The Project Gutenberg eBook of The uncivilized races of men in all countries of the world; vol. 1 of 2, by John G. Wood

Title: The uncivilized races of men in all countries of the world; vol. 1 of 2

Being a comprehensive account of their manners and customs, and of their physical, social, mental, moral and religious characteristics

Author: John G. Wood

Release Date: September 30, 2022 [eBook #69073]

Language: English

Produced by: Brian Coe, Harry Lamé, Jude Eylander and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

Transcriber’s Notes

This is Volume I of II of this work, containing (after the front matter) pages 11-768, chapters I-LXXV, and illustration numbers 1-211; Volume II contains (after the front matter) page numbers 769-1481, chapters LXXVI-CLXX, and illustration numbers 212-443. For ease of reference, the Table of Contents, List of Illustrations and Index have been included in both volumes. Hyperlinks have only been provided for links internal to this volume.

More information on the transcription and the changes made may be found in the Transcriber’s Notes at the end of this text.

The cover image and music transcriptions have been created for this e-text and are in the public domain.

(See page ii.)

BEING

A COMPREHENSIVE ACCOUNT OF THEIR MANNERS AND CUSTOMS,

AND OF THEIR PHYSICAL, SOCIAL, MENTAL, MORAL AND

RELIGIOUS CHARACTERISTICS.

BY

Rev. J. G. WOOD, M.A., F.L.S.

AUTHOR OF “ILLUSTRATED NATURAL HISTORY OF ANIMALS,” “ANECDOTES OF

ANIMAL LIFE,” “HOMES

WITHOUT HANDS,” “BIBLE ANIMALS,” “COMMON OBJECTS OF THE COUNTRY AND SEASHORE,” ETC.

WITH NEW DESIGNS

BY ANGAS, DANBY, WOLF, ZWECKER, Etc., Etc.

IN TWO VOLUMES.

VOL. I.

HARTFORD:

THE J. B. BURR PUBLISHING CO.

1877.

[i]

This work is simply, as the title-page states, an account of the manners and customs of uncivilized races of men in all parts of the world.

Many travellers have given accounts, scattered rather at random through their books, of the habits and modes of life exhibited by the various people among whom they have travelled. These notices, however, are distributed through a vast number of books, many of them very scarce, many very expensive, and most of them ill-arranged; and it has therefore been my task to gather together in one work, and to present to the reader in a tolerably systematic and intelligible form, the varieties of character which develop themselves among races which have not as yet lost their individuality by modern civilization. In this task I have been greatly assisted by many travellers, who have taken a kindly interest in the work, and have given me the invaluable help of their practical experience.

The engravings with which the work is profusely illustrated have been derived from many sources. For the most part the countenances of the people have been drawn from photographs, and in many instances whole groups taken by the photographer have been transferred to the wood-block, the artist only making a few changes of attitude, so as to avoid the unpleasant stiffness which characterizes photographic groups. Many of the illustrations are taken from sketches made by travellers, who have kindly allowed me to make use of them; and I must here express my thanks to Mr. T. Baines, the accomplished artist and traveller, who made many sketches expressly for the work, and placed at my disposal the whole of his diaries and portfolios. I must also express my thanks to Mr. J. B. Zwecker, who undertook the onerous task of interpreting pictorially the various scenes of savage life which are described in the work, and who brought to that task a hearty good-will and a wide knowledge of the subject, without which the work would have lost much of its spirit. The drawings of the weapons, implements, and utensils, are all taken from actual specimens, most of which are in my own collection, made, through a series of several years, for the express purpose of illustrating this work.

That all uncivilized tribes should be mentioned, is necessarily impossible, and I have been reluctantly forced to dismiss with a brief notice, many interesting people, to whom I would gladly have given a greater amount of space. Especially has this been the case with Africa, in consequence of the extraordinary variety of the native customs which prevail in that wonderful land. We have, for example, on one side of a river, a people well clothed, well fed, well governed, and retaining but few of the old savage customs. On the other side, we find people without clothes, government, manners, or morality, and sunk as deeply as man can be in all the squalid miseries of savage life. Besides, the chief characteristic of uncivilized Africa is the continual change to which it is subject. Some tribes are warlike and restless, always working their way seaward from the interior, carrying their own customs with them, forming settlements on their way, and invariably adding to their own habits and superstitions those of the tribes among whom they have settled. In process of time they become careless of the military arts by which they gained possession of the country, and are in their turn ousted by others, who bring fresh habits and modes of life with them. It will be seen, therefore, how full of incident is life in Africa, the great stronghold of barbarism, and how necessary it is to devote to that one continent a considerable portion of the work.

[ii]

This work, which has been nearly three years going through the press in London, is one of the most valuable contributions that have been made to the literature of this generation. Rev. Dr. Wood, who ranks among the most popular and foremost writers of Great Britain, conceiving the idea of the work many years since, and commencing the collection of such articles, utensils, weapons, portraits, etc., as would illustrate the life and customs of the uncivilized races, was, undoubtedly, the best qualified of all living writers for such an undertaking. The work is so costly by reason of its hundreds of superior engravings, that few only will, or can avail themselves of the imported edition. Yet it is so replete with healthful information, so fascinating by its variety of incident, portraiture and manners, so worthy of a place in every household library, that we have reprinted it in order that it may be accessible to the multitude of readers in this country.

With the exception of a few paragraphs, not deemed essential by the American editor, and not making, in the aggregate, over four pages, the text of the two royal octavo volumes of nearly sixteen hundred pages, is given UNABRIDGED. The errors, incident to a first edition, have been corrected. By adopting a slightly smaller, yet very handsome and legible type, the two volumes are included in one. The beauty and value of the work are also greatly enhanced by grouping the engravings and uniting them, by cross references, with the letter-press they illustrate.

In one other and very essential respect is this superior to the English edition. Dr. Wood has given too brief and imperfect an account of the character, customs and life of the North American Indians, and the savage tribes of the Arctic regions. As the work was issued in monthly parts of a stipulated number, he may have found his space limited, and accordingly omitted a chapter respecting the Indians, that he had promised upon a preceding page. This deficiency has been supplied by the American editor, making the account of the Red Men more comprehensive, and adding some fine engravings to illustrate their appearance and social life. Having treated of the Ahts of Vancouver’s Island, the author crosses Behring Strait and altogether omits the interesting races of Siberia, passing at once from America to Southern Asia. To supply this chasm and make the work a complete “Tour round the World,” a thorough survey of the races “in all countries” which represent savage life, we have added an account of the Malemutes, Ingeletes and Co-Yukons of Alaska. An interesting chapter respecting the Tungusi, Jakuts, Ostiaks, and Samoiedes of Siberia, compiled from Dr. Hartwig’s “Polar World,” is also given. The usefulness and value of such a work as this are greatly enhanced by a minute and comprehensive index. In this respect, the English edition is very deficient,—its index occupying only a page. We have appended to the work one more than ten times as large, furnishing to the reader and student an invaluable help. Thus enlarged by letter-press and illustrations, this work is a complete and invaluable resumé of the manners, customs, and life of the Uncivilized Races of the World.

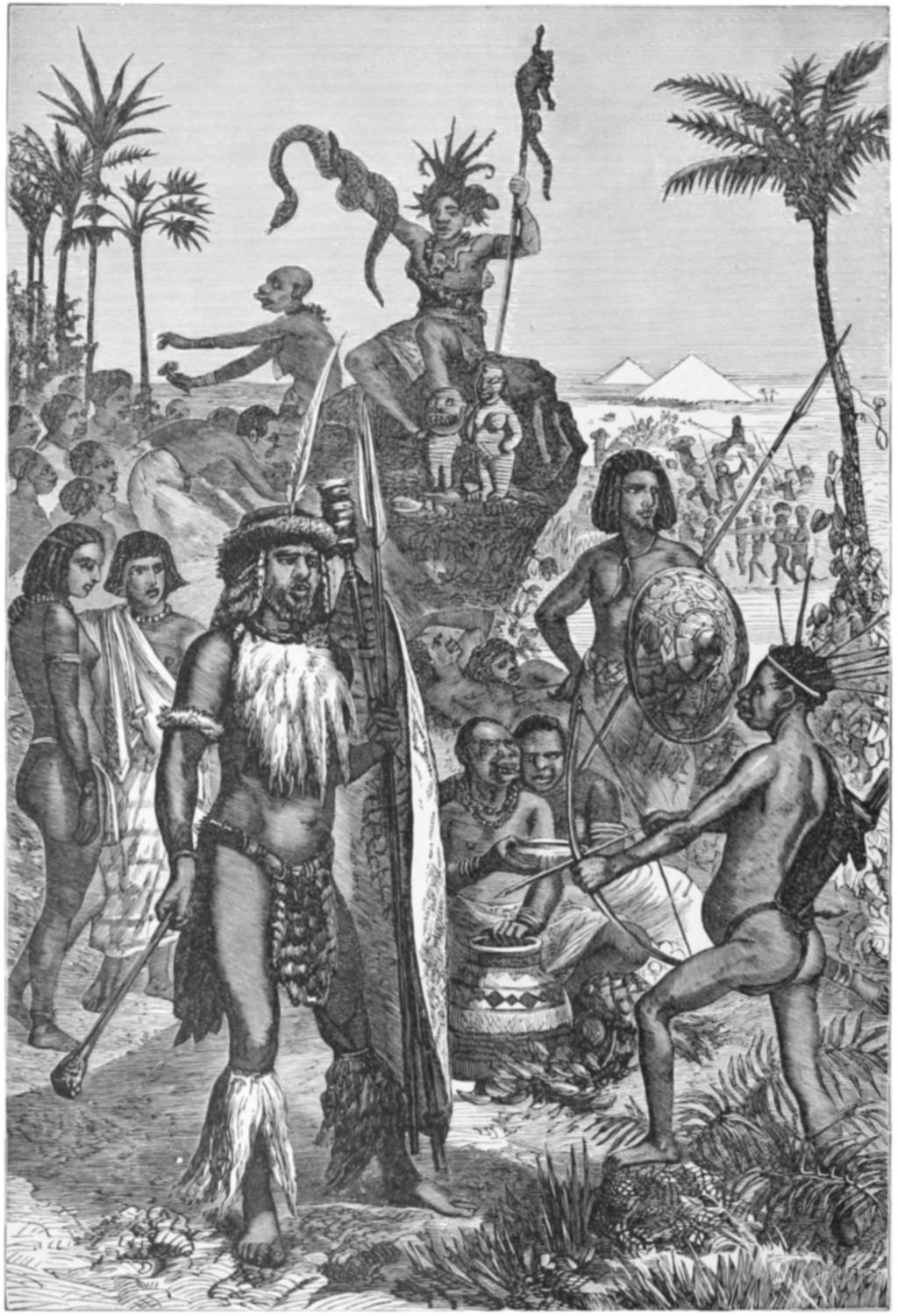

The Frontispiece gives a pictorial representation of African mankind. Superstition reigning supreme, the most prominent figure is the fetish priest, with his idols at his feet, and holding up for adoration the sacred serpent. War is illustrated by the Kaffir chief in the foreground, the Bosjesman with his bow and poisoned arrows, and the Abyssinian chief behind him. The gluttony of the Negro race is exemplified by the sensual faces of the squatting men with their jars of porridge and fruit. The grace and beauty of the young female is shown by the Nubian girl and Shooa woman behind the Kaffir; while the hideousness of the old women is exemplified by the Negro woman above with her fetish. Slavery is illustrated by the slave caravan in the middle distance, and the pyramids speak of the interest attached to Africa by hundreds of centuries.

[iii]

| Page. | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1. | Pictorial representation of African races | Frontispiece. |

| 2. | Kaffir from childhood to age | 13 |

| 3. | Old councillor and wives | 13 |

| 4. | Kaffir cradle | 18 |

| 5. | Young Kaffir armed | 21 |

| 6. | Kaffir postman | 21 |

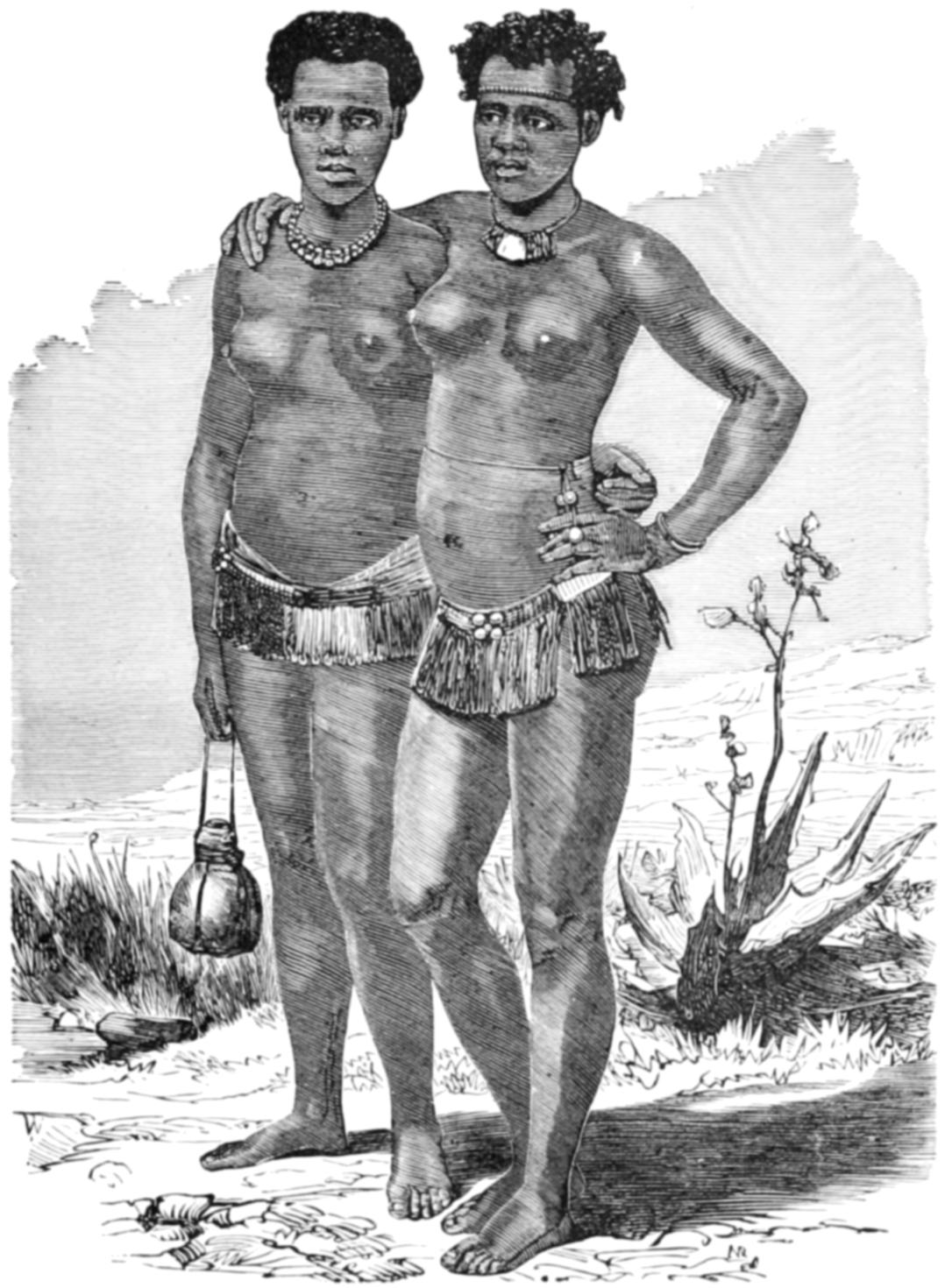

| 7. | Unmarried Kaffir girls | 25 |

| 8. | Old Kaffir women | 25 |

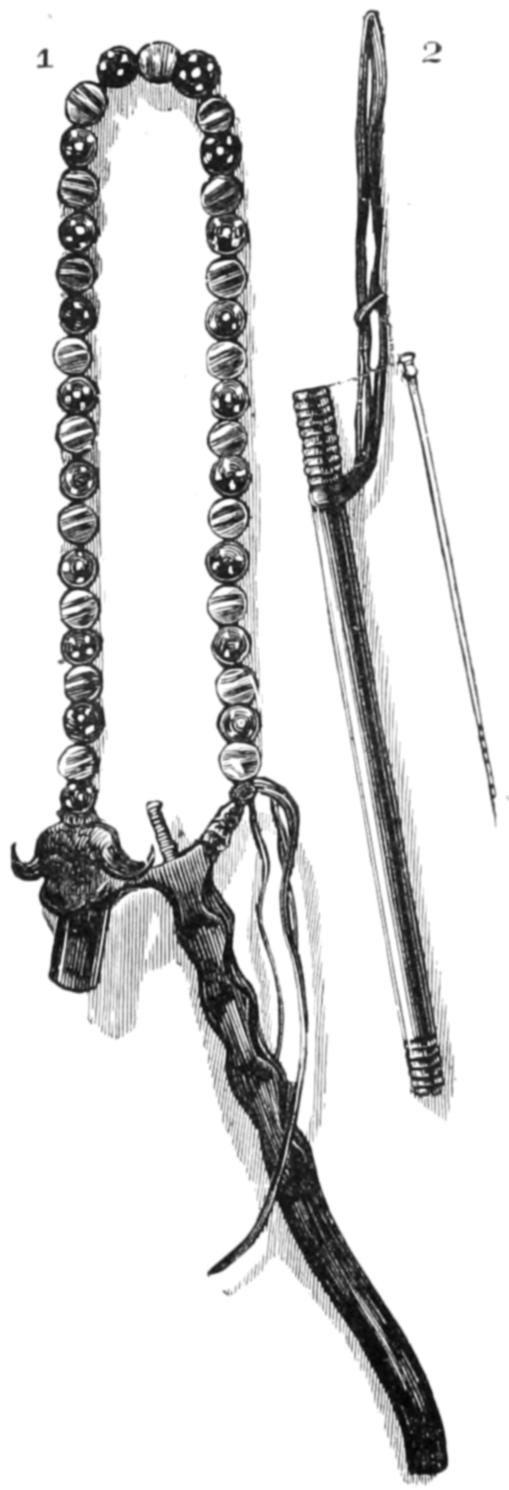

| 9. | Kaffir ornaments—necklaces, belt, etc. | 33 |

| 10. | Kaffir needles and sheaths | 33 |

| 11. | Articles of costume | 33 |

| 12. | Dolls representing the Kaffir dress | 33 |

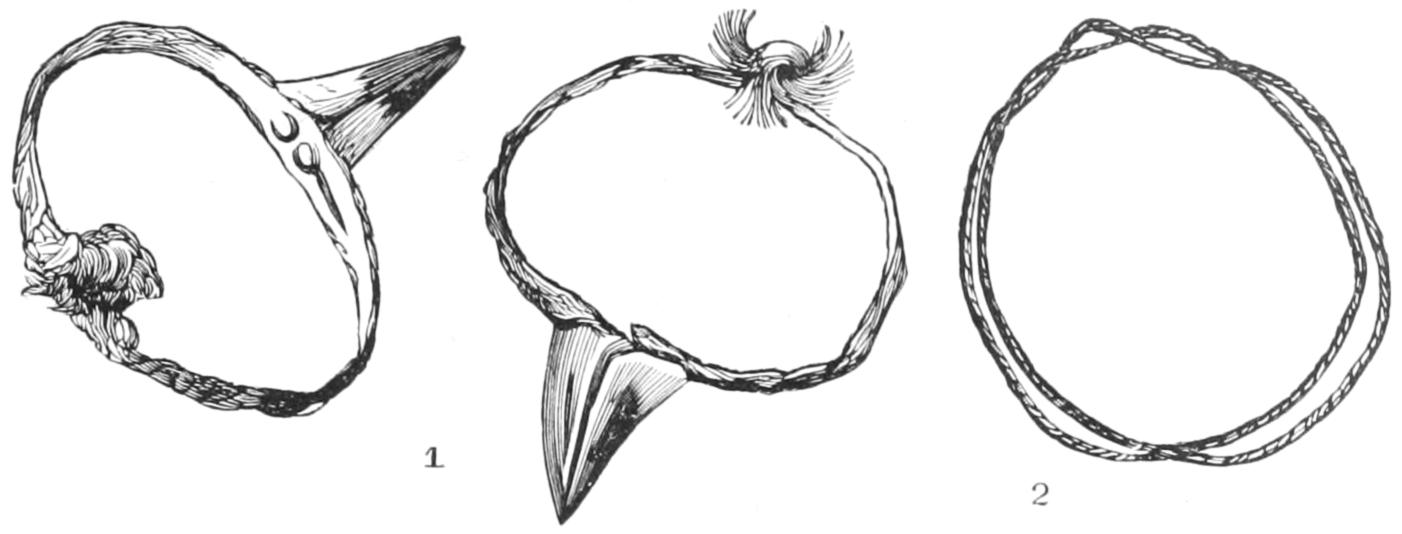

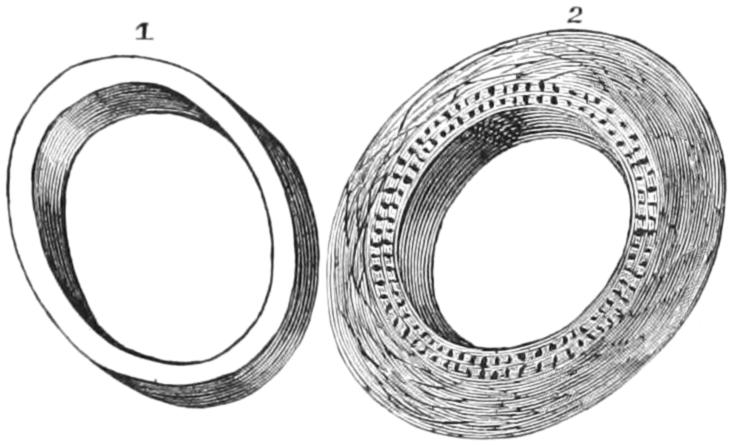

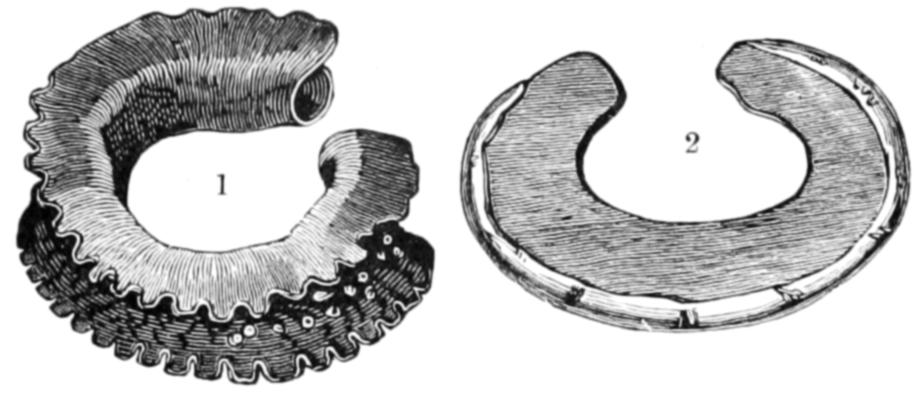

| 13. | Bracelets made of the hoof of the bluebok | 39 |

| 14. | Apron of chief’s wife | 39 |

| 15. | Ivory armlets | 39 |

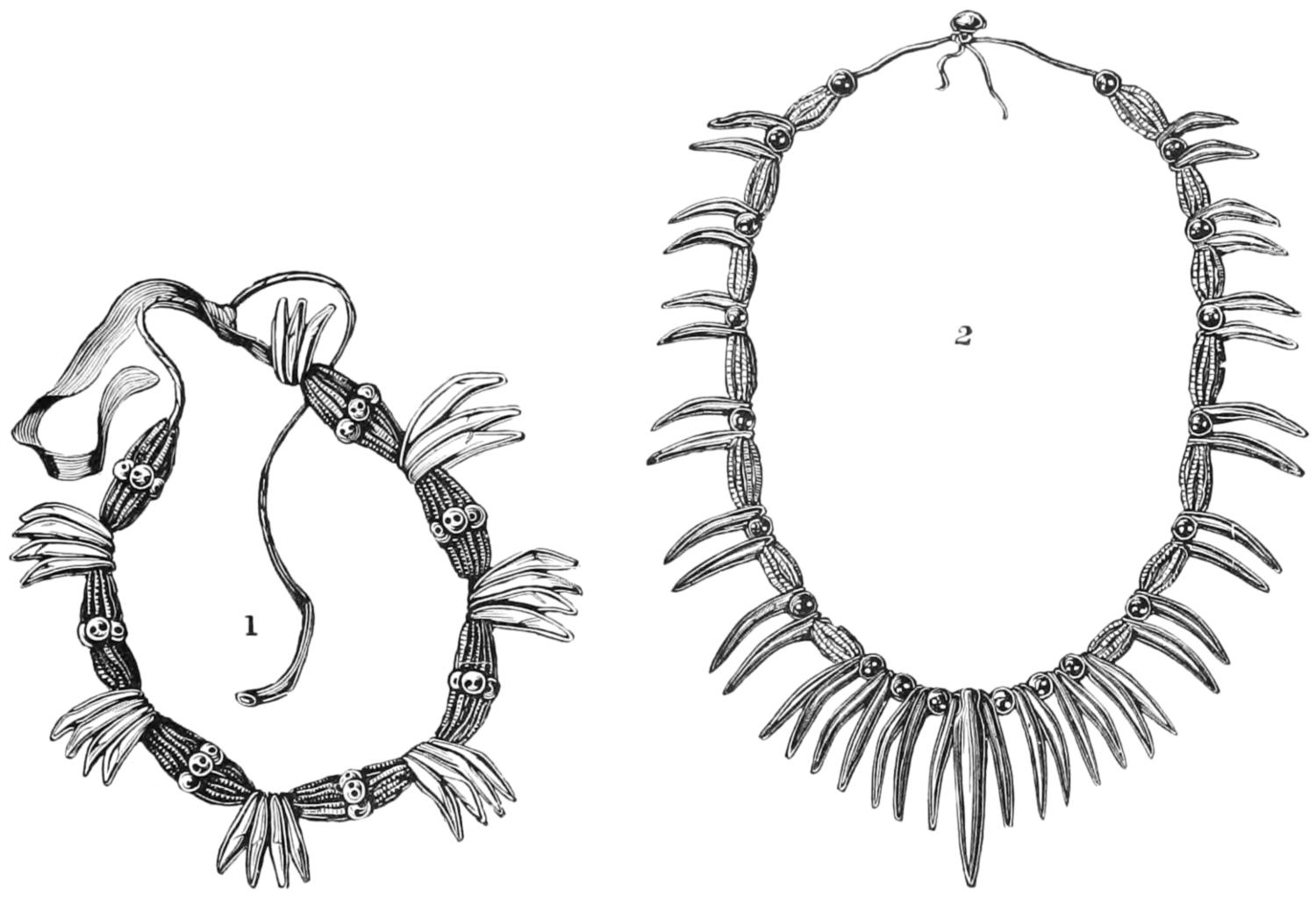

| 16. | Necklaces—beads and teeth | 39 |

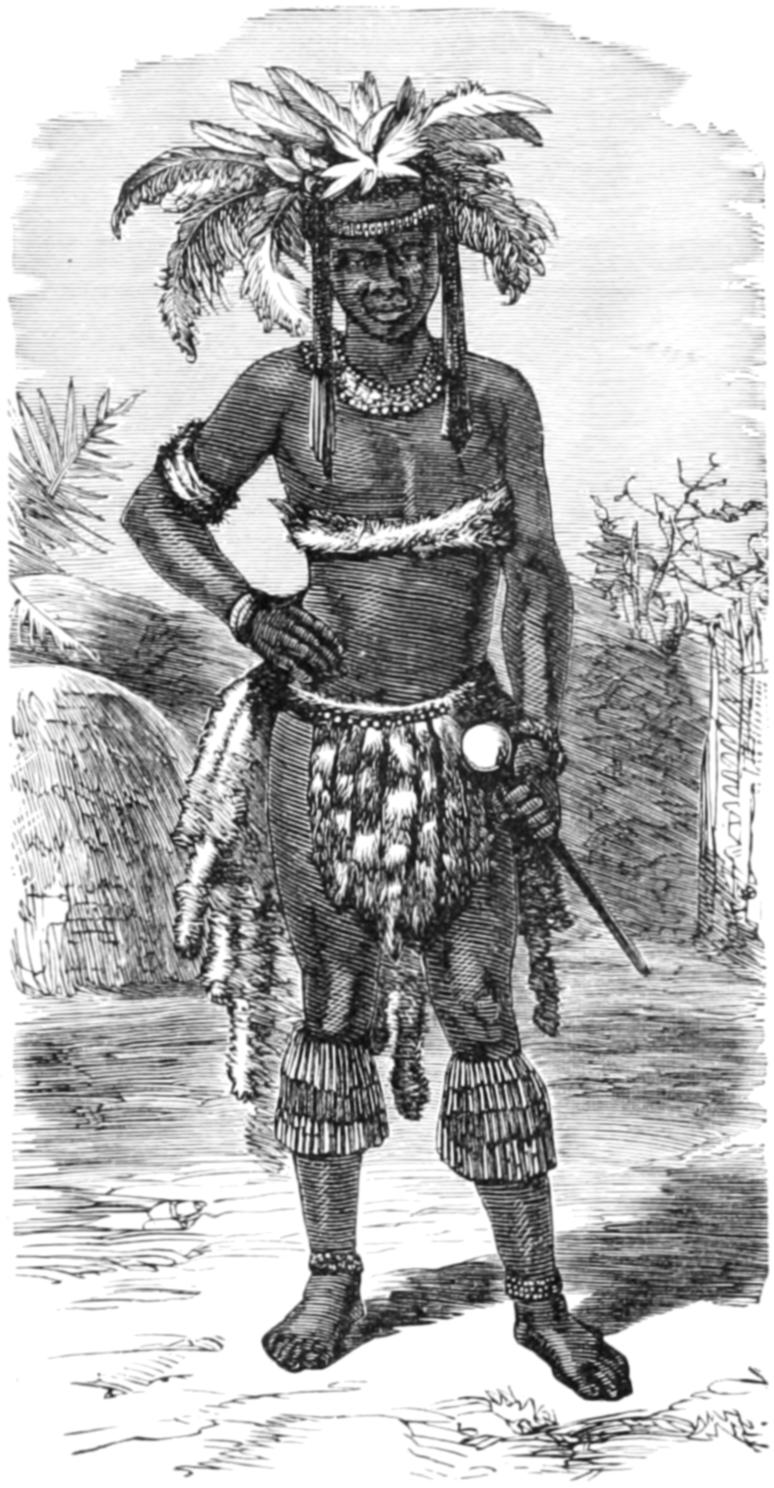

| 17. | Young Kaffir in full dress | 43 |

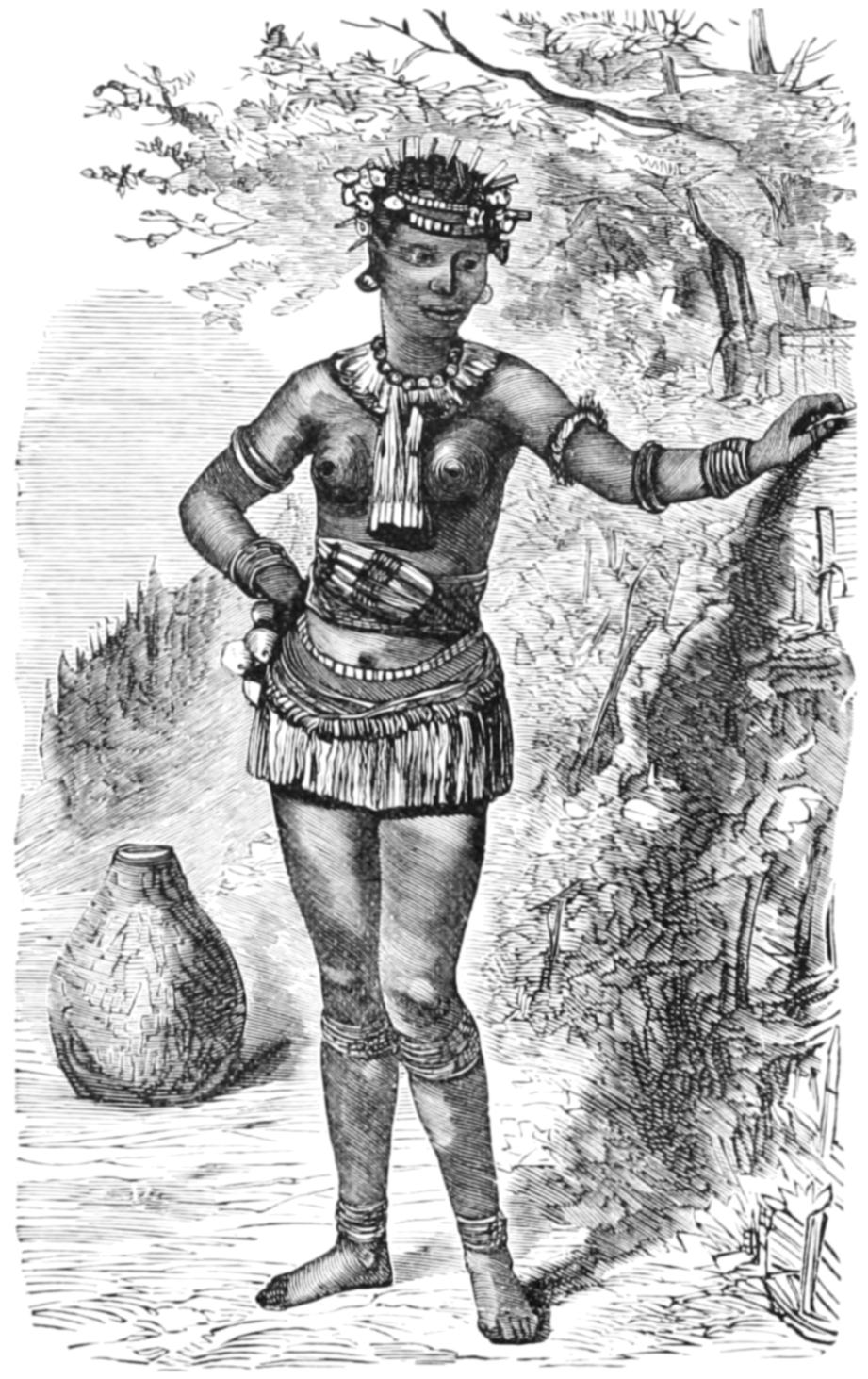

| 18. | Girl in dancing dress | 43 |

| 19. | Kaffir ornaments | 49 |

| 20. | Dress and ornaments | 49 |

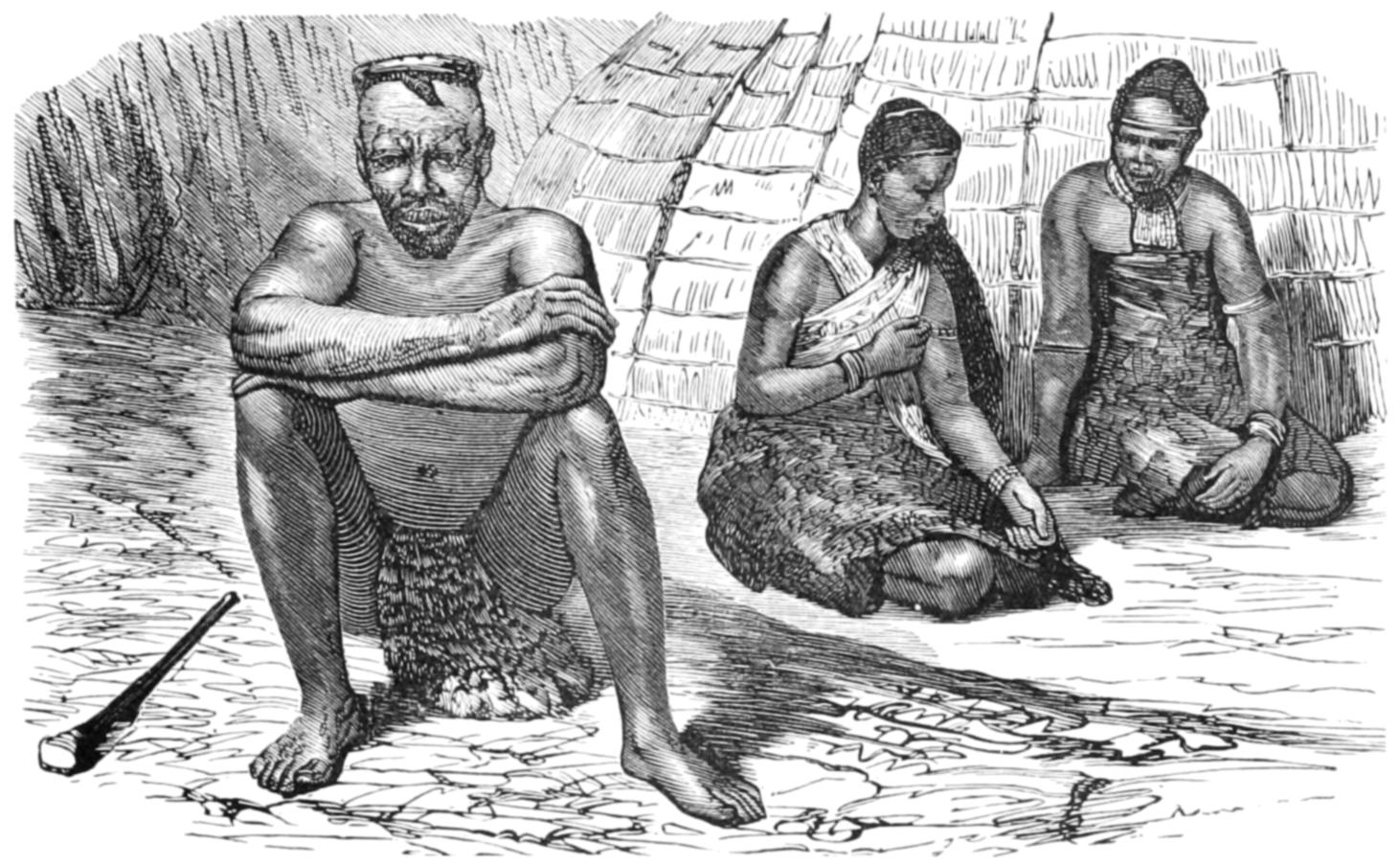

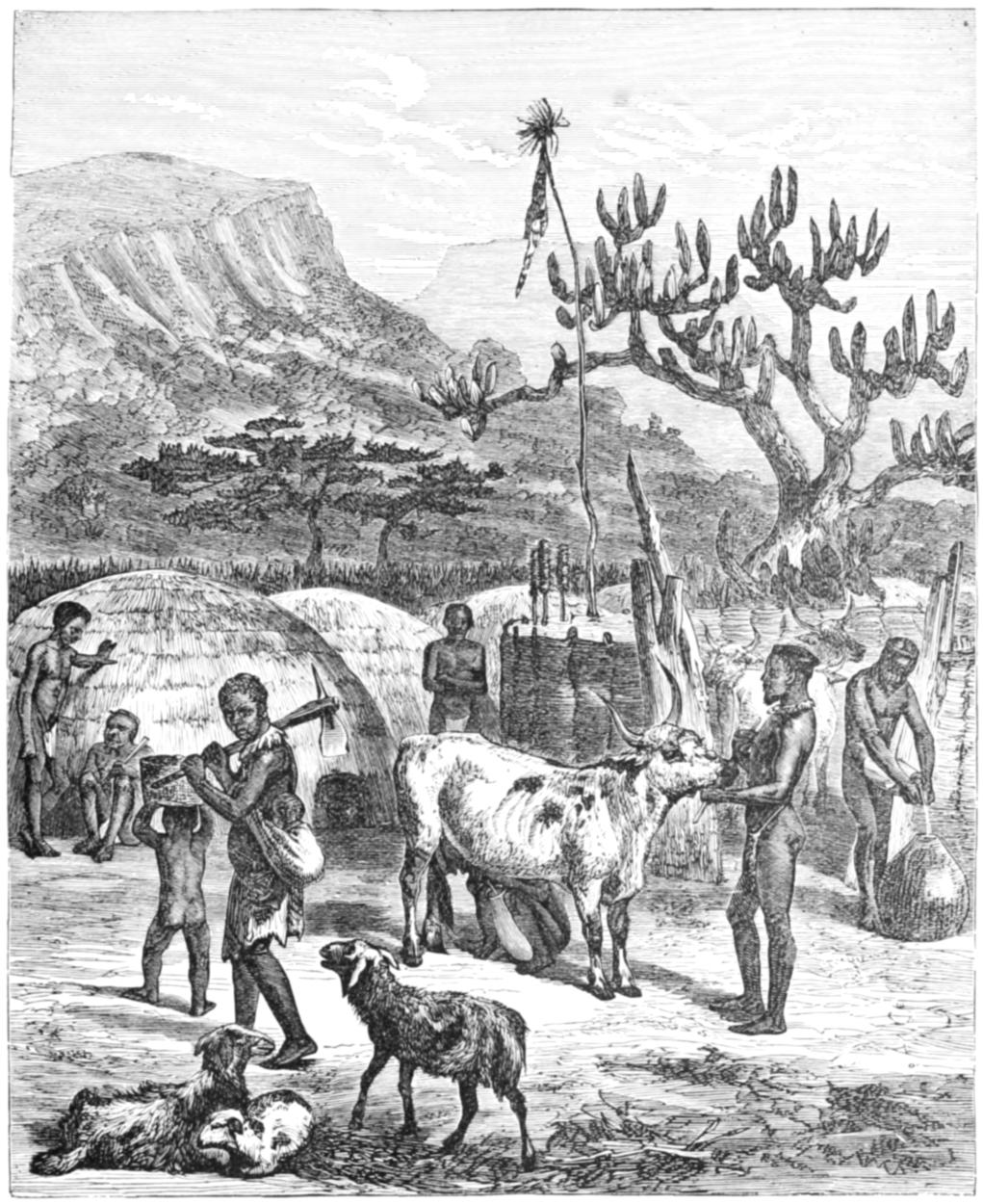

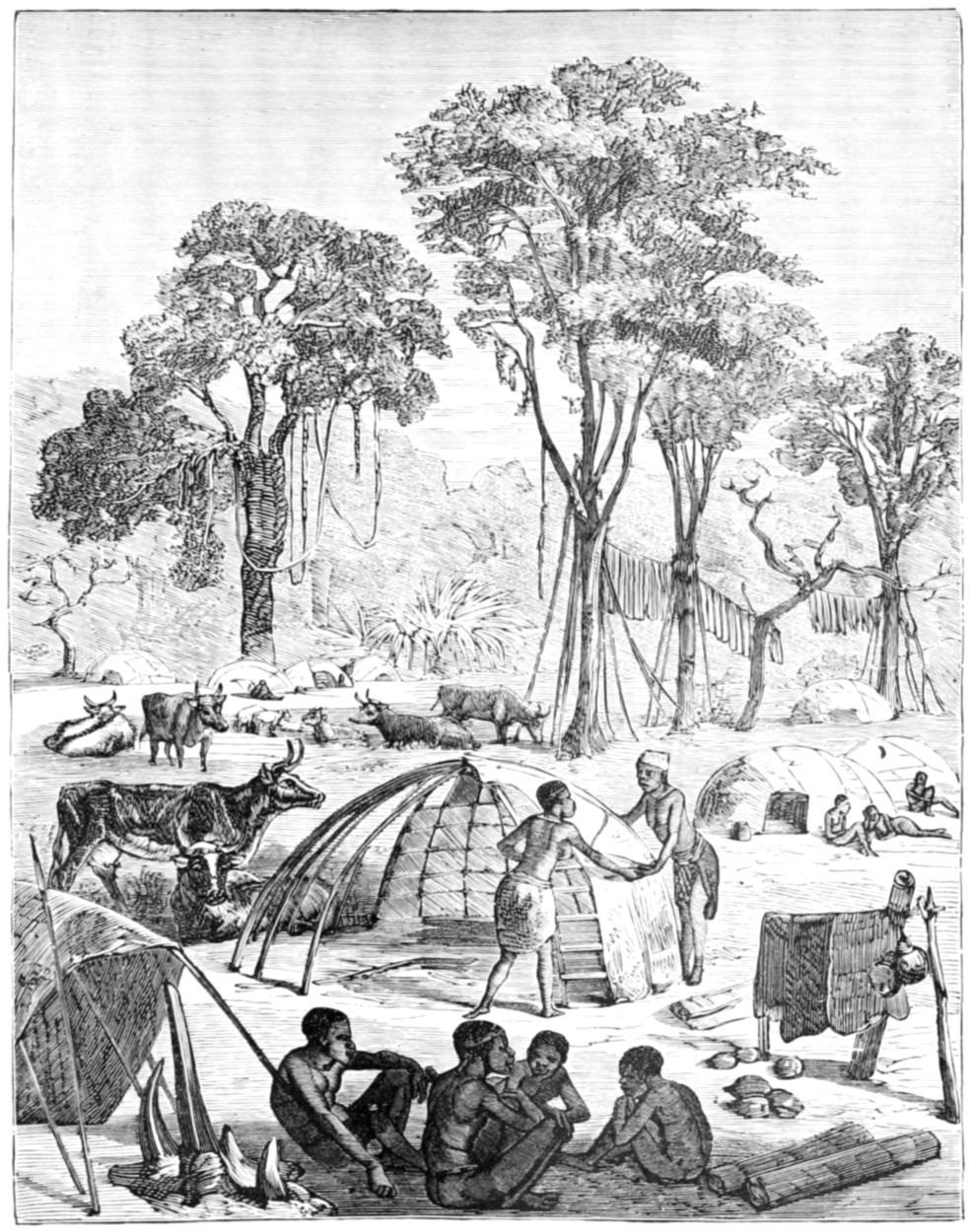

| 21. | The Kaffirs at home | 57 |

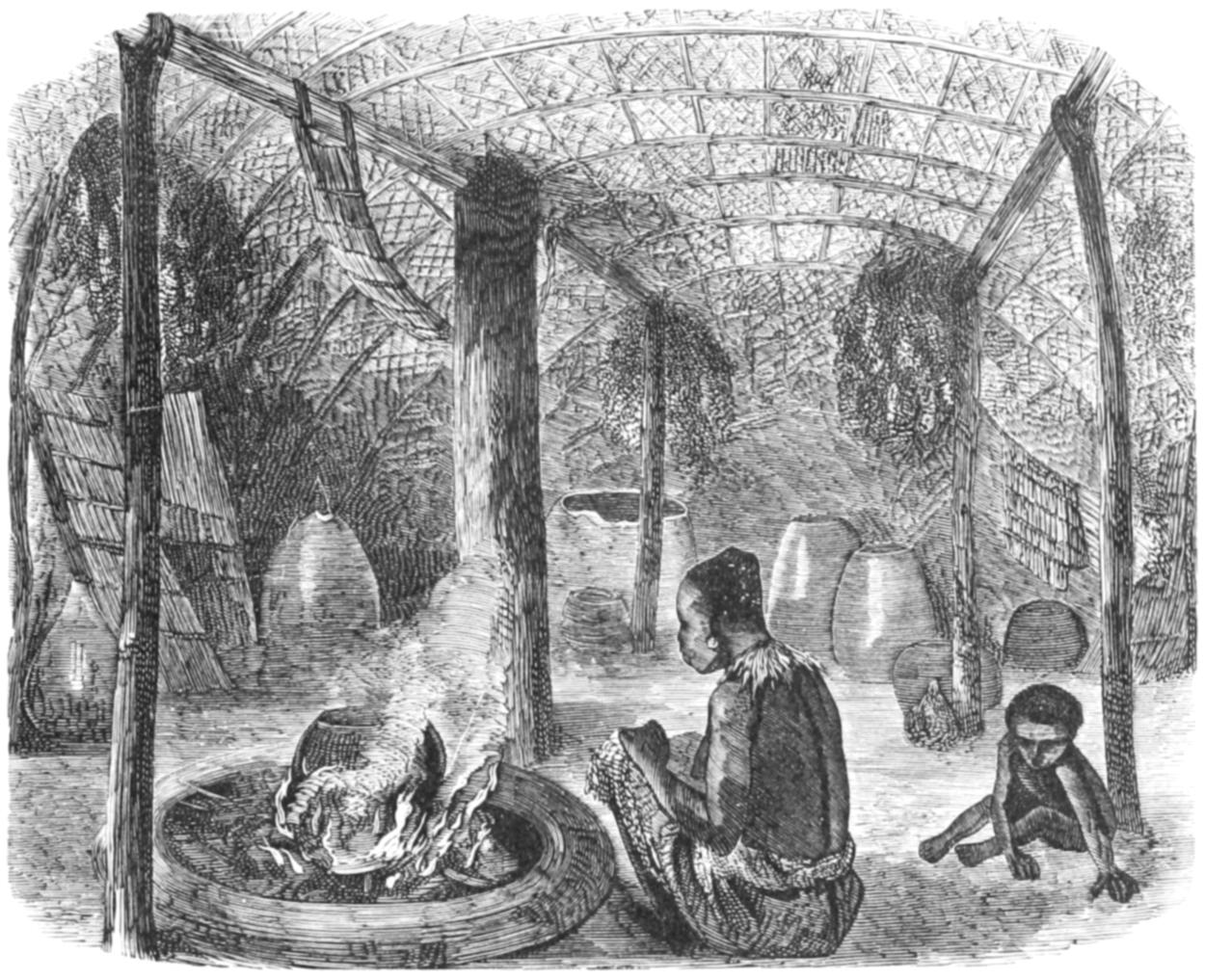

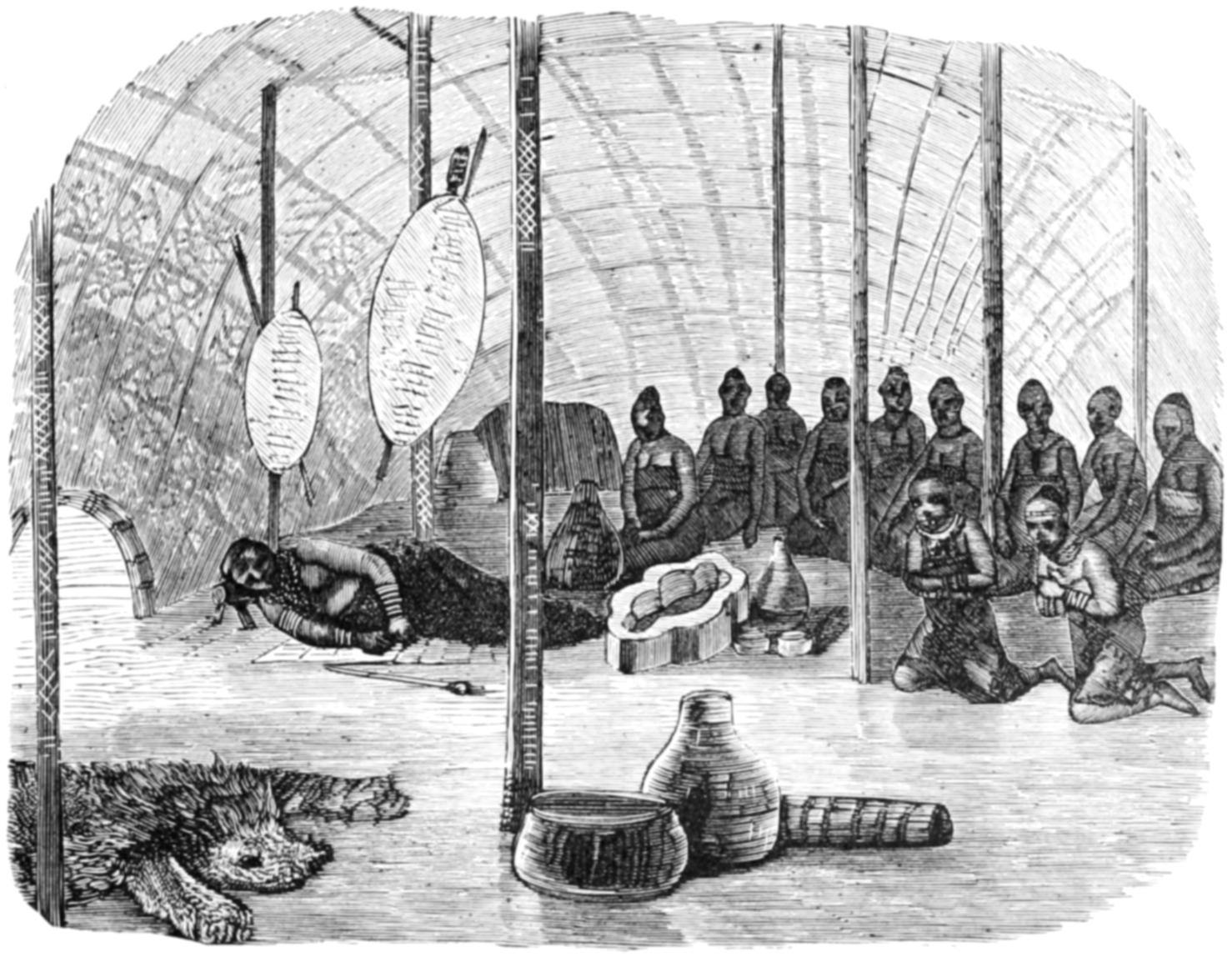

| 22. | Interior of a Kaffir hut | 63 |

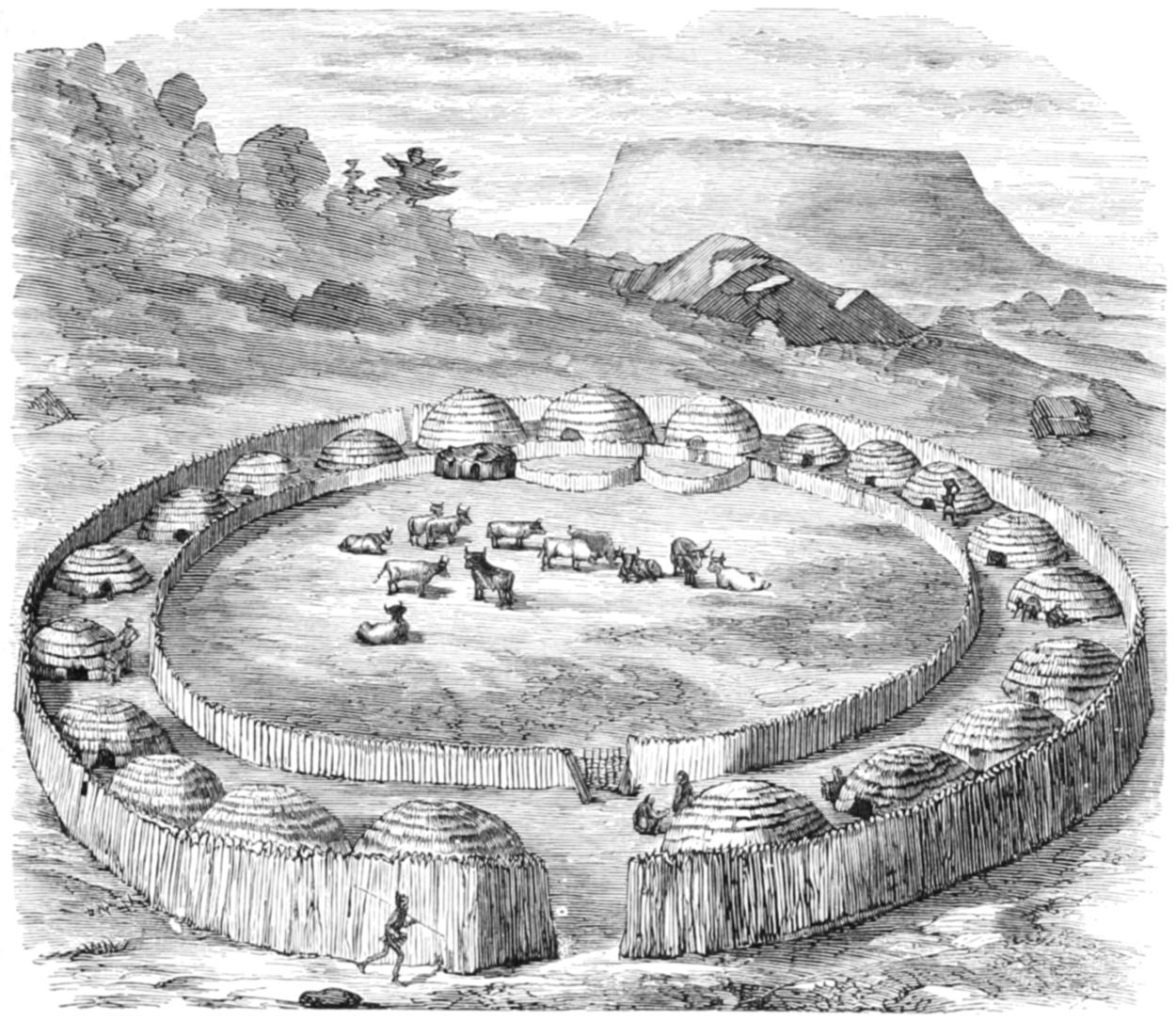

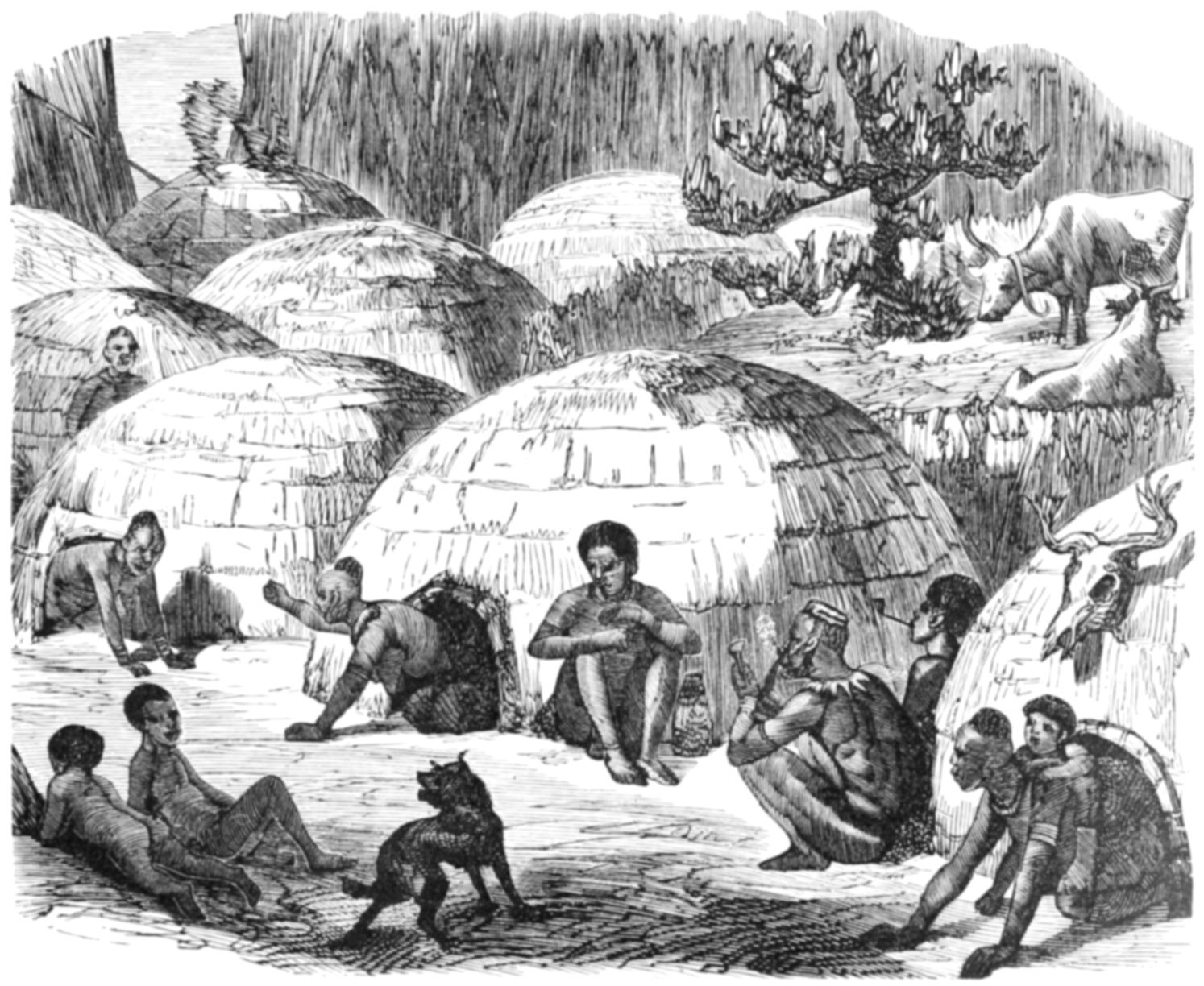

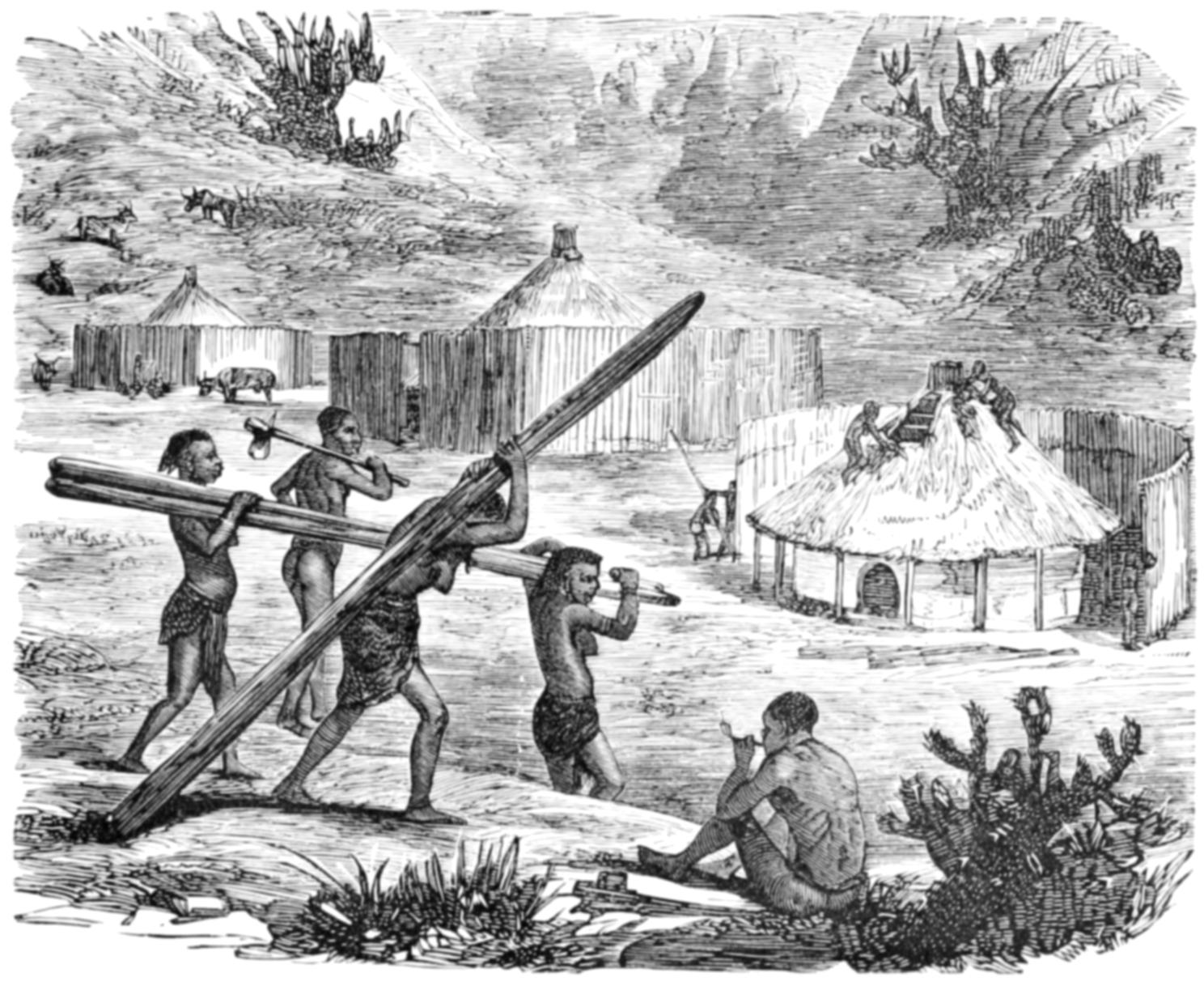

| 23. | A Kaffir kraal | 63 |

| 24. | A Kaffir milking bowl | 67 |

| 25. | A Kaffir beer bowl | 67 |

| 26. | A Kaffir beer strainer | 67 |

| 27. | A Kaffir water pipe | 67 |

| 28. | Woman’s basket | 67 |

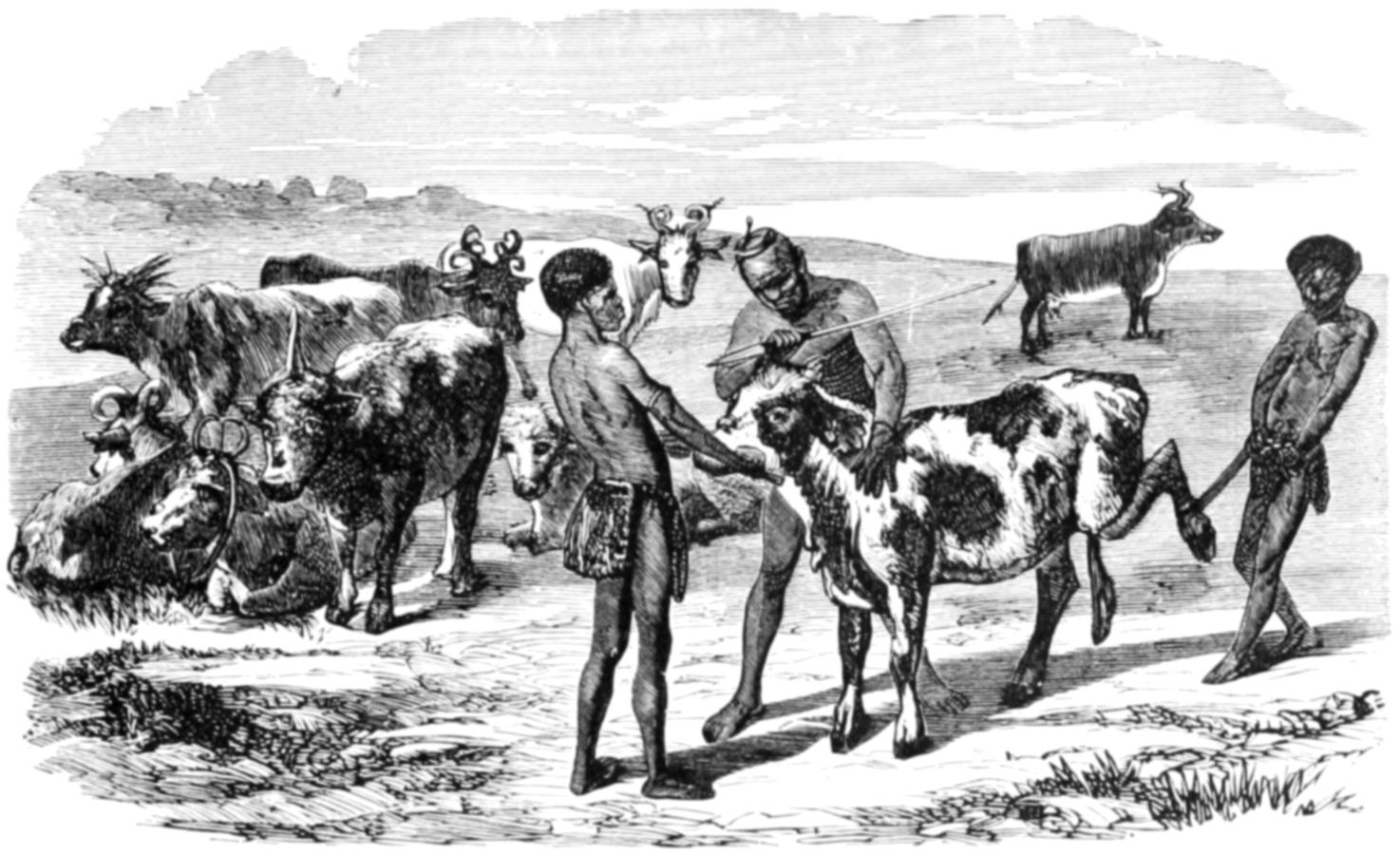

| 29. | Kaffir cattle—training the horns | 73 |

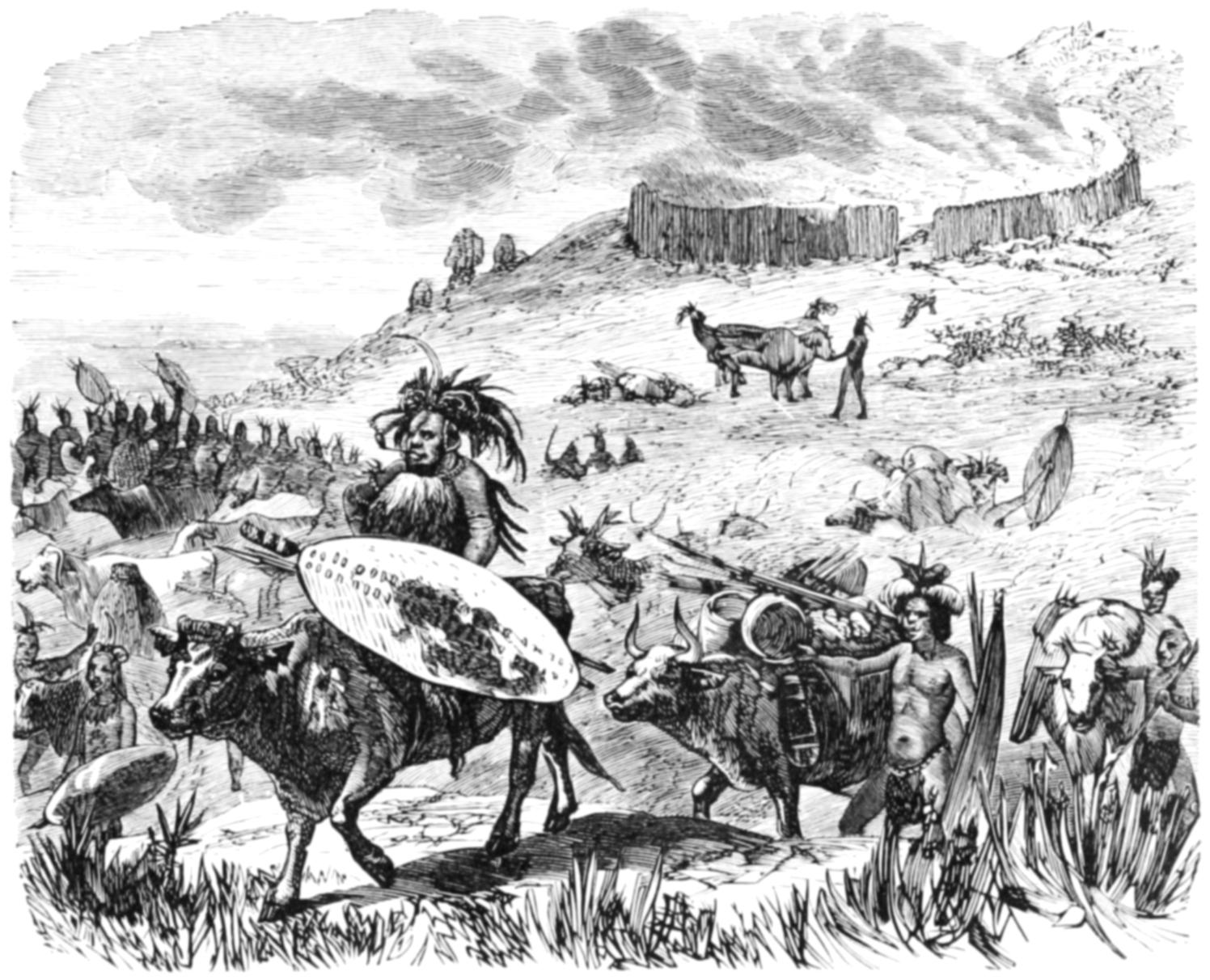

| 30. | Return of a Kaffir war party | 73 |

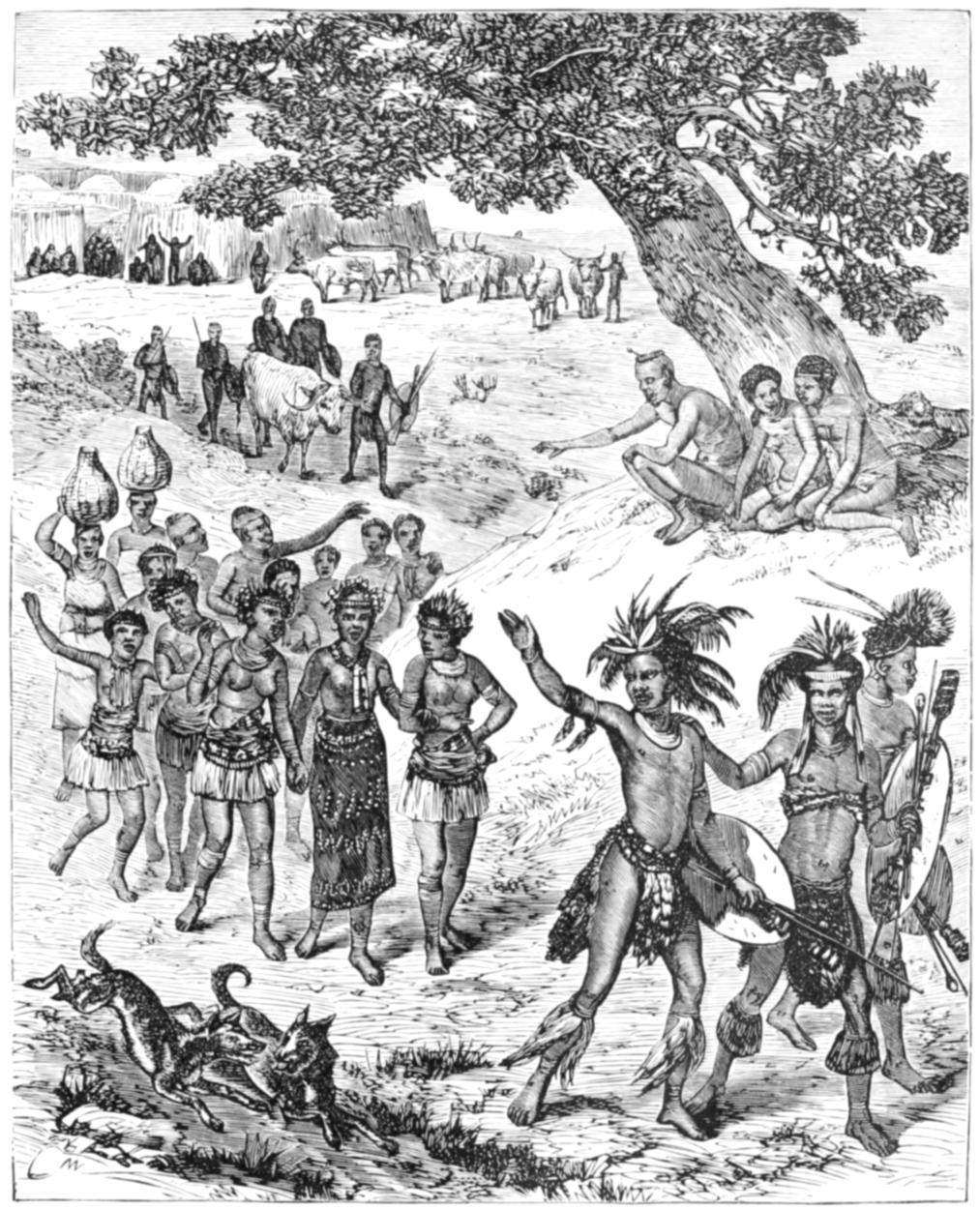

| 31. | Procession of the bride | 83 |

| 32. | Kaffir passing his mother-in-law | 88 |

| 33. | Bridegroom on approval | 97 |

| 34. | Kaffir at his forge | 97 |

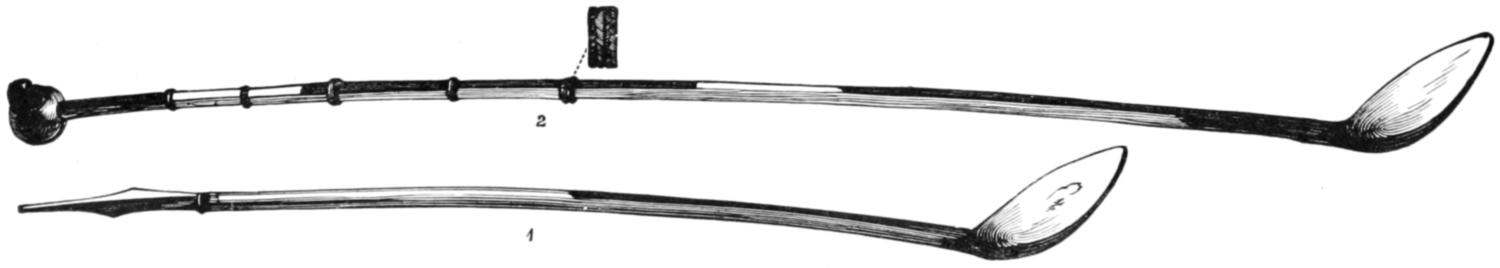

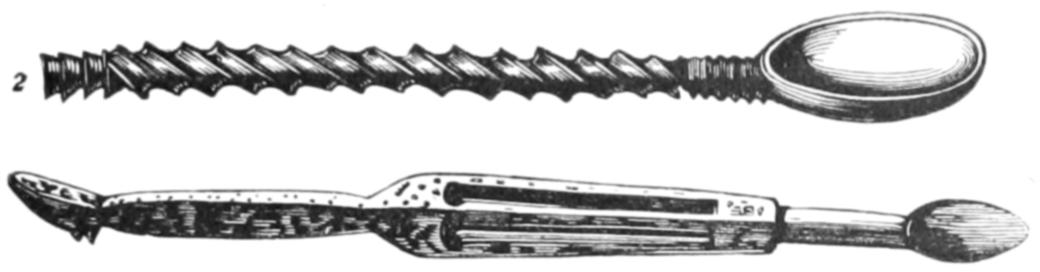

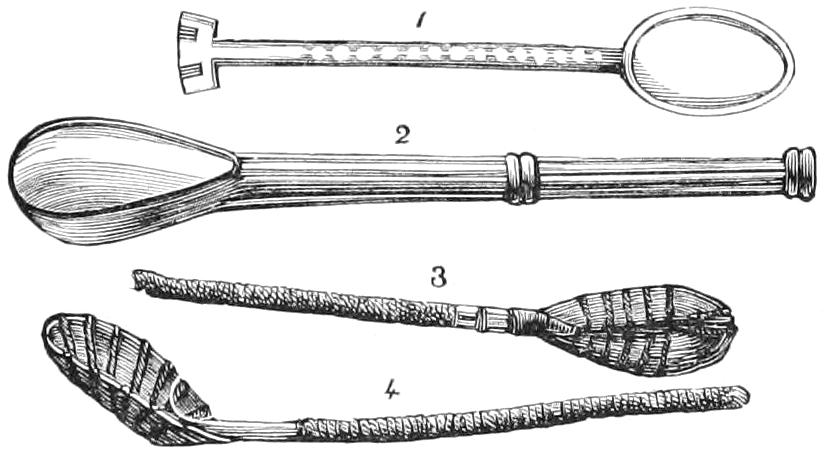

| 35. | Spoons for eating porridge | 103 |

| 36. | Group of assagais | 103 |

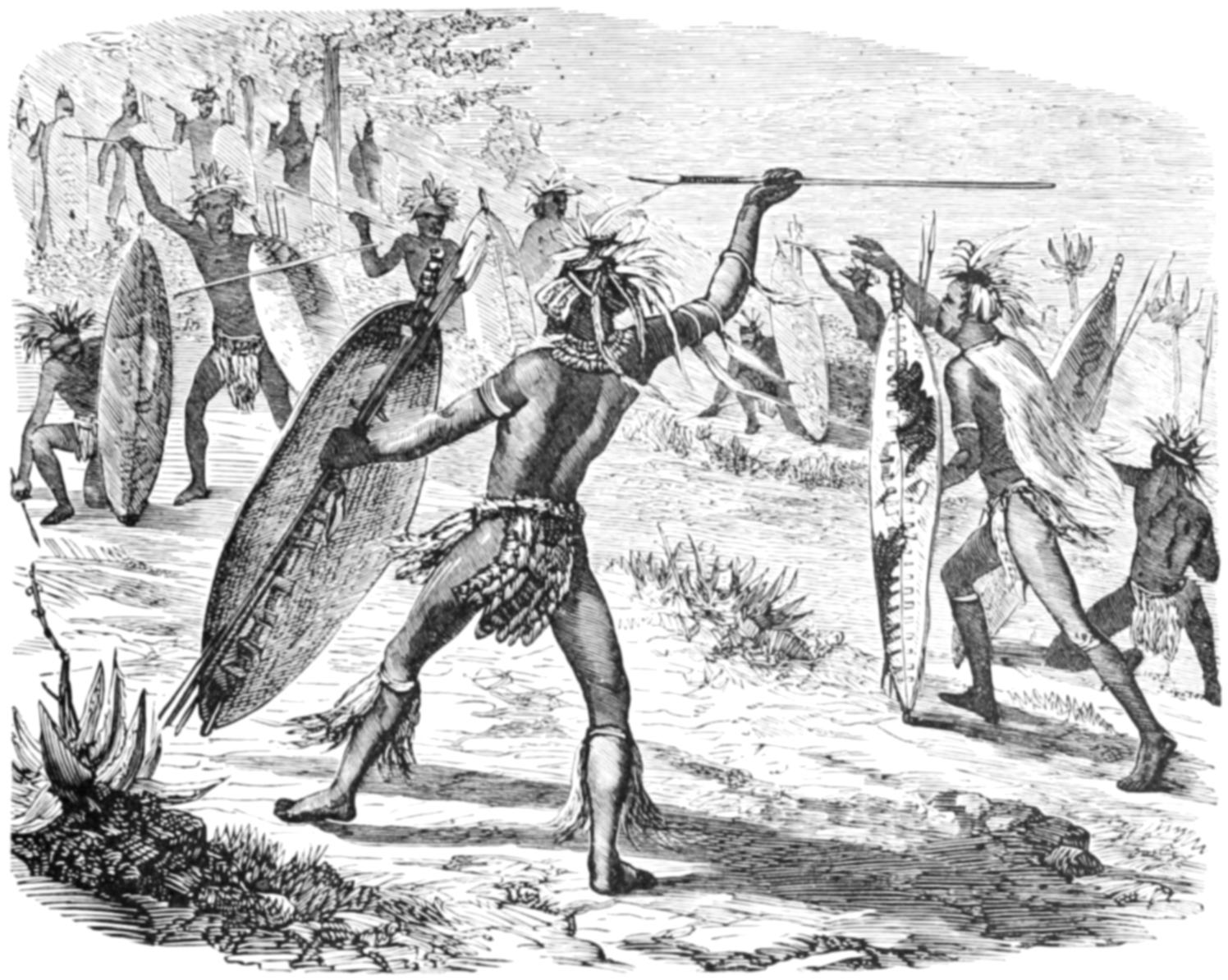

| 37. | Kaffir warriors skirmishing | 111 |

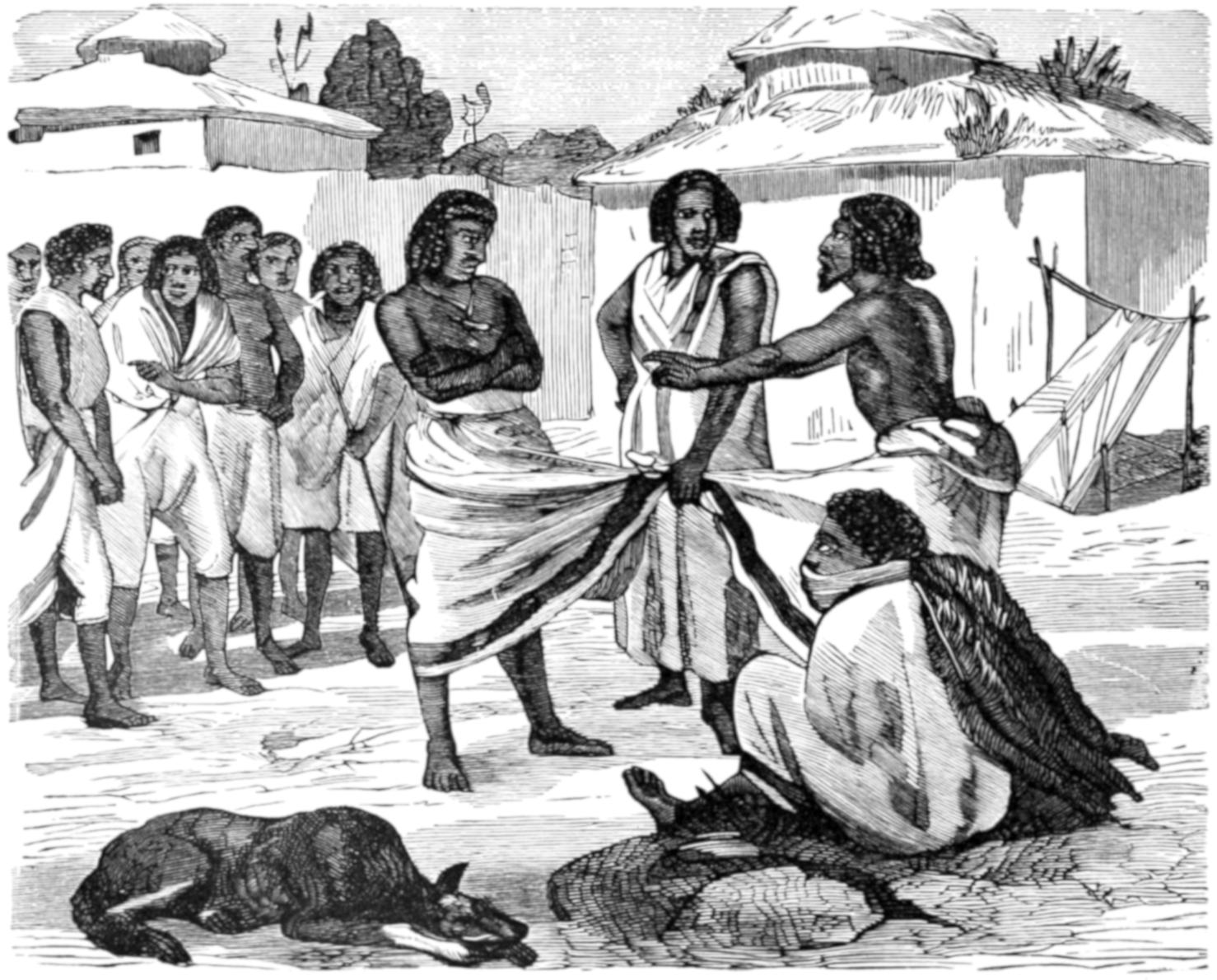

| 38. | Muscular advocacy | 111 |

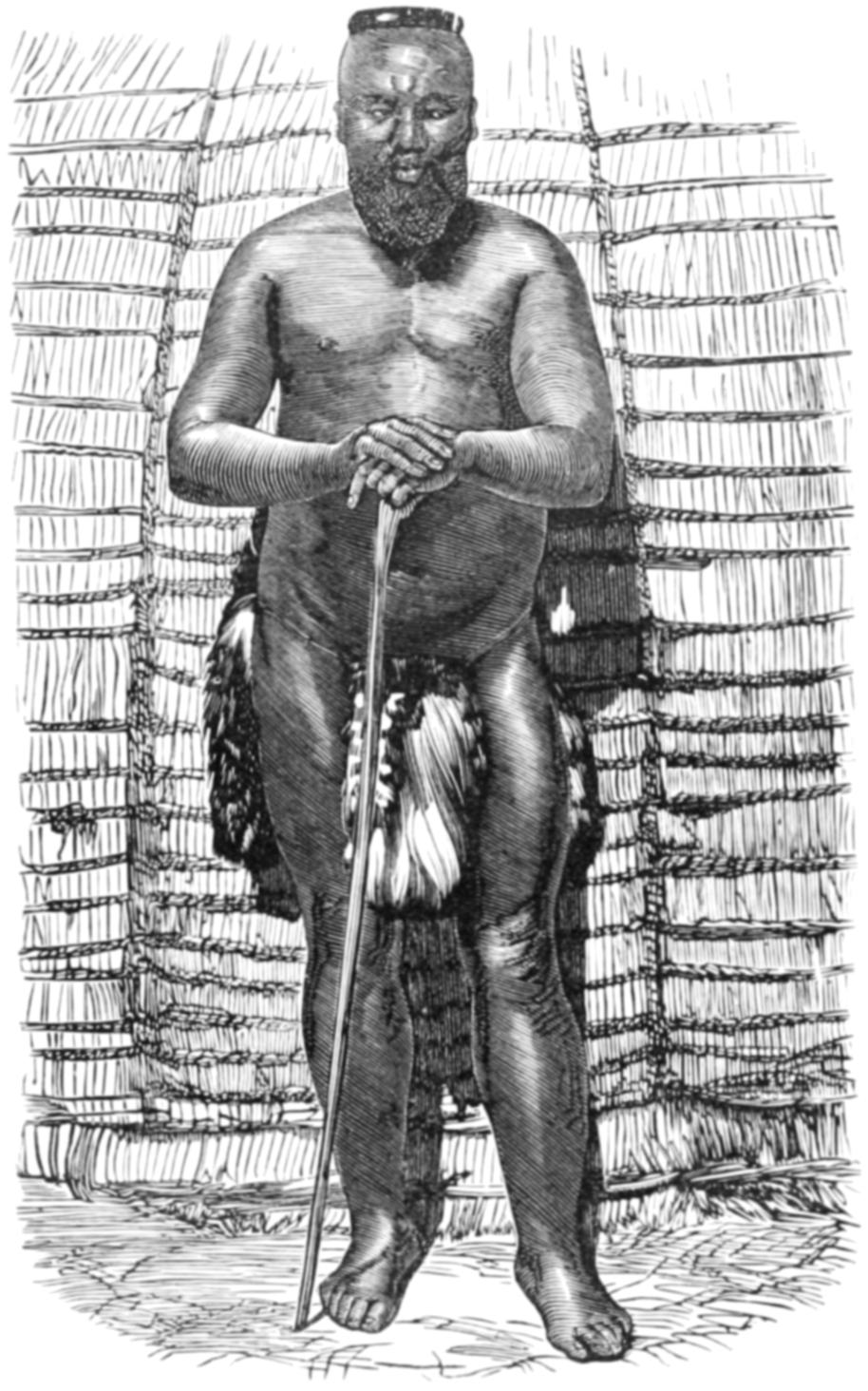

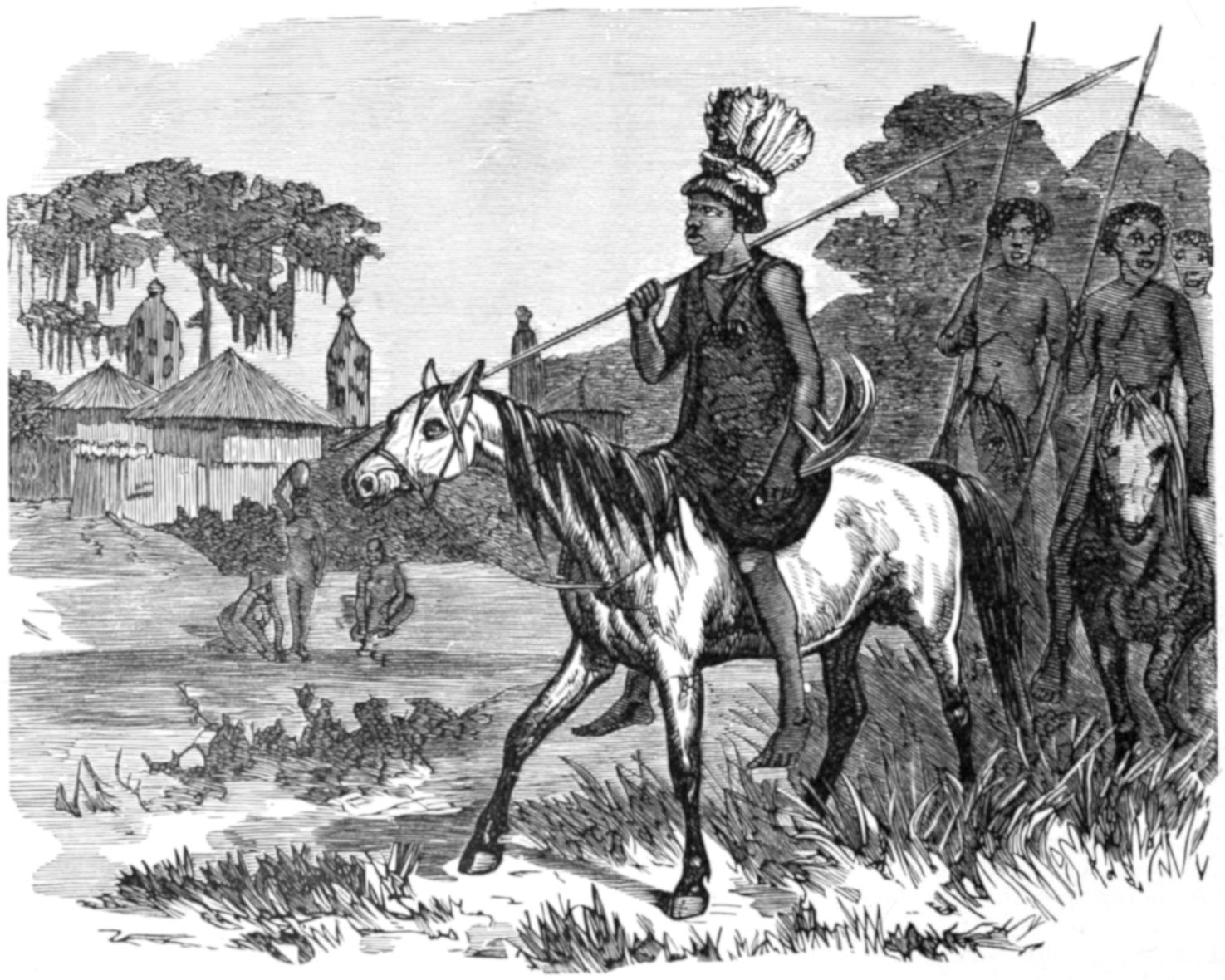

| 39. | Goza, the Kaffir chief, in ordinary undress | 117 |

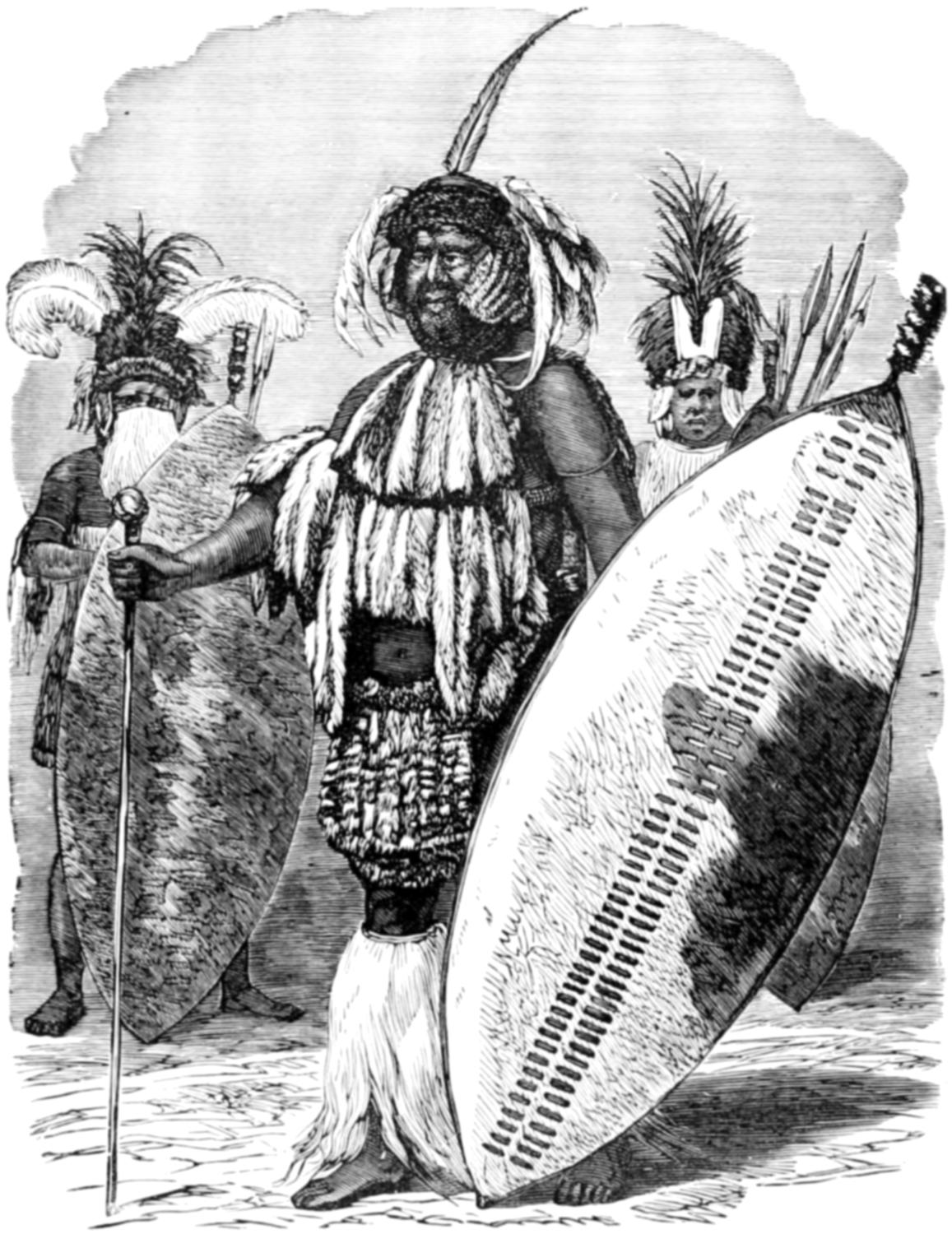

| 40. | Goza in full war dress, with his councillors | 117 |

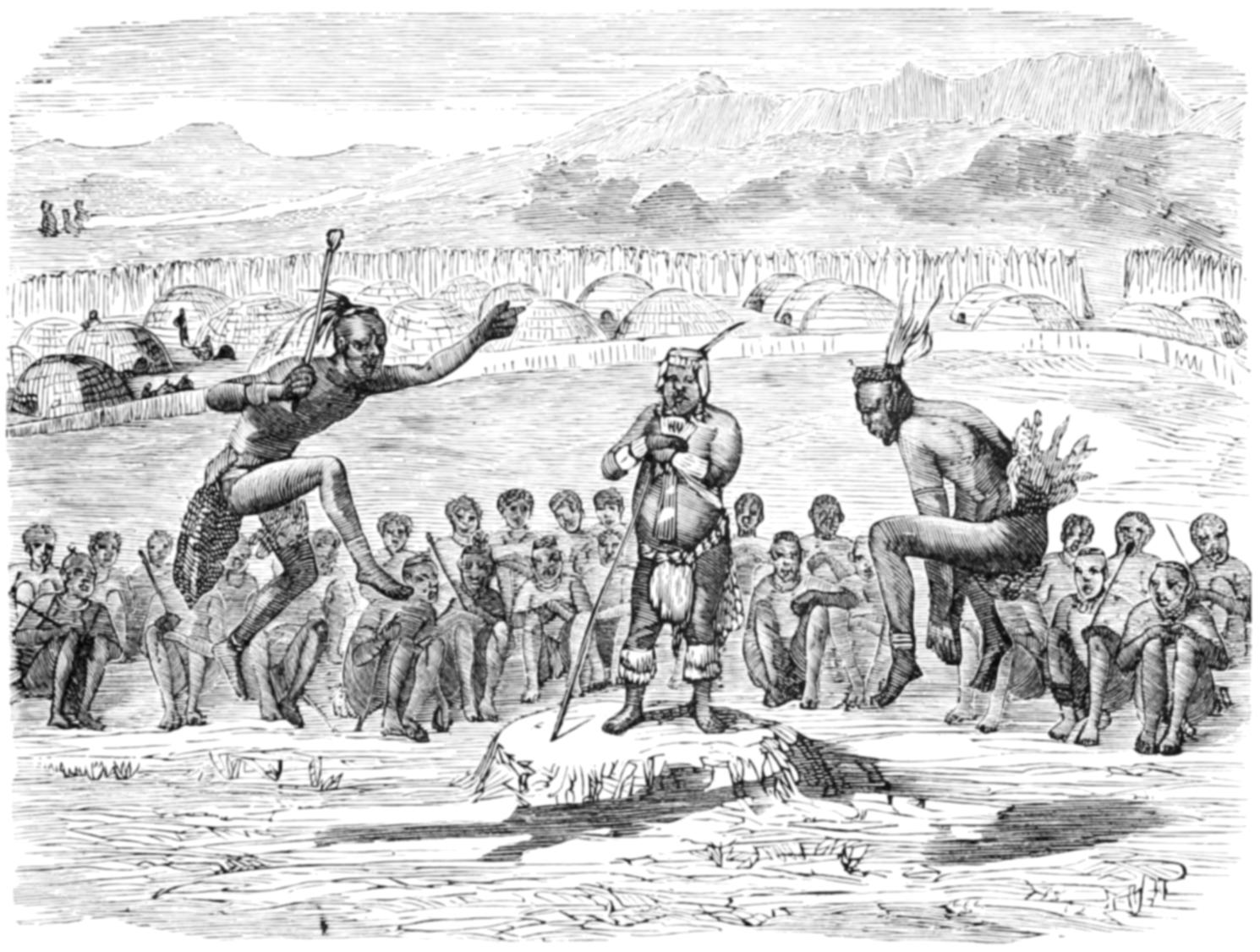

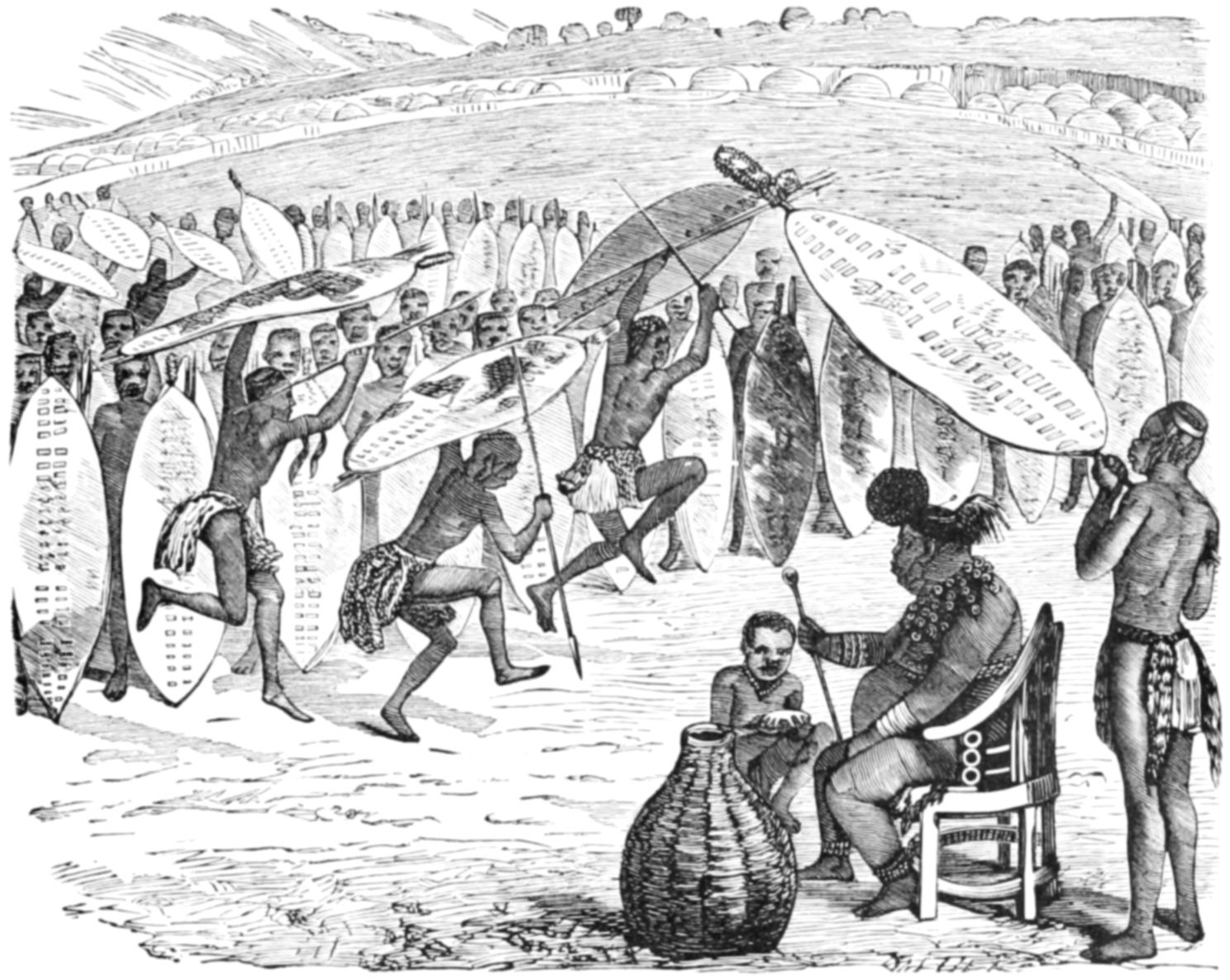

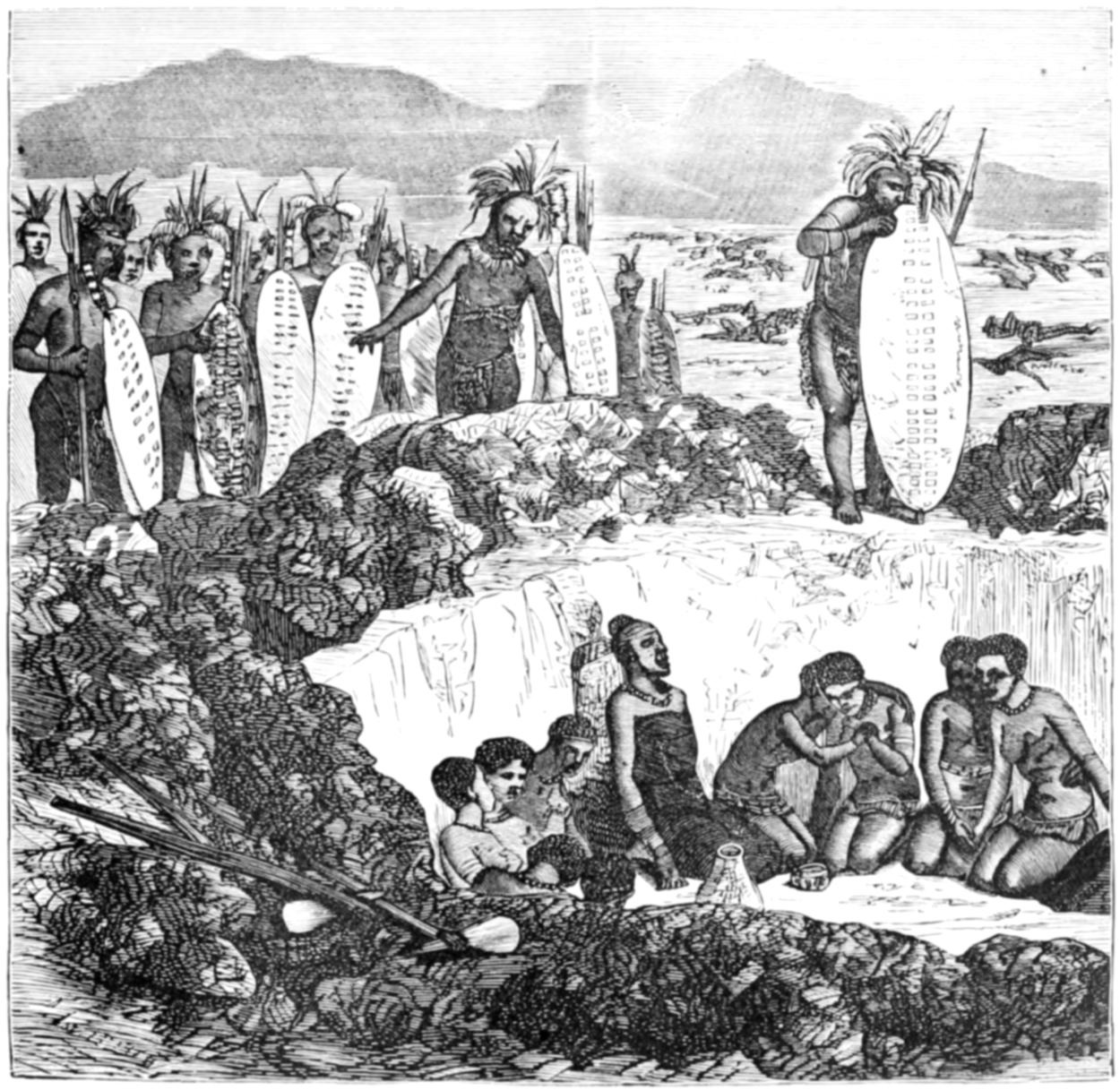

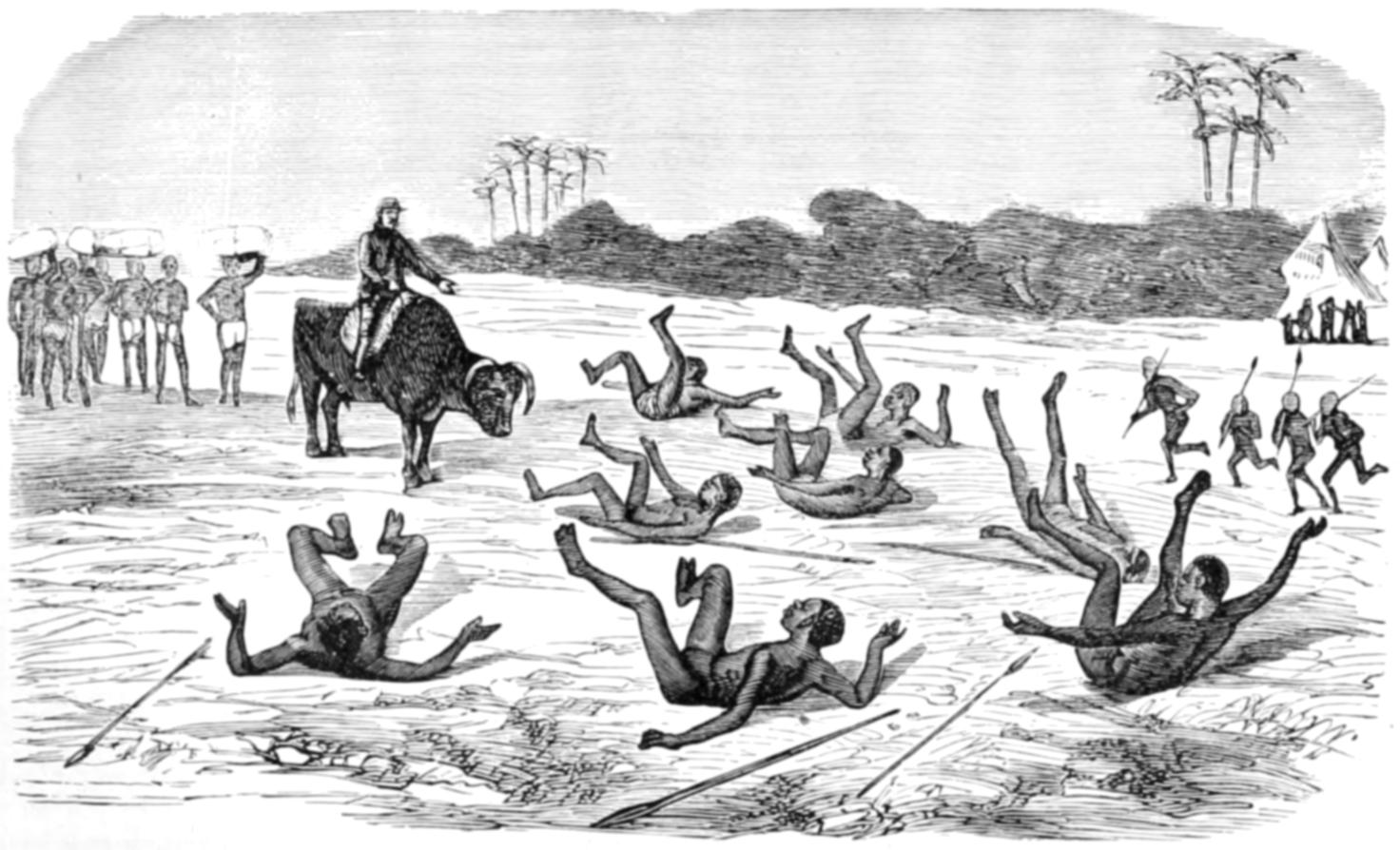

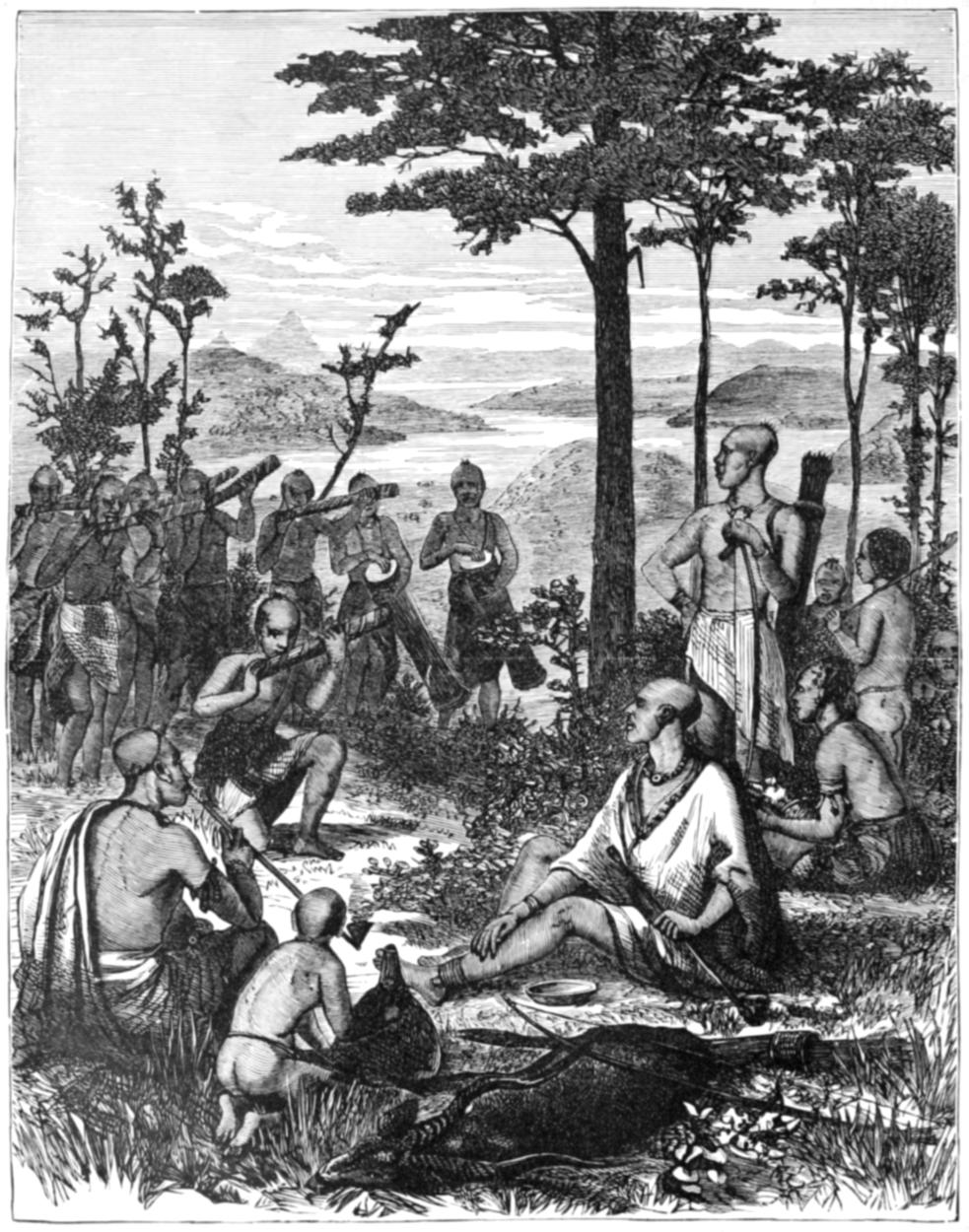

| 41. | Panda’s review | 121 |

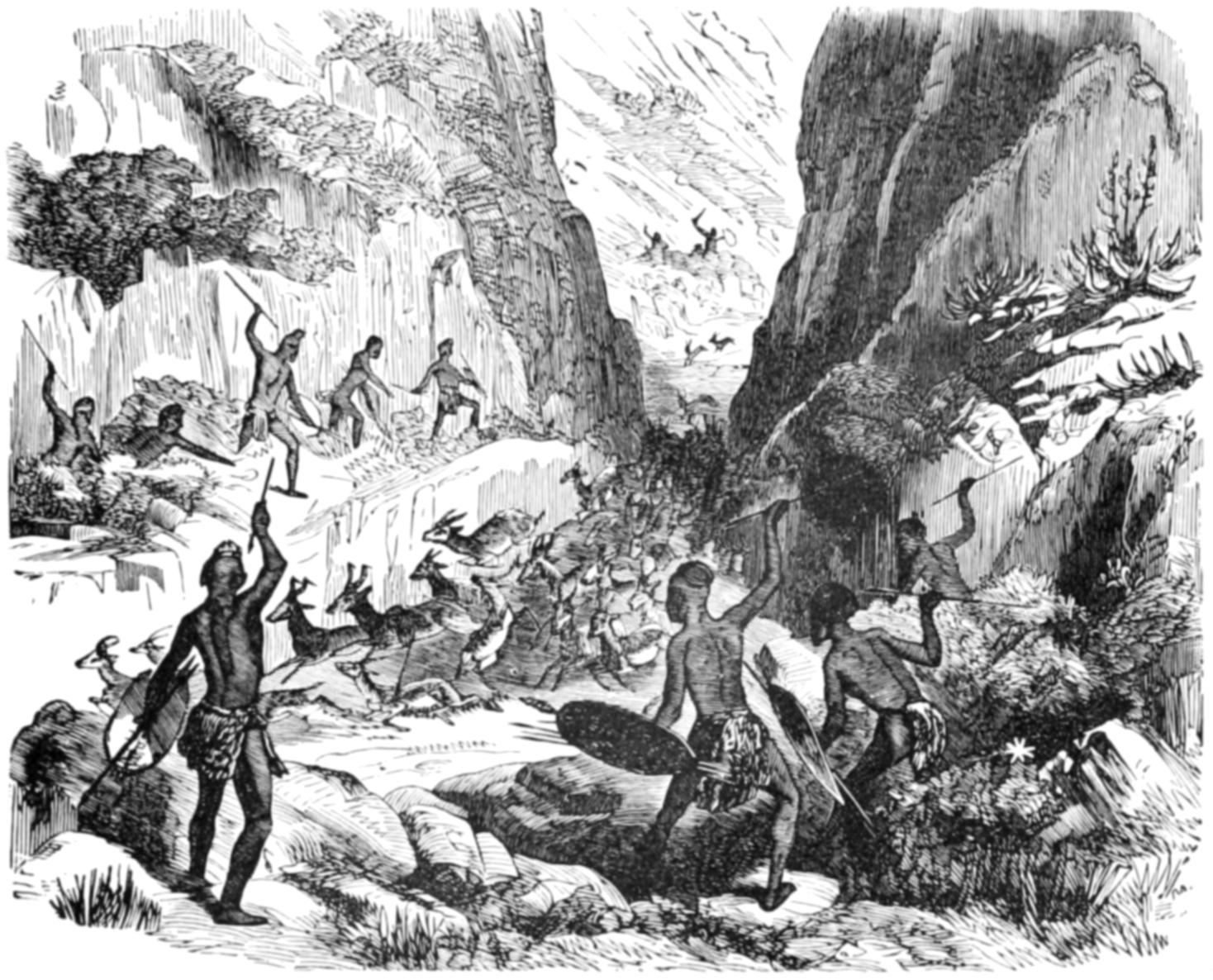

| 42. | Hunting scene in Kaffirland | 121 |

| 43. | Cooking elephant’s foot | 133 |

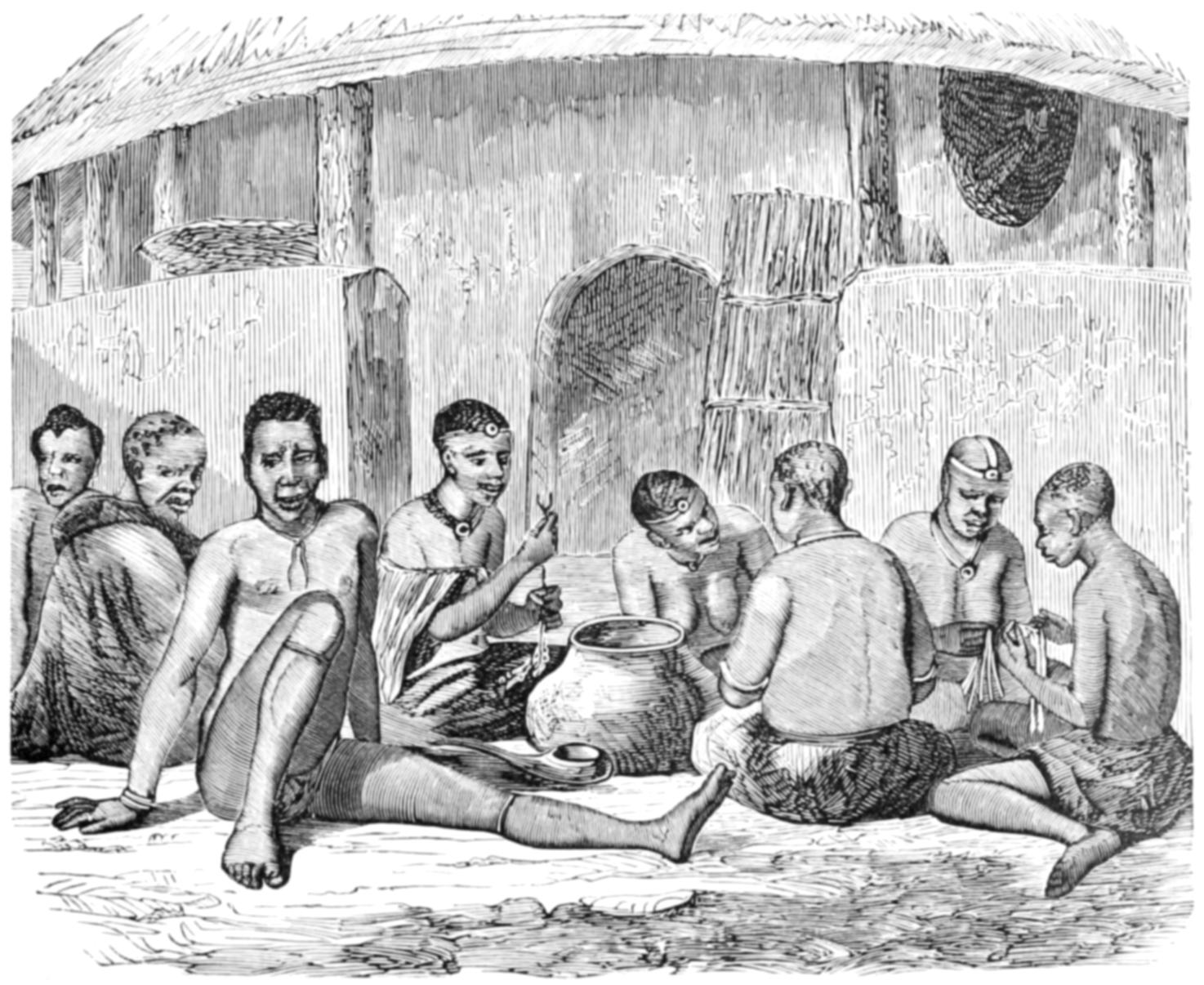

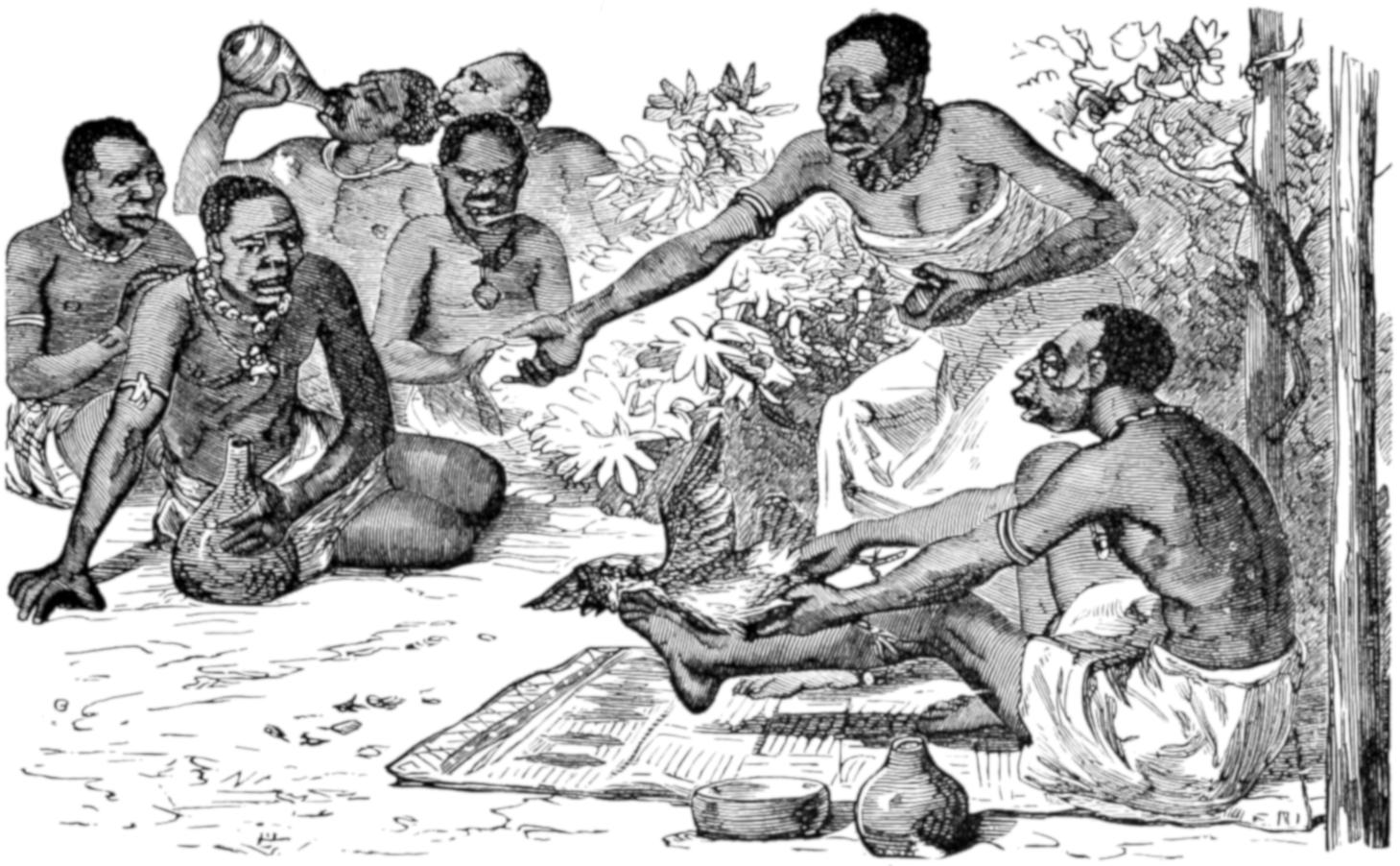

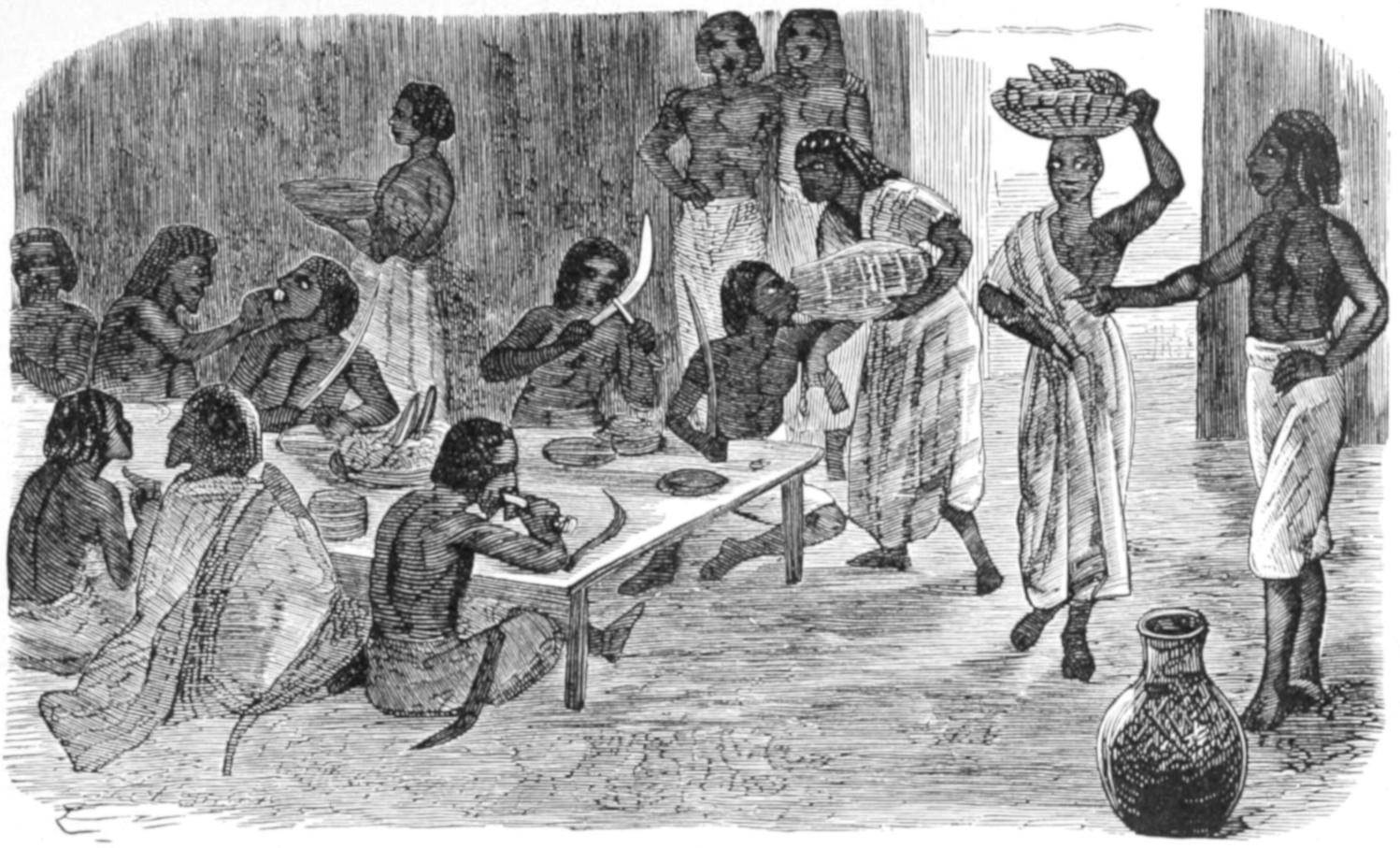

| 44. | A Kaffir dinner party | 145 |

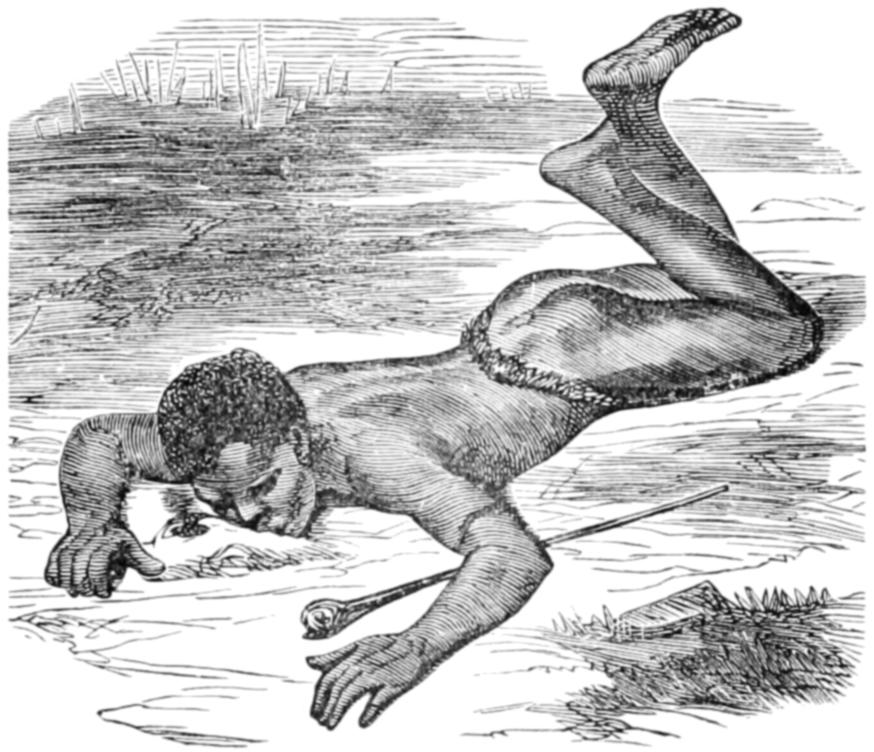

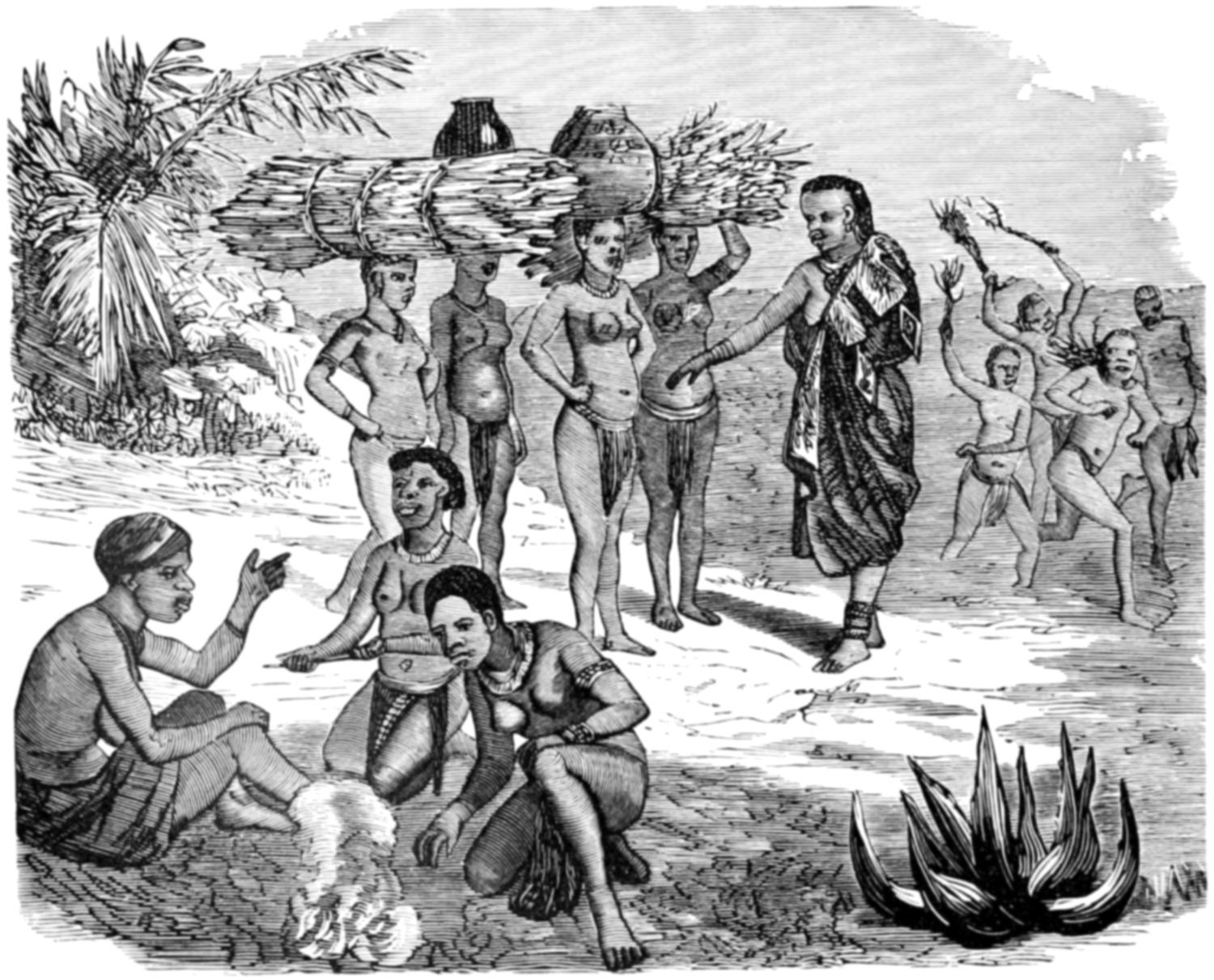

| 45. | Soldiers lapping water | 145 |

| 46. | A Kaffir harp | 155 |

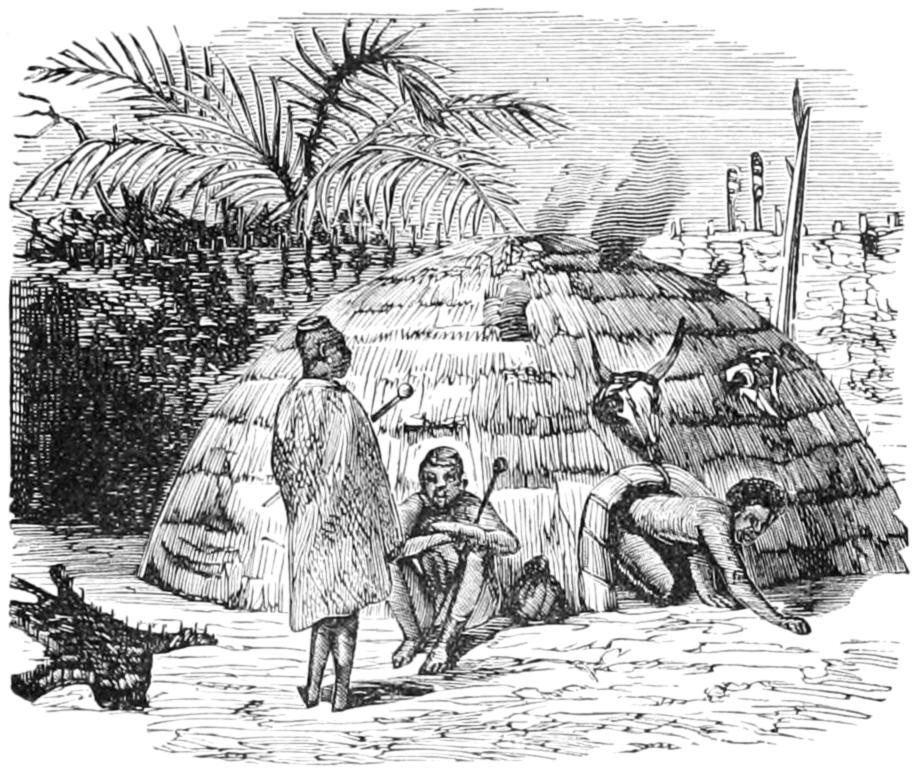

| 47. | Exterior of a Kaffir hut | 155 |

| 48. | Spoon, ladle, skimmers | 155 |

| 49. | A Kaffir water pipe | 155 |

| 50. | A Kaffir fowl house | 155 |

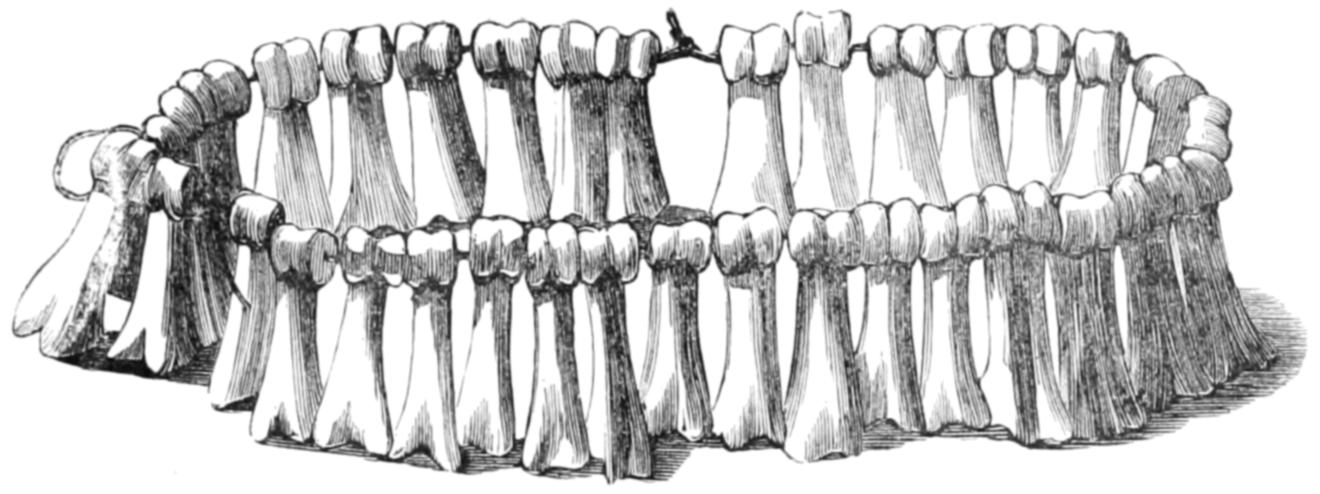

| 51. | Necklace made of human finger bones | 167 |

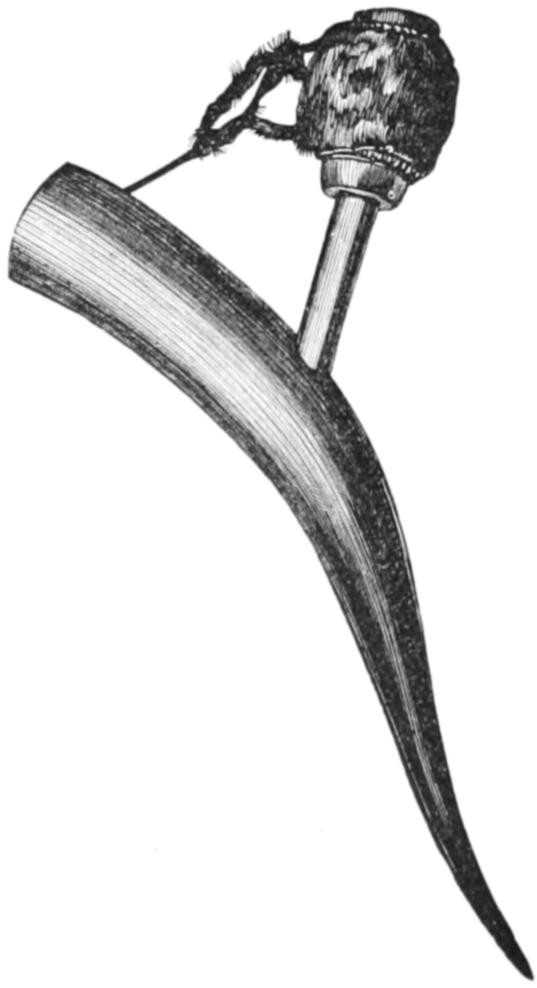

| 52. | A remarkable gourd snuff-box | 167 |

| 53. | Poor man’s pipe | 167 |

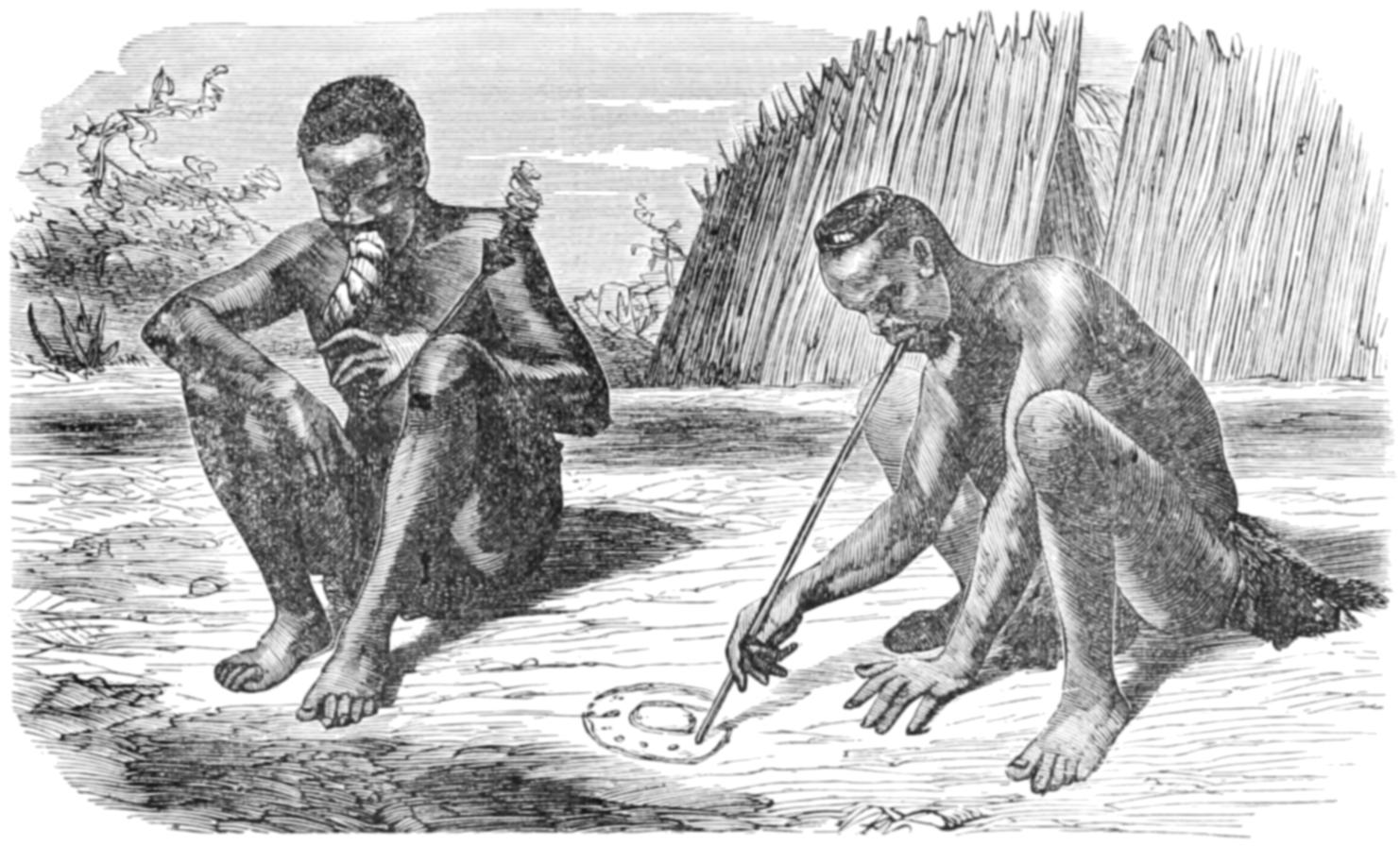

| 54. | Kaffir gentlemen smoking | 167 |

| 55. | The prophet’s school | 174 |

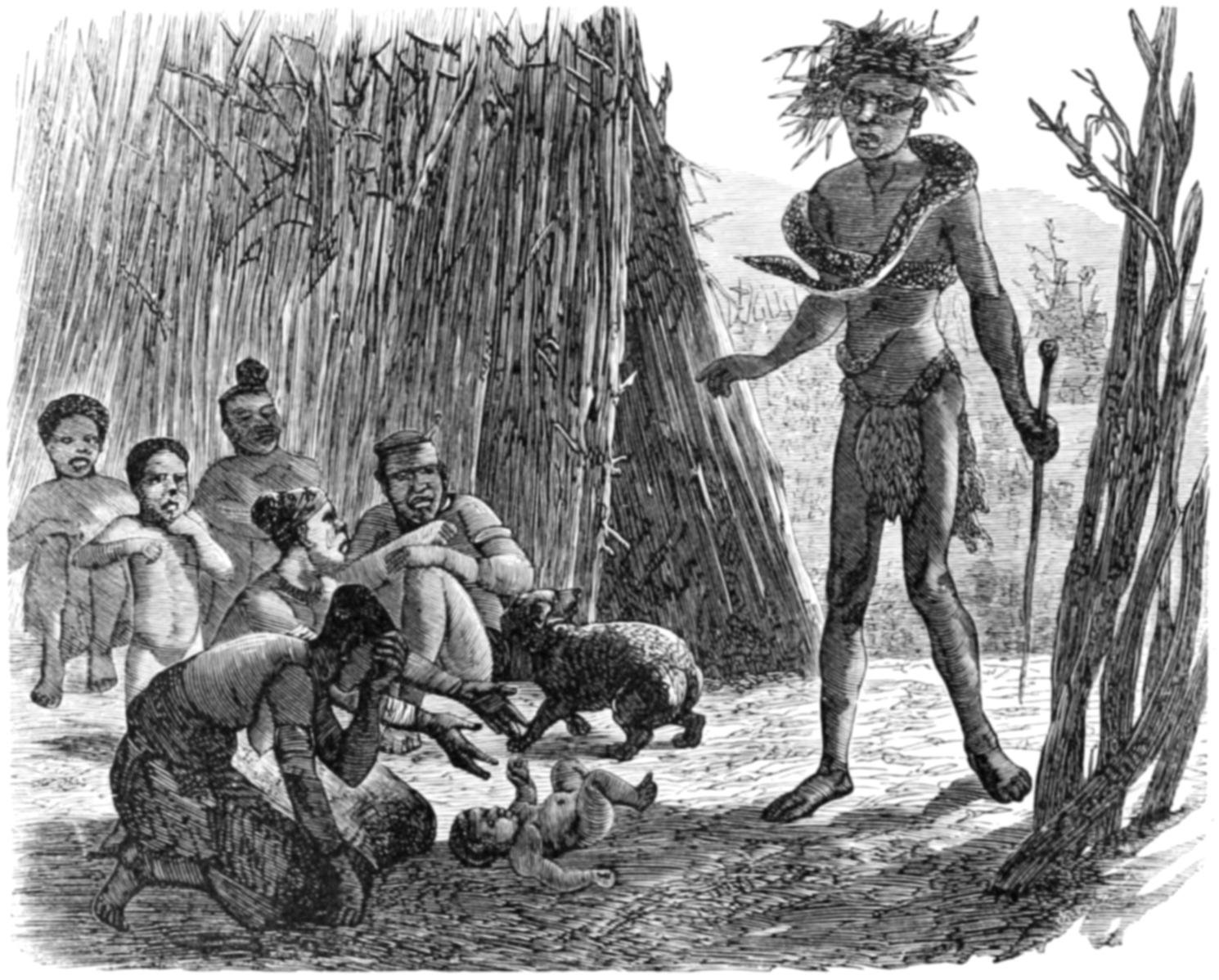

| 56. | The prophet’s return | 174 |

| 57. | Old Kaffir prophets | 177 |

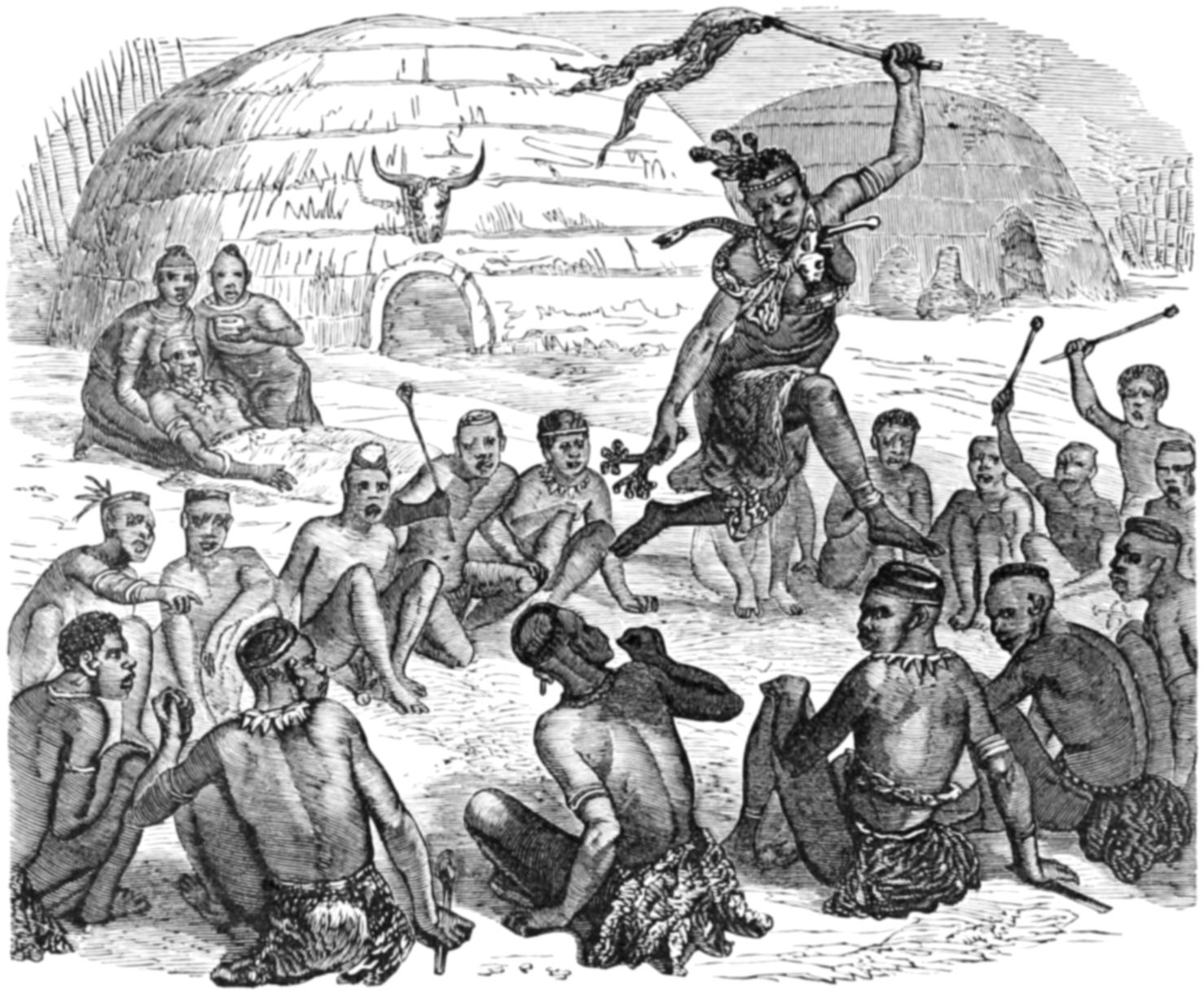

| 58. | The Kaffir prophetess at work | 188 |

| 59. | Unfavorable prophecy | 188 |

| 60. | Preserved head | 203 |

| 61. | Head of Mundurucú chief | 203 |

| 62. | Burial of King Tchaka’s mother | 203 |

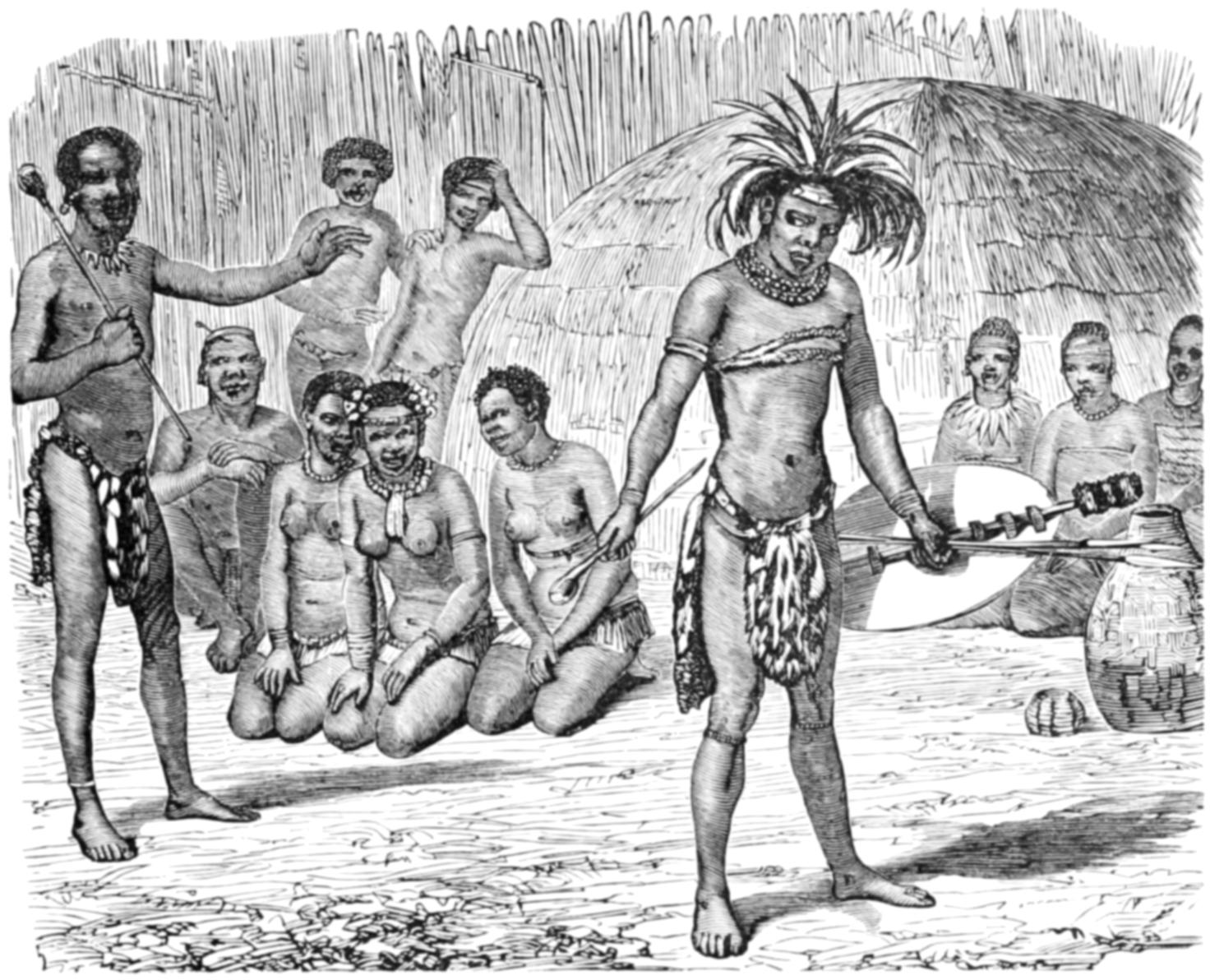

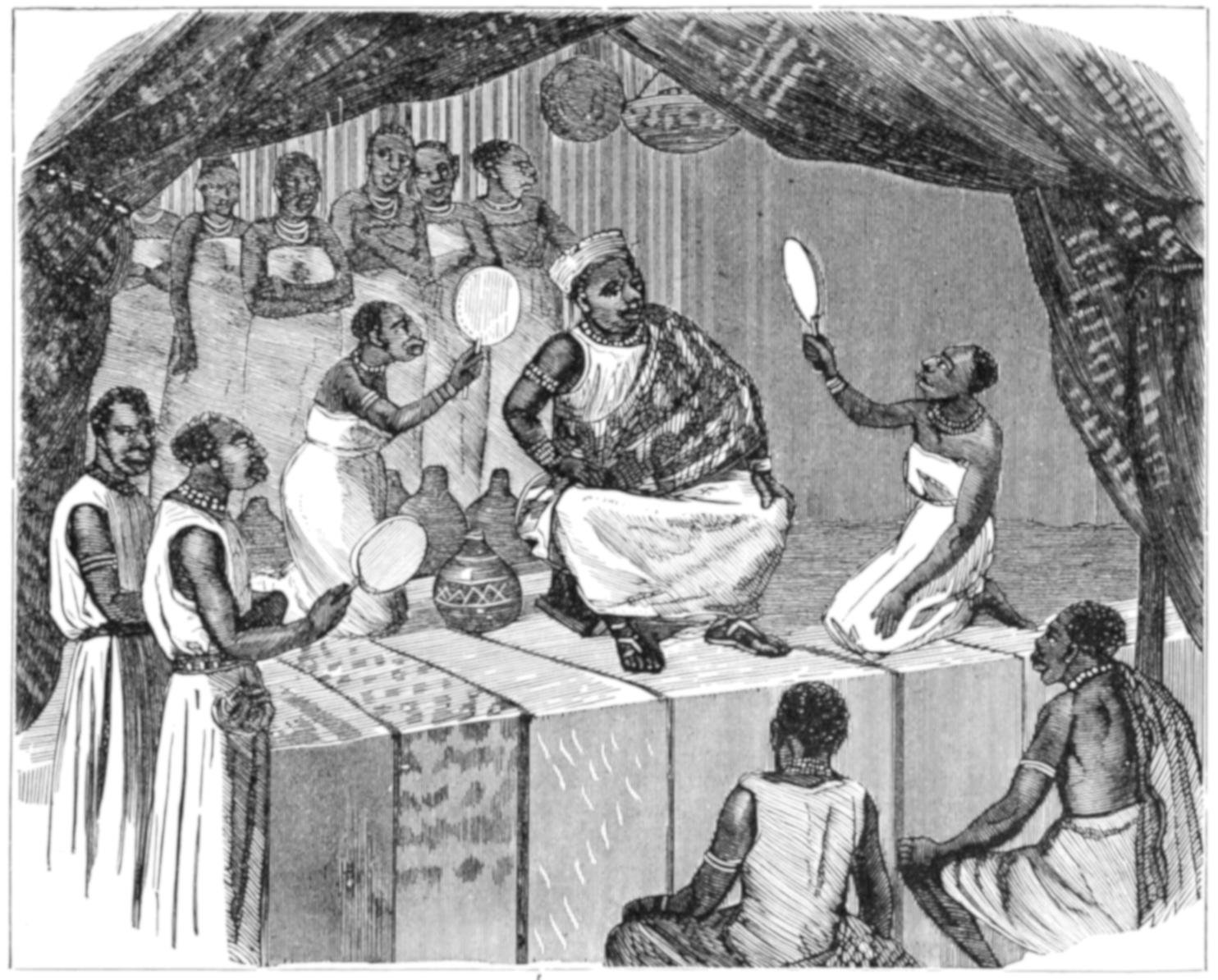

| 63. | Dingan, the Kaffir monarch, at home | 209 |

| 64. | Kaffir women quarrelling | 209 |

| 65. | Hottentot girl | 219 |

| 66. | Hottentot woman | 219 |

| 67. | Hottentot young man | 223 |

| 68. | Hottentot in full dress | 223 |

| 69. | Hottentot kraal | 229 |

| 70. | Card playing by Hottentots | 237 |

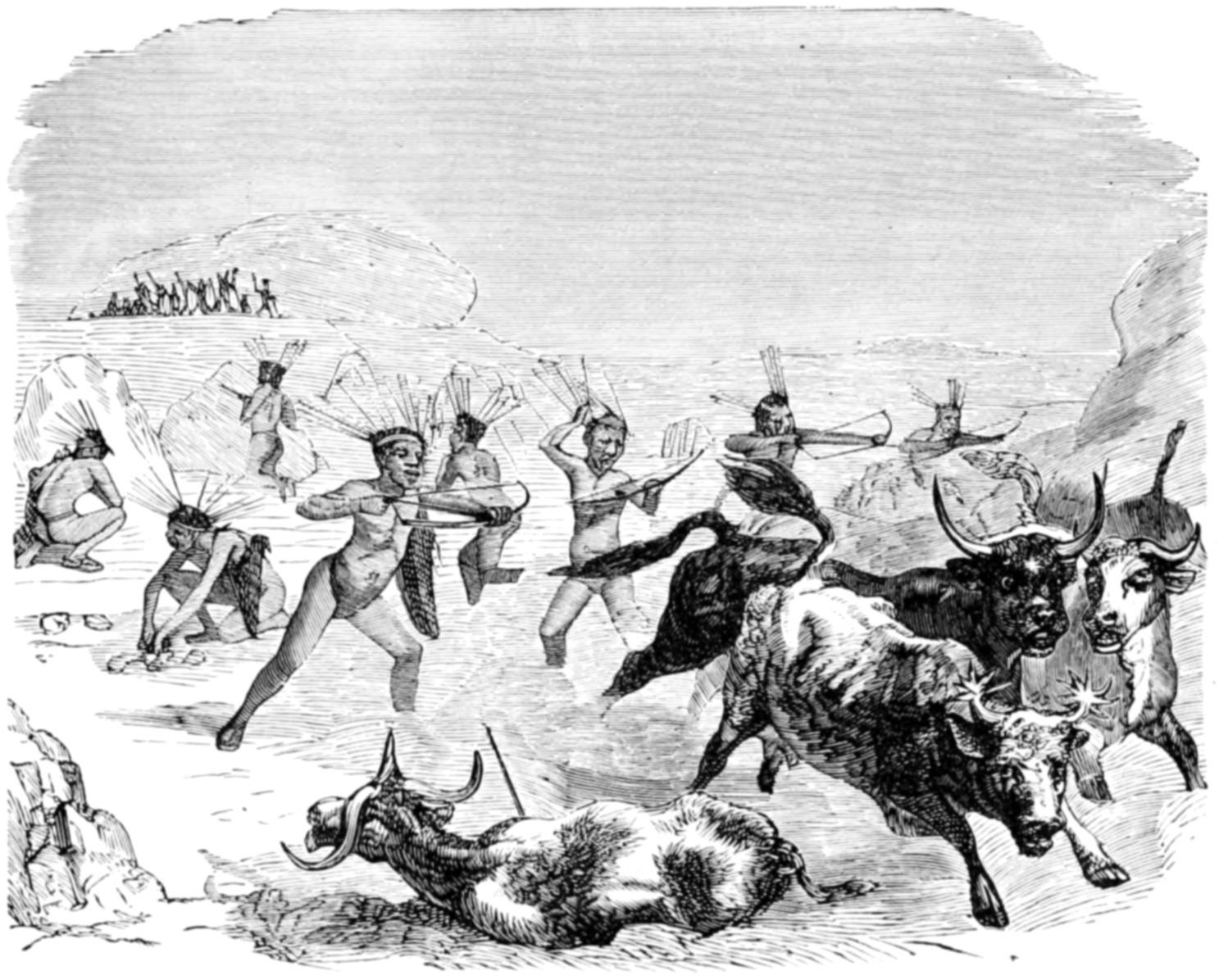

| 71. | Bosjesman shooting cattle | 237 |

| 72. | Grapple plant | 247 |

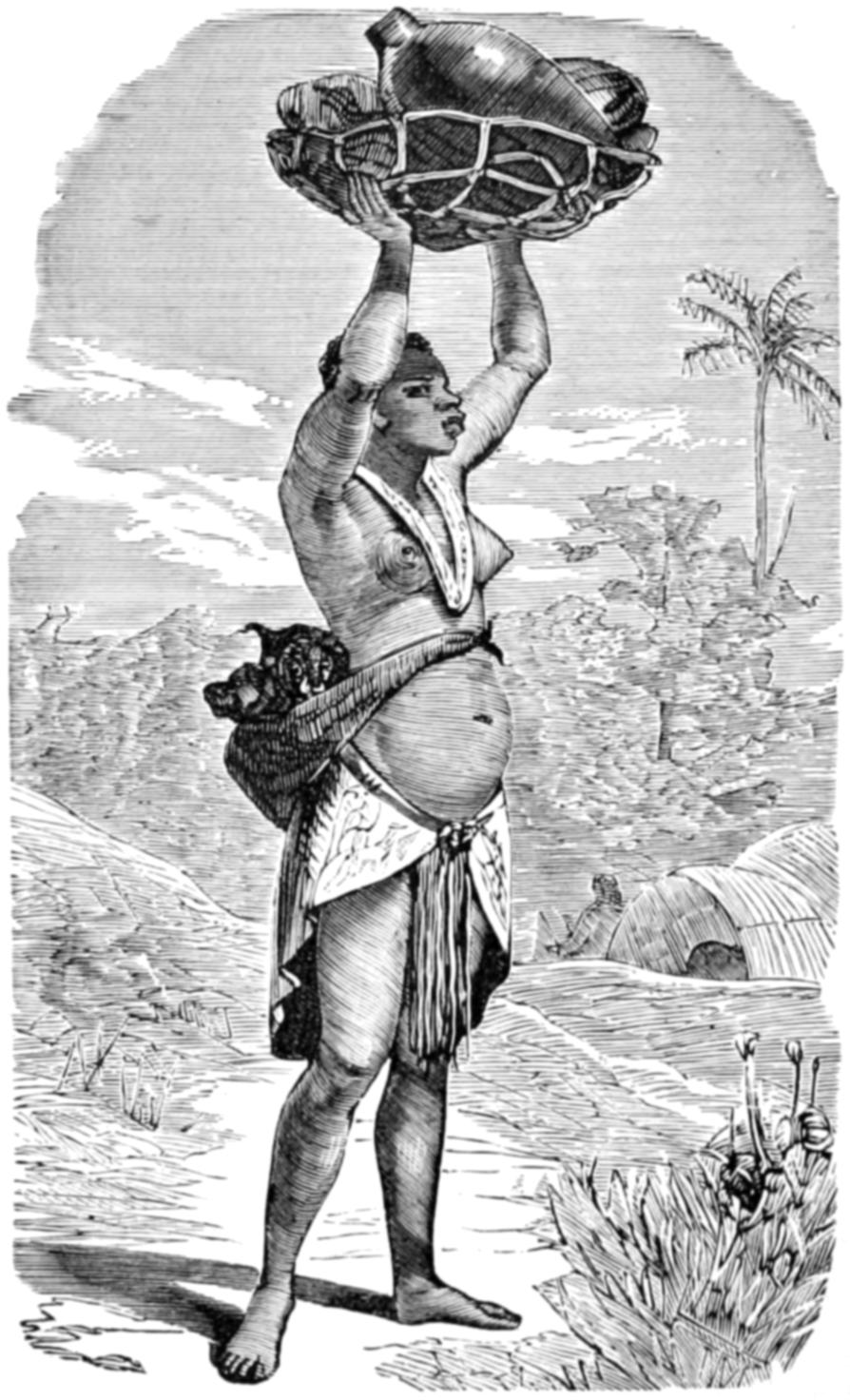

| 73. | Bosjesman woman and child | 247 |

| 74. | Hottentots asleep | 247 |

| 75. | Bosjesman quiver | 247 |

| 76. | Frontlet of Hottentot girl | 247 |

| 77. | Poison grub | 259 |

| 78. | Portrait of Koranna chief | 271 |

| 79. | Namaquas shooting at the storm | 271 |

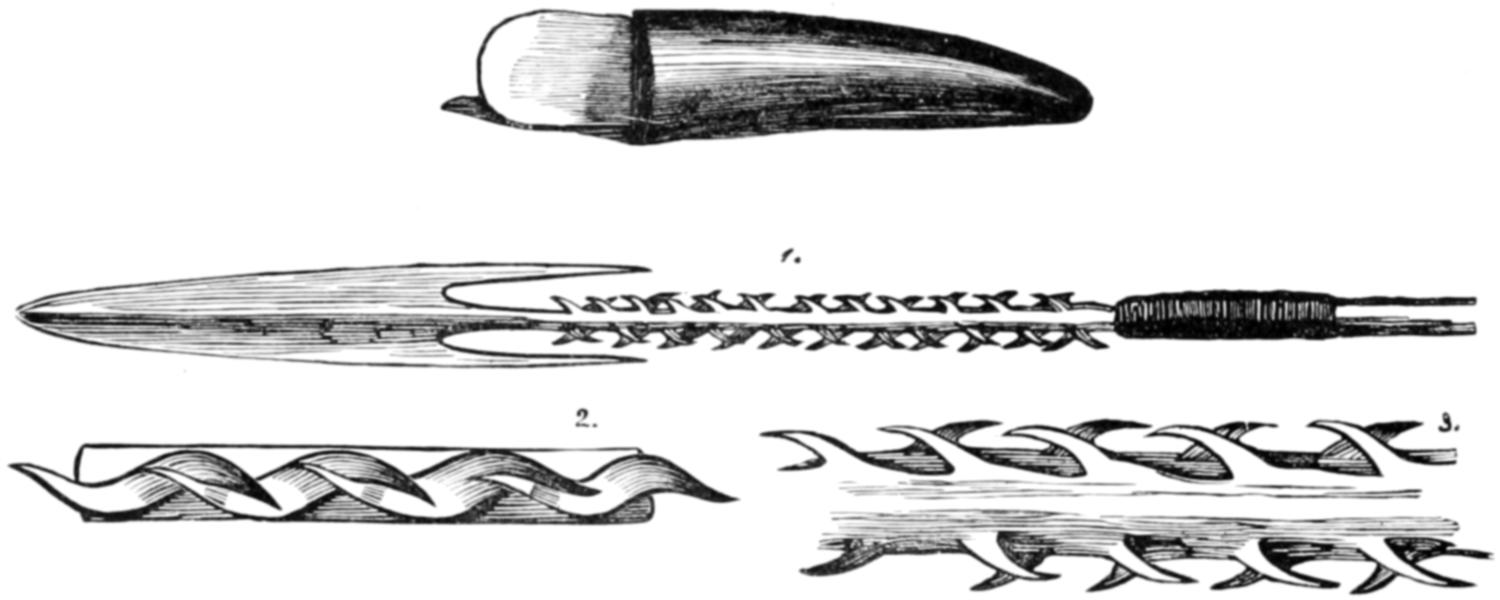

| 80. | Knife and assagai heads | 281 |

| 81. | Bechuana knives | 281 |

| 82. | A Bechuana apron | 281 |

| 83. | Ornament made of monkeys’ teeth | 281 |

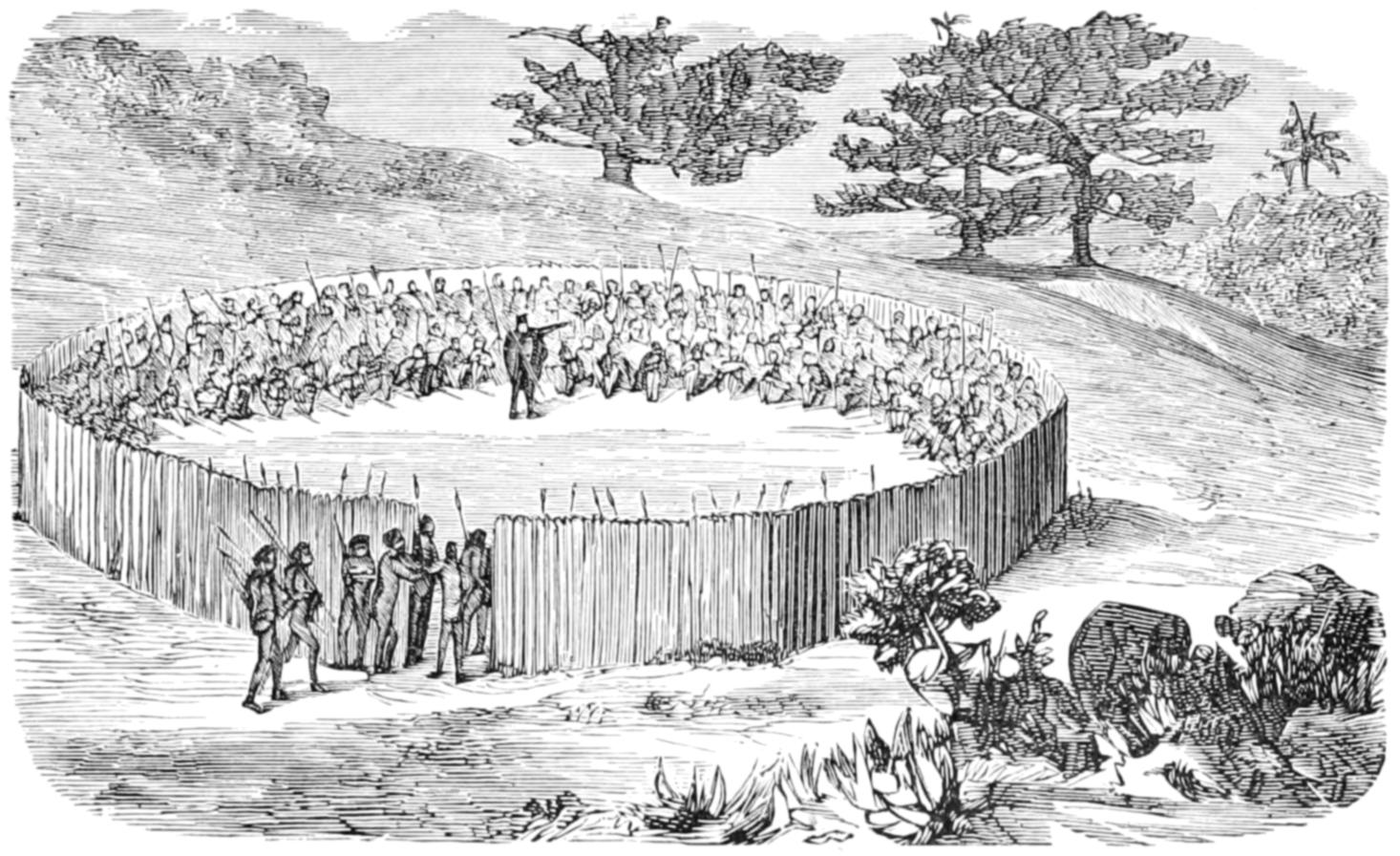

| 84. | Bechuana parliament | 287 |

| 85. | Female architects among the Bechuanas | 287 |

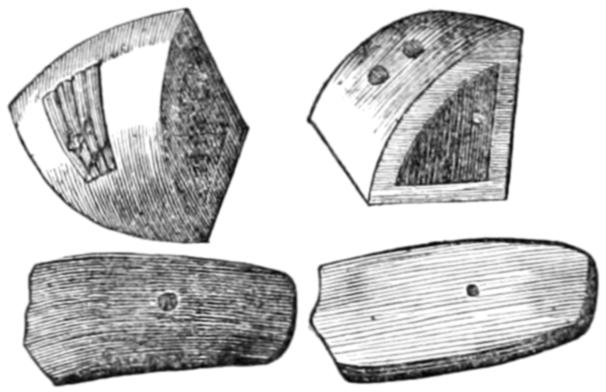

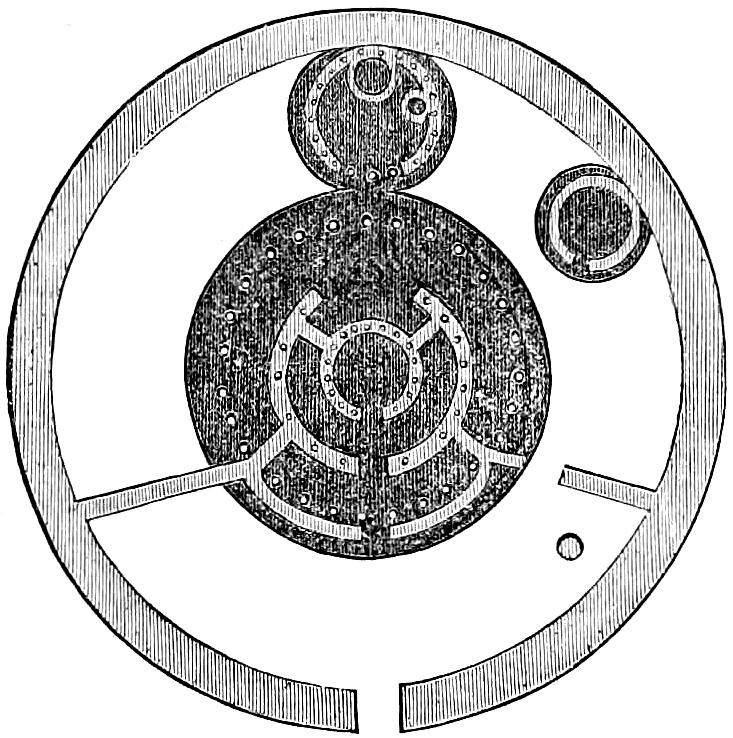

| 86. | Magic dice of the Bechuanas | 292 |

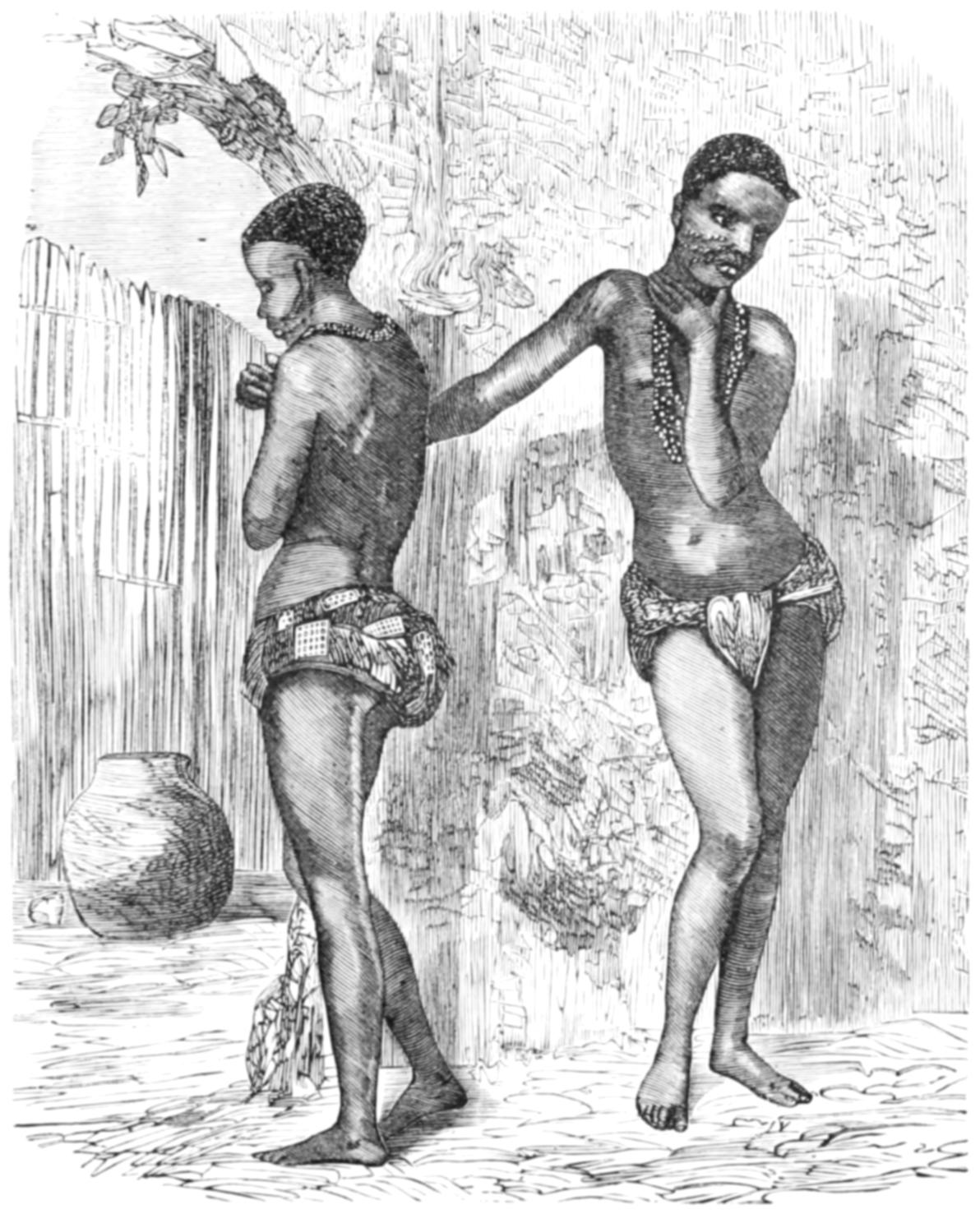

| 87. | Spartan practices among the Bechuanas | 294 |

| 88. | The girl’s ordeal among the Bechuanas | 294 |

| 89. | Plan of Bechuana house | 299 |

| 90. | Bechuana funeral[iv] | 302 |

| 91. | Grave and monument of Damara chief | 302 |

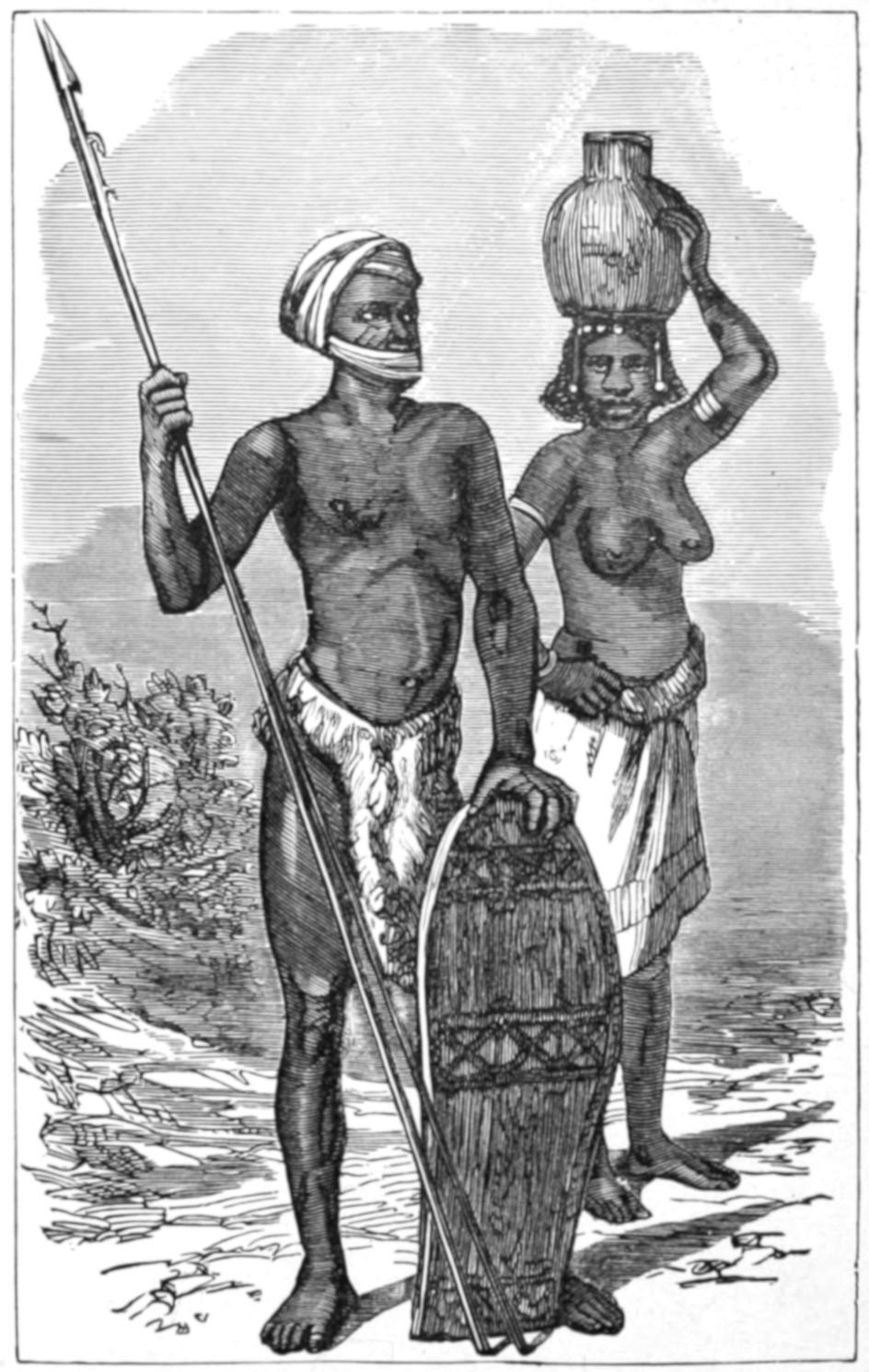

| 92. | Damara warrior and wife | 308 |

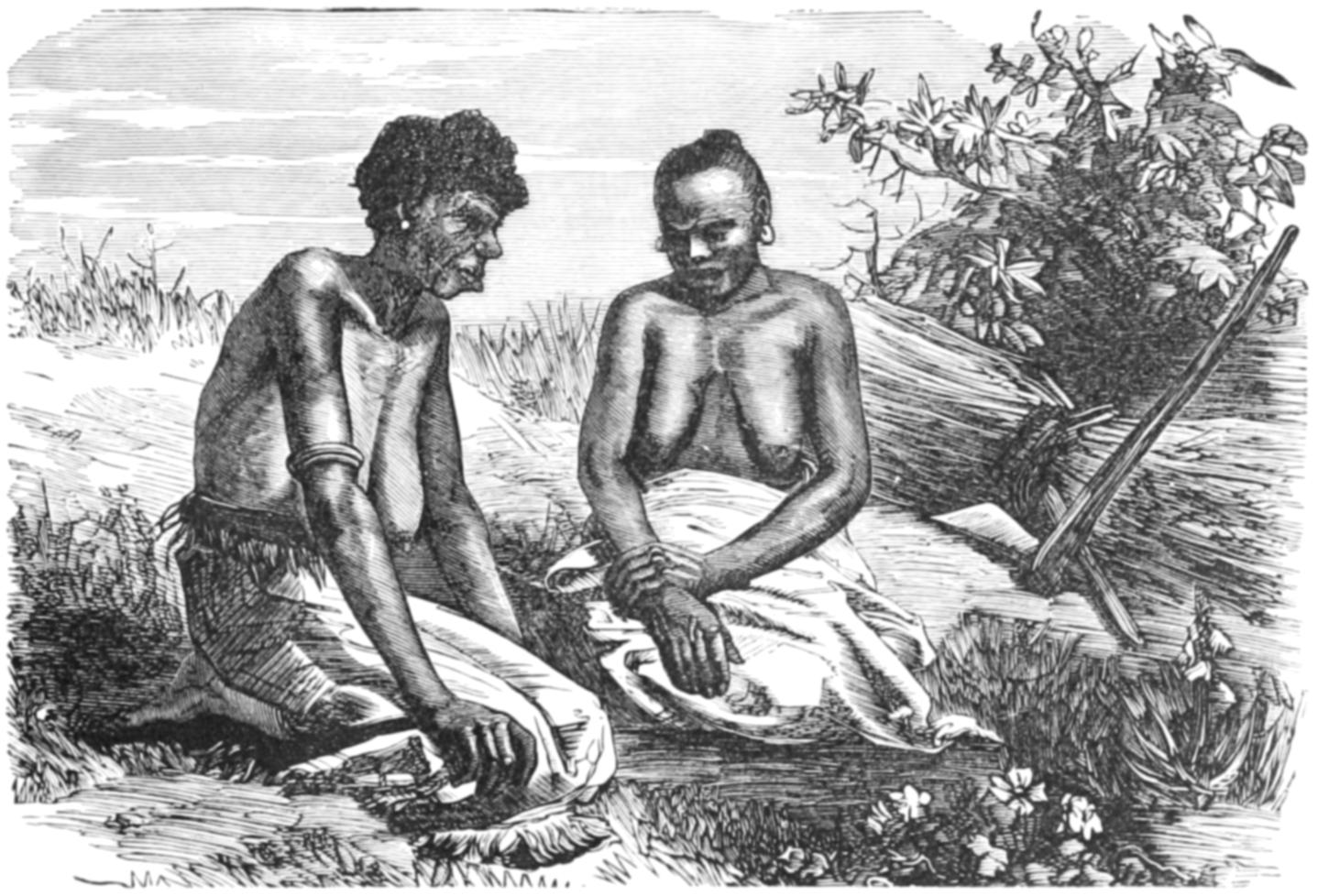

| 93. | Damara girl resting | 308 |

| 94. | Portrait of Ovambo girl | 317 |

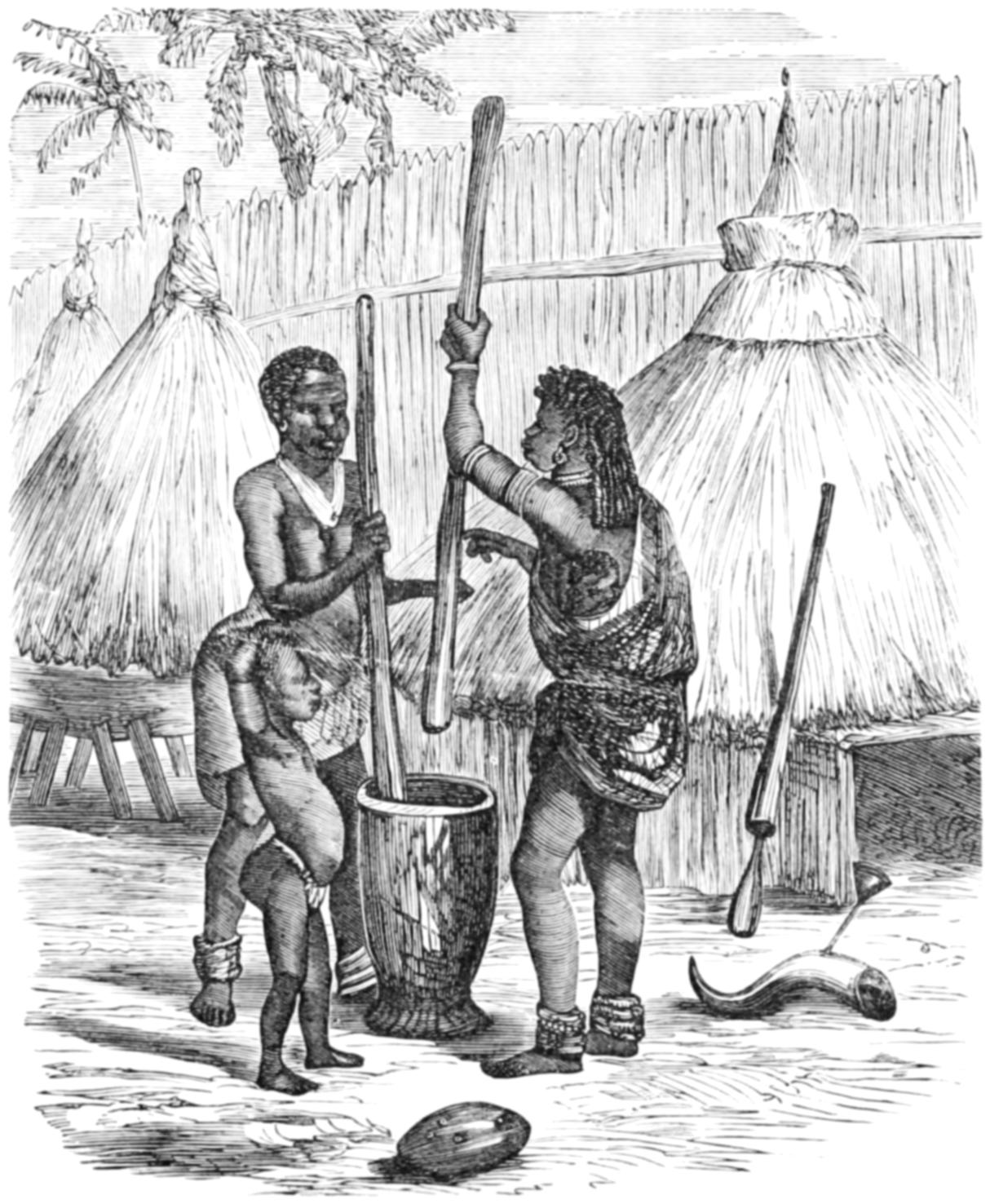

| 95. | Ovambo women pounding corn | 317 |

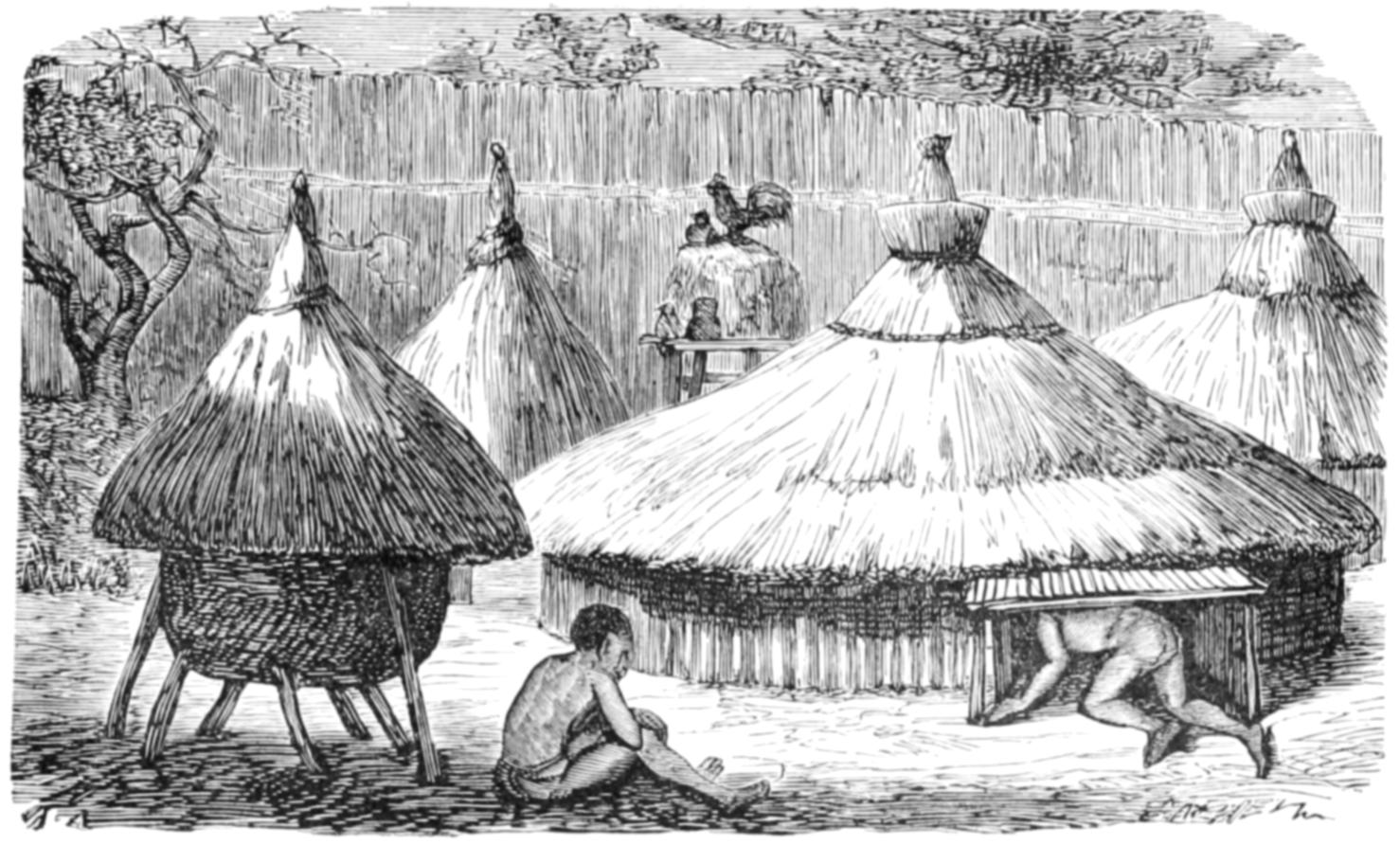

| 96. | Ovambo houses | 329 |

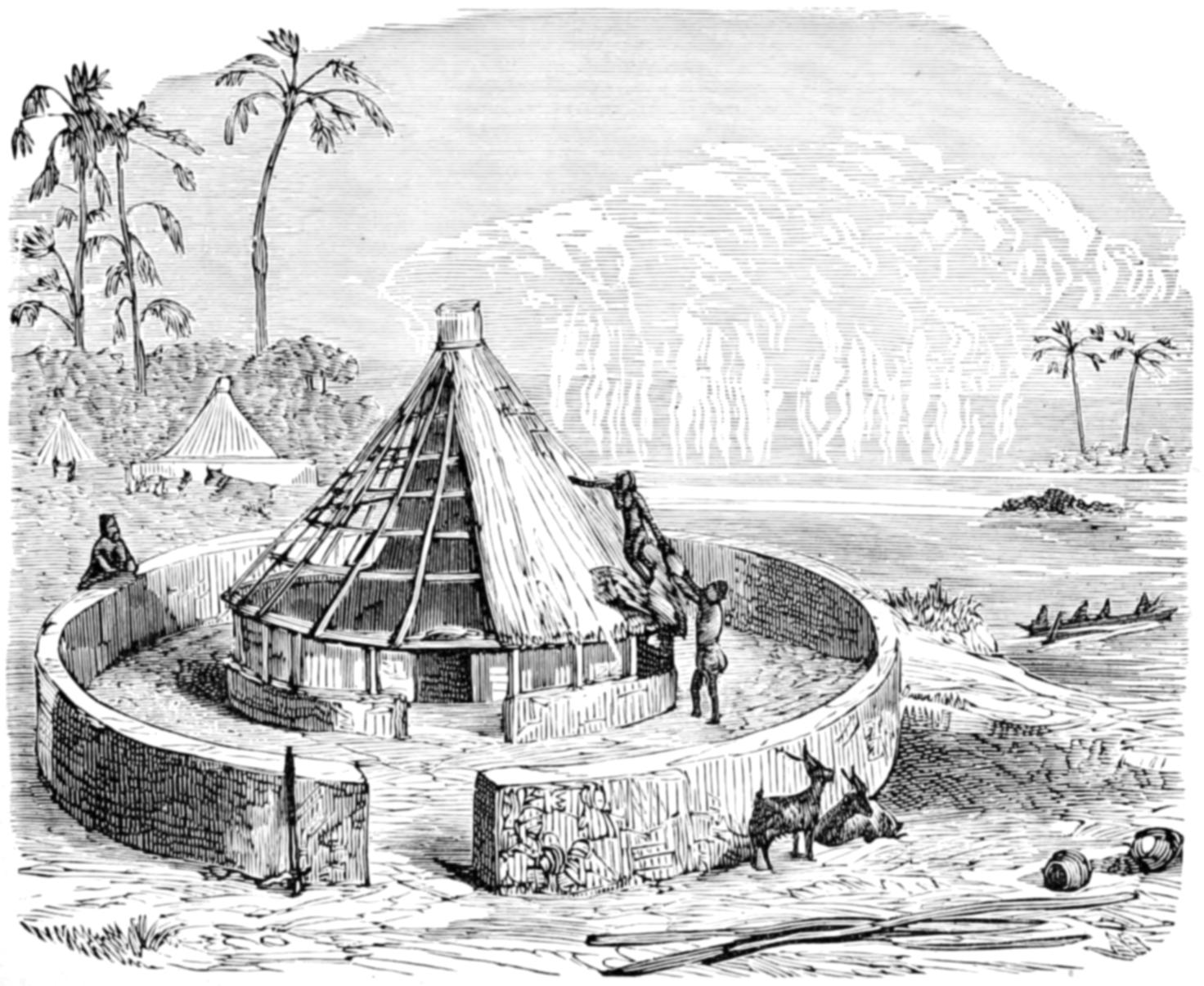

| 97. | Makololo house building | 329 |

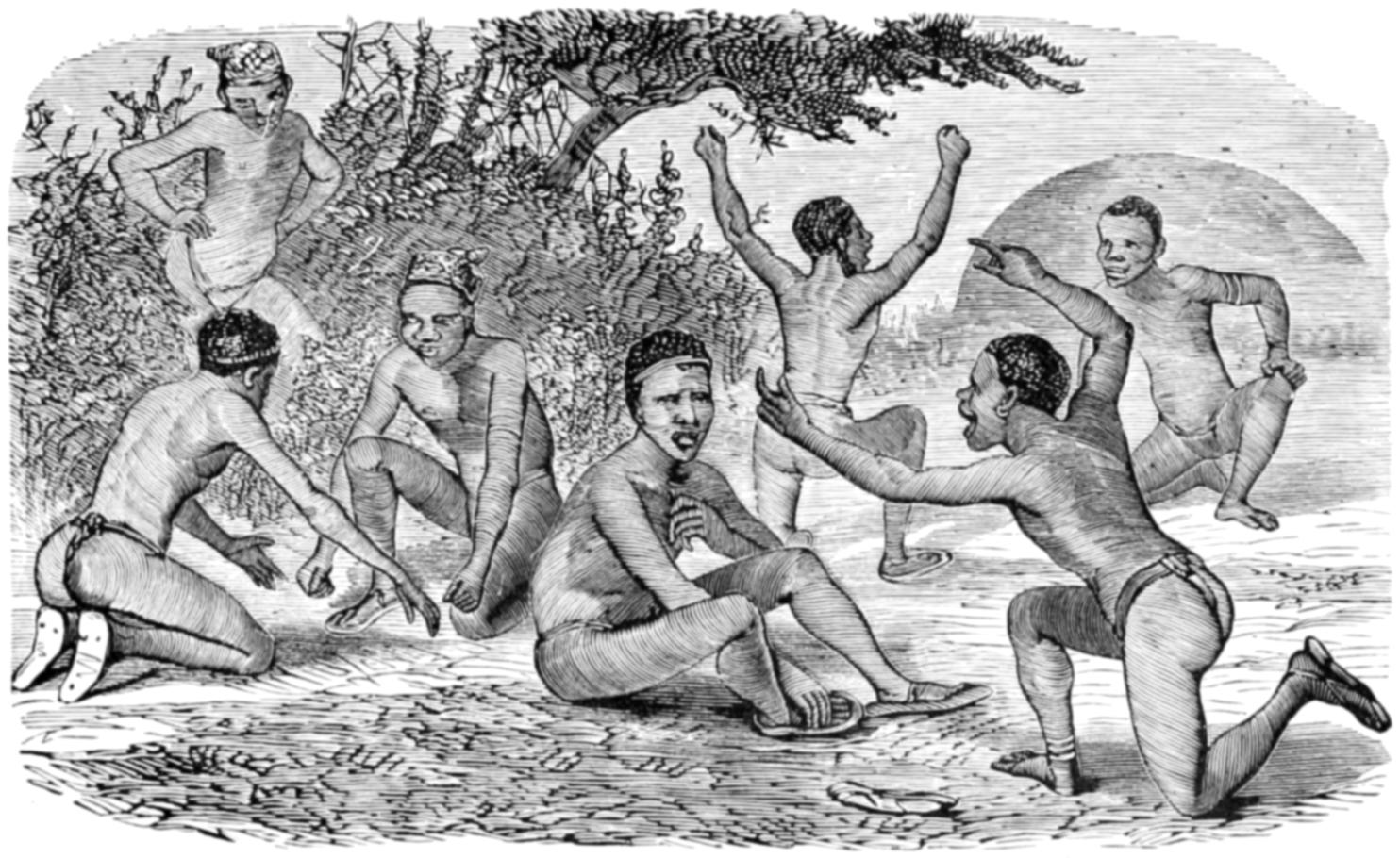

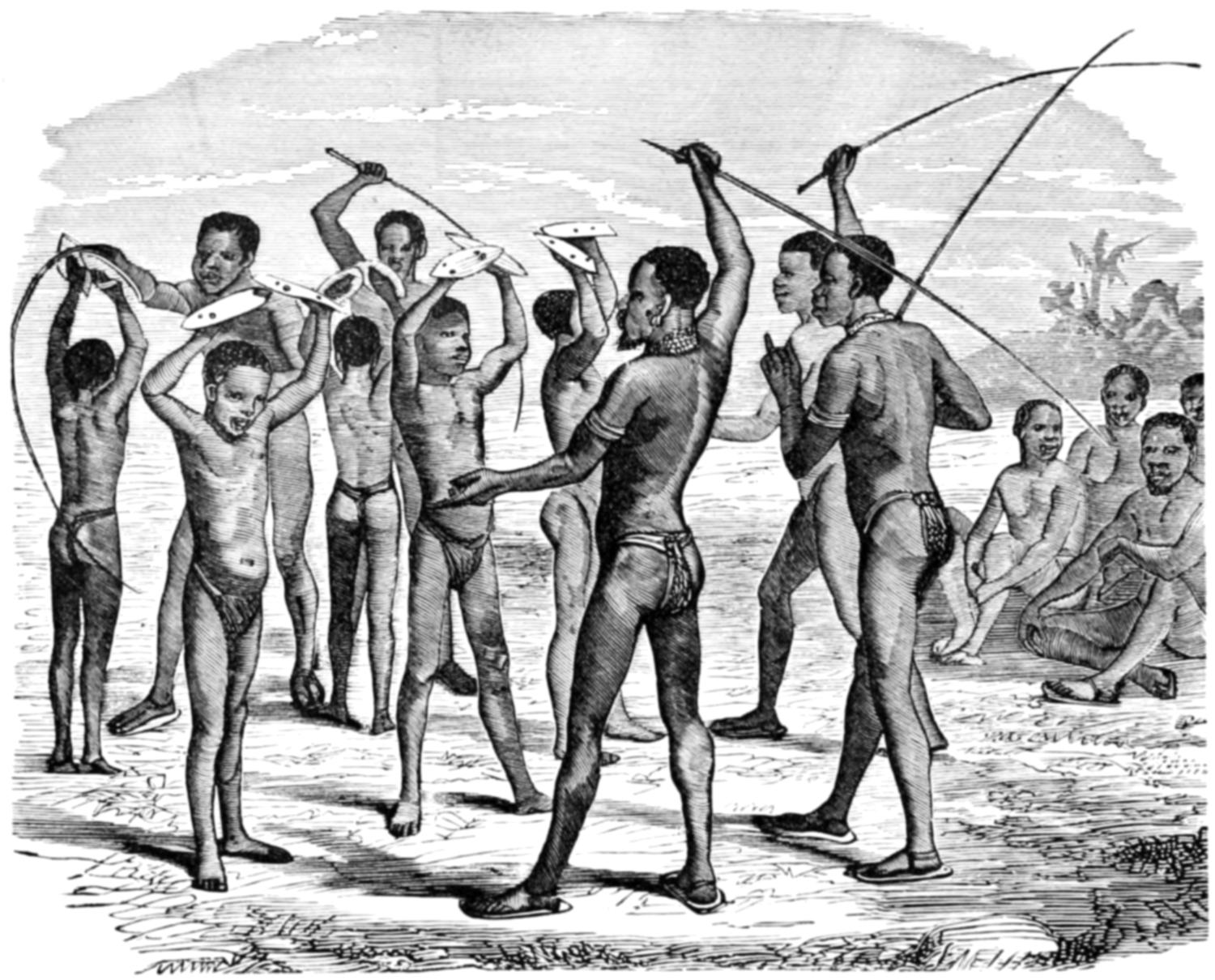

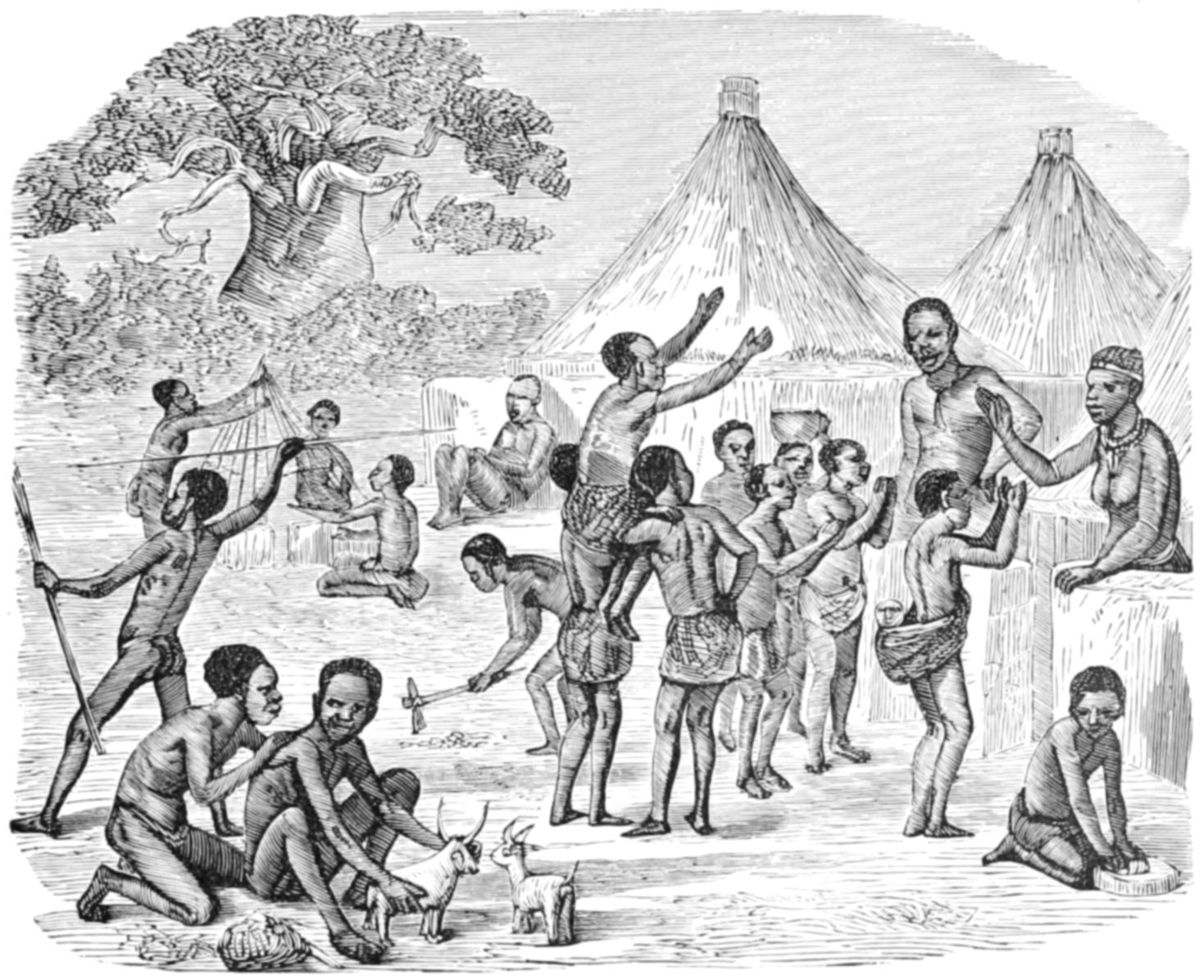

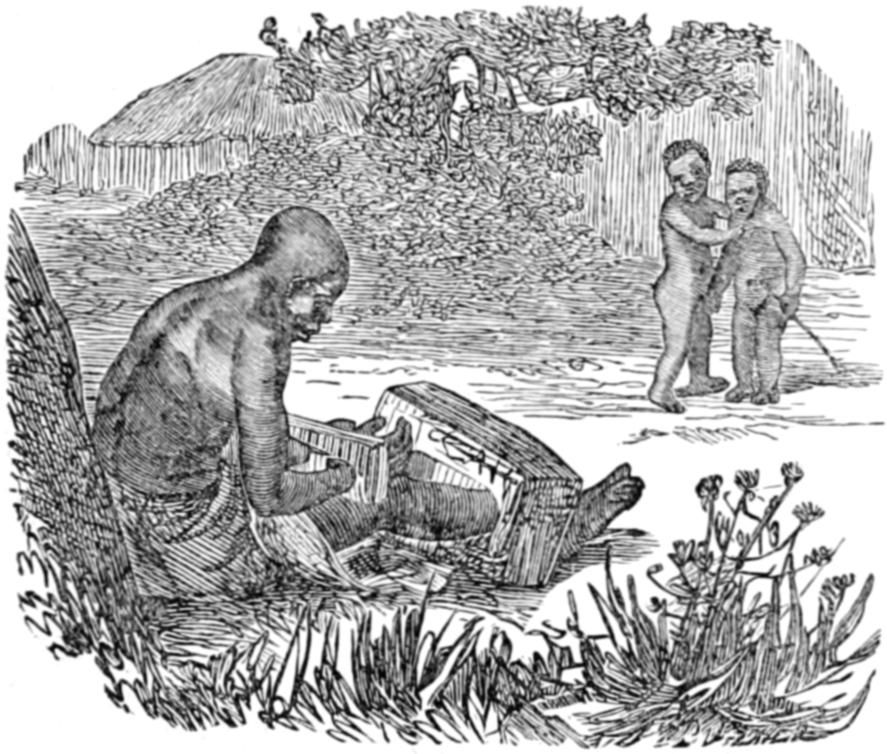

| 98. | Children’s games among the Makololo | 333 |

| 99. | M’Bopo, a Makololo chief, at home | 333 |

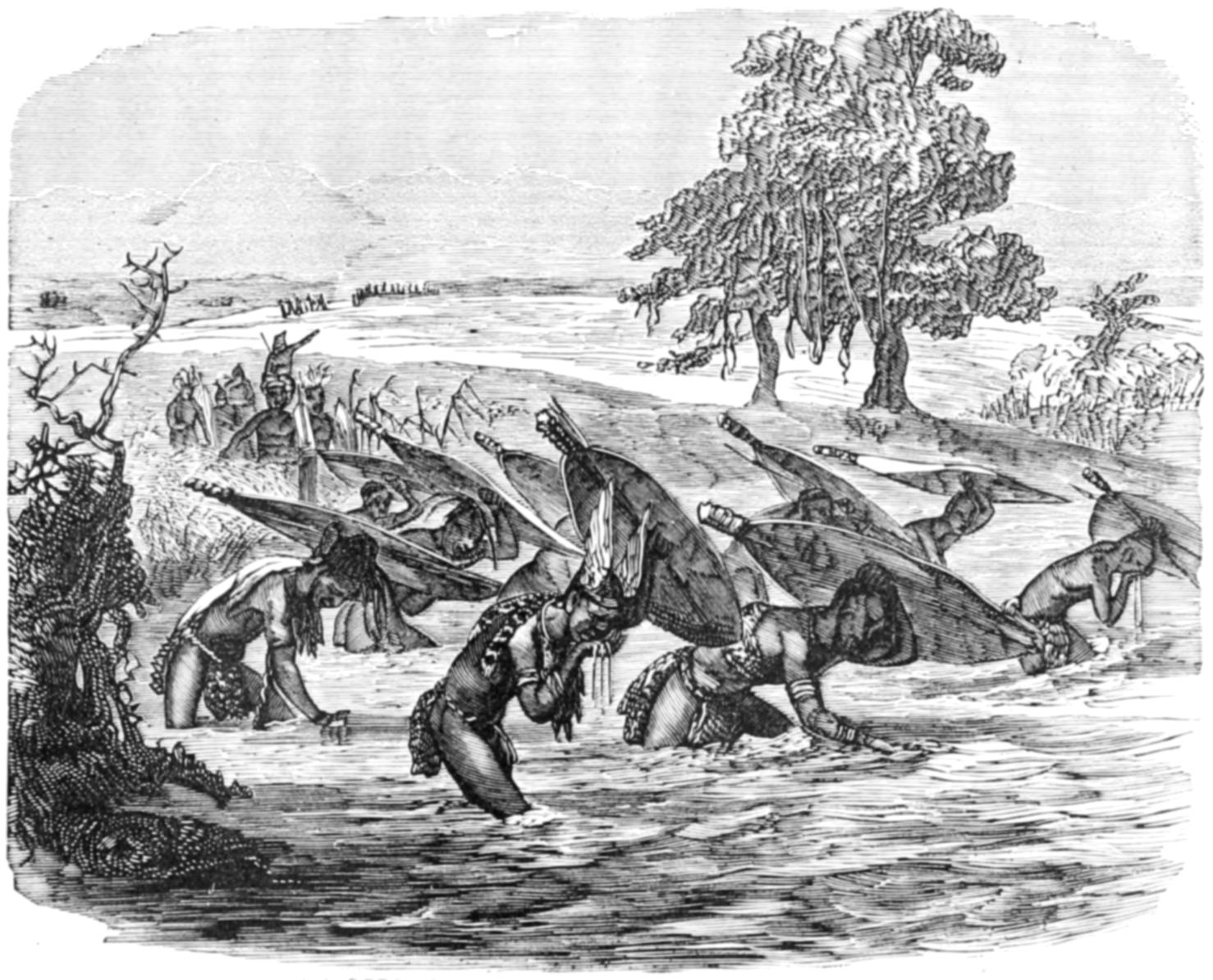

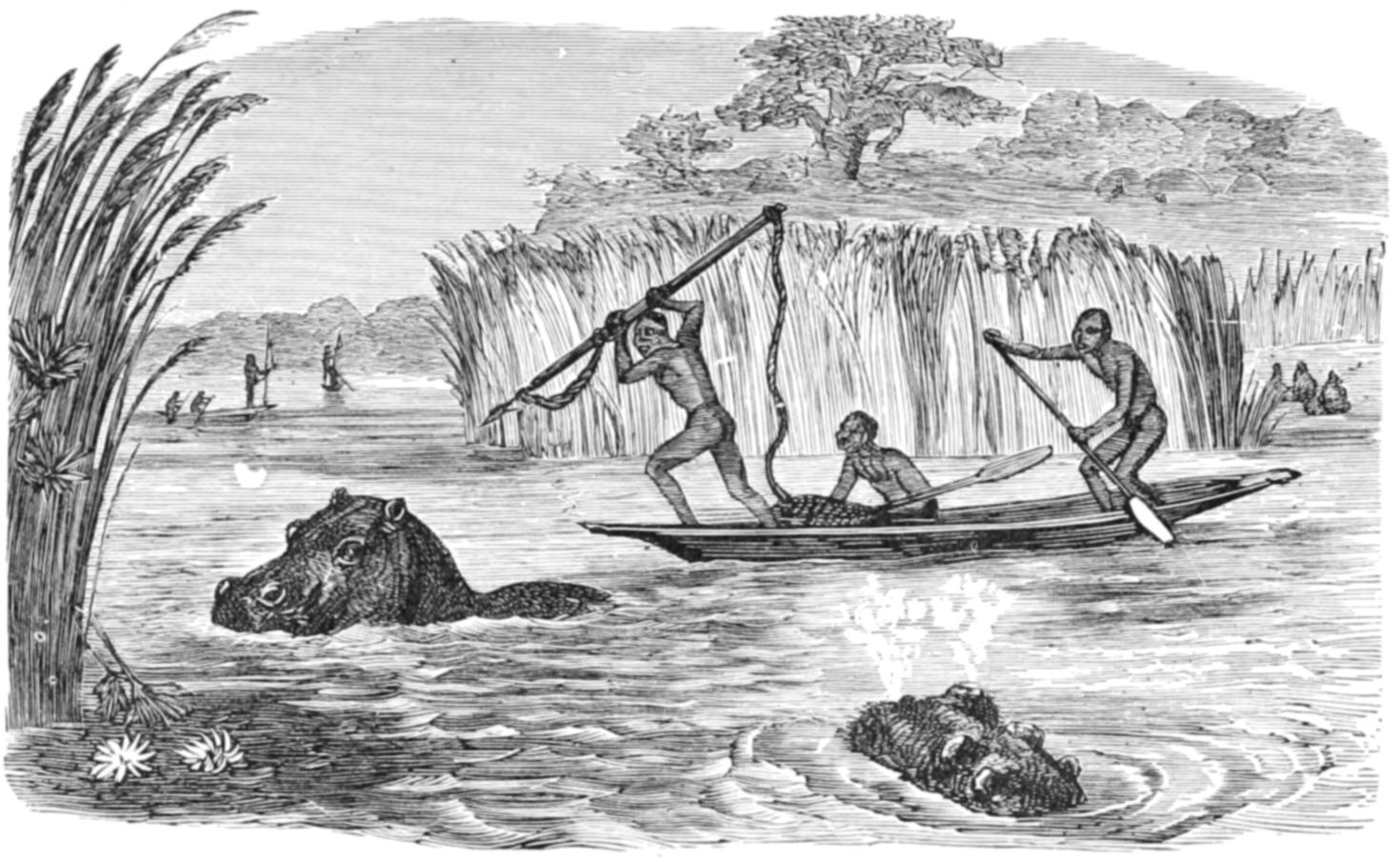

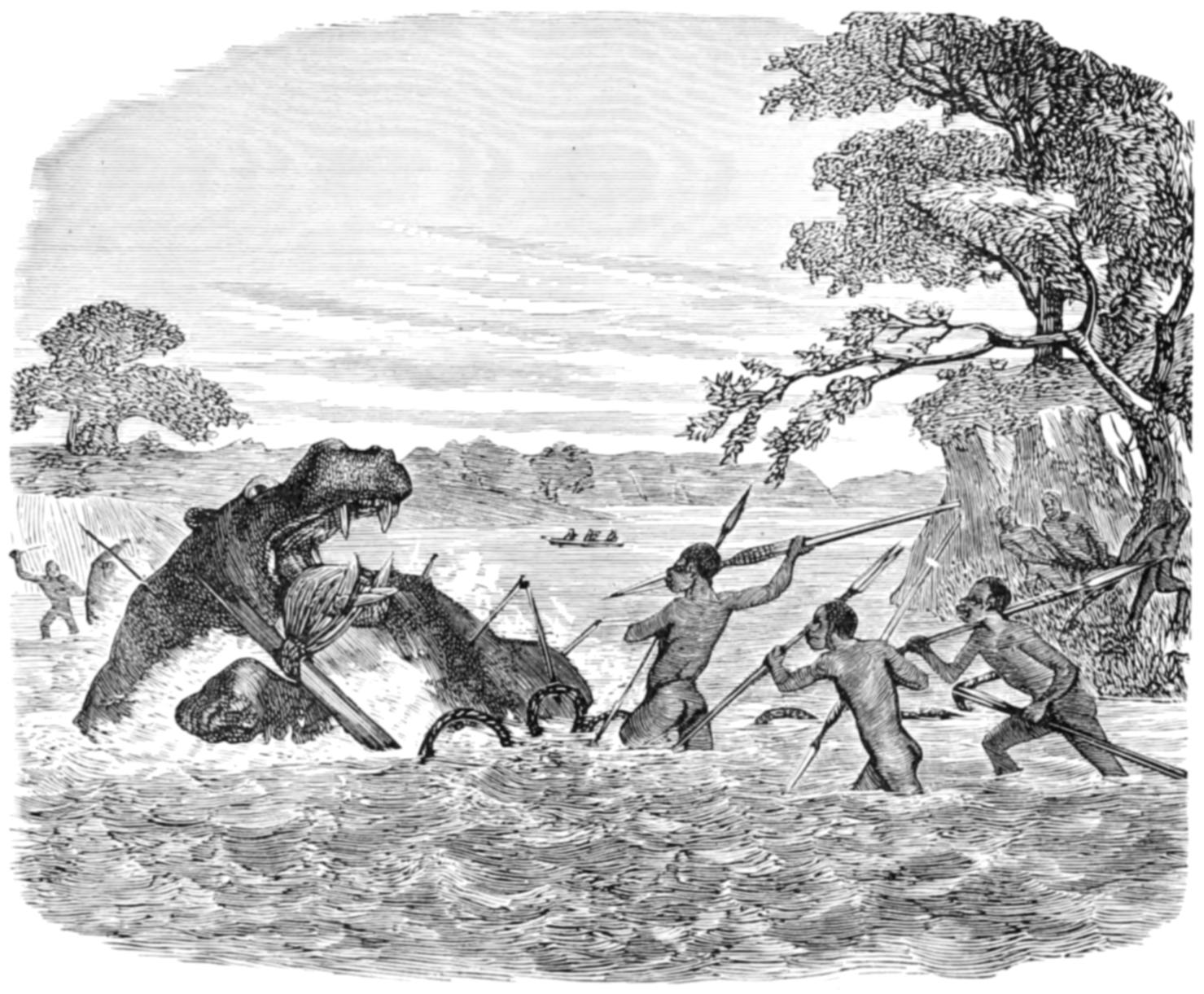

| 100. | Spearing the hippopotamus | 343 |

| 101. | The final attack | 343 |

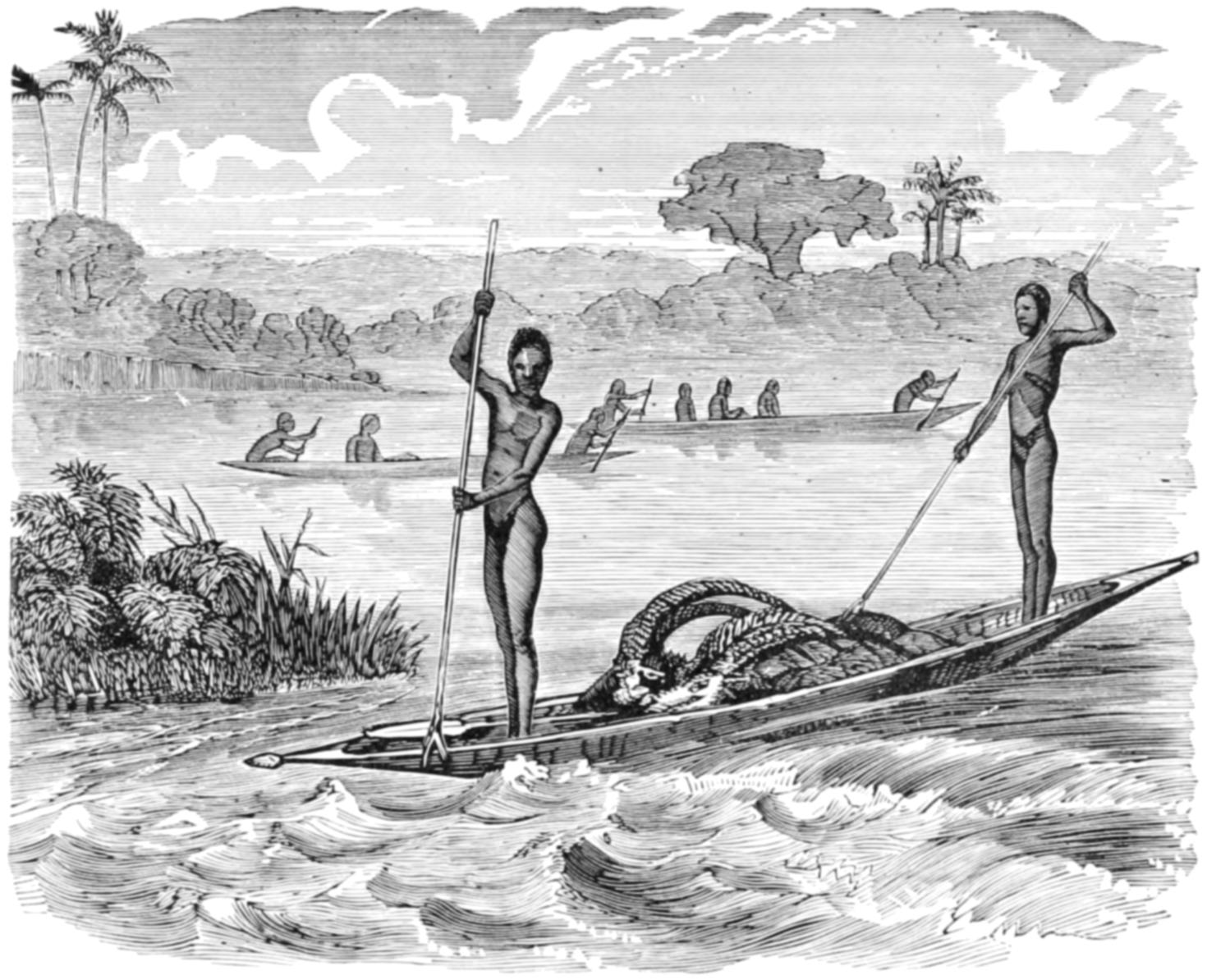

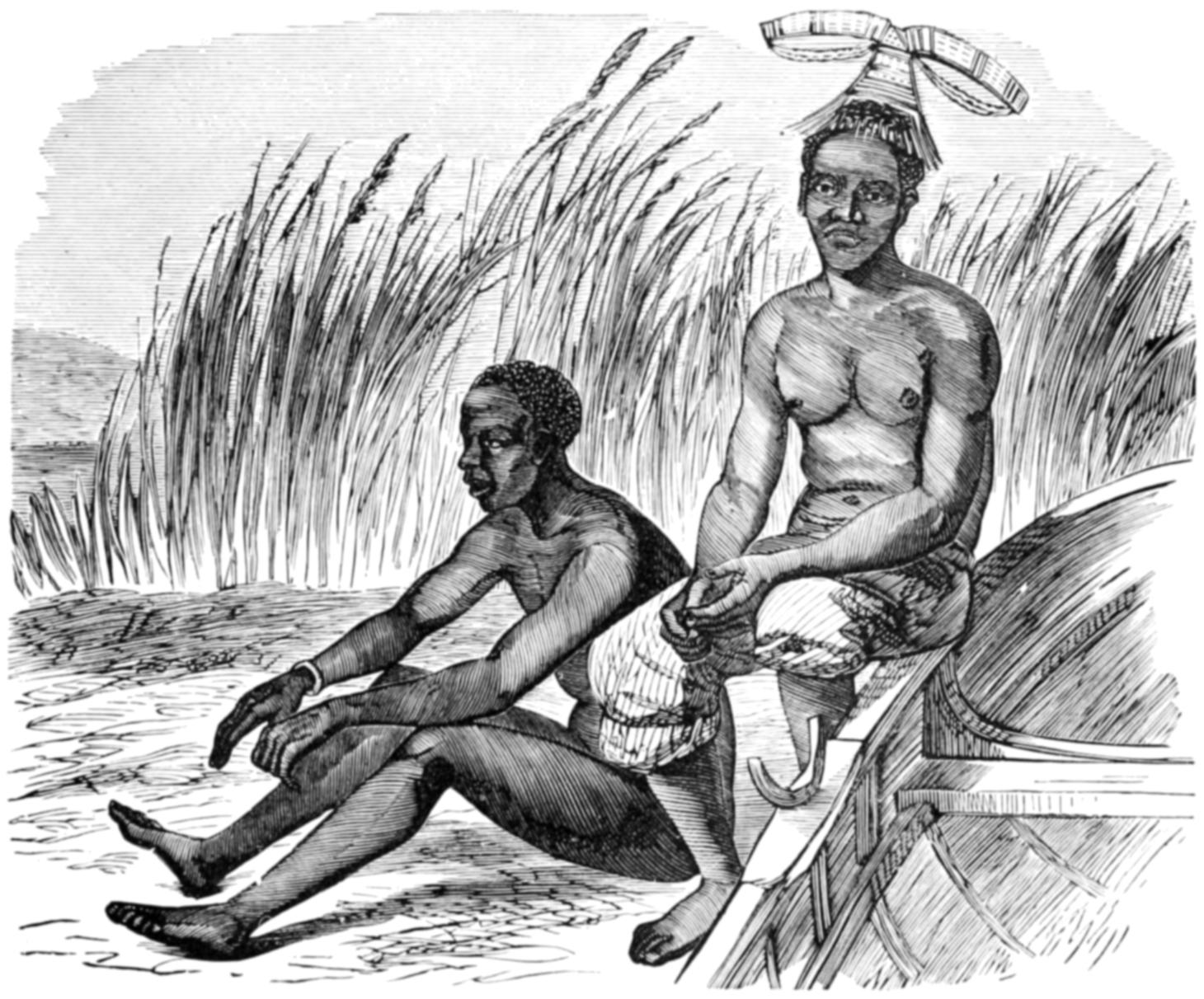

| 102. | Boating scene on the Bo-tlet-le River | 351 |

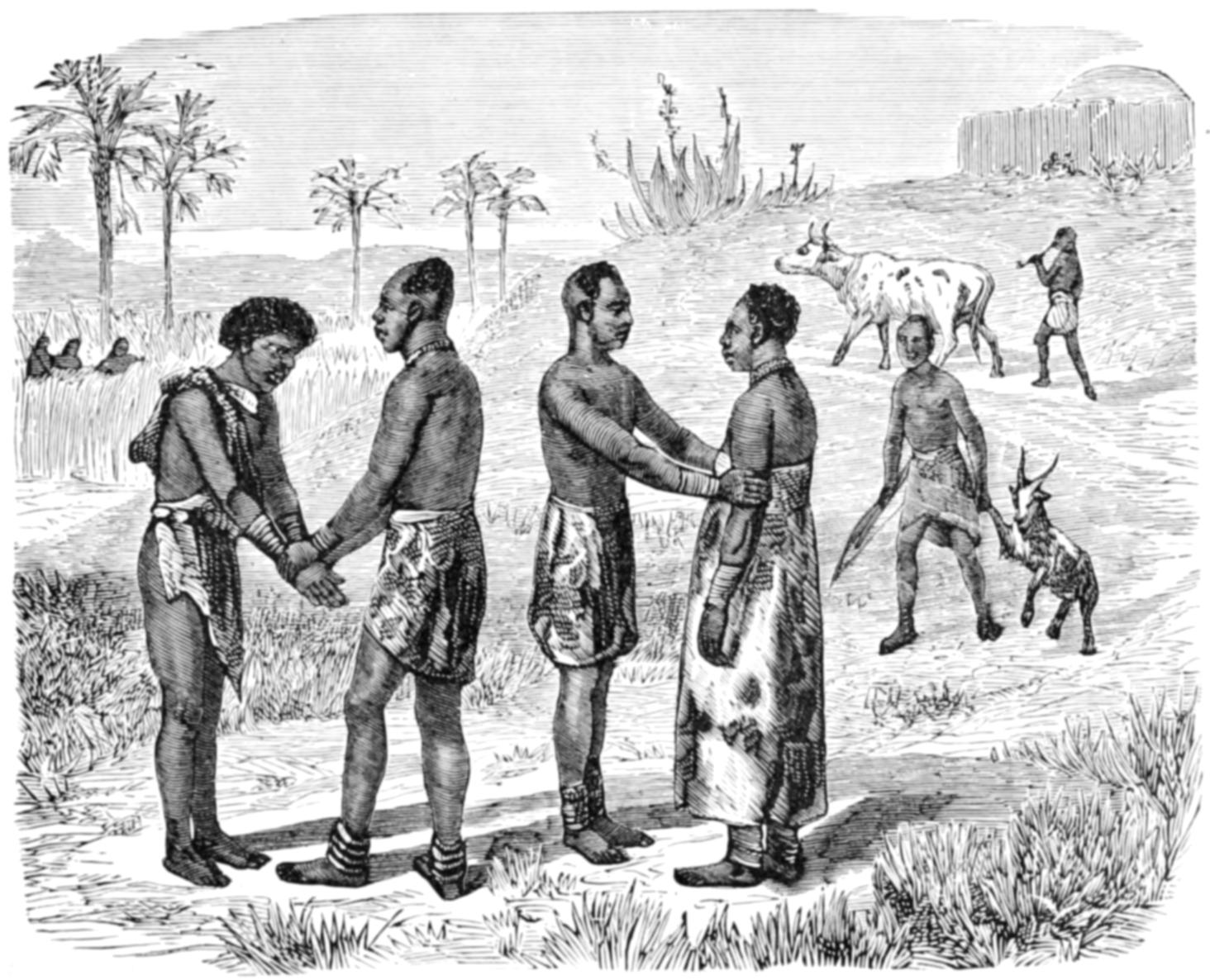

| 103. | Batoka salutation | 351 |

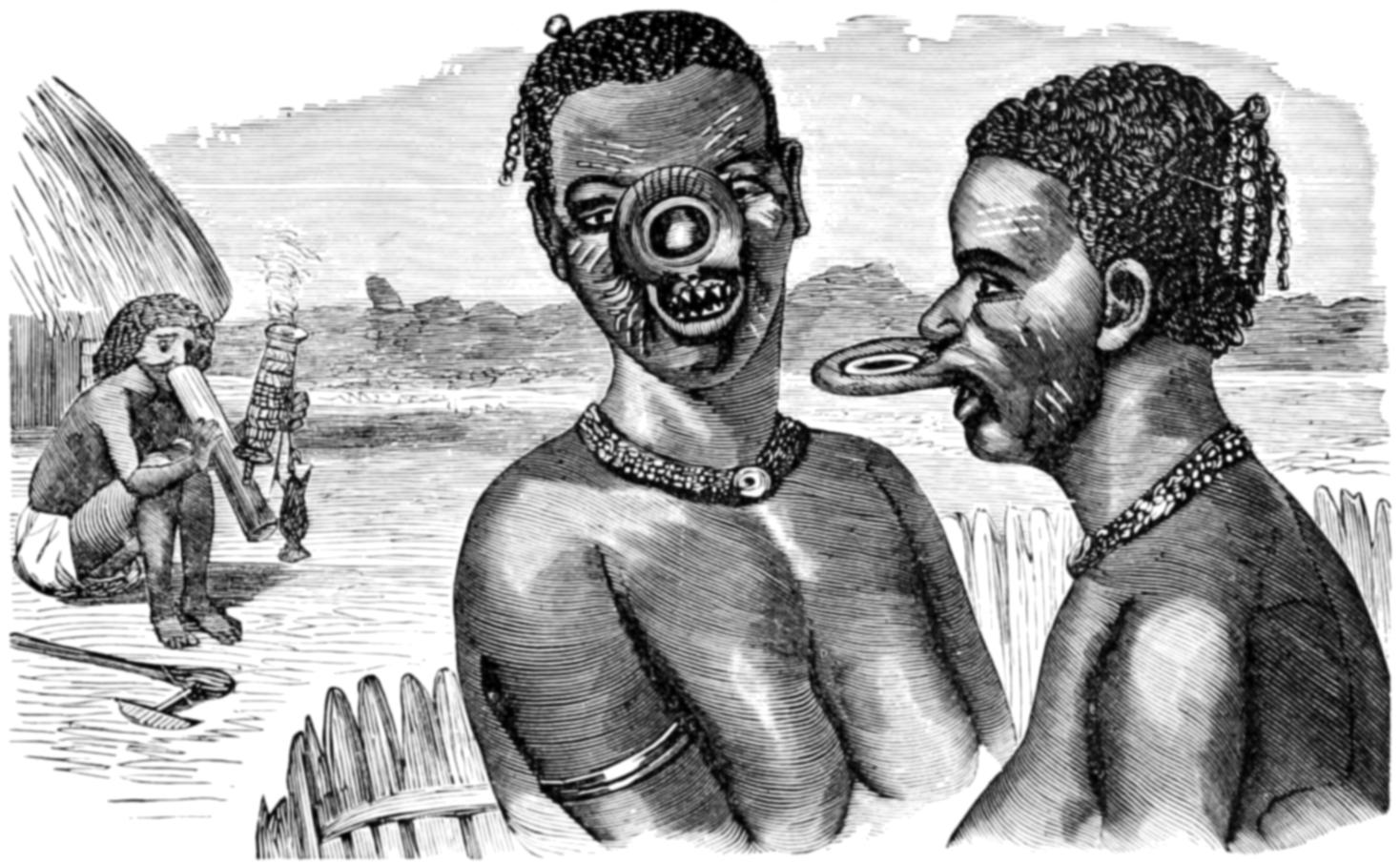

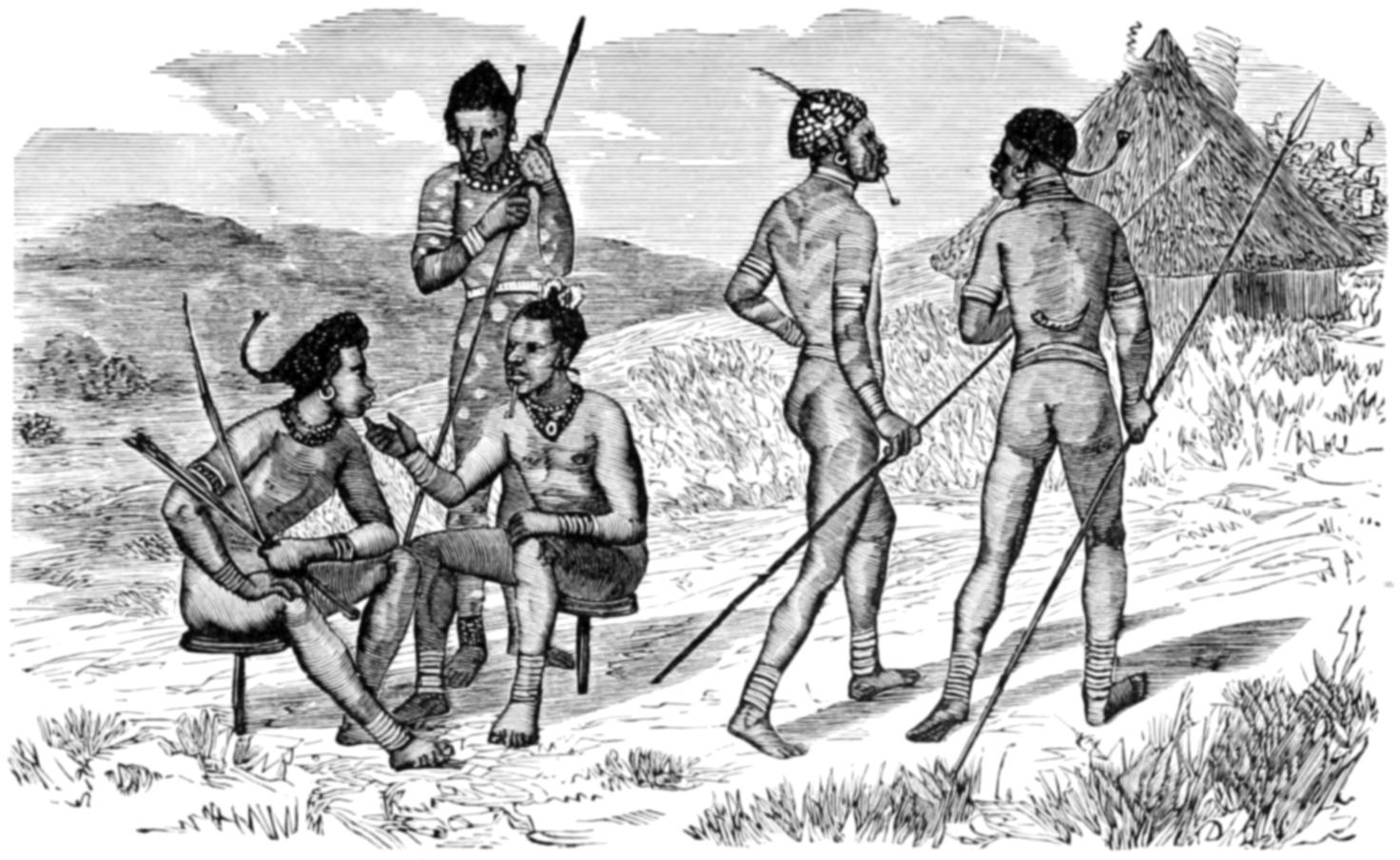

| 104. | Batoka men | 357 |

| 105. | Pelele, or lip ring, of the Manganjas | 357 |

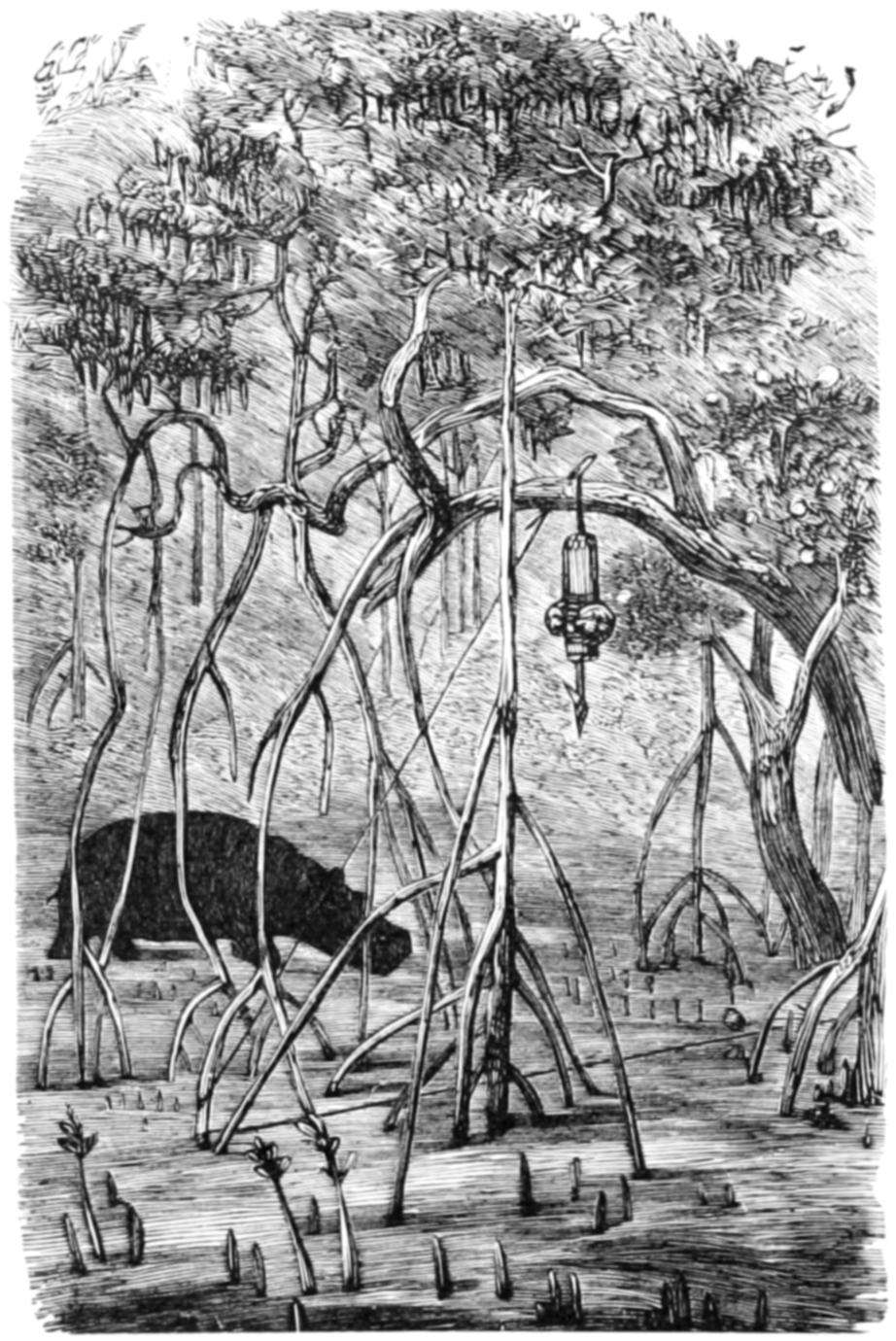

| 106. | Hippopotamus trap | 363 |

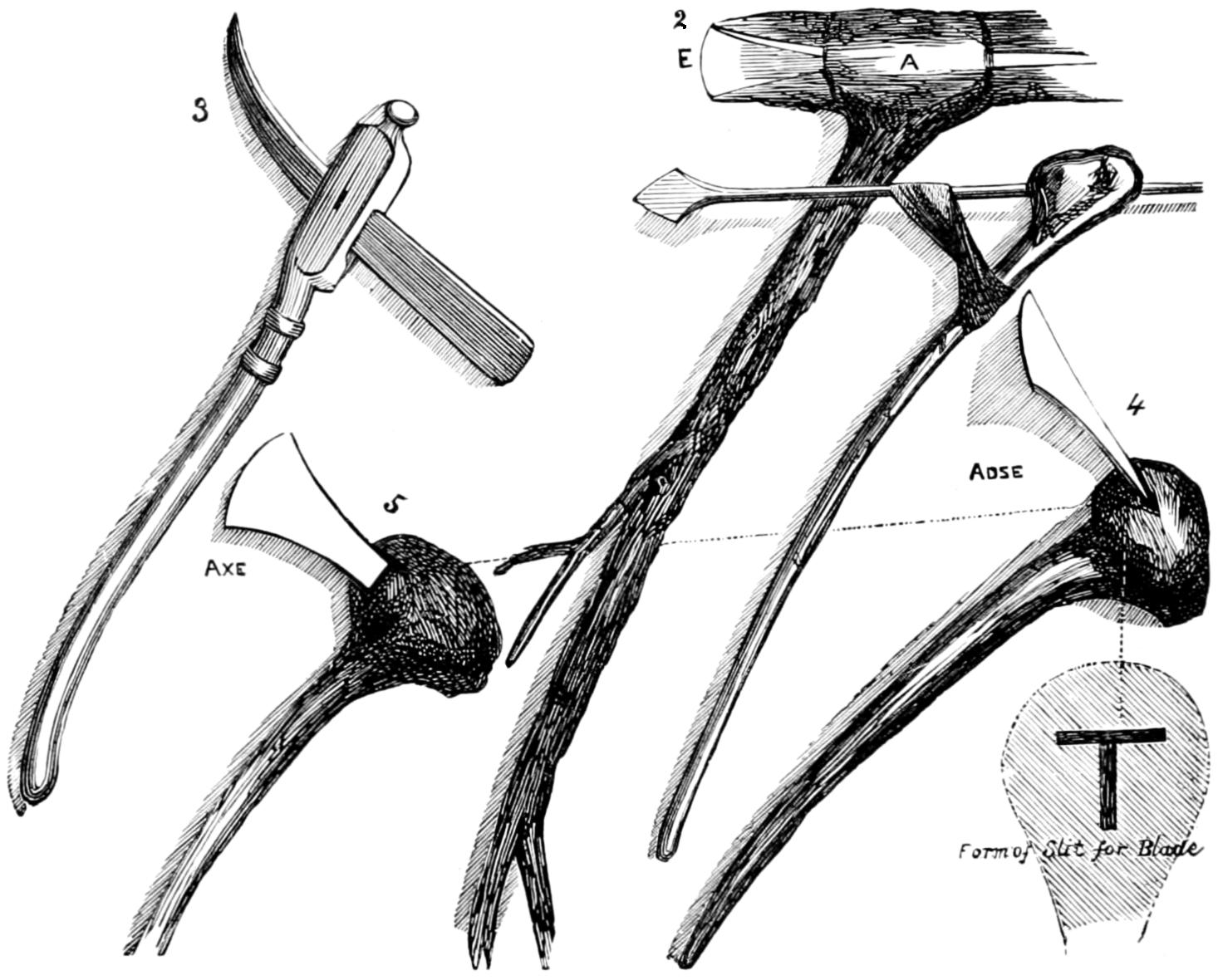

| 107. | Axes of the Banyai | 363 |

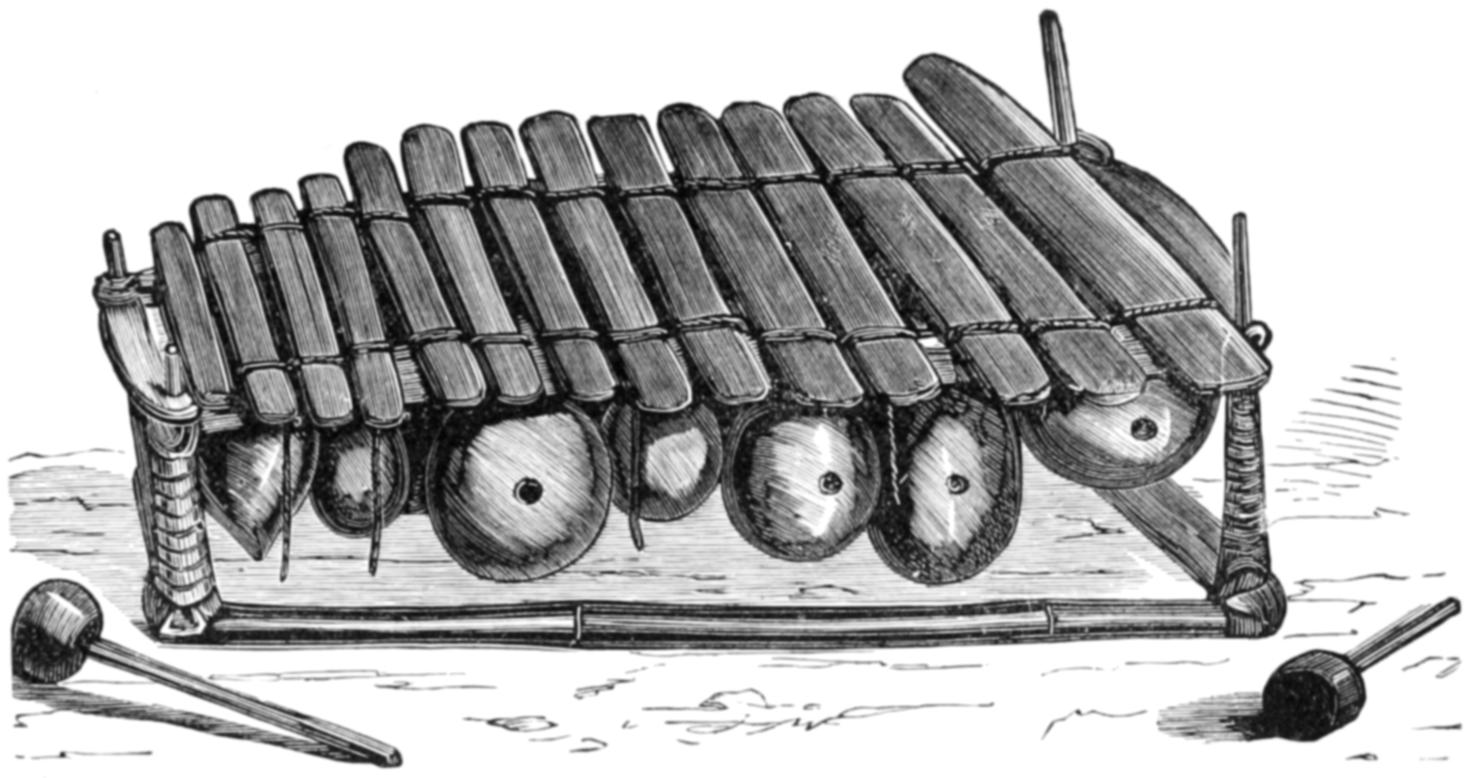

| 108. | The marimba, or African piano | 371 |

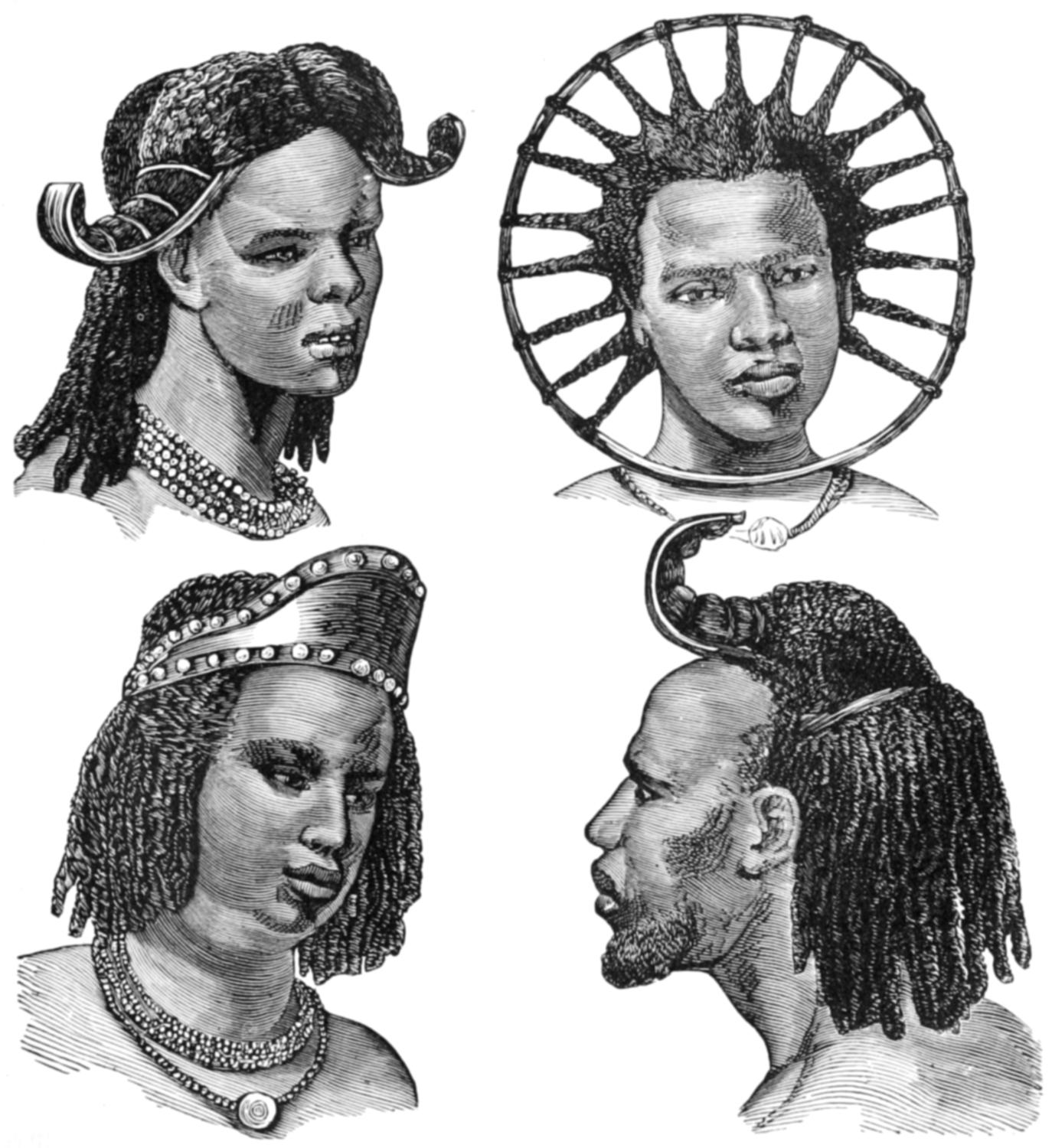

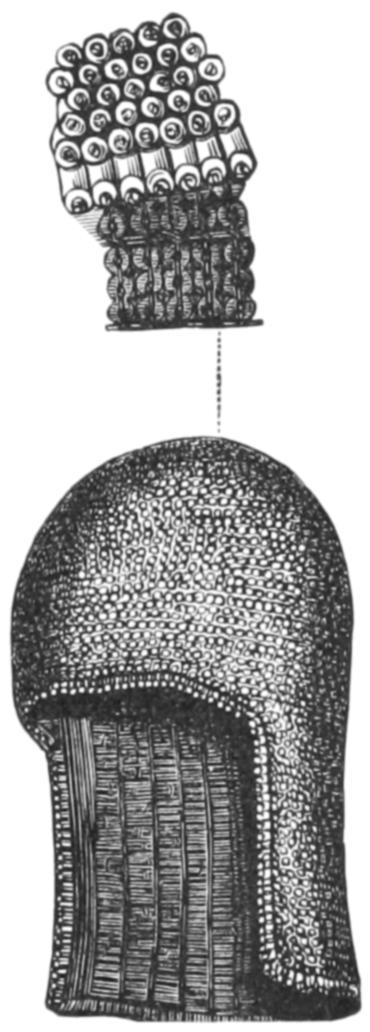

| 109. | Singular headdress of the Balonda women | 371 |

| 110. | Wagogo greediness | 387 |

| 111. | Architecture of the Weezee | 387 |

| 112. | A husband’s welcome among the Weezee | 391 |

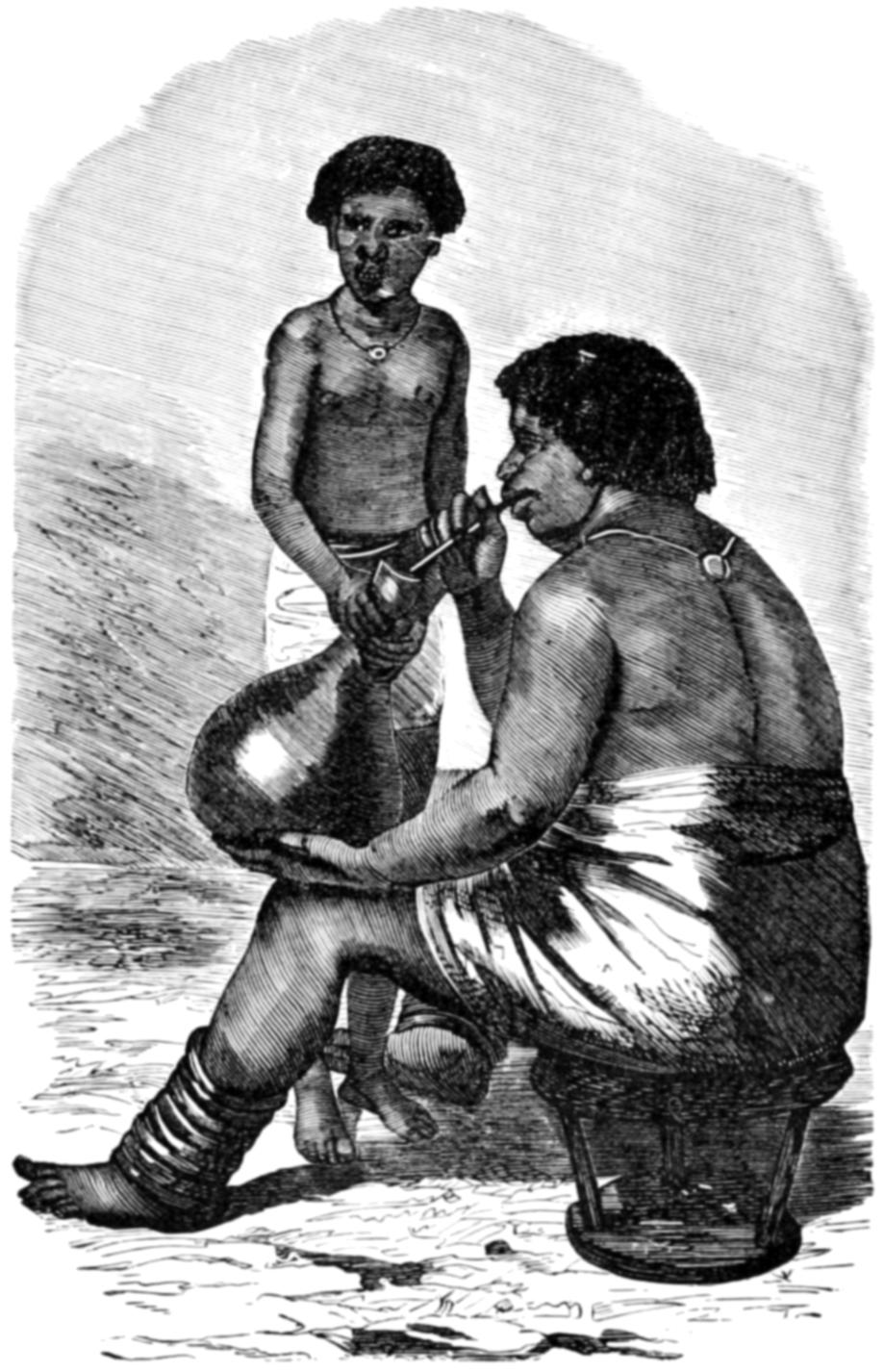

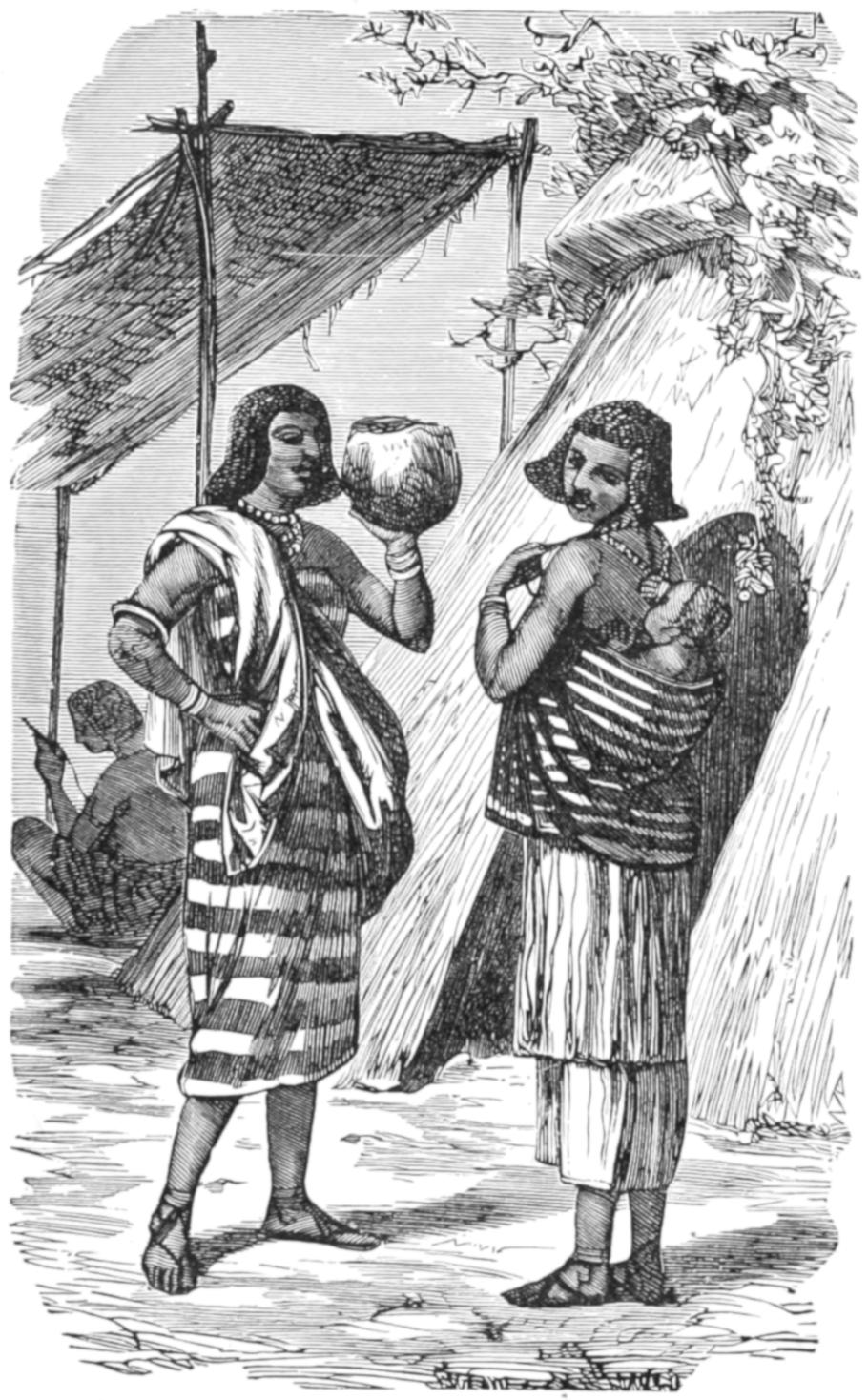

| 113. | Sultan Ukulima drinking pombé | 391 |

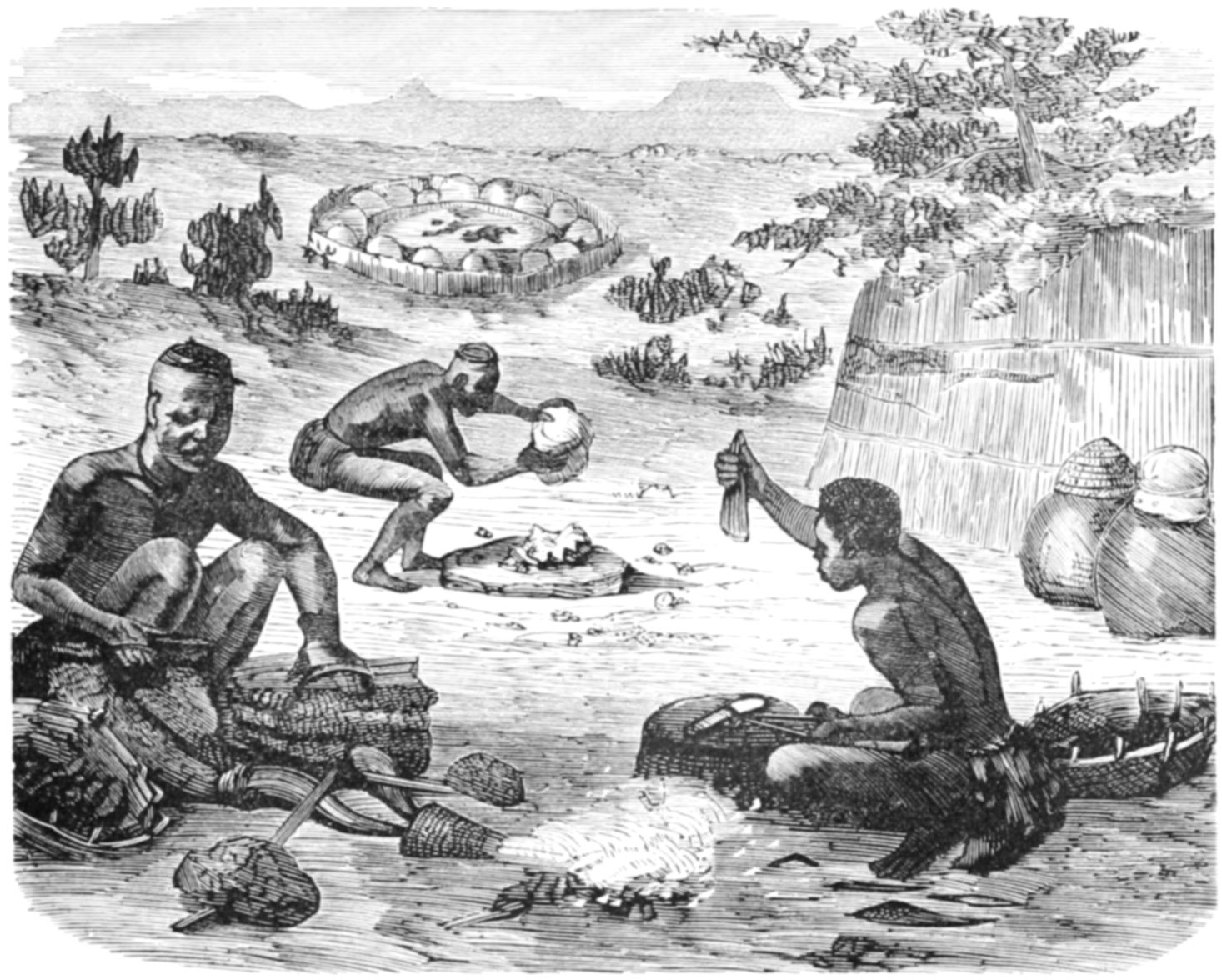

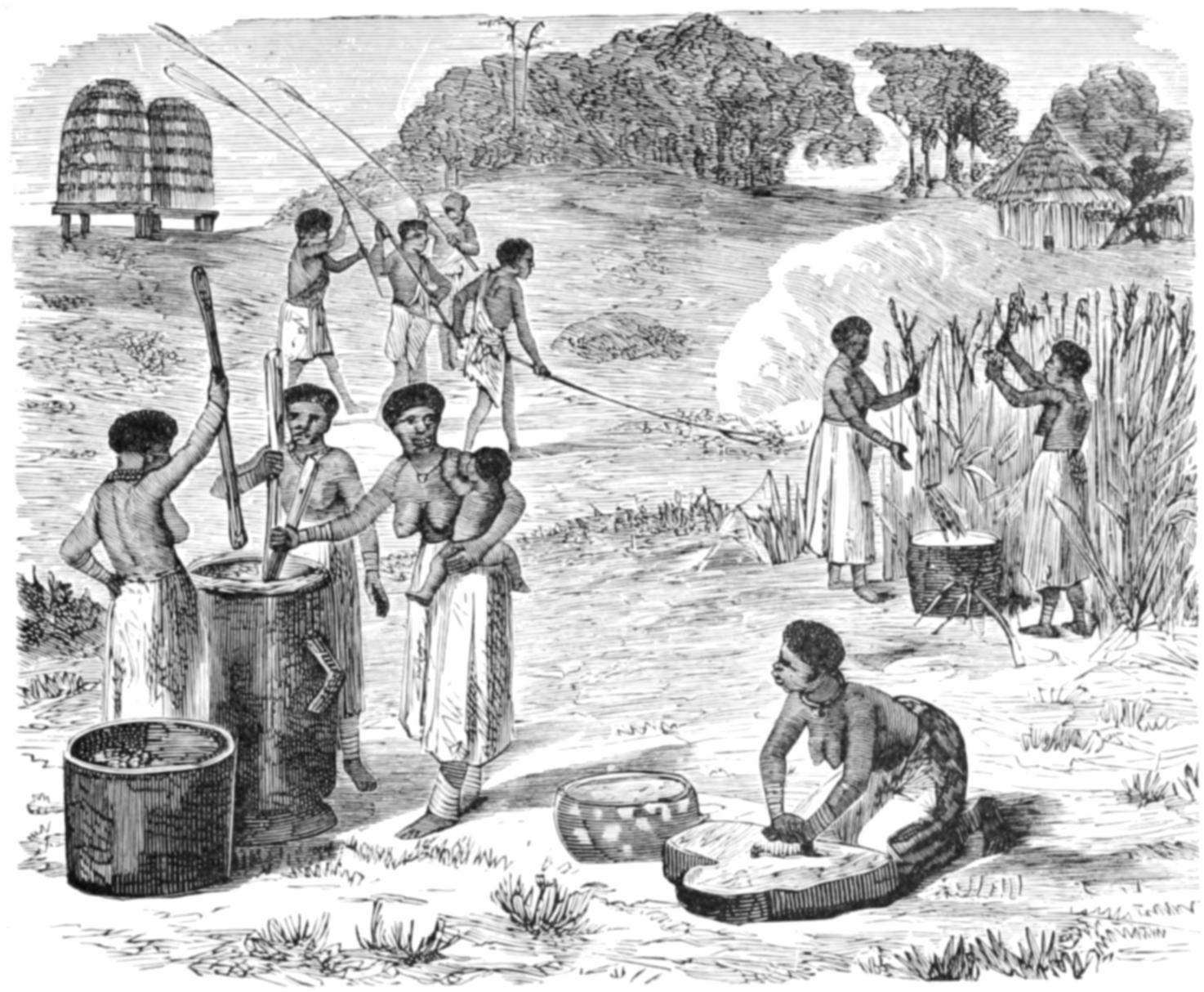

| 114. | Harvest scene among the Wanyamuezi | 397 |

| 115. | Salutation by the Watusi | 397 |

| 116. | Rumanika’s private band | 404 |

| 117. | Arrest of the queen | 412 |

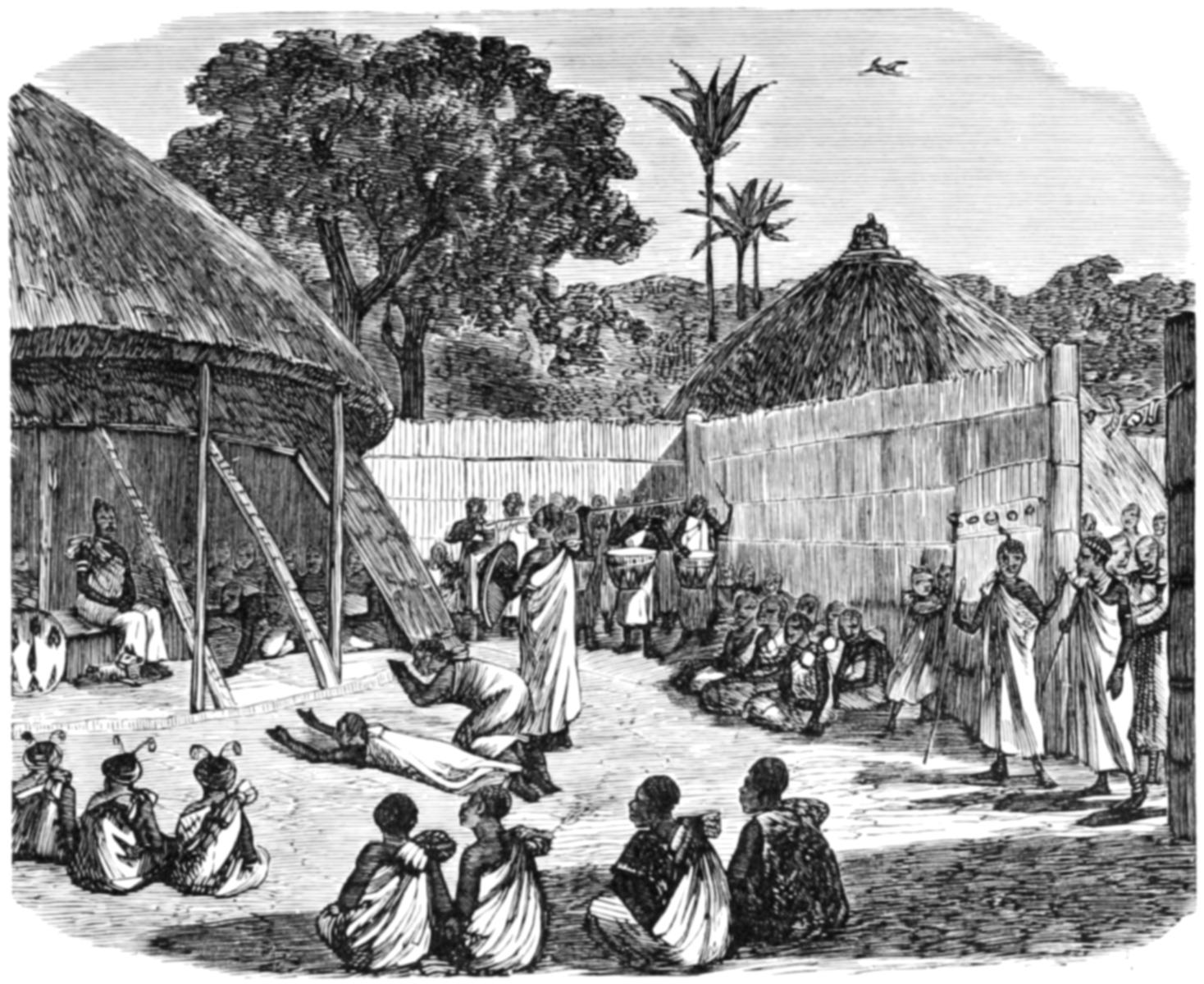

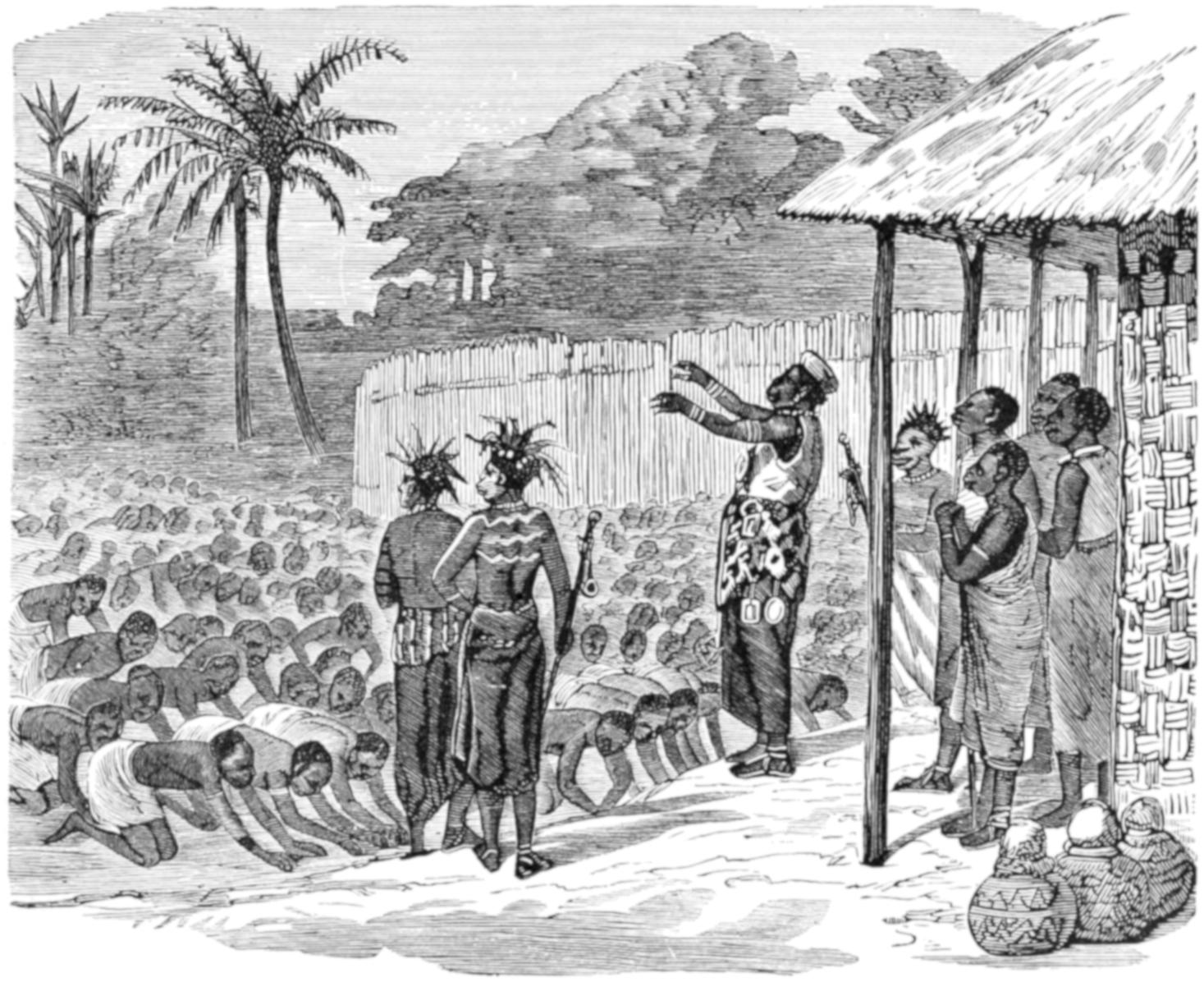

| 118. | Reception of a visitor by the Waganda | 417 |

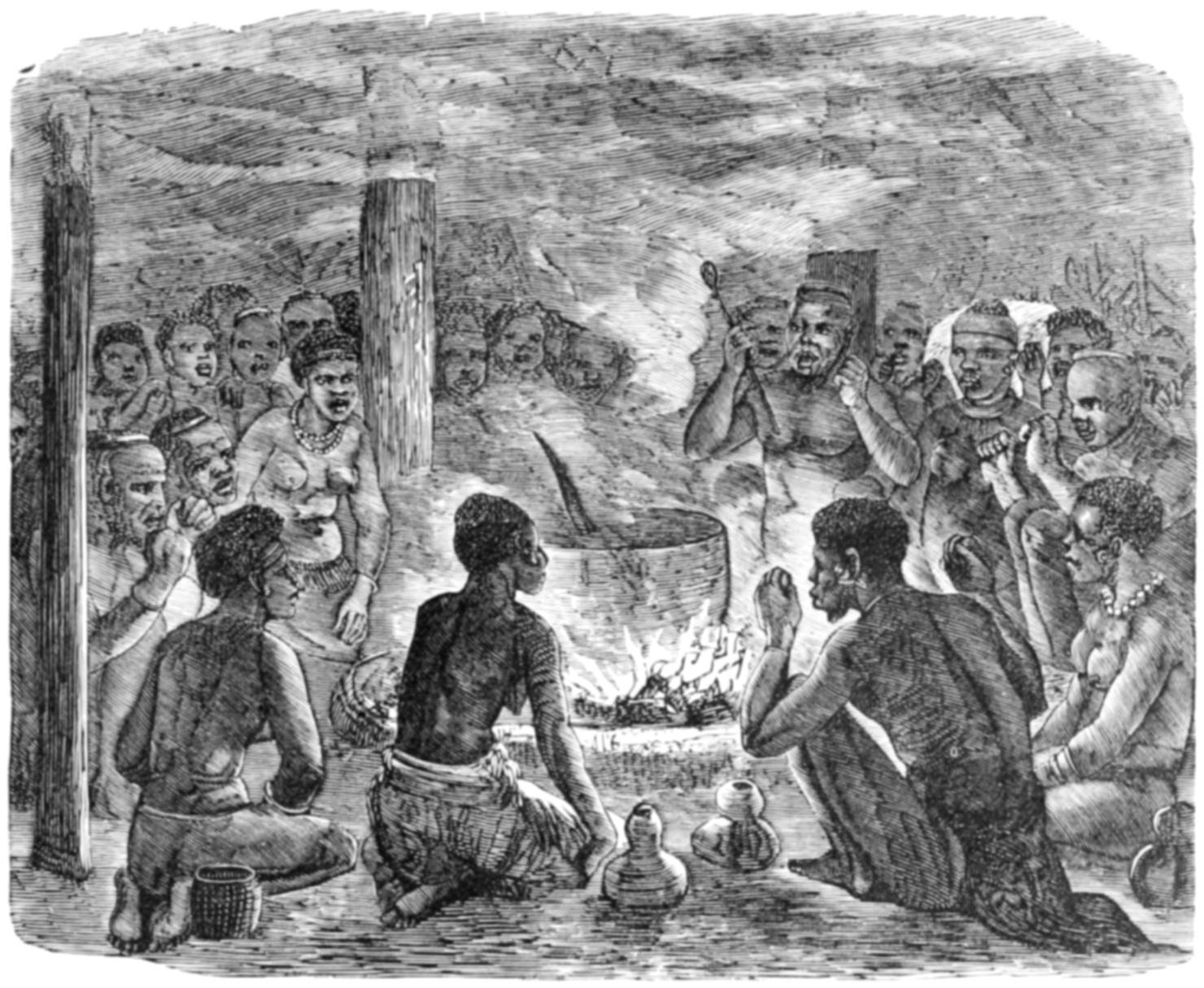

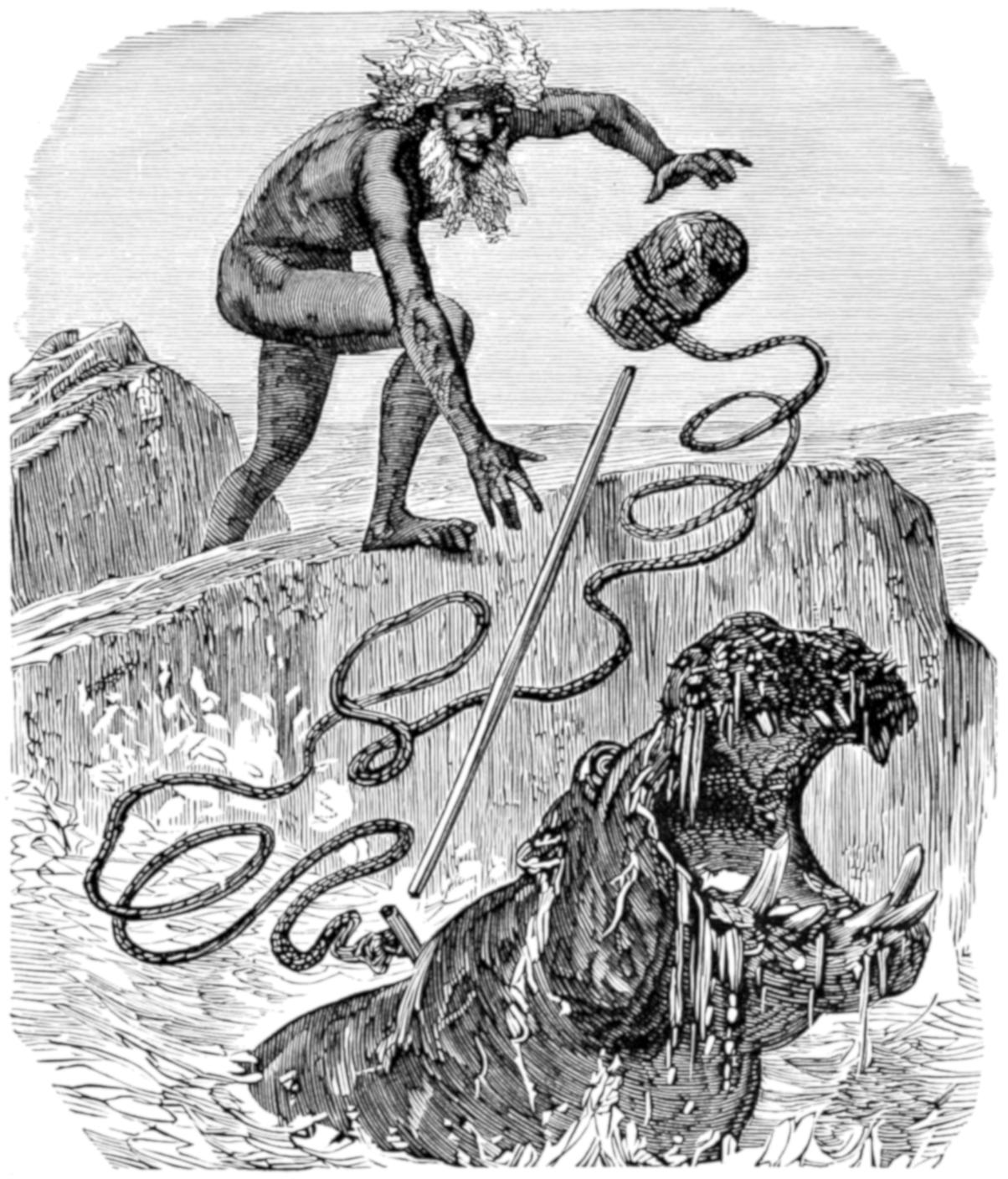

| 119. | The magician of Unyoro at work | 417 |

| 120. | Wanyoro culprit in the shoe | 423 |

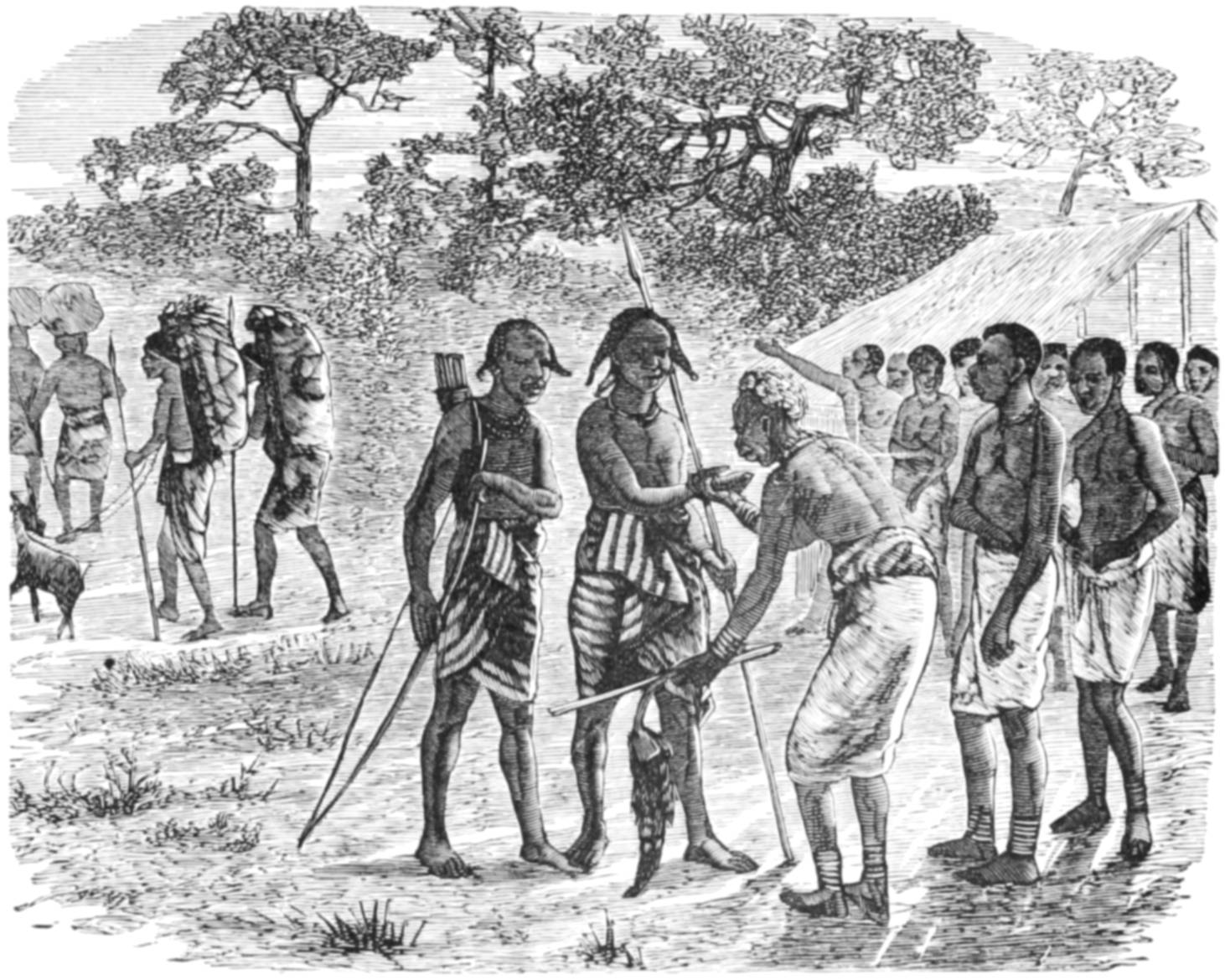

| 121. | Group of Gani and Madi | 431 |

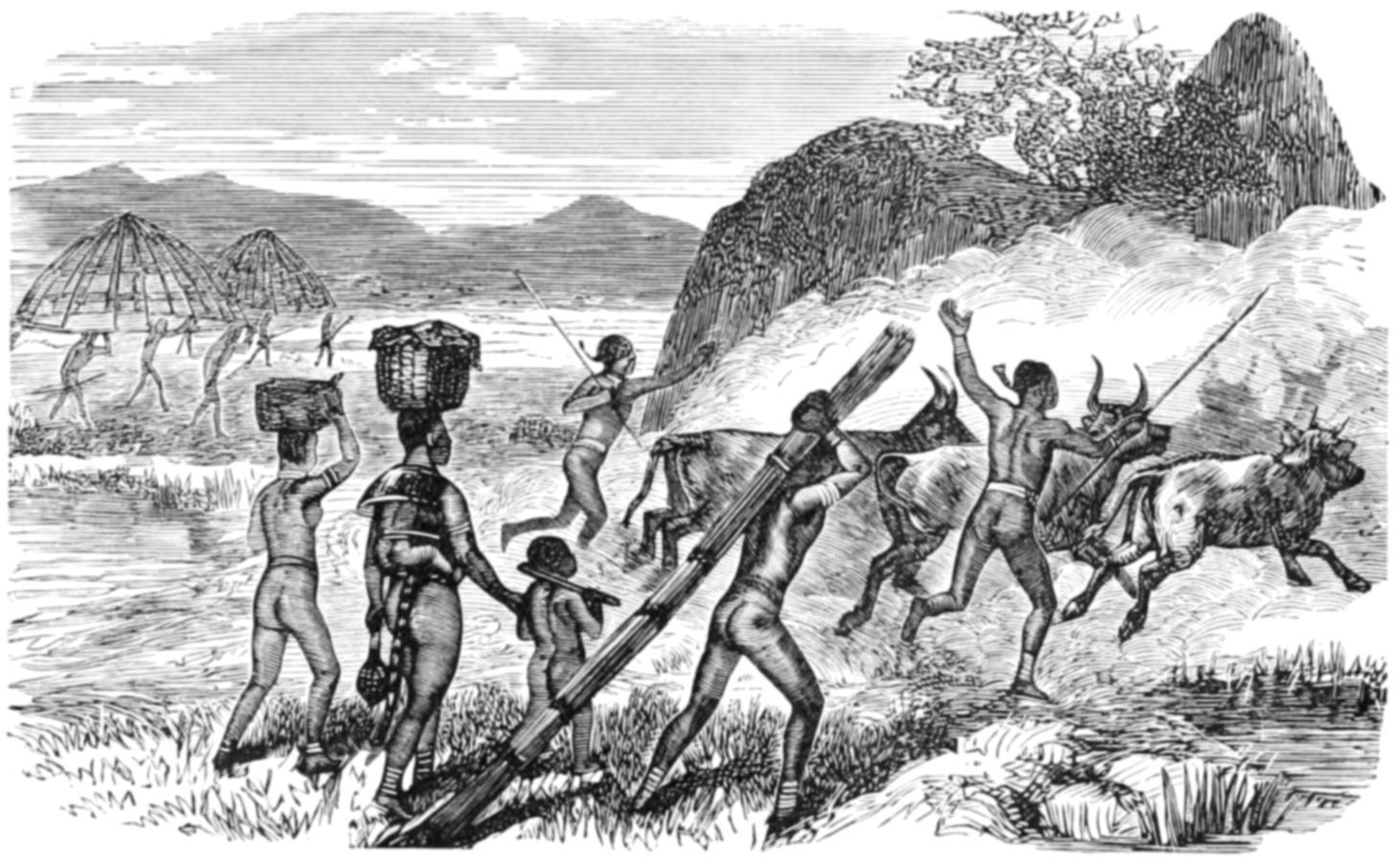

| 122. | Removal of a village by Madi | 431 |

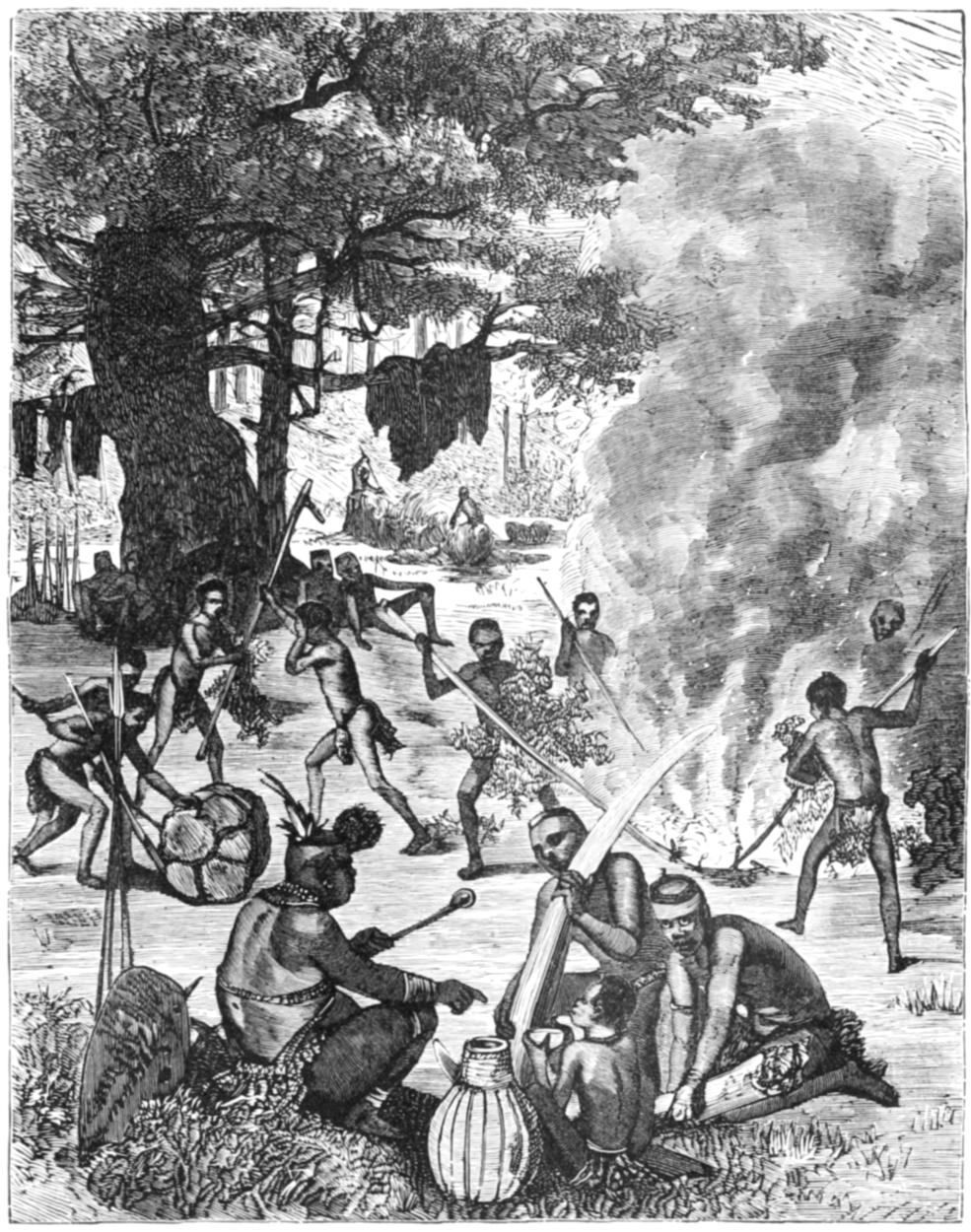

| 123. | Group of the Kytch tribe | 437 |

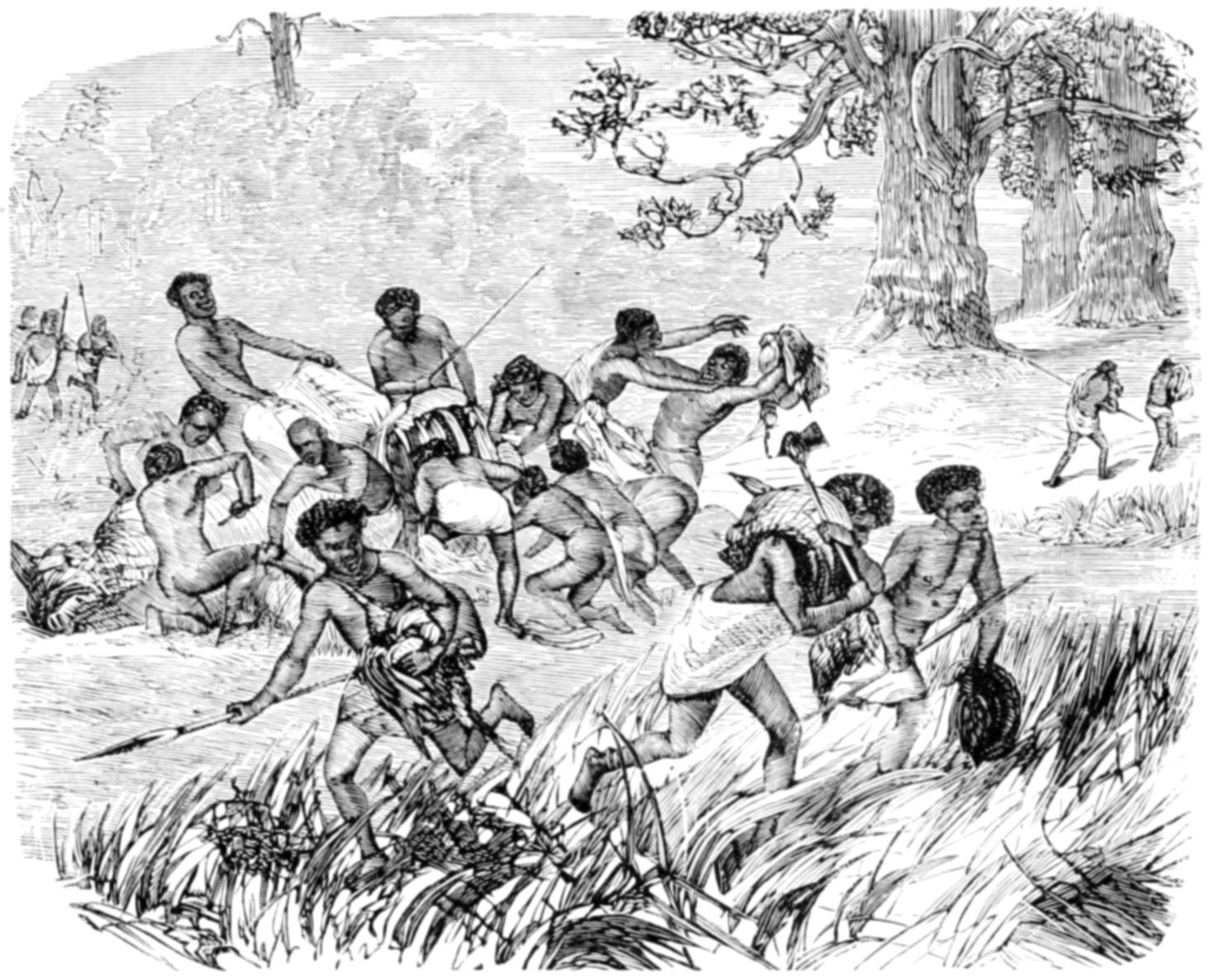

| 124. | Neam-Nam fighting | 437 |

| 125. | Wooden chiefs of the Dôr | 449 |

| 126. | Scalp-locks of the Djibbas | 449 |

| 127. | Bracelets of the Djibbas | 449 |

| 128. | Ornaments of the Djour | 449 |

| 129. | Women’s knives | 449 |

| 130. | A Nuehr helmet | 449 |

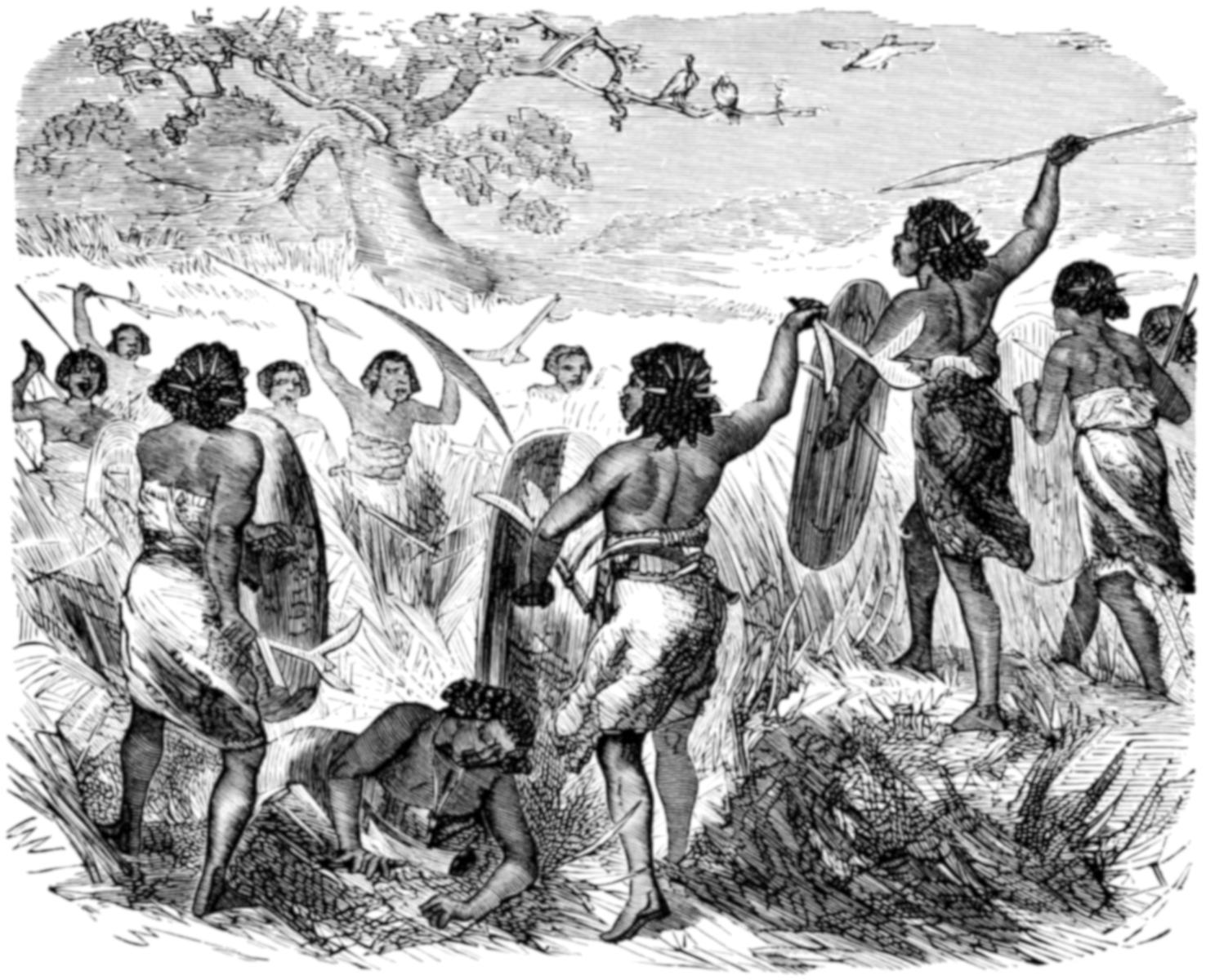

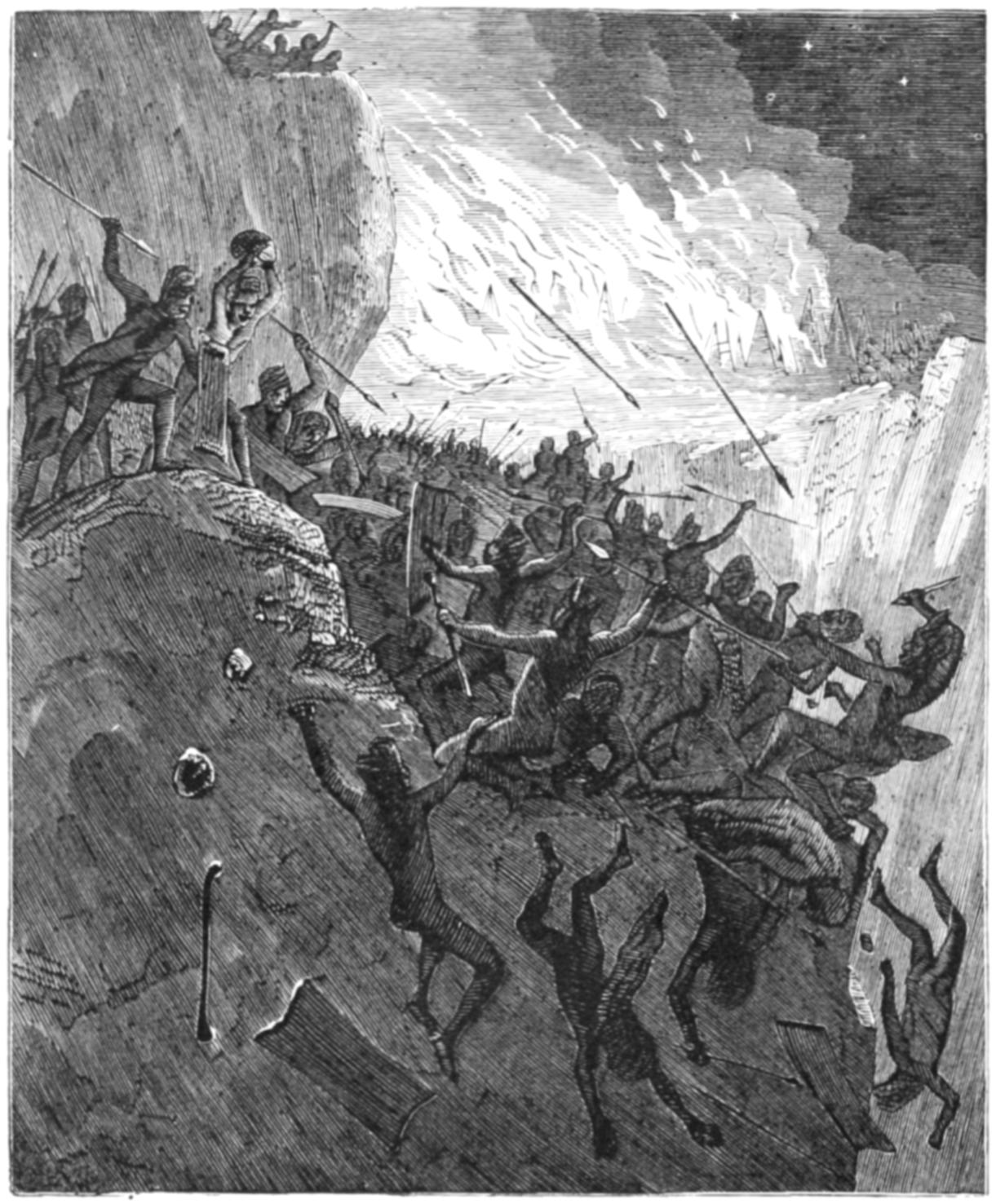

| 131. | The Latooka victory | 457 |

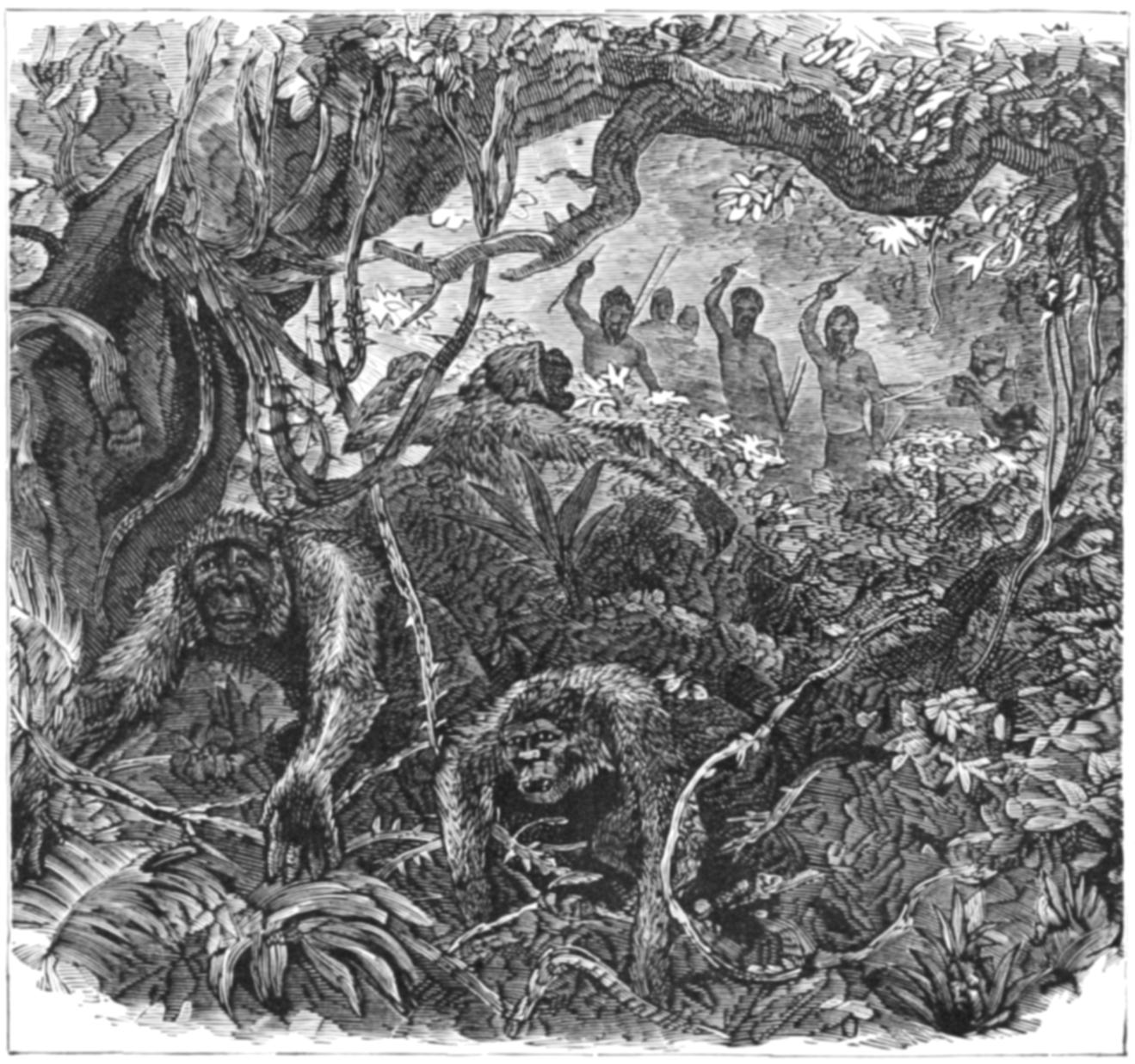

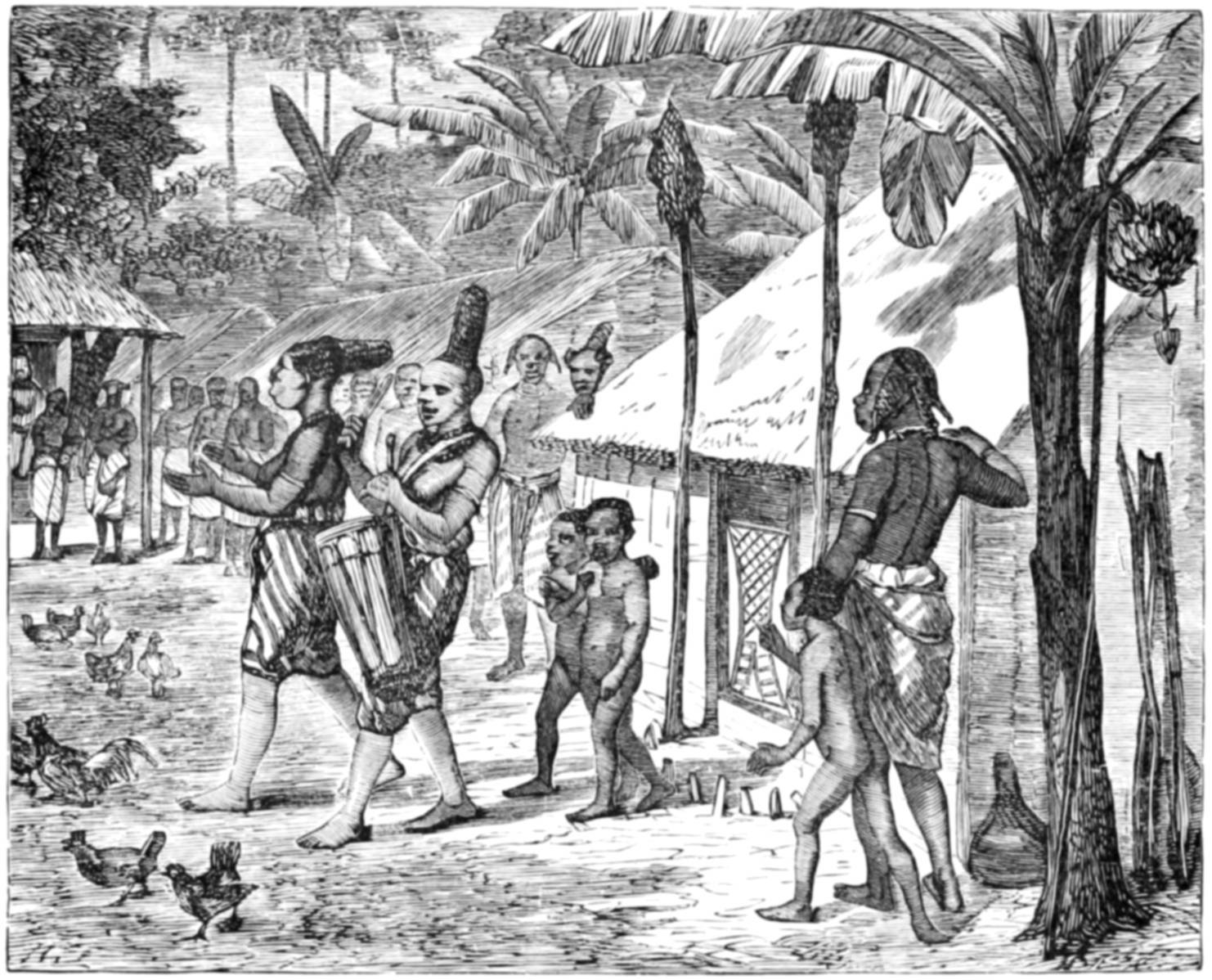

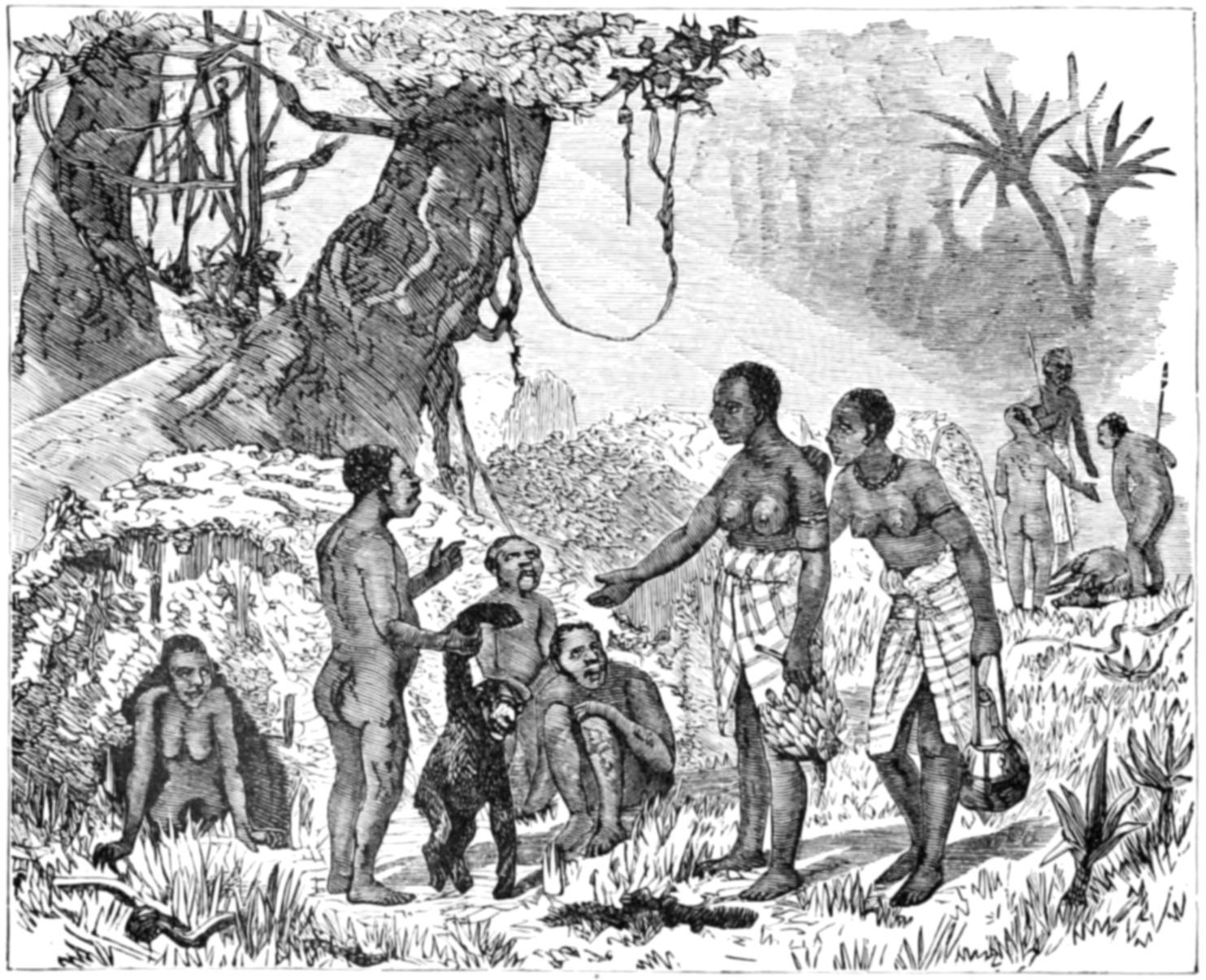

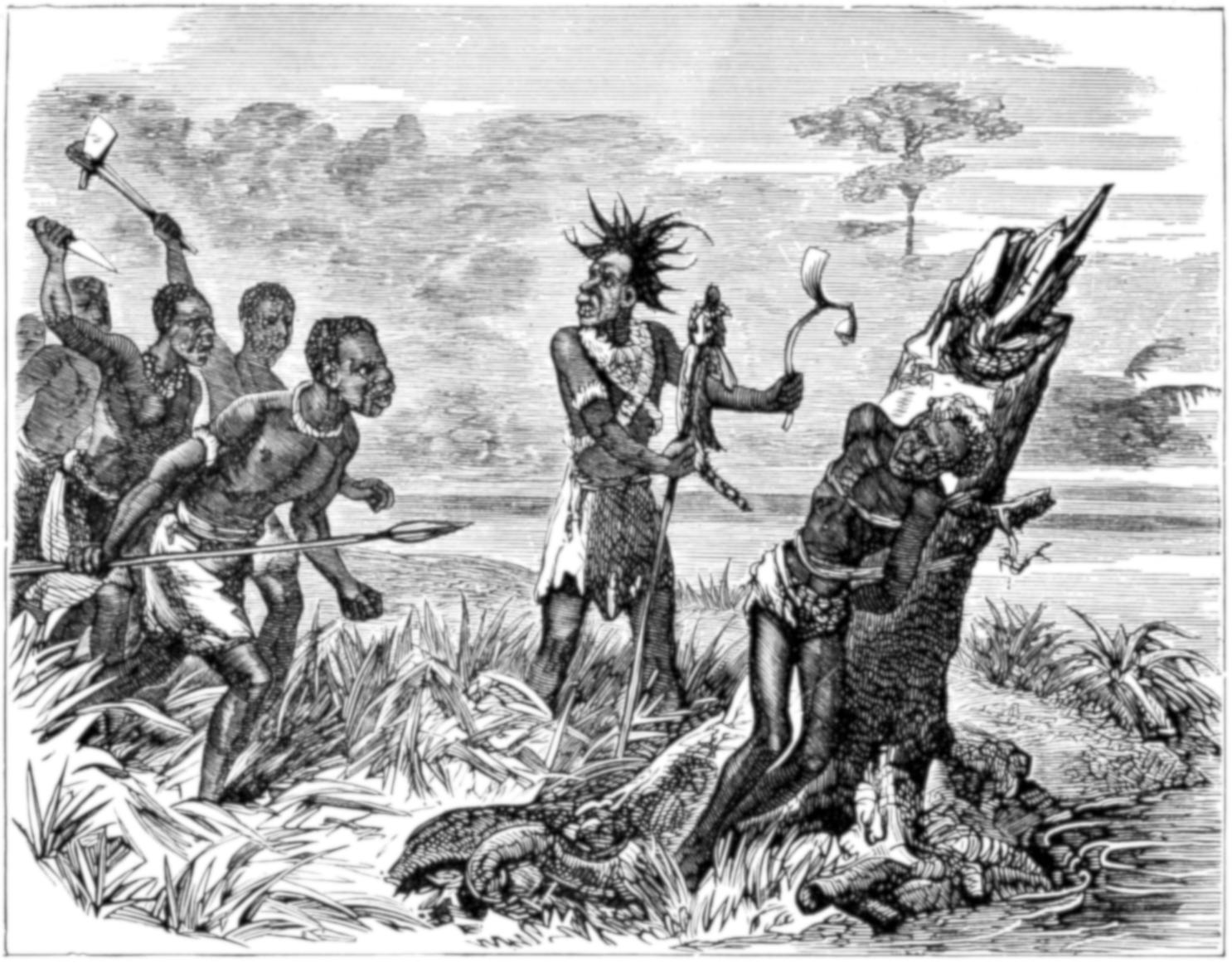

| 132. | Gorilla hunting by the Fans | 457 |

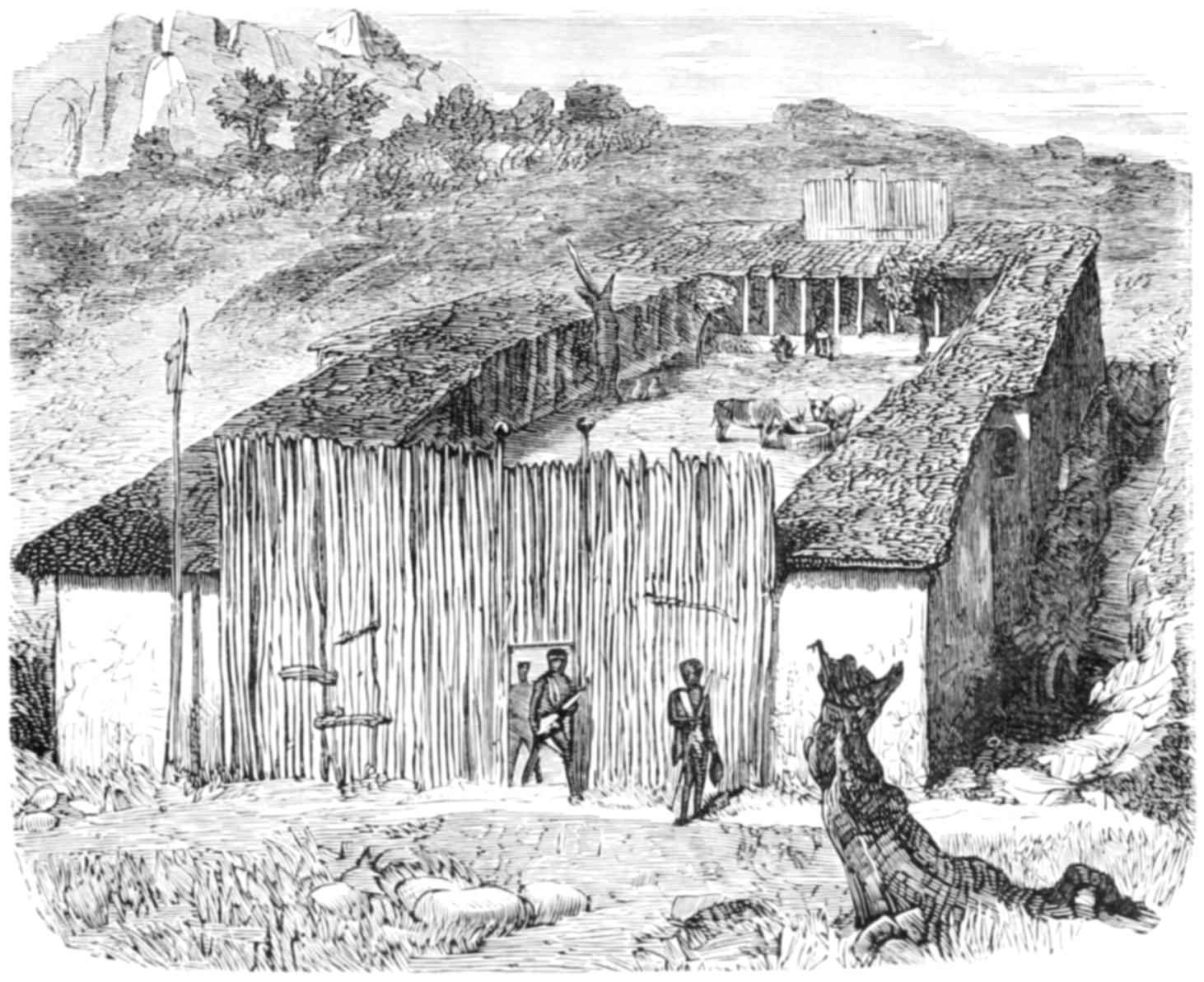

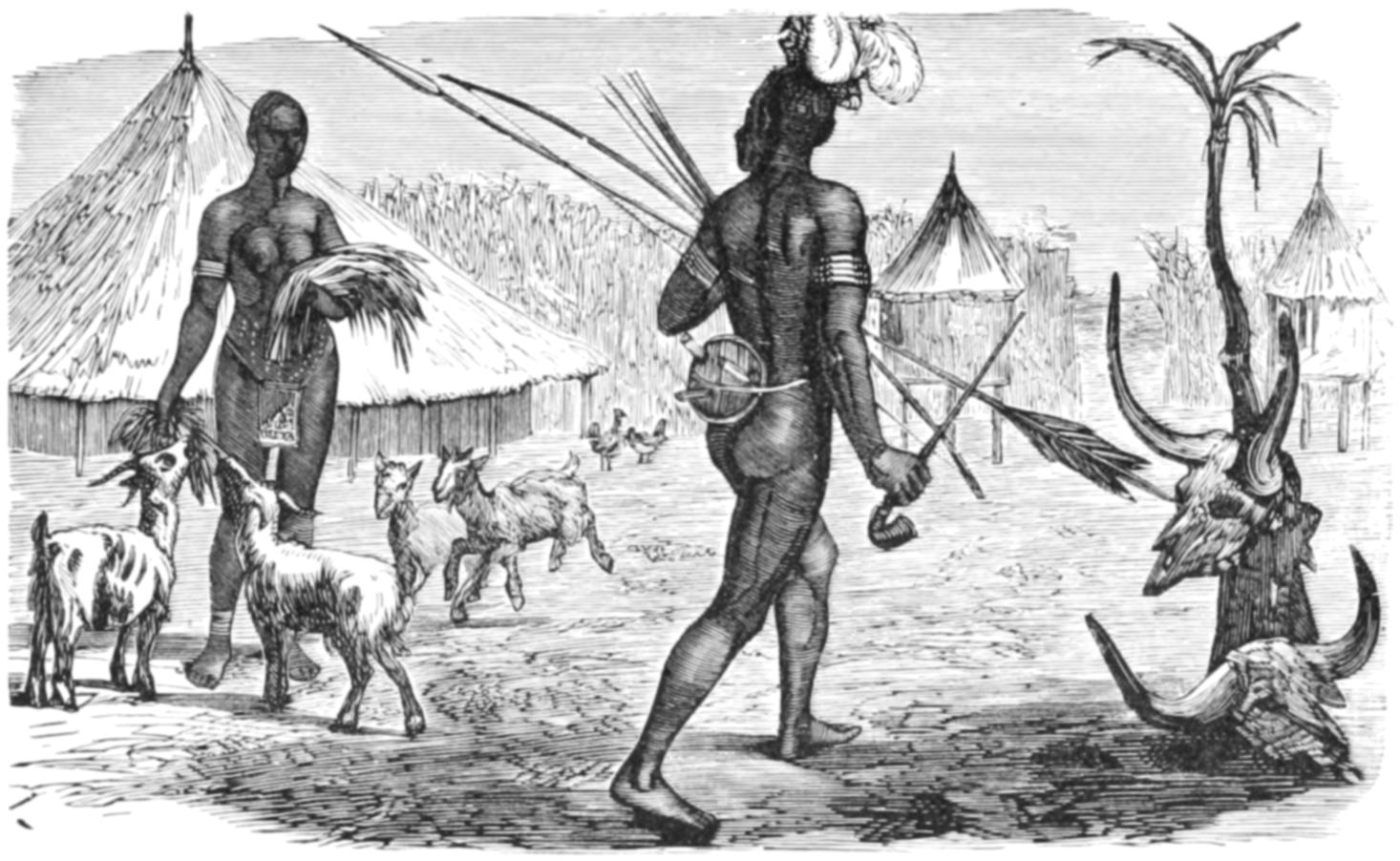

| 133. | A Bari homestead | 465 |

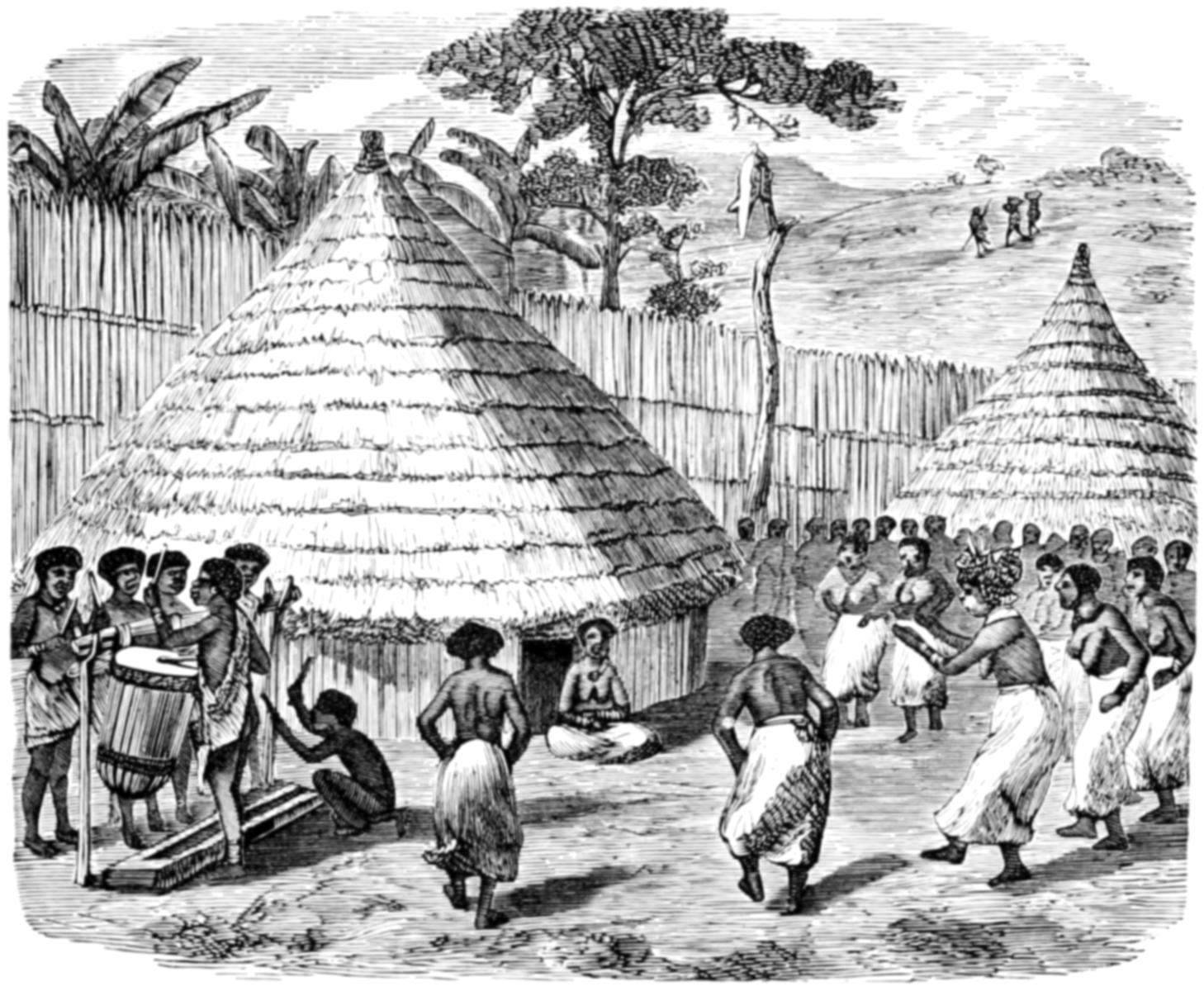

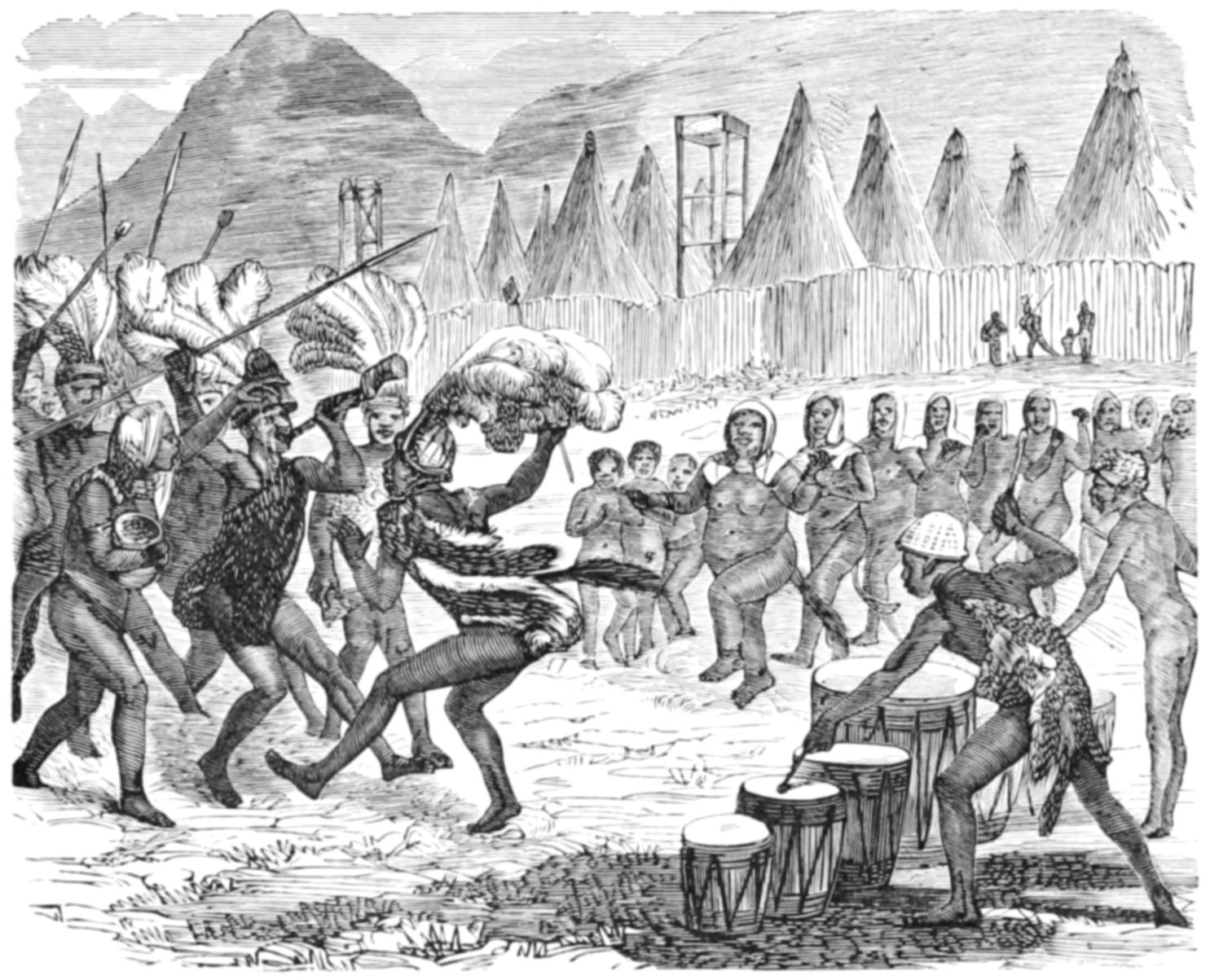

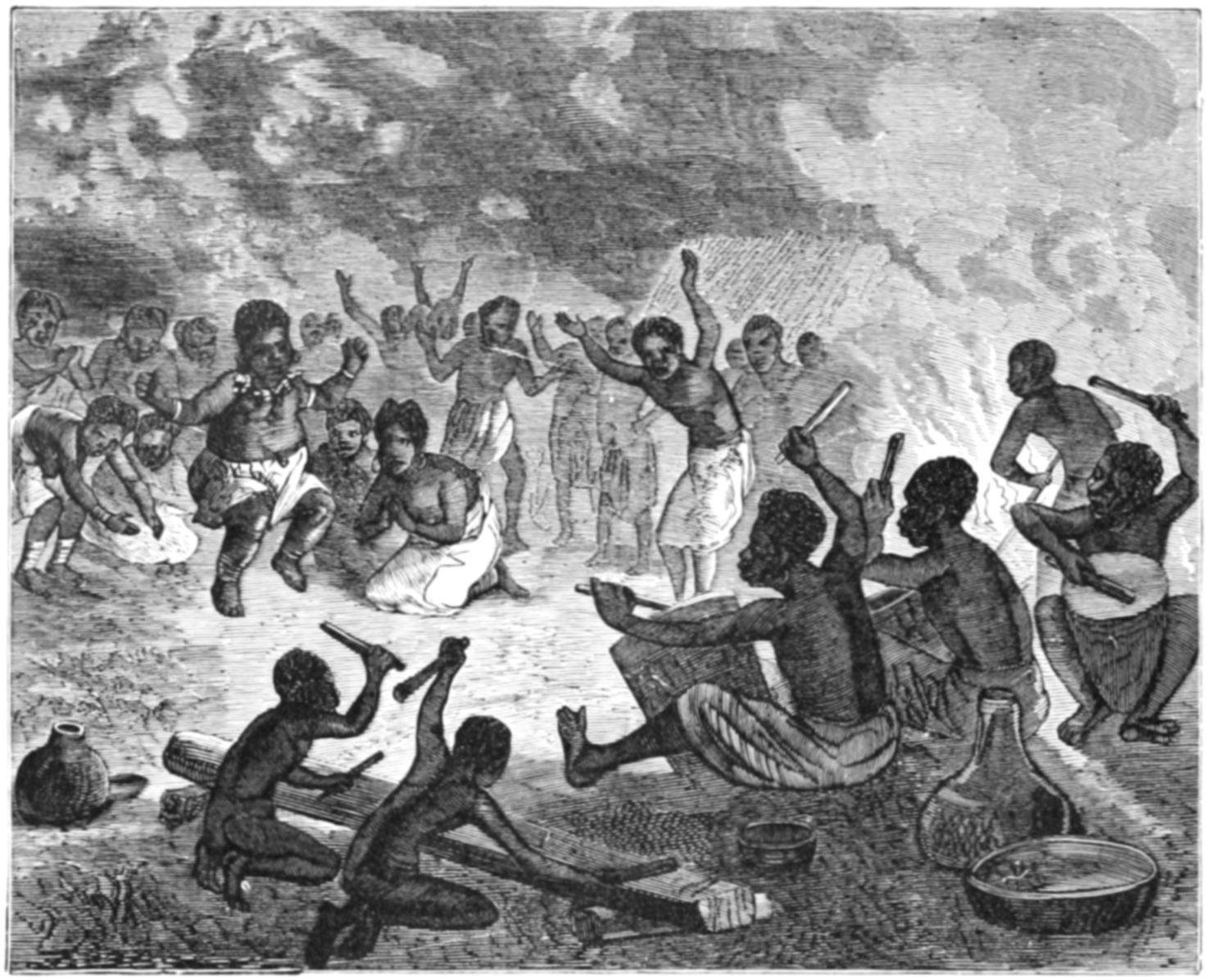

| 134. | Funeral dance of the Latookas | 465 |

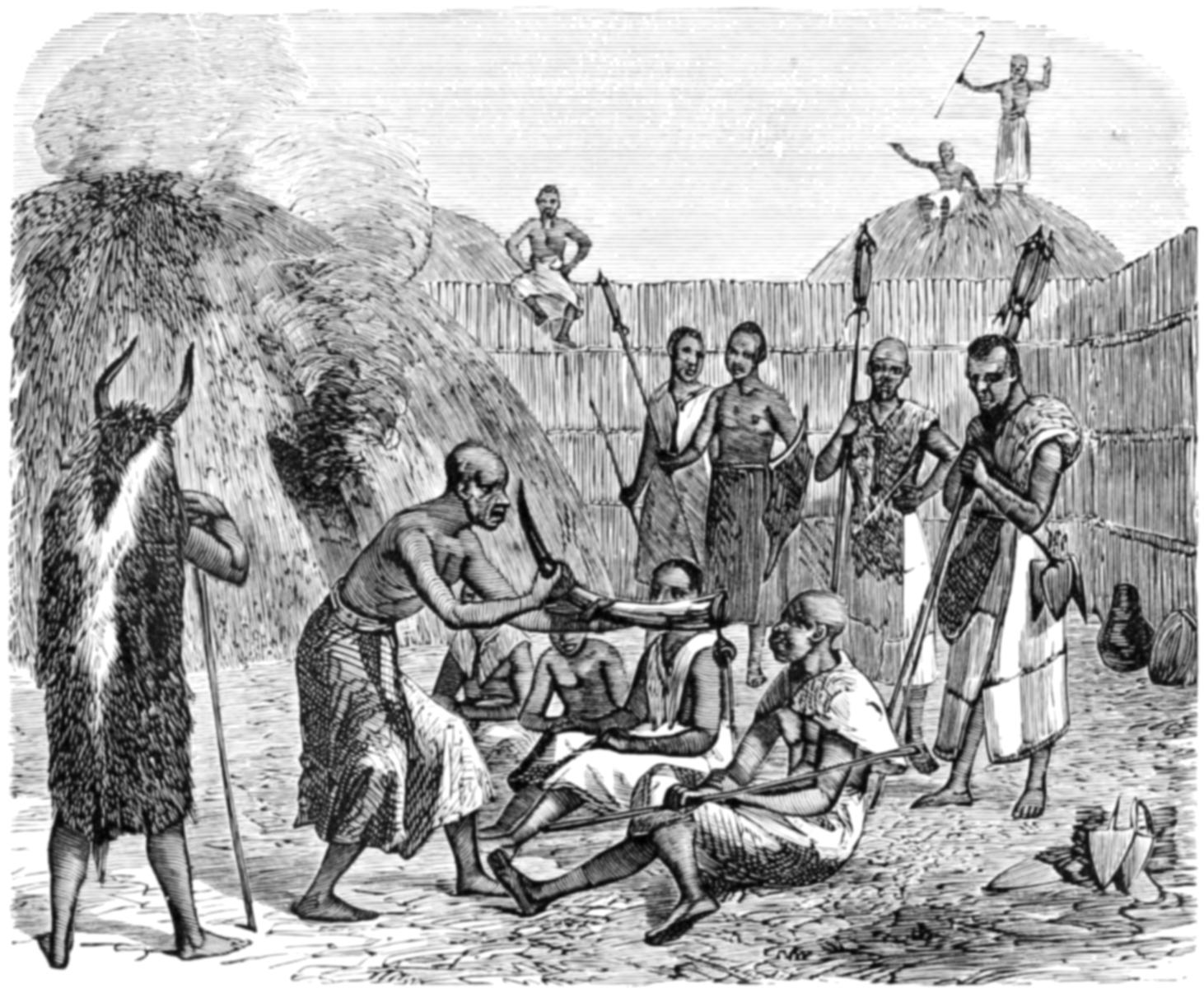

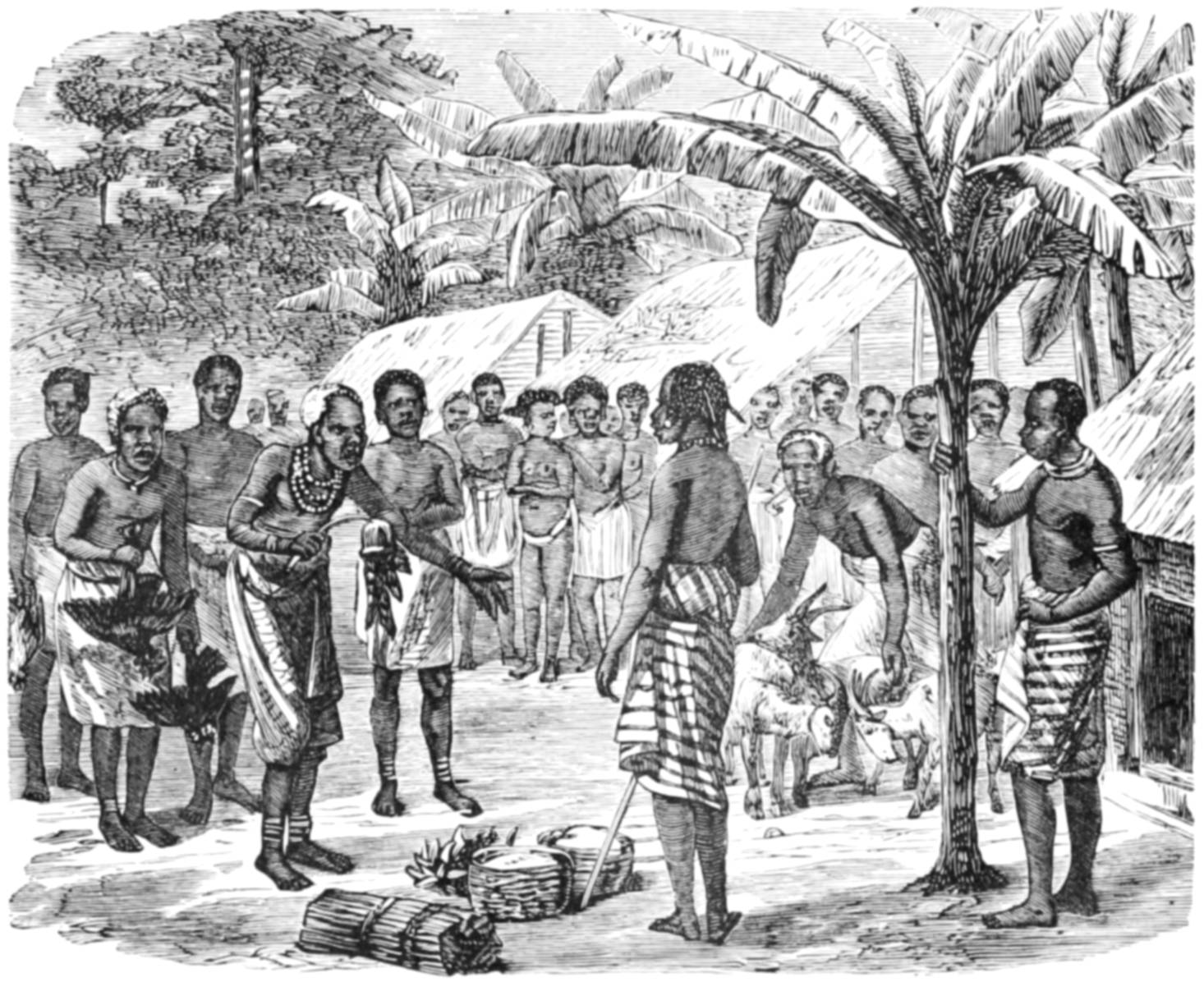

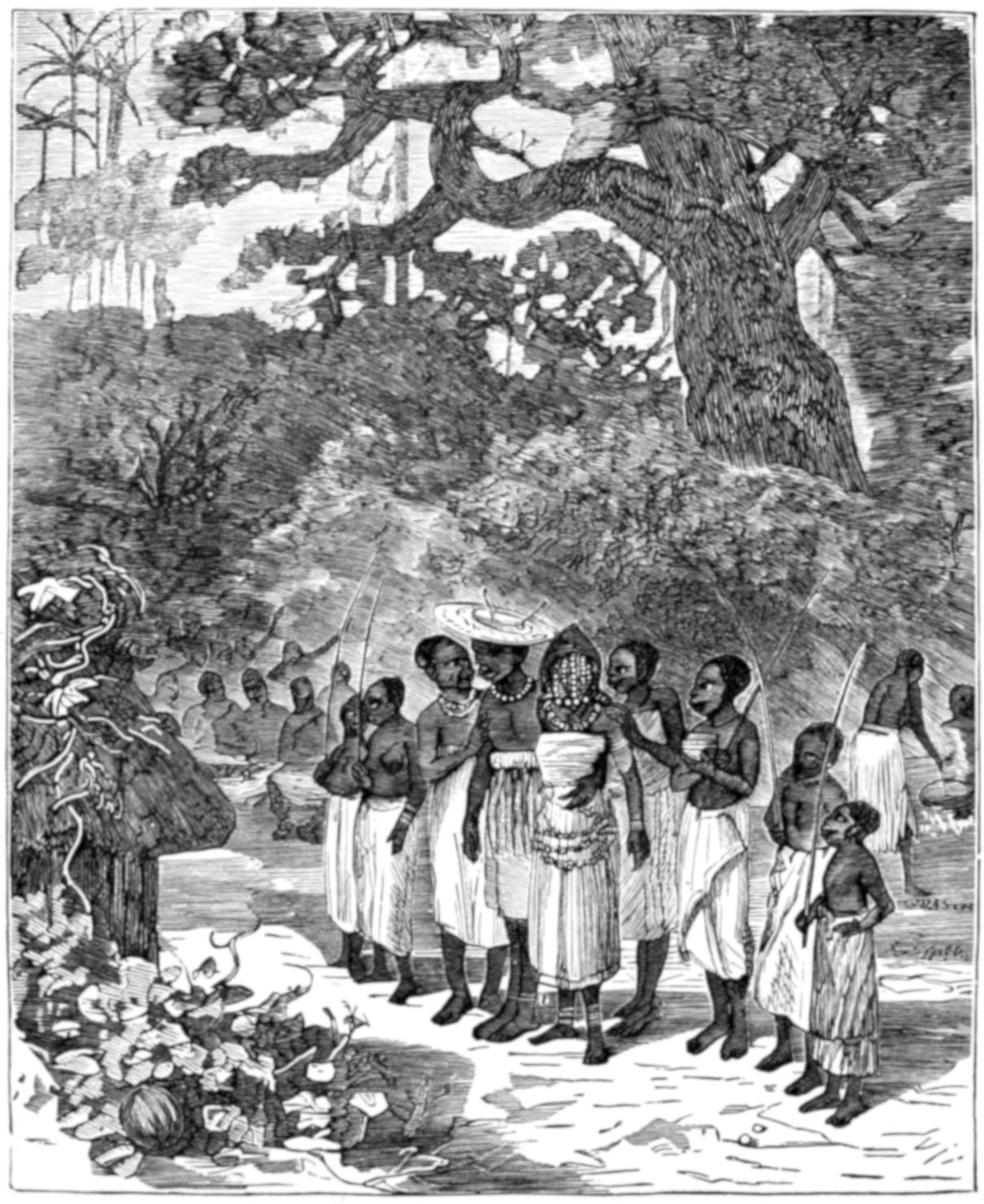

| 135. | The ceremony of M’paza | 478 |

| 136. | Obongo market | 478 |

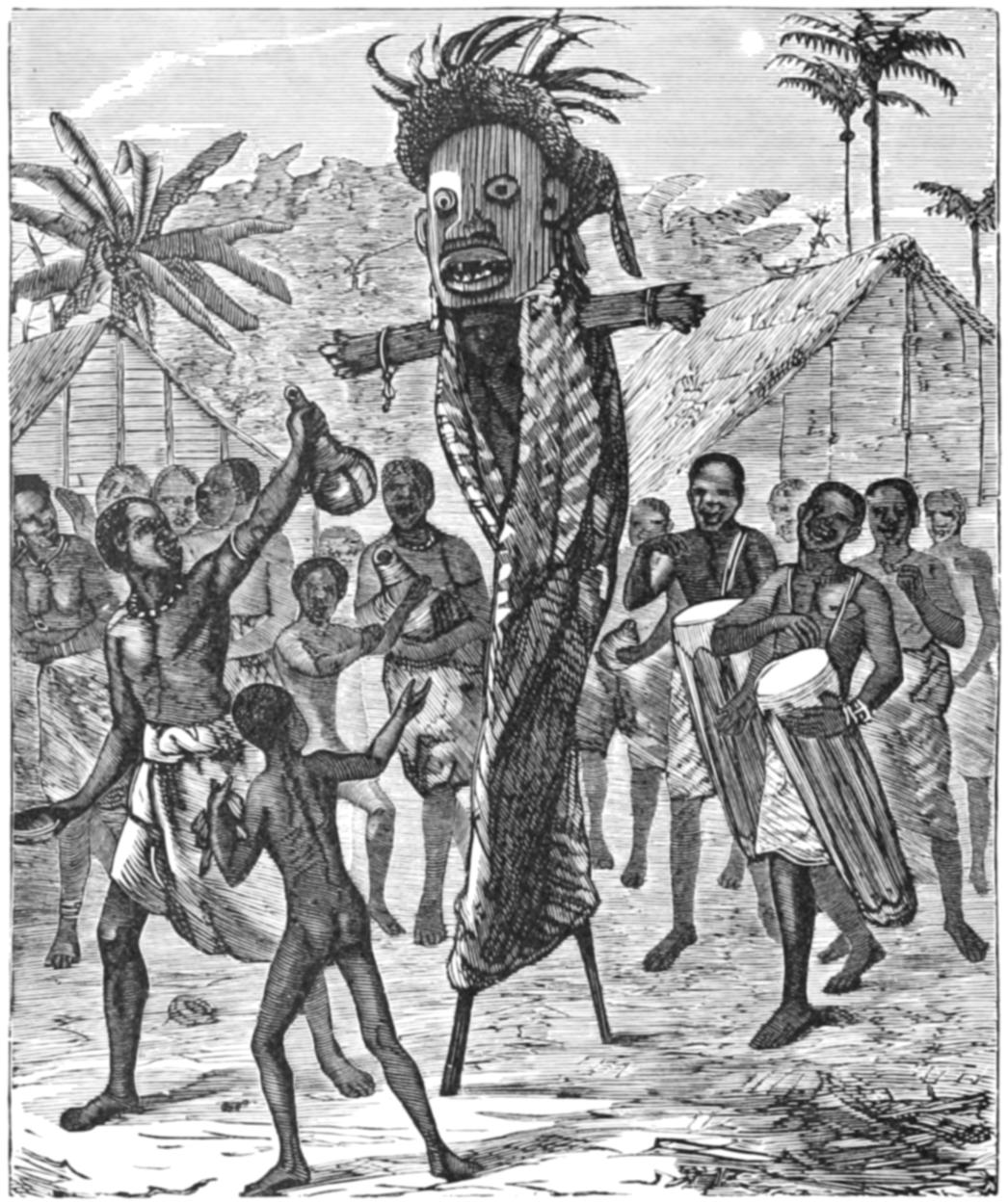

| 137. | The giant dance of the Aponos | 486 |

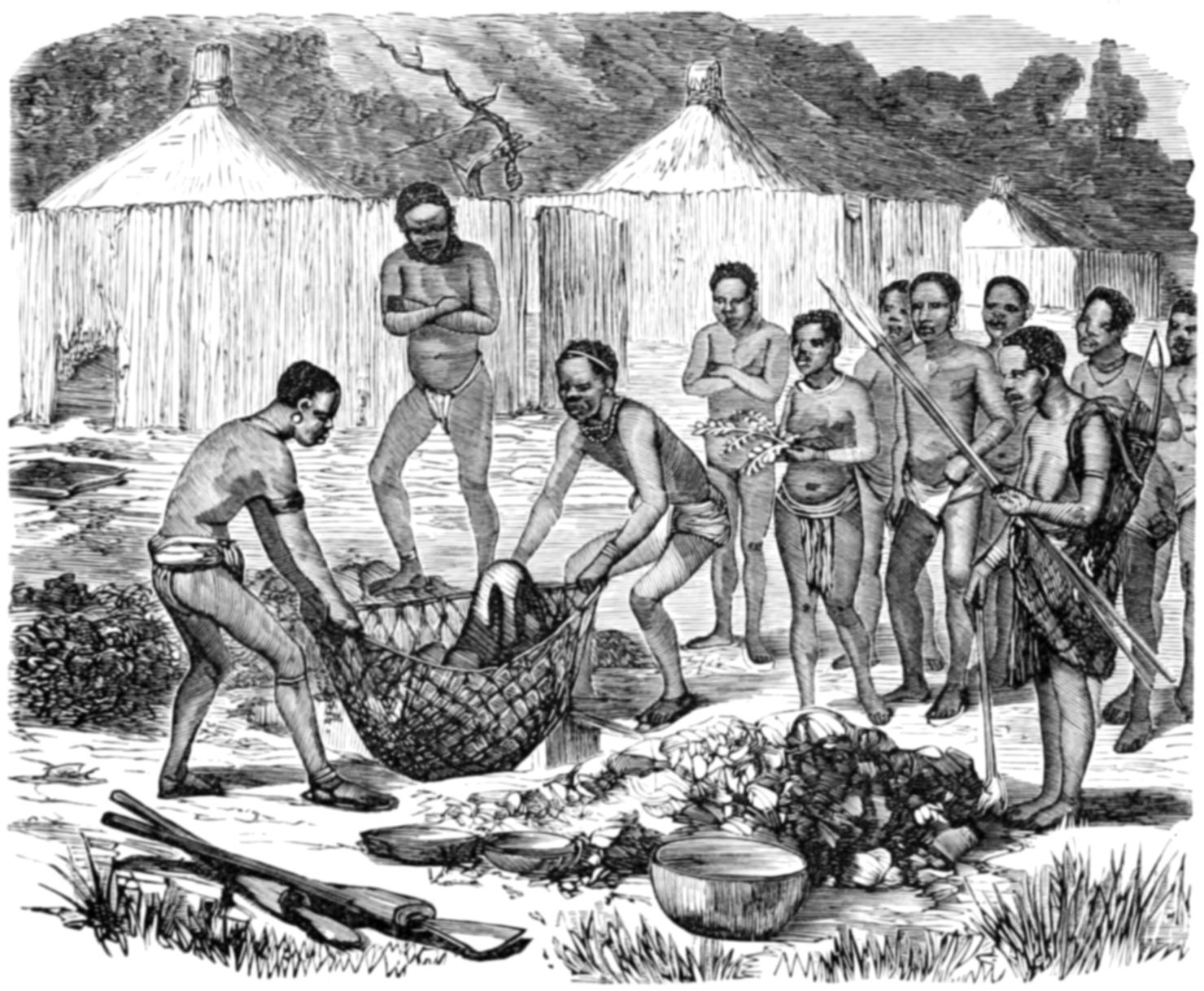

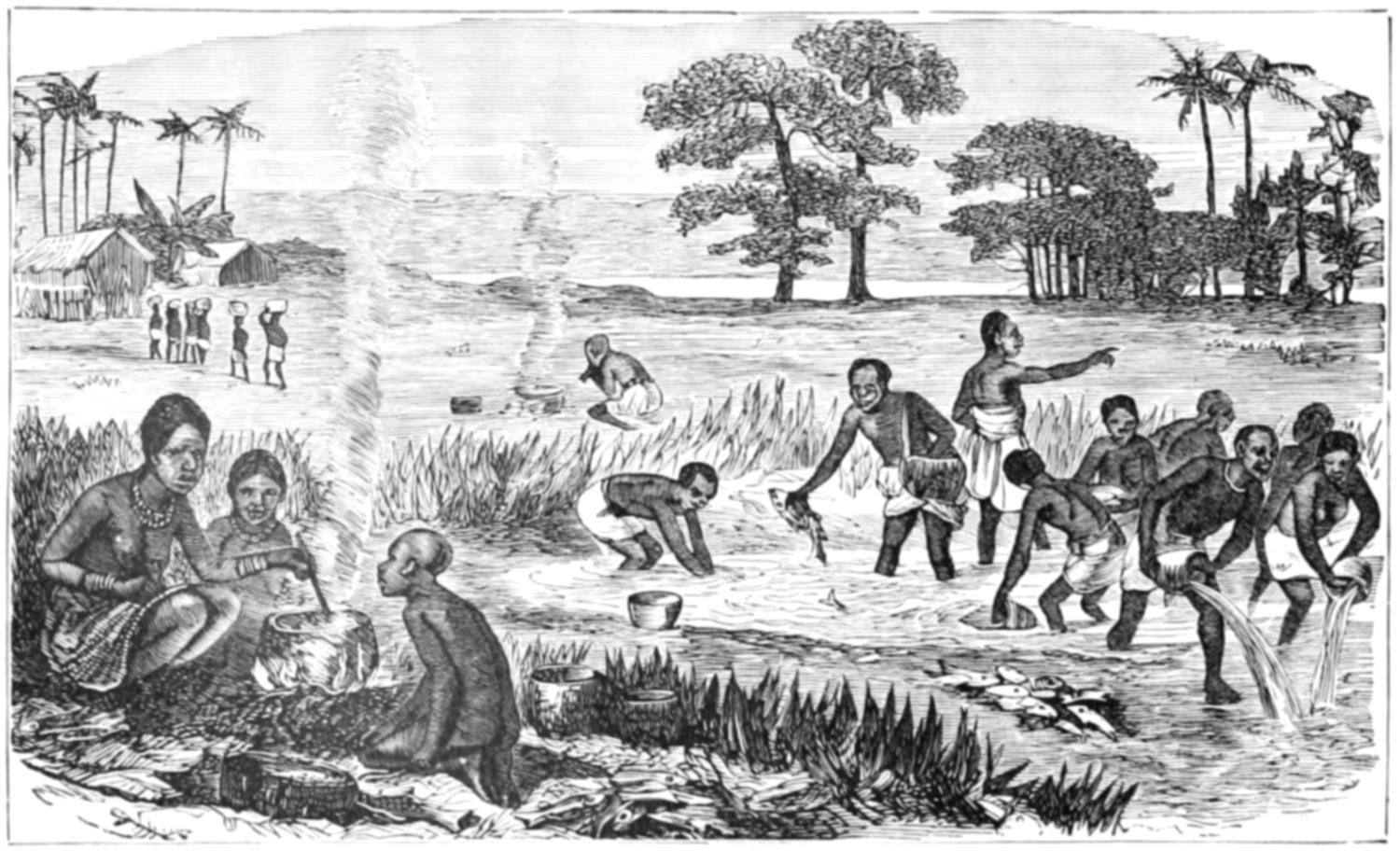

| 138. | Fishing scene among the Bakalai | 486 |

| 139. | Ashira farewell | 499 |

| 140. | Olenda’s salutation to an Ishogo chief | 499 |

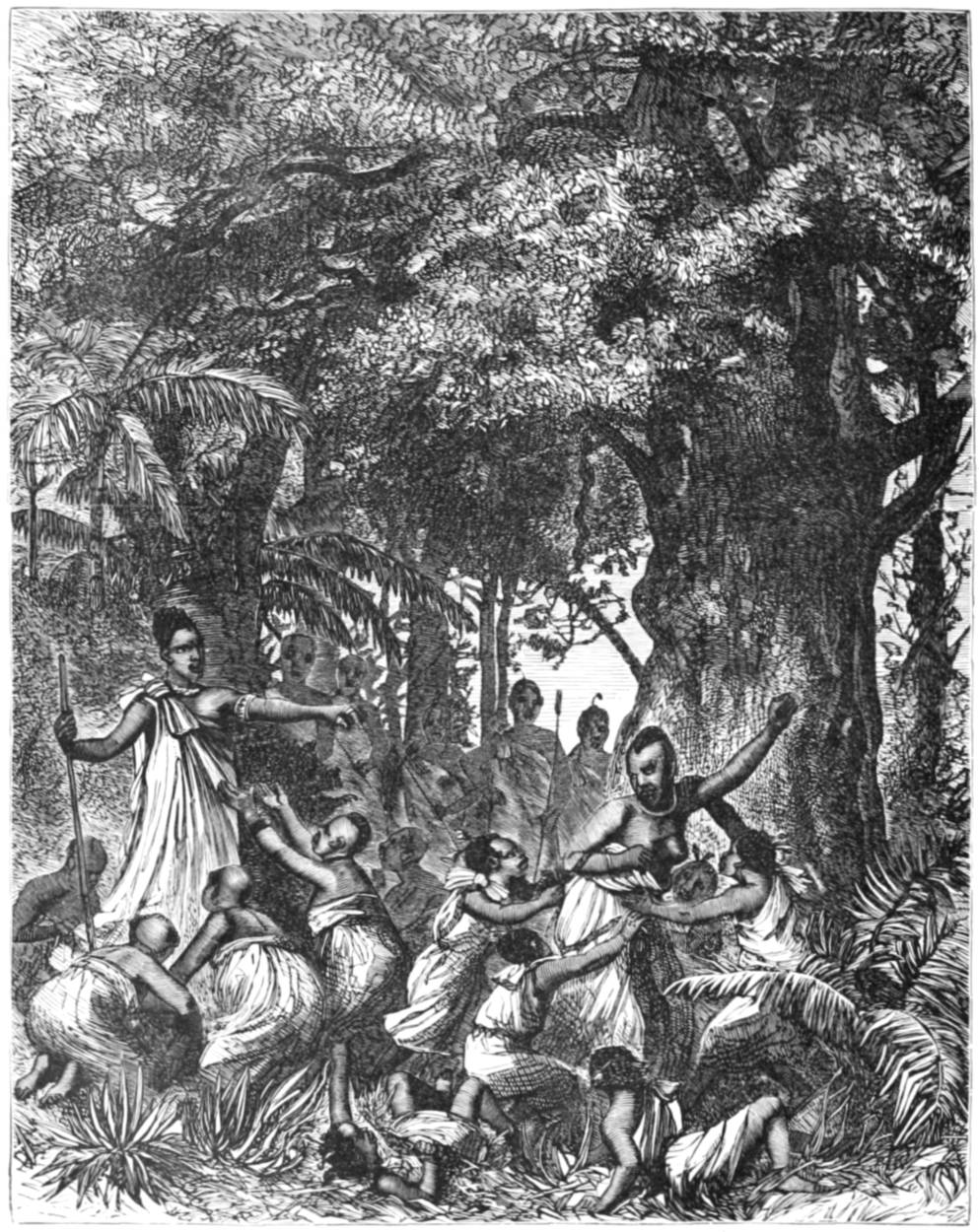

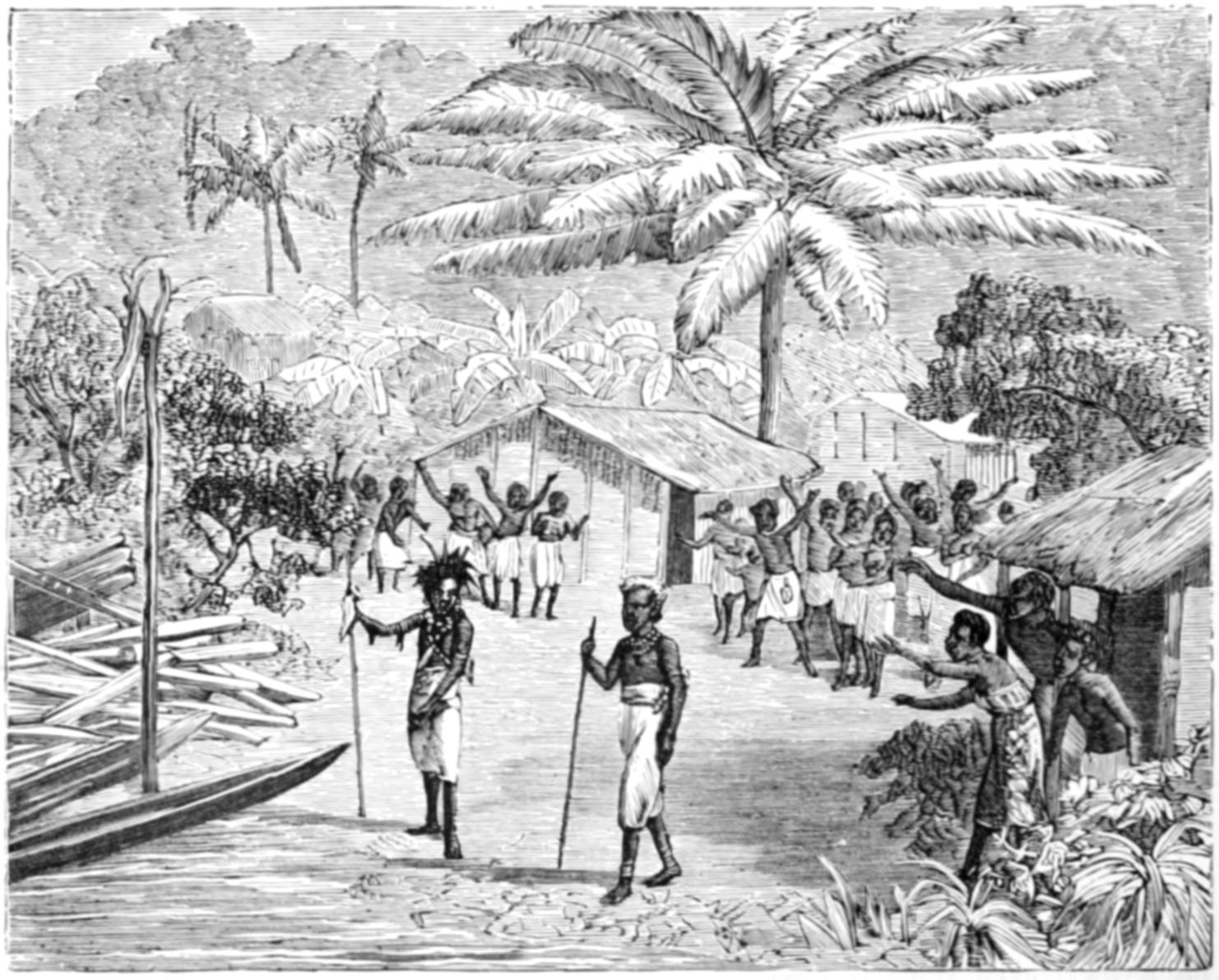

| 141. | A Camma dance | 508 |

| 142. | Quengueza’s (chief of the Camma) walk | 508 |

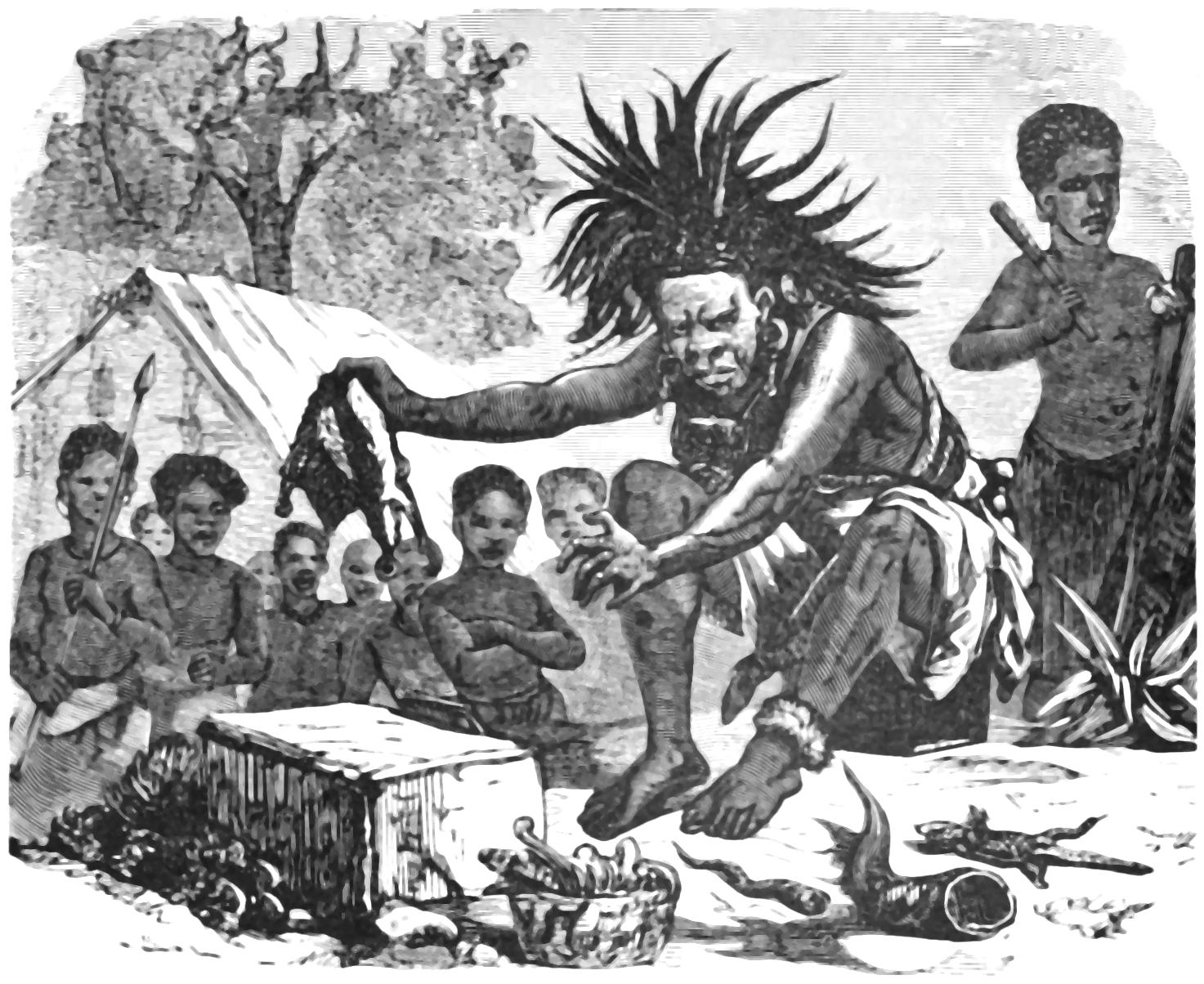

| 143. | The Camma fetish man ejecting a demon | 517 |

| 144. | Olanga drinking mboundou | 517 |

| 145. | Fate of the Shekiani wizard | 526 |

| 146. | The Mpongwé coronation | 526 |

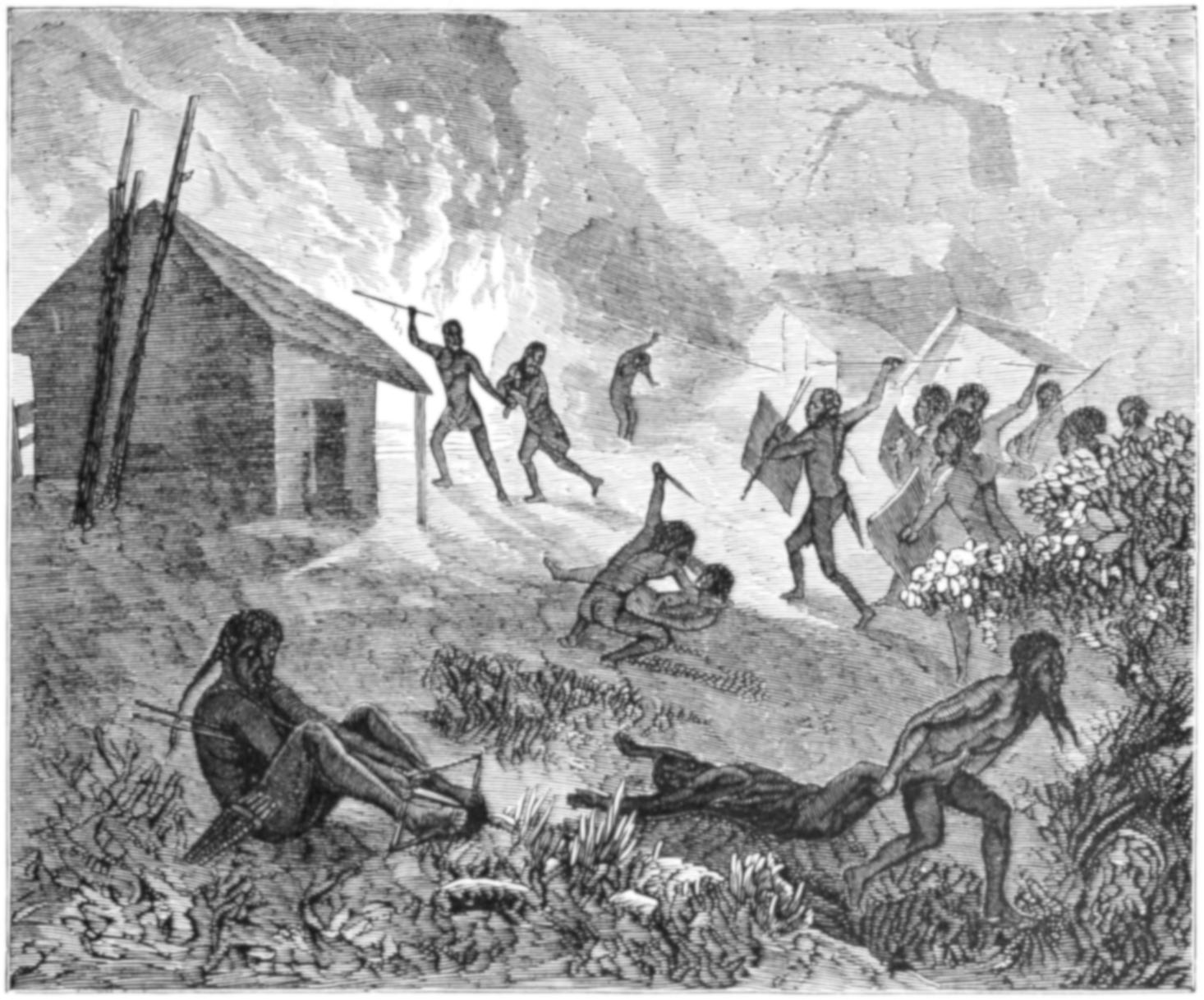

| 147. | Attack on a Mpongwé village | 537 |

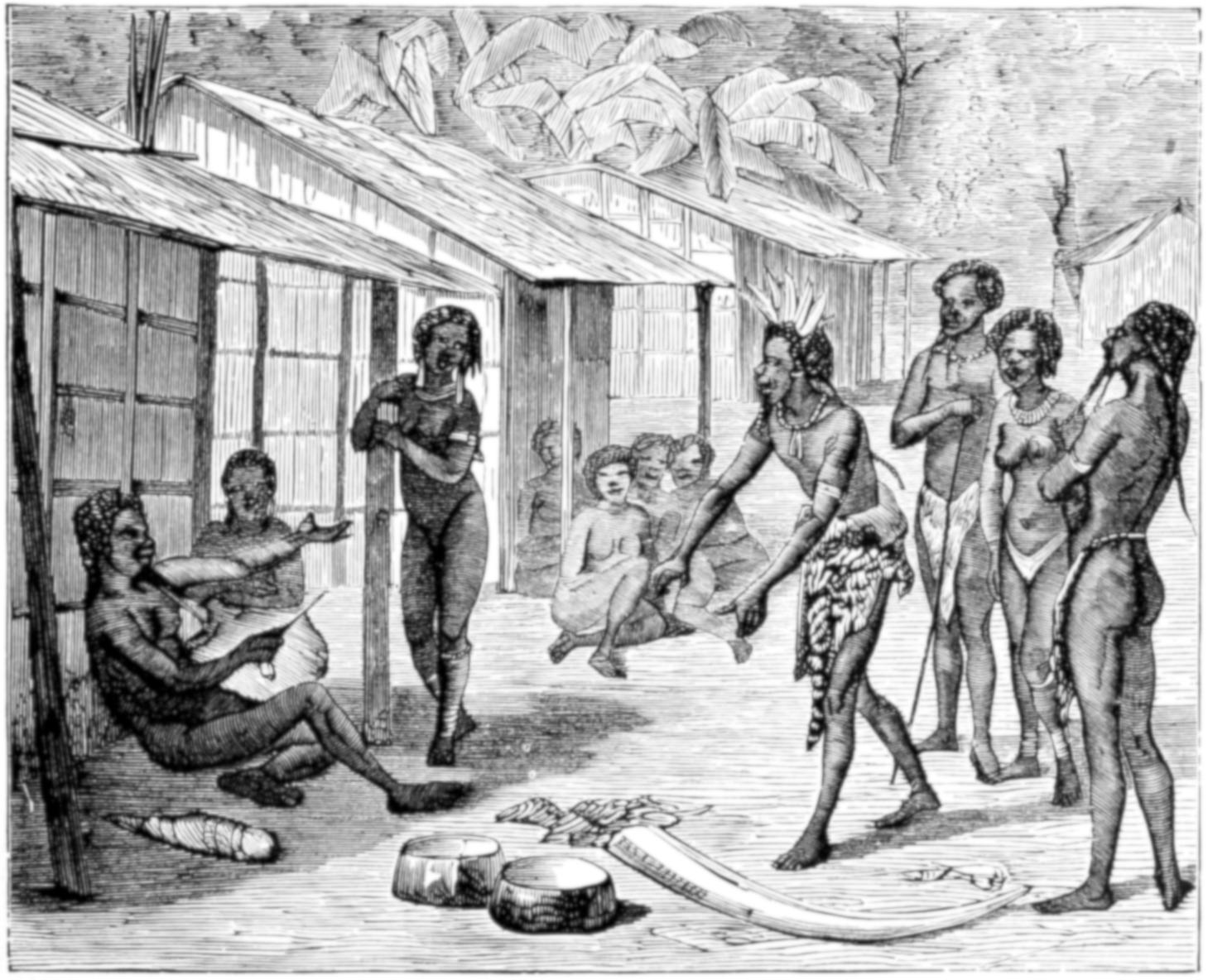

| 148. | Bargaining for a wife by the Fanti | 537 |

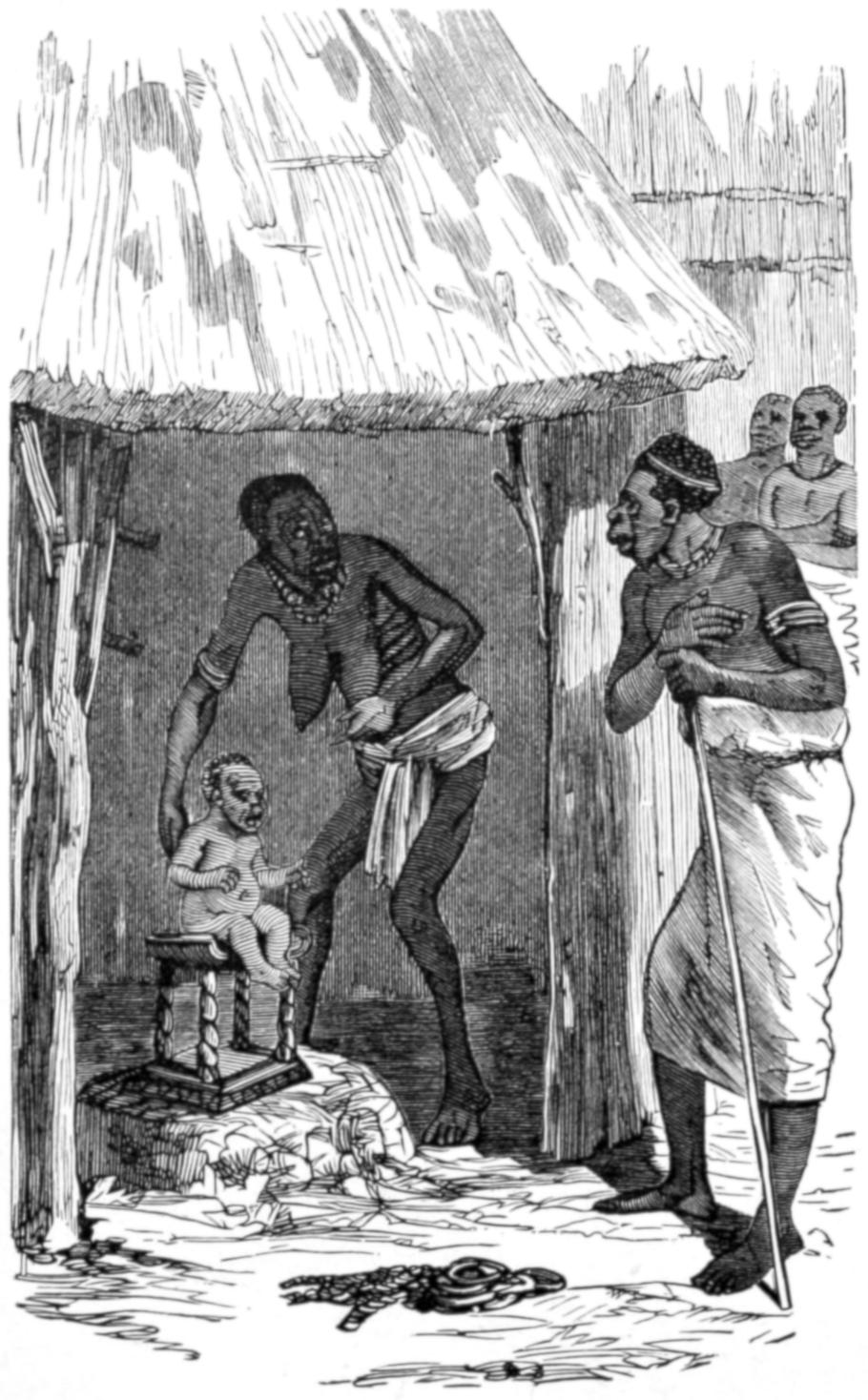

| 149. | The primeval child in Dahome | 552 |

| 150. | Fetishes, male and female, of the Krumen | 552 |

| 151. | Dahoman ivory trumpets | 558 |

| 152. | Dahoman war drum | 558 |

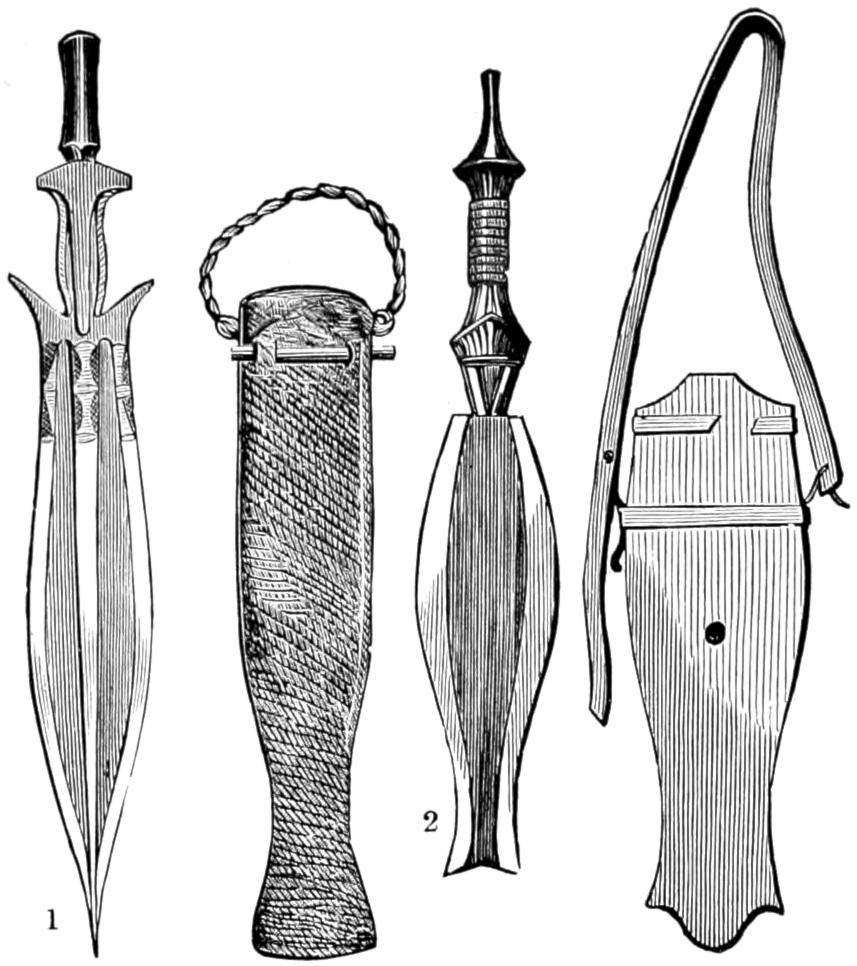

| 153. | War knives of the Fanti | 558 |

| 154. | Fetish trumpet and drum | 558 |

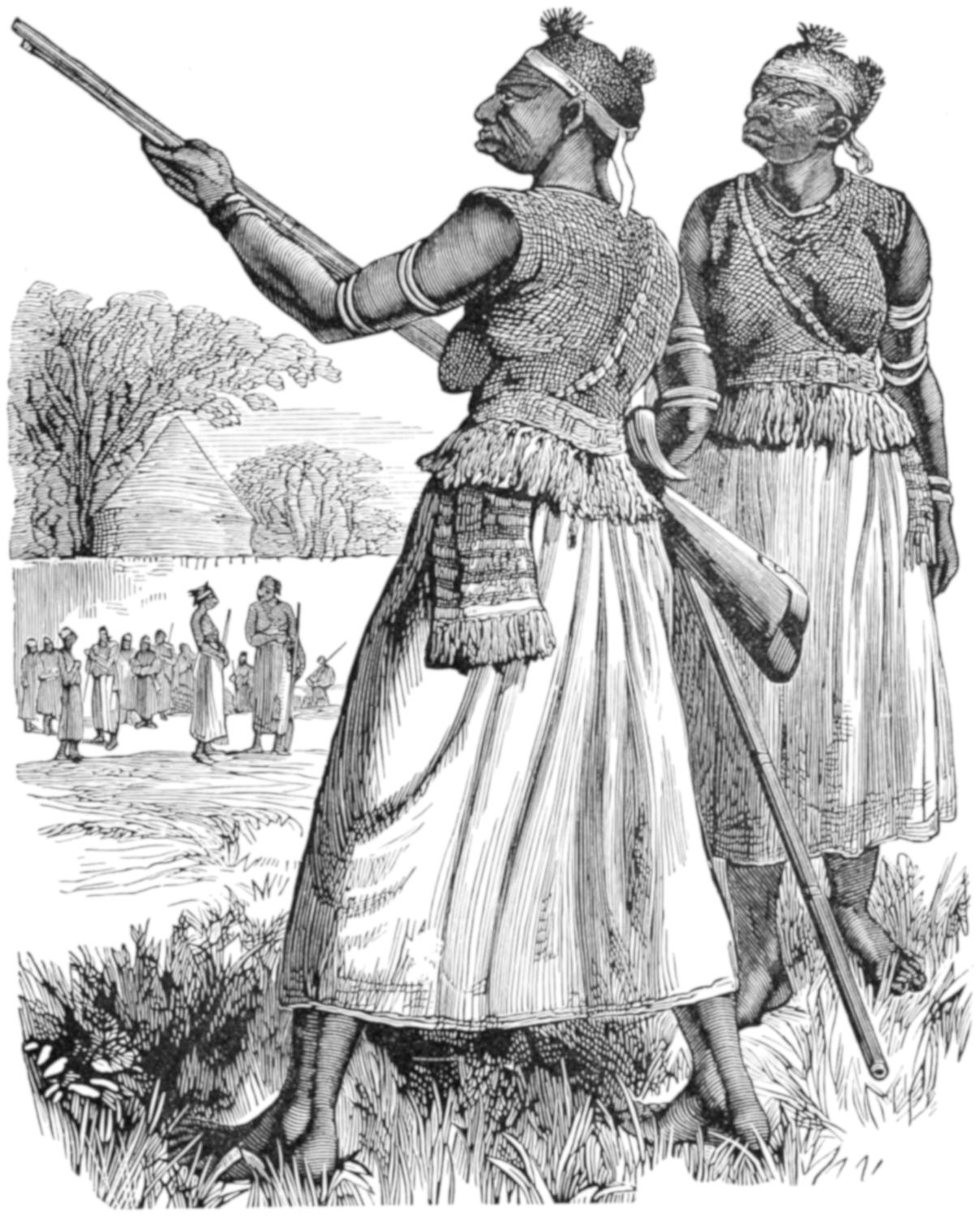

| 155. | Ashanti caboceer and soldiers | 564 |

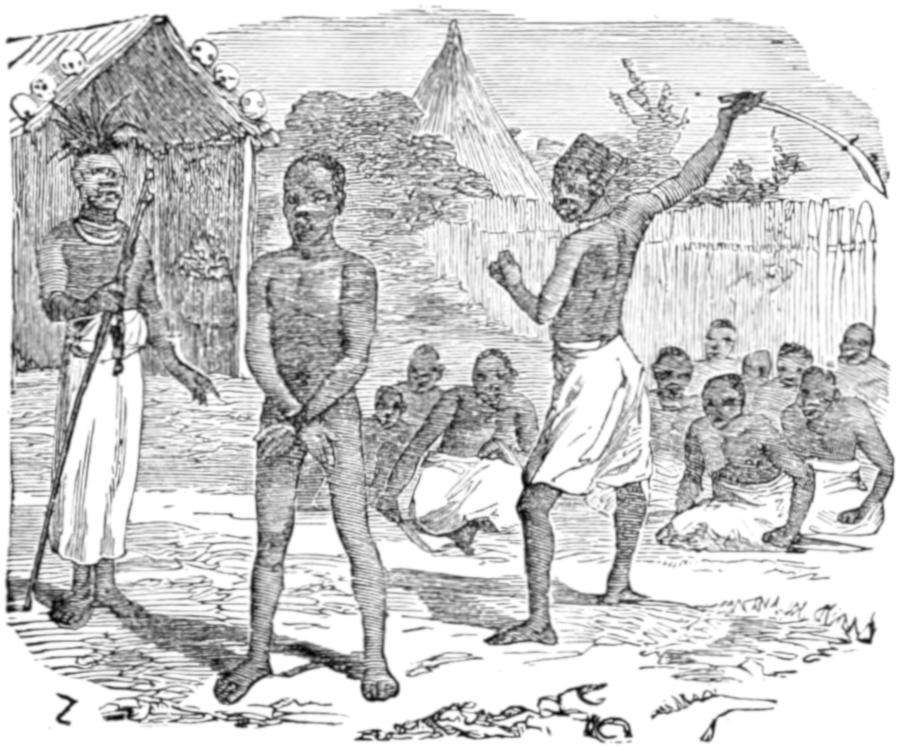

| 156. | Punishment of a snake killer | 564 |

| 157. | “The bell comes” | 569 |

| 158. | Dahoman amazons | 569 |

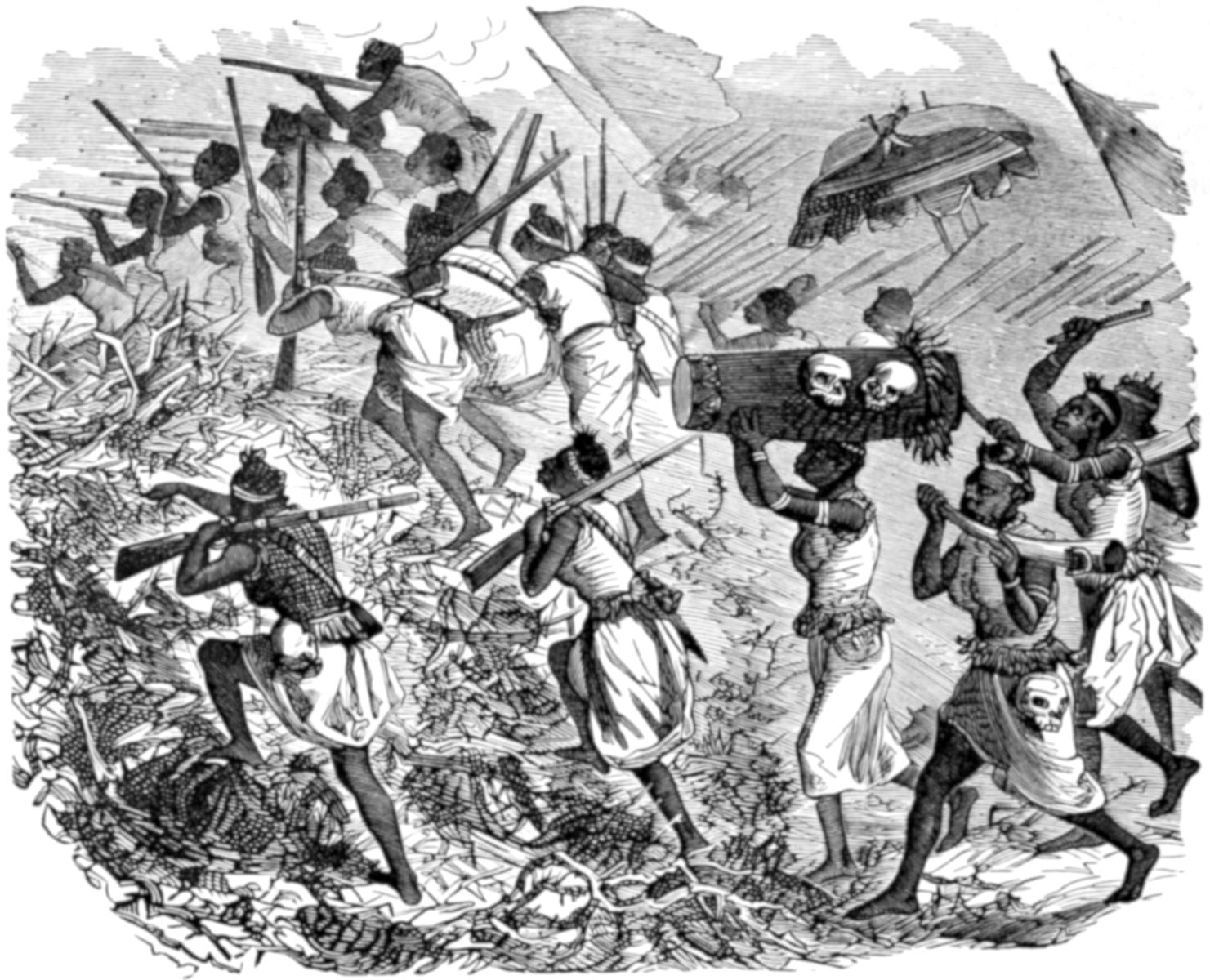

| 159. | Amazon review | 576 |

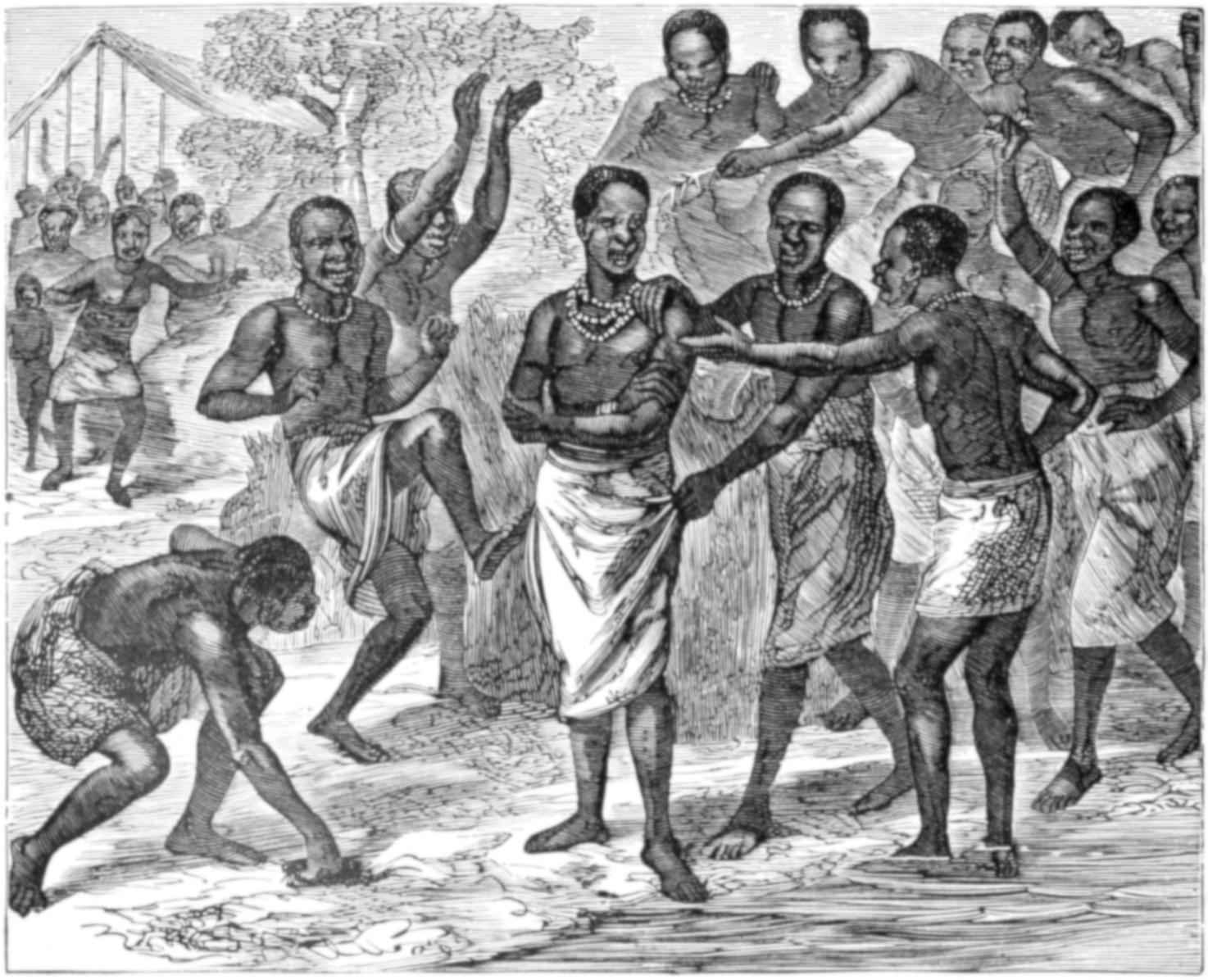

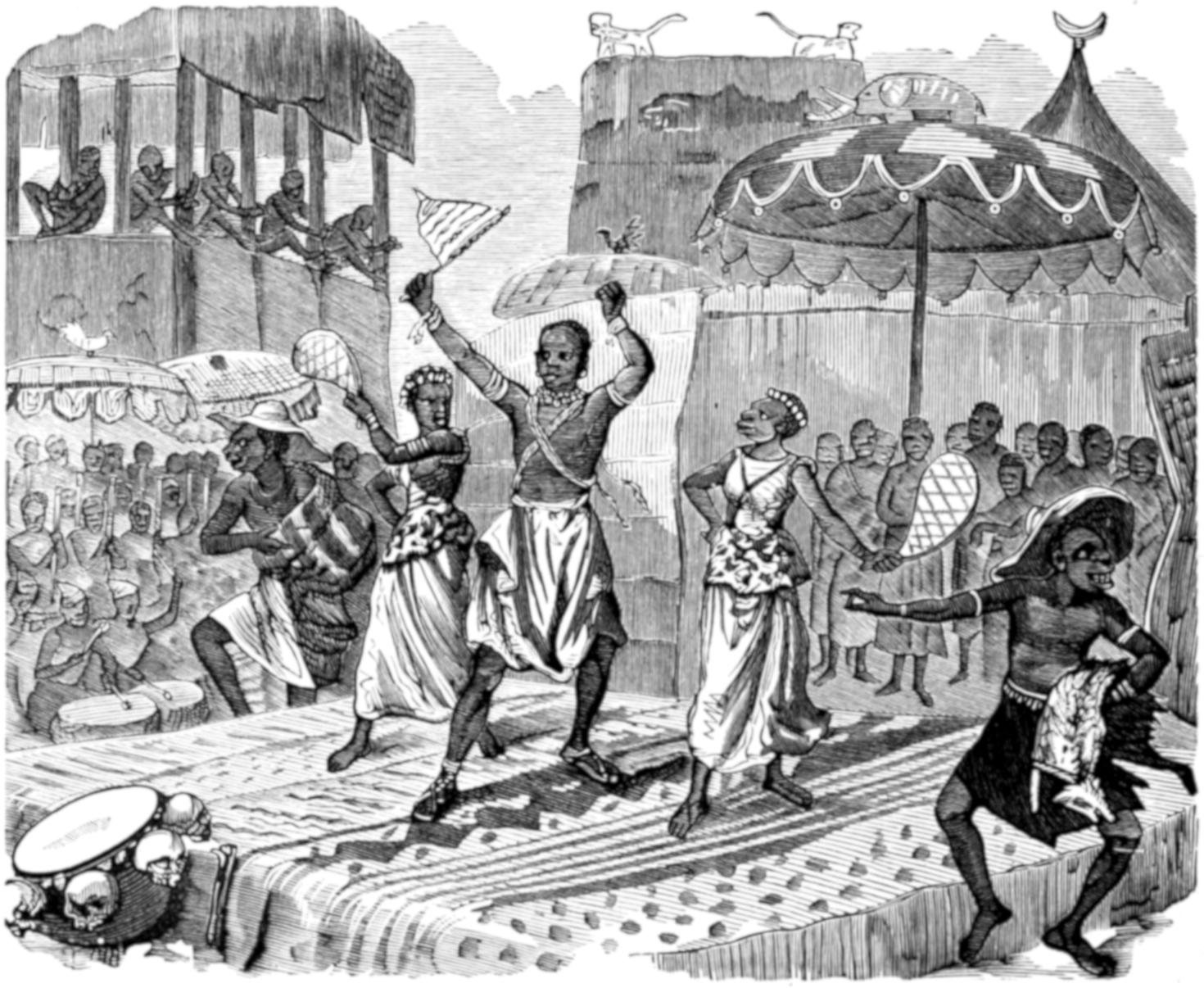

| 160. | The Dahoman king’s dance | 576 |

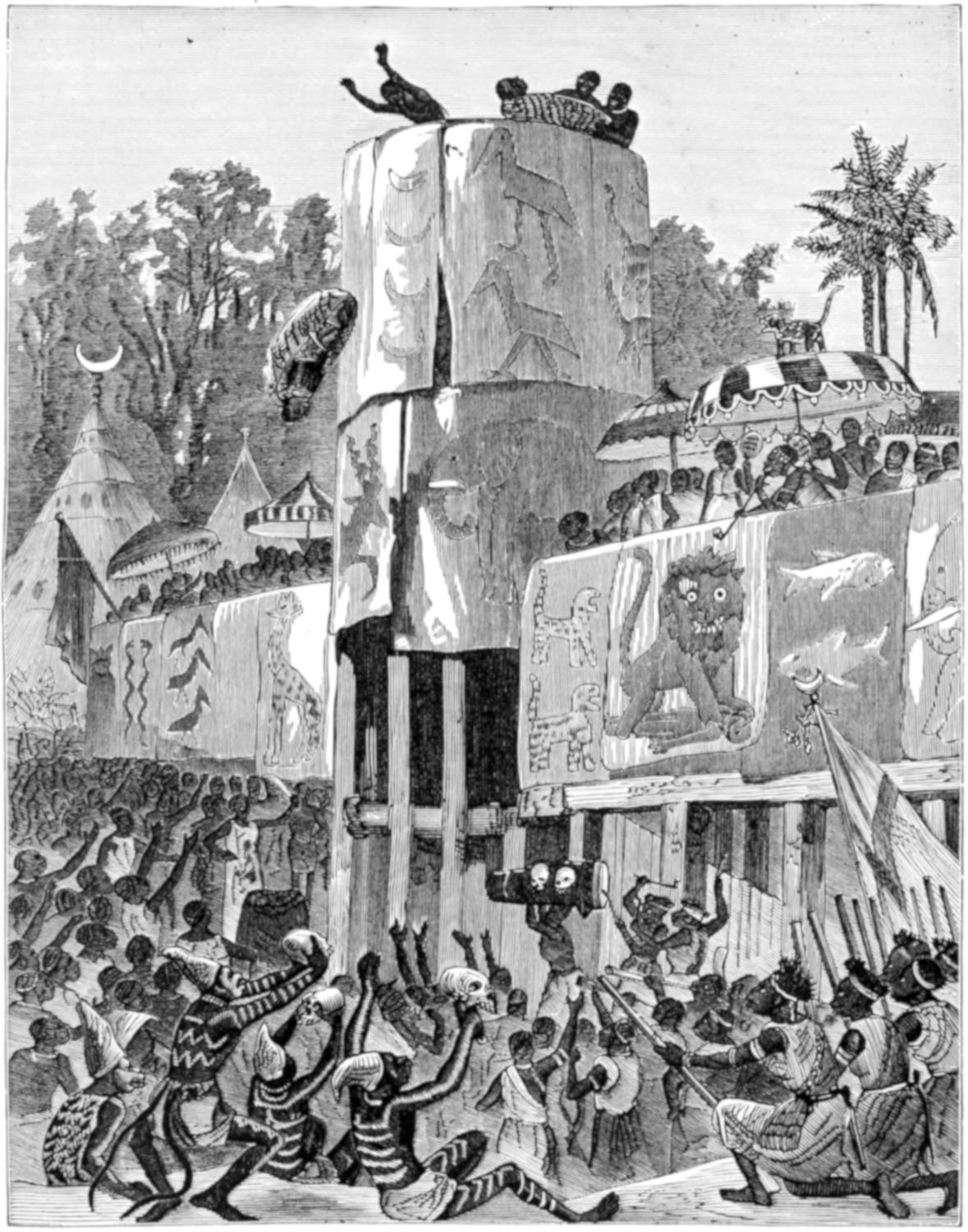

| 161. | The basket sacrifice in Dahome | 583 |

| 162. | Head worship in Dahome | 595 |

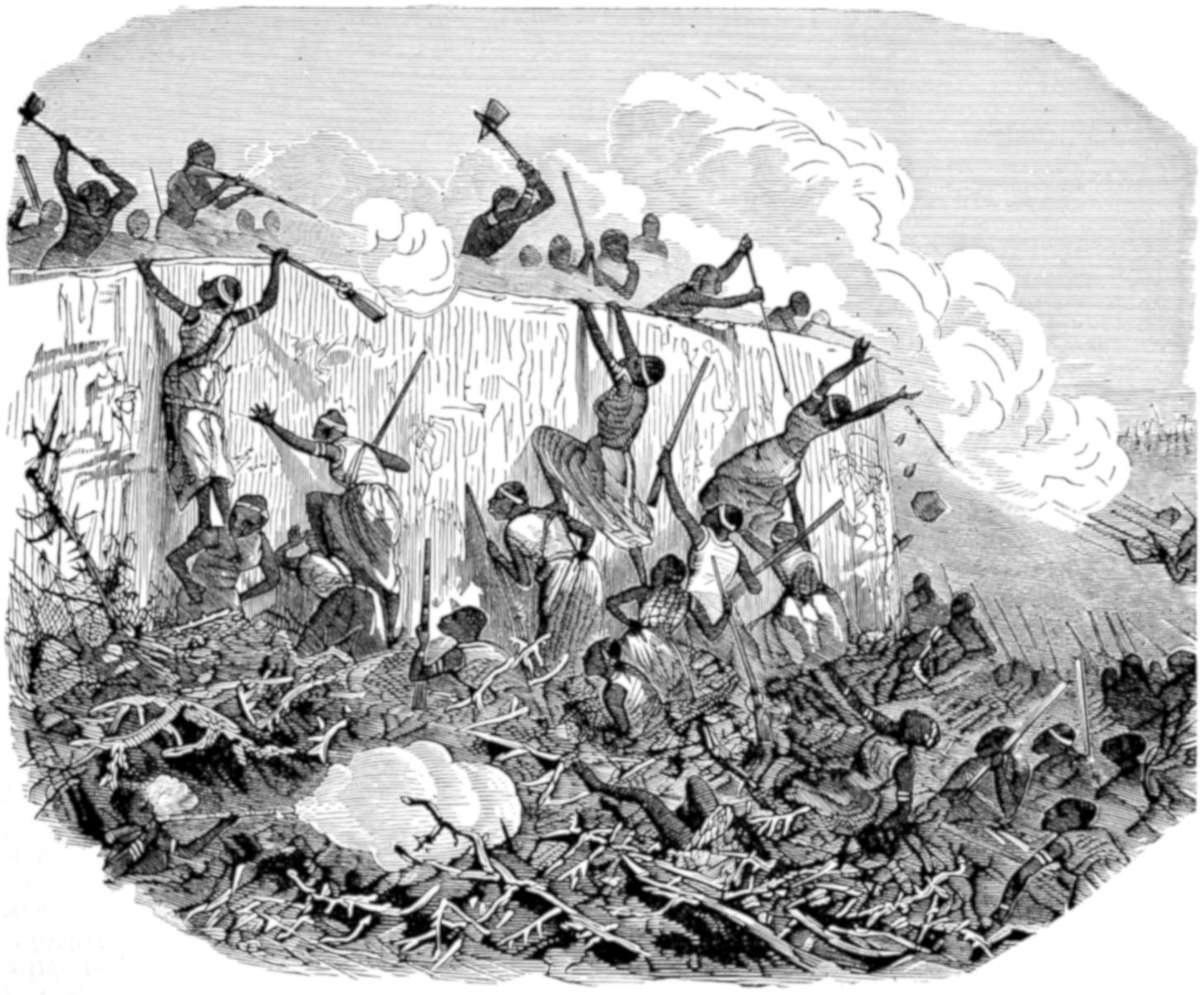

| 163. | The attack on Abeokuta | 595 |

| 164. | The Alaké’s (king of the Egbas) court | 605 |

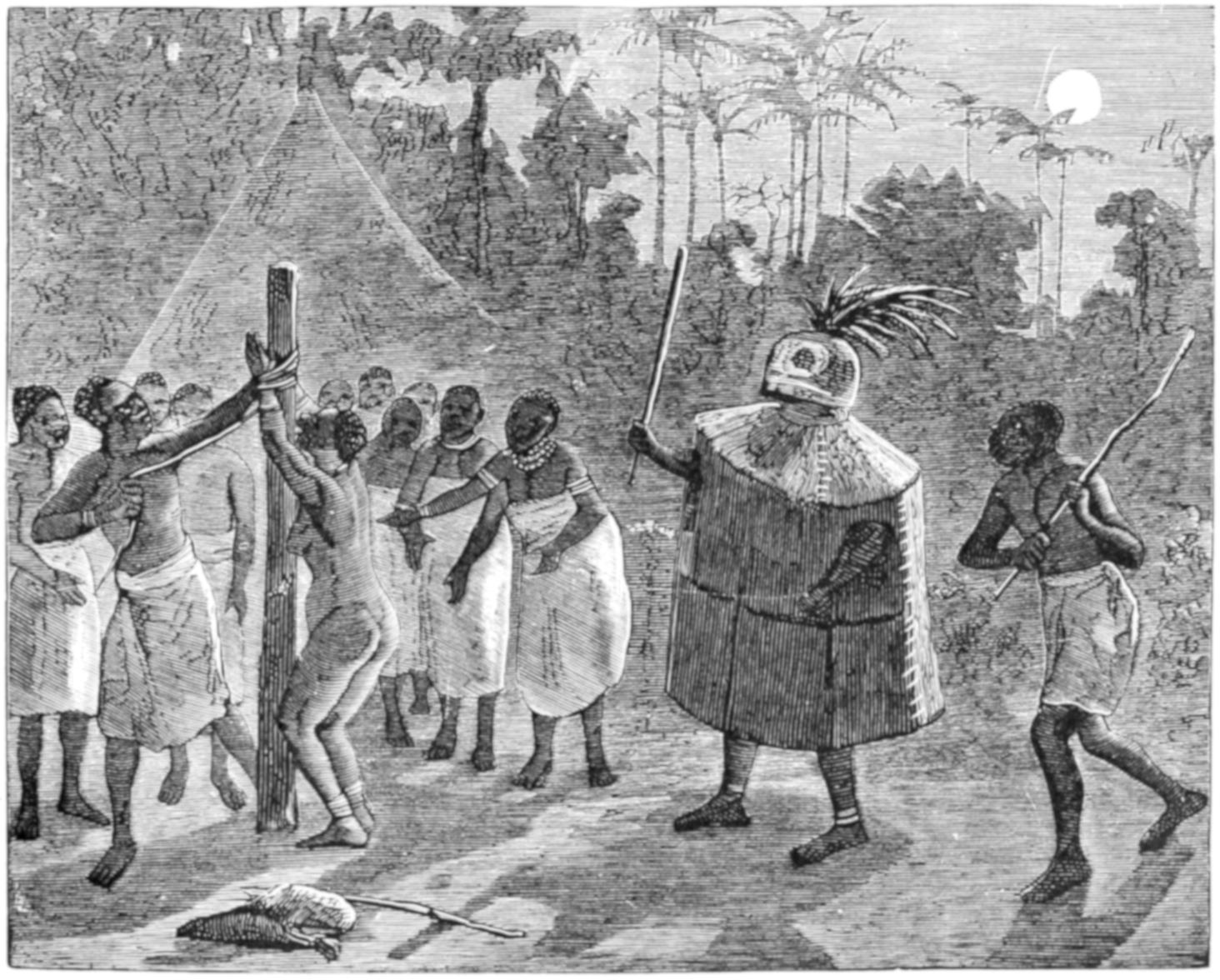

| 165. | Mumbo Jumbo | 605 |

| 166. | A Bubé marriage | 612 |

| 167. | Kanemboo man and woman | 612 |

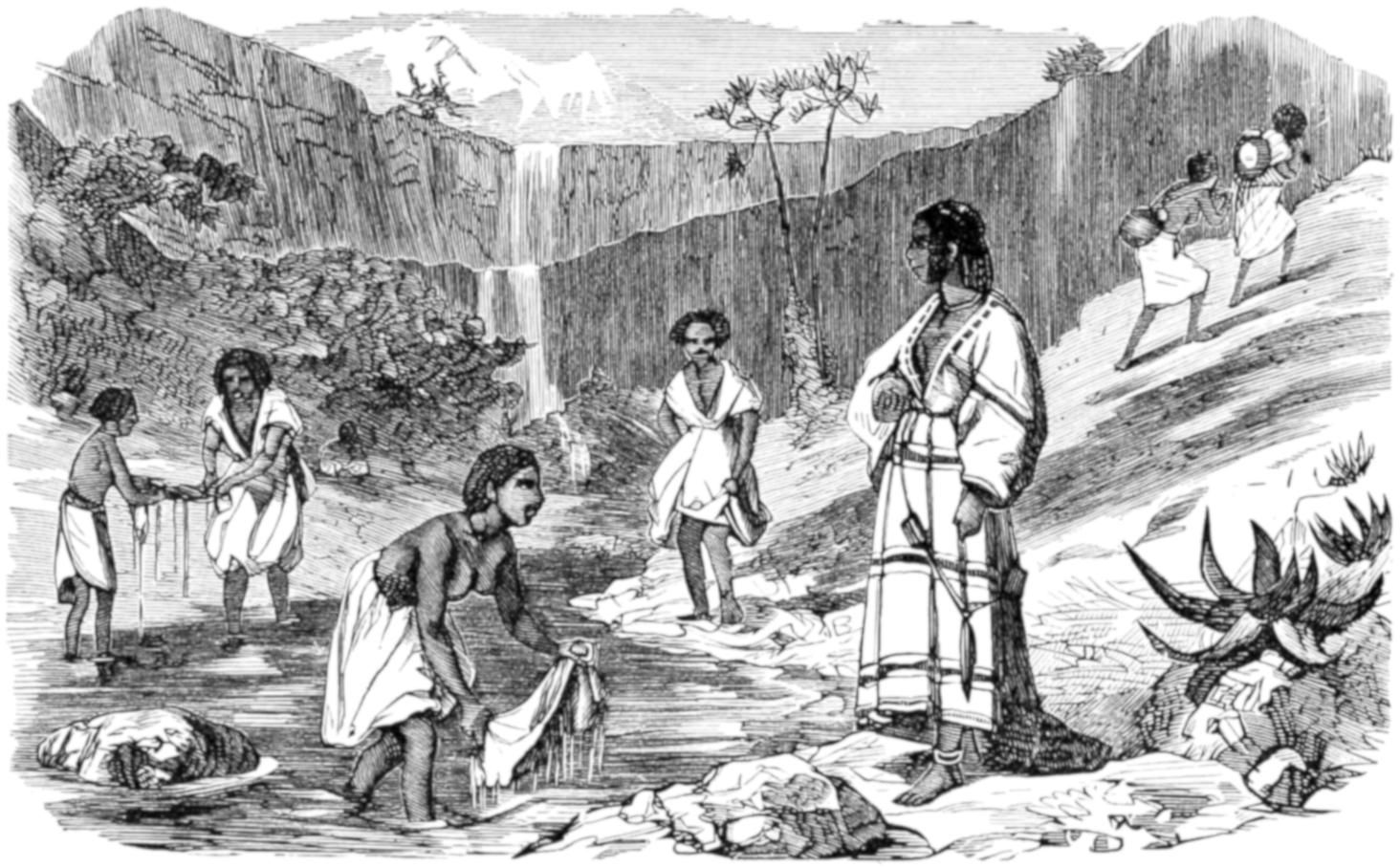

| 168. | Washing day in Abyssinia | 617 |

| 169. | A Congo coronation | 617 |

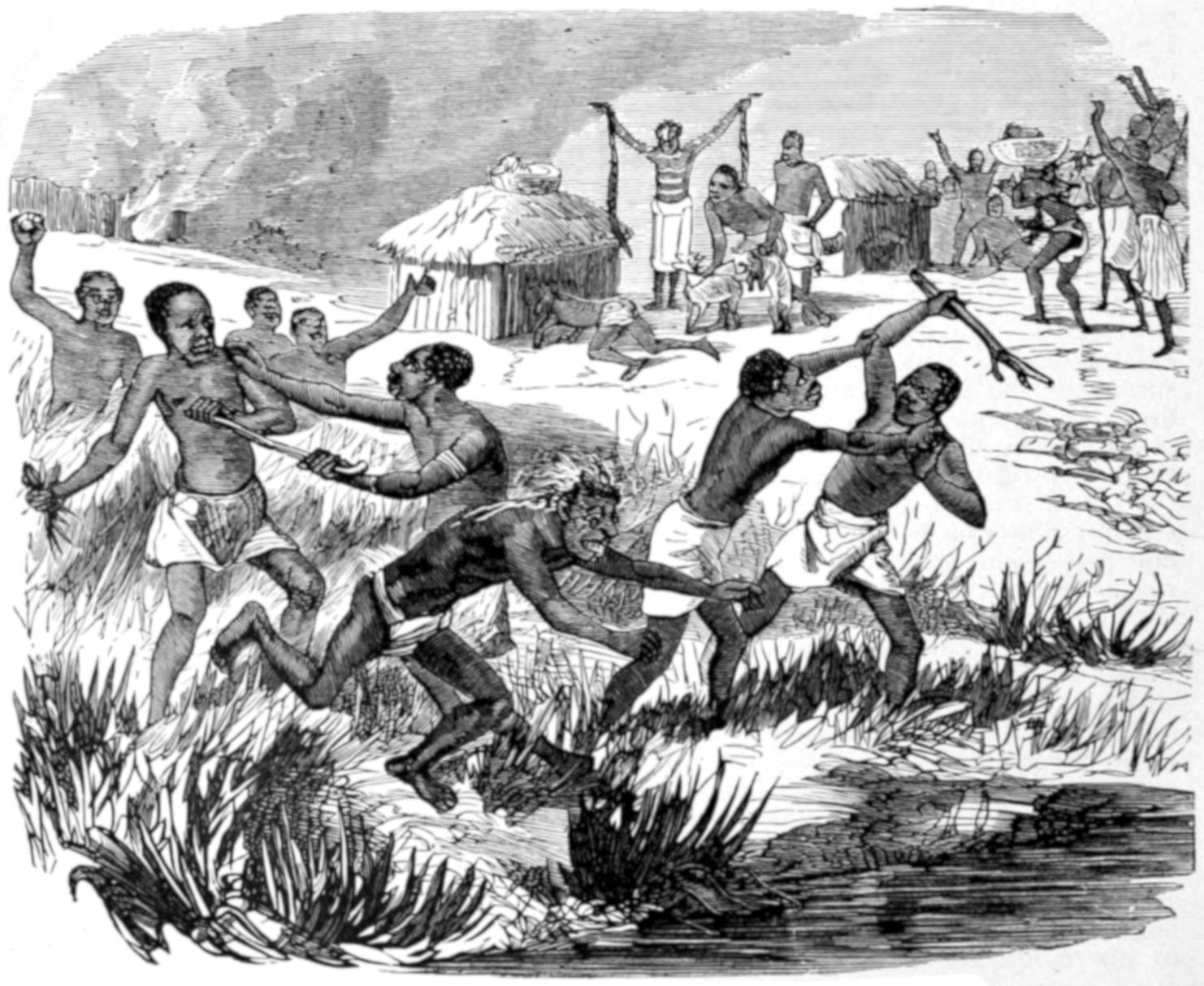

| 170. | Ju-ju execution | 619 |

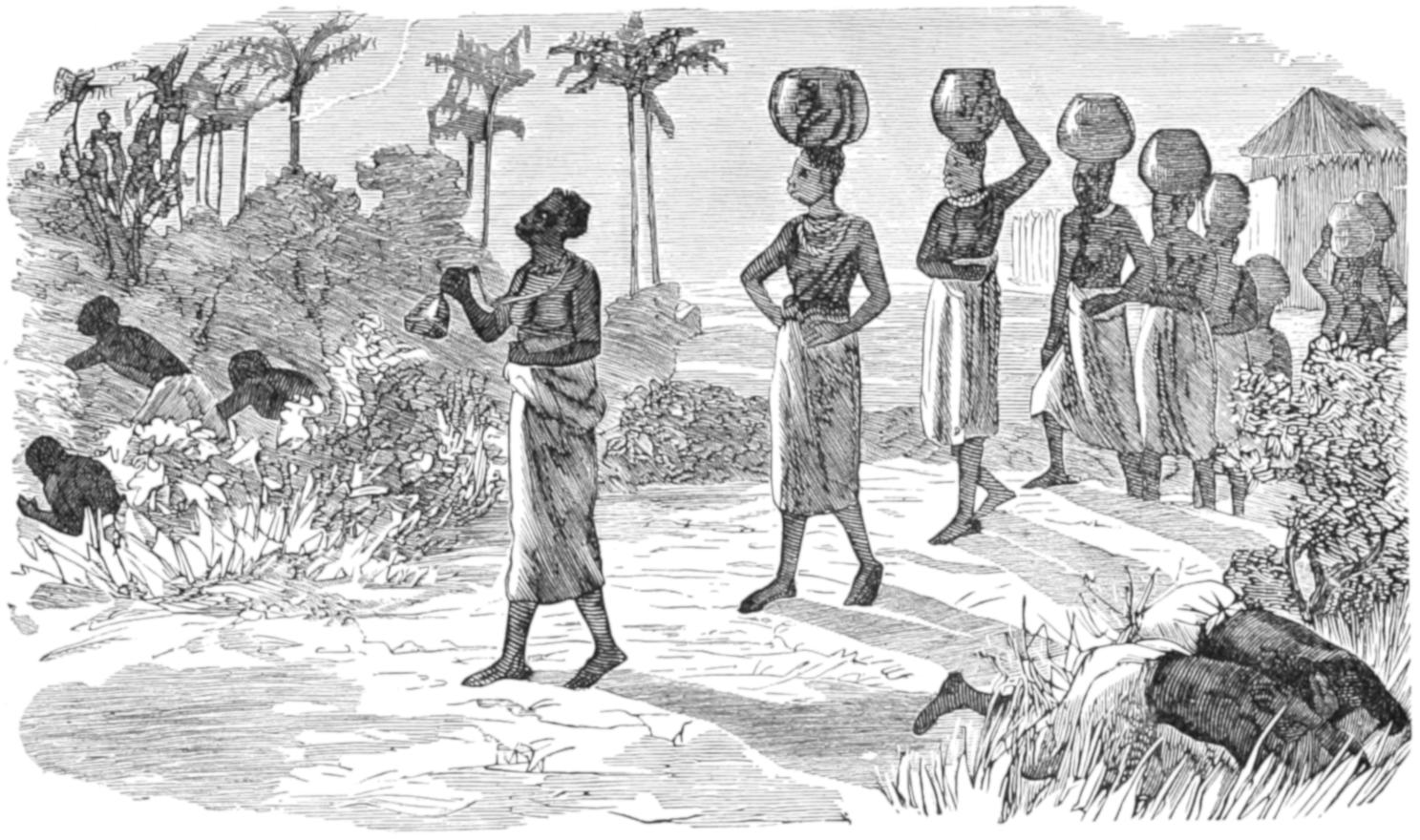

| 171. | Shooa women | 631 |

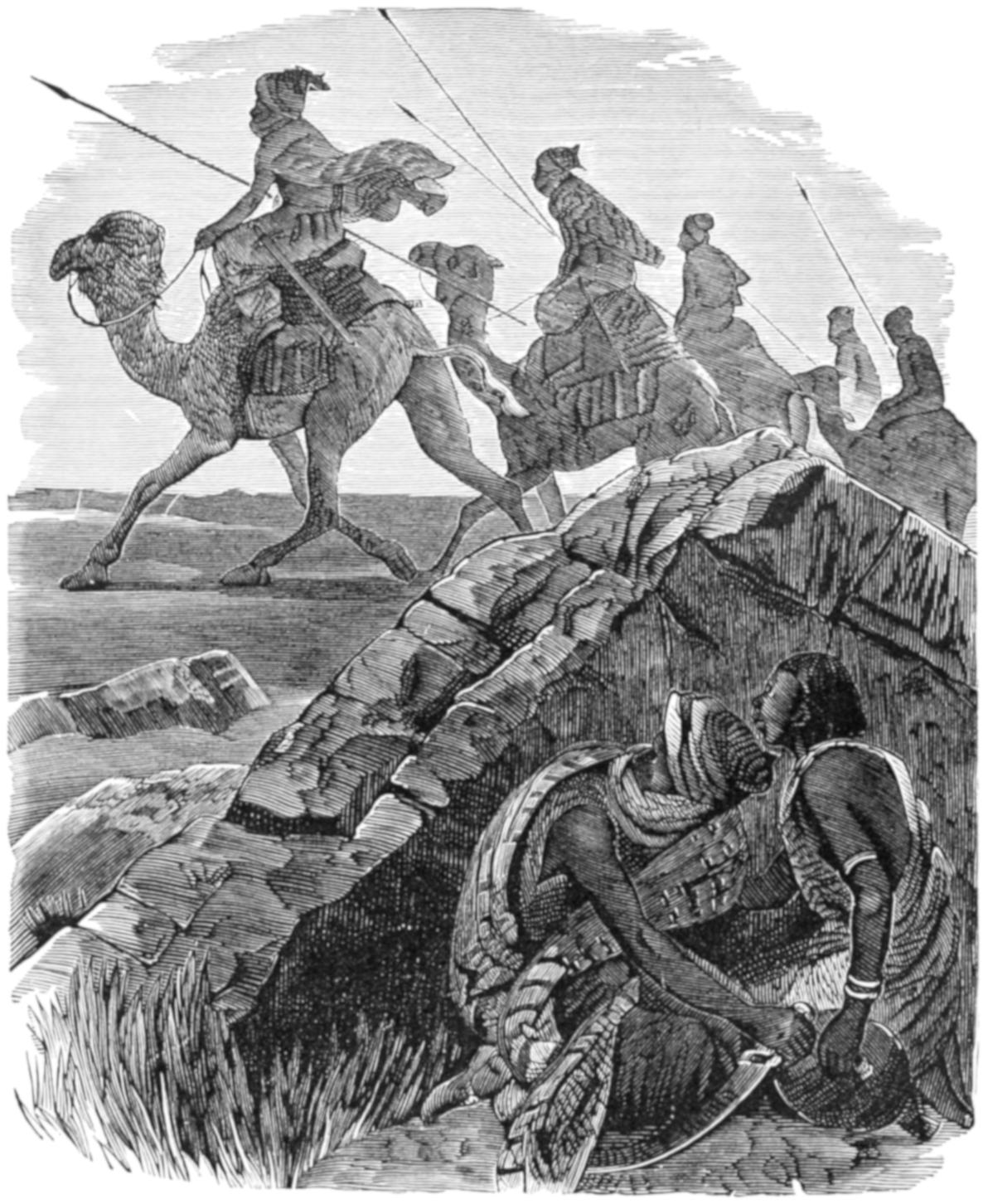

| 172. | Tuaricks and Tibboos | 631 |

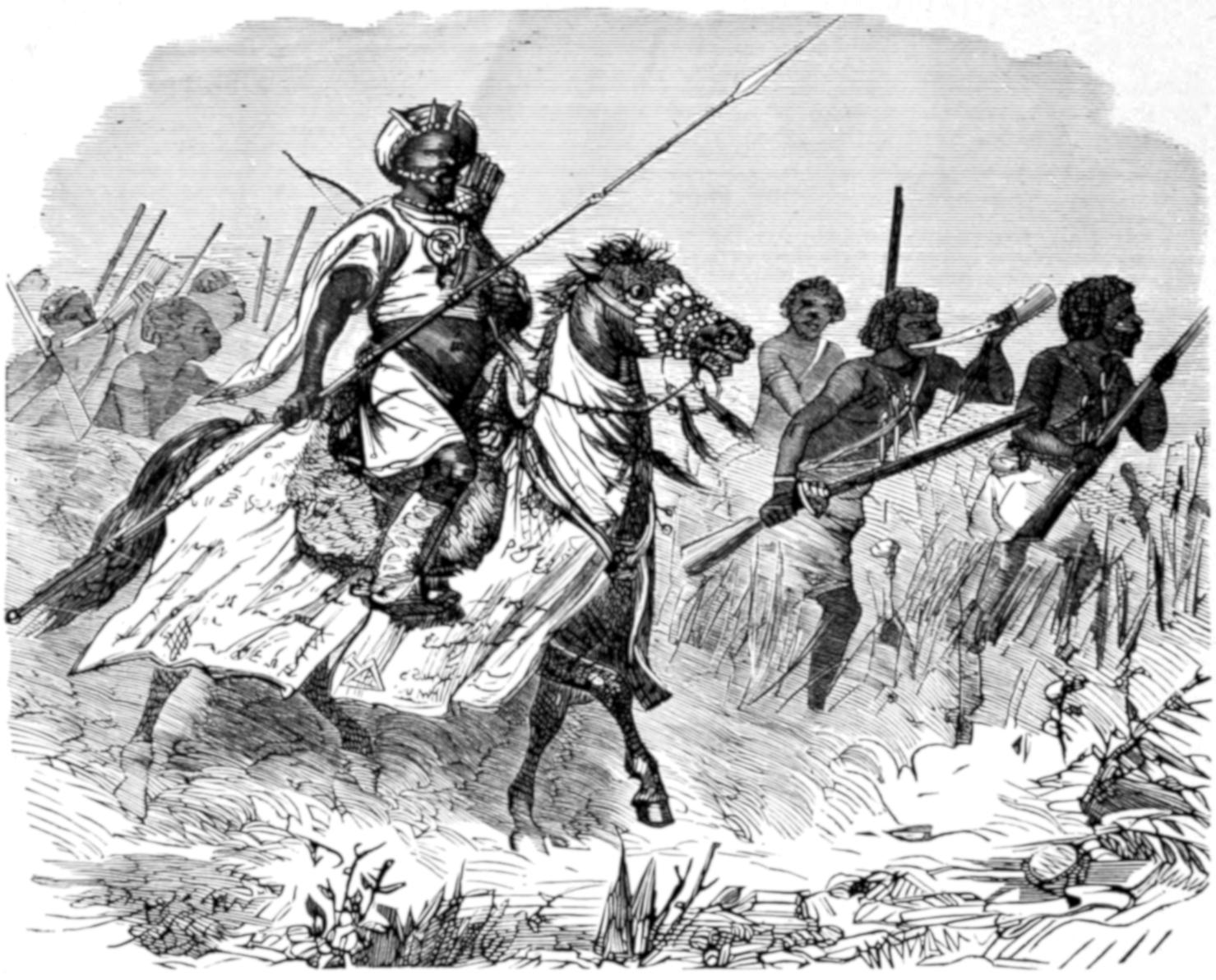

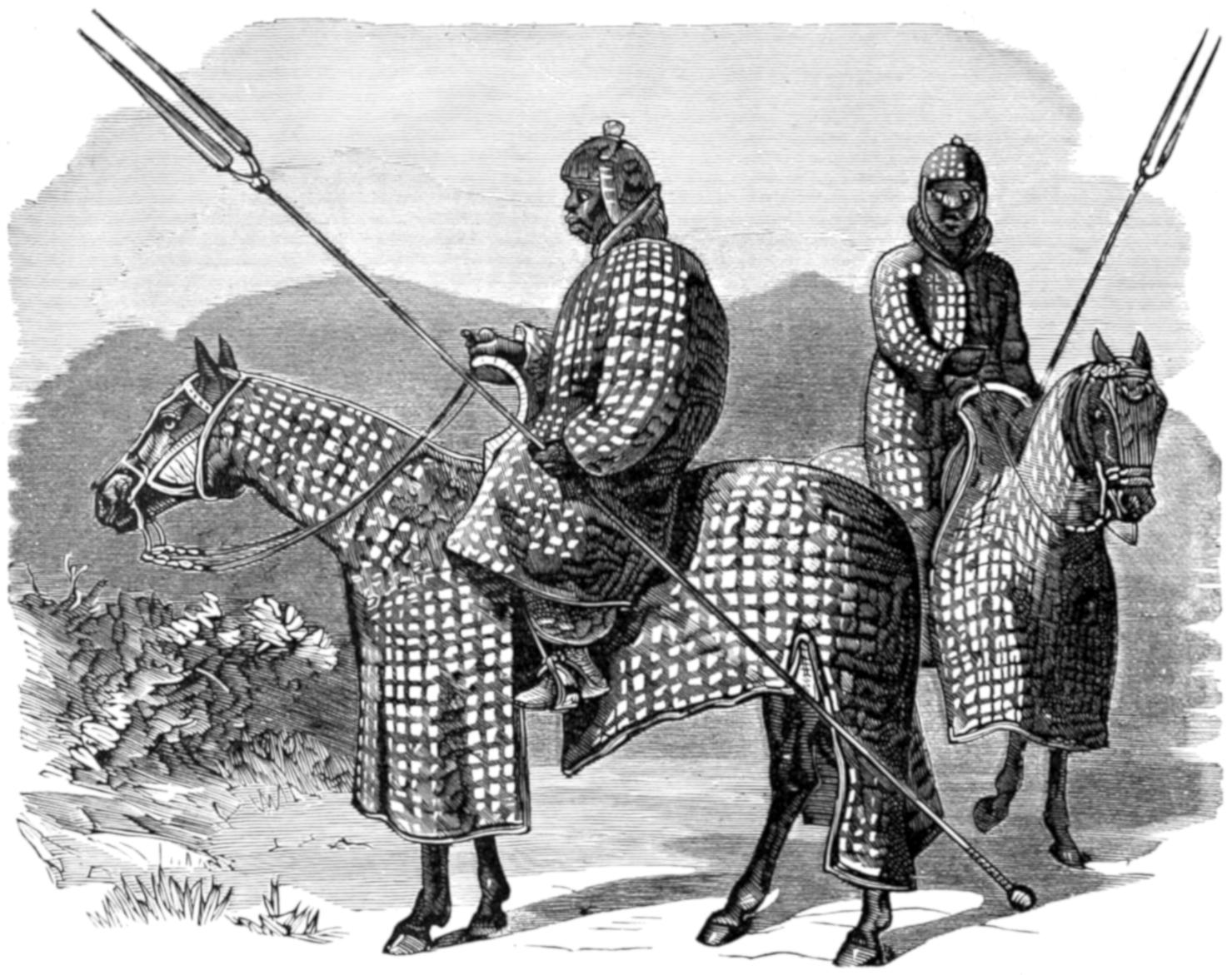

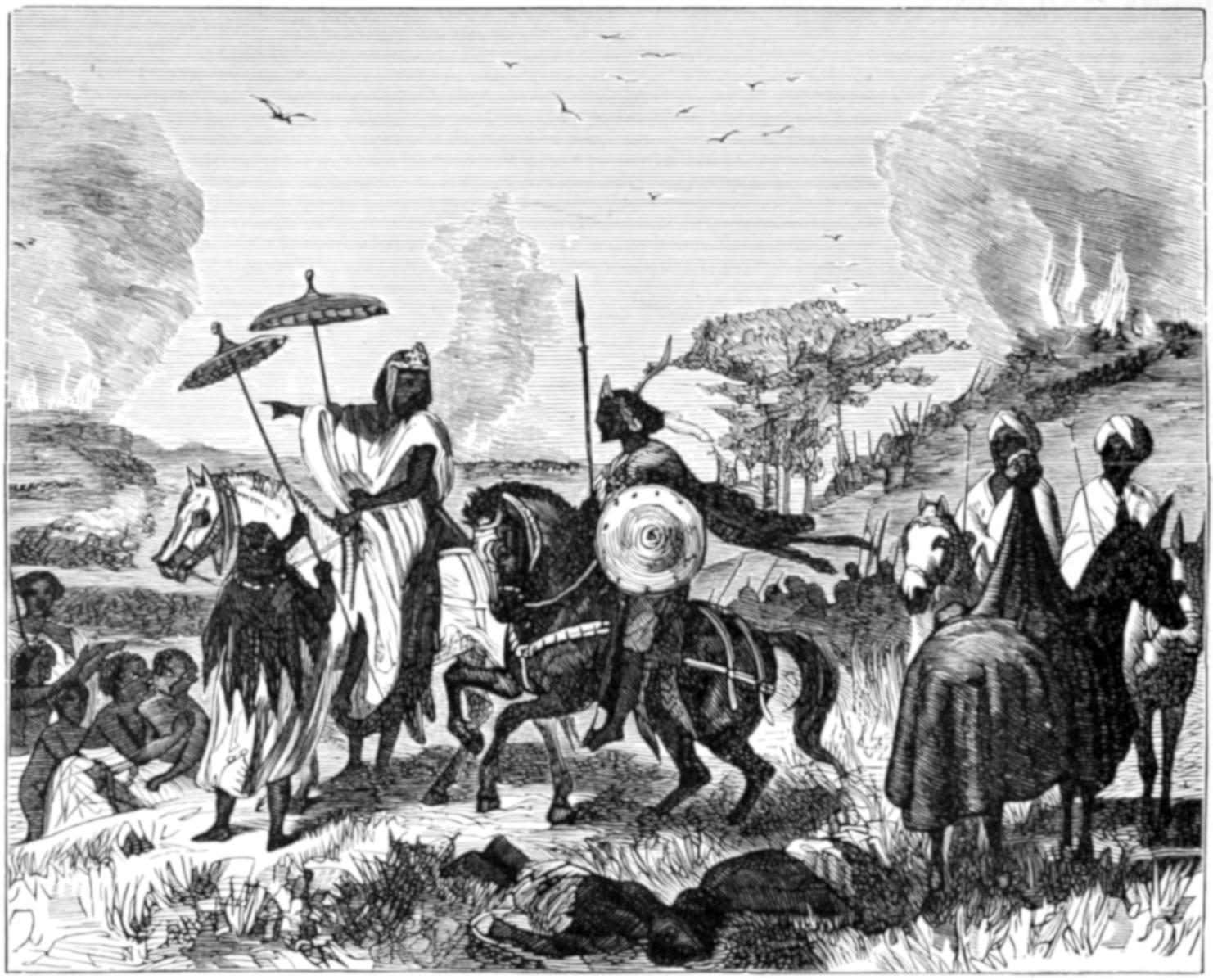

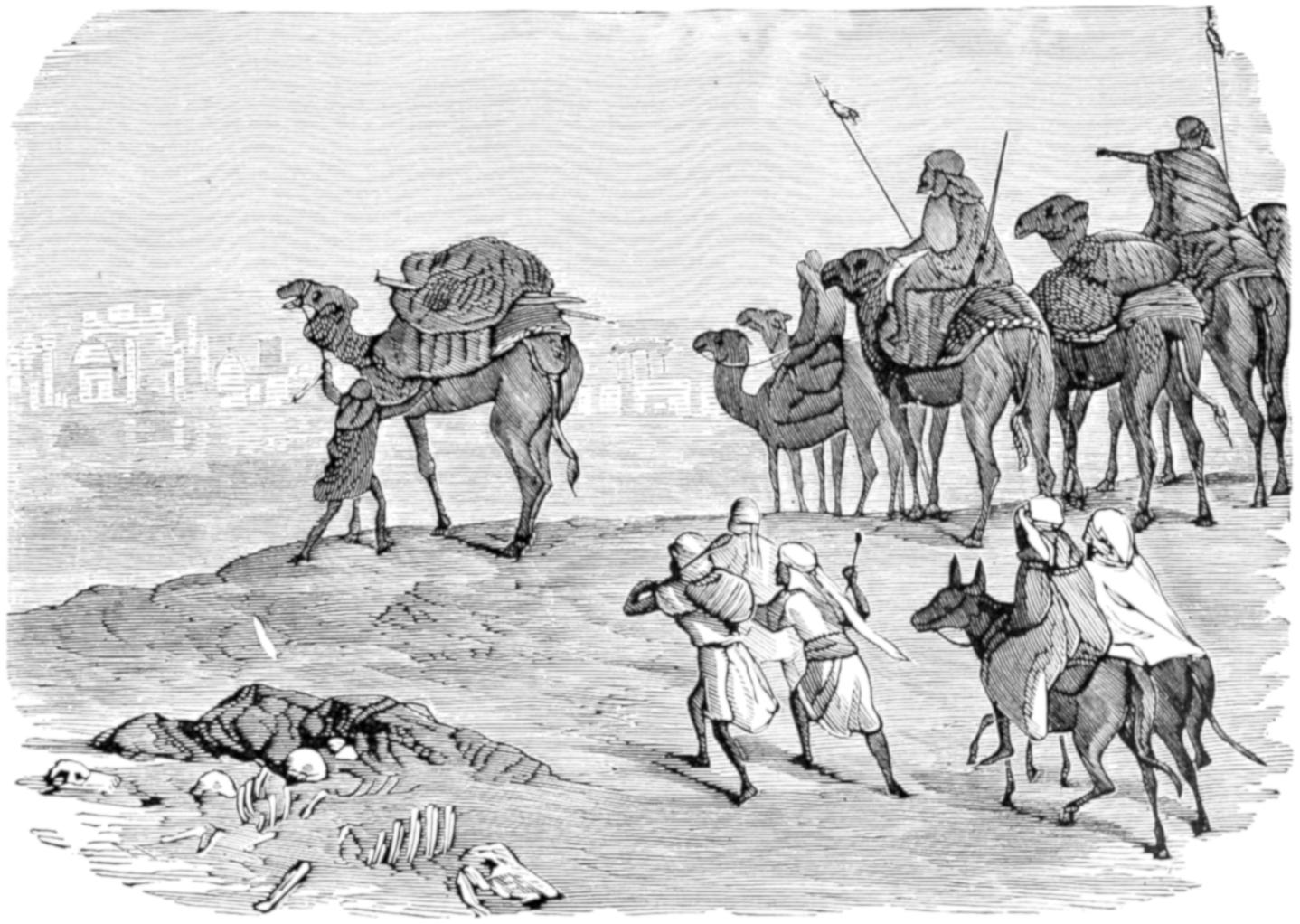

| 173. | Begharmi lancers | 638 |

| 174. | Musgu chief | 638 |

| 175. | Dinner party in Abyssinia | 643 |

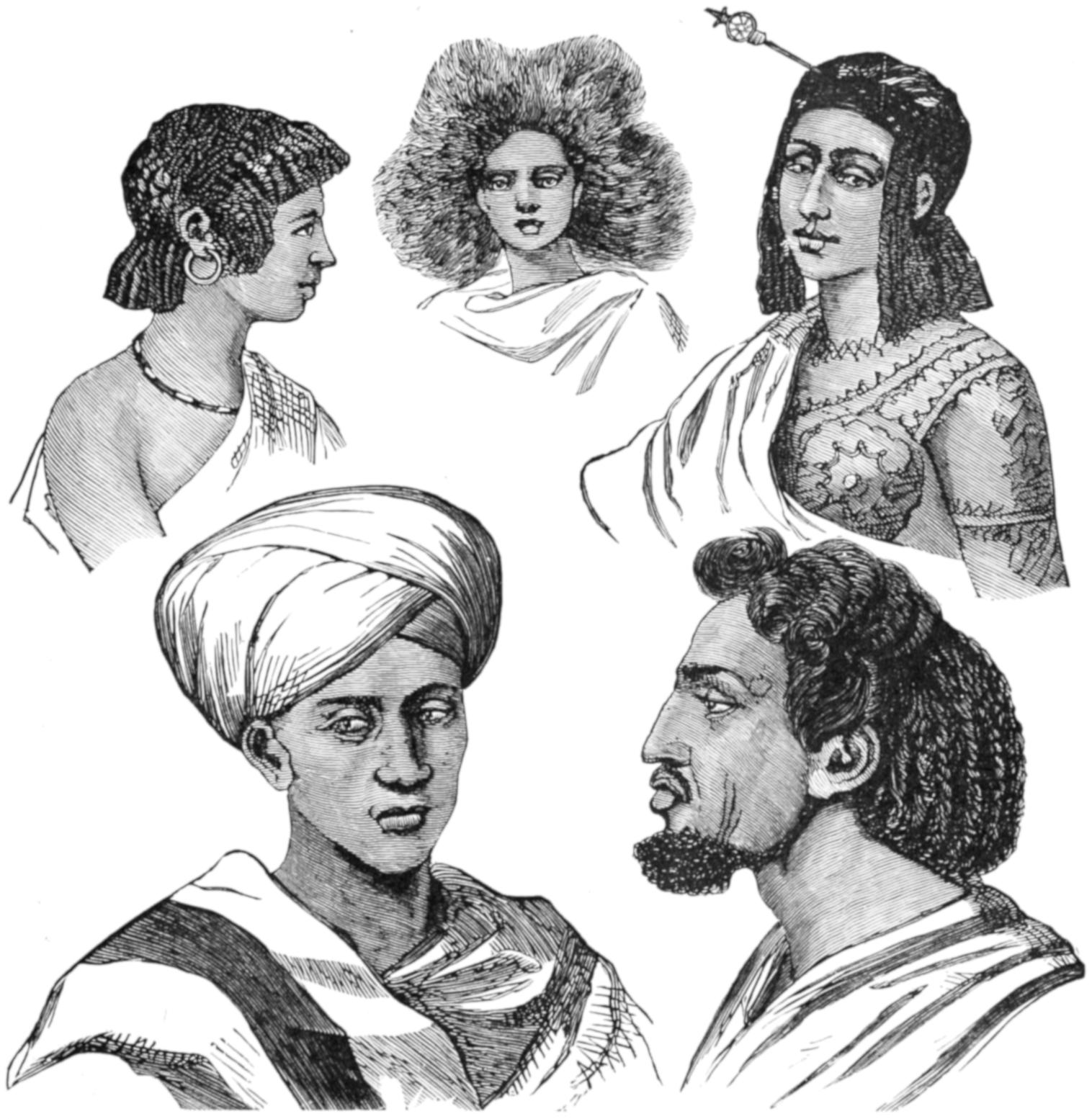

| 176. | Abyssinian heads | 643 |

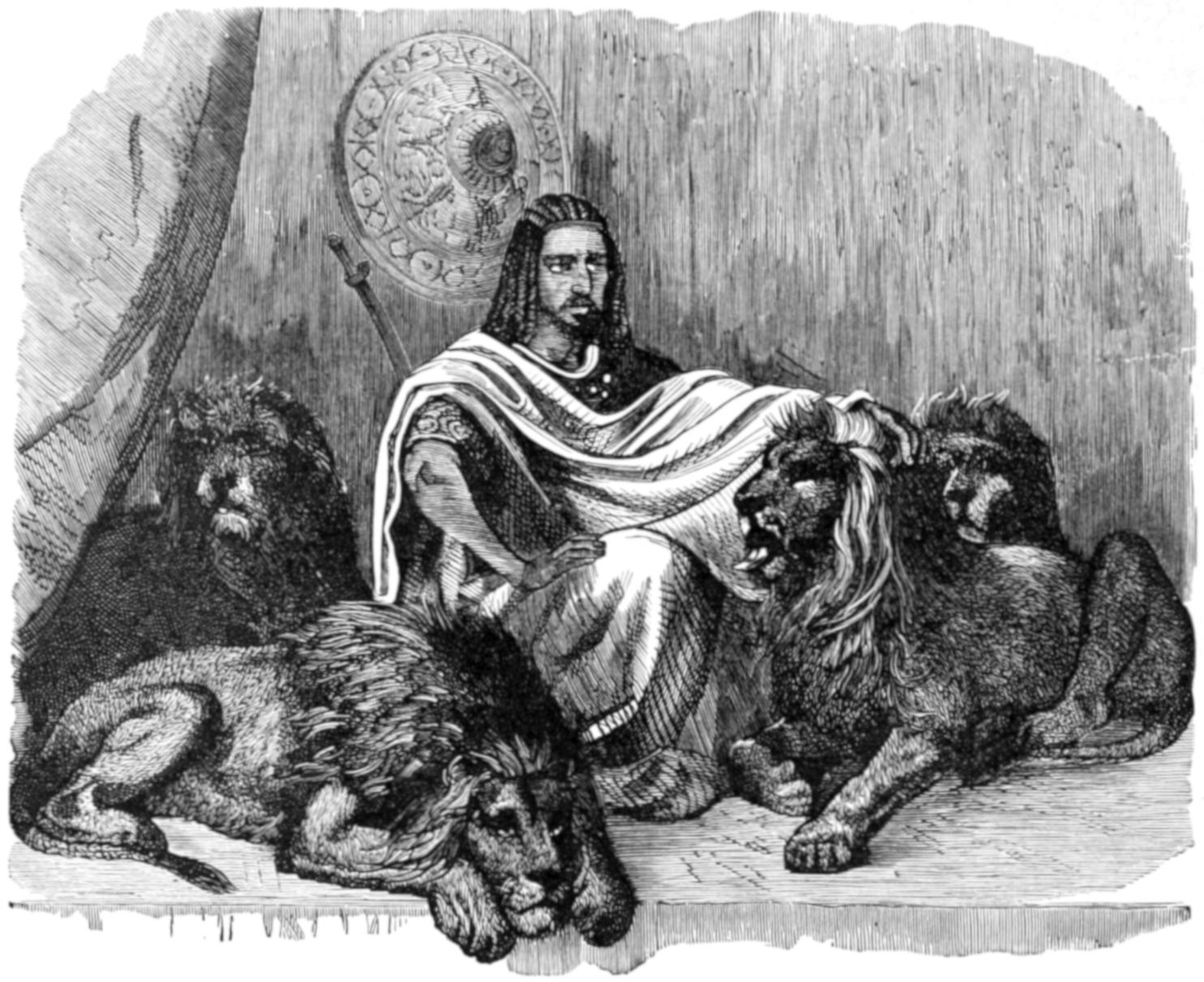

| 177. | King Theodore and the lions | 652 |

| 178. | Pleaders in the courts | 652 |

| 179. | A battle between Abyssinians and Gallas | 662 |

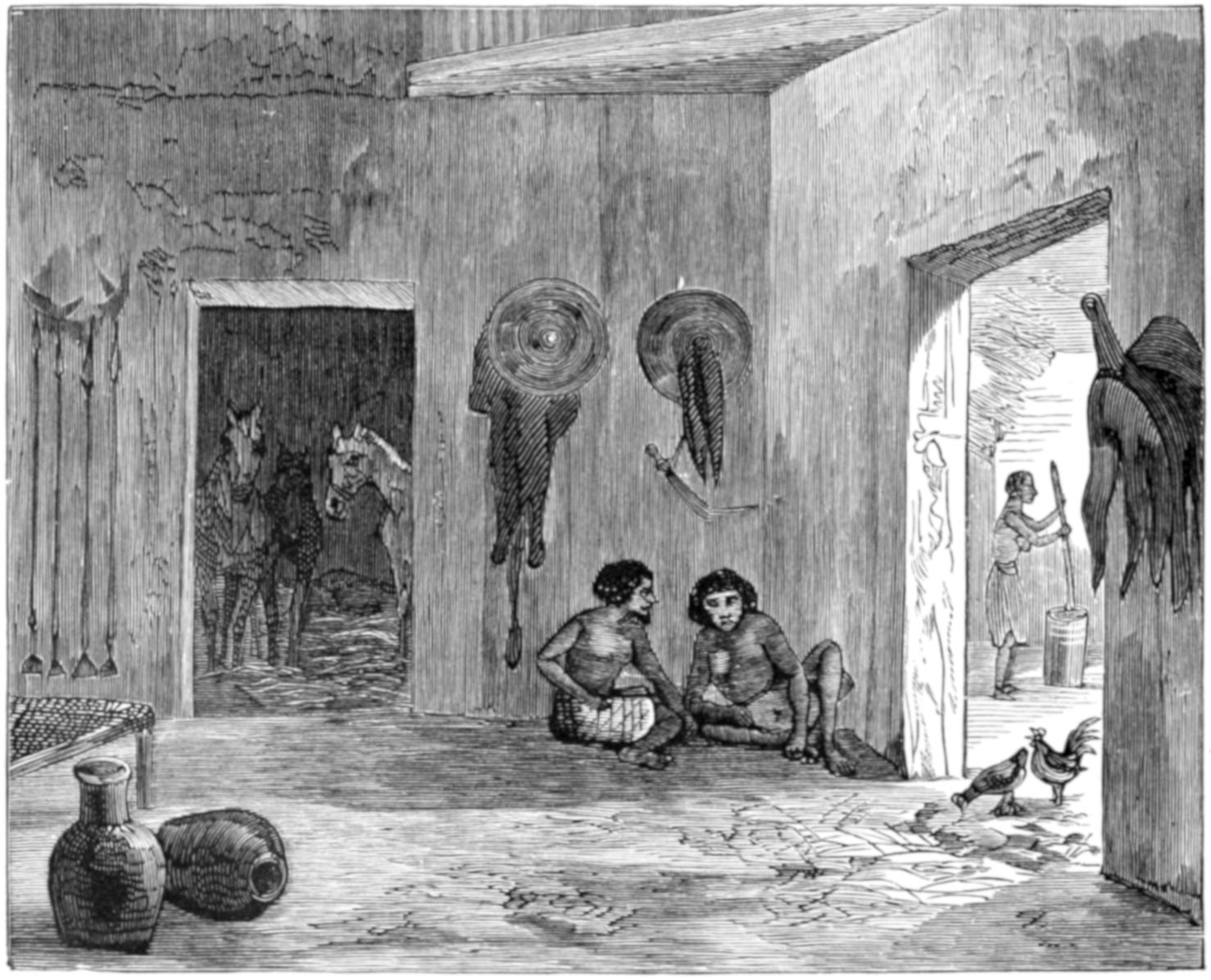

| 180. | Interior of an Abyssinian house | 662 |

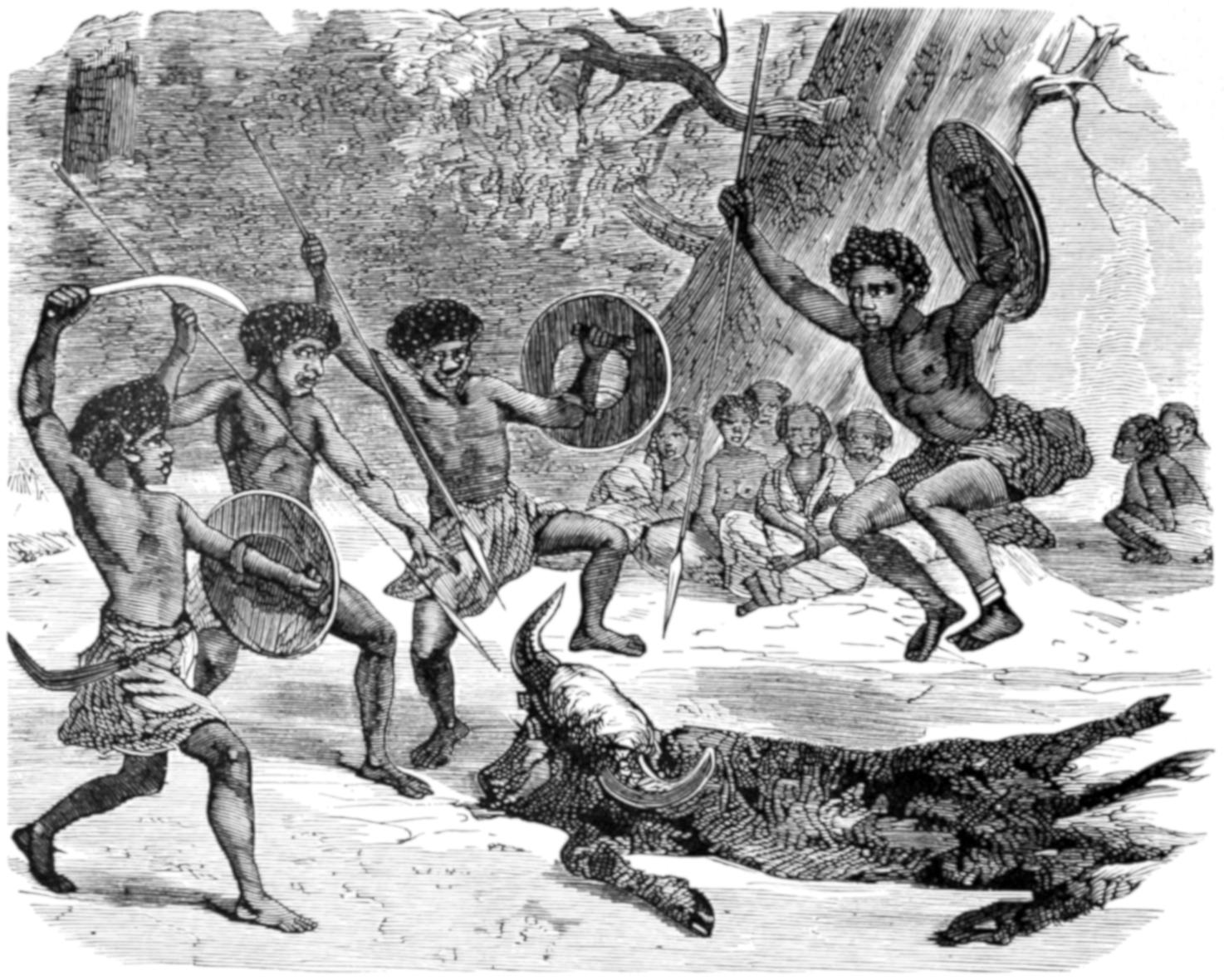

| 181. | Buffalo dance in Abyssinia | 670 |

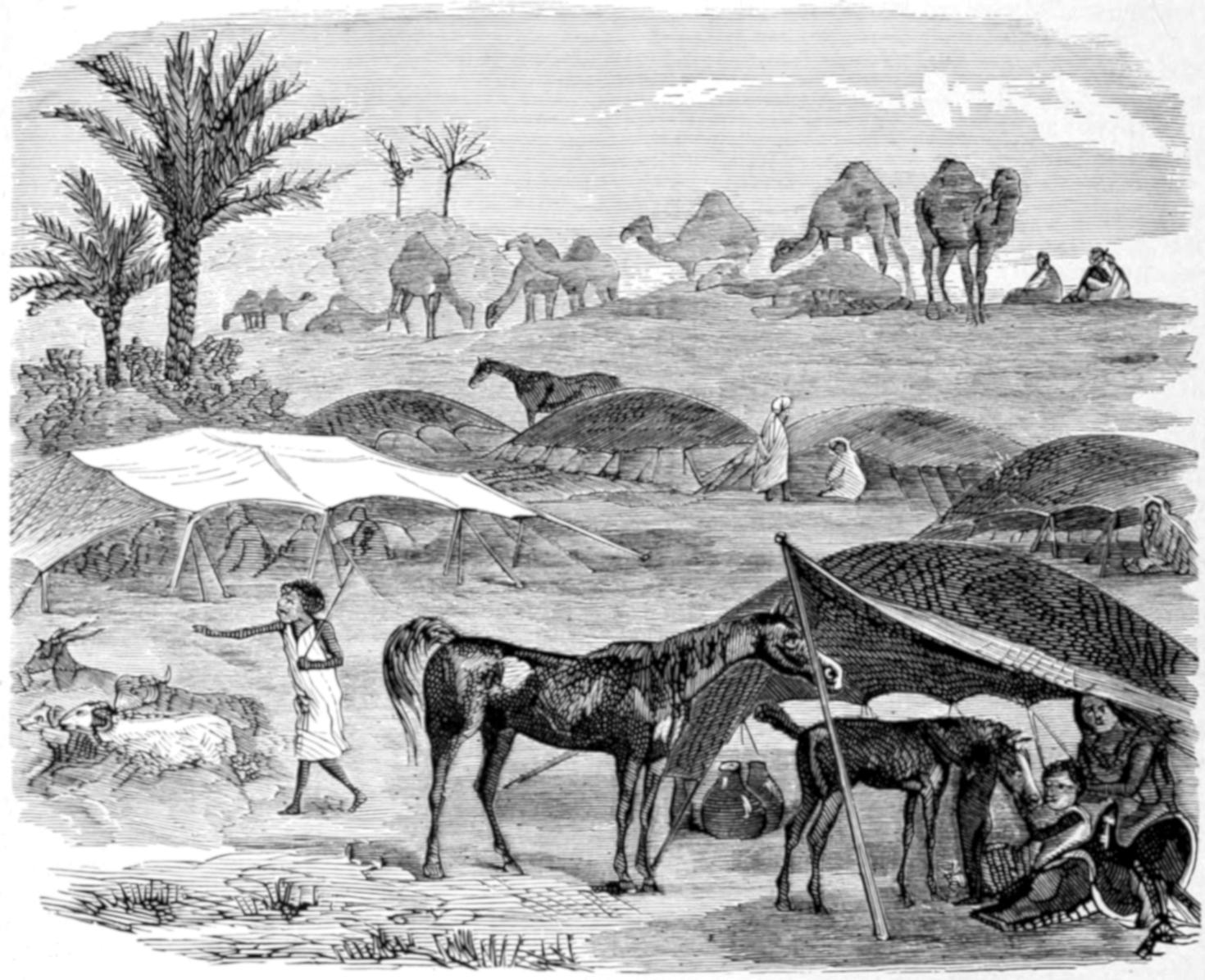

| 182. | Bedouin camp | 670 |

| 183. | Hunting the hippopotamus | 679 |

| 184. | Travellers and the mirage | 679 |

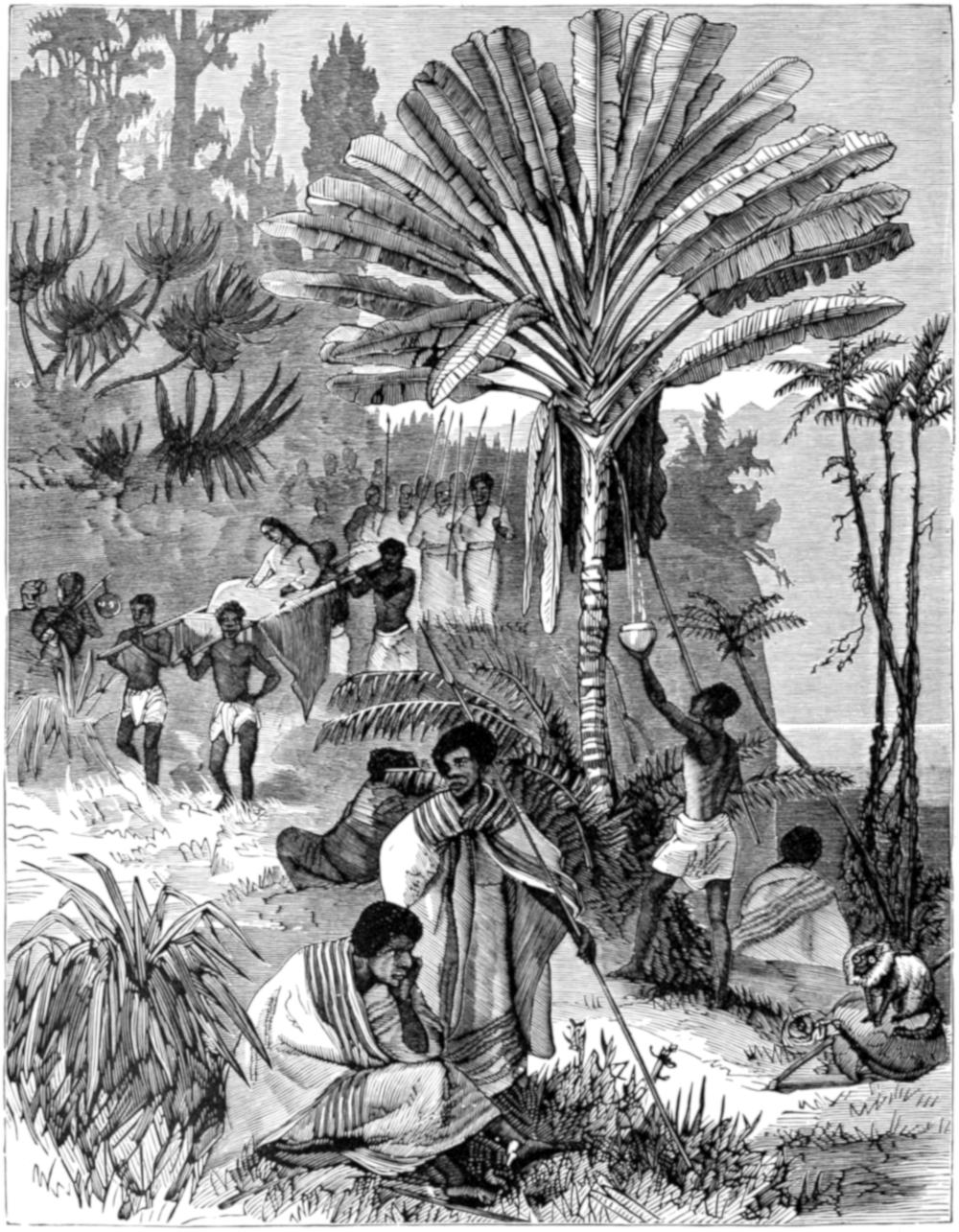

| 185. | Travelling in Madagascar | 692 |

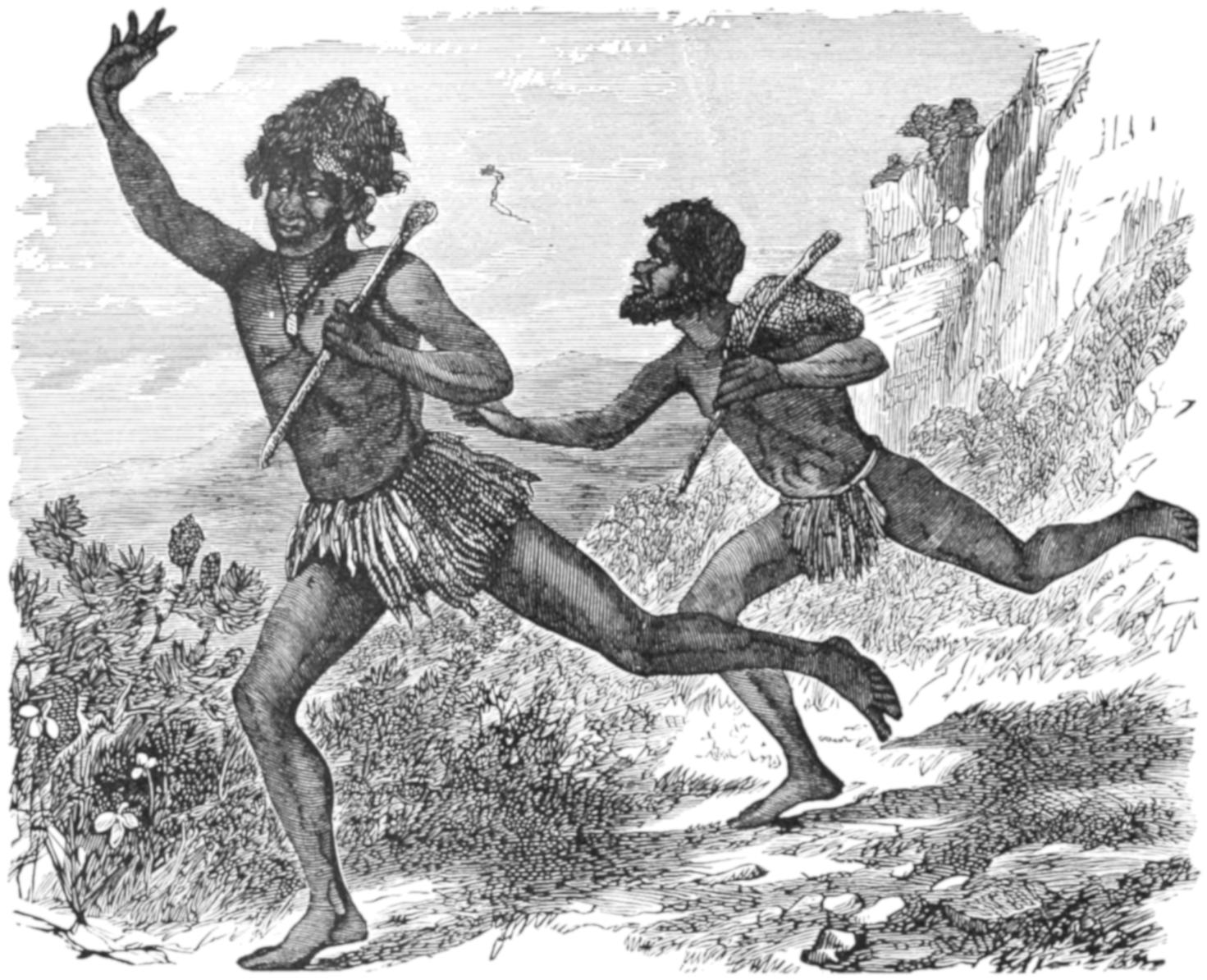

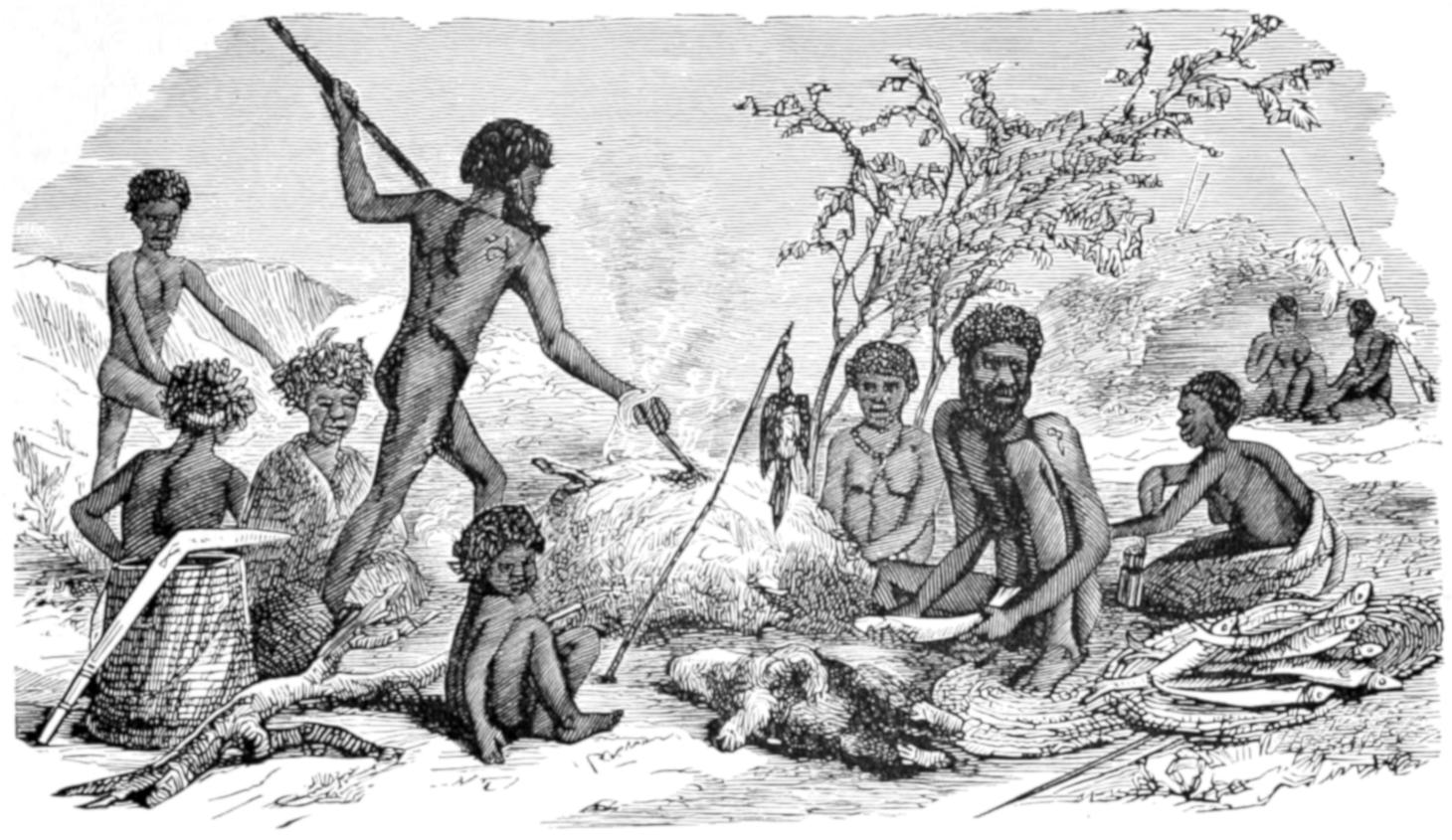

| 186. | Australian man and woman | 698 |

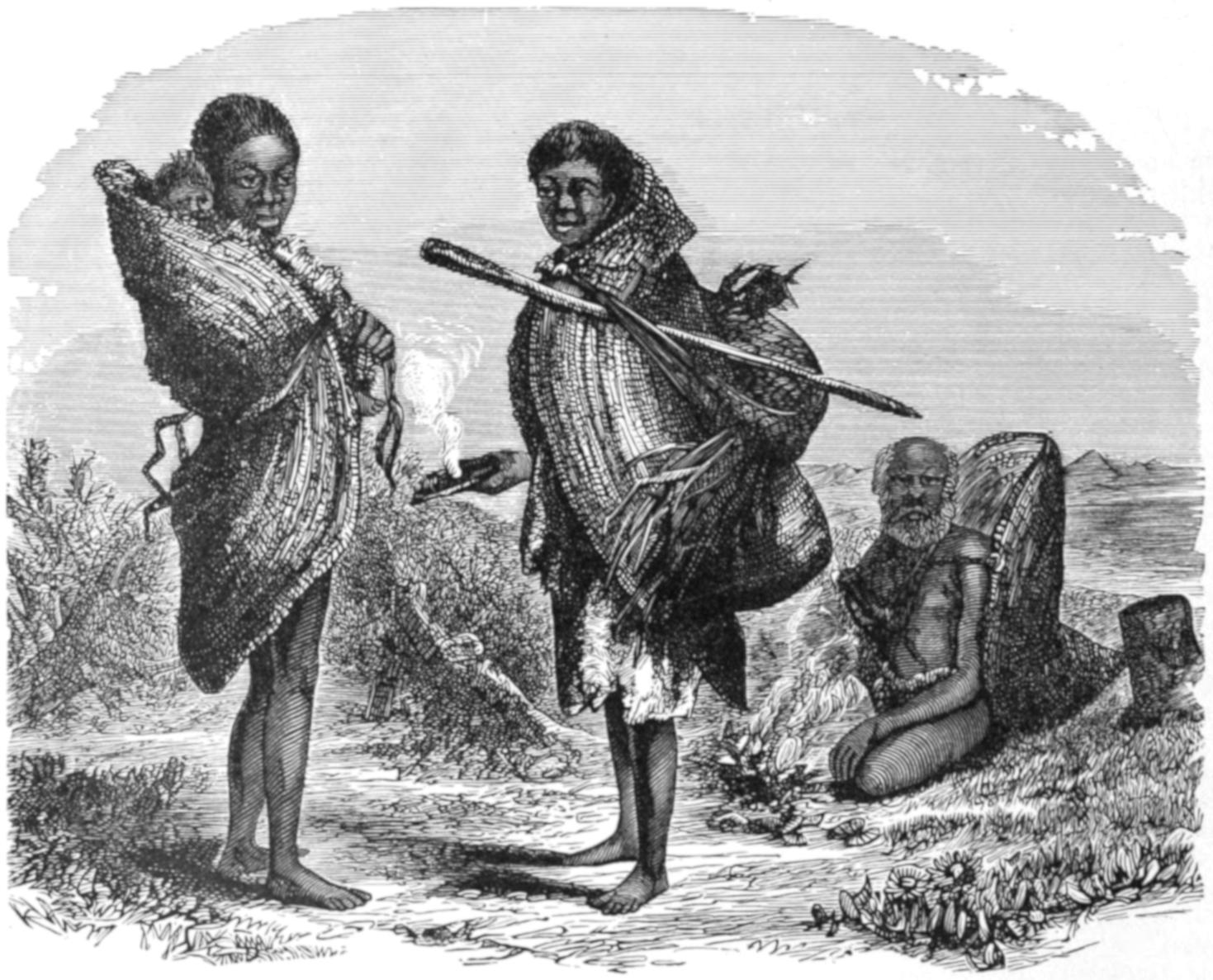

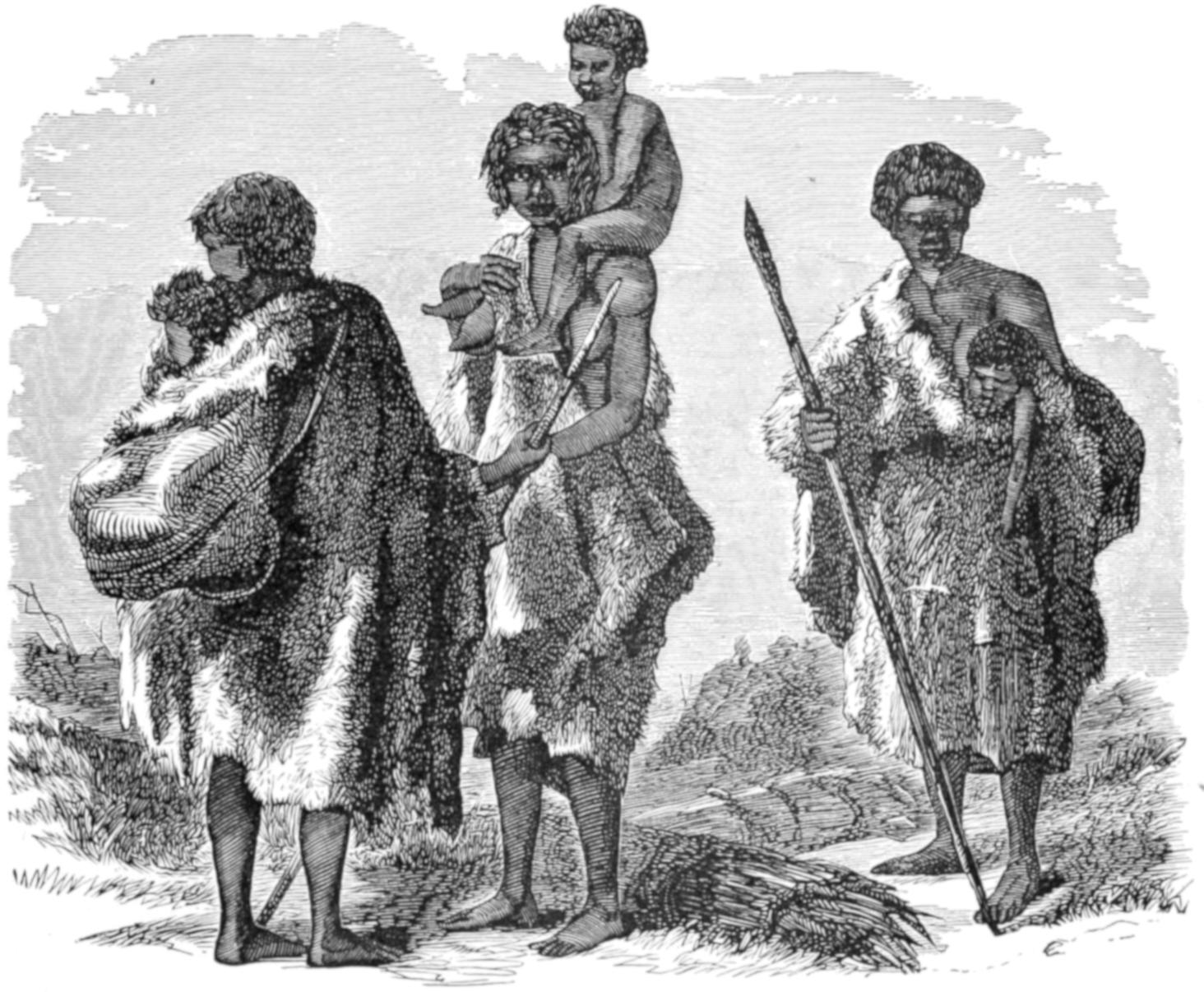

| 187. | Women and old man of Lower Murray | 698 |

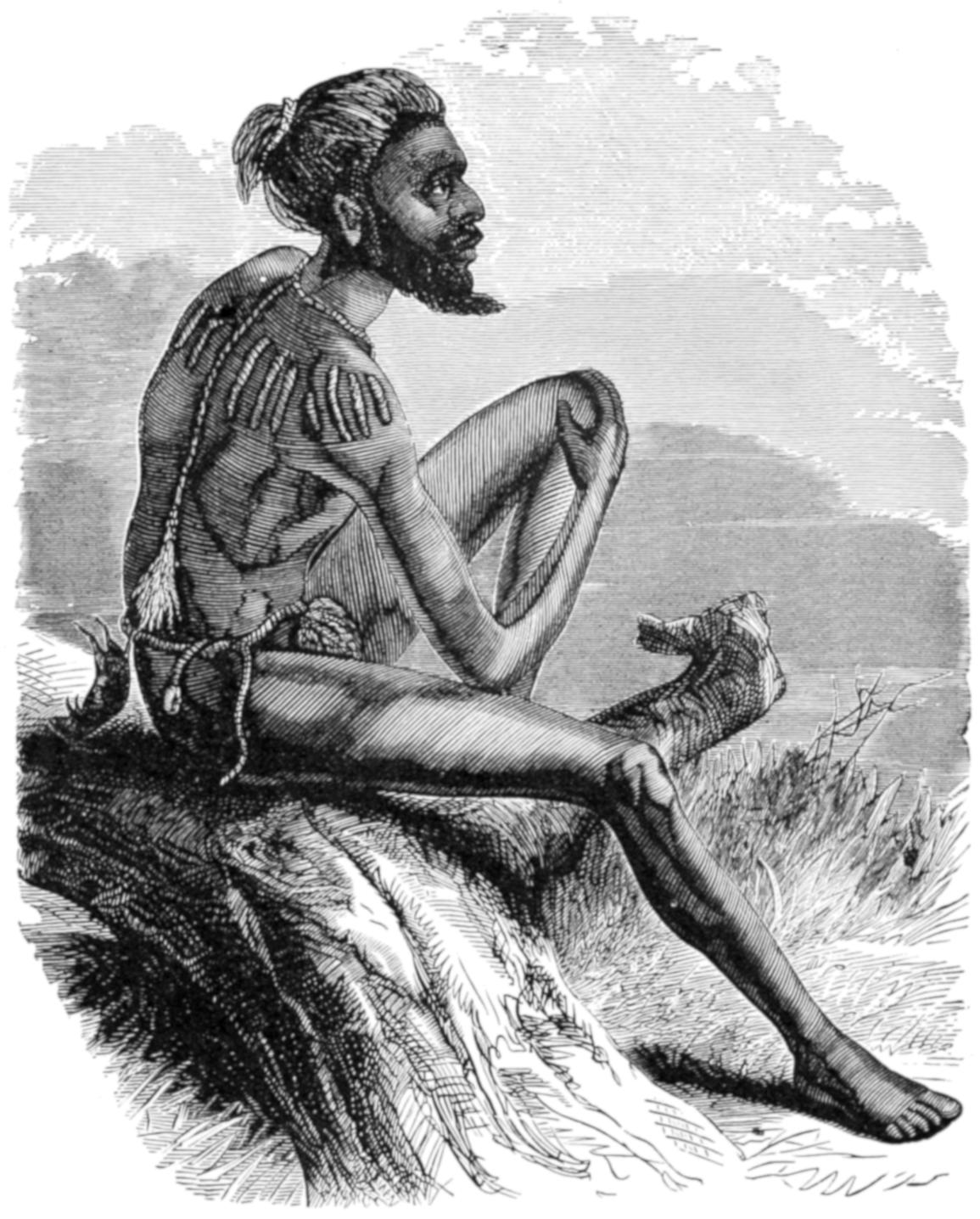

| 188. | Hunter and his day’s provision | 707 |

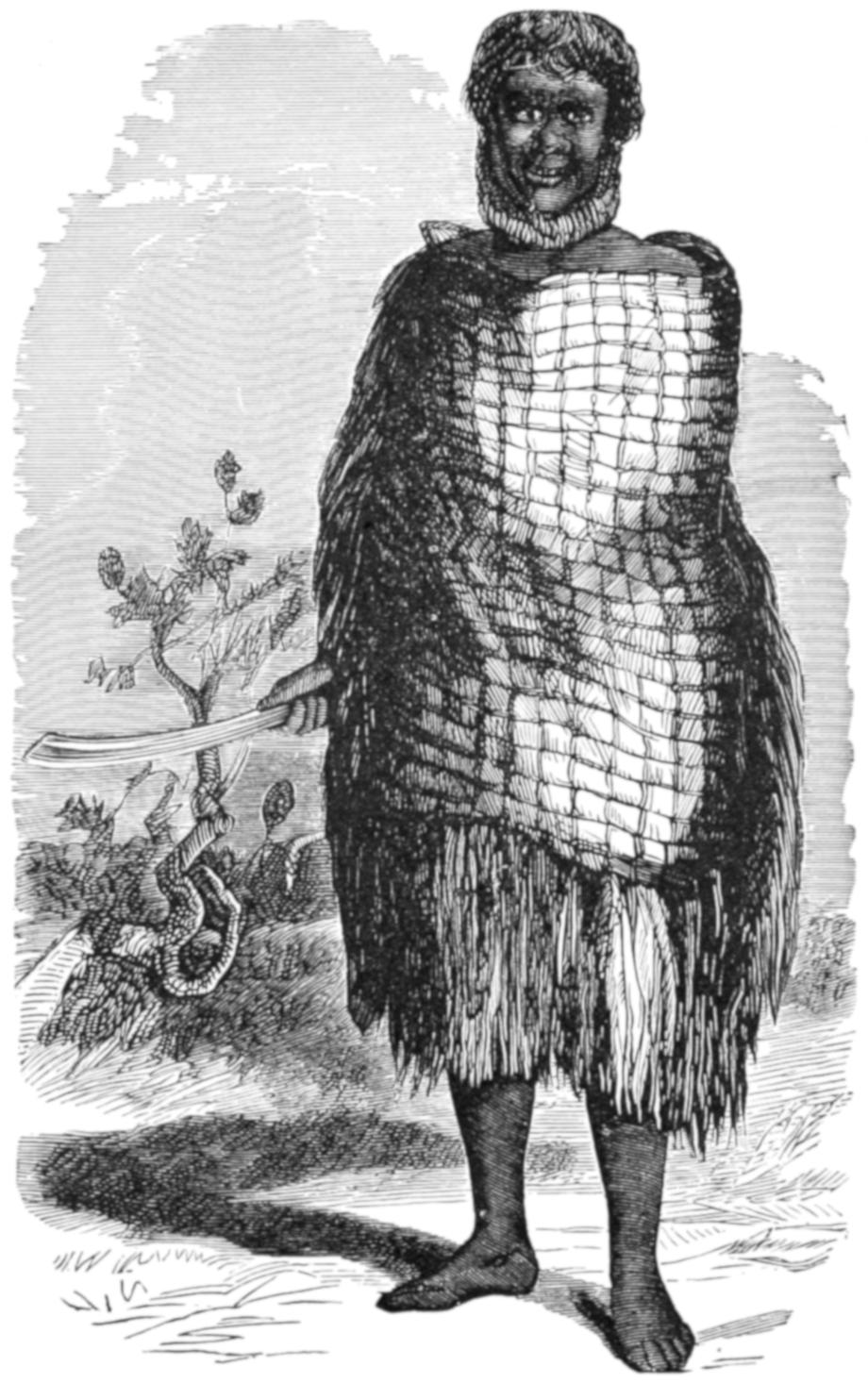

| 189. | The sea-grass cloak | 707 |

| 190. | Bee hunting | 716 |

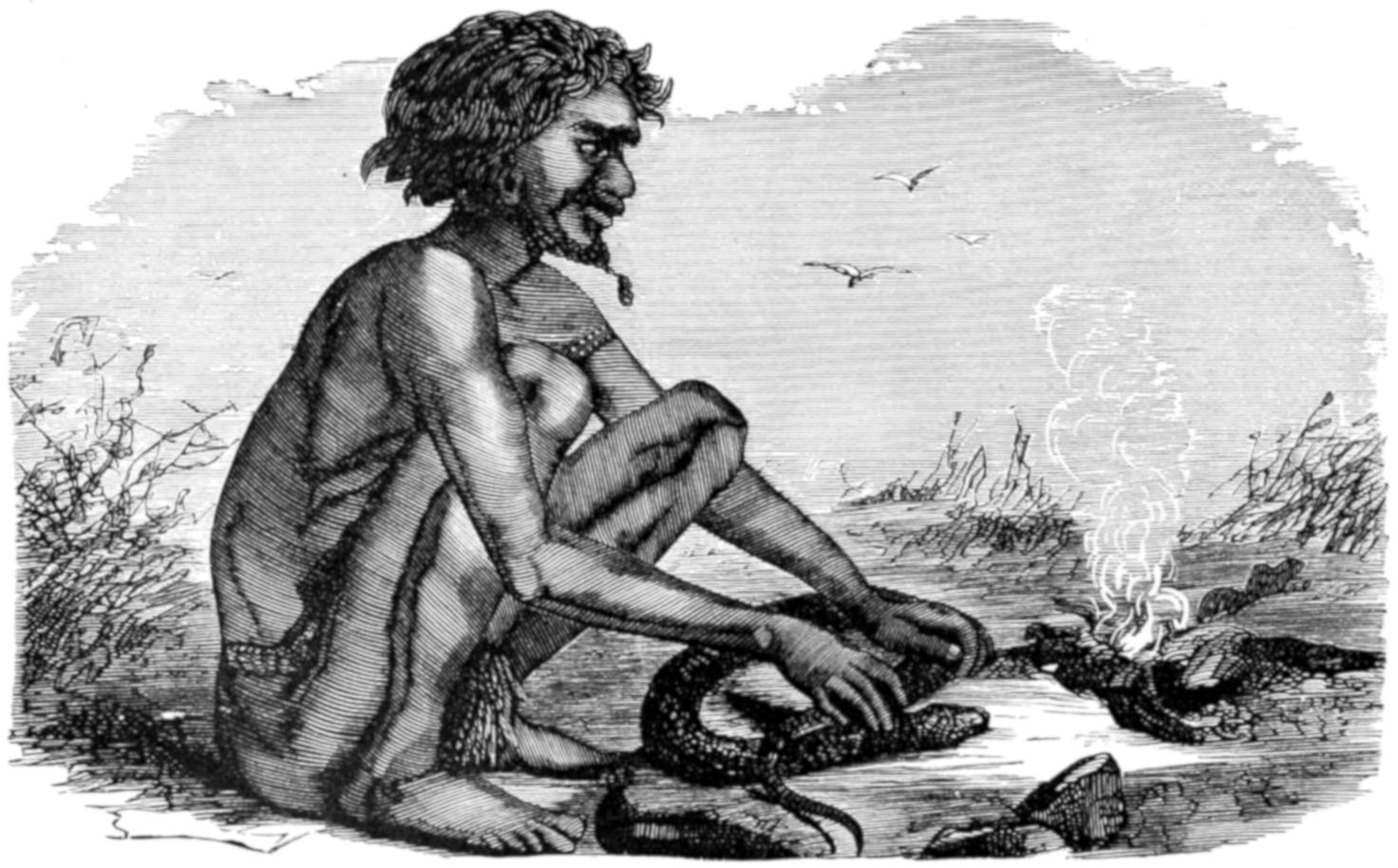

| 191. | Australian cooking a snake | 716 |

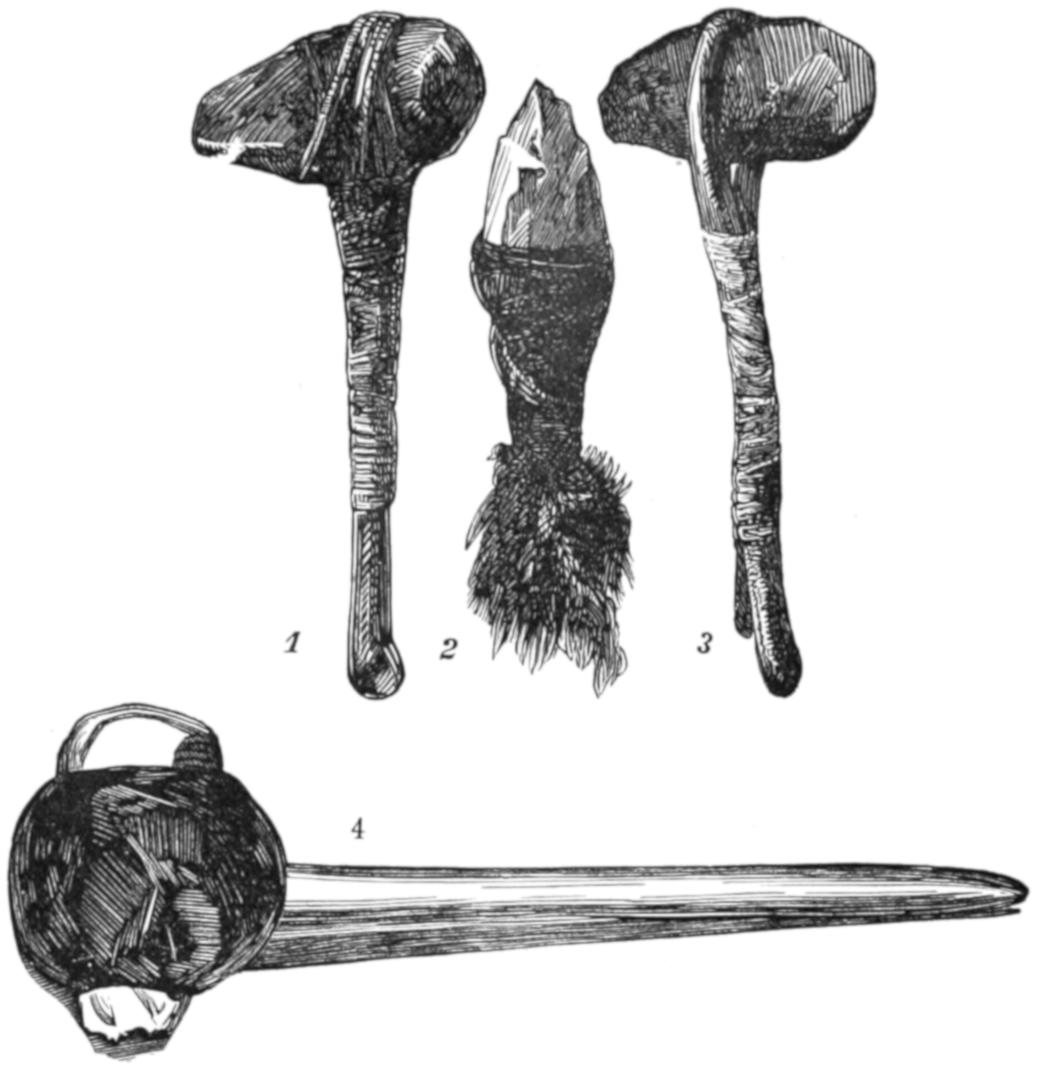

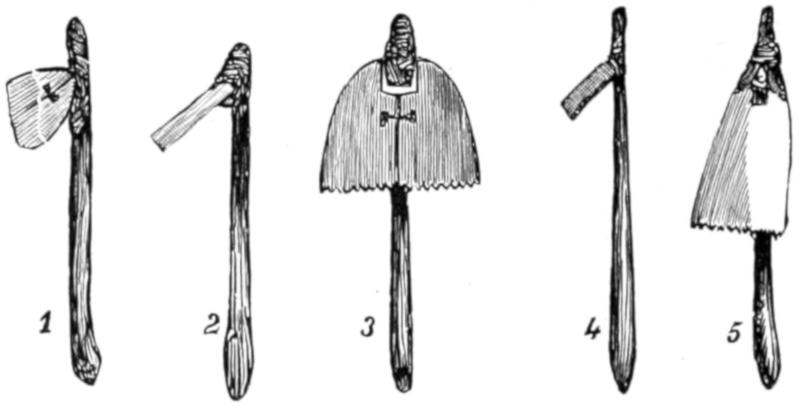

| 192. | Australian tomahawks | 722 |

| 193. | Australian clubs | 722 |

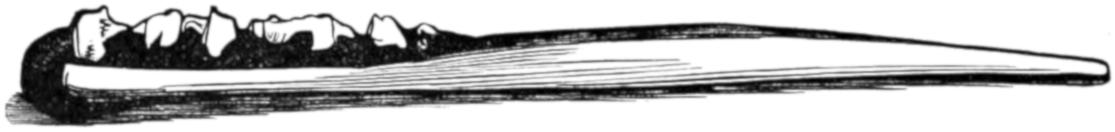

| 194. | Australian saw | 722 |

| 195. | Tattooing chisels | 722 |

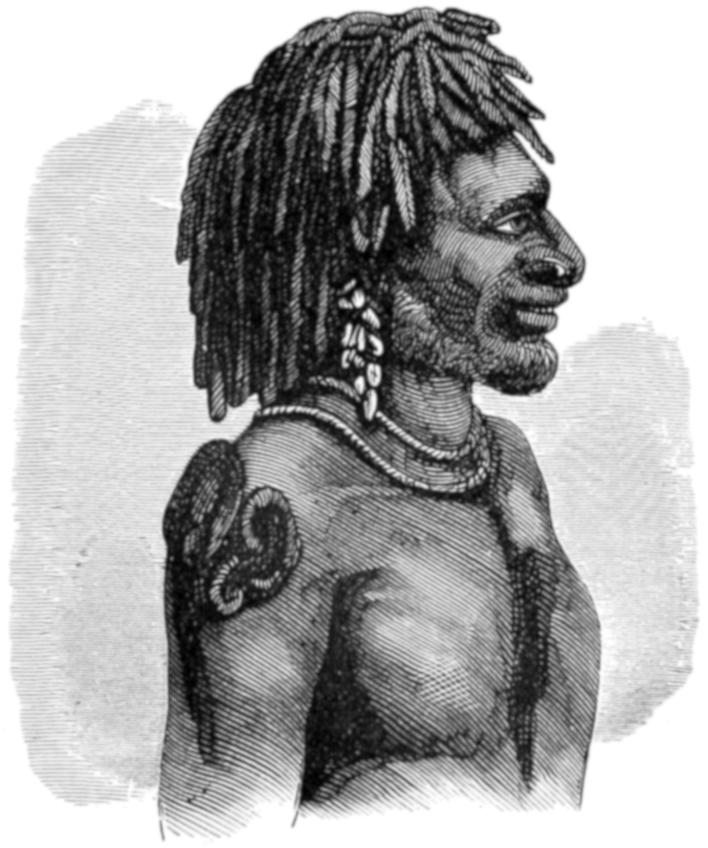

| 196. | Man of Torres Strait | 722 |

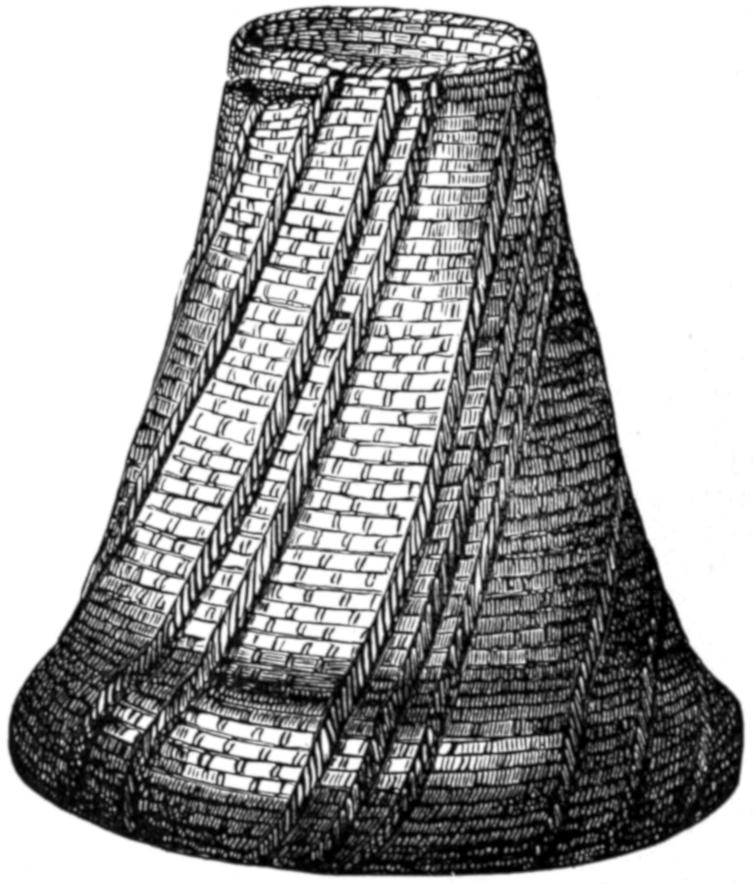

| 197. | Basket—South Australia | 722 |

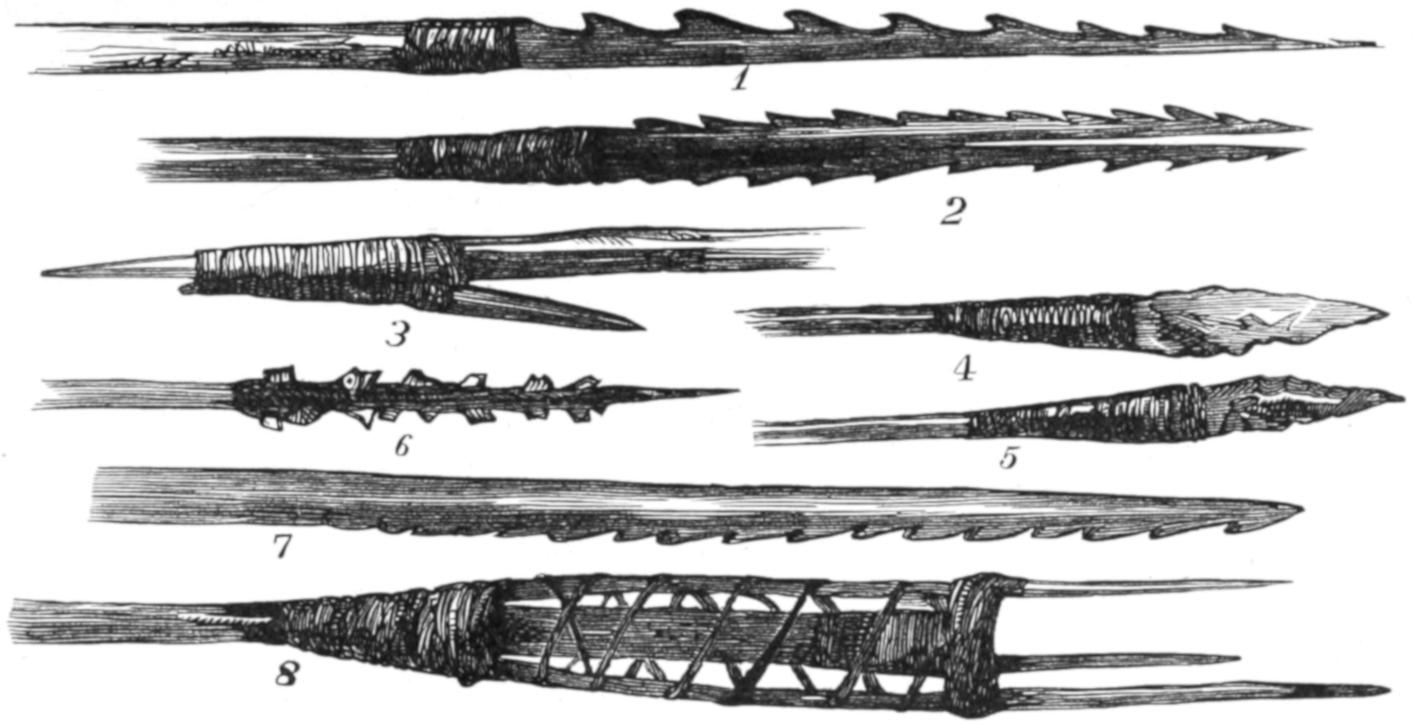

| 198. | Heads of Australian spears | 731 |

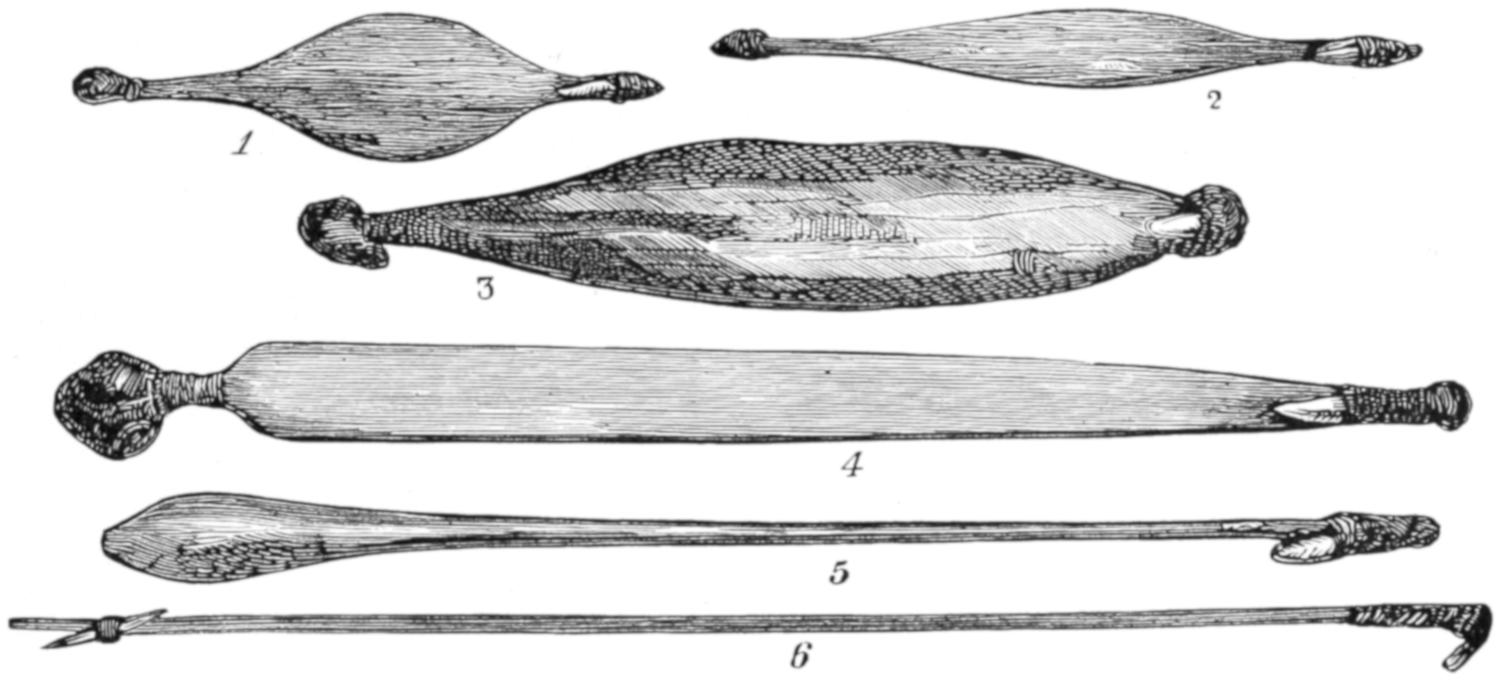

| 199. | Throw-sticks of the Australians | 731 |

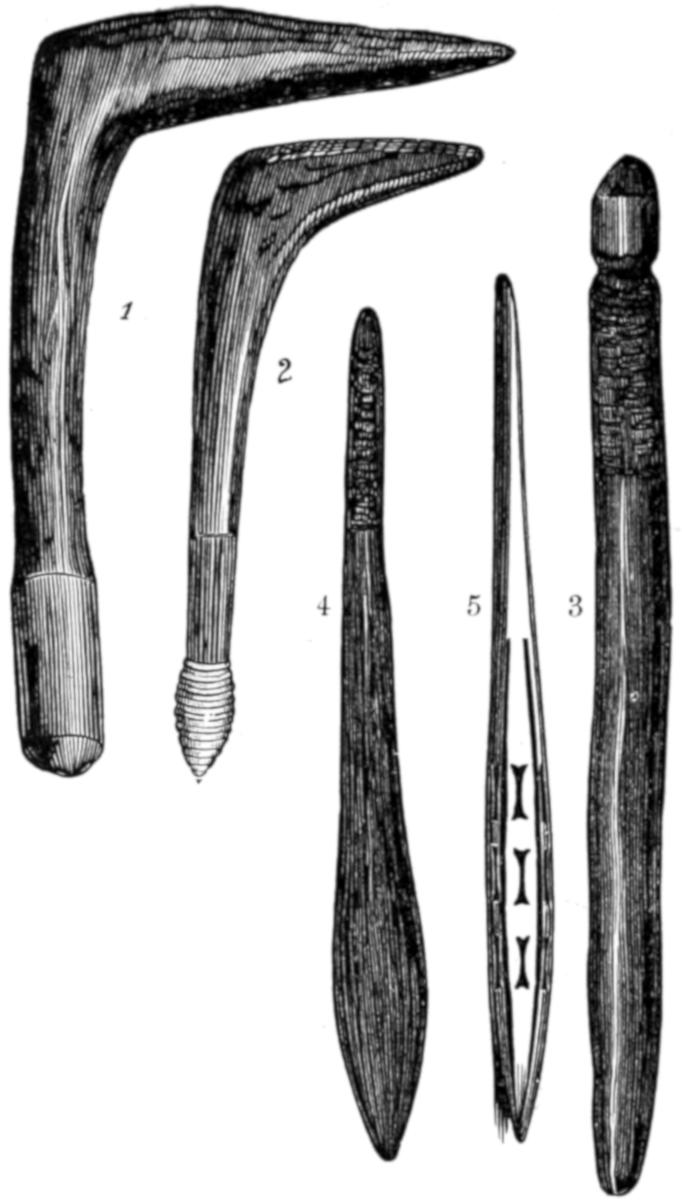

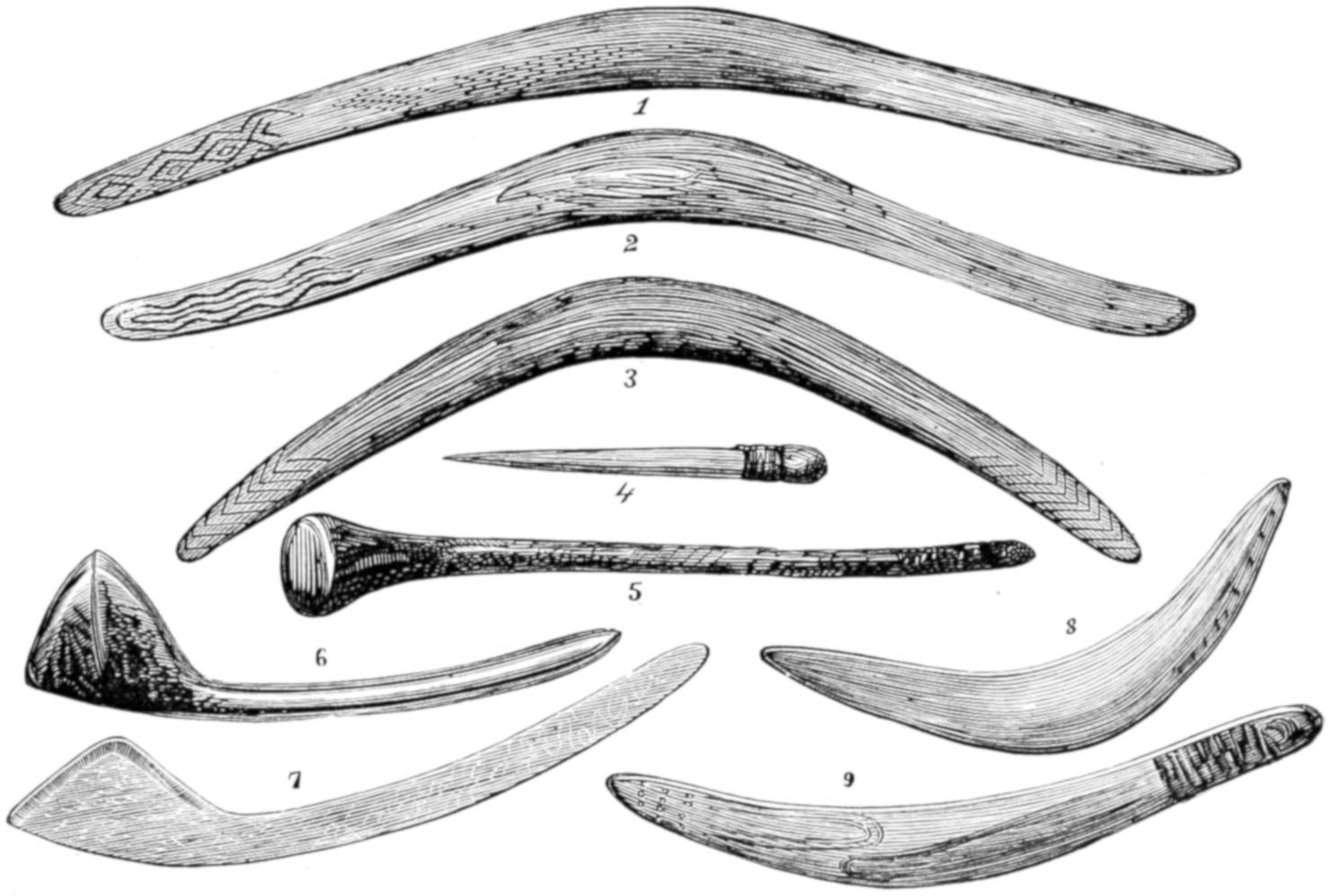

| 200. | Boomerangs of the Australians | 731 |

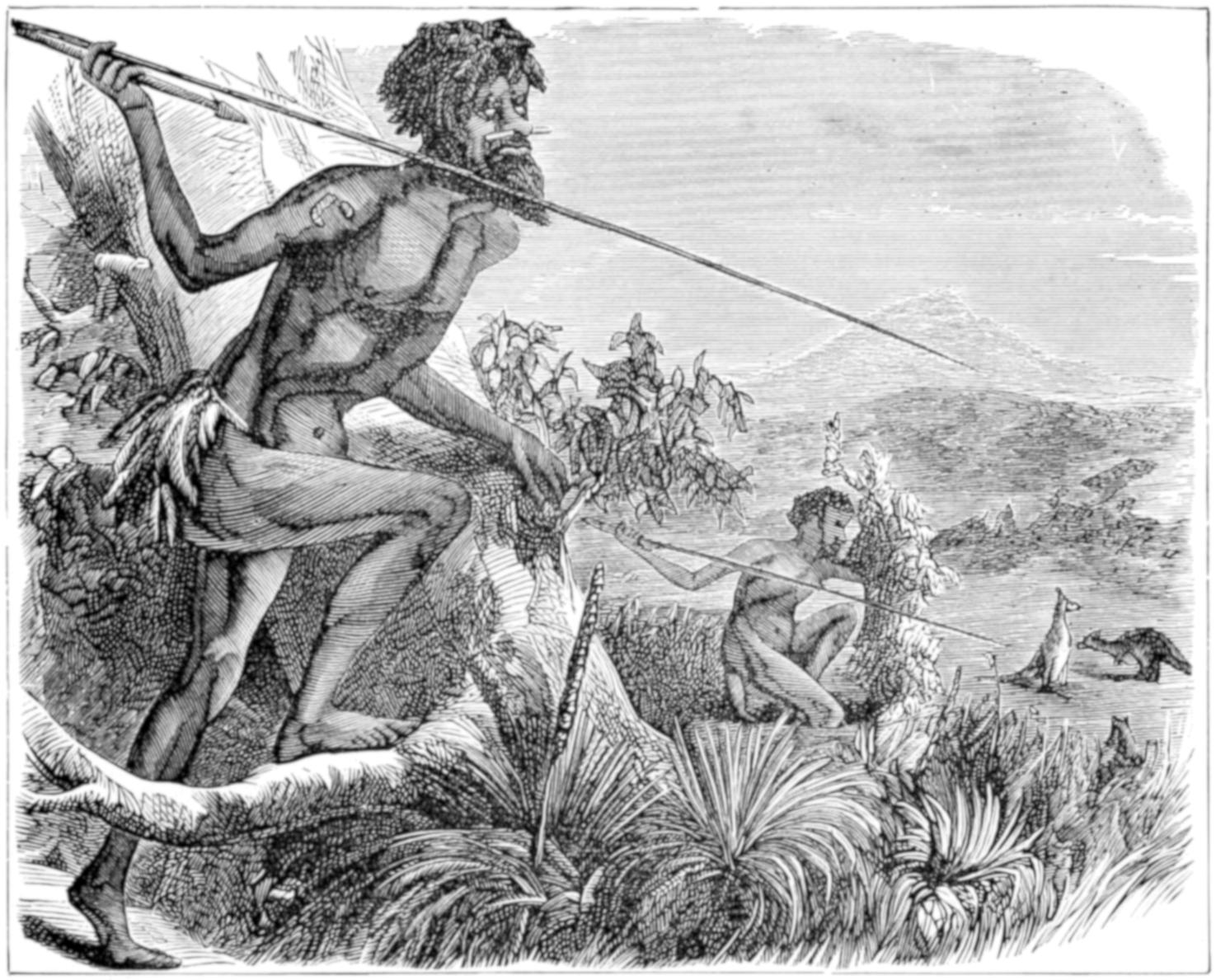

| 201. | Spearing the kangaroo | 739 |

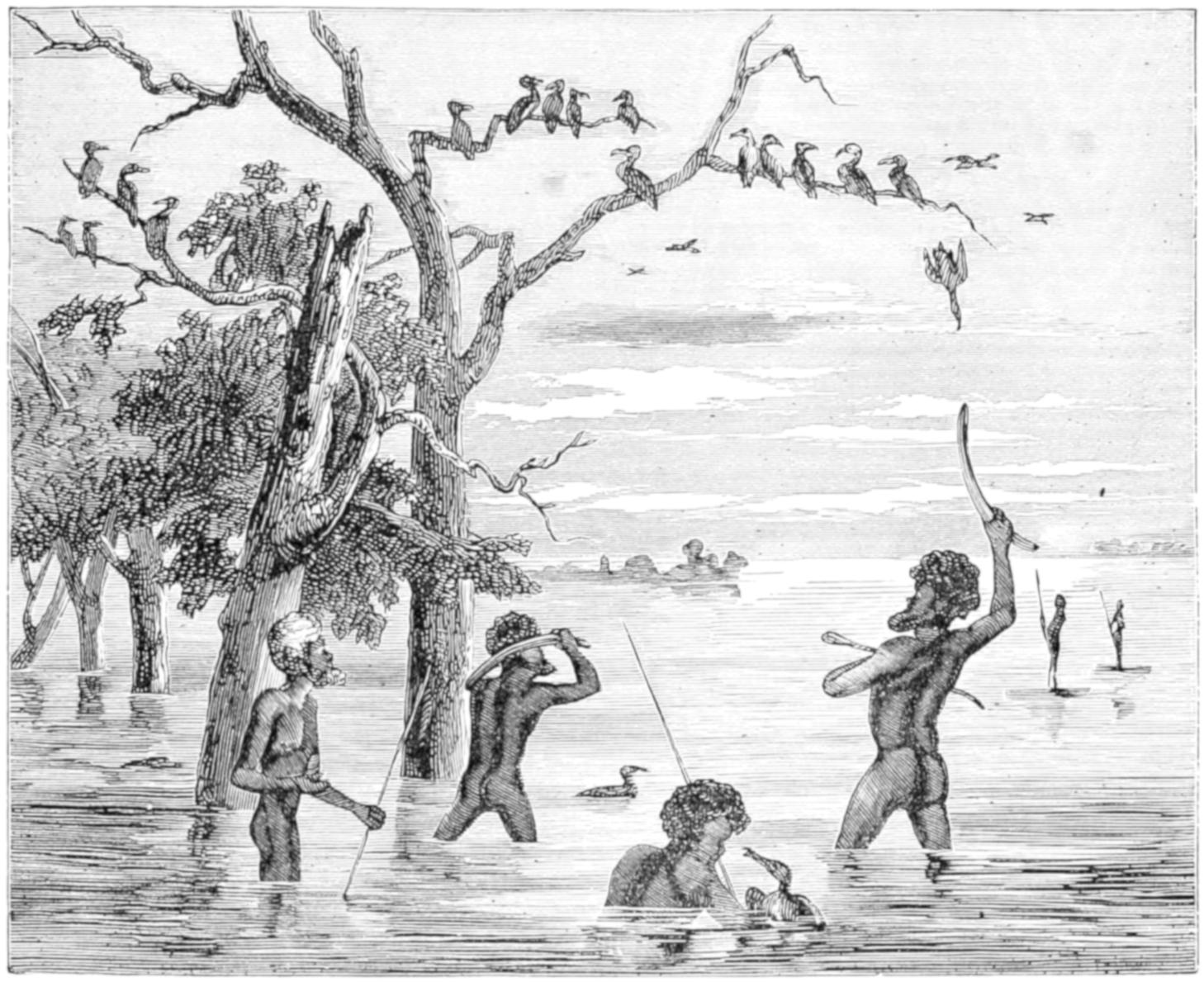

| 202. | Catching the cormorant | 739 |

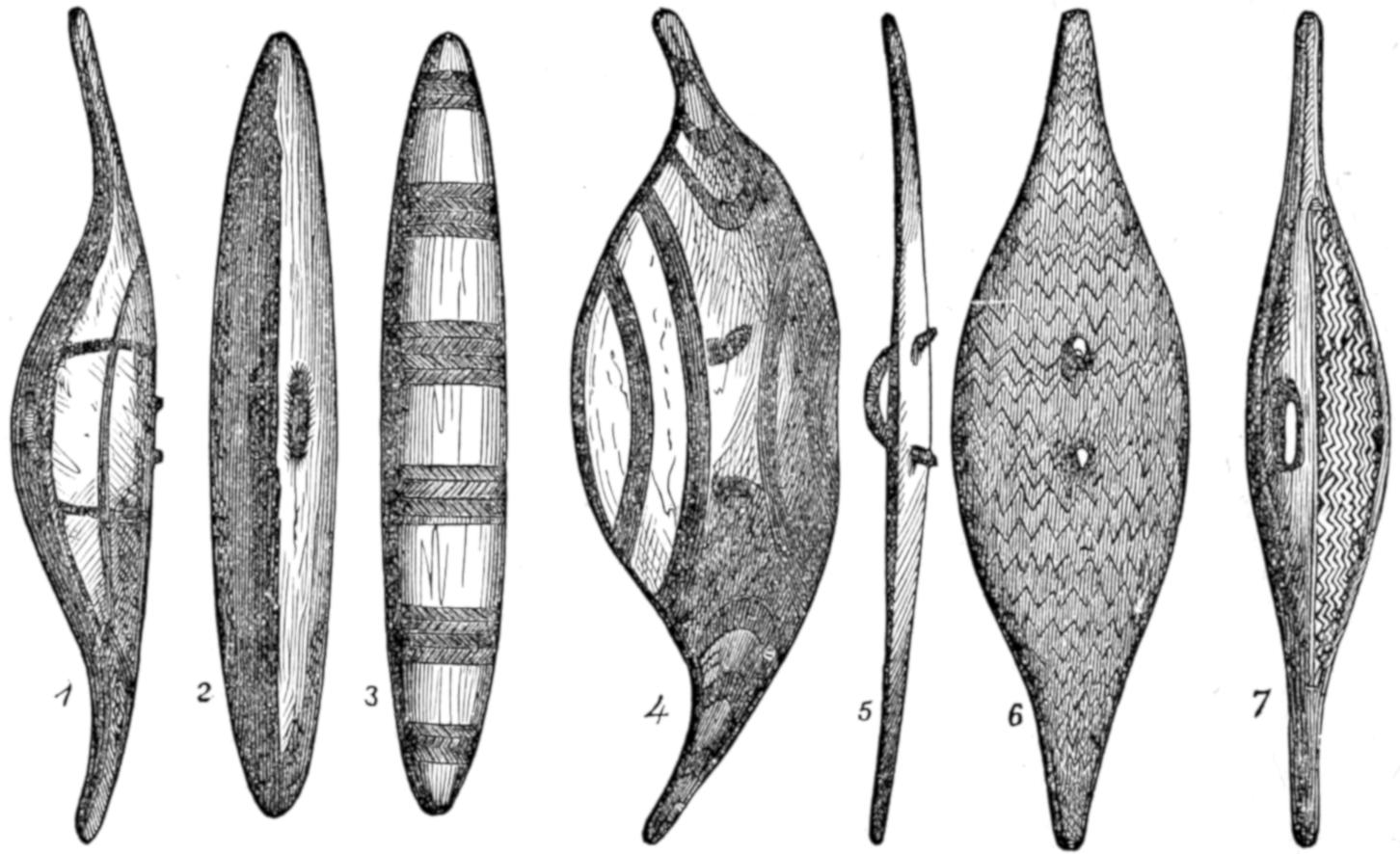

| 203. | Australian shields | 742 |

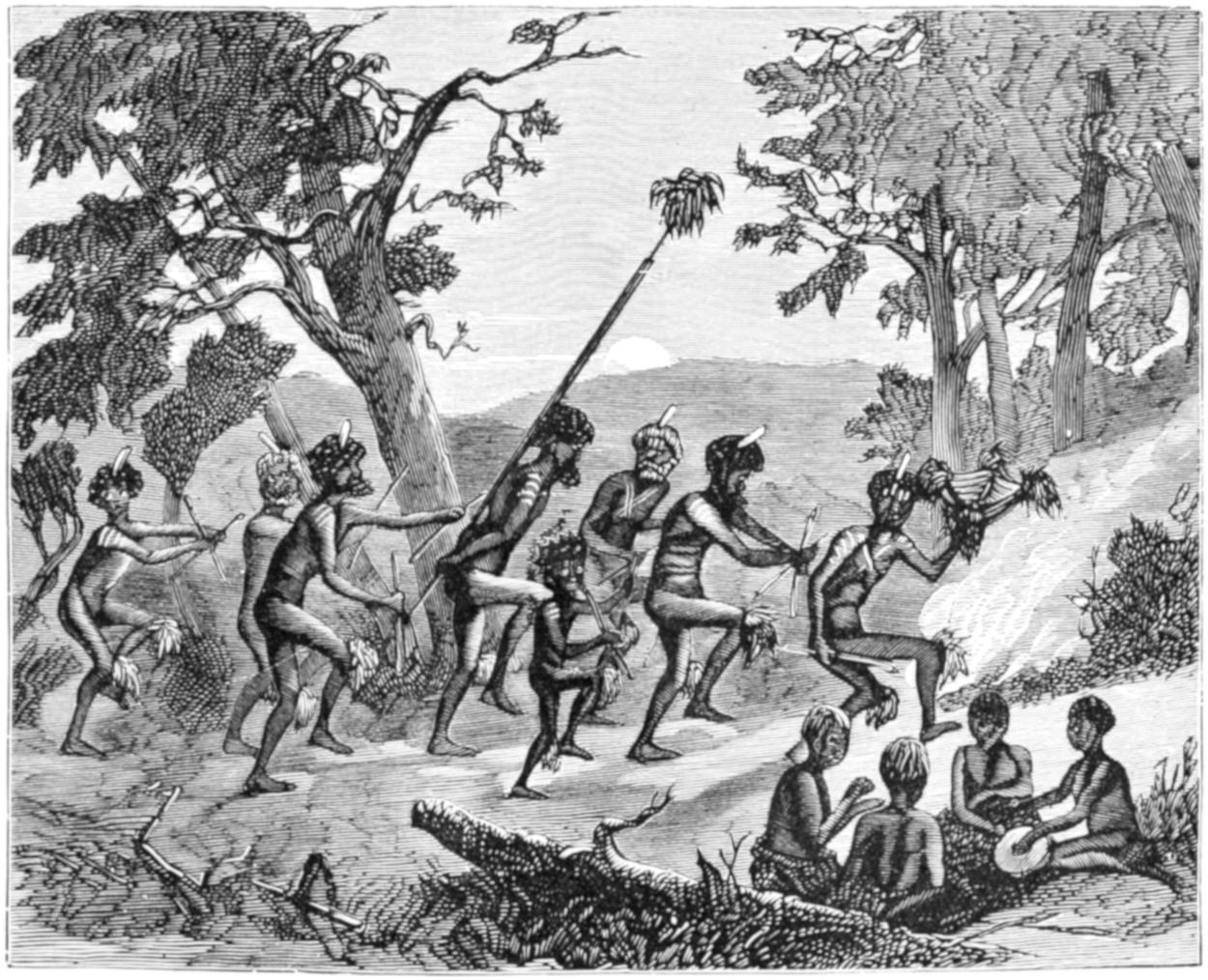

| 204. | The kuri dance | 749 |

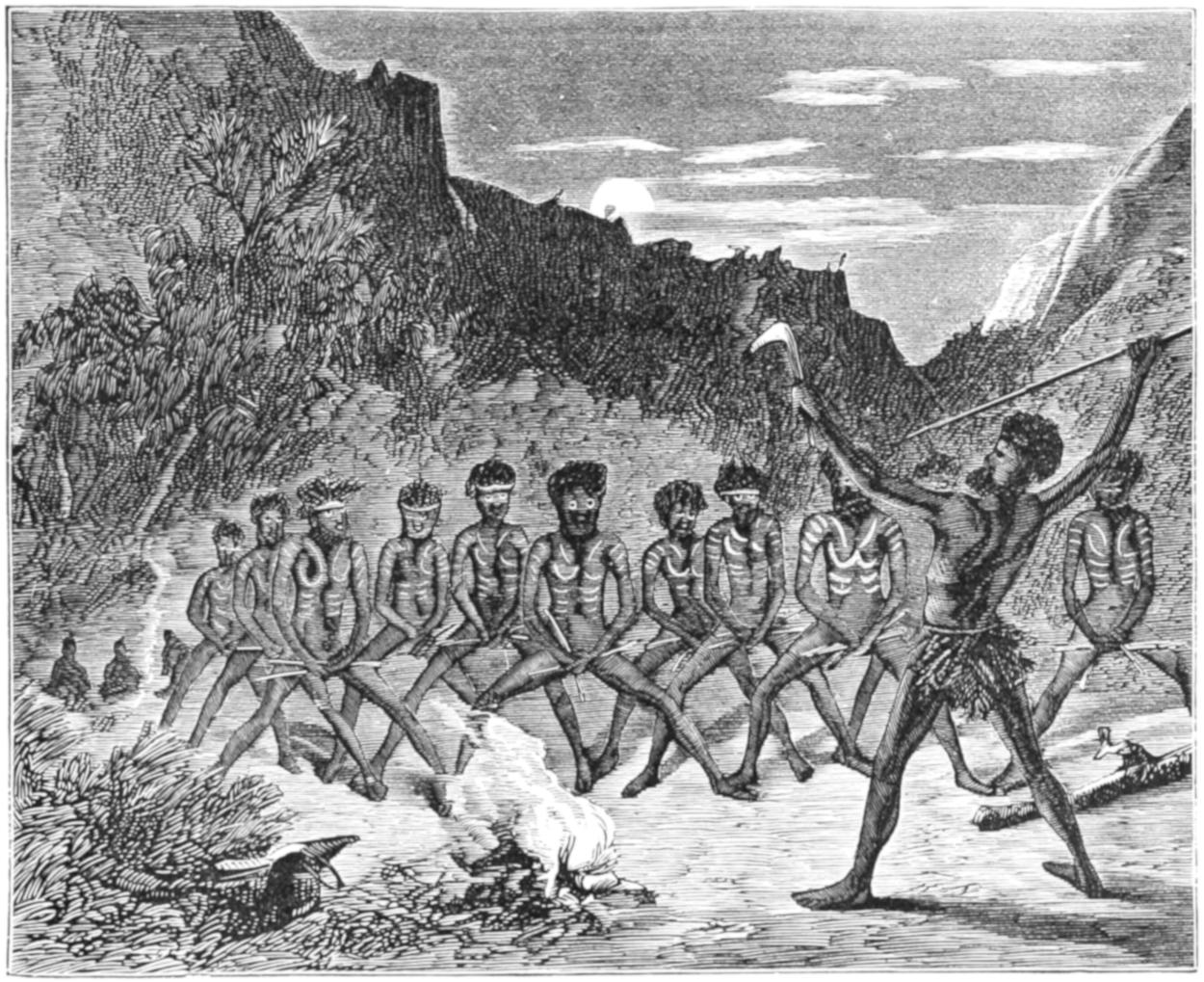

| 205. | Palti dance, or corrobboree | 749 |

| 206. | An Australian feast | 759 |

| 207. | Australian mothers | 759 |

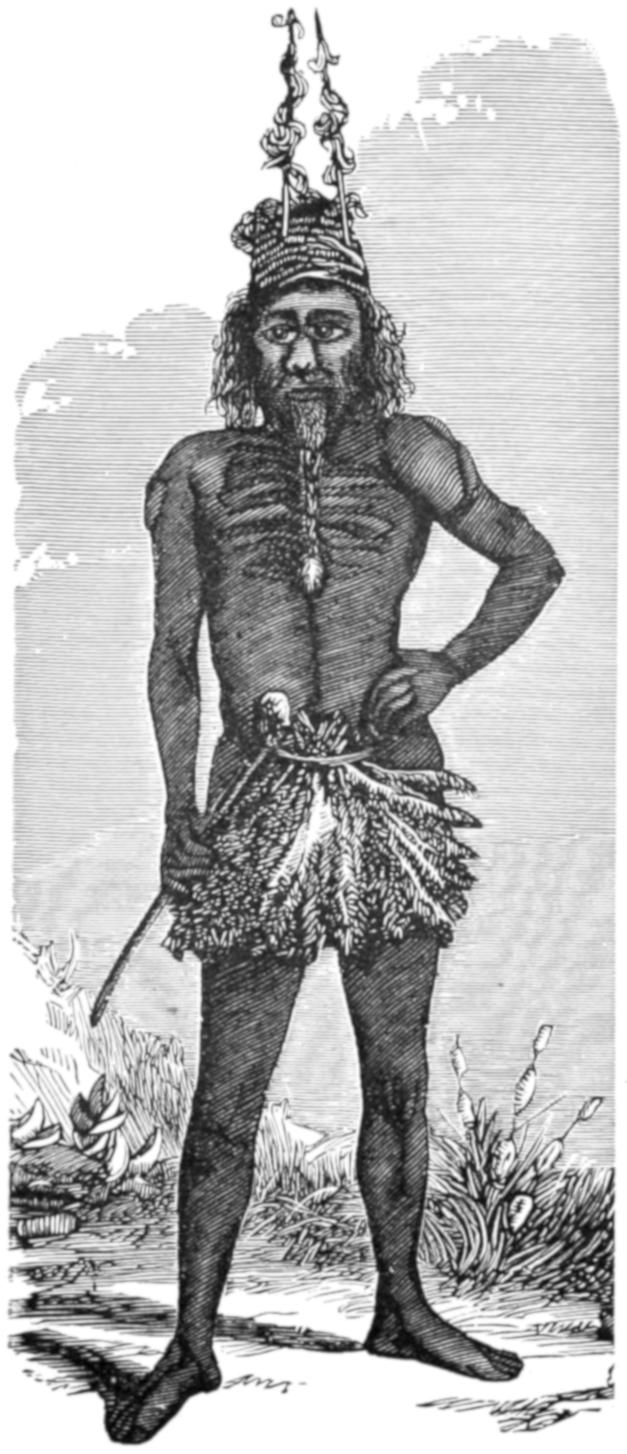

| 208. | Mintalta, a Nauo man | 765 |

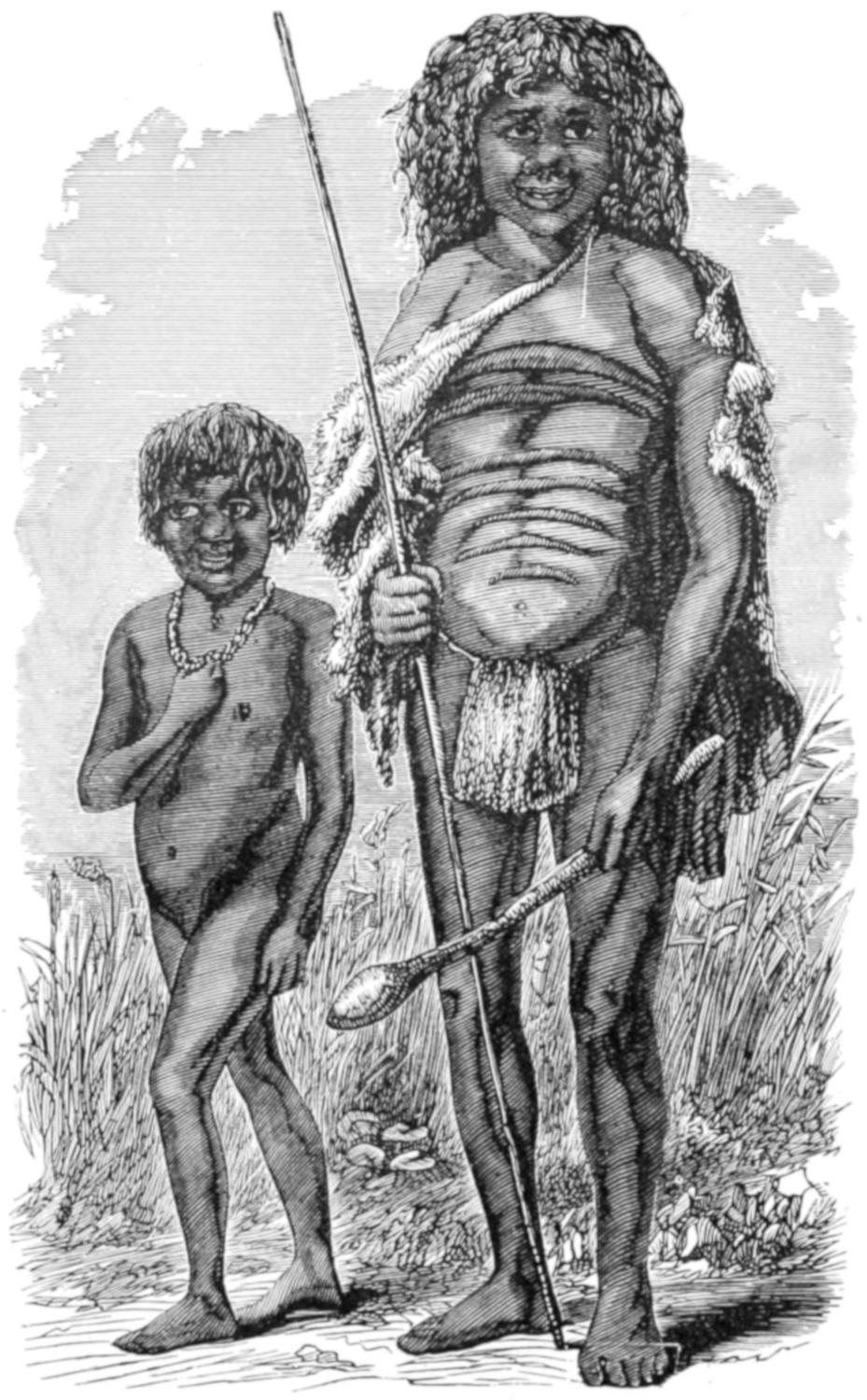

| 209. | Young man and boy of South Australia | 765 |

| 210. | Hut for cure of disease | 765 |

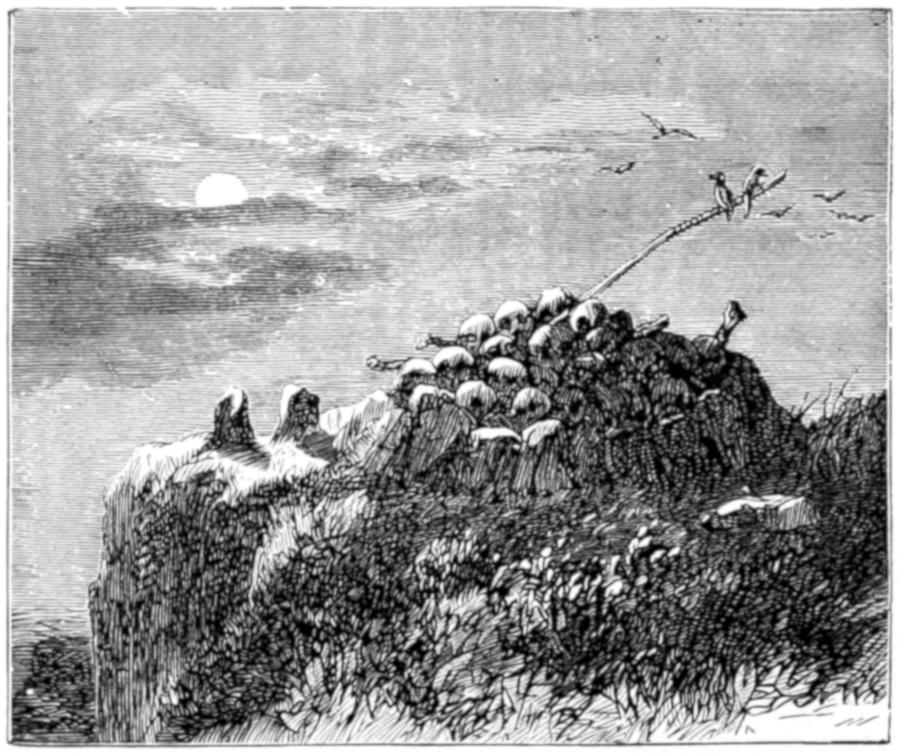

| 211. | Tomb of skulls | 765 |

| 212. | Tree tomb of Australia | 775 |

| 213. | Smoking bodies of slain warriors | 775 |

| 214. | Carved feather box[v] | 775 |

| 215. | Australian widows and their caps | 781 |

| 216. | Cave with native drawings | 781 |

| 217. | Winter huts in Australia | 787 |

| 218. | A summer encampment | 787 |

| 219. | New Zealander from childhood to age | 794 |

| 220. | Woman and boy of New Zealand | 803 |

| 221. | A tattooed chief and his wife | 803 |

| 222. | Maori women making mats | 809 |

| 223. | The Tangi | 809 |

| 224. | Parátene Maioha in his state war cloak | 820 |

| 225. | The chiefs daughter | 820 |

| 226. | Hongi-hongi, chief of Waipa | 820 |

| 227. | Maories preparing for a feast | 831 |

| 228. | Maori chiefs’ storehouses | 831 |

| 229. | Cannibal cookhouse | 835 |

| 230. | Maori pah | 835 |

| 231. | Green jade ornaments | 841 |

| 232. | Maori weapons | 841 |

| 233. | Wooden and bone merais | 841 |

| 234. | Maori war dance | 847 |

| 235. | Te Ohu, a native priest | 860 |

| 236. | A tiki at Raroera pah | 860 |

| 237. | Tiki from Whakapokoko | 860 |

| 238. | Mourning over a dead chief | 872 |

| 239. | Tomb of E’ Toki | 872 |

| 240. | Rangihaeta’s war house | 877 |

| 241. | Interior of a pah or village | 877 |

| 242. | Maori paddles | 881 |

| 243. | Green jade adze and chisel | 881 |

| 244. | Common stone adze | 881 |

| 245. | A Maori toko-toko | 881 |

| 246. | New Caledonians defending their coast | 893 |

| 247. | Andamaners cooking a pig | 893 |

| 248. | A scene in the Nicobar Islands | 903 |

| 249. | The Outanatas and their weapons | 903 |

| 250. | The monkey men of Dourga Strait | 909 |

| 251. | Canoes of New Guinea | 909 |

| 252. | Huts of New Guinea | 916 |

| 253. | Dance by torchlight in New Guinea | 916 |

| 254. | The ambassador’s message | 924 |

| 255. | The canoe in a breeze | 924 |

| 256. | Presentation of the canoe | 937 |

| 257. | A Fijian feast | 943 |

| 258. | The fate of the boaster | 943 |

| 259. | Fijian idol | 949 |

| 260. | The orator’s flapper | 949 |

| 261. | Fijian spear | 949 |

| 262. | Fijian clubs | 949 |

| 263. | A Fijian wedding | 957 |

| 264. | House thatching by Fijians | 957 |

| 265. | A Buré, or temple, in Fiji | 963 |

| 266. | View in Makira harbor | 963 |

| 267. | Man and woman of Vaté | 973 |

| 268. | Woman and child of Vanikoro | 973 |

| 269. | Daughter of Tongan chief | 973 |

| 270. | Burial of a living king | 980 |

| 271. | Interior of a Tongan house | 980 |

| 272. | The kava party in Tonga | 988 |

| 273. | Tongan plantation | 991 |

| 274. | Ceremony of inachi | 991 |

| 275. | The tow-tow | 999 |

| 276. | Consulting a priest | 999 |

| 277. | Tattooing day in Samoa | 1012 |

| 278. | Cloth making by Samoan women | 1012 |

| 279. | Samoan club | 1018 |

| 280. | Armor of Samoan warrior | 1018 |

| 281. | Beautiful paddle of Hervey Islanders | 1018 |

| 282. | Ornamented adze magnified | 1018 |

| 283. | Spear of Hervey Islanders | 1018 |

| 284. | Shark tooth gauntlets | 1025 |

| 285. | Samoan warriors exchanging defiance | 1027 |

| 286. | Pigeon catching by Samoans | 1027 |

| 287. | Battle scene in Hervey Islands | 1035 |

| 288. | Village in Kingsmill Islands | 1035 |

| 289. | Shark tooth spear | 1041 |

| 290. | Shark’s jaw | 1041 |

| 291. | Swords of Kingsmill Islanders | 1041 |

| 292. | Tattooed chiefs of Marquesas | 1046 |

| 293. | Marquesan chief’s hand | 1046 |

| 294. | Neck ornament | 1046 |

| 295. | Marquesan chief in war dress | 1046 |

| 296. | The war dance of the Niuans | 1054 |

| 297. | Tahitans presenting the cloth | 1054 |

| 298. | Dressing the idols by Society Islanders | 1067 |

| 299. | The human sacrifice by Tahitans | 1077 |

| 300. | Corpse and chief mourner | 1077 |

| 301. | Tane, the Tahitan god, returning home | 1084 |

| 302. | Women and pet pig of Sandwich Islands | 1084 |

| 303. | Kamehameha’s exploit with spears | 1089 |

| 304. | Masked rowers | 1089 |

| 305. | Surf swimming by Sandwich Islanders | 1093 |

| 306. | Helmet of Sandwich Islanders | 1097 |

| 307. | Feather idol of Sandwich Islanders | 1097 |

| 308. | Wooden idol of Sandwich Islanders | 1097 |

| 309. | Romanzoff Islanders, man and woman | 1101 |

| 310. | Dyak warrior and dusum | 1101 |

| 311. | Investiture of the rupack | 1105 |

| 312. | Warrior’s dance among Pelew Islanders | 1105 |

| 313. | Illinoan pirate and Saghai Dyak | 1113 |

| 314. | Dyak women | 1113 |

| 315. | Parang-latok of the Dyaks | 1122 |

| 316. | Sumpitans of the Dyaks | 1122 |

| 317. | Parang-ihlang of the Dyaks | 1122 |

| 318. | The kris, or dagger, of the Dyaks | 1129 |

| 319. | Shields of Dyak soldiers | 1129 |

| 320. | A parang with charms | 1129 |

| 321. | A Dyak spear | 1129 |

| 322. | Canoe fight of the Dyaks | 1139 |

| 323. | A Dyak wedding | 1139 |

| 324. | A Dyak feast | 1147 |

| 325. | A Bornean adze axe | 1152 |

| 326. | A Dyak village | 1153 |

| 327. | A Dyak house | 1153 |

| 328. | Fuegian man and woman | 1163 |

| 329. | Patagonian man and woman | 1163 |

| 330. | A Fuegian settlement | 1169 |

| 331. | Fuegians shifting quarters | 1169 |

| 332. | Araucanian stirrups and spur | 1175 |

| 333. | Araucanian lassos | 1175 |

| 334. | Patagonian bolas | 1175 |

| 335. | Spanish bit and Patagonian fittings | 1175 |

| 336. | Patagonians hunting game | 1180 |

| 337. | Patagonian village | 1187 |

| 338. | Patagonian burial ground[vi] | 1187 |

| 339. | A Mapuché family | 1201 |

| 340. | Araucanian marriage | 1201 |

| 341. | Mapuché medicine | 1207 |

| 342. | Mapuché funeral | 1207 |

| 343. | The macana club | 1212 |

| 344. | Guianan arrows and tube | 1214 |

| 345. | Gran Chaco Indians on the move | 1218 |

| 346. | The ordeal of the “gloves” | 1218 |

| 347. | Guianan blow guns | 1225 |

| 348. | Guianan blow-gun arrow | 1225 |

| 349. | Guianan winged arrows | 1225 |

| 350. | Guianan cotton basket | 1225 |

| 351. | Guianan quiver | 1225 |

| 352. | Guianan arrows rolled around stick | 1225 |

| 353. | Guianan arrows strung | 1225 |

| 354. | Feathered arrows of the Macoushies | 1231 |

| 355. | Cassava dish of the Macoushies | 1231 |

| 356. | Guianan quake | 1231 |

| 357. | Arrow heads of the Macoushies | 1231 |

| 358. | Guianan turtle arrow | 1231 |

| 359. | Guianan quiver for arrow heads | 1231 |

| 360. | Feather apron of the Mundurucús | 1231 |

| 361. | Head-dresses of the Macoushies | 1238 |

| 362. | Guianan clubs | 1238 |

| 363. | Guianan cradle | 1238 |

| 364. | A Warau house | 1244 |

| 365. | Lake dwellers of the Orinoco | 1244 |

| 366. | Guianan tipiti and bowl | 1249 |

| 367. | Guianan twin bottles | 1249 |

| 368. | Feather apron of the Caribs | 1249 |

| 369. | Bead apron of the Guianans | 1249 |

| 370. | The spathe of the Waraus | 1249 |

| 371. | The Maquarri dance | 1260 |

| 372. | Shield wrestling of the Waraus | 1260 |

| 373. | Jaguar bone flute of the Caribs | 1265 |

| 374. | Rattle of the Guianans | 1265 |

| 375. | Mexican stirrups | 1265 |

| 376. | Iron and stone tomahawks | 1265 |

| 377. | Indian shield and clubs | 1265 |

| 378. | Mandan chief Mah-to-toh-pa and wife | 1277 |

| 379. | A Crow chief | 1284 |

| 380. | American Indians scalping | 1284 |

| 381. | Flint-headed arrow | 1290 |

| 382. | Camanchees riding | 1291 |

| 383. | “Smoking” horses | 1291 |

| 384. | Snow shoe | 1295 |

| 385. | Bison hunting scene | 1299 |

| 386. | Buffalo dance | 1299 |

| 387. | The Mandan ordeal | 1305 |

| 388. | The last race | 1305 |

| 389. | The medicine man at work | 1311 |

| 390. | The ball play of the Choctaws | 1311 |

| 391. | Indian pipes | 1315 |

| 392. | Ee-e-chin-che-a in war costume | 1318 |

| 393. | Grandson of a Blackfoot chief | 1318 |

| 394. | Pshan-shaw, a girl of the Riccarees | 1318 |

| 395. | Flat-head woman and child | 1319 |

| 396. | Indian canoe | 1322 |

| 397. | Snow shoe dance | 1322 |

| 398. | Dance to the medicine of the brave | 1322 |

| 399. | The canoe race | 1327 |

| 400. | Esquimaux dwellings | 1327 |

| 401. | Esquimaux harpoon head | 1337 |

| 402. | Burial of Blackbird, an Omaha chief | 1341 |

| 403. | Esquimaux spearing the walrus | 1341 |

| 404. | The kajak and its management | 1347 |

| 405. | Esquimaux sledge driving | 1347 |

| 406. | Wrist-guard of the Esquimaux | 1353 |

| 407. | Esquimaux fish-hooks | 1353 |

| 408. | Feathered arrows of Aht tribe | 1356 |

| 409. | Ingenious fish-hook of the Ahts | 1357 |

| 410. | Remarkable carved pipes of the Ahts | 1357 |

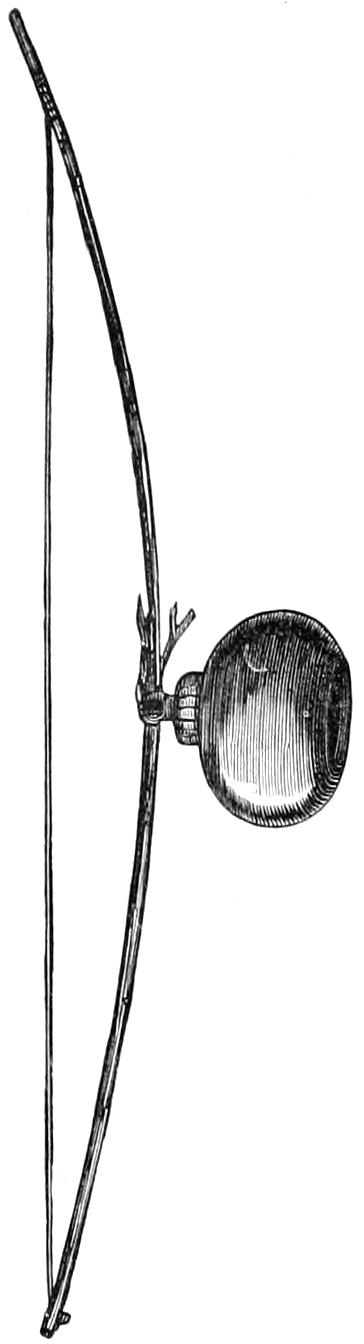

| 411. | Bow of the Ahts of Vancouver’s Island | 1357 |

| 412. | Beaver mask of the Aht tribe | 1357 |

| 413. | Singular head-dress of the Aht chiefs | 1357 |

| 414. | Decorated paddles of the Ahts | 1357 |

| 415. | Canoe of the Ahts | 1361 |

| 416. | Aht dance | 1367 |

| 417. | Initiation of a dog eater | 1367 |

| 418. | A Sowrah marriage | 1387 |

| 419. | A Meriah sacrifice | 1387 |

| 420. | Bows and quiver of Hindoos | 1394 |

| 421. | Ingenious ruse of Bheel robbers | 1397 |

| 422. | A Ghoorka attacked by a tiger | 1397 |

| 423. | A Ghoorka necklace | 1403 |

| 424. | A kookery of the Ghoorka tribe | 1403 |

| 425. | The chakra or quoit weapon | 1403 |

| 426. | Indian arms and armor | 1403 |

| 427. | Suit of armor inlaid with gold | 1406 |

| 428. | Chinese repeating crossbow | 1425 |

| 429. | Mutual assistance | 1427 |

| 430. | Chinese woman’s foot and shoe | 1428 |

| 431. | Mandarin and wife | 1437 |

| 432. | Various modes of torture | 1437 |

| 433. | Mouth organ | 1445 |

| 434. | Specimens of Chinese art | 1446 |

| 435. | Decapitation of Chinese criminal | 1451 |

| 436. | The street ballad-singer | 1451 |

| 437. | Japanese lady in a storm | 1454 |

| 438. | Japanese lady on horseback | 1455 |

| 439. | Capture of the truant husbands | 1464 |

| 440. | Candlestick and censers | 1465 |

| 441. | Suit of Japanese armor | 1469 |

| 442. | King S. S. P. M. Mongkut of Siam | 1469 |

| 443. | Portrait of celebrated Siamese actress | 1469 |

[vii]

| Chap. | Page. | |

|---|---|---|

| KAFFIRS OF SOUTH AFRICA. | ||

| I. | Intellectual Character | 11 |

| II. | Course of Life | 17 |

| III. | Course of Life—Concluded | 20 |

| IV. | Masculine Dress and Ornaments | 28 |

| V. | Masculine Dress and Ornaments—Concluded | 36 |

| VI. | Feminine Dress and Ornaments | 48 |

| VII. | Architecture | 56 |

| VIII. | Cattle Keeping | 66 |

| IX. | Marriage | 75 |

| X. | Marriage—Concluded | 82 |

| XI. | War—Offensive Weapons | 92 |

| XII. | War—Defensive Weapons | 108 |

| XIII. | Hunting | 126 |

| XIV. | Agriculture | 138 |

| XV. | Food | 143 |

| XVI. | Social Characteristics | 159 |

| XVII. | Religion and Superstition | 169 |

| XVIII. | Religion and Superstition—Continued | 180 |

| XIX. | Superstition—Concluded | 192 |

| XX. | Funeral Rites | 200 |

| XXI. | Domestic Life | 206 |

| HOTTENTOTS. | ||

| XXII. | The Hottentot Races | 217 |

| XXIII. | Marriage, Language, Amusements | 232 |

| THE BOSJESMAN, OR BUSHMAN. | ||

| XXIV. | Appearance—Social Life | 242 |

| XXV. | Architecture—Weapons | 251 |

| XXVI. | Amusements | 262 |

| VARIOUS AFRICAN RACES. | ||

| XXVII. | Korannas and Namaquas | 269 |

| XXVIII. | The Bechuanas | 280 |

| XXIX. | The Bechuanas—Concluded | 291 |

| XXX. | The Damara Tribe | 304 |

| XXXI. | The Ovambo, or Ovampo | 315 |

| XXXII. | The Makololo Tribe | 324 |

| XXXIII. | The Bayeye and Makoba | 337 |

| XXXIV. | The Batoka and Manganja | 348 |

| XXXV. | The Banyai and Badema | 361 |

| XXXVI. | The Balondo, or Balonda, and Angolese | 369 |

| XXXVII. | Wagogo and Wanyamuezi | 384 |

| XXXVIII. | Karague | 399 |

| XXXIX. | The Watusi and Waganda | 408 |

| XL. | The Wanyoro | 422 |

| XLI. | Gani, Madi, Obbo, and Kytch | 429 |

| XLII. | The Neam-Nam, Dôr, and Djour tribes | 440 |

| XLIII. | The Latooka tribe | 453 |

| XLIV. | The Shir, Bari, Djibba, Nuehr, Dinka, and Shillook tribes | 461 |

| XLV. | The Ishogo, Ashango, and Obongo tribes | 475 |

| XLVI. | The Apono and Apingi | 484 |

| XLVII. | The Bakalai | 491 |

| XLVIII. | The Ashira | 496 |

| XLIX. | The Camma or Commi | 504 |

| L. | The Shekiani and Mpongwé | 521 |

| LI. | The Fans | 529 |

| LII. | The Fans—Concluded | 535 |

| LIII. | The Krumen and Fanti | 544 |

| LIV. | The Ashanti | 554 |

| LV. | Dahome | 561 |

| LVI. | Dahome—Continued | 573 |

| LVII. | Dahome—Concluded | 581 |

| LVIII. | The Egbas | 590 |

| LIX. | Bonny | 600 |

| LX. | The Man-dingoes | 607 |

| LXI. | The Bubes and Congoese | 610 |

| LXII. | Bornu | 620 |

| LXIII. | The Shooas, Tibboos, Tuaricks, Begharmis, and Musguese | 628 |

| LXIV. | Abyssinians | 641 |

| LXV. | Abyssinians—Continued | 649 |

| LXVI. | Abyssinians—Concluded | 658 |

| LXVII. | Nubians and Hamran Arabs | 673 |

| LXVIII. | Bedouins, Hassaniyehs, and Malagasy | 681 |

| AUSTRALIA. | ||

| LXIX. | Appearance and Character of Natives | 694 |

| LXX. | Dress—Food | 703 |

| LXXI. | Weapons | 719 |

| LXXII. | Weapons—Concluded | 727 |

| LXXIII. | War—Amusements | 744 |

| LXXIV. | Domestic Life | 755 |

| LXXV. | From Childhood to Manhood | 761 |

| Chap. | Page. | |

|---|---|---|

| LXXVI. | Medicine—Surgery—Disposal of Dead | 769 |

| LXXVII. | Dwellings—Canoes | 784 |

| NEW ZEALAND. | ||

| LXXVIII. | General Remarks | 792 |

| LXXIX. | Dress | 800 |

| LXXX. | Dress—Concluded | 807 |

| LXXXI. | Domestic Life | 816 |

| LXXXII. | Food and Cookery | 826 |

| LXXXIII. | War | 838 |

| LXXXIV. | Canoes | 852 |

| LXXXV. | Religion | 856 |

| LXXXVI. | The Tapu | 863 |

| LXXXVII. | Funeral Ceremonies—Architecture | 869 |

| NEW CALEDONIA. | ||

| LXXXVIII. | Appearance—Dress—Warfare | 883 |

| ANDAMAN AND NICOBAR ISLANDS. | ||

| LXXXIX. | Origin of Natives—Appearance—Character—Education | 888 |

| NEW GUINEA. | ||

| XC. | Papuans and Outanatas | 898 |

| XCI. | The Alfoërs or Haraforas | 905 |

| PHILIPPINE ISLANDS. | ||

| XCII. | The Ajitas or Ahitas | 919 |

| FIJI. | ||

| XCIII. | Appearance—Dress | 922 |

| XCIV. | Manufactures | 929 |

| XCV. | Government—Social Life | 934 |

| XCVI. | War—Amusements | 948 |

| XCVII. | Religion—Funeral Rites | 960 |

| SOLOMON ISLANDS AND NEW HEBRIDES. | ||

| XCVIII. | Character—Dress—Customs | 968 |

| TONGA. | ||

| XCIX. | Government—Gradations of Rank | 976 |

| C. | War and Ceremonies | 984 |

| CI. | Sickness—Burial—Games | 997 |

| SAMOA, OR NAVIGATOR’S ISLAND. | ||

| CII. | Appearance—Character—Dress | 1008 |

| CIII. | War | 1016 |

| CIV. | Amusements—Marriage—Architecture | 1028 |

| HERVEY AND KINGSMILL ISLANDS. | ||

| CV. | Appearance—Weapons—Government | 1032 |

| MARQUESAS ISLANDS. | ||

| CVI. | Dress—Amusements—War—Burial | 1044 |

| NIUE, OR SAVAGE ISLANDS. | ||

| CVII. | Origin—Costume—Laws—Burial | 1052 |

| SOCIETY ISLANDS. | ||

| CVIII. | Appearance—Dress—Social Customs | 1057 |

| CIX. | Religion | 1064 |

| CX. | History—War—Funerals—Legends | 1072 |

| SANDWICH ISLANDS. | ||

| CXI. | Climate—Dress—Ornaments—Women | 1081 |

| CXII. | War—Sport—Religion | 1088 |

| CAROLINE ARCHIPELAGO. | ||

| CXIII. | Dress—Architecture—Amusements—War | 1100 |

| BORNEO. | ||

| CXIV. | The Dyaks, Appearance and Dress | 1110 |

| CXV. | War | 1119 |

| CXVI. | War—Concluded | 1128 |

| CXVII. | Social Life | 1137 |

| CXVIII. | Architecture, Manufactures | 1149 |

| CXIX. | Religion—Omens—Funerals | 1157 |

| TIERRA DEL FUEGO. | ||

| CXX. | Appearance—Architecture—Manufactures | 1161 |

| PATAGONIANS. | ||

| CXXI. | Appearance—Weapons—Horsemanship | 1172 |

| CXXII. | Domestic Life | 1183 |

| ARAUCANIANS. | ||

| CXXIII. | Dress—Etiquette—Government | 1190 |

| CXXIV. | Domestic Life | 1196 |

| CXXV. | Games—Social Customs | 1204 |

| THE GRAN CHACO. | ||

| CXXVI. | Appearance—Weapons—Character | 1211 |

| THE MUNDURUCÚS. | ||

| CXXVII. | Manufactures—Social Customs | 1215 |

| THE TRIBES OF GUIANA. | ||

| CXXVIII. | Weapons | 1221 |

| CXXIX. | Weapons—Concluded | 1228 |

| CXXX. | War—Superstition | 1239 |

| CXXXI. | Architecture—Social Customs | 1245 |

| CXXXII. | Dress—Amusements | 1255 |

| CXXXIII. | Religion—Burial | 1263 |

| MEXICO. | ||

| CXXXIV. | History—Religion—Art | 1271 |

| NORTH AMERICAN INDIANS. | ||

| CXXXV. | Government—Customs | 1273 |

| CXXXVI. | War | 1281 |

| CXXXVII. | Hunting—Amusements | 1293 |

| CXXXVIII. | Religion—Superstition | 1301 |

| CXXXIX. | Social Life | 1316 |

| ESQUIMAUX. | ||

| CXL. | Appearance—Dress—Manners | 1333 |

| CXLI. | Hunting—Religion—Burial | 1338 |

| VANCOUVER’S ISLAND. | ||

| CXLII. | The Ahts, and Neighboring Tribes | 1354 |

| CXLIII. | Canoes—Feasts—Dances | 1362 |

| CXLIV. | Architecture—Religion—Disposal of Dead | 1369 |

| ALASKA. | ||

| CXLV. | Malemutes—Ingeletes—Co-yukons | 1374 |

| SIBERIA. | ||

| CXLVI. | The Tchuktchi—Jakuts—Tungusi | 1377 |

| CXLVII. | The Samoïedes—Ostiaks | 1381 |

| INDIA. | ||

| CXLVIII. | The Sowrahs and Khonds | 1385 |

| CXLIX. | Weapons | 1395 |

| CL. | Sacrificial Religion | 1407 |

| CLI. | The Indians, with relation to Animals | 1416 |

| TARTARY. | ||

| CLII. | The Mantchu Tartars | 1422 |

| CHINA. | ||

| CLIII. | Appearance—Dress—Food | 1426 |

| CLIV. | Warfare | 1433 |

| CLV. | Social Characteristics | 1441 |

| JAPAN. | ||

| CLVI. | Dress—Art—Amusements | 1449 |

| CLVII. | Miscellaneous Customs | 1458 |

| SIAM. | ||

| CLVIII. | Government—Dress—Religion | 1467 |

| ANCIENT EUROPE. | ||

| CLIX. | The Swiss Lake-Dwellers | 1473 |

| CENTRAL AFRICA. | ||

| CLX. | The Makondé | 1475 |

| CLXI. | The Waiyau | 1478 |

| CLXII. | The Babisa and Babemba | 1482 |

| CLXIII. | The Manyuema | 1487 |

| CLXIV. | The Manyuema—Concluded | 1492 |

| CLXV. | Unyamwezi | 1496 |

| CLXVI. | Uvinza and Uhha | 1500 |

| CLXVII. | The Monbuttoo | 1503 |

| CLXVIII. | The Pygmies | 1508 |

| CLXIX. | General Characteristics of African Tribes | 1511 |

| CLXX. | The African Slave Trade | 1515 |

| CENTRAL ASIA. | ||

| CLXXI. | The Kakhyens | 1520 |

[11]

THE KAFFIR, OR ZINGIAN TRIBES, AND THEIR PHYSICAL PECULIARITIES — ORIGIN OF THE NAME — THEORIES AS TO THEIR PRESENCE IN SOUTHERN AFRICA — THE CHIEF TRIBES AND THEIR LOCALITIES — THE ZULUS AND THEIR APPEARANCE — THEIR COMPLEXION AND IDEAS OF BEAUTY — POINTS OF SIMILITUDE AND CONTRAST BETWEEN THE KAFFIR AND THE NEGRO — MENTAL CHARACTERISTICS OF THE KAFFIR — HIS WANT OF CARE FOR THE FUTURE, AND REASONS FOR IT — CONTROVERSIAL POWERS OF THE KAFFIR — THE SOCRATIC MODE OF ARGUMENT — THE HORNS OF A DILEMMA — LOVE OF A KAFFIR FOR ARGUMENT — HIS MENTAL TRAINING AND ITS CONSEQUENCES — PARTHIAN MODE OF ARGUING — PLACABLE NATURE OF THE KAFFIR — HIS SENSE OF SELF-RESPECT — FONDNESS FOR A PRACTICAL JOKE — THE WOMAN AND THE MELON — HOSPITALITY OF THE KAFFIRS — THEIR DOMESTICATED NATURE AND FONDNESS FOR CHILDREN — THEIR HATRED OF SOLITUDE.

Over the whole of the Southern portion of the great Continent of Africa is spread a remarkable and interesting race of mankind. Though divided into numerous tribes, and differing in appearance, manners, and customs, they are evidently cast in the same mould, and belong to the same group of the human race. They are dark, but not so black as the true negro of the West. Their hair is crisp, short, and curled, but not so woolly as that of the negro; their lips, though large when compared with those of Europeans, are small when compared to those of the negro. The form is finely modelled, the stature tall, the limbs straight, the forehead high, the expression intelligent; and, altogether, this group of mankind affords as fine examples of the human form as can be found anywhere on the earth.

To give a name to this large group is not very easy. Popularly, the tribes which compose it are known as Kaffirs; but that term has now been restricted to the tribes on the south-east of the continent, between the sea and the range of the Draakensberg Mountains. Moreover, the name Kaffir is a very inappropriate one, being simply the term which the Moslem races apply to all who do not believe with themselves, and by which they designate black and white men alike. Some ethnologists have designated them by the general name of Chuanas, the word being the root of the well-known Bechuana, Sechuana, and similar names; while others have preferred the word Bantu, and others Zingian, which last word is perhaps the best.

Whatever may be the title, it is evident that they are not aborigines, but that they have descended upon Southern Africa from some other locality—probably from more northern parts of the same continent. Some writers claim for the Kaffir or Zingian tribes an Asiatic origin, and have a theory that in the course of their migration they mixed with the negroes, and so became possessed of the frizzled hair, the thick lips, the dark skin, and other peculiarities of the negro race.

Who might have been the true aborigines of Southern Africa cannot be definitely stated, inasmuch as even within very recent times great changes have taken place. At the present time South Africa is practically European, the white man, whether Dutch or English, having dispossessed the owners of the soil, and either settled upon the land or reduced the dark-skinned inhabitants to the rank of mere dependants. Those whom they displaced were themselves interlopers, having overcome and ejected the Hottentot tribes, who in their turn seem but to have suffered the same fate which in the time of their greatness they had brought upon others.

At the present day the great Zingian group affords the best type of the inhabitants of Southern Africa, and we will therefore begin with the Kaffir tribes.

If the reader will refer to a map of Africa, he will see that upon the south-east coast a long range of mountains runs nearly parallel with the sea-line, and extends from lat.[12] 27° to 33°. It is the line of the Draakensberg Mountains, and along the strip of land which intervenes between these mountains and the sea are found the genuine Kaffir tribes. There are other tribes belonging to the same group of mankind which are found on the western side of the Draakensberg, and are spread over the entire country, from Delagoa Bay on the east to the Orange River on the west. These tribes are familiar to readers of African travel under the names of Bechuanas, Bayeye, Namaqua, Ovampo, &c. But, by common consent, the name of Kaffir is now restricted to those tribes which inhabit the strip of country above mentioned.

Formerly, a considerable number of tribes inhabited this district, and were sufficiently distinct to be almost reckoned as different nations. Now, however, these tribes are practically reduced to five; namely, the Amatonga on the north, followed southward by the Amaswazi, the Amazulu, the Amaponda, and the Amakosa. Here it must be remarked that the prefix of “Ama,” attached to all the words, is one of the forms by which the plural of certain names is designated. Thus, we might speak of a single Tonga, Swazi, Zulu, or Ponda Kaffir; but if we wish to speak of more than one, we form the plural by prefixing “Ama” to the word.

The other tribes, although they for the most part still exist and retain the ancient names, are practically merged into those whose names have been mentioned.

Of all the true Kaffir tribes, the Zulu is the chief type, and that tribe will be first described. Although spread over a considerable range of country, the Zulu tribe has its headquarters rather to the north of Natal, and there may be found the best specimens of this splendid race of men. Belonging, as do the Zulu tribes, to the dark-skinned portion of mankind, their skin does not possess that dead, jetty black which is characteristic of the Western negro. It is a more transparent skin, the layer of coloring matter does not seem to be so thick, and the ruddy hue of the blood is perceptible through the black. It is held by the Kaffirs to be the perfection of human coloring; and a Zulu, if asked what he considers to be the finest complexion, will say that it is, like his own, black, with a little red.

Some dark-skinned nations approve of a fair complexion, and in some parts of the world the chiefs are so much fairer than the commonalty, that they seem almost to belong to different races. The Kaffir, however, holds precisely the opposite opinion. According to his views of human beauty, the blacker a man is the handsomer he is considered, provided that some tinge of red be perceptible. They carry this notion so far, that in sounding the praises of their king, an act at which they are very expert, they mention, as one of his excellences, that he chooses to be black, though, being so powerful a monarch, he might have been white if he had liked. Europeans who have resided for any length of time among the Kaffir tribes seem to imbibe similar ideas about the superior beauty of the black and red complexion. They become used to it, and perceive little varieties in individuals, though to an inexperienced eye the color would appear exactly similar in every person. When they return to civilized society they feel a great contempt for the pale, lifeless-looking complexion of Europeans, and some time elapses before they learn to view a fair skin and light hair with any degree of admiration. Examples of albinos are occasionally seen among the Kaffirs, but they are not pleasant-looking individuals, and are not admired by their blacker and more fortunate fellow-countrymen. A dark olive is, however, tolerably common, but the real hue of the skin is that of rather blackish chocolate. As is the case with the negro race, the newly born infant of a Kaffir is nearly as pale as that of a European, the dark hue becoming developed by degrees.

Though dark of hue, the Kaffirs are as fastidious about their dusky complexion as any European belle could be of her own fairer skin; and the pride with which a Kaffir, even though he be a man and a tried warrior, regards the shining, transparent black of his skin, has in it something ludicrous to an inhabitant of Europe.

The hair of the Kaffir, whether it belong to male or female, never becomes long, but envelopes the head in a close covering of crisp, woolly curls, very similar to the hair of the true negro. The lips are always large, the mouth wide, and the nose has very wide nostrils. These peculiarities the Kaffir has in common with the negro, and it now and then happens that an individual has these three features so strongly marked that he might be mistaken for a negro at first sight. A more careful view, however, would at once detect the lofty and intellectual forehead, the prominence of the nose, and the high cheek-bones, together with a nameless but decided cast of countenance, which marks them out from all other groups of the dark-skinned natives of Africa. The high cheek-bones form a very prominent feature in the countenances of the Hottentots and Bosjesmans, but the Kaffir cannot for a moment be mistaken for either one or the other, any more than a lion could be mistaken for a puma.

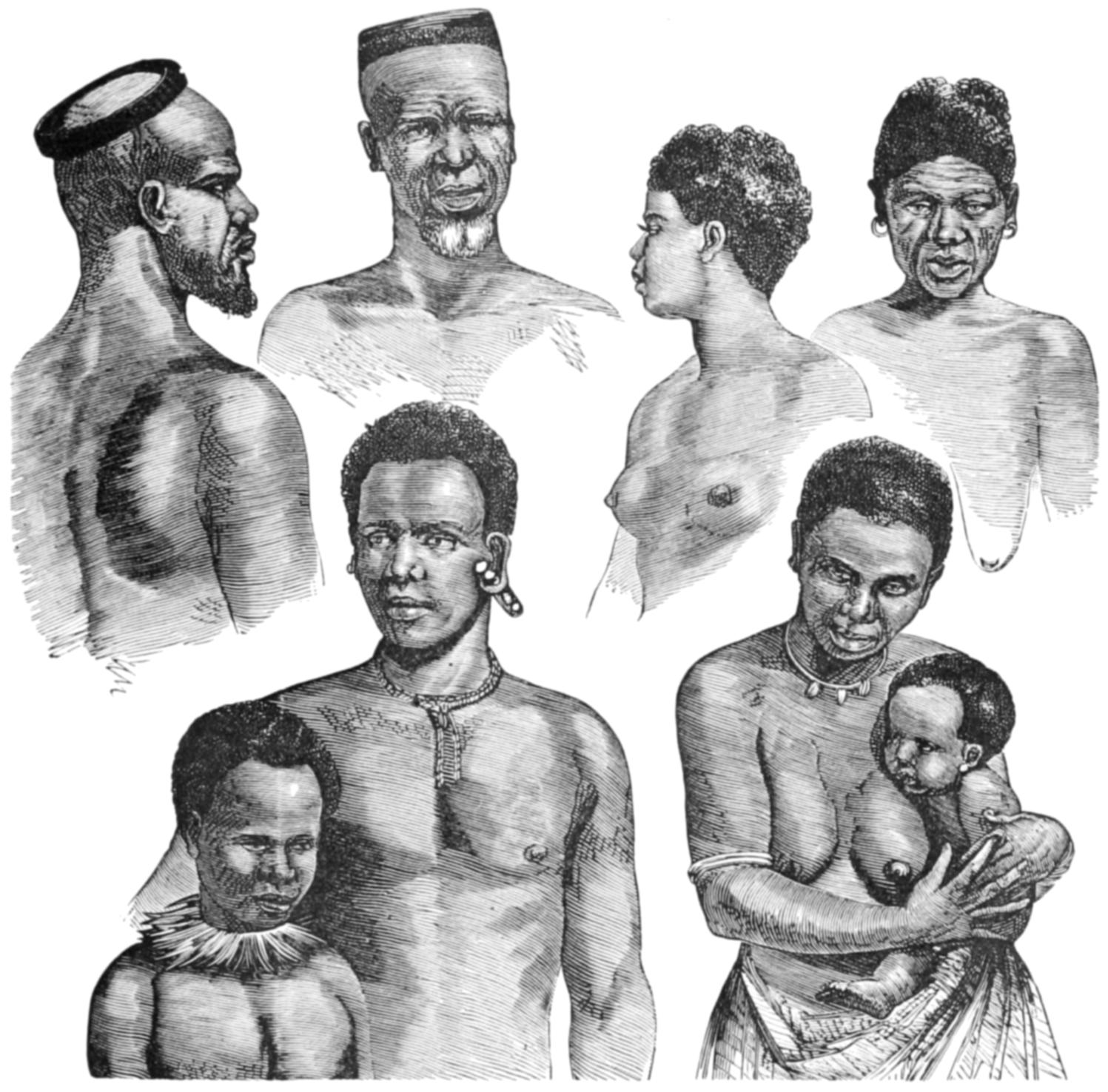

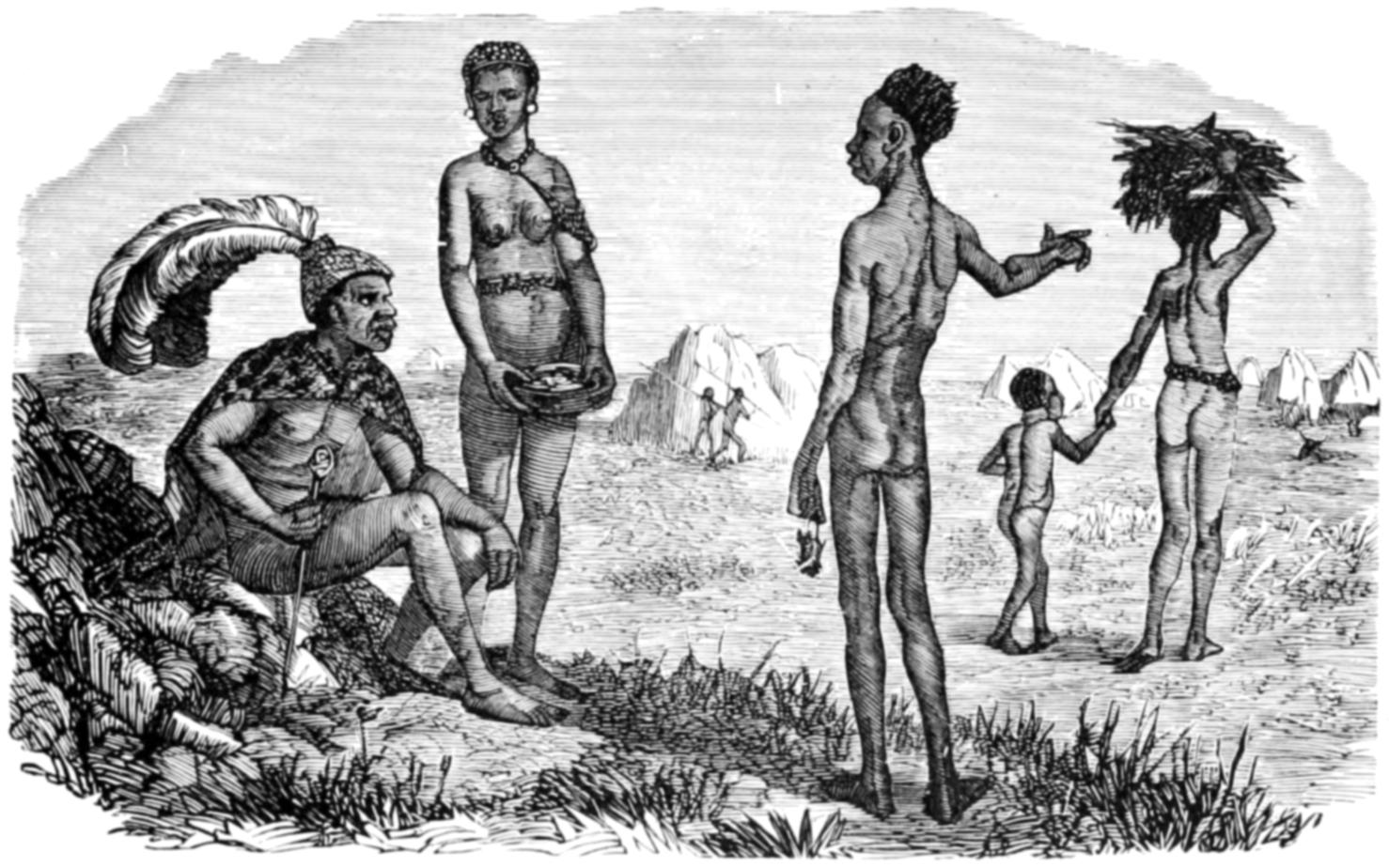

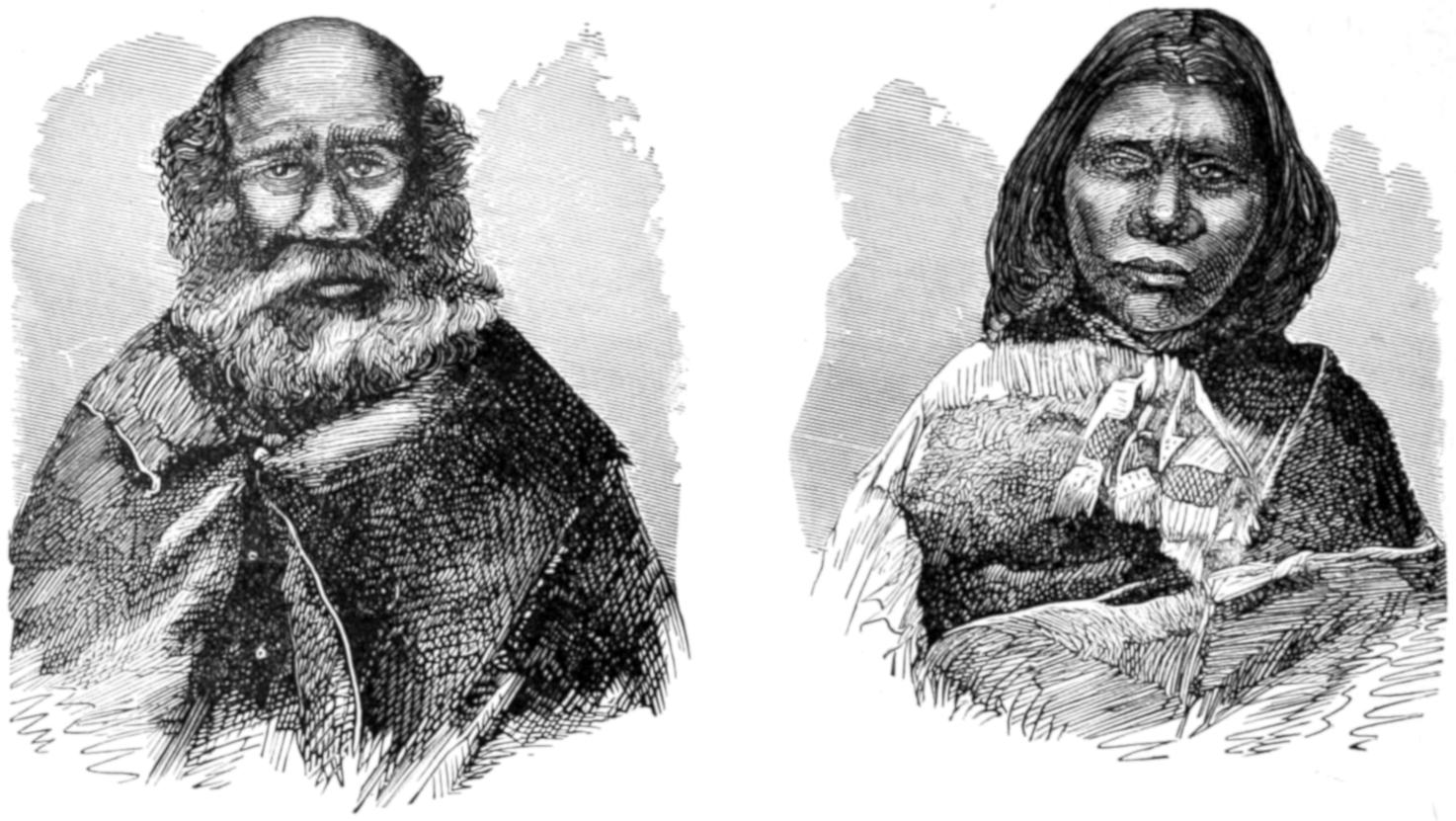

OLD COUNCILLOR AND WIVES.

(See page 16.)

THE KAFFIR FROM CHILDHOOD TO AGE. From Photographic Portraits.

Married Man.

Old Councillor.

Unmarried Girl.

Old Woman.

Young Boy.

Unmarried Man or “Boy.”

Young Married Woman and Child.

(See page 12.)

[15]

The expression of the Kaffir face, especially when young, is rather pleasing; and, as a general rule, is notable when in repose for a slight plaintiveness, this expression being marked most strongly in the young, of both sexes. The dark eyes are lively and full of intellect, and a kind of cheerful good humor pervades the features. As a people, they are devoid of care. The three great causes of care in more civilized lands have but little influence on a Kaffir. The clothes which he absolutely needs are of the most trifling description, and in our sense of the word cannot be recognized as clothing at all. The slight hut which enacts the part of a house is constructed of materials that can be bought for about a shilling, and to the native cost nothing but the labor of cutting and carrying. His food, which constitutes his only real anxiety, is obtained far more easily than among civilized nations, for game-preserving is unknown in Southern Africa, and any bird or beast becomes the property of any one who chooses to take the trouble of capturing it. One of the missionary clergy was much struck by this utter want of care, when he was explaining the Scriptures to some dusky hearers. The advice “to take no thought for the morrow” had not the least effect on them. They never had taken any thought for the morrow, and never would do so, and rather wondered that any one could have been foolish enough to give them such needless advice.

There is another cause for this heedless enjoyment of the present moment; namely, an instinctive fatalism, arising from the peculiar nature of their government. The power of life and death with which the Kaffir rulers are invested is exercised in so arbitrary and reckless a manner, that no Kaffir feels the least security for his life. He knows perfectly well that the king may require his life at any moment, and he therefore never troubles himself about a future which may have no existence for him.

Of course these traits of character belong only to the Kaffir in their normal condition; for, when these splendid savages have placed themselves under the protection of Europeans, the newly-felt security of life produces its natural results, and they will display forethought which would do no discredit to a white man. A lad, for example, will give faithful service for a year, in order to obtain a cow at the end of that time. Had he been engaged while under the rule of his own king, he would have insisted on prepayment, and would have honorably fulfilled his task provided that the king did not have him executed. Their fatalism is, in fact, owing to the peculiarly logical turn of a Kaffir’s mind, and his determination to follow an argument to its conclusion. He accepts the acknowledged fact that his life is at the mercy of the king’s caprice, and draws therefrom the inevitable conclusion that he can calculate on nothing beyond the present moment.

The lofty and thoughtful forehead of the Kaffir does not belie his character, for, of all savage races, the Kaffir is perhaps the most intellectual. In acts he is honorable and straightforward, and, with one whom he can trust, his words will agree with his actions. But he delights in controversy, and has a special faculty for the Socratic mode of argument; namely, by asking a series of apparently unimportant questions, gradually hemming in his adversary, and forcing him to pronounce his own sentence of condemnation. If he suspects another of having committed a crime, and examines the supposed culprit before a council, he will not accuse him directly of the crime, but will cross-examine him with a skill worthy of any European lawyer, each question being only capable of being answered in one manner, and so eliciting successive admissions, each of which forms a step in the argument.

An amusing example of this style of argument is given by Fleming. Some Kaffirs had been detected in eating an ox, and the owner brought them before a council, demanding payment for the ox. Their defence was that they had not killed the animal, but had found it dying from a wound inflicted by another ox, and so had considered it as fair spoil. When their defence had been completed, an old Kaffir began to examine the previous speaker, and, as usual, commenced by a question apparently wide of the subject.

Q. “Does an ox tail grow up, down, or sideways?”

A. “Downward.”

Q. “Do its horns grow up, down, or sideways?”

A. “Up.”

Q. “If an ox gores another, does he not lower his head and gore upward?”

A. “Yes.”

Q. “Could he gore downward?”

A. “No.”

The wily interrogator then forced the unwilling witness to examine the wound which he asserted to have been made by the horn of another ox, and to admit that the slain beast had been stabbed and not gored.

Mr. Grout, the missionary, mentions an instance of the subtle turn of mind which distinguishes an intelligent Kaffir. One of the converts came to ask what he was to do if he went on a journey with his people. It must first be understood that a Kaffir takes no provisions when travelling, knowing that he will receive hospitality on the way.

“What shall I do, when I am out on a journey among the people, and they offer such food as they have, perhaps the flesh of an animal which has been slaughtered in honor of the ghosts of the departed? If I eat it, they will say, ‘See there! he is a believer in our religion—he partakes with us of the meat offered to our gods.’ And if I do not eat, they will say, ‘See there! he is a believer in the existence and power of our gods, else why does he hesitate to eat of the meat which we have slaughtered to them?’”

[16]

Argument is a Kaffir’s native element, and he likes nothing better than a complicated debate where there is plenty of hair-splitting on both sides. The above instances show that a Kaffir can appreciate a dilemma as well as the most accomplished logicians, and he is master of that great key of controversy,—namely, throwing the burden of proof on the opponent. In all his controversy he is scrupulously polite, never interrupting an opponent, and patiently awaiting his own turn to speak. And when the case has been fully argued, and a conclusion arrived at, he always bows to the decision of the presiding chief, and acquiesces in the judgment, even when a penalty is inflicted upon himself.

Trained in such a school, the old and influential chief, who has owed his position as much to his intellect as to his military repute, becomes a most formidable antagonist in argument, especially when the question regards the possession of land and the boundaries to be observed. He fully recognizes the celebrated axiom that language was given for the purpose of concealing the thoughts, and has recourse to every evasive subterfuge and sophism that his subtle brain can invent. He will mix truth and falsehood with such ingenuity that it is hardly possible to separate them. He will quietly “beg the question,” and then proceed as composedly as if his argument were a perfectly fair one. He will attack or defend, as best suits his own case, and often, when he seems to be yielding point after point, he makes a sudden onslaught, becomes in his turn the assailant, and marches to victory over the ruins of his opponent’s arguments.

On page 13 the reader will find a portrait of one of the councillors attached to Goza, the well-known Kaffir chief, of whom we shall learn more presently. And see what a face the man has—how his broad forehead is wrinkled with thought, and how craftily his black eyes gleam from under their deep brows. Half-naked savage though he be, the man who will enter into controversy with him will find no mean antagonist, and, whether the object be religion or politics, he must beware lest he find himself suddenly defeated exactly when he felt most sure of victory. The Maori of New Zealand is no mean adept at argument, and in many points bears a strong resemblance to the Kaffir character. But, in a contest of wits between a Maori chief and a Zulu councillor, the latter would be nearly certain to come off the victor.

As a rule, the Kaffir is not of a revengeful character, nor is he troubled with that exceeding techiness which characterizes some races of mankind. Not that he is without a sense of dignity. On the contrary, a Kaffir can be among the most dignified of mankind when he wishes, and when there is some object in being so. But he is so sure of himself that, like a true gentleman, he never troubles himself about asserting his dignity. He is so sure that no real breach of respect can be wilfully committed, that a Kaffir will seldom hesitate to play a practical joke upon another—a proceeding which would be the cause of instant bloodshed among the Malays. And, provided that the joke be a clever one, no one seems to enjoy it more than the victim.

One resident in Kaffirland mentions several instances of the tendency of the Kaffirs toward practical joking. A lad in his service gravely told his fellow-countrymen that all those who came to call on the Englishmen were bound by etiquette to kneel down and kiss the ground at a certain distance from the house. The natives, born and bred in a system of etiquette equal to that of any court in Europe, unhesitatingly obeyed, while the lad stood by, superintending the operation, and greatly enjoying the joke. After a while, the trick was discovered, and no one appreciated the boy’s wit more than those who had fallen into the snare.

Another anecdote, related by the same author, seems as if it had been transplanted from a First of April scene in England. A woman was bringing home a pumpkin, and, according to the usual mode of carrying burdens in Africa, was balancing it on her head. A mischievous boy ran hastily to her, and, with a face of horror, exclaimed, “There’s something on your head!” The woman, startled at the sudden announcement, thought that at least a snake had got on her head, and ran away screaming. Down fell the pumpkin, and the boy picked it up, and ate it before the woman recovered from her fright.

The Kaffir is essentially hospitable. On a journey, any one may go to the kraal of a stranger, and will certainly be fed and lodged, both according to his rank and position. White men are received in the same hospitable manner, and, in virtue of their white skin and their presumed knowledge, they are always ranked as chiefs, and treated according.

The Kaffirs are singularly domestic people, and, semi-nomad as they are, cling with great affection to their simple huts. Chiefs and warriors of known repute may be seen in their kraals, nursing and fondling their children with no less affection than is exhibited by the mothers. Altogether, the Kaffir is a social being. He cannot endure living alone, eating alone, smoking alone, snuffing alone, or even cooking alone, but always contrives to form part of some assemblage devoted to the special purpose. Day by day, the men assemble and converse with each other, often treating of political affairs, and training themselves in that school of forensic argument which has already been mentioned.

[17]

COURSE OF A KAFFIR’S LIFE — INFANCY — COLOR OF THE NEW-BORN BABE — THE MEDICINE-MAN AND HIS DUTIES — KAFFIR VACCINATION — SINGULAR TREATMENT OF A CHILD — A CHILD’S FIRST ORNAMENT — CURIOUS SUPERSTITION — MOTHER AND CHILD — THE SKIN-CRADLE — DESCRIPTION OF A CRADLE BELONGING TO A CHIEF’S WIFE — KINDNESS OF PARENTS TO CHILDREN OF BOTH SEXES — THE FUTURE OF A KAFFIR FAMILY, AND THE ABSENCE OF ANXIETY — INFANTICIDE ALMOST UNKNOWN — CEREMONY ON PASSING INTO BOYHOOD — DIFFERENT THEORIES RESPECTING ITS CHARACTER AND ORIGIN — TCHAKA’S ATTEMPTED ABOLITION OF THE RITE — CURIOUS IDEA OF THE KAFFIRS, AND RESUMPTION OF THE CEREMONY — A KAFFIR’S DREAD OF GRAY HAIRS — IMMUNITIES AFTER UNDERGOING THE RITE — NEW RECRUITS FOR REGIMENTS, AND THEIR VALUE TO THE KING — THE CEREMONY INCUMBENT ON BOTH SEXES.

Having glanced rapidly over the principal traits of Kaffir character, we will proceed to trace his life with somewhat more detail.

When an infant is born, it is, as has been already mentioned, of a light hue, and does not gain the red-black of its parents until after some little time has elapsed. The same phenomenon takes place with the negro of Western Africa. Almost as soon as the Kaffir is born the “medicine-man” is called, and discharges his functions in a manner very different from “medical men” in our own country. He does not trouble himself in the least about the mother, but devotes his whole care to the child, on whom he performs an operation something like that of vaccination, though not for the same object. He makes small incisions on various parts of the body, rubs medicine into them, and goes his way. Next day he returns, takes the unhappy infant, deepens the cuts, and puts more medicine into them. The much-suffering child is then washed, and is dried by being moved about in the smoke of a wood fire. Surviving this treatment by some singular tenacity of life, the little creature is then plentifully bedaubed with red paint, and the proud mother takes her share of the adornment. This paint is renewed as fast as it wears off, and is not discontinued until after a lapse of several months.

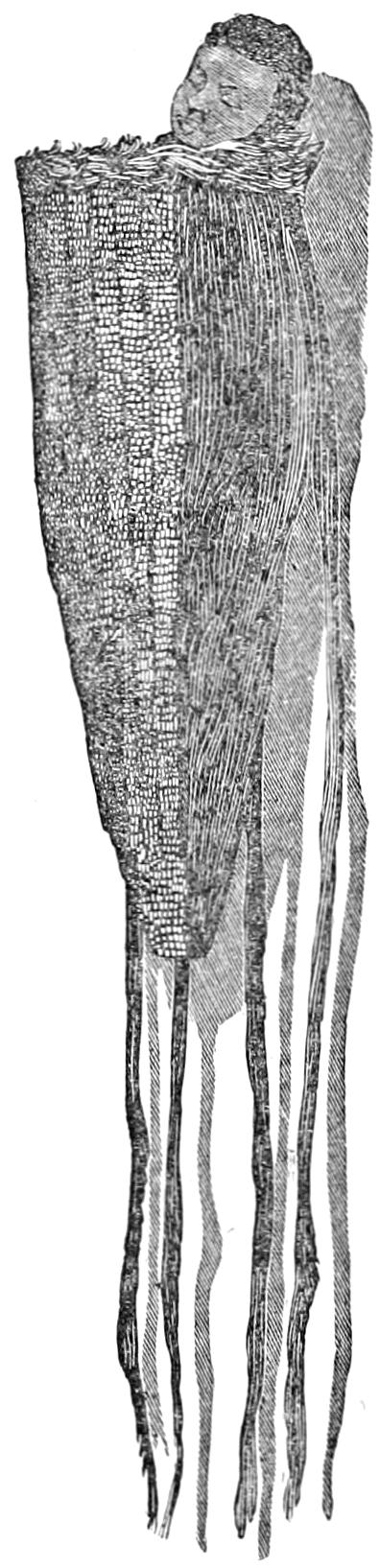

CRADLE.

“Once,” writes Mr. Shooter, “when I saw this paint put on, the mother had carefully washed a chubby boy, and made him clean and bright. She then took up the fragment of an earthenware pot, which contained a red fluid, and, dipping her fingers into it, proceeded to daub her son until he became the most grotesque-looking object it was ever my fortune to behold. What remained, being too precious to waste, was transferred to her own face.” Not until all these absurd preliminaries are completed, is the child allowed to take its natural food; and it sometimes happens that when the “medicine-man” has delayed his coming, the consequences to the poor little creature have been extremely disastrous. After the lapse of a few days, the mother goes about her work as usual, carrying the child strapped on her back, and, in spite of the load, she makes little, if any, difference in the amount of her daily tasks. And, considering that all the severe work falls upon the women, it is wonderful that they should contrive to do any work at all under the circumstances. The two principal tasks of the women are, breaking up the ground with a heavy and clumsy tool, something between a pickaxe and a mattock, and grinding the daily supply of corn between two stones, and either of these tasks would prove quite enough for any ordinary laborer, though the poor woman has to perform both, and plenty of minor tasks besides. That they should have to do all this work, while laboring under the incumbrance of a heavy and growing child hung on the back, does really seem very hard upon the women. But they, having never known any other state of things, accept their laborious married life as a matter of course.

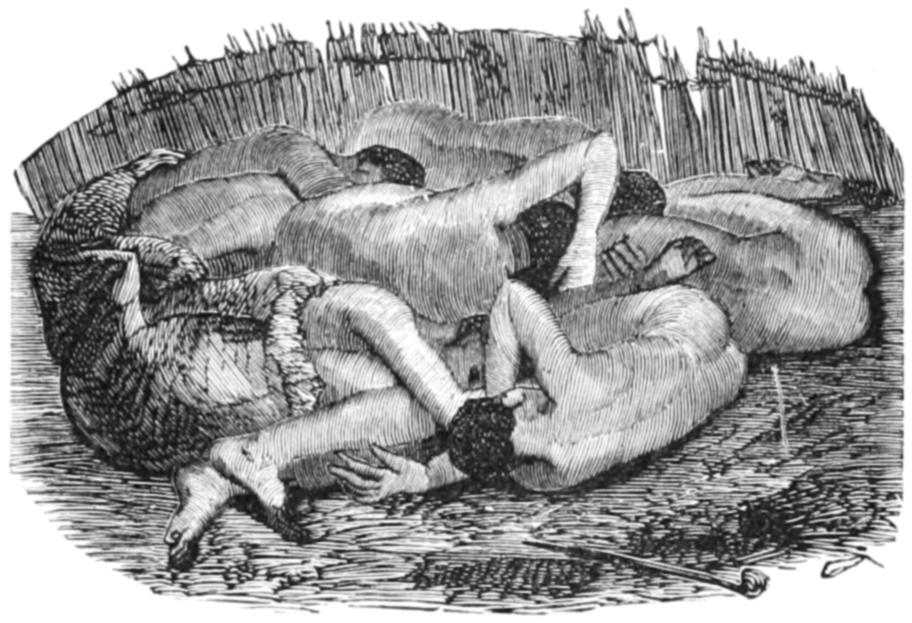

When the mother carries her infant to the field, she mostly slings it to her back by means of a wide strip of some soft skin, which she passes round her waist so as to[18] leave a sort of pocket behind in which the child may lie. In this primitive cradle the little creature reposes in perfect content, and not even the abrupt movements to which it is necessarily subjected will disturb its slumbers.

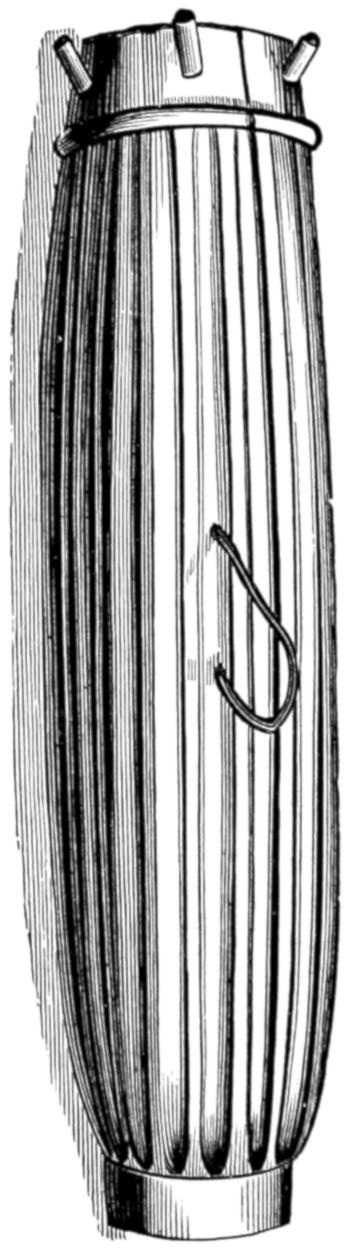

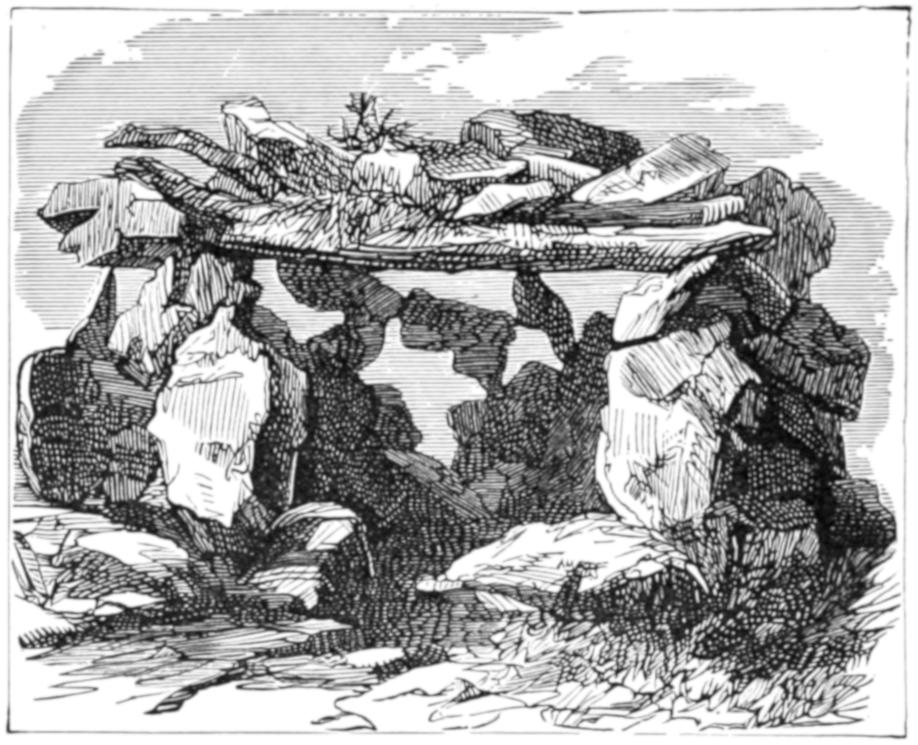

The wife of a chief or wealthy man will not, however, rest satisfied with the mere strip of skin by way of a cradle, but has one of an elaborate and ornamental character. The illustration represents a remarkably fine example of the South African cradle, and is drawn from a specimen in my collection.

It is nearly two feet in length by one in width, and is made of antelope skin, with the hair still remaining. The first care of the maker has been to construct a bag, narrow toward the bottom, gradually widening until within a few inches of the opening, when it again contracts. This form very effectually prevents an active or restless child from falling out of its cradle. The hairy side of the skin is turned inward, so that the little one has a soft and pleasant cradle in which to repose. In order to give it this shape, two “gores” have been let into the back of the cradle, and are sewed with that marvellous neatness which characterizes the workmanship of the Kaffir tribes. Four long strips of the same skin are attached to the opening of the cradle, and by means of them the mother can bind her little one securely on her back.

As far as usefulness goes, the cradle is now complete, but the woman is not satisfied unless ornament be added. Though her rank—the wife of a chief—does not exonerate her from labor, she can still have the satisfaction of showing her position by her dress, and exciting envy among her less fortunate companions in the field. The entire front of the cradle is covered with beads, arranged in regular rows. In this specimen, two colors only are used; namely, black and white. The black beads are polished glass, while the others are of the color which are known as “chalk-white,” and which is in great favor with the Kaffirs, on account of the contrast which it affords to their dusky skin. The two central rows are black. The cradle weighs rather more than two pounds, half of which is certainly due to the profusion of beads with which it is covered.

Except under peculiar circumstances, the Kaffir mother is a kind, and even indulgent parent to her children. There are, however, exceptional instances, but, in these cases, superstition is generally the moving power. As with many nations in different parts of the earth, although abundance of children is desired, twins are not in favor; and when they make their appearance one of them is sacrificed, in consequence of a superstitious notion that, if both twins are allowed to live, something unlucky would happen to the parents.

As the children grow, a certain difference in their treatment is perceptible. In most savage nations, the female children are comparatively neglected, and very ill treatment falls on them, while the males are considered as privileged to do pretty well what they like without rebuke. This, however, is not the case with the Kaffirs. The parents have plenty of respect for their sons as the warriors of the next generation, but they have also respect for their daughters as a source of wealth. Every father is therefore glad to see a new-born child, and welcomes it whatever may be its sex—the boys to increase the power of his house, the girls to increase the number of his cattle. He knows perfectly well that, when his little girl is grown up, he can obtain at least[19] eight cows for her, and that, if she happens to take the fancy of a rich or powerful man, he may be fortunate enough to procure twice the number. And, as the price which is paid to the father of a girl depends very much on her looks and condition, she is not allowed to be deteriorated by hard work or ill-treatment. These generally come after marriage, and, as the wife does not expect anything but such treatment, she does not dream of complaining.

The Kaffir is free from the chief anxieties that attend a large family in civilized countries. He knows nothing of the thousand artificial wants which cluster round a civilized life, and need not fear lest his offspring should not be able to find a subsistence. Neither is he troubled lest they should sink below that rank in which they were born. Not that there are no distinctions of rank in Kaffirland. On the contrary, there are few parts of the world where the distinctions of rank are better appreciated, or more clearly defined. But, any one may attain the rank of chief, provided that he possesses the mental or physical characteristics that can raise him above the level of those who surround him, and, as is well known, some of the most powerful monarchs who have exercised despotic sway in Southern Africa have earned a rank which they could not have inherited, and have created monarchies where the country had formerly been ruled by a number of independent chieftains. These points may have some influence upon the Kaffir’s conduct as a parent, but, whatever may be the motives, the fact remains, that among this fine race of savages there is no trace of the wholesale infanticide which is so terribly prevalent among other nations, and which is accepted as a social institution among some that consider themselves among the most highly civilized of mankind.

As is the case in many parts of the world, the natives of South Africa undergo a ceremony of some sort, which marks their transition from childhood to a more mature age. There has been rather a sharp controversy respecting the peculiar ceremony which the Kaffirs enjoin, some saying that it is identical with the rite of circumcision as practised by the Jews, and others that such a custom does not exist. The fact is, that it used to be universal throughout Southern Africa, until that strange despot, Tchaka, chose arbitrarily to forbid it among the many tribes over which he ruled. Since his death, however, the custom has been gradually re-introduced, as the men of the tribes believed that those who had not undergone the rite were weaker than would otherwise have been the case, and were more liable to gray hairs. Now with a Kaffir a hoary head is by no means a crown of glory, but is looked upon as a sign of debility. A chief dreads nothing so much as the approach of gray hairs, knowing that the various sub-chiefs, and other ambitious men who are rising about him, are only too ready to detect any sign of weakness, and to eject him from his post. Europeans who visit elderly chiefs are almost invariably asked if they have any preparation that will dye their gray hairs black. So, the dread of such a calamity occurring at an early age would be quite sufficient to make a Kaffir resort to any custom which he fancied might prevent it.

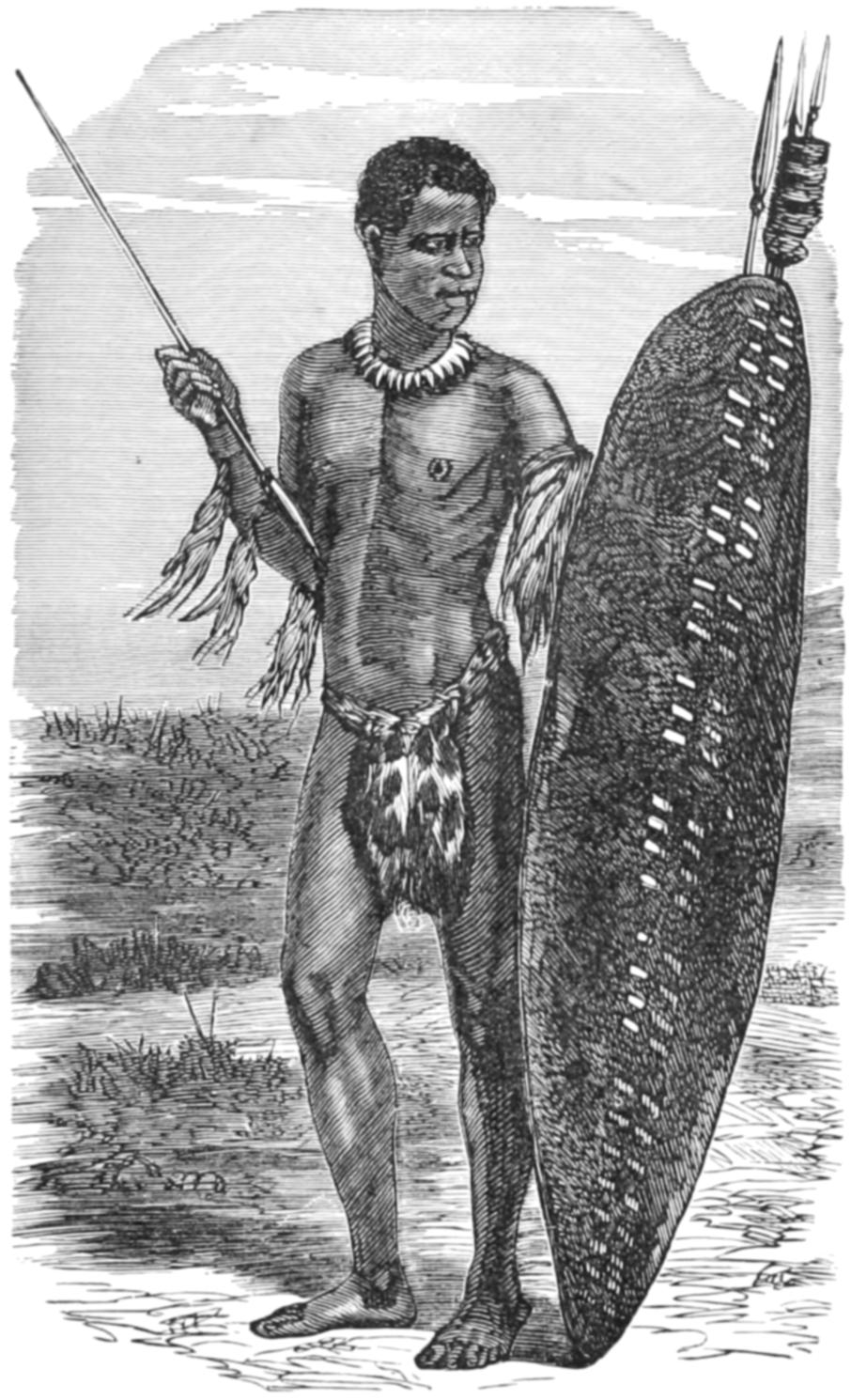

After the ceremony, which is practised in secret, and its details concealed with inviolable fidelity, the youths are permitted three months of unlimited indulgence: doing no work, and eating, sleeping, singing, and dancing, just as they like. They are then permitted to bear arms, and, although still called “boys,” are trained as soldiers and drafted into different regiments. Indeed, it is mostly from these regiments that the chief selects the warriors whom he sends on the most daring expeditions. They have nothing to lose and everything to gain, and, if they distinguish themselves, may be allowed to assume the “head-ring,” the proud badge of manhood, and to marry as many wives as they can manage to pay for. A “boy”—no matter what his age might be—would not dare to assume the head-ring without the permission of his chief, and there is no surer mode of gaining permission than by distinguished conduct in the field, whether in open fight, or in stealing cattle from the enemy.

The necessity for undergoing some rite when emerging from childhood is not restricted to the men, but is incumbent on the girls, who are carried off into seclusion by their initiators, and within a year from their initiation are allowed to marry.

[20]

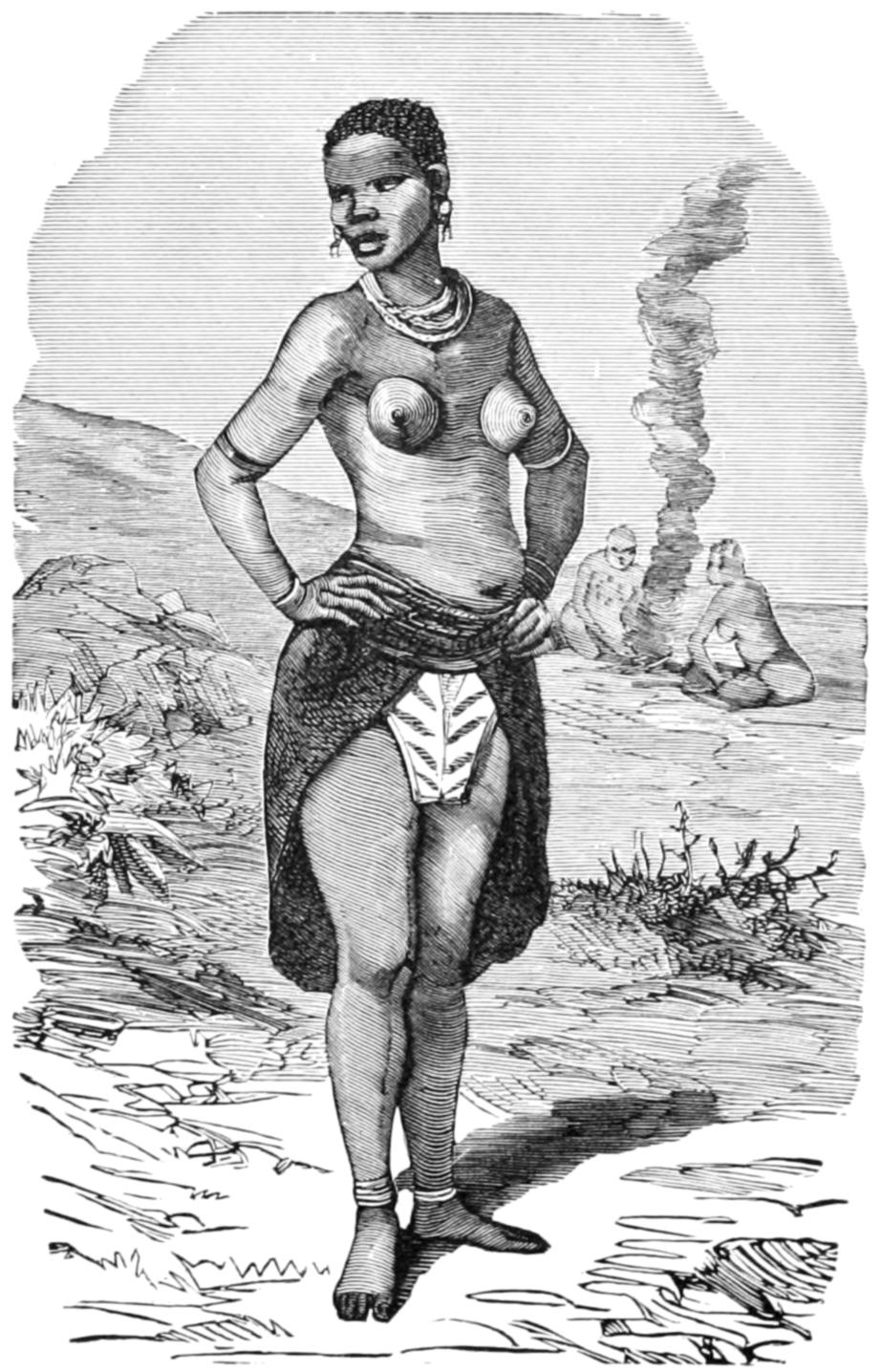

A KAFFIR’S LIFE, CONTINUED — ADOLESCENCE — BEAUTY OF FORM IN THE KAFFIRS, AND REASONS FOR IT — LIVING STATUES — BENJAMIN WEST AND THE APOLLO — SHOULDERS OF THE KAFFIRS — SPEED OF FOOT CONSIDERED HONORABLE — A KAFFIR MESSENGER AND HIS MODE OF CARRYING A LETTER — HIS EQUIPMENT FOR THE JOURNEY — LIGHT MARCHING-ORDER — HOW THE ADDRESS IS GIVEN TO HIM — CELERITY OF HIS TASK, AND SMALLNESS OF HIS PAY — HIS FEET AND THEIR NATURE — THICKNESS OF THE SOLE, AND ITS SUPERIORITY OVER THE SHOE — ANECDOTE OF A SICK BOY AND HIS PHYSICIAN — FORM OF THE FOOT — HEALTHY STATE OF A KAFFIR’S BODY — ANECDOTE OF WOUNDED GIRL — RAPIDITY WITH WHICH INJURIES ARE HEALED — YOUNG WOMEN, AND THEIR BEAUTY OF FORM — PHOTOGRAPHIC PORTRAITS — DIFFICULTY OF PHOTOGRAPHING A KAFFIR — THE LOCALITY, GREASE, NERVOUSNESS — SHORT TENURE OF BEAUTY — FEATURES OF KAFFIR GIRLS — OLD KAFFIR WOMEN AND THEIR LOOKS.

When the youths and maidens are in the full bloom of youth, they afford as fine specimens of humanity as can be seen anywhere. Their limbs have never been subject to the distorting influences of clothing, nor their forms to the absurd compression which was, until recently, destructive of all real beauty in this and neighboring countries. Each muscle and sinew has had fair play, the lungs have breathed fresh air, and the active habits have given to the form that rounded perfection which is never seen except in those who have enjoyed similar advantages. We all admire the almost superhuman majesty of the human form as seen in ancient sculpture, and we need only to travel to Southern Africa to see similar forms, yet breathing and moving, not motionless images of marble, but living statues of bronze. This classic beauty of form is not peculiar to Southern Africa, but is found in many parts of the world where the inhabitants lead a free, active, and temperate life.

My readers will probably remember the well-known anecdote of West the painter surprising the critical Italians with his remarks. Bred in a Quaker family, he had no acquaintance with ancient art; and when he first visited Rome, he was taken by a large assembly of art-critics to see the Apollo Belvedere. As soon as the doors were thrown open, he exclaimed that the statue represented a young Mohawk warrior, much to the indignation of the critics, who foolishly took his exclamation as derogatory to the statue, rather than the highest and most genuine praise. The fact was, that the models from whom the sculptor had composed his statue, and the young Mohawk warriors so familiar to West, had received a similar physical education, and had attained a similar physical beauty. “I have seen them often,” said West, “standing in the very attitude of this Apollo, and pursuing with an intent eye the arrow which they had just discharged from the bow.”

There is, indeed, but one fault that the most captious critic can find with the form of the Kaffir, and that is, a slight deficiency in the fall of the shoulder. As a race, the Kaffirs are slightly high-shouldered, though there are many instances where the slope from the neck to the arm is exactly in accordance with the canons of classic art.

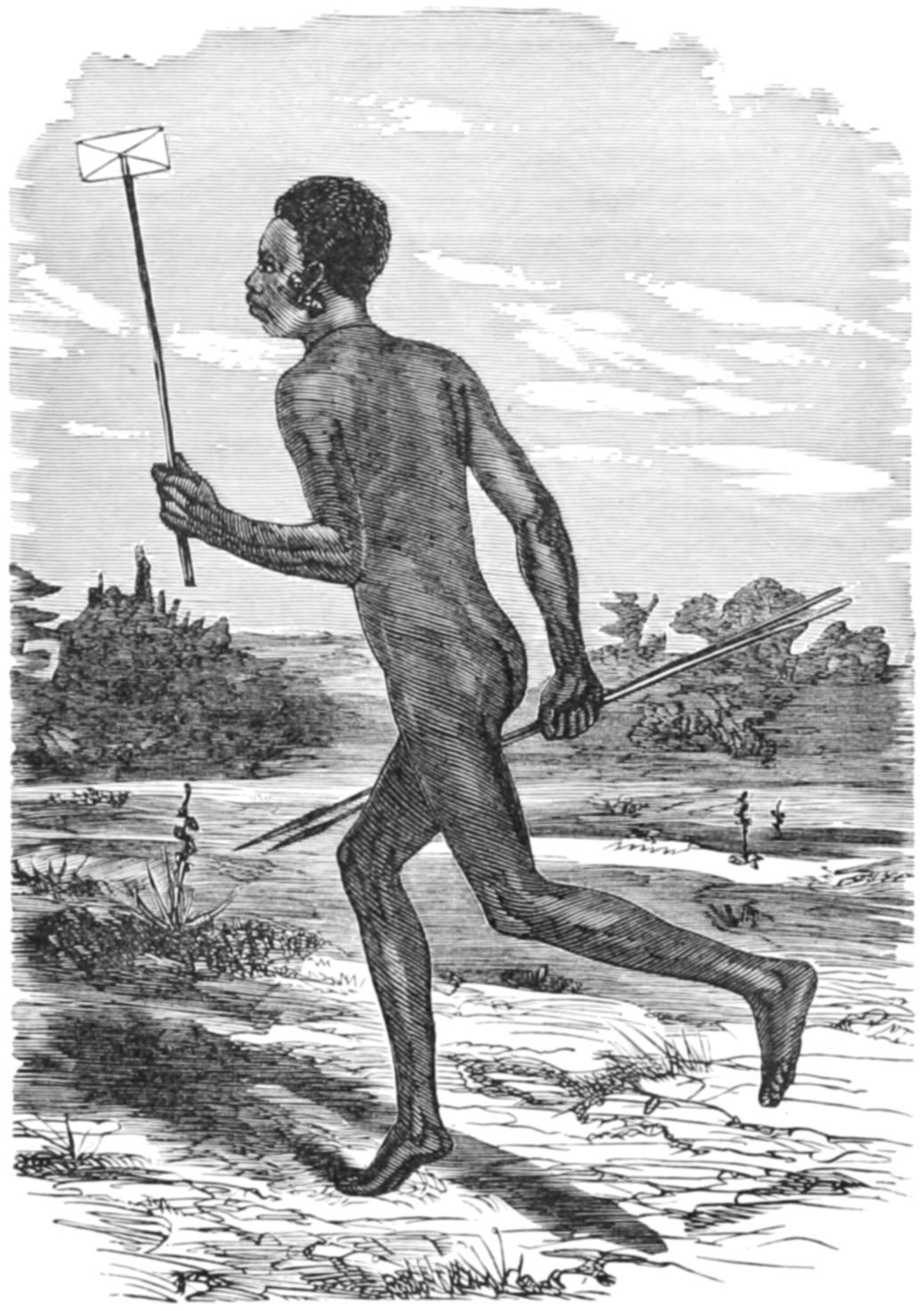

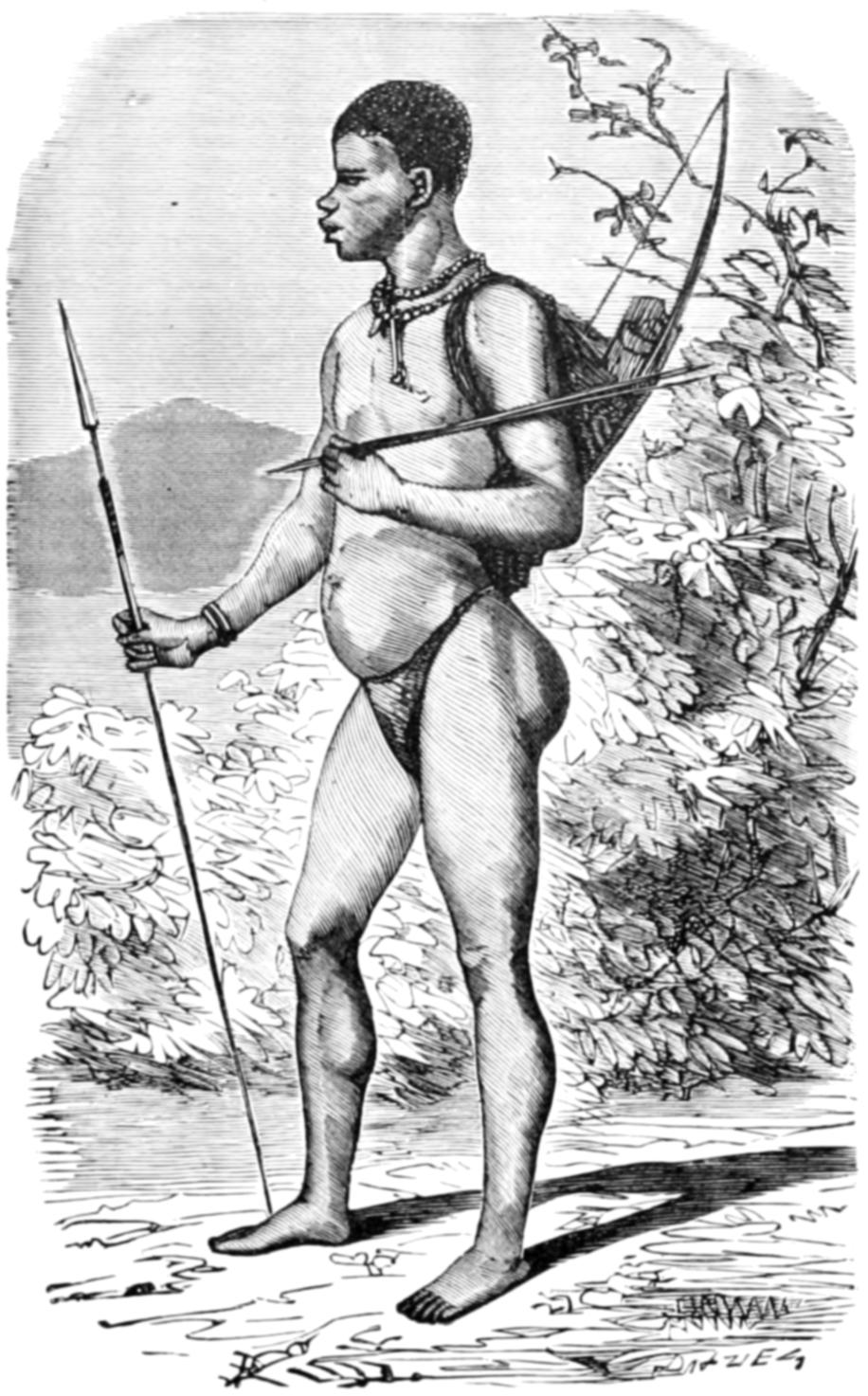

These young fellows are marvellously swift of foot, speed reckoning as one of the chief characteristics of a distinguished soldier. They are also possessed of enormous endurance. You may send a Kaffir for sixty or seventy miles with a letter, and he will prepare for the start as quietly as if he had only a journey of some three or four miles to perform. First, he cuts a stick some three feet in length, splits the end, and fixes the letter in the cleft, so that he may carry the missive without damaging it by the grease with which his whole person is liberally anointed. He then looks to his supply of snuff, and, should he happen to run short of that needful luxury, it will add wings to his feet if a little tobacco be presented to him, which he can make into snuff at his first halt.

(1.) YOUNG KAFFIR ARMED.

(See page 20.)

(2.) KAFFIR POSTMAN.

(See page 20.)

[23]

Taking an assagai or two with him, and perhaps a short stick with a knob at the end, called a “kerry,” he will start off at a slinging sort of mixture between a run and a trot, and will hold this pace almost without cessation. As to provision for the journey, he need not trouble himself about it, for he is sure to fall in with some hut, or perhaps a village, and is equally sure of obtaining both food and shelter. He steers his course almost as if by intuition, regardless of beaten tracks, and arrives at his destination with the same mysterious certainty that characterizes the migration of the swallow.

It is not so easy to address a letter in Africa as in England, and it is equally difficult to give directions for finding any particular house or village. If a chief should be on a visit, and ask his host to return the call, he simply tells him to go so many days in such a direction, and then turn for half a day in another direction, and so on. However, the Kaffir is quite satisfied with such indications, and is sure to attain his point.

When the messenger has delivered his letter, he will squat down on the ground, take snuff, or smoke—probably both—and wait patiently for the answer. As a matter of course, refreshments will be supplied to him, and, when the answer is handed to him, he will return at the same pace. Europeans are always surprised when they first see a young Kaffir undertake the delivery of a letter at so great a distance, and still more at the wonderfully short time in which he will perform the journey. Nor are they less surprised when they find that he thinks himself very well paid with a shilling for his trouble. In point of fact, the journey is scarcely troublesome at all. He has everything his own way. There is plenty of snuff in his box, tobacco wherewith to make more, the prospect of seeing a number of fellow-countrymen on the way, and enjoying a conversation with them, the dignity of being a messenger from one white chief to another, and the certainty of obtaining a sum of money which will enable him to adorn himself with a splendid set of beads at the next dance.