Transcriber’s Note:

New original cover art included with this eBook is granted to the public domain.

This little volume is an attempt at a brief exposition of the philosophical and religious doctrines found in Patañjali’s Yoga-sūtra as explained by its successive commentaries of Vyāsa, Vācaspati, Vijñāna Bhikshu, and others. The exact date of Patañjali cannot be definitely ascertained, but if his identity with the other Patañjali, the author of the Great Commentary (Mahābhāshya) on Pāṇini’s grammar, could be conclusively established, there would be some evidence in our hands that he lived in 150 B.C. I have already discussed this subject in the first volume of my A History of Indian Philosophy, where the conclusion to which I arrived was that, while there was some evidence in favour of their identity, there was nothing which could be considered as being conclusively against it. The term Yoga, according to Patañjali’s definition, means the final annihilation (nirodha) of all the mental states (cittavṛtti) involving the preparatory stages in which the mind has to be habituated to being steadied into particular types of graduated mental states. This was actually practised in India for a long time before Patañjali lived; and it is very probable that certain philosophical, psychological, and practical doctrines associated with it were also current long before Patañjali. Patañjali’s work is, however, the earliest systematic compilation on the subject that is known to us. It is impossible, at this distance of time, to determine viiithe extent to which Patañjali may claim originality. Had it not been for the labours of the later commentators, much of what is found in Patañjali’s aphorisms would have remained extremely obscure and doubtful, at least to all those who were not associated with such ascetics as practised them, and who derived the theoretical and practical knowledge of the subject from their preceptors in an upward succession of generations leading up to the age of Patañjali, or even before him. It is well to bear in mind that Yoga is even now practised in India, and the continuity of traditional instruction handed down from teacher to pupil is not yet completely broken.

If anyone wishes methodically to pursue a course which may lead him ultimately to the goal aimed at by Yoga, he must devote his entire life to it under the strict practical guidance of an advanced teacher. The present work can in no sense be considered as a practical guide for such purposes. But it is also erroneous to think—as many uninformed people do—that the only interest of Yoga lies in its practical side. The philosophical, psychological, cosmological, ethical, and religious doctrines, as well as its doctrines regarding matter and change, are extremely interesting in themselves, and have a definitely assured place in the history of the progress of human thought; and, for a right understanding of the essential features of the higher thoughts of India, as well as of the practical side of Yoga, their knowledge is indispensable.

The Yoga doctrines taught by Patañjali are regarded as the highest of all Yogas (Rājayoga), as distinguished from other types of Yoga practices, such as Haṭhayoga or Mantrayoga. ixOf these Haṭhayoga consists largely of a system of bodily exercises for warding off diseases, and making the body fit for calmly bearing all sorts of physical privations and physical strains. Mantrayoga is a course of meditation on certain mystical syllables which leads to the audition of certain mystical sounds. This book does not deal with any of these mystical practices nor does it lay any stress on the performance of any of those miracles described by Patañjali. The scope of this work is limited to a brief exposition of the intellectual foundation—or the theoretical side—of the Yoga practices, consisting of the philosophical, psychological, cosmological, ethical, religious, and other doctrines which underlie these practices. The affinity of the system of Sāṃkhya thought, generally ascribed to a mythical sage, Kapila, to that of Yoga of Patañjali is so great on most important points of theoretical interest that they may both be regarded as two different modifications of one common system of ideas. I have, therefore, often taken the liberty of explaining Yoga ideas by a reference to kindred ideas in Sāṃkhya. But the doctrines of Yoga could very well have been compared or contrasted with great profit with the doctrines of other systems of Indian thought. This has purposely been omitted here as it has already been done by me in my Yoga Philosophy in relation to other Systems of Indian Thought, the publication of which has for long been unavoidably delayed. All that may be expected from the present volume is that it will convey to the reader the essential features of the Yoga system of thought. How far this expectation will be realized from this book it will be for my readers to judge. It is hoped that the xchapter on “Kapila and Pātañjala School of Sāṃkhya” in my A History of Indian Philosophy (Vol. I. Cambridge University Press, 1922) will also prove helpful for the purpose.

I am deeply indebted to my friend Mr. Douglas Ainslie for the numerous corrections and suggestions regarding the English style that he was pleased to make throughout the body of the manuscript and the very warm encouragement that he gave me for the publication of this work. In this connection I also beg to offer my best thanks for the valuable suggestions which I received from the reviser of the press. Had it not been for these, the imperfections of the book would have been still greater. The quaintness and inelegance of some of my expressions would, however, be explained if it were borne in mind that here, as well as in my A History of Indian Philosophy, I have tried to resist the temptation of making the English happy at the risk of sacrificing the approach to exactness of the philosophical sense; and many ideas of Indian philosophy are such that an exact English rendering of them often becomes hopelessly difficult.

I am grateful to my friend and colleague, Mr. D. K. Sen, M.A., for the kind assistance that he rendered in helping me to prepare the index.

Last of all, I must express my deep sense of gratefulness to Sir Ashutosh Mookerjee, Kt., C.S.I., etc. etc., and the University of Calcutta, for kindly permitting me to utilize my A Study of Patañjāli, which is a Calcutta University publication, for the present work.

| BOOK I. YOGA METAPHYSICS: | ||

| CHAPTER | PAGE | |

|---|---|---|

| I. | Prakṛti | 1 |

| II. | Purusha | 13 |

| III. | The Reality of the External World | 31 |

| IV. | The Process of Evolution | 40 |

| V. | The Evolution of the Categories | 48 |

| VI. | Evolution and Change of Qualities | 64 |

| VII. | Evolution and God | 84 |

| BOOK II. YOGA ETHICS AND PRACTICE: | ||

| VIII. | Mind and Moral States | 92 |

| IX. | The Theory of Karma | 102 |

| X. | The Ethical Problem | 114 |

| XI. | Yoga Practice | 124 |

| XII. | The Yogāṅgas | 132 |

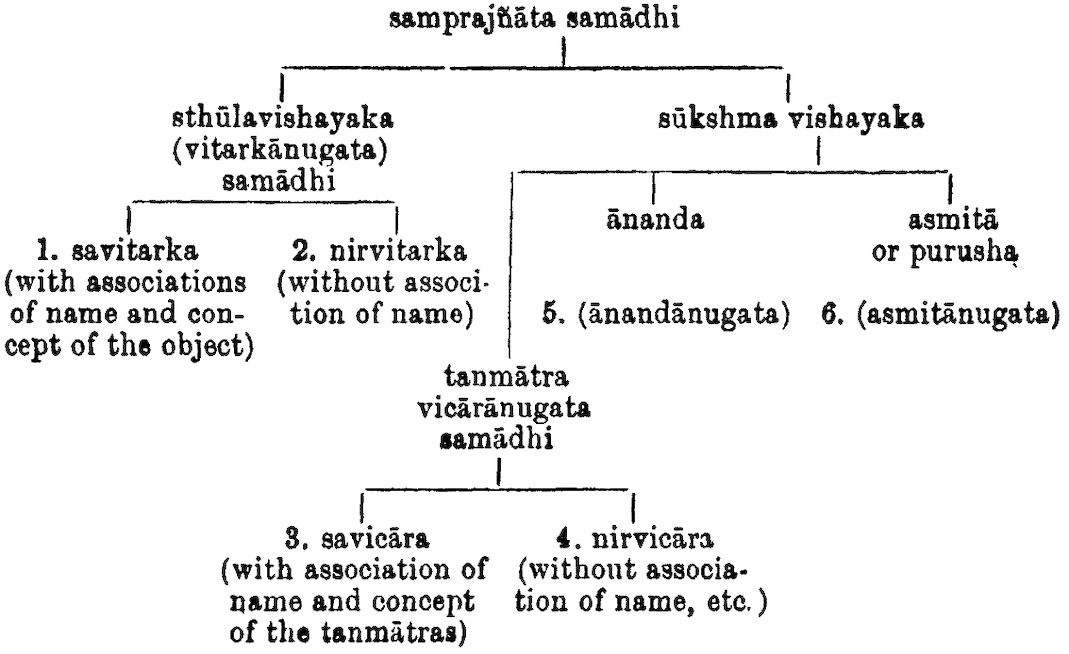

| XIII. | Stages of Samadhi | 150 |

| XIV. | God in Yoga | 159 |

| XV. | Matter and Mind | 166 |

| Appendix | 179 | |

| Index | 188 | |

However dogmatic a system of philosophical enquiry may appear to us, it must have been preceded by a criticism of the observed facts of experience. The details of the criticism and the processes of self-argumentation by which the thinker arrived at his theory of the Universe might indeed be suppressed, as being relatively unimportant, but a thoughtful reader would detect them as lying in the background behind the shadow of the general speculations, but at the same time setting them off before our view. An Aristotle or a Patañjali may not make any direct mention of the arguments which led him to a dogmatic assertion of his theories, but for a reader who intends to understand them thoroughly it is absolutely necessary that he should read them in the light as far as possible of the inferred presuppositions and inner arguments of their minds; it is in this way alone that he can put himself in the same line of thinking with the thinker whom he is willing to follow, and can grasp him to the fullest extent. In offering this short study of the Pātañjala metaphysics, I shall therefore try to supplement it with such of my inferences 2of the presuppositions of Patañjali’s mind, which I think will add to the clearness of the exposition of his views, though I am fully alive to the difficulties of making such inferences about a philosopher whose psychological, social, religious and moral environments differed so widely from ours.

An enquiry into the relations of the mental phenomena to the physical has sometimes given the first start to philosophy. The relation of mind to matter is such an important problem of philosophy that the existing philosophical systems may roughly be classified according to the relative importance that has been attached to mind or to matter. There have been chemical, mechanical and biological conceptions which have ignored mind as a separate entity and have dogmatically affirmed it to be the product of matter only.[1] There have been theories of the other extreme, which have dispensed with matter altogether and have boldly affirmed that matter as such has no reality at all, and that thought is the only thing which can be called Real in the highest sense. All matter as such is non-Being or Māyā or Avidyā. There have been Nihilists like the Śūnyavādi Buddhists who have gone so far as to assert that neither matter nor mind exists. Some have asserted that matter is only thought externalized, some have regarded the principle of matter as the unknowable Thing-in-itself, some have regarded them as separate independent entities held within a higher reality called God, or as two of his attributes only, and some have regarded their difference as being only one of grades of intelligence, one merging slowly and imperceptibly into the other and held together in concord with each other by pre-established harmony.

Underlying the metaphysics of the Yoga system of thought as taught by Patañjali and as elaborated by his commentators we find an acute analysis of matter and thought. Matter 3on the one hand, mind, the senses, and the ego on the other are regarded as nothing more than two different kinds of modifications of one primal cause, the Prakṛti. But the self-intelligent principle called Purusha (spirit) is distinguished from them. Matter consists only of three primal qualities or rather substantive entities, which he calls the Sattva or intelligence-stuff, Rajas or energy, and Tamas—the factor of obstruction or mass or inertia. It is extremely difficult truly to conceive of the nature of these three kinds of entities or Guṇas, as he calls them, when we consider that these three elements alone are regarded as composing all phenomena, mental and physical. In order to comprehend them rightly it will be necessary to grasp thoroughly the exact relation between the mental and the physical. What are the real points of agreement between the two? How can the same elements be said to behave in one case as the conceiver and in the other case as the conceived? Thus Vācaspati says:—

“The reals (guṇas) have two forms, viz. the determiner or the perceiver, and the perceived or the determined. In the aspect of the determined or the perceived, the guṇas evolve themselves as the five infra-atomic potentials, the five gross elements and their compounds. In the aspect of perceiver or determiner, they form the modifications of the ego together with the senses.”[2]

It is interesting to notice here the two words used by Vācaspati in characterising the twofold aspect of the guṇa viz. vyavasāyātmakatva, their nature as the determiner or perceiver, and vyavaseyātmakatva, their nature as determined or perceived. The elements which compose the phenomena of the objects of perception are the same as those which form the phenomena of the perceiving; their only distinction is that one is the determined and the other is the determiner. What we call the psychosis involving intellection, sensing and 4the ego, and what may be called the infra-atoms, atoms and their combinations, are but two different types of modifications of the same stuff of reals. There is no intrinsic difference in nature between the mental and the physical.

The mode of causal transformation is explained by Vijñāna Bhikshu in his commentary on the system of Sāṃkhya as if its functions consisted only in making manifest what was already there in an unmanifested form. Thus he says, “just as the image already existing in the stone is only manifested by the activity of the statuary, so the causal activity also generates only that activity by which an effect is manifested as if it happened or came into being at the present moment.”[3] The effects are all always existent, but some of them are sometimes in an unmanifested state. What the causal operation, viz. the energy of the agent and the suitable collocating instruments and conditions, does is to set up an activity by which the effect may be manifested at the present moment.

With Sāṃkhya-Yoga, sattva, rajas and tamas are substantive entities which compose the reality of the mental and the physical.[4] The mental and the physical represent two different orders of modifications, and one is not in any way superior to the other. As the guṇas conjointly form the manifold 5without, by their varying combinations, as well as all the diverse internal functions, faculties and phenomena, they are in themselves the absolute potentiality of all things, mental and physical. Thus Vyāsa in describing the nature of the knowable, writes: “The nature of the knowable is now described:—The knowable, consisting of the objects of enjoyment and liberation, as the gross elements and the perceptive senses, is characterised by three essential traits—illumination, energy and inertia. The sattva is of the nature of illumination. Rajas is of the nature of energy. Inertia (tamas) is of the nature of inactivity. The guṇa entities with the above characteristics are capable of being modified by mutual influence on one another, by their proximity. They are evolving. They have the characteristics of conjunction and separation. They manifest forms by one lending support to the others by proximity. None of these loses its distinct power into those of the others, even though any one of them may exist as the principal factor of a phenomenon with the others as subsidiary thereto. The guṇas forming the three classes of substantive entities manifest themselves as such by their similar kinds of power. When any one of them plays the rôle of the principal factor of any phenomenon, the others also show their presence in close contact. Their existence as subsidiary energies of the principal factor is inferred by their distinct and independent functioning, even though it be as subsidiary qualities.”[5] The Yoga theory does not acknowledge qualities as being different from substances. The ultimate substantive entities are called guṇas, which as we have seen are of three kinds. The guṇa entities are infinite in number; each has an individual existence, but is always acting in co-operation with others. They may be divided into three classes in accordance with their similarities 6of behaviour (śīla). Those which behave in the way of intellection are called sattva, those which behave in the way of producing effort of movement are called rajas, and those which behave differently from these and obstruct their process are called tamas. We have spoken above of a primal cause prakṛti. But that is not a separate category independent of the guṇas. Prakṛti is but a name for the guṇa entities when they exist in a state of equilibrium. All that exists excepting the purushas are but the guṇa entities in different kinds of combination amongst themselves. The effects they produce are not different from them but it is they themselves which are regarded as causes in one state and effects in another. The difference of combination consists in this, that in some combinations there are more of sattva entities than rajas or tamas, and in others more of rajas or more of tamas. These entities are continually uniting and separating. But though they are thus continually dividing and uniting in new combinations the special behaviour or feature of each class of entities remains ever the same. Whatever may be the nature of any particular combination the sattva entities participating in it will retain their intellective functions, rajas their energy functions, and tamas the obstructing ones. But though they retain their special features in spite of their mutual difference they hold fast to one another in any particular combination (tulyajātīyātulyajātīyaśaktibhedānupātinaḥ, which Bhikshu explains as aviśesheṇopashṭambhakasvabhāvāḥ). In any particular combination it is the special features of those entities which predominate that manifest themselves, while the other two classes lend their force in drawing the minds of perceivers to it as an object as a magnet draws a piece of iron. Their functionings at this time are undoubtedly feeble (sūkshmavṛttimantaḥ) but still they do exist.[6]

In the three guṇas, none of them can be held as the goal 7of the others. All of them are equally important, and the very varied nature of the manifold represents only the different combinations of these guṇas as substantive entities. In any combination one of the guṇas may be more predominant than the others, but the other guṇas are also present there and perform their functions in their own way. No one of them is more important than the other, but they serve conjointly one common purpose, viz. the experiences and the liberation of the purusha, or spirit. They are always uniting, separating and re-uniting again and there is neither beginning nor end of this (anyonyamithunāḥ sarvve naishāmādisamprayogo viprayogo vā upalabhyate).

They have no purpose of their own to serve, but they all are always evolving, as Dr. Seal says, “ever from a relatively less differentiated, less determinate, less coherent whole, to a relatively more differentiated, more determinate, more coherent whole”[7] for the experiences and liberation of purusha, or spirit. When in a state of equilibrium they cannot serve the purpose of the purusha, so that state of the guṇas is not for the sake of the purusha; it is its own independent eternal state. All the other three stages of evolution, viz. the liṅga (sign), aviśesha (unspecialised) and viśesha (specialised) have been caused for the sake of the purusha.[8] Thus Vyāsa writes:—[9] “The objects of the purusha are no cause of the original state (aliṅga). That is to say, the fulfilment of the objects of the purusha is not the cause which brings about the manifestation of the original state of prakṛti in the beginning. The fulfilment of the objects of the purusha is not therefore the reason of the existence of that ultimate state. Since it is not brought into existence by the need of the fulfilment of the purusha’s objects it is said to be eternal. As to the three 8specialised states, the fulfilment of the objects of the purusha becomes the cause of their manifestation in the beginning. The fulfilment of the objects of the purusha is not therefore the reason for the existence of the cause. Since it is not brought into existence by the purusha’s objects it is said to be eternal. As to the three specialised states, the fulfilment of the objects of the purusha being the cause of their manifestation in the beginning, they are said to be non-eternal.”

Vācaspati again says:—“The fulfilment of the objects of the purusha could be said to be the cause of the original state, if that state could bring about the fulfilment of the objects of the purusha, such as the enjoyment of sound, etc., or manifest the discrimination of the distinction between true self and other phenomena. If however it did that, it could not be a state of equilibrium,” (yadyaliṅgāvasthā śabdādyupabhogam vā sattvapurushānyatākhyātim vā purushārtham nirvarttayet tannrvarttane hi na sāmyavasthā syāt). This state is called the prakṛti. It is the beginning, indeterminate, unmediated and undetermined. It neither exists nor does it not exist, but is the principium of almost all existence. Thus Vyāsa describes it as “the state which neither is nor is not; that which exists and yet does not; that in which there is no non-existence; the unmanifested, the noumenon (lit. without any manifested indication), the background of all” (niḥsattāsattam niḥsadasat nirasat avyaktam aliṅgam pradhānam).[10] Vācaspati explains it as follows:—“Existence consists in possessing the capacity of effecting the fulfilment of the objects of the purusha. Non-existence means a mere imaginary trifle (e.g. the horn of a hare).” It is described as being beyond both these states of existence and non-existence. The state of the equipoise of the three guṇas of intelligence-stuff, inertia and energy, is nowhere of use in fulfilling the objects of the purusha. It 9therefore does not exist as such. On the other hand, it does not admit of being rejected as non-existent like an imaginary lotus of the sky. It is therefore not non-existent. But even allowing the force of the above arguments about the want of phenomenal existence of prakṛti on the ground that it cannot serve the objects of the purusha, the difficulty arises that the principles of Mahat, etc., exist in the state of the unmanifested also, because nothing that exists can be destroyed; and if it is destroyed, it cannot be born again, because nothing that does not exist can be born; it follows therefore that since the principles of mahat, etc., exist in the state of the unmanifested, that state can also affect the fulfilment of the objects of the purusha. How then can it be said that the unmanifested is not possessed of existence? For this reason, he describes it as that in which it exists and does not exist. This means that the cause exists in that state in a potential form but not in the form of the effect. Although the effect exists in the cause as mere potential power, yet it is incapable of performing the function of fulfilling the objects of the purusha; it is therefore said to be non-existent as such. Further he says that this cause is not such, that its effect is of the nature of hare’s horn. It is beyond the state of non-existence, that is, of the existence of the effect as mere nothing. If it were like that, then it would be like the lotus of the sky and no effect would follow.[11]

But as Bhikshu points out (Yoga-vārttika, II. 18) this prakṛti is not simple substance, for it is but the guṇa reals. It is simple only in the sense that no complex qualities are manifested in it. It is the name of the totality of the guṇa reals existing in a state of equilibrium through their mutual counter opposition. It is a hypothetical state of the guṇas preceding the states in which they work in mutual co-operation for the creation of the cosmos for giving the purushas 10a chance for ultimate release attained through a full enjoyment of experiences. Some European scholars have often asked me whether the prakṛti were real or whether the guṇas were real. This question, in my opinion, can only arise as a result of confusion and misapprehension, for it is the guṇas in a state of equilibrium that are called prakṛti. Apart from guṇas there is no prakṛti (guṇā eva prakṛtiśabdavācyā na tu tadatiriktā prakṛtirasti. Yoga-vārttika, II. 18). In this state, the different guṇas only annul themselves and no change takes place, though it must be acknowledged that the state of equipoise is also one of tension and action, which, however, being perfectly balanced does not produce any change. This is what is meant by evolution of similars (adṛśapariṇāma). Prakṛti as the equilibrium of the three guṇas is the absolute ground of all the mental and phenomenal modifications—pure potentiality.

Veṅkaṭa, a later Vaishṇava writer, describes prakṛti as one ubiquitous, homogeneous matter which evolves itself into all material productions by condensation and rarefaction. In this view the guṇas would have to be translated as three different classes of qualities or characters, which are found in the evolutionary products of the prakṛti. This will of course be an altogether different view of the prakṛti from that which is described in the Vyāsa-bhāshya, and the guṇas could not be considered as reals or as substantive entities in such an interpretation. A question arises, then, as to which of these two prakṛtis is the earlier conception. I confess that it is difficult to answer it. For though the Vaishṇava view is elaborated in later times, it can by no means be asserted that it had not quite as early a beginning as 2nd or 3rd century B.C. If Ahirbudhnyasamhitā is to be trusted then the Shashṭitantraśāstra which is regarded as an authoritative Sāṃkhya work is really a Vaishṇava work. Nothing can be definitely stated about the nature of prakṛti in Sāṃkhya from the 11meagre statement of the Kārikā. The statement in the Vyāsa-bhāshya is, however, definitely in favour of the interpretation that we have adopted, and so also the Sāṃkhya-sūtra, which is most probably a later work. Caraka’s account of prakṛti does not seem to be the prakṛti of Vyāsa-bhāshya for here the guṇas are not regarded as reals or substantive entities, but as characters, and prakṛti is regarded as containing its evolutes, mahat, etc., as its elements (dhātu). If Caraka’s treatment is the earliest view of Sāṃkhya that is available to us, then it has to be admitted that the earliest Sāṃkhya view did not accept prakṛti as a state of the guṇas, or guṇas as substantive entities. But the Yoga-sūtra, II. 19, and the Vyāsa-bhāshya support the interpretation that I have adopted here, and it is very curious that if the Sāṃkhya view was known at the time to be so different from it, no reference to it should have been made. But whatever may be the original Sāṃkhya view, both the Yoga view and the later Sāṃkhya view are quite in consonance with my interpretation.

In later Indian thinkers there had been a tendency to make a compromise between the Vedānta and Sāṃkhya doctrines and to identify prakṛti with the avidyā of the Vedāntists. Thus Lokācāryya writes:—“It is called prakṛti since it is the source of all change, it is called avidyā since it is opposed to knowledge, it is called māyā since it is the cause of diversion creation (prakṛtirityucyate vikārotpādakatvāt avidyā jñānavirodhitvāt māyā vicitrasṛshṭikaratvāt).”[12] But this is distinctly opposed to the Vyāsa-bhāshya which defines avidyā as vidyāviparītaṃ jñānāntaraṃ avidyā, i.e. avidyā is that other knowledge which is opposed to right knowledge. In some of the Upanishads, Svetāśvatara for example, we find that māyā and prakṛti are identified and the great god is said to preside over them (māyāṃ tu prakṛtiṃ vidyāt māyinaṃ tumaheśvaraṃ). There is a description also in the Ṛgveda, X. 92, where it is 12said that (nāsadāsīt na sadāsīt tadānīṃ), in the beginning there was neither the “Is” nor the “Is not,” which reminds one of the description of prakṛti (niḥsattāsattaṃ as that in which there is no existence or non-existence). In this way it may be shown from Gītā and other Sanskrit texts that an undifferentiated, unindividuated cosmic matter as the first principle, was often thought of and discussed from the earliest times. Later on this idea was utilised with modifications by the different schools of Vedāntists, the Sāṃkhyists and those who sought to make a reconciliation between them under the different names of prakṛti, avidyā and māyā. What avidyā really means according to the Pātañjala system we shall see later on; but here we see that whatever it might mean it does not mean prakṛti according to the Pātañjala system. Vyāsa-bhāshya, IV. 13, makes mention of māyā also in a couplet from Shashṭitantraśāstra;

The real appearance of the guṇas does not come within the line of our vision. That, however, which comes within the line of vision is but paltry delusion and Vācaspati Miśra explains it as follows:—Prakṛti is like the māyā but it is not māyā. It is trifling (sutucchaka) in the sense that it is changing. Just as māyā constantly changes, so the transformations of prakṛti are every moment appearing and vanishing and thus suffering momentary changes. Prakṛti being eternal is real and thus different from māyā.

This explanation of Vācaspati’s makes it clear that the word māyā is used here only in the sense of illusion, and without reference to the celebrated māyā of the Vedāntists; and Vācaspati clearly says that prakṛti can in no sense be called māyā, since it is real.[13]

We shall get a more definite notion of prakṛti as we advance further into the details of the later transformations of the prakṛti in connection with the purushas. The most difficult point is to understand the nature of its connection with the purushas. Prakṛti is a material, non-intelligent, independent principle, and the souls or spirits are isolated, neutral, intelligent and inactive. Then how can the one come into connection with the other?

In most systems of philosophy the same trouble has arisen and has caused the same difficulty in comprehending it rightly. Plato fights the difficulty of solving the unification of the idea and the non-being and offers his participation theory; even in Aristotle’s attempt to avoid the difficulty by his theory of form and matter, we are not fully satisfied, though he has shown much ingenuity and subtlety of thought in devising the “expedient in the single conception of development.”

The universe is but a gradation between the two extremes of potentiality and actuality, matter and form. But all students of Aristotle know that it is very difficult to understand the true relation between form and matter, and the particular nature of their interaction with each other, and this has created a great divergence of opinion among his commentators. It was probably to avoid this difficulty that the dualistic appearance of the philosophy of Descartes had to be reconstructed in the pantheism of Spinoza. Again we 14find also how Kant failed to bring about the relation between noumenon and phenomenon, and created two worlds absolutely unrelated to each other. He tried to reconcile the schism that he effected in his Critique of Pure Reason by his Critique of Practical Reason, and again supplemented it with his Critique of Judgment, but met only with dubious success.

In India also this question has always been a little puzzling, and before trying to explain the Yoga point of view, I shall first give some of the other expedients devised for the purpose, by the different schools of Advaita (monistic) Vedāntism.

I. The reflection theory of the Vedānta holds that the māyā is without beginning, unspeakable, mother of gross matter, which comes in connection with intelligence, so that by its reflection in the former we have Īśvara. The illustrations that are given to explain it both in Siddhāntaleśa[14] and in Advaita-Brahmasiddhi are only cases of physical reflection, viz. the reflection of the sun in water, or of the sky in water.

II. The limitation theory of the Vedānta holds that the all-pervading intelligence must necessarily be limited by mind, etc., so of necessity it follows that “the soul” is its limitation. This theory is illustrated by giving those common examples in which the Ākāśa (space) though unbounded in itself is often spoken of as belonging to a jug or limited by the jug and as such appears to fit itself to the shape and form of the jug and is thus called ghaṭāvacchinna ākāśa, i.e. space as within the jug.

Then we have a third school of Vedāntists, which seeks to explain it in another way:—The soul is neither a reflection nor a limitation, but just as the son of Kuntī was known as the son of Rādhā, so the pure Brahman by his nescience is known as the jīva, and like the prince who was brought up in the family of a low caste, it is the pure Brahman who by his own 15nescience undergoes birth and death, and by his own nescience is again released.[15]

The Sāṃkhya-sūtra also avails itself of the same story in IV. 1, “rājaputtravattattvopadeśāt,” which Vijñāna Bhikshu explains as follows:—A certain king’s son in consequence of his being born under the star Gaṇḍa having been expelled from his city and reared by a certain forester remains under the idea: “I am a forester.” Having learnt that he is alive, a certain minister informs him. “Thou art not a forester, thou art a king’s son.” As he, immediately having abandoned the idea of being an outcast, betakes himself to his true royal state, saying, “I am a king,” so too the soul realises its purity in consequence of instruction by some good tutor, to the effect—“Thou, who didst originate from the first soul, which manifests itself merely as pure thought, art a portion thereof.”

In another place there are two sūtras:—(1) niḥsaṅge’pi uparāgo vivekāt. (2) japāsphaṭikayoriva noparāgaḥ kintvabhimānaḥ. (1) Though it be associated still there is a tingeing through non-discrimination. (2) As in the case of the hibiscus and the crystal, there is not a tinge, but a fancy. Now it will be seen that all these theories only show that the transcendent nature of the union of the principle of pure intelligence is very difficult to comprehend. Neither the reflection nor the limitation theory can clear the situation from vagueness and incomprehensibility, which is rather increased by their physical illustrations, for the cit or pure intelligence cannot undergo reflection like a physical thing, nor can it be obstructed or limited by it. The reflection theory adduced by the Sāṃkhya-sūtra, “japāsphiṭikayoriva noparāgaḥ kintvabhimānaḥ,” 16is not an adequate explanation. For here the reflection produces only a seeming redness of the colourless crystal, which was not what was meant by the Vedāntists of the reflection school. But here, though the metaphor is more suitable to express the relation of purusha with the prakṛti, the exact nature of the relation is more lost sight of than comprehended. Let us now see how Patañjali and Vyāsa seek to explain it.

Let me quote a few sūtras of Patañjali and some of the most important extracts from the Bhāshya and try, as far as possible, to get the correct view:—

(1) The Ego-sense is the illusory appearance of the identity of the power as perceiver and the power as perceived.

(2) The seer though pure as mere “seeing” yet perceives the forms assumed by the psychosis (buddhi).

(3) It is for the sake of the purusha that the being of the knowable exists.

(4) For the emancipated person the world-phenomena cease to exist, yet they are not annihilated since they form a common field of experience for other individuals.

17(5) The cause of the realisation of the natures of the knowable and purusha in consciousness is their mutual contact.

(6) Cessation is the want of mutual contact arising from the destruction of ignorance and this is called the state of oneness.

(7) This state of oneness arises out of the equality in purity of the purusha and buddhi or sattva.

(8) Personal consciousness arises when the purusha, though in its nature unchangeable, is cast into the mould of the psychosis.

(9) Since the mind-objects exist only for the purusha, experience consists in the non-differentiation of these two which in their natures are absolutely distinct; the knowledge of self arises out of concentration on its nature.

Thus in Yoga-sūtra, II. 6, dṛik or purusha the seer is spoken of as śakti or power as much as the prakṛti itself, and we see that their identity is only apparent. Vyāsa in his Bhāshya explains ekātmatā (unity of nature or identity) as avibhāgaprāptāviva, “as if there is no difference.” And Pañcaśikha, as quoted in Vyāsa-bhāshya, writes: “not knowing the purusha beyond the mind to be different therefrom, in nature, character and knowledge, etc., a man has the notion of self, in the mind through delusion.”

Thus we see that when the mind and purusha are known to be separated, the real nature of purusha is realised. This seeming identity is again described as that which perceives the particular form of the mind and thereby appears, as identical with it though it is not so (pratyayānupaśya—pratyayāni bauddhamanupaśyati tamanupaśyannatadātmāpi tadātmaka iva pratibhāti, Vāysa-bhāshya, II. 20).

The purusha thus we see, cognises the phenomena of consciousness after they have been formed, and though its nature is different from conscious states yet it appears to be the same. Vyāsa in explaining this sūtra says that purusha is neither quite similar to the mind nor altogether different from it. 18For the mind (buddhi) is always changeful, according to the change of the objects that are offered to it; so that it may be said to be changeful according as it knows or does not know objects; but the purusha is not such, for it always appears as the self, being reflected through the mind by which it is thus connected with the phenomenal form of knowledge. The notion of self that appears connected with all our mental phenomena and which always illumines them is only duo to this reflection of purusha in the mind. All phenomenal knowledge which has the form of the object can only be transformed into conscious knowledge as “I know this,” when it becomes connected with the self or purusha. So the purusha may in a way be said to see again what was perceived by the mind and thus to impart consciousness by transferring its illumination into the mind. The mind suffers changes according to the form of the object of cognition, and thus results a state of conscious cognition in the shape of “I know it,” when the mind, having assumed the shape of an object, becomes connected with the constant factor purusha, through the transcendent reflection or identification of purusha in the mind. This is what is meant by pratyayānupaśya reperception of the mind-transformations by purusha, whereby the mind which has assumed the shape of any object of consciousness becomes intelligent. Even when the mind is without any objective form, it is always being seen by purusha. The exact nature of this reflection is indeed very hard to comprehend; no physical illustrations can really serve to make it clear. And we see that neither the Vyāsa-bhāshya nor the sūtras offer any such illustrations as Sāṃkhya did. But the Bhāshya proceeds to show the points in which the mind may be said to differ from purusha, as well as those in which it agrees with it. So that though we cannot express it anyhow, we may at least make some advance towards conceiving the situation.

19Thus the Bhāshya says that the main difference between the mind and purusha is that the mind is constantly undergoing modifications, as it grasps its objects one by one; for the grasping of an object, the act of having a percept is nothing but its own undergoing of different modifications, and thus, since an object sometimes comes within the grasp of the mind and again disappears in the subconscious as a saṃskāra (potency) and again comes into the field of the understanding as smṛti (memory), we see that it is pariṇāmi or changing. But purusha is the constant seer of the mind when it has an object, as in ordinary forms of phenomenal knowledge, or when it has no object as in the state of nirodha or cessation. Purusha is unchanging. It is the light which remains unchanged amidst all the changing modifications of the mind, so that we cannot distinguish purusha separately from the mind. This is what is meant by saying buddheḥ pratisaṃvedī purushaḥ, i.e. purusha reflects or turns into its own light the concepts of mind and thus is said to know it. Its knowing is manifested in our consciousness as the ever-persistent notion of the self, which is always a constant factor in all the phenomena of consciousness. Thus purusha always appears in our consciousness as the knowing agent. Truly speaking, however, purusha only sees himself; he is not in any way in touch with the mind. He is absolutely free from all bondage, absolutely unconnected with prakṛti. From the side of appearance he seems only to be the intelligent seer imparting consciousness to our conscious-like conception, though in reality he remains the seer of himself all the while. The difference between purusha and prakṛti will be clear when we see that purusha is altogether independent, existing in and for himself, free from any bondage whatsoever; but buddhi exists on the other hand for the enjoyment and release of purusha. That which exists in and for itself, must ever be the selfsame, unchangeable entity, suffering 20no transformations or modifications, for it has no other end owing to which it will be liable to change. It is the self-centred, self-satisfied light, which never seeks any other end and never leaves itself. But prakṛti is not such; it is always undergoing endless, complex modifications and as such does not exist for itself but for purusha, and is dependent upon him. The mind is unconscious, while purusha is the pure light of intelligence, for the three guṇas are all non-intelligent, and the mind is nothing but a modification of these three guṇas which are all non-intelligent.

But looked at from another point of view, prakṛti is not altogether different from purusha; for had it been so how could purusha, which is absolutely pure, reperceive the mind-modifications? Thus the Bhāshya (II. 20) writes:—

“Well then let him be dissimilar. To meet this he says: He is not quite dissimilar. Why? Although pure, he sees the ideas after they have come into the mind. Inasmuch as purusha cognises the ideas in the form of mind-modification, he appears to be, by the act of cognition, the very self of the mind although in reality he is not.” As has been said, the power of the enjoyer, purusha (dṛkśakti), is certainly unchangeable and it does not run after every object. In connection with a changeful object it appears forever as if it were being transferred to every object and as if it were assimilating its modifications. And when the modifications of the mind assume the form of the consciousness by which it is coloured, they imitate it and look as if they were manifestations of purusha’s consciousness unqualified by the modifications of the non-intelligent mind.

All our states of consciousness are analysed into two parts—a permanent and a changing part. The changing part is the form of our consciousness, which is constantly varying according to the constant change of its contents. The permanent part is that pure light of intelligence, by virtue of which 21we have the notion of self reflected in our consciousness. Now, as this self persists through all the varying changes of the objects of consciousness, it is inferred that the light which thus shines in our consciousness is unchangeable. Our mind is constantly suffering a thousand modifications, but the notion of self is the only thing permanent amidst all this change. It is this self that imports consciousness to the material parts of our knowledge. All our concepts originated from our perception of external material objects. Therefore the forms of our concepts which could exactly and clearly represent these material objects in their own terms, must be made of a stuff which in essence is not different from them. But with the reflection of purusha, the soul, the notion of self comes within the content of our consciousness, spiritualising, as it were, all our concepts and making them conscious and intelligent. Thus this seeming identity of purusha and the mind, by which purusha may be spoken of as the seer of the concept, appears to the self, which is manifested in consciousness by virtue of the seeming reflection. For this is that self, or personality, which remains unchanged all through our consciousness. Thus our phenomenal intelligent self is partially a material reality arising out of the seeming interaction of the spirit and the mind. This interaction is the only way by which matter releases spirit from its seeming bondage.

But the question arises, how is it that there can even be a seeming reflection of purusha in the mind which is altogether non-intelligent? How is it possible for the mind to catch a glimpse of purusha, which illuminates all the concepts of consciousness, the expression “anupaśya” meaning that he perceives by imitation (anukāreṇa paśyati)? How can purusha, which is altogether formless, allow any reflection of itself to imitate the form of buddhi, by virtue of which it appears as the self—the supreme possessor and knower of 22all our mental conceptions? There must be at least some resemblance between the mind and the purusha, to justify in some sense this seeming reflection. And we find that the last sūtra of the Vibhūtipāda says: sattvapurushayoḥ śuddhisāmye kaivalyaṃ—which means that when the sattva or the preponderating mind-stuff becomes as pure as purusha, kaivalya or oneness is attained. This shows that the pure nature of sattva has a great resemblance to the pure nature of purusha. So much so, that the last stage preceding the state of kaivalya, is almost the same as kaivalya itself, when purusha is in himself and there are no thoughts to reflect. In this state, we see that the mind can be so pure as to reflect exactly the nature of purusha, as he is in himself. This state in which the mind becomes as pure as purusha and reflects him in his purity, does not materially differ from the state of kaivalya, in which purusha is in himself—the only difference being that the mind, when it becomes so pure as this, becomes gradually lost in prakṛti and cannot again serve to bind purusha.

I cannot refrain here from the temptation of referring to a beautiful illustration from Vyāsa, to explain the way in which the mind serves the purposes of purusha. Cittamayaskāntamaṇikalpaṃ sannidhimātropakāri dṛśyatvena svaṃ bhavati purushasya svāminaḥ (I. 4), which is explained in Yoga-vārttika as follows: Tathāyaskāntamaṇiḥ svasminneva ayaḥsannidhīkaraṇamātrāt śalyarishkarshaṇākhyam upakāram kurvat purushasya svāminaḥ svam bhvati bhogasādhanatvāt, i.e. just as a magnet draws iron towards it, though it remains unmoved itself, so the mind-modifications become drawn towards purusha, and thereby become visible to purusha and serve his purpose.

To summarise: We have seen that something like a union takes place between the mind and purusha, i.e. there is a seeming reflection of purusha in the mind, simultaneously with its being determined conceptually, as a result whereof 23this reflection of purusha in the mind, which is known as the self, becomes united with these conceptual determinations of the mind and the former is said to be the perceiver of all these determinations. Our conscious personality or self is thus the seeming unity of the knowable as the mind in the shape of conceptual or judgmental representations with the reflections of purusha in the mind. Thus, in the single act of cognition, we have the notion of our own personality and the particular conceptual or perceptual representation with which this ego identifies itself. The true seer, the pure intelligence, the free, the eternal, remains all the while beyond any touch of impurity from the mind, though it must be remembered that it is its own seeming reflection in the mind that appears as the ego, the cogniser of all our states, pleasures and sorrows of the mind and one who is the apperceiver of this unity of the seeming reflection—of purusha and the determinations of the mind. In all our conscious states, there is such a synthetic unity between the determinations of our mind and the self, that they cannot be distinguished one from the other—a fact which is exemplified in all our cognitions, which are the union of the knower and the known. The nature of this reflection is a transcendent one and can never be explained by any physical illustration. Purusha is altogether different from the mind, inasmuch as he is the pure intelligence and is absolutely free, while the latter is non-intelligent and dependent on purusha’s enjoyment and release, which are the sole causes of its movement. But there is some similarity between the two, for how could the mind otherwise catch a seeming glimpse of him? It is also said that the pure mind can adapt itself to the pure form of purusha; this is followed by the state of kaivalya.

We have discussed the nature of purusha and its general relations with the mind. We must now give a few more illustrations. The chief point in which purusha of the Sāṃkhya-Pātañjala 24differs from the similar spiritual principle of Vedānta is, that it regards its soul, not as one, but as many. Let us try to discuss this point, in connection with the arguments of the Sāṃkhya-Pātañjala doctrine in favour of a separate principle of purusha. Thus the Kārikā says: saṃghātaparārthatvāt triguṇādiviparyyayādadhishthānāt purusho’sti bhoktṛbhāvāt kaivalyārthaṃ pravṛtteśca,[16] “Because an assemblage of things is for the sake of another; because there must be an entity different from the three guṇas and the rest (their modifications); because there must be a superintending power; because there must be someone who enjoys; and because of (the existence of) active exertion for the sake of abstraction or isolation (from the contact with prakṛti) therefore the soul exists.” The first argument is from design or teleology by which it is inferred that there must be some other simple entity for which these complex collocations of things are intended. Thus Gauḍapāda says: “In such manner as a bed, which is an assemblage of bedding, props, cotton, coverlet and pillows, is for another’s use, not for its own, and its several component parts render no mutual service, and it is concluded that there is a man who sleeps upon the bed and for whose sake it was made; so this world, which is an assemblage of the five elements, is for use and there is a soul, for whose enjoyment this body, another’s consisting of intellect and the rest, has been produced.”[17]

The second argument is that all the knowable is composed of just three elements: first, the element of sattva, or intelligence-stuff, causing all manifestations; second, the element of rajas or energy, which is ever causing transformations; and third, tamas, or the mass, which enables rajas to actualise. Now such a prakṛti, composed of these three elements, cannot itself be a seer. For the seer must be always 25the same unchangeable, actionless entity, the ever present, ever constant factor in all stages of our consciousness.

Third argument: There must be a supreme background of pure consciousness, all our co-ordinated basis of experience. This background is the pure actionless purusha, reflected in which all our mental states become conscious. Davies explains this a little differently, in accordance with a simile in the Tattva-Kaumudī, yathā rathādi yantrādibhiḥ, thus: “This idea of Kapila seems to be that the power of self-control cannot be predicted of matter, which must be directed or controlled for the accomplishment of any purpose, and this controlling power must be something external to matter and diverse from it. The soul, however, never acts. It only seems to act; and it is difficult to reconcile this part of the system with that which gives to the soul a controlling force. If the soul is a charioteer, it must be an active force.” But Davies here commits the mistake of carrying the simile too far. The comparison of the charioteer and the chariot holds good, to the extent that the chariot can take a particular course only when there is a particular purpose for the charioteer to perform. The motion of the chariot is fulfilled only when it is connected with the living person of the charioteer, whose purpose it must fulfil.

Fourth argument: Since prakṛti is non-intelligent, there must be one who enjoys its pains and pleasures. The emotional and conceptual determinations of such feelings are aroused in consciousness by the seeming reflection of the light of purusha.

Fifth argument: There is a tendency in all persons to move towards the oneness of purusha, to be achieved by liberation; there must be one for whose sake the modifications of buddhi are gradually withheld, and a reverse process set up, by which they return to their original cause prakṛti and thus liberate purusha. It is on account of this reverse tendency of prakṛti 26to release purusha that a man feels prompted to achieve his liberation as the highest consummation of his moral ideal.

Thus having proved the existence of purusha, the Kārikā proceeds to prove his plurality: “janmamaraṇakaraṇānāṃ pratiniyamādayugapat pravṛtteśca purushabahutvaṃ siddhaṃ traiguṇyaviparyyayācca.” “From the individual allotment of birth, death and the organs; from diversity of occupations and from the different conditions of the three guṇas, it is proved that there is a plurality of souls.” In other words, since with the birth of one individual, all are not born; since with the death of one, all do not die; and since each individual has separate sense organs for himself; and since all beings do not work at the same time in the same manner; and since the qualities of the different guṇas are possessed differently by different individuals, purushas are many. Patañjali, though he does not infer the plurality of purushas in this way, yet holds the view of the sūtra, kṛtārthaṃ prati nashṭamapyanashṭaṃ tadanyasādhāraṇatvāt. “Although destroyed in relation to him whose objects have been achieved, it is not destroyed, being common to others.”

Davies, in explaining the former Kārikā, says: “There is, however, the difficulty that the soul is not affected by the three guṇas. How can their various modifications prove the individuality of souls in opposition to the Vedāntist doctrine, that all souls are only portions of the one, an infinitely extended monad?”

This question is the most puzzling in the Sāṃkhya doctrine. But careful penetration of the principles of Sāṃkhya-Yoga would make clear to us that this is a necessary and consistent outcome of the Sāṃkhya view of a dualistic universe.

For if it is said that purusha is one and we have the notion of different selves by his reflection into different minds, it follows that such notions as self, or personality, are false. For the only true being is the one, purusha. So the knower 27being false, the known also becomes false; the knower and the known having vanished, everything is reduced to that which we can in no way conceive. It may be argued that according to the Sāṃkhya philosophy also, the knower is false, for the pure purusha as such is not in any way connected with prakṛti. But even then it must be observed that the Sāṃkhya-Yoga view does not hold that the knower is false but analyses the nature of the ego and says that it is due to the seeming unity of the mind and purusha, both of which are reals in the strictest sense of the term. Purusha is there justly called the knower. He sees and simultaneously with this, there is a modification of buddhi (mind); this seeing becomes joined with this modification of buddhi and thus arises the ego, who perceives that particular form of the modification of buddhi. Purusha always remains the knower. Buddhi suffers modifications and at the same time catches a glimpse of the light of purusha, so that contact (saṃyoga) of purusha and prakṛti occurs at one and the same point of time, in which there is unity of the reflection of purusha and the particular transformation of buddhi.

The knower, the ego and the knowable, are none of them false in the Sāṃkhya-Yoga system at the stage preceding kaivalya, when buddhi becomes as pure as purusha; its modification resembles the exact form of purusha and then purusha knows himself in his true nature in buddhi; after which buddhi vanishes. The Vedānta has to admit the modifications of māyā, but must at the same time hold it to be unreal. The Vedānta says that māyā is as beginningless as prakṛti yet has an ending with reference to the released person as the buddhi of the Sāṃkhyists.

But according to the Vedānta philosophy, knowledge of ego is only false knowledge—an illusion as many imposed upon the formless Brahman. Māyā, according to the Vedāntist, can neither be said to exist nor to non-exist. It 28is anirvācyā, i.e. can never be described or defined. Such an unknown and unknowable māyā causes the Many of the world by reflection upon the Brahman. But according to the Sāṃkhya doctrine, prakṛti is as real as purusha himself. Prakṛti and purusha are two irreducible metaphysical remainders whose connection is beginningless (anādisaṃyoga). But this connection is not unreal in the Vedānta sense of the term. We see that according to the Vedānta system, all notions of ego or personality are false and are originated by the illusive action of the māyā, so that when they ultimately vanish there are no other remainders. But this is not the case with Sāṃkhya, for as purusha is the real seer, his cognitions cannot be dismissed as unreal, and so purushas or knowers as they appear to us to be, must be held real. As prakṛti is not the māyā of the Vedāntist (the nature of whose influence over the spiritual principle cannot be determined) we cannot account for the plurality of purushas by supposing that one purusha is being reflected into many minds and generating the many egos. For in that case it will be difficult to explain the plurality of their appearances in the minds (buddhis). For if there be one spiritual principle, how should we account for the supposed plurality of the buddhis? For we should rather expect to find one buddhi and not many to serve the supposed one purusha, and this will only mean that there can be only one ego, his enjoyment and release. Supposing for argument’s sake that there are many buddhis and one purusha, which reflected in them, is the cause of the plurality of selves, then we cannot see how prakṛti is moving for the enjoyment and release of one purusha; it would rather appear to be moved for the sake of the enjoyment and release of the reflected or unreal self. For purusha is not finally released with the release of any number of particular individual selves. For it may be released with reference to one individual but remain bound to others. So prakṛti 29would not really be moved in this hypothetical case for the sake of purusha, but for the sake of the reflected selves only. If we wish to avoid the said difficulties, then with the release of one purusha, all purushas will have to be released. For in the supposed theory there would not really be many different purushas, but the one purusha appearing as many, so that with his release all the other so-called purushas must be released. We see that if it is the enjoyment (bhoga) and salvation (apavarga) of one purusha which appear as so many different series of enjoyments and emancipations, then with his experiences all should have the same experiences. With his birth and death, all should be born or all should die at once. For, indeed, it is the experiences of one purusha which appear in all the seeming different purushas. And in the other suppositions there is neither emancipation nor enjoyment by purusha at all. For there, it is only the illusory self that enjoys or releases himself. By his release no purusha is really released at all. So the fundamental conception of prakṛti as moving for the sake of the enjoyment and release of purusha has to be abandoned.

So we see that from the position in which Sāṃkhya and Yoga stood, this plurality of the purushas was the most consistent thing that they could think of. Any compromise with the Vedānta doctrine here would have greatly changed the philosophical aspect and value of the Sāṃkhya philosophy. As the purushas are nothing but pure intelligences they can as well be all-pervading though many. But there is another objection that, since number is a conception of the phenomenal mind, how then can it be applied to the purushas which are said to be many?[18] But that difficulty remains unaltered 30even if we regard the purusha as one. When we go into the domain of metaphysics and try to represent Reality with the symbols of our phenomenal conceptions we have really to commit almost a violence towards it. But we must perforce do this in all our attempts to express in our own terms that pure, inexpressible, free illumination which exists in and for itself beyond the range of any mediation by the concepts or images of our mind. So we see that Sāṃkhya was not inconsistent in holding the doctrine of the plurality of the purushas. Patañjali does not say anything about it, since he is more anxious to discuss other things connected with the presupposition of the plurality of purusha. Thus he speaks of it only in one place as quoted above and says that though for a released person this world disappears altogether, still it remains unchanged in respect to all the other purushas.

We may now come to the attempt of Yoga to prove the reality of an external world as against the idealistic Buddhists. In sūtra 12 of the chapter on kaivalya we find: “The past and the future exist in reality, since all qualities of things manifest themselves in these three different ways. The future is the manifestation which is to be. The past is the appearance which has been experienced. The present is that which is in active operation. It is this threefold substance which is the object of knowledge. If it did not exist in reality, there would not exist a knowledge thereof. How could there be knowledge in the absence of anything knowable? For this reason the past and present in reality exist.”[19]

So we see that the present holding within itself the past and the future exists in reality. For the past though it has been negated has really been preserved and kept in the present, and the future also though it has not made its appearance yet exists potentially in the present. So, as we know the past and the future worlds in the present, they both exist and subsist in the present. That which once existed cannot die, and that which never existed cannot come to be (nāstyasataḥ saṃbhavaḥ na cāsti sato vināsāḥ, Vyāsa-bhāshya, V. 12). So the past has not been destroyed but has rather shifted its 32position and hidden itself in the body of the present, and the future that has not made its appearance exists in the present only in a potential form. It cannot be argued, as Vācaspati says, that because the past and the future are not present therefore they do not exist, for if the past and future do not exist how can there be a present also, since its existence also is only relative? So all the three exist as truly as any one of them, and the only difference among them is the different way or mode of their existence.

He next proceeds to refute the arguments of those idealists who hold that since the external knowables never exist independently of our knowledge of them, their separate external existence as such may be denied. Since it is by knowledge alone that the external knowables can present themselves to us we may infer that there is really no knowable external reality apart from knowledge of it, just as we see that in dream-states knowledge can exist apart from the reality of any external world.

So it may be argued that there is, indeed, no external reality as it appears to us. The Buddhists, for example, hold that a blue thing and knowledge of it as blue are identical owing to the maxim that things which are invariably perceived together are one (sahopalambhaniyamādabhedo nīlataddhiyoḥ). So they say that external reality is not different from our idea of it. To this it may be replied that if, as you say, external reality is identical with my ideas and there is no other external reality existing as such outside my ideas, why then does it appear as existing apart, outside and independent of my ideas? The idealists have no basis for the denial of external reality, and for their assertion that it is only the creation of our imagination like experiences in dreams. Even our ideas carry with them the notion that reality exists outside our mental experiences. If all our percepts and notions as this and that arise only by virtue of the influence 33of the external world, how can they deny the existence of the external world as such? The objective world is present by its own power. How then can this objective world be given up on the strength of mere logical or speculative abstraction?

Thus the Vyāsa-bhāshya, IV. 14, says: “There is no object without the knowledge of it, but there is knowledge as imagined in dreams without any corresponding object; thus the reality of external things is like that of dream-objects, mere imagination of the subject and unreal. How can they who say so be believed? Since they first suppose that the things which present themselves to us by their own force do so only on account of the invalid and delusive imagination of the intellect, and then deny the reality of the external world on the strength of such an imaginary supposition of their own.”

The external world has generated knowledge of itself by its own presentative power (arthena svakīyayāgrāhyaśaktyā vijñānamajani), and has thus caused itself to be represented in our ideas, and we have no right to deny it.[20] Commenting on the Bhāshya IV. 14, Vācaspati says that the method of agreement applied by the Buddhists by their sahopalambhaniyama (maxim of simultaneous revelation) may possibly be confuted by an application of the method of difference. The method of agreement applied by the idealists when put in proper form reads thus: “Wherever there is knowledge there is external reality, or rather every case of knowledge agrees with or is the same as every case of the presence of external reality, so knowledge is the cause of the presence of the external reality, i.e. the external world depends for its reality on our knowledge or ideas and owes its origin or appearance as such to them.” But Vācaspati says that this application of the method of agreement is not certain, for it cannot be corroborated by the method of difference. For 34the statement that every case of absence of knowledge is also a case of absence of external reality cannot be proved, i.e. we cannot prove that the external reality does not exist when we have no knowledge of it (sahopalambhaniyamaśca vedyatvañca hetū sandigdhavyatirekatayānaikāntikau) IV. 14.

Describing the nature of grossness and externality, the attributes of the external world, he says that grossness means the pervading of more portions of space than one, i.e. grossness means extension, and externality means being related to separate space, i.e. co-existence in space. Thus we see that extension and co-existence in space are the two fundamental qualities of the gross external world. Now an idea can never be said to possess them, for it cannot be said that an idea has extended into more spaces than one and yet co-existed separately in separate places. An idea cannot be said to exist with other ideas in space and to extend in many points of space at one and the same time. To avoid this it cannot be said that there may be plurality of ideas so that some may co-exist and others may extend in space. For co-existence and extension can never be asserted of our ideas, since +hey are very fine and subtle, and can be known only at the time of their individual operation, at which time, however, other ideas may be quite latent and unknown. Imagination has no power to negate their reality, for the sphere of imagination is quite distinct from the sphere of external reality, and it can never be applied to an external reality to negate it. Imagination is a mental function, and as such has no touch with the reality outside, which it can by no means negate.

Further it cannot be said that, because grossness and externality can abide neither in the external world nor in our ideas, they are therefore false. For this falsity cannot be thought as separable from our ideas, for in that case our ideas would be as false as the false itself. The notion of externality and grossness pervades all our ideas, and if they are held to 35be false, no true thing can be known by our ideas and they therefore become equally false.

Again, knowledge and the external world can never be said to be identical because they happen to be presented together. For the method of agreement cannot by itself prove identity. Knowledge and the knowable external world may be independently co-existing things like the notions of existence and non-existence. Both co-exist independently of one another. It is therefore clear enough, says Vācaspati, that the certainty arrived at by perception, which gives us a direct knowledge of things, can never be rejected on the strength of mere logical abstraction or hair-splitting discussion.

We further see, says Patañjali, that the thing remains the same though the ideas and feelings of different men may change differently about it.[21] Thus A, B, C may perceive the same identical woman and may feel pleasure, pain or hatred. We see that the same common thing generates different feelings and ideas in different persons; external reality cannot be said to owe its origin to the idea or imagination of any one man, but exists independently of any person’s imagination in and for itself. For if it be due to the imagination of any particular man, it is his own idea which as such cannot generate the same ideas in another man. So it must be said that the external reality is what we perceive it outside.

There are, again, others who say that just as pleasure and pain arise along with our ideas and must be said to be due to them so the objective world also must be said to have come into existence along with our ideas. The objective world therefore according to these philosophers has no external existence either in the past or in the future, but has only a momentary existence in the present due to our ideas about it. That much existence only are they ready to attribute to external objects which can be measured by the idea of the 36moment. The moment I have an idea of a thing, the thing rises into existence and may be said to exist only for that moment and as soon as the idea disappears the object also vanishes, for when it cannot be presented to me in the form of ideas it can be said to exist in no sense. But this argument cannot hold good, for if the objective reality should really depend upon the idea of any individual man, then the objective reality corresponding to an idea of his ought to cease to exist either with the change of his idea, or when he directs attention to some other thing, or when he restrains his mind from all objects of thought. Now, then, if it thus ceases to exist, how can it again spring into existence when the attention of the individual is again directed towards it? Again, all parts of an object can never be seen all at once. Thus supposing that the front side of a thing is visible, then the back side which cannot be seen at the time must not be said to exist at all. So if the back side does not exist, the front side also can as well be said not to exist (ye cāsyānupasthitā bhāgaste cāsya na syurevaṃ nāsti pṛshṭhamiti udaramapi na gṛhyeta. Vyāsa-bhāshya, IV. 16). Therefore it must be said that there is an independent external reality which is the common field of observation for all souls in general; and there are also separate “Cittas” for separate individual souls (tasmāt svatantro’rthaḥ sarvapurusasādhdāraṇaḥ svatantrāṇi ca cittāni pratipurushaṃ, pravarttante, ibid.). And all the experiences of the purusha result from the connection of this “Citta” (mind) with the external world.

Now from this view of the reality of the external world we are confronted with another question—what is the ground which underlies the manifold appearance of this external world which has been proved to be real? What is that something which is thought as the vehicle of such qualities as produce in us the ideas? What is that self-subsistent substratum which is the basis of so many changes, actions and reactions 37that we always meet in the external world? Locke called this substratum substance and regarded it as unknown, but said that though it did not follow that it was a product of our own subjective thought yet it did not at the same time exist without us. Hume, however, tried to explain everything from the standpoint of association of ideas and denied all notions of substantiality. We know that Kant, who was much influenced by Hume, agreed to the existence of some such unknown reality which he called the Thing-in-itself, the nature of which, however, was absolutely unknowable, but whose influence was a great factor in all our experiences.

But the Bhāshya tries to penetrate deeper into the nature of this substratum or substance and says: dharmisvarūpamātro hi dharmaḥ, dharmivikriyā eva eshā dharmadvārā prapañcyate, Vyāsa-bhāshya, III. 13. The characteristic qualities form the very being itself of the characterised, and it is the change of the characterised alone that is detailed by means of the characteristic. To understand thoroughly the exact significance of this statement it will be necessary to take a more detailed review of what has already been said about the guṇas. We know that all things mental or physical are formed by the different collocations of sattva of the nature of illumination (prakāśa), rajas—the energy or mutative principle of the nature of action (kriyā)—and tamas—the obstructive principle of the nature of inertia (sthiti) which in their original and primordial state are too fine to be apprehended (gunānāṃparamaṃ rūpaṃ na dṛshṭipathamṛcchati, Vyāsa-bhāshya, IV. 13). These different guṇas combine in various proportions to form the manifold universe of the knowable, and thus are made the objects of our cognition. Through combining in different proportions they become, in the words of Dr. B. N. Seal, “more and more differentiated, determinate and coherent,” and thus make themselves cognisable, yet they never forsake their own true nature as the guṇas. So we see that they have thus got 38two natures, one in which they remain quite unchanged as guṇas, and another in which they collocate and combine themselves in various ways and thus appear under the veil of a multitude of qualities and states of the manifold knowable (te vyaktasūkshmā guṇātmānaḥ [IV. 13] ... sarvamidaṃ guṇānāṃ sanniveśaviśeshamātramiti paramārthato guṇātmānaḥ, Bhāshya, ibid.).

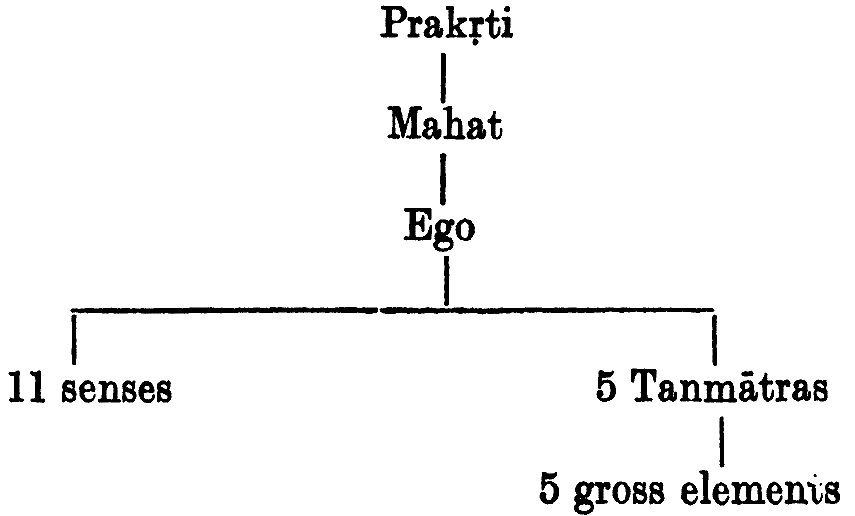

Now these guṇas take three different courses of development from the ego or ahaṃkāra according to which the ego or ahaṃkāra may be said to be sāttvika, rājasa and tāmasa. Thus from the sāttvika side of the ego by a preponderance of sattva the five knowledge-giving senses, e.g. hearing, sight, touch, taste and smell are derived. From the rajas side of ego by a preponderance of rajas the five active senses of speech, etc., are derived. From the tamas side of ego or ahaṃkāra by a preponderance of tamas are derived the five tanmātras. From which again by a preponderance of tamas the atoms of the five gross elements—earth, water, fire, air and ether are derived.

In the derivation of these it must be remembered that all the three guṇas are conjointly responsible. In the derivation of a particular product one of the guṇas may indeed be predominant, and thus may bestow the prominent characteristic of that product, but the other two guṇas are also present there and perform their functions equally well. Their opposition does not withhold the progress of evolution but rather helps it. All the three combine together in varying degrees of mutual preponderance and thus together help the process of evolution to produce a single product. Thus we see that though the guṇas are three, they combine to produce on the side of perception, the senses, such as those of hearing, sight, etc.; and on the side of the knowable, the individual tanmātras of gandha, rasa, rūpa, sparśa and śabda. The guṇas composing each tanmātra again harmoniously combine 39with each other with a preponderance of tamas to produce the atoms of each gross element. Thus in each combination one class of guṇas remains prominent, while the others remain dependent upon it but help it indirectly in the evolution of that particular product.

The evolution which we have spoken of above may be characterised in two ways: (1) That arising from modifications or products of some other cause which are themselves capable of originating other products like themselves; (2) That arising from causes which, though themselves derived, yet cannot themselves be the cause of the origination of other existences like themselves. The former may be said to be slightly specialised (aviśesha) and the latter thoroughly specialised (viśesha).

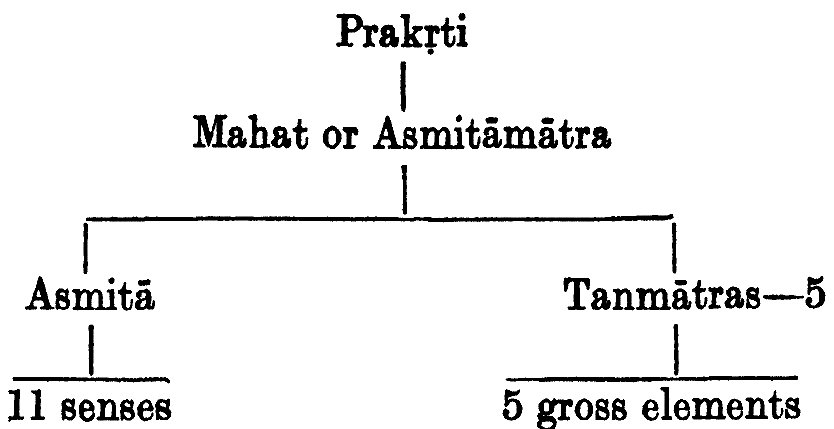

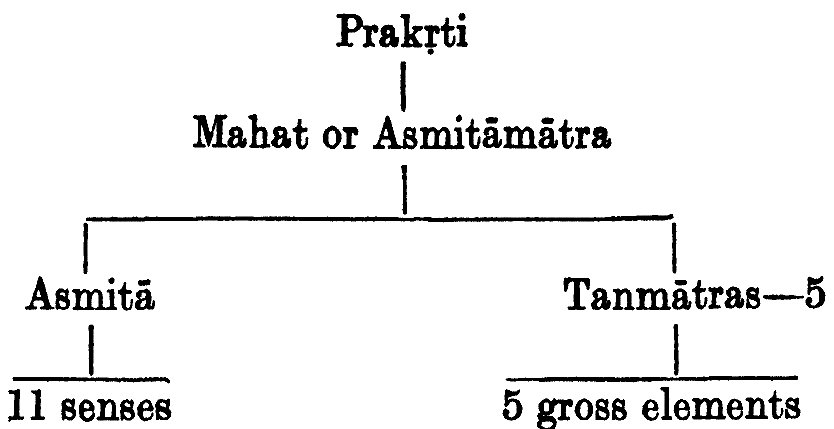

Thus we see that from prakṛti comes mahat, from mahat comes ahaṃkāra, and from ahaṃkāra, as we have seen above, the evolution takes three different courses according to the preponderance of sattva, rajas and tamas originating the cognitive and conative senses and manas, the superintendent of them both on one side and the tanmātras on the other. These tanmātras again produce the five gross elements. Now when ahaṃkāra produces the tanmātras or the senses, or when the tanmātras produce the five gross elements, or when ahaṃkāra itself is produced from buddhi or mahat, it is called tattvāntara-pariṇāma, i.e. the production of a different tattva or substance.

Thus in the case of tattvāntara-pariṇāma (as for example when the tanmātras are produced from ahaṃkāra), it must be carefully noticed that the state of being involved in the tanmātras is altogether different from the state of being of 41ahaṃkāra; it is not a mere change of quality but a change of existence or state of being.[22] Thus though the tanmātras are derived from ahaṃkāra the traces of ahaṃkāra cannot be easily followed in them. This derivation is not such that the ahaṃkāra remains principally unchanged and there is only a change of quality in it, but it is a different existence altogether, having properties which differ widely from those of ahaṃkāra. So it is called tattvāntara-pariṇāma, i.e. evolution of different categories of existence.