Title: Gondola days

Author: F. Hopkinson Smith

Illustrator: F. Hopkinson Smith

Release Date: August 31, 2023 [eBook #71528]

Language: English

Credits: D A Alexander, David E. Brown, and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team at https://www.pgdp.net (This file was produced from images generously made available by The Internet Archive)

FICTION AND TRAVEL

By F. Hopkinson Smith.

TOM GROGAN. Illustrated. 12mo, gilt top, $1.50.

A GENTLEMAN VAGABOND, AND SOME OTHERS. 16mo, $1.25.

COLONEL CARTER OF CARTERSVILLE. With 20 illustrations by the author and E. W. Kemble. 16mo, $1.25.

A DAY AT LAGUERRE’S, AND OTHER DAYS. Printed in a new style. 16mo, $1.25.

A WHITE UMBRELLA IN MEXICO. Illustrated by the author. 16mo, gilt top, $1.50.

GONDOLA DAYS. Illustrated, 12mo, $1.50.

WELL-WORN ROADS OF SPAIN, HOLLAND, AND ITALY, traveled by a Painter in search of the Picturesque. With 16 full-page phototype reproductions of water-color drawings, and text by F. Hopkinson Smith, profusely illustrated with pen-and-ink sketches. A Holiday volume. Folio, gilt top, $15.00.

THE SAME. Popular Edition. Including some of the illustrations of the above. 16mo, gilt top, $1.25.

HOUGHTON, MIFFLIN & CO.

Boston and New York.

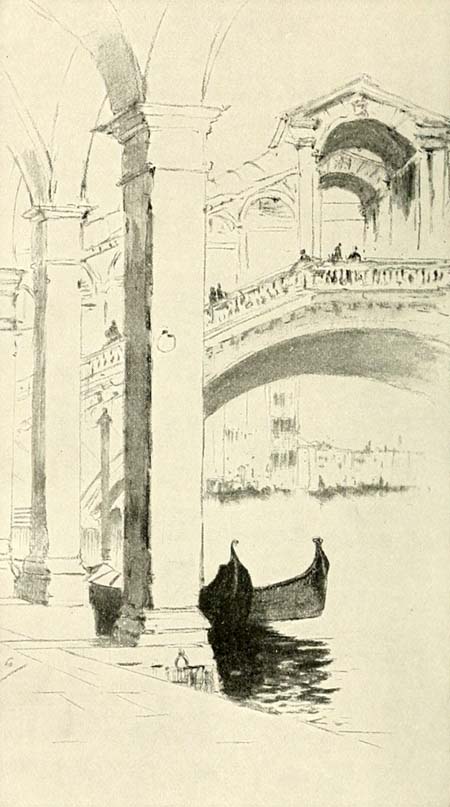

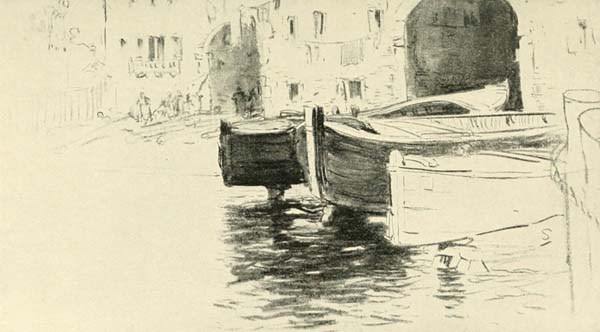

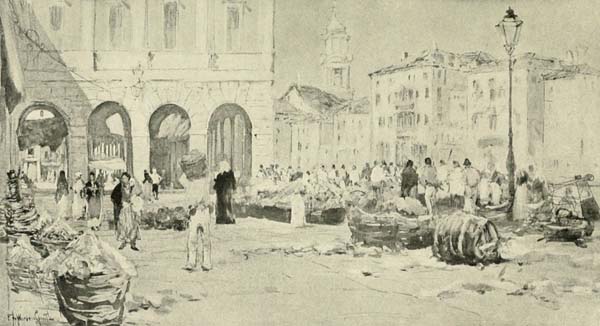

BACK OF THE RIALTO (PAGE 87)

GONDOLA DAYS

BY F. HOPKINSON SMITH

WITH ILLUSTRATIONS

BY THE AUTHOR

BOSTON AND NEW YORK

HOUGHTON MIFFLIN AND

COMPANY THE RIVERSIDE

PRESS CAMBRIDGE 1897

COPYRIGHT, 1897, BY F. HOPKINSON SMITH

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

THE text of this volume is the same as that of “Venice of To-Day,” recently published by the Henry T. Thomas Company, of New York, as a subscription book, in large quarto and folio form, with over two hundred illustrations by the Author, in color and in black and white.

I HAVE made no attempt in these pages to review the splendors of the past, or to probe the many vital questions which concern the present, of this wondrous City of the Sea. Neither have I ventured to discuss the marvels of her architecture, the wealth of her literature and art, nor the growing importance of her commerce and manufactures.

I have contented myself rather with the Venice that you see in the sunlight of a summer’s day—the Venice that bewilders with her glory when you land at her water-gate; that delights with her color when you idle along the Riva; that intoxicates with her music as you lie in your gondola adrift on the bosom of some breathless lagoon—the Venice of mould-stained palace, quaint caffè and arching bridge; of fragrant incense, cool, dim-lighted church, and noiseless priest; of strong-armed men and graceful women—the Venice of light and life, of sea and sky and melody.

No pen alone can tell this story. The pencil and the palette must lend their touch when one would picture the wide sweep of her piazzas, the abandon of her gardens, the charm of her canal and street life, the happy indolence of her people, the faded sumptuousness of her homes.

If I have given to Venice a prominent place among the cities of the earth it is because in this selfish, materialistic, money-getting age, it is a joy to live, if only for a day, where a song is more prized than a soldo; where the poorest pauper laughingly shares his scanty crust; where to be kind to a child is a habit, to be neglectful of old age a shame; a city the relics of whose past are the lessons of our future; whose every canvas, stone, and bronze bear witness to a grandeur, luxury, and taste that took a thousand years of energy to perfect, and will take a thousand years of neglect to destroy.

To every one of my art-loving countrymen this city should be a Mecca; to know her thoroughly is to know all the beauty and romance of five centuries.

F. H. S.

| An Arrival | 1 |

| Gondola Days | 8 |

| Along the Riva | 28 |

| The Piazza of San Marco | 42 |

| In an Old Garden | 58 |

| Among the Fishermen | 85 |

| A Gondola Race | 101 |

| Some Venetian Caffès | 116 |

| On the Hotel Steps | 126 |

| Open-Air Markets | 136 |

| On Rainy Days | 145 |

| Legacies of the Past | 155 |

| Life in the Streets | 176 |

| Night in Venice | 197 |

| Back of the Rialto (see page 87) | Frontispiece |

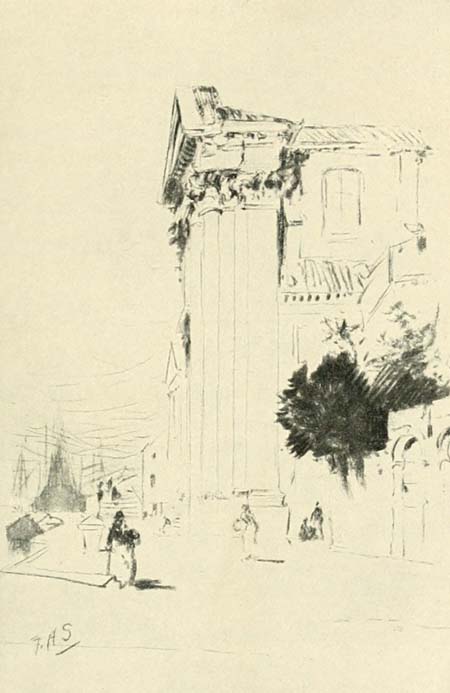

| The Gateless Posts of the Piazzetta | 14 |

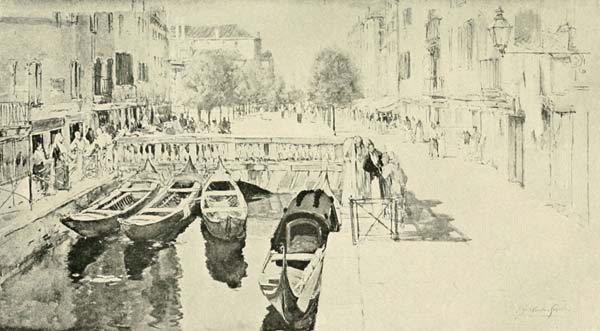

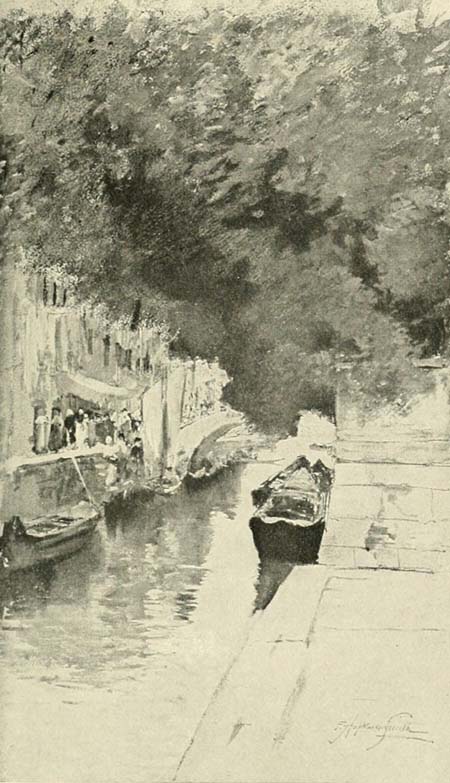

| The One Whistler etched | 26 |

| Beyond San Rosario | 58 |

| The Catch of the Morning | 90 |

| A Little Hole in the Wall on the Via Garibaldi | 116 |

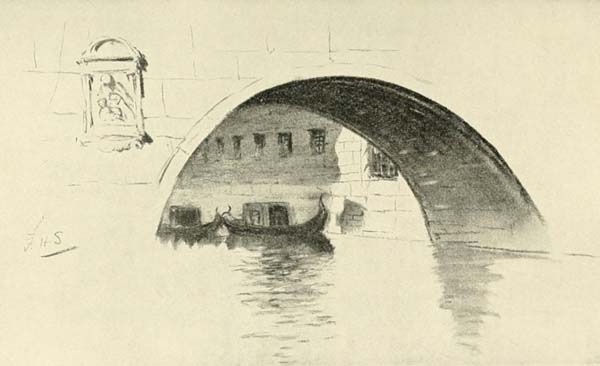

| Ponte Paglia ... next the Bridge of Sighs | 136 |

| The Fruit Market above the Rialto | 140 |

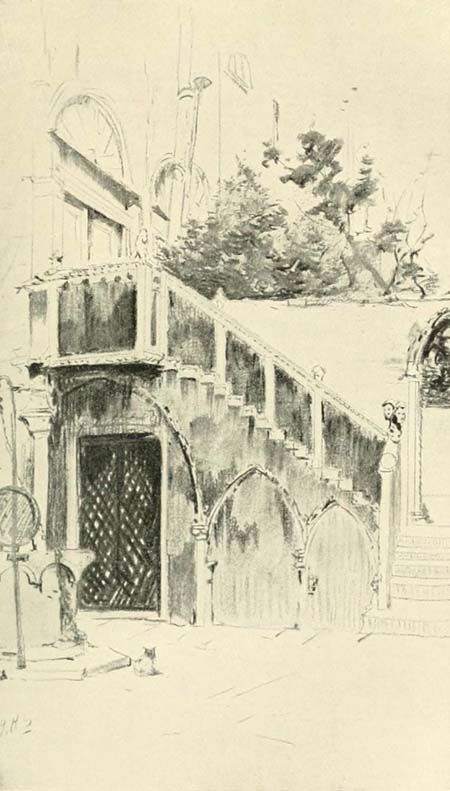

| Wide Palatial Staircases | 160 |

| Narrow Slits of Canals | 186 |

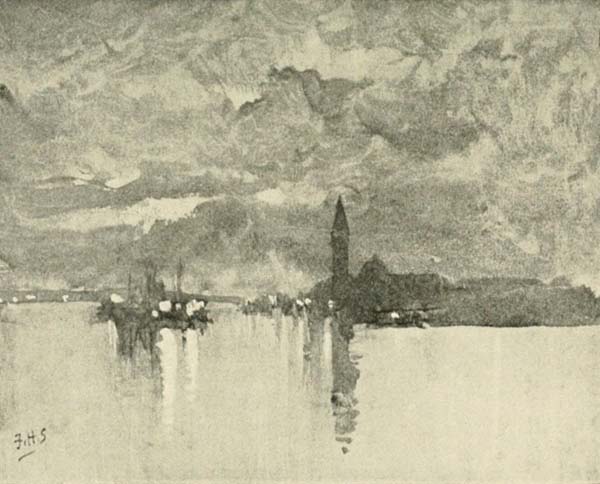

| San Giorgio stands on Tip-toe | 198 |

YOU really begin to arrive in Venice when you leave Milan. Your train is hardly out of the station before you have conjured up all the visions and traditions of your childhood: great rows of white palaces running sheer into the water; picture-book galleys reflected upside down in red lagoons; domes and minarets, kiosks, towers, and steeples, queer-arched temples, and the like.

As you speed on in the dusty train, your memory-fed imagination takes new flights. You expect gold-encrusted barges, hung with Persian carpets, rowed by slaves double-banked, and trailing rare brocades in a sea of China-blue, to meet you at the water landing.

By the time you reach Verona your mental panorama makes another turn. The very name suggests the gay lover of the bal masque, the poisoned vial, and the calcium moonlight illuminating the wooden tomb of the stage-set graveyard. You instinctively look around for the fair Juliet and her nurse. There are half a dozen as pretty Veronese,[2] attended by their watchful duennas, going down by train to the City by the Sea; but they do not satisfy you. You want one in a tight-fitting white satin gown with flowing train, a diamond-studded girdle, and an ostrich-plume fan. The nurse, too, must be stouter, and have a high-keyed voice; be bent a little in the back, and shake her finger in a threatening way, as in the old mezzotints you have seen of Mrs. Siddons or Peg Woffington. This pair of Dulcineas on the seat in front, in silk dusters, with a lunch-basket and a box of sweets, are too modern and commonplace for you, and will not do.

When you roll into Padua, and neither doge nor inquisitor in ermine or black gown boards the train, you grow restless. A deadening suspicion enters your mind. What if, after all, there should be no Venice? Just as there is no Robinson Crusoe nor man Friday; no stockade, nor little garden; no Shahrazad telling her stories far into the Arabian night; no Santa Claus with reindeer; no Rip Van Winkle haunted by queer little gnomes in fur caps. As this suspicion deepens, the blood clogs in your veins, and a thousand shivers go down your spine. You begin to fear that all these traditions of your[3] childhood, all these dreams and fancies, are like the thousand and one other lies that have been told to and believed by you since the days when you spelled out words in two syllables.

Upon leaving Mestre—the last station—you smell the salt air of the Adriatic through the open car window. Instantly your hopes revive. Craning your head far out, you catch a glimpse of a long, low, monotonous bridge, and away off in the purple haze, the dreary outline of a distant city. You sink back into your seat exhausted. Yes, you knew it all the time. The whole thing is a swindle and a sham!

“All out for Venice,” says the guard, in French.

Half a dozen porters—well-dressed, civil-spoken porters, flat-capped and numbered—seize your traps and help you from the train. You look up. It is like all the rest of the depots since you left Paris—high, dingy, besmoked, beraftered, beglazed, and be——! No, you are past all that. You are not angry. You are merely broken-hearted. Another idol of your childhood shattered; another coin that your soul coveted, nailed to the wall of your experience—a counterfeit!

“This door to the gondolas,” says the[4] porter. He is very polite. If he were less so, you might make excuse to brain him on the way out.

The depot ends in a narrow passageway. It is the same old fraud—custom-house officers on each side; man with a punch mutilating tickets; rows of other men with brass medals on their arms the size of apothecaries’ scales—hackmen, you think, with their whips outside—licensed runners for the gondoliers, you learn afterward. They are all shouting—all intent on carrying you off bodily. The vulgar modern horde!

Soon you begin to breathe more easily. There is another door ahead, framing a bit of blue sky. “At least, the sun shines here,” you say to yourself. “Thank God for that much!”

“This way, Signore.”

One step, and you stand in the light. Now look! Below, at your very feet, a great flight of marble steps drops down to the water’s edge. Crowding these steps is a throng of gondoliers, porters, women with fans and gay-colored gowns, priests, fruit-sellers, water-carriers, and peddlers. At the edge, and away over as far as the beautiful marble church, a flock of gondolas like black swans curve in and out. Beyond stretches the[5] double line of church and palace, bordering the glistening highway. Over all is the soft golden haze, the shimmer, the translucence of the Venetian summer sunset.

With your head in a whirl,—so intense is the surprise, so foreign to your traditions and dreams the actuality,—you throw yourself on the yielding cushions of a waiting gondola. A turn of the gondolier’s wrist, and you dart into a narrow canal. Now the smells greet you—damp, cool, low-tide smells. The palaces and warehouses shut out the sky. On you go—under low bridges of marble, fringed with people leaning listlessly over; around sharp corners, their red and yellow bricks worn into ridges by thousands of rounding boats; past open plazas crowded with the teeming life of the city. The shadows deepen; the waters glint like flakes of broken gold-leaf. High up in an opening you catch a glimpse of a tower, rose-pink in the fading light; it is the Campanile. Farther on, you slip beneath an arch caught between two palaces and held in mid-air. You look up, shuddering as you trace the outlines of the fatal Bridge of Sighs. For a moment all is dark. Then you glide into a sea of opal, of amethyst and sapphire.

The gondola stops near a small flight of[6] stone steps protected by huge poles striped with blue and red. Other gondolas are debarking. A stout porter in gold lace steadies yours as you alight.

“Monsieur’s rooms are quite ready. They are over the garden; the one with the balcony overhanging the water.”

The hall is full of people (it is the Britannia, the best hotel in Venice), grouped about the tables, chatting or reading, sipping coffee or eating ices. Beyond, from an open door, comes the perfume of flowers. You pass out, cross a garden, cool and fresh in the darkening shadows, and enter a small room opening on a staircase. You walk up and through the cosy apartments, push back a folding glass door, and step out upon a balcony of marble.

How still it all is! Only the plash of the water about the bows of the gondolas, and the little waves snapping at the water-steps. Even the groups of people around the small iron tables below, partly hidden by the bloom of oleanders, talk in half-heard whispers.

You look about you,—the stillness filling your soul, the soft air embracing you,—out over the blossoms of the oleanders, across the shimmering water, beyond the beautiful dome of the Salute, glowing like a huge[7] pearl in the clear evening light. No, it is not the Venice of your childhood; not the dream of your youth. It is softer, more mellow, more restful, more exquisite in its harmonies.

Suddenly a strain of music breaks upon your ear—a soft, low strain. Nearer it comes, nearer. You lean forward over the marble rail to catch its meaning. Far away across the surface of the beautiful sea floats a tiny boat. Every swing of the oar leaves in its wake a quivering thread of gold. Now it rounds the great red buoy, and is lost behind the sails of a lazy lugger drifting with the tide. Then the whole broad water rings with the melody. In another instant it is beneath you—the singer standing, holding his hat for your pennies; the chorus seated, with upturned, expectant faces.

Into the empty hat you pour all your store of small coins, your eyes full of tears.

THAT first morning in Venice! It is the summer, of course—never the winter. This beautiful bride of the sea is loveliest when bright skies bend tenderly over her, when white mists fall softly around her, and the lagoons about her feet are sheets of burnished silver: when the red oleanders thrust their blossoms exultingly above the low, crumbling walls: when the black hoods of winter felsi are laid by at the traghetti, and gondolas flaunt their white awnings: when the melon-boats, with lifeless sails, drift lazily by, and the shrill cry of the fruit vender floats over the water: when the air is steeped, permeated, soaked through and through with floods of sunlight—quivering, brilliant, radiant; sunlight that blazes from out a sky of pearl and opal and sapphire; sunlight that drenches every old palace with liquid amber, kissing every moulding awake, and soothing every shadow to sleep; sunlight that caresses and does not scorch, that dazzles and does not blind, that illumines, irradiates, makes glorious, every sail and tower and dome, from the instant the[9] great god of the east shakes the dripping waters of the Adriatic from his face until he sinks behind the purple hills of Padua.

These mornings, then! How your heart warms and your blood tingles when you remember that first one in Venice—your first day in a gondola!

You recall that you were leaning upon your balcony overlooking the garden when you caught sight of your gondolier; the gondolier whom Joseph, prince among porters, had engaged for you the night of your arrival.

On that first morning you were just out of your bed. In fact, you had hardly been in it all night. You had fallen asleep in a whirl of contending emotions. Half a dozen times you had been up and out on this balcony, suddenly aroused by the passing of some music-boat filling the night with a melody that seemed a thousand fold more enchanting because of your sudden awakening,—the radiant moon, and the glistening water beneath. I say you were out again upon this same balcony overlooking the oleanders, the magnolias, and the palms. You heard the tinkling of spoons in the cups below, and knew that some earlier riser was taking his coffee in the dense shrubbery; but it made[10] no impression upon you. Your eye was fixed on the beautiful dome of the Salute opposite; on the bronze goddess of the Dogana waving her veil in the soft air; on the group of lighters moored to the quay, their red and yellow sails aglow; on the noble tower of San Giorgio, sharp-cut against the glory of the east.

Now you catch a waving hand and the lifting of a cap on the gravel walk below. “At what hour will the Signore want the gondola?”

You remember the face, brown and sunny, the eyes laughing, the curve of the black mustache, and how the wavy short hair curled about his neck and struggled out from under his cap. He has on another suit, newly starched and snow-white; a loose shirt, a wide collar trimmed with blue, and duck trousers. Around his waist is a wide blue sash, the ends hanging to his knees. About his throat is a loose silk scarf—so loose that you note the broad, manly chest, the muscles of the neck half concealed by the cross-barred boating-shirt covering the brown skin.

There is a cheeriness, a breeziness, a spring about this young fellow that inspires you. As you look down into his face you feel that[11] he is part of the air, of the sunshine, of the perfume of the oleanders. He belongs to everything about him, and everything belongs to him. His costume, his manner, the very way he holds his hat, show you at a glance that while for the time being he is your servant, he is, in many things deeply coveted by you, greatly your master. If you had his chest and his forearm, his sunny temper, his perfect digestion and contentment, you could easily spare one half of your world’s belongings in payment. When you have lived a month with him and have caught the spirit of the man, you will forget all about these several relations of servant and master. The six francs a day that you pay him will seem only your own contribution to the support of the gondola; his share being his services. When you have spent half the night at the Lido, he swimming at your side, or have rowed all the way to Torcello, or have heard early mass at San Rosario, away up the Giudecca, he kneeling before you, his hat on the cool pavement next your own, you will begin to lose sight even of the francs, and want to own gondola and all yourself, that you may make him guest and thus discharge somewhat the ever-increasing obligation of hospitality under which he places you.[12] Soon you will begin to realize that despite your belongings—wealth to this gondolier beyond his wildest dreams—he in reality is the richer of the two. He has inherited all this glory of palace, sea, and sky, from the day of his birth, and can live in it every hour in the year, with no fast-ebbing letter-of-credit nor near-approaching sailing day to sadden his soul or poison the cup of his pleasure. When your fatal day comes and your trunk is packed, he will stand at the water-stairs of the station, hat in hand, the tears in his eyes, and when one of the demons of the master-spirit of the age—Hurry—has tightened its grip upon you and you are whirled out and across the great iron bridge, and you begin once more the life that now you loathe, even before you have reached Mestre—if your gondolier is like my own gondolier, Espero—my Espero Gorgoni, whom I love—you would find him on his knees in the church next the station, whispering a prayer for your safe journey across the sea, and spending one of your miserable francs for some blessed candles to burn until you reached home.

But you have not answered your gondolier, who stands with upturned eyes on the graveled walk below.

[13]“At what hour will the Signore want the gondola?”

You awake from your reverie. Now! as soon as you swallow your coffee. Ten minutes later you bear your weight on Giorgio’s bent elbow and step into his boat.

It is like nothing else of its kind your feet have ever touched—so yielding and yet so firm; so shallow and yet so stanch; so light, so buoyant, and so welcoming to peace and rest and comfort.

How daintily it sits the water! How like a knowing swan it bends its head, the iron blade of the bow, and glides out upon the bosom of the Grand Canal! You stop for a moment, noting the long, narrow body, blue-black and silver in the morning light, as graceful in its curves as a bird; the white awning amidships draped at sides and back, the softly-yielding, morocco-covered seat, all cushions and silk fringes, and the silken cords curbing quaint lions of polished brass. Beyond and aft stands your gondolier, with easy, graceful swing bending to his oar. You stoop down, part the curtains, and sink into the cushions. Suddenly an air of dignified importance steals over you. Never in your whole life have you been so magnificently carried about. Four-in-hands, commodores’[14] gigs, landaus in triumphant processions with white horses and plumes, seem tame and commonplace. Here is a whole barge, galleon, Bucentaur, all to yourself; noiseless, alert, subservient to your airiest whim, obedient to the lightest touch. You float between earth and sky. You feel like a potentate out for an airing, housed like a Rajah, served like Cleopatra, and rowed like a Doge. You command space and dominate the elements.

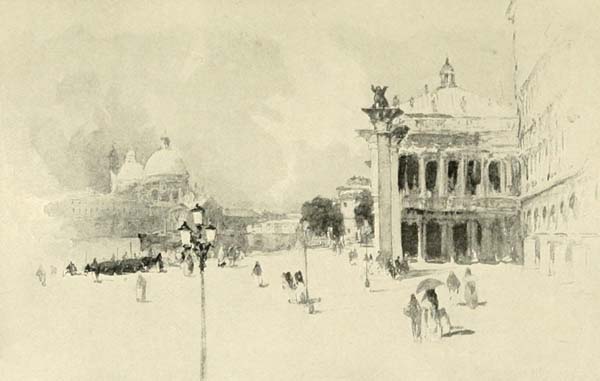

THE GATELESS POSTS OF THE PIAZZETTA

But Giorgio is leaning on his oar, millions of diamonds dripping from its blade.

“Where now, Signore?”

Anywhere, so he keeps in the sunlight. To the Piazza, perhaps, and then around San Giorgio with its red tower and noble façade, and later, when the shadows lengthen, away down to the Public Garden, and home again in the twilight by way of the Giudecca.

This gondola-landing of the Piazza, the most important of the cab-stands in Venice, is the stepping-stone—a wet and ooze-covered stone—to the heart of the city. Really the heart, for the very life of every canal, campo, and street, courses through it in unending flow all the livelong day and night, from the earliest blush of dawn to the earliest blush of dawn again; no one ever seems to go to bed in Venice. Along and near the[15] edge of this landing stand the richest examples of Venetian architecture. First, the Royal Gardens of the king’s palace, with its balustrade of marble and broad flight of water-steps; then the Library, with its cresting of statues, white against the sky; then the two noble columns, the gateless posts of the Piazzetta, bearing Saint Theodore and the Lion of Venice; and beyond, past the edge of San Marco, the clock tower and the three great flag-staffs; then the Palace of the Doges, that masterwork of the fifteenth century; then the Prison, with a glimpse of the Bridge of Sighs, caught in mid-air; then the great cimeter-sweep of the Riva, its point lost in the fringe of trees shading the Public Garden; and then, over all, as you look up, the noble Campanile, the wonderful bell-tower of San Marco, unadorned, simple, majestic—up, up, into the still air, its gilded angel, life-size, with outstretched wings flashing in the morning sun, a mere dot of gold against the blue.

Before you touch the lower steps of the water-stairs, your eye falls upon an old man with bared head. He holds a long staff studded with bad coins, having a hook at one end. With this in one hand he steadies your gondola, with the other he holds out his hat.[16] He is an aged gondolier, too old now to row. He knows you, the poor fellow, and he knows your kind. How many such enthusiasts has he helped to alight! And he knows Giorgio too, and remembers when, like him, he bent his oar with the best. You drop a penny into his wrinkled hand, catch his grateful thanks, and join the throng. The arcades under the Library are full of people smoking and sipping coffee. How delicious the aroma and the pungent smell of tobacco! In the shadow of the Doges’ Palace groups idle and talk—a little denser in spots where some artist has his easel up, or some pretty, dainty child is feeding the pigeons.

A moment more and you are in the Piazza of San Marco; the grand piazza of the doges, with its thousands of square feet of white pavement blazing in the sun, framed on three sides by marble palaces, dominated by the noblest campanile on the globe, and enriched, glorified, made inexpressibly precious and unique by that jewel in marble, in porphyry, in verd antique and bronze, that despair of architects of to-day, that delight of the artists of all time—the most sacred, the Church of San Marco.

In and out this great quadrangle whirl the pigeons, the pigeons of Dandolo, up into the[17] soft clouds, the light flashing from their throats; sifting down in showers on gilded cross and rounded dome; clinging to intricate carvings, over and under the gold-crowned heads of saints in stone and bronze; across the baking plaza in flurries of gray and black; resting like a swarm of flies, only to startle, mass, and swirl again. Pets of the state, these birds, since the siege of Candia, when the great Admiral Dandolo’s chief bearer of dispatches, the ancestor of one of these same white-throated doves, brought the good news to Venice the day the admiral’s victorious banner was thrown to the breeze, and the Grand Council, sitting in state, first learned the tidings from the soft plumage of its wings.

At one end, fronting the church, stand the three great flag-poles, the same you saw at the landing, socketed in bronze, exquisitely modeled and chased, bearing the banners of Candia, Cyprus, and the Morea—kingdoms conquered by the state—all three in a row, presenting arms to the power that overthrew them, and forever dipping their colors to the glory of its past.

Here, too, in this noble square, under your very feet, what solemnities, what historic fêtes, what conspiracies! Here for centuries[18] has been held the priestly pageant of Corpus Christi, aflame with lanterns and flambeaux. Here eleven centuries ago blind old Dandolo received the Crusader chiefs of France. Here the splendid nuptials of Francesco Foscari were celebrated by a tournament, witnessed by thirty thousand people, and lasting ten days. Here the conspiracies of Tiepolo and Faliero were crushed—Venetian against Venetian the only time in a thousand years. And here Italy suffered her crowning indignity, the occupation by the French under the newly-fledged warrior who unlimbered his cannon at the door of the holy church, pushed the four bronze horses from their pedestals over the sacred entrance—the horses of Constantine, wrought by Lysippus the Greek,—despoiled the noble church of its silver lamps, robbed the ancient column of its winged lion, and then, after a campaign unprecedented in its brilliancy, unexampled in the humiliation and degradation it entailed upon a people who for ten centuries had known no power outside of Venice, planted in the centre of this same noble square, with an irony as bitter as it was cruel, the “Tree of Liberty,” at which was burned, on the 4th of June, 1797, the insignia of the ancient republic.

[19]And yet, notwithstanding all her vicissitudes, the Venice of to-day is still the Venice of her glorious past, the Venice of Dandolo, Foscari, and Faliero. The actors are long since dead, but the stage-setting is the same; the same sun, the same air, the same sky over all. The beautiful dome of the Salute still dominates the Grand Canal. The great plaza is still perfect in all its proportions and in all that made up its beauty and splendor. The Campanile still raises its head, glistening in the morning light. High over all still flash and swoop the pigeons of Venice—the pigeons of Dandolo—now black as cinders, now flakes of gold in the yellow light. The doors of the sacred church are still open; the people pass in and out. Under the marble arcades, where the soldiers of the army of France stacked their arms, to-day sit hundreds of free Venetians, with their wives and sweethearts, sipping their ices and coffee; the great orchestra, the king’s band, filling the air with its music.

When you ask what magician has wrought this change, let the old guide answer as once he answered me when, crossing the Piazza and uncovering his head, he pointed to a stone and said, in his soft Italian:—

“Here, Signore,—just here, where the great[20] Napoleon burnt our flag,—the noble republic of our fathers, under our good King and his royal spouse, was born anew.”

But you cannot stay. You will return and study the Piazza to-morrow; not now. The air intoxicates you. The sunlight is in your blood; your cheeks burn; you look out and over the Grand Canal—molten silver in the shimmer of the morning. Below, near the Public Garden, beyond San Giorgio, like a cluster of butterflies, hovers a fleet of Chioggia fishing-boats, becalmed in the channel. Off the Riva, near Danieli’s, lies the Trieste steamer, just arrived, a swarm of gondolas and barcos about her landing-ladders; the yellow smoke of her funnel drifting lazily. Farther away, on the golden ball of the Dogana, the bronze Goddess of the Wind poises light as air, her face aflame, her whirling sail bent with the passing breeze.

You resolve to stop no more; only to float, loll on your cushions, watch the gulls circle, and the slow sweep of the oars of the luggers. You would throw open—wide open—the great swinging gates of your soul. You not only would enjoy, you would absorb, drink in, fill yourself to the brim.

For hours you drift about. There is plenty of time to-morrow for the churches and palaces[21] and caffès. To-day you want only the salt air in your face, the splash and gurgle of the water at the bow, and the low song that Giorgio sings to himself as he bends to his blade.

Soon you dart into a cool canal, skirt along an old wall, water stained and worn, and rest at a low step. Giorgio springs out, twists a cord around an iron ring, and disappears through an archway framing a garden abloom with flowering vines.

It is high noon. Now for your midday luncheon!

You have had all sorts of breakfasts offered you in your wanderings: On white-winged yachts, with the decks scoured clean, the brass glistening, the awning overhead. In the wilderness, lying on balsam boughs, the smell of the bacon and crisping trout filling the bark slant, the blue smoke wreathing the tall pines. In the gardens of Sunny Spain—one you remember at Granada, hugging the great wall of the Alhambra—you see the table now with its heap of fruit and flowers, and can hear the guitar of the gypsy behind the pomegranate. Along the shore of the beautiful bay of Matanzas, where the hidalgo who had watched you paint swept down in his volante and carried you off to his[22] oranges and omelette. At St. Cloud, along the Seine, with the noiseless waiter in the seedy dress suit and necktie of the night before. But the filet and melon! Yes, you would go again. I say you have had all sorts of breakfasts out of doors in your time, but never yet in a gondola.

A few minutes later Giorgio pushes aside the vines. He carries a basket covered with a white cloth. This he lays at your feet on the floor of the boat. You catch sight of the top of a siphon and a flagon of wine: do not hurry, wait till he serves it. But not here, where anybody might come; farther down, where the oleanders hang over the wall, their blossoms in the water, and where the air blows cool between the overhanging palaces.

Later Giorgio draws all the curtains except the side next the oleanders, steps aft and fetches a board, which he rests on the little side seats in front of your lounging-cushions. On this board he spreads the cloth, and then the seltzer and Chianti, the big glass of powdered ice and the little hard Venetian rolls. (By the bye, do you know that there is only one form of primitive roll, the world over?) Then come the cheese, the Gorgonzola—active, alert Gorgonzola, all green spots—wrapped[23] in a leaf; a rough-jacketed melon, with some figs and peaches. Last of all, away down in the bottom of the basket, there is a dish of macaroni garnished with peppers. You do not want any meat. If you did you would not get it. Some time when you are out on the canal, or up the Giudecca, you might get a fish freshly broiled from a passing cook-boat serving the watermen—a sort of floating kitchen for those who are too poor for a fire of their own—but never meat.

Giorgio serves you as daintily as would a woman; unfolding the cheese, splitting the rolls, parting the melon into crescents, flecking off each seed with his knife: and last, the coffee from the little copper coffee-pot, and the thin cakes of sugar, in the thick, unbreakable, dumpy little cups.

There are no courses in this repast. You light a cigarette with your first mouthful and smoke straight through: it is that kind of a breakfast.

Then you spread yourself over space, flat on your back, the smoke curling out through the half-drawn curtains. Soon your gondolier gathers up the fragments, half a melon and the rest,—there is always enough for two,—moves aft, and you hear the clink of[24] the glass and the swish of the siphon. Later you note the closely-eaten crescents floating by, and the empty leaf. Giorgio was hungry too.

But the garden!—there is time for that. You soon discover that it is unlike any other you know. There are no flower-beds and gravel walks, and no brick fountains with the scantily dressed cast-iron boy struggling with the green-painted dolphin, the water spurting from its open mouth. There is water, of course, but it is down a deep well with a great coping of marble, encircled by exquisite carvings and mellow with mould; and there are low trellises of grapes, and a tangle of climbing roses half concealing a weather-stained Cupid with a broken arm. And there is an old-fashioned sun-dial, and sweet smelling box cut into fantastic shapes, and a nest of an arbor so thickly matted with leaves and interlaced branches that you think of your Dulcinea at once. And there are marble benches and stone steps, and at the farther end an old rusty gate through which Giorgio brought the luncheon.

It is all so new to you, and so cool and restful! For the first time you begin to realize that you are breathing the air of a City of Silence. No hum of busy loom, no[25] tramp of horse or rumble of wheel, no jar or shock; only the voices that come over the water, and the plash of the ripples as you pass. But the day is waning; into the sunlight once more.

Giorgio is fast asleep; his arm across his face, his great broad chest bared to the sky.

“Si, Signore!”

He is up in an instant, rubbing the sleep from his eyes, catching his oar as he springs.

You glide in and out again, under marble bridges thronged with people; along quays lined with boats; by caffè, church, and palace, and so on to the broad water of the Public Garden.

But you do not land; some other day for that. You want the row back up the canal, with the glory of the setting sun in your face. Suddenly, as you turn, the sun is shut out: it is the great warship Stromboli, lying at anchor off the garden wall; huge, solid as a fort, fine-lined as a yacht, with exquisite detail of rail, mast, yard-arms, and gun mountings, the light flashing from her polished brasses.

In a moment you are under her stern, and beyond, skirting the old shipyard with the curious arch,—the one Whistler etched,—sheering to avoid the little steamers puffing[26] with modern pride, their noses high in air at the gondolas; past the long quay of the Riva, where the torpedo-boats lie tethered in a row, like swift horses eager for a dash; past the fruit-boats dropping their sails for a short cut to the market next the Rialto; past the long, low, ugly bath-house anchored off the Dogana; past the wonderful, the matchless, the never-to-be-unloved or forgotten, the most blessed, the Santa Maria della Salute.

THE ONE WHISTLER ETCHED

Oh! this drift back, square in the face of the royal sun, attended by all the pomp and glory of a departing day! What shall be said of this reveling, rioting, dominant god of the west, clothed in purple and fine gold; strewing his path with rose-leaves thrown broadcast on azure fields; rolling on beds of violet; saturated, steeped, drunken with color; every steeple, tower, and dome ablaze; the whole world on tip-toe, kissing its hands good-night!

Giorgio loves it, too. His cap is off, lying on the narrow deck; his cravat loosened, his white shirt, as he turns up the Giudecca, flashing like burning gold.

Somehow you cannot sit and take your ease in the fullness of all this beauty and grandeur. You spring to your feet. You must see behind and on both sides, your eye[27] roving eagerly away out to the lagoon beyond the great flour-mill and the gardens.

Suddenly a delicate violet light falls about you; the lines of palaces grow purple; the water is dulled to a soft gray, broken by long, undulating waves of blue; the hulls of the fishing-boats become inky black, their listless sails deepening in the falling shadows. Only the little cupola high up on the dome of the Redentore still burns pink and gold. Then it fades and is gone. The day is done!

THE afternoon hours are always the best. In the morning the great sweep of dazzling pavement is a blaze of white light, spotted with moving dots of color. These dots carry gay-colored parasols and fans, or shield their eyes with aprons, hugging, as they scurry along, the half-shadows of a bridge-rail or caffè awning. Here and there, farther down along the Riva, are larger dots—fruit-sellers crouching under huge umbrellas, or groups of gondoliers under improvised awnings of sailcloth and boat oars. Once in a while one of these water-cabmen darts out from his shelter like an old spider, waylays a bright fly as she hurries past, and carries her off bodily to his gondola. Should she escape he crawls back again lazily and is merged once more in the larger dot. In the noonday glare even these disappear; the fruit-sellers seeking some shaded calle, the gondoliers the cool coverings of their boats.

Now that the Sun God has chosen to hide his face behind the trees of the King’s Garden, this blaze of white is toned to a cool[29] gray. Only San Giorgio’s tower across the Grand Canal is aflame, and that but half way down its bright red length. The people, too, who have been all day behind closed blinds and doors, are astir. The awnings of the caffès are thrown back and the windows of the balconies opened. The waiters bring out little tables, arranging the chairs in rows like those in a concert hall. The boatmen who have been asleep under cool bridges, curled up on the decks of their boats, stretch themselves awake, rubbing their eyes. The churches swing back their huge doors—even the red curtains of the Chiesa della Pietà are caught to one side, so that you can see the sickly yellow glow of the candles far back on the altars and smell the incense as you pass.

Soon the current from away up near the Piazza begins to flow down towards the Public Garden, which lies at the end of this Grand Promenade of Venice. Priests come, and students; sailors on a half day’s leave; stevedores from the salt warehouses; fishermen; peddlers, with knick-knacks and sweetmeats; throngs from the hotels; and slender, graceful Venetians, out for their afternoon stroll in twos and threes, with high combs and gay shawls, worn as a Spanish[30] Donna would her mantilla—bewitching creatures in cool muslin dresses and wide sashes of silk, with restless butterfly fans, and restless, wicked eyes too, that flash and coax as they saunter along.

Watch those officers wheel and turn. See how they laugh when they meet. What confidences under mustachios and fans! Half an hour from now you will find the four at Florian’s, as happy over a little cherry juice and water as if it were the dryest of all the Extras. Later on, away out beyond San Giorgio, four cigarettes could light for you their happy faces, the low plash of their gondolier’s oar keeping time to the soft notes of a guitar.

Yes, one must know the Riva in the afternoon. I know it every hour in the day; though I love it most in the cool of its shadows. And I know every caffè, church, and palace along its whole length, from the Molo to the garden. And I know the bridges, too; best of all the one below the Arsenal, the Veneta Marina, and the one you cross before reaching the little church that stands aside as if to let you pass, and the queer-shaped Piazzetta beyond, with the flag-pole and marble balustrade. And I know that old wine-shop where the chairs and tables are drawn[31] close up to the very bridge itself, its awnings half over the last step.

My own gondolier, Espero—bless his sunny face!—knows the owner of this shop and has known her for years; a great, superb creature, with eyes that flash and smoulder under heaps of tangled black hair. He first presented me to this grand duchess of the Riva years ago, when I wanted a dish of macaroni browned on a shallow plate. Whenever I turn in now out of the heat for a glass of crushed ice and orange juice, she mentions the fact and points with pride to the old earthen platter. It is nearly burnt through with my many toastings.

But the bridge is my delight; the arch underneath is so cool, and I have darted under it so often for luncheon and half an hour’s siesta. On these occasions the old burnt-bottomed dish is brought to my gondola sizzling hot, with coffee and rolls, and sometimes a bit of broiled fish as an extra touch.

This bridge has always been the open-air club-room of the entire neighborhood,—everybody who has any lounging to do is a life member. All day long its habitués hang over it, gazing listlessly out upon the lagoon; singly, in bunches, in swarms when the fish-boats round in from Chioggia, or a[32] new P. and O. steamer arrives. Its hand-rail of marble is polished smooth by the arms and legs and blue overalls of two centuries.

There is also a very dear friend of mine living near this bridge, whom you might as well know before I take another step along the Riva. He is attached to my suite. I have a large following quite of his kind, scattered all over Venice. As I am on my way, in this chapter, to the Public Garden, and can never get past this his favorite haunt without his cheer and laugh to greet me; so I cannot, if I would, avoid bringing him in now, knowing full well that he would bring himself in and unannounced whenever it should please his Excellency so to do. He is a happy-hearted, devil-may-care young fellow, who haunts this particular vicinity, and who has his bed and board wherever, at the moment, he may happen to be. The bed problem never troubles him; a bit of sailcloth under the shadow of the hand-rail will do, or a straw mat behind the angle of a wall, or even what shade I can spare from my own white umbrella, with the hard marble flags for feathers. The item of board is a trifle, yet only a trifle, more serious. It may be a fragment of polenta, or a couple of figs,[33] or only a drink from the copper bucket of some passing girl. Quantity, quality, and time of serving are immaterial to him. There will be something to eat before night, and it always comes. One of the pleasures of the neighborhood is to share with him a bite.

This beggar, tramp, lasagnone—ragged, barefooted, and sunbrowned, would send a flutter through the hearts of a matinée full of pretty girls, could he step to the footlights just as he is, and with his superb baritone voice ring out one of his own native songs. Lying as he does now under my umbrella, his broad chest burnt almost black, the curls glistening about his forehead, his well-trimmed mustache curving around a mouth half open, shading a row of teeth white as milk, his Leporello hat thrown aside, a broad red sash girding his waist, the fine muscles of his thighs filling his overalls, these same pretty girls might perhaps only draw their skirts aside as they passed: environment plays such curious tricks.

This friend of mine, this royal pauper, Luigi, never in the recollection of any mortal man or woman was known to do a stroke of work. He lives somewhere up a crooked canal, with an old mother who adores him—as, in fact, does every other woman he knows,[34] young or old—and whose needle keeps together the rags that only accentuate more clearly the superb lines of his figure. And yet one cannot call him a burden on society. On the contrary, Luigi has especial duties which he never neglects. Every morning at sunrise he is out on the bridge watching the Chioggia boats as they beat up past the Garden trying to make the red buoy in the channel behind San Giorgio, and enlarging on their seagoing qualities to an admiring group of bystanders. At noon he is plumped down in the midst of a bevy of wives and girls, flat on the pavement, his back against a doorway in some courtyard. The wives mend and patch, the girls string beads, and the children play around on the marble flagging, Luigi monopolizing all the talk and conducting all the gayety, the whole coterie listening. He makes love, and chaffs, and sings, and weaves romances, until the inquisitive sun peeps into the patio; then he is up and out on the bridge again, and so down the Riva, with the grace of an Apollo and the air of a thoroughbred.

When I think of all the sour tempers in the world, all the people with weak backs and chests and limbs, all the dyspeptics, all the bad livers and worse hearts, all the mean[35] people and the sordid, all those who pose as philanthropists, professing to ooze sunshine and happiness from their very pores; all the down-trodden and the economical ones; all those on half pay and no work, and those on full pay and too little—and then look at this magnificent condensation of bone, muscle, and sinew; this Greek god of a tramp, unselfish, good-tempered, sunny-hearted, wanting nothing, having everything, envying nobody, happy as a lark, one continuous song all the day long; ready to catch a line, to mind a child, to carry a pail of water for any old woman, from the fountain in the Campo near by to the top of any house, no matter how high—when, I say, I think of this prince of good fellows leading his Adam-before-the-fall sort of existence, I seriously consider the advisability of my pensioning him for the remainder of his life on one lira a day, a fabulous sum to him, merely to be sure that nothing in the future will ever spoil his temper and so rob me of the ecstasy of knowing and of being always able to find one supremely happy human creature on this earth.

But, as I have said, I am on my way to the Public Garden. Everybody else is going too. Step to the marble balustrade of this three-cornered[36] Piazzetta and see if the prows of the gondolas are not all pointed that way. I am afoot, have left the Riva and am strolling down the Via Garibaldi, the widest street in Venice. There are no palaces here, only a double row of shops, their upper windows and balconies festooned with drying clothes, their doors choked with piles of fruit and merchandise. A little farther down is a marble bridge, and then the arching trees of the biggest and breeziest sweep of green in all Venice—the Giardini Pubblici—many acres in extent, bounded by a great wall surmounted by a marble balustrade more than a mile in length, and thickly planted with sycamores and flowering shrubs. Its water front commands the best view of the glory of a Venetian sunset.

This garden, for Venice, is really a very modern kind of public garden, after all. It was built in the beginning of the present century, about 1810, when the young Corsican directed one Giovanni Antonio Selva to demolish a group of monasteries incumbering the ground and from their débris to construct the foundations of this noble park, with its sea-wall, landings, and triumphal gate.

Whenever I stretch myself out under the[37] grateful shade of these splendid trees, I always forgive the Corsican for robbing San Marco of its bronze horses and for riding his own up the incline of the Campanile, and even for leveling the monasteries.

And the Venetians of to-day are grateful too, however much their ancestors may have reviled the conqueror for his vandalism. All over its graveled walks you will find them lolling on the benches, grouped about the pretty caffès, taking their coffee or eating ices; leaning by the hour over the balustrade and watching the boats and little steamers. The children romp and play, the candy man and the sellers of sweet cakes ply their trade, and the vender with cool drinks stands over his curious four-legged tray, studded with bits of brass and old coins, and calls out his several mixtures. The officers are here, too, twisting their mustachios and fingering their cigarettes; fine ladies saunter along, preceded by their babies, half smothered in lace and borne on pillows in the arms of Italian peasants with red cap-ribbons touching the ground; and barefooted, frowzy-headed girls from the rookeries behind the Arsenal idle about, four or five abreast, their arms locked, mocking the sailors and filling the air with laughter.

[38]Then there are a menagerie, or rather some wire-fenced paddocks filled with kangaroos and rabbits, and an aviary of birds, and a big casino where the band plays, and where for half a lira, some ten cents, you can see a variety performance without the variety, and hear these light-hearted people laugh to their heart’s content.

And last of all, away down at one end, near the wall fronting the church of San Giuseppe, there lives in miserable solitude the horse—the only horse in Venice. He is not always the same horse. A few years ago, when I first knew him, he was a forlorn, unkempt, lonely-looking quadruped of a dark brown color, and with a threadbare tail. When I saw him last, within the year, he was a hand higher, white, and wore a caudal appendage with a pronounced bang. Still he is the same horse—Venice never affords but one. When not at work (he gathered leaves in the old days; now I am ashamed to say he operates a lawn-mower as well), he leans his poor old tired head listlessly over the rail, refusing the cakes the children offer him. At these times he will ruminate by the hour over his unhappy lot. When the winter comes, and there are no more leaves to rake, no gravel to haul, nor grass to mow, they[39] lead him down to the gate opening on the little side canal and push him aboard a flat scow, and so on up the Grand Canal and across the lagoon to Mestre. As he passes along, looking helplessly from side to side, the gondoliers revile him and the children jeer at him, and those on the little steamboats pelt him with peach pits, cigar ends, and bits of broken coal. Poor old Rosinante, there is no page in the history of Venice which your ancestors helped glorify!

There are two landings along the front of the garden,—one below the west corner, up a narrow canal, and the other midway of the long sea-wall, where all the gondolas load and unload. You know this last landing at once. Ziem has painted it over and over again for a score of years or more, and this master of color is still at it. With him it is a strip of brilliant red, a background of autumn foliage, and a creamy flight of steps running down to a sea of deepest ultramarine. There is generally a mass of fishing-boats, too, in brilliant colorings, moored to the wall, and a black gondola for a centre dark.

When you row up to this landing to-day, you are surprised to find it all sunshine and glitter. The trees are fresh and crisp, the marble is dazzling white, and the water[40] sparkling and limpid with gray-green tints. But please do not criticise Ziem. You do not see it his way, but that is not his fault. Venice is a hundred different Venices to as many different painters. If it were not so, you would not be here to-day, nor love it as you do. Besides, when you think it all over, you will admit that Ziem, of all living painters, has best rendered its sensuous, color-soaked side. And yet, when you land you wonder why the colorist did not bring his easel closer and give you a nearer view of this superb water-landing, with the crowds of gayly dressed people, swarms of gondolas, officers, fine ladies, boatmen, and the hundred other phases of Venetian life.

But I hear Espero’s voice out on the broad water. Now I catch the sunlight on his white shirt and blue sash. He is standing erect, his whole body swaying with that long, graceful, sweeping stroke which is the envy of the young gondoliers and the despair of the old; Espero, as you know, has been twice winner in the gondola races. He sees my signal, runs his bow close in, and the next instant we are swinging back up the Grand Canal, skirting the old boatyard and the edge of the Piazzetta. A puff of smoke from the man-of-war ahead, and the roll of the[41] sunset gun booms over the water. Before the echoes have fairly died away, a long sinuous snake of employees—there are some seven thousand of them—crawls from out the arsenal gates, curves over the arsenal bridge, and heads up the Riva. On we go, abreast of the crowd, past the landing-wharf of the little steamers, past the rear porches of the queer caffès, past the man-of-war, and a moment later are off the wine-shop and my bridge. I part the curtains, and from my cushions can see the Duchess standing in the doorway, her arms akimbo, with all the awnings rolled back tight for the night. The bridge itself is smothered in a swarm of human flies, most of them bareheaded. As we sheer closer, one more ragged than the rest springs up and waves his hat. Then comes the refrain of that loveliest of all the Venetian boat songs:—

“Jammo, jammo neoppa, jammo ja.”

It is Luigi, bidding me good-night.

THERE is but one piazza in the world. There may be other splendid courts and squares, magnificent breathing spaces for the people, enriched by mosque and palace, bordered by wide-spreading trees, and adorned by noble statues. You know, of course, every slant of sunlight over the plaza of the Hippodrome, in Constantinople, with its slender twin needles of stone; you know the Puerta del Sol of Madrid, cooled by the splash of sunny fountains and alive with the rush of Spanish life; and you know, too, the royal Place de la Concorde, brilliant with the never-ending whirl of pleasure-loving Paris. Yes, you know and may love them all, and yet there is but one grand piazza the world over; and that lies to-day in front of the Church of San Marco.

It is difficult to account for this fascination. Sometimes you think it lurks in the exquisite taper of the Campanile. Sometimes you think the secret of its charm is hidden in masterly carvings, delicacy of arch, or refinement of color. Sometimes the Piazza appeals to you only as the great open-air[43] bricabrac shop of the universe, with its twin columns of stone stolen from the islands of the Archipelago; its bronze horses, church doors, and altar front wrested from Constantinople and the East; and its clusters of pillars torn from almost every heathen temple within reach of a Venetian galley.

When your eye becomes accustomed to the dazzling splendor of the surroundings, and you begin to analyze each separate feature of this Court of the Doges, you are even more enchanted and bewildered. San Marco itself no longer impresses you as a mere temple, with open portals and swinging doors; but as an exquisite jewel-case of agate and ivory, resplendent in gems and precious stones. The clock tower, with its dial of blue and gold and its figures of bronze, is not, as of old, one of a row of buildings, but a priceless ornament that might adorn the palace of some King of the Giants; while the Loggia of Sansovino could serve as a mantel for his banquet hall, and any one of the three bronze sockets of the flag-staffs, masterpieces of Leopardo, hold huge candles to light him to bed.

And behind all this beauty of form and charm of handicraft, how lurid the background[44] of tradition, cruelty, and crime! Poor Doge Francesco Foscari, condemning his own innocent son Jacopo to exile and death, in that very room overlooking the square; the traitor Marino Faliero, beheaded on the Giant Stairs of the palace, his head bounding to the pavement below; the perfidies of the Council of Ten; the state murders, tortures, and banishments; the horrors of the prisons of the Piombi; the silent death-stroke of the unsigned denunciations dropped into the Bocca del Leone—that fatal letter-box with its narrow mouth agape in the wall of stone, nightly filled with the secrets of the living, daily emptied of the secrets of the dead. All are here before you. The very stones their victims trod lie beneath your feet, their water-soaked cells but a step away.

As you pass between the twin columns of stone,—the pillars of Saint Theodore and of the Lion,—you shudder when you recall the fate of the brave Piedmontese, Carmagnola, a fate unfolding a chapter of cunning, ingratitude, and cruelty almost unparalleled in the history of Venice. You remember that for years this great hireling captain had led the armies of Venice and the Florentines against his former master, Philip of Milan;[45] and that for years Venice had idolized the victorious warrior.

You recall the disastrous expedition against Cremona, a stronghold of Philip, and the subsequent anxiety of the Senate lest the sword of the great captain should be turned against Venice herself. You remember that one morning, as the story runs, a deputation entered the tent of the great captain and presented the confidence of the Senate and an invitation to return at once to Venice and receive the plaudits of the people. Attended by his lieutenant, Gonzaga, Carmagnola set out to obey. All through the plains of Lombardy, brilliant in their gardens of olive and vine, he was received with honor and welcome. At Mestre he was met by an escort of eight gentlemen in gorgeous apparel, special envoys dispatched by the Senate, who conducted him across the wide lagoon and down the Grand Canal, to this very spot on the Molo.

On landing from his sumptuous barge, the banks ringing with the shouts of the populace, he was led by his escort direct to the palace, and instantly thrust into an underground dungeon. Thirty days later, after a trial such as only the Senate of the period would tolerate, and gagged lest his indignant[46] outcry might rebound in mutinous echoes, his head fell between the columns of San Marco.

There are other pages to which one could turn in this book of the past, pages rubricated in blood and black-lettered in crime. The book is opened here because this tragedy of Carmagnola recalls so clearly and vividly the methods and impulses of the times, and because, too, it occurred where all Venice could see, and where to-day you can conjure up for yourself the minutest details of the terrible outrage. Almost nothing of the scenery is changed. From where you stand between these fatal shafts, the same now as in the days of Carmagnola (even then two centuries old), there still hangs a balcony whence you could have caught the glance of that strong, mute warrior. Along the water’s edge of this same Molo, where now the gondoliers ply their calling, and the lasagnoni lounge and gossip, stood the soldiers of the state drawn up in solid phalanx. Across the canal, by the margin of this same island of San Giorgio—before the present church was built—the people waited in masses, silently watching the group between those two stone posts that marked for them, and for all Venice, the doorway of hell. Above[47] towered this same Campanile, all but its very top complete.

But you hurry away, crossing the square with a lingering look at this fatal spot, and enter where all these and a hundred other tragedies were initiated, the Palace of the Doges. It is useless to attempt a description of its wonderful details. If I should elaborate, it would not help to give you a clearer idea of this marvel of the fifteenth century. To those who know Venice, it will convey no new impression; to those who do not it might add only confusion and error.

Give yourself up instead to the garrulous old guide who assails you as you enter, and who, for a few lire, makes a thousand years as one day. It is he who will tell you of the beautiful gate, the Porta della Carta of Bartolommeo Bon, with its statues weather-stained and worn; of the famous Scala dei Giganti, built by Rizzo in 1485; of the two exquisitely moulded and chased bronze well-heads of the court; of the golden stairs of Sansovino; of the ante-chamber of the Council of Ten; of the great Sala di Collegio, in which the foreign ambassadors were received by the Doge; of the superb senate chamber, the Sala del Senato; of the costly marbles and marvelous carvings; of the ceilings of[48] Titian, Tintoretto, and Veronese; of the secret passages, dungeons, and torture chambers.

But the greatest of all these marvels of the Piazza still awaits you, the Church of San Marco. Dismiss the old guide outside the beautiful gate and enter its doors alone; here he would fail you.

If you come only to measure the mosaics, to value the swinging lamps, or to speculate over the uneven, half-worn pavement of the interior, enter its doors at any time, early morning or bright noonday, or whenever your practical, materialistic, nineteenth-century body would escape from the blaze of the sun outside. Or you can stay away altogether; neither you nor the world will be the loser. But if you are the kind of man who loves all beautiful things,—it may be the sparkle of early dew upon the grass, the silence and rest of cool green woods, the gloom of the fading twilight,—or if your heart warms to the sombre tones of old tapestries, armor, and glass, and you touch with loving tenderness the vellum backs of old books, then enter when the glory of the setting sun sifts in and falls in shattered shafts of light on altar, roof, and wall. Go with noiseless step and uncovered head, and,[49] finding some deep-shadowed seat or sheltered nook, open your heart and mind and soul to the story of its past, made doubly precious by the splendor of its present. As you sit there in the shadow, the spell of its exquisite color will enchant you—color mellowing into harmonies you knew not of; harmonies of old gold and porphyry reds; the dull silver of dingy swinging lamps, with the soft light of candles and the dreamy haze of dying incense; harmonies of rich brown carvings and dark bronzes rubbed bright by a thousand reverent hands.

The feeling which will steal over you will not be one of religious humility, like that which took possession of you in the Saint Sophia of Constantinople. It will be more like the blind idolatry of the pagan, for of all the temples of the earth, this shrine of San Marco is the most worthy of your devotion. Every turn of the head will bring new marvels into relief; marvels of mosaic, glinting like beaten gold; marvels of statue, crucifix, and lamp; marvels of altars, resplendent in burnished silver and flickering tapers; of alabaster columns merging into the vistas; of sculptured saint and ceiling of sheeted gold; of shadowy aisle and high uplifted cross.

[50]Never have you seen any such interior. Hung with the priceless fabrics and relics of the earth, it is to you one moment a great mosque, studded with jewels and rich with the wealth of the East; then, as its color deepens, a vast tomb, hollowed from out a huge, dark opal, in which lies buried some heroic soul, who in his day controlled the destinies of nations and of men. And now again, when the mystery of its light shimmers through windows covered with the dust of ages, there comes to this wondrous shrine of San Marco, small as it is, something of the breadth and beauty, the solitude and repose, of a summer night.

When the first hush and awe and sense of sublimity have passed away, you wander, like the other pilgrims, into the baptistery; or you move softly behind the altar, marveling over each carving of wood and stone and bronze; or you descend to the crypt and stand by the stone sarcophagus that once held the bones of the good saint himself.

As you walk about these shadowy aisles, and into the dim recesses, some new devotee swings back a door, and a blaze of light streams in, and you awake to the life of to-day.

Yes, there is a present as well as a past.[51] There is another Venice outside; a Venice of life and joyousness and stir. The sun going down; the caffès under the arcades of the King’s Palace and of the Procuratie Vecchie are filling up. There is hardly an empty table at Florian’s. The pigeons, too, are coming home to roost, and are nestling under the eaves of the great buildings and settling on the carvings of San Marco. The flower girls, in gay costumes, are making shops of the marble benches next the Campanile, assorting roses and pinks, and arranging their boutonnières for the night’s sale. The awnings which have hung all day between the columns of the arcades are drawn back, exposing the great line of shops fringing three sides of the square. Lights begin to flash; first in the clusters of lamps illuminating the arcades, and then in the windows filled with exquisite bubble-blown Venetian glass, wood carvings, inlaid cabinets, cheap jewelry, gay-colored photographs and prints.

As the darkness falls, half a dozen men drag to the centre of the Piazza the segments of a great circular platform. This they surround with music-rests and a stand for the leader. Now the pavement of the Piazza itself begins filling up. Out from the Merceria, from under the clock tower, pours a[52] steady stream of people merging in the crowds about the band-stand. Another current flows in through the west entrance, under the Bocca di Piazza, and still another from under the Riva, rounding the Doges’ Palace. At the Molo, just where poor Carmagnola stepped ashore, a group of officers—they are everywhere in Venice—land from a government barge. These are in full regalia, even to their white kid gloves, their swords dangling and ringing as they walk. They, too, make their way to the square and fill the seats around one of the tables at Florian’s, bowing magnificently to the old Countess who sits just inside the door of the caffè itself, resplendent, as usual, in dyed wig and rose-colored veil. She is taking off her long, black, fingerless silk gloves, and ordering her customary spoonful of cognac and lump of sugar. Gustavo, the head waiter, listens as demurely as if he expected a bottle of Chablis at least, with the customary commission for Gustavo—but then Gustavo is the soul of politeness. Some evil-minded people say the Countess came in with the Austrians; others, more ungallant, date her advent about the days of the early doges.

By this time you notice that the old French professor is in his customary place;[53] it is outside the caffè, in the corridor, on a leather-covered, cushioned seat against one of the high pillars. You never come to the Piazza without meeting him. He is as much a part of its history as the pigeons, and, like them, dines here at least once a day. He is a perfectly straight, pale, punctilious, and exquisitely deferential relic of a by-gone time, whose only capital is his charming manner and his thorough knowledge of Venetian life. This combination rarely fails where so many strangers come and go; and then, too, no one knows so well the intricacies of an Italian kitchen as Professor Croisac.

Sometimes on summer evenings he will move back a chair at your own table and insist upon dressing the salad. Long before his greeting, you catch sight of him gently edging his way through the throng, the seedy, straight-brimmed silk hat in his hand brushed with the greatest precision; his almost threadbare frock-coat buttoned snug around his waist, the collar and tails flowing loose, his one glove hanging limp. He is so erect, so gentle, so soft-voiced, so sincere, and so genuine, and for the hour so supremely happy, that you cannot divest yourself of the idea that he really is an old marquis, temporarily exiled from some faraway[54] court, and to be treated with the greatest deference. When, with a little start of sudden surprise, he espies some dark-eyed matron in the group about him, rises to his feet and salutes her as if she were the Queen of Sheba, you are altogether sure of his noble rank. Then the old fellow regains his seat, poises his gold eyeglasses—a relic of better days—between his thumb and forefinger, holds them two inches from his nose, and consults the menu with the air of a connoisseur.

Before your coffee is served the whole Piazza is ablaze and literally packed with people. The tables around you stand quite out to the farthest edge permitted. (These caffès have, so to speak, riparian rights—so much piazza seating frontage, facing the high-water mark of the caffè itself.) The waiters can now hardly wedge their way through the crowd. The chairs are so densely occupied that you barely move your elbows. Next you is an Italian mother—full-blown even to her delicate mustache—surrounded by a bevy of daughters, all in pretty hats and white or gay-colored dresses, chatting with a circle of still other officers. All over the square, where earlier in the day only a few stray pilgrims braved the heat, or[55] a hungry pigeon wandered in search of a grain of corn, the personnel of this table is repeated—mothers and officers and daughters, and daughters and officers and mothers again.

Outside this mass, representing a clientèle possessing at least half a lira each—one cannot, of course, occupy a chair and spend less, and it is equally difficult to spend very much more—there moves in a solid mass the rest of the world: bareheaded girls, who have been all day stringing beads in some hot courtyard; old crones in rags from below the shipyards; fishermen in from Chioggia; sailors, stevedores, and soldiers in their linen suits, besides sight-seers and wayfarers from the four corners of the earth.

If there were nothing else in Venice but the night life of this grand Piazza, it would be worth a pilgrimage half across the world to see. Empty every café in the Boulevards; add all the habitués of the Volks Gardens of Vienna, and all those you remember at Berlin, Buda-Pesth, and Florence; pack them in one mass, and you would not half fill the Piazza. Even if you did, you could never bring together the same kinds of people. Venice is not only the magnet that draws the idler and the sight-seer, but those who love her just because she is Venice—painters,[56] students, architects, historians, musicians, every soul who values the past and who finds here, as nowhere else, the highest achievement of chisel, brush, and trowel.

The painters come, of course—all kinds of painters, for all kinds of subjects. Every morning, all over the canals and quays, you find a new growth of white umbrellas, like mushrooms, sprung up in the night. Since the days of Canaletto these men have painted and repainted these same stretches of water, palace, and sky. Once under the spell of her presence, they are never again free from the fascinations of this Mistress of the Adriatic. Many of the older men are long since dead and forgotten, but the work of those of to-day you know: Ziem first, nearly all his life a worshiper of the wall of the Public Garden; and Rico and Ruskin and Whistler. Their names are legion. They have all had a corner at Florian’s. No matter what their nationality or specialty, they speak the common language of the brush. Old Professor Croisac knows them all. He has just risen again to salute Marks, a painter of sunrises, who has never yet recovered from his first thrill of delight when early one morning his gondolier rowed him down the lagoon and made fast to a cluster of spiles off the Public[57] Garden. When the sun rose behind the sycamores and threw a flood of gold across the sleeping city, and flashed upon the sails of the fishing-boats drifting up from the Lido, Marks lost his heart. He is still tied up every summer to that same cluster of spiles, painting the glory of the morning sky and the drifting boats. He will never want to paint anything else. He will not listen to you when you tell him of the sunsets up the Giudecca, or the soft pearly light of the dawn silvering the Salute, or the picturesque life of the fisher-folk of Malamocco.

“My dear boy,” he breaks out, “get up to-morrow morning at five and come down to the Garden, and just see one sunrise—only one. We had a lemon-yellow and pale emerald sky this morning, with dabs of rose-leaves, that would have paralyzed you.”

Do not laugh at the painter’s enthusiasm. This white goddess of the sea has a thousand lovers, and, like all other lovers the world over, each one believes that he alone holds the key to her heart.

YOU think, perhaps, there are no gardens in Venice; that it is all a sweep of palace front and shimmering sea; that save for the oleanders bursting into bloom near the Iron Bridge, and the great trees of the Public Garden shading the flower-bordered walks, there are no half-neglected tangles where rose and vine run riot; where the plash of the fountain is heard in the stillness of the night, and tall cedars cast their black shadows at noonday.

Really, if you but knew it, almost every palace hides a garden nestling beneath its balconies, and every high wall hems in a wealth of green, studded with broken statues, quaint arbors festooned with purple grapes, and white walks bordered by ancient box; while every roof that falls beneath a window is made a hanging garden of potted plants and swinging vines.

BEYOND SAN ROSARIO

Step from your gondola into some open archway. A door beyond leads you to a court paved with marble flags and centred by a well with carved marble curb, yellow stained with age. Cross this wide court,[59] pass a swinging iron gate, and you stand under rose-covered bowers, where in the olden time gay gallants touched their lutes and fair ladies listened to oft-told tales of love.

And not only behind the palaces facing the Grand Canal, but along the Zattere beyond San Rosario, away down the Giudecca, and by the borders of the lagoon, will you find gay oleanders flaunting red blossoms, and ivy and myrtle hanging in black-green bunches over crumbling walls.

In one of these hidden nooks, these abandoned cloisters of shaded walk and over-bending blossom, I once spent an autumn afternoon with my old friend, the Professor,—“Professor of Modern Languages and Ancient Legends,” as some of the more flippant of the habitués of Florian’s were wont to style him. The old Frenchman had justly earned this title. He had not only made every tradition and fable of Venice his own, often puzzling and charming the Venetians themselves with his intimate knowledge of the many romances of their past, but he could tell most wonderful tales of the gorgeous fêtes of the seventeenth century, the social life of the nobility, their escapades, intrigues, and scandals.

[60]If some fair Venetian had loved not wisely but too well, and, clinging to brave Lorenzo’s neck, had slipped down a rope ladder into a closely curtained, muffled-oared gondola, and so over the lagoon to Mestre, the old Frenchman could not only point out to you the very balcony, provided it were a palace balcony and not a fisherman’s window,—he despised the bourgeoisie,—but he could give you every feature of the escapade, from the moment the terror-stricken duenna missed her charge to that of the benediction of the priest in the shadowed isle. So, when upon the evening preceding this particular day, I accepted the Professor’s invitation to breakfast, I had before me not only his hospitality, frugal as it might be, but the possibility of drawing upon his still more delightful fund of anecdote and reminiscence.

Neither the day nor the hour had been definitely set. The invitation, I afterwards discovered, was but one of the many he was constantly giving to his numerous friends and haphazard acquaintances, evincing by its perfect genuineness his own innate kindness and his hearty appreciation of the many similar courtesies he was daily receiving at their hands. Indeed, to a man so delicately adjusted as the Professor and so entirely poor,[61] it was the only way he could balance, in his own mind, many long-running accounts of, coffee for two at the Calcina, with a fish and a fruit salad, the last a specialty of the Professor’s—the oil, melons, and cucumbers being always provided by his host—or a dish of risotto, with kidneys and the like, at the Bauer-Grünwald.

Nobody ever accepted these invitations seriously, that is, no one who knew the Professor at all well. In fact, there was a general impression existing among the many frequenters of Florian’s and the Quadri that the Professor’s hour and place of breakfasting were very like the birds’—whenever the unlucky worm was found, and wherever the accident happened to occur. When I asked Marks for the old fellow’s address—which rather necessary item I remembered later had also been omitted by the Professor—he replied, “Oh, somewhere down the Riva,” and dropped the subject as too unimportant for further mental effort.

All these various eccentricities of my prospective host, however, were at the time unknown to me. He had cordially invited me to breakfast—“to-morrow, or any day you are near my apartments, I would be so charmed,” etc. I had as graciously accepted,[62] and it would have been unpardonable indifference, I felt sure, not to have continued the inquiries until my hand touched his latch-string.

The clue was a slight one. I had met him once, leaning over the side of the bridge below Danieli’s, the Ponte del Sepolcro, looking wistfully out to sea, and was greeted with the remark that he had that moment left his apartments, and only lingered on the bridge to watch the play of silvery light on the lagoon, the September skies were so enchanting. So on this particular morning I began inspecting the bell-pulls of all the doorways, making inquiry at the several caffès and shops. Then I remembered the apothecary, down one step from the sidewalk, in the Via Garibaldi—a rather shabby continuation of the Riva—and nearly a mile below the more prosperous quarter where the Professor had waved his hand, the morning I met him on the bridge.

“The Signor Croisac—the old Frenchman?” “Upstairs, next door.”

He was as delightful as ever in his greetings; started a little when I reminded him of his invitation, but begged me to come in and sit down, and with great courtesy pointed out the view of the garden below, and the[63] sweep and glory of the lagoon. Then he excused himself, adjusted his hat, picked up a basket, and gently closed the door.

The room, upon closer inspection, was neither dreary nor uninviting. It had a sort of annex, or enlarged closet, with a drawn curtain partly concealing a bed, a row of books lining one wall, a table littered with papers, a smaller one containing a copper coffee-pot and a scant assortment of china, some old chairs, and a disemboweled lounge that had doubtless lost heart in middle life and committed hari-kari. There were also a few prints and photographs, a corner of the Parthenon, a mezzo of Napoleon in his cocked hat, and an etching or two, besides a miniature reduction of the Dying Gladiator, which he used as a paper-weight. All the windows of this modest apartment were filled with plants, growing in all kinds of pots and boxes, broken pitchers, cracked dishes—even half of a Chianti flask. These, like their guardian, ignored their surroundings and furnishings, and flamed away as joyously in the summer sun as if they had been nurtured in the choicest of majolica.

He was back before I had completed my inventory, thanking me again and again for my extreme kindness in coming, all the[64] while unwrapping the Gorgonzola, and flecking off with a fork the shreds of paper that still clung to its edges. The morsel was then laid upon a broad leaf gathered at the window, and finally upon a plate covered by a napkin so that the flies should not taste it first. This, with a simple salad, a pot of coffee and some rolls, a siphon of seltzer and a little raspberry juice in a glass,—“so much fresher than wine these hot mornings,” he said,—constituted the entire repast.

But there was no apology offered with the serving. Poor as he was, he had that exquisite tact which avoided burdening his guest even with his economies. He had offered me all his slender purse could afford. Indeed, the cheese had quite overstrained it.