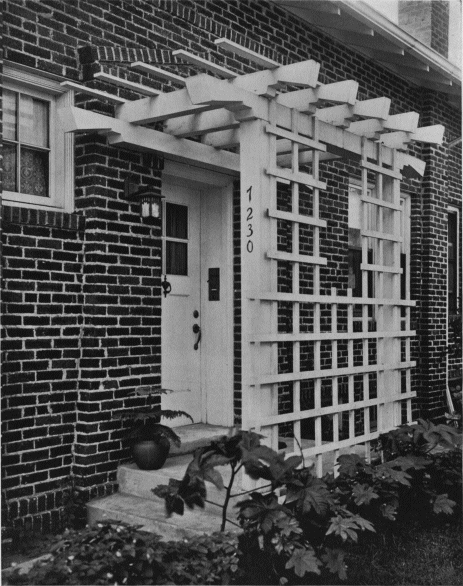

Doorway of Face Brick Cottage, Chicago. Designed by J. Scheller

American Face Brick Association

110 SOUTH DEARBORN STREET

CHICAGO

Copyright 1920 by John H. Black for A. F. B. A.

| Modern Brickmaking | 7 |

| Pre-eminent Merits of Face Brick | 9 |

| Types of Face Brick Wall | 15 |

| Putting in Foundations | 17 |

| Solid Face Brick Construction | 18 |

| Face Brick on Hollow Tile Construction | 25 |

| Face Brick Veneer Construction | 26 |

| Special Uses of Face Brick | 29 |

| Brick Bonds | 33 |

| Mortar Joints | 35 |

| Increasing Fire Protection | 37 |

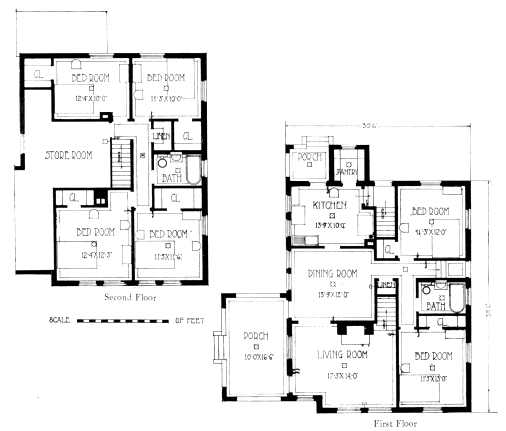

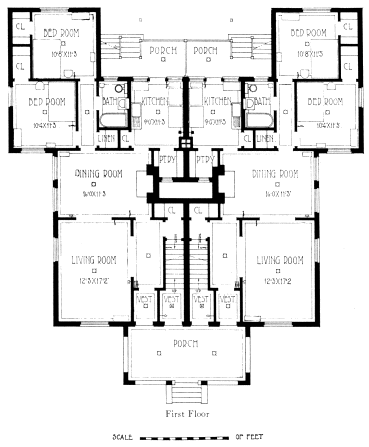

| Face Brick House Designs | 40 |

| Useful Tables and Suggestions | 104 |

| Problems in Estimating Quantities | 107 |

| Glossary of Usual Terms in Bricklaying | 110 |

| Index and List of Illustrations | 112 |

| Members of Association | 114 |

No man has more reason to feel pride and satisfaction in his art than the builder. From the time when men wove together branches of trees or piled up loose stones and mud for shelter to the present day, when they erect huge heaven-soaring structures of steel to house a multitude, the builder has played a most important part in the progress and development of human civilization.

Fundamentals of Building

The old Roman authority on architecture, Vitruvius, long ago laid down the three fundamentals of all good building, viz., firmness, utility, and charm. In working for firmness (strength, durability) and for utility (serviceableness, convenience), the builder, we might say, is an engineer; in seeking to give charm (attractiveness, beauty) to his work, he is an artist. In other words, the builder always has before him structural and artistic problems which, aside from his wit in planning the inner conveniences and serviceableness of the house, depend largely upon the material he chooses to work in. To what extent does this material meet the structural requirements of strength, permanence, durability, and to what extent the artistic requirements of attractiveness, charm, beauty, are the main issues.

Aim of This Book

This book is meant not only to show how perfectly brick, as a building material, meets all of these requirements, but to serve as a Manual for the master carpenter builder in offering various designs and plans of face brick houses, and in pointing out the practical methods of constructing either the solid brick, hollow tile, or veneered wall.

In fact, the book in many ways will be of use to the mason who will doubtless find in it helpful suggestions on the application of his craft to the problems of building.

Before giving briefly the reasons for the use of face brick, a word about the history of brick and its manufacture may be of interest.

The manufacture and use of brick go back to the remotest antiquity, far beyond the earliest recorded history, which is supposed to be about 3,800 B. C, the date of a clay tablet assigned to the age of Sargon of Akkad, founder of the Chaldean dynasty, fully two thousand years before the time of Abraham.

Babylonian Origin

Naturally the use of brick originated where clay, of which they are made, was abundant; and there is every reason to believe that the brick industry had its beginning in the broad alluvial valley of the Euphrates which is the traditional cradle of human civilization. At any rate, according to one authority, good brick have been taken from excavations in old Babylonia, dating back to 4,500 B. C, as good as the day they were made. And the same authority adds that brickmaking was doubtless practiced ten thousand years ago. It was Nature that gave the hint, for the sun hardened the mud along the river bank and cracked it into irregular pieces which the native could utilize, after shaping them to the desired size, for piling up in the walls of his crude hut. It was an easy step in advance to shape the mud beforehand while soft and lay it out in the sun to bake. This produced what we call adobe brick, afterwards greatly improved by mixing chopped reeds or straw with the soft mud before baking. It will be remembered how the Egyptian Pharaoh embittered the slavery of the children of Israel by compelling them to find their own straw for the brick they were required to make. At a very early date the dwellers in the Euphrates valley learned to burn brick, as indicated by the biblical story of the Tower of Babel; and by the time of Nebuchadnezzar, the great Babylonian king (604-562 B. C), not only were well-burned brick made and used extensively, but colored enamels were successfully applied for decorative effects. Considerable remains of this ancient brickwork are still found, although for many centuries the ruined cities of the Mesopotamian plain were used as sources of building material for the more modern cities which have since come into being.

Spread of the Craft in Antiquity

From the Euphrates, brickcraft spread eastward to Persia, India, and China, and westward to Egypt, Greece, and Rome. The Romans, who were the great builders of ancient times, made very extensive use of brick in their immense building operations, wherever good clay could be found. From the numerous monuments of Roman brickwork that still remain, the brick are seen to be of an excellent hard-burned quality, and generally of a large, flat, thin rectangular or triangular form.

Brickwork in the Middle Ages

When the nations of Europe took form out of the ruins of the Roman Empire, they inherited among other arts that of making brick, and subsequently carried it to a higher state of development, especially in countries such as Northern Italy, Southern France, the Netherlands, and Northern Germany, where the absence of good building stone gave a natural impulse to brickmaking. In the great Gothic epoch of the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, brick enjoyed a wide vogue and was freely and effectively used in the best types of building such as city halls, great churches, palaces, and mansions of the wealthy.

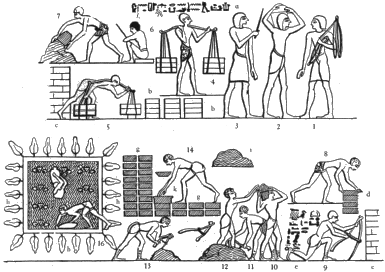

Fig. 1. Man returning after carrying the bricks.

Figs. 7, 9, 11, 13. Digging and mixing the clay or mud.

Fig. 16. Fetching water from tank (h).

Figs. 3, 6. Taskmasters.

Figs. 4, 5. Men carrying bricks.

Figs. 8, 14. Making bricks with a wooden mold, d, k.

At e the bricks (tobi) are said to be made at Thebes.

Foreign captives employed in making bricks at Thebes.

From Wilkinson's Ancient Manners and Customs of the Egyptians

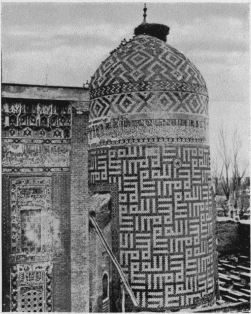

Brickwork in old Persian Tomb at Ardebil

In England

The use of brick in England began with the Romans in the early centuries of our era, but native brickmaking does not appear until well after the days of Magna Charta. In Henry VIII's time, English brickmaking, probably under Flemish influence, was greatly developed. But it was not until the days of Queen Anne and the Georges, in the eighteenth century, that brick building reached its greatest vogue, so much so that brick nearly drove out all other materials. This period accounts for those fine old country houses so representative of substantial comfort and dignity, scattered throughout England, which delight the eye of the traveler today. And ever since that time English builders have maintained a fine sense of the architectural values in sound and beautiful brickwork, as may be seen in many splendid examples of modern construction.

The Use of Brick in America

In America, aside from the adobe construction which the Spanish found in Mexico and Peru, the first brick were brought over from England or Holland. The native industry, however, had an early start in the seventeenth century, so that the Colonial times saw many fine specimens of brick building from New England to Virginia.

In the nineteenth century, up to about 1880, there was no general attempt to use brick to the best advantage. For the most part the brick building of that period was confined to the use of common brick for ordinary construction or for backing stone-faced walls. From that date, however, to the present, a growing taste has demanded and secured artistic effects in the brick wall by the use of specially manufactured face brick which, in a bewildering variety of beautiful color tones and textures, have been sympathetically and artistically treated by our leading architects, as may be seen all over our country.

It is a long cry from the primitive method of mixing and molding brick by hand and drying them in the sun, to the modern technical methods and power machinery used by the American manufacturer. Determined by the kind of material, whether surface clay, fire clay or shale, and the kind of brick wanted, there are three chief methods of manufacture, slop-mold, wire-cut, and dry-press.

By the first method, the clay, in a soft condition, is pressed by the machine into molds which have been flushed with water—hence the term slop-mold—or sprinkled with sand, in which case the brick are called sand-mold. By the second method, the clay or shale is ground and tempered into the consistency of a stiff mud which is forced by an auger machine through a die, in the form of a stiff mud ribbon, having the cross section of a brick. This stiff mud ribbon is carried by a belt to a steel table under a series of piano wires strung on a frame which is revolved by the machine at proper intervals, cutting the clay ribbon into the desired sizes. These stiff mud machines will turn out as many as 100,000 face brick a day, and in some common brick plants they are built for a 250,000 to 300,000 daily output. The dry-press method reduces the clay to a fine granular form which is then, in nearly a dry condition, forced under immense pressure into the proper sized molds.

The brick as they come from the machines are known as "green" and require, except in the case of the best dry-press brick, a certain period of drying before being set in the kilns where, for from five to ten days, depending on the quality of the ware and the general conditions, they are subjected to a process of burning before they are ready to be built into the wall.

Burning the Brick

This process of burning passes through three main stages which require very skillful attention on the part of the burner. First, the water chemically combined with the material must be driven off; then the various impurities of the clay must be burnt out or oxidized; and finally, the ware, except in case of fire clays, must be brought to the point of incipient vitrification. Throughout the whole process there is danger of distortion or discoloration in the ware unless the fires are skilfully handled. Properly done, the brick come out of the kiln in their beautiful, natural colors, due to the constitution of the clay or the various metallic oxides contained in it. To enhance these effects, different clays are sometimes mixed in going through the machines, certain ores may be added to modify the color, the brick surfaces may be scored in various ways, or the ware may be set in the kiln so as to avoid or get the flash of the fire. So that when you specify a fine face brick, you are getting a product which Nature has taken long to create and to which man has devoted his best scientific knowledge and inventive art.

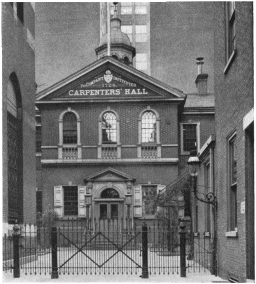

The Philadelphia Carpenters used Brick Two Centuries Ago

A Wide Choice Offered

The American manufacturer of face brick has far outstripped the rest of the world in the wide range of color tones and textures he offers. So that the prospective builder has before him the possibility of giving to the exterior wall surface an enduring color scheme of monochrome uniformity or polychrome blending, as his taste may dictate. The whole sweep of color, in smooth or rough textures, is at his command from the pure, severe tones of pearl grays or creams, through buff, golden, and bronze tints to a descending scale of reds, down to purples, maroons, and even gun metal blacks. Thus, instead of building for your client a house of a dull, insubstantial, unattractive appearance, you can, by the use of face brick, build a substantial, enduring house that presents to the eye a veritable symphony in color, at once a satisfaction to yourself as well as to him, and a cause of appreciative remark by his neighbors or the casual passersby. It will always stand to the credit of your art as a builder.

Growing Demand for Brick Houses

You represent the best work that can be done in your community. People come to you when they want to build because they know you as an able designer and one capable not only of giving them sound advice but of carrying the work through to a successful termination. Why then confine yourself to one type of building such as frame or stucco?

More and more people are going to ask you about a brick house, and for very good reasons which we intend shortly to give you. Why not tell them you can build a brick house as easily as you can one of frame or stucco; and what is more, why not tell them the fact, viz., that it is a better house in every way, safer, more enduring, more comfortable, more attractive, and in the end more economical!

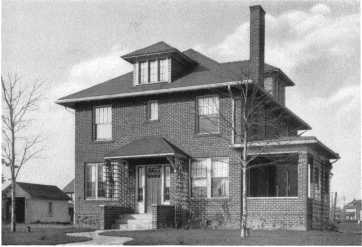

Face Brick Residence, Canton, Ohio. James Buehl, Architect

Enlarge Your Field as a Builder

You will thus greatly enlarge your field of action, increase your profits, and gain a much higher standing in the community as an all-around builder. If you hesitate about taking up building in brick, it is doubtless because you share the common erroneous belief that it costs your client too much, or because you think it outside of your building practice, presenting difficulties you do not care to face. But we are very sure that a careful reading of this Manual will convince you of the pre-eminent value of the face brick house for your client, and of your complete competence to build it for him.

What You Owe to the Community

Then we want you to read this Manual because, as a citizen, you owe something to the community in which you live. And as a builder you can discharge that obligation in no better way than in building more enduring and more beautiful houses, as you can by building in brick. By doing so, your dividends will be not only in material rewards but in a higher standing among your fellow citizens. You owe it to yourself to make the most of your noble craft and thus take the place in the community to which it entitles you.

The material you put into the walls of a house should, as Vitruvius said, always have structural and artistic merit. Face brick have both in a striking measure, and in consequence can show the strongest economic and personal reasons why they should be used.

Structural Merits of Face Brick

Structurally, bricks are a material easy to handle and when laid in the wall endure the heaviest pressures and strains. Hardened and matured in fire, they resist the ravages of flame. Examine the scene of any conflagration for evidence. Nor will they corrode or decay with the passing of time, as remains of ancient brickwork abundantly prove.

Artistic Merits of Face Brick

Artistically considered, face brick excel all other materials. Even a well-burned, selected common brick, with proper bond treatment and mortar color, may be made attractive, but the endless variety of color tones and textures found in face brick give to the artistic sense of the builder an unlimited choice. This variety is such that the most diverse tastes may be met in uniform shades or, preferably, in blended tones of the most delicate and charming effects. No other building material can approach face brick in the possibility of color schemes for the wall surface, either within or without—and the colors last, for they are an integral part of the enduring brick.

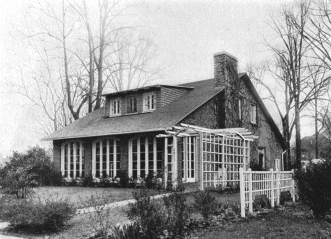

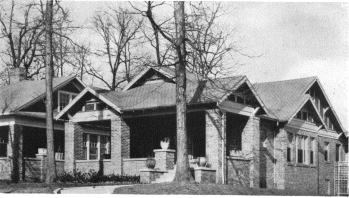

Glimpse of an Attractive Chicago Face Brick Cottage

Face Brick Residence, Chicago. L. J. Batchelder, Architect

Effect of Bond and Mortar Joint

But this is not all there is to be said on the artistic side by any means. The structural necessity of bonding the brick makes possible any number of beautiful bond and pattern effects, as illustrated on pages 33-35; and the kind of mortar joint, struck, cut flush, tooled, or raked (Fig. 57), properly toned with a color to harmonize with the brick, produces the most charming results which, in sunshine or shadow, give ever varying artistic effects.

In the beauty of brickwork, you have a great opportunity to arouse and hold the interest of your possible clients. On that basis alone you can make a strong appeal in offering your services.

Economic Merits

But perhaps the strongest appeal you can make is based on what naturally grows out of the strength and beauty of good brickwork, and that is real economy. But don't be deceived by the superficial error of initial cost. A $4.00 pair of shoes are cheaper than a $5.00 pair, it is true, but if the $5.00 pair fit better, look better, and wear twice as long, the $4.00 pair are dearer, and you would lose not only in money but in personal satisfaction by getting them. Real economy would lead you to buy the $5.00 pair.

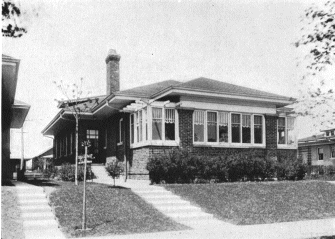

Face Brick Bungalow, North Evanston, Ill. Robert E. Seyfarth, Architect

The Importance of Building a Home

Much more is this principle true in building a house. It is a very important undertaking for every man, for it involves considerable outlay of money and intimately concerns his comfort and welfare for a long period of years. A man rarely builds more than one house in his life-time, so that it is a serious matter to make a mistake,—he will always regret it. In other words, when he builds, he wants to avoid fooling himself, as he does, if he builds wrong; he wants to build right at the very start. This is what he certainly can do by building with brick. For out of the structural strength and artistic beauty of brick he gains advantages that make it the most economical investment in the end.

Upkeep or Maintenance

Take the items as they come, in their effect upon the value of the house. First, there is upkeep. So far as brick enter into the construction of a house, it requires practically no maintenance. You do not have to patch, repair, or paint a brick wall,—it wears. It is as sound in twenty-five years as the day it was built, and even more attractive. Figure up the paint bill for a frame house in ten years, then add the various little repairs necessitated by the shrinking, cracking, and decaying of wood exposed to the weather, and you have a neat little bill of upkeep, for the frame house, which is exactly nothing for brick.

Depreciation

Next consider depreciation which is a separate item from maintenance or upkeep, and is practically nil in the case of the brick house. Appraisal engineers have estimated it, for the brick house, at only one per cent a year, beginning after the first five years. And the one per cent in reality should apply only to such portions of the building as are subject to wear, as finished floors, plumbing, hardware, roofs, and the like. Approximately 60 per cent of a well built brick house does not depreciate at all through a long period of years. On the other hand, a frame house, according to the same authorities, begins to depreciate from the day it is finished at from 2 to 3 per cent annually. At the lowest estimate of 2 per cent a $6,500 frame house would depreciate $130 a year or $1,300 in ten years. A similar house of brick, worth let us say $7,000, would depreciate, allowing the full one per cent, $70 a year from the fifth year on, or $350 in ten years. That is, when you add to the $350 depreciation the $500 excess cost of the brick house, the resulting $850 is still less by $450 than the depreciation alone on the frame house. The wear and tear of time do not allow us to get away from these facts.

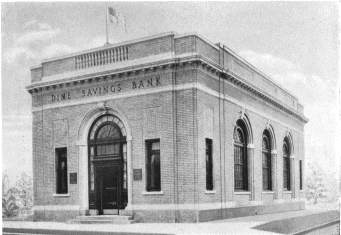

Face Brick Bank Building, Detroit. Geo. M. Lindsey Co., Architects

Saving on Insurance Rates

Furthermore, there is the matter of fire insurance, not a large one, but growing in the course of years to an appreciable sum. The reason for better insurance rates on the brick house is one that makes the strongest appeal to a man, and that is, safety from the fear and fact of fire, protection for himself and family from a justly dreaded misfortune. Acting on this reason, the insurance company will put from 19 to 37 per cent higher rate on a frame or stucco than on a brick house. Besides, you can carry 20 per cent less insurance on the more substantial structure.

Comfort and Health

Again the builder must consider the question of comfort and health. An 8-inch furred brick wall will require less coal to keep the house warm than in case of frame. This saving, however, is not nearly as important as uniform comfort which, especially in winter, has a vital bearing on the health and welfare of the family, more particularly as it affects very young or delicate children and old people, or even the strong who may, for the time being, be indisposed. The man who builds a good brick house saves on his coal and doctor bills.

Face Brick Bungalow, Chicago, Ill. J. R. Stone, Architect

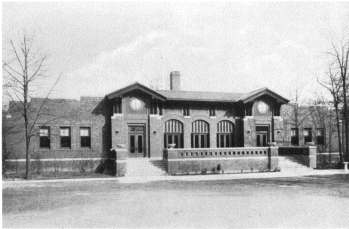

Face Brick Public Library, Coatsville, Ind. Graham & Hill, Architects

Economic Value of Beauty

But if the brick house, because of its structural merits, is more economical on the score of upkeep, depreciation, insurance rate, comfort and health, it has a money value because of its artistic appearance. The substantial and attractive appearance of a face brick house makes the same appeal to everybody else as it did to the owner when he built it, so that if he desires, he can borrow more money on it, or if he must, can sell or rent it to better advantage. Beauty has a real economic value.

Sentimental Value an Asset

Finally, there is a sentimental value in owning the better house which can't be put in terms of money but is, nevertheless, real in terms of personal satisfaction. Every man feels a certain justifiable pride in his home if he knows that others admire it. This exerts an unconscious influence on him and raises his sense of self-respect. Besides, as a good citizen, a man should make his home as attractive as possible, not simply in the way of doing his share to improve his neighborhood, but as showing what he and his family stand for before the community, the soundest and best things.

Taking it all in all, you can tell your clients that in building a face brick house, they get more completely than in case of any other material the structural values of permanence, fire-safety, comfort and health, and the artistic value of beauty, out of which follow a real economy and a genuine personal satisfaction. - 12 - What, then, are the facts about the real economy of a face brick house? To begin with, we frankly admit and, in fact, assert that such a house costs more than the less substantial frame or stucco house,—as it ought, because it is worth more. It wears better, it looks better, it sells and rents better. You can never get something for nothing. You have to pay for it. But what we can show from actual figures is that the face brick house at the start costs only a little more than the frame or stucco house and in the end, when all the bills are paid, costs much less. It is a question of initial and final cost. Let us first look at the initial cost.

The Test of Figures

The accompanying table gives the results of actual figures obtained during the past ten years from all parts of our country by face brick manufacturers. As the prices of material have changed greatly, during the period in question, the percentages of difference will prove to be the only instructive figures, and are calculated on the total costs of the houses. The bids for 1919 we have in our files for reference and we are ready to show them to any interested person. As frame construction is generally the lowest, we take it as the base of comparison and give the percentage in excess over frame for (1) a solid, 8-inch brick wall, or face brick on common brick backing; (2) a brick veneer wall, or face brick in place of clapboards or shingles on frame; (3) a face brick on hollow tile wall, 8 inches thick; and (4) a stucco on frame wall.

A moderate sized 7-room dwelling is used as a typical example and is the same in every respect, except the exterior wall construction. First class face brick are used and the solid wall is furred.

Table of Percentage Differences

| Year | Frame | 1 Brick |

1 Veneer |

1 Tile |

1 Stucco |

| 1910 | 0.0% | 9.1% | 6.9% | 10.7% | 2.9% |

| 1913 | 0.0% | 8.1% | 5.9 | ..... | 4.0% |

| 1915 | 0.0% | 6.9% | 4.9 | ..... | 1.6% |

| 1919 | 0.0% | 5.1% | 4.4% | 6.5% | 0.1% |

Face Brick Store Front, Birmingham, Ala. W. M. C. Weston, Architect

These figures represent from nine to twenty-two bids in each case, on which the average is given. Different contractors in the same place and different parts of the country sometimes show considerable divergence, but in view of the wide territory from which these bids have been gathered and the time covered, the averages may be taken as indicative of about the constant percentage of difference in initial cost.

The Face Brick House Saves Money

It should be noted, in the case of the 8-inch solid brick wall and the brick on tile wall, that they are both over two inches thicker than the frame or stucco wall. But taking the 8-inch face brick solid, or hollow tile, wall as a fair comparison with frame and stucco, you can readily calculate what you really save by paying a little more at the start for the more substantial construction. Reverting to the economies of the face brick house you will find that the maintenance and depreciation items alone on the frame construction will, in a very few years, entirely wipe out the 5 or 6 per cent excess initial cost of the brick, to say nothing of all the other items that go to make your face brick home all the time an investment of a permanent and remunerative value.

Thus, a $7,000 frame house would mean, figuring excess cost at 6 per cent, a $7,420 face brick house. Depreciation at the lowest estimate of 2 per cent annually on the frame in five years would be $700; add to this a repainting bill of $250 and you have a total of $950. For the five years under consideration there would be no - 13 - depreciation at all to be calculated on the brick house, but a repainting bill of about 385 for doors, windows, and outside trim would have to be charged up. This means that the difference of 3865 between frame and brick upkeep or maintenance covers, in five years, more than twice the $420 excess initial cost of the brick. You may well suggest to your client that to be penny wise and pound foolish in building a home looks like an inexcusable folly. As you are his trusted adviser in all such important matters, you can not avoid your obligation of giving him the advice best suited to his interests.

Face Brick Primary School, Highland Park. Holmes & Flynn, Architects

Lumber Enters into the Problem

Please note in the figures of the table the decided tendency toward a diminished difference of percentages. The probable explanation is the rising price of lumber which has, from all accounts, by no means reached its crest, and which is forced by the tremendous demand now being made for that material in the world markets. Lumber is one of those staples of such wide and varied use that it is well to consider seriously its conservation, both in guarding its supply and in maintaining a reasonable price. We are all interested, for everybody at one time or another uses some form of lumber.

Face Brick Store Front, St. Louis, Mo. Preston J. Bradshaw, Architect

Need of Saving Lumber

However wide and varied the normal use of lumber may be, it is at the present time, due to the conditions in which the great war has left us, subject to abnormally excessive demands and will be for a period of years to come. When you consider that even in fireproof homes built of concrete, stone, or brick, lumber bears from 20 to 25 per cent of the cost of the building, and that now 80 per cent of the houses in the United States are built entirely of wood, you can easily guess why so much used to be said, even in pre-war times, about the disappearance of our forests and the advancing prices of lumber.

The Wastes of War

But picture what the war has done, and its inevitable effect upon the demand for lumber. According to a comprehensive report on the Direct and Indirect Costs of the War recently issued (November, 1919) by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, the direct cost to the warring nations amounts to 186 billions, of which the property loss on land was thirty billions and on sea seven billions. To this must be added forty-five billions as - 14 - loss of production. That is, not only were vast amounts of property destroyed, but the normal supply was greatly lowered. Take the matter of houses alone, not only were great numbers of them destroyed in the warring zones, but neither could they be replaced, nor could the new houses be built which were normally required by the community. Fortunately for us in America the war destroyed no property, but for a period of two years it prevented normal building to the extent of hundreds of thousands of houses. As a consequence, in Europe all the waste places must be rebuilt and, in both Europe and America, new houses in great numbers must be erected to catch up with normal requirements. There is a house famine the world over.

Attractive Small Face Brick House, Buffalo, N. Y. Thos. A. Fisher, Designer

The Lumber Burden of America

Where is all the needed lumber so lavishly used in building to come from? The average normal supply would not be sufficient and the supply cannot be increased for a period of years simply because Russia, which normally supplies 50 per cent of the lumber for the European markets, has fallen into such industrial chaos, and needs so much material for her own reconstruction that, according to one authority, she will not be able to export lumber again before 1922 or 1923. In consequence, the burden of supplying lumber to the world market at the present time will fall upon America. The effect upon prices, as well as upon quality of product, will be inevitable. The excessive demand will not only compel injurious denudation of our forest lands, but will more and more force the cutting of inferior timber.

How to Save Lumber

In view of such conditions there is urgent need of conserving our lumber supply by every available means, the simplest and most direct of which is to confine lumber strictly to its legitimate uses or, at any rate, not use it where more fitting materials are at hand. Take the abnormal demand pressure off lumber in every possible way, and we reduce the danger of a lumber famine that threatens us for some years to come. Thus, lumber should not be used in the exterior walls of a house, where it is exposed to the vicissitudes of the weather or to the trial of fire, especially when building material such as brick, which is nearly as cheap, and considering its durability and fire-safety, far more economical, is everywhere in evidence.

Lumber has its very legitimate and varied uses, but among them is not outside work where wind and rain and frost and fire search out its weaknesses. In view of its very nature and the great variety of its proper uses, it should never displace the exterior masonry wall, which in stone, tile, or brick makes the most secure and enduring structure. If the 80 per cent of building in this country, now done of frame, were put into brick, or other durable and fire-resistive materials, it would result in a great economic national gain, people would have better and more substantial houses, and the lumber which everybody needs would be conserved for the legitimate uses to which it is admirably adapted.

There are three possible ways of using face brick in building a wall, determined by the backing up material employed, each of which will be given special attention in the following pages.

First, there is the solid brick wall, consisting of face brick with a common brick backing. Of the strength, permanence, and structural value of this construction there can be no question. Objection is sometimes made to its cost but, in view of the facts we give later, this objection loses its force and proves to be a claim of actual economy. The only other objection heard is that of the dampness of the wall. This comes from one or both of two causes, pervious mortar joints, or sweating due to condensation of interior moisture on the cooled wall. Either condition may be completely overcome by furring the interior wall surface, a method recommended in this Manual, and provided for in the plans offered. The furring provides an air space that insulates against dampness and cold. With this furring, the other methods, sometimes employed, of mixing so-called waterproofing material with the mortar or of using colorless liquid waterproofing on the surface of the brickwork are not necessary. Even the furring, in certain climatic conditions as proved out by local experience and practice, is not needed. But in any case, it must always be seen that all the exterior joints of the wall, especially the head or vertical joints, are solidly filled with mortar. The possibility of efflorescence, which occasionally appears on the surface of the brick when the outside of the wall has been subjected to excessive moisture, may be prevented to a great extent by avoiding such ledges and projections in construction as permit the soaking of water into the surface of the brick work. See Glossary, page 110.

Secondly, the face brick wall may be built by using hollow tile in place of common brick for backing. This wall, like that of solid brick, being all of burnt clay, has the advantage of being fire-resistive, although insurance rates are not always as favorable because, in case of fire, the salvage is not as large as with the solid wall. Some builders prefer this type of wall, claiming that it is less expensive to build and that the hollow dead air spaces act as a heat insulation, giving a drier and warmer wall. On these points we have no means of forming a definite, final opinion. Your best plan would be to consult both the common brick and hollow tile people so as to form a judgment of your own on the subject. Either wall is sound construction and will give you entire satisfaction.

The third type of wall, known as veneer, is simply the application of face brick to the wooden framing of a frame house, in place of the clapboards or shingles. Although, as a substantial or a fire restrictive wall this type is not equal to solid brick or hollow tile, it has its friends among builders, largely on the score of local custom, familiarity, speed of construction, and cost. What it has to recommend it is the fact that in outer appearance and value it is a brick house, and in reality a big step in the right direction. But whichever type of wall you build, it is the face brick that gives to it character, distinction, class, all of which means not only deep personal satisfaction to the owner, but real money in higher rental or sales value, far in excess of the initial cost of the face brick over poorer and less attractive material.

Face Brick Bungalow, Atlanta, Ga. Leila Ross Wilburn, Architect

Take the frame wall. Where it is exposed to the weather, it shrinks, decays, and depreciates, requiring repeated paintings and repairs. Now substitute, at an added cost of only 4 or 5 per cent, a fine face brick for the drop siding and at once there is practically cut out painting, repairs, and depreciation. The brick veneer has surrounded the house with a solid, monolithic, permanent, windproof, shell of fireproof material, so that in consequence the owner has on the exterior, to all intents and purposes, the - 16 - strength and beauty of a face brick house. Besides his own personal satisfaction, he has added many times more than 4 or 5 per cent to the market value of his property. Or, suppose your client has an old frame house that is built on a good plan, but outwardly grown dilapidated in appearance and hard to rent or sell. Induce him to veneer it with an attractive face brick, as we explain on a later page, and for every dollar he puts in he will get two out.

Then take hollow tile wall construction and compare the value of it finished with stucco or with face brick. The face brick will cost from 2 to 3 per cent more on the cost of the house, but what will it give the owner in wear, appearance, and solidity of construction! If you stucco hollow tile the interior face of the wall in most cases must be furred. If you use face brick, not only additional solidity and strength are added to the wall but if, as we recommend throughout this Manual, an air space is left between brick and tile, the inside furring is not needed. Besides, stucco is apt to stain, crack, or, in damp climates with freezing weather, peel off in spots, presenting an unsightly appearance. You can assure your client, who is debating between stucco and face brick, that years of usage will prove the brick surface to be both in artistic appearance and actual economy by far the better investment. It costs a little more at the start, but is worth much more in the end.

Or, it may be that your client concludes to build a thoroughly good solid brick wall, but wants to save 3 to 4 per cent on the total cost of the house by using common brick throughout. This will be a good wall, no doubt, but how will it look! Common brick are not made with an eye to external appearance; their great merit lies in solid structural value. Occasionally a well-burned selected common brick, made of a clay that burns to a good color may be found and used, with proper care of bond and mortar joint, for facing purposes; but as a rule, the method of manufacturing common brick, and the structural uses for which they are intended do not contribute to the attractiveness of the wall surface. Hence, the natural development of the great face brick industry which adds to the solid structural merits of brick the invaluable merit of looks.

And how much do looks have to do with both the sentimental and commercial value of a house! What does the good wife think of the looks of the house she lives in? What do the neighbors think of it? And to be purely practical, what does the prospective renter or buyer think of it? You know that when a man wishes to sell his house, he cleans up the yard, repairs the fence, patches up the holes, and paints the house from top to bottom because he knows the value of looks. He knows that his restoring the house to its pristine glory attracts the purchaser, helps to persuade him, and secures a far better price of sale.

Cleanliness, looks, beauty, have a very real value in dollars and cents. The same principle applies to a face brick finish of the wall surface. Face brick are made with more care, are handled and shipped with more care, and laid with more care, just for the purpose of producing a more attractive wall. When you use face brick for your clients, you give them the last word in wall construction, which is at once, as no other material, strong, enduring, comfortable, fire-safe, economical, and beautiful.

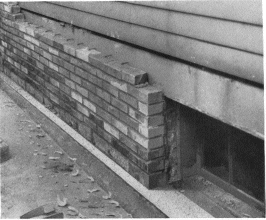

Start of Veneering over Frame Note footing below and wall ties above

Veneering above Kitchen Roof Note angle irons and work at windows

The following data have been compiled and the drawings made by Mr. George W. Repp, a Chicago architect, and are based on the most widely followed building practice.

There is no intention of trying to inform the master mason or the master carpenter about his craft with which he is perfectly familiar, but to show the master carpenter builder the best methods of handling the brick problems that may confront him in solid brick, hollow tile, and veneer wall construction. A glossary of technical terms will be found at the close of this volume.

Whatever type of construction is chosen, solid brick, hollow tile, or veneer, it should rest upon a solid brick foundation. In the majority of cases, where soil conditions are favorable, the brick foundation walls of moderate sized houses do not need a footing except at points bearing concentrated loads. Naturally, the excavation should be carried down to good solid earth, free from loose, spongy soil or filled-in ground which might later permit sufficient unequal settlement to result in serious cracks throughout the wall of the house. Where conditions seem to require a footing, it may be either of brick laid in good cement mortar (Fig. 1) or of concrete as shown in our working drawings, and should be strengthened at points of special bearing stress. Which footing is chosen will depend largely on convenience of getting local material and labor. The bottom of the foundation wall or footing must always be below frost line which, of course, varies in different sections of the country; and this rule applies as well to all brickwork outside of the foundation wall proper.

Where the conditions of soil require, porous tile with open joints should be laid around the base of the foundation wall, not above the level of the basement floor nor below the bottom of the wall or footing, and slightly pitched to a point where it may be connected with the sewer or some natural outlet. Where this tile is laid in loose sandy Soil, the open joints should be wrapped with building paper to prevent the sand from clogging the drain. In heavy clay soil, the tile should be covered to the depth of about a foot with crushed stone to prevent packing of clay around the tile.

Foundation walls, technically speaking, are those walls below the grade line of the building that support the super-structure. Similar walls around areas are termed retaining walls and are not properly a part of the foundation. The thickness of foundation, as well as other walls for different structures, is usually established by ordinance in cities and towns; but, where there are no ordinances on the subject, a brick foundation wall of 12 inches, for two-story buildings, or one of 8 inches, for small one-story buildings, conforms to good practice.

The foundation wall should be built of a hard-burned common brick, and laid in Common Bond (See Fig. 47), with a good cement-lime mortar, starting at the bottom with a header course. As the headers, which serve as transverse bond, are not long enough to extend through the entire thickness of the 12-inch, as they do through the 8-inch wall, the header courses in the 12-inch wall very naturally cannot be on the same level at the front and back of the wall. In the bottom course, the header row is laid inside and the stretcher row outside, while in the next course above the position is reversed, and so on wherever the bonding header courses come.

The first course of brick is well bedded in mortar on the footing or the solid ground, as the case may be. At the corners and at proper intervals along the wall where necessary, a few brick, four or five courses high, are laid up in the advance to serve as leads or starting points for the bond and supports for the line which guides the mason to the proper level and alignment of the brick. The mortar is well spread with the trowel along the top of the brick course, and the brick to be laid is firmly pressed down on this mortar bed next the lead. The mortar thus squeezed out of the joint is cut off by the trowel and scraped on the head of the next brick to be laid which is then pressed on the mortar bed and shoved against the brick just laid, so as to squeeze mortar into the bottom of the vertical or head joint which is then thoroughly filled from the top by slushing with mortar. The stretcher courses for structural reasons should be well slushed with mortar between the front and back rows or tiers of brick, laid to break joint.

As the work progresses, the joints on the inside face of the basement wall should be neatly struck, while the outside joints should be cut flush for receiving a waterproof coating. The inside joints are struck by running the point of the trowel, held firmly at an angle, along the - 18 - upper or lower edge of the brick, thus making a smooth beveled joint (See Fig. 57).

The wall should be widened where indicated on any plan to serve as a foundation for the fireplace, and should be built hollow to provide for an ash pit. Where other chimneys occur, the wall at their base should be corbeled out to serve as a support for them.

After the wall has risen four or five feet, scaffolding is erected to carry on the upper portion. The scaffolding, necessary for the usual house, or other small building, consists of a series of rigid horses or trestles, approximately 5'-0" wide and 5'-0" high, on which are placed a half-dozen 2" × 10" planks laid close. The joists for the floor above may be used for this planking and then lifted into place when the wall is ready to receive them, thus effecting a saving in labor. Care should be taken to keep the horses several inches away from the inside face of the wall, lest the jarring caused by bricks and mortar being deposited on the scaffold may push the green wall out of plumb. The scaffolding for the foundation wall may be dispensed with, if it is found more convenient to lay the upper portion of the wall from the outside.

All brick foundation walls should be water-proofed on the outside except in gravelly, sandy, or very dry soil. In case there is danger of moisture rising in the wall by capillary attraction, the top of the footing should be water-proofed, before starting the walls, by a course of slate well bedded in mortar or by a strip of composition roofing. In wet locations, it would be well to carry the waterproofing under the basement floor also. For waterproofing the foundation walls, in slightly wet soils where the drainage is fair, a coating of one-half inch cement plaster may be applied to the outside surface of the brick as the wall is carried up. This plaster should be composed of one part Portland cement and two parts clean, sharp sand. The possibility of settlement cracking this cement coating makes it undesirable for use in heavy soils such as wet clay, or in low-lying land where the subsoil is likely to be wet. In such conditions, a coating of asphalt applied while boiling hot, thoroughly covering the brickwork, is very satisfactory. A less expensive though excellent waterproofing, which we suggest in our specifications, is made of three parts of tar and one of pitch. Tar alone is sometimes used, but is not recommended as it becomes brittle and is subject to cracks, similar to cement. Except in dry, warm weather, it is well to prepare the wall for the waterproofing by sizing or priming it with hot creosote, to overcome any dampness that might prevent the asphalt or tar-pitch from taking proper hold.

Where ordinances do not govern, the thickness of brick walls above the foundation may be 8 inches (two brick thick) for one or two-story small houses, except in the case of an unusually high gable where the first story wall should be 12 inches (three brick thick).

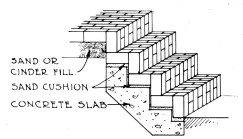

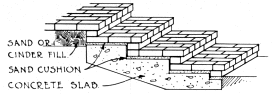

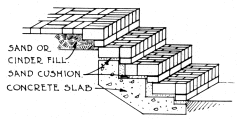

At the grade line the face brick is started, sometimes with a rowlock course or a soldier course, set either flush with the outer surface of the foundation wall or, as usual, slightly projected, in which case it is known as the water table. On the other hand, the entire base or lower portion of the building from the grade to the first floor sometimes extends as a water table beyond the wall above. Figs. 2-7 show various ways of treating this portion of the wall which add to the interest of the brickwork.

The method of laying the face brick is substantially the same as that for the foundation wall except that much greater care must be taken with the bond and mortar joints on the surface of the wall. A description of various bonds and patterns will be found on pages 33-35.

The method of bonding the face brick to the common brick backing follows the usual method Bonding means of headers every five or six courses, the headers in other than Common Bond, not used for bond, being cut in half. In the widely used Stretcher Bond where no headers occur except at corners, three methods of bonding may be employed. First, but only in case of walls 12 inches or more thick, - 19 - the back corners of the face brick may be clipped so that the backing brick fit diagonally into the notches thus provided (Fig. 8). This sort of concealed bond is weak and should be avoided.

Secondly, the face brick may be tied to the backing by laying metal strips or wires, supplied by any material dealer, in the bed joints of face and backing brick (Fig. 9). Although this method is frequently used and in a way answers the purpose, we do not regard it as the simplest and best.

We recommend the third method which is a natural bond, thoroughly workmanlike and sound. Every sixth or seventh course, pairs of headers are laid with a tight buttered, and hence invisible, joint alternating with the stretchers. As the joint between the headers is hardly seen, the two headers give the appearance of a stretcher, so that the effect of the Running or Stretcher Bond is maintained (See Fig. 31).

The face brick are laid up five or six courses in advance of the backing and the joints on the face of the wall are finished (See Fig. 57) as the work progresses. On outside exposed surfaces, the struck joint should be avoided, and particular care should be taken in seeing that all head or vertical joints are thoroughly filled with mortar from bottom to top. Each face course should be started so as to care for the bond or pattern chosen, as well as for the transverse structural bond. The backing is then laid in the usual way, always, so far as possible, breaking joint with the face brick. No attempt, except where strength is specially demanded, should be made to slush the thin space between the front and back tiers of brick, as this space helps to make the wall drier and warmer. Wherever the common brick backing is to be exposed, the joints must be neatly struck as in the basement wall. At the close of the day's work, face and backing should be brought to approximately the same level and covered to protect the work from the weather.

The brickwork should be stopped at the point where the first floor joists are to rest upon it, and care should be taken to have the top course perfectly level, so that the joists may be set without wedging or blocking. The joists set by the carpenter should have, at intervals of approximately six feet, wrought iron joist anchors solidly spiked to them, and extending into the wall. Great care should be exercised in placing these anchors as near the bottom of the joists as possible in order to lessen the strain on the brick wall, in case a fire causes the joists to drop.

For the same reason, the ends of all the joists, with or without anchors, should be beveled so that, in like conditions, the joists will readily fall out without injury to the wall. Fig. 10 illustrates the correct method of attaching the anchor to the joist. The dotted lines show how the joist would drop without damaging the wall. Fig. 11 shows the destructive effect caused by the anchor being placed at the top of the joist. The importance of these points cannot be emphasized too much as walls have had to be rebuilt which by proper framing construction would have stood intact. After the joists are placed, the brickwork is continued up between, and leaving a small "breathing" space around, them. The same method of joisting is followed at the upper floors.

If the lower part of a wall is thicker by a brick than the upper part, it should be carried up its full thickness nearly to the top of the joists Fire Stops where ft is stepped back to the inside face of the upper part, thus forming with the plastering a fire stop at the top of the joists, while a projection of a quarter brick length should always be provided as a fire stop at the bottom of the joists, as shown in Fig. 12. If the wall is the same thickness throughout, the brickwork should be corbeled out between - 20 - the joists two inches, the full height of the joists, to form a fire stop as in Fig. 13. The object of the fire stop is to block all possible passage of fire from the space between the joists to that between the furring strips on the wall, or the reverse. Without these fire stops, a fire originating in the floor could communicate with the furring space on the wall above, or originating in the furring space could communicate with the floor. With the stops, the fire is confined to certain spaces and is retarded instead of spreading. These corbels also serve the wholesome purpose of checking vermin of all kinds from passage through the floor and wall spaces.

Figs. 12 and 13 also show the proper way of placing the lath at the corner of the ceiling so as to take full advantage of the fire stops. The ceiling lath, usually placed first, should be started far enough away from the side walls so that when the side wall lath is placed tight, as it ought to be, against the underside of the floor joist, there will be space enough for the plaster to push through and form a key touching the bottom brick of the corbel. As the corbel by construction is necessarily the distance of a mortar joint above the bottom of the joists, the openings are thus completely sealed by the plaster key. In cheap speculative buildings, these fire stops are too often omitted or a pretext for them is resorted to by projecting only one brick at the top or bottom of the joists. This, however, is as good as no fire stop at all. Figs. 14 and 15 show the lath as they ought not to be placed and also how false corbeling leaves the passages really unstopped, thus defeating altogether the purpose of fire stops.

Masonry walls that are to be furred, sometimes have, as the work progresses, common wood laths laid in the joints of the brickwork on the inside face of the wall, about every seventh course, except over chimneys. The lath should be staggered so as to avoid two vertical lath joints in succession. These serve as nail holds for the furring strips as explained on page 24.

Where local requirements demand a 12-inch wall, the method of construction is the same as in the 8-inch wall, except that two rows or tiers of backing brick, instead of one, are carried up to the advanced level of the face brick, leaving the thin spaces between the tiers of brick open as the best way of securing a warmer and drier wall. Of course, in the case of piers and points in the wall that carry heavy loads, all interior joints should be well slushed with mortar for evident structural reasons.

Before the top of the wall is reached, the anchors for bolting down the roof plate should be placed and the brickwork carried up around them (Fig. 16). They should be made of half-inch bolts at least 12 inches long, with a tee or washer at the bottom and a nut and washer at the top, and should be set approximately every 6 feet along the wall. After the carpenter has placed the roof plate and before it is bolted down, the mason should bed with cement mortar under it.

When the wall is finally carried to the top and the roof rafters set, but before the roof boarding is in place, the mason should fill in between the roof rafters with one tier of brick as shown in Fig. 16. This is called nogging. Its purpose is to block effectually the openings between the roof rafters and prevent the wind from entering the walls and attic. This adds greatly to the comfort of the house in cold weather. In warm climates nogging will be found unnecessary.

The Chimney

While the chimney may be made one of the most charming and effective elements of the house design, its structural and practical necessities are its most striking features.

The proper construction, size, and height of chimneys are of the utmost importance both for the successful working - 21 - of the heating system and for the prevention of fires. The chimney may, though it need not be, a point of danger to the safety of the home. A little intelligent care in its construction will prove to be the best insurance. As a first precaution, all wood framing of floor and roof must be kept at least 2 inches away from the chimney and no other woodwork of any kind be projected into the brickwork surrounding the flues.

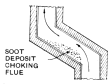

Chimneys should be tightly built of solid brick, have no openings except those required for the connection of the heating apparatus, and should always extend at least one foot above the highest point of the roof. In some cases, depending on local surroundings, it may be desirable to carry them somewhat higher. Those terminating below the level of the roof usually have poor draft because the wind, sweeping across or against the roof, may form eddies that drive down the chimney or check the natural rise of the smoke (Fig. 17).

The flues of chimneys should not start from the bottom of the foundation but only about a foot below the first smoke pipe openings, and should be lined with terra cotta flue lining their entire height. Care should be taken in setting flue linings to be sure that the joints are well cemented and, at the same time, that all spaces between the lining and brickwork are tightly filled with mortar. Any openings in the joints of the tile lining, or even of the brickwork, not only check the draft but are a fire menace. Cement plaster should not be substituted for the flue lining as it is likely to crack and fall off, thus leaving the flue in a dangerous condition. However, where flue linings are not available, a strong smooth cement plaster may be used, in which case the chimney wall should be at least 8 inches thick.

Modern heating plants necessitate accurate construction of chimneys, and most manufacturers of heating apparatus nowadays recommend the area and height of the flue necessary for their installations. The following table will prove useful in considering the question of heating plant or fireplace, by showing the dimensions of flue linings to be ordered when the required area is ascertained.

Table of Commercial Flue Linings

| Outside Dimensions | Actual Inside Area |

| 81/2" × 81/2" | 52 sq. in. |

| 81/2" × 13 " | 80 " " |

| 13 " × 13 " | 126 " " |

| 13 " × 18 " | 169 " " |

| 18 " × 18 " | 240 " " |

|

|

| Fig. 18. Chimney Withes | Fig. 19. Chimney Offset |

Where two or more flues are contained in one chimney, they should always be separated by a brick partition 4 inches thick, called a withe, and bonded to the outside brickwork as shown in Fig. 18. Chimneys should run as straight as possible from bottom to top, in order to secure better draft and facilitate cleaning. If, however, offsets are necessary from one story to another, they should be very gradual, never less than at an angle of 30° from the vertical. If abrupt offsets occur in flues, soot will soon be deposited, choking the flue and making cleaning almost impossible (Fig. 19). Care should be taken while the chimney is building that the bottom does not become filled with mortar or brick bats. At the bottom of the furnace flue in the basement, an iron cleanout door should be provided as a convenience for removing soot.

Chimneys erected on the interior of a building are apt to be more efficient because the warm air surrounding them facilitates the draft, while those located on the exterior naturally are somewhat affected by the cool air on the outside.

Angles, Bays, and Corners

All the houses represented in this book are designed without any obtuse or acute angled corners. If, however, you wish to erect a brick building with an angular corner or bay, specially shaped face brick for the purpose, called splay or octagon brick, may be obtained from the dealers or manufacturers. If for any reason these special shapes are not easily available, the angle - 22 - may be formed by the use of standard size brick. The method shown in Fig. 20 is used only on cheap work and should be discouraged, for it leaves ledges for the lodgment of snow and dirt, decreases the thickness of the wall, and besides is rather unsightly. The better method, as shown in Fig. 21, also has the objection of forming ledges for the lodgment of snow and dirt, but it makes a wall of full thickness, and has been used by some architects in a very artistic manner. The best method of all, for treating these corners, is shown in Fig. 22. Standard bricks are used with the minimum amount of cutting. Fig. 23 shows a method of laying brick at an acute angled corner. It is simple to lay up, there is little cutting of brick, and it presents a better looking corner than one with a sharp angle.

Openings

Window sills in brick buildings should be of brick or stone. Cement, unless pre-cast, is not well adapted for the purpose. Brick window sills are preferable to stone for, besides adding a charming touch to the building, they are inexpensive since they are of the same material as the wall and placed by the same workmen who lay up the wall, thus obviating the necessity of additional labor to place the heavy stone. Brick for sills should be laid on edge and pitched approximately at an incline of 1 inch in 6 to shed the water. They should also project at least an inch beyond the face of the wall to form a drip, and be laid in rich cement mortar composed of equal parts of cement and sand, with joints well filled and finished with a hard smooth surface. Door sills may be of wood, brick, or stone. In case of a stone sill, it should be exactly the height of either two or three courses of brick.

The window frames are set by the carpenter on top of the sill in a thin bed of mortar. When they are leveled, plumbed, and braced, the brickwork is carried up around the jambs or weight boxes, as shown in Fig. 24, always making certain that the corner or jamb of the brick opening is perfectly plumb. Great care should be taken to fill solid with mortar the spaces between the brickwork and the window frame, to stop the wind.

Stock Window Sizes

| Double Hung Sash, 13/8" Thick | |||

| Glass Size, D. S. | Lights[A] | Sash Size | Masonry Opening |

| 16" × 16" | 2 | 1'- 8" × 3'- 2" | 2'-0" × 3'- 6" |

| 16" × 26" | 2 | 1'- 8" × 4'-10" | 2'-0" × 5'- 2" |

| 22" × 20" | 2 | 2'- 2" × 3'-10" | 2'-6" × 4'- 2" |

| 28" × 26" | 2 | 2'- 8" × 4'-10" | 3'-0" × 5'- 2" |

| 30" × 24" | 2 | 2'-10" × 4'- 6" | 3'-2" × 4'-10" |

| 30" × 26" | 2 | 2'-10" × 4'-10" | 3'-2" × 5'- 2" |

| 34" × 16" | 2 | 3'- 2" × 3'- 2" | 3'-6" × 3'- 6" |

| 34" × 20" | 2 | 3'- 2" × 3'-10" | 3'-6" × 4'- 2" |

| 34" × 26" | 2 | 3'- 2" × 4'-10" | 3'-6" × 5'- 2" |

| 40" × 26" | 2 | 3'- 8" × 4'-10" | 4'-0" × 5'- 2" |

| 42" × 26" | 2 | 3'-10" × 4'-10" | 4'-2" × 5'- 2" |

| 52" × 26" | 2 | 4'- 8" × 4'-10" | 5'-0" × 5'- 2" |

| Basement Sash, 13/8" Thick | |||

| 20" × 14" | 2 | 2'- 0" × 1'- 5" | 2'-4" × 1'- 9" |

| 30" × 14" | 3 | 2'-10" × 1'- 5" | 3'-2" × 1'- 9" |

| 42" × 14" | 3 | 3'-10" × 1'- 5" | 4'-2" × 1'- 9" |

| Casement Sash, 13/8" or 13/4" Thick | |||

| 20" × 24" | 4 | 2'- 0" × 2'- 5" | 2'-4" × 2'- 9"[B] |

| 20" × 36" | 6 | 2'- 0" × 3'- 5" | 2'-4" × 3'- 9"[B] |

| 20" × 42" | 6 | 2'- 0" × 3'-11" | 2'-4" × 4'- 3"[B] |

| 20" × 48" | 8 | 2'- 0" × 4'- 5" | 2'-4" × 4'- 9"[B] |

| 20" × 56" | 8 | 2'- 0" × 5'- 1" | 2'-4" × 5'- 5"[B] |

[A] If divided lights are wanted, a special order will be necessary, the total glass size remaining the same.

[B] These heights are for outswinging casements; for inswinging casements, add 3/8" to the height of the dimensions given.

Stock Door Sizes[C]

| Exterior Doors 13/8" or 13/4" Thick | |

| 2'-8" × 6'-8" | 3'-0" × 6'-8" |

| 2'-8" × 7'-0" | 3'-0" × 7'-0" |

[C] Openings will be 4" wider and 23/4" higher than dimensions given.

Brick linear dimensions should, wherever possible, be calculated so as to reduce cutting of brick to a minimum, especially where openings, bays, chimneys, and the like are concerned. Our plans are drawn with this in view; and to facilitate readily obtaining sash and exterior door sizes, we would suggest that contractors, so far as possible, use stock dimensions taken from the accompanying tables which cover the vast majority of requirements. For each mullion between grouped, double-hung windows allow 6 inches, and between casement windows 2 inches. The stock window frames, which are essentially the same as those used in frame construction, require no more labor to set and brace than in case of frame walls. All that is necessary is to box them in to make a housing for the sash weights. After the brickwork is laid around the frame, a staff bead or brick mold is nailed to its outside face, fitting snugly up to the brickwork, adding if so desired a scribing bead.

Should local stock frames vary slightly from the dimensions given, or if a scribing bead is used in addition to the regular staff mold, the brickwork can easily be laid so as to take up the difference. In case the masonry opening is finished before the frames arrive on the job, great care should be taken to have them built the exact size of the frame ordered, always taking into consideration the 1 inch to 6 inches slope of the sill, and the scribing bead if used.

Opening Supports

The brickwork over all openings may be supported, either by a steel or wood lintel, or by a brick arch. Either the full thickness of the wall or the face brick only may be carried on a steel lintel or an arch. Lintels are rarely used in combination with semi-circular arches. When a steel lintel or an arch supports the face brick, the backing usually rests on a wooden lintel, set higher than the arch or else concealed by the frame. There should be a brick relieving arch above wooden lintels, spanning more than 3 feet, bearing on the wall beyond the ends of the lintel, so that the brickwork will not be weakened should the lintel be destroyed by fire (Fig. 28). The space between arch and lintel is filled with brick after the arch is built. Seasoned brickwork will support itself over the smaller spans.

For a steel lintel over a small opening, an angle is sufficient. If the interior wall surface is also to be of face brick, the lintel is made by placing two angles back to back, as the usual wood lintel in such a place would be unsightly. For openings up to 4 feet wide, a 4" × 3" or a 3" × 3" angle is sufficient; wider openings up to 5 feet would require a 3" × 5" angle. Over larger openings heavier sections of steel have to be used. Both steel and wood lintels are usually made 8 inches longer than the width of the opening.

The brick arches generally employed in small buildings are flat, segmental, or full semi-circular (Figs. 25-29). The segmental and semi-circular arches are usually best built of rowlock courses, their number depending upon the width of the opening. Flat brick arches over two feet wide should be supported by steel, the brick being usually set soldier fashion. As these brick are slightly inclined from the vertical, their end edges should be clipped to make the joints on the face of the arch come in a horizontal line, as in Fig. 26. In Fig. 25, the appearance of the arch face is not so workmanlike and neat because the brick have not been clipped along the line of the middle joints. For either type of arch, the brickwork both sides of the opening must be beveled in the form of skewbacks, to serve as beds for receiving the thrust of the arch as shown in the figures. If these arches are properly handled both as to design and execution, they add greatly to the appearance of the entire wall surface.

Various Methods of Furring

The inside of all exterior brick walls should be furred, except in climatic conditions where it has proved unnecessary, in order to form an air space between the brickwork and the plaster. This furring may be of wood, hollow tile, or metal. WoodThe first, which is ordinarily used, consists of 1" × 2" wooden strips placed vertically on the wall and spaced 16 inches on center (Fig. 24). The strips are either nailed to the lath which have been placed in the joints of the brickwork by the mason, or attached by driving the nails into the mortar joints. The carpenter, in placing the strips, should wedge behind them where necessary to make them plumb. The grounds and lath are placed directly on these strips. Hollow Tile Hollow tile furring is formed by splitting 3-inch or 4-inch "split furring" tile, which have been scored in manufacturing for this purpose, placing the webs against the brick wall, and anchoring them by driving ten-penny nails into the mortar joints over every third tile in every second course. The tile should be laid without mortar so as not to make a solid connection which would transmit moisture. This tile furring makes a good surface for interior plastering. MetalMetal furring is only used with metal lath and consists of small steel rods or other stiffening members either placed separately on the wall or as part of the metal lath.

Cleaning and Pointing

Not until after the plasterer has left the job should the face brick be cleaned or washed down. This is done with a 5 per cent muriatic acid solution or about one pint of acid to four gallons of water. A stronger solution is likely to do injury. Apply with a good scrubbing brush to remove all dirt and spattered mortar, and then rinse with clean water. While washing the wall, defects in joints should be pointed up.

The Hollow Brick Wall

A variation of solid brick construction is the so-called hollow or vaulted wall in which the face and common brick are separated by a two-inch air space and bonded together by metal ties laid in the mortar joints at proper intervals. This type of wall has been extensively used for many years, especially in the East.

Its friends claim that it is stiffer than a solid wall of the same amount of brick; that it offers a better insulation, by reason of the air space, against cold and dampness; and that therefore it saves the necessity of furring and fire stops on the interior wall surface. On the other hand, admitting the value of the air space and the consequent saving of furring, objection is made that the air space is apt to get filled with mortar and brick chips during construction; that the metal ties, unless heavily galvanized or dipped in asphaltum, rust out in a comparatively short time; and that it is not as strong a bearing wall as the solid wall of the same brick content. Mr. Arthur W. Joslin, a contractor and builder of Boston, whose extensive practice gives his judgment weight, says in summing up the pros and cons: "The 10-inch vaulted wall is strong enough for ordinary dwellings, even though the ties do rust out, unless it is built out of the poorest kind of brick with very poor mortar. In my opinion, a vaulted wall, if properly built, the vault not filled up with droppings, and provisions made for ventilating from the inside, is an ideal wall for dwelling house construction, but I would not recommend it for buildings for other purposes where there would be more or less of a dead load coming on the floors." On the matter of comparative costs, Mr. Joslin adds: "It is cheaper to build an 8-inch solid than a 10-inch vaulted wall, and slightly cheaper to build a 10-inch vaulted than a 12-inch solid wall."

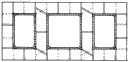

The accompanying drawing shows a cross section of this type of brick wall. Except in a few particulars, its construction does not differ essentially from that of the solid brick wall as already described.

A 12-inch brick foundation is wide enough for the 10-inch wall and a 16-inch foundation for the 14-inch wall. The metal ties, heavily galvanized or coated with asphaltum, should be placed about 18 inches apart at every fifth or sixth course and extend at least 2 inches into the mortar joints.

Fire stops are not needed, nor is furring, as the plaster may be laid directly on the brick. In order to preserve the chief merit of this type of brick wall, great care should be taken, during construction, that the 2-inch air space be not allowed to fill up with mortar and brick chips.

The local ordinances in some municipalities require thicker walls with hollow tile construction than where common brick backing is used, which affects the comparative cost of the buildings; but, where the total thickness may be kept the same as for solid brick, the cost is practically the same, with slight differences one way or the other in different communities. The tile used for backing may be either soft or hard burned, but never with an absorption of over 12 per cent, and are scored variously so that there may always be a good keying surface for plaster. These tile may be set with the hollow spaces or cells running either horizontally or vertically, as the case demands or the builder chooses.

Walls of this form of construction are built in much the same manner as walls with common brick backing, except that it is always desirable to use cement mortar with the tile to insure the needed strength of bond. The face brick are first carried up four or five courses and then the hollow tile units, of whatever thickness chosen, are laid up behind the brick, leaving an inch space between the tile and brick (Fig. 31). The tile are laid, with broken joint as in running bond, in a half-inch mortar bed. When the tile width is over 4 inches, the mortar should be spread only on the front and back edges of the tile, leaving a hollow space in the center. In the vertical joints only the front and back webs require mortar. If vertical tile are used all the webs should be well mortared, while the vertical joints are simply buttered.

Care must be taken that the space between the tile and brick does not get filled up with mortar, for this would defeat its purpose of serving as an insulation against moisture and cold. With this one-inch space between brick and tile open, furring and lathing are saved, as the plaster may be directly laid on the tile and the necessity of fire stops avoided.

At window and door openings, in case 4" × 5" × 12" or 8" × 5" × 12" horizontal tile are laid, either common brick or special half and full closure tile (Figs. 31 and 59) should be used, in order to close the openings at the end of the horizontal tile courses, thus making around the frames good joints which should be tightly filled with mortar. When the 12" × 12" tile are laid horizontal, those in the window and door jambs need simply be set vertical to serve as closures.

It will be found that an even number of tile does not always work out with the length of the wall or pier, leaving a space of a few inches. This space may be filled by cutting a tile or using pieces of tile slabs.

For houses of the character presented in this Manual, tile either 4, 6, or 8 inches wide may be used, depending on local ordinance or the choice of the owner. A 5-inch backing may be obtained by simply laying the 4" × 5" × 12" tile on the 5-inch edge. Both 4- and 8-inch widths are made 5" × 12" or 12" × 12" in height and length. The 6-inch width generally comes 12" × 12" in height and length, but may be obtained in the 5" × 12" size from certain manufacturers, if so desired.

The 5" × 12" tile in either width are laid horizontal, while the 12" × 12" tile in either width may be laid vertical or horizontal. Either method is satisfactory although, for heavy bearing walls, some builders prefer the vertical method on the ground that it gives a stronger bearing wall because the vertical webs directly bear on each other. If laid vertical, the top course of tile should be placed horizontal to give a good bed for the wall plate.

Four courses of standard size brick, provided a 3/8-inch mortar joint is used, will equal in height two 5" × 12" tile, making every fifth course a - 26 - bonding course (Fig. 31). And five courses of standard size brick, provided a 1/4-inch mortar joint is used, will equal in height one 12" × 12" tile, or if 1/2-inch joints are used, will equal in height 3 courses of 4" × 12" tile 5 inches wide, making every sixth course a bonding course. If wider mortar joints are desired, you can in the latter case make every fifth course a bonding course by using 12" × 12" vertical tile which you can order cut to any length required. But where either the 5" × 12" or the 12" × 12" tile are laid horizontal, the number of courses of face brick and the size of mortar joints cannot be changed.

The face brick are bonded to the tile backing (Fig. 31) precisely in the same manner as previously explained for common brick, double headers being used in case of Stretcher Bond and the headers, wherever required, in other bonds (See page 18). But as this wall is full 9 inches or more thick, the headers in the bonding courses leave recesses one inch or more deep at intervals on the inside face of the wall (Fig. 31). These if shallow, should be filled with plaster, containing a large amount of fibre, before the regular plastering is started; if deep, as when the 8-inch wide tile is used for backing, a stretcher course of common brick or brick-size hollow tile fills the space.

The chimney construction does not differ in any essential from that used for the solid brick wall, but we strongly urge the use of brick for the chimney, rather than tile or concrete blocks, as affording more reliable protection for the flue.

The window sills, door sills, and lintels are the same as in solid brick construction except that, preferably, instead of the wooden lintel supporting the backing, the lintel be made of hollow tile filled with cement and reinforced by one or more steel rods (Fig. 32). These tile lintels should be made on the ground by standing the tile on end for filling. When the concrete is set, they are ready to be lifted into place.

The story heights should be figured so that an exact number of whole tile may be used from the bottom of the joists on one floor to the bottom of those on the next floor, always allowing one-half inch for the bed joints. But where this is not possible, special tile slabs one inch thick, which may be had from the dealer, should be used to obtain the exact height required, so that an even and solid bearing may be formed for the floor joists. The wall plates for the roof construction are anchored in the same manner as in the solid brick wall, except that anchors should be 20 inches long; likewise, brick nogging should be placed between the roof rafters.

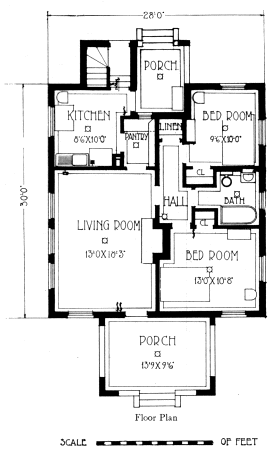

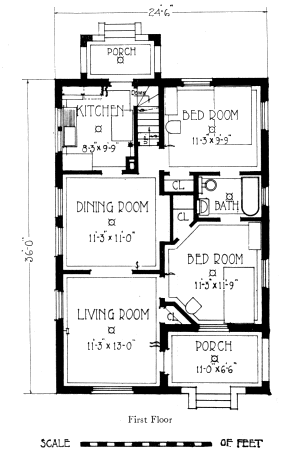

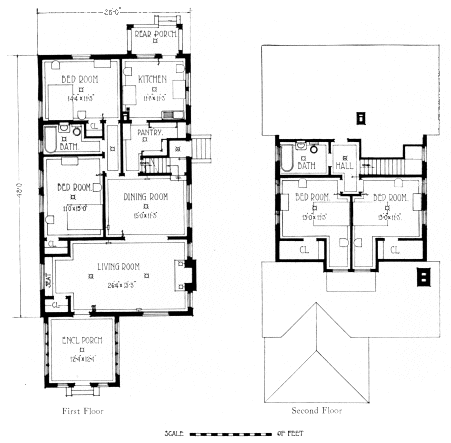

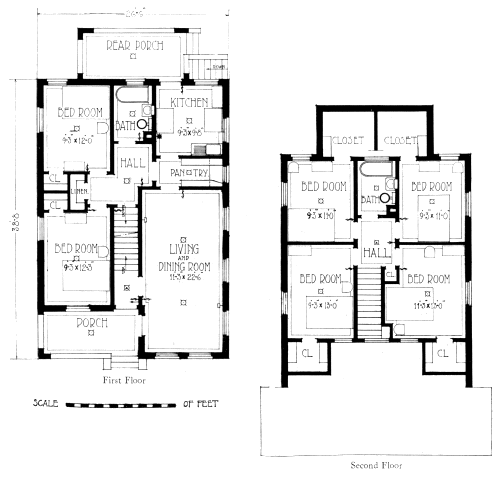

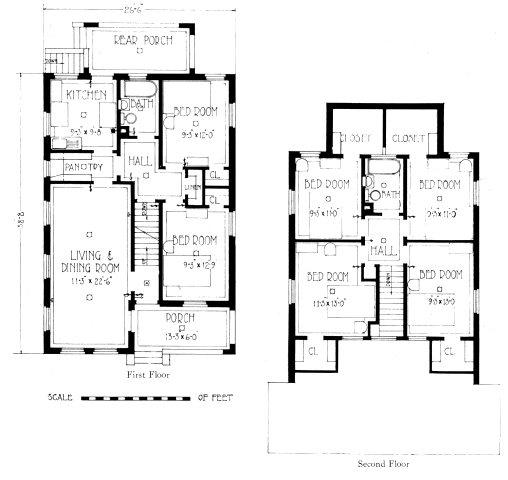

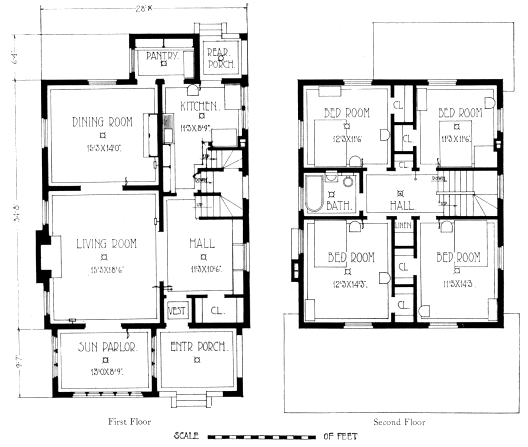

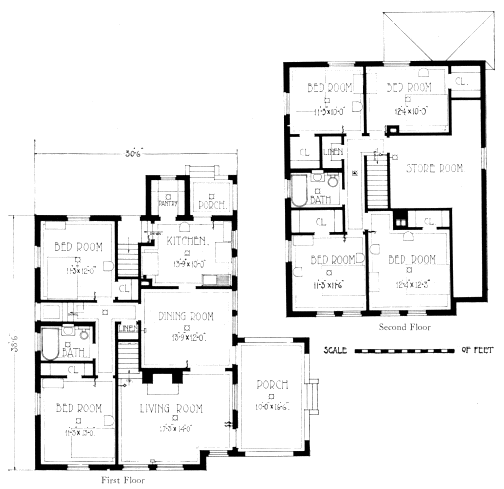

As in the case of the solid brick construction, when the plasterers have gone, the face brick should be cleaned down and pointed where necessary.