment. The words, “She called him Maurice,” had been added below the unfinished line.

“I must be going daffy,” he muttered. “I’d swear I didn’t write that.”

Behind him, I stood rubbing my hands in triumph. It was my first successful effort to guide the pencil while his thoughts strayed elsewhere.

Another time, he wrote to Velma:

“I’ve a strange feeling, lately, that dear old Dick is near. Sometimes, as I wake up, I seem to remember vaguely having seen him in my dreams. It’s as if his features were just fading from view.”

He paused here so long that I made another attempt to take advantage of his abstraction.

By an effort of the will that it is difficult to explain, I guided his hand into the formation of the words:

“With a jugful of kisses for Winkie, as ever her....”

Just then, Louis looked down.

“Good God!” he exclaimed, as if he had seen a ghost.

“WINKIE” was a pet name I had given Velma when we were children together.

Louis always maintained there was no sense in it, and refused to adopt it, though I frequently called her by the name in later years. And of his own volition, Louis would never have mentioned anything so convivial as a jugful of kisses.

So, through the weary months before he was invalided home, I worked. When he left France at the debarkation point, he still walked on crutches, but with the promise of regaining the unassisted use of his leg before very long. Throughout the voyage, I hovered near him, sharing his impatience, his longing for the one we both held dearest.

Over the exquisite pain of the reunion—at which I was present, yet not present—I shall pass briefly. More beautiful than ever, more appealing with her vivid, deep coloring, Velma in the flesh was a vision that stirred my longing into an intense flame.

Louis limped painfully down the gangplank. When they met, she rested her head silently on his shoulder for a moment, then—her eyes brimming with tears—assisted him, with the tender solicitude of a mother, to the machine she had in waiting.

Two months later they were married. I felt the pain of this less deeply than I would have done had it not been essential to my designs.

Whatever vague hope I may have had, however, of vicariously enjoying the delights of love were disappointed. I could not have explained why—I only knew that something barred me from intruding upon the sacred intimacies of their life, as if a defensive wall were interposed. It was baffling, but a very present fact, against which I found it useless to rebel. I have since learned—but no matter. * * *

This had no bearing on my purpose, which hinged upon the ability I was acquiring of influencing Louis’ thoughts and actions—of taking partial control of his faculties.

The occupation into which he drifted, restricted in choice as he was by the stiffened leg, helped me materially. Often, after an interminable shift at the bank, he would plod home at night with brain so weary and benumbed that it was a simple matter to impress my will upon him. Each successful attempt, too, made the next one easier.

[12]

The inevitable consequence was that in time Velma should notice his aberrations and betray concern.

“Why did you say to me, when you came in last night, ‘There’s a blue Billy-goat on the stairs—I wish they’d drive him out’?” she demanded one morning.

He looked down shamefacedly at the tablecloth.

“I don’t know what made me say it. I seemed to want to say it, and that was the only way to get it off my mind. I thought you’d take it as a joke.” He shifted his shoulders, as if trying to dislodge an unpleasant burden.

“And was that what made you wear a necktie to bed?” she asked, ironically.

He nodded an affirmative. “I knew it was idiotic—but the idea kept running in my mind. It seemed as if the only way I could go to sleep was to give in to it. I don’t have these freaks unless I’m very tired.”

She said nothing more at the time, but that evening she broached the subject of his looking for an opening in some less sedentary occupation—a subject to which she thereafter constantly recurred.

Then came a development that surprised and excited me with its possibilities.

Exhausted, drained to the last drop of his nerve-force, Louis was returning late one night from the bank, following the usual month-end overtime grind. As he walked from the car-line, I hovered over him, subduing his personality, forcing it under control, with the effort of will I had gradually learned to direct upon him. The process can only be explained in a crude way: It was as if I contended with him, sometimes successfully, for possession of the steering-wheel of the human car that he drove.

Velma was waiting when we arrived. As Louis’ feet sounded on the threshold of their apartment, she opened the door, caught his hands, and drew him inside.

At the action, I felt inexplicably thrilled. It was as if some marvelous change had come over me. And then, as I met her gaze, I knew what that change was.

I held her hands in real flesh-and-blood contact. I was looking at her with Louis’ sight!

THE shock of it cost me what I had gained. Shaken from my poise, I felt the personality I had subdued regain its sway.

The next moment, Louis was staring at Velma in bewilderment. Her eyes were filled with alarm.

“You—you frightened me!” she gasped, withdrawing her hands, which I had all but crushed. “Louis, dear—don’t ever look at me again like that!”

I can imagine the devouring intensity of gaze that had blazed forth from the features in that brief moment when they were mine.

From this time, my plans quickly took form. Two modes of action presented themselves. The first and more alluring, however, I was forced to abandon. It was none other than the wild dream of acquiring exclusive possession of Louis’ body—of forcing him down, out, and into the secondary place I had occupied.

Despite the progress I had made, this proved inexpressibly difficult. For one thing, there seemed an affinity between Louis’ body and his personality, which forced me out when he was moderately rested. This bond I might have weakened, but there were other factors.

One was the growing conviction on his part that something was radically wrong. With a faculty I had discovered of putting myself en rapport with him and reading his thoughts, I knew that at times he feared that he was going insane.

I once had the experience of accompanying him to an alienist and there, like the proverbial fly on the wall, overhearing learned scientific names applied to my efforts. The alienist spoke of “dual personality,” “amnesia,” and “the subconscious mind,” while I laughed in my (shall I say?) ghostly sleeve.

But he advised Louis to seek a complete rest and, if possible, to go into the country to build up physically—which[13] was what I desired most to prevent.

I could not play the Mr. Hyde to his Dr. Jekyll if Louis maintained his normal virility.

Velma’s fears, too, I knew were growing more acute. As insistently as she could, without betraying too openly her alarm, she pressed him to give up the bank position and seek work in the open air—work that would prove less devitalizing to a person of his peculiar temperament.

One of the results of debility from overwork is, apparently, that it deprives the victim of his initiative—makes him fearful of giving up his hold upon the meager means of sustenance that he has, lest he shall be unable to grasp another. Louis was in debt, earning scarcely enough for their living expenses, too proud to let Velma help as she longed to do, his game leg putting him at a disadvantage in the industrial field. In fact, he was in just the predicament I desired, but I knew that in time her wishes would prevail.

The circumstances, however, that deprived me of all hope of completely usurping his place was this: I could not, for any length of time, face the gaze of Velma’s eyes. The personified truth, the purity that dwelt in them, seemed to dissolve my power, to beat me back into the secondary relationship I had come to occupy toward Louis.

He was sometimes tempted to tell her: “You give me my one grip on sanity.”

I have witnessed his panic at the thought of losing her, at the thought that some day she might give him up in disgust at his aberrations, and abandon him to the formless “thing” that haunted him.

Curious—to be of the world and yet not of it—to enjoy a perspective that reveals the hidden side of effects, which seem so mysterious from the material side of the veil. But I would gladly have given all the advantages of my disembodied state for one hour of flesh-and-blood companionship with Velma.

My alternative plan was this:

If I could not enter her world, what was to prevent me from bringing Velma into mine?

DARING? To be sure.

Unversed as I was in the laws that govern this mystery of passing from the physical into another state of existence, I could only hope that the plan would work. It might—and that was enough for me. I took a gambler’s chance. By risking all, I might gain all—might gain—

The thought of what I might gain transported me to a heaven of pain and ecstasy.

Velma and I—in a world apart—a world of our own—free from the sordid trammels that mar the perfection of the rosiest earth-existence. Velma and I—together through all eternity!

This much reason I had for hoping! I observed that other persons passed through the change called death, and that some entered a state of being in which I was conscious of them and they of me. Uninteresting creatures they were, almost wholly preoccupied with their former earth-interests; but they were as much in the world as I had been in the world of Velma and Louis before that fragment of shrapnel ruled me out of the game.

A few, it was true, on passing from their physical habitations, seemed to emerge into a sphere to which I could not follow. This troubled me. Velma might do likewise. Yet I refused to admit the probability—refused to consider the possible failure of my plan. The very intensity of my longing would draw her to me.

The gulf that separated us was spanned by the grave. Once Velma had crossed to my side of the abyss, there would be no going back to Louis.

Yet I was cunning. She must not come to me with overpowering regrets that would cause her to hover about Louis as I now hovered about her. If I could inspire her with horror and loathing for him—ah! if I only could!

As a preliminary step, I must induce Louis to buy the instrument with which[14] my purpose was to be accomplished. This was not easy, for on nights when he left the bank during shopping hours he was sufficiently vigorous to resist my will. I could work only through suggestion.

In a pawnshop window that he passed daily I had noticed a revolver prominently displayed. My whole effort was concentrated upon bringing this to his attention.

The second night, he glanced at the revolver, but did not stop. Three nights later, drawn by a fascination for which he could not have accounted, he paused and looked at it for several minutes, fighting an urge that seemed to command: “Step in and buy! Buy! Buy!”

When, a few evenings later, he arrived home with the revolver and a box of cartridges that the pawnbroker had included in the sale, he put them hastily out of sight in a drawer of his desk.

He said nothing about his purchase, but the next day Velma came across the weapon and questioned him regarding it.

Visibly confused, he replied: “Oh, I thought we might need something of the sort. Saw it in a window, and the notion of having it sort of took hold of me. There’s been a lot of housebreaking lately, and it’s just as well to be prepared.”

And now with impatience I waited for the opportunity to stage my dénouement.

It came, naturally, at the end of the month, when Louis, after a prolonged day’s work, returned home, soon after midnight, his brain benumbed with poring over interminable columns of figures. When his feet ascended the stairs to his apartment it was not his faculties that directed them, but mine—cunning, alert, aflame with deadly purpose.

Never was more weird preliminary to a murder—the entering, in guise of a dear, familiar form, of a fiend incarnate, intent upon destroying the flower of the home.

I speak of a fiend incarnate, even though I was that fiend, for I did not enter Louis’s body in full expression of my faculties. Taking up physical life, my recollection of existence as a spirit entity was always shadowy. I carried through the dominating impulses that had actuated me on entering the body, but scarcely more.

And the impulse I had carried through that night was the impulse to kill.

WITH utmost caution, I entered the bedroom.

My control of Louis’s body was complete. I felt, for perhaps the first time, so corporeally secure that the vague dread of being driven out did not oppress me.

The room was dark, but the soft, regular breathing of Velma, asleep, reached my ears. It was like the invitation that rises in the scent of old wine which the lips are about to quaff—quickening my eagerness and setting my brain on fire.

I did not think of love. I lusted—but my lust was to destroy that beautiful body—to kill!

However, I was cunning—cunning. With caution, I felt my way toward the desk and secured the revolver, filling its chambers with leaden emissaries of death.

When all was in readiness, I switched on the light.

She wakened almost instantly. As the radiance flooded the room, a startled cry rose to her lips. It froze, unuttered, as—half rising—she met my gaze.

Her beauty—the raven blackness of her hair falling over her bare shoulders and full, heaving bosom, fanned the flame of my gory passion into fury. In an ecstasy of triumph, I stood drinking in the picture.

While I temporized with the lust to kill—prolonging the exquisite sensation—she was battling for self-control.

“Louis!” The name was gasped through bloodless lips.

Involuntarily, I shrank, reeling a little under her gaze. A dormant something seemed to rise in feeble protest at what I sought to do. The leveled revolver wavered in my hand.

[15]

But the note of panic in her voice revived my purpose. I laughed—mockingly.

“Louis!” her tone was sharp, but edged with terror. “Louis—put down that pistol! You don’t know what you are doing.”

She struggled to her feet and now stood before me. God! how beautiful—how tempting that bare white bosom!

“Put down that pistol!” she ordered hysterically.

She was frantic with fear. And her fear was like the blast of a forge upon the white heat of my passion.

I mocked her. A shrill, maniacal laugh burst from my throat. She had said I didn’t know what I was doing! Oh, yes, I did.

“I’m going to kill you!—kill you!” I shrieked, and laughed again.

She swayed forward like a wraith, as I fired. Or perhaps that was the trick played by my eyes as darkness overwhelmed me.

A FEW fragmentary pictures stand out in my recollection like clear-etched cameos on the scroll of the past.

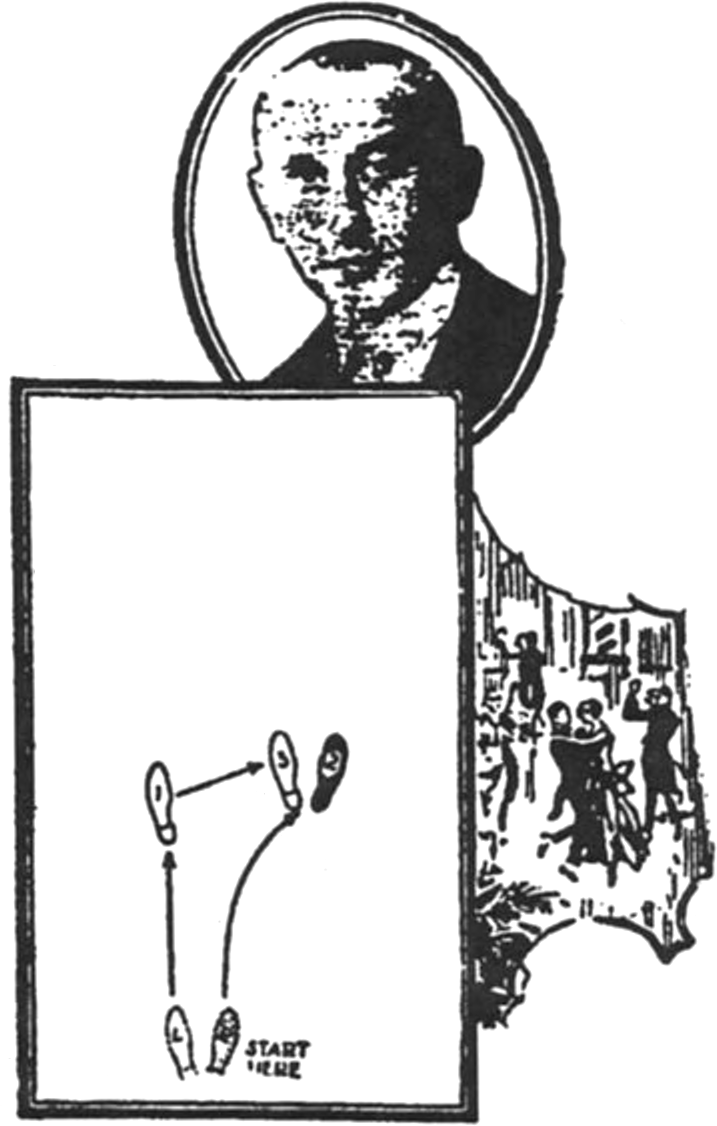

One is of Louis, standing dazedly—slightly swaying as with vertigo—looking down at the smoking revolver in his hand. On the floor before him a crumpled figure in ebony and white and vivid crimson.

Then a confusion of frightened men and women in oddly assorted nondescript attire—uniformed officers bursting into the room and taking the revolver from Louis’s unresisting hand—clumsy efforts at lifting the white-robed body to the bed—a crimson stain spreading over the sheet—a doctor, attired in collarless shirt and wearing slippers, bending over her * * *

Finally, after a lapse of hours, a hushed atmosphere—efficient nurses—the beginning of delirium.

And one other picture—of Louis, cringing behind the bars of his cell, denied the privilege of visiting his wife’s bedside—crushed, dreading the hourly announcement of her death—filled with unspeakable horror of himself.

Velma still lived. The bullet had pierced her left lung and life hung by a tenuous thread. Hovering near I watched with dispassionate interest the battle for life. For the time I seemed emotionally spent. I had made a supreme effort—events would now take their inevitable course and show whether I had accomplished my purpose. I felt neither anxious nor overjoyed, neither regretful nor triumphant—merely impersonally curious.

A fever set in lessening Velma’s slender chances of recovery. In her delirium, her thoughts seemed always of Louis. Sometimes she breathed his name pleadingly, tenderly, then cried out in terror at some fleeting rehearsal of the scene in which he stood before her, the glitter of insanity in his eyes, the leveled revolver in his hand. Again she pleaded with him to give up his work at the bank; and at other times she seemed to think of him as over on the battlefields of Europe.

Only once did she apparently think of me—when she whispered the name by which I had called her, “Winkie!” and added, “Dick!” But, save for this exception, it was always “Louis! Louis!”

Her constant reiteration of his name finally dispelled the apathy of my spirit.

Louis! All the vengeful fury toward him I had experienced when my soul went hurtling into the region of the disembodied returned with thwarted intensity.

When Velma’s fever subsided, when the long fight for recovery began and she fluttered from the borderland back into the realm of the physical, when I knew I had failed—balked of my prey, I had at least this satisfaction:

Never again would these two—the man I hated and the woman for whom I hungered—never again would they be to each other as they had been in the past. The perfection of their love had been irretrievably marred. Never would she meet his gaze without an inward shrinking. Always on his part—on[16] both their parts—there would be an undercurrent of fear that the incident might recur—a grizzly menace, poisoning each moment of their lives together.

I had not schemed and contrived—and dared—in vain.

This was the thought I hugged when Louis was released from jail, upon her refusal to prosecute. It caused me sardonic amusement when, in their first embrace, the tears of despair rained down their cheeks. It recurred when they began their pitiful attempt to build anew on the shattered foundation of love.

And then—creepingly, slyly, like a bird of ill omen casting the shadow of its silent wings over the landscape—came retribution.

Many times, in retrospect, I lived over that brief hour of my return to physical expression—my hour of realization. Wraithlike, arose a vision of Velma—Velma as she had stood before me that night, staring at me with horror. I saw the horror deepen—deepen to abject despair.

How beautiful she had looked! But when I tried to picture that beauty, I could recall only her eyes. It mattered not whether I wished to see them—they filled my vision.

They seemed to haunt me. From being vaguely conscious of them, I became acutely so. Disconcertingly, they looked out at me from everywhere—eyes brimming with fear—eyes fixed and staring—filled with horrified accusation.

The beauty I had once coveted became a thing forbidden, even in memory. If I sought to peer through the veil as formerly—to witness her pathetic attempts to resume the old life with Louis—again those eyes!

It may perhaps sound strange for a disembodied creature—one whom you would call a ghost—to wail of being haunted. Yet haunting is of the spirit, and we of the spirit world are immeasurably more subject to its conditions than those whose consciousness is centered in the material sphere.

God! Those eyes. There is a refinement of physical torture which consists of allowing water to fall, drop by drop, for an eternity of hours, upon the forehead of the victim. Conceive of this torture increased a thousandfold, and a faint idea may be gained of the torture that was mine—from seeing everywhere, constantly, interminably, two orbs ever filled with the same expression of horror and reproach.

Much have I learned since entering the Land of the Shades. At that time I did not know, as I know now, that my punishment was no affliction from without, but the simple result of natural law. Causes set in motion must work out their full reaction. The pebble, cast into a quiet pool, makes ripples which in time return to the place of their origin. I had cast more than a pebble of disturbance into the harmony of human life, and through my intense preoccupation in a single aim had delayed longer than usual the reaction, I created for myself a hell. Inevitably I was drawn into it.

Gone was every desire I had known to hover near the two who had so long engrossed my attention. Haunted, harried, scourged by those dreadful accusers, I sought to fly from them to the ends of the earth. There was no escape, yet, driven frantic, I still struggled to escape, because that is the blind impulse of suffering creatures.

The emotions that had so swayed me when I tried to blast the lives of two who held me dear now seemed puny and insignificant in comparison with my suffering. No physical torment can be likened to that which engulfed me until my very being was but a seething mass of agony. Through it, I hurled maledictions upon the world, upon myself, upon the creator. Horrible blasphemies I uttered.

And, at last—I prayed.

It was but a cry for mercy—the inarticulate appeal of a tortured soul for surcease of pain—but suddenly a peace seemed to have come upon the universe.

Bereft of suffering, I felt like one who has ceased to exist.

Out of the silence came a wordless response. It beat upon my consciousness like the buffeting of the waves.

[17]

Words known to human ears would not convey the meaning of the message that was borne upon me—whether from outside source or welling up from within, I do not know. All I know is that it filled me with a strange hope.

A thousand years or a single instant—for time is a relative thing—the respite lasted. Then, I sank, as it seemed, to the old level of consciousness, and the torment was renewed.

Endure it now I knew that I must—and why. A strange new purpose filled my being. The light of understanding had dawned upon my soul.

And so I came to resume my vigil in the home of Velma and Louis.

A BRAVE heart was Velma’s—dauntless and true.

With the effects of the tragedy still apparent in her pallor and weakness, and in the shaken demeanor and furtive, self-distrustful attitude of Louis, she yet succeeded in finding a place for him as overseer of a small country estate.

I have said that I ceased to feel the torment of passion for Velma in the greater torment of her reproach. Ah! but I had never ceased to love her. As I now realized, I had desecrated that love, had transmuted it into a horrible travesty, had, in my abysmal ignorance, sought to obtain what I desired by destroying it; yet, beneath all, I had loved.

Well I know, now, that had I succeeded in my intention toward her, Velma would have ascended to a sphere utterly beyond my comprehension. Merciful fate had diverted my aim—had made possible some faint restitution.

I returned to Velma, loving her with a love that had come into its own, a love unselfish, untainted by thought of possession.

But, to help her, I must again hurt her cruelly.

Out of the chaos of her life she had slowly restored a semblance of harmony. Almost she succeeded in convincing Louis that their old peaceful companionship had returned; but to one who could read her thoughts, the nightmare thing that hovered between them weighed cruelly upon her soul.

She was never quite able to look into her husband’s eyes without a lurking suspicion of what might lie in their depths; never able to compose herself for sleep without a tremor lest she should wake to find herself confronted by a fiend in his form. I had done my work only too well!

Now, slowly and inexorably, I began again undermining Louis’ mental control. The old ground must be traversed anew, because he had gained in strength from the respite I had allowed him, and his outdoor life gave him a mental vigor with which I had not been obliged to contend before. On the other hand, I was equipped with new knowledge of the power I intended to wield.

I shall not relate again the successive stages by which I succeeded, first in influencing his will, then in partially subduing it, and, finally, in driving his personality into the background for indefinite periods. The terror that overwhelmed him when he realized that he was becoming a prey to his former aberrations may be imagined.

To shield Velma, I performed my experiments, when possible, while he was away from her. But she could not long be unaware of the moodiness, the haggard droop of his shoulders which accompanied his realization that the old malady had returned. The deepening terror in her expression was like a scourge upon my spirit—but I must wound her in order to cure.

More than once, I was forced to exert my power over Louis to prevent him from taking violent measures against himself. As I gained the ascendancy, a determination to end it all grew upon him. He feared that unless he took himself out of Velma’s life, the insanity would return and force him again to commit a frenzied assault upon the one he held most dear. Nor could he avoid seeing the apprehension in her manner that told him[18] she knew—the shrinking that she bravely tried to conceal.

Though my power over him was greater than before, it was intermittent. I could not always exercise it. I could not, for example, prevent his borrowing a revolver one day from a neighboring farmer, on pretense of using it against a marauding dog that had lately visited the poultry yard.

Though I knew his true intention, the utmost that I could do—for his personality was strong at the time—was to influence him to postpone the deed he contemplated.

That night, I took possession of his body while he slept. Velma lay, breathing quietly, in the next room—for as this dreaded thing came upon him they had, through tacit understanding, come to occupy separate bedrooms.

Partially dressing, I stole downstairs and out to the tool-shed where Louis—fearing to trust it near him in the house—had hidden the revolver. As I returned, my whole being rebelled at the task before me—yet it was unavoidable, if I would restore to Velma what I had wrenched from her.

Quietly though I entered her room, a gasp—or rather a quick, hysterical intake of breath—warned me that she had wakened.

I flashed on the light.

She made no sound. Her face went white as marble. The expression in her eyes was that which had tortured me into the depths of a hell more frightful than any conceived by human imagination.

A moment I stood swaying before her, with leveled revolver—as I had stood on that other occasion, months before.

Slowly, I lowered the revolver, and smiled—not as Louis would have smiled but as a maniac, formed in his likeness, would have smiled.

Her lips framed the word “Louis,” but, in the grip of despair, she made no sound. It was the despair not merely of a woman who felt herself doomed to death, but of a woman who consigned her loved one to a fate worse than death.

Still I smiled—with growing difficulty, for Louis’ personality was restive and my time in the usurped body was short.

In that moment, I was not anxious to give up his body. At this new glimpse of her beauty through physical sight, my love for Velma flamed into hitherto unrealized intensity. For an instant my purpose in returning was forgotten. Forgotten was the knowledge of the ages which I had sipped since last I occupied the body in which I faced her. Forgotten was everything save—Velma.

As I took a step forward, my arms outstretched, my eyes expressing God knows what depth of yearning, she uttered a scream.

Blackness surged over me. I stumbled. I was being forced out—out—— That cry of terror had vibrated through the soul of Louis and he was struggling to answer it.

Instinctively, I battled against the darkness, clung to my hard-won ascendancy. A moment of conflict, and again I prevailed.

Once more I smiled. The effect of it must have been weird, for I was growing weaker and Louis had returned to the attack with overwhelming persistence. My tongue strove for expression:

“Sorry—Winkie—it won’t happen again—I’m not—coming—back——”

WHEN I recovered from the momentary unconsciousness that accompanies transition from the physical to spiritual, Louis was looking in affright at the huddled figure of Velma, who had fainted away. The next instant, he had gathered her in his arms.

Though I had come near failing in the attempt to deliver my message, I had no fear that my visit would prove in vain. With clear prescience, I knew that my utterance of that old familiar nickname, “Winkie,” would carry untold meaning to Velma—that hereafter she would fear no more what she might see in the depths of her husband’s eyes—that with a return of her old confidence in him, the specter of apprehension would be banished forever from their lives.

[19]

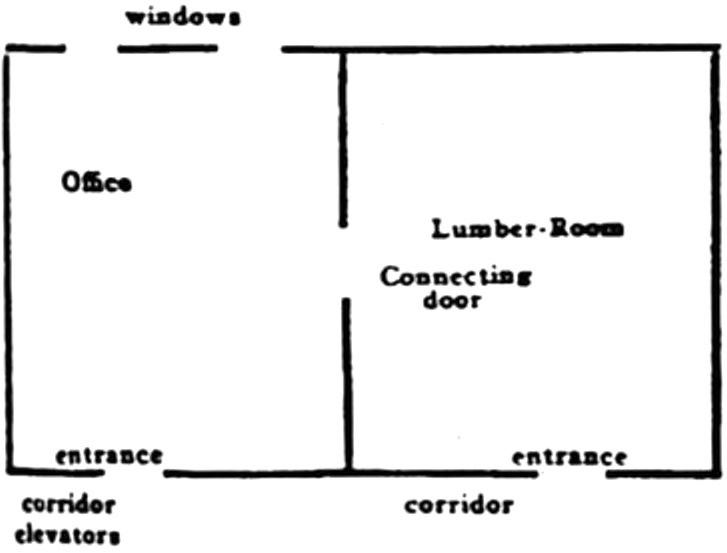

IN THE heart of a second-growth piney-woods jungle of southern Alabama, a region sparsely settled save by backwoods blacks and Cajans—that queer, half-wild people descended from Acadian exiles of the middle eighteenth century—stands a strange, enormous ruin.

Interminable trailers of Cherokee rose, white-laden during a single month of spring, have climbed the heights of its three remaining walls. Palmetto fans rise knee high above the base. A dozen scattered live oaks, now belying their nomenclature because of choking tufts of gray, Spanish moss and two-foot circlets of mistletoe parasite which have stripped bare of foliage the gnarled, knotted limbs, lean fantastic beards against the crumbling brick.

Immediately beyond, where the ground becomes soggier and lower—dropping away hopelessly into the tangle of dogwood, holly, poison sumac and pitcher plants that is Moccasin Swamp—undergrowth of titi and annis has formed a protecting wall impenetrable to all save the furtive ones. Some few outcasts utilize the stinking depths of that sinister swamp, distilling “shinny” or “pure cawn” liquor for illicit trade.

Tradition states that this is the case, at least—a tradition which antedates that of the premature ruin by many decades. I believe it, for during evenings intervening between investigations of the awesome spot I often was approached as a possible customer by wood-billies who could not fathom how anyone dared venture near without plenteous fortification of liquid courage.

I knew “shinny,” therefore I did not purchase it for personal consumption. A dozen times I bought a quart or two, merely to establish credit among the Cajans, pouring away the vile stuff immediately into the sodden ground. It seemed then that only through filtration and condensation of their dozens of weird tales regarding “Daid House” could I arrive at understanding of the mystery and weight of horror hanging about the place.

Certain it is that out of all the superstitious cautioning, head-wagging and whispered nonsensities I obtained only two indisputable facts. The first was that no money, and no supporting battery of ten-gauge shotguns loaded with chilled shot, could induce either Cajan or darky of the region to approach within five hundred yards of that flowering wall! The second fact I shall dwell upon later.

Perhaps it would be as well, as I am only a mouthpiece in this chronicle, to relate in brief why I came to Alabama on this mission.

I am a scribbler of general fact articles, no fiction writer as was Lee Cranmer—though doubtless the confession is superfluous. Lee was my roommate during college days. I knew his family well, admiring John Corliss Cranmer even more than I admired the son and friend—and almost as much as Peggy Breede whom Lee married. Peggy liked me, but that was all. I cherish sanctified memory of her for[20] just that much, as no other woman before or since has granted this gangling dyspeptic even a hint of joyous and sorrowful intimacy.

Work kept me to the city. Lee, on the other hand, coming of wealthy family—and, from the first, earning from his short-stories and novel royalties more than I wrested from editorial coffers—needed no anchorage. He and Peggy honeymooned a four-month trip to Alaska, visited Honolulu next winter, fished for salmon on Cain’s River, New Brunswick, and generally enjoyed the outdoors at all seasons.

They kept an apartment in Wilmette, near Chicago, yet, during the few spring and fall seasons they were “home,” both preferred to rent a suite at one of the country clubs to which Lee belonged. I suppose they spent thrice or five times the amount Lee actually earned, yet for my part I only honored that the two should find such great happiness in life and still accomplish artistic triumph.

They were honest, zestful young Americans, the type—and pretty nearly the only type—two million dollars cannot spoil. John Corliss Cranmer, father of Lee, though as different from his boy as a microscope is different from a painting by Remington, was even further from being dollar conscious. He lived in a world bounded only by the widening horizon of biological science—and his love for the two who would carry on that Cranmer name.

Many a time I used to wonder how it could be that as gentle, clean-souled and lovable a gentleman as John Corliss Cranmer could have ventured so far into scientific research without attaining small-caliber atheism. Few do. He believed both in God and human kind. To accuse him of murdering his boy and the girl wife who had come to be loved as the mother of baby Elsie—as well as blood and flesh of his own family—was a gruesome, terrible absurdity! Yes, even when John Corliss Cranmer was declared unmistakably insane!

Lacking a relative in the world, baby Elsie was given to me—and the middle-aged couple who had accompanied the three as servants about half of the known world. Elsie would be Peggy over again. I worshiped her, knowing that if my stewardship of her interests could make of her a woman of Peggy’s loveliness and worth I should not have lived in vain. And at four Elsie stretched out her arms to me after a vain attempt to jerk out the bobbed tail of Lord Dick, my tolerant old Airedale—and called me “papa.”

I felt a deep down choking ... yes, those strangely long black lashes some day might droop in fun or coquetry, but now baby Elsie held a wistful, trusting seriousness in depths of ultramarine eyes—that same seriousness which only Lee had brought to Peggy.

Responsibility in one instant became double. That she might come to love me as more than foster parent was my dearest wish. Still, through selfishness I could not rob her of rightful heritage; she must know in after years. And the tale that I would tell her must not be the horrible suspicion which had been bandied about in common talk!

I went to Alabama, leaving Elsie in the competent hands of Mrs. Daniels and her husband, who had helped care for her since birth.

In my possession, prior to the trip, were the scant facts known to authorities at the time of John Corliss Cranmer’s escape and disappearance. They were incredible enough.

For conducting biological research[21] upon forms of protozoan life, John Corliss Cranmer had hit upon this region of Alabama. Near a great swamp teeming with microscopic organisms, and situated in a semi-tropical belt where freezing weather rarely intruded to harden the bogs, the spot seemed ideal for his purpose.

Through Mobile he could secure supplies daily by truck. The isolation suited. With only an octoroon man to act as chef, houseman and valet for the times he entertained no visitors, he brought down scientific apparatus, occupying temporary quarters in the village of Burdett’s Corners while his woods house was in process of construction.

By all accounts the Lodge, as he termed it, was a substantial affair of eight or nine rooms, built of logs and planed lumber bought at Oak Grove. Lee and Peggy were expected to spend a portion of each year with him; quail, wild turkey and deer abounded, which fact made such a vacation certain to please the pair. At other times all save four rooms was closed.

This was in 1907, the year of Lee’s marriage. Six years later when I came down, no sign of a house remained except certain mangled and rotting timbers projecting from viscid soil—or what seemed like soil. And a twelve-foot wall of brick had been built to enclose the house completely! One portion of this had fallen inward!

I WASTED weeks of time at first, interviewing officials of the police department at Mobile, the town marshals and county sheriffs of Washington and Mobile counties, and officials of the psychopathic hospital from which Cranmer made his escape.

In substance the story was one of baseless homicidal mania. Cranmer the elder had been away until late fall, attending two scientific conferences in the North, and then going abroad to compare certain of his findings with those of a Dr. Gemmler of Prague University. Unfortunately, Gemmler was assassinated by a religious fanatic shortly afterward. The fanatic voiced virulent objection to all Mendelian research as blasphemous. This was his only defense. He was hanged.

Search of Gemmler’s notes and effects revealed nothing save an immense amount of laboratory data on karyokinesis—the process of chromosome arrangement occurring in first growing cells of higher animal embryos. Apparently Cranmer had hoped to develop some similarities, or point out differences between hereditary factors occurring in lower forms of life and those half-demonstrated in the cat and monkey. The authorities had found nothing that helped me. Cranmer had gone crazy; was that not sufficient explanation?

Perhaps it was for them, but not for me—and Elsie.

But to the slim basis of fact I was able to unearth:

No one wondered when a fortnight passed without appearance of any person from the Lodge. Why should anyone worry? A provision salesman in Mobile called up twice, but failed to complete a connection. He merely shrugged. The Cranmers had gone away somewhere on a trip. In a week, a month, a year they would be back. Meanwhile he lost commissions, but what of it? He had no responsibility for these queer nuts up there in the piney-woods. Crazy? Of course! Why should any guy with millions to spend shut himself up among the Cajans and draw microscope-enlarged notebook pictures of—what the salesman called—“germs?”

A stir was aroused at the end of the fortnight, but the commotion confined itself to building circles. Twenty carloads of building brick, fifty bricklayers, and a quarter-acre of fine-meshed wire—the sort used for screening off pens of rodents and small marsupials in a zoological garden—were ordered, damn expense, hurry! by an unshaved, tattered man who identified himself with difficulty as John Corliss Cranmer.

He looked strange, even then. A certified check for the total amount, given in advance, and another check of absurd size slung toward a labor entrepreneur,[22] silenced objection, however. These millionaires were apt to be flighty. When they wanted something they wanted it at tap of the bell. Well, why not drag down the big profits? A poorer man would have been jacked up in a day. Cranmer’s fluid gold bathed him in immunity to criticism.

The encircling wall was built, and roofed with wire netting which drooped about the squat-pitch of the Lodge. Curious inquiries of workmen went unanswered until the final day.

Then Cranmer, a strange, intense apparition who showed himself more shabby than a quay derelict, assembled every man jack of the workmen. In one hand he grasped a wad of blue slips—fifty-six of them. In the other he held a Luger automatic.

“I offer each man a thousand dollars for silence!” he announced. “As an alternative—death! You know little. Will all of you consent to swear upon your honor that nothing which has occurred here will be mentioned elsewhere? By this I mean absolute silence! You will not come back here to investigate anything. You will not tell your wives. You will not open your mouths even upon the witness stand in case you are called! My price is one thousand apiece.

“In case one of you betrays me I give you my word that this man shall die! I am rich. I can hire men to do murder. Well, what do you say?”

The men glanced apprehensively about. The threatening Luger decided them. To a man they accepted the blue slips—and, save for one witness who lost all sense of fear and morality in drink, none of the fifty-six has broken his pledge, as far as I know. That one bricklayer died later in delirium tremens.

It might have been different had not John Corliss Cranmer escaped.

THEY found him the first time, mouthing meaningless phrases concerning an amœba—one of the tiny forms of protoplasmic life he was known to have studied. Also he leaped into a hysteria of self-accusation. He had murdered two innocent people! The tragedy was his crime. He had drowned them in ooze! Ah, God!

Unfortunately for all concerned, Cranmer, dazed and indubitably stark insane, chose to perform a strange travesty on fishing four miles to the west of his lodge—on the further border of Moccasin Swamp. His clothing had been torn to shreds, his hat was gone, and he was coated from head to foot with gluey mire. It was far from strange that the good folk of Shanksville, who never had glimpsed the eccentric millionaire, failed to associate him with Cranmer.

They took him in, searched his pockets—finding no sign save an inordinate sum of money—and then put him under medical care. Two precious weeks elapsed before Dr. Quirk reluctantly acknowledged that he could do nothing more for this patient, and notified the proper authorities.

Then much more time was wasted. Hot April and half of still hotter May passed by before the loose ends were connected. Then it did little good to know that this raving unfortunate was Cranmer, or that the two persons of whom he shouted in disconnected delirium actually had disappeared. Alienists absolved him of responsibility. He was confined in a cell reserved for the violent.

Meanwhile, strange things occurred back at the Lodge—which now, for good and sufficient reason, was becoming known to dwellers of the woods as Dead House. Until one of the walls fell in, however, there had been no chance to see—unless one possessed the temerity to climb either one of the tall live oaks, or mount the barrier itself. No doors or opening of any sort had been placed in that hastily-constructed wall!

By the time the western side of the wall fell, not a native for miles around but feared the spot far more than even the bottomless, snake-infested bogs which lay to west and north.

The single statement was all John Corliss Cranmer ever gave to the world. It proved sufficient. An immediate[23] search was instituted. It showed that less than three weeks before the day of initial reckoning, his son and Peggy had come to visit him for the second time that winter—leaving Elsie behind in company of the Daniels pair. They had rented a pair of Gordons for quail hunting, and had gone out. That was the last anyone had seen of them.

The backwoods negro who glimpsed them stalking a covey behind their two pointing dogs had known no more—even when sweated through twelve hours of third degree. Certain suspicious circumstances (having to do only with his regular pursuit of “shinny” transportation) had caused him to fall under suspicious at first. He was dropped.

Two days later the scientist himself was apprehended—a gibbering idiot who sloughed his pole—holding on to the baited hook—into a marsh where nothing save moccasins, an errant alligator, or amphibian life could have been snared.

His mind was three-quarters dead. Cranmer then was in the state of the dope fiend who rouses to a sitting position to ask seriously how many Bolshevists were killed by Julius Caesar before he was stabbed by Brutus, or why it was that Roller canaries sang only on Wednesday evenings. He knew that tragedy of the most sinister sort had stalked through his life—but little more, at first.

Later the police obtained that one statement that he had murdered two human beings, but never could means or motive be established. Official guess as to the means was no more than wild conjecture; it mentioned enticing the victims to the noisome depths of Moccasin Swamp, there to let them flounder and sink.

The two were his son and daughter-in-law, Lee and Peggy!

BY FEIGNING coma—then awakening with suddenness to assault three attendants with incredible ferocity and strength—John Corliss Cranmer escaped from Elizabeth Ritter Hospital.

How he hid, how he managed to traverse sixty-odd intervening miles and still balk detection, remains a minor mystery to be explained only by the assumption that maniacal cunning sufficed to outwit saner intellects.

Traverse these miles he did, though until I was fortunate enough to uncover evidence to this effect, it was supposed generally that he had made his escape as stowaway on one of the banana boats, or had buried himself in some portion of the nearer woods where he was unknown. The truth ought to be welcome to householders of Shanksville, Burdett’s Corners and vicinage—those excusably prudent ones who to this day keep loaded shotguns handy and barricade their doors at nightfall.

The first ten days of my investigation may be touched upon in brief. I made headquarters in Burdett’s Corners, and drove out each morning, carrying lunch and returning for my grits and piney-woods pork or mutton before nightfall. My first plan had been to camp out at the edge of the swamp, for opportunity to enjoy the outdoors comes rarely in my direction. Yet after one cursory examination of the premises I abandoned the idea. I did not want to camp alone there. And I am less superstitious than a real estate agent.

It was, perhaps, psychic warning; more probably the queer, faint, salty odor as of fish left to decay, which hung about the ruin, made too unpleasant an impression upon my olfactory sense. I experienced a distinct chill every time the lengthening shadows caught me near Dead House.

The smell impressed me. In newspaper reports of the case one ingenious explanation had been worked out. To the rear of the spot where Dead House had stood—inside the wall—was a swampy hollow circular in shape. Only a little real mud lay in the bottom of the bowllike depression now, but one reporter on the staff of The Mobile Register guessed that during the tenancy of the lodge it had been a fishpool. Drying up of the water had killed the fish, who now permeated the remnant of mud with this foul odor.

[24]

The possibility that Cranmer had needed to keep fresh fish at hand for some of his experiments silenced the natural objection that in a country where every stream holds gar pike, bass, catfish and many other edible varieties, no one would dream of stocking a stagnant puddle.

After tramping about the enclosure, testing the queerly brittle, desiccated top stratum of earth within and speculating concerning the possible purpose of the wall, I cut off a long limb of chinaberry and probed the mud. One fragment of fish spine would confirm the guess of that imaginative reporter.

I found nothing resembling a piscal skeleton, but established several facts. First, this mud crater had definite bottom only three or four feet below the surface of remaining ooze. Second, the fishy stench became stronger as I stirred. Third, at one time the mud, water, or whatever had comprised the balance of content, had reached the rim of the bowl. The last showed by certain marks plain enough when the crusty, two-inch stratum of upper coating was broken away. It was puzzling.

The nature of that thin, desiccated effluvium which seemed to cover everything even to the lower foot or two of brick, came in for next inspection. It was strange stuff, unlike any earth I ever had seen, though undoubtedly some form of scum drained in from the swamp at the time of river floods or cloudbursts (which in this section are common enough in spring and fall). It crumbled beneath the fingers. When I walked over it, the stuff crunched hollowly. In fainter degree it possessed the fishy odor also.

I took some samples where it lay thickest upon the ground, and also a few where there seemed to be no more than a depth of a sheet of paper. Later I would have a laboratory analysis made.

Apart from any possible bearing the stuff might have upon the disappearance of my three friends, I felt the tug of article interest—that wonder over anything strange or seemingly inexplicable which lends the hunt for fact a certain glamor and romance all its own. To myself I was going to have to explain sooner or later just why this layer covered the entire space within the walls and was not perceptible anywhere outside! The enigma could wait, however—or so I decided.

Far more interesting were the traces of violence apparent on wall and what once had been a house. The latter seemed to have been ripped from its foundations by a giant hand, crushed out of semblance to a dwelling, and then cast in fragments about the base of wall—mainly on the south side, where heaps of twisted, broken timbers lay in profusion. On the opposite side there had been such heaps once, but now only charred sticks, coated with that gray-black, omnipresent coat of desiccation, remained. These piles of charcoal had been sifted and examined most carefully by the authorities, as one theory had been advanced that Cranmer had burned the bodies of his victims. Yet no sign whatever of human remains was discovered.

The fire, however, pointed out one odd fact which controverted the reconstructions made by detectives months before. The latter, suggesting the dried scum to have drained in from the swamp, believed that the house timbers had floated out to the sides of the wall—there to arrange themselves in a series of piles! The absurdity of such a theory showed even more plainly in the fact that if the scum had filtered through in such a flood, the timbers most certainly had been dragged into piles previously! Some had burned—and the scum coated their charred surfaces!

What had been the force which had torn the lodge to bits as if in spiteful fury? Why had the parts of the wreckage been burned, the rest to escape?

Right here I felt was the keynote to the mystery, yet I could imagine no explanation. That John Corliss Cranmer himself—physically sound, yet a man who for decades had led a sedentary life—could have accomplished such destruction, unaided, was difficult to believe.

[25]

I TURNED my attention to the wall, hoping for evidence which might suggest another theory.

That wall had been an example of the worst snide construction. Though little more than a year old, the parts left standing showed evidence that they had begun to decay the day the last brick was laid. The mortar had fallen from the interstices. Here and there a brick had cracked and dropped out. Fibrils of the climbing vines had penetrated crevices, working for early destruction.

And one side already had fallen.

It was here that the first glimmering suspicion of the terrible truth was forced upon me. The scattered bricks, even those which had rolled inward toward the gaping foundation lodge, had not been coated with scum! This was curious, yet it could be explained by surmise that the flood itself undermined this weakest portion of the wall. I cleared away a mass of brick from the spot on which the structure had stood; to my surprise I found it exceptionally firm! Hard red clay lay beneath! The flood conception was faulty; only some great force, exerted from inside or outside, could have wreaked such destruction.

When careful measurement, analysis and deduction convinced me—mainly from the fact that the lowermost layers of brick all had fallen outward, while the upper portions toppled in—I began to link up this mysterious and horrific force with the one which had rent the Lodge asunder. It looked as though a typhoon or gigantic centrifuge had needed elbow room in ripping down the wooden structure.

But I got nowhere with the theory, though in ordinary affairs I am called a man of too great imaginative tendencies. No less than three editors have cautioned me on this point. Perhaps it was the narrowing influence of great personal sympathy—yes, and love. I make no excuses, though beyond a dim understanding that some terrific, implacable force must have made this spot his playground, I ended my ninth day of note-taking and investigation almost as much in the dark as I had been while a thousand miles away in Chicago.

Then I started among the darkies and Cajans. A whole day I listened to yarns of the days which preceded Cranmer’s escape from Elizabeth Ritter Hospital—days in which furtive men sniffed poisoned air for miles around Dead House, finding the odor intolerable. Days in which it seemed none possessed nerve enough to approach close. Days when the most fanciful tales of mediaeval superstitions were spun. These tales I shall not give; the truth is incredible enough.

At noon upon the eleventh day I chanced upon Rori Pailleron, a Cajan—and one of the least prepossessing of all with whom I had come in contact. “Chanced” perhaps is a bad word. I had listed every dweller of the woods within a five mile radius. Rori was sixteenth on my list. I went to him only after interviewing all four of the Crabiers and two whole families of Pichons. And Rori regarded me with the utmost suspicion until I made him a present of the two quarts of “shinny” purchased of the Pichons.

Because long practice has perfected me in the technique of seeming to drink another man’s awful liquor—no, I’m not an absolute prohibitionist; fine wine or twelve-year-in-cask Bourbon whisky arouses my definite interest—I fooled Pailleron from the start. I shall omit preliminaries, and leap to the first admission from him that he knew more concerning Dead House and its former inmates than any of the other darkies or Cajans roundabout.

“...But I ain’t talkin’. Sacre! If I should open my gab, what might fly out? It is for keeping silent, y’r damn’ right!...”

I agreed. He was a wise man—educated to some extent in the queer schools and churches maintained exclusively by Cajans in the depths of the woods, yet naive withal.

We drank. And I never had to ask another leading question. The liquor made him want to interest me; and the only extraordinary topic in this whole neck of the woods was the Dead House.

[26]

Three-quarters of a pint of acrid, nauseous fluid, and he hinted darkly. A pint, and he told me something I scarcely could believe. Another half-pint.... But I shall give his confession in condensed form.

He had known Joe Sibley, the octoroon chef, houseman and valet who served Cranmer. Through Joe, Rori had furnished certain indispensables in way of food to the Cranmer household. At first, these salable articles had been exclusively vegetable—white and yellow turnip, sweet potatoes, corn and beans—but later, meat!

Yes, meat especially—whole lambs, slaughtered and quartered, the coarsest variety of piney-woods pork and beef, all in immense quantity!

IN DECEMBER of the fatal winter Lee and his wife stopped down at the Lodge for ten days or thereabouts.

They were enroute to Cuba at the time, intending to be away five or six weeks. Their original plan had been only to wait over a day or so in the piney-woods, but something caused an amendment to the scheme.

The two dallied. Lee seemed to have become vastly absorbed in something—so much absorbed that it was only when Peggy insisted upon continuing their trip, that he could tear himself away.

It was during those ten days that he began buying meat. Meager bits of it at first—a rabbit, a pair of squirrels, or perhaps a few quail beyond the number he and Peggy shot. Rori furnished the game, thinking nothing of it except that Lee paid double prices—and insisted upon keeping the purchases secret from other members of the household.

“I’m putting it across on the Governor, Rori!” he said once with a wink. “Going to give him the shock of his life. So you mustn’t let on, even to Joe about what I want you to do. Maybe it won’t work out, but if it does ...! Dad’ll have the scientific world at his feet! He doesn’t blow his own horn anywhere near enough, you know.”

Rori didn’t know. Hadn’t a suspicion what Lee was talking about. Still, if this rich, young idiot wanted to pay him a half dollar in good silver coin for a quail that anyone—himself included—could knock down with a five-cent shell, Rori was well satisfied to keep his mouth shut. Each evening he brought some of the small game. And each day Lee Cranmer seemed to have use for an additional quail or so....

When he was ready to leave for Cuba, Lee came forward with the strangest of propositions. He fairly whispered his vehemence and desire for secrecy! He would tell Rori, and would pay the Cajan five hundred dollars—half in advance, and half at the end of five weeks when Lee himself would return from Cuba—provided Rori agreed to adhere absolutely to a certain secret program! The money was more than a fortune to Rori; it was undreamt-of affluence. The Cajan acceded.

“He wuz tellin’ me then how the ol’ man had raised some kind of pet,” Rori confided, “an’ wanted to get shet of it. So he give it to Lee, tellin’ him to kill it, but Lee was sot on foolin’ him. W’at I ask yer is, w’at kind of a pet is it w’at lives down in a mud sink an’ eats a couple hawgs every night?”

I couldn’t imagine, so I pressed him for further details. Here at last was something which sounded like a clue!

He really knew too little. The agreement with Lee provided that if Rori carried out the provisions exactly, he should be paid extra and at his exorbitant scale of all additional outlay, when Lee returned.

The young man gave him a daily schedule which Rori showed. Each evening he was to procure, slaughter and cut up a definite—and growing—amount of meat. Every item was checked, and I saw that they ran from five pounds up to forty!

“What in heaven’s name did you do with it?” I demanded, excited now and pouring him an additional drink for fear caution might return to him.

“Took it through the bushes in back an’ slung it in the mud sink there! An’ suthin’ come up an’ drug it down!”

“A ’gator?”

“Diable! How should I know? It[27] was dark. I wouldn’t go close.” He shuddered, and the fingers which lifted his glass shook as with sudden chill. “Mebbe you’d of done it, huh? Not me, though! The young fellah tole me to sling it in, an’ I slung it.

“A couple times I come around in the light, but there wasn’t nuthin’ there you could see. Jes’ mud, an’ some water. Mebbe the thing didn’t come out in daytimes....”

“Perhaps not,” I agreed, straining every mental resource to imagine what Lee’s sinister pet could have been. “But you said something about two hogs a day? What did you mean by that? This paper, proof enough that you’re telling the truth so far, states that on the thirty-fifth day you were to throw forty pounds of meat—any kind—into the sink. Two hogs, even the piney-woods variety, weigh a lot more than forty pounds!”

“Them was after—after he come back!”

From this point onward, Rori’s tale became more and more enmeshed in the vagaries induced by bad liquor. His tongue thickened. I shall give his story without attempt to reproduce further verbal barbarities, or the occasional prodding I had to give in order to keep him from maundering into foolish jargon.

Lee had paid munificently. His only objection to the manner in which Rori had carried out his orders was that the orders themselves had been deficient. The pet, he said had grown enormously. It was hungry, ravenous. Lee himself had supplemented the fare with huge pails of scraps from the kitchen.