The Project Gutenberg eBook of Angel's Brother, by Eleanora H. Stooke

Title: Angel's Brother

Author: Eleanora H. Stooke

Illustrator: W. H. C. Groome

Release Date: April 3, 2023 [eBook #70455]

Language: English

Transcriber's note: Unusual and inconsistent spelling is as printed.

CHAPTER

I. THE MILKMAN'S LITTLE ACCOUNT

III. AN OVERSHADOWED HAPPINESS

V. HOW ANGEL MADE SEVERAL NEW ACQUAINTANCES

XV. COMMENCING THE SUMMER TERM

IT was a dull little sitting-room on the third floor of a dingy lodging-house, in an unfashionable London suburb. The pale rays of November sunshine peeping through the window panes enhanced the shabbiness of the apartment with its cheap, much-worn furniture, and ugly wall-paper, its pretentious mirror in a tarnished gilded frame above the mantel-piece, and the ill-chosen ornaments which were doubtless supposed to add attractiveness to the whole.

The sole occupant of the room, at present, was a little girl of about eleven years of age. Her name was Angelica Willis, but she was always called Angel. She was a slight, pale child, with a gentle, sweet-tempered face, which, if not exactly pretty, was very pleasing by reason of a pair of honest, grey eyes—true reflectors of every thought which crossed their owner's mind. Now, the grey eyes were misty and sad in expression, for Angel was thinking of her mother, who had died two years before, and recalling all that she had said the last time they had talked together. In imagination she could hear the dear, faltering voice murmuring feebly—

"You'll be loving and patient with Gerald, won't you, little daughter? You'll remember he's younger than you are, and be a good elder sister to him, won't you, dear?"

Gerald was Angel's brother, eighteen months her junior, and she had readily given her mother the desired promise. It was not difficult to be good to Gerald, for she loved him dearly; she had been in the habit of studying his wishes all her life; and she was capable of loving without selfishness, asking little in return. "Love feels no burden; thinks nothing a trouble," was true in her case.

Gerald had been the mother's favourite of the two children; but that knowledge had not caused Angel one jealous pang. She was too fond of her brother herself to begrudge him the first share of any one's affection; and now when the dear, indulgent mother was no longer there to wait upon him, she faithfully tried to fill her place, and was his willing slave, darning his socks, mending his clothes, helping him with his lessons evenings—in fact, being generally employed either by or for him in one way or another. Angel regarded herself in the light of a failure. Her father, an artist, 'had named her Angelica, after Angelica Kauffmann, and had fondly hoped that she would inherit his talent for painting, and follow in the footsteps of her namesake; he had anticipated that she would be endowed with what he called "the artistic temperament;" but Angel had proved somewhat of a disappointment. She had never evinced the least taste for drawing, whereas she had early taken to a needle and thimble, and had learnt to sew, and assist her mother with her household duties at an age when most children show distinct dislike to such domestic employments; but to "help mother" had been Angel's greatest pleasure.

Mrs. Willis had had rather a hard married life. She had married a man of undoubted abilities, but who had unhappily never succeeded in earning a sufficient income to adequately support his wife and children. She had believed in him, however, and had never complained because she had been obliged to work harder than any servant; only, once, Angel remembered, when something had been said about her lacking "the artistic temperament," her mother's face had brightened into a smile, and she had said, "Angel is my right hand. I do not know what I should do without my little daughter. Perhaps it is as well she has not 'the artistic temperament' after all!"

Later, when a woman grown, Angel recalled those words, and understood their meaning. But now, as she sat by the fireside, waiting for her brother's return from school, her thoughts turned from her dead mother to her father in his studio at the top of the house, where he was painting the great picture which he believed was to bring him fame and make his fortune, and wished she was not such a disappointment to him. It was indeed sad that she, an artist's daughter, should be denied "the artistic temperament!"

"It is not that I don't admire beautiful things," the little girl thought, "because I do. I love flowers, and I should like to live in a pretty house in the country, and—"

Her reflections were interrupted by a sharp knock at the door, which subsequently opened to admit the landlady of the house, Mrs. Steer—a portly, middle-aged woman, clad in a purple merino gown, the front width of which was plentifully besprinkled with grease spots.

"I'm come to tell you the milkman wants his little account settled," she said abruptly, but not unkindly, casting a solicitous glance at the child. "It ain't no good my speaking to your pa, as you well know, Miss Angel; for though he listens most politely, all I say goes in one of his ears and out the other."

"He forgets!" Angel cried hastily, her pale face flushing. "He is thinking so much about his great picture just at present."

"His great picture!" Mrs. Steer exclaimed, with an incredulous sniff.

"He will have plenty of money when he has sold it," Angel continued eagerly. "Oh, plenty! He was saying so only last night."

"But it isn't finished yet," Mrs. Steer remarked in matter-of-fact tones, "and goodness knows when it will be sold; and, meanwhile, there's the milkman wanting his little account settled. Will you speak to your pa, Miss Angel, and tell him what I say? Tell him the milkman positively refuses to supply you with any more milk till he's had his due."

"I'll be sure to tell father. But supposing he shouldn't have the money to pay? Will the milkman wait, do you think, if you tell him about the picture?" was the anxious inquiry.

"I can't say, Miss Angel. You remind your father of the account like a good child, and perhaps he'll find the money to pay it. As to that same picture, now, I suppose it's to make all your fortunes, eh?"

Angel nodded smilingly, meeting the landlady's half-pitying, half-sarcastic look with one so bright and confident that the woman's eyes fell, and she said kindly—

"Well, my dear, I only trust it may do all you expect. Then, I should hope your father will be in a position to send you to school."

"Oh yes; won't that be nice? I have never been to school because of the expense. Mother taught me all I know. It will be delightful when I do go to school. Think what a lot of friends Gerald has—all friends he has made at school—whilst I don't know any one!"

"Ah, it's a bit hard on you, my dear! Master Gerald gets all the cake! I mean," Mrs. Steer proceeded to explain, seeing the little girl's look of surprised inquiry, "that Master Gerald has the best of everything. There was never any thought of keeping him home from school because of the expense."

"Of course not! Father says boys must be educated, and Gerald's so clever! See what prizes he wins! No wonder father is proud of him! I wonder if I should ever win a prize? I am afraid not." And Angel shook her head dubiously.

"You won't forget to speak to your pa about that account, will you?" Mrs. Steer remarked after a brief pause. "The milkman's an honest, hardworking man, and can't afford to wait for his money any longer. As he said to me this morning, he's got to pay for the milk, and what's he to do if his customers don't pay him? It's hard on the man, and no mistake!"

"Oh, I am sure it is!" Angel cried distressfully. "I am certain father will pay him as soon as ever he can. I will speak to him about it directly!"

Mrs. Steer left the room, and went downstairs satisfied, whilst Angel sat still listening to her retreating footsteps, making up her mind that as she had a disagreeable task before her it had better be done at once. She hated reminding her father of his unpaid bills, though he always treated her with the utmost kindness; but he always expressed surprise that people should be in such a hurry for their money. Why could they not trust him? They would all be paid in due time.

Angel sighed as she went upstairs to her father's studio, where he spent most of his days. It was a large, low room at the top of the house, chosen by Mr. Willis on account of the fine light which shone through the north window. Though barely furnished, the room was artistically arranged with a view to appearances as well as comfort; an easel, supporting a large canvas, stood near the window, and a bright fire burnt in the grate, before which, reclining in a padded, wicker, lounge chair was Angel's father. He was a very young-looking man for his age, which was forty; his eyes were blue and smiling; his hair, which he wore a trifle longer than is usual nowadays, was light brown; and his figure slight and graceful.

"Well, Angel, my darling!" he exclaimed, as his little daughter entered. "Are you come to see how the picture is progressing? I have not done much to it to-day, for I've been obliged to get on with some illustrations for a children's book which were ordered weeks ago. The pot must be kept boiling, you know! I have been hard at work all the afternoon, but the light has failed, and I'm taking a rest."

Angel did not glance at the canvas on the easel; instead, she drew a stool to her father's side, and, sitting down, replied gravely—

"I am come to tell you about the milkman, father!"

"The milkman!" he repeated wonderingly. "What about him, my dear?"

"He says he will not let us have any more milk without we pay our bill! Have you any money, father? Can you pay him, do you think?"

"Pay him? Of course I can—at least, I suppose so! Is the man afraid I am going to cheat him? I had forgotten we were in his debt. Dear one, child, how like your mother you are growing! Well, well I am glad of that! But you must not get into the habit of worrying, for I cannot bear to see you looking anxious. Why should you trouble? We shall have plenty of money one of these days, if all's well."

"I know, I know!" Angel cried, lifting her grey eyes to her father's handsome face and smiling, for she implicitly believed what he said; "but what are we to do about the milkman's bill, dear father?"

He laughed at her persistency; and rising, went to a desk on a side table, and turned out the contents of a private drawer.

"There's not so much money here as I thought," he acknowledged ruefully, "but still, more than enough to pay the importunate milkman, I dare say. You can tell Mrs. Steer to let me have the account—I suppose I must have had it before, but I've not the least idea where I put it—and I'll settle it, at once. How pleased you look, child!"

She was very pleased, as her glowing face showed plainly. The household bills weighed upon her now as they had weighed upon her mother in the years gone by. Poor Mrs. Willis had been a "veritable Martha," as her husband had sometimes called her; he had never understood, though he had loved her dearly, why she had allowed herself to be troubled about many things.

Angel flew downstairs in search of Mrs. Steer, whom she met bearing a laden tray to one of her lodgers' rooms.

"Will you please let father have the milkman's account and he will pay it," the little girl said quickly; "he had forgotten about it."

"Oh, indeed!" responded Mrs. Steer. "Then I am glad you reminded him of it, miss. He shall have the account presently."

"I am going to make toast for tea," Angel explained, as she turned into her own sitting-room. "Dear me," she added to herself, "how very glad I am father is going to pay the milkman! I was so afraid he might not have money enough. It would be horrid to drink tea without milk; and I expect the poor man wants his money badly too. Oh, how I wish we never had to go into debt for any thing! Mother used to say she would be perfectly happy if she never owed any one a penny. Poor mother!"

Angel took a loaf of bread and a toasting fork from a cupboard in the sideboard, and proceeded carefully to cut some slices; then she knelt down on the hearth-rug, and commenced her toast making.

Presently Gerald returned from school, and, flinging his bag of books and his cap into one corner of the room, came to his sister's side. He was a fair, good-looking boy, very like his father, and tall for his age.

"What a jolly fire!" he exclaimed, as he stretched out his hands towards the glowing coals. "Make a nice lot of toast, Angel, for I'm as hungry as a hunter. What have you been doing all the afternoon?"

"Oh, much as usual," she answered in rather a depressed tone. "Darning your socks, and father's—and thinking."

"You're always thinking. I cannot imagine what you find to think about."

"About mother, mostly. I wonder if she knows how we are getting on, and how much we miss her. There are some things I should like her to know—but not all! I like to think she is very happy, never troubled or sorry, and—oh, I know she is really happy with God, but I keep on thinking, and wondering—"

"Well, don't!" he interposed affectionately. "You're moped, Angel, that's what you are."

"Perhaps I am," she acknowledged; "I've been alone all day, and I've been so dull; and—and the milkman wanted his account settled, and I had to speak to father about it."

"What a bother it is about money!" the boy exclaimed. "How I wish we were rich! I was going to ask father if he could let me have a shilling—I haven't a farthing of my last week's allowance left—do you think he'll let me have it?"

"He will if he can," Angel replied seriously, "but I'm afraid he is rather hard up at present. When his picture is finished—"

"Oh, what is the good of talking of that!" Gerald interrupted impatiently. "The picture may not sell for much, after all! I wish father was not an artist."

"Gerald!" the little girl exclaimed reproachfully, "how can you speak so? Mother used to say God had given father his wonderful talent for painting, and he must use it. Father is a genius. He will paint a beautiful picture which will be hung in the Royal Academy for every one to look at, and then some rich man will want to buy it, and offer father hundreds of pounds if he will sell it to him." Angel was allowing her imagination to run away with her, and in her excitement momentarily forgot the work in hand, so that she burnt a corner of the slice of bread she was toasting. This sobered her somewhat, and she continued more quietly—

"Then we shall pay all our bills, and live in a nicer place than this, and father will send me to school; and—oh, Gerald, it seems too wonderful to ever happen, doesn't it? Think what it would feel like to have money to pay for everything, and never to be in debt! How happy we should be!"

Her brother made no reply. His blue eyes were fixed thoughtfully on the glowing embers in the grate.

"Here comes father," he whispered presently; "will you ask him some time this evening if he can spare me a shilling? You will, won't you?"

And Angel promised she would, though she shrank sensitively from doing so, knowing how short Mr. Willis was of ready money; but it would have seemed unkind to refuse her brother's coaxing request.

ANGEL'S life was a very monotonous one. She spent most of her days alone whilst her brother was at school, and her father was occupied in his studio. Sometimes one of her father's artist friends would pause at the door of the sitting-room to inquire if Mr. Willis was at home; but no one ever stayed to exchange more than a few sentences with her, and she spent her time in reading, or dreaming, or looking out of the window on the miles of roofs stretching before her eyes when there was no mending for her father or brother to be done.

Occasionally Mrs. Steer took pity on the lonely child, and asked her to accompany her when she went out to do her shopping; and, on Saturday afternoons she now and then had a stroll with her brother; but Gerald usually spent his half-holidays with his school-friends, so that he had not much time to devote to his sister.

Angel liked Sunday the best day of the week, because she and Gerald always went to church with their father in the morning, and the studio was shut up altogether. Mr. Willis was very fond of his children, and thoroughly enjoyed the Sundays spent in their company, when he listened to Gerald's school experiences with great interest and amusement; but it never occurred to him to question his little daughter as to the way in which she spent her time, or to regret her neglected education and lack of congenial companions.

One cold afternoon towards the end of November, Angel, who had been on a shopping expedition with Mrs. Steer, returned to find her father had gone out, leaving a message to the effect that she must not wait tea for him. The little girl removed her out-door garments, and sat down with a book for company in the sitting-room to wait till her brother should come home from school. The book did not prove a very interesting one, so that when presently she heard a disturbance downstairs, she rose quickly, and, opening the door, stood on the threshold listening.

Mrs. Steer was apparently protesting against some one's entering the house, and was evidently both alarmed and angry. Actuated by curiosity, Angel slipped noiselessly downstairs till she reached the last flight, when she stopped short, keenly interested in the scene which met her gaze.

Mrs. Steer, with the maid-of-all-work of the establishment at her elbow, stood confronting a big, stout, red-faced man, who was standing by several enormous trunks, which he had evidently assisted the cabman to bring into the house, for he was mopping his brow with a red silk handkerchief, and appeared in a state of breathlessness.

"I never knew anything to equal this!" Mrs. Steer cried angrily, her eyes flashing with indignation. "To come into a respectable house without so much as asking leave, and take possession of the place! The impudence of it!"

"My good woman," said the stranger in a deep, pleasant voice, "I don't think I've made a mistake, have I? Mr. Willis lives here, doesn't he?"

"He does," Mrs. Steer allowed, "but—"

"I'm all right then! I know I shall be welcome! Pray tell your master—"

"My master!" Mrs. Steer interposed sharply. "What do you mean? This is not Mr. Willis' house. It's mine! I'm mistress here, and Mr. Willis and his children are my lodgers."

"Oh!" exclaimed the stranger. "Now I begin to understand the meaning of your indignation. I imagined this was my nephew's house—Mr. Willis is my nephew, by the way. My name is Bailey; I am—"

He paused abruptly, catching sight of the little girl standing on the stairs. Mrs. Steer followed his glance, and beckoned to Angel, who immediately came down and advanced towards the new-comer, her usually pale cheeks flushed with excitement.

"Did you want my father?" she asked. "He is out now, but he will be home before long. Is father really your nephew?"

"Yes, if you are John Willis' daughter," the big man replied. He caught her in his arms as he spoke, and kissed her heartily. "Why, my dear little girl," he cried, "you must be my great niece Angelica! I'm your Uncle Edward, just come home from Australia."

"Oh!" exclaimed Angel, rather breathlessly. "Are you really Uncle Edward? Oh, I know all about you! I've read your letters to father often! How very, very glad he will be to see you! But—what can I do? This is not our house—we only lodge here. Perhaps you had better come upstairs to our sitting-room and wait till father comes."

"Perhaps that would be the best plan," he replied. Then he glanced at his luggage, and from it to the landlady. "What can I do about it?" he inquired.

"It can remain where it is till Mr. Willis returns," Mrs. Steer responded, speaking a trifle more graciously than she had hitherto done. "I suppose it is all right if you are indeed Mr. Willis' uncle. And if you care to stay here, there's a big bedroom unoccupied at present which you might like to take."

The stranger nodded; then turned and followed Angel, who was leading the way upstairs. On entering the sitting-room, he glanced around him quickly ere he turned his attention to his companion.

"Do you know you are taking me on faith, my dear?" he asked, as he seated himself in the easy chair, by the fireplace, which she offered him, and scanned her face with smiling, kindly eyes.

"On faith?" Angel echoed. "But I know all about you, I do indeed! I have often heard father talk of Uncle Edward! You wanted him to go to Australia with you when he was a boy, didn't you?"

"Yes; but he preferred painting to sheep-farming!"

"Father loves painting. He is very clever! His pictures are beautiful."

The stranger allowed his glance to travel quickly around the room once more, after which he said musingly in a low tone, as though thinking aloud—

"He has not made his fortune?"

"No!" the little girl cried, "but he will some day; Mother used to say—Oh, did you know mother?"

"No, my dear, I never saw her. Are you like her in appearance? I think you must be, for you do not resemble your father in the least."

"I am like mother, I believe," Angel replied, a smile brightening her face. "I want to be like her. She was so sweet and good."

"Ah! Now, suppose you tell me about her."

Angel glanced doubtfully at the big man in the easy chair, but meeting an encouraging look in return, she complied.

"Things were so different before she died," she said confidentially; "we had a little house to ourselves, and she used to work so hard to keep everything nice and comfortable, and we were all so happy, though we were not any richer then than we are now. Then she fell ill—and died!" Angel drew a deep breath that sounded very like a sob. "Afterwards we came here and took these lodgings," she continued; "father has a studio at the top of the house, and he is painting a beautiful picture. He will show it to you to-morrow."

"What will he do with it? Sell it, I suppose?"

"Yes; he will send it to the Royal Academy for people to look at; I expect it will make a lot of money. I hope so, because there are so many things we want money for."

He smiled at her serious face; then looked thoughtfully into the fire. She watched him with great interest, and told herself she thought she would like him.

"Well, am I to be trusted?" he asked at length, turning to her quickly.

"Yes, I think so," she responded, blushing, and smiling.

"I hope so," he said gravely. "Who comes now?" he inquired as footsteps were heard outside the door. "Your father?"

"No—Gerald. Oh, Gerald, come here!" she cried, as her brother entered the room, and stopped short in great astonishment at sight of the stranger. "This is Uncle Edward, just come home from Australia!"

At first the boy was too surprised to say much, but as a rule he was not diffident, and soon he and Mr. Bailey were in the midst of an animated conversation.

Presently Mrs. Steer herself appeared with the tea-tray. She looked a little suspiciously at the visitor in the easy chair; but her face cleared as she listened to his pleasant voice; and when he laughed, she could not help smiling, for there was something so genial and hearty in the cheery sound.

Angel presided at the tea-table, and proved a good hostess, though she felt shy at first; but it was not very long before she was at her ease, and joining in the conversation without the slightest restraint. And all the while she was thinking how pleased her father would be when he returned home and found who had arrived in his absence. She had heard many stories of Uncle Edward—how kind he had been to her father when the latter had been a boy, and how he had wanted to give him a start in life in that far-off land across the seas.

The meal was nearly finished when Angel's sharp ears caught the sound of her father's familiar footsteps on the stairs; and a few seconds later he came into the room, and advanced towards the visitor with outstretched hands.

"Uncle Edward!" he cried joyfully. "How good it is to see you once more! Why did you not write to let me know you were coming?"

"I wanted to take you by surprise," Mr. Bailey replied, as he and his nephew shook hands heartily. "Why, John, you don't look much older than when I saw you last!"

"I cannot say the same of you," Mr. Willis said, "for you have grown stout, Uncle Edward."

"Oh, father!" exclaimed Angel disappointedly, "I believe you knew who was here when you came into the room."

"I did," he acknowledged. "I saw Mrs. Steer downstairs and she bade me hurry to see if you were entertaining an impostor or not. Uncle Edward, we would have given you a better welcome if we had known you were coming."

"I have been well entertained," Mr. Bailey declared, "and I have made a most excellent meal. Your children and I are friends already, John; Your daughter, I find, is the soul of hospitality!"

Angel, who was looking wonderfully animated, smiled as she met her father's eyes, whilst Mr. Bailey explained how his sudden arrival had met with Mrs. Steer's distinct disapproval.

"It never occurred to me that you lived in lodgings," he said, "so I dare say your landlady had every right to be angry when I invaded her premises!"

"I gave up housekeeping when my poor wife died," Mr. Willis remarked, with a sigh.

"Yes, yes," Mr. Bailey assented, "I understand. I think your landlady said something about having a bedroom to let. I had better interview her again—that is, if you'll allow me a share of your sitting-room, Angelica?"

"Oh yes! That will be nice, won't it, father? But you must please call me Angel—every one does. Angelica sounds so stiff and proper."

"Very well," Mr. Bailey agreed, "Angel is an exceedingly pretty name, in my opinion."

"We shall be delighted to have you for our guest, Uncle Edward," Mr. Willis said, a trifle dubiously; "but—you see what the place is like. Will you be comfortable here?"

"Far more comfortable than I should be at a grand hotel in the midst of strangers. Perhaps you think that because I'm an old bachelor I must be fidgety? Let me assure you I am not."

"You are greatly altered if you are! No, I did not think that," Mr. Willis returned. "Stay with us by all means, if you can make yourself happy here. Your company will be a real pleasure to me, and the children too."

"I have come back to England to make a home," Mr. Bailey remarked, looking thoughtful, "but I do not think it will be in London. Still, since you are willing, I will gladly remain here as your guest for the time."

Thus it was arranged. Mrs. Steer was glad to let the unoccupied bedroom, and her manner towards the stranger thawed when she found he was actually the person he professed to be; he further raised himself in her opinion when he stoutly refused to allow her and her maid-of-all-work to convey his luggage upstairs, but carried each box to his bedroom upon his own broad shoulders, declining even his nephew's help. Gerald was so taken up with their visitor that he forgot to learn his lessons till it was nearly bedtime, and then had to call Angel to his assistance. She wanted to listen to the conversation between her father and uncle, but, as usual, she lent her help to her brother when requested to do so, and laboriously worked his sums for him whilst he wrote out his French translation. By the time the lessons were finished and the books put away, it was nine o'clock, the hour at which the children generally went to bed.

"Good-night, Angel," Mr. Bailey said, as the little girl offered him her hand, and said "Good-night." "I shall not soon forget how you welcomed me this afternoon. God bless you, child!"

She looked at him seriously, surprised at the solemnity of his tone; but he was turning his attention to Gerald, and after kissing her father, she went away quietly to her own room.

Before she undressed for the night, she opened the window and listened to the roar of the great city, then lifted her eyes to the sky, where the stars were sparkling brightly, for the night was wonderfully clear. Her thoughts were all of the unexpected visitor, and she wondered if she would see much of him. She believed she would like him, for he possessed a countenance which inspired a feeling of trust. What would he think when he discovered their poverty? Was he rich himself? If so, she did not suppose he would remain with them very long.

The night air was chill, so presently she shut the window and commenced to undress. As she did so, she could not help wondering if Uncle Edward had noticed the shabbiness of her black serge gown; and she hoped, if he had, he would not blame her father for allowing her to wear such a dowdy garment, as Mrs. Steer had once done. The thought troubled her that any one should blame her father, who would willingly have supplied her slightest want if he had only had the money to do so. When she knelt down to say her prayers, however, all uneasy thoughts fled from her mind, for her mother had taught her from her earliest days, when she could only lisp in baby fashion, to carry her cares to God; and had impressed upon her that nothing was of too trifling a nature to lay before her Father in Heaven. The troubles she could not speak to human ears were poured out to Him who never fails to understand and administer to our needs, so that when Angel rose from her knees her mind was at ease; and her last waking thought was one of gladness for her father's sake, because she knew he loved his uncle well, that Mr. Bailey had come to their home.

DURING the week which followed Mr. Bailey's arrival Angel saw but little of him, for he was much engaged upon business of his own, and was in consequence away most of the days; but after a while he had more leisure time on his hands, and the weather being unsettled and chilly, was glad to be able to remain by the warm fireside. Thus one cold morning at the beginning of December found him seated in an easy chair near the fireplace reading the newspaper, whilst Angel pored over a story-book in which she was deeply interested.

For a long while silence prevailed, but by-and-by Mr. Bailey turned to his companion, and seeing how absorbed she was in her reading, observed her with closer scrutiny. Surely, he thought, it was unusual for a child of her years to be so very quiet. Had she no friends, he wondered, no companions of her own age? And why was it she did not go to school? Presently, becoming conscious his eyes were upon her, she glanced up, and met his earnest gaze with a look of inquiry.

"Is that a very interesting book?" he asked kindly, with his pleasant smile.

"Yes," she replied, "very. Mrs. Steer lent it to me."

"Do you do nothing but read all day long?" he questioned curiously. "Why, you are a regular little bookworm! But I think you spend too much time indoors! Little girls should have roses on their cheeks, and you have none. You are far too pale! Have you no young friends, my dear?"

"No, Uncle Edward; but I don't want young friends—at least sometimes I think I should like some, not many, just a few, you know! I have father, and Gerald, and—"

"But your father has his painting, so you really see but little of him; and Gerald is at school. Why, you must spend the greatest part of your days alone. How is it you don't go to school yourself?"

"I am going to school later on," she informed him hurriedly. "I—I don't mind much not going now. You mustn't think I do!"

He surveyed her in puzzled silence, passing his hand through his thick, grizzled hair, as she had noticed he had a trick of doing if he failed to understand the situation.

"Youth is the time for learning," he remarked at length, "but, of course, children do not realize that themselves. I remember when I was a schoolboy how I used to idle the precious hours away; and many a time since, I've regretted the opportunities I foolishly lost. Now, my brother—your grandfather, you understand, Angel—was quite different to me; he was always studying, and if he had lived long enough he would have made a mark as a clergyman, for he was a fine preacher, and popular with all who came in contact with him, besides being most zealous in the work he had chosen. But it was not to be, as you know, my dear; God took him away from his earthly labours when he was barely thirty years of age."

"Yes; father has often told me how his father died when he was a baby, and his mother did not live many years afterwards. It was very, very sad!"

"It was God's will," Mr. Bailey said reverently, "and He knows best, though we cannot always see His reasons for all He does; but it was a great loss for your father to be thus bereft of both parents at such an early age."

Angel had put down her book, and taken a chair close to Mr. Bailey's. Already she was beginning to find out that he was a most interesting companion.

"I know how good you were to father when he was a boy," she said gently, "and that you paid his school-bills, and gave him pocket-money, and—"

"Pooh, child! That was nothing. I was doing well in Australia and could well afford to do the little I did for him. I must confess, though, I was disappointed and vexed when I came home to England—more than twenty years ago it was now—and found your father so set upon being an artist. I would have liked him to join me in Australia, and he should then have had a partnership in my business."

"Father would not like to be anything but an artist," Angel replied. "He is a genius, and some day he will be famous!"

"Perhaps so, perhaps so! I am no judge of pictures myself, so I cannot say; but the road to fame is not an easy one, my dear."

"No, indeed!" the little girl agreed readily, with a mournful shake of her head. "We have always been poor," she proceeded with a sudden burst of confidence, "always! And it is not nice to be poor, and owe people money! Mother used to say our debts haunted her; she thought of them the first thing in the morning and the last thing at night! Oh, I ought not to tell you this, but—" And Angel broke off suddenly, a burning blush dying her face from brow to chin, whilst her grey eyes were suffused with tears.

Mr. Bailey laid a kind hand on her shoulder, and gave her a sympathetic pat; his ruddy face evinced much concern, but no surprise.

"Never mind, my dear," he said, and his voice sounded deeper than ever, "you're a brave little maid, and there are brighter days coming, I hope."

"I'm not brave at all," Angel responded, with a rather tearful smile, "but mother was. She never let father see when she was worried, because it troubled him if she was unhappy, and she never bothered him about things more than she could help."

"I should have liked to have known your mother," Mr. Bailey remarked thoughtfully, "I believe she and I would have been friends. I wish I had returned to England sooner; perhaps I might have made things easier for her, but as it is—" He paused abruptly for a moment, then asked, "Did you ever hear of a place called Wreyford, Angel?"

"No—yes—I am not certain. I seem to know the name."

"Wreyford is the town where your grandfather and I were born and bred, a quiet country town it was then; it may be altered now. Our home was called 'Haresdown House'; once it was our own property, but it was sold at my father's death. I've a mind to see the old place once again, and so I've determined to go and have a look at it, and ascertain if it is as desirable a residence as I used to consider it in my early years. What do you say to going with me, my dear?"

"Oh!" cried Angel in great astonishment, "do you mean it, Uncle Edward? Oh, I should like it! Is Wreyford near London?"

"No; it is a good distance away, in the west of England—in Somerset. I should like to have a look around the district, so we should be away several days. It would be a nice little trip for you, eh?"

"It would be delightful! Oh, I hope father will let me go! How kind of you, Uncle Edward! I have never been away from London all my life."

"Is that really so, Angel? Yes, you poor child! Well, I will tell your father what I propose doing, and hear what he has to say. I suppose he and your brother will be able to get on without you for a short while?"

He spoke banteringly, but Angel took his remark seriously, and answered with great gravity—

"I don't know, but I should think they might. What will Gerald say when he knows where I am going? He will want to go instead of me." And a slight shadow dimmed the happiness of her face.

"He will not be so selfish, I should hope," Mr. Bailey returned, "and, besides, he has his duties at school to attend to. No, if you cannot go with me, my dear, I most certainly shall not dream of taking Gerald."

"And you think we shall be away several days, Uncle Edward?"

"Most probably. If the weather is fine, and not too cold, we need not hurry over our trip. Wreyford is beautifully situated, and has a mild climate. How strange it will be going back after so many years."

Angel was silent. In reality she was in a great state of excitement, but she sat with her hands clasped in her lap, and her eyes fastened on the shabby carpet, whilst she thought of the treat in store for her. The idea of a change of scene had all the charm of novelty. How wonderful to think that a month ago she had not known Uncle Edward! Already she trusted him implicitly, and felt he was her sincere friend.

By-and-by they went upstairs to the studio and unfolded their plans to her father. Mr. Willis listened good-humouredly; the prospect of his uncle and Angel going for a holiday together appeared to amuse him.

"Why, what makes you want to take Angel, Uncle Edward?" he exclaimed. "Oh, I don't mind her going in the least, but—"

"The change will do her good," Mr. Bailey interposed hastily; "she leads a dull life, I fear, with no companions of her own age. Give her into my charge for a few days; I will take good care of her."

"That I am sure you will!" Mr. Willis agreed readily. "Well, child," he proceeded, laying his hand on his little daughter's shoulder, "do you want to desert me?"

"No, father; but if you think you can spare me I should so like to go with Uncle Edward," she answered, lifting a pair of wistful eyes to his face. "I should like to see the house where grandfather lived when he was a boy, and—oh, it would be such a treat altogether! Do say I may go," she added coaxingly.

"Well, then, I suppose I must. Uncle Edward is right, you have a dull life; but it will be different when I send you to school."

"Oh yes," she agreed happily, "you must not think I mind being dull. Of course, I can't help feeling lonely when you are at work up here and Gerald is at school. Have you ever been to Wreyford, father?"

"No, my dear, but perhaps I may go there some day. I, too, should like to see the place where my ancestors lived. You must keep your eyes open so as to be able to tell me all about it."

"Indeed I will. To think I am really going into the country! It seems too wonderful to be true! I wonder what Gerald will think!"

Angel was soon to know what Gerald thought, for when he returned from school she naturally greeted him with the news of her impending journey. She Was alone in the sitting-room when she heard him come running upstairs, whistling softly the while and as he entered she cried excitedly—

"Oh, Gerald! Guess where I am going! But no—you never will. Uncle Edward is going to take me to Wreyford with him—that's where grandfather was born, you know—and we shall be away several days."

"Uncle Edward is going to take you with him!" he exclaimed. "Nonsense, Angel! You're joking!"

"Indeed I am not! It's quite true! Father says I may go. Won't it be nice for me? Wreyford is in the country—in Somerset." Angel paused suddenly seeing a cloud upon her brother's brow. "I shan't be away long," she continued, "only a few days. And you won't miss me much, because you will be at school."

Gerald, who was reflecting that he would have to do his lessons without assistance during his sister's absence, made no reply. He looked rather sulky, wondering why Uncle Edward wanted Angel's company, and a feeling of jealousy crept into his heart, for he would have much liked to go with Mr. Bailey to Wreyford himself.

"Aren't you glad, Gerald?" his sister asked, a trifle wistfully. "You don't mind because we are not both going, do you?"

"Of course not!" he snapped irritably. "But I can't think how you got around Uncle Edward to make him ask you instead of me," he added with a frown.

"I didn't get around him at all," she protested indignantly. "What do you mean? He said if I could not go he should not dream of taking you." Then, noting that he was considerably taken aback at this piece of information, she was regretful she had repeated Mr. Bailey's words, and said quickly, "I am so sorry you are not going too, Gerald."

"I don't believe you are!" he retorted. "Girls always get the best of everything," he went on in grumbling tones. "See what easy times you have when I'm working hard at school all day long!"

"I would far rather be at school," she assured him eagerly; but he only shook his head and declined to believe her statement.

She was disappointed, and hurt that her brother evinced no joy at the thought of the pleasant trip she was anticipating with such delight; but she reminded herself that it was quite natural he should be vexed at having to remain at home, and tried not to let his lack of sympathy damp her spirits. Perhaps Gerald was rather ashamed that he had allowed his sister a glimpse of the real state of his feelings, for he was more than usually gracious to her during the evening which followed; and after his lessons were finished, challenged her to a game of draughts, and showed no ill-humour, as he frequently did when she beat him.

Then the projected journey to Wreyford was discussed again, and Mr. Bailey waxed eloquent as he talked of his early home, and told amusing anecdotes of his young days, when he and the children's grandfather had been mischievous spirited boys.

"I hope the place is not much altered," he said, "but I suppose I must expect to find it is. I sometimes think I should like to end my days in my native town."

"Do you mean you contemplate living there?" Mr. Willis asked, regarding his uncle with some surprise. "From what I have heard of Wreyford, I imagine it is a very quiet place."

"I do not care for bustle," Mr. Bailey answered; "but I shall see, I shall see! I have not yet settled what my plans for the future will be. To-morrow, Angel, you and I must decide when we shall go."

Angel met his kindly glance with a smile which faded, however, the instant she turned her eyes to her brother's face. Gerald was looking cross and envious again, as though he begrudged the pleasure in store for her, and her happiness was overshadowed immediately. She felt she would rather remain at home, and let him take her place; but she did not like to suggest the change after Mr. Bailey's decisive remark to the effect that he should not take Gerald with him anyway.

Later in the evening she found an opportunity of speaking to her brother without being overheard by her father or uncle.

"Gerald," she whispered, "if you would rather, I will not go to Wreyford with Uncle Edward, I will stay at home."

"What would be the good of that?" he asked impatiently, never guessing what a sacrifice it was she was willing to make. "I shan't go if you don't. Oh, don't make a fuss Angel!"

She had no intention of doing that, but she felt as though Gerald had spoilt her happiness. She told herself he was selfish and unkind, and shed a few bitter tears after she was in bed at the remembrance of his manner and words; then her heart softened towards him, and she determined not to be resentful to him the following day. Had she not solemnly promised her dying mother to be loving and patient with Gerald? Angel had a very faithful heart, and she meant to keep her word.

WREYFORD was an old-fashioned market-town with one principal street, called Fore Street, where private houses intermingled with shops; and the eyes of passers-by were refreshed by glimpses of pretty gardens, a-bloom with flowers in summer-time, stretching in front of roomy, comfortable-looking, stuccoed dwellings.

The town lay in a valley between two sheltering hills, and the gardens at the back of many of the houses stretched to the river—the Wrey—which, as it flowed by Wreyford, was little more than a sparkling stream, though some ten miles further on its course it broadened considerably, and was navigable for small boats.

The town of Wreyford was flat, but it was impossible to walk far beyond in any direction without ascending a hill, when one was fully repaid by the extensive and beautiful views to be seen, look which way one would, of rich pastures and woods, the silvery river winding serpent-like along, and far in the distance the Exmoor hills.

On the summit of one of the hills, called Haresdown Hill, overlooking the town, stood the parish church—a grey, weather-beaten edifice with a high tower inhabited by hundreds of jackdaws, and bats innumerable; and encircled by a churchyard where many crumbling tombstones, with almost obliterated inscriptions, testified to the antiquity of the burying-ground. The church was nearly a mile from the town, and the winding road, which led to it up the hill, was a favourite walk of Wreyford people, who were justly proud of the fine old building standing in solitary stateliness, keeping watch, as it were, over the town beneath. It had been built and endowed in the twelfth century by a famous follower of Richard I, as a thank-offering to God for his safe return from the Holy Land, where he had been engaged in the crusades; his tomb was on the north side of the church, within an arch with full-size effigies of himself and his wife in marble.

The old church could have told many an exciting tale of the years it had seen. Cromwell's soldiery had battered in the great west door, and had slain the parish clerk, who had vainly endeavoured to defend the house of God. At the entrance of the porch was a stone let into the pavement to the memory of the brave old man, which told that—

"Ezekiel Hassal, 46 years clark heere, dyed 19th February, 1631."

It was at this particular stone that two little girls were looking one fine Saturday afternoon in December as they sat side by side on a bench within the church porch. They were Dinah and Dora Mickle, daughters of Mr. Jabez Mickle, the owner of the best practice as a solicitor in Wreyford. Dinah, the elder of the two children, was twelve years old, and she was in charge of Dora, who was only eight; they were resting awhile before going home, having been for a long walk.

The story of Ezekiel Hassal's fate always had a great attraction for little Dora, and she had insisted upon hearing it again from Dinah's lips, although she knew it quite well, and shuddered as she listened. She was a sensitive, imaginative child, and could easily picture Cromwell's fierce soldiery ascending the green slope of the hill, the figure of the old parish clerk stationed before the door of the church he loved so well, and the tragedy which had followed.

"Oh, Dinah!" she cried, "mustn't it have been a terrible, terrible sight! Are you not glad we did not live in those days?"

"Yes," Dinah returned, "because I shouldn't have known whether to side with the king or Cromwell."

"Oh, Dinah! Why, they cut off the poor king's head!" Dora exclaimed, almost in tears at the very thought. "That could not have been right, could it?"

"No," Dinah agreed, knitting her brows in a puzzled fashion. She had been studying the history of the troubles between King Charles I and his Parliament, and her sympathies were divided. "But don't let us speak of poor Ezekiel Hassal any more," she continued, conscious of the cloud of sadness on her little sister's face, "he died long, long ago, and thinking of him only makes you low-spirited."

"He was a hero!" the younger child declared with sparkling eyes. "I heard father say so to the boys the other day."

Dinah nodded, but did not prolong the conversation; instead, she rose, and, followed by her sister, walked through the churchyard, out by the lych-gate, and down the winding path towards the town.

The sisters were very unlike in appearance and disposition. Dinah, who was a tall, well-grown girl, had a fresh, rosy face, a pair of dark blue eyes which shone with a steady light, and a firm mouth and chin. She was a sweet-natured child, gifted with an equable temper, and a fund of commonsense unusual at her age, and was a general favourite at home, as well as at the day-school which she attended. Dora was fairer, and much slighter than her sister; her eyes were a lighter blue; her hair golden brown; and her whole appearance was so fragile that people generally formed the idea she was delicate, which was certainly not the case. She was very impulsive, and easily led through her affections, making other folks' troubles her own, the result of an intensely sympathetic nature.

As the sisters descended the hill their way led past an old house with cob walls and a thatched roof, standing in its own grounds, the entrance to which was almost hidden from sight by shrubs so overgrown that one would have said they had not been trimmed for years. Usually a board was to be seen in the midst of a mass of evergreens, announcing to passers-by that the house was to be sold or let; but to-day the board had disappeared, and as Dinah noted the fact she paused involuntarily, with an exclamation of intense surprise.

"Why, Dora!" she cried, "I do believe 'Haresdown House' is let! Now, I wonder who can have taken it!"

"Do you think it can be taken?" Dora questioned, looking quite excited, for no one had inhabited "Haresdown House" during her eight years of life. "Who is there in Wreyford that would live here? Every one says what a dull house it is!"

"I believe it is let because the board has been taken down," Dinah replied gravely. "However, we shall soon hear if it is; perhaps father may know. Come, it must be getting near teatime; we had better hurry home."

The Mickle family lived in a high, old-fashioned house in Fore Street. The house itself stood back from the street, and had a trim flower garden before it, and a kitchen garden at the back which reached to the river.

The chief rooms on the ground floor were the lawyer's offices; but the house being three stories high, the family was not cramped for space. The dining-room overlooked the street, and was a pleasant, airy apartment with a comfortable, homely look about it, in spite of its well-worn Brussels carpet, and rather shabby, leather-covered furniture; there were a few good oil-paintings on the walls, some handsome bronze ornaments on the mantel-piece, and a bowl of chrysanthemums in the centre of the table in the middle of the room.

On this particular December afternoon the room had two occupants—Mrs. Mickle, who was seated near the window, bending over some plain needlework, and her elder son, Gilbert, a boy of nearly sixteen, who reclined on a sofa drawn near the fire.

Gilbert Mickle was a cripple, and could only walk with the help of crutches; but he was not in the least an invalid, enjoying really robust health. He was a very handsome boy, though the expression of his face was usually not a pleasant one, for he possessed an obstinate, cantankerous temper, which had already left its traces in two deep lines between his brows. One of his school-fellows had once declared in his hearing that his temper was as crooked as his legs, and he had been stung into a perfect fury of passion by the remark, conscious that every one recognized its truth, and had dealt the offender such a series of vicious blows with one of his crutches that he had cried for mercy and let him alone for the future.

With his brother Tom, who was a year his junior, Gilbert attended the Wreyford Grammar School; but, whereas the younger brother was universally popular, Gilbert was generally disliked, and feared, by reason of the cutting tongue he never hesitated to use at another's expense.

"I suppose Tom will be back from the football match soon," he remarked at length, as he flung aside the book he had been reading, and yawned idly. "I wonder if the Grammar School will be beaten. I don't care if it is."

"Oh, my dear," Mrs. Mickle remonstrated gently, "think how disappointed Tom will be if his side loses."

"It will do Tom good to be on the losing side for once, mother. The Grammar School has had all the luck so far this season, and, really, to hear Tom talk you'd think it was mostly owing to him. Conceited young cub! He wants to be put under a bit!"

Mrs. Mickle laughed, then sighed. Certainly Tom was rather an important individual in his own estimation; but the manner in which his brother remarked the fact was not pleasant.

"You should have gone to watch the football match," she said, "it would have been better for you than lying there all the afternoon."

"Yes. It does me good to hear strangers say, 'Who is that lame boy on crutches?' or, 'What a pity he is a cripple!' It makes me simply furious. I overheard some one remark once that my legs were exactly like a spider's when I moved. I prefer to remain at home in peace and quietness."

Mrs. Mickle bent her head over her work more to hide the tears in her eyes than because the light was fading and preventing her seeing clearly. The sarcastic bitterness in her son's voice cut her to the heart. Of her four children, Gilbert was the only one who had ever given her much anxious thought; he had caused her many a sleepless night, for his had always been a most difficult character to understand.

"I am sure you dwell too much upon your infirmity, my dear," she said presently. "You are too self-conscious, too wrapped up in yourself. Instead of always thinking of what people are saying about you, and regretting the cross God has given you to bear, do you not think it would be better and wiser to dwell on all He has blessed you with? Yes, I mean what I say," she continued, as he made an impatient gesture, "you are far in advance of most boys of your age in intellect, and if you use the talents with which God has endowed you, you may have many opportunities of doing good in the world, and benefiting your fellow-men."

"I don't know that I want to benefit my fellow-men particularly. I may have brains, but what are brains in comparison to legs? If my legs were straight and strong, I should be perfectly content."

"But as they are not, dear Gilbert, don't you think you ought to make the best of them?"

"Oh, mother, it's all very fine for you to talk, but you don't understand."

"I think I do, my dear; and if I do not, you know there is One who understands perfectly."

Gilbert knew whom his mother meant, but he vouchsafed no reply. He reached for his crutches, and, rising from the sofa, slowly swung himself towards the window, where he stood by his mother's chair, gazing out into the street. Mrs. Mickle proceeded with her needlework in silence, but presently she raised her eyes to her son's face, and he turned and met her gaze.

"I'm a wretch to make you look like that," he said repentantly, as he noticed her troubled countenance, and bent to kiss her, for he was really deeply attached to his mother; "it is too bad of me to be so disagreeable. Why, here come Tom and the girls!" And flinging upon the window he shouted to his brother, and asked the result of the football match.

"The Grammar School won," he reported to his mother, as he shut the window.

"And you are glad!" Mrs. Mickle exclaimed as she noticed the gratified expression on his face.

"Well, I suppose I am really. Here they come tumbling up the stairs!"

The next moment the door was flung open, and Tom, followed by his sisters, hurried into the room.

"Two goals and a try to nil!" shouted the former. "I say, Gilbert, old boy, I wish you'd been there to see us lick them!"

"Oh, mother! Oh, Gilbert!" cried Dora, "'Haresdown House' is let!"

"Yes, or we suppose so; at any rate, the board has been taken down," Dinah hastened to explain.

"It is let," Gilbert said calmly, smiling in a superior manner at his sisters' excitement; "it has been taken by an elderly gentleman called Bailey. The house belonged to his father many years ago, and he had a fancy to purchase it. Mr. Bailey has lately returned from Australia."

"Where did you get your information?" Mrs. Mickle inquired.

"From Grylls, the chemist. Mr. Bailey's lodging at his house. You know, Grylls has lived in Wreyford all his life, so he knew Mr. Bailey before he went to Australia as a boy. Grylls says he shouldn't be surprised to hear he has made a big fortune, for when he found out 'Haresdown House' was to be sold or let he bought it at once. He has been in Wreyford for the last week with a little girl—a niece of his. I wonder you haven't noticed him about the place—a big man, with a jolly-looking red face."

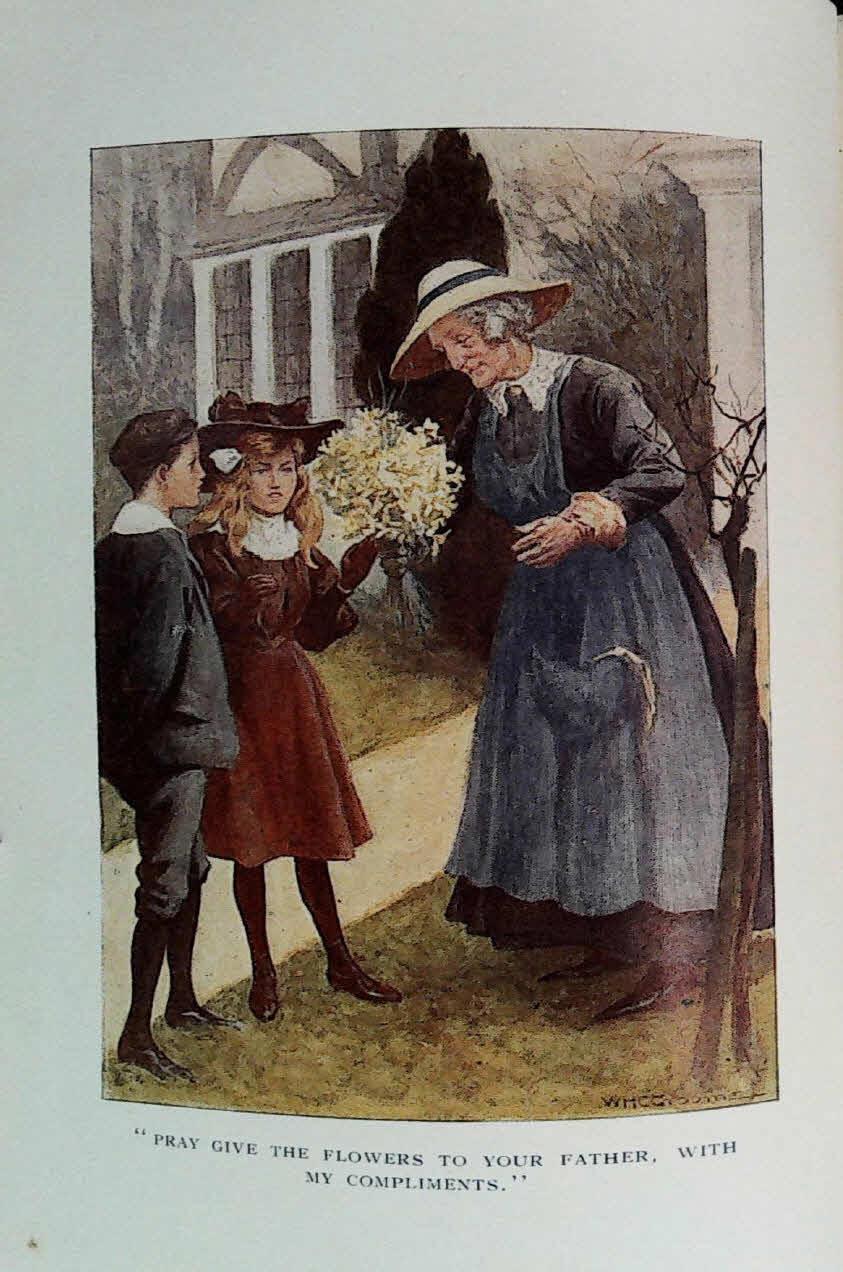

"Oh!" cried Dora, "I believe I met him in the street yesterday, and the little girl too. I saw they were strangers. She was all in black, and—why, how extraordinary! Mother! Dinah! Boys! There they are!"

Every one looked out of the window at the very instant that three figures reached the garden gate—a tall, thin, clean-shaven man, who was no other than Mr. Mickle, in company with Mr. Bailey and Angel.

"Fancy father's knowing them!" cried Dinah. "Oh, he is actually bringing them in! Do you imagine they will come up here, or will he take them into his office? Do you think they would come on business on a Saturday afternoon?"

"Perhaps father has something to do with the transfer of the property Mr. Bailey has bought," Gilbert suggested sagely.

"Very likely," his mother agreed.

At that point Mr. Mickle's voice from below was heard calling for Dinah, and she hastened to obey the summons. In a very few minutes she returned to the dining-room, followed by a pale-faced, shy-looking little girl, whom she introduced to her mother, simply saying—

"Mother, this is the Australian gentleman's niece. Father says she is to stay with us, and we are to amuse her until he has finished his business with her uncle, whom he is going to bring upstairs to tea presently."

IT was a trying experience for Angel to be the object of interest to five pairs of strange eyes, and she was seized with a perfect panic of shyness as she gave one hasty glance around the room, wishing she had been allowed to wait for Mr. Bailey downstairs. She blushed painfully, conscious of the dead silence which had fallen upon the group by the window; then she felt her hand taken in a reassuring clasp, whilst a kind voice said cordially—

"I am very pleased to see you, my dear. I am Mrs. Mickle. Sit down in this chair by my side. That's right! Let me introduce you to my children. This is Dinah. She must be about your age; and this is my baby, Dora. The boys are Gilbert and Tom. Now you know us all!"

Angel shook hands with each member of the family in turn, not knowing quite what to say, and hoping her silence did not appear ungracious.

"If you will tell us your name, we shall start our acquaintance on a proper footing," Mrs. Mickle proceeded, pitying her visitor's evident embarrassment, and longing to put her at her ease.

"I am called Angelica Willis," Angel answered, "but every one calls me Angel."

"May we call you Angel, too?"

"Oh, please do! Angelica is such a long name, but father wished me to be called it after Angelica Kauffmann, the painter. Father is an artist."

"I understand," Mrs. Mickle said, grasping the situation at once; "you will be an artist yourself, perhaps, when you grow up?"

"No," Angel replied, shaking her head regretfully, "I am afraid not! I am certain not! I cannot draw even a straight line. It is a great pity, but I have not the artistic temperament."

She spoke so seriously that Mrs. Mickle refrained from smiling; but Tom began to giggle, at which sound Angel shot a quick glance at him, and saw that he was making merry at her expense. She was not conscious of having said anything funny, and had yet to learn that very little was sufficient to amuse Tom Mickle. Gilbert was still standing by the window, looking out, listening to the conversation, though taking no part in it.

"Are you going to live at Haresdown House with Mr. Bailey?" Dinah asked hurriedly, seeing that Angel had noticed Tom was laughing at her.

"Oh no!" was the response. "I live in London with my father and brother."

"Mr. Bailey is your uncle, isn't he?"

"My great-uncle. He was born at Haresdown House sixty-five years ago, and he says he hopes to end his days there. He has been so kind to me, giving me this nice holiday in the country! I was never in the country before!"

"Never in the country before!" Dora echoed, opening her blue eyes very wide.

"If that is the case, I am sure you are enjoying your stay at Wreyford," Mrs. Mickle remarked. "You have been here several days, have you not?"

"Just a week. I think it is a beautiful place; I never imagined it would be so lovely! You have sunshine every day!"

"It is exceptionally fine weather for the season, but we rarely experience very severe winters here. So you have a father and brother in London? Have you no sisters?"

"No; there are only father, and Gerald, and me!" Angel hesitated, and glanced down over her black frock; then she raised her eyes to Mrs. Mickle's face, and caught a look so full of motherly tenderness and sympathy that her heart gave a throb half of pleasure, half of pain, and she added simply, "My mother died two years ago."

"Oh, my dear!" cried Mrs. Mickle; and she gave her little visitor a warm, impulsive kiss, which was returned with goodwill. "You are going to have tea with us presently," she continued, "so you had better go upstairs with the girls, and remove your hat and jacket. Dear me, it is more than half-past four, and we have tea at five."

"Come!" said Dora, taking Angel by the hand, and leading her from the room, whilst Dinah followed close behind. "We have a room between us," she explained; "I expect it's rather in a muddle because we had not time to tidy it before we went for our walk."

"Perhaps you'll excuse it?" Dinah asked politely.

"Oh yes!" Angel responded, "of course I will!"

It was impossible to be shy with the sisters long. They asked her dozens of questions, which she answered readily; and found herself putting questions to them in return. She looked around their bedroom with interested eyes—at the two little white beds side by side, the pretty pictures on the walls, and the ornaments, which she was told had been mostly birthday presents—and openly admired everything she saw. Dinah and Dora evidently had great pride in their room; they informed her they made the beds themselves, and took it in turns to do the dusting. "Jane, that is our housemaid, has so much work that mother likes us to help her all we can," Dinah said in her matter-of-fact way; "there's plenty to do in this house, there always is where there are boys about. Tom is dreadfully untidy, and always forgets to wipe his boots thoroughly before he comes upstairs, and brings such a lot of grit into the place. Is your brother like that?"

"Yes," Angel answered, smiling, "and Mrs. Steer does get so cross with him!"

"Who is Mrs. Steer?" Dora inquired.

"Our landlady. We live in lodgings, not in a house of our own."

"Oh, I should not like that at all!" Dora cried.

"Because you are not accustomed to lodgings," Dinah put in quickly. She turned to Angel and asked, "Is your brother older than you are?"

"No, younger," Angel replied. "He is very clever, and has such a lot of friends. Every one likes Gerald."

Once set going on her favourite topic of conversation, her brother, she found a great deal to say. She told how many prizes he had won at school, and how proud her father was of him.

"Did you ever win a prize?" Dora asked, much interested.

"No," Angel acknowledged, her face, which had been bright and animated, becoming suddenly overclouded; "I do not go to school!"

"And yet you are older than your brother!" Dinah exclaimed in accents of surprise.

"Yes," Angel answered; and became suddenly silent.

The sisters saw that for some reason or other she did not wish to be questioned further upon the subject, and Dinah considerately changed the conversation.

When the three little girls returned to the dining-room, they found the cloth had been laid for tea, the lamps lit, and the curtains drawn; everything looked very comfortable and homely.

"Where are mother and Tom?" Dinah inquired of Gilbert, the sole occupant of the room, as she drew Angel to the fireside, and gave her a comfortable chair.

"Mother has gone to see about muffins for tea, and Tom's cleaning up," he explained, as he slowly crossed the room from the window to the fireplace.

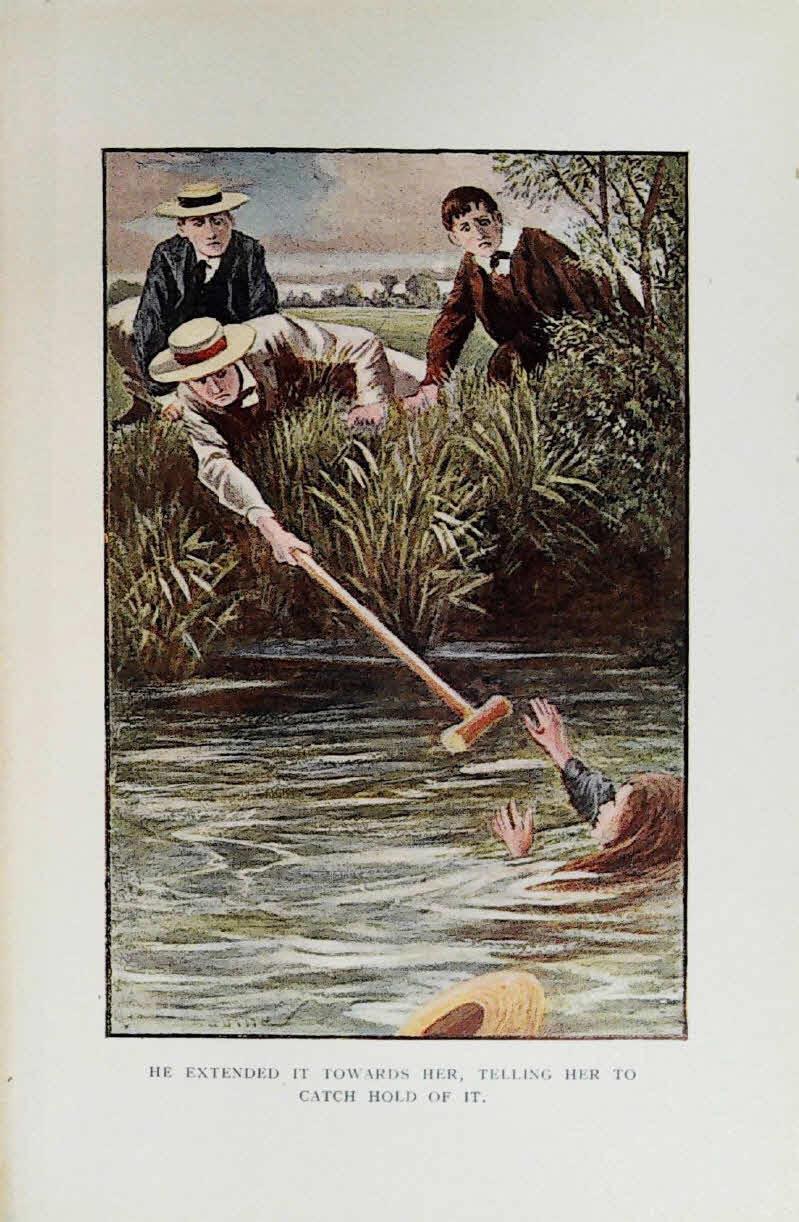

It was then that Angel saw for the first time that the boy walked with the assistance of crutches; she had not particularly noticed him before. Her heart swelled with pity as she realized that he was a cripple, and her little start of astonishment was not lost upon him.

"What is the matter?" he questioned sharply. "Did you never see any one on crutches before? Look here!" And he proceeded to swing himself up and down the room at a great rate. "You see how it's done, don't you? Now, you needn't stare at me any more!"

"Gilbert!" Dinah cried reprovingly, as he flung himself rather breathlessly into a chair, and allowed his crutches to drop on the floor with a crash.

"I—I did not mean to stare!" Angel gasped, aghast at the rage depicted in every line of the boy's face. "If I did, I am very sorry! It must have seemed dreadfully rude, but—"

"It is Gilbert who is rude," Dinah said severely, for though several years her brother's junior, she never scrupled to speak out to him.

"Never mind, Angel," whispered Dora consolingly; "Gilbert is always like that; you mustn't take any notice of him; we never do."

"What are you whispering about?" he asked suspiciously. He took no notice of Dinah's reproof; perhaps he knew he deserved it. "When girls get together they're always whispering."

Angel thought him a most disagreeable, ill-mannered boy; nevertheless, her kind heart was very sympathetic; she picked up his crutches from the floor, and put them within his reach.

"I am so very sorry if I annoyed you," she said in tones of real distress, "I had no idea I was staring. Do forgive me."

"Oh, it's all right! You needn't apologize," he responded gruffly; "I suppose you were surprised to see I was a miserable cripple."

"I am very sorry," Angel murmured, almost in tears. "It must be dreadful for you."

"Oh, I don't want you to pity me. I hate pity! I say, you aren't going to cry, are you? There'll be no end of a row if you do. I didn't mean to make you cry."

"I am not crying!" Angel declared, which was true, for she had blinked away the tears which had threatened to fall.

At that point Mrs. Mickle appeared, and not long afterwards Tom came noisily into the room, almost colliding with the parlour-maid, who was bringing in a dish of muffins and the teapot. Then Mr. Mickle and Mr. Bailey joined the party, and after the latter had been introduced to Mrs. Mickle and the children, they all sat down around the big dining-table, and the meal commenced.

"I was acquainted with your husband's father many years ago," Mr. Bailey told Mrs. Mickle. He was sitting at her right hand, talking to her as easily as though he had known her all his life. "You have doubtless heard I have bought Haresdown House," he continued; "I hope you and your young people will often come to see me when I am settled there. I'm a lonely, old bachelor, but I'm inclined to be sociable, you must understand."

"You will have your little niece with you?" Mrs. Mickle suggested.

"Oh no!" Angel exclaimed.

"I am afraid not," Mr. Bailey said, shaking his head regretfully; "my little niece has a father and brother, to both of whom she is devoted; I am not sure that they would consent to my taking her away from them!"

"Your father is an artist, is he not?" Mr. Mickle asked, turning to Angel. "I saw a book for children the other day most charmingly illustrated by one John Willis."

"Oh, that is my father!" Angel cried, her eyes flashing with delight, her heart swelling with pride. "He illustrates books most beautifully, and paints pictures too."

Mr. Mickle appeared much interested, and questioned his little visitor further. Encouraged by his evident appreciation of her father's abilities, Angel lost all her shyness, and told him of the great picture of which so much was expected.

"Indeed, I hope it will be a success," he said kindly; "if it is in the Royal Academy, I think I must run up to town in May and have a look at it!"

"How I should like to see your father's picture!" exclaimed Gilbert, meeting Angel's eyes across the table.

"Ah, Gilbert is fond of painting," his father remarked.

"Do you paint yourself?" Angel inquired, looking at the boy with friendly interest, momentarily forgetful of the uncomfortable five minutes he had given her before tea.

"A little," he acknowledged, "but I have never learnt."

"I have been remarking to your uncle that I hoped we should see more of you, my dear," Mrs. Mickle said to Angel; "but he tells me you are returning to London to-morrow!"

"And I have been saying that I shall expect you to pay me a long visit soon at Haresdown House, Angel," Mr. Bailey broke in, "and then Mrs. Mickle and all our kind, new friends will have an opportunity of renewing their acquaintance with you." And he nodded smilingly at the faces around the table.

"Oh, are you really going to-morrow," Dora cried disappointedly, "just as we have got to know you? That is too bad!"

The remainder of the meal passed very pleasantly; and Angel was exceedingly sorry when, a little later, her uncle bade her put on her hat and jacket, for they must go.

"When you come to visit Mr. Bailey we shall hope to see a lot of you," Mrs. Mickle said hospitably, as she shook hands with her little guest at parting, and gave her a kiss. "Good-bye, my dear; I trust we shall meet again."

"Good-bye!" Angel replied softly, as she returned the caress. "How kind of you to kiss me! No one has kissed me quite like that since mother died."

Then she took leave of the children and their father, and went away with Mr. Bailey, waving her hand to the group of faces watching from the window, wondering if she would ever see them again.

"What very nice people they are, Uncle Edward," she said, as soon as they were out of sight of the house.

"Yes," he agreed. "Mr. Mickle is going to see to my affairs. I have been on the lookout for a reliable lawyer since my return to England; I am glad now I did not enlist the services of one in London. I knew this man's father, and I like the man himself."

"I like him too," Angel replied. "Fancy his having seen some of father's illustrations! He was very kind, so was Mrs. Mickle, and Dinah and Dora. Uncle Edward, did you notice one of the boys is a cripple?"

"Yes; it is very sad. Such a handsome boy too, and remarkably clever, his father told me. Ah, it is a terrible cross for the poor lad to bear! He has been lame from birth. The younger boy looks full of life and mischief; Gerald would like him, eh?"

"I am sure he would."

"Gerald would enjoy the country as well as you, I dare say; if all's well, he shall spend his Easter holidays at Haresdown House next year."

The little girl slipped her fingers into Mr. Bailey's hand, and gave it a gentle squeeze. She was delighted at the thought of the pleasure in store for her brother.

"May I tell him what you say?" she asked. "He was a little disappointed at having to remain at home now."

"Was he? Yes, you can tell him, if you like. Are you sorry we are leaving here to-morrow?"

"Yes, although I shall be glad to see father and Gerald again. What a long time a week seems sometimes, Uncle Edward! And, oh, what a lot I shall have to tell when I get home!"

The following day Mr. Bailey and his little niece returned to London. Their visit to Wreyford had been a great success, for the weather had been mild and pleasant, and they had been thus enabled to spend most of the time out of doors; Mr. Bailey had been gratified to find a few old friends still living in the place, with whom he had renewed acquaintance; and everything had been so new and strange to Angel, that the week in the country had almost seemed like a glimpse into fairyland, so charmed was she with the quiet, old town, its ancient church on the hill, and the beautiful scenery which stretched around.

THE short December day was drawing to a close as the fast train from the west of England slowed into Paddington Station, and Mr. Bailey let down one of the windows of the compartment in which he and Angel were seated, and peered into the gloom without.

"Now for bricks and mortar once more!" he exclaimed. "What a dense fog to be sure! It looks as though one could cut it with a knife! I scarcely fancy your father will be here to meet us on a night like this."

But he was wrong in his surmise, for the moment after the train had stopped, and he had alighted himself, and lifted Angel on to the platform by his side, she was in her father's arms, whispering how very glad she was to see him again.

"I did not expect to see you," Mr. Bailey said, as he shook his nephew by the hand, "but I am very pleased you have come. I hardly know my way about in a fog, so you must act as pilot."

Mr. Willis agreed, and a few minutes later found them seated in a cab, being driven slowly through the streets, for the fog was too thick to admit of faster progress.

"Are you sure our luggage is all right, father?" Angel asked anxiously. "Is the hamper there too?"

"Yes, your belongings are safe in front with the driver. May I inquire what the hamper contains?"

"Oh, it is a regular country hamper," Mr. Bailey replied, smiling, "and it contains—"

"Butter, and cream, and fowls," Angel broke in eagerly, "and other nice things to eat. The hamper is a present from Uncle Edward, father. He says one always ought to take back a hamper from the country."

"Uncle Edward is very kind," Mr. Willis remarked, with gratitude in his voice. "I declare, Angel, in spite of your journey, you are looking much better and brighter than I ever saw you look before," he continued; "the light is dim, and I may be deceived, but surely those are roses in your cheeks?"

"Then they must be winter ones," Mr. Bailey said, laughing, "but they are none the less becoming on that account. I am glad you think she looks well, John. We have had a happy time together—have we not?" he asked, turning to Angel.

"Very happy." she answered readily. "Oh, father, I think the country is beautiful! The sky is so clear, and the sun shines so brightly, and Wreyford is a simply lovely place!"

Her father smiled at her enthusiasm, and regarded her tenderly with affectionate eyes. He had missed his little daughter during the past week—he had not anticipated he would miss her so much—and he was delighted to see her bright and happy, He had felt very dull of an evening during her absence, for since her mother's death he had fallen into the habit of talking to her of his plans for the future; if Angel lacked the artistic temperament, she Was a most sympathetic listener, and she thoroughly believed in her father and his work.

"How is Gerald?" she questioned presently.

"He is very well. He wanted to come with me to Paddington, but I bade him remain at home and prepare his lessons for to-morrow, so that he might have a free evening with us to-night. I think he has missed your help in his lessons."

She laughed happily, for it was so nice to know she had been missed. Since her mother's death she had never felt so free from care as she did now; for the time she had forgotten all the little worries and troubles of her home life.

The cab proceeded very slowly, sometimes stopping altogether for several minutes, so that it was more than an hour after they had started from Paddington before they reached their destination. Angel was the first to enter the house, and rushing upstairs ran into the arms of her brother, who had heard the cab draw up at the door, and was coming down to meet her. The two children hugged and kissed each other; then, being joined by their father and uncle, they all went up to the sitting-room, where a substantial high tea awaited them.

It made Angel's heart glow with pleasure to see how glad every one was that she had come home. Mrs. Steer brought hot water to her bedroom, and stood by whilst the little girl removed the traces of her journey, and explained how greatly she had been missed.

"Your pa's been like a hen that's lost its one chick, Miss Angel," the landlady said; "I'll be bound to say this last week has been a long one for him. I think he missed you evenings most of all. Master Gerald, for all he's so clever, will never be the same to your pa as you are, my dear. The boy has an aggravating way with him sometimes, and he's not as obedient as he might be. One night he and your pa had words about his lessons. It would never have happened if you'd been here."

"What happened?" Angel asked, a slight shadow of anxiety creeping over her face.

"Well, as far as I could make out, Master Gerald said he'd learnt his lessons, and your pa said he didn't believe he had, because he hadn't been long about them, and Master Gerald declared he knew them perfectly. Then your pa took up his books and questioned him."

"And couldn't Gerald answer the questions?"

"No, miss, he couldn't. Your pa was very angry, and Master Gerald turned sulky, but he had to learn the lessons properly. After that he went to bed without any supper."